1. Introduction

From a classical business standpoint, the primary objective of firms is profit generation, with financial goals narrowly focused on profit maximization. However, contemporary business paradigms increasingly emphasize a triadic purpose: generating profit, creating societal value, and ensuring sustainability through long-term continuity. Among these aims, sustainability has emerged as the foundational goal, requiring firms to integrate environmental and social considerations into their strategic decision-making. This integrated approach enables organizations to strike a meaningful balance between economic performance and societal welfare, an equilibrium that cannot be attained through profit maximization alone. Accordingly, the financial objective must evolve toward value maximization, which entails optimizing the present value of anticipated future earnings while accounting for stakeholder interests. True value maximization necessitates reconciling the needs of diverse societal segments. Without safeguarding consumer rights, ensuring fair labor practices, promoting inclusive employment, protecting ecological systems, and funding social services (e.g., elderly care centers, women’s shelters, empowering women, child support programs, social entrepreneurship and innovation programs, rehabilitation services for disabled individuals, and post-disaster psychosocial support centers), sustainable value creation remains elusive. In this context, CSR has gained prominence as a strategic construct, attracting growing scholarly and managerial attention due to its pivotal role in advancing organizational sustainability [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

CSR has emerged as a strategically relevant concept across a broad spectrum of industries, with implications that vary significantly depending on sectoral characteristics and stakeholder configurations. CSR has become particularly salient in the banking sector, where institutions allocate substantial resources to socially responsible initiatives and actively engage in sustainability-driven practices. Given the sector’s systemic influence and stakeholder complexity, CSR has increasingly attracted academic scrutiny. In today’s volatile financial landscape, bank managers face multifaceted challenges that render profit-centric models insufficient. Consequently, CSR has evolved into a critical research domain within banking, offering insights into how ethical and socially responsive strategies can enhance institutional resilience and stakeholder emotions [

14,

15,

16].

Su et al. [

17] examined the relationships among CSR, corporate reputation, and customers’ positive and negative emotions, while Castro-Gonzalez and Vilela [

18] explored the links between CSR, corporate reputation, and customer admiration. Although neither study tested the mediation effects, their findings offer conceptual inspiration for the construction of mediation models involving these variables. A comprehensive literature review also identified studies investigating the relationships between CSR and customer emotions (e.g., [

15,

17,

19,

20,

21]), CSR and financial performance (e.g., [

16,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]), and corporate reputation and customer emotions (e.g., [

17,

28,

29,

30]). These studies collectively provided the conceptual foundation for the mediation model proposed in this research. Unlike previous studies [

17,

18], this research presents CSR through the society dimension, which encompasses all organizational stakeholders [

31], and focuses on the financial performance dimension of corporate reputation [

32]. Furthermore, while Castro-Gonzalez and Vilela [

18] focused on admiration, this study adopts a positive–negative emotion classification [

33], consistent with the work of Su et al. [

17]. The primary objective of this study is to examine whether the perceived financial performance mediates the relationships between customers’ perceptions of their bank’s CSR activities and the positive and negative emotions they associate with the bank. According to the literature, strengthened perceptions of CSR [

15] and corporate reputation/financial performance [

17] contribute positively to organizations. Customers’ positive emotions [

33] enhance organizational outcomes, while negative emotions [

33] undermine organizational success. Accordingly, the central research question is presented: Can strengthened CSR perceptions, by improving evaluations of a bank’s financial performance, enhance customers’ positive emotions and reduce their negative emotions in ways that benefit the institution?

This study is theoretically grounded in Social Exchange Theory [

34], Social Identity Theory [

35], and Stakeholder Theory [

36]. Social Exchange Theory is built upon the Norm of Reciprocity [

37], emphasizing that interactions between parties shape their emotions, attitudes, and behaviors toward one another [

34]. Social Identity Theory suggests that individuals define themselves through group or organizational affiliation, and this identification is particularly influenced by the organization’s socially responsible actions [

35]. Stakeholder Theory asserts that all stakeholder interests must be considered in organizational decision-making to ensure sustainability [

36]. Within the scope of these theoretical frameworks, CSR practices serve as the conceptual starting point of the research model, given their potential to influence customers’ positive and negative emotional responses toward their bank. Specifically, when customers perceive that their bank fulfills its responsibilities toward society, it is expected that their positive emotional responses will intensify, while their negative emotional responses will diminish. This emotional shift is likewise anticipated to be reinforced by customers’ enhanced evaluations of the bank’s performance regarding financial criteria such as profitability and continuity.

The subsequent sections of this article systematically develop the conceptual and empirical basis of the study.

Section 2 presents a literature review structured under thematic subheadings, beginning with an overview of sustainability and sustainable banking and encompassing both theoretical insights and empirical findings related to CSR, customer emotions, financial performance, and the interrelationships among these constructs. Drawing on these foundations,

Section 3 introduces the research model and formulates the hypothesis.

Section 4 presents the research method.

Section 5 reports the research findings.

Section 6 highlights the study’s originality, aligns its findings with prior empirical evidence, offers a functional interpretation of the results, outlines theoretical and practical implications, addresses limitations and future research directions.

Section 7 summarizes the study’s contributions and closes with final remarks.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability and Sustainable Banking

Recent scholarship positions sustainability as a multidimensional paradigm that permeates corporate strategy, linking environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic resilience in an integrated framework. Studies highlight its role in enhancing stakeholder trust, fostering innovation, and securing long-term competitive advantage, particularly when aligned with global policy frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement Empirical evidence suggests that firms embedding sustainability into governance structures and operational processes tend to outperform peers in both reputational and financial metrics, while also contributing to systemic societal benefits. This body of work reflects a shift from viewing sustainability as compliance-driven to recognizing it as a strategic driver of value creation, a transformation increasingly emphasized in recent corporate sustainability research [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Sustainable banking literature emphasizes the banking sector’s strategic capacity to shape societal and environmental outcomes through capital allocation, product innovation, and risk management practices that integrate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations—encompassing environmental performance (e.g., carbon emissions reduction, resource efficiency), social impact (e.g., employee welfare, community engagement, financial inclusion), and governance quality (e.g., transparency, ethical conduct, stakeholder accountability) [

42,

43]. Empirical studies identify recurring themes such as the expansion of green finance instruments, the incorporation of social inclusion objectives into lending policies, and the adoption of ethical investment criteria [

44,

45]. Evidence from multiple markets demonstrates that banks pursuing sustainability-oriented strategies not only strengthen stakeholder relationships but also enhance long-term financial stability, partly by mitigating environmental and social risks [

46]. Within this framework, sustainable banking is increasingly recognized as a pivotal mechanism for mobilizing resources toward the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—a set of 17 global objectives aimed at eradicating poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring prosperity for all—and for embedding CSR principles into the core functions of the financial system, a role consistently highlighted in recent empirical and conceptual research [

42,

44,

46].

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Corporate governance requires the integration of management, communication, and interaction and provides a framework for how senior executives, who are responsible for the strategic management and direction of the company, should manage relationships with stakeholders. According to the core philosophy underpinning this approach, upper management must consider the views and interests of all stakeholders when making decisions. Adopting corporate governance principles is considered a prerequisite for the success of strategic management, as the senior executives make strategic decisions. Through effective governance, the decision-making processes of top management are conducted in a structured and reliable manner. These strategic decisions impact all employees across the organizational hierarchy, regardless of their managerial status. Consequently, companies that embrace corporate governance principles can enhance organizational success by aligning their strategic choices with broader stakeholder expectations [

47]. In the literature, the concept of CSR is frequently examined within the context of corporate governance frameworks [

10].

The concept of CSR has been defined in various ways throughout the literature. In a widely cited study, Dahlsrud [

3] compiled 37 distinct definitions, demonstrating the diversity of CSR interpretations in academic and institutional contexts. In the present research, emphasis is placed on definitions that reflect sustainability, financial performance, stakeholders, and society. To that end, the following examples—drawn from prominent sources—illustrate key CSR definitions relevant to this study:

CSR is “the overall relationship of the corporation with all of its stakeholders. These include customers, employees, communities, owners/investors, government, suppliers and competitors. Elements of social responsibility include investment in community outreach, employee relations, creation and maintenance of employment, environmental stewardship and financial performance” [

7] (p. 7).

CSR is “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” [

48] (p. 8).

CSR refers to “a set of management practices aimed at reducing the negative impacts of a company’s operations on society while enhancing their positive contributions” [

49] (p. 117).

CSR is “the commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life” [

50] (p. 2).

CSR entails “ethical and transparent business practices that prioritize respect for employees, communities, and the environment, ultimately fostering sustainable business success” [

51] (p. 2).

CSR is defined as “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” [

52] (p. 933).

