Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Literature Review

2.1. The Evolution of Emotion in Organizational Theory

2.2. Affective Events Theory (AET)

2.3. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

2.4. Organizational Emotional Capability Theory (OEC)

2.5. Emotion Regulation Theory (ERT)

2.6. Emotional Contagion Theory (ECT)

2.7. Resource-Based View and Emotional Resources

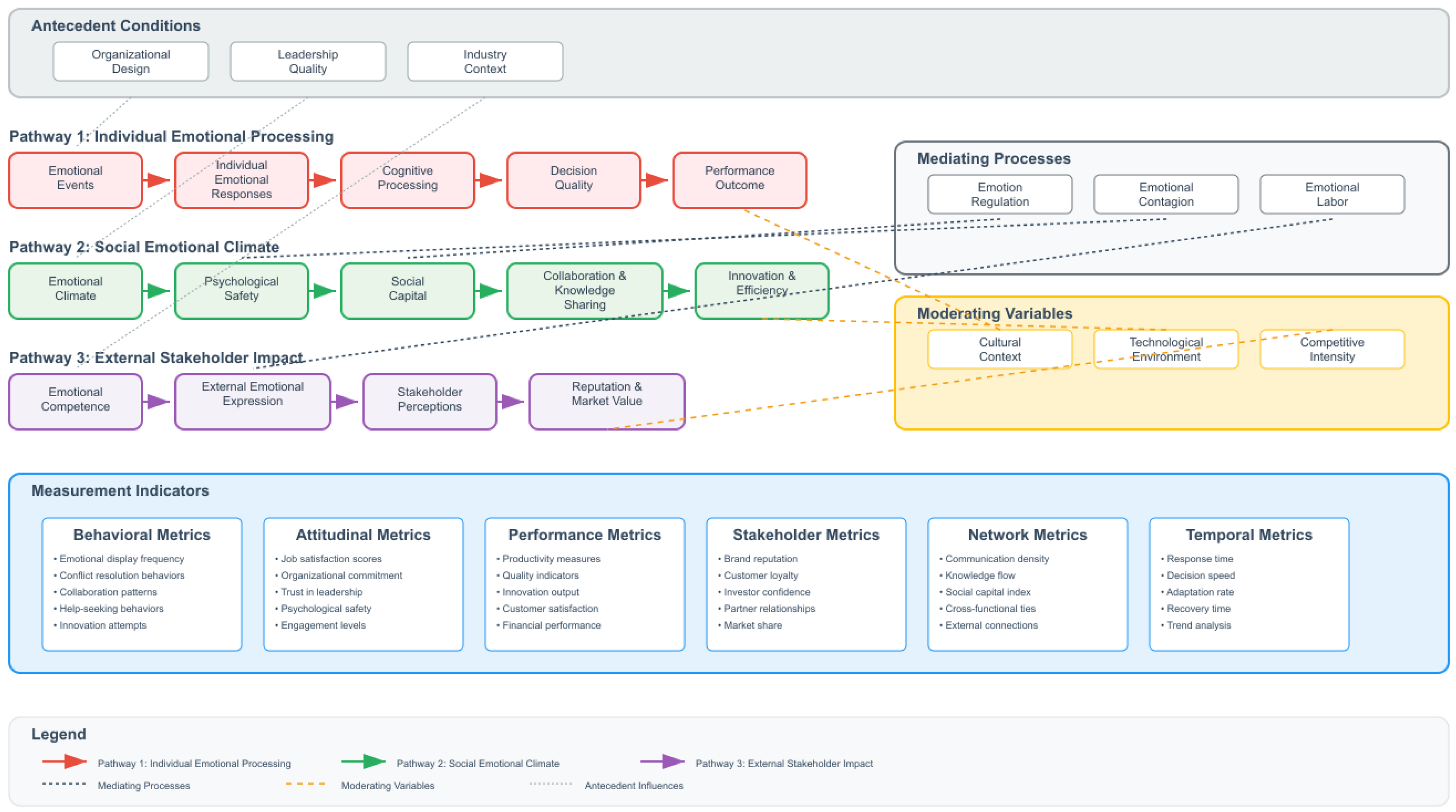

3. Organizational Emotional Materiality Framework

3.1. Core Constructs and Definitions

3.2. The Three Pathways Model

3.3. Theoretical Propositions

4. Boundary Conditions and Contingency Factors

4.1. Industry Context and Competitive Dynamics

4.2. Cultural Context and National Variations

4.3. Technology and Automation Effects

4.4. Temporal Dynamics and Life Cycle Effects

5. Measurement and Methodological Considerations

5.1. Construct Measurement Challenges and Solutions

5.2. Multi-Level Analytical Approaches

5.3. Ethical Implications and Critical Perspectives

5.4. Practical Implementation Guidelines

5.5. Organizational Design Implications

6. Limitations, Future Research and Empirical Validation

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Priority Research Questions and Methodological Approaches

6.3. Cross-Cultural and International Validation

6.4. Methodological Innovation and Technology Integration

7. Conclusions and Theoretical Contribution

References

- Akgün, A. E. , Keskin, H., Byrnes, J. C., & Imamoglu, S. Z. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of organizational emotional capability in new product development projects. Journal of Product Innovation Management 26(5), 544–560.

