Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Working Principle and Performance Requirements of Anion Exchange Membrane

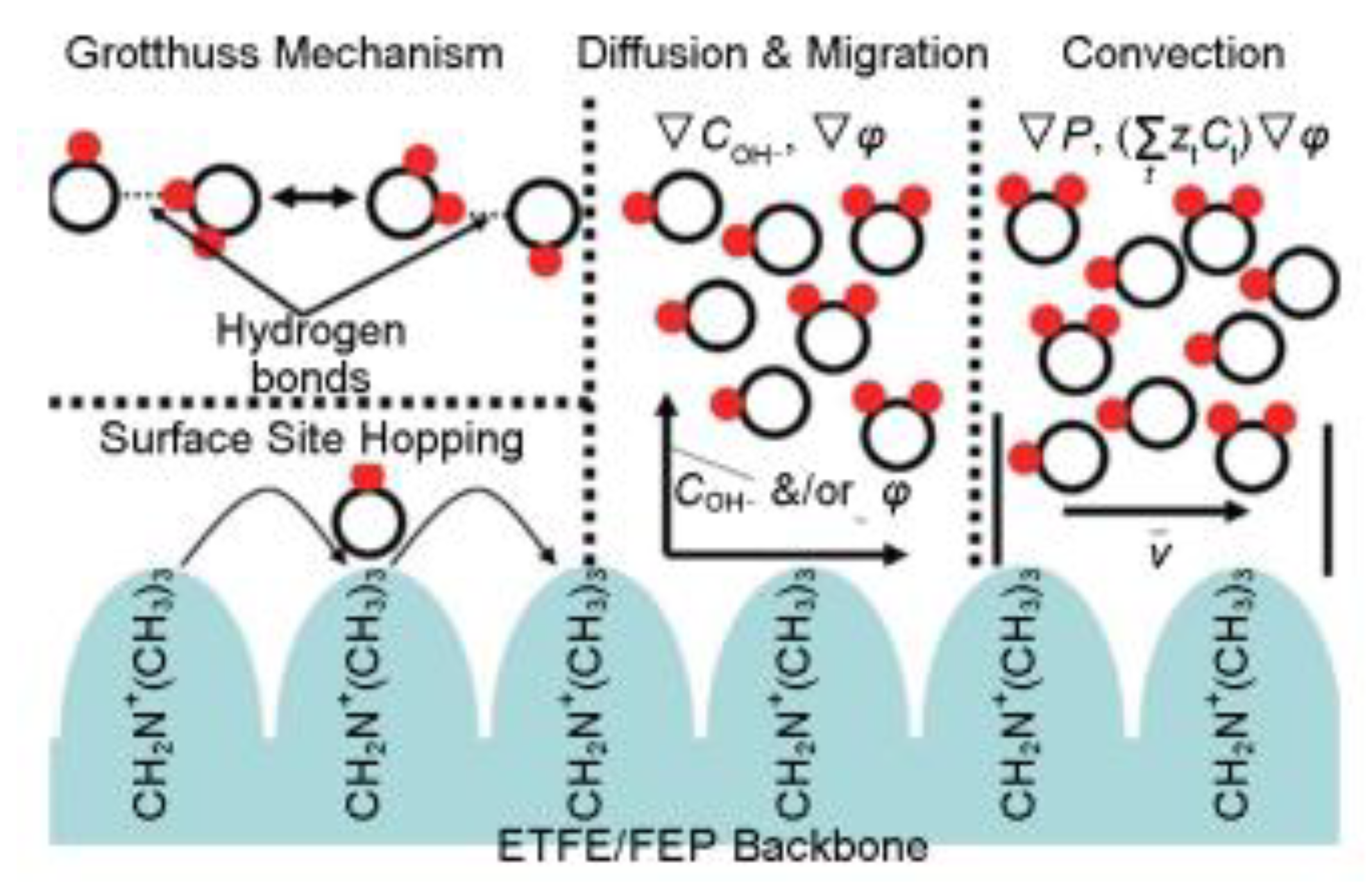

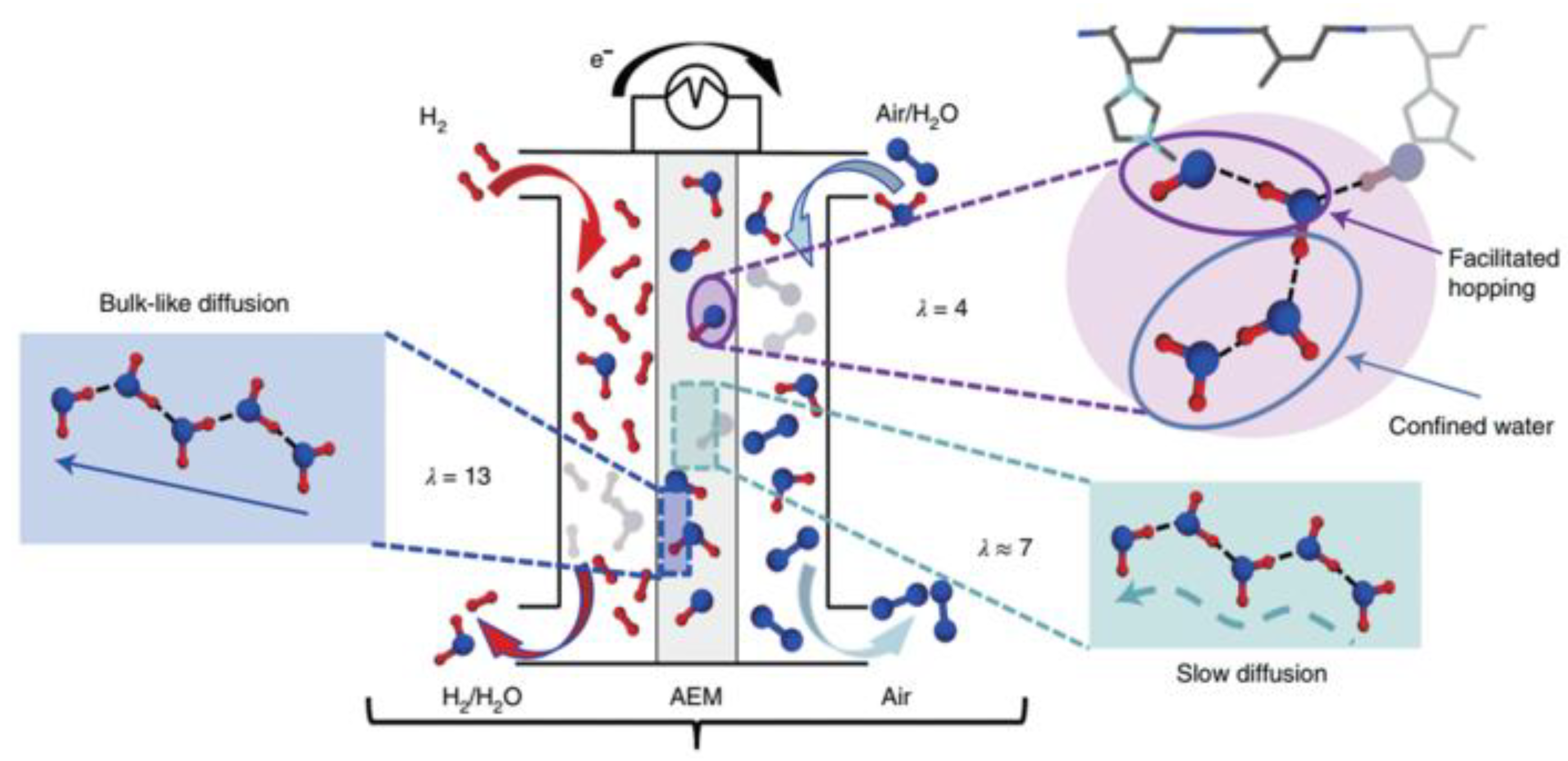