CSR has evolved “from simple philanthropy to a more theoretical concept with a new corporate philosophy that takes all the interests of all stakeholders into consideration” [

53] (p. 2).

The literature describes various measurement scales (e.g., [

54,

55,

56]) developed to assess perceived levels of CSR. Among these, the Corporate Citizenship scale developed by Maignan and Ferrell [

54], which is based on the notion of citizenship, is particularly prominent. This scale adopts a four-dimensional structure comprising economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary responsibilities. Alternatively, Perez et al. [

55] introduced the Stakeholder-Based CSR scale, which is grounded in Stakeholder Theory. The theoretical foundation of Stakeholder Theory is based on Freeman’s [

36] seminal work

Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, wherein stakeholders are defined as “groups or individuals who can affect or are affected by the achievement of an organization’s objectives” [

36] (p. 25). Rather than embracing a win–lose mindset, Stakeholder Theory advocates for a win–win approach, emphasizing networks of collaboration. The overarching aim is to strengthen internal and external organizational relationships by addressing stakeholder needs, thereby fostering competitive advantage [

57,

58]. The Stakeholder-Based CSR scale comprises five dimensions: shareholders, employees, customers, society, and a general dimension concerning legal and ethical issues. Although the Corporate Citizenship scale is frequently cited in the literature, the Stakeholder-Based CSR scale was developed based on a stakeholder-oriented perspective through a study conducted within the banking sector and is therefore adopted in the present research. The dimensions of this scale are explained as follows [

1,

15,

21,

55]:

Shareholders: This dimension underscores the firm’s orientation toward protecting shareholder interests. To that end, it seeks to increase its profits and exercise cost control. Additionally, the firm aims to ensure organizational sustainability through maintaining long-term continuity in its operations.

Employees: In this dimension, the firm treats its employees impartially, ensuring there is no discrimination or exploitation. It provides a pleasant and safe working environment, pays fair wages, and offers training and career development opportunities.

A general dimension concerning legal and ethical issues: This dimension emphasizes that the firm consistently complies with legal rules and regulations. It strives to fulfill its obligations toward all stakeholders (e.g., customers, suppliers, and shareholders) and never compromises on ethical principles.

Customers: In this dimension, customer satisfaction is viewed as an indicator for improving the firm’s product marketing. The firm seeks to understand customer needs, behaves honestly, develops procedures to address complaints, and ensures that employees provide complete and accurate product information to customers.

Society: This dimension reflects that the firm’s role extends beyond generating economic benefits. Accordingly, the firm aims to improve societal welfare by helping to address social issues. It allocates part of its budget to social projects targeting disadvantaged groups, makes charitable contributions, supports cultural and social events financially, and respects and protects nature.

Empirical studies in the literature have shown that perceptions of CSR are measured based on how organizational stakeholders, such as employees (e.g., [

9,

56,

59]), managers (e.g., [

54]), and customers (e.g., [

14,

31,

55,

60,

61]), perceive CSR practices. In this study, CSR is represented through the society dimension, which reflects an inclusive view encompassing all organizational stakeholders, in line with the approach proposed by Leclercq-Machado et al. [

31], and the level of CSR is assessed based on the perceptions of bank customers.

Although CSR activities are initially perceived as a cost element for firms [

62], such activities enhance a company’s corporate reputation [

17,

18] and image [

4]. Moreover, CSR initiatives strengthen customer trust in the firm [

63]; promote customer citizenship behavior, including voluntary support, positive word-of-mouth, and proactive engagement with the firm’s services [

64]; foster consumer [

19,

20] and employee [

65] green behaviors; enhance customer satisfaction [

15,

66]; evoke customer gratitude [

67]; boost customer engagement [

19,

60]; and reinforce customer–firm identification [

15,

20,

68,

69]. These empirical findings clearly demonstrate that CSR activities contribute not only to organizational outcomes but also to society. At this point, the antecedents of CSR gain importance. Petrenko et al. [

70] classify CSR antecedents into internal factors (e.g., executive incentives, values, and characteristics) and external factors (e.g., legal regulations, media attention, and competitive pressure), depending on the organizational context and environmental conditions. In particular, the CSR strategies adopted by firm management play a critical role in shaping CSR practices. These strategies can be categorized as either reactive or proactive. Reactive strategies refer to preventive approaches implemented by firms that lack social responsibility sensitivity and tend to avoid such activities. In contrast, proactive strategies are carried out by socially responsive and voluntarily engaged firms that take a leading role in CSR initiatives, for instance organizations that embrace a modern managerial approach [

21,

71,

72].

Among the topics examined alongside CSR in the literature are emotions and financial performance.

2.3. Customer Emotions

Emotions are a psychological phenomenon that inherently involves interdisciplinary perspectives [

15,

17,

20,

33,

73]. In the English-language literature, this phenomenon is represented by the terms

affect [

74],

affectivity [

75],

affective state [

76],

mood state [

77], and

emotions [

73]. In the present study, the term

emotions is deliberately chosen, drawing on prior empirical studies (e.g., [

15,

33]) that examine the emotional responses of banking customers.

Neutral emotions have recently attracted scholarly attention as an emerging dimension in affective research, offering nuanced insights into emotional experiences that do not align strictly with positive or negative valence [

78]. However, this study focuses on the two widely established dimensions of emotions: positive and negative [

33,

79]. To operationalize these emotional dimensions, various measurement scales (e.g., [

33,

79]) have been developed. According to Watson et al. [

79], positive emotions are represented by adjectives such as

interested,

excited,

strong,

enthusiastic,

proud,

alert,

inspired,

determined,

attentive, and

active, while negative emotions are reflected through descriptors such as

distressed,

upset,

guilty,

scared,

hostile,

irritable,

ashamed,

nervous,

jittery, and

afraid. Whereas Watson et al. [

79] introduced an extensive range of adjectives to capture positive and negative emotions, Razzaq et al. [

33] concentrated on a more concise set of emotional indicators specific to banking contexts, identifying

enthusiastic,

joyful, and

happiness as indicators of positive emotions and

angry,

sad,

regretful,

irritable, and

disappointed as indicators of negative emotions. Due to their theoretical foundations [

33,

79,

80] and statistical characteristics [

75,

76,

80], positive and negative emotions are treated as mutually exclusive constructs that cannot be aggregated. According to empirical studies (e.g., [

17,

20,

75,

76]), these two constructs are significantly and negatively correlated with one another.

In empirical studies within the field of business science, emotions are typically examined in the context of both employees (e.g., [

59]) and customers (e.g., [

17]). In the present study, the levels of positive and negative emotions among banking customers are measured in a manner consistent with the approach adopted by Razzaq et al. [

33]. Emotional responses vary depending on individuals’ mood states. In the literature, emotional levels are assessed using different temporal criteria such as

momentary,

today,

in the last few days,

last week,

over the past few weeks,

last year, and

generally [

79,

81]. Numerous empirical studies (e.g., [

9,

15,

21,

33]) have predominantly utilized the criterion of general mood state when measuring emotions. Accordingly, the current study examines how customers generally feel while receiving or having received service from their bank. Furthermore, emotional responses toward the firm and the service it provides are not treated as distinct variables. Instead, as in several prior studies [

17,

19,

20,

21,

33], they are considered as a single evaluative construct. This is because customers’ feelings toward the firm are assumed to be represented by their emotional experiences during and after service encounters.

Positive emotions contribute to individuals’ psychological well-being and facilitate social engagement [

82,

83]. In contrast, negative emotions may lead to undesirable outcomes, such as anxiety and depression [

84]. Among customers, positive emotions tend to boost satisfaction [

15] and encourage green consumer behavior [

20], while negative emotions may reduce satisfaction [

85] and weaken ethically minded consumer behavior [

86]. Positive emotions also foster customer–company identification [

20] and cultivate loyalty toward the company with which the customer interacts [

15]. Conversely, negative emotions weaken customers’ loyalty toward the companies from which they purchase [

85]. Considering these insights, it is evident that while individuals’ positive emotions benefit the individual, the organization, and society, their negative emotions exert harmful effects across these domains. Accordingly, the antecedents of individuals’ positive and negative emotions become particularly salient. Personality traits [

76] as well as organizational and environmental factors [

20,

87] have been identified as key determinants of emotional responses.

Among the topics in which emotions are jointly examined in the literature are CSR and corporate reputation, the latter of which encompasses financial performance as a key subdimension [

32].

