1. Introduction

Are microplastics the soot of the 21st century? In the Victorian era, the coal-fired factories and mills of the Industrial Revolution led to sooty miasmas covering much of Britain, assisted by the common use of coal in domestic heating. This led to blackened buildings and monuments and increased respiratory problems in the population, as well as to acknowledged increases in accompanying death rates. The great London smog of 1952 killed 4000 people in just a week [

1] - one in 2000 of the population. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that the introduction of coal and, with it, improved heating and industrial systems, saved millions of lives by, for example, reducing winter mortality rates and improving food distribution and public health [

2]. It certainly improved the lives of the population, both in terms of comfort and economics. Asbestos, another dangerous air contaminant, as microfibers, rose to prominence in the building industry in the early 20th century, where it was especially important for thermal insulation and fireproofing [

3]. Its widespread use and the recognition of its danger to human life on inhalation have, however, led to it being banned or restricted in many countries and to waste management challenges [

4]. Both materials, then, led to improvements in the human condition, but the need to reduce damaging emissions of coal [

5] and asbestos [

6] led eventually to controls being introduced, although these are less widespread for asbestos [

7].

In the same way, the development of plastics in the 19th century led to improvements in human life in the mass production of affordable goods and the replacement of animal and plant products like horn, ivory, ebony, etc. [

8]. Bakelite, the first completely synthetic plastic, spread through all parts of society as desirable modern objects. The environmental problems associated with plastics, however, became obvious within one and a half centuries.

Before the Clean Air Act, passed in 1956 in Britain and 1970 in the USA, smoke emissions were 50 times higher than today. They continue to decline. For domestic emissions, levels of inhalable particles in the UK air fell from 41,000 tonnes in 1990 to just above 11,000 tonnes in 1993 (published UK government figures). Microplastics, small plastic particles produced, mainly, by the breakdown of all plastic materials, are included in UK government-published figures for particulate air pollutants, but are not distinguished from other airborne particles. Unlike soot, microplastics originate from a wide variety of sources, including synthetic textiles, tire wear, industrial abrasives, packaging, and degradation of larger plastic debris. They can travel long distances through air and water and accumulate in soils, freshwater, and marine ecosystems.

Microplastics have a particular set of origins, distribution, and properties that make them potentially dangerous to all ecosystems and their inhabitants. They can adsorb harmful chemicals, act as vectors for pathogens, and be ingested by a wide range of organisms, potentially entering the human food chain [

9,

10,

11]. Their range and effects far exceed that of soot and yet, when considering merely airborne microplastics, we may suggest that they have taken the place of soot in today’s world. This change began with the “modern day miracle” that is Plastic. This article highlights both its societal benefits and its emerging environmental and health costs.

2. The History of Plastic

Human societies have been using types of plastic for thousands of years, in the form of rubber, horn and shellac, natural polymers that occur in plants and animals [

12]; artefacts of amber, a natural polymer formed from tree resin, have been found from as far back as the paleolithic period. The mastery of molding, curing, and chemical modification techniques for these natural polymers throughout history prepared the ground for the emergence of artificial plastics. The first true, modern plastic to be made was polystyrene, accidentally discovered by Simon in 1839 [

13]. It was not until the following century (1920), however, that the nature of polystyrene was discovered, when Staudinger published his theories on polymers being composed of long repetitive chains of monomers [

14]. Although there was considerable scientific scepticism about his theories at the time, he was eventually, in 1953, awarded the Nobel prize and it is now accepted that he laid the foundations for plastics chemistry.

Parkesine is considered to be the first man-made plastic, but it was not based on fossil fuels. It is a thermoplastic (pliable at high temperatures) derived from cellulose, and was patented by Parkes in 1856. The 19th century also saw the synthesis of polyvinylchloride (PVC) and polyethylene, but it was not until the 20th century that fully synthetic plastics came on the economic scene, beginning with Bakelite, a phenol-formaldehyde resin. It is a thermoset, able to be molded at high temperatures, but retaining its shape and rigidity once molded and cured. Bakelite Synthetics is still an important chemical company, with headquarters throughout the world. The plastic is used in electrical insulation, automotive parts, household items like tabletops, and jewellery.

The 20th Century brought the explosion of synthetic polymers (modern plastics) made by processing fossil fuels; polystyrene, polyethylene, nylon, teflon, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyester and polypropylene were all being produced industrially by the 1960s. Between 1950 and 1970, global plastic production increased from approximately 1.5 million to over 35 million tons per year [

10], accompanying economic growth and the demand for lightweight, inexpensive, and versatile materials. There are still people alive who were not using plastics as children; compared to life on Earth, plastics have been around for no time at all, but this rapid expansion has already been followed by a widespread understanding of the environmental persistence and toxicity associated with plastics and their additives.

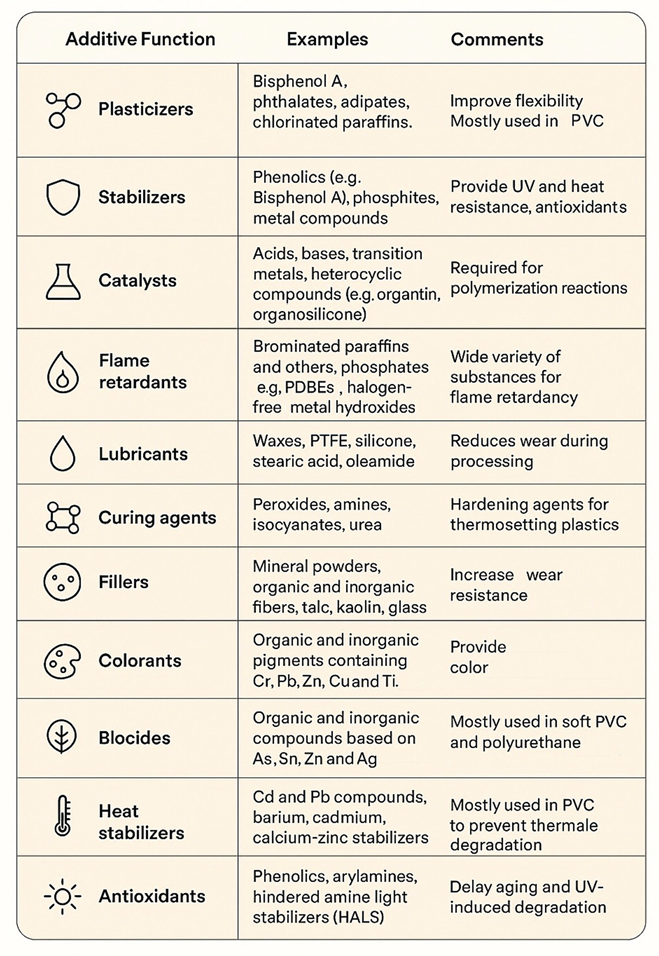

Modern plastics do not only contain the plastic polymer; in order for the product to have the required properties, various chemicals are added to the formulation. These include plasticizers, stabilizers, flame retardants, anti-oxidants, colorants, biocides, fillers, and heat stabilizers (

Table 1); the full range, with a list of 38 additive functions, is given in Pritchard [

15]. Over 4500 additives are in use today; in fact, Monclús et al. [

16] give a list of 16,325 known plastic chemicals, identifying over 4200 of them as chemicals of concern. Many of them belong to chemically persistent and potentially toxic groups, such as phthalates, brominated flame retardants, and heavy-metal-based pigments, which can pose risks to human health and ecosystems. The plasticizer Bisphenol A, for example, is an endocrine-disrupting chemical widely used in many types of plastic that has been added by the European Chemical Agency Member State Committee to the candidate list of substances of very high concern [

17,

18]. It is, however, not possible to fully list the exact chemicals and their concentrations used in today’s plastics because of limited disclosure by the manufacturers [

19]. This lack of transparency is recognized as a global regulatory barrier and a challenge for environmental and health risk assessment, hindering the implementation of effective regulations [

20].

