Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Data

2.2. Design and Sample Size

2.3. Study Variables and Measurement

2.3.1. Outcome Variable

2.3.2. Explanatory Variables or Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Ghanaian Women's Attitude Towards Intimate Partner Violence

3.2. Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence Justification Among Women in Ghana

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, R.; Garg, S. , Addressing domestic violence against women: an unfinished agenda. Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine 2008, 33, 73–6. [Google Scholar]

- Casique, L. C.; Furegato, A. R. , Violence against women: theoretical reflections. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem 2006, 14, 950–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Garg, S. , Addressing Domestic Violence Against Women: An Unfinished Agenda. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 2008, 33, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemhaka, G. B.; Moyo, S.; Simelane, M. S.; Odimegwu, C. , Women's socioeconomic status and attitudes toward intimate partner violence in Eswatini: A multilevel analysis. PloS one 2023, 18, e0294160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, E.; Tenkorang, E. Y. , Structural and Institutional Barriers to Help-Seeking among Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Ghana. Journal of Family Violence 2023, 38, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Poddar, P. , Women’s Empowerment and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence from a Multidimensional Policy in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change 2024, 72, 801–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemhaka, G. B.; Moyo, S.; Simelane, M. S.; Odimegwu, C. , Women’s socioeconomic status and attitudes toward intimate partner violence in Eswatini: A multilevel analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0294160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, L. L. , Violence Against Women:An Integrated, Ecological Framework. Violence Against Women 1998, 4, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R. K.; Rahman, N.; Kabir, E.; Raihan, F. , Women’s opinion on the justification of physical spousal violence: A quantitative approach to model the most vulnerable households in Bangladesh. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. I.; Sultana, N. , Attitudes of Women Toward Domestic Violence: What Matters the Most? Violence and Gender 2022, 9, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, B.; Olorunsaiye, C. Z.; Ahinkorah, B. O.; Ameyaw, E. K.; Budu, E.; Seidu, A.-A.; Yaya, S. , Understanding the factors associated with married women’s attitudes towards wife-beating in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Women's Health 2022, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Malik, M. I. , The Role of Social Norm in Acceptability Attitude of Women Toward Intimate Partner Violence in Punjab, Pakistan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2021, 36, (21–22). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doku, D. T.; Asante, K. O. , Women's approval of domestic physical violence against wives: analysis of the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Womens Health 2015, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaba, E. A.; Manu, A.; Ogum-Alangea, D.; Modey, E. J.; Addo-Lartey, A.; Torpey, K. , Young people's attitudes towards wife-beating: Analysis of the Ghana demographic and health survey 2014. PloS one 2021, 16, e0245881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Salman, V. , Women’s Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence in Sindh, Pakistan: An Analysis of Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey. Journal of Family Issues 2023, 0192513X231201977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, M.; Pinsky, I.; Laranjeira, R.; Ramisetty-Mikler, S.; Caetano, R. , Intimate partner violence and contribution of drinking and sociodemographics: the Brazilian National Alcohol Survey. Journal of interpersonal violence 2010, 25, 648–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, C. , Socio-economic inequalities in intimate partner violence justification among women in Ghana: analysis of the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey data. International Health 2023, 15, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu, C.; Asare, B. Y.-A.; Agyemang-Duah, W.; Adomako, E. B.; Agyekum, A. K.; Peprah, P. , Impact of socio-demographic and economic factors on intimate partner violence justification among women in union in Papua New Guinea. Archives of Public Health 2022, 80, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paintsil, J. A.; Adde, K. S.; Ameyaw, E. K.; Dickson, K. S.; Yaya, S. , Gender differences in the acceptance of wife-beating: evidence from 30 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Women's Health 2023, 23, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS2017/18), Survey Findings Report; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2018.

- Doku, D. T.; Asante, K. O. , Women’s approval of domestic physical violence against wives: analysis of the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Women's Health 2015, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, R. G.; Seidu, A.-A.; Asare, B. Y.-A.; Peprah, P.; Addo, I. Y.; Ahinkorah, B. O. , Exposure to interparental violence and justification of intimate partner violence among women in sexual unions in sub-Saharan Africa. Archives of Public Health 2021, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, K. S.; Ameyaw, E. K.; Darteh, E. K. M. , Understanding the endorsement of wife beating in Ghana: evidence of the 2014 Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Women's Health 2020, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odero, M.; Hatcher, A. M.; Bryant, C.; Onono, M.; Romito, P.; Bukusi, E. A.; Turan, J. M. , Responses to and resources for intimate partner violence: qualitative findings from women, men, and service providers in rural Kenya. J Interpers Violence 2014, 29, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogland, E. G.; Xu, X.; Bartkowski, J. P.; Ogland, C. P. , Intimate Partner Violence Against Married Women in Uganda. Journal of Family Violence 2014, 29, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H. A. R. , Role of Education in the Empowerment of Women in India. Edunity Kajian Ilmu Sosial dan Pendidikan 2023, 2, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable (Categories) | Non justification of IPV (%) | IPV Justification (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Area (p-value of Chi square <0.001) | ||

