Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. MPs in the Environment

3. Biological Effects of Polystyrene Particles (PS-MPand PS-NP)

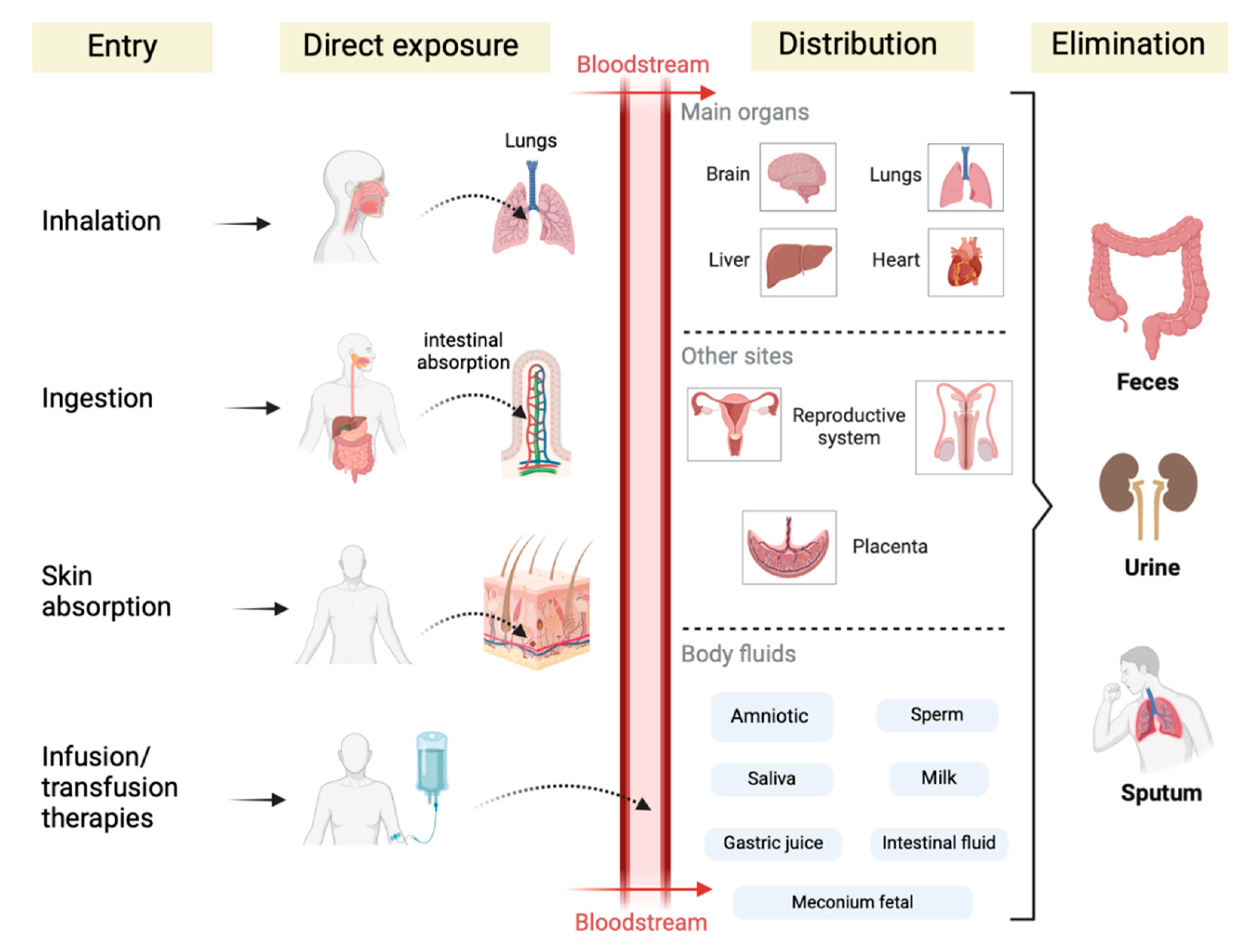

4. Occurrence of MNPs in the Bloodstream, Reproductive System and Gastrointestinal Tract

5. Occurrence of MPs in the Respiratory Tract via Inhalation

6. MP Occurrence and the Cardiovascular System Treats

7. MPs and the Development of Cancer

8. Elimination and Clearance of MNPs

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeb A, Liu W, Ali N, Shi R, Wang J, Li J, Yin C, Liu J, Yu M, Liu J. Microplastic pollution in terrestrial ecosystems: Global implications and sustainable solutions. J Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132636.

