Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Laboratory Setting and Clinical Specimens

2.4. Microbiology Methods

- Culture

- Molecular Methods

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

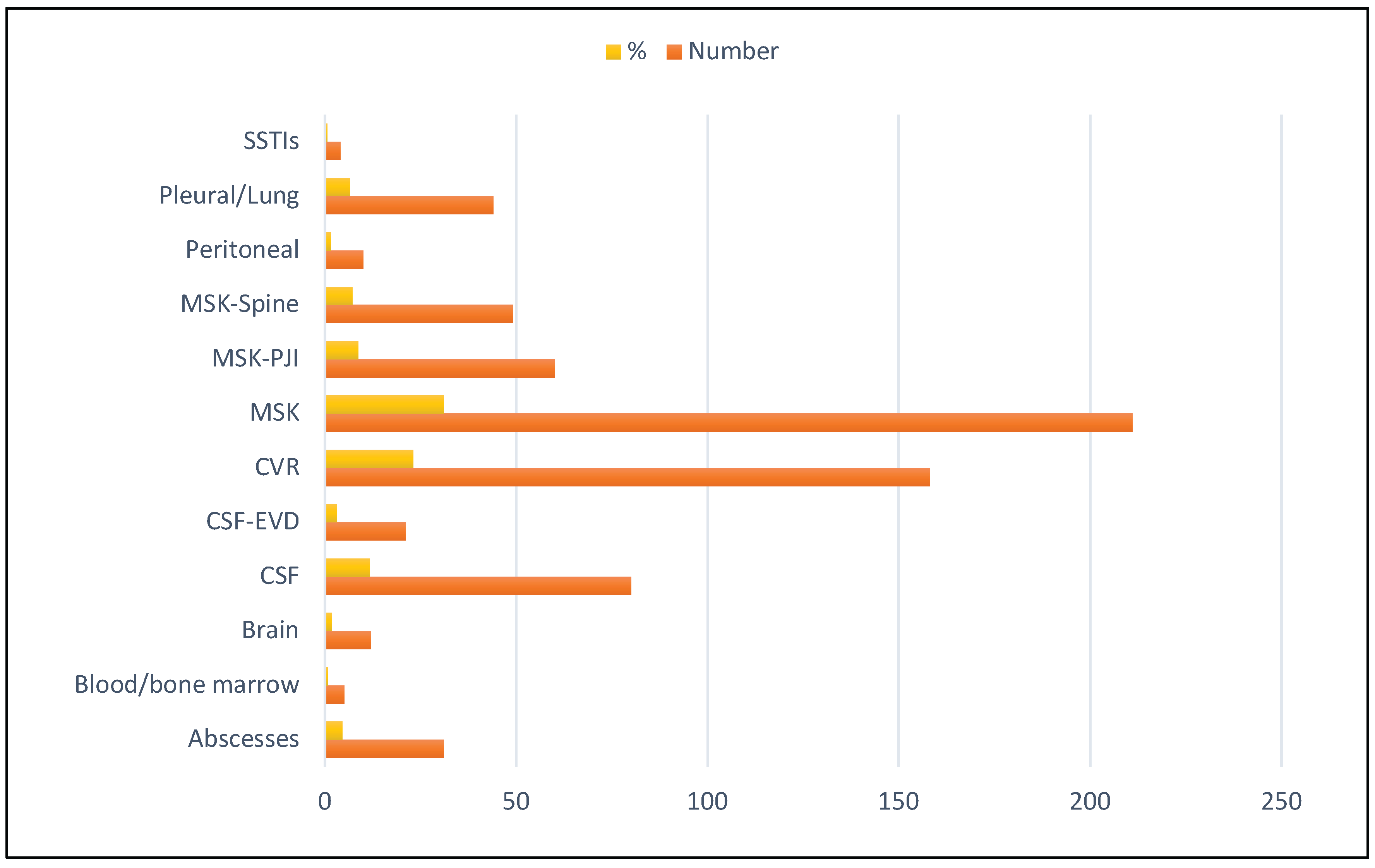

3.2. Distribution of Clinical Specimens

3.3. Performance of BR 16S PCR Compared to Culture

3.4. Performance of Acceptance Criteria for Prediction of Molecular Assay Result

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BR 16S PCR | Broad range BR 16S PCR rDNA polymerase chain reaction and Sanger sequencing |