2.1. Working Principle of Anion Exchange Membrane

2.2. Performance Requirements for Anion Exchange Membranes

3. Research Progress on Anion Exchange Membranes

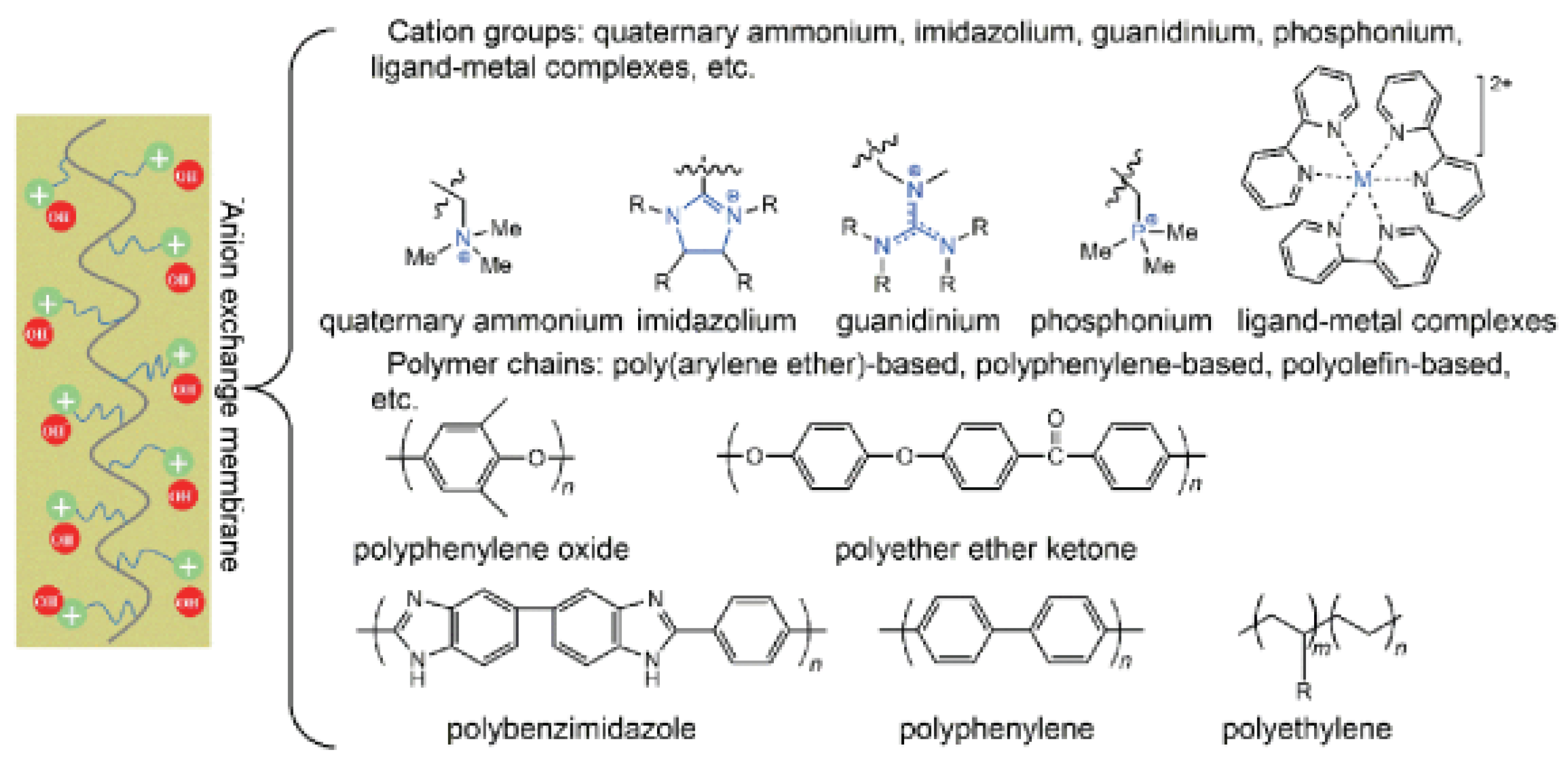