- Thushari GGN, Senevirathna JDM. Plastic pollution in the marine environment. Heliyon 2020, 6(8), e04709.

- Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782.

- Li Y, Tao L, Wang Q, Wang F, Li G, Song M. Potential Health Impact of Microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects. Environ. Health 2023, 1, 249–257.

- Rahman A, Sarkar A, Yadav O, Achari G, Slobodnik J. Potential human health risks due to environmental exposure to nano- and microplastics and knowledge gaps: A scoping review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 757, 143872.

- Prinz N, Korez Š. Understanding How Microplastics Affect Marine Biota on the Cellular Level Is Important for Assessing Ecosystem Function: A Review. In: Jungblut S, Liebich V, Bode-Dalby M. (eds) YOUMARES 9 - The Oceans: Our Research, Our Future, Cham: Springer; 2020. 101-120 p.

- Proki MD, Radovanovi TB, Gavri JP, Faggio C. Ecotoxicological effects of microplastics: Examination of biomarkers, current state and future perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 111, 37–46.

- Ferreira PG, da Silva FC, Ferreira VF. The Importance of Chemistry for the Circular Economy. Rev. Virtual Quim. 2017, 9, 452–473.

- Zhong Z, Huang W, Yin Y, Wang S, Chen L, Chen Z, Wang J, Li L, Khalid M, Hu M, Wang Y. Tris(1-chloro-2-propyl)phosphate enhances the adverse effects of biodegradable polylatic acid microplastics on the mussel Mytilus coruscus. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 359, 124741.

- Landrigan, PJ, Raps H, Cropper M, Bald C, Brunner M, Canonizado EM, Charles D, Chiles TC, Donohue MJ, Enck J, Fenichel P, Fleming LE, Ferrier-Pages C, Fordham R, Gozt A, Griffin C, Hahn ME, Harayanto B, Hixson R, Ianelli H, James BD, Kumar P, Laborde A, Law KL, Martin K, Mu J, Mulders Y, Mustapha A, Niu J, Pahal S, Park Y, Pedrotti ML, Pitt JA, Ruchirawat M, Seewoo BJ, Spring M, Stegeman JJ, Suk W, Symeonides C, Takada H, Thompson RC, Vicini A, Wang Z, Whitiman E, Wirth D, Wolff M, Yousuf AK, Dunlop S. The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health. Annals of Global Health 2023, 89 (1), 71.

- Davos AM24 – World Economic Forum. Landing an Ambitious Global Plastics Treaty. https://www.weforum.org/events/world-economic-forum-annual-meeting-2024/sessions/landing-an-ambitious-global-plastics-treaty/. Accessed December 3, 2024.

- Thompson RC, Olsen Y, Mitchell RP, Davis A, Rowland SJ, John AWG, McGonigle D, Russell AE. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838–838.

- Arthur C, Baker J, Bamford H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/2509. Accessed December 5, 2024.

- Pabortsava K, Lampitt R. High concentrations of plastic hidden beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4073.

- Damaj S, Trad F, Goevert D, Wilkesmann, J. Bridging the Gaps between Microplastics and Human Health. Microplastics 2024, 3, 46–66.

- Wu P, Huang J, Zheng Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y, He F, Chen H, Quan G, Yan J, Li T, Gao B. Environmental occurrences, fate, and impacts of microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109612.

- Akdogan Z, Guven B. Microplastics in the environment: A critical review of current understanding and identification of future research needs. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, Part A, 113011.

- Kumar M, Chen H, Sarsaiya S, Qin S, Liu H, Awasthi MK, Kumar S, Singh L, Zhang Z, Bolan NS, Pandey A, Varjani S, Taherzadeh MJ. Current research trends on micro-and nano-plastics as an emerging threat to global environment: A review J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124967.

- Borah SJ, Gupta AK, Kumar V, Jhajharia P, Singh PP, Kumar R. DubeThe Peril of Plastics: Atmospheric Microplastics in Outdoor, Indoor, and Remote Environments. Sustain. Chem. 2024, 5, 149–162.

- Albazoni HJ, Al-Haidarey MJS, Nasir AS. A Review of Microplastic Pollution: Harmful Effect on Environment and Animals, Remediation Strategies. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 140–157.