| BR 16S PCR rRNA gene | BR 16S PCR ribosomal ribonucleic acid gene |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| APL | Alberta precision laboratories |

| DSC | Diagnostic and Scientific centre |

| BA | Blood agar |

| BBA | Brucella blood agar |

| CHOC | Chocolate agar |

| MAC | MacConkey agar |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix assisted laser desorption-time of flight mass spectrometry |

| MSK | Musculoskeletal |

| PJI | Prosthetic joint infection |

| CVR | Cardiovascular |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| SSTI | Skin and soft tissue infection |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| WBC | White blood cell count |

| PMN | Polymorphonuclear |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| NPV | Negative prediction value |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| RR | Relative risk |

| tMGS | Targeted metagenomics |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

References

- Branda, J. A.; Rychert, J.; Burnham, C. A.; Bythrow, M.; Garner, O. B.; Ginocchio, C. C.; Jennemann, R.; Lewinski, M. A.; Manji, R.; Mochon, A. B.; et al. Multicenter validation of the VITEK MS v2.0 MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry system for the identification of fastidious gram-negative bacteria. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2014, 78, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Chung, H. S.; Moon, H. W.; Lee, S. H.; Lee, K. Comparative evaluation of two matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems, Vitek MS and Microflex LT, for the identification of Gram-positive cocci routinely isolated in clinical microbiology laboratories. J Microbiol Methods 2015, 113, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D. L.; Griener, T.; Gregson, D. Multi-year comparison of VITEK(R) MS and BR 16S PCR rRNA gene sequencing performance for the identification of rarely encountered anaerobes causing invasive human infections in a large Canadian region: can our laboratory abandon BR 16S PCR rRNA gene sequencing? Anaerobe 2022, 78, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D. L.; Griener, T.; Gregson, D. Multi-year comparison of VITEK MS performance for identification of rarely encountered pathogenic Gram-negative organisms (GNOs) in a large integrated Canadian healthcare region. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0227624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Angrup, A.; Ghosh, A.; Singh, S.; Sood, A.; Arora, A.; Sharma, M.; Sethi, S.; Rudramurthy, S. M.; Kaur, H.; et al. Evaluation of VITEK MS Version 3.0 MALDI-TOF for the identification of anaerobes, mycobacteria, Nocardia, and moulds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2024, 110, 116477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Griener, T.; Gregson, D. Multi-year comparison of VITEK MS performance for identification of rarely encountered pathogenic gram-positive organisms (GPOs) in a large integrated Canadian healthcare region. Microbiol Spectr 2025, 13, e0254524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, W.; Campbell, L.; Pitout, J.; Conly, J.; Church, D.; Gregson, D. Comparison of Accelerate PhenoTest BC Kit and MALDI-TOF MS/VITEK 2 System for the rapid identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of gram-negative bacilli causing bloodstream infections. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can 2020, 5, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, K. K.; Olsen, R. J.; Musick, W. L.; Cernoch, P. L.; Davis, J. R.; Peterson, L. E.; Musser, J. M. Integrating rapid diagnostics and antimicrobial stewardship improves outcomes in patients with antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteremia. J Infect 2014, 69, 216–225. [CrossRef]