3.1. Cationic Group Structure Design

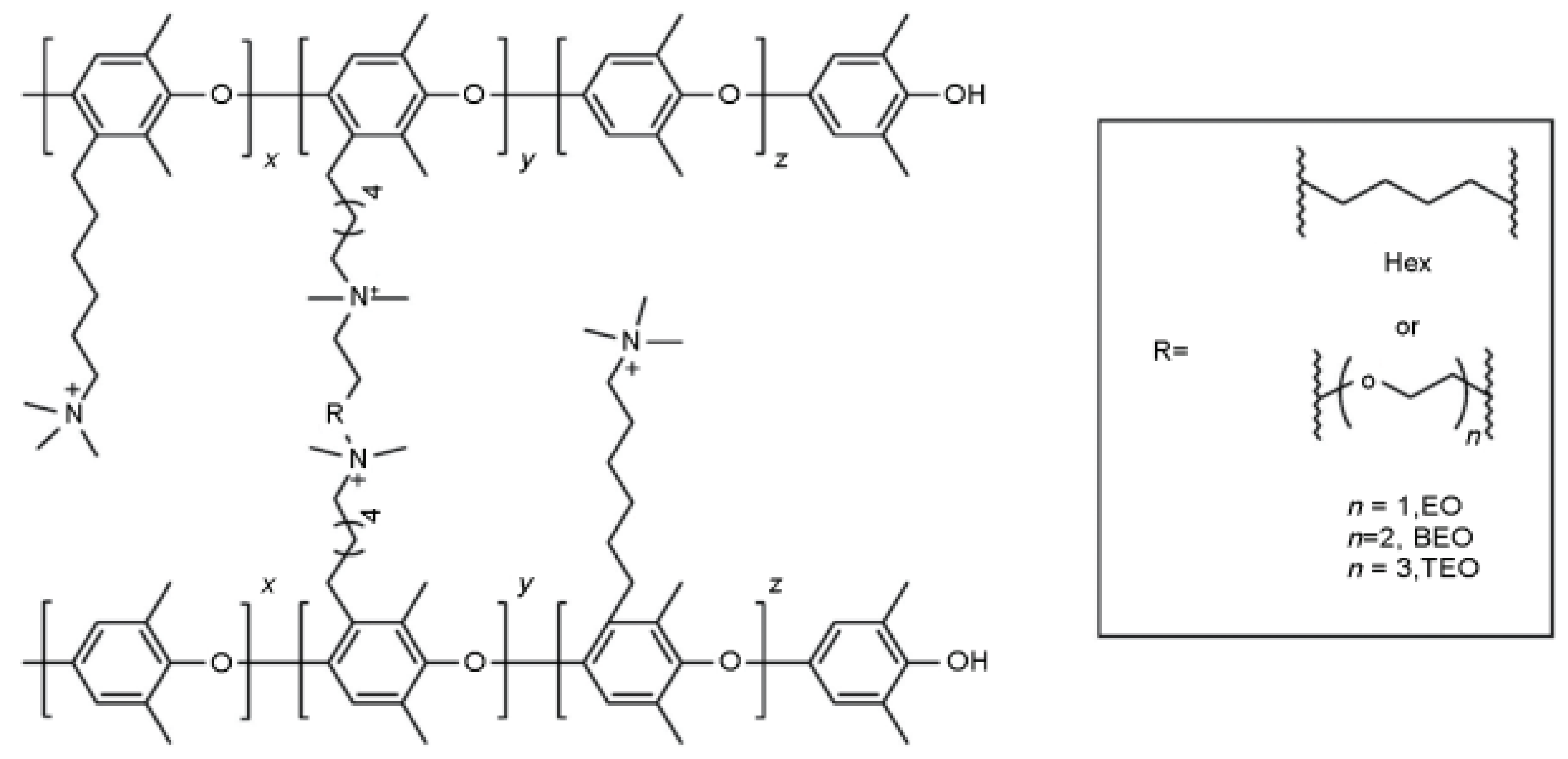

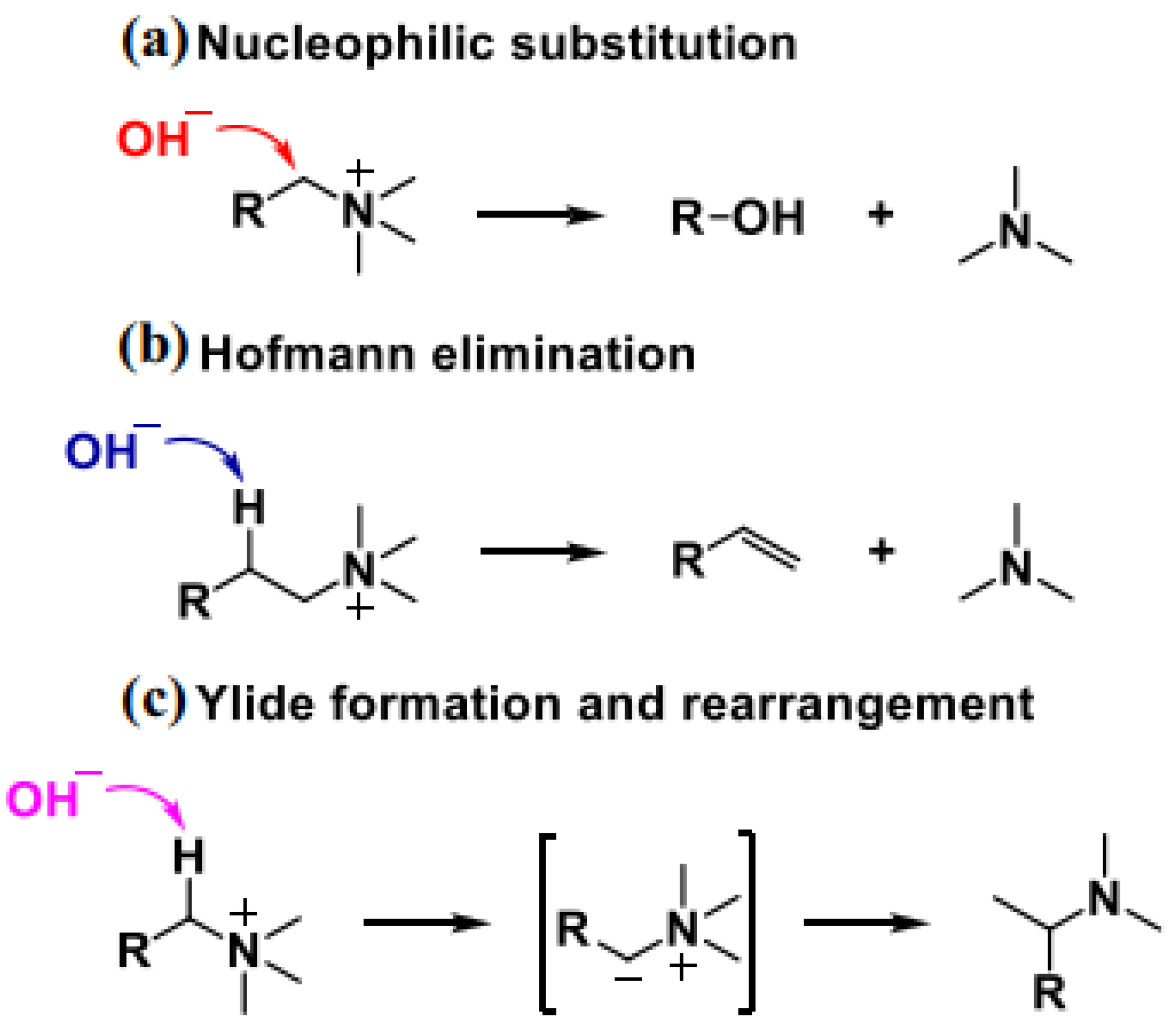

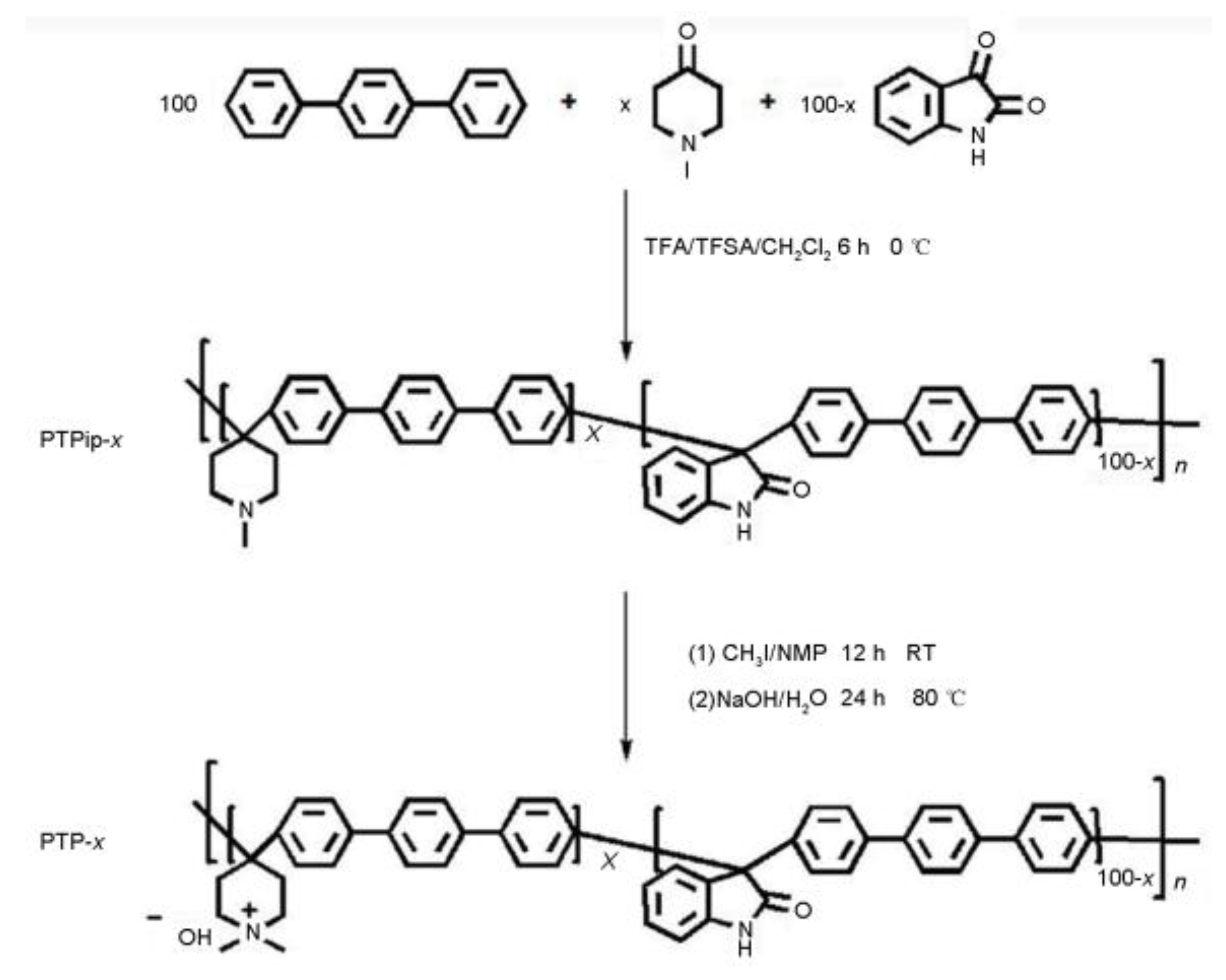

3.1.1. Quaternary Ammonium Cation