- Ashkanasy, N. M. , & Dorris, A. D. (2017). Emotions in organizations: Theory and research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 67–90.

- Amabile, T. M. , Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal 39(5), 1154–1184. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 273–285. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120. [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644–675. [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S. G. , & Knight, A. P. (2015). Group affect. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2, 21–46.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

- Cropanzano, R. , & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900. [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes' error: Emotion, reason and the human brain, Putnam.

- Dirks, K. T. , & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 611–628. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation and growth. Wiley.

- Eisenberger, R. , Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 71(3), 500–507.

- Elfenbein, H. A. (2007). Emotion in organizations: A review and theoretical integration. Academy of Management Annals, 1, 315–386.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2010). Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 8: Conceptual framework for financial reporting. FASB.

- Fineman, S. (2000). Emotion in organizations, 2nd ed. Sage Publications.

- Fisher, C. D. , & To, M. L. (2012). Using experience sampling methodology in organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 33(7), 865–877. [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J. P. , & George, J. M. (2001). Affective influences on judgments and behavior in organizations: An information processing perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 3–34. [CrossRef]

- Gallup. (2020). State of the global workplace, Gallup Press.

- George, J. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 53, 1027–1055.

- Glomb, T. M. , & Tews, M. J. (2004). Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ, Bantam Books.

- Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 95–110.

- Gross, J. J. , & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. , Lavie, D., & Madhavan, R. (2012). How do networks matter? The performance effects of interorganizational networks. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 207–224. [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E. , Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional contagion, Cambridge University Press.

- He, H. , Zhu, W., & Zheng, X. (2017). Procedural justice and employee engagement: Roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 681–695. [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T. , Groth, M., Paul, M., & Gremler, D.D. (2006). Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. Journal of Marketing, 70, 58–73.

- Heskett, J. L. , Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, W. E., & Schlesinger, L. A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, 72, 164–174.

- Huang, M. H. , & Rust, R. T. (2018). Artificial intelligence in service. Journal of Service Research 21(2), 155–172.

- Humphrey, R. H. , Burch, G. F., & Adams, L. L. (2016). The benefits of merging leadership research and emotions research. Frontiers in Psychology 7, 1022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huy, Q. N. (1999). Emotional capability, emotional intelligence and radical change. Academy of Management Review, 24, 325–345.

- Isen, A. M. (2001). An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: Theoretical issues with practical implications. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11, 75–85.

- Kitayama, S. , & Park, J. (2007). Cultural shaping of self, emotion and well-being: How does it work? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 202–222.

- Liu, P. , Yang, L., Chen, S., & Wang, Y. (2023). Emotional labor (KELS®11): Scale development and validation for workplace emotional assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 5691.

- Madrid, H. P. , Totterdell, P., Niven, K., & Barros, E. (2020). The emotion regulation roots of job satisfaction. Applied Psychology 69(4), 1208–1233.

- Maul, A. (2012). The validity of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) as a measure of emotional intelligence. Emotion Review, 4, 394–402. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, E. (1933). The human problems of an industrial civilization, Macmillan.

- Mayer, J. D. , Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 507–536. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 24–59. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, P. J. , Hill, A., Kaya, M., & Martin, B. (2019). The measurement of emotional intelligence: A critical review of the literature and recommendations for researchers and practitioners. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1116. [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K. , Knight, C., & Keller, A. (2020). Remote managers are having trust issues. Harvard Business Review 98(4), 96–103.

- Peng, C. , Li, N., & He, J. (2022). Organizational emotional capability and innovation: A multilevel perspective. Journal of Business Research, 142, 123–134.

- Petitta, L. , Jiang, L., & Mazzetti, G. (2021). The impact of emotional contagion on workplace safety: A multilevel study. Safety Science, 136, 105160.

- Rhoades, L. , & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

- Roemmich, K. , Baek, Y., Yildirim, I., & Cakmak, M. (2023). Emotion AI at work: Implications for workplace surveillance and emotional labor. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–18.

- Schwarz, N. , & Clore, G. L. (2003). Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 296–303.

- Seo, M. G. , & Barrett, L. F. (2007). Being emotional during decision making – Good or bad? An empirical investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 923–940. [CrossRef]

- Shiller, R. J. (2015). Irrational exuberance, 3rd ed. Princeton University Press.

- Simon, H. A. (1947). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organization, Macmillan.

- Torrence, B. S. , Connelly, S., Ruark, G. A., & Hickman, J. S. (2019). Emotion regulation tendencies and leadership performance: An examination of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The Leadership Quarterly, 30, 411–426.

- Vuori, T. O. , & Huy, Q. N. (2016). Distributed attention and shared emotions in the innovation process: How Nokia lost the smartphone battle. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61, 9–51.

- Vuori, T. O. , & Huy, Q. N. (2022). Emotions and decision-making in boardrooms: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 853694.

- Wang, S. , & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20, 115–131. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H. M. , & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74.

- Yurtsever, G. , & De Rivera, J. (2010). Measuring the emotional climate of an organization. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 110, 501–516.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).