2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility and Customer Emotions

Empirical studies in the literature have predominantly examined the relationship between CSR and individuals’ emotions through the perceptions of either employees (e.g., [

9,

59,

88,

89]) or customers (e.g., [

15,

17,

19,

20,

21]). In the scope of the present study, the focus is specifically placed on customer perceptions. According to the existing empirical research, perceived CSR is positively and significantly associated with customers’ positive emotions [

15,

17,

20,

21] and negatively and significantly associated with customers’ negative emotions [

17,

20]. Furthermore, perceived CSR has been shown to positively and significantly predict customers’ positive emotions [

15,

17,

19,

20,

21], while negatively and significantly influencing their negative emotions [

17,

20]. These studies have explored the link between perceived CSR and customer emotions across diverse samples, including hotel guests in China [

17,

20] and Pakistan [

19], as well as banking customers in Spain [

15] and Turkey [

21].

Based on theoretical and empirical insights from the literature, this study, conducted among banking customers in Ankara, the capital of Turkey, anticipates that an elevated perception of their bank’s fulfillment of CSR will strengthen customers’ positive emotions toward the institution while simultaneously attenuating their negative emotions.

2.5. Financial Performance

Corporate reputation is increasingly understood as a socially constructed, multidimensional perception that emerges from stakeholders’ interpretations of an organization’s past actions, current performance, and projected future behavior [

90]. Cintamür [

91] developed a corporate reputation scale specific to the banking sector, based on customers’ perceptions. This scale comprises four dimensions: financial performance and financially strong company, customer orientation, social and environmental responsibility, and trust. The researcher assesses a bank’s financial performance through customer evaluations of the bank’s economic strength, profitability, and continuity [

91]. Within the scope of this study, the dimension of the corporate reputation scale labeled financial performance and financially strong company is the focal point; this dimension is referred to as financial performance based on the items that functionally define it.

A company’s financial performance can be assessed from various perspectives, including profitability ratios (e.g., ROE and ROA), liquidity ratios (e.g., current ratio), operational efficiency ratios (e.g., asset turnover rate), and market performance indicators (e.g., earnings per share). Although these indicators offer valuable insights when examined individually, a more accurate evaluation arises from a holistic approach that considers them collectively [

92] (pp. 73–82). In most studies (e.g., [

16,

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

93]) in the literature, financial performance has been measured using secondary data sources such as market value and profitability. However, some studies have relied on perceptual data gathered from employees [

23] or customers [

32,

91]. Building on these works, the present study assesses the financial performance of banks based on customer perceptions obtained via a survey.

Various factors influence a company’s financial performance, including liquidity, firm size, and debt levels. Although such metrics are conventionally derived from financial statements [

94], this study interprets them through the lens of customer perception. Customers do not assess a bank’s financial performance by analyzing balance sheets, but rather by responding to indirect signals such as service quality, institutional image, and operational consistency that convey impressions of economic strength, profitability, and continuity [

95]. These impressions collectively shape the perceived financial performance dimension of corporate reputation [

32,

91]. Among these, corporate governance stands out as a prominent determinant [

93]. In Gruszczynski’s [

96] study on companies listed on the Polish stock exchange, corporate governance levels were found to be associated with firms’ capacity to manage financial challenges. Similarly, Amba [

97] demonstrated that governance structures, such as the presence of institutional investors and the role of the Audit Committee Chair, significantly affect financial performance measured via return on assets (ROA). Kyere and Ausloos [

98] analyzed non-financial firms in the United Kingdom and showed that sound governance mechanisms positively influence performance indicators such as the ROA and Tobin’s Q. Leng [

99], focusing on Malaysian companies, highlighted the impact of debt ratio, firm size, and institutional ownership on financial performance, as represented by return on equity (ROE). In a study on Italian firms, Rossi et al. [

100] identified a negative relationship between governance quality and Tobin’s Q, but a positive association with ROE. Collectively, these studies underscore the multifaceted role of corporate governance in shaping firm performance across different contexts and indicators.

Like the relation between corporate governance, which incorporates CSR principles within its framework, and financial performance, there is naturally a clear relation between CSR and financial performance [

101]. In addition, the literature discusses emotional dimensions, including positive and negative feelings, alongside corporate reputation, which encompasses financial performance.

2.6. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance

A growing body of scholarly research highlights the positive influence of CSR on firms’ financial performance across various institutional and sectoral contexts. Karagiorgos [

24] demonstrated a statistically significant and positive effect of CSR scores, measured through sustainability reports prepared in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative guidelines, on stock returns among publicly listed Greek firms, using actual market-based financial data, and providing evidence that socially responsible behavior can enhance market-based financial outcomes. From an internal stakeholder perspective, Cazacu et al. [

23] found that employees’ perceptions of CSR significantly shaped their evaluations of firms’ financial performance in a large-scale survey conducted on Romanian companies, relying exclusively on perceived (subjective) assessments of financial outcomes. Mishra and Suar [

27] further reinforced this association by combining perceptual data from senior managers regarding CSR with actual financial indicators such as return on assets, obtained from secondary sources. Although their study did not directly test the alignment between perceived and actual financial performance, the use of both data types suggests a potential link between CSR perceptions and objectively measured financial outcomes. Extending this line of inquiry to the banking sector, Siueia et al. [

16] analyzed panel data from leading banks in Mozambique and South Africa and reported that voluntary CSR disclosures had a statistically significant and positive impact on financial performance, based on actual accounting indicators such as return on assets and return on equity. Adding to this body of research, Li et al. [

26] examined Chinese publicly listed firms using a threshold regression approach and found that CSR—measured through a composite index covering seven stakeholder dimensions (shareholders, creditors, customers, suppliers, employees, government, and community)—has a positive and statistically significant impact on accounting-based financial performance (ROA, with ROE as a robustness check). Similarly, Arian et al. [

22], using longitudinal panel data from Australian publicly listed firms between 2007 and 2021, found that higher CSR (Environmental, Social, and Governance—ESG) performance scores have a positive and statistically significant effect on both market-based (Tobin’s Q) and accounting-based (ROA) financial performance, with the effect being particularly strong in consumer-oriented industries. In line with these findings, Lee et al. [

25], examining publicly listed firms in China, reported that CSR—both in its strategic and altruistic forms—has a positive and statistically significant effect on market-based financial performance (Tobin’s Q).

Collectively, these studies underscore the strategic relevance of CSR in shaping both market-based and accounting-based financial outcomes across diverse organizational and institutional settings, while indicating that financial performance was assessed through actual data in most cases, with Cazacu et al. [

23] standing out as a notable example where perceived evaluations were used to examine the CSR–financial performance link.

Building on insights from the existing literature, this study posits that as customers perceive their bank to be more actively engaged in CSR, their evaluations of the bank’s financial performance will be positively influenced.

2.7. Financial Performance and Customer Emotions

According to empirical findings in the literature, customers’ positive perceptions of corporate reputation are significantly and positively associated with positive emotions [

17,

29], while a significant and negative relationship also exists with negative emotions [

17,

28,

30]. Furthermore, strengthened customer perceptions of corporate reputation have been shown to significantly enhance positive emotions [

17,

29] and reduce negative emotions [

17,

28]. In the literature, the relationship between perceived corporate reputation and customer emotions has been examined across diverse samples, including hotel customers in China [

17], university students in the United States who frequently shop online for clothing [

29], and bank customers in Turkey who submitted complaints on online platforms following negative service experiences [

28].

Originally developed by Spence [

102] in the context of labor market dynamics, Signaling Theory explains how entities convey quality or credibility under information asymmetry. Extending this perspective to corporate contexts, a firm’s strong financial performance serves as a strategic cue to external stakeholders, signaling reliability and success. These signals foster positive emotional responses among customers, particularly admiration [

95]. Complementing this perspective, Appraisal Theory suggests that customers cognitively evaluate such financial outcomes in relation to their personal goals and expectations. This appraisal process elicits emotions, such as admiration or disappointment, depending on whether the performance is perceived as congruent or incongruent with their internal standards [

103].

Within the scope of this study, considering that financial performance constitutes a subdimension of corporate reputation [

32], and based on Signaling Theory [

95] and Appraisal Theory [

103], as well as the existing empirical findings in the literature, it is expected that an increase in bank customers’ perceived level of their bank’s financial performance will strengthen the positive emotions they feel toward the bank while weakening their negative emotions.

2.8. Studies Testing Similar Research Models

In the literature, studies [

17,

18] examining interactions conceptually similar to those explored in the present study have been identified. Drawing on survey data collected from hotel guests in China, Su et al. [

17] demonstrated that customers’ perceptions of a hotel’s CSR initiatives significantly and positively predict their evaluations of the hotel’s corporate reputation. Furthermore, elevated perceptions of both CSR and corporate reputation were found to reinforce customers’ positive emotions and attenuate their negative emotions toward the hotel. These findings highlight the pivotal role of both CSR and corporate reputation in shaping consumers’ emotional responses toward hotels. Similarly, based on survey data gathered from Spanish consumers regarding Coren, Castro-Gonzalez and Vilela [

18] demonstrated that perceptions of the company’s CSR initiatives significantly and positively influenced its perceived corporate reputation. In turn, corporate reputation was found to enhance consumers’ admiration for the company. Additionally, perceptions of CSR were shown to directly foster admiration, suggesting that both CSR and corporate reputation play key roles in shaping affective consumer responses.

