3.2. Quantification of MPs and Fibers in the Air

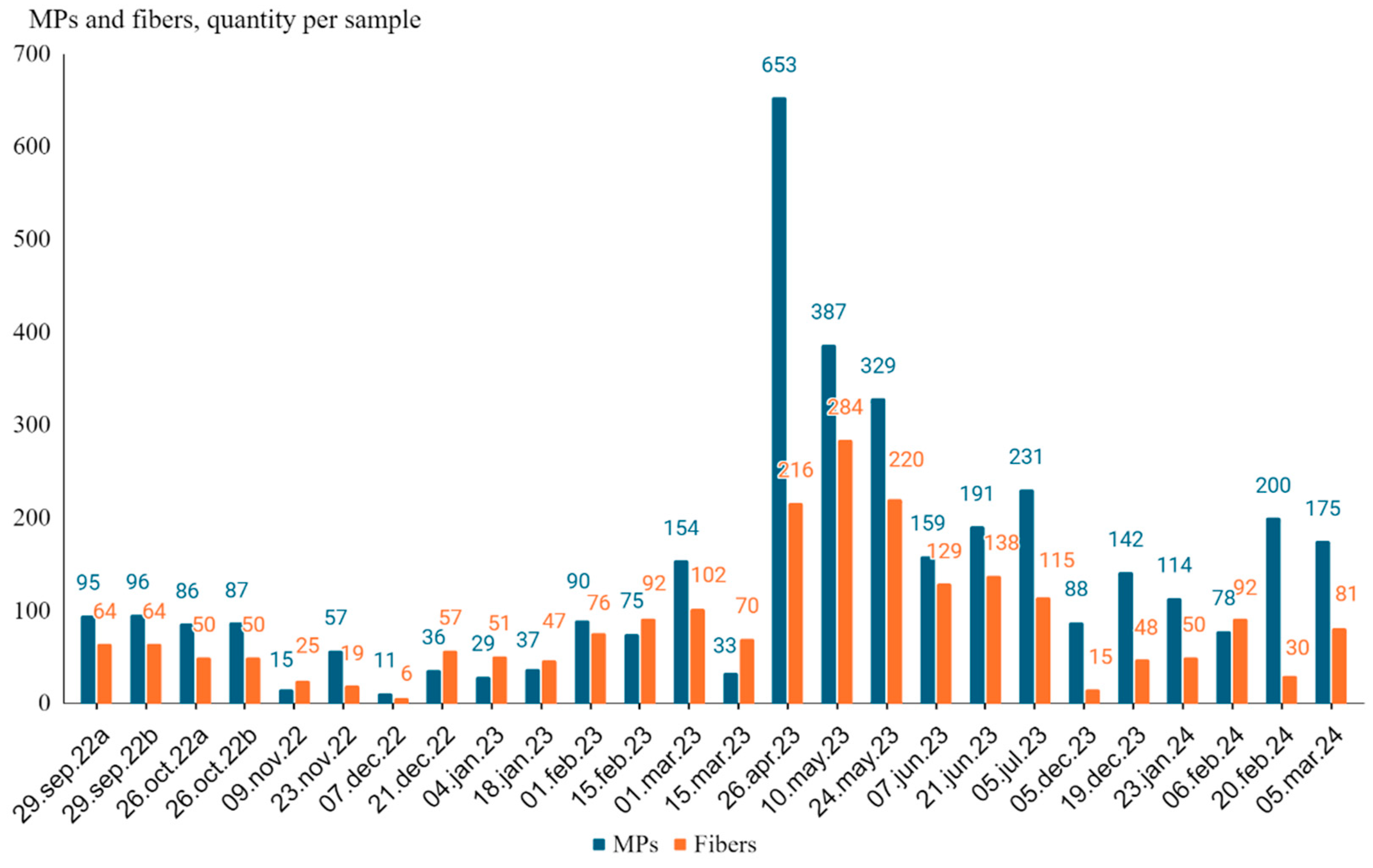

Results of the quantification of MPs and fibers by optical microscopy are represented in

Figure 2, and show the distribution of total microplastics and fibers in the samples collected from September 2022 to March 2024. The number of microplastics collected varied considerably over this period, with the highest count recorded on April 26, 2023 (653 particles) and the lowest on December 7, 2022 (11 particles). Similarly, fiber counts showed variability along the study period, with the highest number recorded on May 10, 2023 (284 fibers), and the lowest also on December 7, 2022 (6 fibers). Several notable peaks in microplastic counts were observed, including 387 particles on May 10, 2023, and 329 particles on May 24, 2023. Fiber counts also displayed peaks in these dates and generally following the same trends, with the most fibers collected on May 10, 2023 (284 fibers), and on May 24, 2023 (220 fibers).

