1. Introduction

In order to survive in the fiercely competitive contemporary business environment, service organizations are gradually increasing the expectations placed upon frontline employees, who are a key determinant of service evaluations. (Madera, Taylor et al. 2020). Especially in high-contact service industry, customers evaluate or predict service quality by observing frontline employees’ emotions and behaviors during the service process(Shin, Hur et al. 2022). Emotional labor, as conceptualized in Hochschild’s seminal 1983 work, refers to the process by which employees manage and modulate their emotional expressions as an integral component of their service delivery roles(Hochschild 1983). It is acknowledged by both academic researchers and organizational managers that emotional labor exerts a significant influence on the formation of customer perceptions regarding service outcomes(Deng, Walter et al. 2017, Shin and Hur 2020). This consensus underscores the critical role that the regulation and expression of emotions by service employees play in shaping customer experiences, satisfaction levels, and overall evaluations of service quality. However, as two different strategies employees can take to regulate their emotions, deep and surface acting show incongruent effects on customer’s service evaluation. Andrzejewski and Mooney (2016) find that only genuine emotions displayed (deep acting) by employees can cause higher customer service evaluations. More recently, research conducted within the hotel industry by Wang (2019) demonstrates that deep acting and surface acting, as distinct forms of emotional labor, have divergent impacts on customers’ perceptions of service quality. Specifically, deep acting, which involves the genuine modulation of internal emotions to align with organizational expectations, is associated with positive effects on perceived service quality. Conversely, surface acting, characterized by the superficial display of emotions without underlying emotional change, exerts a negative influence on customers’ evaluations of service quality. These findings highlight the nuanced role of emotional labor strategies in shaping customer experiences and outcomes in the hospitality sector. Given incongruent results of how different emotional labor strategies affect service quality, the underlying mechanism that emotional labor affects service quality remains to be uncovered.

The emotions as social information model (EASI) provides a theoretical framework for understanding how emotions as social information are interpreted and used by observers (Van Kleef 2009). According to EASI model, interpersonal emotional influence operates through two primary pathways: inferential processes and affective reactions. Inferential processes involve observers interpreting emotional expressions to gain insights into the expresser’s thoughts, intentions, or the situational context, while affective reactions refer to the emotional responses elicited in observers, which subsequently shape their behavior (Van Kleef 2009). The EASI model has been extensively applied to elucidate various organizational phenomena, including conflict resolution, leadership effectiveness, and team performance(Liu, Song et al. 2017, Lee 2018, Van Kleef and Côté 2022). However, its application within the context of service interactions remains relatively underexplored. Only a limited number of studies, such as (Wang, Singh et al. 2017), have employed the EASI model to investigate how employees’ emotional expressions influence customers’ emotions and behavioral responses, highlighting a significant gap in the literature regarding the role of emotional dynamics in service encounters.