- Zhang S, Wang J, Yan P, Hao X, Xu B, Wang W, Aurangzeib M. Non-biodegradable microplastics in soils: a brief review and challenge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124525.

- Nafea TH, Al-Maliki AJ, Al-Tameemi IM. Sources, fate, effects, and analysis of microplastic in wastewater treatment plants: A review. Environ. Eng. Res. 2024, 29, 230040.

- Bodor A, Feigl G, Kolossa B, Mészáros E, Laczi K, Kovács E, Perei K, Rákhely G. Soils in distress: The impacts and ecological risks of (micro)plastic pollution in the terrestrial environment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115807.

- Corradini F, Meza P, Eguiluz R, Casado F, Huerta-Lwanga E, Geissen, V. Evidence of Microplastic Accumulation in Agricultural Soils from Sewage Sludge Disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 411–420.

- Weithmann N, Möller JN, Loder MGJ, Piehl S, Laforsch C, Freitag R. Organic Fertilizer as a Vehicle for the Entry of Microplastic into the Environment. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaap8060.

- Tariq M, Iqbal B, Khan I, Khan AR, Jho EH, Salam A, Zhou H, Zhao X, Li G, Du D. Microplastic contamination in the agricultural soil-mitigation strategies, heavy metals contamination, and impact on human health: a review. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 65.

- Rillig M, Lehmann A. Microplastic in terrestrial ecosystems. Science 2020, 368, 1430–1431.

- Sacco VA, Zuanazzi NR, Selinger A, Costa JHA, Lemunie ÉS, Comelli CL, Abilhoa V, Sousa FC, Fávaro LF, Mendoza LMR, Ghisi NC, Delariva RL. What are the global patterns of microplastic ingestion by fish? A scientometric review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 350, 123972.

- Van Cauwenberghe L, Janssen CR. Microplastics in Bivalves Cultured for Human Consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 65–70.

- Brown E, MacDonald A, Allen S, Allen D. The potential for a plastic recycling facility to release microplastic pollution and possible filtration remediation effectiveness. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 10, 100309.

- Li P, Liu J. Micro(nano)plastics in the Human Body: Sources, Occurrences, Fates, and Health Risks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3065–3078.

- Eze CG, Nwankwo CE, Dey S, Sundaramurthy S, Okeke ES. Food chain microplastics contamination and impact on human health: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1889–1927.

- Al Mamun A, Prasetya TAE, Dewi IR, Ahmad M. Microplastics in human food chains: Food becoming a threat to health safety. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, Part 1, 159834.

- Hu M, Palić D. Micro- and nano-plastics activation of oxidative and inflammatory adverse outcome pathways. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101620.

- Zhao X, You F. Microplastic Human Dietary Uptake from 1990 to 2018 Grew across 109 Major Developing and Industrialized Countries but Can Be Halved by Plastic Debris Removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 8709–8723.

- Fleury JB, Baulin VA. Synergistic Effects of Microplastics and Marine Pollutants on the Destabilization of Lipid Bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 36, 8753–8761.

- Maurizi L, Simon-Sánchez L, Vianllo A, Nielsen AH, Vollertsen J. Every breath you take: high concentration of breathable microplastics in indoor environments. Chemosphere 2024, 20, 142553.

- Xu L, Bai X, Li K, Zhang G, Zhang M, Hu M, Huang Y. Human Exposure to Ambient Atmospheric Microplastics in a Megacity: Spatiotemporal Variation and Associated Microorganism-Related Health Risk. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3702–3713.

- Toussaint B, Raffael B, Angers-Loustau A, Gilliland D, Kestens V, Petrillo M, Rio-Echevarria IM, Van den Eede G. Review of micro- and nanoplastic contamination in the food chain. Food Addit. Contam.: Part A 2019, 36, 639–673.

- Prata J, Costa J, Lopes I, Duarte A, Rocha-Santos T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 702, 134455.

- Hore M, Bhattacharyya S, Roy S, Sarkar D, Biswas JK. Human Exposure to Dietary Microplastics and Health Risk: A Comprehensive Review. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 262, article number 14.

- Osman AI, Hosny M, Eltaweil AS, Omar S, Elgarahy AM, Farghali M, Yap PS, Wu YS, Nagandran S, Batumalaie K, Gopinath SCB, John, OD, Sekar M, Saikia T, Karunanithi P, Hatta MHM, Akinyede KA. Microplastic sources, formation, toxicity and remediation: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2129–2169.

