Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- Multi-level governance and fiscal devolution. In June 2014, the African Union declared the Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralisation, Local Governance and Local Development, a charter that entered into force in January 2019. Orderly and predictable budget transfers and the devolution of specific fiscal and administrative responsibilities to local government enable the effective supply of infrastructure and services, but are not possible where local authorities lack institutional capacity, are highly contested or are not trusted by national governments (Cartwright et al., 2018; Lameck et al., 2019). More recent policy literature has emphasised the fiscal mechanisms that would allow larger and more mature cities to increase their dependence on “own revenue”, most obviously land tax (Amani et al., 2019; African Union, 2024; Haas et al., 2024) and the co-ordination of respective state agencies at the urban scale (Lameck, 2023).

- Industrialisation. Industrial strategy remains the flagship policy in most African countries (ECA/AfDB, 2022). History suggests that the concentration of infrastructure, capital, entrepreneurship, labour and technology in urban spaces in Africa, should be conducive to industrial progress (Henderson, 2005; Goodfellow and Huang, 2022; Kyule and Wang, 2024) and that rapidly growing cities provide markets for industrial sector outputs (Cloete et al., 2019). Despite this, most African cities operate as places of commodity extraction and not diverse manufacturing or industrial hubs, a design relic of structural adjustment programmes (Mkandewire and Soludo, 1999; Lopes et al., 2016; Pieterse, 2023). Changing this by linking industrialisation and urbanisation is complicated by China’s emergence as a global manufacturing superpower at the same time as Africa has been urbanising, but holds the key to drawing benefits from urbanisation (Goodfellow and Huang, 2022).

- Informality. That “informal” work is the predominant form of economic activity in many African cities is well documented (Jaglin, 2014; Parnell and Pieterse, 2014; Brown and McGranahan, 2016). However, data on African economies tend to under-report informal economic activity and service delivery and conflate “informality”, the “hustle” and “makeshift” economic activities (Thieme, 2018). The same is true for informal shelter provision and slums that arise when urbanisation rates outpace the ability of governments to provide serviced land and housing (Morrison, 2017). More generally, there is a seeming lack of government capacity to engage the lived-reality of informal settlements or to discern those aspects of the informal economy and shelter provision that are innovative and worthy of replication.

3. Landscape Analysis: Urbanisation and Urban Policy in Tanzania, Kenya Ethiopia

| Independ. year | Pop. (2023) million |

Urban % (2023) | Urbanstn. rate % (2024) | Life expectancy at birth | % pop living in informal settlement (2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanzania | 1961 | 67.5 | 31 - 37 | 6.2 | 67 | 41 |

| Kenya | 1963 | 55.1 | 30 | 4.2 | 62 | 51 |

| Ethiopia | 1947 | 126.5 | 22.5 | 4.8 | 66 | 64 |

| GDP billions (PPP) 2024 | GDP billns nominal (2024) | GDP growth rate 2024 | GDP/ capita (nominal) 2024 |

Dominant economic sector | Poverty headcount ($2.15 PPP) 2015 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanzania | 270 | 116 | 5.5% | 413,000 | Services | 44.9 |

| Kenya | 375 | 80 | 5% | 716,000 | Services | 36.1 |

| Ethiopia | 434 | 145 | 6.2% | 405,000 | Agriculture | 27.0 |

3.1. Tanzania

3.2. Ethiopia

3.3. Kenya

| Mult-level governance | Urban-industrial-climate | Informality and innovation | |

| Tanzania | Progress through policies that enable LGAs to raise their own revenue, but stalled National Urban Policy and continued centralization of revenue and budget allocation and large infrastructure projects. | Shift away from export oriented SEZs for everything but oil and gas in favour of “urban industrial hubs” for manufacturing. University and think tank involvement in evidence formulation. | Growing recognition of informality in state-sanctioned NGO activity. Emerging ability of the state to engage informal water provision in Arusha and involve informal communities in enumeration. |

| Ethiopia | Long-standing commitment to federalism and cities, but little capacity to resolve land conflicts generated by expanding cities with anything other than top-down decrees. National focus on Addis Ababa has challenged devolution. Centralised investment in infrastructure has been impressive but generated land conflicts. Hosting of the AU’s inaugural Africa Urban Forum in 2024. | Commitment to modernization of Addis Ababa and Industrial Parks for manufacturing and work creation, but declining manufacturing and no alignment of urban needs with industrial output. Low levels of university and think tank involvement in evidence formulation. | State efforts to upgrade and remove urban informality rather than collaborate with informal service providers. Limited capacity to integrate formal and customary tenure regimes in expanding cites. |