| Urban | 5383 (74.5%) | 1843 (25.5%) |

| Rural | 4195 (59.8%) | 2816 (40.2%) |

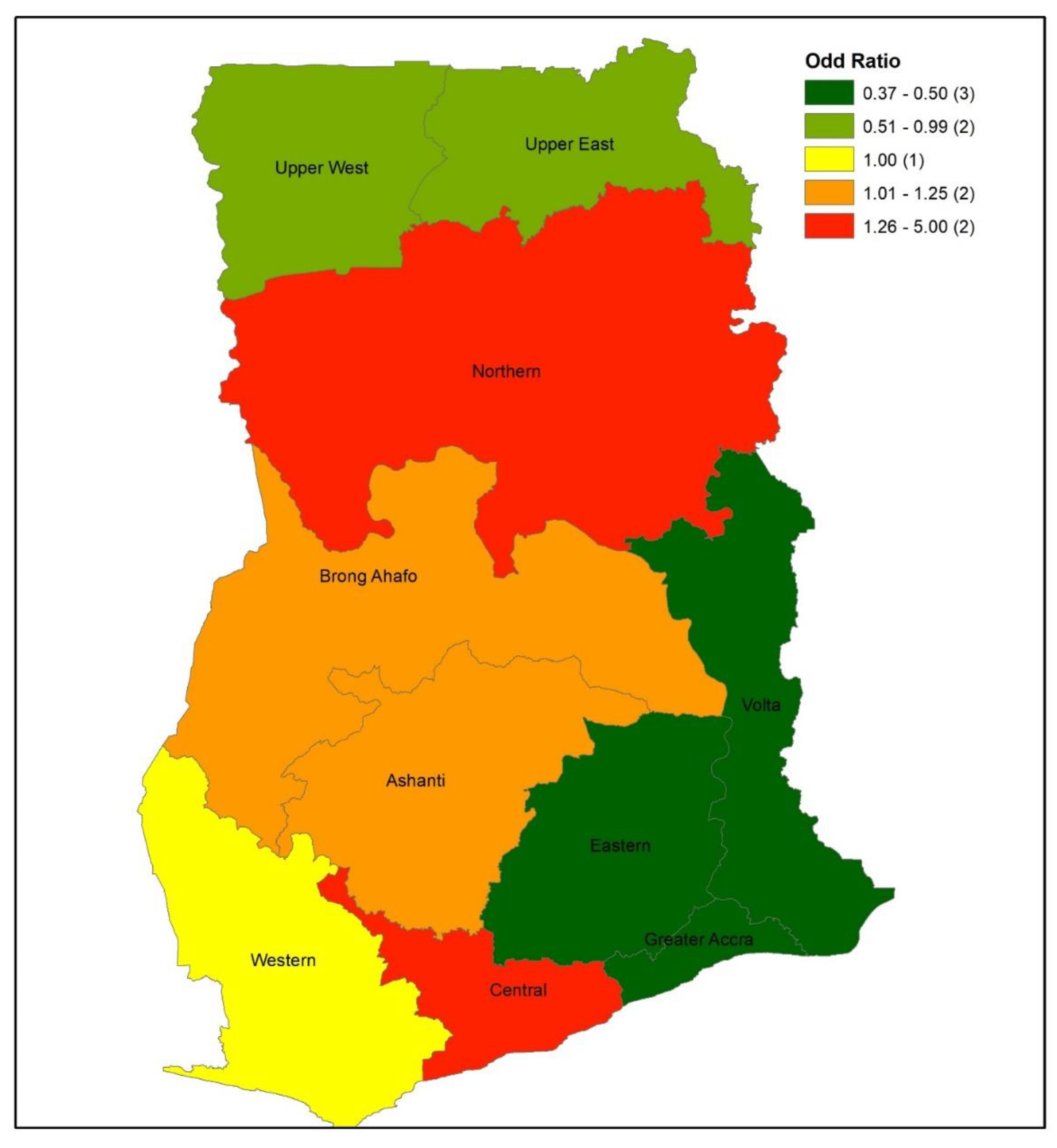

| Region (p<0.001) | ||

| Western | 940 (66.8%) | 468 (33.2%) |

| Central | 839 (60.5%) | 547 (39.5%) |

| Greater Accra | 1635 (87.1%) | 242 (12.9%) |

| Volta | 878 (79.7%) | 223 (20.3%) |

| Eastern | 1392 (81.2%) | 322 (18.8%) |

| Ashanti | 2215 (65.1%) | 1185 (34.9%) |

| Brong Ahafo | 824 (62.9%) | 487 (37.1%) |

| Northern | 429 (33.1%) | 866 (66.9%) |

| Upper East | 250 (59.4%) | 171 (40.6%) |

| Upper West | 177 (54.5%) | 148 (45.5%) |

| Age (p< 0.001) | ||

| 15-19 | 1772 (62%) | 1085 (38%) |

| 20-24 | 1491 (68.7%) | 679 (31.3%) |

| 25-29 | 1505 (70.3%) | 637 (29.7%) |

| 30-34 | 1462 (68.5%) | 671 (31.5%) |

| 35-39 | 1322 (68.5%) | 607 (31.5%) |

| 40-44 | 1120 (66.2%) | 571 (33.8%) |

| 45-49 | 906 (68.9%) | 408 (31.1%) |

| Woman' Education (p< 0.001) | ||

| Pre-primary or none | 1362 (50.8%) | 1318 (49.2%) |

| Primary | 1555 (63%) | 913 (37%) |

| JSS/JHS/Middle | 3877 (68%) | 1826 (32%) |

| SSS/SHS/ Secondary | 2023 (79.2%) | 531 (20.8%) |

| Higher | 760 (91.5%) | 71 (8.5%) |

| DK/Missing | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Marital status/Union (p< 0.001) | ||

| Currently married/in union | 5340 (65.5%) | 2817 (34.5%) |

| Formerly married/in union | 913 (66.9%) | 452 (33.1%) |

| Never married/in union | 3325 (70.5%) | 1391 (29.5%) |

| Functional difficulties (age 18-49 years) | ||

| Has functional difficulty | 774 (66.8%) | 385 (33.2%) |

| Has no functional difficulty | 7682 (68.3%) | 3570 (31.7%) |

