Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

SNP-Trait Associations Through Data Mining of GWAS

Primary and Deep In Silico Databases

Clustering Enriched Ontology (CEO) and Meta-Analyses

Statistical Evaluations

Results

GWAS-Based Deep In Silico PGx Investigations

Signaling

GMIs

PDIs

PCIs

Enrichr Analysis (EA) Results

Metabolomics Predictions

| Index | Name | P-value | Adjusted p-value | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dopamine | 0.00003250 | 0.0003250 | 356.54 |

| 2 | Pyruvaldehyde | 0.008967 | 0.01492 | 137.69 |

| 3 | N4-Acetylaminobutanal | 0.008967 | 0.01492 | 137.69 |

| 4 | 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylglycol | 0.008967 | 0.01492 | 137.69 |

| 5 | Indoleacetaldehyde | 0.01045 | 0.01492 | 114.74 |

| 6 | Serotonin | 0.01045 | 0.01492 | 114.74 |

| 7 | 5-Hydroxyindoleacetaldehyde | 0.01045 | 0.01492 | 114.74 |

| 8 | 3,4-Dihydroxymandelaldehyde | 0.01194 | 0.01492 | 98.34 |

| 9 | S-Adenosylhomocysteine | 0.06679 | 0.07239 | 15.27 |

| 10 | S-Adenosylmethionine | 0.07239 | 0.07239 | 14.02 |

Multi-Omics Analysis by Enrichr-KG

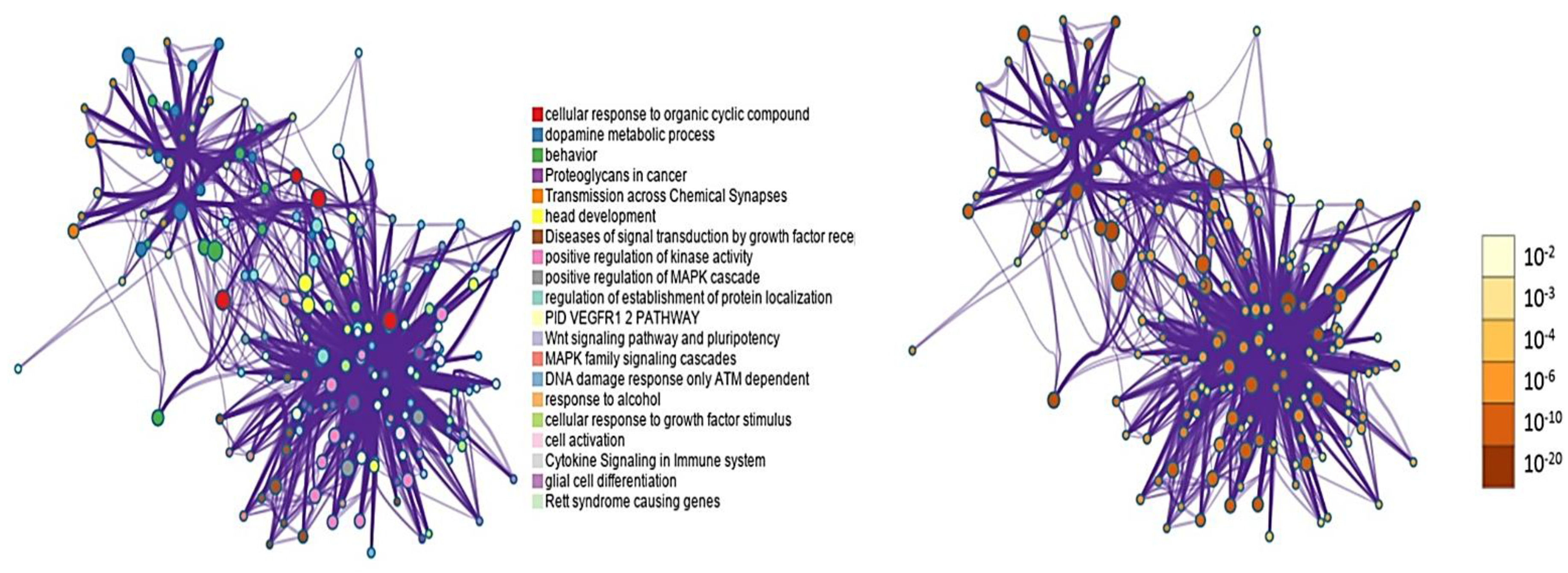

Meta-Analysis by Metascape

Pathway and Process Enrichment Analysis

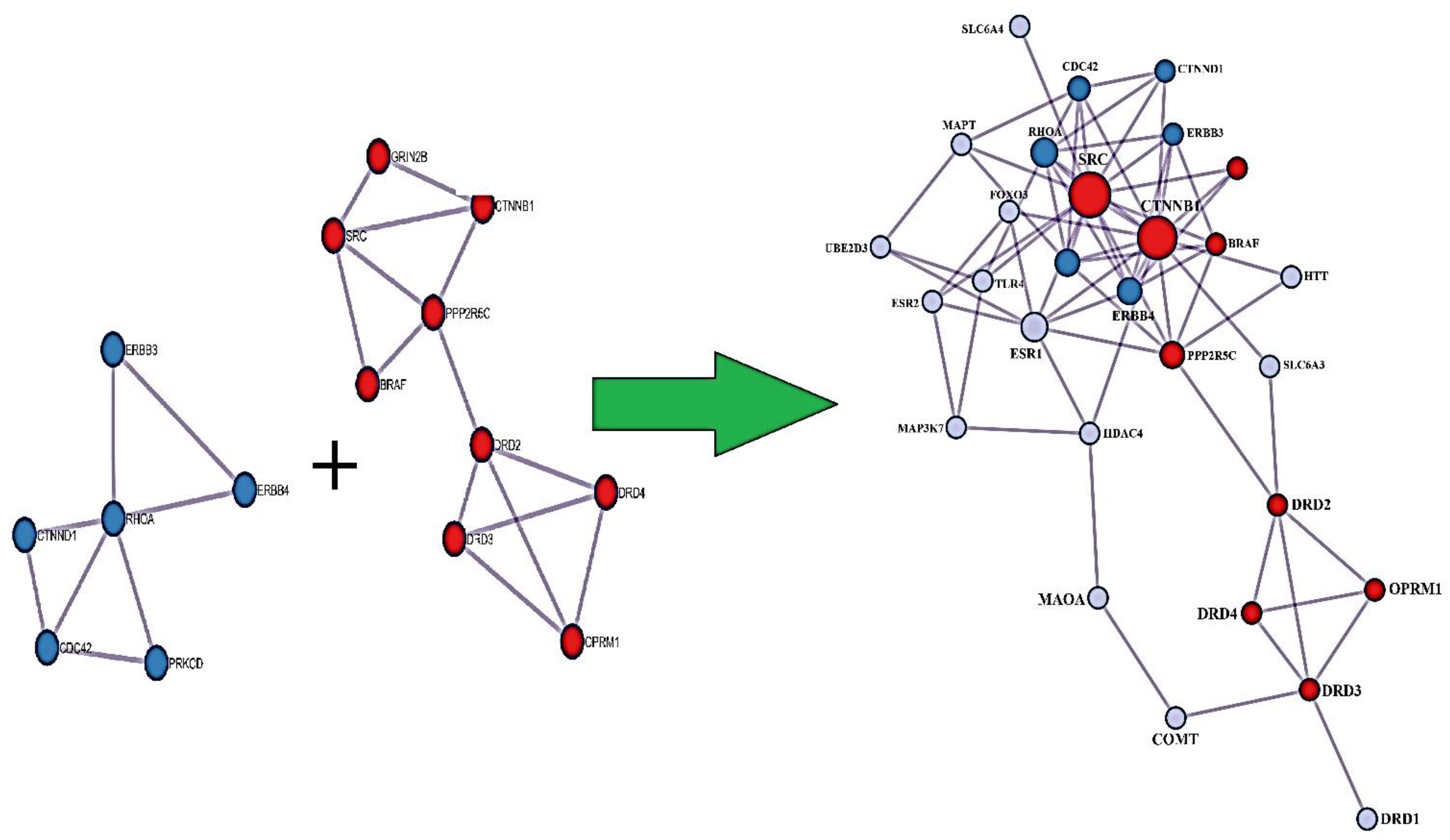

PPI Enrichment Analysis

PGx Variant Annotation Assessment (PGx-VAA)

Discussion

Clinical Relevance

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Author Contribution

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knopf, A. Autism prevalence increases from 1 in 60 to 1 in 54: CDC. The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter 2020, 36, 4–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cakir, J.; Frye, R.E.; Walker, S.J. The lifetime social cost of autism: 1990–2029. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2020, 72, 101502. [Google Scholar]

- Neggers, Y.H. Increasing Prevalence, Changes in Diagnostic Criteria, and Nutritional Risk Factors for Autism Spectrum Disorders. ISRN Nutr. 2014, 2014, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordan, R. Storni, and C.A. De Benedictis, Autism spectrum disorders: diagnosis and treatment. 2021.

- Harm, M., M. Hope, and A. Household, American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Anderson, J, Sapey, B, Spandler, H (eds), 2012, Distress or Disability?, Lancaster: Centre for Disability Research, www. lancaster. ac. uk. Arya. 347: p. 64.

- Mohapatra, A.N.; Wagner, S. The role of the prefrontal cortex in social interactions of animal models and the implications for autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1205199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyjek, M.; Bayer, M.; Dziobek, I. Reward responsiveness in autism and autistic traits–Evidence from neuronal, autonomic, and behavioural levels. NeuroImage: Clinical 2023, 38, 103442. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, E.; Allison, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Understanding the substance use of autistic adolescents and adults: a mixed-methods approach. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butwicka, A.; Långström, N.; Larsson, H.; Lundström, S.; Serlachius, E.; Almqvist, C.; Frisén, L.; Lichtenstein, P. Increased Risk for Substance Use-Related Problems in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 47, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grapel, J.N.; Cicchetti, D.V.; Volkmar, F.R. Sensory features as diagnostic criteria for autism: sensory features in autism. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 2015, 88, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, A.; Gal, E.; Fluss, R.; Katz-Zetler, N.; Cermak, S.A. Update of a Meta-analysis of Sensory Symptoms in ASD: A New Decade of Research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 4974–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J.I.; Cassidy, M.; Liu, Y.; Kirby, A.V.; Wallace, M.T.; Woynaroski, T.G. Relations between Sensory Responsiveness and Features of Autism in Children. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavăl, D. A Dopamine Hypothesis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dev. Neurosci. 2017, 39, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovaas, I.; Newsom, C.; Hickman, C. SELF-STIMULATORY BEHAVIOR AND PERCEPTUAL REINFORCEMENT. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1987, 20, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.A.; McDonough, S.G.; Bodfish, J.W. Evidence-Based Behavioral Interventions for Repetitive Behaviors in Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 42, 1236–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss-Feig, J.H.; Heacock, J.L.; Cascio, C.J. Tactile responsiveness patterns and their association with core features in autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasco, L.; Provenzano, G.; Bozzi, Y. Sensory Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Focus on the Tactile Domain, From Genetic Mouse Models to the Clinic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.H.; Knowlton, B.J. The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, G.A.; Balleine, B.W.; Whittle, L.; Guastella, A.J. Reduced goal-directed action control in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, G.S.; A Damiano, C.; A Allen, J. Reward circuitry dysfunction in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and genetic syndromes: animal models and clinical findings. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2012, 4, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, C.C. Evaluation of the social motivation hypothesis of autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry 2018, 75, 797–808. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Gao, X.; Yang, L. Repetitive Restricted Behaviors in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Mechanism to Development of Therapeutics. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 780407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, E.; McCallister, B.; Elman, D.J.; Freeman, R.; Borsook, D.; Elman, I. Validity of mental and physical stress models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 158, 105566–105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, I.; Borsook, D. Common Brain Mechanisms of Chronic Pain and Addiction. Neuron 2016, 89, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, I.; Borsook, D.; Volkow, N.D. Pain and suicidality: Insights from reward and addiction neuroscience. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 109, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, C.; Kohls, G.; Troiani, V.; Brodkin, E.S.; Schultz, R.T. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowirrat, A.; Elman, I.; A Dennen, C.; Gondré-Lewis, M.C.; Cadet, J.L.; Khalsa, J.; Baron, D.; Soni, D.; Gold, M.S.; McLaughlin, T.J.; et al. Neurogenetics and Epigenetics of Loneliness. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, ume 16, 4839–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Ashford, J.W.; Kateb, B.; Sipple, D.; Braverman, E.; Dennen, C.A.; Baron, D.; Badgaiyan, R.; Elman, I.; Cadet, J.L.; et al. Dopaminergic dysfunction: Role for genetic & epigenetic testing in the new psychiatry. J. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 453, 120809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, T.M. Oxytocin, motivation and the role of dopamine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 2014, 119, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M. Social circuits and their dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder. Molecular Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3194–3206. [Google Scholar]