| Kenya | Effective MLG since 2010 with ongoing efforts to strengthen local revenue generation and accountable transfers of national budgets. | Declining manufacturing and continued industrial focus on exports as opposed to cities. University and think tank involvement in evidence formulation. | Longstanding NGO engagement with urban informality but difficult to insert qualitative data into urban planning. Focus on tenure upgrades in informal settlements and extensive NGO support for informal dwellers. |

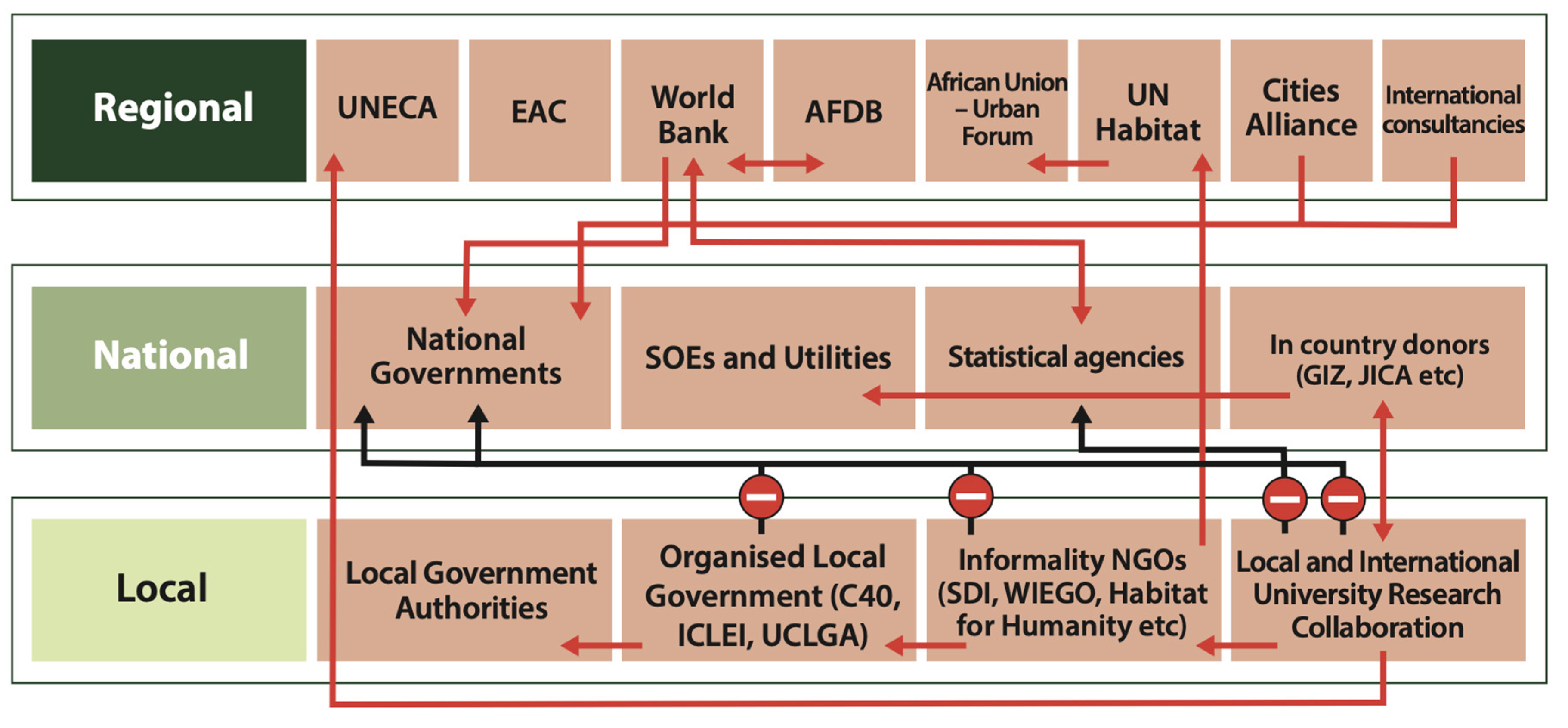

3.4. Urban Policy Evidence Actors in East Africa

- Regional actors

- National actors

- Local actors

4. Results and Discussion: Tracing Flows of Thematic Information

4.1. Multi-Level Governance and Fiscal Devolution

4.2. Industrial Strategy

4.3. Informality

5. Conclusion

- New platforms that transcend governance divides and integrate evidence from a variety of sources in order to create richer narratives around Africa’s urban spaces. Platforms that allow in-country academics, NGOs, local authority leaders and national government officials to interact and exchange ideas would elicit new types of evidence to inform the allocation of public and private investment. Similarly, two-way flows of evidence between local and national government would address the biases introduced by top-down and oxymoronic National Urban Policies in their current format (Bekker et al., 2021). The experiences of the TULab, a multi-level interdisciplinary platform for urban policy have been described for Tanzania (Cartwright, 2024), but there is a growing awareness of the need not just for the date required by EIP, but a deliberate process to ensure a diversity of evidence and the institutional capacity to assimilate this evidence. The African Mayoral Leadership Initiative (AMALI) links city political leads with each other and with academic evidence in pursuit of more sustainable urban development (ACC, 2025); the Association of African Planning Schools set out to disseminate academic evidence across urban practitioners in ways that overcame the academy-bureaucracy; citizen science holds untapped potential to enrich urban policy and ensure more effective allocations of resources; the work of the Rift Valley Institute in bringing “local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development” in East and Central Africa (RFI, 2025); the Africa Evidence Summit, co-hosted by Network of Impact Evaluation Researchers in Africa (NIERA) and the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA will hold its 13th gathering in Nairobi in 2025 focused on “better data for decision making” all speak to this need. Collectively, they could shore-up the frailties of Agenda 2063’s Africa Economic Platform aimed at bringing national leaders, academics, business people and youth entrepreneurs together, a platform that has convened just once since inception in 2016 (Nepad, 2025).

- Urban policy advisors could be in situ to the urban spaces they aim to improve, to enable links between top down quantitative evidence and bottom up qualitative evidence. In Tanzania, specifically, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation has chosen to work “in cities” rather than “on cities” as a means of gathering new data and enhancing the efficacy of their programmes in an innovation that holds potential for new evidentiary flows (Steinlin, 2022).