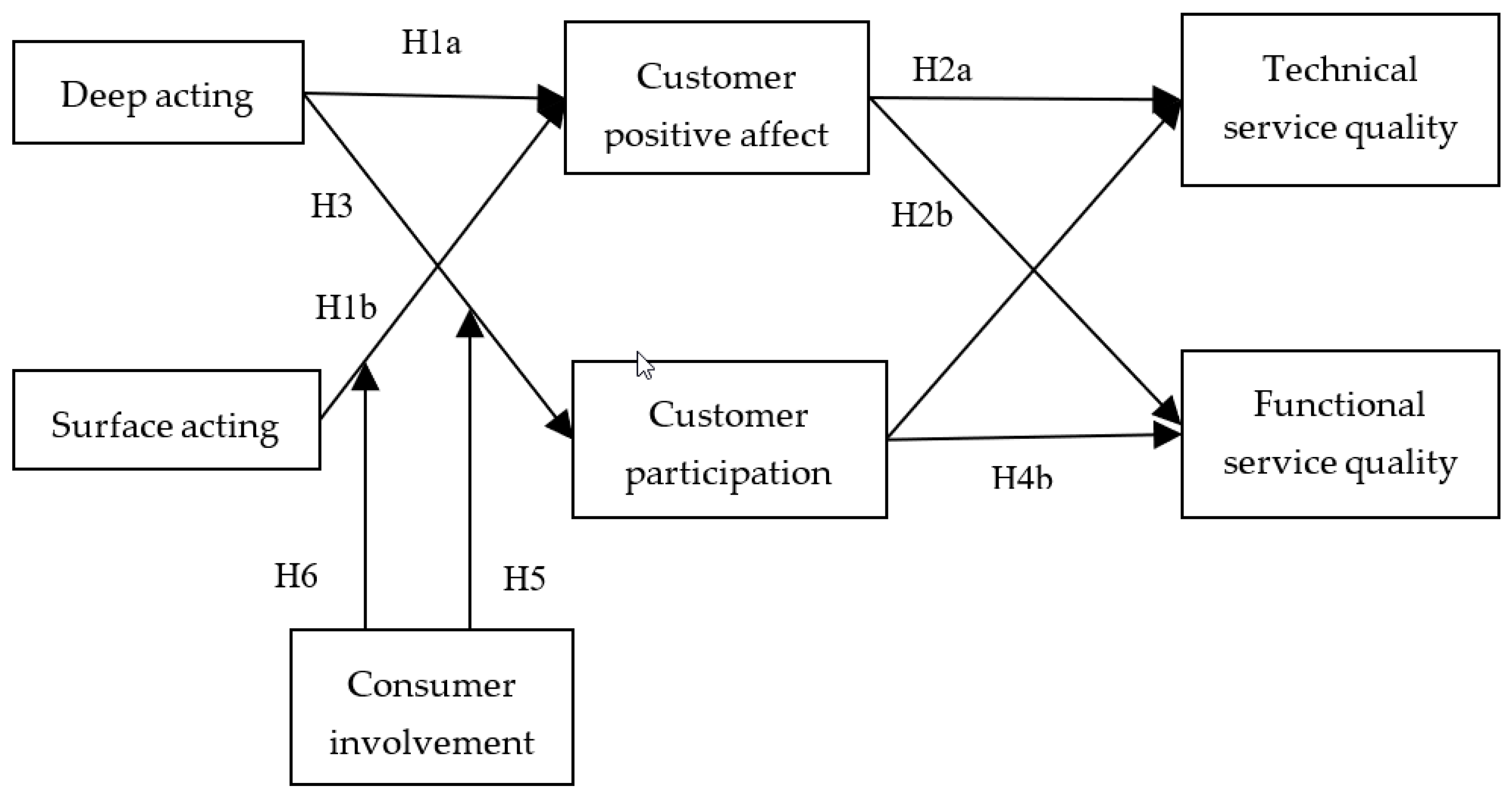

To address these research gaps, drawing on the EASI model, we propose a two-pathway mode: emotional contagion and emotional inferential processes, by which employees’ emotional labor can influence customer perceived service quality indirectly. Specifically, we operationalize the contagion and inferential processes by introducing customer positive affect and customer participation as mediators, respectively. Furthermore, we also propose customer involvement, which affects customer information seeking and information processing(Olk, Tscheulin et al. 2021), could serve as the boundary condition which could alter how different emotional labor strategies indirectly influence service quality via either emotional contagion or inferential process. We opening the “black box” that links employees’ emotional labor and service quality and identifying its boundary conditions to enrich the research on emotional labor. The findings may deepen managers’ understanding of emotional labor and afford effective managerial control instruments to guarantee high service quality.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Emotional Labor

Emotional labor refers to a series of behaviors performed by employees to comply organizations expectation by regulating their emotions during service encounters (Ashforth and Humphrey (1993)). Prior research has proposed two distinct strategies to regulate emotions: surface and deep acting(Grandey and Melloy 2017). Surface acting is defined that employees camouflage external emotional displays to conform with organizational display rules(Scott and Barnes 2011). Deep acting refers to an acting with more sincere. The employees who engage in deep acting try to adjust inner emotional experiences to be consistent with the mandated emotional display rules. Many previous studies emphasize the negative consequence of surface acting, such as low employee well-being (Yao and Gao 2021). In contrast, the outcomes of deep acting tend to be desirable. For example, is negatively and deep acting is positively associated with performance outcomes, especially customer satisfaction(Gabriel, Diefendorff et al. 2023, Groth and Esmaeilikia 2023).

2.2. Service Quality

As one of the most popular concepts in service marketing fields, perceived service quality refers to individual’s judgment about service production and delivery, and that is “formed by customers during the service experience.” (Pugh 2001, Dlačić, Arslanagić et al. 2014). Service quality includes two distinct dimensions (Ha and Jang 2010). Technical quality emphasizes the tangible aspect of the service, such as the accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of the service provided (Gallan, Jarvis et al. 2013). In contrast, functional quality focus on the process of how service is delivered. Such as customer’s experience of the interaction with service employees(De Keyser and Lariviere 2014). Both dimensions are crucial for delivering high-quality service (Gronroos 1993). Frontline employees, as representatives of service firms, are critical factor impacting service quality(Lin, Ling et al. 2021, Fan, Gao et al. 2022).

2.3. A Dual Pathway for Emotional Labor to Influence Perceived Service Quality

The emotions as social information model (EASI) states that emotions are important social information during interpersonal transactions, and observers interpret and infer others’ real motivation by using emotional cues and react to those cues (Van Kleef 2009). According to the EASI, observers have two paths to deal with others’ emotional information and allow their bodies to respond quickly(Deng, Walter et al. 2020). The emotional contagion pathway refers to a process by which individuals who automatically imitate and synchronize facial expressions, actions and vocalizations with others become emotionally convergent (Herrando, Jiménez-Martínez et al. 2022). By aligning their emotional expressions and physiological states with others, individuals begin to experience similar affective states, thereby fostering emotional alignment and shared feelings within social interactions. This pathway is a fundamental aspect of social bonding and empathy, enabling individuals to resonate emotionally with others in their environment. In contrast, the inferential pathway involves a cognitive process in which individuals use emotional information to deduce the underlying feelings, intentions, and motivations of those expressing emotions (Erle, Schmid et al. 2022). Unlike the automatic and unconscious nature of the emotional contagion pathway, the inferential pathway requires observers to engage in deliberate and effortful cognitive processing to interpret the true emotional states and motivations of others (Van Kleef 2009). In service interactions, we can infer customers, as observers of frontline employee’s displaying emotions, will take above two different paths to interpret employees’ real motivation and turn react to that emotional information.

2.3.1. The Emotional Contagion Pathway of Emotional Labor on Perceived Service Quality

According to the emotional contagion theory, individual’s emotional reactions can be evoked by others’ emotional displays (Hatfield, Bensman et al. 2014, Herrando and Constantinides 2021). During the contagion process, individual automatically mimics and unconsciously synchronizes other’s emotional states and behaviors, consequently, generating physiological feedback and translating into corresponding feelings(Norscia, Zanoli et al. 2020, Kong 2022). There are two distinct contagion process: primitive contagion and deliberate contagion. Primitive contagion occurs when people unconsciously and automatically synchronize with the emotions of others without devoting much cognitive effort to judging their authenticity (Hatfield, Cacioppo et al. 1992). Even though frontline employees are displaying fake positive emotions (surface acting), customers are still affected and experience similar positive emotions through primitive contagion. Therefore, frontline employees’ surface acting is expected to exert positive influence on customer positive affect.

In contrast, deliberate contagion refers to the intentional process of transferring emotions from one person (or group) to another through verbal, nonverbal, or behavioral cues. In service interactions, frontline employees perform deep acting through deliberately regulating their inner feelings and expressing positive emotions to create excellent service experience for customers. Hence, frontline employees’ deep acting is expected to foster customer positive affect. Actually, prior researchers have identified that positive emotions displayed by employees predict customer positive affect (Pugh 2001). Therefore, we can infer that no matter whether frontline employees display genuine (deep acting) or fake positive emotions (surface acting) during service encounters, they could induce positive customer affect through the emotional contagion pathway.