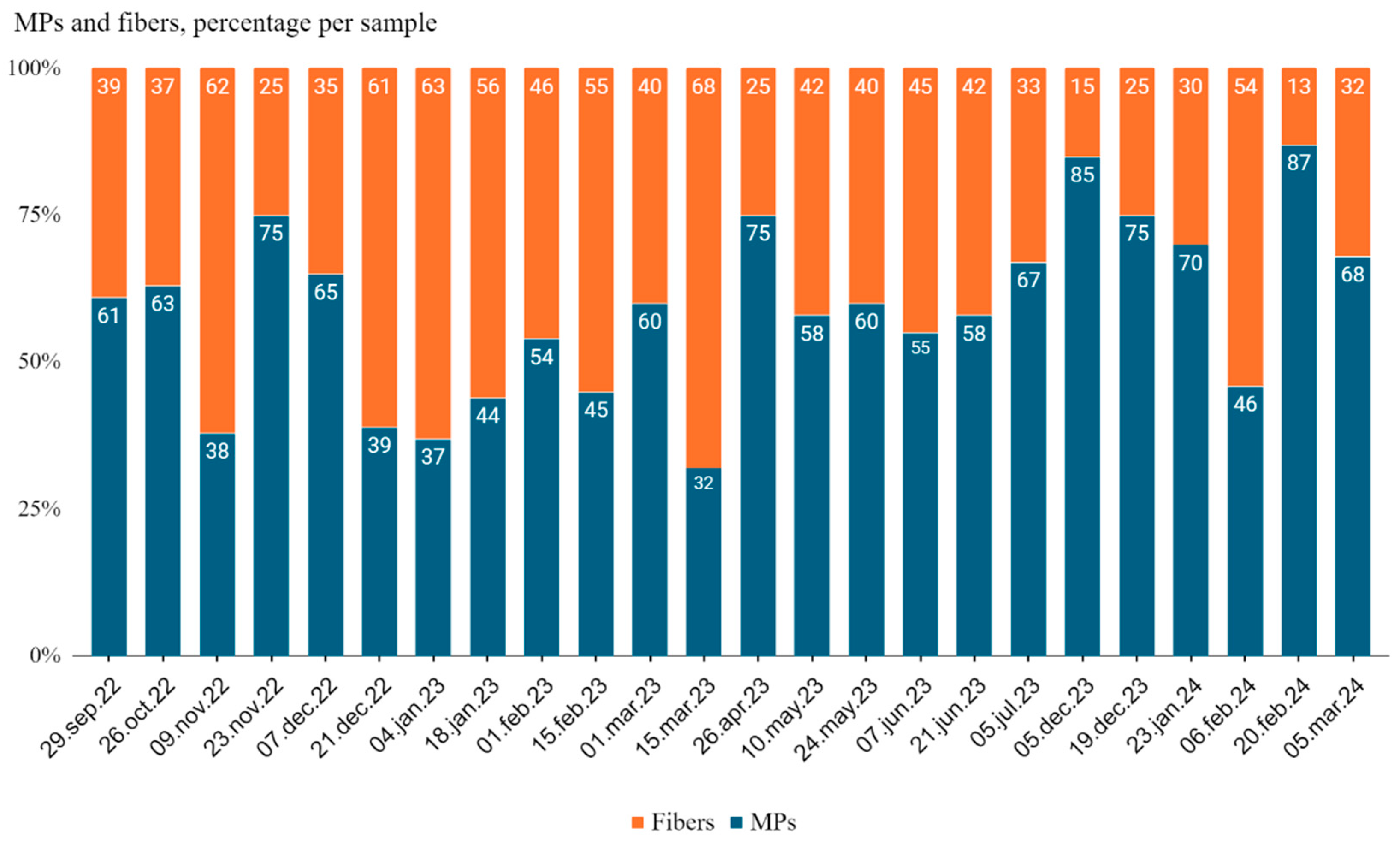

When viewed as percentages, the relative proportions of microplastic particles to fibers also showed notable fluctuations (

Figure 3). Microplastic particles ranged between 32% to 87% of the total particles, while fibers ranged from 13% to 68%. Notable peaks in microplastic particle counts were observed in April and May 2023, but the highest percentage (87%) was recorded on February 20, 2024. The highest fiber percentage (68%) occurred on March 15, 2023, indicating the existence of periods where fibers were more prevalent than microplastics.

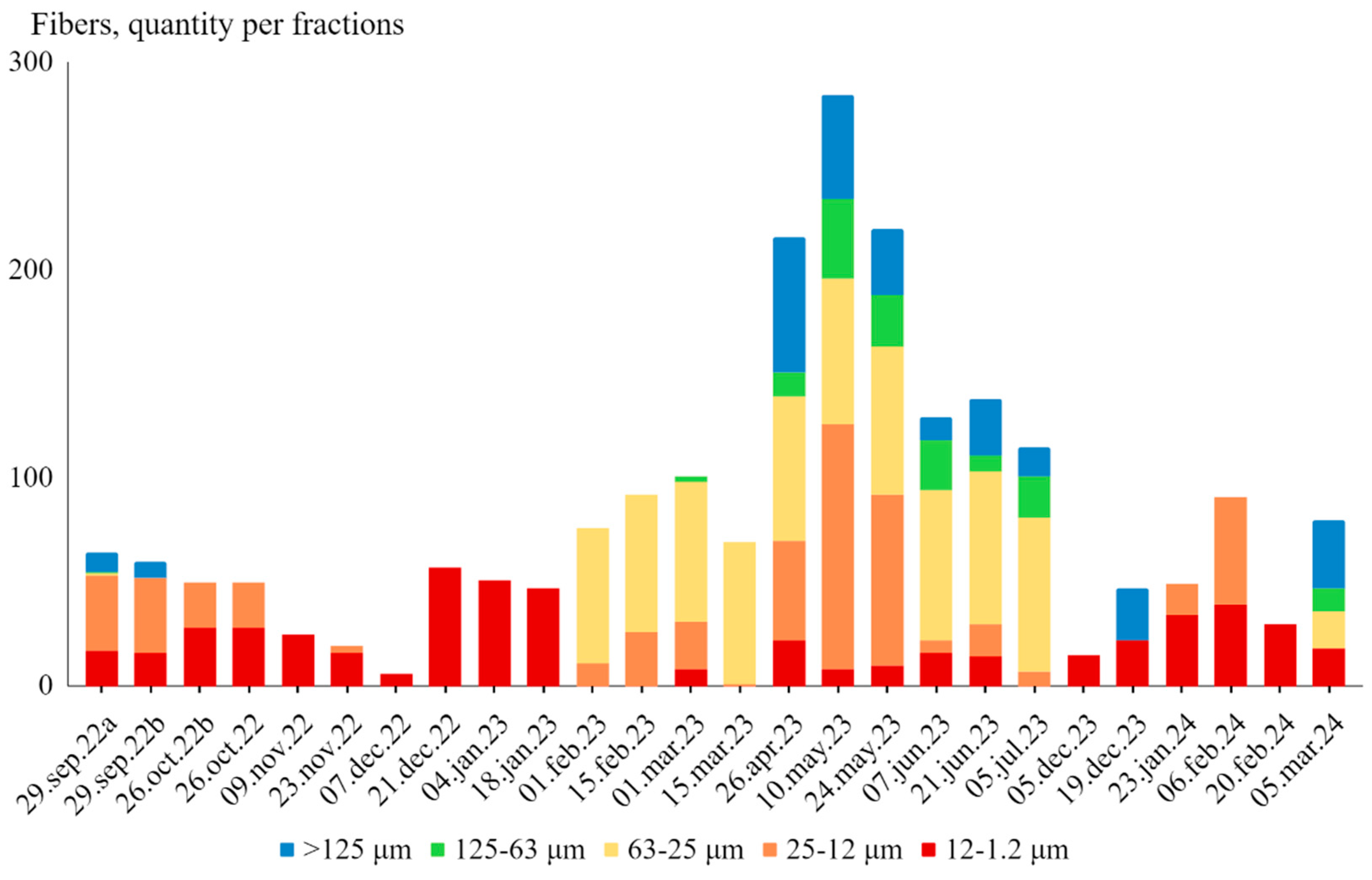

The data for fiber counts by size fraction across the various samples from September 2022 to March 2024 shows distinct distribution patterns among different size ranges (

Figure 4). Fibers were encountered into the five size fractions: >125 μm, 125-63 μm, 63-25 μm, 25-12 μm, and 12-1.2 μm. The majority of fibers were found in the 25-12 μm and 12-1.2 μm size fractions, with considerable fewer fibers in the bigger size fractions (>125 μm and 125-63 μm). For the >125 μm size fraction, fiber counts were generally low, with notable peaks on April 26, 2023 (65 fibers), and May 10, 2023 (50 fibers). Many samples recorded zero fibers in this size range. Similarly, the 125-63 μm size fraction also showed low counts with occasional peaks, such as May 10, 2023 (38 fibers). The 63-25 μm size fraction had moderate fiber counts with peaks between February 01, 2023 and July 05, 2023 (65-74 fibers). The 25-12 μm size fraction consistently showed higher counts, particularly notable on May 10, 2023 (118 fibers), and May 24, 2023 (82 fibers). Lastly, the 12-1.2 μm size fraction was the most consistently populated, with high counts across multiple dates, such as December 21, 2022 (57 fibers), and the lowest at December 07, 2022 (6 fibers).