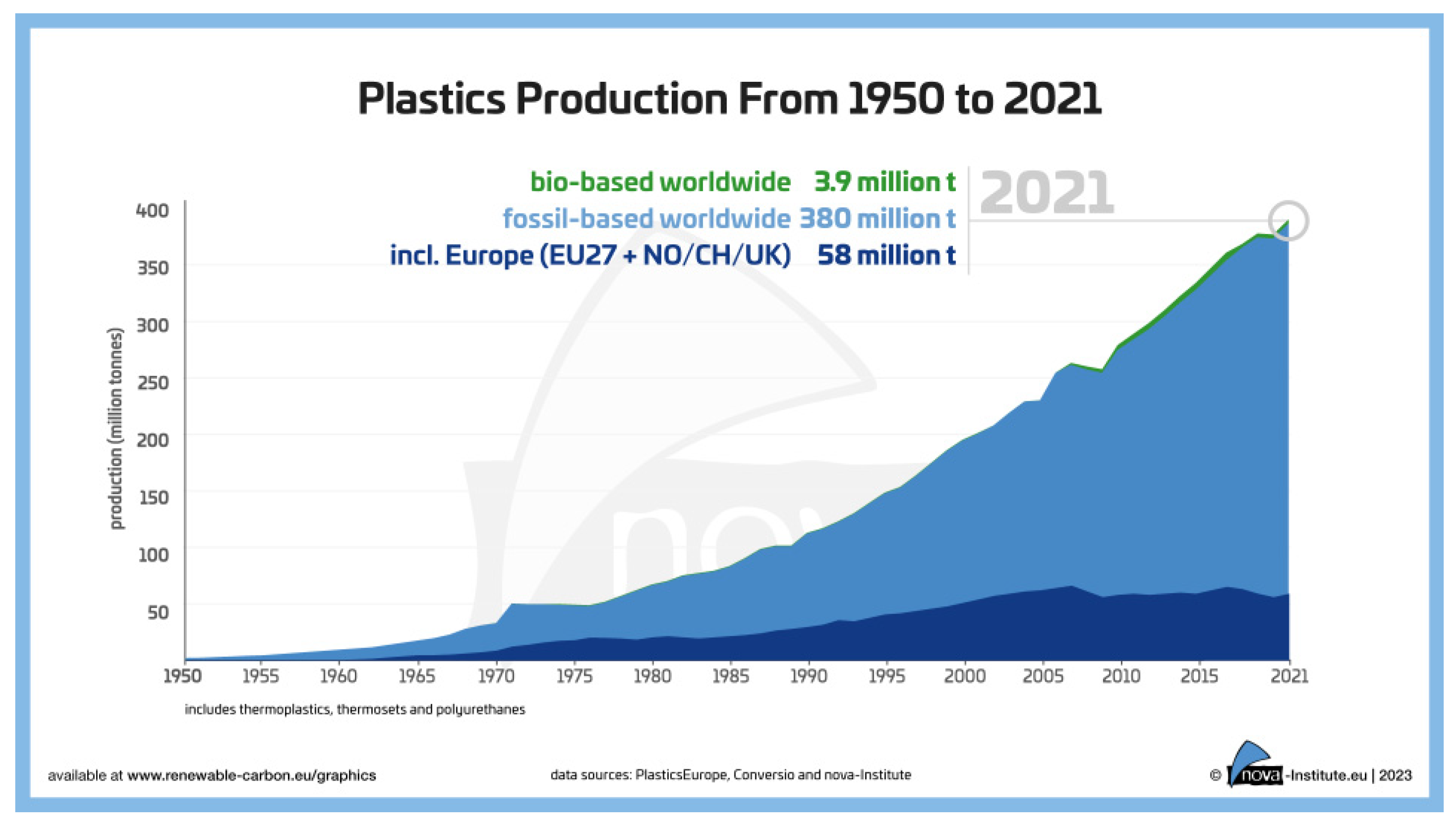

Levels of plastic production have grown exponentially over the last few decades. In 1950 two million tonnes were produced; by 2021 that had risen to 475 million tonnes (

Figure 1). The United Nations Environment Programme [

21] has projected that 1800 million tonnes could be produced by 2050 and, in fact, the annual global production of plastics and plastic waste in 2020 was double that in 2019 [

22]. The major plastics producer is China, followed by North America; these are also the biggest users. Germany, 3rd or 4th on the list, is the major European plastics producer.

3. Uses of Plastic in the Modern World

The versatility, strength, durability, and heat-resistant properties of plastics have lent them to thousands of uses, from sewage pipes to life-saving medical equipment, to clothing. Plastics have improved modern day life in many ways - in healthcare, transportation, food safety, building materials, safety equipment, water availability and safety, not to mention the sheer convenience of having a material that is light, durable, long lasting, versatile and inexpensive compared to many alternatives. The exponential growth of global plastic since 1950 (

Figure 1) indicates the rapid integration of plastics into virtually all aspects of modern life. It is no wonder that the production of plastics has increased so sharply over the last 70+ years. Plastics now make up 50% of car materials and 60% of those used in textiles, the advantages in both cases being their economy, low weight, and durability.

The major industrial uses of plastics, in order of consumption, are discussed in the following paragraphs.

3.1. Plastics in Packaging

Around 40% of all plastics are used in packaging of food and beverages, pharmaceuticals, and wrapping materials for product delivery. Plastic wrapping and vacuum-sealed packaging prevent contamination, extending shelf life and reducing foodborne disease. There are, however, considerable disadvantages associated with such food packaging [

23], the most obvious being the presence and leachability of plastic additives such as bisphenols and phthalates (see

Table 1). Packaging innovations, such as biodegradable and recyclable films, are emerging to reduce environmental impacts [

24]. However, not all alternatives to traditional plastics are equally effective or more sustainable; careful comparison of life cycle assessments must be made, conventional plastics are not always the least environmentally friendly choice [

25].

3.2. Plastics in the Automotive Industry

Plastics compose 50% of the volume of modern automobiles, but only 10% of their weight, indicating immediately the importance of these lightweight materials to vehicle performance. They are used in the vehicle interior, fuel system and electrical components, as well as exterior parts [

26]. They compose important safety features like seatbelts and airbags. and plastic helmets are important safety items for bikes. Additionally, the contribution of plastics to vehicle fuel efficiency by reducing weight indirectly lowers greenhouse gas emissions.

3.3. Plastics in Healthcare

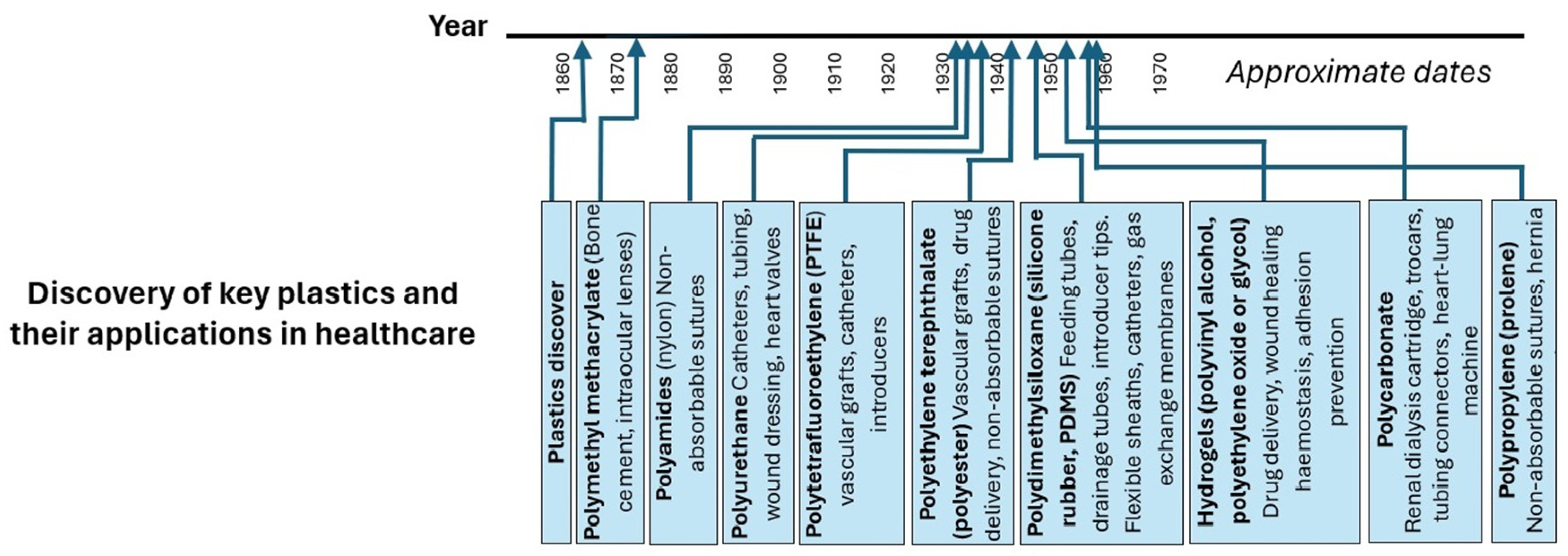

Plastics are essential in many areas of medicine and healthcare, medical equipment, prosthetics and implants, and drug packaging.

Figure 2 indicates some of the uses of plastics that have been produced over the years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, plastic-based PPE alone is estimated to have saved hundreds of thousands of lives worldwide. Plastics were seen as fundamental to the products required for life-saving treatment and control during this epidemic [

27]. In the healthcare industry generally, the development of single-use devices made of plastic has greatly reduced the rate of infection from contaminated equipment. Plastic syringes have enabled the widespread and low-cost distribution of vaccines, saving millions of lives globally, and plastic blood storage bags have revolutionized transfusion, with a huge impact on trauma care. There can be no doubt that plastics have saved millions of lives and made many more millions bearable, not least through the use of plastic surgery, which, while actually named after the Greek word for “shape”, or “mold”, uses plastic among many other materials.

