Submitted:

29 November 2023

Posted:

30 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Is there a presence of relational energy within the interpersonal communication between employees of a unit or organization?

- Are there substantial benefits from relational energy that deems it of strategic importance for organization’s management to consider?

- Are there means available for enhancing relational energy and its associated benefits in organizational settings?

2. Literature review and research hypotheses

2.1. Relational energy

2.2. Relational energy and psychological capital

2.3. Relational energy and humor

2.4. Relational energy as a source for employee and organizational wellbeing and performance

3. Research method

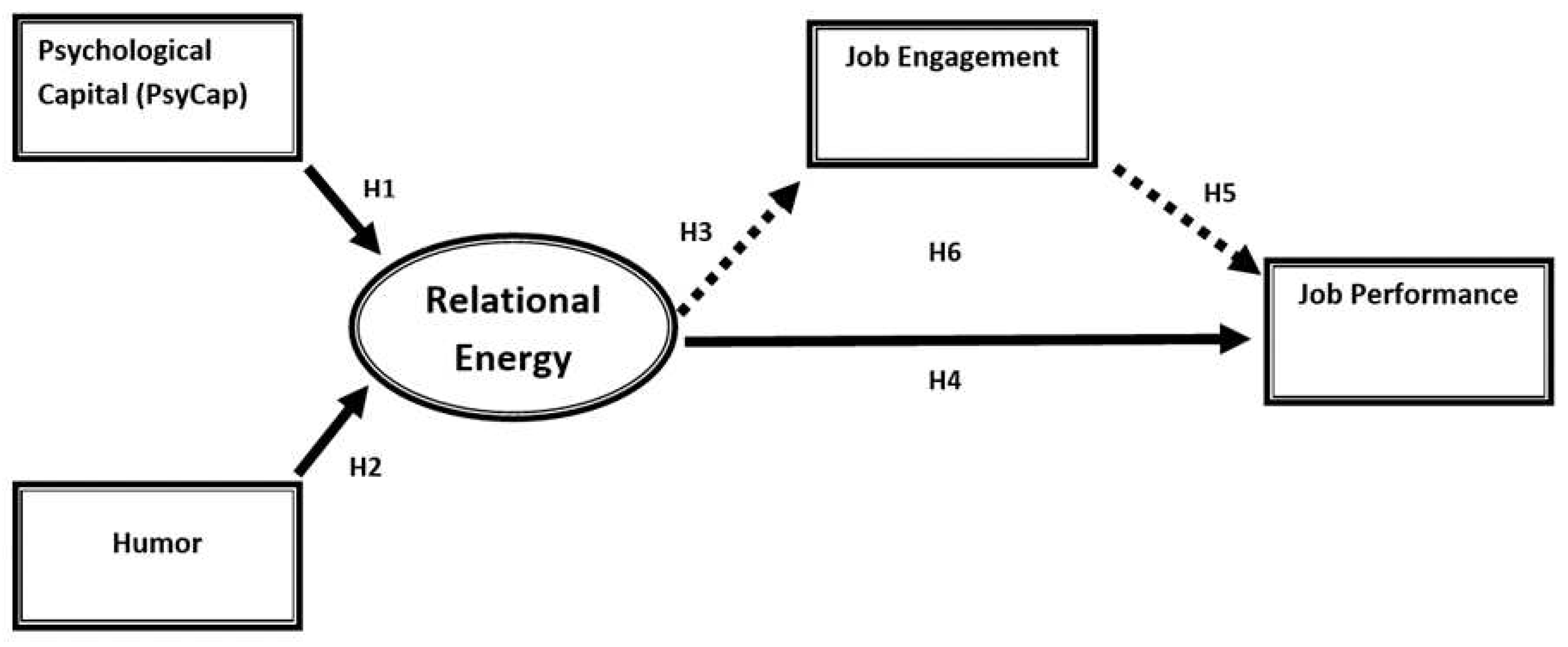

3.1. Research model