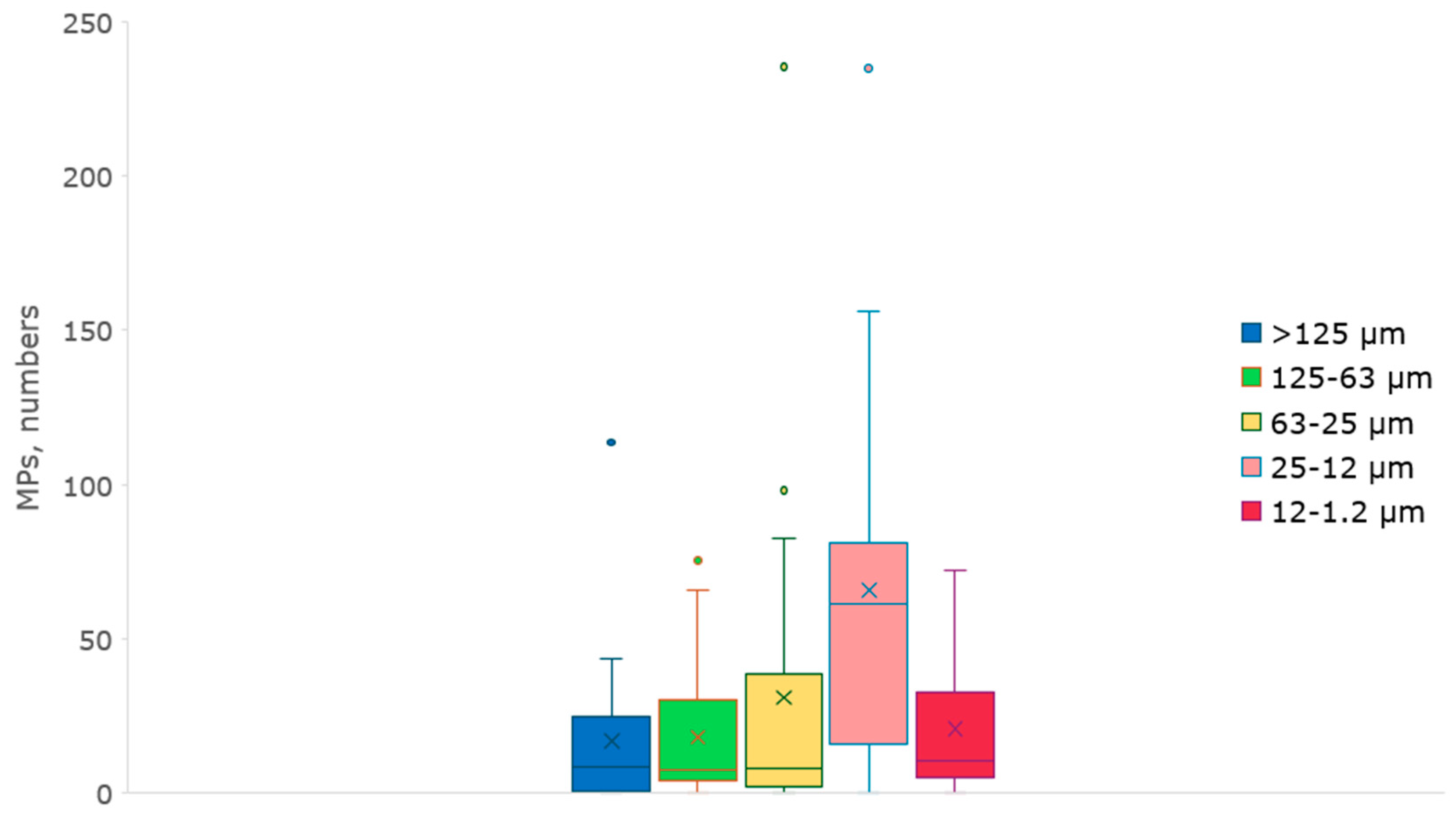

The analysis of microplastic particles contamination across different size fractions (>125 μm, 125-63 μm, 63-25 μm, 25-12 μm, 12-1.2 μm) revealed considerable variability and different trends (

Figure 5). The data shows that the mean particle counts decrease with increasing size fraction: 17 particles for >125 μm, 18 particles for 125-63 μm, 31 particles for 63-25 μm, 66 particles for 25-12 μm, but except for 12-1.2 μm, mean 21 particles. These results indicate a higher prevalence of smaller microplastic particles, likely more pervasive due to degradation processes. The variability and presence of outliers suggest localized dates of high contamination, pointing to the influence of specific environmental factors or sources. The absence of outliers in the smallest size fraction (12-1.2 μm) suggests a more uniform distribution of microplastics in this category. For the >125 μm fraction, most data falls from 0 to 61 particles, with a mean of 17 particles and one expressive outlier at 114 particles. It suggests that while most samples contain a moderate number of larger microplastic particles, there are occasional occurrence of considerable highly counts, possibly due to localized contamination. The data shows a similar trend in the 125-63 μm fraction, with a mean of 18 particles and a prominent outlier at 75 particles. This indicates that microplastics in this size range are less prevalent than larger particles. However, again, localized factors can cause high variability. The 63-25 μm category shows a broader range of particle counts with a mean of 31 particles and notable outliers at 98 and 235 particles. The more substantial number of outliers and higher variability suggest that this size fraction is more susceptible to environmental factors that can lead to spikes in microplastic counts. For the 25-12 μm fraction, the mean count of 66 particles and an outlier of 235 particles indicate a higher prevalence of microplastics in this size range. This could be because smaller particles are more likely to be produced and persist in the air, potentially accumulating from various sources. The 12-1.2 μm fraction, with a mean of 21 particles and no outliers, shows the smallest range of variability. The absence of outliers might suggest a more uniform distribution, constant affluent taxes, and sources of high microplastic counts in this size range. Generally, there appears to be fluctuation but potentially increasing trends in microplastic concentrations over the sampling period.