- Marotta, R.; Risoleo, M.C.; Messina, G.; Parisi, L.; Carotenuto, M.; Vetri, L.; Roccella, M. The Neurochemistry of Autism. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Cui, W.; Xu, K.; Chen, D.; Hu, M.; Li, Z.; Geng, X.; Wei, S. Oxytocin and serotonin in the modulation of neural function: Neurobiological underpinnings of autism-related behavior. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 919890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, P.E. Autism Spectrum Disorders and Drug Addiction: Common Pathways, Common Molecules, Distinct Disorders? Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohls, G.; Schulte-Rüther, M.; Nehrkorn, B.; Müller, K.; Fink, G.R.; Kamp-Becker, I.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Schultz, R.T.; Konrad, K. Reward system dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2012, 8, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohls, G. Social ‘wanting’dysfunction in autism: neurobiological underpinnings and treatment implications. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders 2012, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Janouschek, H.; Chase, H.W.; Sharkey, R.J.; Peterson, Z.J.; Camilleri, J.A.; Abel, T.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Nickl-Jockschat, T. The functional neural architecture of dysfunctional reward processing in autism. NeuroImage: Clin. 2021, 31, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, C.C.; Ascunce, K.; Nelson, C.A. Ascunce, and C.A. Nelson, In context: A developmental model of reward processing, with implications for autism and sensitive periods. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2023, 62, 1200–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter, G.S.; Felder, J.N.; Green, S.R.; Rittenberg, A.M.; Sasson, N.J.; Bodfish, J.W. Reward circuitry function in autism spectrum disorders. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2010, 7, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottini, S. Social reward processing in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the social motivation hypothesis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 45, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almandil, N.B.; Alkuroud, D.N.; AbdulAzeez, S.; AlSulaiman, A.; Elaissari, A.; Borgio, J.F. Environmental and Genetic Factors in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Special Emphasis on Data from Arabian Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Choi, J.; Lee, W.J.; Do, J.T. Genetic and Epigenetic Etiology Underlying Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic-Maravic, V. Dopamine in autism spectrum disorders—focus on D2/D3 partial agonists and their possible use in treatment. Frontiers in psychiatry 2022, 12, 787097. [Google Scholar]

- Herborg, F.; Andreassen, T.F.; Berlin, F.; Loland, C.J.; Gether, U. Neuropsychiatric disease–associated genetic variants of the dopamine transporter display heterogeneous molecular phenotypes. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 7250–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCarlo, G.E.; Aguilar, J.I.; Matthies, H.J.; Harrison, F.E.; Bundschuh, K.E.; West, A.; Hashemi, P.; Herborg, F.; Rickhag, M.; Chen, H.; et al. Autism-linked dopamine transporter mutation alters striatal dopamine neurotransmission and dopamine-dependent behaviors. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3407–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosillo, P.; Bateup, H.S. Dopaminergic Dysregulation in Syndromic Autism Spectrum Disorders: Insights From Genetic Mouse Models. Front. Neural Circuits 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sato, Y.; Mohan, P.S.; Peterhoff, C.; Pensalfini, A.; Rigoglioso, A.; Jiang, Y.; A Nixon, R. Evidence that the rab5 effector APPL1 mediates APP-βCTF-induced dysfunction of endosomes in Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 21, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Y.; Benjamini, Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 1990, 9, 811–818. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, G.M.G. Corticostriatal connectivity and its role in disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, F.; Nakajima, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Yoshida, K.; Tsugawa, S.; Wada, M.; Ogyu, K.; Croarkin, P.E.; Blumberger, D.M.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; et al. Motor cortex excitability and inhibitory imbalance in autism spectrum disorder assessed with transcranial magnetic stimulation: a systematic review. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M.; Barsotti, N.; Bertero, A.; Trakoshis, S.; Ulysse, L.; Locarno, A.; Miseviciute, I.; De Felice, A.; Canella, C.; Supekar, K.; et al. mTOR-related synaptic pathology causes autism spectrum disorder-associated functional hyperconnectivity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, H. mTOR signalling pathway-A root cause for idiopathic autism? BMB reports 2019, 52, 424. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Qin, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, X.; Xie, D.; Zhao, Z.; Duan, S. mTOR Signaling Pathway Regulates the Release of Proinflammatory Molecule CCL5 Implicated in the Pathogenesis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 818518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Brodie, M.S.; Pandey, S.C.; Cadet, J.L.; Gupta, A.; Elman, I.; Thanos, P.K.; Gondre-Lewis, M.C.; Baron, D.; Kazmi, S.; et al. Researching Mitigation of Alcohol Binge Drinking in Polydrug Abuse: KCNK13 and RASGRF2 Gene(s) Risk Polymorphisms Coupled with Genetic Addiction Risk Severity (GARS) Guiding Precision Pro-Dopamine Regulation. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, M.; López, W.O.C.; Sharafshah, A.; Assefi, M.; Lewandrowski, K.-U. Personalized Medicine in Cancer Pain Management. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefi, M.; Lewandrowski, K.-U.; Lorio, M.; Fiorelli, R.K.A.; Landgraeber, S.; Sharafshah, A. Network-Based In Silico Analysis of New Combinations of Modern Drug Targets with Methotrexate for Response-Based Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, K.-U.; Sharafshah, A.; Elfar, J.; Schmidt, S.L.; Blum, K.; Wetzel, F.T. A Pharmacogenomics-Based In Silico Investigation of Opioid Prescribing in Post-operative Spine Pain Management and Personalized Therapy. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafshah, A.; Motovali-Bashi, M.; Keshavarz, P.; Blum, K. Synergistic Epistasis and Systems Biology Approaches to Uncover a Pharmacogenomic Map Linked to Pain, Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulating Agents (PAIma) in a Healthy Cohort. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafshah, A.; Motovali-Bashi, M.; Keshavarz, P. Pharmacogenomics-Based Detection of Variants Involved in Pain, Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulating Agents Pathways by Whole Exome Sequencing and Deep in Silico Investigations Revealed Novel Chemical Carcinogenesis and Cancer Risks. 50. [CrossRef]