A critical element which customers evaluate service quality is employee-customer interaction. Especially in high contact service industries, customer’s positive affect, as the core of customer experience, plays vital role of determining customer’s service evaluation (Zeithaml, Berry et al. 1988). Research on affect infusion considers that individuals’ global judgments are influenced by their affective states (Forgas 1995). Positive affect may prevent customers from critical thinking and improve their positive evaluation, such as high service quality.(Barger and Grandey 2006, Rocklage and Fazio 2020).

2.3.2. The Emotional Inferential Pathway of Emotional Labor on Perceived Service Quality

According to EASI, the observer who takes the emotional inferential pathway will infer others’ real motivation by their emotions(Van Kleef 2014). During this process, the observer devotes greater cognitive efforts, which influences the observer’s behavioral reactions(Bruder, Lechner et al. 2021, Erle, Schmid et al. 2022). Customers were evoked positive emotions and behavioral reactions in service context only when customers perceived employee positive emotional displays as authentic (deep acting)(Gong, Park et al. 2020). On the contrary, if customers consider employees’ emotions as faked (surface acting), they will question employees’ real motivation, which will undermine their trust(Liu, Wang et al. 2019). Therefore, only employees’ deep acting affects customers’ behavior reactions through the emotional inferential pathway.

Customer participation refers to the degree that customers afford resource inputs in producing and delivering services(Morgan, Obal et al. 2018). When customers engage in the service production and delivery, customers should invest extra time, energy, and personal effort(Li and Hsu 2017). Thus, customer participation is an individual’s elaborate processing which occurs only during the inferential pathway. We propose, in service interaction, frontline employees’ deep acting can initiate customer participation, primarily through the emotional inferential pathway rather than the contagion pathway.

Given the inseparability of service(Moeller 2010), service quality is determined by both employees and customers(Rather and Camilleri 2019). Through customer participation, service firms can obtain customer preference information and design offerings that meet unique and changing needs. Furthermore, participation helps customers get a better understanding of the service process and enriches their knowledge and information about service which can avoid irrational expectations of service(Barari, Ross et al. 2021). According to Gallan, Jarvis et al. (2013), customized services, personal knowledge given by customer participation imply high level of technical service quality. Except improving technical service quality, Customer participation also fosters functional service quality. By providing opportunities for customers to directly interfere with the service production(Kumar and Pansari 2016), customer participation makes customers’ service experience more enjoyable through increasing their sense of control over the service process (Auh, Menguc et al. 2019). Furthermore, customer participation facilitates communication and provides opportunities to strengthen customer-employee bonds(Delpechitre, Beeler-Connelly et al. 2018). Therefore, customer participation fosters the employee-customer interaction and enhances functional service quality.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Customer Involvement

Customer involvement is defined as the extent of perceived association of something to the customer based on intrinsic demands, values, and interests(Cui and Wu 2016). Previous research has identified customer involvement as a critical motivational variable that can influence customers’ purchase decisions, information seeking, and way of information processing(Cheung, Xiao et al. 2012, Li, Li et al. 2019). According to information-processing theory(Hann, Hui et al. 2007), customers with high involvement have higher cognitive needs, which drive them to process external information more carefully and to form their judgments. Hence, we conclude that highly involvement customers are more motivated to spend cognitive efforts in inferring employee’s emotions, namely the emotional inferential pathway.

H5: The positive influence of deep acting on customer participation is stronger(weaker) when customer involvement is high (low).

H6: The positive influence of surface acting on customer positive affect is weaker (stronger) when customer involvement is high (low).

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

Considering the facilitation of investigating emotional labor, we select retail banking service which is characterized by intense employee-customer interaction. The dyadic data was collected on-site from frontline employee and their customers in ten retail banks located in northwestern China. When the interaction is over, both employees and customers were invited to participate the survey. Employees were requested to report the extent of emotional labor to which he/she just performed during the interaction. In contact, customers were requested to report their level of positive affect, participation, involvement, and perceived service quality. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, and 371 of these were eventually collected. After removing 17 incomplete responses, 354 were usable, for a response rate of 78.7%.

3.2. Measures

All core constructs were measured by five-point Likert scales ranging 1 (extremely disagree) to 7 (extremely agree). Specifically, frontline employees reported their deep and surface acting using two 3-item scales developed by Brotheridge and Lee (2003). Customer participation was reported by customers using a scale with five items developed by Chan, Yim et al. (2010). Customer reported their positive affect using 6-item scale from Pugh (2001), originally developed by Brief, Burke et al. (1988). With respect to service quality, we adopt two 3-item scales from Gallan, Jarvis et al. (2013) to capture the two key dimensions: functional and technical quality, respectively. Customer involvement was measured using 4 items by Cheung and To (2011). Control variables included gender, age, income, and education.

3.3. Validity and Reliability

Before testing the hypotheses, the validity and reliability of all variables were examined. For validity, we performed Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) by restricting every item only loaded on its specified factor. The results (Chi-Square= 868.82 df=303; RMSEA= 0.073; NFI =0.93; NNFI=0.95; CFI =0.95; GFI= 0.85) of the measurement model with 7 factors indicate that the model fits the data well. The minimum factor loading of items is 0.67 (

Table 1) which exceeds the threshold value 0.6. Therefore, the of convergent validity of all variables is acceptable. To examine the discriminant validity of all variables, we first calculated the average variances extracted (AVE) of all variables and then compared square roots of AVE with all corresponding correlations. As shown in

Table 2, all variables’ square roots of AVE are greater than any corresponding correlations, indicating acceptable discriminant validity. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (ranging from 0.817 to 0.918) of all constructs were above the cut-off value 0.70 (see

Table 1), indicating acceptable reliability.