- Regional actors could draw on evidence from a greater variety of sources and from the local scale. Regional actors such as the World Bank, AfDB, the African Union and Cities Alliance have tended to engage national governments exclusively. In the process they have missed important evidence from the constituencies they purport to serve with their urban interventions. The exception to this is UN-Habitat that, through its local affiliates, has retained access to local evidence and which plays an important role in linking the evidence from a variety of sources and scales. The collaboration between UN-Habitat and Shelter Afrique and UNWomen, for example, has begun addressing the investment biases that emerge from existing configurations of evidentiary flows. UN-Habitat is unusual in UN family in that it has a regional and global mandate but is grounded by its local affiliates. It has been successful in bringing the experiences of informality into regional discourses but continues to struggle to insert its evidence and propositions into local and national government planning.

- Regional actors headquartered on the continent could counter the national bias against local governance and urban development by developing their own evidence, drawing on a wider variety of evidence providers and showcasing the existing evidence required to support urbanisation. The outgoing president of the African Development Bank has committed to increasing the money the Bank spends in cities and towns (Adesina, 2024). However, the evidence base through which to do this could be enhanced (Haas et al., 2024). This is required if regional value chains are to be harnessed to provide the goods and services that rapidly growing urban centres will demand, and if the previously distinct priorities of climate change, industrialization and urbanization are to be integrated. The Economic Communities under the African Continental Free Trade Area have a particularly important role to play in both generating and assimilating new evidence to this ends.

- In 2025 the African Union will vote in a new chair. Under current arrangements the Chair answers to and implements the decisions of the African Union Assembly composed of the heads of the 55 member states and has little power to challenge heads of state on the sensitive politics of devolution, decentralisation or the transition from urban centres serving as landing pads for commodity extraction with all the associated corruption to the diverse economic hubs envisaged in Agenda 2063 (AU, 2015). Underpinning this challenge are the meagre contributions of African Union member states to the operations of the African Union – just a third of the African Union’s budget is provided by member states - reiterating the dependence on international contributions. For an institution intended to assert Africa’s independence from foreign powers, the funding of the African Union has entrenched many existing dependencies and evidentiary pathways. If the African Union’s evidentiary base informing urban policy is to be re-enlivened by regional evidence actors in order to meet the challenges and opportunities associated with urbanisation, this will have to be demanded by the AU Assembly. If not, the regional responsibility is likely to fall to UNECA and the AfDB.