Plastics are used for disposable instruments, not only syringes, but also catheters, endoscopes, and respirators, as well as packaging for these instruments. Plastic aprons, gloves and masks are standard hospital equipment. Chauhan et al. [

28] give a long list of hospital theatre instruments and the materials of their prior incarnations (e.g., face masks and theatre hats, previously made of paper or cotton). Plastics are also used in the manufacture of life-saving machines such as dialysis and heart-lung machines [

29]; they are components of pacemakers and heart valves, artificial joints and prosthetics [

30,

31], wound dressings [

32]. Plastics are used in both diagnosis and therapy of many diseases. They have multiple uses in diagnostic laboratories, from test tubes to bacterial identification kits, and they are essential for many recent developments in diagnostic techniques, for example, the Pill Cam, a minute camera enclosed in a plastic “pill case”, used to inspect the gastrointestinal tract. The ethical quandaries involved in the use of disposable plastics in healthcare are discussed by Pathak [

33]. Recent research explores bio-based and biodegradable plastics for medical applications to reduce long-term waste accumulation [

34]. A wealth of information on the uses and types of plastics in healthcare can be found in the book edited by Mozafari and Chauhan [

35].

The importance of plastics in healthcare cannot be denied. Millions of lives have been saved over the years and the global medical plastics market is expected to exceed U

$80.5 million by 2034, with the Asia-Pacific market being the largest [

36].

Figure 2.

Development of plastics over time and examples of their healthcare uses (adapted from [

37].

Figure 2.

Development of plastics over time and examples of their healthcare uses (adapted from [

37].

3.4. Plastics in the Construction Industry

Plastics have revolutionized the building industry. PVC was already being extensively used for water pipes in Japan and Europe by 1960; its corrosion resistance, as well as low weight, offer great advantages over the previously used materials. The building industry is now responsible for about 60% of the global demand for this plastic, using it not only for pipework but also for cables, flooring, windows, and roofing. Polystyrene and polyurethane are commonly used in thermal insulation. In building applications, plastics save energy [

38] and have the advantage of being more economical than traditional materials, while also being readily replaceable [

39]. Such replacement, of course, generates the problem of disposal. A new departure is the use of plastic waste in concrete [

40,

41]. Whilst not yet routine, several projects around the World have used plastic/concrete mixtures in precast beams (Netherlands) and panels (Australia), roads (India), and flood defence systems (Belgium); trials in Scotland incorporate up to 10% plastic waste in “Green Roads” [

42]. These approaches are part of a growing circular economy movement aimed at reducing environmental impacts from post-consumer plastic waste.

In terms of their effects on people’s lives, plastic pipes and filtration systems have long delivered clean water around the globe, which has helped to reduce the incidence of waterborne diseases like cholera and dysentery, saving millions of lives.

3.5. Plastics in the Textile Industry

Synthetic fibers derived from plastics have revolutionized the textile and, subsequently, the fashion industry [

43]. Perhaps the first, and certainly the most famous, early use of plastics was the replacement of women’s stockings by “nylons” in the late 1930s. This replacement of the more expensive silk (an animal product) allowed the everyday use of stockings by the less well off. After their introduction at the 1939 World Fair in New York, where they were advertised as having “the strength of steel and the sheerness of cobwebs”, their desirability was so great that the first 400 million pairs, released in May, 1940, sold out in 4 days. The first commercial polyester fiber, Terylene (made from PET), was produced in 1941. Polyester and polyamide fibers compose 76.2% of the global market share [

44]. Plastics have now transformed the textile industry and allowed fashion to extend beyond some of humankind’s wildest dreams.

However, the textile industry has been named the second most polluting industry in the world, second only to the petroleum industry [

45], and recent innovations in popular fashion have included the use of recycled plastic [

46,

47,

48] and degradable plastics [

49,

50]. The fashion and textile industries are aware of the problems and actively considering possible solutions.

Other industries with high usage of plastic materials include electronics, agricultural, and aerospace, while firefighting relies heavily on heat-resistant plastics, and Kevlar, used in bullet- and flame- resistant clothing, is composed of poly-para-phenylene terephthalamide. Once again, we see the life-saving function of plastics.

We can conclude that, since their development in the early 20th century, plastics have saved millions of dollars and tens of millions of lives. In healthcare alone, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that their use in infection control prevents millions of deaths annually. However, the previously desirable properties of this “wonder material” - durability and resistance - have led to its accumulation in the 20th and 21st centuries, giving rise to the global phenomenon of microplastics pollution, now recognized as a critical environmental and public health concern.

4. Microplastics

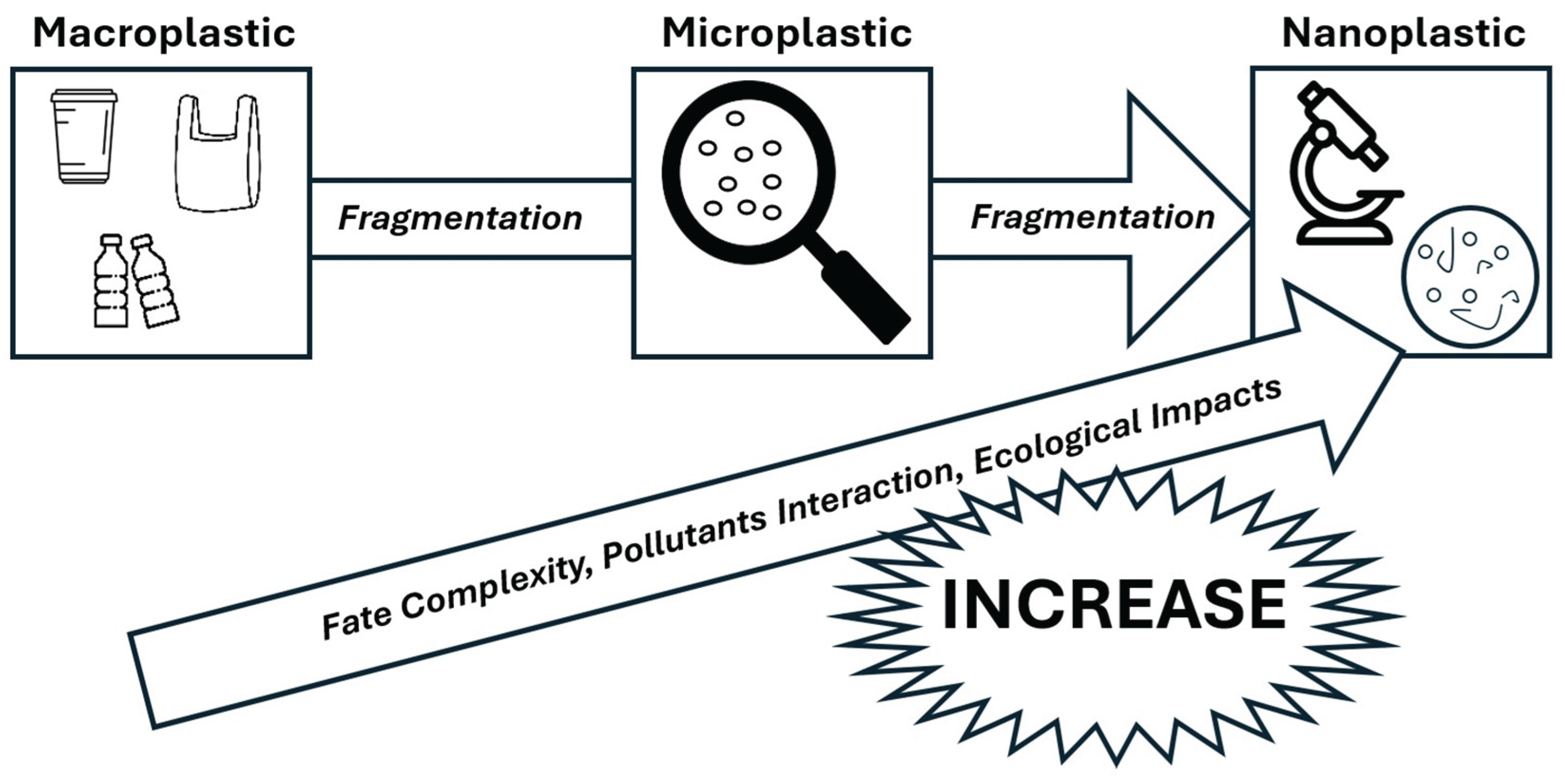

The term “microplastics” was first suggested in 2004 [

51]; they are defined as plastic particles less than 5mm in diameter. Glitter, for example, is a common, visible form of microplastic; it is made of 0.05 - 3.175 mm pieces of reflective material like aluminium bonded to PET. An invisible subdivision of microplastics, sized below 1μm, was detected more recently and named “nanoplastics” [

52]. These are now thought to be even more numerous in the environment than the larger particles. Microplastics occur in a variety of shapes, although the most frequently encountered in the environment are fibers [

53,

54,

55]; these may be longer than 5mm, but conform to the definition by being less than 5mm in diameter.

