1. Introduction

The concept of leadership cuts across all peoples and has been present since the dawn of civilization. King, emperor, sultan, president, and even boss are terms used to characterize someone who leads others towards creative and intuitive goals (Bolden, 2004). As organizations evolve, the leader has an increasing obligation to adapt to the subordinate and vice versa so that both can achieve goals that provide them with professional and personal harmony.

Leaders can be flexible and welcoming towards their subordinates and adopt transformational or participative leadership (Grill., et al., 2017). However, the great fear of subordinates is when their leadership doesn't bet on their qualities, demeans and abuses them without remorse. This type of leadership is called toxic or toxic leadership. This way of leading is usually associated with the individual's characteristics, which are very difficult to change as they are properties of the individual's personality (Aravena, 2019). Erickson et al. (2015) state that toxic leadership is the set of various toxic actions that lead subordinates to achieve goals that promote the leader's image.

When discussing toxic leadership, we group a set of dimensions that are the source of this darker leadership. Schmidt (2008) developed these dimensions, and he confirms that abusive supervision, authoritarian leadership, narcissism, self-promotion, and unpredictability (Mónico et al., 2019) are the sources that feed toxic leadership and that the behaviors that these leaders show come from one of these five dimensions.

The problems associated with toxic leadership are many: negative attitudes, less job satisfaction, depression (Erickson et al., 2015), and even the actual departure from the organization, which is strongly influenced by the relationships we have with colleagues or managers in the organization (Burt et al., 2009). To reinforce this, Zhang (2016) explains that turnover intentions tend to rise when organizations do not care for their employees, especially in relationships.

Despite this poor relationship, sometimes there is no room for employees to easily walk away from their jobs, whether for accommodation, monetary or emotional reasons. This emotional stability or instability is detected and controlled through the emotional intelligence in each of us. Emotional intelligence is the ability of individuals to perceive emotions and reason and apply them to various extrinsic factors (Mayer et al., 2004). From another perspective, emotional intelligence is identified as the perception of personal emotions and the behaviors and actions of others (Ioannidou and Konstantikaki, 2008). It is also important to note that knowing how to recognize one's own emotions helps to discriminate good from bad (Ioannidou and Konstantikaki, 2008).

Like toxic leadership, emotional intelligence has a model with four dimensions: the perception of one's own emotions, the perception of the emotions of others, the use of emotions, and the regulation of emotions (Rodrigues et al., 2011).

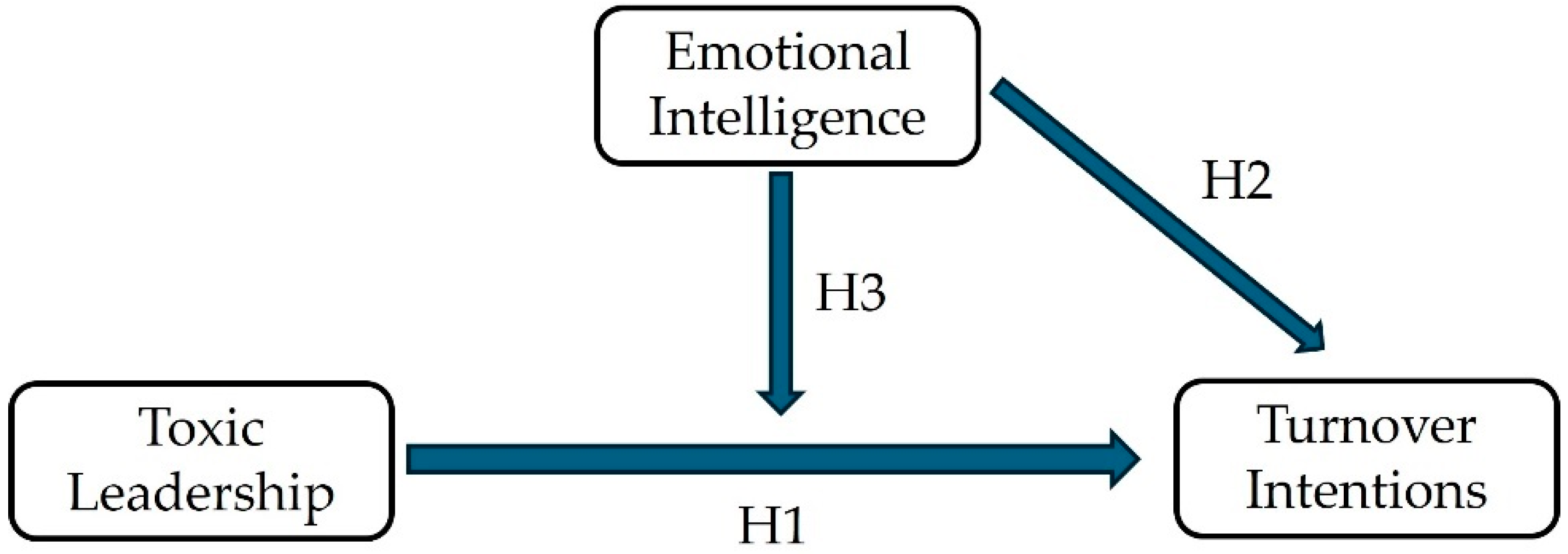

This study aimed to determine the effect of toxic leadership on turnover intentions and whether emotional intelligence moderated this relationship.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Toxic Leadership

From an earlier age, "leadership" was strongly linked to the leader's ability to promote and encourage followers to do the right thing. A strong leader's primary goal is to follow the path to victory on a personal and organizational level. DePree (1998) states that leaders have a duty to assume a certain maturity. This maturity is expressed through responsibility, self-esteem, belonging and equality (DePree, 1998). However, not all leaders promote the well-being and organizational support that subordinates need.

The study by Krasikova et al. (2013) concludes that the dark side of leadership is noticeable in some organizations. They state that toxic leadership can take various forms, such as abusive supervision and "petty tyranny" (Krasikova., et al., 2013, p.1308). In the same vein, Erickson et al. (2015) research identifies that toxic leadership in the US military presupposes a "perfect" triangle between toxic leaders, susceptible subordinates and a welcoming environment. This triangle is, in fact, the reality in many organizations worldwide, particularly in 25% of organizations (Erickson et al., 2015).

Toxic leaders are often frustrated and arrogant, and their main goal is to prevail in terms of their image and sovereignty over others. From this perspective, the studies by Krasikova et al. (2013) characterize the toxic leader as evil. Their behaviors are essential for their superiority and visibility within the organization, even if this affects their subordinates. In the same vein, research by Erickson et al. (2015) concludes that leaders can become toxic when their personal goals (promotions or career advancement) cannot be legitimately recognized.

Also, the studies by Einarsen et al. (2007) state that it is important to remember that leaders can make bad decisions on a day-to-day basis without being considered toxic. A leader is only considered toxic when he or she systematically and repetitively provokes this type of action. Erickson et al. (2015) reinforce the same idea by saying that to be considered a toxic leader, they must be volitional, systematic, and repeated over time.

The behaviors observed over the years have made it possible to see that these actions come from different ways of acting, as Dobbs (2013) explains in his research on leadership. This author determines that toxic leadership is multidimensional and groups together five interconnected areas, referring to Schmidt (2008), author of the conceptual model and later author of the Toxic Leadership Scale (TLS). He focused on finding the characteristics that they can adopt. In this way, Schmidt (2008) considers the five dimensions as: abusive supervision, which presents toxic verbal and non-verbal behaviors (Schmidt, 2008), such as outbursts of anger, aggressive feedback and ridicule of subordinates (Salvador, 2018), worse notions of organizational justice and even greater psychological abuse (Tepper, 2000); authoritarian leadership, which is defined as a behavior of control and obedience on the part of their subordinates (Cheng. et al., 2004), and even greater psychological abuse (Tepper, 2000), and also a restriction on the autonomy and initiative of subordinates (Ferreira, 2021); narcissism, known as thinking and valuing oneself as a form of supremacy (Schmidt, 2008), a bad influence on the work and lives of subordinates (Lubit, 2004) and also a big gap in empathy and recognition of the efforts made by others (Ferreira, 2021); self-promotion, which aims to promote the image of leaders in an excessive way, promoting their interests in order to create a good image at higher levels of the hierarchy (Schmidt, 2008) and also to ward off rivals within the organization (Salvador, 2018); finally, unpredictability, which refers to the leader's unexpected behaviors, mainly toxic or abusive behaviors and unpredictable mood swings (Schmidt, 2008; Salvador, 2018; Mónico et al., 2019).

Schmidt's research (2008) made it possible to see the great impact of toxic leadership on the organization and, above all, on subordinates. In turn, he tried to understand some of the behaviors adopted by the leader in the five dimensions mentioned above.

The behaviors adopted by LD are often absorbed by subordinates who can develop associated problems, whether physical, mental or organizational. A brief survey found that the consequences of this type of leadership include a great lack of trust, a feeling of favoritism and nepotism (Erickson., et al., 2015), bullying (Khan., et al., 2017) and a lack of energy motivation and fatigue (Goleman, 2011; Erickson., et al., 2015). At a more extreme stage, some employees may suffer from physical violence (Schyns and Schilling, 2013) and even end up leaving the organization, as explained by Arshad and Puteh (2015), who determined that frustrated and unhappy employees are more likely to intend to leave than satisfied employees.

2.2. Turnover Intentions

Their stay in the company characterizes an employee's working life until they leave. With the growth and development of the human resources department, there is a need to analyze potential intentions to leave. Mendes (2014) analyzes and describes three names for this phenomenon to better understand these definitions. Firstly, he characterizes involuntary turnover as the departure of an employee by decision of the organization; then voluntary turnover, referring to the departure of an employee by their own decision; and, finally, turnover intentions, described as the employee's turnover intentions through behavior, words or attitudes (Mendes, 2014).