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Urbanization Review, citing 2019 World Bank data, suggests that 47% of household heads in Dar es Salaam work in the “low-value-added services” sector (World Bank, 2021). |

| 2 |

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. (2004). INSTITUTIONS AS THE FUNDAMENTAL CAUSE OF LONG-RUN GROWTH.

- Adam, A., and Madell, C. (2013). The State of Planning in Africa - an overview. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2024/08/auf2024_background_document.pdf.

- Adams, W., and Sandbrook, C. (2013). Conservation, evidence and policy. Oryx 47. [CrossRef]

- AfDB (2024) Tanzania: Arusha Sustainable Water and Sanitation Delivery Project – Project 2025/26. Ministry of Water. https://www.maji.go.tz/uploads/publications/sw1664866566WSDP%20III%20FINAL%20FINAL%202022%20(1).pdf.

- AfDB (2024). African Economic Outlook 2024 African Development Bank Group. African Dev. Bank. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/african-economic-outlook-2024.

- AfDB (2024). African Economic Outlook 2024 African Development Bank Group. African Dev. Bank. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/african-economic-outlook-2024.

- AfDB (African Development Bank) (2022) Ethiopia: Country Strategy Paper 2023-2027 and 2022 Country Portfolio Performance Review. East Africa Regional Development Business Delivery Office, Country Economics Department, Ethiopia Country Office.

- African Business (2024) Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Vision for Clean and Comfortable Cities: A Renewed Commitment to Urban Sanitation https://african.business/2024/04/apo-newsfeed/prime-minister-abiy-ahmeds-vision-for-clean-and-comfortable-cities-a-renewed-commitment-to-urban-sanitation.

- African Union (AU), (2024) Sustainable Urbanization for Africa’s Transformation: Agenda 2063.

- Alem, G. (2021). Urban plans and conflicting interests in sustainable cross-boundary land governance, the case of national urban and regional plans in Ethiopia. Sustain. 13. [CrossRef]

- Allen, N. (2021) The promises and perils of Africa’s digital revolution. Brookings Commentary https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-promises-and-perils-of-africas-digital-revolution/.

- Amani, H; Makene, F; Ngowi, D; Matinyi, Y; Martine, M and Tunguhole, J (2018) Understanding the scope for urban infrastructure and services finance in Tanzanian cities. Background paper for the Coalition for Urban Transitions, ESRF (October) .

- Bekker, S., Croese, S., and Pieterse, E. (2021). Refractions of the National, the Popular and the Global in African Cities.

- Branch, D., Cheeseman, N., Branch, D., and Cheeseman, N. (2006). The Politics of Control in Kenya : Understanding the Bureaucratic-Executive State, 1952-78 Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article : The Politics of Control in Kenya : Understanding the Bureaucratic- executive State, 1952-78. Taylor Fr. Ltd 33, 11–31. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D., and McGranahan, G. (2016). The urban informal economy, local inclusion and achieving a global green transformation. Habitat Int. 53, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Caria, S. (2019). Industrialization on a Knife’s Edge: Productivity, Labor Costs and the Rise of Manufacturing in Ethiopi. Ind. a Knife’s Edge Product. Labor Costs Rise Manuf. Ethiop. [CrossRef]

- Cash, D., and Belloy, P. (2020). Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in a Rapidly Shifting World of Knowledge and Action. Sustainability 12. [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V., and Bulkeley, H. (2013). A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 23, 92–102. [CrossRef]

- Change, C. (2023). Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change. [CrossRef]

- Cloete B, Kazibon L, and Ramkolowan Y, 2019. The Macro-economic Impact of Two Different Industrial Pathways in Tanzania. Background Paper produced for Tanzania Urbanisation.

- Cochrane, A and Ward, K (2012) Guest Editorial: Researching the geographies of.

- Collier, P (2016) African Urbanisation: an analytical policy guide. IGC Policy Brief (May).

