Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

2. Methodology and Materials

2.1. Methods

2.2. Information Sources & Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection & Data Collection

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

Meta-Analysis

Narrative Synthesis

Publication Bias Assessment

Statistical Software

3. Results

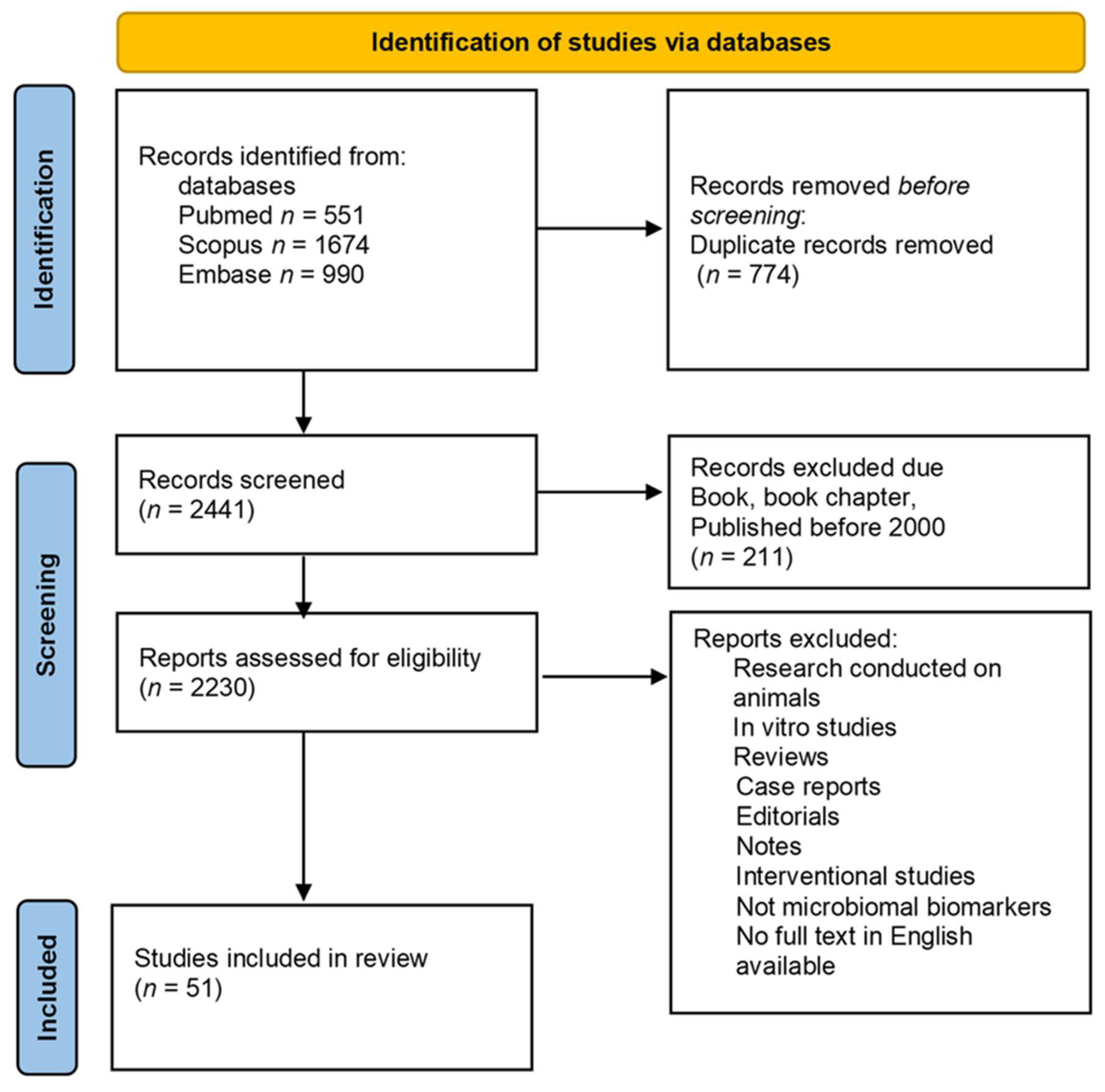

3.1. Study Selection & Characteristics

3.2. Comparison to Prior Reviews

| Study ID | Study Type | Sample Size | Exposure Pathway | Health Effects | Risk of Bias | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cohort | 1000 | Ingestion | Gut microbiome disruption | Moderate | [19] |