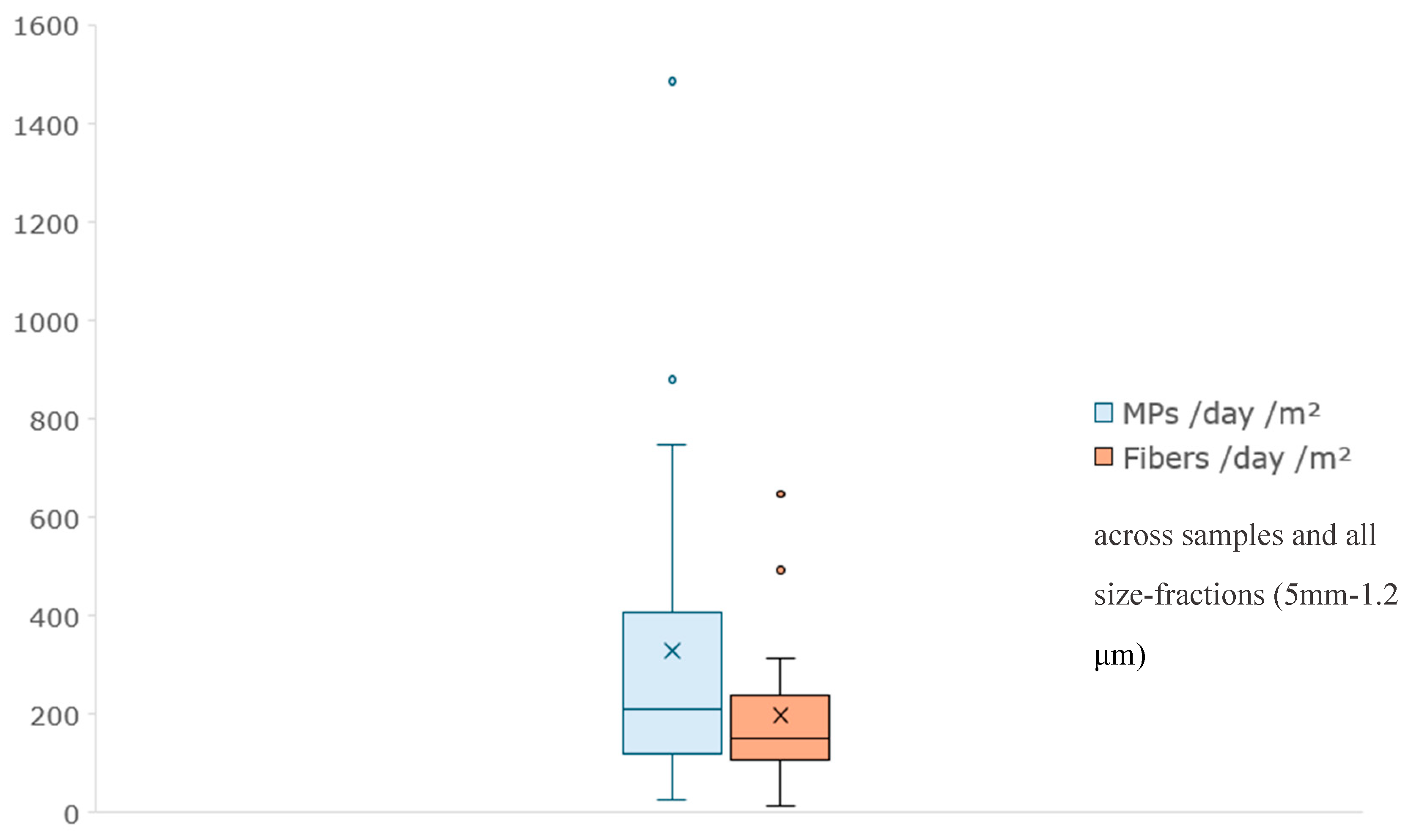

The box plot in

Figure 6, visually represents the distribution of MPs and fibers per day and per square meter across the samples collected from September 29, 2022, to March 5, 2024. The numbers of MPs/day/m² range from 26to 1484, with mean (329), median (211), quartiles (119 and 407), and outliers (879 and 1484) are identified for each time point, revealing trends in microplastic pollution over time. There is notable variation in microplastic concentrations across different sampling dates. For instance, the highest concentration was observed on April 26, 2023 (1484 MPs/day/m²), while the lowest was on December 7, 2022 (26 MPs/day/m²). In the previous box-plot analysis (

Figure 5), each fraction, excluding the 25-12 μm, exhibited a notable increase towards the upper quartile of the plot. Similarly, we observe this trend in the current box plot depicting MPs per day per square meter for the total fraction across all samples. There is a clear tendency towards higher concentrations over the sampling period, indicating a potential increase in microplastic levels.

The numbers of fibers/day/m² range from 14 to 646, with mean (197), median (150), quartiles (108 and 239), and two outliers (492 and 646). Generally, there appears to be fluctuations but potentially increasing trends in fibers concentrations over the sampling period too.

