Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pangenome Analysis

2.1. Primer and Probe Design

2.1. Validation of Primer Specificity Using Conventional PCR and SYBR Green qPCR

2.1. Preparation of Standard Plasmids

2.1. Optimization of Duplex Fluorescent Quantitative PCR Assay

2.1. Evaluation of Specificity, Repeatability, and Sensitivity

3. Results

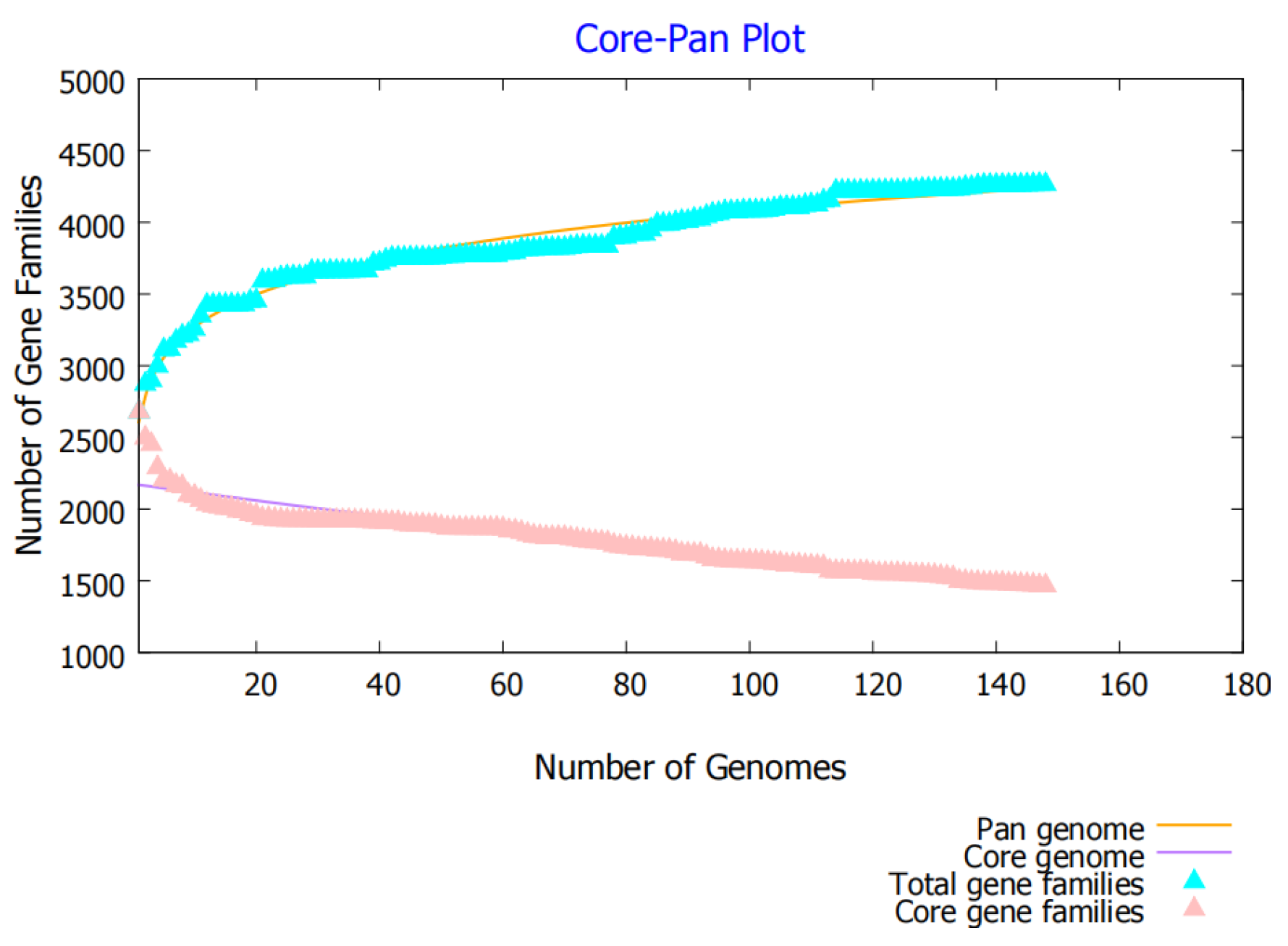

3.1. Pan-Genome Analysis

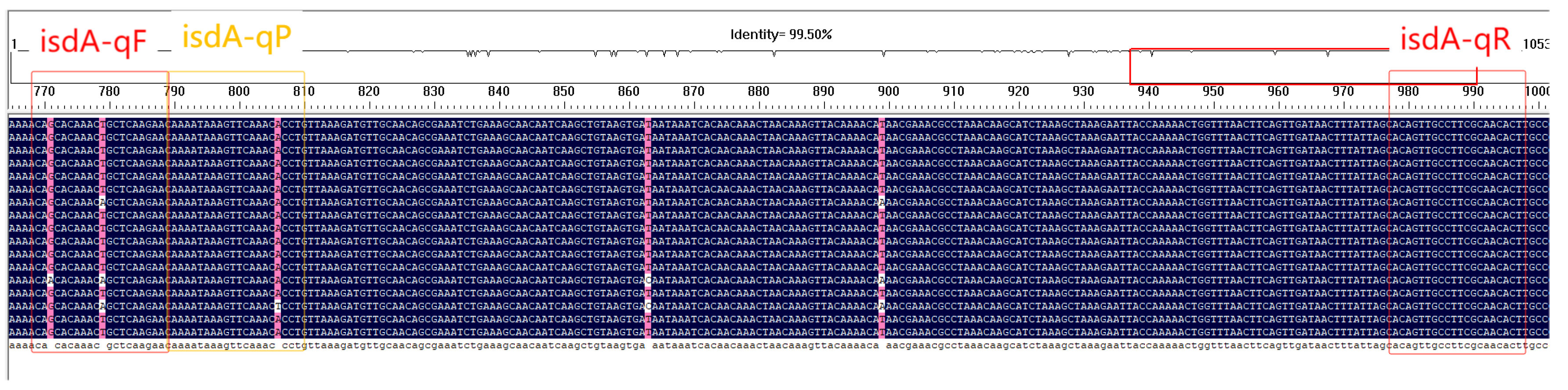

3.2. Primer and Probe Design Results