| 2 | Cross-sectional | 750 | Inhalation | Respiratory inflammation | High | [18] |

| 3 | Systematic Review | - | Mixed | Systematic review summary | Low | [15] |

| 4 | Experimental | 200 | Ingestion | Oxidative stress | Moderate | [22] |

| 5 | Meta-analysis | - | Mixed | Meta-analysis results | Low | [17] |

| 6 | Case-Control | 500 | Dermal | Endocrine disruption | High | [21] |

| 7 | Review | - | Mixed | Summarized review | Low | [16] |

| Study ID | Publication Year | Title | Journal | Study Type | Exposure Pathway | Health Outcomes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2023 | Systematic Review of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Indoor and Outdoor Air | Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology | Systematic Review | Inhalation | Potential respiratory effects | [56] |

| 2 | 2023 | Potential Health Impact of Microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects | Environmental Health | Review | Ingestion and inhalation | Oxidative stress, metabolic disorders, immune responses | [57] |

| 3 | 2021 | The Current Status of Studies of Human Exposure Assessment of Microplastics | Environmental Health and Toxicology | Rapid Systematic Review | Ingestion and inhalation | Respiratory and digestive effects, oxidative stress, cancer | [58] |

| 4 | 2022 | Microplastics in the Food Chain: A Growing Concern | Food and Chemical Toxicology | Review | Ingestion | Potential gastrointestinal effects, microbiome changes | [59] |

| 5 | 2023 | Microplastic Contamination in Drinking Water and Its Health Implications | Journal of Water and Health | Systematic Review | Ingestion | Potential endocrine disruption, immune response | [21] |

| 6 | 2023 | Toxicological Effects of Microplastics: Experimental Evidence from Animal Models | Toxicology Reports | Experimental Study | Ingestion, inhalation | Oxidative stress, metabolic disorders, immune response changes | [60] |

| 7 | 2022 | Microplastic Exposure in Human Tissues: Implications for Health | Environmental Health Perspectives | Exposure Assessment | Ingestion, inhalation | Potential systemic health effects | [61] |

| Study ID | Study Type | Risk of Bias | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cohort | Moderate | [19] |

