Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenological Observation of Macadamia

2.2. Dynamics of Endogenous Hormones in Macadamia

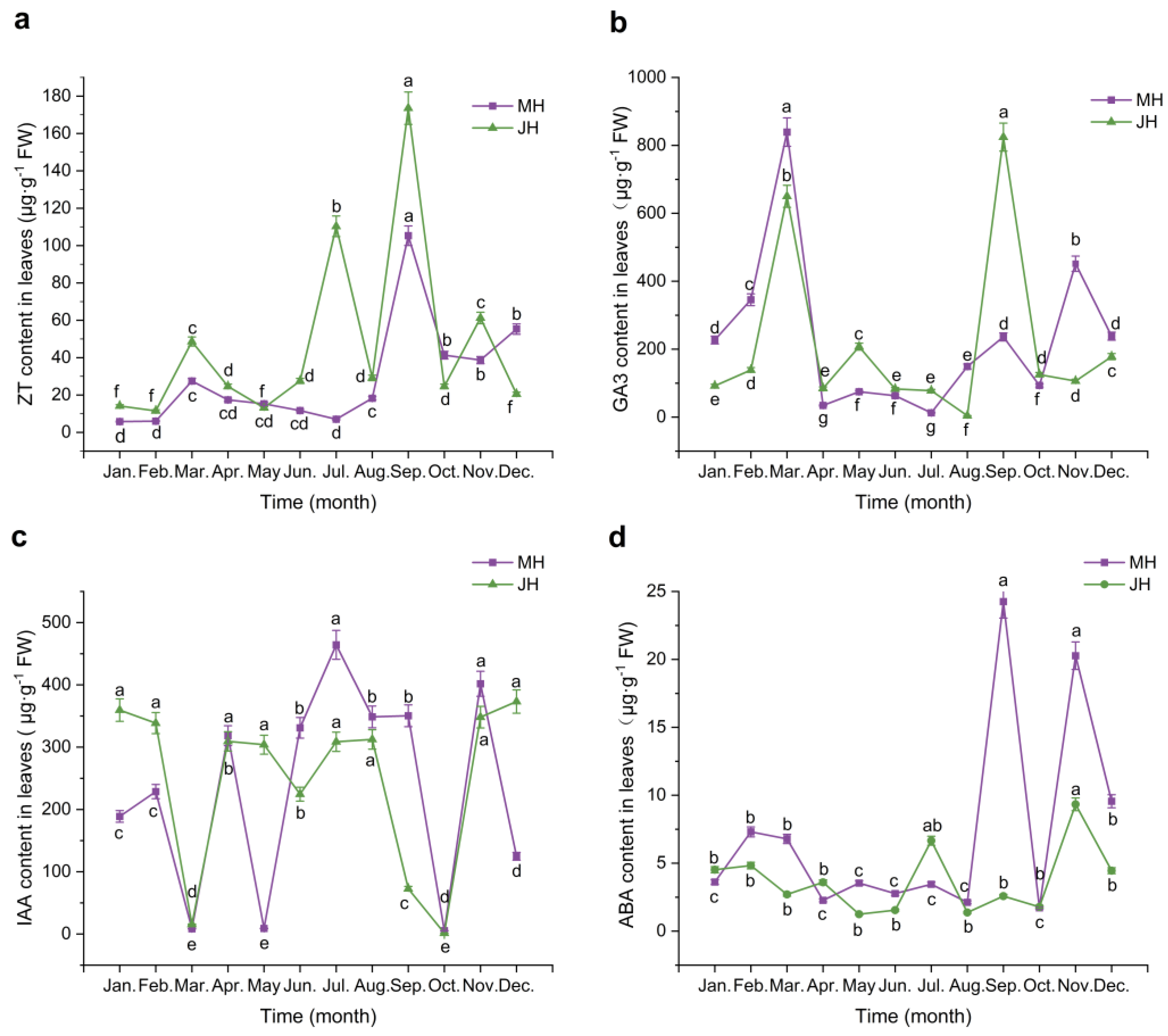

2.2.1. Dynamic Changes of Endogenous Hormones in Leaves

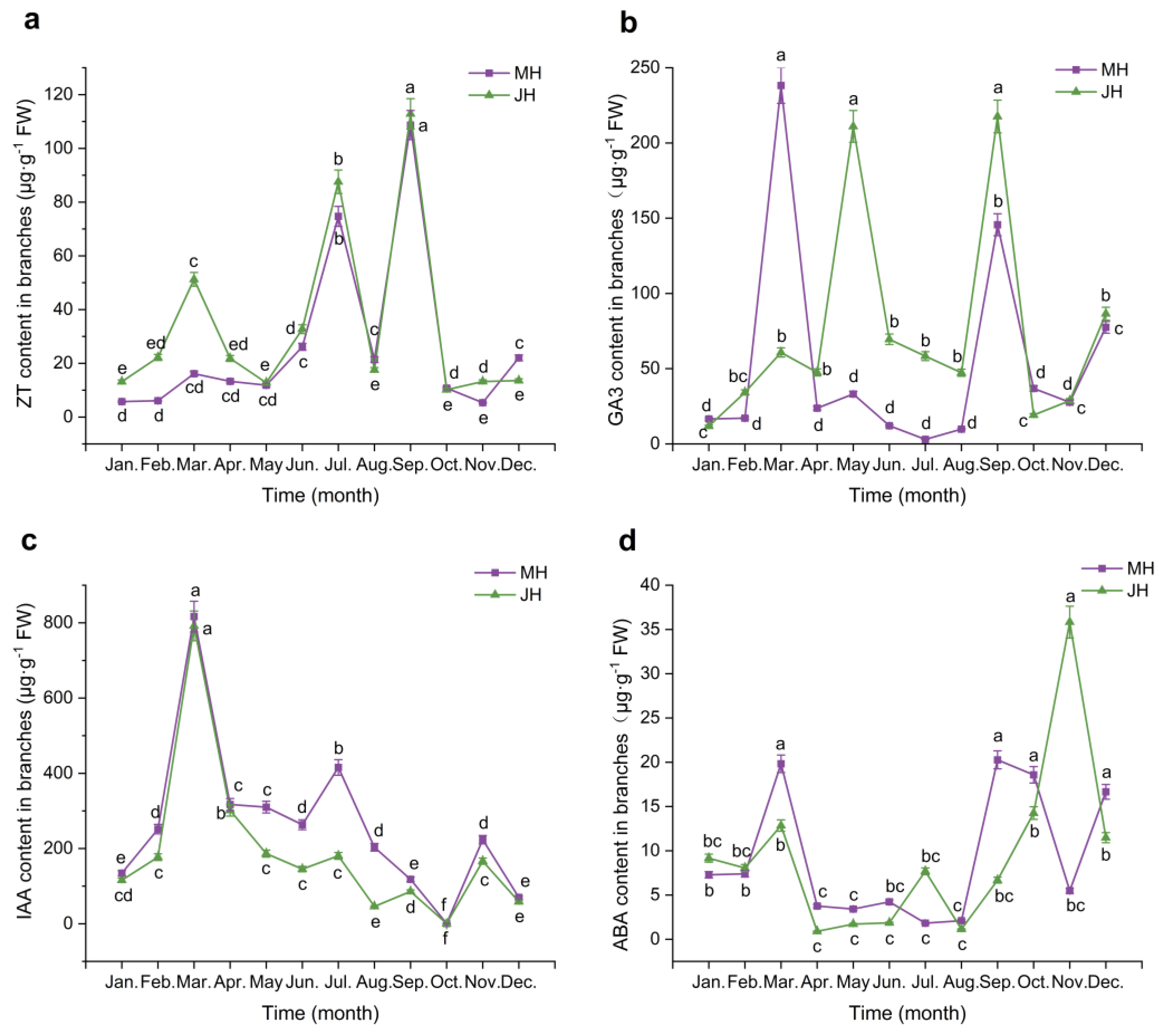

2.2.2. Dynamic Changes of Endogenous Hormones in Branches

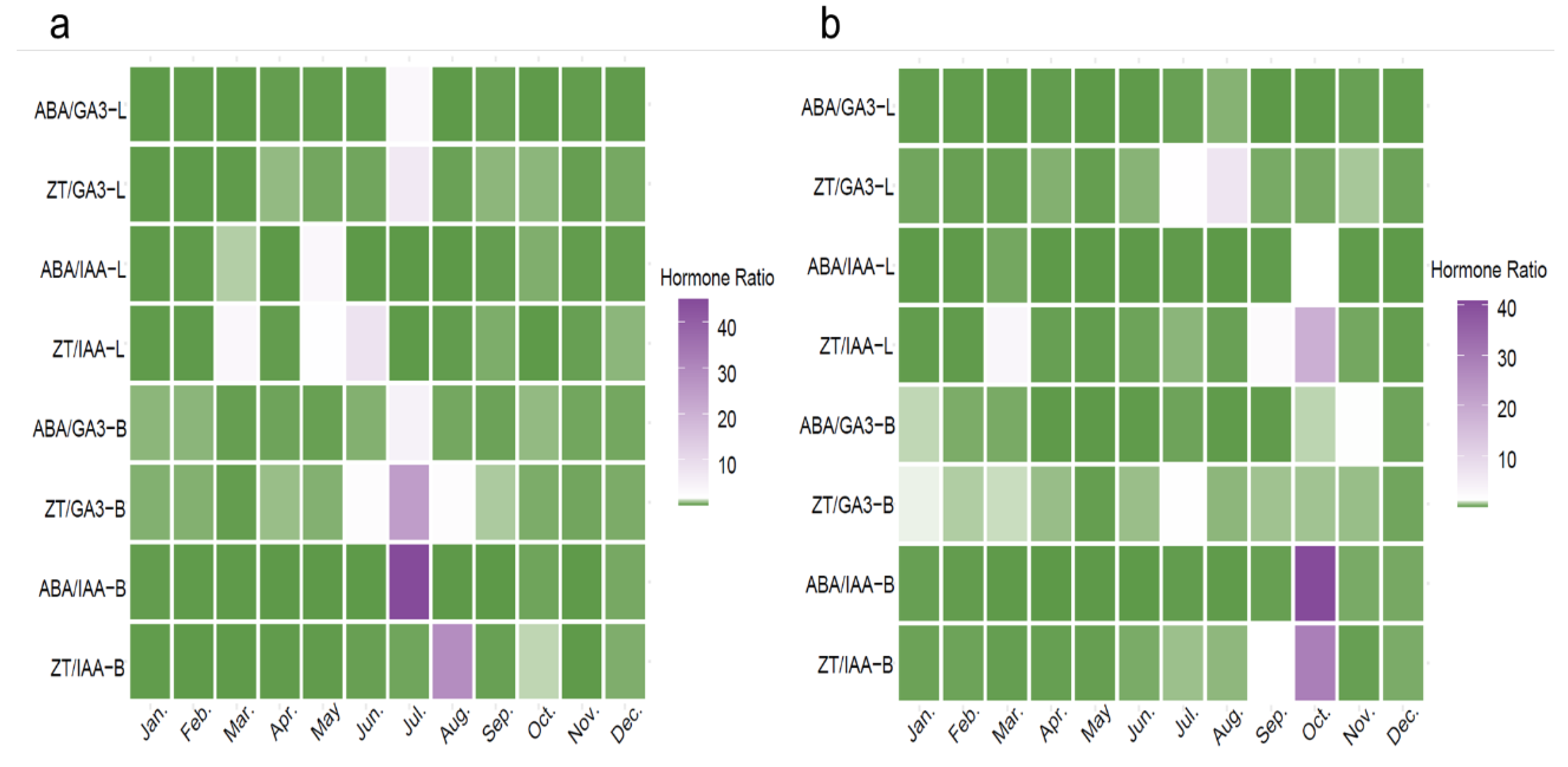

2.3. Dynamic Changes in the Endogenous Hormone Balance Ratios in Macadamia

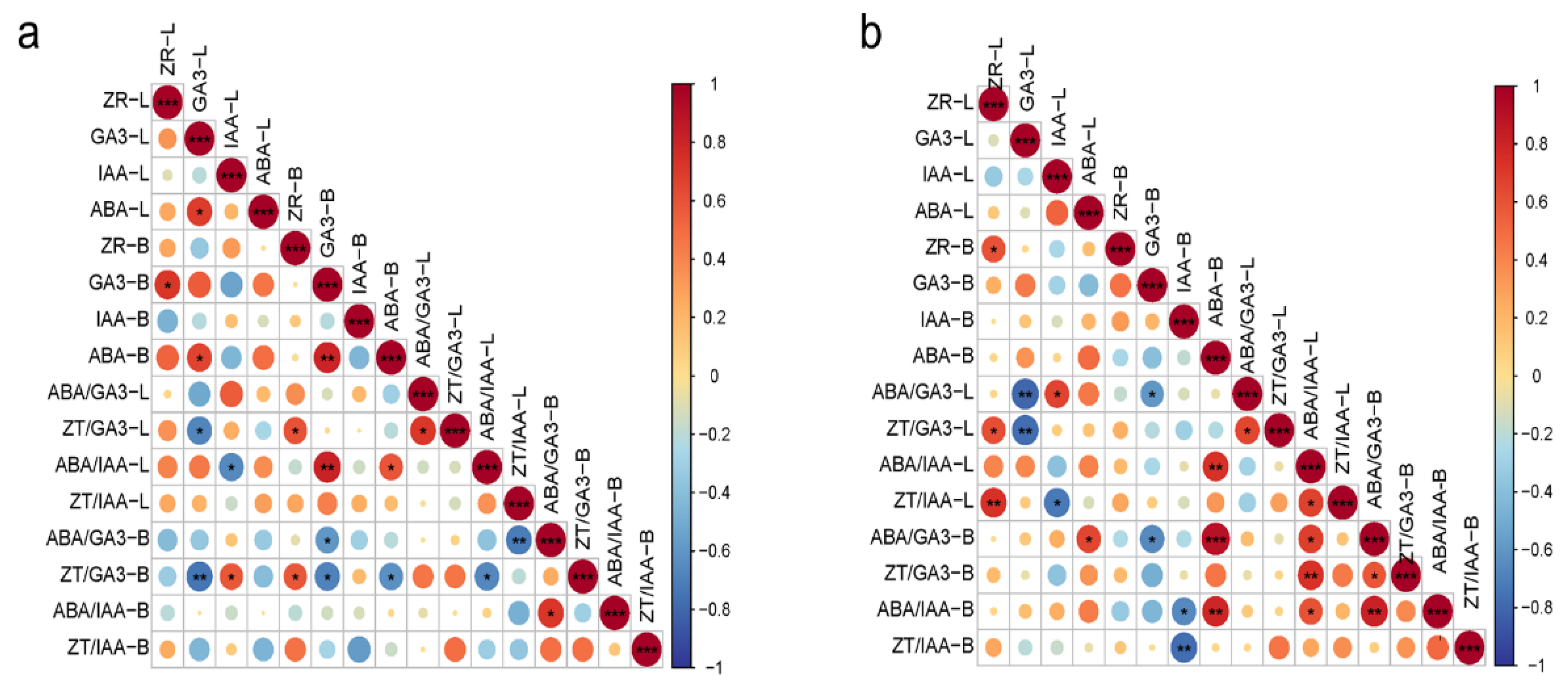

2.4. Correlation Analysis of Endogenous Hormones and Their Ratios in Macadamia