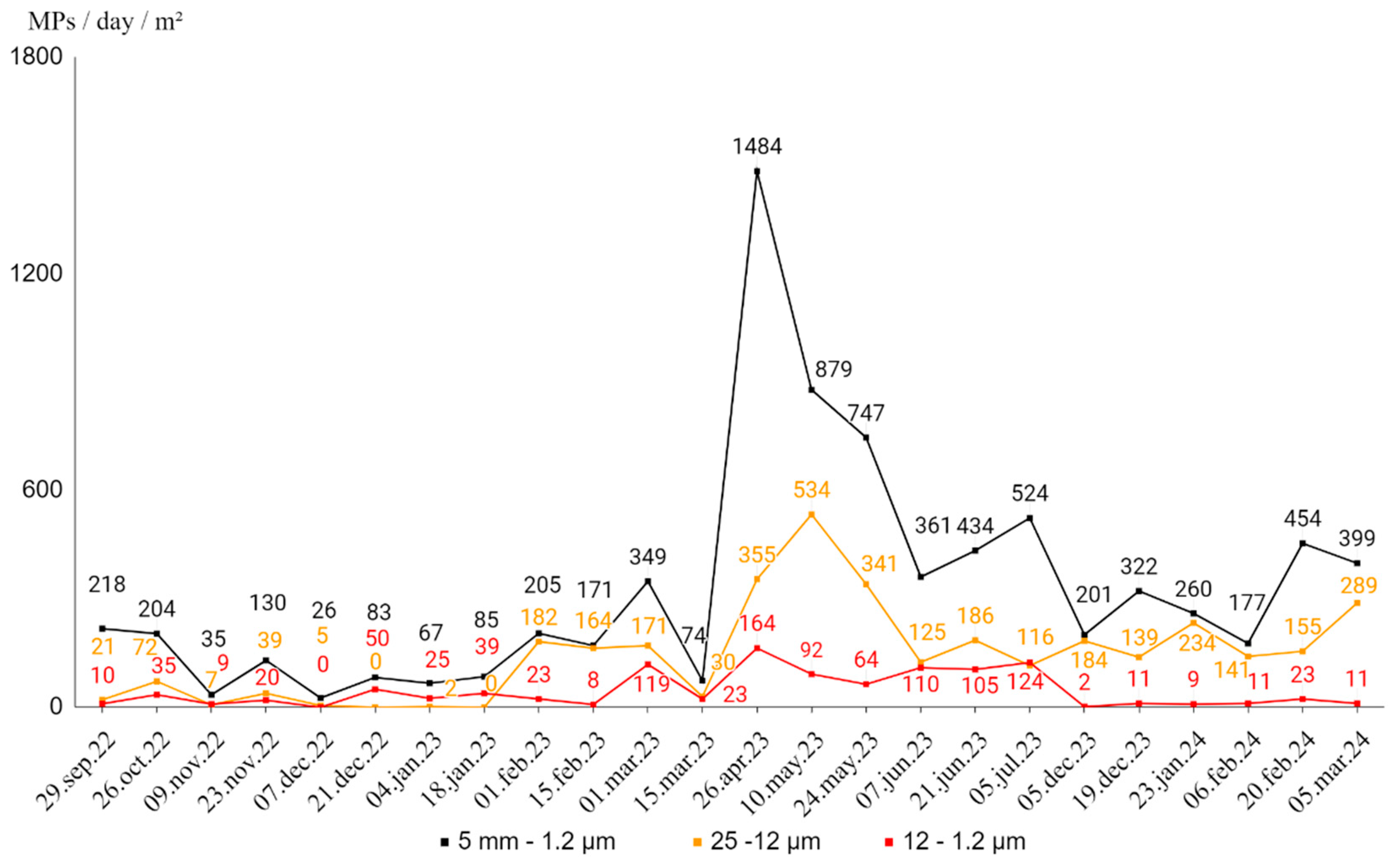

The counts of MPs/day/m² for total of fractions (5 mm-1.2 μm) and each fraction (25-12 μm and 12-1.2 μm) vary considerable over time, specific periodic dates with unusually high MPs counts might suggest episodic pollution events, seasonal effects or other influencing factors (

Figure 7).

The counts of microplastics within the two lowest size fractions (25-12 μm and 12-1.2 μm) calculated per day and per meter square (MPs/day/m2) over the sampling period reveals notable variability in microplastic concentration across both size categories and sampling dates. MPs in the size-fraction 25-12 μm are generally more abundant than smaller ones, except for the period from December 7, 2022 to January 17, 2023. Overall, the data does not indicate much consistent proportions, trends, or relationships between the different fractions of MPs. The counts of MPs within for total of fractions (5 mm-1.2 μm) and each fraction (25-12 μm and 12-1.2 μm) vary independently and do not exhibit a clear pattern when compared to one another. Although for size-fractions 25-12 μm, even with variability, attend increasing trend of represented values.

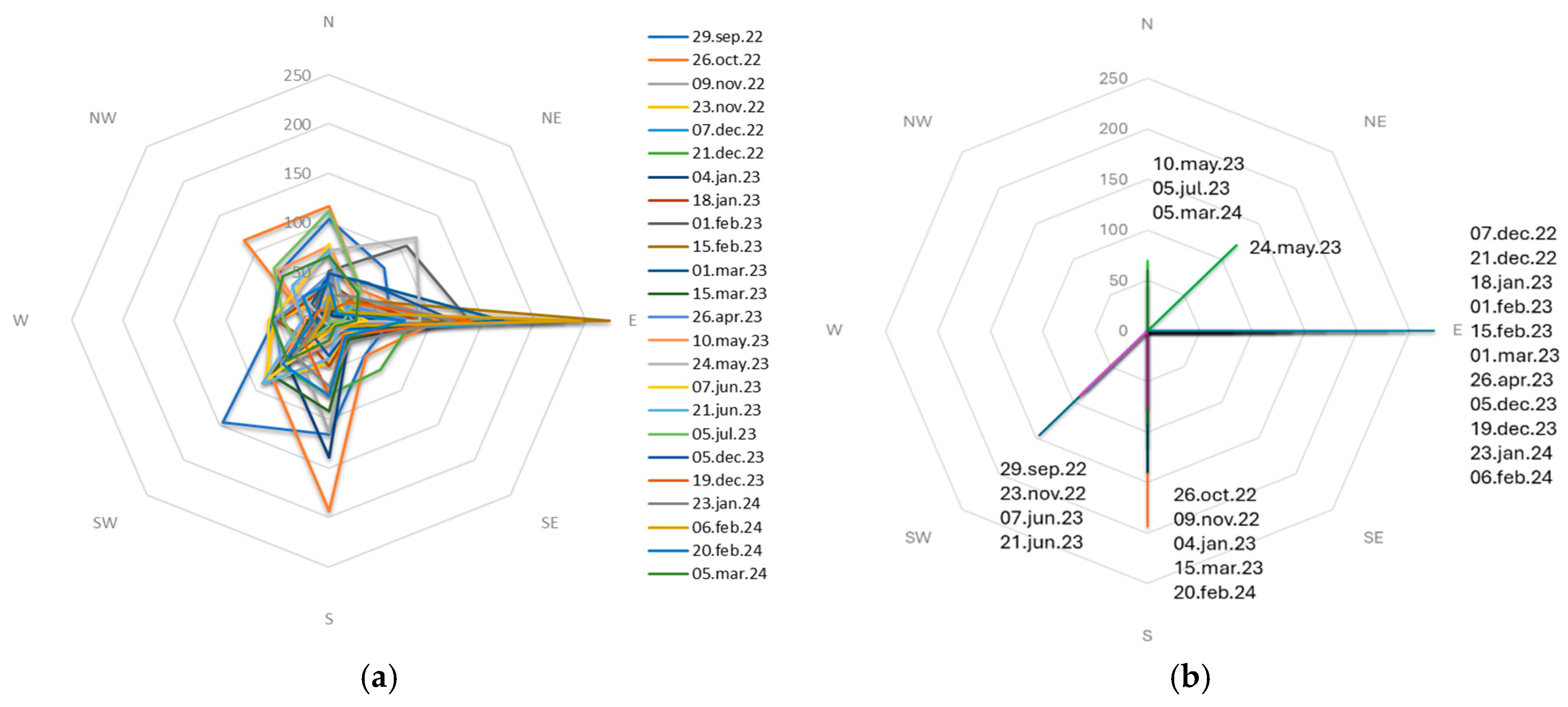

The wind rose data, collected from 29 September 2022 to 5 March 2024, illustrates the distribution and frequency of wind directions over the study period (