- Dalai, A. S.; Monti, E. B.; Mallesho, R.; Obeda, M.; Evans, G. A.; Perez-Patrigeon, S.; Wilson, E.; Martinez-Cajas, J. L.; Sheth, P. M.; Tomalty, L.; et al. Increasing evidence-based care practices for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia through required infectious diseases consultation in a tertiary care hospital: a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Open Qual 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, P. E.; Thuny, F.; Richet, H.; Lepidi, H.; Casalta, J. P.; Arzouni, J. P.; Maurin, M.; Celard, M.; Mainardi, J. L.; Caus, T.; et al. Comprehensive diagnostic strategy for blood culture-negative endocarditis: a prospective study of 819 new cases. Clin Infect Dis 2010, 51, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. J.; Chow, B.; Pillai, D.; Church, D. Development and evaluation of a novel fast broad-range BR 16S PCR ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing assay for diagnosis of bacterial infective endocarditis: multi-year experience in a large Canadian healthcare zone and a literature review. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller Premru, M.; Lejko Zupanc, T.; Klokocovnik, T.; Ruzic Sabljic, E.; Cerar, T. Broad-Range BR 16S PCR rDNA PCR on Heart Valves in Infective Endocarditis. J Heart Valve Dis 2016, 25, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, M. S.; Chang, J.; Kim, M. N.; Choi, S. H.; Jung, S. H.; Lee, J. W.; Sung, H. Utility of a Direct BR 16S PCR rDNA PCR and Sequencing for Etiological Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. Ann Lab Med 2017, 37, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.; Garcia-Lechuz, J. M.; Alonso, P.; Villanueva, M.; Alcala, L.; Gimeno, M.; Cercenado, E.; Sanchez-Somolinos, M.; Radice, C.; Bouza, E. Role of universal BR 16S PCR rRNA gene PCR and sequencing in diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Zhai, Z.; Wu, C.; Jin, F.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; et al. Preoperative aspiration culture for preoperative diagnosis of infection in total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Clin Microbiol 2013, 51, 3830–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, R.; Curtis, S.; Schilling, W. H.; James, P. R. Blood culture negative endocarditis in the modern era of BR 16S PCR rRNA sequencing. Clin Med (Lond) 2020, 20, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Liu, Y.; Ehnert, S.; Nussler, A. K.; Yu, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, T. The Effectiveness of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in the Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 875822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B.; Herijgers, P.; Beuselinck, K.; Verhaegen, J.; Peetermans, W. E.; Herregods, M. C.; Desmet, S.; Lagrou, K. Added diagnostic value and impact on antimicrobial therapy of BR 16S PCR rRNA PCR and amplicon sequencing on resected heart valves in infective endocarditis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017, 23, 888–e881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borde, J. P.; Hacker, G. A.; Guschl, S.; Serr, A.; Danner, T.; Hubner, J.; Burrack-Lange, S.; Ludke, G.; Helwig, P.; Hauschild, O.; et al. Diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections using UMD-Universal Kit and the automated multiplex-PCR Unyvero i60 ITI((R)) cartridge system: a pilot study. Infection 2015, 43, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.; Doern, C.; Jo, C. H.; Copley, L. A. The Clinical Usefulness of Polymerase Chain Reaction as a Supplemental Diagnostic Tool in the Evaluation and the Treatment of Children With Septic Arthritis. J Pediatr Orthop 2016, 36, 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Akram, A.; Maley, M.; Gosbell, I.; Nguyen, T.; Chavada, R. Utility of BR 16S PCR rRNA PCR performed on clinical specimens in patient management. Int J Infect Dis 2017, 57, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kommedal, O.; Simmon, K.; Karaca, D.; Langeland, N.; Wiker, H. G. Dual priming oligonucleotides for broad-range amplification of the bacterial BR 16S PCR rRNA gene directly from human clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, S.; Malhotra, R.; Sreenivas, V.; Kapil, A.; Chaudhry, R.; Dhawan, B. Utility of BR 16S PCR rRNA PCR in the Synovial Fluid for the Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection. Ann Lab Med 2018, 38, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuwer, A. Q.; van den Bijllaardt, W.; Murk, J. L.; Buiting, A. G. M.; Verweij, J. J. Added diagnostic value of broad-range BR 16S PCR on periprosthetic tissue and clinical specimens from other normally sterile body sites. J Appl Microbiol 2019, 126, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fida, M.; Khalil, S.; Abu Saleh, O.; Challener, D. W.; Sohail, M. R.; Yang, J. N.; Pritt, B. S.; Schuetz, A. N.; Patel, R. Diagnostic Value of BR 16S PCR Ribosomal RNA Gene Polymerase Chain Reaction/Sanger Sequencing in Clinical Practice. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, R.; Rodriguez-Esteban, M. A.; Fernandez-Suarez, J.; Morilla, A.; Garcia-Carus, E.; Telenti, M.; Morales, C.; Albaiceta, G. M.; Fernandez, J. Evaluation of BR 16S PCR rDNA Heart Tissue PCR as a Complement to Blood Cultures for the Routine Etiological Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Vazquez, V.; Dworakowski, R.; Cannata, A.; Amin-Youssef, G.; Gunning, M.; Papachristidis, A.; MacCarthy, P.; Baghai, M.; Deshpande, R.; Khan, H.; et al. BR 16S PCR rDNA PCR for the aetiological diagnosis of culture-negative infective endocarditis. Infection 2022, 50, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M. A.; Ganeshraj, N.; Gu, A.; Warren, D. K.; Burnham, C. D. Lack of Additional Diagnostic Yield of BR 16S PCR rRNA Gene PCR for Prosthetic Joint Infections. J Appl Lab Med 2019, 4, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavnsbjerg, C.; Frimodt-Moller, N.; Moser, C.; Bjarnsholt, T. Comparison of two commercial broad-range PCR and sequencing assays for identification of bacteria in culture-negative clinical samples. BMC Infect Dis 2017, 17, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkadlec, J.; Peckova, M.; Sramkova, L.; Rohn, V.; Jahoda, D.; Raszka, D.; Berousek, J.; Mosna, F.; Vymazal, T.; Kvapil, M.; et al. The use of broad-range bacterial PCR in the diagnosis of infectious diseases: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019, 25, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez-Mejia, E. P.; de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Escobar, J. S. Impact of DNA extraction, sample dilution, and reagent contamination on BR 16S PCR rRNA gene sequencing of human feces. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrhovden, R.; Rippin, M.; Ovrebo, K. K.; Nygaard, R. M.; Ulvestad, E.; Kommedal, O. Managing Contamination and Diverse Bacterial Loads in BR 16S PCR rRNA Deep Sequencing of Clinical Samples: Implications of the Law of Small Numbers. mBio 2021, 12, e0059821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, D.; Rajan, D.; Bellis, K. L.; Betteridge, E.; Brennan, J.; de Sousa, C.; Carriage Study, T.; Parkhill, J.; Peacock, S. J.; de Goffau, M. C.; et al. Optimization of high-throughput BR 16S PCR rRNA gene amplicon sequencing: an assessment of PCR pooling, mastermix use and contamination. Microb Genom 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Tan, T.L.; Goaswami, K.; Higuera, C.; Della Valle, C.; Chen, A.F.; Shohat, N. The 2018 defintion of periprstheitic hip and knee infection: an evidence-based and validated criteria. J Arthro, 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Boers, S. A.; Jansen, R.; Hays, J. P. Understanding and overcoming the pitfalls and biases of next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods for use in the routine clinical microbiological diagnostic laboratory. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 38, 1059–1070. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. X.; Huang, Z.; Fang, X.; Li, W.; Yang, B.; Zhang, W. Comparison of broad-range polymerase chain reaction and metagenomic next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 95, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, M.; Wolf, M. J.; Hamdi, A.; Vijayvargiya, P.; Esquer Garrigos, Z.; Khalil, S.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K. E.; Thoendel, M. J.; Patel, R. Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria From Septic Patients Using BR 16S PCR Ribosomal RNA Gene-Targeted Metagenomic Sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Satpathy, G.; Chawla, R.; Paliwal, D.; Panda, S. K. Targeted metagenomics using next generation sequencing in laboratory diagnosis of culture negative endophthalmitis. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06780. [CrossRef]