Initially, microplastics were detected in seawater. Discarded plastics washed up along the coasts of many countries had often been reported [

56,

57,

58], and the degradation of plastic materials to form small marine fragments had been indicated by Ketchum et al. as early as 1946 [

59]. They suggested that the insoluble resin matrix of antifouling paints could be removed by “erosion or exfoliation” in seawater. Although they did not recognize the fact, this would have led to the release of tiny sheets or particles of plastic polymer, or microplastics. Much later, it became clear that discarded macroplastics could also be naturally broken down into fragments and progressively smaller particles. Microplastics are now recognized not only in marine environments but also in freshwater systems, soils, and even the atmosphere. Urban runoff, wastewater treatment effluents, industrial discharges, landfill leachates, tire wear, and synthetic textiles are major terrestrial sources [

60].

Atmospheric microplastics can travel long distances and deposit in remote regions, including polar areas, illustrating their global dispersal [

61]. Their long-term environmental impact has now become a focus of public concern, these particles being seen as a serious environmental and public health risk [

62]. Micro- and nanoplastics can adsorb persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals, and pathogens, acting as vectors that may facilitate the entry of these contaminants into the food chain (

Figure 3). They have been detected in fish, shellfish, and even in drinking water and human stools, highlighting potential human exposure [

63,

64,

65].

The more recent discovery of nanoplastics, more difficult to detect and analyze because of their size, has not yet led to such public concern. However, in July 2025, the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research reported that there are around 27 million tonnes of nanoplastics in the northern Atlantic alone [

66]. This value is equal to or greater than that previously estimated for the total weight of macroplastics plus the larger microplastics in the world’s oceans. Nanoplastics are becoming a major public concern. Research is increasingly focused on the ecological and toxicological impacts of all microplastics, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and potential endocrine disruption in aquatic organisms, as well as the need for improved monitoring, mitigation strategies, and regulatory policies worldwide [

9,

20].

4.1. Location and Effects of Microplastics

Microplastics have been found in all environmental compartments, air, water and soil, as well as in living plants and animals; they are truly universal. Their presence in geological sediments has led to them becoming markers of the Anthropocene, the geological period marked by the activities of human beings [

67]. Recent studies have detected microplastics in remote mountain environments, polar ice, and deep-sea sediments, highlighting their global transport via wind, rivers, and ocean currents [

68,

69,

70,

71]. They are found from the tropics to the Poles and are particularly concentrated in the indoor air of buildings with high human activity [

72,

73].

4.1.1. Microplastics in the Air

Microplastics were first reported in the air by Dris’ group, working in Paris; even at this early stage, working with early microplastics detection methods, they noted higher indoor than outdoor microplastics concentrations in the air [

74,

75]. This has since been confirmed by numerous workers in many countries [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80]. The presence of high microplastic levels in houses and other buildings clearly poses a potential threat to those living and working in these locations. Airborne microparticles can be inhaled by humans and have, indeed, been detected in the lower lung [

81]. Like soot, nanoplastic particles, once inhaled, can penetrate to the alveoli of the human lung [

82], although microplastics have not been recorded as the cause of human death. Emerging evidence indicates, however, that chronic inhalation may trigger immune responses, oxidative stress, and pulmonary inflammation.

Again like soot, microplastics can attach to and disfigure building surfaces. As airborne microplastics are carried over and along solid surfaces by airflow, there will be preferential near-wall particle accumulation, as defined by Stokes numbers [

83], together with inertial effects [

84]. This, together with deposition on horizontal surfaces in low-flow areas, leads to particles becoming attached to building surfaces, aided by the presence of deposited “sticky” biomaterials (biofilms), as found in biofilm-based wastewater treatment (WWT) systems [

85] and artificial freshwater lake systems [

86]. Hence microplastics will add to the discoloration of buildings noted in industrial, “sooty” areas prior to emissions control measures.

4.1.2. Microplastics in Water

Microplastics are found in both salt and freshwater and even in bottled water, derived from the cap, as well as the bottle itself in the case of plastic bottles. In fact, bottled water contains higher microplastics levels than tap water [

87]. Processes of filling and refilling bottles add to the microplastics load. Microplastics were first reported, however, in seawater [

88]. Major inputs to the sea are, in order of magnitude according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): synthetic textiles, vehicle tyres, road markings, personal care products and cosmetics, plastic pellets (“nurdles”), marine coatings, and city dust. They are transferred to the marine environment from their terrestrial sources by road runoff, WWT plants, wind, and marine activities, in that order [

89]. Nurdles are small pellets used in manufacturing of plastic products; their size classifies them as microplastics and the fact that they are not derived from larger plastics classifies them as “primary”, as opposed to “secondary” microplastics. They were first reported in British waters in 1970 [

90] and are the second largest source of primary plastic pollution in the world (the first said to be tire particles); an estimated 445,970 tonnes of nurdles enters the oceans yearly [

91]. Major sources are leakages at production sites and spills during transportation, the most famous marine accident leading to such pollution being the MV X-Press Pearl cargo disaster in 2021, when the west coast of Sri Lanka was covered with tons of plastic nurdles [

92]. Although clean-up procedures are in place, its impact will persist in the Indian Ocean for centuries.

4.1.3. Effects of Microplastics in Animals

Microplastics bioaccumulate in organisms and can transfer through trophic levels, with potential effects on predators, including humans [

93]. In marine organisms, they may cause reduced feeding efficiency, energy depletion, reproductive impairment, and oxidative stress. Fish, for example, may mistake these small, often colored, particles for food prey [

94], reducing their uptake of genuinely nutritious material and instituting the cellular reactions that result in bodily harm and possibly death. The effects of microplastics on marine life remain the most researched and reported aspects of microplastics pollution, although there are reports of these particles in wild and domestic animals and birds [

95,

96,

97].

It is not only the polymer itself that is the threat, but also the harmful plastic additives (

Table 1) and the molecules that have adhered to the particles in the environment [

98,

99]. The latter can include fuel hydrocarbons [

100], polycyclic aromatic compounds (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), all of which are persistent pollutants [

101,

102]. Poisonous metals such as zinc and lead have also been reported as contaminants on microplastic surfaces [

103,

104]. Additionally, microplastics can act as vectors for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and other pathogens, amplifying ecological and health risks.

Microplastics have been found in a wide variety of animals, ranging from invertebrates such as mollusks, crustaceans, and plankton, to higher vertebrates including fish, birds, and marine mammals. As expected from the initial identification of these particles in seawater, fish are the most frequently reported group, likely due to their position in aquatic food webs and their feeding behaviors, which include filter-feeding and ingestion of prey mistaken for food [

105,

106]. In addition, these particles can transfer up the food chain, leading to bioaccumulation in predatory species and potentially exposing humans to microplastics through consumption of fishery and aquaculture products [

93,

107,

108,

109,

110]. Studies have documented microplastic ingestion in commercially important fish such as anchovies, sardines, and cod, emphasizing the ecological and economic implications of this pollution [

111,

112,

113,

114].

The only class of animals in which microplastics have never been reported are tardigrades, tiny invertebrates, up to 2mm in size, that live in mosses, lichens, soil, sand, freshwater and the sea. They have a mouth and pierce and suck up liquid from algae, moss and flowering plants. There would be no problem in the uptake of nanoplastics into their gut in this way, but they do not suck up water, thus greatly reducing their potential microplastic sources. This may explain why they have not, so far, been shown to contain these particles, although one recent study has shown that they can attach to the surface of recycled polypropylene [

115].

Microplastics have been shown to cause problems such as gut blockage and inflammation of various organs in fish, birds, mice and rats, as well as inhibition of photosynthesis and growth in terrestrial and aquatic plants, in some of which they cause the enzyme changes related to inflammation in animals. Additional studies indicate neurological effects, endocrine disruption, and immune dysregulation in exposed animals, although mechanisms are still under investigation [

116,

117,

118].

4.1.4. Effects of Microplastics in Humans

Although there is no definitive proof of their adverse effects in human beings, they have been identified in feces, urine, tears, sputum, blood, breast milk, lungs, heart, liver, placenta, bone and cartilage, and brain. When found in human tissues, they have been associated with cellular inflammatory responses - most recently, in hip and knee joints [

119]. There is, then, growing evidence that microplastics are, themselves, injurious to human health, but perhaps even more convincing is the fact that plastics contain a wide variety of additives, used to confer certain desirable qualities upon them (

Table 1), that can injure the human organism, for example, the plasticizer Bisphenol A, which has effects on the hormonal system; its use is regulated in the European Union. Additionally, contaminants such as heavy metals (e.g., lead, mercury, arsenic) can adhere to microplastics, facilitating their uptake by living things and causing a variety of harmful effects in animals that can be transmitted to humans through the trophic chain.

4.1.5. Microplastics and Climate Change

Microplastics are also environmentally important because of their effects on global warming. They do this by increasing the levels of greenhouse gases and by directly affecting the Earth’s thermal balance [

120]. They also affect cloud and ice formation, influencing weather systems [

121,

122]. Their degradation releases carbon and nitrous oxides, and methane. Recently it has been shown that small PET microplastics stimulate the production of nitrous oxide production in WWT systems [

123]. Microplastics can also reduce the sequestration of CO

2 by marine photosynthetic organisms, including phytoplankton and cyanobacteria, potentially altering the carbon cycle and thus contributing to climate change [

124,

125,

126]. Not only do microplastics contribute to global warming, but the environmental changes accompanying the latter also affect the formation and dispersal of microplastics; there is a circular relationship between microplastics and climate change [

127].