- Sharafshah, A.; Lewandrowski, K.-U.; Gold, M.S.; Fuehrlein, B.; Ashford, J.W.; Thanos, P.K.; Wang, G.J.; Hanna, C.; Cadet, J.L.; Gardner, E.L.; et al. In Silico Pharmacogenomic Assessment of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP1) Agonists and the Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS) Related Pathways: Implications for Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Disorder. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2025, 23, 974–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, K.-U.; Blum, K.; Sharafshah, A.; Thanos, K.Z.; Thanos, P.K.; Zirath, R.; Pinhasov, A.; Bowirrat, A.; Jafari, N.; Zeine, F.; et al. Genetic and Regulatory Mechanisms of Comorbidity of Anxiety, Depression and ADHD: A GWAS Meta-Meta-Analysis Through the Lens of a System Biological and Pharmacogenomic Perspective in 18.5 M Subjects. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollis, E.; Mosaku, A.; Abid, A.; Buniello, A.; Cerezo, M.; Gil, L.; Groza, T.; Güneş, O.; Hall, P.; Hayhurst, J.; et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D977–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaie, H.; Rouz, S.K.; Kouchakali, G.; Heydarzadeh, S.; Asadi, M.R.; Sharifi-Bonab, M.; Hussen, B.M.; Taheri, M.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Rezazadeh, M. Identification of potential regulatory long non-coding RNA-associated competing endogenous RNA axes in periplaque regions in multiple sclerosis. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1011350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, R. Identification of miRNA-mRNA network in autism spectrum disorder using a bioinformatics method. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 2021, 71, 761–766. [Google Scholar]

- Atreya, R.V.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Z. Exploring drug-target interaction networks of illicit drugs. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Lang, Y.; Kong, L.; Lin, X.; Du, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H. The causal relationship between neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and other autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 959469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marballi, K.K.; Alganem, K.; Brunwasser, S.J.; Barkatullah, A.; Meyers, K.T.; Campbell, J.M.; Ozols, A.B.; Mccullumsmith, R.E.; Gallitano, A.L. Identification of activity-induced Egr3-dependent genes reveals genes associated with DNA damage response and schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Chen, H.; Jiang, F.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Wei, W.; Song, J.; Zhong, D.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of cuproptosis-related genes in immune infiltration in ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1077178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elasbali, A.M.; Abu Al-Soud, W.; Elayyan, A.E.M.; Al-Oanzi, Z.H.; Alhassan, H.H.; Mohamed, B.M.; Alanazi, H.H.; Ashraf, M.S.; Moiz, S.; Patel, M.; et al. Integrating network pharmacology approaches for the investigation of multi-target pharmacological mechanism of 6-shogaol against cervical cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 14135–14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ariyakumar, G.; Gupta, N.; Kamdar, S.; Barugahare, A.; Deveson-Lucas, D.; Gee, S.; Costeloe, K.; Davey, M.S.; Fleming, P.; et al. Identifying immune signatures of sepsis to increase diagnostic accuracy in very preterm babies. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J.; Saüch, J.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET cytoscape app: Exploring and visualizing disease genomics data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2960–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C. DrugBank 6.0: the DrugBank knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic acids research 2024, 52, D1265–D1275. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.P.; Grondin, C.J.; Johnson, R.J.; Sciaky, D.; Wiegers, J.; Wiegers, T.C.; Mattingly, C.J. Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD): update 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D1138–D1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Evangelista, J.E.; Xie, Z.; Marino, G.B.; Nguyen, N.; Clarke, D.J.B.; Ma’aYan, A. Enrichr-KG: bridging enrichment analysis across multiple libraries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W168–W179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. How to Reveal Magnitude of Gene Signals: Hierarchical Hypergeometric Complementary Cumulative Distribution Function. Evol. Bioinform. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, C.; Breitkreutz, B.J.; Reguly, T.; Boucher, L.; Breitkreutz, A.; Tyers, M. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D535–D539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türei, D.; Korcsmáros, T.; Saez-Rodriguez, J. OmniPath: guidelines and gateway for literature-curated signaling pathway resources. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 966–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wernersson, R.; Hansen, R.B.; Horn, H.; Mercer, J.; Slodkowicz, G.; Workman, C.T.; Rigina, O.; Rapacki, K.; Stærfeldt, H.H.; et al. A scored human protein–protein interaction network to catalyze genomic interpretation. Nat. Methods 2016, 14, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, G.D.; Hogue, C.W.V. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003, 4, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elman, I.; Lowen, S.; Frederick, B.B.; Chi, W.; Becerra, L.; Pitman, R.K. Functional Neuroimaging of Reward Circuitry Responsivity to Monetary Gains and Losses in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, I.; Ariely, D.; Mazar, N.; Aharon, I.; Lasko, N.B.; Macklin, M.L.; Orr, S.P.; Lukas, S.E.; Pitman, R.K. Probing reward function in post-traumatic stress disorder with beautiful facial images. Psychiatry Res. 2005, 135, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, I.; Borsook, D. The failing cascade: Comorbid post traumatic stress- and opioid use disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 103, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’bRien, C.P. Anticraving Medications for Relapse Prevention: A Possible New Class of Psychoactive Medications. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.A.; Hill-Smith, T.E.; Lucki, I. Buprenorphine prevents stress-induced blunting of nucleus accumbens dopamine response and approach behavior to food reward in mice. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 11, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, C.; Leknes, S.; Heilig, M. The partial µ-opioid agonist buprenorphine in autism spectrum disorder: a case report. J. Med Case Rep. 2022, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkin, J.A.; Zornberg, G.L.; Lukas, S.E.; Cole, J.O. Buprenorphine Treatment of Refractory Depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1995, 15, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, I.; Zubieta, J.-K.; Borsook, D. The missing p in psychiatric training: why it is important to teach pain to psychiatrists. Archives of general psychiatry 2011, 68, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, A.E.L.; Browning, M.; Drevets, W.C.; Furey, M.; Harmer, C.J. Dissociable temporal effects of bupropion on behavioural measures of emotional and reward processing in depression. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefer, M.E.; Voskanian, S.J.; Koob, G.F.; Pulvirenti, L. Effects of terguride, ropinirole, and acetyl-l-carnitine on methamphetamine withdrawal in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006, 83, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Chen, T.J.; Meshkin, B.; Waite, R.L.; Downs, B.W.; Blum, S.H.; Mengucci, J.F.; Arcuri, V.; Braverman, E.R.; Palomo, T. Manipulation of catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT) activity to influence the attenuation of substance seeking behavior, a subtype of Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS), is dependent upon gene polymorphisms: A hypothesis. Med Hypotheses 2007, 69, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotoula, V.; Stringaris, A.; Mackes, N.; Mazibuko, N.; Hawkins, P.C.; Furey, M.; Curran, H.V.; Mehta, M.A. Ketamine Modulates the Neural Correlates of Reward Processing in Unmedicated Patients in Remission From Depression. Biol. Psychiatry: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2022, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craske, M.G.; Meuret, A.E.; Ritz, T.; Treanor, M.; Dour, H.J. Treatment for Anhedonia: A Neuroscience Driven Approach. Depression Anxiety 2016, 33, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMakin, D.L.; Siegle, G.J.; Shirk, S.R. Positive Affect Stimulation and Sustainment (PASS) Module for Depressed Mood: A Preliminary Investigation of Treatment-Related Effects. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2010, 35, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, J.D. Can the “female protective effect” liability threshold model explain sex differences in autism spectrum disorder? Neuron 2022, 110, 3243–3262. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-W. Whole genome sequencing analysis identifies sex differences of familial pattern contributing to phenotypic diversity in autism. Genome Medicine 2024, 16, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Samaco, R.C.; Nagarajan, R.P.; Braunschweig, D.; LaSalle, J.M. Multiple pathways regulate MeCP2 expression in normal brain development and exhibit defects in autism-spectrum disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetit, R.; Hillary, R.F.; Price, D.J.; Lawrie, S.M. The neuropathology of autism: A systematic review of post-mortem studies of autism and related disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 129, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Database | Site | Software (version) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS data mining | GWAS catalog | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home | EMBL-EBI 2024 |