- Flurin, L.; Wolf, M. J.; Mutchler, M. M.; Daniels, M. L.; Wengenack, N. L.; Patel, R. Targeted Metagenomic Sequencing-based Approach Applied to 2146 Tissue and Body Fluid Samples in Routine Clinical Practice. Clin Infect Dis 2022, 75, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flurin, L.; Fisher, C. R.; Wolf, M. J.; Pritt, B. S.; DeSimone, D. C.; Patel, R. Comparison of Blood-Based Shotgun and Targeted Metagenomic Sequencing for Microbiological Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10, ofad546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flurin, L.; Wolf, M. J.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K. E.; Sanchez-Sotelo, J.; Patel, R. Targeted next generation sequencing for elbow periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2021, 101, 115448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. L.; Flurin, L.; Thoendel, M. J.; Wolf, M. J.; Abdel, M. P.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K. E.; Patel, R. Targeted Versus Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing-based Detection of Microorganisms in Sonicate Fluid for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, e1456–e1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, S.; Dong, G.; Niu, Y. Diagnostic Performance of Metagenomic Next rectangleGeneration Sequencing in the Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection Using Tissue Specimens. Infect Drug Resist 2023, 16, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahnic, A.; Rak, M.; Trebse, R.; Rupnik, M.; Cor, A. Identification of prosthetic joint infections with BR 16S PCR amplicon metagenomic sequencing - comparison with standard cultivation approach. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2024, 109, 116188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Characteristic | N (%) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 662 | |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 41.8 ± 7.7 | |