4.2. Remedial Measures for Microplastic Pollution

The quest for methods to reduce the amount of microplastics in the environment occurs at two levels, attempts to reduce current concentrations and organizational and governmental efforts to control future emissions.

4.2.1. Degradation of Microplastics

Microplastics are gradually broken down in the environment by light, heat, chemical, and biological action, but the rate is slow. A number of attempts have been made to increase degradation of these particles in sewage, in order to reduce the numbers released from WWT works. Standard WWT does not remove the majority of microplastics and some may even be added during processing, from plastic pipework or filters, for example [

128]. Wolff [

129] reported the release of 3000 - 5900 microplastic particles per day from a German WWT plant. The resultant sludge (the solids left after removal of treated water) may be burned, discarded to landfill, the major destination in China [

130], or used as agricultural fertilizer, the major application in Europe [

131]. The considerable regulations governing land application in the USA are detailed in Lue-Hing [

132]; microplastics in the sludge are not yet, apparently, deemed a major consideration. However, various biological, chemical and physical steps have been added in WWT plants to reduce the microplastic load; these can be partially, but are never totally, effective. Sometimes, microplastics may even be added during treatment. The moving bed film reactor is an innovative treatment process for wastewaters that can be highly effective. However, its makeup involves carrier surfaces to which the bacteria responsible for organic pollutant breakdown adhere. These surfaces may be composed of plastic, and these reactors have been found to add microplastics to treated water in some cases [

133].

A number of possible methods for the breakdown/removal of microplastics in waste and contaminated environments have been studied by researchers, far too many for discussion here. Considering just a few of the original and review papers published on the topic in the first 7 months of the present year gives an indication of the breadth and importance of this research area [

102,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139] all published relevant papers in 2025. Basically, the methods are based on developments in chemical, physical and microbiological applications. Often, they are too expensive for routine use, although methods for reducing costs could be developed. It is necessary to determine the level of reduction in microplastics concentration required to make the techniques acceptable; complete removal of microplastics in a reasonable time and at a reasonable price is currently unrealistic.

4.2.2. Replacement with Biodegradable Plastics

An alternative means of reducing dangerous microplastics levels in the future, already being adopted in several countries, is the replacement of fossil fuel-based microplastics [

140,

141,

142,

143].

The development of “bioplastics” and “biodegradable plastics” is relatively recent and they have yet to fulfill their promise. In both cases, the replacement of part of the artificial plastic chain with biological material instills a degree of biodegradability. Yet the final product may not have the necessary properties (strength, flexibility, etc.) and, even if broken down in the environment, there will still be a microplastic stage [

144], although this may be shorter and less harmful than the current petroleum-based particles. It must be remembered, however, that the complete degradation of all plastics, whilst removing them from the environment, leads to the emission of carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas involved in global warming; biodegradable plastics are more dangerous than hydrocarbon-based plastics in this respect [

145].

4.2.3. Recycling

Although plastics are technically recyclable and in many cases could be reused, the reality is that recycling rates remain strikingly low due to high processing costs, limited infrastructure, and the complexity of segregating mixed plastic waste streams. Globally, only about 9% of plastic waste is actually recycled, a figure that has stagnated in recent years [

10,

146]. Moreover, only around 9.5% of new plastics are produced from recycled content, and mechanical recycling processes effectively recover just 2% of plastics, with less than 1% being recycled into new products more than once [

146]. Europe currently leads global efforts in plastics recovery, with advanced systems for sorting and waste segregation. Within Europe, Scandinavian countries, as well as Germany and Slovenia, demonstrate some of the most effective recycling practices worldwide, achieving recovery rates close to 50% [

147]. This figure is significantly higher than the global average, which remains at approximately 9%. Nonetheless, the overall picture is discouraging: an estimated 60% of all plastics produced are designed for single-use purposes, meaning they are discarded shortly after consumption. According to Houssini et al. [

148], only about 10% of plastic waste is effectively recycled worldwide, underscoring the enormous gap between the theoretical recyclability of plastics and their actual recovery in practice.

In response to this challenge, various technological and policy-driven solutions are being implemented. On the technological side, advances in chemical recycling—such as pyrolysis and depolymerization—aim to break plastics down into their original monomers, enabling their reintegration into production cycles with minimal loss of quality [

149,

150]. Similarly, the development of enzymatic recycling technologies has shown promise in degrading certain polymers, such as PET, in a more environmentally friendly manner [

151,

152]. From a policy perspective, many countries in the European Union have adopted the principle of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), which makes manufacturers financially and logistically accountable for the post-consumer phase of their products [

153]. Additionally, bans on certain single-use plastics, combined with incentives for eco-design and the promotion of a circular economy, have been effective in reducing waste generation and improving recycling outcomes [

154,

155]. Together, these measures illustrate that bridging the gap between recyclability and actual recycling requires not only technological innovation but also systemic policy interventions and behavioral changes at the consumer level.

4.2.4. Global Policy Interventions on Microplastics Control

In 2022, the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) produced two policy scenarios to reduce the environmental impact of plastics, considering reduction of environmental pollution and increase in the circular economy. Suggested actions were based on plastics taxation, together with increased recycling, landfill, and producer responsibility, as well as appropriate aid to developing countries. Recently, Sonke et al. [

156] published the results of their modeling of the OECD scenarios towards 2060. They showed a peak of land to sea microplastics transport of 23Tg/y around 2025, with the decrease thereafter marred by continuing fragmentation and release of legacy mismanaged waste, together with nanoplastics released from the cryosphere (frozen water and permafrost), which has already been detected in several countries [

157].

Progress is slow on international agreement about the future of plastic management. In August, 2025, the UN countries reconvened in Geneva in an attempt to resolve the issue of the breadth of the final treaty - should it focus merely on plastic waste management, or should it also aim to cut production and eliminate the use of toxic chemicals? Finally, no agreement could be reached. The meeting stalled and no further talks are yet planned.

Some country-based resolutions around the topic have been taken. In July, 2025, DTSC (the USA Department of Toxic Substances Control) released a press statement proposing to add microplastics to the Candidate Chemicals List, allowing them to evaluate products that contribute to microplastics pollution for future regulation. Within the European Union, some countries, such as Sweden, have initiated plans to deal with the microplastics issue, with some cities already having developed strategies [

158]. India also has some controls at government level [

159], while China has developed regulatory frameworks and some governmental initiatives over the last 10 years [

160]. There are some local regulations around the world that tackle the microplastics problem; California, for example, has a microplastics strategy, and is a leader in this subject in the USA [

161], but the recent failure of the UN discussions on the plastic pollution treaty does not auger well for future global agreements.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We asked whether microplastics are the soot of today and also considered the story of asbestos, which began as a “magic mineral” when it came into commercial use in the 1870s, but became a deadly dust when found to cause lung fibrosis in asbestos workers. Regulations to control asbestos were introduced in 1931, but by the time the material was banned in the UK in 2000, it had already claimed many thousands of lives [

162]. In a similar fashion to microplastics, schemes for the control of asbestos had been suggested over the years. In 2007 the 60th World Health Assembly endorsed an action plan for the elimination of asbestos-related diseases. Asbestos disposal has been regulated in Europe since 2005, but it remains an environmental problem [

163]. It differs from microplastics in that the evidence for a direct link with human disease is clearly evident. Asbestos fibers are impossible to misidentify, easy to detect in the lung, though related diseases, such as mesothelioma, a rare and usually fatal form of lung cancer caused by asbestos inhalation, can take up to 50 years to appear. Asbestos fibers are similar in appearance to microplastic fibers, but smaller than the larger microplastics and less variable in size, ranging only from 0.01 - 1.5μm in diameter and 0.01 - 64μm in length [

164]. Asbestos is not as widespread in the environment and is chiefly a problem where asbestos is concentrated, usually in the workplace. The fibers are chemically less diverse and are, at least partially, under some form of environmental control in many countries. However, it has to be recognized that asbestos controls have not been as effective as those for soot.

We might more reasonably liken small airborne microplastics/nanoplastics to soot, which consists of impure carbon particles resulting from the incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons. They are generally very small, only a few hundreds of nanometers, and somewhat chemically diverse, but do not have the major differences in chemical structure demonstrated by microplastics. Soot has the same ability to discolour surfaces and to be inhaled and accumulated by living animals with detrimental and, in this case proven, lethal results. Indeed, it is classified as carcinogenic by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Soot also leads to the same type of inflammatory responses as microplastics [

165] and can adsorb toxic organic substances like PAHs [

166]. The damage caused by microplastics, however, may be considered to be even greater, because of the totality of their physical and chemical properties and greater reach, being resistant to breakdown, toxic in nature (because of additives), able to act as carriers of pollution, promoters of climate change, and found in all environments throughout the world, including the stratosphere.