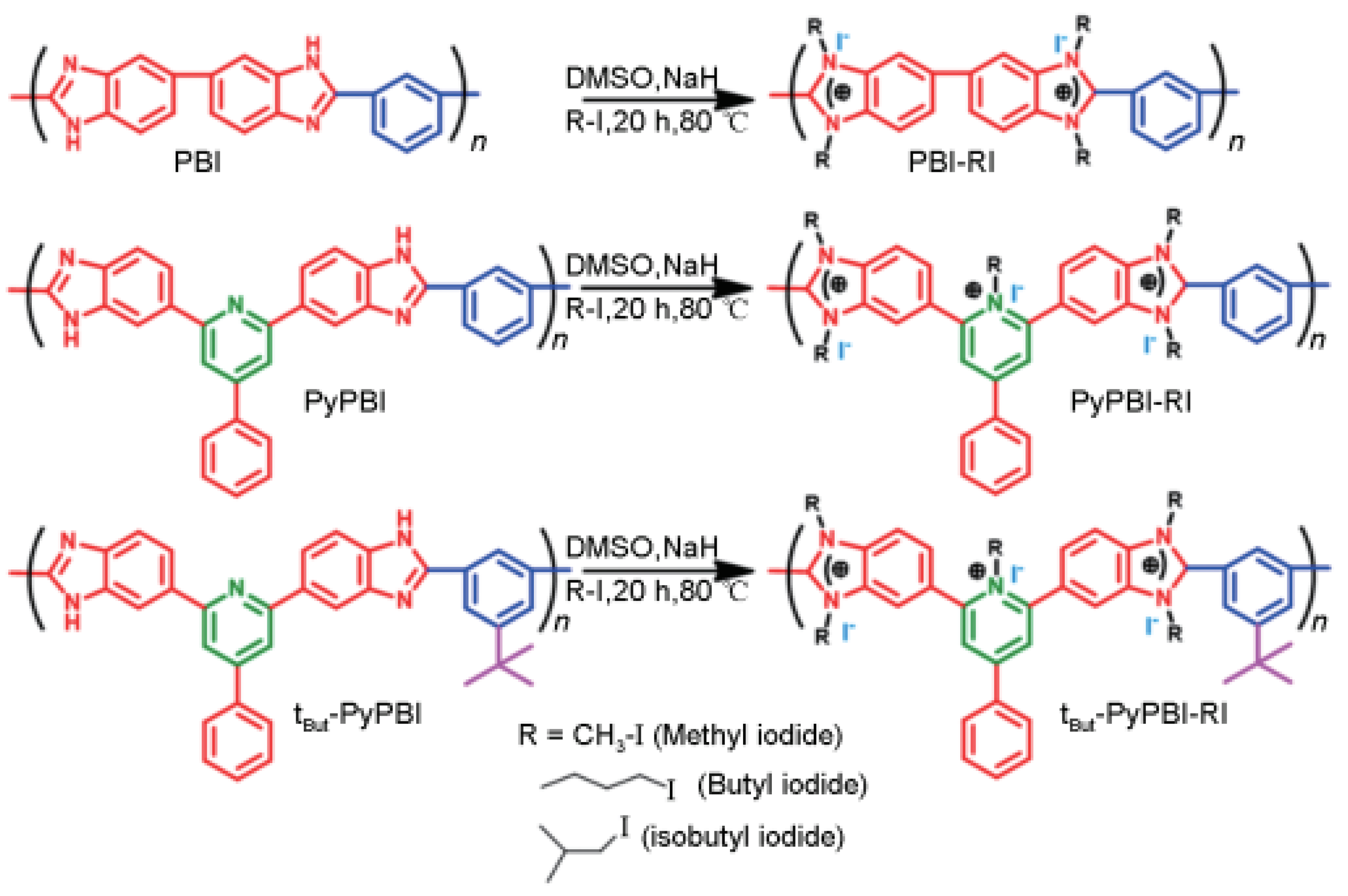

3.1.2. Imidazole Type Cations

3.1.3. Quaternary Guanidine Cation

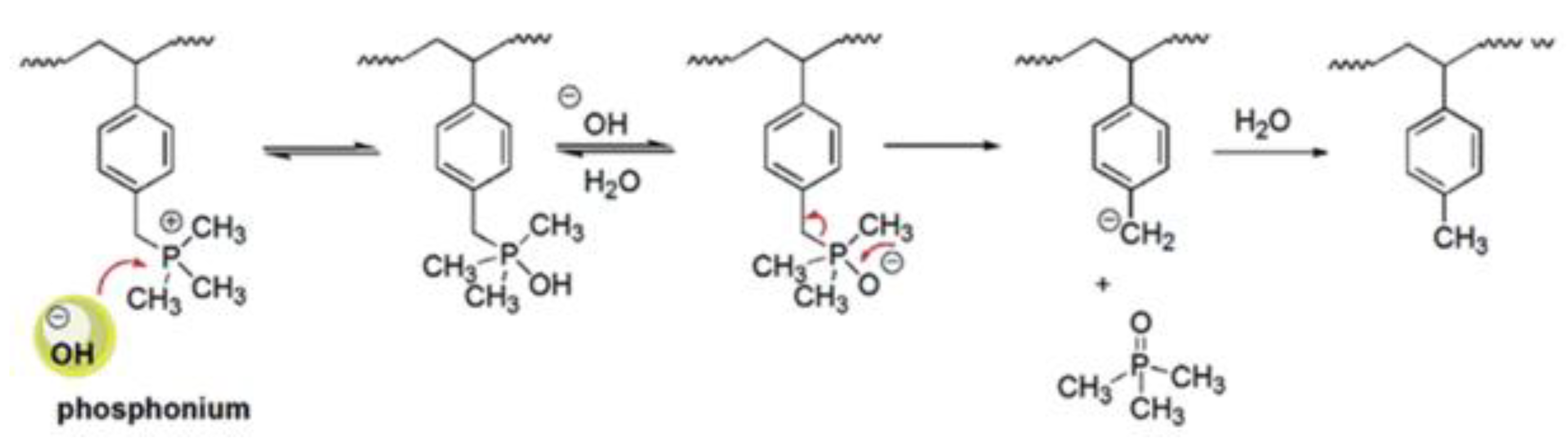

3.1.4. Quaternary Cations

3.1.5. Metal Cations