Figure 8a). The observations reveal that the wind predominantly blew from the East (E), South(S), Southwest (SW) and North (N) directions. The analysis of predominant wind directions for each sample period from 29 September 2022 to 5 March 2024 revealed distinct patterns (

Figure 8b). The data indicate that the predominant wind direction varied considerably across the different sampling dates, reflecting the dynamic nature of local meteorological conditions. Throughout the study, easterly (E) winds were the most frequently predominant direction, especially notable on February 15, 2023, with a maximum count of 273 occurrences. This trend continued with significant instances on February 6, 2024 (245), December 7, 2022 (228), and March 1, 2023 (169). Southern (S) winds were predominant on several occasions with the most significant instance on October 26, 2022 (193) and notable occurrences on January 4, 2023 (139) and November 9, 2022 (114). In contrast, the northern (N) winds were predominantly observed on fewer occasions, including July 5, 2023 (112), May 10, 2023 (76), and March 5, 2024 (66). Moreover southwestern (SW) winds were primarily dominant on September 29, 2022, with 146 occurrences, on June 21, 2023, with 91 instances, on November 23, 2022 with 87 instances and on June 7, 2023, with 82 instances. These instances underscore the variability and occasional prominence of S and SW winds in the study area. Interestingly, there were no instances of predominant winds from the southeastern (SE), western (W), or northwestern (NW) directions during the sampling periods, indicating a limited influence from these directions within the observed timeframe. The northeastern (NE) winds were predominant on May 24, 2023, with 120 instances, marking a unique occurrence where NE winds dominated.

Overall, the data demonstrate that while easterly, southerly and southwesterly winds were more consistently predominant, there was considerable variability in wind direction, with certain periods experiencing strong influences from the northerly, northwesterly and northeasterly winds. This variability is crucial for understanding the dispersion patterns of airborne materials, including microplastics and fibers, within the study region.

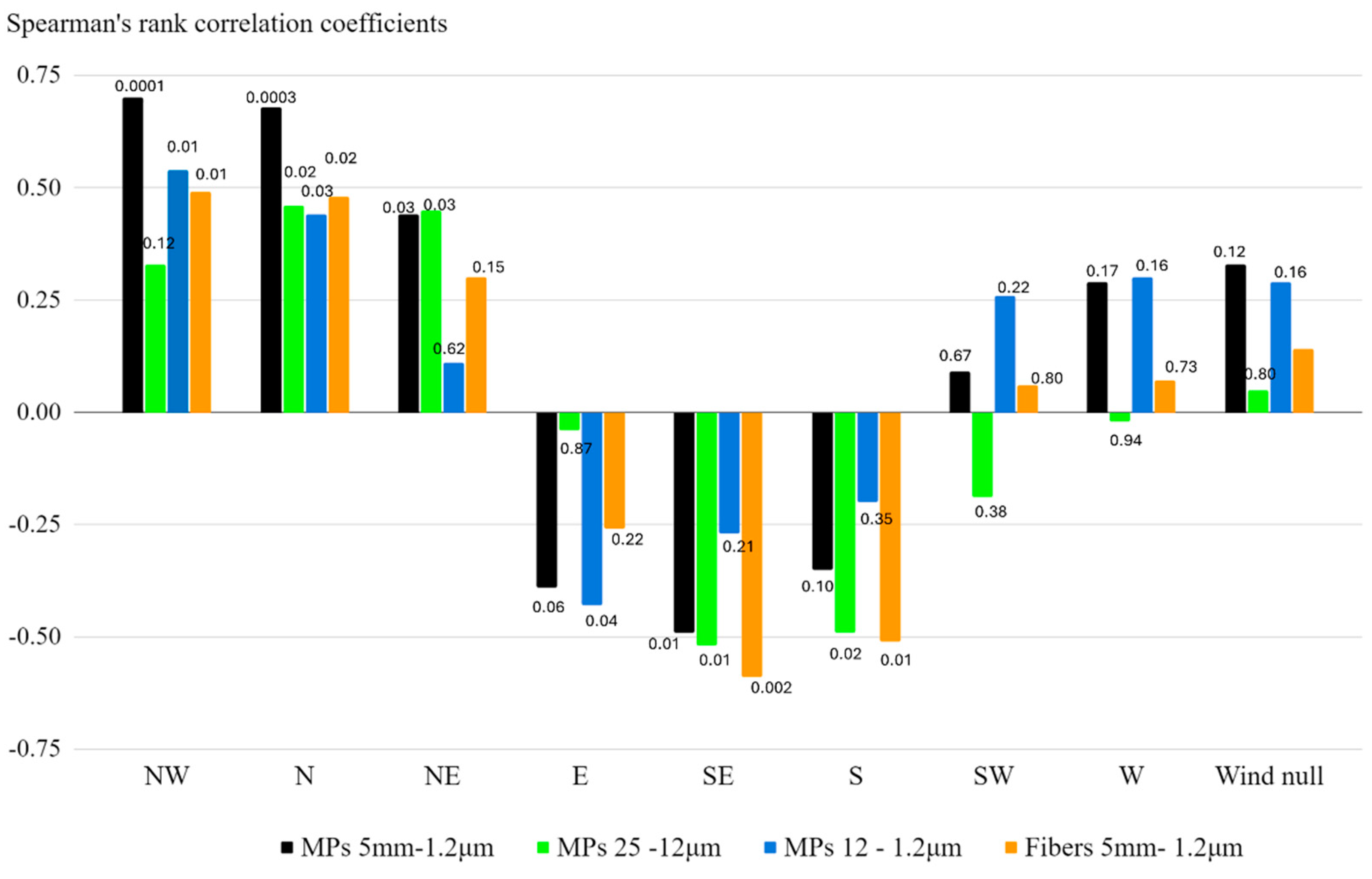

The analysis of Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (r

s) and associated p-value reveals that different wind directions have distinct impacts on the concentration of microplastics (MPs) and fibers in the environment (

Figure 9). For Northwest (NW) and North (N) winds, strong positive correlations were observed between NW and N winds and microplastics per day and per square meter (MPs/day/m

2), particularly for the total MPs fractions (5 mm-1.2 μm), with correlation coefficients of 0.70 and 0.68, respectively. These correlations are highly significant, with p-values of 0.0001 and 0.001, indicating that stronger winds from these directions are associated with increased levels of MPs. For Northeast (NE) winds, moderate positive correlations were found, particularly with the MPs fraction 25-12 μm and the total MPs fractions (5 mm-1.2 μm), with correlation coefficients of 0.45 and 0.44, respectively. The significance of these relationships is supported by p-values of 0.03, suggesting that NE winds may contribute to higher concentrations of these particles.