Microplastics are pervasive and dangerous. The climate and ecosystems of the whole world are threatened. However, Humankind is already developing potential remedies and we may, perhaps, hope that the production of these particles will begin to decrease in the future. Though plastics have saved many lives, they also contribute, via microplastics, to pollution and environmental harm, which have unknown long-term health impacts. It has been suggested that, in any future UN agreements on plastics control, plastics involved in the medical field and required to save lives should be exempt. However, a comment published in The Lancet in 2024 puts the case for not excluding medical and health products from any global treaty [

167]. An electronic survey among UN delegates to the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee for the Global Plastics Treaty in 2022 [

168] showed that human health was the main area for concern, with a Social Responsiveness Score (SRS) of 54, followed by ecosystems and biodiversity (SRS 42), and then climate change and air pollution (SRS 34). Food systems and safety, economic and employment risks, and human rights received decreasingly lower scores. Of the respondents, 96% believed that the identification of microplastics in human tissues is associated with health risks. Although not all delegates answered the questionnaire and those answering were a self-selected group with, possibly, preconceived ideas, it is nevertheless likely that these figures will be mirrored in the general population.

Some form of control must be exercised over microplastic pollution. If drastic reductions of plastic production are not possible, then controls over microplastic release into the open environment will be essential. The goal going forward could be to maximize the life-saving benefits of plastics while minimizing environmental harm through correct recycling and disposal, biodegradables, and smart design.

Would the world have been better without the development of the original plastics which, as well as being the source of these troublesome particles, have aided Humankind in so many ways?

History will decide.

Author Contributions

CG - Conceptualization, investigation, editing, first and final drafts; EMdaF - Investigation, elaboration of figures, editing, first and final drafts; GG - Investigation, editing, first and final drafts; KG - Conceptualization, investigation, editing, final draft. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

EMdaF is grateful to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for ongoing support at UFF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Laskin, D. The great London smog. Weatherwise 2006, 59, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, B. The Life Saving Potential of Coal. Inst. Public Aff. Rev. 2015, 67, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, L. Properties and Uses of Asbestos. In Asbestos. In Asbestos the Hazardous Fiber; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 27–43. ISBN 9781351069922. [Google Scholar]

- Durczak, K.; Pyzalski, M.; Brylewski, T.; Juszczyk, M.; Leśniak, A.; Libura, M.; Ustinovičius, L.; Vaišnoras, M. Modern Methods of Asbestos Waste Management as Innovative Solutions for Recycling and Sustainable Cement Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. Social and economic costs and benefits of coal. In The Coal Handbook; Osbourne, D., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pira, E.; Donato, F.; Maida, L.; Discalzi, G. Exposure to asbestos: past, present and future. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10 (Suppl. 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaDou, J.; Castleman, B.; Frank, A.; Gochfeld, M.; Greenberg, M.; Huff, J.; Joshi, T.K.; Landrigan, P.J.; Lemen, R.; Myers, J.; Soffritti, M. The case for a global ban on asbestos. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, L. A Brief History of the Use of Plastics. Camb. Prisms Plast. 2024, 2, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and human health: A micro issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albazoni, H.J.; Al-Haidarey, M.J.S.; Nasir, A.S. A Review of Microplastic Pollution: Harmful Effect on Environment and Animals, Remediation Strategies. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L.; Neal, M.A. Applications and Societal Benefits of Plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.P. Sustainable Plastics: Environmental Assessments of Biobased, Biodegradable, and Recycled Plastics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-119-88206-0. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.; Deussing, G. Courageous questioning of established thinking: The life and work of Hermann Staudinger. In Hierarchical Macromolecular Structures: 60 Years after the Staudinger. In Hierarchical Macromolecular Structures: 60 Years after the Staudinger Nobel Prize I; Percec, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, G. Plastics Additives: An AZ Reference; Springer Science and Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monclús, L.; Arp, H.P.H.; Groh, K.J.; Faltynkova, A.; Løseth, M.E.; Muncke, J.; Wang, Z.; Wolf, R.; Zimmermann, L.; Wagner, M. Mapping the chemical complexity of plastics. Nature 2025, 643, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, M.; Moreno-Garrido, I.; Blasco, J. Single and multispecies microalgae toxicological tests assessing the impact of several BPA analogues used by industry. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sladič, M.; Smrkolj, Š.; Kavšek, G.; Imamovic-Kumalic, S.; Verdenik, I.; Virant-Klun, I. Bisphenol A in the urine: Association with urinary creatinine, impaired kidney function, use of plastic food and beverage storage products but not with serum anti-Müllerian hormone in ovarian malignancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, J.P.; Avellan, A.; Mouneyrac, C.; Duarte, A.; Rocha-Santos, T. Plastic Additives and Microplastics as Emerging Contaminants: Mechanisms and Analytical Assessment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Brookson, C.; Bikker, J.; Djuric, N.; Earn, A.; Bucci, K.; Athey, S.; Huntington, A.; McIlwraith, H.; Munno, K.; De Frond, H.; Kolomijeca, A.; Law, K.L. Rethinking microplastics as a diverse contaminant suite. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. UNEP Frontiers 2016 Report: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Plastic Pollution. Available online: https://www.unep.org/topics/chemicals-and-pollution-action/plastic-pollution (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Stevens, S.; McPartland, M.; Bartosova, Z.; Skåland, H.S.; Volker, J.; Wagner, M. Plastic food packaging from five countries contains endocrine- and metabolism-disrupting chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 4859–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V. Packaging material in the food industry. In Antimicrobial Food Packaging; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, G.; Puricelli, S.; Cecere, G.; Tua, C.; Fava, F.; Rigamonti, L.; Grosso, M. How Does Plastic Compare with Alternative Materials in the Packaging Sector? A Systematic Review of LCA Studies. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, S.A.; Deshpande, A.M.; Limaye, M.; Iyer, R.K.; Kazan, H.; Li, G.; Pilla, S. A perspective on the evolution of plastics and composites in the automotive industry. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 705–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, J. Do no harm: Plastics are playing a major role in giving healthcare professionals the tools and capabilities they need to battle the COVID pandemic. Plast. Eng. 2020, 76, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, M.N.; Majeed, T.; Aisha, N.; Canelo, R. Use of Plastic Products in Operation Theatres in NHS and Environmental Drive to Curb Use of Plastics. World J. Surg. Surg. Res. 2019, 2, 1088. [Google Scholar]

- Padsalgikar, A. Plastics in medical devices for cardiovascular applications. William Andrew, Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017. ISBN: 9780323371223.

- Rezvova, M.A.; Klyshnikov, K.Y.; Gritskevich, A.A.; Ovcharenko, E.A. Polymeric heart valves will displace mechanical and tissue heart valves: A new era for the medical devices. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, E.; Kurtz, S.M.; Muratoglu, O.K. Ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene total joint implants. In Comprehensive Biomaterials II; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornseifer, U.; Lonic, D.; Gerstung, T.I.; Herter, F.; Fichter, A.M.; Holm, C.; Schuster, T.; Ninkovic, M. The Ideal Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor-Site Dressing: A Clinical Comparative Trial of a Modified Polyurethane Dressing and Aquacel. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, G. “The statistical view is not the moral view”: Disposable medical plastics as toxic infrastructure. Am. Anthropol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkbid, E.; Cree, D.E.; Bradford, L.; Zhang, W. Biodegradable alternatives to plastic in medical equipment: Current state, challenges, and the future. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.; Chauhan, N.P.S. (Eds.) Handbook of Polymers in Medicine; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 9780128237977. [Google Scholar]