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

Considering the insights presented in the preceding sections, high-quality CSR significantly and positively predicts customers’ positive emotions (e.g., [

15,

17,

19,

20,

21]), while it significantly and negatively predicts their negative emotions (e.g., [

17,

20]). Moreover, high-quality CSR exerts a significant and positive effect on the firm’s financial performance (e.g., [

16,

23,

24,

27]). A strong corporate reputation, which encompasses high financial performance [

32], also significantly and positively predicts customers’ positive emotions (e.g., [

17,

29]), while significantly and negatively predicting their negative emotions (e.g., [

17,

28]). Taken together, CSR serves as an antecedent of both the firm’s financial performance and customer emotions, while financial performance itself is likely to serve as an antecedent of customer emotions. This pattern suggests the potential mediating role of financial performance within a mechanism involving CSR, financial performance, and customer emotions.

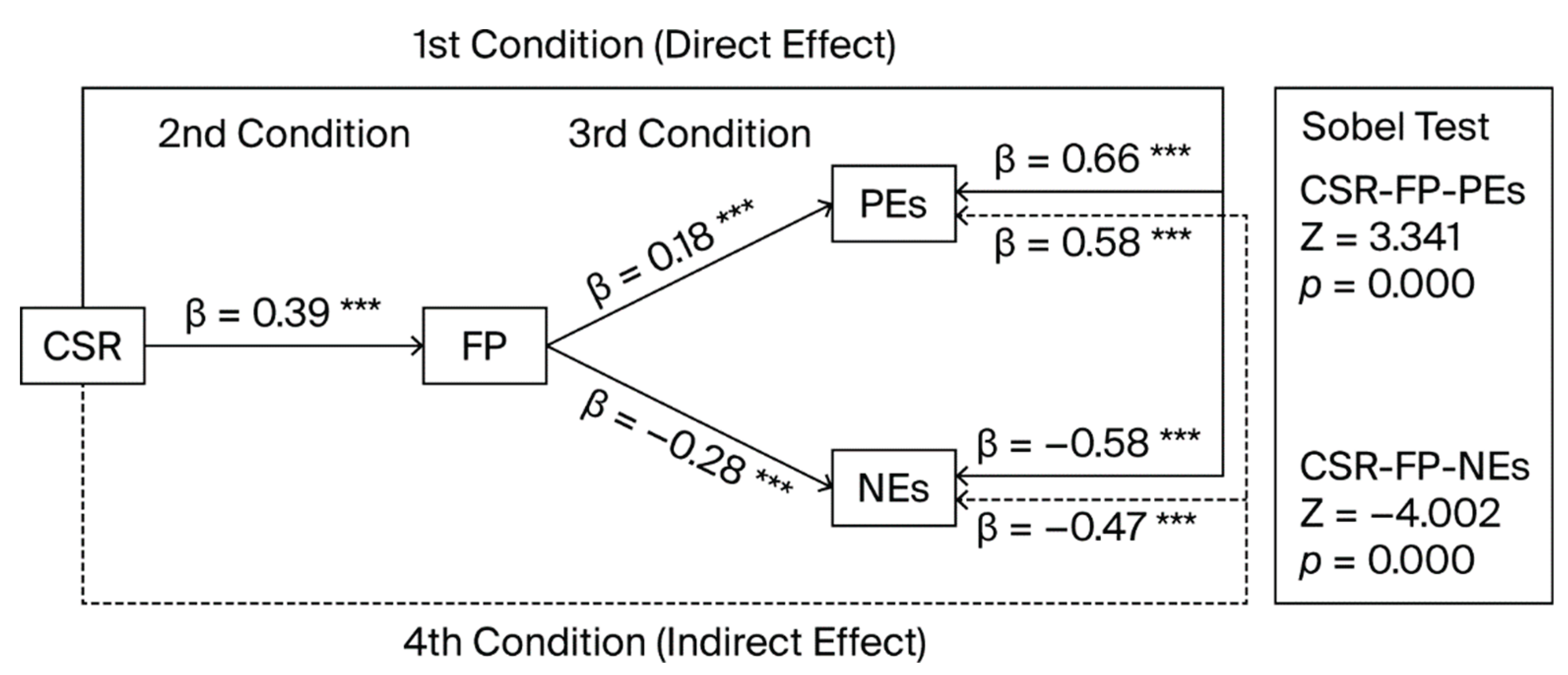

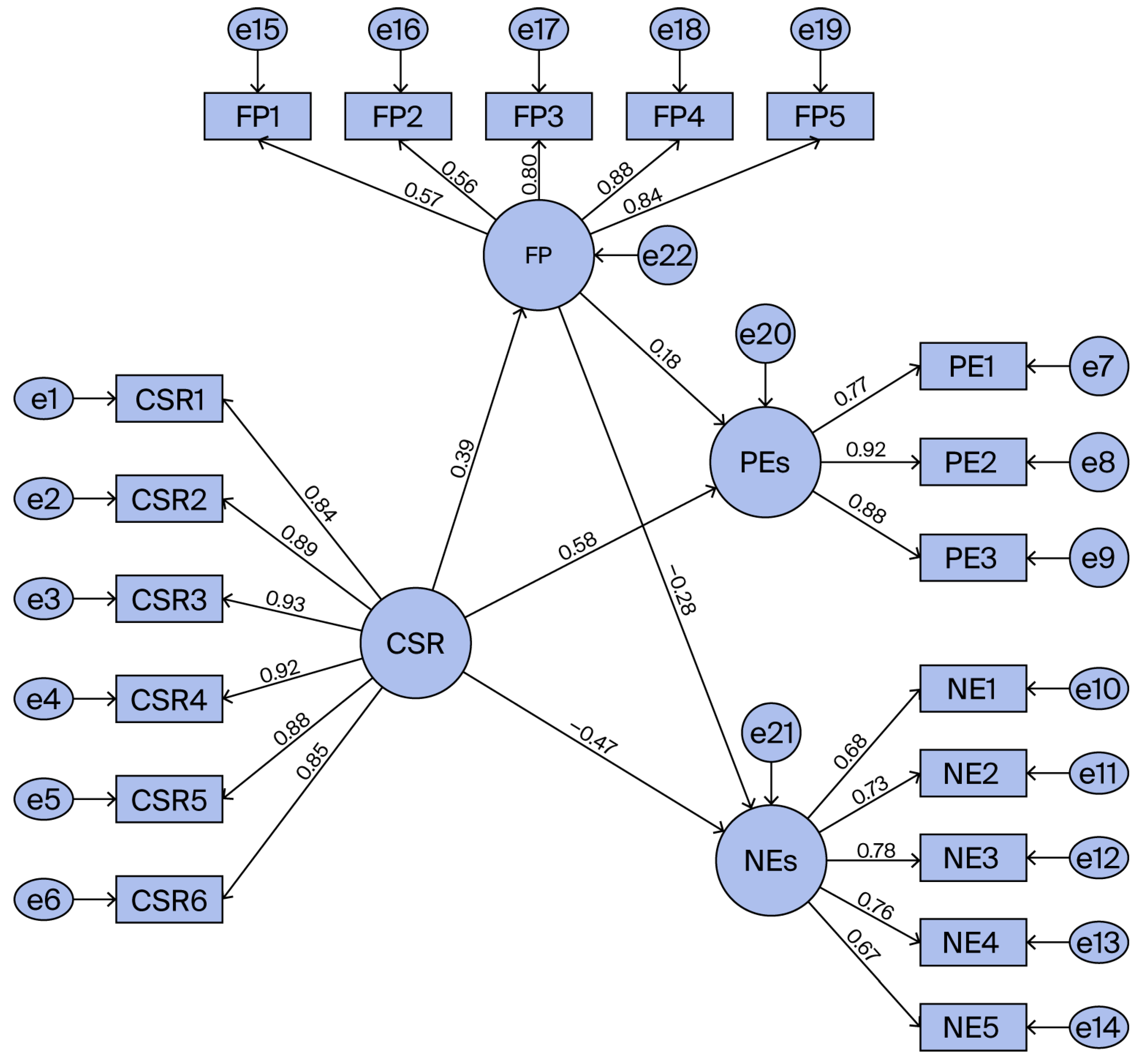

Building upon the aforementioned theoretical and empirical foundations, this study’s research model was constructed (see

Figure 1), and the corresponding hypothesis was formulated.

Research hypothesis: Customers’ perceptions of the bank’s financial performance mediate the relationships between their CSR perceptions and the positive and negative emotions they feel toward the bank.

The following sections of this paper detail the methodology employed in the research and the findings obtained through empirical analysis.