- Committeri, M., and Spadafora, F. (2013). You Never Give Me Your Money? Sovereign Debt Crises, Collective Action Problems, and IMF Lending. IMF Work. Pap. 13, 1. [CrossRef]

- Croese, S., Cirolia, L. R., and Graham, N. (2016). Towards Habitat III: Confronting the disjuncture between global policy and local practice on Africa’s ‘challenge of slums.’ Habitat Int. 53, 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Decentralization for Improved Public Services and Socio-Economic Development.

- Design Initiative. https://www.kounkuey.org/projects/realising_urban_NbS.

- Diao, X., Kweka, J., Mcmillan, M., and Qureshi, Z. (2016). Economic Transformation in Africa from the Bottom Up : Macro and Micro Evidence from Tanzania. NBER Work. Pap. Ser., 1–65. [CrossRef]

- Dodman, D., Colenbrander, S., and Archer, D. (2017). “Conclusion,” in Responding to climate change in Asian cities: Governance for a more resilient urban future, eds. D. Archer, S. Colenbrander, and D. Dodman (Abingdon, UK: Routledge Earthscan).

- ECA/AfDB (2022). Africa ’ s Urbanisation Dynamics 2022. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/africa-s-urbanisation-dynamics-2022_3834ed5b-en.

- Elias, P., Shonowo, A., de Sherbinin, A., Hultquist, C., Danielsen, F., Cooper, C., et al. (2023). Mapping the Landscape of Citizen Science in Africa: Assessing its Potential Contributions to Sustainable Development Goals 6 and 11 on Access to Clean Water and Sanitation and Sustainable Cities. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 8, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Economic and Social Research Foundation (ESRF) (2025) Proceedings at the 2025 hosting of the TULab.

- Economy Watch (2024) Path to Fiscal Independence: Achieving Revenue Self Sufficiency for Tanzania local Governments.

- Faguet, J.-P., Khan, Q., and Kanth, D. P. (2021). Decentralization’s Effects on Education and Health: Evidence from Ethiopia. Publius J. Fed. 51, 79–103. [CrossRef]

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) (2020) A Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda: A Pathway to Prosperity. Ministry of Finance, March. https://www.mofed.gov.et/media/filer_public/38/78/3878265a-1565-4be4-8ac9-dee9ea1f4f1a/a_homegrown_economic_reform_agenda-_a_pathway_to_prosperity_-_public_version_-_march_2020-.pdf .

- Gebre-Egziabher T and Yemeru EA (2019) Urba- nization and industrial development in Ethio- pia. In: Cheru F, Cramer C and Oqubay A (eds) The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 785–804.

- Gebrehiwot, A. B. (2020). Boosting Ethiopia’s Industrialization: What can be learned from China.

- Gebrehiwot, A. B. (2020). Boosting Ethiopia’s Industrialization: What can be learned from China.

- Girma, M., and Mulatu, Z. (2025). Evaluating corridor development initiatives and their effects in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Urban, Plan. Transp. Res. 13. [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E. (2011). Triumph of the City. Penguin Publishing Group.

- Good Governance Africa (GGA) (2025) https://africainfact.com/.

- Goodfellow, T., and Huang, Z. (2021). Contingent infrastructure and the dilution of ‘Chineseness’: Reframing roads and rail in Kampala and Addis Ababa. Environ. Plan. A 53, 655–674. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, T., and Huang, Z. (2022). Manufacturing urbanism: Improvising the urban–industrial nexus through Chinese economic zones in Africa. Urban Stud. 59, 1459–1480. [CrossRef]

- Haile, F. (2024). Displaced for housing: analysing the uneven outcomes of the Addis Ababa Integrated Housing Development Program. Urban Geogr. 45, 6–12. [CrossRef]

- Hante, M. (2025) Director of Rural and Urban Development, PO-RALG. Commentary at at the 2025 TULab, hosted by ESRF in Dar es Salaam.

- Jana, A. (2025) Background Paper for South Africa’s hosting of the G20.

- Jasanoff, S. ed. (2006). States of knowledge. The co-production of science and social order. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jean-Baptiste N, Limbumba M, Ndezi, T, Njavike E, Schaechter E, Stephen S, Walnycki A, and Jenkins, M. W., Cumming, O., and Cairncross, S. (2015). Pit latrine emptying behavior and demand for sanitation services in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 2588–2611. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Baptiste, N; Limbumba M; Ndezi, T; N, Wernstedt, K (2019). Documenting Everyday Lives of Urban Tanzania. TULab Background Paper.