- Bhutto SUA, You X. Spatial distribution of microplastics in Chinese freshwater ecosystem and impacts on food webs. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118494.

- Peters CA, Thomas PA, Rieper KB, Bratton SP. Foraging preferences influence microplastic ingestion by six marine fish species from the Texas Gulf Coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira CWS, Corrêa CS, Smith WS. Food ecology and presence of microplastic in the stomach content of neotropical fish in an urban river of the upper Paraná River Basin. Rev. Ambient. Água 2020, 15, e255.

- Pegado TSS, Schmid K, Winemiller KO, Chelazzi D, Cincinelli A, Dei L, Giarrizzo T. First evidence of microplastic ingestion by fishes from the Amazon River estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 814–821.

- Kutralam-Muniasamy G, Shruti VC, Pérez-Guevara F, Roy PD. Microplastic diagnostics in humans: “The 3Ps” Progress, problems, and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159164.

- Sharma P, Sharma P, Abhishek K. Sampling, separation, and characterization methodology for quantification of microplastic from the environment. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 14, 100416.

- Koelmans AA, Mohamed Nor NH, Hermsen E, Kooi M, Mintenig SM, De France J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 15, 410–422.

- Koelmans AA, Redondo-Hasselerharm PE, Nor NHM, de Ruijter VN, Mintenig SM, Kooi M. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 138–152.

- U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Microplastics Research. https://www.epa.gov/water-research/microplastics-research. Accessed , 2024. 20 December.

- Cox KD, Covernton GA, Davies HL, Dower JF, Juanes F, Dudas SE. Human consumption of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074.

- Qiao R, Sheng C, Lu Y, Zhang Y, Ren H, Lemos B. Microplastics induce intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and disorders of metabolome and microbiome in zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 246–253.

- Rahman L, Williams A, Wu D, Halappanavar S. Polyethylene Terephthalate Microplastics Generated from Disposable Water Bottles Induce Interferon Signaling Pathways in Mouse Lung Epithelial Cells. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1287.

- Cesarini G, Secco S, Taurozzi D, Venditti I, Battocchio C, Marcheggiani S, Mancini L, Fratoddi I, Scalici M. Puccinelli, C. Teratogenic effects of environmental concentration of plastic particles on freshwater organisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165564.

- Fu H, Zhu L, Chen L, Zhang L, Mao L, Wu C, Chang Y, Jiang J, Jiang H, Liu X. Metabolomics and microbiomics revealed the combined effects of different-sized polystyrene microplastics and imidacloprid on earthworm intestinal health and function. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 124799.

- Vincoff S, Schleupner B, Santos J, Morrison M, Zhang N, Dunphy-Daly MM, Eward WC, Armstrong AJ, Diana Z, Somarelli JA. The Known and Unknown: Investigating the Carcinogenic Potential of Plastic Additives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10445–10457.

- World Health Organization. IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/. Accessed December 28, 2024.

- Busch M, Bredeck G, Kämpfer A, Schins R. Investigations of acute effects of polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride micro- and nanoplastics in an advanced in vitro triple culture model of the healthy and inflamed intestine. Environ. Res. 2020, 110536.

- Hesler M, Aengenheister L, Ellinger B, Drexel R, Straskraba S, Jost C, Wagner S, Meier F, Briesen H, Büchel C, Wick P, Buerki-Thurnherr T, Kohl Y. Multi-endpoint toxicological assessment of polystyrene nano- and microparticles in different biological models in vitro. Toxicol. in Vitro 2019, 104610.

- Kik K, Bukowska B, Sicińska P. Polystyrene nanoparticles: Sources, occurrence in the environment, distribution in tissues, accumulation and toxicity to various organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114297.

- Wang X, Zheng H, Zhao J, Luo X, Wang Z, Xing B. Photodegradation Elevated the Toxicity of Polystyrene Microplastics to Grouper (Epinephelus moara) through Disrupting Hepatic Lipid Homeostasis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54 (10), 6202-6212.

- Li Y, Xu G, Wang J, Yu Y. Freeze-thaw aging increases the toxicity of microplastics to earthworms and enriches pollutant-degrading microbial genera. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135651.

- Liu C, Zong C, Chen S, Chu J, Yang Y, Pan Y, Yuan B, Zhang H. Machine learning-driven QSAR models for predicting the cytotoxicity of five common Microplastics. Toxicol. 2024, 508, 153918.