| Adults (≥14 yrs) | 532 (80.4); 56.95 ± 10.8 |

|

| Male; Age, years (mean ± 2SD) | 300 (56.4); 56.5 ± 6.6 | |

| Female; Age, years (mean ± 2SD) | 232 (43.6); 57.6 ± 4.5 | |

| Pediatrics (≤14 yrs) | 130 (19.6); 6.3 ± 9.6 | |

| Male; Age, years (mean ± 2SD) | 78 (60.0); 6.7 ± 7.4 |

|

| Female; Age, years (mean ± 2SD) | 52 (40.0); 6.6 ± 9.9 | |

| Location | Hospitalized or ED | 589 (89) |

| Ambulatory | 33 (11) | |

| Prior antibiotic therapy | 652(98.6) | |

| Therapy prior to specimen collection | 9 d ± 6.4 d |

| Original Culture Result | BR 16S PCR Negative | BR 16S PCR Indeterminate | BR 16S PCR Positive | BR 16S PCR Positive – Same Organism as Culture | BR 16S PCR Positive – Different Organism as Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (96%) | 22 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Possible Pathogen | 3 (23%) | 1 (8%) | 9 (69%) | 5 (56%) | 4 (44%)a |

| Likely Contaminant | 14 (67%) | 1 | 6 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%)b |

| Negative | 429 (61%) | 29 (4%) | 245 (35%) | NA | NA |

| Other Relevant Culture Result | BR 16S PCR Negative | BR 16S PCR Indeterminate | BR 16S PCR Positive | BR 16S PCR Positive – Same Organism as Culture | BR 16S PCR Positive – Different Organism as Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | 11 (24%) | 0 (%) | 35 (76%) | 34 (97%) | 1 (3%)a |

| Possible Pathogen | 19 (56%) | 1 (3%) | 15 (44%) | 8 (53%) | 7 (47%)b |

| Likely Contaminant | 38 (75%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (25%) | 1 (8%) | 12 (92%)c |

| Negative | 375 (63%) | 216 (37%) | 29 (5%) | NA | NA |

| Bone and Joint Specimens (N=309) |

Gram PMN (N=309, 23.0%) |

Gram Organism (N=309, 23.0%) |

WBC >9.0 X 109/L (N=274, 23.7%) |

Neutrophils HIGH (N=166, 28.9%) |

CRP>50 mg/L (N=249, 25.3%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TRUE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR positive) |

55 | 5 | 42 | 12 | 38 |

|

FALSE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR negative) |

128 | 13 | 131 | 45 | 103 |

|

FALSE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts Negative/BR 16S PCR positive) |

16 | 66 | 23 | 36 | 25 |

|

TRUE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts negative/BR 16S PCR negative) |