3.2. Research sample and measurement instruments

4. Results

4.1. Analytical approach

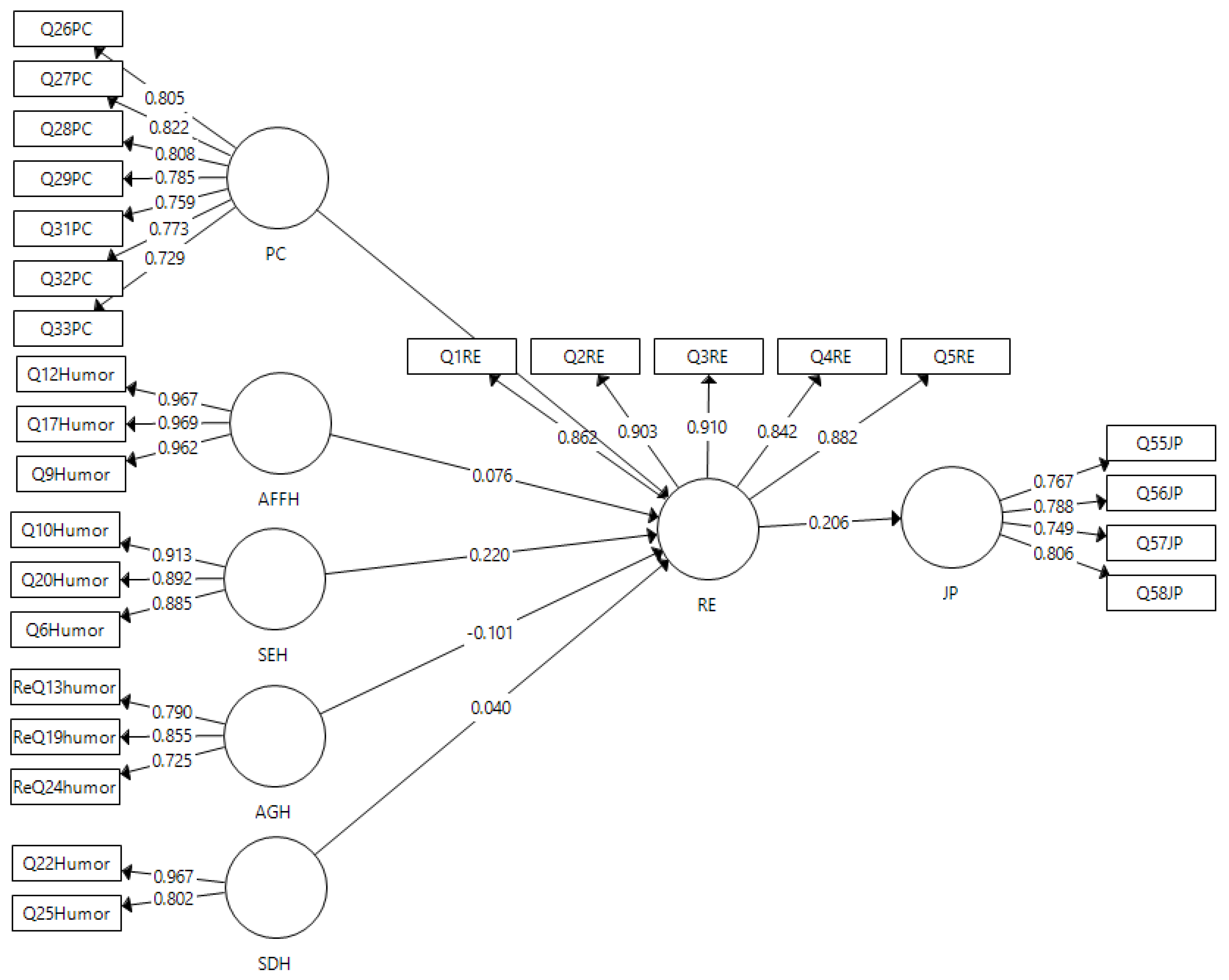

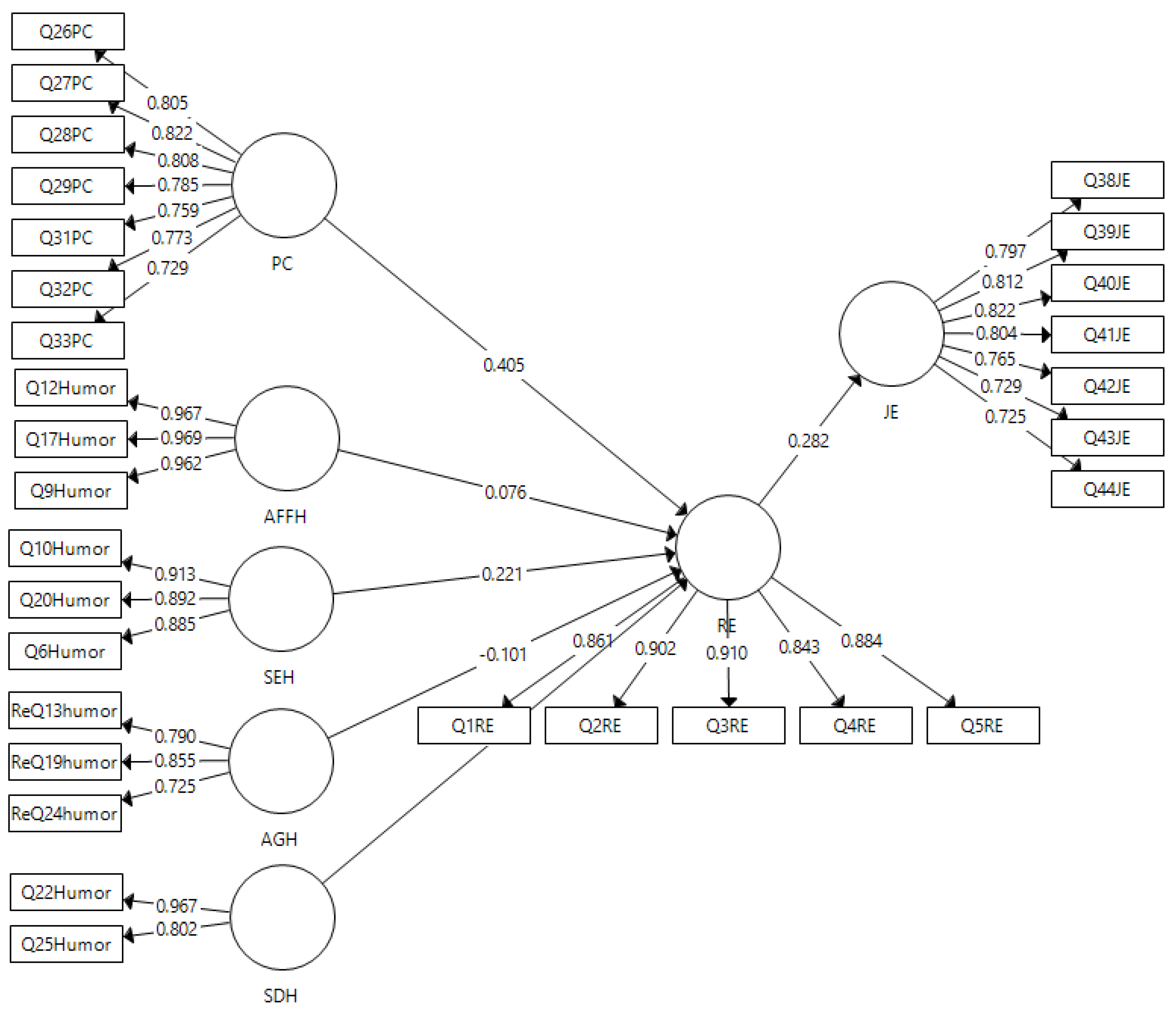

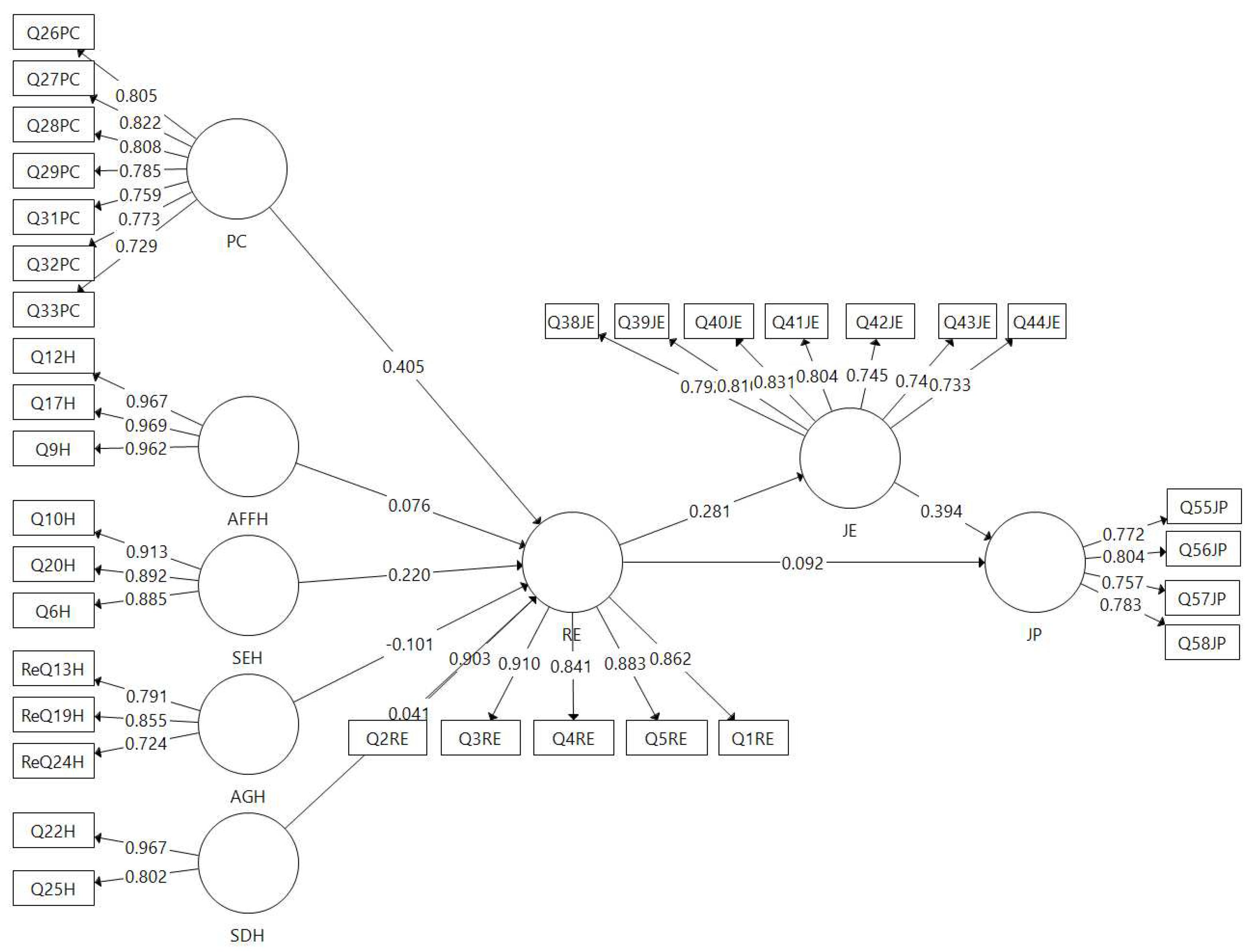

4.2. Descriptive statistics, reliability, validity, model fit, and hypotheses testing

| PC | AFH | SEH | AGH | SDH | RE | JE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FH | 0.319 | ||||||