4. Methodology

4.1. Procedure and Analysis Approach

This subsection provides details on the timing and methods of data collection, as well as the sequence and software used for statistical analysis. A quantitative research design was employed in this study. Upon receiving ethical approval from Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University (approval no. 295799, dated 25 September 2024), questionnaires were distributed and collected using a sealed envelope method between 25 and 27 November for the pilot study and between 2 and 30 December 2024 for the main study. Data were entered into SPSS 24.0, and preliminary screening procedures were conducted to ensure readiness for analysis. The construct validity of the research model was examined via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS 24.0. To assess common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted in SPSS 24.0, and a common latent factor analysis was performed in AMOS 24.0. SPSS 24.0 was used to calculate the means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Pearson correlation analysis was also performed in SPSS 24.0, and maximum shared variance (MSV) and average shared variance (ASV) values were subsequently calculated using the obtained correlation coefficients. Standardized factor loadings obtained through CFA served to calculate composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and the square root of AVE (√AVE). The research hypothesis was initially tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) via AMOS 24.0 and subsequently analyzed using the Sobel test within an interactive environment. All analyses were conducted at a 95% confidence level, with results interpreted based on a statistical significance threshold of p < 0.05, thereby ensuring methodological rigor and empirical robustness.

Except for CR, AVE, √AVE, MSV, and ASV, all statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 24.0, AMOS 24.0, or an interactive environment (e.g., the Sobel test). The five indices were manually calculated using the formulas in Hair et al. [

104].

4.2. Sample

The target population of the research consisted of private bank customers residing in Ankara. A non-probability sampling method, specifically convenience sampling, was employed. Between 2 and 30 December 2024, the principal investigator administered structured questionnaires to adults aged 18 and above from his personal network—family members, extended relatives, personal friends, family friends, neighbors, students, and work colleagues. All participants took part in the survey on a voluntary basis and submitted their completed questionnaires in the original sealed envelopes within one week of distribution. Of the 630 distributed questionnaires, 509 were returned, yielding a response rate of approximately 81%. Only 426 questionnaires were properly completed. The sample size was finalized following preliminary analyses (data-accuracy checks, missing-data screening, normality testing, and multivariate outlier identification) to ensure suitability for statistical testing.

4.3. Instruments

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of four sections.

4.3.1. CSR Scale

In the first section, customers’ perceived level of CSR was measured using the six-item

society subdimension of the 22-item Stakeholder-Based CSR scale developed by Perez et al. [

55]. In their original research conducted with banking customers in Spain, a reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.888 for this subdimension. The scale was subsequently adapted into Turkish by Akbaş Tuna et al. [

1], who applied it to a sample of bank customers in Ankara and reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 for the same dimension. Furthermore, Leclercq-Machado et al. [

31] used the

society subdimension of the Stakeholder-Based CSR scale to assess perceived CSR among private bank customers in Peru, reporting Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values of 0.909 and 0.929, respectively. In the present study, the items in the first section of the questionnaire were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

4.3.2. Financial Performance Scale

In the second section of the questionnaire, the perceived financial performance of the bank was measured using the five-item

financial performance and financially strong company subdimension of the 20-item Customer-Based Corporate Reputation (CBCR) scale, originally developed by Cintamür [

91]. The English version of the scale was later published by Cintamür and Yüksel [

32]. In their longitudinal study conducted with private bank customers in Istanbul, the researchers calculated composite reliability values of 0.919 and 0.891 for this subdimension across two phases of data collection. In the present study, the items in the second section of the questionnaire were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely unrepresentative) to 5 (definitely representative).

4.3.3. Emotions Scale

In the third section of the questionnaire, customers’ levels of positive and negative emotions toward the bank were measured using two scales developed by Razzaq et al. [

33], based on the emotion frameworks introduced by Richins [

105] and Laros and Steenkamp [

80]. The positive emotions scale comprised three items, while the negative emotions scale consisted of five items. In their study conducted with bank customers in China, Razzaq et al. [

33] reported composite reliability values of 0.881 for positive emotions and 0.933 for negative emotions. In the present study, the items in the third section of the questionnaire were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very little or not at all) to 5 (extremely).

In this study, computed scores for the scales were interpreted such that lower values indicated lower levels of the respective construct, while higher values reflected higher levels. Participants were instructed to respond to items in the first three sections by considering only one of the private banks with which they maintained a customer relationship. The final section of the questionnaire included a single demographic item regarding the participants’ gender.

5. Results

5.1. Pilot Study

For the pilot study, a total of 52 questionnaires were collected using a convenience sampling method, of which 44 were properly completed and included in the pilot dataset. According to the results of the reliability analysis, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) values for the variables included in the study ranged between 0.842 and 0.951. These values exceed the critical threshold of 0.70 suggested by Hair et al. [

104], indicating acceptable reliability. Following the pilot study, and upon confirming the face validity of the questionnaire, the main study was initiated.

5.2. Preliminary Analyses

In this study, which does not include any reverse-coded scale items, preliminary analyses were conducted for the purpose of checking and preparing the dataset, following the procedures recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell [

106], namely, the accuracy of the dataset, missing data, normality testing, and multivariate outliers. Initially, the dataset’s accuracy was examined. This inspection confirmed that, given the 5-point Likert scales employed, every item response lay within the expected 1–5 range and that no anomalous values (e.g., a “6” on a 5-point scale) were present. Moreover, it was observed that, for all measured variables, the item means exceeded their respective standard deviations, with no missing data detected. Although the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test yielded

p = 0.000 (

p < 0.05) for all items—technically rejecting strict normality—skewness values (–0.788 to 0.574) and kurtosis values (–0.536 to 0.475) fell within the acceptable ±1.5 bounds, supporting an assumption of approximate normality and justifying parametric analyses. Mahalanobis distances for each participant ranged from 2.37 to 45.65, all below the cut-off value of 124.34 (

p < 0.001), indicating no multivariate outliers [

106]. As a result of the preliminary analyses, no participants were excluded, and the final sample size was confirmed as 426. According to Saunders et al. [

107], a sample size of 384 is sufficient to represent a population of 10 million with a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error. Considering that the population of Ankara is below 6 million [

108], the final sample (n = 426) is deemed representative of private bank customers in Ankara. Of the participants included in the dataset, 201 were female and 225 were male.