110 | 225 | 78 | 73 | 83 |

| BR 16S PCR Assay Performance | |||||

| Sensitivity (correct prediction of positive) | 77.5% (95% CI 66.0% - 86.5%) |

7.0% (95% CI:2.3% - 15.7%) |

64.6% (95% CI:51.8% - 76.1%) |

25.0% (95% CI:13.6\% - 39.6%) |

60.3% (95% CI:47.2% - 72.4%) |

| Specificity (correct prediction of negative) | 46.2% (95% CI:39.8% - 52.8%) |

94.5% (95% CI:90.8% - 97.1%) |

37.3% (95% CI:30.8% - 44.4%) |

61.9% (95% CI:52.5 - 70.65%) |

45.0% (95% CI:37.4% - 52.1%) |

| Positive Predictive Value | 30.1% (95% CI:26.6% - 33.8%) |

27.8% (95% CI:12.4% - 51.0%) |

24.3% (95% CI:20.7% - 28.3%) |

21.1% (95% CI:13.4% -31.4%) |

27.0% (95% CI:22.5% -31.9%) |

| Negative Predictive Value | 87.3% (95% CI:81.4% - 91.5%) |

77.3% (95% CI:76.1% - 78.5%) |

77.2% (95% CI:70.0% - 83.1%) |

67.0% (95% CI:62.0% _ 71.6%) |

76.9% (95% CI:70.2% - 82.4%) |

| Accuracy | 53.4% (95% CI:47.7% - 59.1%) |

74.4% (95% CI 69.1% - 79.2%) |

43.0% (95% CI:37.8% - 49.9%) |

51.2% (95% CI: 43.3% - 59.0%) |

48.6% (95% CI:42.2% - 55.0%) |

| Odds Ratio | 2.95 | 1.31 | 1.09 | 0.54 | 1.22 |

| Relative Risk | 2.37 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 0.64 | 1.16 |

| Bone and Joint Specimens (N=309) |

Gram PMN (N=309, 23.0%) |

Gram Organism (N=309, 23.0%) |

WBC >9.0 X 109/L (N=274, 23.7%) |

Neutrophils HIGH (N=166, 28.9%) |

CRP>50 mg/L (N=249, 25.3%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TRUE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR positive) |

55 | 5 | 42 | 12 | 38 |

|

FALSE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR negative) |

128 | 13 | 131 | 45 | 103 |

|

FALSE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts Negative/BR 16S PCR positive) |

16 | 66 | 23 | 36 | 25 |

|

TRUE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts negative/BR 16S PCR negative) |

110 | 225 | 78 | 73 | 83 |

| BR 16S PCR Assay Performance | |||||

| Sensitivity (correct prediction of positive) | 77.5% (95% CI 66.0% - 86.5%) |

7.0% (95% CI:2.3% - 15.7%) |

64.6% (95% CI:51.8% - 76.1%) |

25.0% (95% CI:13.6\% - 39.6%) |

60.3% (95% CI:47.2% - 72.4%) |

| Specificity (correct prediction of negative) | 46.2% (95% CI:39.8% - 52.8%) |

94.5% (95% CI:90.8% - 97.1%) |

37.3% (95% CI:30.8% - 44.4%) |

61.9% (95% CI:52.5 - 70.65%) |

45.0% (95% CI:37.4% - 52.1%) |

| Positive Predictive Value | 30.1% (95% CI:26.6% - 33.8%) |

27.8% (95% CI:12.4% - 51.0%) |

24.3% (95% CI:20.7% - 28.3%) |

21.1% (95% CI:13.4% -31.4%) |

27.0% (95% CI:22.5% -31.9%) |

| Negative Predictive Value | 87.3% (95% CI:81.4% - 91.5%) |

77.3% (95% CI:76.1% - 78.5%) |

77.2% (95% CI:70.0% - 83.1%) |

67.0% (95% CI:62.0% _ 71.6%) |

76.9% (95% CI:70.2% - 82.4%) |

| Accuracy | 53.4% (95% CI:47.7% - 59.1%) |

74.4% (95% CI 69.1% - 79.2%) |

43.0% (95% CI:37.8% - 49.9%) |

51.2% (95% CI: 43.3% - 59.0%) |

48.6% (95% CI:42.2% - 55.0%) |

| Odds Ratio | 2.95 | 1.31 | 1.09 | 0.54 | 1.22 |

| Relative Risk | 2.37 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 0.64 | 1.16 |

|

CVR Specimens (N=158) |

Gram PMN (N=158, 55.7%) |

Gram Organism (N=158, 55.7%) |

WBC >9.0 X 109/L (N=148, 56.1%) |

Neutrophils HIGH (N=59, 54.2%) |

CRP >50 mg/L (N=47, 68.1%) |

|

TRUE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR positive) |

42 | 20 | 82 | 26 | 26 |

|

FALSE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR negative) |

15 | 2 | 58 | 13 | 8 |

|

FALSE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts Negative/BR 16S PCR positive) |

46 | 68 | 1 | 6 | 6 |

|

TRUE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts negative/BR 16S PCR negative) |