3.2. Polymer Main Chain Design

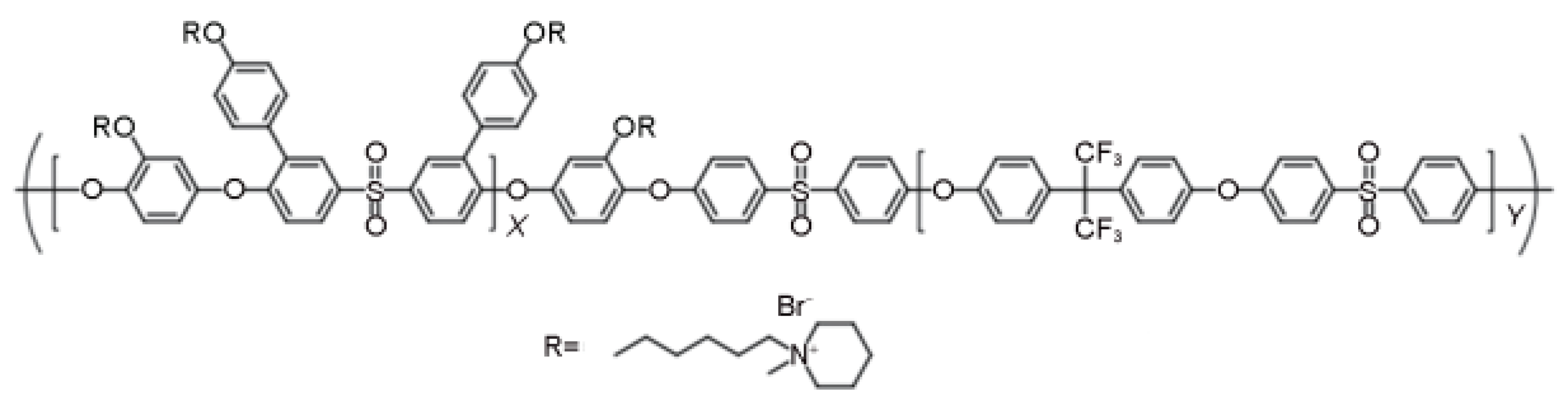

3.2.1. Polyarylether Based Main Chain

3.2.2. Non Ether Oxygen Bonded Aromatic Main Chain

4. Conclusions and Prospect

- (1)