- Jones LR, Wright SJ, Gant TW. A critical review of microplastics toxicity and potential adverse outcome pathway in human gastrointestinal tract following oral exposure. Toxicol. Lett. 2023, 385, 51–60.

- Awet T, Kohl Y, Meier F, Straskraba S, Grün A, Ruf T, Jost C, Drexel R, Tunç E, Emmerling C. Effects of polystyrene nanoparticles on the microbiota and functional diversity of enzymes in soil. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30.

- Dong C, Chen C, Chen Y, Chen H, Lee J, Lin C. Polystyrene microplastic particles: In vitro pulmonary toxicity assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 121575.

- Danso IK, Woo JH, Lee K. Pulmonary toxicity of polystyrene, polypropylene, and polyvinyl chloride microplastics in mice. Mol. 2022, 27, 7926.

- Cao J, Xu R, Geng Y, Xu S, Guo M. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics triggers lung injury via targeting toll-like receptor 2 and activation of the NF-kappaB signal in mice. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 320, 121068.

- Wu Y, Yao Y, Bai H, Shimizu K, Li R, Zhang C. Investigation of pulmonary toxicity evaluation on mice exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics: The potential protective role of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158851.

- Li X, Zhang T, Lv W, Wang H, Chen H, Xu Q, Cai H, Dai J. Intratracheal administration of polystyrene microplastics induces pulmonary fibrosis by activating oxidative stress and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 232, 113238.

- Kuroiwa M, Yamaguchi SI, Kato Y, Hori A, Toyoura S, Nakahara M, Morimoto N, Nakayama M. Tim4, a macrophage receptor for apoptotic cells, binds polystyrene microplastics via aromatic-aromatic interactions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162586.

- Garcia MM, Romero AS, Merkley SD, Meyer-Hagen JL, Forbes C, El Hayek E, Sciezka DP, Templeton R, Gonzalez-Estrella J, Jin Y, Gu H, Benavidez A, Hunter RP, Lucas S, Herbert G, Kim KJ, Cui JY, Gullapalli RR, In JG, Campen MJ, Castillo EF. In vivo tissue distribution of polystyrene or mixed polymer microspheres and metabolomic analysis after oral exposure in mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132(4), 47005.

- Zhou B, Wei Y, Chen L, Zhang A, Liang T, Low JH, Liu Z, He S, Guo Z, Xie J. Microplastics exposure disrupts nephrogenesis and induces renal toxicity in human iPSC-derived kidney organoids. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 360, 124645.

- Wen Y, Cai J, Zhang H, Li Y, Yu M, Liu J, Han F. The Potential Mechanisms Involved in the Disruption of Spermatogenesis in Mice by Nanoplastics and Microplastics. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1714.

- Zhu L, Ma M, Sun X, Wu Z, Yu Y, Kang Y, Liu Z, Xu Q, An L. Microplastics Entry into the Blood by Infusion Therapy: Few but a Direct Pathway. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emecheta EE, Pfohl PM, Wohlleben W, Haase A, Roloff A. Desorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Microplastics in Human Gastrointestinal Fluid Simulants-Implications for Exposure Assessment. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 24281–24290.

- Halfar, J. ,Čabanová K, Vávra K, Delongová P, Motyka O, Špaček R, Kukutschová J, Šimetka O, Heviánková S. Microplastics and additives in patients with preterm birth: The first evidence of their presence in both human amniotic fluid and placenta. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140301. [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Ehrlich L, Henrich W, Koeppel S, Lomako I, Schwabl P, LiebmannB. Detection of Microplastic in Human Placenta and Meconium in a Clinical Setting. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 921.

- Zhu, L, Zhu J, Zuo R, Xu Q, Qian Y, AN L. Identification of microplastics in human placenta using laser direct infrared spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, Part 1,159060. [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa A, Notarstefano V, Svelato A, Belloni, A, Gioacchini G, Blondeel C, Zucchelli E, De Luca C, D’Avino S, Gulotta A, Carnevali O, Giorgini E. Raman Microspectroscopy Detection and Characterisation of Microplastics in Human Breastmilk. Polymers 2022, 14, 2700.

- Qin X, Cao M, Peng T, Shan H, Lian W, Yu Y, Shui G, Li R. Features, Potential Invasion Pathways, and Reproductive Health Risks of Microplastics Detected in Human Uterus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10482–10493.