61 |

| PPIs | STRING-MODEL | https://string-db.org/ | STRING (12.0) |

54 |

| GRNs | GMIs (miRTarBase) | https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn /~miRTarBase/miRTarBase_2022/php/index.php | NetworkAnalyst (3.0) | 62 |

| Signaling | https://cytoscape.org/ | Cytoscape (3.10.1) | 63 | |

| DDCs | PDIs | https://go.drugbank.com/ | NetworkAnalyst (3.0) | 64 |

| PCIs | https://ctdbase.org/ | NetworkAnalyst (3.0) | 65 | |

| EA | Pathway Analysis | https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/ | Enrichr | 66 |

| GO | https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/ | Enrichr | 67 | |

| DDA | https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/ | Enrichr | 68 | |

| Multi-Omics | Genomics, Proteomics, Transcriptomics, Metabolomics, and Phenomics | https://maayanlab.cloud/enrichr-kg | Enrichr-KG |

69 |

| MA | CEO | https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1 | Metascape | 70 |

| PGx | VAA | https://www.pharmgkb.org/ | PharmGKB | 55 |

| Phenotype | GWAS CID | Associations (N) | Studies (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | EFO_0003756 | 1321 | 55 |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptom | EFO_0005426 | 40 | 12 |

| Autism | EFO_0003758 | 44 | 18 |

| Social Communication Impairment | EFO_0005427 | 21 | 2 |

| Asperger Syndrome | EFO_0003757 | 5 | 2 |

| Obsessive-compulsive Disorder | EFO_0004242 | 258 | 25 |

| Anorexia Nervosa | MONDO_0005351 | 268 | 25 |

| Tourette syndrome | EFO_0004895 | 220 | 14 |

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | EFO_0003888 | 1838 | 85 |

| Schizophrenia | MONDO_0005090 | 5049 | 159 |

| Intelligence | EFO_0004337 | 3846 | 41 |

| Behavior or Behavioral Disorder Measurement | EFO_0004782 | 14 | 17 |

| Bipolar Disorder | MONDO_0004985 | 1592 | 127 |

| Unipolar Depression | EFO_0003761 | 2668 | 299 |

| N | Index | Name | P-value | q-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KEGG | Dopaminergic synapse | 2.29E-13 | 3.65E-11 | 69.15 |

| 2 | Reactome | Signal Transduction R-HSA-162582 | 3.50E-13 | 1.50E-10 | 16.73 |

| 3 | KEGG | Proteoglycans in cancer | 1.24E-11 | 9.88E-10 | 43.24 |

| 4 | Reactome | Dopamine Receptors R-HSA-390651 | 2.05E-11 | 4.38E-09 | 3072.15 |

| 5 | Reactome | Disease R-HSA-1643685 | 3.34E-11 | 4.76E-09 | 13.88 |

| 6 | Panther | Dopamine receptor mediated signaling pathway Homo sapiens P05912 | 1.30E-11 | 6.49E-09 | 108.28 |

| 7 | Reactome | Transmission Across Chemical Synapses R-HSA-112315 | 6.36E-11 | 6.79 E-09 | 35.68 |

| 8 | Reactome | Diseases Of Signal Transduction By Growth Factor Receptors And Second Messengers R-HSA-5663202 | 3.39E-10 | 2.90 E-09 | 23.62 |

| 9 | KEGG | Rap1 signaling pathway | 6.20 E-10 | 3.29E-08 | 35.59 |

| 10 | KEGG | Adherens junction | 8.95E-10 | 3.56 E-08 | 76.56 |

| 11 | Reactome | Neurotransmitter Clearance R-HSA-112311 | 8.58E-10 | 6.11 E-08 | 511.9 |

| 12 | KEGG | Shigellosis | 2.17 E-09 | 6.89 E-08 | 30.15 |

| 13 | Reactome | Signaling By Receptor Tyrosine Kinases R-HSA-9006934 | 1.55 E-09 | 9.44 E-08 | 20.05 |

| 14 | Panther | CCKR signaling map ST Homo sapiens P06959 | 3.97 E-09 | 9.93 E-08 | 38.16 |

| 15 | Reactome | Neuronal System R-HSA-112316 | 3.39 E-09 | 1.81E-07 | 22.27 |

| 16 | KEGG | Alcoholism | 9.13 E-09 | 2.21 E-07 | 33.65 |

| 17 | KEGG | Cocaine addiction | 9.74 E-09 | 2.21 E-07 | 90.57 |

| 18 | Reactome | PI3K/AKT Signaling In Cancer R-HSA-2219528 | 9.71 E-09 | 3.99 E-07 | 50.18 |

| 19 | Reactome | Signaling By ERBB2 R-HSA-1227986 | 9.74 E-09 | 3.99 E-07 | 90.57 |

| 20 | KEGG | Chemokine signaling pathway | 3.55 E-07 | 7.05E-06 | 26.59 |

| 21 | Panther | Heterotrimeric G-protein signaling pathway-Gq alpha and Go alpha mediated pathway Homo sapiens P00027 | 4.88 E-07 | 8.13E-06 | 39.34 |

| 22 | KEGG | Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction | 5.72 E-07 | 1.01E-05 | 17.89 |