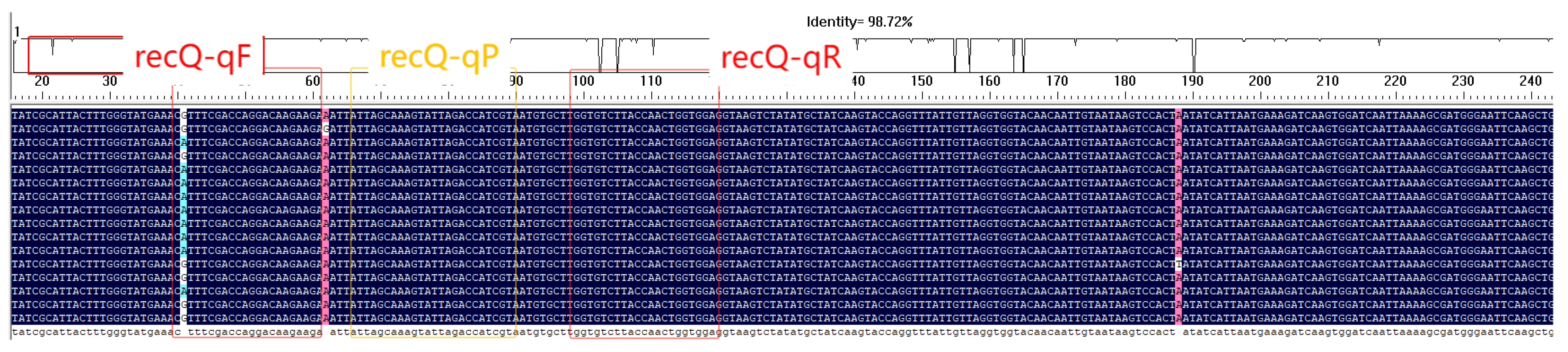

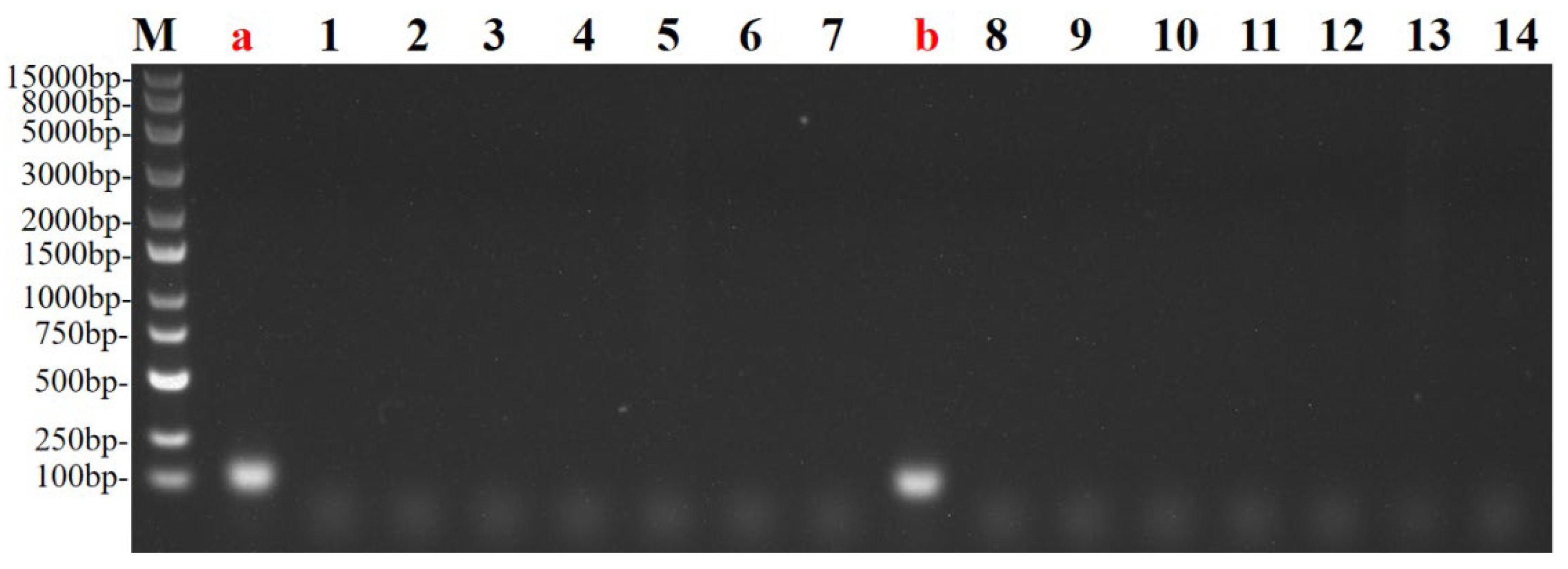

3.3. Specificity Validation of Primers by Conventional PCR and SYBR Green Assay

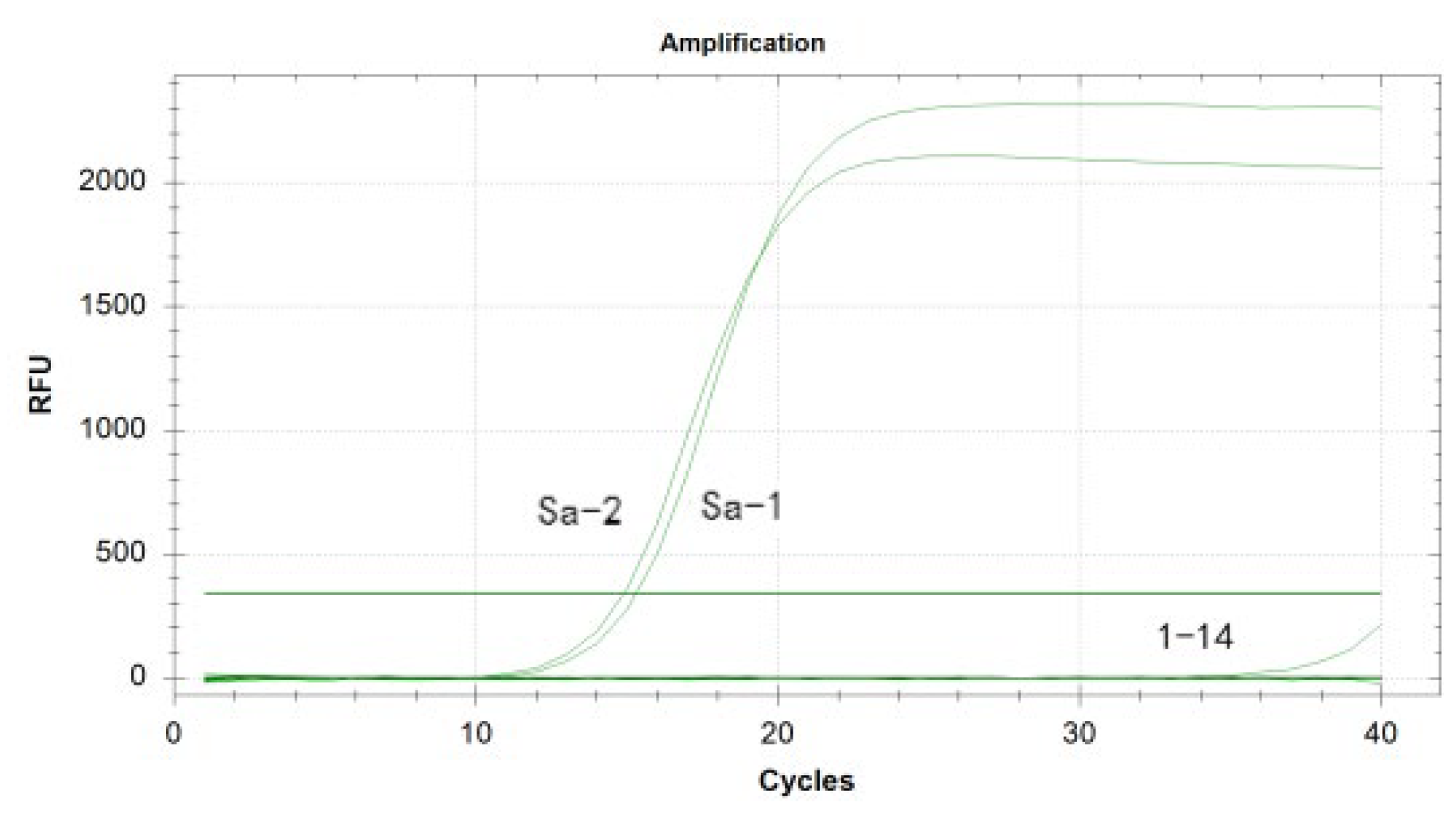

3.4. Optimization and Establishment of the Duplex Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR Method

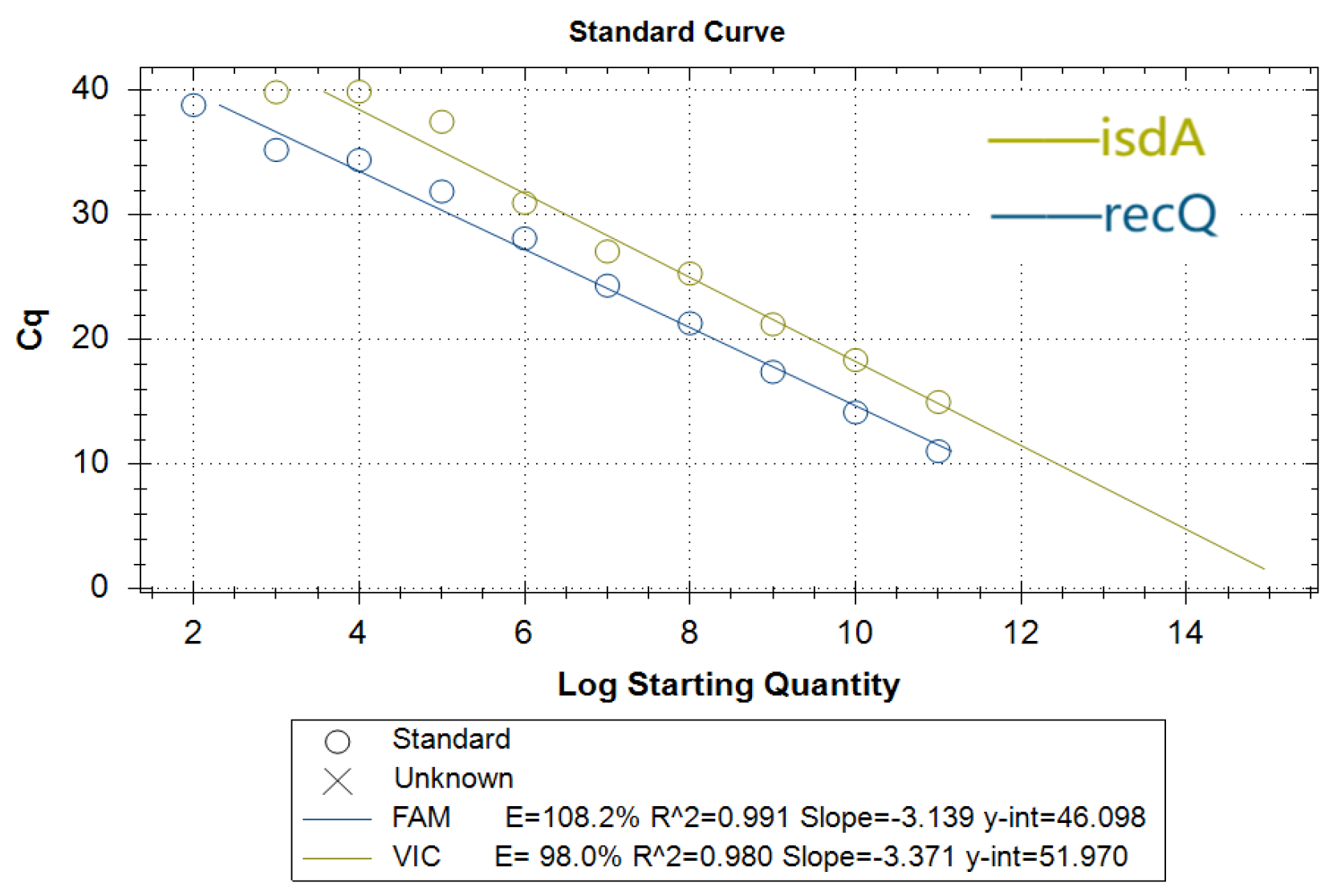

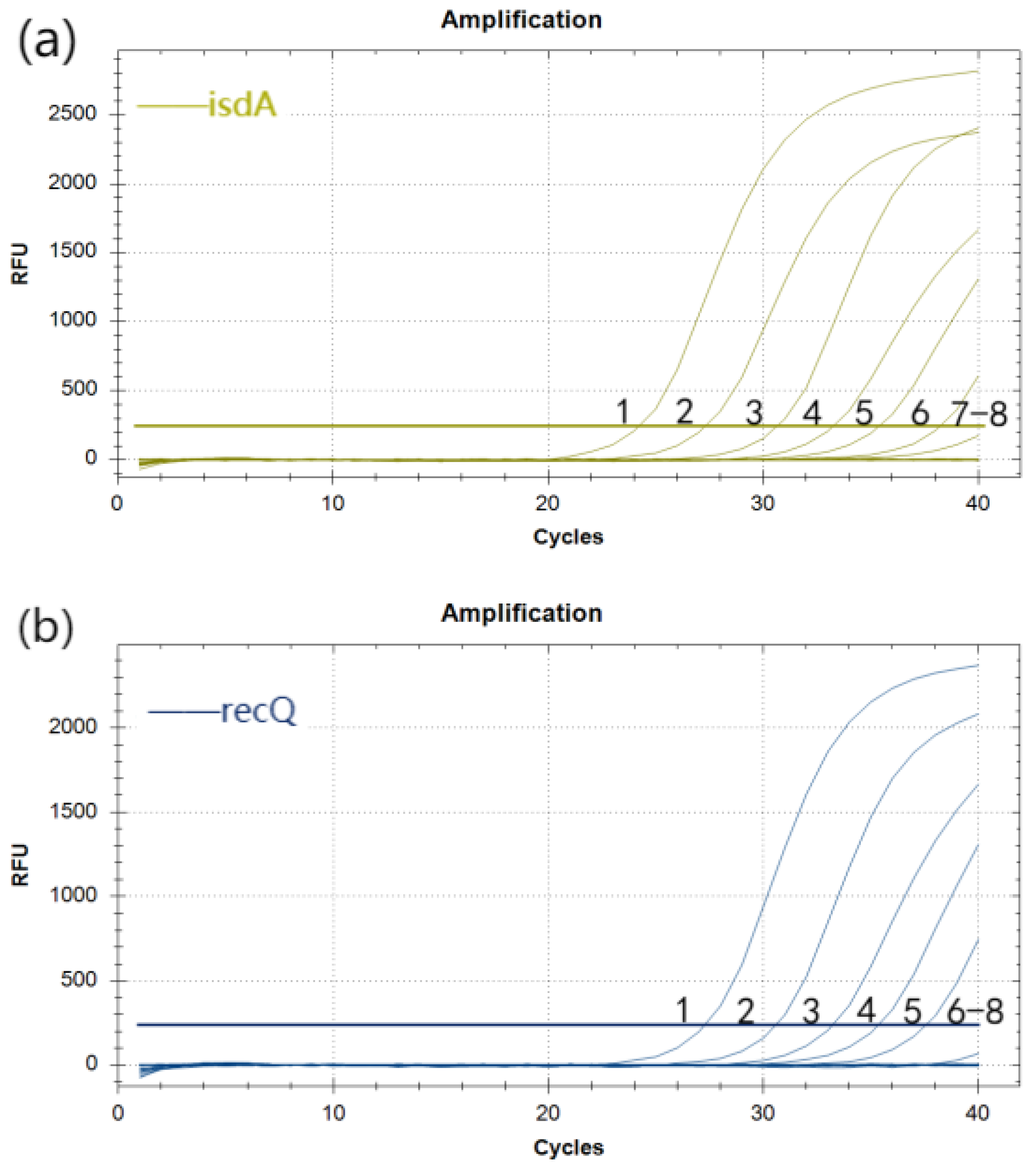

3.5. Standard Curves for Duplex Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR

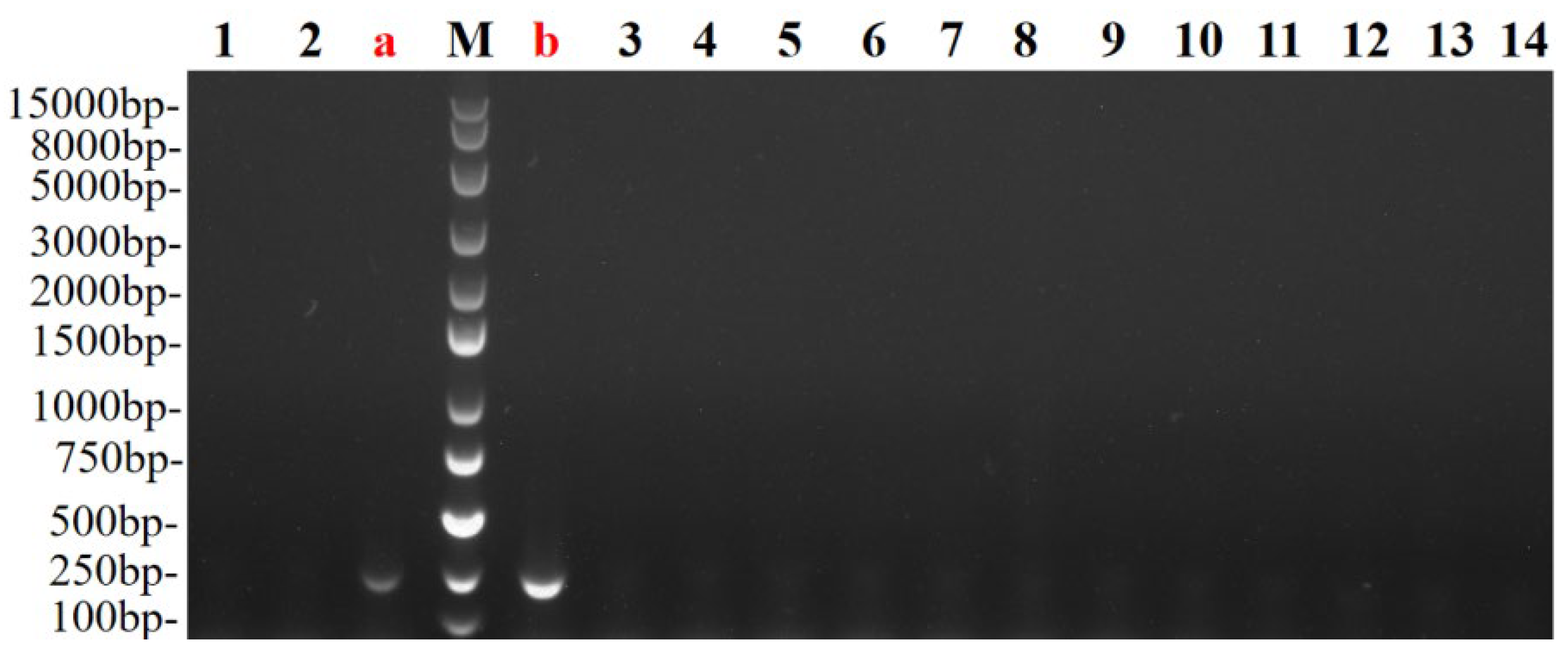