- Yang Y, Xie E, Du Z, Peng Z, Han Z, Li L, Zhao R, Qin Y, Xue M, Li F, Hua K, Yang X. Detection of Various Microplastics in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 10911–10918.

- Horvatits T, Tamminga M, Liu B, Sebode M, Carambia A, Fischer L, Püschel K, Huber S, Fischer EK. Microplastics detected in cirrhotic liver tissue. EBioMedicine. 2022, 82, 104147.

- Huang C, Li B, Xu K, Liu D, Hu J, Yang Y, Nie H, Fan L, Zhu W. Decline in semen quality among 30,636 young Chinese men from 2001 to 2015. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 83–88.

- Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, Mongioì LM, La Vignera S, Calogero AE. Molecular Biology of Spermatogenesis: Novel Targets of Apparently Idiopathic Male Infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1728.

- Hu CJ, Garcia MA, Nihart A, Liu R, Yin L, Adolphi N, Gallego DF, Kang H, Campen MJ, Yu X. Microplastic presence in dog and human testis and its potential association with sperm count and weights of testis and epididymis. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 1–6.

- Ibrahim YS, Anuar ST, Azmi AA, Khalik WMAWM, Lehata S, Hamzah SR, Ismail D, Ma ZF, Dzulkarnaen A, Zakaria Z, Mustaffa N, Sharif SET, Lee YY. Detection of microplastics in human colectomy specimens. JGH Open. 2021, 5, 116–121.

- Cetin M, Miloglu FD, Baygutalp NK, Ceylan O, Yildirim S, Eser G, Gul Hİ. Higher number of microplastics in tumoral colon tissues from patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 639–646.

- Zheng Y, Xu S, Liu J, Liu Z. The effects of micro- and nanoplastic on the central nervous system: A New Threat to Humanity? Toxicol. 2024, 504, 153799.

- Prüst M, Meijer J, Westerink RHS. The plastic brain: neurotoxicity of micro- and nanoplastics. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 24.

- Savuca A, Curpan AS, Hritcu LD, Buzenchi Proca TM, Balmus IM, Lungu PF, Jijie R, Nicoara MN, Ciobica AS, Solcan G, Solcan C. Do Microplastics Have Neurological Implications in Relation to Schizophrenia Zebrafish Models? A Brain Immunohistochemistry, Neurotoxicity Assessment, and Oxidative Stress Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8331.

- Xu C, Zhang B, Gu C, Shen C, Yin S, Aamir M, Li F. Are we underestimating the sources of microplastic pollution in terrestrial environment? J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123228.

- Dris R Gasperi J, Saad M, Mirande C, Tassin B. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 104 (1-2), 290-293.

- Chen C, Liu F, Quan S, Chen L, Shen A, Jiao A, Qi H, Yu G. Microplastics in the Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid of Chinese Children: Associations with Age, City Development, and Disease Features. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57 (34), 12594-12601.

- Lu K, Zhan D, Fang Y, Li L, Chen G, Chen S, Wang L. Microplastics, potential threat to patients with lung diseases. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 958414. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman K, Hare J, Khamis Z, Hua T, Sang Q. Exposure of Human Lung Cells to Polystyrene Microplastics Significantly Retards Cell Proliferation and Triggers Morphological Changes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34(4), 1069–1081.

- Chen Q, Gao J, Yu H, Su H, Yang Y, Cao Y, Zhang Q, Ren Y, Hollert H, Shi H, Chen C, Liu H. An emerging role of microplastics in the etiology of lung ground glass nodules. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 34, 1–15.

- Bishop C, Yan K, Nguyen W, Rawle D, Tang B, Larcher T, Suhrbier A. Microplastics dysregulate innate immunity in the SARS-CoV-2 infected lung. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1382655.

- Amato-Lourenço L, Carvalho-Oliveira R, Júnior G, Galvão L, Ando R, Mauad T. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126124.

- Qiu L, Lu W, Tu C, Li X, Zhang H, Wang S, Chen M, Zheng X, Wang Z, Lin M, Zhang Y, Zhong C, Li S, Liu Y, Liu J, Zhou Y. Evidence of microplastics in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among never-smokers: A prospective case series. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 2435–44.

- Chen C, Liu F, Quan S, Chen L, Shen A, Jiao A, Qi H, Yu G. Microplastics in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of chinese children: associations with age, city development, and disease features. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 12594–12601.