4. Results

4.1. Test of the Mediating Effects

To examine mediation effects of customer participation and customer positive affect on the link of emotional labor to technical service quality, we ran several regression models by following Baron and Kenny (1986) process. First, we tested the effects of emotional labor on technical service quality (TSQ). The results of M-1 in

Table 3 indicated that deep acting exerted positive and significant (β = 0.419, p < 0.01) influences on technical service quality. However, surface acting had a negative influence (β = -0.122, p < 0.1) on technical service quality. Second, we regressed two mediators (customer participation and customer positive affect) on emotional labor, respectively. The results of M-2 provided support for H3 as the effect of deep acting on customer participation is significant and positive (β = 0.307, p < 0.01). That means frontline employees’ deep acting could effectively encourage customer to participate. The results of M-3 showed that both deep acting (β = 0.405, p < 0.01) and surface acting (β = 0.162, p < 0.01) had positive influence on customer positive affect, supporting H1a and H1b. Third, we regressed technical service quality (TSQ) on independent variables and mediators simultaneously. The results of M-4 showed that: under the control of mediators, (a)the positive link of deep acting to technical service quality was no longer significant; (b) the link of surface acting to technical service quality remained significant and negative (β = -0.215, p < 0.01) and (c) both customer participation (β = 0.530, p < 0.01) and customer positive affect (β = 0.389, p < 0.01) had positive effects on technical service quality, supporting H2a and H4a. That means the influence of deep acting on technical service quality was fully mediated by both customer participation and customer positive affect. While the influence of surface acting on technical service quality was partially mediated only by customer positive affect. It was worth noting that surface acting shown negative direct influence and positive indirect influence through customer positive affect simultaneously.

To test mediation effects of customer participation and customer positive affect on the link of emotional labor to functional service quality, we first regressed the functional service quality on emotional labor. The coefficients of M-5 in

Table 3 indicated that both deep acting (β = 0.382, p<0.01) and surface acting (β = 0.140, p<0.01) had positive influence on functional service quality. In M-6, after entering the mediators, the regression coefficient of deep acting remained positive and significant (β = 0.211, p<0.01), while the regression coefficient of surface acting became nonsignificant. In addition, both customer participation (β = 0.197, P <0.01) and customer positive affect (β = 0.275, P <0.01) had significant and positive influence on functional service quality, supporting H2b and H4b. These findings indicated that the influence of deep acting on functional service quality was partially mediated by both customer participation and customer positive affect. While the influence of surface acting on functional service quality was partially mediated only by customer positive affect.

Table 3.

Mediating effects test.

Table 3.

Mediating effects test.

| Independent variables |

M-1 |

M-2 |

M-3 |

M-4 |

M-5 |

M-6 |

| TSQ |

CP |

CPA |

TSQ |

FSQ |

FSQ |

| Control variables |

Gender |

0.031 |

0.081 |

0.007 |

-0.014 |

-0.053 |

-0.071 |

| Age |

-0.116 |

0.136* |

-0.175** |

-0.120 |

-0.034 |

-0.013 |

| Revenue |

0.102 |

0.133* |

-0.057 |

0.054 |

0.016 |

0.005 |

| Education |

0.000 |

-0.142* |

-0.003 |

0.076 |

0.044 |

0.073 |

| DA |

0.419*** |

0.307*** |

0.405*** |

0.099 |

0.382*** |

0.211*** |

| SA |

-0.122* |

0.058 |

0.162*** |

-0.215*** |

0.140** |

0.084 |

| CP |

-- |

-- |

-- |

0.530*** |

-- |

0.197*** |

| CPA |

-- |

-- |

-- |

0.389*** |

-- |

0.275*** |

| R2

|

0.139*** |

0.177*** |

|

0.352*** |

0.198*** |

0.268*** |

4.2. Test of the Moderating Effects

We tested the moderating effect of customer involvement by conducting hierarchical regressions. We initially examine the main effects of emotional labor on customer participation. The regression coefficients of M-7 (