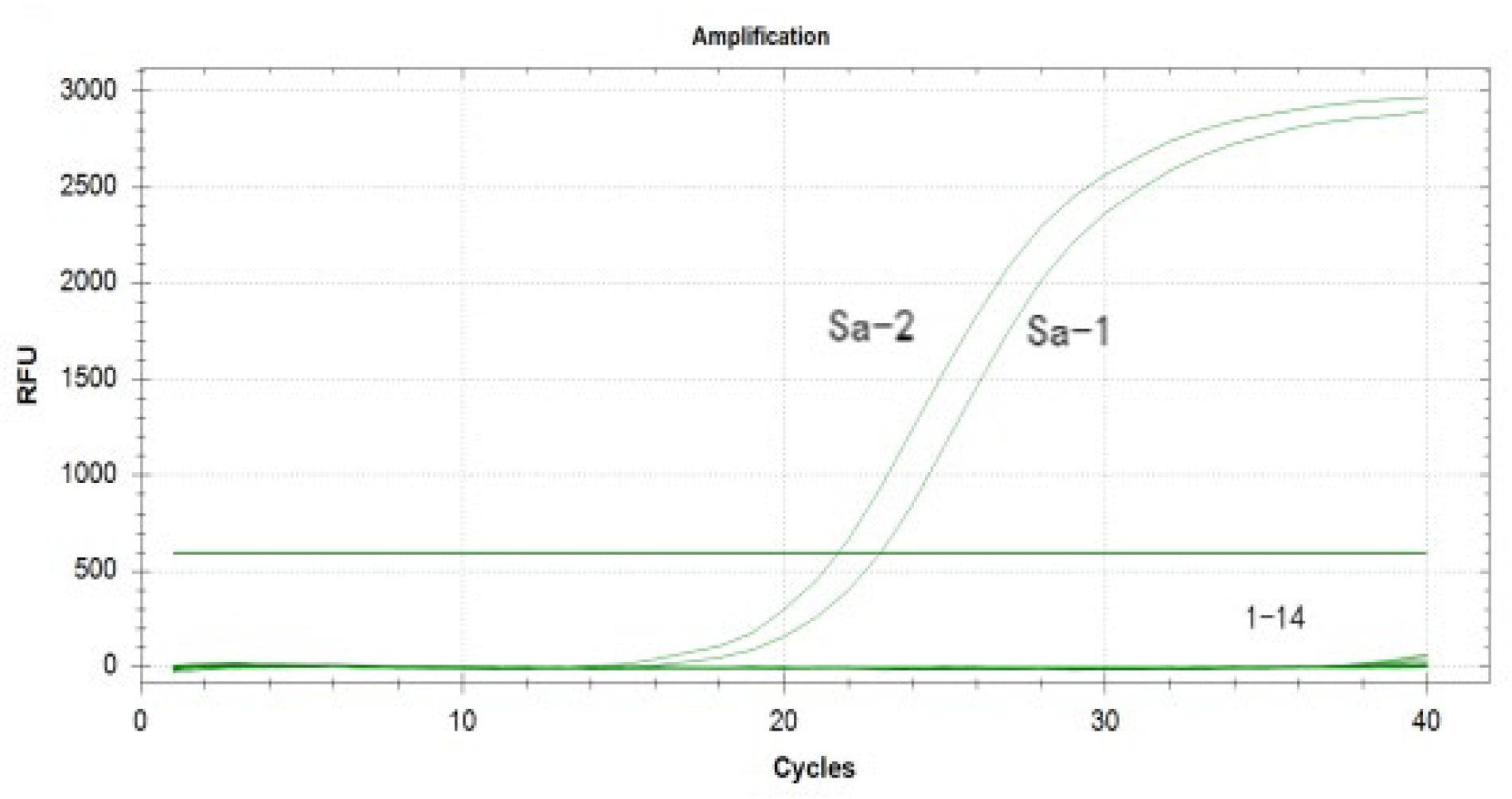

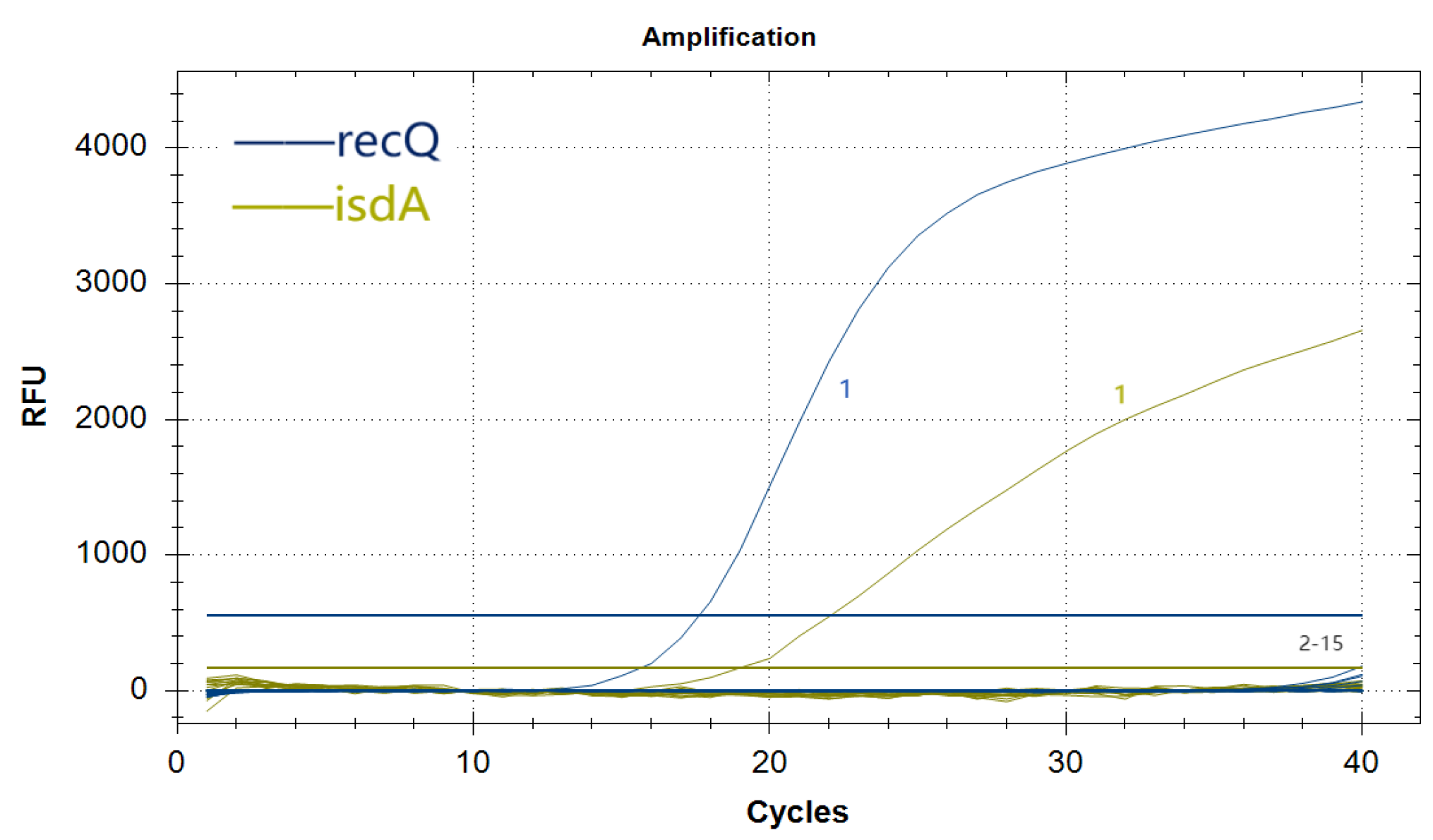

3.6. Specificity Analysis of the Duplex Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR Assay

3.7. Reproducibility Analysis of the Duplex Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR Assay

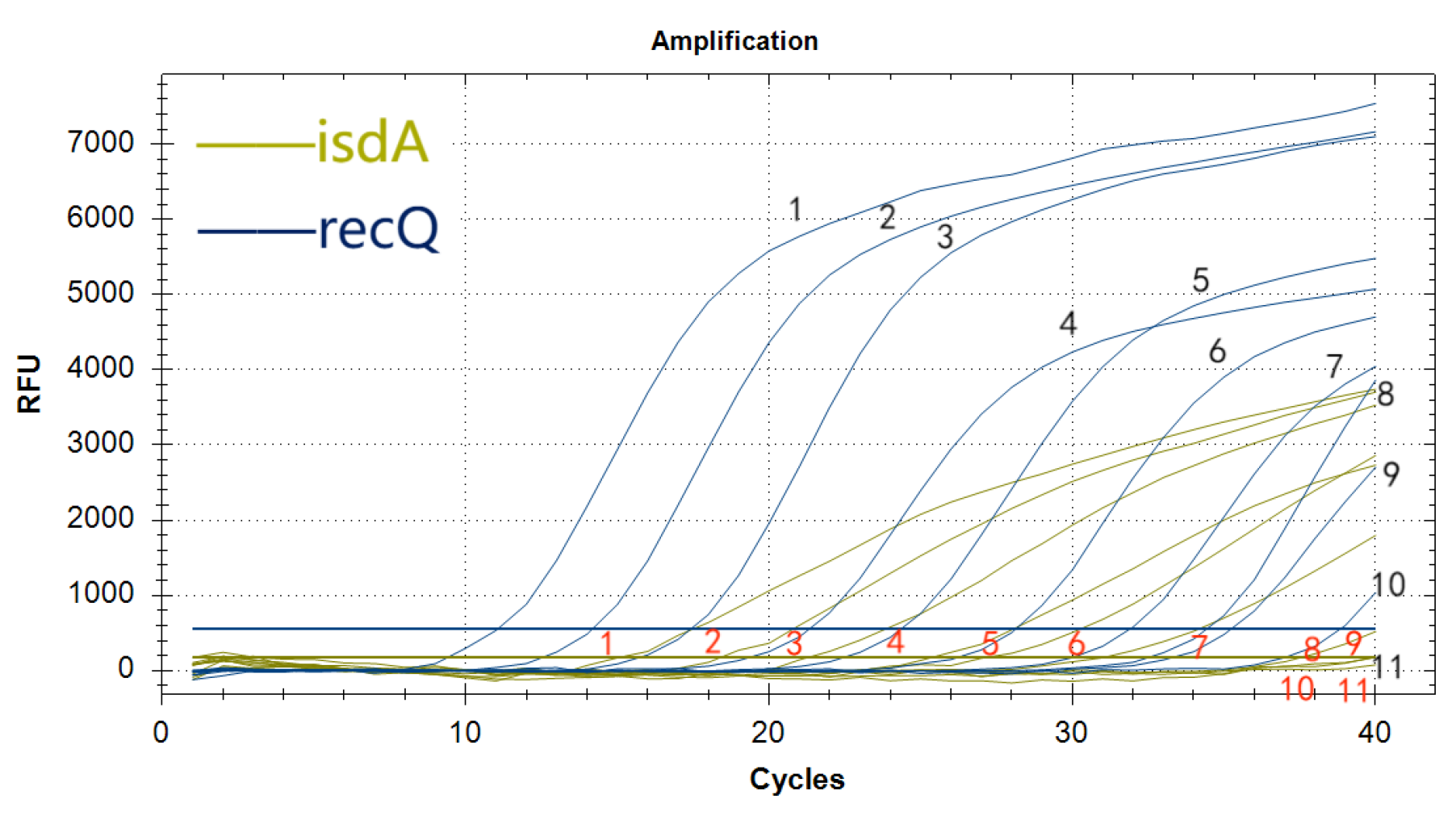

3.8. Sensitivity Analysis of the Duplex Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence. 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, H.; Sara, E.C.; Sarah, B.D.; et al. Ceftobiprole