| SEH | 0.421 | 0.497 | |||||

| AGH | 0.539 | 0.322 | 0.485 | ||||

| SDH | 0.037 | 0.211 | 0.141 | 0.150 | |||

| RE | 0.608 | 0.351 | 0.500 | 0.470 | 0.096 | ||

| JE | 0.330 | 0.125 | 0.178 | 0.253 | 0.079 | 0.308 | |

| JP | 0.300 | 0.289 | 0.229 | 0.126 | 0.064 | 0.233 | 0.496 |

| Hypothesis | Confirmed/rejected |

|---|---|

| 1: There is significant impact of PsyCap on relational energy. | Confirmed |

| 2: There is significant impact of humor on relational energy. | Partially confirmed by aggressive and self-enhancing humor |

| 3: There is significant impact of relational energy on job engagement. | Confirmed |

| 4: There is significant impact of relational energy on job performance. | Confirmed |

| 5: There is significant impact of job engagement on job performance. | Confirmed |

| 6: There is a significant mediating role of job engagement in the impact of relational energy on job performance. | Confirmed |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Contributions and implications

- By testing two antecedents, humor and PsyCap, the study targets relational energy’s further development in organizational context. These two constructs facilitate management’s understanding on how to create, keep, and nurture relational energy within their teams, units, or organization so as to achieve its associated benefits discussed above, particularly, so as to serve in augmentation of organizational outcomes such as job engagement and job performance by the proposed integrated model covering all these 5 variables.

- The advantages of these new grasps not necessarily have to be applied only in an organized way. People individually can experience enhanced relational energy by intensifying, on every possible occasion, interactions with those that energize and show signs of positive humor and/or PsyCap as well as by minimalizing the opposite. Furthermore, they can choose to grow their healthy relationships at work by increasing their own relational energy through investments in their PsyCap and positive humor levels.

- This research raises awareness about greater effectiveness and efficiency of organization’s investment (e.g. training, coaching etc.) in increasing positive humor and/or PsyCap. Besides their associated individual and organizational outcomes, due to advancement of employees’ PsyCap and/or humor levels, those investments will probably also lead to greater relational energy among teams and units; thus, further benefits from the same investment. Relatedly, organizations can invest in training employees on how to intensify relational energy, including the two antecedents utilized in this work.

- The proposed model appears important in coping with COVID-19 setbacks within organizations. Considering the emerging findings that all these three variables improve COVID-19 related organizational challenges, this particular combination might add up to those results. Furthermore, these insights show the advantages of individual or combined interventions in relational energy, humor, and PsyCap that management can take in order to deal not only with recent corona pandemic aftermaths, but also with prospective later epidemics, pandemics, or other health crises.

- The paper shifts concentration from leaders being chief generators of relational energy to each employee potentially embracing that function. The current research pioneers the investigation of relational energy in coworker interpersonal communication rather than in a leader-member one.

- The analysis also extends existing focus of relational energy’s direct, mediating, or moderating role on certain beneficial outcomes to how relational energy can otherwise be further and differently boosted, above and beyond leadership style and leader behaviors and actions, so that its impact of those outcomes multiplies. Nonetheless, the emerging and yet understudied world of relational energy (and human energy in general) at work is recognized and the importance of exploring new descendants is highly regarded; the current study sheds light on the urge for simultaneous supplementary research on its antecedents too.

- Relational energy is measured from the receiver’s perspective, as per Owens’ et al. [2] instrument, what is considered better representing it as opposed to energy sender’s angle for this approach explains more soundly how the energizing process operates.

- To the authors’ knowledge, no other works before have determined this exact correlation among all the variables of the current model.

- Contribution is made in intensifying the connection between POS and POB since a combination of variables from both streams are investigated.

- To the authors’ knowledge, it is the first time this field is researched in Kosova or Western Balkans region.

- Taking into account all the above, organization and management literature is progressed by the current work, specifically related to human and organizational energy, positivity, humor, interpersonal communication, social and psychological capital, job engagement, individual and organizational performance, employee wellbeing, healthy work relationships, and motivation.

6.2. Limitations and recommendations fur future research

- The focus on private service sector only, although including numerous industries within, might miss other important features of interpersonal communication between coworkers in other sectors. Hence, the study may be limited in its generalizability. Other areas, for example public sector or manufacturing, could be potential for future research that should generalize beyond this work.

- The concentration on the Prishtina district might be too small for concluding representatively for other cultures and geographies. Irrespective of McDaniel’s [10] findings of no significant cultural differences related to relational energy and that it can be seen as a universal phenomenon, Weng et al. [61] find a stronger crossover of work passion to followers from Anglo cultures than to those from Confucian culture, a relationship that is mediated by relational energy. Moreover, there are other variables that can be more culturally sensitive, such as humor. Therefore, future research that might use the current study’s model can examine it in samples representing other cultures or parts of the world.