- Precedence Research. Medical Plastics Market. 2025. Available online: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/medical-plastics-market (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Rizan, C.; Mortimer, F.; Stancliffe, R.; Bhutta, M.F. Plastics in healthcare: Time for a re-evaluation. J. R. Soc. Med. 2020, 113, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrady, A.L. Plastics and Environmental Sustainability; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamošaitienė, J.; Parham, S.; Sarvari, H.; Chan, D.W.; Edwards, D.J. A review of the application of synthetic and natural polymers as construction and building materials for achieving sustainable construction. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, P.; Kaur, D.P.; Raj, S.; Sorout, J. Recycling/reuse of plastic waste as construction material for sustainable development: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86156–86179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, H.M.; Al-Attar, A.; Abed, F.; Beddu, S.; Humada, A.M.; Majdi, A.; Yousif, S.T.; Thomas, B.S. Enhancing Sustainability in Concrete Construction: A Comprehensive Review of Plastic Waste as an Aggregate Material. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40, e00877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minde, P.; Kulkarni, M.; Patil, J.; Shelake, A. Comprehensive review on the use of plastic waste in sustainable concrete construction. Discover Mater. 2024, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, S. Nylon: The Story of a Fashion Revolution: A Celebration of Design from Art Silk to Nylon and Thinking Fibres; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, R.; Jajpura, L.; Khandual, A. Traditional fibres for fashion and textiles: Associated problems and future sustainable fibres. In Sustainable Fibres for Fashion and Textile Manufacturing; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariana-Claudia, M. The fashion industry and its impact on the environment. Ann. ’Constantin Brancusi’ Univ. Targu-Jiu 2022, 1, 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.Y.; Zheng, R.; Zhou, L.; Yang, X.; Lin, J. Practical Investigation of Innovative Sustainable Fashion Design Using Plastic Waste. J. Fiber Bioeng. Bioinform. 2022, 15, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Sen, K.K.; Mochida, T.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Kishimoto, K. Overcoming Barriers to Proactive Plastic Recycling toward a Sustainable Future. Environ. Challenges 2024, 17, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, F.; Sadachar, A. Constructive Controversy on Fashion from Plastic: Perceived Value, Attitude, and Purchase Intentions toward Apparel Made of Recycled Polyester Fabric. Int. Text. Appar. Assoc. Annu. Conf. Proc. 2025, 81, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Hong, Y.; Yan, T.; Xie, X.; Zeng, X. A Systematic Review of Biodegradable Materials in the Textile and Apparel Industry. J. Text. Inst. 2023, 115, 1173–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, R.K.; Eghan, B.; Acquaye, R. A review of circular fashion and bio-based materials in the fashion industry. Circular Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; Ter Halle, A.; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current Opinion: What Is a Nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Glamoclija, M.; Murphy, A.; Gao, Y. Characterization of microplastics in indoor and ambient air in northern New Jersey. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, T.; Yan, M.; Yang, L.; Gong, H.; Wang, W.; Qing, X.; Wang, J. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a subtropical urban environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.A. Sources and Dispersive Modes of Micro-Fibers in the Environment. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2017, 13, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyerdahl, T. Atlantic Ocean Pollution and Biota Observed by the ‘Ra’ Expeditions. Biol. Conserv. 1970, 2, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, E.J.; Smith, K.L. Plastics on the Sargasso Sea Surface. Science 1972, 175, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, T. Oceans of Garbage. Nature 1991, 352, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchum, B.H.; Ferry, J.D.; Burns, A.E. Action of antifouling paints. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1946, 38, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yu, Z.G.; Thakur, T.K. Microplastic pollutants in terrestrial and aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 107296–107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Durántez Jiménez, P.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric Transport and Deposition of Microplastics in a Remote Mountain Catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, A.I.; Kramm, J.; Völker, C.; Henry, T.B.; Everaert, G. Risk Posed by Microplastics: Scientific Evidence and Public Perception. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 29, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, G.; Nugegoda, D.; Haroon, A.Y. Microplastic pollution and contamination of seafood (including fish, sharks, mussels, oysters, shrimps and seaweeds): a global overview. In Microplastic Pollution: Environmental Occurrence and Treatment Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 277–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabl, P.; Köppel, S.; Königshofer, P.; Bucsics, T.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; Liebmann, B. Detection of various microplastics in human stool: A prospective case series. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Kang, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z. Microplastics in drinking water: A review on methods, occurrence, sources, and potential risks assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hietbrink, S.; Materić, D.; Holzinger, R.; Groeskamp, S.; Niemann, H. Nanoplastic concentrations across the North Atlantic. Nature 2025, 643, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Da Fonseca, E.M. Microplastics in Museums: Pollution and Paleoecology. Trends Ecol. Environ. Eng. 2025, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, B.; Yu, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z. Remote mountainous area inevitably becomes temporal sink for microplastics driven by atmospheric transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13380–13390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corami, F.; Iannilli, V.; Hallanger, I.G. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Polar Areas: Arctic, Antarctica, and the World’s Glaciers. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1587557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Yukioka, S.; Li, W.; Imbulana, S.; Oluwoye, I.; Shim, W.; Sun, C.; Mochida, K.; Takada, H. Towards a North Pacific Ocean long-term monitoring program for plastic pollution: a review of global occurrence of microplastics in the sea and deep-sea sediments. J. Water Environ. Technol. 2024, 22(5), 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Grythe, H.; Klimont, Z.; Heyes, C.; Eckhardt, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Stohl, A. Atmospheric Transport Is a Major Pathway of Microplastics to Remote Regions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niari, M.H.; Ghobadi, H.; Amani, M.; Aslani, M.R.; Fazlzadeh, M.; Matin, S.; Takaldani, A.H.S.; Hosseininia, S. Characteristics and assessment of exposure to microplastics through inhalation in indoor air of hospitals. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2025, 18, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovenko, N.; Pérez-Serrano, L.; Segur, T.; Hagelskjaer, O.; Margenat, H.; Le Roux, G.; Sonke, J.E. Human exposure to PM10 microplastics in indoor air. PLoS ONE 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Saad, M.; Renault, N.; Tassin, B. Microplastic Contamination in an Urban Area: A Case Study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperi, J.; Dris, R.; Mirande-Bret, C.; Mandin, C.; Langlois, V.; Tassin, B. First Overview of Microplastics in Indoor and Outdoor Air. In Proceedings of the 15th EuCheMS International Conference on Chemistry and the Environment, Leipzig, Germany, September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ageel, H.K.; Harrad, S.; Abdallah, M.A.E. Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Risk of Microplastics in the Indoor Environment. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2022, 24, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, T.; Casillas, G.; Zarus, G.M.; Barr, D.B. Systematic Review of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Indoor and Outdoor Air: Identifying a Framework and Data Needs for Quantifying Human Inhalation Exposures. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzaib, M.; Sharma, S.; Park, D. Microplastics comparison of indoor and outdoor air and ventilation rate effect in outskirts of the Seoul metropolitan city. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Baptista Neto, J.A.; Da Fonseca, E.M. Indoor Airborne Microplastics: Human Health Importance and Effects of Air Filtration and Turbulence. Microplastics 2024, 3, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Baptista Neto, J.A.; Da Fonseca, E.M. Atmospheric Microplastics: Inputs and Outputs. Micro 2025, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Martínez, C.; Olmos, S.; González-Pleiter, M.; López-Castellanos, J.; García-Pachón, E.; Masiá-Canuto, M.; Hernández-Blasco, L.; Bayo, J. First Evidence of Microplastics Isolated in European Citizens’ Lower Airway. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Lu, W.; Tu, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, M.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Lin, M.; Zhang, Y. Evidence of microplastics in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among never-smokers: A prospective case series. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardina, G.; Schlatter, P.; Picano, F.; Casciola, C.M.; Brandt, L.; Henningson, D.S. Self-similar transport of inertial particles in a turbulent boundary layer. J. Fluid Mech. 2012, 706, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Chamecki, M. Inertial effects on the vertical transport of suspended particles in a turbulent boundary layer. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2018, 167, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, T.; Lin, B.; Ke, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Microplastics-biofilm interactions in biofilm-based wastewater treatment processes: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 361, 124836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Bucci, K.; Langenfeld, D.; McNamee, R.; Veneruzzo, C.; Covernton, G.A.; Gao, G.H.Y.; Ghosh, M.; Cable, R.N.; Hermabessiere, L.; Lazcano, R.; Paterson, M.J.; Rennie, M.D.; Rooney, R.C.; Helm, P.; Duhaime, M.B.; Hoellein, T.; Jeffries, K.M.; Hoffman, M.J.; Orihel, D.M.; Provencher, J.F. Informing the Exposure Landscape: The Fate of Microplastics in a Large Pelagic In-Lake Mesocosm Experiment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, L.; Long, Z.; Mindong, M.; Haiwen, W.; Lihui, A.; Zhanhong, Y. Occurrence of Microplastics in Commercially Sold Bottled Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, E.J.; Anderson, S.J.; Harvey, G.R.; Miklas, H.P.; Peck, B.B. Polystyrene Spherules in Coastal Waters. Science 1972, 178, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MUFG. 2025 https://www.firstsentier-mufg-sustainability.com/research/microplastics-05-2020.html.