| 23 | KEGG | Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 8.67 E-07 | 1.38 E-05 | 34.84 |

| 24 | Panther | Angiogenesis Homo sapiens P00005 | 2.08 E-06 | 2.6 E-05 | 28.95 |

| 25 | Panther | Cadherin signaling pathway Homo sapiens P00012 | 2.72 E-06 | 2.72 E-05 | 27.34 |

| 26 | Panther | Adrenaline and noradrenaline biosynthesis Homo sapiens P00001 | 6.85 E-06 | 5.71 E-05 | 100.75 |

| 27 | Panther | EGF receptor signaling pathway Homo sapiens P00018 | 2.05 E-05 | 0.000147 | 29.11 |

| 28 | Panther | Integrin signaling pathway Homo sapiens P00034 | 8.33E-05 | 0.000521 | 20.06 |

| 29 | Panther | Ras Pathway Homo sapiens P04393 | 0.000149 | 0.000829 | 33.51 |

| 30 | Panther | Wnt signaling pathway Homo sapiens P00057 | 0.000753 | 0.003648 | 11.06 |

| Index | Name | P-value | q-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Dopamine Metabolic Process (GO:0042417) | 1.79E-13 | 1.72E-10 | 383.79 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Catecholamine Metabolic Process (GO:0006584) | 6.82E-12 | 3.29E-09 | 499.05 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Response To Ethanol (GO:0045471) | 4.52E-11 | 1.45E-08 | 307.03 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Neuron Projection (GO:0043005) | 2.40E-10 | 1.80E-08 | 20.6 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Dendrite (GO:0030425) | 1.18E-07 | 4.43E-06 | 22.81 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Response To Organic Cyclic Compound (GO:0014070) | 2.32E-08 | 5.58E-06 | 75.16 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Prepulse Inhibition (GO:0060134) | 3.04E-08 | 5.85E-06 | 1109.33 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Response To Cocaine (GO:0042220) | 6.07E-08 | 9.75E-06 | 739.52 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Axon (GO:0030424) | 5.21E-07 | 1.3E-05 | 24.84 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Regulation Of Dopamine Uptake Involved In Synaptic Transmission (GO:0051584) | 1.06E-07 | 1.46E-05 | 554.61 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Phospholipase C-activating G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling Pathway (GO:0007200) | 1.43E-07 | 1.72E-05 | 51.01 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Positive Regulation Of Neuron Death (GO:1901216) | 1.85E-07 | 1.88E-05 | 102.26 |

| GO Biological Process 2023 | Regulation Of Postsynaptic Membrane Potential (GO:0060078) | 2.08E-07 | 1.88E-05 | 98.95 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Kinase Binding (GO:0019900) | 4.19E-06 | 0.000624 | 13.11 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Membrane Raft (GO:0045121) | 0.000114 | 0.00213 | 18.47 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Focal Adhesion (GO:0005925) | 0.000253 | 0.003474 | 10.26 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Cell-Substrate Junction (GO:0030055) | 0.000278 | 0.003474 | 10.04 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Estrogen Response Element Binding (GO:0034056) | 9.72E-05 | 0.004419 | 178.23 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Monoamine Transmembrane Transporter Activity (GO:0008504) | 0.000119 | 0.004419 | 158.42 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Dynactin Binding (GO:0034452) | 0.000119 | 0.004419 | 158.42 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Sodium: Chloride Symporter Activity (GO:0015378) | 0.000168 | 0.00486 | 129.6 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Alkali Metal Ion Binding (GO:0031420) | 0.000196 | 0.00486 | 118.8 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Postsynaptic Neurotransmitter Receptor Activity (GO:0098960) | 0.000366 | 0.007792 | 83.84 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Protein Tyrosine Kinase Activity (GO:0004713) | 0.000433 | 0.008073 | 23 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | G Protein-Coupled Receptor Activity (GO:0004930) | 0.000506 | 0.008374 | 12.34 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Catenin Complex (GO:0016342) | 0.000803 | 0.008598 | 54.79 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Non-Motile Cilium (GO:0097730) | 0.000922 | 0.008641 | 50.87 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Bounding Membrane Of Organelle (GO:0098588) | 0.001183 | 0.009858 | 5.89 |

| GO Cellular Component 2023 | Ciliary Membrane (GO:0060170) | 0.001479 | 0.01109 | 39.55 |

| GO Molecular Function 2023 | Protein Kinase Binding (GO:0019901) | 0.000897 | 0.01336 | 7.69 |

| Index | Name | P-value | q-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DisGeNET | Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 5.14E-20 | 1.49E-16 | 129.86 |

| DisGeNET | Mental Depression | 4.20E-19 | 6.07E-16 | 45.49 |

| DisGeNET | Abnormal behavior | 1.00E-18 | 8.45E-16 | 54.94 |

| DisGeNET | Addictive Behavior | 1.17E-18 | 8.45E-16 | 77.55 |

| DisGeNET | Nonorganic psychosis | 2.45E-18 | 1.42E-15 | 73.01 |

| DisGeNET | Gambling, Pathological | 6.32E-18 | 2.70E-15 | 1215.26 |

| DisGeNET | Cognition Disorders | 6.54E-18 | 2.70E-15 | 67.41 |

| DisGeNET | Impulsive character (finding) | 8.69E-18 | 3.14E-15 | 237.31 |

| DisGeNET | Hyperactive behavior | 1.42E-17 | 4.57E-15 | 36.43 |

| DisGeNET | Nicotine Dependence | 1.64E-17 | 4.73E-15 | 101.74 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Substance abuse | 3.59E-17 | 6.38E-15 | 198.61 |

| GeDiPNet | Mental Depression | 3.40E-17 | 1.06E-14 | 30.01 |

| GeDiPNet | Mood Disorder | 3.44E-17 | 1.06E-14 | 58.89 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Alcohol dependence | 2.31E-16 | 2.06E-14 | 106.87 |

| GeDiPNet | Schizophrenia | 6.51E-15 | 1.34E-12 | 22.03 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Heroin dependence | 3.57E-13 | 2.12E-11 | 332.58 |

| GeDiPNet | Bipolar Disorder | 2.97E-13 | 4.57E-11 | 24.71 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Nicotine dependence | 1.18E-12 | 5.25E-11 | 131.82 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome | 7.85E-11 | 2.80E-09 | 118.62 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Cocaine dependence | 1.38E-10 | 4.10E-09 | 234.74 |

| GeDiPNet | Cognitive Disorder | 6.88E-11 | 8.46E-09 | 121.52 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Dementia | 4.01E-10 | 1.02E-08 | 53.96 |