- Juffe Bignoli (2024) Eight reasons why development corridors might not be delivering positive outcomes for people and nature. Based on Juffe Bignoli, D., Burgess, N., Wijesinghe, A., Thorn, J. P. R., Brown, M., Gannon, K. E., et al. (2024). Towards more sustainable and inclusive development corridors in Africa. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N., Milward, K., and Sudarshan, R. (2013). Organising women workers in the informal economy. Gend. Dev. 21, 249–263. [CrossRef]

- Kaboub, F. (2024). Address to the UN Human Rights Council 2024 Social Forum, Geneva. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Digwnj1DoWI.

- Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. Am. Psychol. 58, 697–720. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. Am. Psychol. 58, 697–720. [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M. (2017). “Don’t call me Resilient Again!” The New Urban Agenda as Immunology… or... what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with “Smart Cities” and Indicators. Environ. Urban. 29, 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M. (2017). “Don’t call me Resilient Again!” The New Urban Agenda as Immunology… or... what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with “Smart Cities” and Indicators. Environ. Urban. 29, 89–102. [CrossRef]

- KDI (Kounkuey Design Initiative), n.d. Realizing urban nature-based solutions. Kounkuey.

- Kefale, A (2010) ‘Federal restructuring in Ethiopia: Renegotiating identity and borders along the Oromo–Somali ethnic frontiers’, Development and Change 41, 4 (2010), pp. 615–35;

- Khaunya, M. F., Wawire, B. P., and Chepng, V. (2015). Devolved Governance in Kenya ; Is it a False Start in Democratic Decentralization for Development ? Int. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. 4, 27–37. Available at: http://www.ejournalofbusiness.org/archive/vol4no1/vol4no1_4.pdf.

- Kihiko, M. K. (2018). “Industrial Parks as a Solution to Expanding Urbanization: A Case of Sub-Saharan Africa. IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.,” in Urbanization and Its Impact on Socio-Economic Growth in Developing Regions, 327–45.

- KoTDA (Konza Technopolis Development Authority) (2021) Strategic Plan 2021-2025. Retrieved.

- Kweka, J. (2018). Harnessing Special Economic Zones to Support Implementation of Tanzania’s Five-Year Development Plan 2016/17–2020/21.

- Kyessi, A. G. (2005). Community-based urban water management in fringe neighbourhoods : the case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 29, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Kyessi, A. G. (2005). Community-based urban water management in fringe neighbourhoods : the case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 29, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Kyule, B. M., and Wang, X. (2024). Quantifying the link between industrialization, urbanization, and economic growth over Kenya. Front. Archit. Res. 13, 799–808. [CrossRef]

- Kyule, B. M., and Wang, X. (2024). Quantifying the link between industrialization, urbanization, and economic growth over Kenya. Front. Archit. Res. 13, 799–808. [CrossRef]

- Lall, S. V., Henderson, J. V., and Venables, A. J. (2017). Africa’s Cities: Opening Doors to the World. [CrossRef]

- Lameck, W. U. (2023). Political decentralisation and political-administrative relation in the local councils in Tanzania. Public Adm. Policy 26, 335–344. [CrossRef]

- Lavers, T. (2018). Responding to land-based conflict in Ethiopia: The land rights of Ethnic minorities under federalism. Afr. Aff. (Lond). 117, 462–484. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C., Hamdock, A., and Elhiraika, A. (2016). Macroeconomic policy and structural transformation of economies.

- Lopes, C. (2024). The self-deception trap: exploriong the economic dimensions of chairty dependency within Africa-Europe relations. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. “Beyond Settler and Native as Political Identities: Overcoming the Political Legacy of Colonialism.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 43, no. 4, 2001, pp. 651–64. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2696665. Accessed 3 Apr. 2025.

- McGranahan, G., Schensul, D., and Singh, G. (2016). Inclusive urbanization: Can the 2030 Agenda be delivered without it? Environ. Urban. 28, 13–34. [CrossRef]

- Mcgranahan, G., Walnycki, A., Dominick, F., Kombe, W., Kyessi, A., Limbumba, T. M., et al. (2016). Universalising water and sanitation coverage in urban areas realities in Dar es Salaam, About the authors.

- Mcgranahan, G., Walnycki, A., Dominick, F., Kombe, W., Kyessi, A., Limbumba, T. M., et al. (2016). Universalising water and sanitation coverage in urban areas realities in Dar es Salaam, About the authors.