- The issue of balancing OH− conductivity with mechanical/dimensional stability. Compared to H+, OH− has a larger size and lower diffusion rate, with a diffusion rate only about half that of H+. This inherent difference itself determines that preparing AEM with high ion conductivity is more challenging compared to PEM membranes. Secondly, when AEM operates in an air environment, OH− may react with CO2 in the air, producing carbonates or bicarbonates that can also affect ion conduction. In addition, most AEMs rely on increasing IEC to improve ion conductivity, but this inevitably sacrifices size/mechanical stability, leading to excessive membrane expansion under fully humidified conditions.

- (2)

- Alkali stability issue. Due to the long-term operation of AEMWE electrolysis cells under high temperature and strong alkali conditions (60-80 °C), the presence of strong nucleophilic OH− poses higher requirements for the alkali resistance and electrochemical stability of cationic groups and polymer main chains. By modifying the cation and polymer backbone, the alkali stability of AEM has been improved to a certain extent. However, the stability of AEM under actual working conditions still faces challenges.

- (3)

- The issue of preparation cost. Although high-performance AEMs can be prepared through functionalization, cross-linking, and copolymerization, the complexity of raw materials and synthesis processes results in high preparation costs, limiting their applications.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Aili, M.R. Kraglund, M.R. Kraglund, S.C. Rajappan, D. Serhiichuk, Y. Xia, V. Deimede, J. Kallitsis, C. Bae, P. Jannasch, D. Henkensmeier, J.O. Jensen, Electrode Separators for the Next-Generation Alkaline Water Electrolyzers, ACS Energy Lett., 2023, 8, 4, 1900–1910. [CrossRef]

- Steele, B.C.H., Heinzel, A.: Materials for fuel-cell technologies, Nature 414, 345–352 (2001). [CrossRef]

- R. Vinodh, S.S. Kalanur, S.K. Natarajan, S.K. Natarajan, Recent Advancements of Polymeric Membranes in Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer (AEMWE): A Critical Review, Polymers 2023, 15(9), 2144. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xu, L. Zhang, J. Zhang, J. Wang, Y. Hu, H. Jiang, C. Li, Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer: Electrode Design, Lab-Scaled Testing System and Performance Evaluation, EnergyChem, 2022, 4(5): 100087. [CrossRef]

- W. Lei, X.Zi’ang, W.P. Can, X. Qin, W. Bao, Progress of alkaline-resistant ion membranes for hydrogen production by water electrolysis, Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress, 2022, 41(3): 1556-1568. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., He, G.H., Zhang, F. X.: A mini-review on anion exchange membranes for fuel cell applications: stability issue and addressing strategies. Int. J. Hydro. Energy 40, 7348–7360 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Emin, D. A, S. Ali, J. Sayed, M. Chhattal, S. Muntaha, A. Parkash, Q. Li, Facile electrodeposition of CoMn2O4 nanoparticles on nickel foam as an electrode material for supercapacitors, Electrochim. Acta, 501 (2024) 144766. [CrossRef]

- Emin, J. Li, Y. Dong, Y. Fu, D. He, Y. Li, Facilely prepared nickel-manganese layered double hydroxide-supported manganese dioxide on nickel foam for aqueous supercapacitors with high performance, J. Energy Storage, 65 (2023) 107340. [CrossRef]

- Emin, J. Li, Y. Dong, S. Shen, D. Li, Y. Chen, J. Hu, Y. Fu, D. He, Y. L, Flexible free-standing electrode of nickel-manganese oxide with a cracked-bark shape composited with aggregated nanoparticles on carbon cloth for high-performance aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors, ACS Appl. Energy Mater., 6 (2023) 9637–9645. [CrossRef]

- K.N. Grew, W.K.S. Chiu, A Dusty Fluid Model for Predicting Hydroxyl Anion Conductivity in Alkaline Anion Exchange Membranes, Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 2010, 157(3): B327. [CrossRef]

- S. Gottesfeld, D.R. Dekel, M. Page, C. Bae,Y. Yan, P. Zelenay, Y.S. Kim, Anion exchange membrane fuel cells: Current status and remaining challenges, J. Power Sources, 75, 2018, 170-184. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, A.M. Villarino, C.R. Peltier, A.J. Macbeth, Y. Yang, M-J. Kim, Z. Shi, M.R. Krumov, C. Lei, G.G. Rodríguez-Calero, J. SotoSeung-Ho, Y.F. Mutolo, L. Xiao, L. Zhuang, D.A. Muller, G.W. Coates, P. Zelenay, H.D. Abruña, J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 17, 7901–7912.

- F. Foglia, Q. Berrod, A.J. Clancy, K. Smith, G. Gebel, V.G. Sakai, M. Appel, J-M. Zanotti, M. Tyagi, N. Mahmoudi, T.S. Miller, J.R. Varcoe, A.P. Periasamy, D.J. L. Brett, P.R. Shearing, S.L. Yonnard, P.F. McMillan, Disentangling water, ion and polymer dynamics in an anion exchange membrane, Nature Materials, 2022, 21(5): 555–563. [CrossRef]

- K.J.T. NoonanKristina, M.H. Henry, A. Kostalik, I.B. Lobkovsky, H.D. Abruña, G.W. Coates, Phosphonium-functionalized polyethylene: A new class of basestable alkaline anion exchange membranes, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2012, 134, 44, 18161–18164. [CrossRef]

- Emin, B. Gong, H. Jiang, Fish-scale-like NiMn-based layered double hydroxides for high-energy aqueous supercapacitors, Rare Metals. [CrossRef]