The definition of turnover intentions is the desire or willingness to leave the organization in search of something new (Liu, 2012) or the actual movement of an employee to something outside the organization's boundaries (Rahman, 2013). Carmeli and Weisberg (2006) state that the exit intention process is divided into three phases: 1) thinking about leaving, 2) thinking about looking for a new job, and 3) the actual turnover intention.

The topic resulted in some assumptions, such as: why do employees show their intention to leave? Well, studies show that the motivations can be various, from management and unions (Alam, 2019), the relationship with colleagues (Alam, 2019; Liu, 2012), salary and benefits (Alam, 2019; Lee, 2012), organizational factors such as the work environment (Alam, 2019; Lee, 2012) to organizational commitment (Alam, 2019; Liu, 2012; Rahman, 2013).

Rahman (2013) mentioned that a survey by the Society for Human Resource Management and Aon Consulting concluded that poor management is the third most common reason for employees to consider leaving. This has led to a growing concern for organizations to maintain good management practices to maintain the mental and professional balance of employees and avoid the costs associated with redundancies.

Considering the poor management of companies, Tepper (2000) concludes that abusive supervision of leaders has significant effects on the intention to leave, calling into question the balance of personal and professional life and a significant increase in stress and psychological problems. Rahman (2013) states that employees who are dissatisfied with their manager perform poorly and later start looking for alternative jobs, in addition to negative feelings about their superior management.

That said, Zhang (2016), during his research, concluded that the explicit cost (recruitment, training, productivity) and the hidden costs (reduction in best word of mouth, loss of opportunities and low morale) are results that can materialize if the employee leaves. Similarly, Guzeller and Celiker (2020) state that turnover, which follows the intention to leave, can result in high costs for the organization, loss of talent, redundancy payments, new hires and the costs associated with lost and future training.

To reduce turnover intentions, it is necessary to prepare a set of actions that reduce this impact so that, later, the intention does not become the actual turnover (Fukui et al., 2019). The strategies include leadership training (training in techniques and strategies), improving the conditions of the organization (increasing salaries and benefits and creating opportunities for career progression) and, increasingly, investing in good mental health programs for employees (indicators of work stress and burnout, controlling possible depression and job dissatisfaction) (Fukui et al., 2019).

Despite this, the employee's intention to leave is influenced by intrapersonal factors, such as extrinsic motivations to the company, such as moving to another country or intrapersonal and interpersonal ways of being and thinking.

2.2.1. Toxic Leadership and Turnover Intentions

The leader's possessive and toxic character and personality aim to maintain their reputation and a good image to their superiors (Krasikova et al. 2013). Zhang (2016) concluded that when there is difficulty in interpersonal relationships, such as difficulty in dealing with bosses, workers need to make a great mental effort in their professional lives to contain the bad relationship. Job satisfaction and commitment can be compromised when toxic hierarchical factors are identified within teams (Zhang, 2016). This dissatisfaction is often accompanied by frustration and distress, leading employees to disengage from their workplace.

Khan et al. (2017) research concluded that turnover intentions result from various events within the toxic workplace environment. Low commitment, reduced productivity and increased absenteeism lead to a high-stress level, which increases job dissatisfaction and, consequently, the turnover intentions of the company's employees (Khan et al., 2017). Erickson et al. (2015) added that toxic leadership is strongly linked to the turnover rate, for example, in the United States Army. Finally, Zhang (2016) reinforces that high turnover rates are due to weak and poor management leadership, which consequently translates into a high cost of attracting and retaining employees. The following hypothesis is therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 1:

Toxic leadership positively and significantly affects turnover intentions.

2.3. Emotional Intelligence

Rationality is what differentiates us from other living beings. Critical thinking and decision-making are factors that cut across all human beings and make it possible to contribute to the happiness or sadness of each one of us.

Whether or not an individual is rational depends on the emotions they may feel towards something. Adolphs et al. (2019) explains that an emotion is a state of the brain that causes a certain behavior. This emotion can come from various factors, such as running away from something dangerous or crying with joy (Adolphs et al., 2019). It is important to note that emotion to a single stimulus can vary from individual to individual (Adolphs et al., 2019).

That said, more and more study has begun into the concept of Emotional Intelligence and how it can be used in various contexts.

Emotional intelligence is characterized as the individual's way of perceiving and controlling their emotions (Siddiqui and Hassan, 2013). In the same vein, Goleman-Boyatzis (2018) states that emotional intelligence involves the ability to manage one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate the information gathered and plan future action.

As emotional intelligence is a rather vague topic, Mayer and Salovey (1997) were the pioneers in organizing emotional intelligence into 4 dimensions, these being 1) perceiving emotions; 2) reflecting on emotions; 3) assimilating emotions into thought; 4) perceiving and expressing emotions.

Later, Davies et al. (1998) reorganized the dimensions of emotional intelligence based on the studies of Mayer and Salovery (1997), which was later adopted by Law et al. (2004). This reorganization allowed Law et al. (2004) to conclude that the 4 dimensions would be: 1) evaluation and expression of one's own emotions, which refers to the way in which the individual perceives and understands spontaneous and authentic emotions in a non-verbal way (Peltier, 2011; Rodrigues et al., 2011). It is based on perceiving feelings such as anger, fear, happiness, disgust, sadness, among others (Mayer et al., 2004) and automatically filtering their actions based on this perception (Rodrigues et al., 2011); 2) evaluation and recognition of the emotions of others, which refers to the perception, identification and evaluation of the individual themselves in recognizing and analyzing the emotions of others, allowing for better sensitivity towards others (Peltier, 2011; Rodrigues et al., 2011). This dimension is important as it allows us to distinguish whether emotions have been honest or not (Peltier, 2011); 3) use of emotions to facilitate performance, with the aim of using the best emotions to facilitate performance in activities (Rodrigues et al., 2011). It promotes direction and thinking and priorities around only accomplishing or judging something that is really important, as well as seeing things from a different perspective (Mayer et al., 2004; Peltier 2011); 4) regulating one's emotions, where it is identified by managing emotions and, specifically, regulating their control (Rodrigues et al., 2011) and also rationalizing whether or not one's “self” should turn off emotions in the face of an event or situation that has occurred (Grilo, 2009).

It was based on the studies by Mayer and Salovey (1997), Davies et al. (1998), Law, et al, (2004); Wong and Law, (2002) and Rodrigues et al. (2011) that it was possible to develop and validate the emotional intelligence scale adapted to the Portuguese population (Rodrigues et al. (2011).

That said, Neubauer and Freudenthaler (2005) concluded that emotional intelligence helps cognitive success. Rodrigues et al. (2011) emphasized that emotional intelligence has a multidimensional objective, i.e. it aims to be able to perceive the emotions of the individual and of others, to regulate them well to make good decisions and to use them correctly to achieve harmony between emotions and actions.

2.3.1. Emotional Intelligence and Turnover Intentions

Emotional intelligence provides better quality in the perception and rationalization of emotions. The research by Khosravi et al. (2020) concludes that, from an intrapersonal perspective, emotional intelligence highlights that it allows for an increase in problem-solving and individual and collective behavior. From an interpersonal perspective, Mohammad et al. (2014) show that employees who consider their leader to have a high capacity for emotional intelligence are less likely to intend to leave.

The response of emotional intelligence in the professional context can be useful in that it can help regulate different bosses, pressures or lack of recognition at work (Kong, 2011). From another perspective, teams with a high capacity for emotional intelligence are more attentive and, in turn, can manage their emotions in response to possible conflicts (Khosravi et al., 2020), for example, Abdallah and Mostafa (2021), in an investigation carried out in a public hospital, also conclude that when nurses participate and get involved in decisions together with leaders, they have a higher level of emotional intelligence which, consequently, makes them happier, more altruistic and more civic-minded. To reinforce this idea, Latif et al. (2017) revealed that emotional intelligence has a negative effect on the intention to leave and that previous research has confirmed the existence of a negative relationship between emotional work and the intention to leave (Latif et al., 2017). The following hypothesis is therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 2: Emotional intelligence has a negative and significant effect on exit intentions.

2.3.2. Emotional Intelligence as a Moderating Tool

Emotional intelligence, as mentioned above, is the ability of individuals to control and perceive their emotions and act based on the rationalization of Mayer and Salovey (1997). Studies show that emotional intelligence works as a defense mechanism, as exemplified by Peng et al. (2019), who states that emotional intelligence is a very important factor in people's lives and can be a protective and decisive factor in resilience. As such, emotional intelligence helps humans protect themselves from external factors.

Recent research has shown that emotional intelligence can be relied on as a moderating tool, especially in the workplace. Batool (2013) concluded that it is possible to control negative situations through emotional intelligence and complemented his idea by showing that self-awareness is knowing how to recognize and manage one's emotions for the well-being of others and oneself. He also concludes that self-regulation is about controlling words, decisions, stereotypes and concern for the values of others. Self-regulation is knowing how to control the self even in stressful situations (Batool, 2013).

In the same vein, Dasborough (2019), in his research into the moderating effects of emotional intelligence, found that individuals with high levels of emotional intelligence are more likely to use this mechanism to manage and regulate their emotions. In contrast, the author states that individuals with a lower level of emotional intelligence cannot manage and regulate emotions easily (Dasborough, 2019).