- Ministry of Finance and Planning (MoFP), Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (TNBS) and President’s Office – Finance and Planning, Office of the Chief Government Statistician, Zanzibar (2022) The 2022 Population and Housing Census: Age and Sex Distribution Report, Key Findings, Tanzania, December.

- Ministry of Industry (MoI) (2021) What is New in Ethiopia’s New Industrial Policy: Policy Direction and Sectoral Priorities (3 March). https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/aldc_2022_pdsd_eth_pdw_3-4_mar_ppt_worku_gebeyehu_eng.pdf.

- Mkandawire, T and Soludo, C (1999) Our Continent, Our Future: African Perspectives on Structural Adjustment. Dakar: CODESRIA.

- Mo Ibrahim Foundation (MIF) (2024). The Power of Data for Long-lasting Change. 13.

- Mo Ibrahim Foundation (MIF) (2024). The Power of Data for Long-lasting Change. 13.

- Morrison, N. (2017). Playing by the rules ? New institutionalism, path dependency and informal settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, N. (2017). Playing by the rules ? New institutionalism, path dependency and informal settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. [CrossRef]

- Mshinda, H. (2025) Former Director General of Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology in Tanzania. Commentary at at the 2025 TULab, hosted by ESRF in Dar es Salaam.

- Nationally Determined Contribution. UN Climate Change Learning Partnership,.

- NCCG (Nairobi City County Government), 2022. NMS Officially Hands Back to City Hall All ndcsp-kenya-ndc-finance-strategy.pdf.

- Nepad (2025) Agenda 2063: flagship projects. The African Economic Platform. https://www.nepad.org/agenda-2063/flagship-project/african-economic-platform.

- Oates, L., and Sudmant, A. (2024). Infrastructure Transitions in Southern Cities: Organising Urban Service Delivery for Climate and Development. 12, 1–17.

- Oqubay, A. (2018). and Late Industrialisation in Ethiopia. Ind. Africa, 28. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/WPS_No_303__Industrial_Policy_and_Late_Industrialization_in_Ethiopia_B.pdf.

- Parnell, S., and Pieterse, E. (2014). “Africa’s Urban Revolution,” in (JUTA).

- Peter, L. L., and Yang, Y. (2019). Urban planning historical review of master plans and the way towards a sustainable city: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Front. Archit. Res. 8, 359–377. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, E. (2014). Integrated Urban Development Framework. 0, 1–62.

- Planning.

- policy mobility: confronting the methodological challenges. Environment and Planning A, 44(1) pp. 5–12.

- Potts, D. (2018). Urban data and definitions in sub-Saharan Africa: Mismatches between the pace of urbanisation and employment and livelihood change. Urban Stud. 55, 965–986. [CrossRef]

- President’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government.

- Rift Valley Institute (RFI) (2025) https://riftvalley.net/.

- Robinson, J., Harrison, P., Croese, S., Sheburah Essien, R., Kombe, W., Lane, M., et al. (2024). Reframing urban development politics: Transcalarity in sovereign, developmental and private circuits. Urban Stud. 62, 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M., Zawdie, G., and Malairaja, C. (2008). The triple helix strategy for universities in developing countries: The experiences in Malaysia and Algeria. Sci. Public Policy 35, 431–443. [CrossRef]

- Scope for Urban Infrastructure and Services Finance in Tanzanian Cities. Background.

- Seddon, J. (2015) Tedx Bonn.

- Singh, C., Madhavan, M., Arvind, J., and Bazaz, A. B. (2021). Climate change adaptation in Indian cities: a review of existing actions and spaces for triple wins (submitted). Urban Clim. 36, 100783. [CrossRef]

- Slum Dwellers International (SDI) “Know your city” https://sdinet.org/video/the-know-your-city-campaign/.

- Social Management Framework (ESMF). President’s Office - Regional Administration and Local Government (PO - RALG).

- Social Management Framework (ESMF). President’s Office - Regional Administration and Local Government (PO - RALG).

- Steinlin, M. (2023) The Urbanisation Dimension.

- Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf.

- Thieme, T. A. (2018). The hustle economy: Informality, uncertainty and the geographies of getting by. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 42, 529–548. [CrossRef]

- Thieme, T. A. (2018). The hustle economy: Informality, uncertainty and the geographies of getting by. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 42, 529–548. [CrossRef]

- Trade and Development. Retrieved October 6, 2024, from.