3. Discussion

3.1. Relationship Between Endogenous Hormone Dynamics and Off-Season Flowering in Macadamia

3.2. Relationship between Endogenous Hormone Balance Ratios in Macadamia and Off-Season Flowering

3.3. Synergistic Effects of Endogenous Hormones in Macadamia and the Mechanism of Flowering Regulation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Site Description

4.2. Field Experiment Layout and Sample Collection

4.3. Field Experiment Layout and Sample Collection

4.3.1. Sample Preparation Method

4.3.2. Measurement Method

4.4. Data Processing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahman, A.; Wang, S.; Yan, J. S.; Xu, H. R. Intact macadamia nut quality assessment using near-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 104033. [CrossRef]

- Appleby, N.; Edwards, D.; Batley, J. New technologies for ultrahigh throughput genotyping in plants. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 513, 19–39. [CrossRef]

- Malvestiti, R.; Borges, L.S.; Weimann, E.; et al. The effect of macadamia oil intake on muscular inflammation and oxidative profile kinetics after exhaustive exercise. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1600382. [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; Tao, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Overview and development trends of the global macadamia industry. South China Fruits. 2015, 44(4), 5. [CrossRef]

- Sedgley, M.; Olesen, T. Flowering and fruit-set in macadamias (Macadamia integrifolia): Studies on temporal patterns and sources of yield fluctuation. Scientia Horticulturae 1992, 50(1–2), 107–118.