Jordan et al. (2002) considers that emotional intelligence favors workers to the extent that they can deal with stress and possible job insecurities. In turn, the author states that high emotional intelligence in employees improves the management of negative reactions to less pleasant situations (Dasborough, 2019; Jordan et al., 2002).

Finally, Lubit (2004) identified that knowing how to deal with toxic leadership in organizations significantly impacts personal careers. Individuals who can recognize the actions and attitudes of others are in a good position to protect and help themselves. The following hypothesis is therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 3: Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions.

The hypotheses formulated in this study are summarized in

Figure 1:

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

A total of 202 individuals took part in this study voluntarily. The conditions for participating in this study were that they had to be 18 years old or over and work in organizations based in Portugal. The sampling process was non-probabilistic, convenient and intentional snowball sampling (Trochim, 2000). This scientific study is quantitative and non-experimental since the predictor variable (toxic leadership) is not manipulated. This study has a correlational structure since the aim is to study whether there is a relationship between the following variables: toxic leadership, turnover intentions and emotional intelligence. This study is cross-sectional as the data was collected at a single point in time and hypothetical-deductive (Reto and Nunes, 1999).

The questionnaire was created online on the Google Forms platform, and its link was sent via email and LinkedIn. Before answering the questionnaire, the participants were given informed consent and could decide whether they wanted to participate in the study. The informed consent form guaranteed the confidentiality of the answers given. After reading the informed consent, they were asked if they agreed to participate in the questionnaire. If the participants answered no, they were taken to the end of the questionnaire; if they answered yes, they were taken to the next section.

The questionnaire included sociodemographic questions to characterize the sample, including age in years, gender, seniority in the organization, educational qualifications, marital status, sector of activity and type of contract. In addition to these questions, the participants answered three scales: toxic leadership, turnover intentions and emotional intelligence.

3.2. Participants

The sample in this study consisted of 202 participants. In terms of age, 58 participants were aged between 18-29 (28.7%), 103 were aged between 30-49 (51%) and 41 were aged 50-67 (39.6%). Of the total number of participants, 122 were female (60.4%) and 80 were male (39.6%), with a predominance of females. About the participants' educational qualifications, 13 had a basic level of education (6.4%), 72 had completed secondary school (35.6%), 83 had a bachelor's degree (41.1%), and 34 had a master's degree (16.8%). There were no participants with a PhD. Concerning seniority in the company/organization, 28 of the participants had been there for less than 1 year (13.9%), 58 for between 1 and 3 years (28.7%), 39 for between 4 and 6 years (19.3%), 15 for between 7 and 9 years (7.4%), 24 for between 10 and 15 years (11.9%) and 38 for more than 15 years (18.8%). As for the sector of activity, 36 of the participants are in the public sector (17.8%), 153 in the private sector (75.7%) and 13 in the public-private sector (6.4%). Finally, when asked about their contract, 27 answered that they were on an uncertain-term contract (13.4%), 21 on a fixed-term contract (10.4%), 145 on an open-ended contract (71.8%) and nine on another type of contract (4.5%).

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

Once the data had been collected, it was imported into SPSS Statistics 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA) for processing. The metric qualities of the instruments used in this study were initially tested. Confirmatory factor analyses were carried out using AMOS Graphics 29 software to test the validity of the instruments (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA). Confirmatory factor analysis is used to assess the quality of fit of a theoretical measurement model to the correlational structure observed between the manifest variables (items) (Marôco, 2021). The procedure followed a "model generation" logic (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993). Six fit indices were combined, as recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999): Chi-square ratio/degrees of freedom (χ²/gl); Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI); Goodness Fit Index (GFI); Comparative Fit Index (CFI); Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA); Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR). The chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/gl) must be less than 5. The CFI, GFI and TLI values must equal or exceed 0.90. As for RMSEA, its value must be less than 0.08 (McCallum et al. 1996). The lower the RMSR, the better the fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). With the data obtained from the confirmatory factor analysis, the construct reliability was calculated for each of the dimensions of the scales and the respective convergent validity (by calculating the AVE value). Construct reliability values must be greater than 0.70, and the AVE value must be equal to or greater than 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). However, according to Hair et al. (2011), if the reliability is higher than 0.70, AVE values of 0.40 or higher are acceptable. The internal consistency of each of the dimensions of the scales was also tested by calculating Cronbach's alpha, whose value should be equal to or greater than 0.70 in organizational studies (Bryman and Cramer 2003).

The items' sensitivity was also tested by calculating the measures of central tendency and shape. The items must have responses at all points, no asymmetry at one of the extremes, and their absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis must be less than 2 and 7, respectively (Finney and DiStefano 2013).

Next, we carried out descriptive statistics on the variables under study, using Student's t-tests for independent samples. To test the effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study, we used Student's t-tests for independent samples (when the independent variable was made up of two groups) and the One-Way ANOVA test (when the independent variable was made up of more than two groups). The association between the variables under study was tested using Pearson's correlations. Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested using simple and multiple linear regressions. Hypothesis 3, which assumes a moderating effect, was tested using Macro Process 4.2, developed by Hayes (2022).

3.4. Instruments

To assess the toxic leadership dimension, the Portuguese version by Mónico et al. (2019) was used, based on the Toxic Leadership Scale by Schmidt (2008), consisting of 30 items with a 6-point Likert-type response, where one corresponds to "Strongly Disagree" and 6 to "Strongly Agree". These 30 items are divided into five dimensions: self-promotion (items 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23); abusive supervision (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7); unpredictability (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30); authoritarian leadership (items 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13); Narcissism (items 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18). Once the confirmatory factor analysis had been carried out, it was found that not all the fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/df = 2.67; GFI = 0.81; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.074; SRMR = 0.112) and that the five factors were strongly correlated with each other. A confirmatory factor analysis was then carried out. This time, the fit indices obtained were adequate, or their values were very close to adequate (χ²/df = 2.67; GFI = 0.81; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.074; SRMR = 0.112). A composite reliability value of 0.97 and an AVE value of 0.57 were obtained, indicating that this instrument has good composite reliability and convergent validity. As for internal consistency, it has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.98. Regarding the sensitivity of the items, all items have responses at all points, but items 2, 8, 10, 11, 12, 23, 26, 27, 29 and 30 have the median towards the lower end. However, their absolute asymmetry and kurtosis values are below 2 and 7, respectively, which indicates that they do not grossly violate normality.

To measure turnover intentions, we used the instrument developed by Bozeman and Perrewé (2001) and translated and adapted for the Portuguese population by Bártolo-Ribeiro et al. (2018). The scale is made up of 6 items, classified using a 5-point Likert scale: 1 "Does not apply to me at all"; 2 "Applies to me a little"; 3 "Applies to me in part"; 4 "Applies to me a lot"; 5 "Applies to me completely". This is a one-dimensional instrument. A one-factor confirmatory factor analysis was carried out. The fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/df = 2.88; GFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.078; SRMR = 0.039). Composite reliability was 0.93, and convergent validity had an Ave value of 0.67. It can be concluded that both composite reliability and convergent validity have good values. As for internal consistency, it has a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.93. Regarding the sensitivity of the items, all items have responses at all points, and only item 5 has a median towards the lower end. However, their absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis are below 2 and 7, respectively, which indicates that they do not grossly violate normality.

We used the Portuguese version of Wong and Law's Emotional Intelligence Scale (2002) - WLEIS - P analyzed and translated by Rodrigues et al. (2011) to measure Emotional Intelligence. The scale consists of 16 items which are grouped into four dimensions: evaluation of one's own emotions (items 1, 2, 3 and 4); evaluation of the emotions of others (items 5, 6, 7 and 8); use of emotions (items 9, 10, 11 and 12); regulation of emotions (items 13, 14, 15 and 16). The answers to the items were classified using a Likert scale where point 1 corresponds to "Strongly Disagree" and point 5 "Strongly Agree". The fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/df = 2.88; GFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.078; SRMR = 0.039). Composite reliability ranges from 0.79 (appraisal of others' emotions) to 0.89 (emotion regulation). As for convergent validity, the AVE values range from 0.49 (appraisal of others' emotions) to 0.57 (emotion regulation). Regarding internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha values range from 0.78 (appraisal of others' emotions) to 0.89 (emotion regulation). Concerning the sensitivity of the items, none of the items has a median close to one of the extremes, but items 1, 4, 6 and 8 do not have responses at point 1. However, their absolute asymmetry and kurtosis values are below 2 and 7, respectively, which indicates that they do not grossly violate normality.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables under Study

The descriptive statistics of the variables under study were first carried out to find out the position of the answers given by the participants to the instruments used in this study.

The answers given to the toxic leadership instrument are significantly below the scale's central point (3.5), which indicates that the participants in this study do not perceive their leader as toxic (

Table 1).

Turnover intentions were also significantly below the scale's midpoint (3), indicating that these participants have low turnover intentions (

Table 1).

The participants' answers to emotional intelligence questions are significantly above the midpoint of the scale, indicating that they have high levels of emotional intelligence (

Table 1). Among the dimensions that make up this instrument, the one with the highest average is evaluating one's own emotions, and the lowest is regulating emotions (

Table 1).