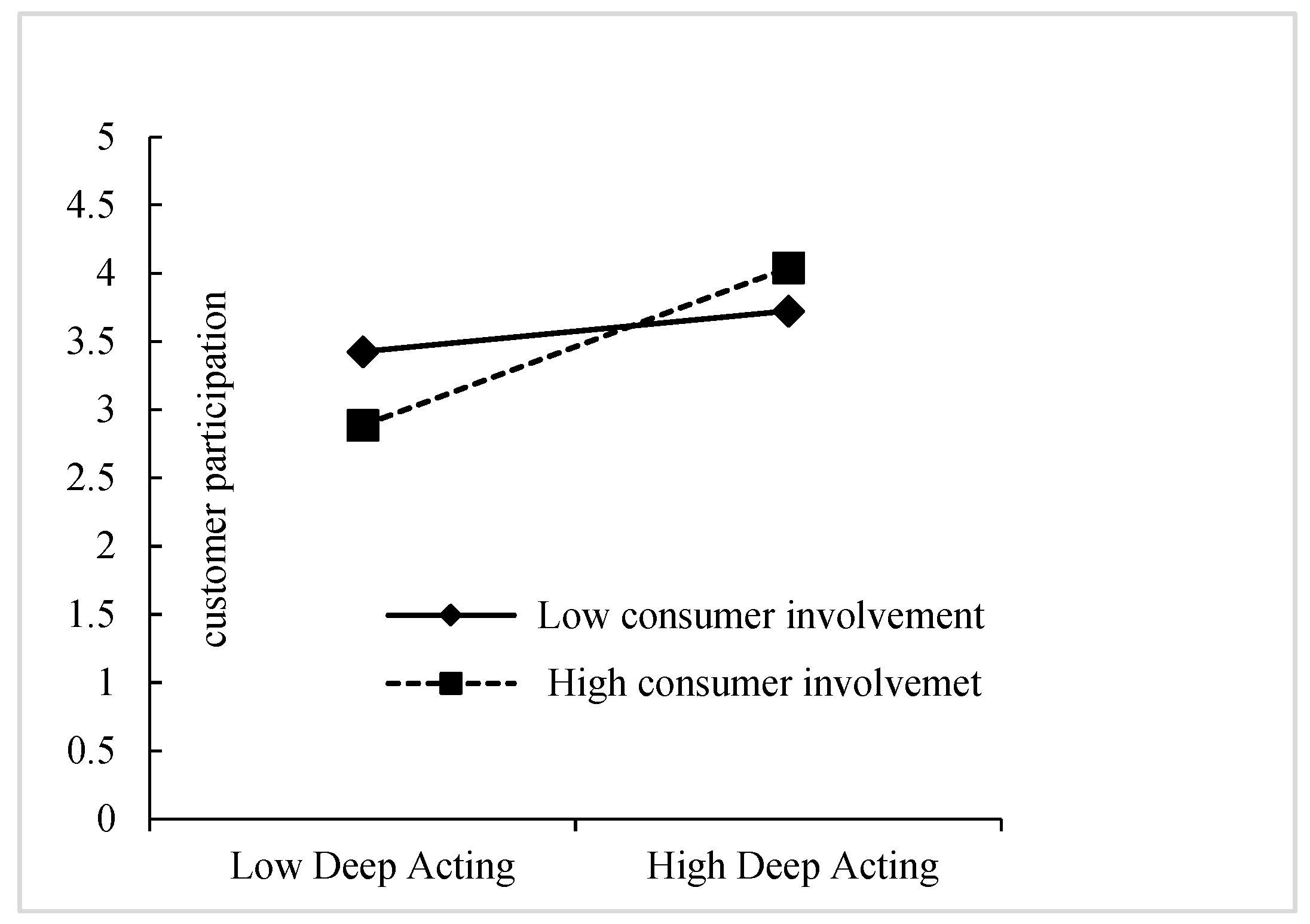

Table 4) indicated that deep acting had positive influence on customer participation (β = 0.418, p<0.01), while neither surface acting nor customer involvement were significantly associated with customer participation. Then, the interaction item (DA*CI) was entered in the regression model(M-8). The interaction of deep acting with customer involvement (DA*CI) was positive and significant (β = 0.214, p<0.01). Also, the R2 changed from 0.18 to 0.21, which was significant (ΔR2=0.030, P<0.01). Hence, H5 was supported.

We visualized the moderating effect by plotting the simple slopes of deep acting -customer participation relationship at high and low levels of customer involvement. As shown in

Figure 2, among customers reporting high levels of involvement, employee’s high deep acting fostered higher participation than those low in involvement.

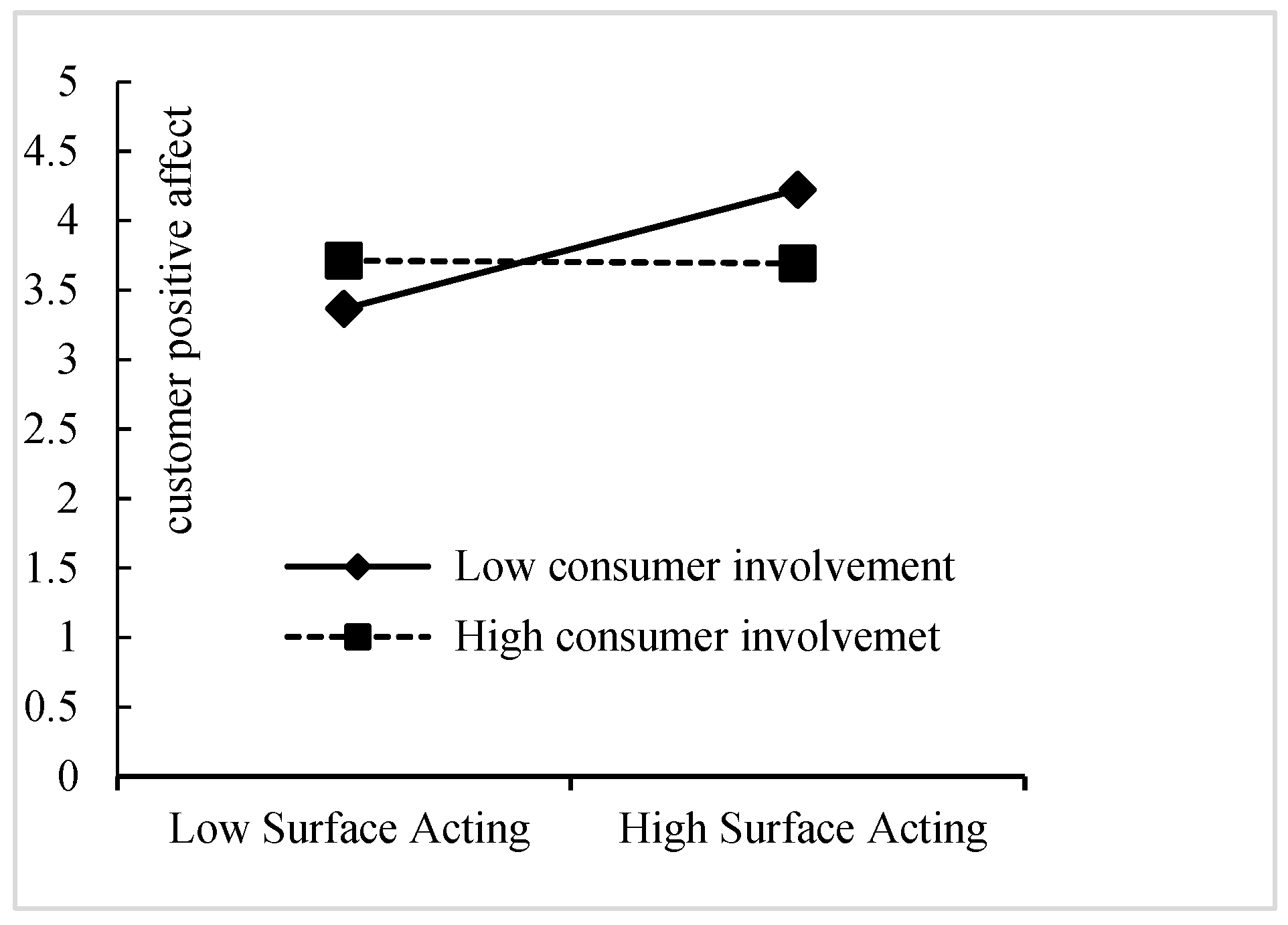

For the moderating effect of customer involvement on the relationship between surface acting and customer positive affect, the coefficients of M-9 shown that both deep acting (β = 0.569, p <0.01) and surface acting (β = 0.210, p <0.01) had positive influence on customer positive affect. However, while there was no significant relationship between customer involvement and customer positive affect. When the interaction item (SA*CI) was introduced (M-10), the regression coefficient of the interaction item was negative and significant (β = -0.219, p<0.01). The R2 changes were also significant (ΔR2 = 0.033, P <0.01). Thus, H6 was supported.