In contrast, Southern (S) and Southeast (SE) winds tend to have negative correlations with most MPs particle sizes and fibers. The strongest negative correlations were found with fibers in the 5 mm-1.2 μm range (-0.51 and -0.59, respectively), with significant p-values of 0.01 and 0.002. This negative correlation suggests a moderate inverse relationship between these two variables, indicating that stronger winds from the S and SE directions are likely to reduce the concentrations of fibers and MPs. Eastern (E) winds also showed negative correlations, particularly with the MPs fraction 12-1.2 μm (-0.43) and the total MPs fractions 5 mm-1.2 μm (-0.39). The p-values are 0.04 and 0.06, suggesting a potential, though less pronounced, inverse relationship between E winds and microplastic concentrations. Winds from the West (W), Southwest (SW), and periods with no significant wind (Null) generally showed non-significant correlations (p-values above 0.05), suggesting that these directions may have a less consistent influence on microplastic levels.

These findings suggest that wind direction plays a crucial role in influencing the distribution of microplastics and fibers in the environment. Northern and northeastern winds generally increase particle concentrations, while southern and eastern winds may contribute to their reduction.

During the analysis of the relationship between meteorological factors and the concentration of microplastics, an assessment was conducted to determine the presence of linearity between the independent variables (meteorological factors) and the dependent variable (MPs). Despite thorough evaluation, no significant linear relationships were identified. Given the absence of linearity, traditional methods like Multiple Correlation Analysis (MCA), which rely on linear associations between variables, were deemed unsuitable for this dataset. As a result, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed as an alternative approach. PCA does not require linearity and is effective in reducing dimensionality by identifying the principal components that explain the most variance in the data. This technique allowed for the exploration of complex, non-linear relationships between the meteorological factors and microplastic concentrations, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying patterns in the data.