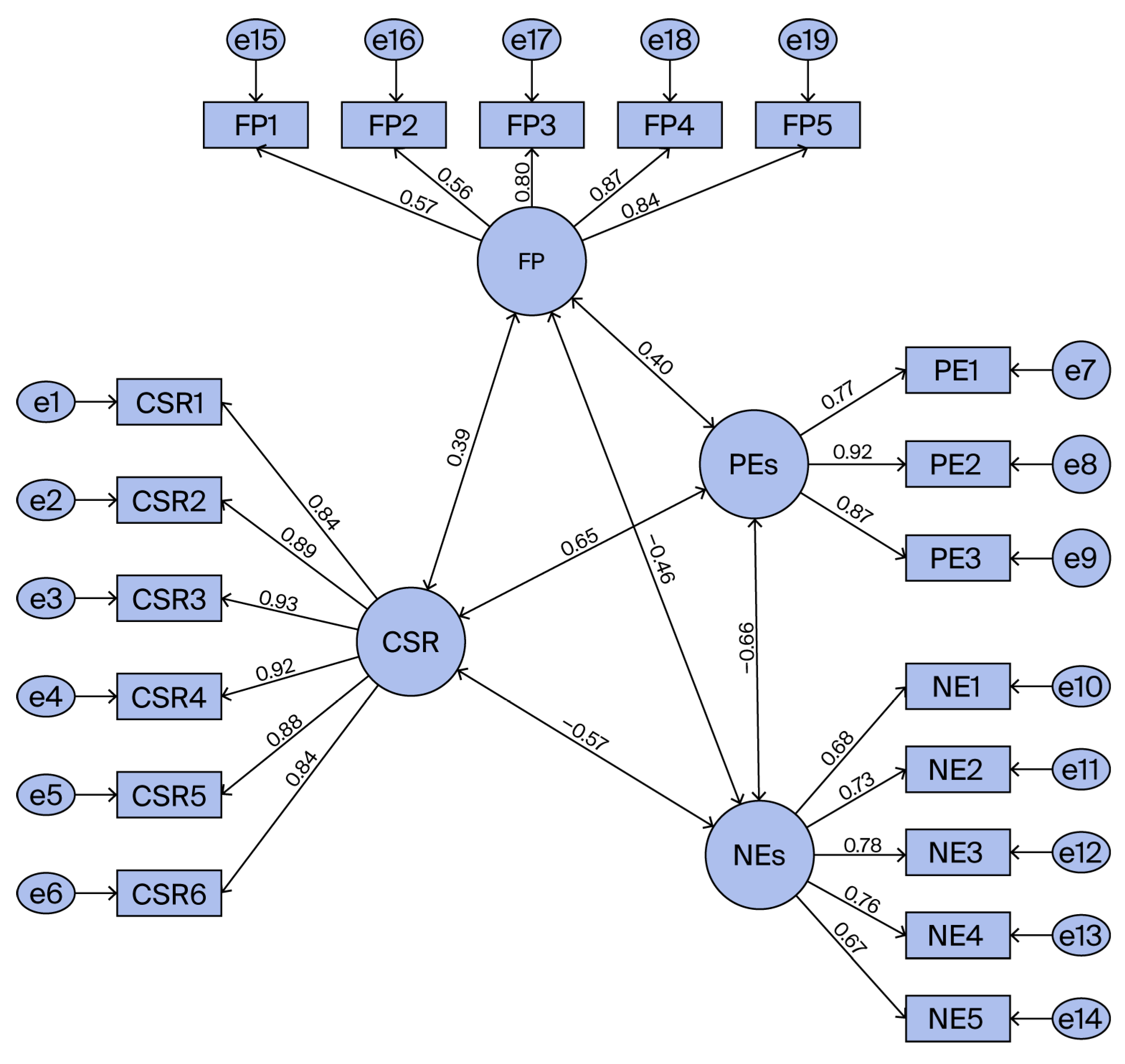

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

According to Anderson and Gerbing [

109], the construct validity of a model should first be assessed prior to testing the research model via SEM. In this study, an overall CFA was conducted in AMOS 24.0 via maximum likelihood estimation, based on a research model comprising four latent variables and nineteen observed items. Following the recommendations of Hair et al. [

104], the analysis examined factor loadings, standard error covariances, and modification indices. The results indicate that all scale items were statistically significant. As presented in

Figure 2 and

Table 1, standardized path coefficients ranged from 0.840 to 0.931 for the CSR scale, 0.558 to 0.875 for the financial performance scale, 0.772 to 0.923 for the positive emotions scale, and 0.674 to 0.776 for the negative emotions scale. All factor loadings exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.40 [

104], demonstrating satisfactory measurement properties.

Additionally, as shown in

Table 2, the model’s fit indices were found to be within acceptable thresholds [χ

2/df = 4.193, TLI = 0.910, IFI = 0.923, CFI = 0.923, RMSEA = 0.087], thereby confirming its construct validity. Notably, this validation was achieved without combining error terms or removing any scale items, providing a robust foundation for testing the structural hypothesis in the subsequent modeling phases.

5.4. Common Method Bias Assessment

Due to the cross-sectional design of this study, common method variance (CMV) was considered a potential source of measurement error. CMV refers to the variance attributable to the measurement method rather than to the constructs being measured [

114]. To assess its presence, we first conducted Harman’s single-factor test [

115], in which all measurement items were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis using unrotated principal component extraction. The results indicated that a single factor accounted for 42.148% of the total variance. As this value falls below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%, CMV does not appear to pose a substantial threat to construct validity [

111].

To further examine the potential influence of CMV, a Common Latent Factor (CLF) was incorporated into the measurement model. The CLF is a non-theoretical latent construct introduced solely for statistical control purposes and was linked to all observed variables to capture any systematic bias attributable to the measurement method [

116]. Unlike substantive constructs, the CLF does not represent any conceptual variable in the study. To evaluate its effect, we compared the model fit indices obtained after including the CLF [χ

2/df = 4.222, TLI = 0.909, IFI = 0.923, CFI = 0.923, RMSEA = 0.087] with those from the original CFA. Since the inclusion of the CLF did not improve the fit indices (see

Table 2), common method bias can be ruled out as a significant concern in this study.

5.5. Validity, Reliability, and Correlation Analyses

Table 3 reports the outcomes of the validity, reliability, and correlation analyses conducted in this study, comprising convergent validity, discriminant validity, composite reliability, internal consistency, and inter-construct correlations based on Pearson coefficients.

Based on

Table 3, convergent validity for each variable was established since the criteria of AVE > 0.50, CR > 0.70, and CR > AVE [

117,

118] were all met. Similarly, discriminant validity for each variable was confirmed given that AVE > MSV, AVE > ASV, and √AVE values exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations [

118,

119]. The lowest Cronbach’s alpha (α) value among the variables reported in

Table 3 was 0.845, which is well above the critical threshold of 0.70 [

104]. Therefore, all measurement scales used in this study demonstrate acceptable reliability.

According to the Pearson correlation analysis results presented in

Table 3, the gender variable does not exhibit a statistically significant relationship with the variables included in the research model. In contrast, perceived CSR is positively and significantly associated with the bank’s perceived financial performance (r = 0.353;

p < 0.01) and customers’ positive emotions (r = 0.612;

p < 0.01). Furthermore, perceived financial performance shows a significant and positive relationship with customers’ positive emotions (r = 0.354;

p < 0.01). Conversely, customers’ negative emotions are negatively and significantly correlated with perceived CSR (r = −0.528;

p < 0.01), perceived financial performance (r = −0.448;

p < 0.01), and customers’ positive emotions (r = −0.585;

p < 0.01). According to Cohen’s [

120] classification, correlation coefficients are interpreted as follows: values below 0.10 indicate a very weak relationship, values ranging from 0.10 to 0.29 represent a weak relationship, values between 0.30 and 0.49 reflect a moderate relationship, and values of 0.50 or higher indicate a strong relationship between variables. In this context, the relationship between perceived CSR and the bank’s perceived financial performance is of moderate strength. Similarly, perceived financial performance is moderately correlated with customers’ positive and negative emotions. Moreover, perceived CSR exhibits strong correlations with customers’ positive and negative emotions, and there is also a strong association between customers’ positive and negative emotions.

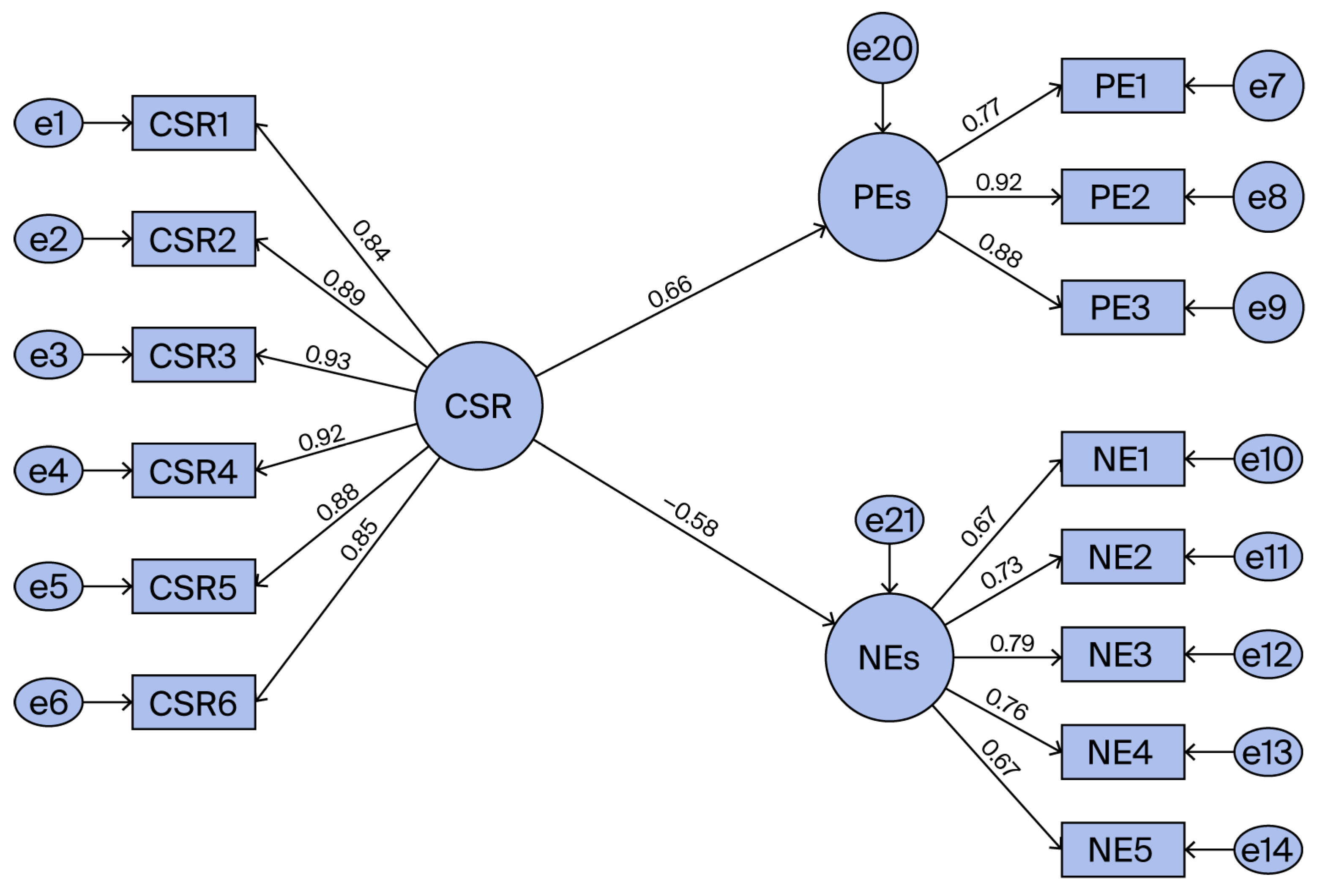

5.6. Testing the Research Hypothesis

Following the validity, reliability, and correlation analyses, the research hypothesis was tested. According to previous studies in the literature [