- In order to achieve model fit, some items needed to be removed from the original scales, especially in the humor case which had several reverse items. One explanation could be that the reading culture in the sample region is as such that people prefer short and simple reading. Future research should take this into consideration when designing the questionnaire if they are to carry out research with the same model in cultures with such or similar reading habits. Alternatively, higher-qualified respondents, such as academicians for example, can be targeted in order to ensure greater understanding of the questions. Otherwise, in order to shorten the questionnaire and increase the probability of greater focus from the respondents in similar cases, the first and the second half of the model could be examined in separate researches.

- There might be a likelihood for endogeneity in the sense that, for instance, receivers of relational energy can, in turn, experience growth in their positive humor and PsyCap levels too. As such, future research can replicate the current model by conducting more meticulous methodological design.

- Relational energy can be transmitted from different sources, i.e. coworkers, supervisors, followers, family, friends and so on. This study’s focus was on coworkers, while many earlier studies investigate merely the leader-follower dyadic interaction. It is advisable for further works to enlarge the relational energy transmission base by a combination of both coworkers and leaders as suppliers of relational energy.

- Taking into account this is a cross-sectional research, future research shall expand to longitudinal data in order to advance the understanding in abundance of interactions in a nomological network [67].

- None of the many control variables resulted significantly correlated with the latent ones. The reason behind might be that the demographics included do not define the “pepping up” between two people or that other determining control variables are unseen. This could be replicated in the future through reformulation and/or reorganization of some or all current research’s control variables, inclusion of new ones, or both—reformulation/reorganization and addition.

- Albeit there is evidence that the self-assessment scales of job performance and job engagement are not subjective when respondents are assured on no identity disclosure [105]—as it is the case in the current study—and that there is no significant difference between self-assessment and other-assessment of performance [17]; still, they might fail to capture some objectivity as compared to performance appraisals by supervisor/organization. Prospect studies could increase this accuracy by employing actual performance data such as at Owens et al. [2].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 |

References

- Dutton, J.E. Energize Your Workplace: How to Create and Sustain High-Quality Connections at Work; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, 2003;

- Owens, B.P.; Baker, W.E.; Sumpter, D.M.; Cameron, K. Relational Energy at Work: Implications for Job Engagement and Job Performance. J Appl Psychol 2016, 101, 35–49. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S. Practicing Positive Leadership: Tools and Techniques That Create Extraordinary Results; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc: San Fransisco, 2013;

- Braha, M. Effect of Psychological Capital and Humor on Relational Energy and Its Impact on Job Engagement and Job Performance (682342).. s.l.:[Doctoral Dissertation, Istanbul Commerce University: Istanbul, 2021.

- Braha, M. Fueling Relational Energy? Proposing PsyCap and Humor as Potential Antescendents. J. int. trade logist. law. 2021, 7, 44–52.

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction. Am Psychol 2000, 41, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S. Positively Energizing Leadership: Virtuous Actions and Relationships That Create High Performance; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc, 2021;

- Baker, W.; Cross, R.; Wooten, M. Positive Organizational Network Analysis and Energizing Relationships. In Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline.; 2003; pp. 328–342.

- Cross, R.; Baker, W.; Parker, A. What Creates Energy in Organizations? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 51–56.

- McDaniel, D.M. Energy at Work: A Multinational, Crosssituational Investigation of Relational Energy, University of California, Irvine, 2011.

- Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F. Experimentally Analyzing the Impact of Leader Positivity on Follower Positivity and Performance. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 282–294. [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 4, 339–366. [CrossRef]

- Bockorny, K.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Entrepreneurs’ courage, psychological capital, and life satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 789. [CrossRef]

- Elbers., A.; Kolominski, S.; Aledo, P.S.B. Coping with Dark Leadership: Examination of the Impact of Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Dark Leaders and Employees’ Basic Need Satisfaction in the Workplace. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 96. [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, D.; Siswanto, E.; Purwanto, A.; Fahmi, K. Authentic Leadership and Innovation: What Is the Role of Psychological Capital? Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2020, 1, 1–21.

- Yu, X.; Li, D.; Tsai, C.H.; Wang, C. The Role of Psychological Capital in Employee Creativity. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 1362–0436. [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the Impact of Positive Psychological Capital on Employee Attitudes, Behaviors, and Performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 127–152. [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.L.; Cheung, F.; Lui, S. Linking Positive Emotions to Work Well-Being and Turnover Intention among Hong Kong Police Officers: The Role of Psychological Capital. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 367–380. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D.; Joshi, G. Impact of Psychological Capital and Life Satisfaction on Organizational Resilience during COVID-19: Indian Tourism Insights. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Alat, P.; Das, S.S.; Arora, A.; Jha, A.K. Mental Health during COVID-19 Lockdown in India: Role of Psychological Capital and Internal Locus of Control. Curr Psychol 2023, 42, 1923–1935. [CrossRef]

- Daraba, D.; Wirawan, H.; Salam, R.; Faisal, M. Working from Home during the Corona Pandemic: Investigating the Role of Authentic Leadership, Psychological Capital, and Gender on Employee Performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1885573. [CrossRef]