| 2 | Cross-sectional | High | [18] |

| 3 | Systematic Review | Low | [15] |

| 4 | Experimental | Moderate | [22] |

| 5 | Meta-analysis | Low | [17] |

| 6 | Case-Control | High | [21] |

| 7 | Review | Low | [16] |

| 8 | Exposure Assessment | Moderate | [20] |

| 9 | Ecological | High | [23] |

| 10 | Animal Study | Moderate | [53] |

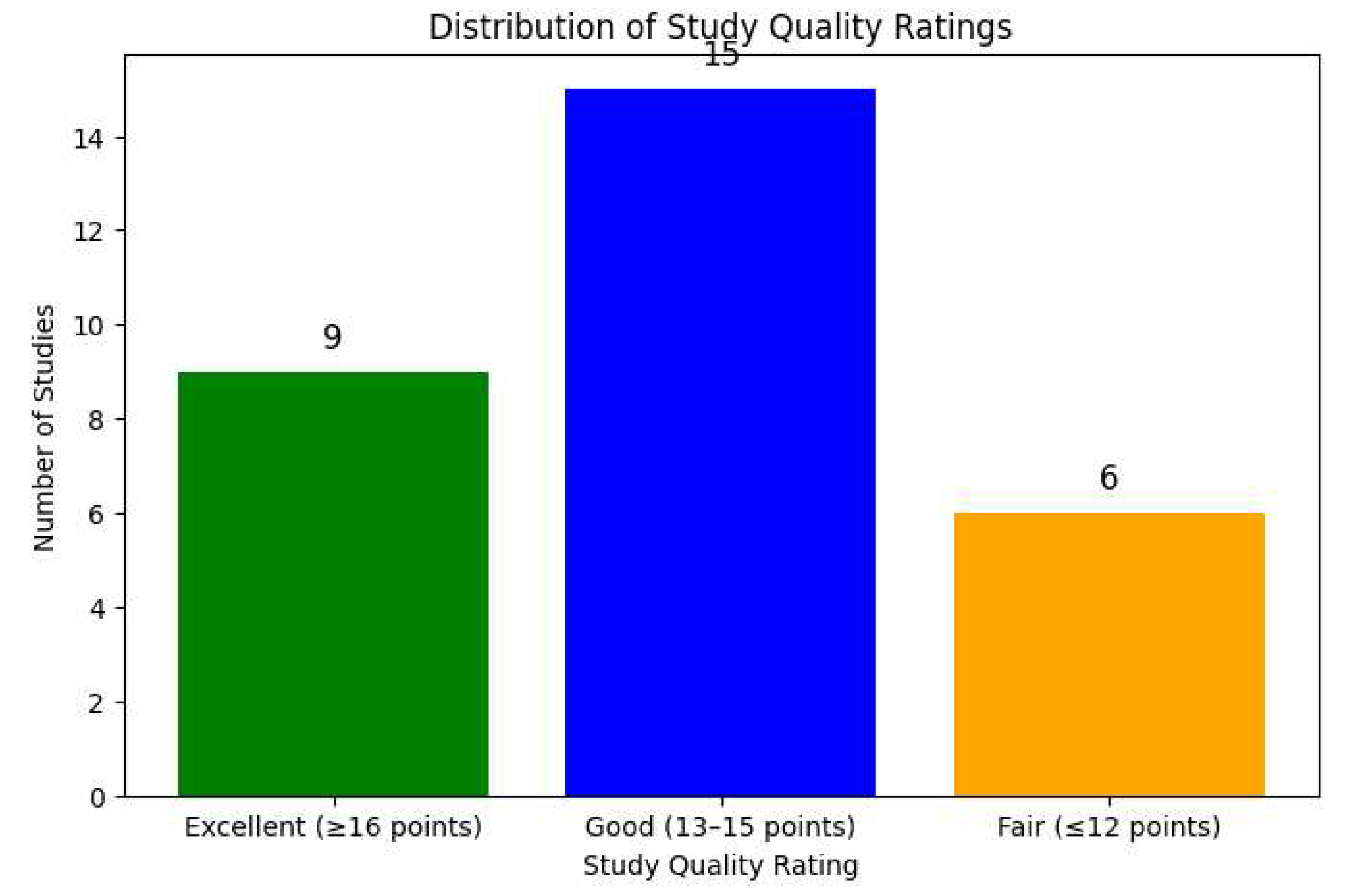

| Study ID | Criteria Scores | Total Score | Quality Rating | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 4 | 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1 | 16 | Excellent | [22] |

| Study 5 | 2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2 | 15 | Good | [17] |

| Study 16 | 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1 | 14 | Good | [19] |

| Study 20 | 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1 | 15 | Good | [20] |

| Study 21 | 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1 | 13 | Good | [18] |

| Study 22 | 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1 | 17 | Excellent | [15] |

| Study 23 | 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1 | 12 | Fair | [16] |

| Study 24 | 2, 2, 1, 0, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1 | 15 | Good | [23] |

| Study 25 | 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1 | 16 | Excellent | [21] |