| Wealth index quintile (p˂ 0.001) | ||

| Poorest | 1251 (52.6%) | 1128 (47.4%) |

| Second | 1515 (57.7%) | 1112 (42.3%) |

| Middle | 1902 (65.9%) | 986 (34.1%) |

| Fourth | 2109 (70%) | 904 (30%) |

| Richest | 2802 (84.1%) | 528 (15.9%) |

| Ethnicity of household (p˂ 0.001) | ||

| Akan | 4822 (71%) | 1972 (29%) |

| Ga/Dangme | 1036 (81.1%) | 241 (18.9%) |

| Ewe | 1252 (79.7%) | 319 (20.3%) |

| Guan | 359 (65.5%) | 189 (34.5%) |

| Gruma | 240 (45.5%) | 287 (54.5%) |

| Mole Dagbani | 943 (46.7%) | 1076 (53.3%) |

| Grusi | 177 (55.8%) | 140 (44.2%) |

| Mande | 71 (73.2%) | 26 (26.8%) |

| Other | 677 (62.5%) | 406 (37.5%) |

| Missing | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| Frequency of reading newspaper/magazine (p˂ 0.001) | ||

| Not at all | 8231 (65.3%) | 4381 (34.7%) |

| Less than once a week | 671 (79.9%) | 169 (20.1%) |

| At Least once a week | 511 (84.7%) | 92 (15.3%) |

| Almost every week | 166 (90.7%) | 17 (9.3%) |

| Frequency of listening to radio (p˂ 0.001) | ||

| Not at all | 2733 (60.6%) | 1775 (39.4%) |

| Less than once a week | 1629 (67.3%) | 792 (32.7%) |

| At least once a week | 2104 (70.7%) | 872 (29.3%) |

| Almost every week | 3113 (71.8%) | 1221 (28.2%) |

| Frequency of watching TV (p˂ 0.001) | ||

| Not at all | 2116 (56.7%) | 1619 (43.3%) |

| Less than once a week | 1077 (64%) | 606 (36%) |

| At Least once a week | 1652 (69.3%) | 733 (30.7%) |

| Almost every week | 4733 (73.6%) | 1701 (26.4%) |

| Variables (with reference) | Odd ratio (OR) | 95% C.I. for OR | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Area (ref: Urban) | ||||