4.2. Effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study

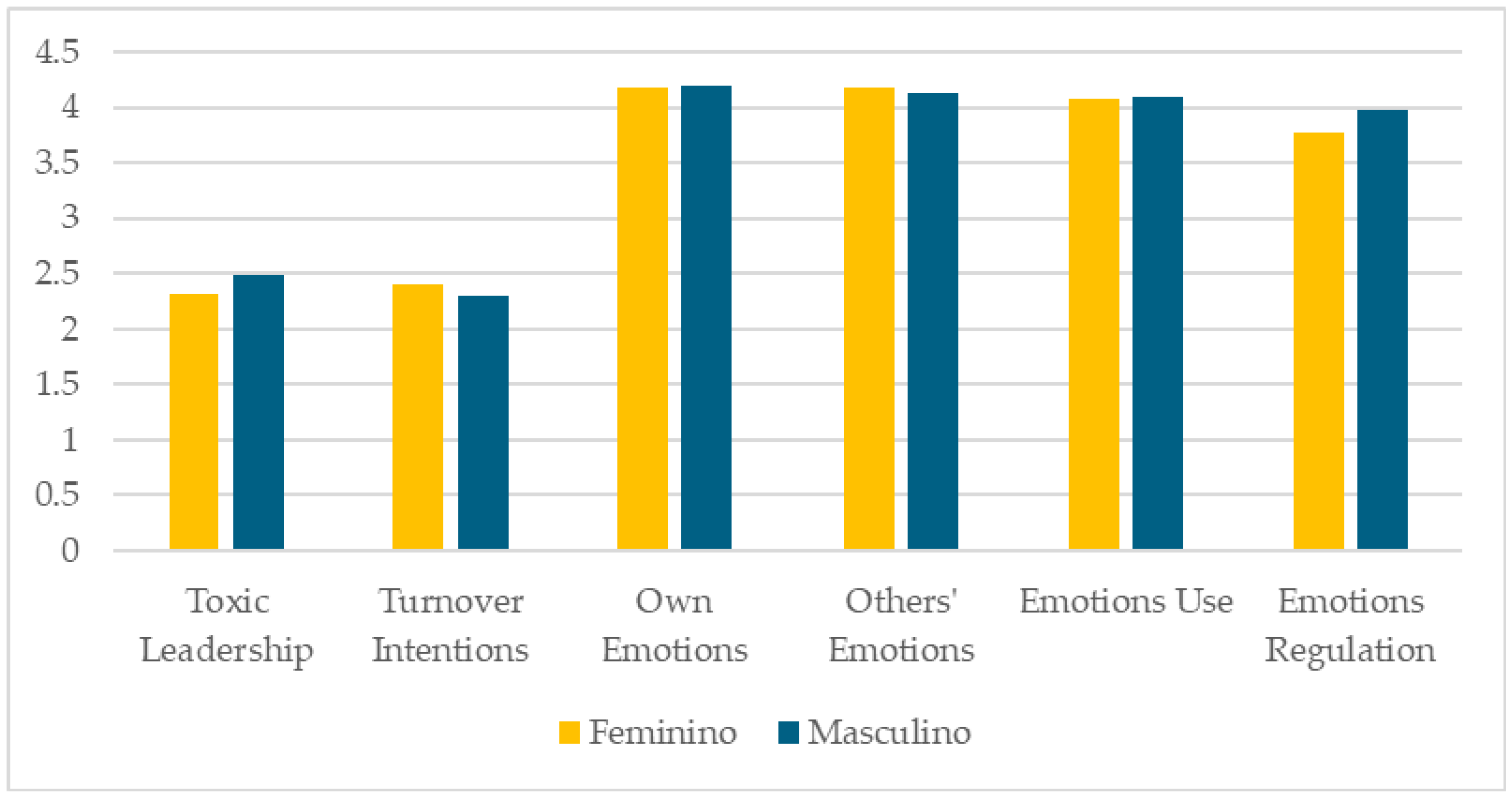

The results show that there are no statistically significant differences in the variables under study depending on the gender of the participants. However, male participants perceive their leader as more toxic than female participants (

Figure 2). In terms of emotion regulation, male participants also regulate their emotions better (

Figure 2). On the other hand, female participants have more intentions to leave (

Figure 2).

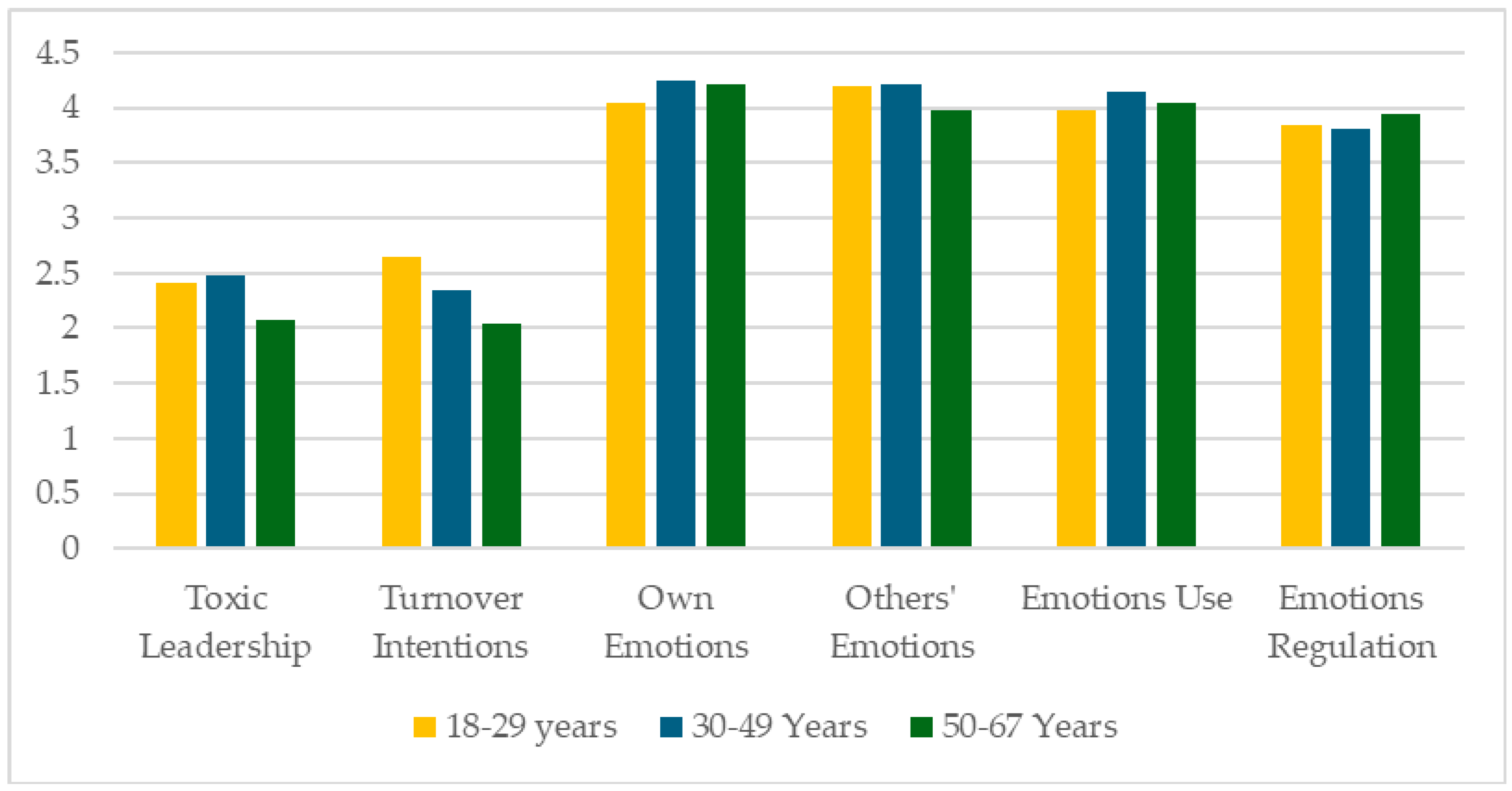

Concerning the effect of the age group to which the participant belongs, there are only statistically significant differences regarding turnover intentions (F (2, 199) = 3.29, p = 0.039). Participants aged between 18 and 29 differ significantly from those between 50 and 67, showing significantly higher turnover intentions (

Figure 3). Participants aged between 30 and 49 perceive their leader as more toxic and have higher levels of emotional intelligence in all dimensions except emotion regulation (

Figure 3). Participants aged between 50 and 67 showed the highest levels of emotion regulation (

Figure 3).