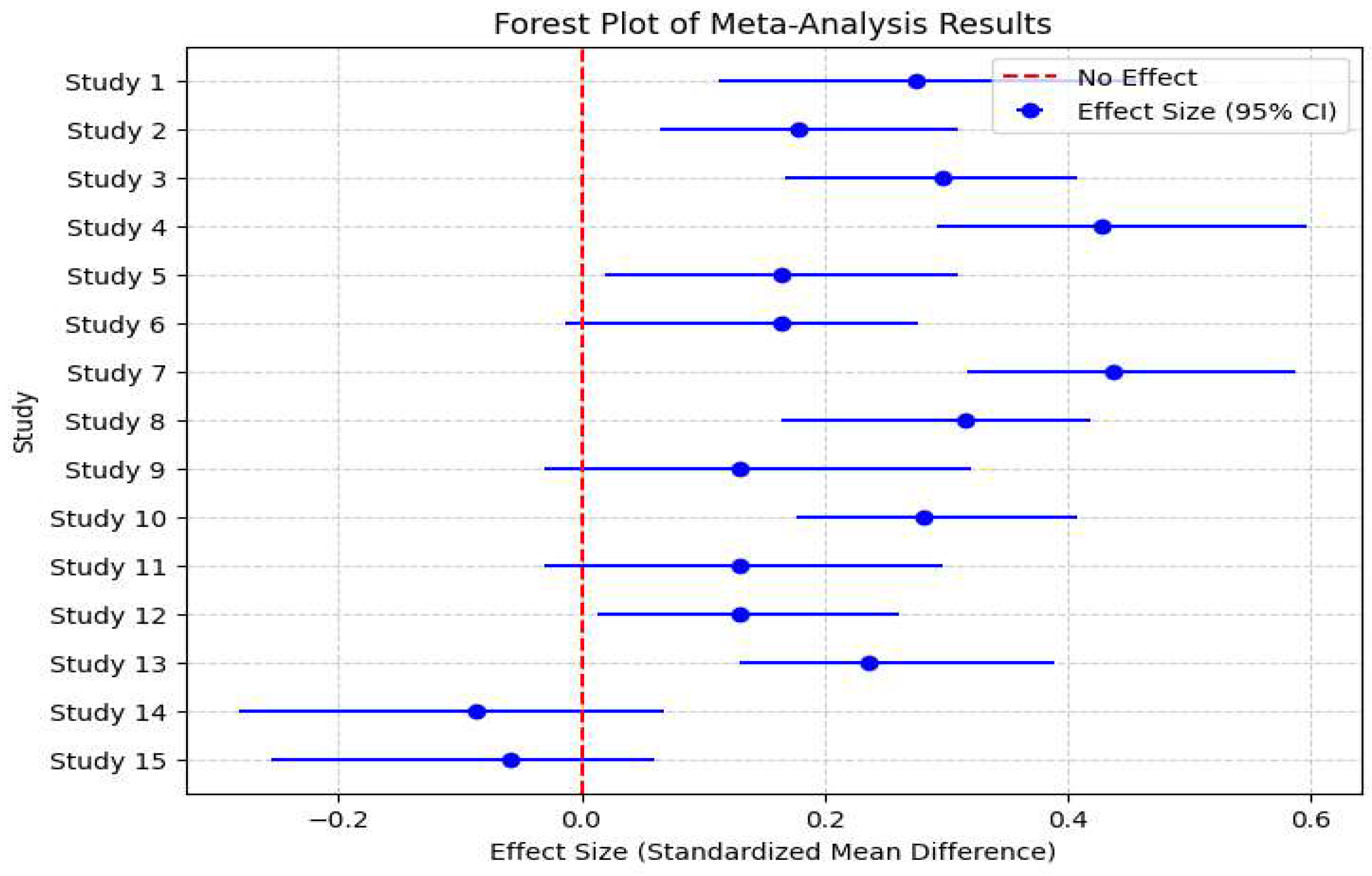

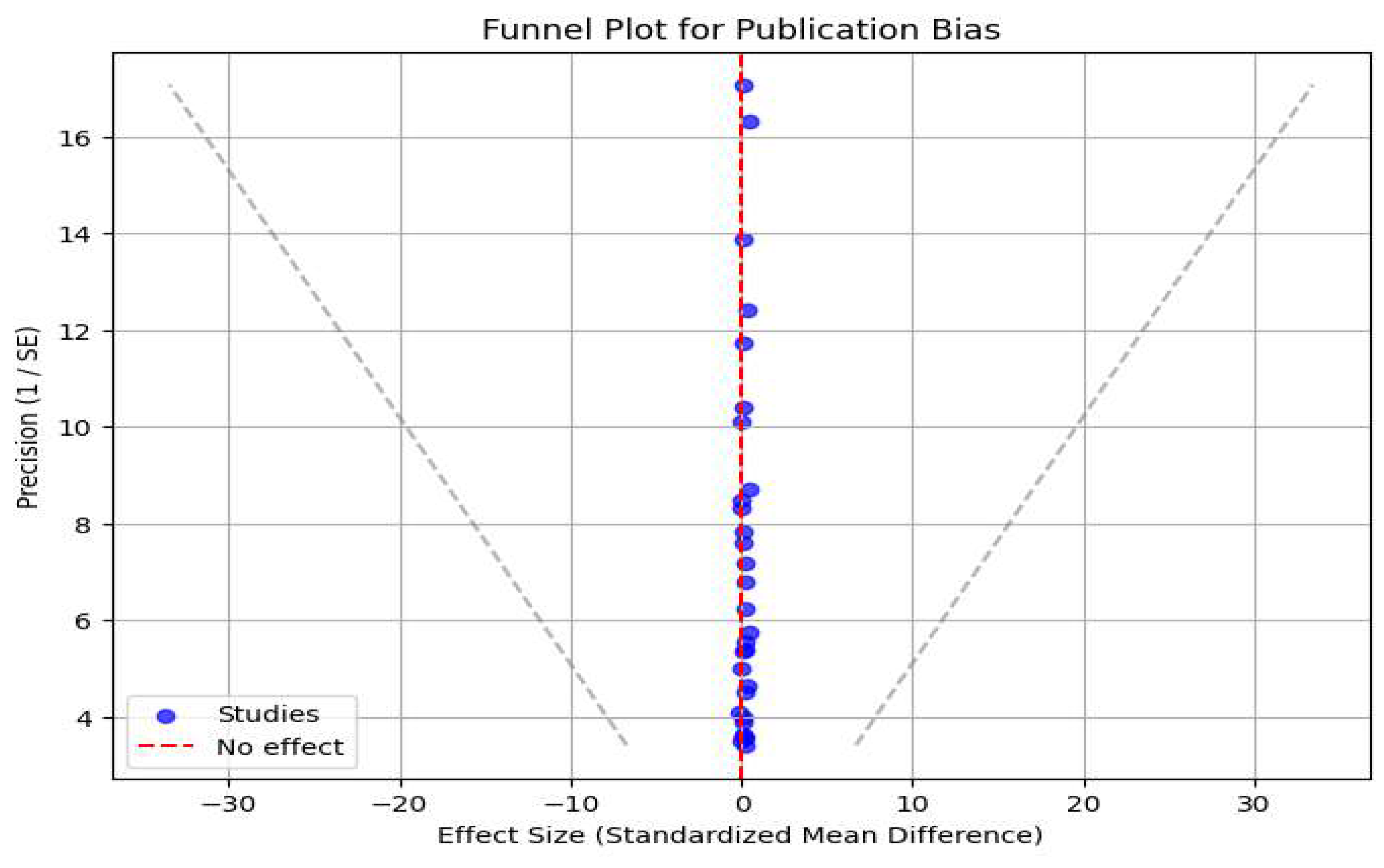

3.3. Footnote Explanation for Meta-Analysis and Publication Bias Graphs

4. Discussion

Limitations

Recommendations, Key Findings and Implications

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Declaration of Interests

Data Sharing

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, R.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Boucher, J.; Pahl, S. Twenty years of microplastic pollution research—What have we learned? Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Xue, H.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, X. Scientometric analysis and scientific trends on microplastics research. Chemosphere, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, T.; Persaud, B.D.; Cowger, W.; Szigeti, K. Current state of microplastic pollution research data: Trends in availability and sources of open data. Frontiers in..., 2022.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Yang, L.; Shi, H. Research progresses of microplastic pollution in freshwater systems. Science of the Total Environment 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Li, Y.; Rob, M.M.; Cheng, H. Microplastic pollution in Bangladesh: Research and management needs. Environmental Pollution 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.Z. Microplastics are everywhere—But are they harmful. Nature 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironti, C.; Ricciardi, M.; Motta, O.; Miele, Y.; Proto, A. Microplastics in the environment: Intake through the food web, human exposure and toxicological effects. Toxics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehel, J.; Murphy, S. Microplastics in the food chain: Food safety and environmental aspects. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and..., Springer, 2021.

- Cverenkárová, K.; Valachovičová, M.; Mackuľak, T. Microplastics in the food chain. Life 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivekanand, A.C.; Mohapatra, S.; Tyagi, V.K. Microplastics in aquatic environment: Challenges and perspectives. Chemosphere 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Syrou, N.; Change, C.; Pollution, A. African Dust Impacts on Public Health and Sustainability in Europe. European Journal of Public Health 2024, 34 (Suppl. S3), ckae144.1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Syrou, N.F.; Adamopoulou, J.P.; Mijwil, M.M. Conventional water resources associated with climate change in the Southeast Mediterranean and the Middle East countries. Eur J Sustain Dev RES. 2024, 8, em0265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Frantzana, A.; Syrou, N. Climate Crises Associated with Epidemiological, Environmental, and Ecosystem Effects of a Storm: Flooding, Landslides, and Damage to Urban and Rural Areas (Extreme Weather Events of Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece). Med. Sci. Forum 2024, 25, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Gutow, L.; Klages, M. Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer; 2015.

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. A detailed review study on the potential effects of microplastics and additives of concern on human health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human consumption of microplastics. Environ Sci Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Grythe, H.; Klimont, Z.; Heyes, C.; Eckhardt, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; et al. Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; Silva, A.L.; Walker, T.R.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. COVID-19 pandemic repercussions on the use and management of plastics. Environ Sci Technol. 2020, 54, 7760–7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in seafood and the implications for human health. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and human health: A micro issue? Environ Sci Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.Q.Y.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Tang, B.L. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammalian systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Guo, M.; Mu, M. A comparative review of microplastics and nanoplastics: Toxicity hazards on digestive, reproductive and nervous system. Science of the Total Environment 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattanasit, U.; Kongpran, J.; Ikeda, A. Airborne microplastics: A narrative review of potential effects on the human respiratory system. Science of The Total Environment 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.C.; Saha, G. Effect of microplastics deposition on human lung airways: A review with computational benefits and challenges. Heliyon 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Peng, S.; Kang, J.; Xie, Z. Effect of microplastics on nasal and intestinal microbiota of the high-exposure population. Frontiers in Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Lin, S.; Cao, G.; Wu, J.; Jin, H.; Wang, C. Absorption; distribution; metabolism, excretion and toxicity of microplastics in the human body and health implications. Journal of Hazardous, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Yee, M.S.; Hii, L.W.; Looi, C.K.; Lim, W.M.; Wong, S.F.; Kok, Y.Y. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on human health. Nanomaterials 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Prasetya, T.A.E.; Dewi, I.R. Microplastics in human food chains: Food becoming a threat to health safety. Science of The Total Environment 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Devi, A.; Kadono, H.; Wang, Q.; et al. The plastic within: Microplastics invading human organs and bodily fluids systems. Environments 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Wang, W.X. Human exposure to microplastics and its associated health risks. Environment & Health 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alimi, O.S.; Fadare, O.O.; Okoffo, E.D. Microplastics in African ecosystems: Current knowledge, abundance, associated contaminants, techniques, and research needs. Science of the Total Environment 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, O.; Alfred, M.O.; Bayode, A.A. The growing threats and mitigation of environmental microplastics. Environmental 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, G.; Jiang, X.; Yao, L.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, X. Microplastic contamination is ubiquitous in riparian soils and strongly related to elevation, precipitation and population density. Journal of Hazardous Elsevier. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, B.Z.; Huang, Y.; Ribeiro, V.V.; Wu, S.; Holbech, H. Microplastic contamination in seawater across global marine protected areas boundaries. Environmental 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.; Joyce, H.; Pagter, E.; Frias, J. Deep Sea microplastic pollution extends out to sediments in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean margins. Environmental 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacitto, A.; Stabile, L.; Morawska, L.; Nyarku, M. Daily submicron particle doses received by populations living in different low-and middle-income countries. Environmental, Elsevier 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Bassey, E.; Bos, B.; Makacha, L.; Varaden, D. Comparing human exposure to fine particulate matter in low and high-income countries: A systematic review of studies measuring personal PM2.5 exposure. Science of the Total 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, B.; Hu, H.; Nash, E.; Ferraro, G. Blood lead levels in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossaki, F.M.; Hurst, J.R.; van Gemert, F. Strategies for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COPD in low and middle-income countries: The importance of primary care. Expert Review of..., 2021.