- Jenner LC, Rotchell JM, Bennett RT, Cowen M, Tentzeris V, Sadofsky LR. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154907.

- Xu X, Goros RA, Dong Z, Meng X, Li G, Chen W, Liu S, Ma J, Zuo YY. Microplastics and Nanoplastics Impair the Biophysical Function of Pulmonary Surfactant by Forming Heteroaggregates at the Alveolar-Capillary Interface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57 (50), 21050-21060.

- Li Y, Shi T, Li X, Sun H, Xia X, Ji X, Zhang J, Liu M, Lin Y, Zhang R, Zheng Y, Tang J. Inhaled tire-wear microplastic particles induced pulmonary fibrotic injury via epithelial cytoskeleton rearrangement. Environ. Int. 2022, 164, 107257.

- Zha H, Xia J, Li S, Lv J, Zhuge A, Tang R, Wang S, Wang K, Chang K, Li L. Airborne polystyrene microplastics and nanoplastics induce nasal and lung microbial dysbiosis in mice. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Han J, Na J, Fang J, Qi C, Lu J, Liu X, Zhou C, Feng J, Zhu W, Liu L, Jiang H, Hua Z, Pan G, Yan L, Sun W, Yang Z. Exposure to microplastics in the upper respiratory tract of indoor and outdoor workers. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136067.

- Lett Z, Hall A, Skidmore S, Alves NJ. Environmental microplastic and nanoplastic: exposure routes and effects on coagulation and the cardiovascular system. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118190.

- Zhu X, Wang C, Duan X, Liang B, Xu EG, Huang Z, Micro- and nanoplastics: A new cardiovascular risk factor? Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107662. [CrossRef]

- Tran DQ, Stelflug N, Hall A, Nallan Chakravarthula T, Alves NJ. Microplastic effects on thrombin-fibrinogen clotting dynamics measured via turbidity and thromboelastography. Tran. Biomol. Ther. 2022, 12, 1864.

- Christodoulides A, Hall A, Alves NJ. Exploring microplastic impact on whole blood clotting dynamics utilizing thromboelastography. Front. Public Health. 2023, 11, 1215817.

- Zhu M, Li P, Xu T, Zhang G, Xu Z, Wang X, Zhao L, Yang H. Combined exposure to lead and microplastics increased risk of glucose metabolism in mice via the Nrf2 / NF-κB pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2024, 39, 2502–2511.

- Bhatnagar, A. Cardiovascular pathophysiology of environmental pollutants. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286: H479-H485.

- Bhatnagar, A. Studying Mechanistic Links Between Pollution and Heart Disease. Environ.l Cardiol. 2006, 99, 692–705. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Wang C, Yang Y, Du Z, Li L, Zhang M, Ni S, Yue Z, Yang K, Wang Y, Li X, Yang Y, Qin Y, Li J, Yang Y, Zhang M. Microplastics in three types of human arteries detected by pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133855.

- Marfella R, Paolisso G, Prattichizzo F, Sardu C, Fulgenzi G, Graciotti L, Spadoni T, D’Onofrio N, Scisciola L, La Grotta R, Frigé C, Pellegrini V, Minicinò M, Siniscalchi M, Spinetti F, Vigliotti G, Vecchione C, Carrizzo A, Accarino G, Squillante A, Spaziano G, Mirra D, Esposito R, Altieri S, Falco G, Fenti A, Galoppo S, Canzano S, Sasso FC, Matacchione G, Olivieri F, Ferraraccio F, Panarese I, Paolisso P, Barbato E, Lubritto C, Balestrieri ML, Mauro C, Caballero AE, Rajagopalan S, Ceriello A, D’Agostino B, Iovino P, Paolisso G. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 900–910.

- Kozlov, M. Landmark study links microplastics to serious health problems. Nature. 2024 Mar 06.

- Guo Q, Deng T, Du Y, Yao W, Tian W, Liao H, Wang Y, Li J, Yan W, Li Y. Impact of DEHP on mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes and reproductive toxicity in ovary. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 282, 116679.

- Xie Y, Feng NX, Huang L, Wu M, Li CX, Zhang F, Huang Y, Cai QY, Xiang L, Li YW, Zhao HM, Mo CH. Improving key gene expression and di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) degrading ability in a novel Pseudochrobactrum sp. XF203 by ribosome engineering. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174207.