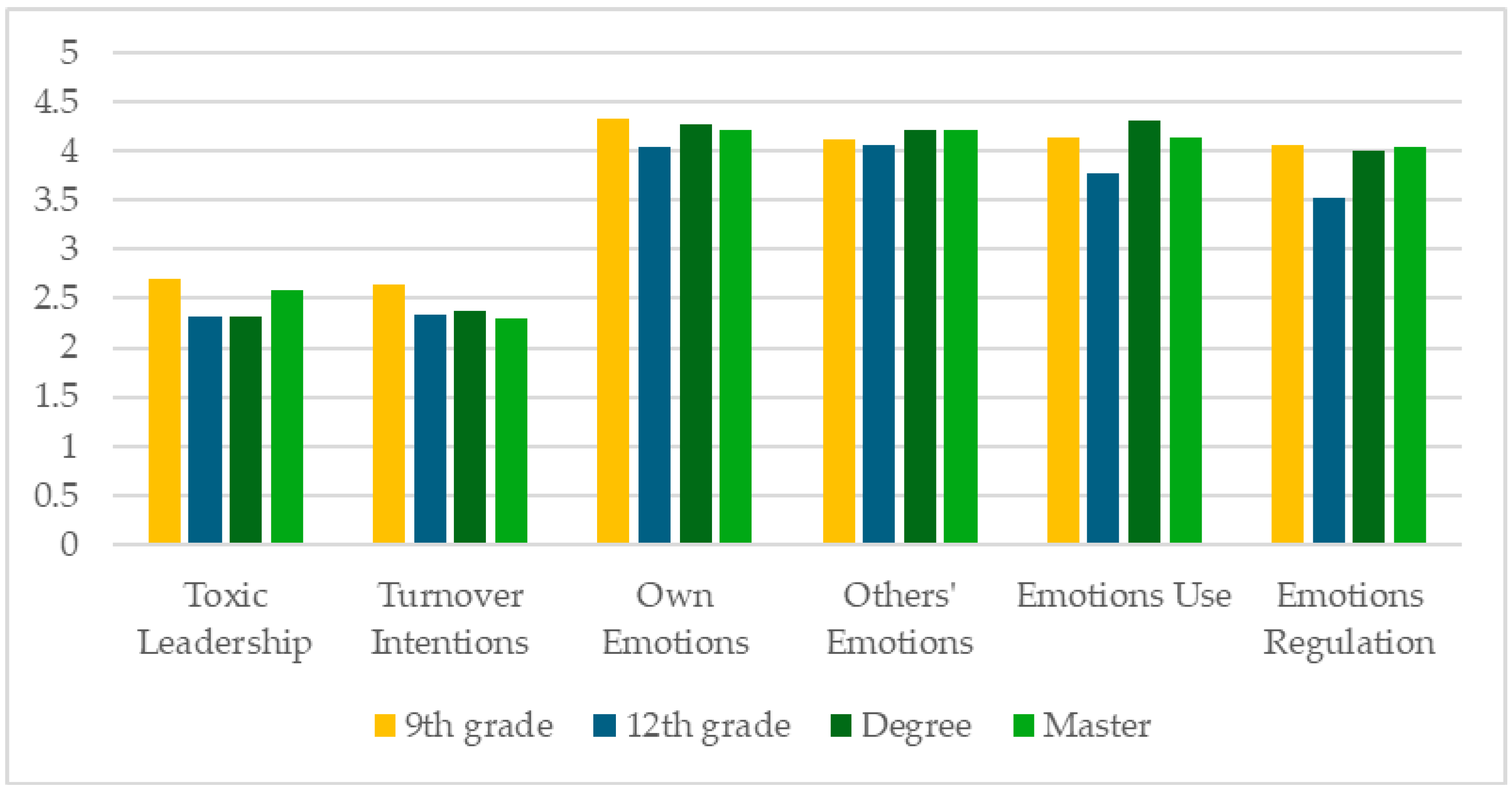

The participant's level of education only has a statistically significant effect on emotion use (F (3, 198) = 7.15, p < 0.001) and emotion regulation (F (3, 198) = 7.48, p < 0.001). Concerning emotion use, participants with a 12th-grade degree differed significantly from those with a bachelor's degree, with participants with a bachelor's degree showing significantly higher levels of emotion use (

Figure 4). As for emotion regulation, participants with a 12th-grade degree showed significantly lower levels of emotion regulation than participants with a bachelor's or master's degree (

Figure 4). Although the differences are not statistically significant, participants with a 12th-grade degree perceive their leader as more toxic when compared to the other participants and have more turnover intentions (

Figure 4).

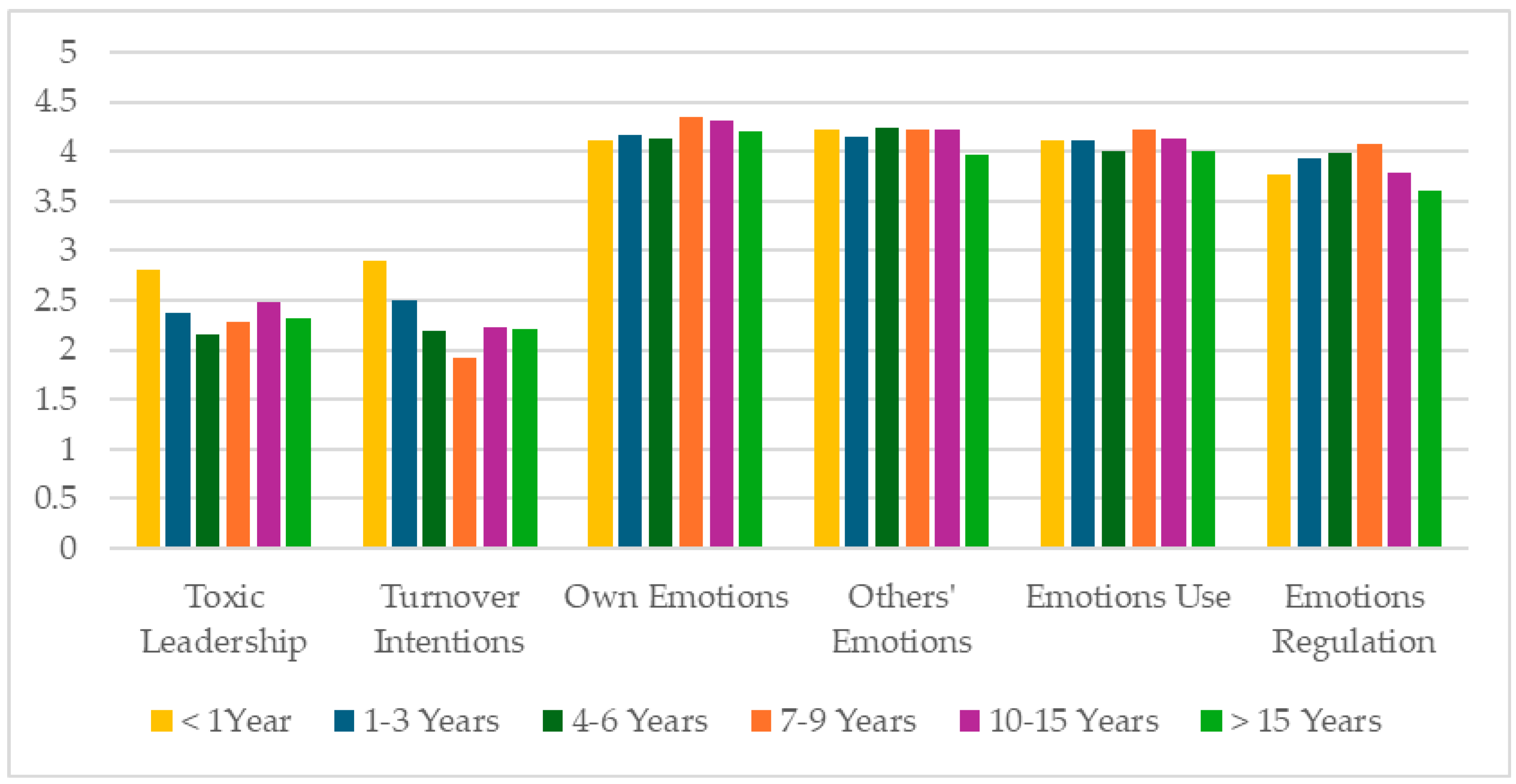

The results show that seniority in the organization does not statistically affect any of the variables under study. However, employees who have been with the organization for less time perceive their leader as the most toxic and have the highest turnover intentions (

Figure 5). On the other hand, participants who have been with the organization for between 7 and 9 years have the lowest turnover intentions but the highest levels of self-emotions, use of emotions, and emotion regulation (

Figure 5).