- J. Xue, J. Zhang, X. Liu, T. Huang, H. Jiang, Y. Yin, Y. Qin, M.D. Guiver, Toward alkaline-stable anion exchange membranes in fuel cells: cycloaliphatic quaternary ammonium-based anion conductors, Electrochemical Energy Reviews, 2022, 5(2): 348-400. [CrossRef]

- Emin, Y. Li, G. Zhe, Y. Dong, S. Shen, D. Li, Y. Chen, Y. Fu, D. He, J. Li, Facile synthesis of NiMn2S4 nanoflakes on nickel foam for high-performance aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors, Sci. China Technol. Sci., 67 (2024) 499–508. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao, H. Zhang, X. Zhao, Y. Wang, H. Zhu, X. Kong, Y. Liang, T. Ou, R. Ren, Y. Gu, Y. Su, J. Zhang, Recent advances in anion exchange membranes, Chinese J. Structural Chemistry, 44, 5, 2025, 100563. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu, H. Ma, M. Khan, B.S. Hsiao, Recent advances and challenges in anion exchange membranes development/application for water electrolysis: A review. Membranes, 2024, 14(4): 85. [CrossRef]

- Emin, W. Xie, X. Long, X. Wang, X. Song, Y. Chen, Y. Fu, J. Li, Y. Li, D. He, High-performance aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors based on the cathode of one-step electrodeposited cracked bark-shaped nickel manganese sulfides on activated carbon cloth, Sci. China Technol. Sci., 65 (2022) 293–301. [CrossRef]

- Salama. U, Shalahin. N, A mini-review on alkaline stability of imidazolium cations and imidazolium-based anion exchange membranes. Results in Materials, 2023, 17: 100366. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Hugar, H.A. Kostalik, I.W. Coates, Imidazolium Cations with Exceptional Alkaline Stability: A Systematic Study of Structure-Stability Relationships, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 27, 8730–8737. [CrossRef]

- Musker, W.K., Stevens, R.R.: Nitrogen ylides. IV. The role of the methyl hydrogen atoms in the decomposition of tetramethylammonium alkoxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 3515–3521 (1968). [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, M.R., Alkaline stability of poly(phenylene)-based anion exchange membranes with various cations. J. Polym Sci. Part B Polym Phys., 51, 1736–1742 (2013). [CrossRef]

- J. Pereira, R. Souza, A. Moita, A Review of Ionic Liquids and Their Composites with Nanoparticles for Electrochemical Applications, Inorganics 2024, 12(7), 186. [CrossRef]

- Zhu. T.Y, Sha. Y, Firouzjaie. H.A, Rational synthesis of metallo-cations toward redox- and alkaline-stable metallopolyelectrolytes, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142(2): 1083–1089. [CrossRef]

- F. Scarpelli,N. Godbert,A. Crispini, I. Aiello, Nanostructured Iridium Oxide: State of the Art, Inorganics 2022, 10(8), 115. [CrossRef]

- N. Chen, H.H. Wang, S.P. Kim, H.M. Kim, W.H. Lee, C. Hu, J.Y. Bae, E.S. Sim,Y.C. Chung, J-H. Jang, S.J. Yoo, Y. Zhuang, Y.M. Lee, Poly(fluorenyl aryl piperidinium) membranes and ionomers for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Commun., 2021, 12: 2367. [CrossRef]

- Z. Shi, X. Zhang, X. Lin, G. Liu, C. Ling, S. Xi, B. Chen, Y. Ge, C. Tan, Z. Lai, Z. Huang, Xi. Ruan, L. Zhai, L. Li, Z. Li, X. Wang, G-H. Nam, J. Liu, Q. He, Z. Guan, J. Wang, C.S. Lee, Anthony R.J. Kucernak, H. Zhang, Phase-dependent growth of Pt on MoS2 for highly efficient H2 evolution, Nature 621, 300–305 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Gottesfeld, D.R. Dekel, M. Page, C. Bae, Y. Yan, P. Zelenay, Y.S. Kim, Anion exchange membrane fuel cells: Current status and remaining challenges, J. Power Sources, 2018, 375: 170-184. [CrossRef]

- Emin, J. Li, X. Song, Y. Fu, D. He, Y. Li, A flexible cathode of nickel-manganese sulfide microparticles on carbon cloth for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors with high comprehensive performance, J. Power Sources, 551 (2022) 232185. [CrossRef]

- H. Xie, Z. Zhao, T. Liu, Y. Wu, C. Lan, W. Jiang, L. Zhu, Y. Wang, D. Yang, Z, Shao, A membrane-based seawater electrolyser for hydrogen generation, Nature 612, 673–678 (2022). [CrossRef]

- T. Sun, Z. Tang, W. Zang, Z. Li, J. Li, Z. Li, L. Cao, J.S.D. Rodriguez, C.O.M. Mariano, H. Xu, P. Lyu, X. Hai, H. Lin, X. Sheng, J. Shi, Y. Zheng, Y.R. Lu, Q. He, J. Chen, K.S. Novoselov, C.H. Chuang, S. Xi, X. Luo, J. Lu, Ferromagnetic single-atom spin catalyst for boosting water splitting, Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 763–771 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu. X, Xie. N, Xue. J.D, Magnetic-field-oriented mixedvalence-stabilized ferrocenium anion-exchange membranes for fuel cells, Nature Energy, 2022, 7: 329–339. [CrossRef]

- M. Ronovský, O. Dunseath, T. Hrbek, P. KúšMatija, G. Shlomi, P.K. Daniel, G. Nedumkulam, A.S. Enrico, P. Francisco, R.Z. Nejc, H. Alex, M. Bonastre, P. Strasser, J. Drnec, Origins of Nanoalloy Catalysts Degradation during Membrane Electrode Assembly Fabrication, ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 10, 5251–5258. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, X. Fu, Ib. Chorkendor, J.K. Nørskov, Electrochemical Ammonia Synthesis: The Energy Efficiency Challenge, ACS Energy Lett. 2025, 10, 1, 128–132. [CrossRef]

- Y. He, L. Jia, X. Lu, C. Wang, X. Liu, G. Chen, D. Wu, Z. Wen, N. Zhang, Y. Yamauchi, T. Sasaki, R. Ma, Molecular-Scale Manipulation of Layer Sequence in Heteroassembled Nanosheet Films toward Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysts, ACS Nano, 2022, 16, 3, 4028–4040. [CrossRef]