| GeDiPNet | Status Marmoratus | 1.77E-10 | 1.81E-08 | 221.69 |

| Jensen DISEASES | obsessive-compulsive disorder | 1.23E-09 | 2.74E-08 | 142.44 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Major depressive disorder | 1.72E-09 | 3.41E-08 | 68.14 |

| Jensen DISEASES | Oppositional defiant disorder | 7.39E-09 | 1.20E-07 | 255.87 |

| GeDiPNet | Age-Related Memory Disorders | 4.95E-09 | 4.29E-07 | 104.91 |

| GeDiPNet | Memory Disorders | 5.57E-09 | 4.29E-07 | 102.21 |

| GeDiPNet | Autism | 2.05E-08 | 0.000001399 | 15.1 |

| GeDiPNet | Minimal Brain Dysfunction | 2.95E-08 | 0.000001677 | 170.53 |

| Term | Library | p-value | q-value | z-score | combined score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | DisGeNET | 5.14E-20 | 1.49E-16 | 129.9 | 5767 |

| Mental Depression | DisGeNET | 4.20E-19 | 6.07E-16 | 45.49 | 1925 |

| Abnormal behavior | DisGeNET | 1.00E-18 | 8.45E-16 | 54.94 | 2277 |

| Addictive Behavior | DisGeNET | 1.17E-18 | 8.45E-16 | 77.55 | 3202 |

| Nonorganic psychosis | DisGeNET | 2.45E-18 | 1.42E-15 | 73.01 | 2961 |

| dopamine metabolic process (GO:0042417) | GO_Biological_Process_2021 | 1.79E-13 | 1.82E-10 | 383.8 | 11260 |

| Dopaminergic synapse | KEGG_2021_Human | 2.29E-13 | 3.65E-11 | 69.15 | 2013 |

| Proteoglycans in cancer | KEGG_2021_Human | 1.24E-11 | 9.88E-10 | 43.24 | 1086 |

| catecholamine metabolic process (GO:0006584) | GO_Biological_Process_2021 | 1.59E-11 | 8.09E-09 | 399.2 | 9926 |

| regulation of dopamine uptake involved in synaptic transmission (GO:0051584) | GO_Biological_Process_2021 | 2.87E-10 | 9.73E-08 | 767.9 | 16870 |

| Rap1 signaling pathway | KEGG_2021_Human | 6.20E-10 | 3.29E-08 | 35.59 | 754.4 |

| Adherens junction | KEGG_2021_Human | 8.95E-10 | 3.56E-08 | 76.56 | 1595 |

| Shigellosis | KEGG_2021_Human | 2.17E-09 | 6.89E-08 | 30.15 | 601.5 |

| positive regulation of neuron death (GO:1901216) | GO_Biological_Process_2021 | 7.85E-09 | 2E-06 | 94.9 | 1771 |

| regulation of protein kinase B signaling (GO:0051896) | GO_Biological_Process_2021 | 1.91E-08 | 3.9E-06 | 30.08 | 534.7 |

| Neuroticism | GWAS_Catalog_2019 | 0.000057824 | 0.006743 | 22.11 | 215.7 |

| Bone mineral density (hip) | GWAS_Catalog_2019 | 0.000071735 | 0.006743 | 43.4 | 414.1 |

| BMI (adjusted for smoking behaviour) | GWAS_Catalog_2019 | 0.0002067 | 0.008483 | 29.87 | 253.5 |

| Extremely high intelligence | GWAS_Catalog_2019 | 0.0002147 | 0.008483 | 29.47 | 248.9 |

| Personality dimensions | GWAS_Catalog_2019 | 0.0002256 | 0.008483 | 109.7 | 920.7 |

| GO | Category | Description | Log10(P) | Log10(q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0071407 | GO Biological Processes | cellular response to organic cyclic compound | -15.64 | -11.30 |

| GO:0042417 | GO Biological Processes | dopamine metabolic process | -14.94 | -10.90 |

| GO:0007610 | GO Biological Processes | Behavior | -14.11 | -10.54 |

| hsa05205 | KEGG Pathway | Proteoglycans in cancer | -12.50 | -9.24 |

| R-HSA-112315 | Reactome Gene Sets | Transmission across Chemical Synapses | -11.42 | -8.34 |

| GO:0060322 | GO Biological Processes | head development | -11.37 | -8.34 |

| R-HSA-5663202 | Reactome Gene Sets | Diseases of signal transduction by growth factor receptors and second messengers | -11.13 | -8.21 |

| GO:0033674 | GO Biological Processes | positive regulation of kinase activity | -10.95 | -8.07 |

| GO:0043410 | GO Biological Processes | positive regulation of MAPK cascade | -10.74 | -7.87 |

| GO:0070201 | GO Biological Processes | regulation of establishment of protein localization | -10.23 | -7.44 |

| M237 | Canonical Pathways | PID VEGFR1 2 PATHWAY | -10.20 | -7.44 |

| WP399 | WikiPathways | Wnt signaling pathway and pluripotency | -9.16 | -6.54 |

| R-HSA-5683057 | Reactome Gene Sets | MAPK family signaling cascades | -9.11 | -6.52 |

| WP710 | WikiPathways | DNA damage response only ATM dependent | -8.93 | -6.38 |

| GO:0097305 | GO Biological Processes | response to alcohol | -8.30 | -5.82 |

| GO:0071363 | GO Biological Processes | cellular response to growth factor stimulus | -7.74 | -5.34 |

| GO:0001775 | GO Biological Processes | cell activation | -7.67 | -5.29 |

| R-HSA-1280215 | Reactome Gene Sets | Cytokine Signaling in Immune system | -7.35 | -5.02 |

| GO:0010001 | GO Biological Processes | glial cell differentiation | -7.21 | -4.91 |

| WP4312 | WikiPathways | Rett syndrome causing genes | -6.83 | -4.63 |

| GENE | CLINICAL RELEVANCE | SOURCE | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTNNB1 | CTNNB1 neurodevelopmental disorder (CTNNB1-NDD) is characterized in all individuals by mild-to-profound cognitive impairment | PMID: 35593792. | Up to 39% of reported individuals by exudative vitreoretinopathy, an ophthalmologic finding consistent with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR). |

| ESR1 | There is evidence for the role of Esr1+ neurons in aversion and sexually dimorphic stress sensitivity. | PMC10322719 |