- Sewwandi, M.; Keerthanan, S.; Perera, K.I.; Vithanage, M. Plastic nurdles in marine environments due to accidental spillage. In Microplastics in the Ecosphere: Air, Water, Soil, and Food; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. White Tides: The Plastic Nurdles Problem. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, U.L.H.P.; Ratnayake, A.S. X-Press Pearl Disaster. In Coastal and Marine Pollution: Source to Sink, Mitigation and Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setälä, O.; Fleming-Lehtinen, V.; Lehtiniemi, M. Ingestion and transfer of microplastics in the planktonic food web. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres-Farias, L.; Espinoza-Vera, M.M.; Orós, J.; Garcia-Bereguiain, M.A.; Alfaro-Núñez, A. Macro and Microplastic Intake in Seafood Variates by the Marine Organism’s Feeding Behaviour: Is It a Concern to Human Health? Heliyon 2023, 9, e16692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, J.C.; Dias-Pereira, P. Microplastics in terrestrial domestic animals and human health: Implications for food security and food safety and their role as sentinels. Animals 2023, 13, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Shu, X.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Zhu, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, X. Microplastic pollution of threatened terrestrial wildlife in nature reserves of Qinling Mts., China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 51, e02865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayman, C.; González-Pleiter, M.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; Sorribes, E.L.; Fernández-Valeriano, R.; López-Márquez, I.; González-González, F.; Rosal, R. Accumulation of microplastics in predatory birds near a densely populated urban area. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, A.; Champeau, O.; Chatel, A.; Manier, N.; Northcott, G.; Tremblay, L.A. Plastic Additives: Challenges in Ecotox Hazard Assessment. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mato, Y.; Isobe, T.; Takada, H.; Kanehiro, H.; Ohtake, C.; Kaminuma, T. Plastic resin pellets as a transport medium for toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Becker, R.; Dorgerloh, U.; Simon, F.G.; Braun, U. The effect of polymer aging on the uptake of fuel aromatics and ethers by microplastics. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, E.; Collins, A.; Hatinoglu, M.D.; Bhagat, K.; MacRae, J.; Perreault, F.; Apul, O. Adsorption of Organic Pollutants by Microplastics: Overview of a Dissonant Literature. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 6, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jin, K.; Yin, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Y.; Ao, T.; Li, Y.; Duan, X. Advanced oxidation in the treatment of microplastics in water: A review. Desal. Water Treat. 2025b, 101135. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guo, P.; Zhang, X.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Microplastics and Accumulated Heavy Metals in Restored Mangrove Wetland Surface Sediments at Jinjiang Estuary (Fujian, China). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Musfir, A.; Kaushal, S.; Ajay, K.; Meena, V.P.; Karthick, B.; Anoop, A. Distribution, sources, and heavy metal interactions of microplastics in groundwater and sediment of semi-arid regions of Northwest India. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusher, A.L.; McHugh, M.; Thompson, R.C. Occurrence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract of pelagic and demersal fish from the English Channel. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 67, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberghini, L.; Truant, A.; Santonicola, S.; Colavita, G.; Giaccone, V. Microplastics in Fish and Fishery Products and Risks for Human Health: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, N.T.; Islam, M.R.U.; Sultana, S.; Banik, P.; Nur, A.A.U.; Albeshr, M.F.; Arai, T.; Yu, J.; Hossain, M.B. Microplastic contamination in some popular seafood fish species from the northern Bay of Bengal and possible consumer risk assessment. Food Control 2025, 171, 111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, H.; Dutta, J.; Karnwal, A.; Kumar, G. Microplastic contamination in fish: A systematic global review of trends, health risks, and implications for consumer safety. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 219, 118279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Vieira, L.R.; Branco, V.; Figueiredo, N.; Carvalho, F.; Guilhermino, L.; Canning-Clode, J. Microplastics in Wild Fish from North East Atlantic Ocean and Their Potential for Causing Harm. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.M.; Nowack, B.; Mitrano, D.M. Polyester Textiles as a Source of Microplastics from Household Washing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7036–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucă, A.M.; Stoica, E.; Barbeș, L. First Report of Microplastic Ingestion and Bioaccumulation in Commercially Valuable European Anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus, Linnaeus, 1758) from the Romanian Black Sea Coast. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piarulli, S.; Sørensen, L.; Amat, L.M.; Farkas, J.; Khan, E.A.; Arukwe, A.; Gomiero, A.; Booth, A.M.; Gomes, T.; Hansen, B.H. Particles, chemicals or both? Assessing the drivers of the multidimensional toxicity of car tire rubber microplastic on early life stages of Atlantic cod. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 138699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, A.L.; Frias, J.; Pedrotti, M.L. Tardigrades in the marine plastisphere: New hitchhikers surfing plastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 200, 116071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbumani, S.; Kakkar, P. Ecotoxicological Effects of Microplastics on Biota: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 14373–14396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgeman, L.; Cimbalo, A.; López-Rodríguez, D.; Pamies, D.; Frangiamone, M. Exploring Toxicological Pathways of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Insights from Animal and Cellular Models. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 137795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.; Lee, Y.J.; Sung, S.E.; Kang, K.K.; Park, J.W.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, S. Exacerbation of polyethylene microplastics in animal models of DSS-induced colitis through damage to intestinal epithelial cell conjunctions. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2025, 8, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Maimaiti, Z.; Fu, J.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.Y.; Shi, Y.; Hao, L.B.; Chen, J.Y.; Xu, C. Identification and analysis of microplastics in human lower limb joints. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.S.; Ullah, H.; Faruk, O.; Simon, E.; Czédli, H. Role of microplastics in global warming and climate change: A review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, F.L.; Okoye, F.; Onyedibe, V.; Hamza, R.; Dhar, B.R.; Elbeshbishy, E. Climate change interaction with microplastics and nanoplastics pollution. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, H.L.; Ariyasena, D.D.; Orris, J.; Freedman, M.A. Pristine and Aged Microplastics Can Nucleate Ice through Immersion Freezing. ACS EST Air 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ni, B.-J.; Liu, Y. Smaller sizes of polyethylene terephthalate microplastics mainly stimulate heterotrophic N2O production in aerobic granular sludge systems. Water Res. X 2025, 27, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, S.; Deng, J. Effect of microplastics exposure on the photosynthesis system of freshwater algae. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 374, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Ye, S.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, L.; Tang, W.; Wen, X.; Liu, S. Can microplastics pose a threat to ocean carbon sequestration? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Fan, Z. Growth inhibition, toxin production and oxidative stress caused by three microplastics in Microcystis aeruginosa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Fonseca, E.M.; Gaylarde, C.C. Climate Change and Microplastics: A Two-Way Interaction. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplast. 2025, accepted for publication.

- Chu, X.; Zheng, B.; Li, Z.; Cai, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, P.; Tian, Y. Occurrence and Distribution of Microplastics in Water Supply Systems: In Water and Pipe Scales. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 150004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.; Kerpen, J.; Prediger, J.; Barkmann, L.; Müller, L. Determination of the microplastics emission in the effluent of a municipal wastewater treatment plant using Raman microspectroscopy. Water Res. X 2019, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shao, Y.; Qin, S.; Wang, Z. Future directions of sustainable resource utilization of residual sewage sludge: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płonka, I.; Kudlek, E.; Pieczykolan, B. Municipal sewage sludge disposal in the Republic of Poland. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lue-Hing, C. (Ed.) Municipal Sewage Sludge Management: A Reference Text on Processing, Utilization and Disposal, Volume IV; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, F.; Kersten, A.; Schabel, S.; Kerpen, J. Microplastics in German paper mills’ wastewater and process water treatment plants: Investigation of sources, removal rates, and emissions. Water Res. 2025, 271, 123016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Nghiem, L.D.; Wei, Y. Enhanced Microbial Strategies to Mitigate Microplastic Transfer via Composting to Agricultural Ecosystems—A Short Review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembo, R.O.; Phiri, Z.; Madikizela, L.M.; Kamika, I.; De Kock, L.A.; Msagati, T.A. Global Research Trends in Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics: A Bibliometric Perspective. Microplastics 2025, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollofrath, D.; Kuhlmann, F.; Requardt, S.; Krysiak, Y.; Polarz, S. A self-regulating shuttle for autonomous seek and destroy of microplastics from wastewater. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyah, Y.; El Messaoudi, N.; Benjelloun, M.; El-Habacha, M.; Georgin, J.; Angeles, G.H.; Knani, S. Comprehensive review on advanced coordination chemistry and nanocomposite strategies for wastewater microplastic remediation via adsorption and photocatalysis. Surfaces Interfaces 2025, 106955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, N.S.; Patra, A.; Ghosh, A.R. Microplastics degradation and remediation techniques. In Microplastics in the Terrestrial Environment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 136–159. ISBN 9781032684574. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Mateo, C.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Harings, J.A.; Blank, L.M. Enzymatic remediation of polyester microfibers in sewage sludge and green compost samples. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Shin, G.; Lee, M.; Koo, J.M.; Jeon, H.; Ok, Y.S.; Hwang, D.S.; Hwang, S.Y.; Oh, D.X.; Park, J. Biodegradable chito-beads replacing non-biodegradable microplastics for cosmetics. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 6953–6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, A.; Malafeev, K.V.; Scarfato, P.; Incarnato, L. Generation of Microplastics from Biodegradable Packaging Films Based on PLA, PBS and Their Blend in Freshwater and Seawater. Polymers 2024, 16, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.B.; Wang, P.Y.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.T.; Mei, F.J.; Wang, W.Y.; Wang, Y.B.; Fang, X.W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.L. Can biodegradable film replace polyethylene film to obtain similar mulching effects on soil functions and maize productivity in irrigation region? A three-year experimental appraisal. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putar, U.; Fazlić, A.; Brunnbauer, L.; Novak, J.; Jemec Kokalj, A.; Imperl, J.; Kučerík, J.; Procházková, P.; Federici, S.; Hurley, R.; Sever Škapin, A. Investigating aquatic biodegradation and changes in the properties of pristine and UV-irradiated microplastics from conventional and biodegradable agricultural plastics. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 376, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Lackner, M. Biodegradable Microplastics: Environmental Fate and Persistence in Comparison to Micro- and Nanoplastics from Traditional, Non-Degradable Polymers. Macromol 2025, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Tong, Y.; Ni, B.J.; Liu, Y. Biodegradable Microplastics Aggravate Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Urban Lake Sediments More Severely than Conventional Microplastics. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options. OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [CrossRef]