- Harahsheh, A.A.; Houssien, A.M.A.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Mohammad, A. The Effect of Transformational Leadership on Achieving Effective Decisions in the Presence of Psychological Capital as an Intermediate Variable in Private Jordanian Universities in Light of the Corona Pandemic. In The Effect of Coronavirus Disease (covid-19) on Business Intelligence. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Alshurideh, M., Hassanien, A.E., Masa’deh, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Maykrantz, S.A.; Langlinais, L.A.; Houghton, J.D.; Neck, C.P. Self-Leadership and Psychological Capital as Key Cognitive Resources for Shaping Health-Protective Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Turliuc, M.N.; Candel, O.S. The Relationship between Psychological Capital and Mental Health during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Mediation Model. J. Health Psychol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zyberaj, J.; Bakaç, C. Insecure yet Resourceful: Psychological Capital Mitigates the Negative Effects of Employees’ Career Insecurity on Their Career Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 473. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S. Positive Leadership: Strategies for Extraordinary Performance; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc: San Fransisco, 2012;

- Story, J.S.P.; Youseff, C.M.; Luthans, F.; Barbuto, J.E.; Bovaird, J. Contagion Effect of Global Leaders’ Positive Psychological Capital on Followers: Does Distance and Quality of Relationship Matter? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2534–2553. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.A.; Kuiper, N.A.; Olinger, L.J.; Dance, K.A. Humor, Coping with Stress and Psychological Well-Being. Humor 1993, 6, 89–104.

- Martin, R.A.; Lefcourt, H.M. Sense of Humor as a Moderator of the Relation between Stressors and Moods. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983, 45, 1313–1334.

- Gostik, A.; Christopher, S. The Levity Effect: Why It Pays to Lighten Up; John Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, 2008;

- Romero, E.; Pescosolido, A. Humor and Group Effectiveness. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 395–418. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.; Marra, M. Humor and Leadership Style. Humor 2006, 19, 119–138. [CrossRef]

- Johari, A.B.; Wahat, N.W.A.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z. Innovative Work Behavior among Teachers in Malaysia: The Effects of Teamwork, Principal Support, and Humor. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2021, 17. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, O.H. Humorous Communication: Finding a Place for Humor in Communication Research. Commun Theory 2002, 12, 423–445. [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.; Glew, D.J.; Viswesvaran, C. A Meta-Analysis of Positive Humor in the Workplace. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 155–190. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Wang, L. Examining the Energizing Effects of Humor: The Influence of Humor on Persistence Behavior. J Bus Psychol 2014, 30, 759–772. [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.; Guidice, R.; Andrews, M.; Oechslin, R. The effects of supervisor humour on employee attitudes. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 697–710. [CrossRef]

- Guenter, H. How Adaptive and Maladaptive Humor Influence Well-Being at Work: A Diary Study. Humor 2013, 26, 573–594. [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayana, K. The Power of Humor at the Workplace; India: SAGE Publications, 2007;

- Andrew, R.O.; Thomas, E.F. Humor Styles Predict Emotional and Behavioral Responses to COVID-19. Humor 2021, 34, 177–199. [CrossRef]

- Canestrari, C. Coronavirus Disease Stress among Italian Healthcare Workers: The Role of Coping Humor. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3962. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ye, L.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Leader Humor on Employee Creativity during the COVID-19 Period: The Roles of Perceived Workload and Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 303. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.D.; Sosik, J.J. The Laughter Advantage: Cultivating High-Quality Connections and Workplace Outcomes through Humor. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2012; pp. 474–489. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.D. Elucidating the Bonds of Workplace Humor: A Relational Process Model. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1087–1115. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, W.J.; Smeltzer, L.R.; Leap, T.L. Humor and Work: Applications of Joking Behavior to Management. J Manage 1990, 16, 255–278. [CrossRef]

- Simione, L.; Gnagnarella, C. Humor Coping Reduces the Positive Relationship between Avoidance Coping Strategies and Perceived Stress: A Moderation Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 179. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.A.; Puhlik-Doris, P.; Larsen, G.; Gray, J.; Weir, K. Individual Differences in Uses of Humor and Their Relation to Psychological Well-Being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. J Res Pers 2003, 37, 48–75. [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, N.A. Humor styles questionnaire. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer, 2020; pp. 2087–2090.

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Lam, C.F.; Quinn, R.W. Human Energy in Organizations: Implications for POS from Six Interdisciplinary Streams. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2012; pp. 155–167. [CrossRef]

- Bruch, H.; Kunz, J.J. Organisational Energy as the Engine of Success: Managing Energy Effectively with Strategic HR Development. In Strategic human resource development: A journey in eight stages; Meifert, M.T., Ed.; Springer, 2013; pp. 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Lam, C.F.; Spreitzer, G.M. It’s the Little Things That Matter: An Examination of Knowledge Workers’ Energy Management. Acad Manag Perspect 2011, 25, 28–39.

- Seppälä, E.; Cameron, K.S. Proof That Positive Work Cultures Are More Productive. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 12, 44–50.