- Almeida MC, Machado MR, Costa G,G, Oliveira GAR, Nunes HF, Veloso DFMC, Ishizawa TA, Pereira J, Oliveira TF. Influence of different concentrations of plasticizer diethyl phthalate (DEP) on toxicity of Lactuca sativa seeds, Artemia salina and Zebrafish. Heliyon 2023, 9 (9), e18855.

- Sharma M, Elanjickal A, Mankar J, Krupadam R. Assessment of cancer risk of microplastics enriched with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122994.

- Deng Y, Yan Z, Shen R, Wang M, Huang Y, Ren H, Zhang Y, Lemos B. Microplastics release phthalate esters and cause aggravated adverse effects in the mouse gut. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105916.

- Cheng W, Zhou Y, Xie Y, Li Y, Zhou R, Wang H, Feng Y, Wang Y. Combined effect of polystyrene microplastics and bisphenol A on the human embryonic stem cells-derived liver organoids: The hepatotoxicity and lipid accumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158585.

- Kumar R, Manna C, Padha S, Verma A, Sharma P, Dhar A, Ghosh A, Bhattacharya P. Micro(nano)plastics pollution and human health: How plastics can induce carcinogenesis to humans? Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134267.

- Rawle DJ, Dumenil T, Tang B, Bishop CR, Yan K, Le TT, Suhrbier A. Microplastic consumption induces inflammatory signatures in the colon and prolongs a viral arthritis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 152212.

- Li S, Keenan J, Shaw I, Frizelle F. Cancers 2023, 15(13), 3323.

- Zhao J, Zhang H, Shi L, Jia Y, Sheng H. Detection and quantification of microplastics in various types of human tumor tissues. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116818.

- Liu S, Huang J, Zhang W, Shi L, Yi K, Yu H, Zhang C, Li S, Li J. Microplastics as a vehicle of heavy metals in aquatic environments: A review of adsorption factors, mechanisms, and biological effects. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 302 Part A, 113995.

- Guan J,Qi K, Wang J, Wang W, Wang Z, Lu N, Qu J. Microplastics as an emerging anthropogenic vector of trace metals in freshwater: Significance of biofilms and comparison with natural substrates. Water Res. 2020, 184, 116205.

- Liu S, Shi J, Wang J, Dai Y, Li H, Li J, Liu X, Chen X, Wang Z, Zhang P. Interactions Between Microplastics and Heavy Metals in Aquatic Environments: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12.

- Godoy V, Blázquez G, Calero M, Quesada L, Martín-Lara M. The potential of microplastics as carriers of metals. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255 Part 3, 113363.

- Sun J, Qu H, Ali W, Chen Y, Wang T, Ma Y, Yuan Y, Gu J, Bian J, Liu Z, Zou H. Co-exposure to cadmium and microplastics promotes liver fibrosis through the hemichannels-ATP-P2×7 pathway. Chemophere 2023, 344, 140372.

- Chen Y, Jin H, Ali W, Zhuang T, Sun J, Wang T, Song J, Ma Y, Yuan Y, Bian J, Liu Z, Zou H. Co-exposure of polyvinyl chloride microplastics with cadmium promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in female ducks through oxidative stress and glycolipid accumulation. Poult. Sci. 2024, 104152.

- Cheng W, Chen H, Zhou Y, You Y, Lei D, Li Y, Feng Y, Wang Y. Aged fragmented-polypropylene microplastics induced ageing statues-dependent bioenergetic imbalance and reductive stress: In vivo and liver organoids-based in vitro study. Environ. Int. 2024, 108949.

- Prata, JC. Microplastics and human health: Integrating pharmacokinetics. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl P, Köppel S, Dipl-Ing Königshofer P, Bucsics T, Trauner M, Reiberger T, Liebmann B. Detection of Various Microplastics in Human Stool: A Prospective Case Series. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 453–457.

- Yan Z, Liu Y, Zhang T, Zhang F, Ren H, Zhang Y. Analysis of Microplastics in Human Feces Reveals a Correlation between Fecal Microplastics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Status. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56(1), 414–421.

- Pironti C, Notarstefano V, Ricciardi M, Motta O, Giorgini E, Montano L. First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Urine, a Preliminary Study of Intake in the Human Body. Toxics 2023, 11, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Huang X, Bi R, Guo Q, Yu X, Zeng Q, Huang Z, Liu T, Wu H, Chen Y, Xu J, Wu Y, Guo P. Detection and Analysis of Microplastics in Human Sputum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56(4), 2476–2486.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).