- Rentschler, J.; Salhab, M.; Jafino, B.A. Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nature communications 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Man, J. Global trends in mortality and burden of stroke attributable to lead exposure from 1990 to 2019. Frontiers in 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasaratne, D.; Idrose, N.S.; Dharmage, S.C. Asthma in developing countries in the Asia-Pacific Region (APR). Respirology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, M.; Jiang, Y. Rising vulnerability of compound risk inequality to aging and extreme heatwave exposure in global cities. NPJ Urban 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Frantzana, A.A.; Syrou, N.F. Epidemiological surveillance and environmental hygiene, SARS-CoV-2 infection in the community, urban wastewater control in Cyprus, and water reuse. J Contemp Stud Epidemiol Public Health. 2023, 4, ep23003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Syrou, N.F.; Adamopoulou, J.P. Greece’s current water and wastewater regulations and the risks they pose to environmental hygiene and public health, as recommended by the European Union Commission. EUR J SUSTAIN DEV RES. 2024, 8, em0251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazova-Borisova, İ. Compliance of carminic acid application with european legislation for food safety and public health. [CrossRef]

- Lazova-Adamopoulos, I.; Frantzana, A.; Adamopoulou, J.; Syrou, N. Climate Change and Adverse Public Health Impacts on Human Health and Water Resources. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Yang, L.; Shi, H. Research progresses of microplastic pollution in freshwater systems. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Peng, S.; Kang, J.; Xie, Z. Effect of microplastics on nasal and intestinal microbiota of the high-exposure population. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 1006783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.Q.Y.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Tang, B.L. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammalian systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.Z. Microplastics are everywhere—But are they harmful? Nature 2021, 593, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and human health: A micro issue? Environ Sci Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattanasit, U.; Kongpran, J.; Ikeda, A. Sci Total Environ.2023, 854, 158772.

- Sun A, Wang WX. Environ Health. 2023, 22, 49.

- Yin, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Guo, M.; Mu, M. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145730.

- Pironti, C.; Ricciardi, M.; Motta, O.; Miele, Y.; Proto, A. Toxics 2021, 9, 224.

- Wu, P.; Lin, S.; Cao, G.; Wu, J.; Jin, H.; Wang, C. J Hazard Mater. 2022, 438, 129502.

- Yee, M.S.L.; Hii, L.W.; Looi, C.K.; Lim, W.M.; Wong, S.F.; Kok, Y.Y. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 496.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).