We plotted the simple slopes of surface acting on customer positive affect at high and low levels of customer involvement. As shown in

Figure 3, among customers reporting low levels of involvement, employee’s high surface acting fostered higher positive affect than those high in involvement.

5. Discussion

Drawing upon EASI, we propose that emotional labor influences service quality through customer participation and customer positive affect. Also, we consider the boundary condition of this mechanism by examining the moderating effects of customer involvement. Our findings showed that service quality was influenced by deep acting through both the emotional contagion pathway and the inferential pathway. Specifically, customer positive affect and customer participation fully mediated the effects of deep acting on technical service quality. However, customer positive affect and customer participation partially mediated the influence of deep acting on functional service quality, meanwhile deep acting influenced functional service quality directly and positively.

Furthermore, surface acting influenced service quality only through the emotional contagion pathway. Specifically, surface acting was related to technical service quality partially mediated by customer positive affect, while the effect on functional service quality was fully mediated by customer positive affect. A side note of interest is that surface acting influences technical service quality through the negative direct effect and positive mediating effect simultaneously.

Finally, customer involvement moderated the relationship between emotional labor on service quality. For highly involved customers, frontline employees’ deep acting had a stronger influence on customer participation than it did for less involved customers. However, for customers with low involvement, frontline employees’ surface acting had a stronger positive influence on customer positive affect than for customers with high involvement.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Although both theory and practice acknowledge that frontline employees displaying positive emotions in service encounters could bring better service experiences and higher service evaluations (Rocklage and Fazio 2020, Zhan, Luo et al. 2021), little is known about the mechanism through which employees’ emotional labor links to service quality (Lechner and Mathmann 2021). To address this gap, drawing on EASI model, we proposed that emotional contagion pathway (customer positive affect) and the inferential pathway (customer participation) serve as parallel mediators of the link from employee emotional labor to perceived service quality. Thus, the present research revealed the process of how frontline employees’ distinct emotion regulation strategies influence customer’s perceived service quality. The findings could answer previous studies’ call for exploring the psychological mechanism through which customer could internalize and interpret frontline employees’ difference emotional labor strategies and in turn drive their perceived service quality (Subramony, Groth et al. 2021).

Second, the findings of this study contribute to the emotional labor theory by confirming that distinct emotional labor strategies influence customer’s service evaluation through different mechanisms. Although Gong, Park & Hyun (2020) persisted that customer’s perception of frontline employee’s emotional labor would affect customer loyalty through affective reactions and cognitive appraisals(Gong, Park et al. 2020), little attention has been paid to different mechanisms by deep and surface acting exert influence on service evaluation. According to our findings, deep acting could trigger customers emotional contagion and inferential process simultaneously, while surface acting could only activate emotional contagion process. Therefore, this study supply evidence to extend current understandings of how customers utilize their perceptions of frontline employees’ emotion expression to evaluate the service.

Finally, this study contributes to the literature on EASI by exploring the boundary condition of this model applied in the context of service interaction by examining the moderating effect of customer involvement. By doing so, these findings could respond to Kleef and Côté’s call for extend EASI to different organizational settings(Kleef and Côté 2022). In service interactions, customers with different involvement rely on different strategies to process frontline employees’ emotions. For customers with high involvement, inferential process was more likely to be utilized to interpret frontline employees’ emotion. In contrast, low involved customers prone to take contagion process to use frontline employees’ emotions. These findings provide evidence of the boundary conditions of EASI.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The findings of this study shed light on how service firms could improve service quality. First, Managers should realize the vital role of frontline employee’s emotional labor in shaping customer’s perception of service quality. They could adopt techniques such as cognitive reassessment and attention deployment to help employees regulate internal emotional states more effectively, and guide frontline employees to adopt deep acting rather than surface acting during service encounters(Kang and Jang 2022). Second, frontline employees should be aware of the level of customer involvement. For customers with high level involvement, employees should attach importance to deep acting to show real positive emotions(Kim and Park 2023). For low-involvement customers, it makes little difference whether positive emotions shown by employees are real or not. At this point, employees can focus more on other aspects of the service interaction, such as service productivity(Bellet, De Neve et al. 2024) and accuracy(Soemah 2023).

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, the data this study was collected in banking industry, which might limit the generalizability of these findings. Future studies should collect data from multi service industries to examine the generalizability of these findings. Second, according to the EASI model, individuals taking which way to process others’ emotions depends on their competence to process emotional information. It is therefore necessary to consider new moderators of this mediation. Emotional intelligence (EI), which refers to the ability to recognize, understand, manage, and influence emotions—both in yourself and others (Prentice, Dominique Lopes et al. 2020), should be considered as new moderator in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.; methodology, P.C.; software, X.Z.; validation, X.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, P.C.; resources, P.C.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C. and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, P.C. and X.Z.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, X.Z.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 23BJY065.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans (Article 32, Chapter 3) issued jointly by the Chinese Health Commission, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Bureau of Traditional Chinese Medicine (see

https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658; accessed on 25 June 2025). We certify that this study was performed following the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and later amendments.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrzejewski, S. A. and E. C. Mooney (2016). "Service with a smile: Does the type of smile matter?" Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 29: 135-141.

- Ashforth, B. E. and R. H. Humphrey (1993). "Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity." Academy of Management Review 18(1): 88-115.