111,

121], a minimum sample size of 200 is required to conduct SEM. Given that the dataset in this study comprised 426 participants, the research hypothesis was tested using SEM through AMOS 24.0 software. Subsequently, the hypothesis was further examined in an interactive environment using the Sobel test. To assess mediation, the four-step procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny [

122] was adopted. In this context, the first condition was tested by constructing an initial SEM that included only the independent and dependent variables, as shown in

Figure 3. The fit indices obtained from this initial model [χ

2/df = 3.318; TLI = 0.955; IFI = 0.963; CFI = 0.963; RMSEA = 0.074] were compared with the threshold values presented in

Table 2 and found to be acceptable. Accordingly, the study continued without merging error terms or excluding any items from the measurement model. The results of the initial SEM indicated that customers’ perceptions of CSR significantly and positively influenced their positive emotions toward the bank (β = 0.66;

p < 0.001), while significantly and negatively influencing their negative emotions (β = –0.58;

p < 0.001). Thus, the first condition required for testing the mediation hypothesis was satisfied (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix A).

After confirming the first condition, a second structural equation model was constructed by adding the mediating variable to the initial model to examine the remaining conditions, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The fit indices obtained from this second model [χ

2/df = 4.533; TLI = 0.900; IFI = 0.914; CFI = 0.914; RMSEA = 0.091] were compared with the threshold values in

Table 2 and found to be acceptable. Accordingly, the study proceeded without merging error terms or removing any items from the measurement model. The results from the second SEM showed that customers’ perceptions of CSR significantly and positively influenced their perceptions of the bank’s financial performance (β = 0.39;

p < 0.001). In turn, perceived financial performance significantly and positively affected customers’ positive emotions toward the bank (β = 0.18;

p < 0.001) while significantly and negatively affecting their negative emotions (β = −0.28;

p < 0.001). Thus, the second and third conditions required for testing mediation were met. Moreover, perceived CSR continued to have significant effects on both positive and negative emotions, similar to the initial model. However, the indirect effects in the second model (β = 0.58 and −0.47,

p < 0.001, respectively) were weaker than the direct effects observed in the first model (β = 0.66 and −0.58,

p < 0.001, respectively), thereby fulfilling the fourth mediation condition. This indicates that perceived financial performance plays a partial mediating role within the research framework. Once all four conditions for mediation were satisfied through SEM, the significance of the mediating effects of perceived financial performance was tested. The Sobel test results [

123] confirmed that perceived financial performance significantly mediated the relationships between perceived CSR and customers’ positive emotions (z = 3.341;

p < 0.001) and between perceived CSR and their negative emotions (z = −4.002;

p < 0.001) (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix A). Consequently, the research hypothesis was supported, and the perceived financial performance was found to serve a partial mediating role within the proposed model.

6. Discussion

6.1. Originality of the Study

This study presents an investigation of the mediating role of perceived financial performance in the effect of bank customers’ perceptions of CSR on their emotional responses, both positive and negative, toward the bank. A comprehensive review of the literature identified a limited number of empirical studies [

17,

18] that examined triadic relationships among the variables included in the research model or closely related constructs within a similar framework. However, no previous study has simultaneously explored these variables within a unified model. This gap clearly demonstrates the present study’s contribution to the literature and its originality. Moreover, the focus on private banks is grounded in the functional definition of financial performance [

32], which emphasizes the criterion of profitability. In addition, all measurement scales employed in the study [

33,

55,

91] were originally developed through research conducted with bank customers and exhibit a high degree of compatibility with the sample used in this study. These elements enhance both the methodological rigor and contextual validity of the research. Considering the nature of the variables, the structure of the research model, and the characteristics of the sample, this study is situated at the intersection of multiple disciplines, including strategic management, industrial and organizational psychology, social work, finance, and marketing. By integrating paradigms from these diverse fields within a holistic framework, this study offers valuable theoretical and practical contributions through an interdisciplinary lens.

6.2. Alignment with Prior Empirical Evidence

The findings revealed a significant and positive relationship between perceived CSR and perceived financial performance, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., [

16,

24,

27]). In addition, the results show that both perceived CSR (e.g., [

15,

17,

20,

21]) and perceived financial performance (e.g., [

17,

29]) are positively and significantly associated with customers’ positive emotions toward the bank. These findings are in line with the existing literature. Conversely, perceived CSR (e.g., [

17,

20]) and perceived financial performance (e.g., [

17,

28,

30]) were found to be negatively and significantly associated with customers’ negative emotions, results that align with prior empirical evidence. Taken together, these findings provide a solid foundation for examining the mediating role of perceived financial performance within the proposed model. In line with previous studies (e.g., [

16,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]), the findings indicate that customers’ perceptions of CSR have a significant and positive direct effect on their perceptions of the bank’s financial performance. Likewise, the result that perceived financial performance significantly and positively influences customers’ positive emotions (e.g., [

17,

29]) and significantly and negatively influences their negative emotions (e.g., [

17,

28]) is also consistent with the existing literature. Furthermore, the finding that perceived CSR significantly and positively affects customers’ positive emotions (e.g., [

15,

17,

19,

20,

21]), and significantly and negatively affects their negative emotions (e.g., [

17,

20]), aligns with prior empirical evidence. Given that these effects occur both directly and indirectly through perceived financial performance, the results confirm the role of financial performance as a partial mediator in the proposed model. As emphasized by MacKinnon et al. [

124], partial mediation is more prevalent and realistic than full mediation, particularly in the context of social science research.

6.3. Functional Interpretation of Results

The findings are best understood through the functional definitions of the model’s constructs [

33,

55,

91] as follows:

As customers’ perceptions that their bank fulfills its social responsibilities toward society become stronger, their perceptions of the bank’s performance (particularly with respect to profitability and continuity) also improve.

As customers’ perceptions of their bank’s performance (particularly regarding profitability and continuity) improve, their positive emotional responses toward the bank become stronger, while their negative emotional responses diminish.

Additionally, as customers’ perceptions that their bank fulfills its social responsibilities toward society increase, their positive emotional responses toward the bank become stronger, while their negative emotional responses diminish. These relationships are further reinforced by the fact that bank customers’ stronger perceptions that their bank fulfills its social responsibilities toward society enhance their perceptions of the bank’s performance (particularly with respect to profitability and continuity).

6.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

In light of these findings, it is concluded that within the scope of this study, it is possible for customers’ emotional responses toward the bank to be improved as a result of the reinforcing impact of strengthened CSR perceptions on their evaluations of the bank’s financial performance. Based on Attitude Theory, which posits that an individual’s attitude is a determinant of behavior [

125], and on the view that attitudes are commonly conceptualized as comprising cognitive, affective, and conative (behavioral intention) components [

126], ultimately, this emotional improvement can translate into concrete contributions to the bank, such as increased customer satisfaction, long-term loyalty, and enhanced customer citizenship behavior, including voluntary support, positive word-of-mouth, and proactive engagement with the bank’s services. This mechanism reveals that perceived CSR affects customer emotions both directly and indirectly via perceptions of financial performance, highlighting its pivotal role in fostering customer contributions to the bank. Assuming that perception reflects reality, banks that fulfill their societal responsibilities are expected to achieve greater organizational success. Naturally, CSR activities entail costs for banks. However, such initiatives may strengthen customers’ positive feelings while tempering negative ones, thereby encouraging more transactions with the bank. If the long-term benefits of these activities outweigh their costs, particularly in the medium and long term, CSR may contribute to an improved financial position for the bank, enhancing its sustainability. For banks to attain sustainability, it is essential to pursue not only financial goals but also non-financial ones, namely environmental and social objectives. Accordingly, banks should adopt a win–win perspective in decision-making processes, considering the interests of all stakeholders, including customers, shareholders, employees, and society at large. Employing social workers in the units of banks that carry out corporate responsibility programs and in the social responsibility activities developed within this scope will contribute to the implementation of services with a community-based, holistic, and needs-focused approach. This broader approach ensures that the benefits of corporate decisions extend beyond organizational boundaries, fostering social trust and long-term resilience. In this regard, value maximization should be prioritized over profit maximization as the core financial aim. At this point, banks are encouraged to implement proactive rather than reactive CSR strategies, that is, to engage in socially responsible practices with sensitivity, volunteerism, and a pioneering spirit. The prerequisite for successful CSR implementation is a top management team with strategic awareness, capable of setting the right direction. Since decisions made at the executive level influence all organizational tiers, top management is both the initiator and primary driver of CSR efforts. That said, every employee has a role in realizing CSR activities. Therefore, top-level corporate decisions concerning CSR must be harmonized with operational decisions at lower levels. Operational decisions should serve and support executive strategies that promote proactive CSR practices.