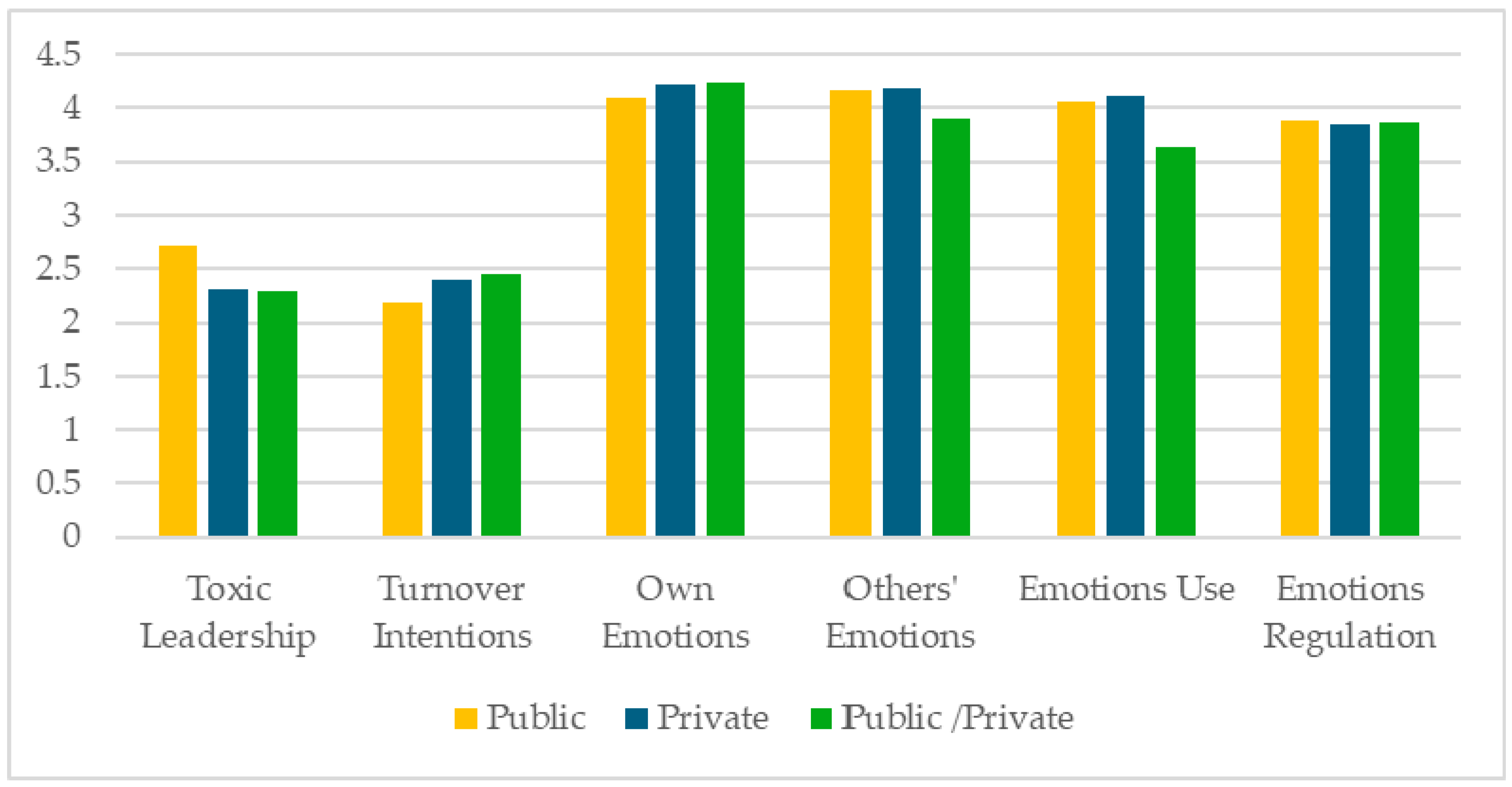

It was found that the sector of work did not significantly affect the variables under study. However, employees working in the public sector perceive their leader as the most toxic but have the lowest turnover intentions (

Figure 6). Employees working in the private-public sector have higher levels of self-emotions but lower levels of emotions of others and use of emotions (

Figure 6).

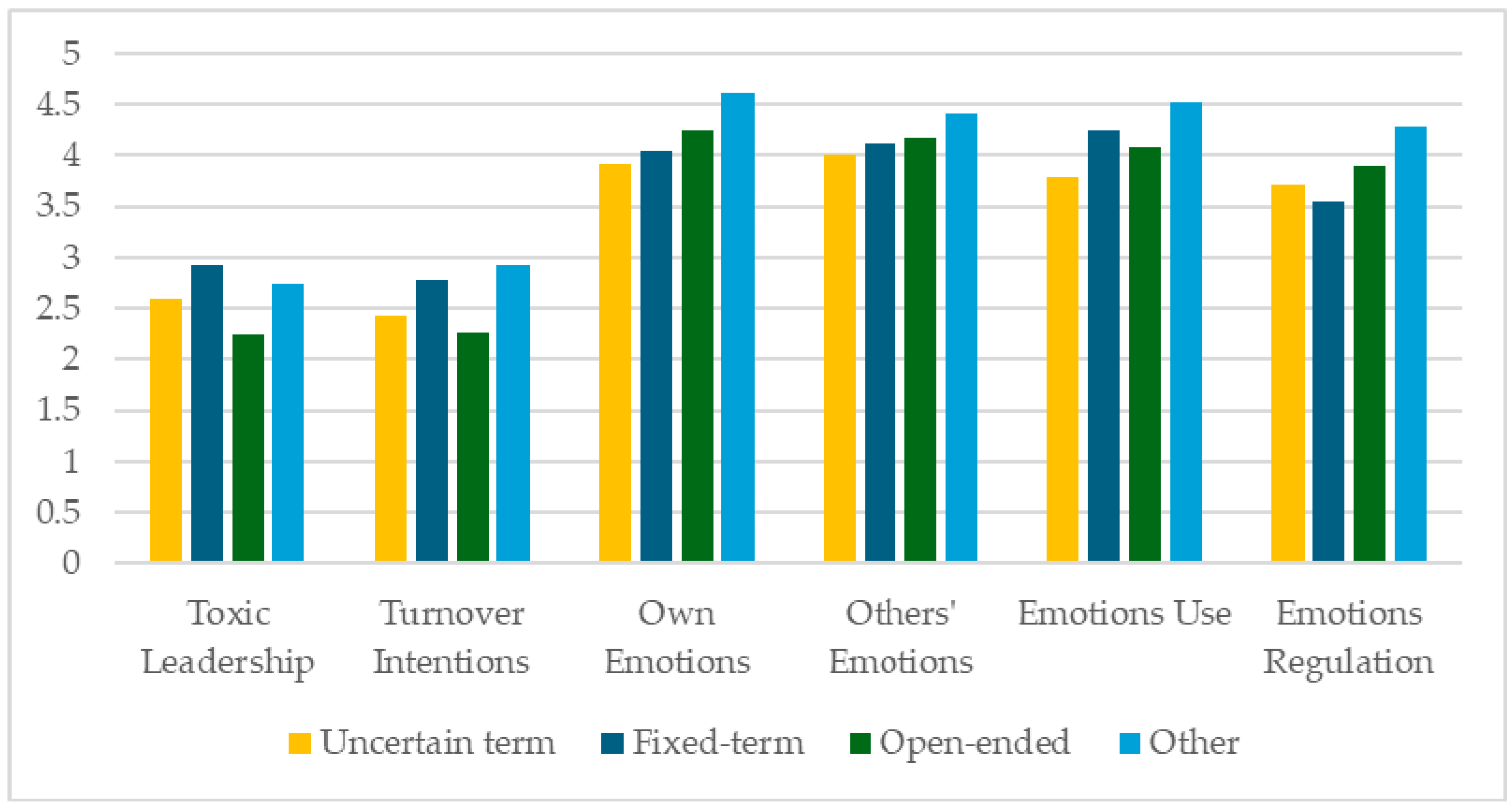

The results show that the type of employment contract has a statistically significant effect on toxic leadership (F (3, 198) = 2.78, p = 0.042), on one's own emotions (F (3, 198) = 4.45, p = 0.005), on the use of emotions (F (3, 198) = 2.77, p = 0.043) and on the regulation of emotions (F (3, 198) = 2.66, p = 0.049). Participants with a fixed-term contract differ significantly from those with an open-ended contract in how they perceive their boss's leadership, with participants with a fixed-term contract perceiving their leader as more toxic (

Figure 7). Participants with an open-ended contract have significantly lower self-emotion levels than participants with a fixed-term or other type of contract (

Figure 7). Participants with another type of contract have significantly higher levels of emotions use and emotion regulation than participants with open-ended and fixed-term contracts, respectively (

Figure 7).

4.3. Association between the Variables under Study

Toxic leadership is only positively and significantly associated with turnover intentions, which indicates that when employees perceive their leader as toxic, their turnover intentions increase (

Table 2). The emotions of others and the use of emotions are negatively and significantly associated with turnover intentions, i.e. participants with higher levels of emotions of others and use of emotions have lower turnover intentions (

Table 2).

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

To test hypothesis 1, a simple linear regression was performed.

The results show that toxic leadership has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (β = 0.60; p < 0.001), which indicates that when employees perceive their leaders as toxic, their turnover intentions increase (

Table 3).

A coefficient of 0.36 was obtained, which means that the model is responsible for 36% of the variability in turnover intentions. The model is statistically significant (F (1, 200) = 114.86; p < 0.001) (

Table 3). The results support this hypothesis.

To test hypothesis 2, a multiple linear regression was carried out.

The results show that only the others' emotions (β = -0.20; p = 0.017) and emotions use (β = -0.16; p = 0.048) dimensions have a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions, indicating that when employees have high levels of these two dimensions, their turnover intentions decrease (

Table 4).

A coefficient of 0.04 was obtained, which means that the model accounts for 4% of the variability in turnover intentions. The model is statistically significant (F (4, 197) = 2.94; p = 0.022) (

Table 4). The results partially support this hypothesis.