- Auh, S., B. Menguc, C. S. Katsikeas and Y. S. Jung (2019). "When does customer participation matter? An empirical investigation of the role of customer empowerment in the customer participation–performance link." Journal of marketing research 56(6): 1012-1033. [CrossRef]

- Barari, M., M. Ross, S. Thaichon and J. Surachartkumtonkun (2021). "A meta-analysis of customer engagement behaviour." International Journal of Consumer Studies 45(4): 457-477.

- Barger, P. B. and A. A. Grandey (2006). "Service with a smile and encounter satisfaction: Emotional contagion and appraisal mechanisms." Academy of Management journal 49(6): 1229-1238. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M. and D. A. Kenny (1986). "The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations." Journal of personality and social psychology 51(6): 1173.

- Bellet, C. S., J.-E. De Neve and G. Ward (2024). "Does employee happiness have an impact on productivity?" Management science 70(3): 1656-1679.

- Brief, A. P., M. J. Burke, J. M. George, B. S. Robinson and J. Webster (1988). "Should negative affectivity remain an unmeasured variable in the study of job stress?" Journal of Applied Psychology 73(2): 193.

- Brotheridge, C. M. and R. T. Lee (2003). "Development and validation of the Emotional Labour Scale." Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 76(3): 365-379.

- Bruder, M., A. T. Lechner and M. Paul (2021). "Toward holistic frontline employee management: An investigation of the interplay of positive emotion displays and dress color." Psychology & Marketing 38(11): 2089-2101. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. W., C. K. Yim and S. S. K. Lam (2010). "Is Customer Participation in Value Creation a Double-Edged Sword? Evidence from Professional Financial Services Across Cultures." Journal of Marketing 74(3): 48-64.

- Cheung, C. M., B. Xiao and I. L. Liu (2012). The impact of observational learning and electronic word of mouth on consumer purchase decisions: The moderating role of consumer expertise and consumer involvement. 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE.

- Cheung, M. F. Y. and W. To (2011). "Customer involvement and perceptions: The moderating role of customer co-production." Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 18(4): 271-277.

- Cui, A. S. and F. Wu (2016). "Utilizing customer knowledge in innovation: antecedents and impact of customer involvement on new product performance." Journal of the academy of marketing science 44: 516-538. [CrossRef]

- De Keyser, A. and B. Lariviere (2014). "How technical and functional service quality drive consumer happiness: moderating influences of channel usage." Journal of Service Management 25(1): 30-48.

- Delpechitre, D., L. L. Beeler-Connelly and N. N. Chaker (2018). "Customer value co-creation behavior: A dyadic exploration of the influence of salesperson emotional intelligence on customer participation and citizenship behavior." Journal of Business Research 92: 9-24. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H., F. Walter and Y. Guan (2020). "Supervisor-directed emotional labor as upward influence: An emotions-as-social-information perspective." Journal of Organizational Behavior 41(4): 384-402.

- Deng, H., F. Walter, C. K. Lam and H. H. Zhao (2017). "Spillover effects of emotional labor in customer service encounters toward coworker harming: A resource depletion perspective." Personnel Psychology 70(2): 469-502. [CrossRef]

- Dlačić, J., M. Arslanagić, S. Kadić-Maglajlić, S. Marković and S. Raspor (2014). "Exploring perceived service quality, perceived value, and repurchase intention in higher education using structural equation modelling." Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 25(1-2): 141-157. [CrossRef]

- Erle, T. M., K. Schmid, S. H. Goslar and J. D. Martin (2022). "Emojis as social information in digital communication." Emotion 22(7): 1529. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H., W. Gao and B. Han (2022). "How does (im) balanced acceptance of robots between customers and frontline employees affect hotels’ service quality?" Computers in Human Behavior 133: 107287.

- Forgas, J. P. (1995). "Mood and judgment: the affect infusion model (AIM)." Psychological Bulletin 117(1): 39-66.

- Gabriel, A. S., J. M. Diefendorff and A. A. Grandey (2023). "The acceleration of emotional labor research: Navigating the past and steering toward the future." Personnel Psychology 76(2): 511-545. [CrossRef]

- Gallan, A., C. Jarvis, S. Brown and M. Bitner (2013). "Customer positivity and participation in services: an empirical test in a health care context." Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41(3): 338-356. [CrossRef]

- Gong, T., J. Park and H. Hyun (2020). "Customer response toward employees’ emotional labor in service industry settings." Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 52: 101899. [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A. and R. C. Melloy (2017). "The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised." Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22(3): 407-422. [CrossRef]

- Gronroos, C. (1993). "A service quality model and its marketing implications." European Journal of Marketing 18(4): 36-44. [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. and M. Esmaeilikia (2023). "The impact of emotional labor strategy order effects on customer satisfaction within service episodes." European Journal of Marketing 57(12): 3041-3071. [CrossRef]

- Ha, J. and S. S. Jang (2010). "Effects of service quality and food quality: The moderating role of atmospherics in an ethnic restaurant segment." International journal of hospitality management 29(3): 520-529. [CrossRef]

- Hann, I.-H., K.-L. Hui, S.-Y. T. Lee and I. P. Png (2007). "Overcoming online information privacy concerns: An information-processing theory approach." Journal of management information systems 24(2): 13-42. [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E., L. Bensman, P. D. Thornton and R. L. Rapson (2014). "New perspectives on emotional contagion: A review of classic and recent research on facial mimicry and contagion." Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E., J. T. Cacioppo and R. L. Rapson (1992). "Primitive emotional contagion." Emotion & Social Behavior. 14.(2): 151-177.

- Herrando, C. and E. Constantinides (2021). "Emotional contagion: A brief overview and future directions." Frontiers in psychology 12: 712606. [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C., J. Jiménez-Martínez, M. J. Martín-De Hoyos and E. Constantinides (2022). "Emotional contagion triggered by online consumer reviews: Evidence from a neuroscience study." Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 67: 102973. [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart:Commercialization of Human Feeling. Los Angeles, University of California Press.