- Trueman, S.J. The reproductive biology of macadamia. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 150, 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Yue, H.; et al. Investigation of flowering rhythm and preliminary study on flowering period reg-ulation in macadamia in Yunnan. Tropical Agricultural Science and Technology. 2024, 47(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Maple, R.; Zhu, P.; Hepworth, J.; Wang, J.-W.; Dean, C. Flowering time: From physiology, through genetics to mechanism. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195(1), 190–212. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.Q.; Ahmad, S.; Cheng, T.R.; et al. Red to far-red light ratio modulates hormonal and genetic control of axillary bud outgrowth in Chrysanthemum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19(6), 1590. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Maness, N.; Ferguson, L.; et al. Role of plant hormones in flowering and exogenous hormone application in fruit/nut trees: A review of pecans. Fruit Res. 2021, 1(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qi, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; An, N.; et al. Comparative RNA-sequencing–based transcriptome profiling of buds from profusely flowering ‘Qinguan’ and weakly flowering ‘Nagafu no. 2’ apple varieties reveals novel insights into the regulatory mechanisms underlying floral induction. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 370. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, S.; Singh, V.P.; Tripathi, D.K.; et al. Plant responses to metal stress: the emerging role of plant growth hormones in toxicity alleviation. In: Ahmad, P.; Rasool, S., Eds.; Emerging Technologies and Management of Crop Stress Tolerance; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 215–248. [CrossRef]

- O Okada, K.; Ueda, J.; Komaki, M.K.; Bell, C.J.; Shimura, Y. Requirement of the auxin polar transport system in early stages of Arabidopsis floral bud formation. Plant Cell 1991, 3(7), 677–684. [CrossRef]

- Dar, N.A.; Amin, I.; Wani, W.; et al. Abscisic acid: A key regulator of abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Gene 2017, 11, 106–111. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, H.B.; Du, L.Q.; et al. Effect of spraying gibberellin on the flower bud formation of Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia). J. Fruit Sci. 2008, 25(2), 203–208. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Han, M.; Ma, F.; Shu, H. Effect of bending on the dynamic changes of endogenous hormones in shoot terminals of ‘Fuji’ and ‘Gala’ apple trees. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.Y.; Zhang, J.C.; Wei, L.H. Changes in endogenous hormones during floral bud development in apple. Journal of Fruit Science. 2000, 17(4), 244–248. [CrossRef]

- Mutasa-Göttgens, E.; Hedden, P. Gibberellin as a factor in floral regulatory networks. Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 60, Issue 7, May 2009, Pages 1979–1989. [CrossRef]

- Werner, T.; Motyka, V.; Laucou, V.; et al. Cytokinin-deficient transgenic Arabidopsis plants show multiple developmental alterations indicating opposite functions of cytokinins in the regulation of shoot and root meristem activity. Plant Cell 2001, 13(11), 2539–2551. [CrossRef]

- Zwack, P.J.; Rashotte, A.M. Interactions between cytokinin signalling and abiotic stress responses. Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 66, Issue 16, August 2015, Pages 4863–4871. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; Hoad, G.V. Cytokinin application induces flowering on defoliated pear spurs: evidence from Zeatin experiments. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3215–3222. [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Ueda, N.; Aoki, K.; et al. AtIPT3 is a key determinant of nitrate-dependent cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant and Cell Physiology, Volume 45, Issue 8, 15 August 2004, Pages 1053–1062. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Hormone profiling and ratio dynamics define floral fate in apple. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 1782–1796. [CrossRef]

- Leibfried, A.; To, J.P.C.; Busch, W.; et al. WUSCHEL controls meristem function by direct regulation of cytokinin-inducible response regulators. Nature 2005, 438(7071), 1172–1175. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Sheen, J.; Müller, B. Cytokinin signaling networks. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 353–380. [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Behringer, C.; Zourelidou, M.; Schwechheimer, C. Convergence of auxin and gibberellin signaling on regulation of GNC and GNL in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13192–13197. [CrossRef]

- de Lucas, M.; Davière, J.M.; Rodríguez Fernández, M.; et al. A molecular framework for gibberellin control of cell division and expansion in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 2156–2165. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.O.; Park, H.M.; Lee, H.I. SOC1 translocated to the nucleus by interaction with AGL24 directly regulates LEAFY.The Plant Jorrnal. 2008, 55(5), 832–843. [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Zhu, L.; Shen, L.; et al. Gibberellin regulates Arabidopsis floral initiation through modulation of SOC1 and LEAFY expression. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1553–1565.