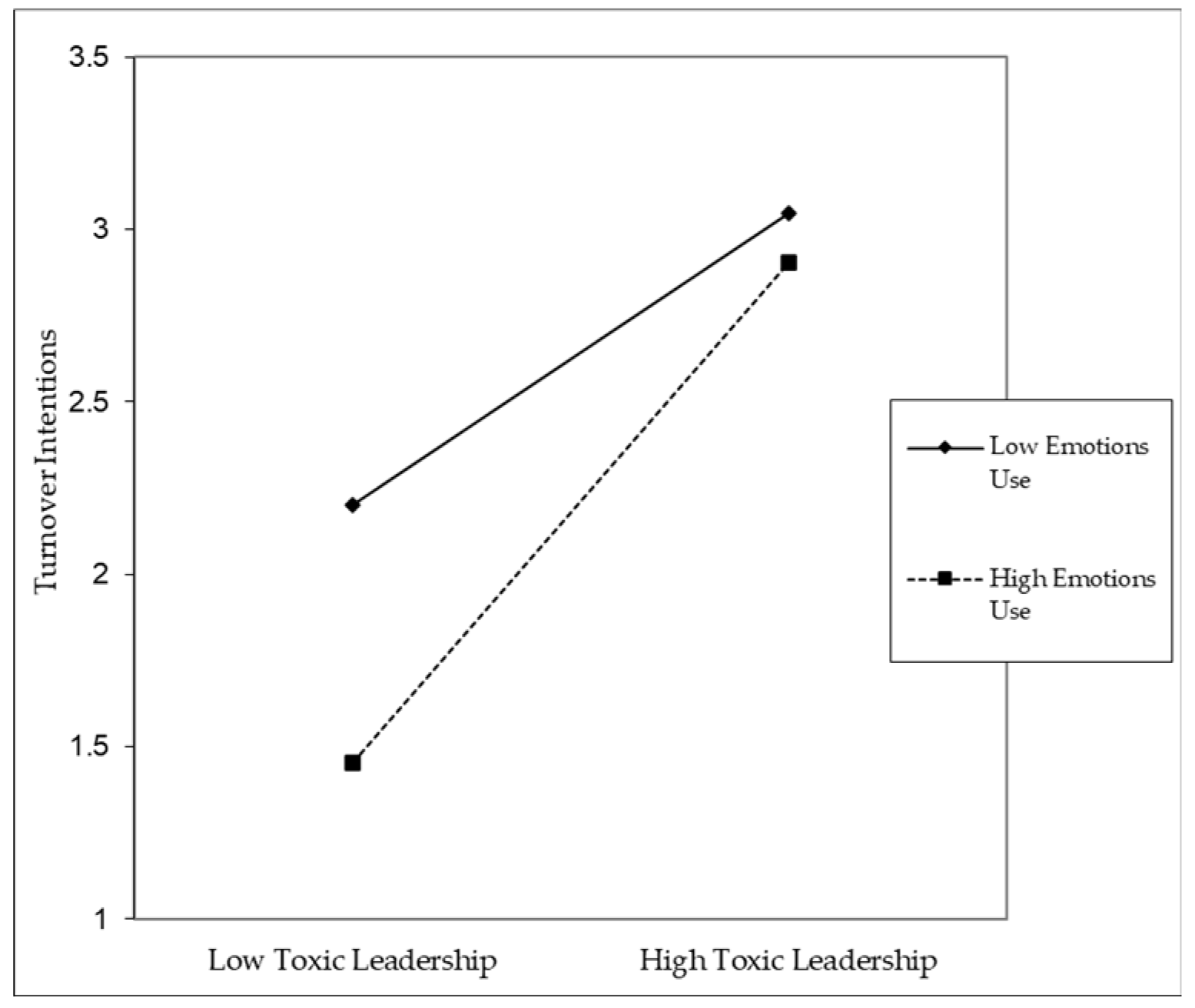

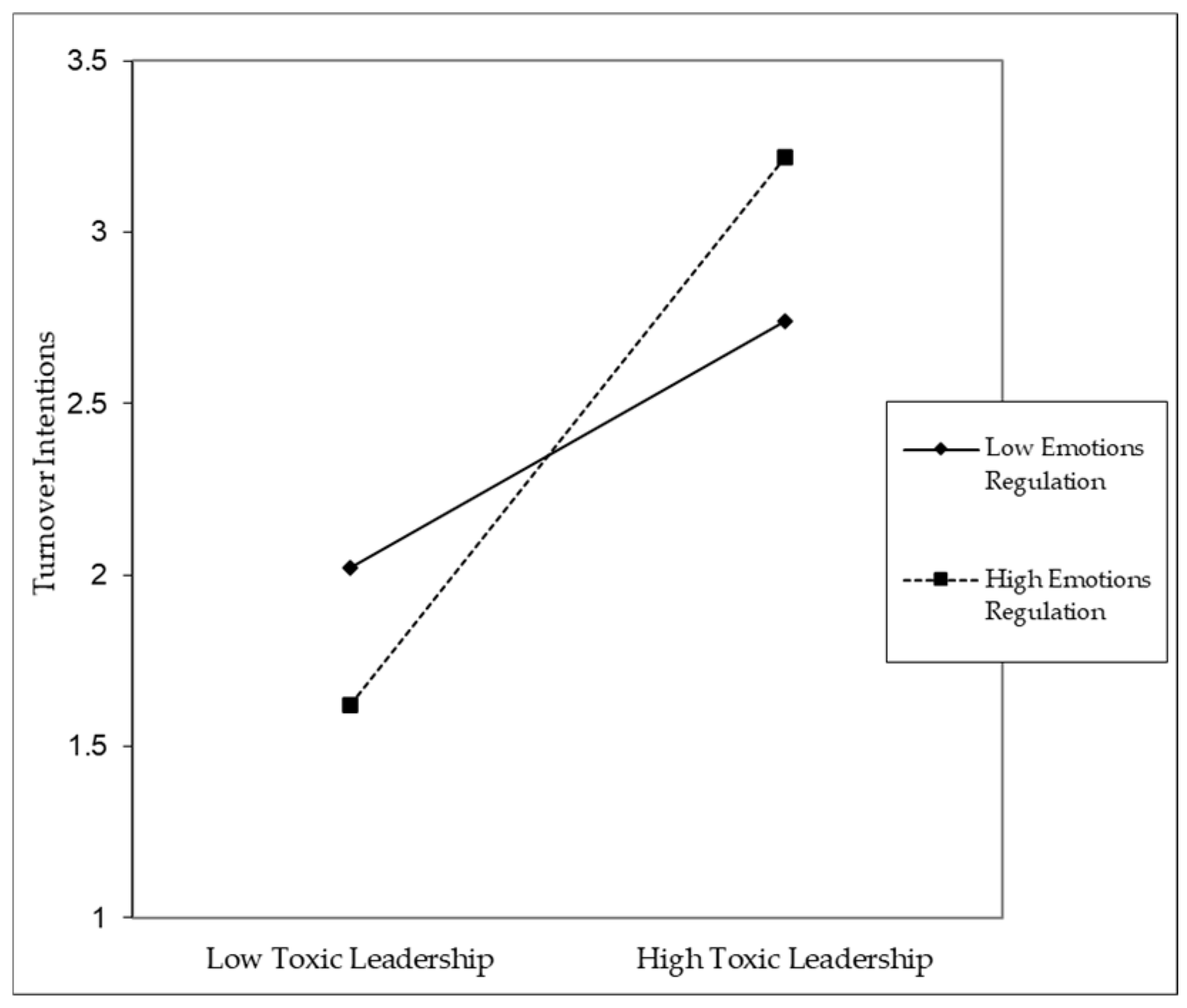

Hypothesis 3 assumed a moderating effect, so Hayes's (2022) Macro Process 4.2 was used to test this hypothesis.

The results show that only the dimensions of emotion use, and emotion regulation moderate the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions (

Table 5). The results partially support this hypothesis.

For participants with high levels of emotional use, the perception that their leader is toxic becomes relevant to boosting their turnover intentions compared to participants with low levels of emotional use (

Figure 8).

For participants with high levels of emotion regulation, the perception that their leader is toxic becomes relevant to boosting their turnover intentions compared to those with low levels of emotion regulation (

Figure 9).

5. Discussion

The main objective of this research was to understand the impact of toxic leadership on employee turnover, as moderated by emotional intelligence.

The results of hypothesis 1 conclude that toxic leadership positively and significantly affects turnover intentions. The statistical analysis shows the strong effect of toxic leadership on turnover intentions, with significant and positive values, demonstrating that the more toxic leadership in organizations, the greater the employee's intention to leave. This conclusion aligns with various studies, such as Weberg and Fuller's (2019) research, which states that toxic leadership increases employee turnover intentions. The behaviors and attitudes of control, suppression and ridicule (Wilson-Starks, 2003) towards subordinates lead to their desire to look for an organization that will help them progress, congratulate them and help them professionally.

Hypothesis 2 was partially proven, as only the dimensions of emotions of others and the use of emotions have a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions. These results are in line with the literature. Latif et al. (2017) state that emotional intelligence hurts turnover intentions. The correct use of emotions has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions, as employees adapt better to less pleasant behaviors and situations, thus reducing their turnover intentions (Giao et al., 2020; Khosravi et al., 2020; Riaz et al., 2018).

The data analysis regarding moderation yielded interesting results. The results indicate that only the dimensions of using and regulating emotions moderate the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions. The graphs show that employees with greater and better use of emotions and emotion regulation, when faced with the perception that their leader has toxic behaviors, have higher turnover intentions, i.e. employees with a good and great ability to use and regulate their emotions intend to leave more quickly when faced with toxic leadership, moving away from toxic environments in search of their well-being and professional progression in organizations that provide them with this growth. These results go against what the literature tells us, as some authors claim that the correct use and regulation of emotions allow employees to adapt quickly to behaviors and situations to reduce their turnover intentions (Giao et al., 2020; Khosravi et al., 2020; Riaz et al., 2018). These results may be because around 80% of the participants were up to 49 years old. In addition, participants aged between 18 and 29 have the highest exit intentions, followed by participants aged between 30 and 49. Participants aged between 18 and 29 also have lower emotion use and regulation levels. Another factor may be that more than 60% of the participants have been with the organization for up to 6 years, and precisely, these participants showed the most turnover intentions.

It should also be noted that the participants in this study have a low perception of toxic behavior on the part of their leader and low turnover intentions. On the other hand, they have high levels of emotional intelligence, with the self-emotions dimension having the highest average and the emotion regulation dimension having the lowest average.

Participants who work in the public sector perceive higher levels of toxic leadership in their leaders. As for the effect of academic qualifications on the variables under study, it is the participants with a 9th-grade education who perceive their leader as having more toxic behaviors and who have higher levels of turnover intentions. Participants with a 12th-grade education had the lowest levels of emotional intelligence.

5.1. Limitations and Future Studies

During the research, it was possible to find some gaps which limited the analysis, and which should be considered for future studies.

The first limitation relates to the small number of participants. Another limitation concerns the data collection procedure and the use of a self-report questionnaire. However, several methodological and statistical recommendations were followed to reduce the impact of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Since this study was collected from various organizations and individuals, for future studies, it would be important and interesting to study and question organizations that have high rates of intention to leave and to see if one of the reasons could be the poor leadership of their managers.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The main contribution of this study was to increase the number of studies and analyses of the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions and whether emotional intelligence moderates this relationship. As seen above, the results of the study were partially proven.