6.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study has certain limitations. First, the scale items used within the scope of the research do not exhibit normal distribution characteristics. This constitutes one of the methodological limitations of the study. However, based on the skewness and kurtosis values of the variables, the data were considered to be normally distributed, and thus the application of parametric tests was deemed appropriate. Second, while the cross-sectional nature of this study inherently raises the potential for common method bias, both Harman’s single-factor test and the common latent factor analysis demonstrated that this was not a serious concern; nonetheless, replicating the findings through longitudinal or multi-wave designs in future research would provide stronger support for causal inferences. Another limitation of the study is that, due to time and cost constraints, data were collected solely from bank customers in Ankara, albeit using a dataset that was statistically shown to represent the intended population. Nevertheless, in future studies, it would be beneficial to apply the same model to bank customers throughout Turkey and to evaluate the results via regional comparisons. Additionally, the research model used in this study could also be tested in countries in the Middle East, the West, and the Far East that possess different cultural characteristics from Turkey, allowing for comparative results. In further research, personal characteristics of customers (such as personality traits and demographic variables) may be included in the existing model as second-order independent variables, while outcome variables such as customer satisfaction, loyalty, or citizenship behavior may be added. In this way, it will be possible to establish more comprehensive models that examine moderating and mediating relationships.

7. Conclusions

This study underscores the strategic importance of CSR for banking customers’ perceptions of financial performance and their emotional responses. It shows that as customers perceive their bank’s CSR practices to be stronger, they experience heightened positive emotions and diminished negative emotions. SEM and the Sobel test confirm that perceived financial performance partially mediates these relationships.

The findings present a robust conceptual framework illustrating how CSR activities can drive organizational success by integrating cognitive (perceived financial performance) and affective (emotional responses) processes. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that bank managers who simultaneously manage financial performance perception and customer emotions in their CSR strategies can cultivate a more holistic perspective on organizational success. It also contributes to the academic literature by offering an original model that jointly examines CSR, perceived financial performance, and customer emotions.

Given that achieving business sustainability today requires balancing profitability with social value, we recommend that future research test the proposed conceptual framework in sectors beyond banking—such as food retailing, telecommunications, automotive, insurance, and manufacturing. Doing so would both assess the model’s generalizability and validate the mechanisms by which CSR contributes to organizational success in a broader context, thereby offering valuable insights for researchers and practitioners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., A.T.-K., A.A., and S.A.; methodology, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., A.T.-K., A.A., and S.A.; formal analysis, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., and A.T.-K.; investigation, Z.U.Ö.; resources, Z.U.Ö.; data curation, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., and A.T.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., A.T.-K., A.A., and S.A.; writing—review and editing, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., A.T.-K., A.A., and S.A.; visualization, Z.U.Ö., Ş.K., and A.T.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University (Approval No: 295799; Approval Date: 25 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all survey participants, whose responses provided essential data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Figure A1.

Summary of hypothesis test results. Notes: *** p < 0.001; β = standardized regression coefficient. Abbreviations: CSR: corporate social responsibility; FP: financial performance; PEs: positive emotions; NEs: negative emotions.

Figure A1.

Summary of hypothesis test results. Notes: *** p < 0.001; β = standardized regression coefficient. Abbreviations: CSR: corporate social responsibility; FP: financial performance; PEs: positive emotions; NEs: negative emotions.

References

- Akbaş Tuna, A.; Özkara, Z.U.; Taş, A. A study on adaptation of the stakeholder-based corporate social responsibility scale to Turkish. Ank. Haci Bayram Veli Univ. J. Fac. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2019, 21, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chu, Y.C.; Lai, F. Mobile time banking on blockchain system development for community elderly care. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 13223–13235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Düzgün, E.; Meydan Uygur, S. How does corporate social responsibility create customer loyalty? The role of corporate image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, V. Women and corporate social responsibility in banking sector. JIMS8M J. Indian Manag. Strategy 2015, 20, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, G.; Rostami, J.; Turnbull, J.P. Corporate Social Responsibility: Turning Words into Action (Report 255-99); Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, C.K. Socially responsible human resource practices to improve the employability of people with disabilities. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkara, Z.U.; Taş, A.; Aydıntan, B. The effect of perceived corporate social responsibility on altruistic behavior: The mediating role of positive affect. Gazi J. Econ. Bus. 2022, 8, 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puci, J.; Guxholli, S. Business internal auditing—An effective approach in developing sustainable management systems. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Gupta, P. Corporate social responsibility and social development: New vistas of social work practice in India. J. Soc. Work Educ. Pract. 2021, 6, 10–19. Available online: https://jswep.in/index.php/jswep/article/view/127 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Van Hierden, Y.T.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. A citizen-centred approach to CSR in banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 638–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Huang, Y.; Chan, H.-Y.; Yang, C.-H. The impact of corporate social responsibility practices on customer value co-creation and perception in the digital context: A case study of Taiwan bank industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Kumar, V.; Shrivastava, A.K. Corporate social responsibility and customer-citizenship behaviors: The role of customer-company identification. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Rodriguez del Bosque, I. An integrative framework to understand how CSR affects customer loyalty through identification, emotions and satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siueia, T.T.; Wang, J.; Deladem, T.G. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A comparative study in the Sub-Saharan Africa banking sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; van der Veen, R.; Chen, X. Corporate social responsibility, corporate reputation, customer emotions and behavioral intentions: A structural equation modeling analysis. J. China Tour. Res. 2014, 10, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Gonzalez, S.; Vilela, B.B. The influence of emotions on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and consumer loyalty. ESIC Market. Econ. Bus. J. 2016, 47, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Wang, G.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M. Effects of hotels’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives on green consumer behavior: Investigating the roles of consumer engagement, positive emotions, and altruistic values. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Hsu, M.; Chen, X. How does perceived corporate social responsibility contribute to green consumer behavior of Chinese tourists: A hotel context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3157–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, A.; Özkara, Z.U. Relationship between corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: The mediating effect of positive affect. In Sustainability: A Phenomenon Intersecting Different Disciplines; Aydıntan, B., Özkara, Z.U., Eds.; Gazi Kitabevi: Ankara, Turkey, 2023; pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Arian, A.; Sands, J.; Tooley, S. Industry and stakeholder impacts on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial performance: Consumer vs. industrial sectors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, M.; Dumitriu, S.; Georgescu, I.; Berceanu, D.; Simion, D.; Varzaru, A.A.; Bocean, C.G. A perceptual approach to the impact of CSR on organizational financial performance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiorgos, T. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: An empirical analysis on Greek companies. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2010, 13, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Deng, X.; Chang, C.-H. Examining the interactive effect of advertising investment and corporate social responsibility on financial performance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Esfahbodi, A.; Zhang, Y. The impact of corporate social responsibility implementation on enterprises’ financial performance—Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başgöze, P.; Özkan Tektaş, Ö. The effects of negative emotions and corporate reputation on alternative voice complaint behavior of bank customers. J. Mark. Mark. Res. 2021, 14, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lennon, S.J. Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers’ emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention: Based on the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 7, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. The impacts of perceived risk and negative emotions on the service recovery effect for online travel agencies: The moderating role of corporate reputation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 685351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq-Machado, L.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Esquerre-Botton, S.; Almanza-Cruz, C.; de las Mercedes Anderson-Seminario, M.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Yanez, J.A. Effect of corporate social responsibility on consumer satisfaction and consumer loyalty of private banking companies in Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintamür, İ.G.; Yüksel, C.A. Measuring customer based corporate reputation in banking industry: Developing and validating an alternative scale. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 1414–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, Z.; Razzaq, A.; Yousaf, S.; Akram, U.; Hong, Z. The impact of customer equity drivers on loyalty intentions among Chinese banking customers: The moderating role of emotions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 980–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall Publishers: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Amelio, S.; Mauri, M. Sustainable strategies and value creation in the food and beverage sector: The case of large listed European companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]