- Zeng, H.; Du, L.Q.; Zou, M.H.; et al. Changes in endogenous hormone levels during floral bud differentiation in macadamia. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2008, 36(34), 14949–14953. [CrossRef]

- Kotake, T.; Nakagawa, N.; Takeda, K.; Sakurai, N. Auxin-induced elongation growth and expressions of cell wall-bound exo- and endo-β-glucanases in barley coleoptiles. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000, 41, 1272–1278. [CrossRef]

- Jung, C. Flowering time regulation: Agrochemical control of flowering. Nat. Plants 2017, 3(4), 17045. [CrossRef]

- Brunoud, G.; Wells, D.; Oliva, M.; et al. A novel sensor to map auxin response and distribution at high spatio-temporal resolution. Nature 2012, 482, 103–107. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Chen, X.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of topping-induced axillary shoot outgrowth in Nicotiana tabacum. Gene 2018, 646, 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Abscisic acid modulates floral transition by interacting with flowering pathway integrators FT and SOC1 in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 638123.

- Shu, K.; Zhou, W.; Chen, F.; Luo, X.; Yang, W. Abscisic acid and gibberellins antagonistically mediate plant development and abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 416. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, U.; et al. Hormonal crosstalk: a central regulator in plant stress signaling. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174(2), 106–121.

- Zhang, S.; Han, M.; Ma, F.; et al. Effect of exogenous GA₃ and its inhibitor paclobutrazol on floral formation, endogenous hormones, and flowering-associated genes in ‘Fuji’ apple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 107, 178–186. [CrossRef]

- Shalom, L.; Samuels, S.; Zur, N.; et al. Fruit load induces changes in global gene expression and in abscisic acid (ABA) and indole acetic acid (IAA) homeostasis in citrus buds. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65(12), 3029–3044. [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; et al. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23(10), 680–694. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, M.; Altmann, S.; Rodriguez, P.A.; et al. Extensive signal integration by the phytohormone protein network. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.W.; Wu, X.M.; Deng, X.X.; et al. Advances in Citrus Flowering: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 868831. [CrossRef]

- Vanstraelen, M.; Benková, E. Hormonal interactions in the regulation of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 28, 463–487. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Setiawan, S.; Omega, E.; et al. Correlation-based hormone network analysis reveals IAA and GA₃ as central inte-grators of floral induction. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 281, 109976. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Wei, D.; et al. Hormonal interactions in grapevine flowering regulation: insights from IAA–GA synergy. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 114.

- Moubayidin, L.; Di Mambro, R.; Sabatini, S. Cytokinin–auxin crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14(10), 557–562. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Winter, C.M.; Wu, M.F.; et al. A molecular framework for auxin-mediated initiation of flower primordia. Dev. Cell 2009, 16(5), 765–777. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P. Hormone crosstalk during flower development: Insights from transcriptome analysis in grapevine. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 421.

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Hormonal crosstalk regulates flowering time under stress conditions: A comparative study in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 199, 107795. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.Y. Study on tissue culture and endogenous hormone content of Lagerstroemia ‘Zijingling’. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Sampling Site | Initial Flowering Period | Peak Flowering Period | Fruit Enlargement Period | Fruit Oil Accumulation Period | Maturity & Harvest | Floral Bud Dormancy Break Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH | Oct–Nov | Jan | Feb–Apr | May–Jul | Aug | Aug–Sep |

| JH | Jan–Feb | Mar | Apr–May | Jun–Aug | Sep | Oct–Dec |

| Time (min) |

Acetonitrile (%) |

Methanol (%) |

0.1% Phosphoric Acid (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 90 |

| 10 | 12 | 12 | 76 |

| 20 | 22 | 22 | 56 |

| 30 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| 35 | 5 | 5 | 90 |

| 40 | 5 | 5 | 90 |

| Component | Regression Equation | Correlation Coefficient | Linear Range (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZT | y = 43743x + 249867 | 0.999 | 0.203–208.077 |

| GA₃ | y = 9769.6x + 85522 | 0.996 | 0.202–206.848 |

| IAA | y = 75525x + 17728 | 0.999 | 0.202–206.848 |

| ABA | y = 18902x - 18636 | 0.999 | 0.204–209.715 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).