for Treatment of Complicated Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2023, 389, 1390–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiecinski, J.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: Pathogenesis and regulatory mechanisms. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020, 53, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Y.C.; Justin, S.B.; Michael, O. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence. 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, P.; Matthias, N.; José-Luiz, F.; et al. In vivo detection of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis by targeting pathogen-specific prothrombin activation. Nature Medicine. 2011, 17, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad-Mansour, N.; Loubet, P.; Pouget, C.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus Toxins: An Update on Their Pathogenic Properties and Potential Treatments. Toxins 2021, 13, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, B.A. Isolation and Identification of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus from animal and detection of their antibiotics susceptibility pattern. University of Thi-Qar Journal of Science. 2022, 9, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R.; Buckley, P.T.; O'Malley, A.; et al. Identification of biologic agents to neutralize the bicomponent leukocidins of Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Transl Med. 2019, 11, eaat0882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jari, J.H. The use of molecular methods for the detection and identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biomarkers in Medicine. 2014, 8, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Duplex MIRA-qPCR Assay for Simultaneous Detection of Staphylococcus aureus and non-aureus Staphylococci. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong-Min, K.; Hye-Ryung, K.; Gyu-Tae, J.; et al. Molecular Detection of Porcine Parainfluenza Viruses 1 and 5 Using a Newly Developed Duplex Real-Time RT-PCR in South Korea. Animals. 2023, 13, 598–598. [Google Scholar]