55 | 68 | 5 | 14 | 7 |

| BR 16S PCR Assay Performance | |||||

|

Sensitivity (correct prediction of positive) |

47.7% (95% CI:37.0% - 58.7%) |

22.7% (95% CI:14.5% - 32.9%) |

98.8% (95% CI:93.5% - 99.9%) |

81.3% (95% CI:63.6% - 92.8%) |

81.3% (95% CI:63.6% - 92.8%) |

|

Specificity (correct prediction of negative) |

78.6% (95% CI:67.1% - 87.5%) |

97.1% (95% CI:90.1% - 99.7%) |

7.9% (95% CI:2.6% - 17.6%) |

51.9% (95% CI:32.9% - 71.3%) |

46.7% (95% CI:21.3% - 73.4%) |

| Positive Predictive Value | 73.7% (95% CI:63.0% - 82.2%) |

90.9% (95% CI:70.8% - 97.6%) |

58.6% (95% CI:56.7% - 60.4%) |

66.7% (95% CI:56.6% - 75.4%) |

76.5% (95% CI:66.3% - 84.3%) |

| Negative Predictive Value | 54.5% (95% CI:48.6% - 60.2%) |

50.0% (95% CI:47.0% - 53.0%) |

83.3% (95% CI:37.5% - 97.7%) |

70.0% (95% CI:60.0% - 84.0%)% |

53.9% (95% CI:32,1% - 74.2%) |

| Accuracy | 61.4% (95% CI:53.3% - 69.0%) |

55.7% (95% CI:47.6% - 63.6%) |

59.6% (95% CI:51.2% - 67.6%) |

67.8% (95% CI:54.4% - 79.4%) |

70.2% (95% CI:55.1% - 82.7%) |

| CSF Specimens (n=101) | Gram PMN (N=101, 24.8%) |

Gram Organism (N=101, 24.8%) |

WBC >9.0 X 109/L (N=95, 24.2%) |

Neutrophils HIGH (N=69, 21.7%) |

CRP >50 mg/L (N=66, 22.7%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TRUE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR positive) |

24 | 14 | 22 | 11 | 11 |

|

FALSE POSITIVE (Parameter Predicts positive/BR 16S PCR negative) |

36 | 2 | 49 | 19 | 13 |

|

FALSE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts Negative/BR 16S PCR positive) |

1 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

|

TRUE NEGATIVE (Parameter Predicts negative/BR 16S PCR negative) |

40 | 74 | 23 | 35 | 38 |

| BR 16S PCR Assay Performance | |||||

| Sensitivity (correct prediction of positive) | 96% (95% CI: 79.7% - 99.9%) |

56% (95% CI:34.9% - 75.6%) |

95.7% (95% CI: 78.1% - 99.9%) |

73.3% (95% CI:44.9% - 92.2%) |

73.3% (95% CI:44.9% - 92.2%) |

| Specificity (correct prediction of negative) | 52.6% (95% CI:40.8% - 64.2%) |

97.4% (95% CI: 90.8% - 99.7%) |

31.9% (95% CI: 21.4% - 44.0%) |

64.8% (95% CI:50.6% - 77.3%) |

74.5% (95% CI: 60.4% - 85.7%) |

| Positive Predictive Value | 40.0% (95% CI: 34.2% - 46.1%) |

87.5% (95% CI:63.1% - 96.6%) |

31.0% (95% CI:27.3% - 35.0%) |

36.7% (95% CI: 26.5% - 48.2%) |

45.8% (95% CI:32.6% - 59.7%) |

| Negative Predictive Value | 97.6% (95% CI:85.3% - 99.6%) |

87.1% (95% CI: 81.2% - 91.3%) |

95.8% (95% CI:76.7% - 99.4%) |

89.7% (95% CI:78.7% - 95.4%) |

90.5% (95% CI: 80.2% - 95.7%) |

| Accuracy | 63.4% (95% CI:53.2% - 72.7%) |

87.1% (95% CI:79.0% - 93.0%) |

47.4% (95% CI:37.0% - 57.9%) |

66.7% (95% CI: 54.3% - 77.6%) |

74.2% (95% CI:62.0% - 84.2%) |

| Odds Ratio | 26.67 | 47.09 | 10.33 | 5.07 | 8.04 |

| Relative Risk | 16.40 | 6.76 | 7.44 | 3.58 | 4.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).