Excitatory projections from the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) to the lateral habenula (LHb) drive aversive responses |

| RHOA | Knockdown of RhoA in the dHIP enhanced METH-induced CPP, whereas RhoA overexpression attenuated the effects of METH. | PMID: 34313802. | Findings indicate that the miR-31-3p/RhoA pathway in the dHIP modulates METH-induced CPP in mice. Results highlight the potential role of epigenetics represented by non-coding RNAs in the treatment of METH addiction. |

| CDC42 | cdc42-activated, nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, Ack1, is a DAT endocytic brake that stabilizes DAT at the plasma membrane and is released in response to PKC activation. | PMID: 26621748 |

Findings reveal a unique endocytic control switch that is highly specific for DAT. |

| FOXO3 | Forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) family to be a downstream mechanism through which SIRT1 regulates cocaine action. | PMID: 25698746 |

Overexpressing FOXO3 in NAc enhances cocaine place conditioning |

| MAP3K7 | The multi-component and multi-target properties of Acanthopanax senticosus (AS) play an important role in the alleviation of anxiety and memory impairment caused by AD, and the mechanism is involved in the phosphorylation and activation of the MAPK signaling pathway. | PMID: 38545117 |

The levels of MAP3K7 and P38 phosphorylation increased, and there was also an increase in the expression of HSP27 proteins. |

| PRKCD | It was reported that social choice-induced voluntary abstinence prevents incubation of methamphetamine craving in rats. This inhibitory effect was associated with activation of protein kinase-Cδ (PKCδ)-expressing neurons in central amygdala lateral division (CeL). | PMID: 32205443 |

shPKCδ CeL injections decreased Fos in CeL PKCδ-expressing neurons, increased Fos in CeM output neurons, and reversed the inhibitory effect of social choice-induced abstinence on incubated drug seeking on day 15. |

| ERBB4 | Natural genetic variants of Neuregulin1 (NRG1) and its cognate receptor ErbB4 are associated with a risk for schizophrenia. | PMID: 32354758 |

Findings indicate that ErbB4 signaling affects tonic DA levels and modulates a wide array of behavioral deficits relevant to psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia. |

| UBE2D3 | It is well known that dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome protein degradation system (UPPDS) is one of the major mechanisms of the pathogenesis of PD. | PMID: 24993970 |

Decreasing transcript levels of genes may indicate decrease in the efficiency of the UPPDS on the whole which in turn may lead to the accumulation of abnormal proteins and toxic protein aggregates and subsequent death of the neurons. |

| MAPT |

MAPT involves myelination, neurite elongation and guidance in cytoskeletal organization and is involved in structural connectivity |

PMID: 38438384 |

Structural connectivity measures are highly polygenic |

| CTNND1 | Functional and positional QTL gene-based approaches identified 249 significant candidate risk genes for OCD, of which 25 were identified as putatively causal, highlighting WDR6, DALRD3, CTNND1 & genes in the MHC region | doi: 10.1101/2024.03.13.24304161. | Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects ~1% of the population and exhibits a high SNP-heritability |

| HDAC4 | One family of epigenetic molecules that may regulate maladaptive behavioral changes produced by cocaine use are the histone deacetylases (HDACs)-key regulators of chromatin and gene expression. In particular, class IIa HDACs (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7 and HDAC9) respond to changes in neuronal activity by modulating their distribution between the nucleus and cytoplasm-a process controlled in large part by changes in phosphorylation of conserved residues. | PMID: 28635037 |

Despite high sequence homology, HDAC4 and HDAC5 are oppositely regulated by cocaine-induced signaling in vivo and have distinct roles in regulating cocaine behaviors. |

| BRAF | Expressing BRAF K499E (KE) in neural stem cells under the control of a Nestin-Cre promoter (Nestin;BRAFKE/+) induced hippocampal memory deficits | PMID: 39964758 |

Results demonstrate that ERK hyperactivity contributes to astrocyte dysfunction associated with Ca2+ dysregulation, leading to memory deficits of BRAF-associated RASopathies. |

| ESR2 | Studies indicates that the epigenetic dysregulation of ESR2 may govern the development of autism. | PMID: 28299627 |

Detailed analyses revealed that eight specific CpG sites were hypermethylated in autistic individuals and that four specific CpG sites were positively associated with the severity of autistic symptoms. |

| PPP2R5C | Pathogenic variants resulting in protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) dysfunction resulting in mild to severe neurodevelopmental delay. | PMID: 39978342 |

PPP2R5C total loss-of-function variants could be inherited from a non-symptomatic parent. This implies that a dominant-negative mechanism on substrate dephosphorylation or general PP2A function is the most likely pathogenic mechanism. |

| ERBB3 | Significant gene-gene interactions were found between (i) NRG1*MBP (perm p-value = 0.002) in the SSD trios sample, (ii) ERBB3*AKT1 (perm p-value = 0.001) in the SSD case-control sample, and (iii) ERBB3*QKI (perm p-value = 0.0006) in the ASD trios sample. | PMID: 34338147 |

Schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (SSD) and Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders that share clinical, cognitive, and genetic characteristics, as well as particular white matter (WM) abnormalities. |

| TLR4 | After TLR4 activation, CD14+ monocytes from autistic children produced increased IL-6 compared to monocytes from children with typical development. IL-6 concentration also correlated with worsening restrictive and repetitive behaviors. | PMID: 35203983 |

Findings suggest dysfunctional activation of myeloid cells, and may indicate that other cells of this lineage, including macrophages, and microglia in the brain, might have a similar dysfunction. |

| HTT | Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) results in cerebral cortical dysgenesis. AE inhibited Bcl11a, Htt, Ctnnb1, and other upstream regulators of differentially expressed genes and inhibited several autism-linked genes, suggesting that neurodevelopmental disorders share underlying mechanisms. | PMID: 33997709 |

Episodic PAE persistently alters the developing neural transcriptome, contributing to sex- and cell-type-specific teratology. |

| SRC | Src protein tyrosine kinase plays an important role Opioid addiction | PMID: 34243625 |

Src inhibitors have the potential to be used in combination with opioids to achieve synergy |

|

GRIN2B. |

The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors play important roles in the pathophysiology of substance dependence (SD). Results from gene-based association tests showed that the association signal derived mostly from GRIN2B. | PMID: 23855403 |

Rare variants (RVs) with minor allele frequency <1% in the NMDAR-related genes influence the risk of OD |

| GARS GENES | The GARS panel can accurately predict preaddiction | PMID: 28930612 |

Genetically identifying risk for all RDS behaviors, especially in compromised populations, may be a frontline tool to assist municipalities to provide better resource allocation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).