- Kang, J. and J. Jang (2022). "Frontline employees’ emotional labor toward their co-workers: The mediating role of team member exchange." International Journal of Hospitality Management 102: 103130. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S. and H. J. Park (2023). "How Service Employees’ Mindfulness Links to Task Performance through Psychological Resilience, Deep Acting, and Customer-Oriented Behavior." Behavioral Sciences 13(8): 657.

- Kleef, v. and Côté (2022). "The Social Effects of Emotions." Annual Review of Psychology 73(Volume 73, 2022): 629-658.

- Kong, Y. (2022). "Are emotions contagious? A conceptual review of studies in language education." Frontiers in psychology 13: 1048105. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. and A. Pansari (2016). "Competitive advantage through engagement." Journal of marketing research 53(4): 497-514.

- Lechner, A. T. and F. Mathmann (2021). "Bringing service interactions into focus: Prevention-versus promotion-focused customers’ sensitivity to employee display authenticity." Journal of Service Research 24(2): 284-300. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J. (2018). "Emotional labor and organizational commitment among South Korean public service employees." Social behavior and personality 46(7): 1191-1200. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. and C. Hsu (2017). "Customer participation in services and its effect on employee innovative behavior." Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 26(2): 164-185. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., G. Li, T. Feng and J. Xu (2019). "Customer involvement and NPD cost performance: the moderating role of product innovation novelty." Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 34(4): 711-722. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M., Q. Ling, Y. Liu and R. Hu (2021). "The effects of service climate and internal service quality on frontline hotel employees’ service-oriented behaviors." International Journal of Hospitality Management 97: 102995. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Z. Song, X. Li and Z. Liao (2017). "Why and When Leaders’ Affective States Influence Employee Upward Voice." Academy of Management Journal 60(1): 238-263. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Y., J. Wang and C. Zhao (2019). "An examination of the congruence and incongruence between employee actual and customer perceived emotional labor." Psychology & Marketing 36(9): 863-874. [CrossRef]

- Madera, J. M., D. C. Taylor and N. A. Barber (2020). "Customer service evaluations of employees with disabilities: The roles of perceived competence and service failure." Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 61(1): 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S. (2010). "Characteristics of services–a new approach uncovers their value." Journal of services Marketing 24(5): 359-368. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T., M. Obal and S. Anokhin (2018). "Customer participation and new product performance: Towards the understanding of the mechanisms and key contingencies." Research Policy 47(2): 498-510. [CrossRef]

- Norscia, I., A. Zanoli, M. Gamba and E. Palagi (2020). "Auditory contagious yawning is highest between friends and family members: Support to the emotional bias hypothesis." Frontiers in Psychology 11: 503511. [CrossRef]

- Olk, S., D. K. Tscheulin and J. Lindenmeier (2021). "Does it pay off to smile even it is not authentic? Customers’ involvement and the effectiveness of authentic emotional displays." Marketing Letters 32(2): 247-260. [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C., S. Dominique Lopes and X. Wang (2020). "Emotional intelligence or artificial intelligence– an employee perspective." Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 29(4): 377-403. [CrossRef]

- Pugh, S. D. (2001). "SERVICE WITH A SMILE: EMOTIONAL CONTAGION IN THE SERVICE ENCOUNTER." Academy of Management Journal 44(5): 1018-1027.

- Rather, R. A. and M. A. Camilleri (2019). "The effects of service quality and consumer-brand value congruity on hospitality brand loyalty." Anatolia 30(4): 547-559. [CrossRef]

- Rocklage, M. D. and R. H. Fazio (2020). "The enhancing versus backfiring effects of positive emotion in consumer reviews." Journal of Marketing Research 57(2): 332-352. [CrossRef]

- Scott, B. A. and C. M. Barnes (2011). "A Multilevel Field Investigation of Emotional Labor, Affect, Work Withdrawal, and Gender." Academy of Management Journal 54(1): 116-136.

- Shin, I. and W. M. Hur (2020). "How are service employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility related to their performance? Prosocial motivation and emotional labor as underlying mechanisms." Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27(6): 2867-2878. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y., W.-M. Hur and H. Hwang (2022). "Impacts of customer incivility and abusive supervision on employee performance: a comparative study of the pre-and post-COVID-19 periods." Service Business 16(2): 309-330. [CrossRef]

- Soemah, E. N. (2023). "Accuracy of Triage in Service in The Emergency Department (Literature Review)." Journal of Scientific Research, Education, and Technology (JSRET) 2(2): 782-786. [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M., M. Groth, X. J. Hu and Y. Wu (2021). "Four Decades of Frontline Service Employee Research: An Integrative Bibliometric Review." Journal of Service Research 24(2): 230-248. [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G. A. (2009). "How Emotions Regulate Social Life: The Emotions as Social Information (EASI) Model." Current Directions in Psychological Science 18(3): 184-188.

- Van Kleef, G. A. (2014). "Understanding the positive and negative effects of emotional expressions in organizations: EASI does it." Human Relations 67(9): 1145-1164.

- Van Kleef, G. A. and S. Côté (2022). "The social effects of emotions." Annual review of psychology 73: 629-658.

- Wang, C.-J. (2019). "Managing emotional labor for service quality: A cross-level analysis among hotel employees." International Journal of Hospitality Management: 102396. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., S. N. Singh, Y. J. Li, S. Mishra, M. Ambrose and M. Biernat (2017). "Effects of Employees’ Positive Affective Displays on Customer Loyalty Intentions: An Emotions-As-Social-Information Perspective." Academy of Management Journal 60(1): 109-129. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L. and J. Gao (2021). "Examining Emotional Labor in COVID-19 through the Lens of Self-Efficacy." Sustainability 13(24): 13674. [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A., L. L. Berry and A. Parasuraman (1988). "Communication and control processes in the delivery of service quality." Journal of Marketing 52(2): 35-48.

- Zhan, X., W. Luo, H. Ding, Y. Zhu and Y. Guo (2021). "Are employees’ emotional labor strategies triggering or reducing customer incivility: a sociometer theory perspective." Journal of Service Theory and Practice 31(3): 296-317. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).