- S. Gnaim, A. Bauer, H.J. Zhang, L. Chen, C. Gannett, C.A. Malapit, D.E. Hill, D. Vogt, T. Tang, R.A. Daley, W. Hao, R. Zeng, M. Quertenmont, W.D. Beck, E. Kandahari, J.C. Vantourout, P.G. Echeverria, H.D. Abruna, D.G. Blackmond, S.D. Minteer, S.E. Reisman, M.S. Sigman, P.S. Baran, Cobalt-electrocatalytic HAT for functionalization of unsaturated C-C bonds, Nature 605, 687–695 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Khalil, I. Dincer, Experimental investigation of newly designed 3D-printed electrodes for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media, Energy, 304, 30, 2024, 132017. [CrossRef]

- S.G. Peera, S-W. Kim, S. Ashmath, T-G. Lee, Sustainable Fe3C/Fe-Nx-C Cathode Catalyst from Biomass for an Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Alkaline Electrolytes and Zinc-Air Battery Application, Inorganics 2025, 13(5), 143. [CrossRef]

- W.H. Lee, C.W. Lee, G.D. Cha, B.H. Lee, J.H. Jeong, H. Park, J. Heo, M.S. Bootharaju, S.H. Sunwoo, J.H. Kim, K.H. Ahn, D.H. Kim, T. Hyeon, Floatable photocatalytic hydrogel nanocomposites for large-scale solar hydrogen production, Nat.Nanotechnol., 18, 754–762 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, Y. Guo, Z. Zhang, X. Zhang, Q. Ji, H. Zhang, Z. Song, D. Liu, J. Zeng, C. Chuang, E. Zhang, Y. Wang, G. Hu, M.A. Mushtaq, W. Raza, X. Cai, F. Ciucci, Out-of-plane coordination of iridium single atoms with organic molecules and cobalt–iron hydroxides to boost oxygen evolution reaction, Nat. Nanotechnol., 20, 57–66 (2025). [CrossRef]

- S. Sung, T.S. Mayadevi, K. Min, J. Lee, J.E. Chae, T-H. Kim, Crosslinked PPO-based anion exchange membranes: The effect of crystallinity versus hydrophilicity by oxygen-containing crosslinker chain length, J. Membrane Science, 2021, 619: 118774. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, Y. Guo, Z. Zhang, X. Zhang, Q. Ji, H. Zhang, Z. Song, D. Liu, J. Zeng, C. Chuang, E. Zhang, Y. Wang, G. Hu, M.A. Mushtaq, W. Raza, X. Cai, F. Ciucci, Electrocatalytic activity, phase kinetics, spectroscopic advancements, and photocorrosion behaviour in tantalum nitride phases, Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 57–66 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Emin, A. Ding, M. Mateen, S.T. Muntaha, A. Parkash, S. Ali, Q. Li, An efficient electrodeposition approach for preparing CoMn-hydroxide on nickel foam as high-performance electrodes in aqueous hybrid supercapacitors, Fuel, 381 (2025) 133335. [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sana, H. Pu, Multi-block poly(ether sulfone) for anion exchange membranes with long side chains densely terminated by piperidinium, J. Membrane Science, 2020, 615: 118537. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Mousavi, M. Mehrpooya, Fabrication of copper centered metal organic framework and nitrogen, sulfur dual doped graphene oxide composite as a novel electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction, Energy, 214, 2021, 119053. [CrossRef]

- G. Ma, J. Ye, M. Qin, T. Sun, W. Tan, Z. Fan, L. Huang, X. Xin, Mn-doped NiCoP nanopin arrays as high-performance bifunctional electrocatalysts for sustainable hydrogen production via overall water splitting, Nano Energy, 115, 2023, 108679. [CrossRef]

- E.J. Park, S.M. Michael, R. HibbsCy, H. Fujimoto, K-D. Kreuer, Y.S. Kim, Alkaline stability of quaternized Diels-Alder polyphenylenes. Macromolecules, 2019, 52(14): 5419-5428. [CrossRef]

- B.S. Anupam, D. Sharma, Tu. Jana, Alkaline anion exchange membrane from alkylated polybenzimidazole, ACS Applied Energy Materials, 2021, 4(9): 9792-9805. [CrossRef]

- N. Chen, H.H. Wang, S.P. Kim, H.M. Kim, W.H. Lee, C. Hu, J.Y. Bae, E.S. Sim, Y-C. Chung, J-H. Jang, S.J. Yoo, Y. Zhuang, Y.M. Lee, Poly (fluorenyl arylpiperidinium) membranes and ionomers for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Commun., 2021, 12: 2367. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, Y. Huang, L. Liu, Q. Ju, X. Zhou, X. Qiao, Z. Zheng, N. Li, Piperidinium functionalized arylether-free polyaromatics as anion exchange membrane for water electrolysers: Performance and durability. J. Membrane Science, 2021, 621: 118964. [CrossRef]

| Comparison terms | Alkaline electrolytic water for hydrogen production | Hydrogen production by electrolysis of water with proton exchange membrane | Hydrogen production by water electrolysis with anion exchange membrane |

|---|---|---|---|

| diaphragms | Porous diaphragms (e.g., PPS woven) | Proton exchange membranes (e.g., Nafion) | Anion exchange membrane |

| Cathodes | NiMo alloy | Platinum group metals | transition metal |

| Anodes | NiCo alloy | RuOx, IrOx | transition metal |

| Polarized | Stainless Steel Ni Plated | Graphite or titanium sheet | Nickel or stainless steel plate |

| Electrolytes | KOH solution | Purified water | Alkaline solution or purified water |

| Current density/(A/cm2) | < 0.5 | 1~2 | 1~2 |

| Operating temperature/°C | 60~90 | 50~90 | 40~80 |

| Gas purity | > 99.5% | > 99.99% | > 99.99% |

| Lifespan/h | ≈100000 | <10000 | < 2000 |

| Costs | lower | High | − |

| Technology maturity | Maturity | Small-scale commercialization | Under development |

| Vantage | High technological maturity; low cost using non-precious metal catalysts | High energy efficiency; high gas purity; high current density ;rapid response | High energy efficiency; fast response; low costnon-precious metal catalysts; high gas purity |

| Drawbacks | Low energy efficiency; low current density; low gaspurity; poor responsiveness | Precious metal catalysts and Nafion membranes, high cost; poor stability | Low technological. maturity; short lifespan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).