- Min, H.; Cai, H.; Sun, Y.; et al. Rapid and accurate detection for Staphylococcus aureus in drugs based on real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR. Natural Science Edition. 2024, 52, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Marjan, A. Proving similarity between MRJP1 and Yellow Protein with using blast and NCBI. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Technology and Innovation. 2021, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.W.; Nigel, G.H.; Liu, C.H. Real-Time Quantitative PCR: Primer Design, Reference Gene Selection, Calculations and Statistics. Metabolites. 2023, 13, 806–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Zhao, F.; Yu, X.L.; et al. Establishment of SYBR Green I real-time qPCR for the detection of bovine parvovirus. Chinese Veterinary Science. 2019, 49, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Joohwan, K.; Jin, H.K.; Pengbin, W.; et al. An Improved Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assay for the Enumeration of Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) Cysts Using a DNA Debris Removal Method and a Cyst-Based Standard Curve. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0145712–e0145712. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.Y.; Han, B.; Tong, Q.; et al. Detection of Eight Respiratory Bacterial Pathogens Based on Multiplex Real-Time PCR with Fluorescence Melting Curve Analysis. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology. 2020, 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Erin, D.M.; Colleen, W.; Laura, T.; et al. Screening for Babesia microtiin the U. S. Blood Supply. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016, 375, 2236–2245. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qin, H.; et al. Establishment of a quantitative RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Eur J Med Res. 2021, 26, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, R.Z.; et al. Prediction and identification of linear B cell epitopes of Staphylococcus aureus IsdA protein. Chinese Journal of Pathogenic Biology, 2016, 11, 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Lei. Study on the enzymatic properties and structure of RecQ helicase WRN and RecQ1 [D]. Northwest A&F University, 2020.

- Ding, P.; Gao, Y.; Tan, X.L.; et al. Bioinformatics and Transcriptomic Expression Analysis of the BnaC. RECQ4B Gene in Brassica napus. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences, 2023, 51, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.J.; Alex, N.; Debadyuti, G. Quantification of M13 and T7 bacteriophages by TaqMan and SYBR green qPCR. Journal of Virological Methods. 2018, 252, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.X.; Chen, Z.H.; Jiang, Q.F.; et al. A multiplex real-time fluorescence-based quantitative PCR assay for calf diarrhea viruses. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2024, 14, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.H.; Ao, L.J.; Luo, Y.X.; et al. Quantum dots assembly enhanced and dual-antigen sandwich structured lateral flow immunoassay of SARS-CoV-2 antibody with simultaneously high sensitivity and specificity. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2022, 198, 113810–113810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.Q. The Application Effect of Real-time Fluorescent Quantitative PCR in the Detection of Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. Medical Equipment. 2024, 37, 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.X.; Xu, Y.M.; Zhou, Y.X.; et al. Establishment and Validation of Multiplex Fluorescence Quantitative PCR Detection Methods for Bacteria and Fungi in Cell Culture Media. Chinese Journal of Biological Products. 2024, 37, 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.S.; et al. Establishment and Application of Multiplex PCR Detection Methods for Five Pathogenic Bacteria of Mastitis in Cattle. Advances in Animal Medicine. 2025, 46, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.X.; Zheng, R.J.; Ding, Y.F.; et al. Dual phage amplification-mediated multiplex detection strategies for the simultaneous detection of Salmonella enterica and Staphylococcus aureus. Talanta. 2023, 253, 124095–124095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, R.; Sheng, S.; et al. MOF nanozyme mediated bacterial metabolic regulation to intervene MRSA antibiotic tolerance for enhanced antimicrobial efficacy. Nano Today. 2025, 63102753–102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, F.; Ariyanti, T.; Noor, S.; et al. Exploring nuc A and mecA genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dairy cow milk through molecular characterization. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2025, 1471, 012061–012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, C.; Wu, Y.J.K.; Myers, G.A.; et al. Synthetic lincosamides iboxamycin and cresomycin are active against ocular multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant S. aureus carrying erm genes. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance 2024, 39144–39148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fungus name | isdAgene | recQgene | ||

| highest score | similarity% | highest score | similarity% | |

| S. aureus | 1945 | 93~100 | 948 | 95~100 |

| P. aeruginosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| K. pneumoniae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A. baumannii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P. mirabilis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| K. oxytoca | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. catarrhalis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L. pneumophila | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H. influenzae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N. meningitidis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C. freundii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. pneumoniae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. pneumonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. pyogenes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. salivarius | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Target gene | Primers/probes | sequences(5’→3’) | Fragment size(bp) |

| isdA | isdA-qF | ACAGCACAAACTGCTCAAGA | 229bp |

| isdA-qR | GTGTTGCGAAGGCAACTGTG | ||

| isdA-qP | VIC-CAAAATAAAGTTCAAACACC-BHQ1 | ||

| recQ | recQ-qF | ACGTTTCGACCAGGACAAGAA | 80bp |

| recQ-qR | CCACCAGTTGGTAAGACACCA | ||

| recQ-qP | 6-FAM-ATTAGCAAAGTATTAGACCATCG-BHQ1 |

| Yang plasmid copy number/ (copies/μL) |

Intra-assay Ct values | Inter-assay Ct values | |||||

| average value | standard deviation | coefficient of variation/% | average value | standard deviation | coefficient of variation/% | ||

| isdA | 1.335×108 | 24.55 | 0.325 | 1.32 | 24.62 | 0.330 | 1.34 |

| 1.335×109 | 20.71 | 0.386 | 1.86 | 20.64 | 0.592 | 2.87 | |

| 1.335×1010 | 17.36 | 0.162 | 0.93 | 17.45 | 0.421 | 2.42 | |

| recQ | 7.265×108 | 22.21 | 0.072 | 0.32 | 22.24 | 0.078 | 0.35 |

| 7.265×109 | 18.62 | 0.232 | 1.24 | 18.66 | 0.290 | 1.55 | |

| 7.265×1010 | 15.08 | 0.220 | 1.46 | 15.10 | 0.428 | 2.83 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).