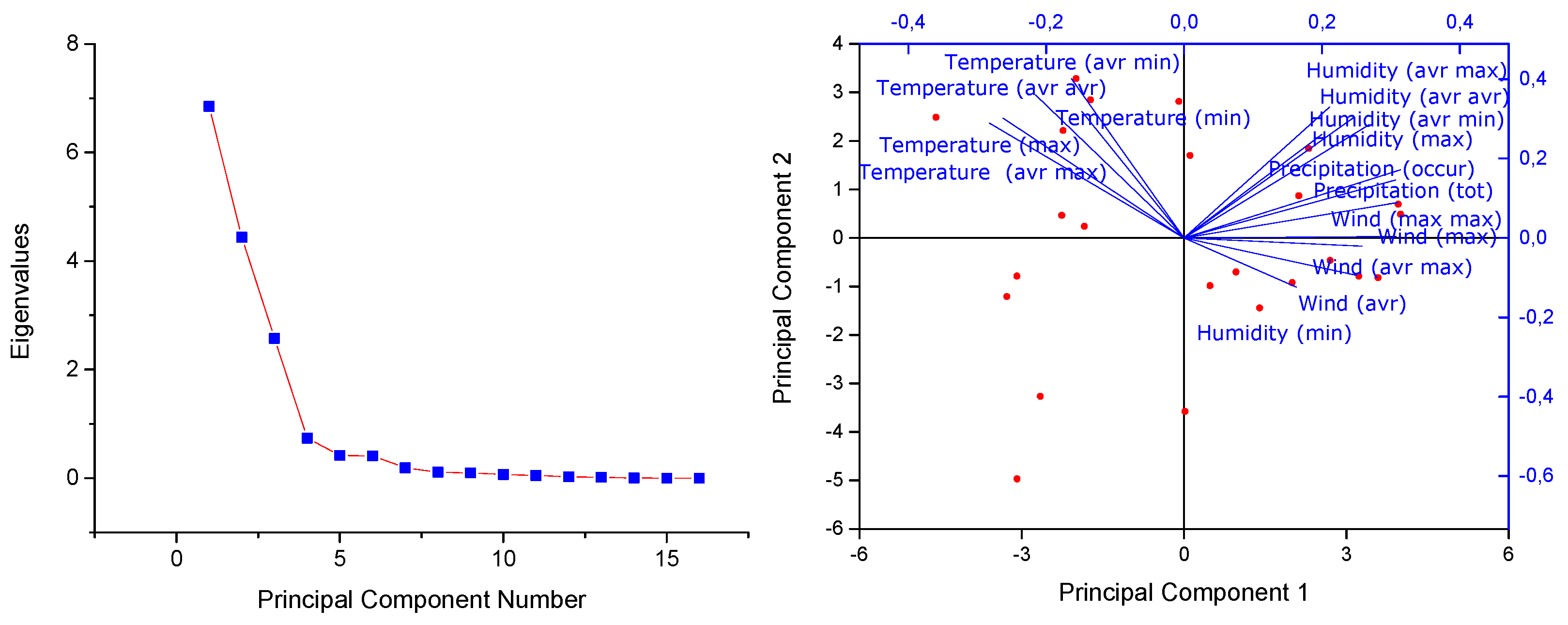

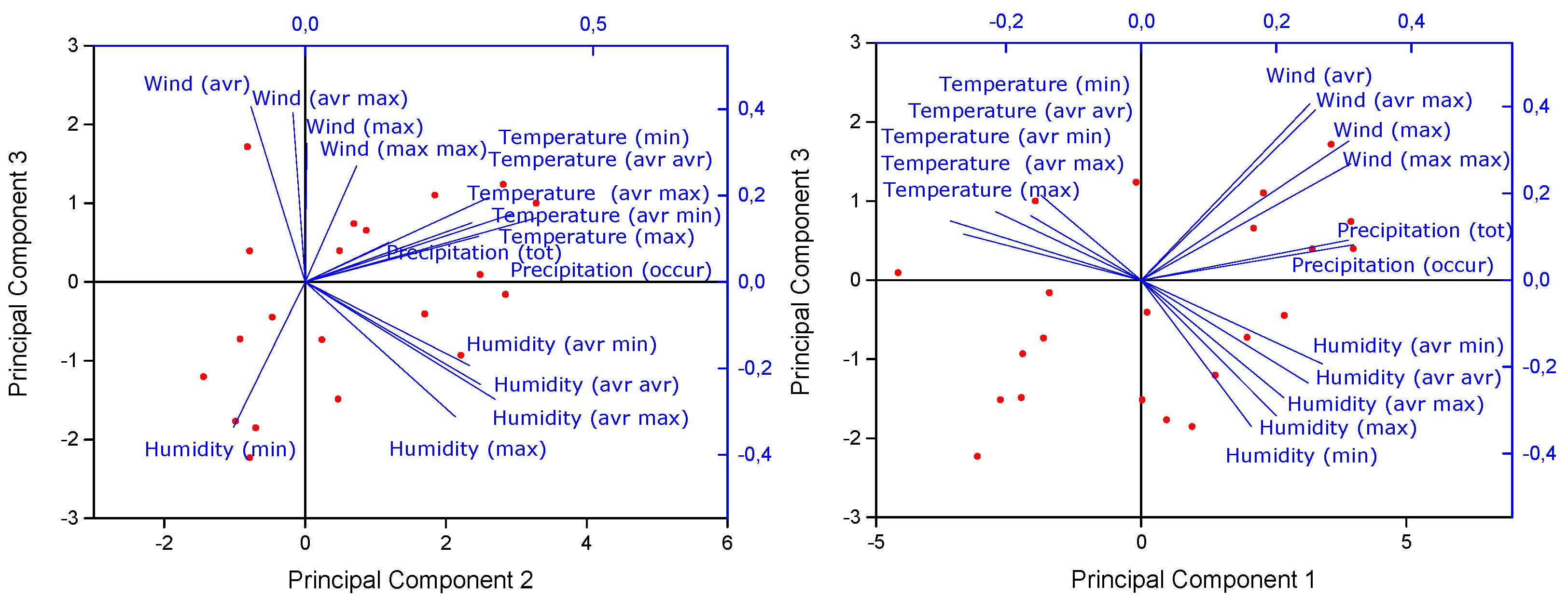

PCA was employed to investigate the relationships between MPs concentrations (MPs/day/m²) and various meteorological factors (

Table S3) (Wind maximum during the days of collecting of each sample (Wind max), Wind average during the days of collecting of each sample (Wind avr), Wind maximum of maximum in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Wind max max), Wind average of maximum in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Wind avr max), Precipitation total during the days of collecting of each sample (Precipitation tot), Occurrence number of precipitation during the days of collecting of each sample (Precipitation occur), Temperature average of maximum in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Temperature avr max), Temperature average of minimum in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Temperature avr min), Temperature average of average in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Temperature avr avr), Temperature maximum during the days of collecting of each sample (Temperature max), Temperature minimum during the days of collecting of each sample (Temperature min), Humidity average of maximum in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Humidity avr max), Humidity average of minimum in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Humidity avr min), Humidity average of average in each day during the days of collecting of each sample (Humidity avr avr), Humidity maximum during the days of collecting of each sample (Humidity max), Humidity minimum during the days of collecting of each sample (Humidity min). The analysis identified key components that explain the majority of the variance in the dataset, offering insights into the impact of different environmental variables on microplastic levels (

Figure 10). The PCA revealed 16 principal components, with the first three components accounting for a substantial portion of the total variance—42.80%, 27.74%, and 16.09%, respectively. Collectively, these three components explain 86.64% of the variance, indicating that they capture the most significant patterns in the data. The first principal component (PC1) is strongly associated with wind speed and precipitation variables, as evidenced by high positive loadings for factors such as "Wind max," "Precipitation tot," and "Precipitation occur." These results suggest that PC1 reflects the combined influence of wind speed and precipitation on microplastic concentrations. Conversely, temperature-related variables like "Temperature avr max" and "Temperature avr avr" show negative loadings, indicating an inverse relationship with PC1. The second principal component (PC2) is dominated by temperature and humidity factors, with significant positive loadings for "Temperature avr min," "Temperature avr avr," and "Humidity avr max." This suggests that PC2 primarily captures the impact of temperature and humidity on microplastic levels, with a lesser influence from wind speed variables, as indicated by the small negative loading for "Wind avr." The third principal component (PC3) primarily reflects variations in wind speed, with high positive loadings for "Wind avr," "Wind max," and "Wind avr max." While temperature variables like "Temperature avr min" and "Temperature avr avr" contribute to PC3, they do so to a lesser extent. In contrast, humidity variables exhibit negative loadings, particularly "Humidity av max" and "Humidity min," indicating an inverse relationship with this component.

In summary, the PCA results reveal distinct patterns in how meteorological factors influence microplastic concentrations. PC1 highlights the importance of precipitation and wind speed, suggesting that these conditions are closely associated with higher microplastic levels. PC2 underscores the role of temperature and humidity in shaping microplastic distributions, while PC3 emphasizes the primary role of wind speed in this context. These findings provide a nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between meteorological variables and microplastic concentrations, offering a foundation for further exploration of their environmental impact.

Principal Component Regression (PCR) was conducted to explore the relationship between microplastics concentrations and the principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) derived from meteorological data. Each principal component was analyzed separately to determine its contribution to explaining the variance in microplastics concentrations. The regression results for PC1 are as follows: Slope (m): 2.999 (Standard Error: 1.056); Intercept (b): 1.737 (Standard Error: 0.865); R-squared (R²): 0.973; F-statistic: 15.723 (Degrees of Freedom: 7); Regression Sum of Squares: 22.377 Residual Sum of Squares: 0.623 The regression analysis for PC1 shows a significant positive relationship with microplastics concentrations. The high R-squared value of 0.973 indicates that PC1 explains approximately 97.3% of the variance in microplastics concentrations, suggesting a strong fit of the model. The F-statistic further confirms the statistical significance of the regression model. The positive slope indicates that higher PC1 scores are associated with increased microplastics concentrations. The regression results for PC2 are: Slope (m): -3.925 (Standard Error: 1.382); Intercept (b): 1.333 (Standard Error: 0.663); R-squared (R²): 0.973; F-statistic: 15.723 (Degrees of Freedom: 7); Regression Sum of Squares: 22.377; Residual Sum of Squares: 0.623 The analysis for PC2 shows a significant negative relationship with microplastics concentrations. The R-squared value remains high at 0.973, indicating that PC2 also explains 97.3% of the variance in microplastics concentrations. The negative slope suggests that as PC2 scores increase, the concentration of microplastics decreases. The model is statistically significant, as indicated by the F-statistic. The regression results for PC3 are: Slope (m): -1.451 (Standard Error: 0.511); Intercept (b): -1.114 (Standard Error: 0.554); R-squared (R²): 0.973; F-statistic: 15.723 (Degrees of Freedom: 7); Regression Sum of Squares: 22.377; Residual Sum of Squares: 0.623. The regression for PC3 reveals a significant negative association with microplastics concentrations. The R-squared value is consistently high at 0.973, showing that PC3 explains 97.3% of the variance in microplastics concentrations. The negative intercept of the regression, indicating that the baseline concentration of microplastics is negative when PC3 is zero, although this may not be physically meaningful and could be an artifact of the model. The negative slope indicates that higher PC3 scores are associated with lower microplastics concentrations. The statistical significance of the model is supported by the F-statistic.