- Heaphy, E.D.; Dutton, J.E. Positive Social Interactions and the Human Body at Work: Linking Organizations and Physiology. Acad Manage Rev 2008, 33, 137–162. [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, T.; Lobo, M.S. When Competence Is Irrelevant: The Role of Interpersonal Affect in Task-Related Ties. Adm. Sci. Q. 2008, 53, 655–684. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L.; Nesse, R.M.; Vinokur, A.D.; Smith, D.M. Providing Social Support May Be Better than Receiving It: Results from a Prospective Study. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 320–327. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L.; Brown, R.M. Selective Investment Theory: Recasting the Functional Significance of Close Relationships. Psychol. Inq. 2006, 17, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Russo, B.D. Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Acad Manage J 2008, 51, 898–918. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Feeling Energized: A Multilevel Model of Spiritual Leadership, Leader Integrity, Relational Energy, and Job Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Amah, O.E.; Sese, E. Relational energy and employee engagement: Role of employee voice and organisational support. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2018, 53, 475–487.

- Wang, L.; Owens, B.P.; Li, J.; Shi, L. Exploring the Affective Impact, Boundary Conditions, and Antecedents of Leader Humility. Am Psychol Assoc 2018, 103, 1019–1038. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Butt, H.P.; Almeida, S.; Ahmed, B.; Obaid, A.; Burhan, M.; Tariq, H. Where Energy Flows, Passion Grows: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model of Work Passion through a Cross-Cultural Lens. Curr Psychol 2020, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Mao, J.; Quan, J.; Qing, T. Workplace Friendship Facilitates Employee Interpersonal Citizenship. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Amah, O.E. Leadership Styles and Relational Energy in High Quality Mentoring Relationship. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2017, 53, 59–71.

- Wang, Z.; Xie, Y. Authentic Leadership and Employees’ Emotional Labour in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 797–814. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Y.; Chu, C.Y.; Lin, J.S.C. Engaging Customers with Employees in Service Encounters: Linking Employee and Customer Service Engagement Behaviors through Relational Energy and Interaction Cohesion. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 31, 1071–1105.

- Liebhart, U.; Faullant, R. Relational Energy as a Booster for High Quality Relationships in Mentoring.; European Academy of Management: Valencia, 2014.

- Boyatzis, R.E.; Rochford, K. Rlational Climate in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Amah, O.E. Employee Engagement and Work-Family Conflict Relationship: The Role of Personal and Organizational Resources. S. Afr. J. Labour Relat. 2016, 40, 118–138.

- Baruah, R.; Reddy, K.J. Implication of Emotional Labor, Cognitive Flexibility, and Relational Energy among Cabin Crew: A Review. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 22, 2–4. [CrossRef]

- Chadee, D.; Ren, S.; Tang, G. Is Digital Technology the Magic Bullet for Performing Work at Home? Lessons Learned for Post COVID-19 Recovery in Hospitality Management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92. [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Wheeler, A.R. The Relative Roles of Engagement and Embeddedness in Predicting Job Performance and Intention to Leave. Work Stress 2008, 22, 242–256. [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Acad Manage J 2010, 53, 617–635. [CrossRef]

- Agjencia e Statistikave të Kosovës Repertori statistikor mbi ndërmarrjet në Kosovë TM4 2016; Agjencia e Statistikave të Kosovës: Prishtina, 2016;

- Agjencia e Statistikave të Kosovës Klasifikimi i veprimtarive ekonomike - NACE Rev.2; Agjencia e Statistikave të Kosovës: Prishtina, 2014;

- United Nations International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities - Rev. 4; United Nations, 2008;

- Eurostat Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community - NACE Rev.2; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2008;

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.; Clapp-Smith, R.; Li, W. More Evidence on the Value of Chinese Workers’ Psychological Capital: A Potentially Unlimited Competitive Resource? Management Department Faculty Publications 2008, 133.

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.; Avolio, B. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Edge; Oxford University Press, 2007;

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educ Psychol Meas 2006, 66, 701–716. [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; van Buuren, S.; van der Beek, A.J.; de Vet, H.C. Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2014, 62, 6–28.

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; de Vet, H.C.; van der Beek, A.J. Construct validity of the individual work performance questionnaire. J Occup Environ Med 2014, 56, 331–337. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.O. The Relationships among Perceived Effectiveness of Network-Building Training Approaches, Extent of Advice Networks, and Perceived Individual Job Performance among Employees in a Semiconductor Manufacturing Company in Korea. Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University, 2010.

- Tsui, A.S.; Pearce, J.L.; Porter, L.W.; Tripoli, A.M. Alternative Approaches to the Employee-Organization Relationship: Does Investment in Employees Pay Off? Acad Manage J 1997, 40, 1089–1121. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; 4th ed.; Gulford Press: New York, 2016;

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1978;

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: A Comparative Evaluation of Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling Methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Tomas, G.; Hult, M.; et al. Common Beliefs and Reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986, 51, 1173–1182.

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121.