| Rural | 1.238 | 1.122 | 1.367 | <.001 |

| Region (Ref: Western region) | ||||

| Central | 1.312 | 1.101 | 1.564 | 0.002 |

| Greater Accra | 0.443 | 0.359 | 0.547 | <.001 |

| Volta | 0.373 | 0.291 | 0.477 | <.001 |

| Eastern | 0.494 | 0.41 | 0.596 | <.001 |

| Ashanti | 1.155 | 0.993 | 1.343 | 0.061 |

| Brong Ahafo | 1.062 | 0.886 | 1.274 | 0.514 |

| Northern | 2.411 | 1.955 | 2.973 | <.001 |

| Upper East | 0.751 | 0.567 | 0.994 | 0.045 |

| Upper West | 0.941 | 0.698 | 1.27 | 0.692 |

| Age group (Ref: 15-19 years old) | ||||

| 20-24 | 0.709 | 0.596 | 0.842 | <.001 |

| 25-29 | 0.544 | 0.45 | 0.658 | <.001 |

| 30-34 | 0.542 | 0.445 | 0.659 | <.001 |

| 35-39 | 0.481 | 0.394 | 0.587 | <.001 |

| 40-44 | 0.542 | 0.442 | 0.665 | <.001 |

| 45-49 | 0.467 | 0.376 | 0.581 | <.001 |

| Woman's Education (Ref: Pre-primary or none) | ||||

| Primary | 0.849 | 0.744 | 0.969 | 0.015 |

| JSS/JHS/Middle | 0.756 | 0.665 | 0.859 | <.001 |

| SSS/SHS/ Secondary | 0.512 | 0.432 | 0.606 | <.001 |

| Higher | 0.248 | 0.185 | 0.332 | <.001 |

| DK/Missing | 0 | 0 | 0.999 | |

| Marital/Union status of woman (Ref: Currently married/Union) | ||||

| Formerly married/in union | 1.065 | 0.932 | 1.216 | 0.357 |

| Never married/in union | 0.726 | 0.634 | 0.831 | <.001 |

| Functional difficulties (age 18-49 years) (Ref: Has functional difficulty) | ||||

| Has no functional difficulty | 0.997 | 0.866 | 1.148 | 0.966 |

| Wealth index quintile (Ref: Poorest) | ||||

| Second | 1.199 | 1.043 | 1.379 | 0.011 |

| Middle | 1.168 | 1.004 | 1.359 | 0.044 |

| Fourth | 1.106 | 0.935 | 1.307 | 0.24 |

| Richest | 0.766 | 0.634 | 0.926 | 0.006 |

| Ethnicity of household head (Ref: Akan) | ||||

| GA/Damgme | 0.86 | 0.714 | 1.036 | 0.112 |

| Ewe | 1.06 | 0.884 | 1.271 | 0.529 |

| Guan | 1.332 | 1.052 | 1.685 | 0.017 |

| Gruma | 1.434 | 1.128 | 1.823 | 0.003 |

| Mole Dagbani | 1.61 | 1.378 | 1.88 | <.001 |

| Grusi | 1.598 | 1.217 | 2.097 | <.001 |

| Mande | 0.749 | 0.435 | 1.291 | 0.299 |

| Other | 1.393 | 1.182 | 1.641 | <.001 |

| Missing | 2.495 | 0.329 | 18.94 | 0.377 |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine (Ref: not at all) | ||||

| Less than once a week | 1.017 | 0.816 | 1.268 | 0.878 |

| At least once a week | 0.646 | 0.483 | 0.866 | 0.003 |

| Almost every day | 0.795 | 0.455 | 1.389 | 0.421 |

| Frequency of listening to the radio (Ref: Not at all) | ||||

| Less than once a week | 0.862 | 0.76 | 0.977 | 0.02 |

| At least once a week | 0.908 | 0.804 | 1.025 | 0.119 |

| Almost every day | 0.92 | 0.825 | 1.025 | 0.131 |

| Frequency of watching TV (Ref: Not at all) | ||||

| Less than once a week | 0.824 | 0.712 | 0.954 | 0.01 |

| At least once a week | 0.817 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.005 |

| Almost every day | 0.78 | 0.692 | 0.88 | <.001 |

| Constant | 1.222 | 0.194 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).