- TULab (Tanzania Urbanisation Laboratory) (2019) Harnessing Urbanisation for Development: Roadmap for Tanzania’s Urban Development Policy. Paper for the Coalition for Urban Transitions.

- TULab (Tanzania Urbanisation Laboratory) (2025) ESRF report detailing the proceedings of the TULab on .

- Turok, I. (2014). “Linking urbanisation and development in Africa ’ s economic revival,” in Africa’s Urban Revolution, eds. S. Parnell and E. Pieterse (London and New York: Zed Books).

- UCLGA (United Cities and Local Governments of Africa) (2023). African Decentralisation Day will be celebrated at a national level on 10 August 2023. Retrieved from https://www.uclga.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/En-African-Decentralisation-Day-will-be-.

- UNCDF (United Nations Capital Development Fund), 2024. Tanga UWASA Issues Historic.

- UNCTAD (UN Trade and Development) (2023) Ensuring Safe Water and Sanitation for All: A https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/dtltikd2022d1_en.pdf.

- UNCTAD (2024) Handbook of Statistics 2024. https://unctad.org/publication/handbook-statistics-2024.

- UNECA (United Nations. Economic Commission for Africa) (2023). Informal Cross-Border Trade in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region 2023. https://hdl.handle.net/10855/50209.

- UNECA (United Nations. Economic Commission for Africa) (2024). State of urbanization in Africa: digital transformation for inclusive, resilient and sustainable urbanization November 2024.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2021) Local Government Decentralization Policy in Tanzania.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2022) The Public Service Regulation, 2022 GN No. 444.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2023) Dar es Salaam Metropolitan Development Project – Phase 2: Environmental and.

- Vatn, A., and Bromley, D. (1994). Choices wihtout apologies without prices. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 26, 129–148.

- Venables, A. J. (2007). Evaluating urban transport improvements: Cost-benefit analysis in the presence of agglomeration and income taxation. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 41(2), 173–188.

- Wachsmuth, D., Cohen, D. A., and Angelo, H. (2016). Expand the frontiers of urban sustainability. Nature 536, 391–393. [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D., Cohen, D. A., and Angelo, H. (2016). Expand the frontiers of urban sustainability. Nature 536, 391–393. [CrossRef]

- Water Global Practice: Eastern and Southern Africa Region.

- Water Infrastructure Green Bond Valued at TZS 53.12 Billion. Retrieved from https://www.uncdf.org/article/8664/tanga-uwasa-issues-historic-water-infrastructure-.

- WaterAid Tanzania, 2023. WaterAid Tanzania Country Programme Strategy 2023-2028.

- Watson, V. (2014). “Seeing from the South,” in LEARNING PLANNING FROM THE SOUTH Ideas from the new urban frontiers in Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South.

- World Bank (2015) Ethiopia’s Great Run: Growth acceleration and how to pace it https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ethiopia/publication/ethiopia-great-run-growth-acceleration-how-to-pace-it.

- World Bank (2021) Transforming Tanzania’s Cities: harnessing urbanization for competitiveness, resilience and livability. Urbanization Review (Unpublished by Tanzanian Government) https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/811221624876806983/pdf/Transforming-Tanzania-s-Cities-Harnessing-Urbanization-for-Competitiveness-Resilience-and-Livability.pdf .

- World Bank (2025) Statistical Performance Indicators, Overall Score. World Bank Database. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/statistical-performance-indicators.

- World Bank, (2021) Urban Local Government Strengthening Program. Report No: ICR00005350.

- World Bank, (2024a) Kenya Urban Support Program. Report No: ICR00006535. Urban,.

- World Bank, (2024b) Second Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project. Report No: PAD5636.

- Worral, L., Colenbrander, S., Palmer, I., Makene, F., Mushi, D., Kida, T., et al. (2017). Better Urban Growth in Tanzania.

- Wyborn, C.; Datta, A.; Montana, J.; Ryan, M.; Leith, P.; Chaffin, B.; Miller, C.; van Kerkhoff, L. (2019). Co-Producing Sustainability: Reordering the Governance of Science, Policy, and Practice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 44, 319–346.

- Ziervogel, G., Archer van Garderen, E., and Price, P. (2016). Strengthening the knowledge – policy interface through co-production of a climate adaptation plan: leveraging opportunities in Bergrivier Municipality, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 28, 455–474. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).