- Avey, J.B.; Wernsing, T.S.; Luthans, F. Can Positive Employees Help Positive Organizational Change? Impact of Psychological Capital and Emotions on Relevant Attitudes and Behaviors. J Appl Behav Sci 2008, 44, 48–70. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, F.; Ding, C. Linking Leader Humor to Employee Creativity: The Roles of Relational Energy and Traditionality. J. Manag. Psychol. 2021, 36, 548–561. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Dong, Y.; Kong, Y.; Shaalan, A.; Tourky, M. When and How Does Leader Humor Promote Customer-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Hotel Employees? Tour. Manag. 2023, 96. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, G.; Jiang, P. Linking Leader Humor to Employee Bootlegging: A Resource-Based Perspective. J Bus Psychol 2023, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ju, D.; Yam, K.C.; Liu, S.; Qin, X.; Tian, G. Employee Humor Can Shield Them from Abusive Supervision. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 186, 407–424. [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Zapata, C.L.; Davis, H.B. Positive and Negative Styles of Humor in Communication: Evidence for the Importance of Considering Both Styles. Commun. Q. 2009, 57, 452–468. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.J.; Caetano, A.; Lopes, R.R. Humor Daily Events and Well-Being: The Role of Gelotophobia and Psychological Work Climate. In The Science of Emotional Intelligence; Taukeni, S.G., Ed.; 2021.

- Liao, Y.H.; Luo, S.Y.; Tsai, M.H.; Chen, H.C. An Exploration of the Relationships between Elementary School Teachers’ Humor Styles and Their Emotional Labor. Teach Teach Educ 2020, 87, 102950. [CrossRef]

- Miczo, N.; Welter, R.E. Aggressive and Affiliative Humor: Relationships to Aspects of Intercultural Communication. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2006, 35, 61–77. [CrossRef]

- Miczo, N.; Averbeck, J.M.; Mariani, T. Affiliative and Aggressive Humor, Attachment Dimensions, and Interaction Goals. Commun. Stud. 2009, 60, 443–459. [CrossRef]

- Yaprak, P.; Güçlü, M.; Durhan, T.A. The Happiness, Hardiness, and Humor Styles of Students with a Bachelor’s Degree in Sport Sciences. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 82. [CrossRef]

- Cullen-Lester, K.L.; Leroy, H.; Gerbasi, A.; Nishii, L. Energy’s Role in the Extraversion (Dis) Advantage: How Energy Ties and Task Conflict Help Clarify the Relationship between Extraversion and Proactive Performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 37, 1003–1022. [CrossRef]

- Bozgeyikli, H. Big Five Personality Traits as the Predictor of Teachers’ Organizational Psychological Capital. J. educ. pract. 2017, 8, 125–135.

- Dewal, K.; Kumar, S. He Mediating Role of Psychological Capital in the Relationship between Big Five Personality Traits and Psychological Well-Being: A Study of Indian Entrepreneurs. Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 8, 500–506.

- Tho, N.D.; Phong, N.D.; Quan, T.H.M. Marketers’ Psychological Capital and Performance. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 36–48. [CrossRef]

| Construct | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological Capital | 4.89 | 0.88 |

| Affiliated humor | 5.17 | 1.41 |

| Self-enhancing humor | 4.89 | 1.32 |

| Aggressive humor | 3.12 | 1.46 |

| Self-defeating humor | 3.72 | 1.66 |

| Relational energy | 5.30 | 1.22 |

| Job engagement | 5.02 | 0.84 |

| Job performance | 4.27 | 0.63 |

| n(481) |

| PC | AFH | SEH | AGH | SDH | RE | JE | JP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | Pearson Correlation | 1 | |||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | |||||||||

| AFH | Pearson Correlation | .291** | 1 | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | ||||||||

| SEH | Pearson Correlation | .371** | .458** | 1 | |||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | |||||||

| AGH | Pearson Correlation | -.424** | -.268** | -.380** | 1 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||||||

| SDH | Pearson Correlation | .004 | .179** | .121** | -.001 | 1 | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .931 | .000 | .008 | .974 | |||||

| RE | Pearson Correlation | .551** | .332** | .452** | -.378** | .080 | 1 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .080 | ||||

| JE | Pearson Correlation | .300** | .116* | .157** | -.199** | .063 | .282** | 1 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .011 | .001 | .000 | .167 | .000 | |||

| JP | Pearson Correlation | .249** | .258** | .188** | -.085 | .025 | .194** | .411** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .063 | .592 | .000 | .000 |

| Construct | No. of items | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological Capital | 7 | 0.895 |

| Affiliated humor | 3 | 0.964 |

| Self-enhancing humor | 3 | 0.879 |

| Aggressive humor | 3 | 0.700 |

| Self-defeating humor | 2 | 0.768 |

| Relational energy | 5 | 0.927 |

| Job engagement | 7 | 0.892 |

| Job performance | 4 | 0.785 |

| Construct | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological Capital | 0.917 | 0.614 |

| Affiliated humor | 0.977 | 0.933 |

| Self-enhancing humor | 0.925 | 0.805 |

| Aggressive humor | 0.834 | 0.627 |

| Self-defeating humor | 0.881 | 0.789 |

| Relational energy | 0.945 | 0.775 |

| Job engagement | 0.916 | 0.608 |

| Job performance | 0.861 | 0.607 |

| Effects | Path | Path coefficient | Indirect effect | Total effect | VAF | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | RE→JE | 0.281 | Not applicable | ||||

| JE→JP | 0.394 | Not applicable | |||||

| RE→JP | 0.092 | 0.110 | 0.203 | 54.18% | 4.583 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).