That said, I intend to use this work to add to existing research and explore the dimensions of emotional intelligence.

With this in mind, and following the study's conclusion, the questions arise: 1) Are employees who show that they have a toxic leader and express their intention to leave only due to poor leadership, or are there other variables that reinforce this intention? 2) Are toxic leaders who have undergone leadership skills recognition through career progression or external admission? 3) Do organizations recognizing that their employees intend to leave in the face of leadership take preventive measures? 4) Is an employee who builds defense strategies against toxic leadership happy and motivated?

In this sense, organizations need to contribute to their employees' well-being and happiness and not promote toxic leaders. At an early stage, it is the organization's responsibility to recognize or promote leaders who have completed certified leadership courses, and before they start working, they go through a trial period without knowing they are being assessed. One strategy is to create Personal Development Plans (PDP) based on non-participant, naturalistic observation. This observation makes it possible to assess the subjects in their typical, natural environment and understand whether they are competent for the job.

On the other hand, organizations should carry out quarterly feedback interviews to determine whether there are any shortcomings or if employees intend to leave. This way, quick and objective action can be taken to identify problems associated with leaders.

Another practice is to offer wellness consultations, mainly on emotional intelligence, to determine whether employees are emotionally intelligent in all or some dimensions.

Finally, and to combat toxic leadership effectively, if organizations identify one of these leaders, countermeasures, such as inviting them to leave the company, are mandatory to prevent hard-working and talented employees, especially those with high emotional intelligence, from expressing their intention to leave.

6. Conclusions

Emotional intelligence provides better quality in the perception and rationalization of emotions. The research by Khosravi et al. (2020) concludes that, from an intrapersonal perspective, emotional intelligence highlights that it allows for an increase in problem-solving and individual and collective behavior. From an interpersonal perspective, Mohammad et al. (2014) show that employees who consider their leader to have a high capacity for emotional intelligence are less likely to turnover intentions.

This study concludes that when employees perceive toxic behavior in their leader, their intentions to leave increase, confirming what other authors have said. According to Khan et al. (2017), turnover intentions result from various events within the toxic workplace environment.

As for the dimensions of emotional intelligence, only consideration for the emotions of others and the use of one's own emotions significantly reduce turnover intentions, confirming what Khosravi et al. (2020) say that the correct use of emotions reduces intentions to leave.

Only the mediating effect of emotions and emotion regulation on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions was proven. However, the relationship was not in line with the literature since for participants with high levels of emotion use and emotion regulation, compared to participants with low levels of emotion use and emotion regulation, the fact that they perceive their leader as toxic increases their exit intentions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and A.S.; methodology, A.P.-M.; software, A.P.-M.; validation, T.L., A.S. and A.P.-M.; formal analysis, A.P.-M.; investigation, T.L.; resources, T.L.; data curation, T.L. and A.P.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L. and A.S..; writing—review and editing, T.L., A.S. and A.P.-M.; visualization, T.L. and A.S.; supervision, T.L. and A.S.; project administration, T.L., A.S. and A.P.-M.; funding acquisition, A.P.-M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since all participants (before answering the questionnaire) needed to read the informed consent portion and agree to it. This was the only way they could complete the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, as well as that the results were confidential, as individual results would never be known and would only be analyzed in the set of all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because in their informed consent, participants were informed that the data were confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- (Abdallah and Mostafa 2021) Abdallah, Samah Abo-Elenein, and Sara Abdel-Mongy Mostafa. 2021. Effects of Toxic Leadership on Intensive Care Units Staff Nurses’ Emotional Intelligence and Their Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Tanta Scientific Nursing Journal, 22(3), 211-240. [CrossRef]

- (Adolphs et al. 2019) Adolphs, R.alph, Leonard Mlodinow, and Lisa Barrett. 2019. What is an emotion?. Current biology, 29(20). [CrossRef]

- (Alam and Asim 2019) Alam, Aliya, and Mohammad Asim. 2019. Relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 9(2), 163. [CrossRef]

- (Aravena 2019) Aravena, Felipe. (2019). Destructive leadership behavior: An exploratory study in Chile. Leadership and policy in schools, 18(1), 83-96. [CrossRef]

- (Arshad and Puteh 2015) Arshad, Hidayati, and Fadilah Puteh. 2015. Determinants of turnover intention among employees. Journal of Administrative Science, 12(2), 1-15.

- (Bártolo-Ribeiro 2018) Bártolo-Ribeiro, Rui 2018. Desenvolvimento e Validação de uma Escala de Intenções de Saída Organizacional. In Diagnóstico e Avaliação Psicológica: Atas do 10º Congresso da AIDAP/AIDEP. Edited by Marcelino Pereira, Isabel M. Al-berto, Josée J. Costa, José T. Silva, Cristina P. A. Albuquerque, Maria J. S. Santos, Manuela P. Vilar and Teresa M. D. Rebelo. AIDAP/AiDEP, Coimbra; pp. 378–90, ISBN:978-989-20-9329-1/978-989-20-9341-3.

- (Batool 2013) Batool, Bano F. 2013. Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Journal of business studies quarterly, 4(3), 84-94.

- (Bolden 2004) Bolden, Richard. 2004. What is leadership?. Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter.

- (Bozeman and Perrewé 2001) Bozeman, Dennis P., and Pamela L. Perrewé. 2001. The effect of item content overlap on organiza-tional commitment ques-tionnaire—Turnover cognitions relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 161–73.

- (Burt et al. 2009) Burt, Christopher D., Nik Chmiel, and Peter Hayes. (2009). Implications of turnover and trust for safety attitudes and behaviour in work teams. Safety Science, 47(7), 1002-1006. [CrossRef]

- (Bryman and Cramer 2003) Bryman, Alan, and Duncan Cramer. 2003. Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows, 3rd ed. Oeiras: Celta.

- (Carmeli, and Weisberg 2006)) Carmeli, Aabraham, and Jacob Weisberg. 2006. Exploring turnover intentions among three professional groups of employees. Human Resource Development International, 9(2), 191-206.

- (Chen et al. 2004) Cheng, Bor-Shiuan, Li-Fang Chou, Tsung-Yu Wu, Min-Ping Huang, and Jiing-Lih Farh. 2004. Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian journal of social psychology, 7(1), 89-117. [CrossRef]

- (Davies et al. 1998) Davies, Michaela D., Lazar Stankov, and Richard D. Roberts. 1998. Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 989–1015. [CrossRef]

- (Dasborough 2019) Dasborough, Marie T. (2019). Emotional intelligence as a moderator of emotional responses to leadership. In Emotions and leadership (pp. 69-88). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- (DePree 1998) DePree, Max. 1998. What is leadership. Leading organizations: Perspectives for a new era, 130-132.

- (Dobbs 2014) Dobbs, James M. 2014. The Relationship between Perceived Toxic Leadership Styles, Leader Effectiveness, and Organizational Cynicism. Dissertations. 854. https://digital.sandiego.edu/dissertations/854.

- (Einarsen et al. 2007) Einarsen, Ståle Valvatne, Merethe Schanke Aasland, and Anders Skogstad. 2007. Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The leadership quarterly, 18(3), 207-216. [CrossRef]

- (Erickson et al. 2015) Erickson, Anthony, Ben Shaw, Jane Murray, and Sara Branch. 2015. Destructive leadership: Causes, consequences and countermeasures. Organizational Dynamics, 44(4), 266-272. [CrossRef]

- (Ferreira et al. 2021) Ferreira, Andreia F., Ana Sabino, and Francisco Cesário. 2021 (October). Líderes tóxicos, comportamentos destrutivos: Um estudo sobre a influência da Liderança Tóxica no Modelo EVLNS. In Conferência-Investigação e Intervenção em Recursos Humanos (No. 10).

- (Finney and DiStefano 2013) Finney, Sara J., and Cristine DiStefano. 2013. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA; pp. 439–492.

- (Fornell and Larcker 1981) Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measure-ment error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50.

- (Fukui et al. 2019) Fukui, Sadaaki, Angela L. Rollins, and Michelle Salyers. 2019. Characteristics and job stressors associated with turnover and turnover intention among community mental health providers. Psychiatric Services, 71(3), 289-292. [CrossRef]

- (Giao et al. 2020) Giao, Ha Nam Khanh, Bui Nhat Vuong, Dao Duy Huan, Hasanuzzaman Tushar and Tran Nhu Quan. 2020. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from the Banking Industry of Vietnam. Sustainability, 12(5), 1857; [CrossRef]

- (Goleman 2011) Goleman, Daniel. 2011. Leadership: The Power of Emotional Intelligence. More Than Sound: Northampton, MA.

- (Goleman et al. 2018) Goleman, Daniel, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee. 2018. O poder da inteligência emocional: Como liderar com sensibilidade e eficiência. Objetiva.

- (Grill et al. 2017) Grill, Martin, Anders Pousette, Kent Jacob Nielsen, Regine Grytnes, and Marianne Törner. 2017. Safety leadership at construction sites: The importance of rule-oriented and participative leadership. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(4), 375–384. [CrossRef]

- (Grilo 2009) Grilo, Raquel Maria Batista. 2009. Inteligência emocional nas organizações: colaboradores motivados e com desempenho emocionalmente inteligente? (Dissertação de Mestrado, Instituto Superior de Psicologia Aplicada). http://hdl.handle.net/10400.12/4904.

- (Guzeller and Celiker 2020) Guzeller, Cem Oktay, and Nun Celiker. 2020. Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 102-120. [CrossRef]

- (Hair et al. 2011) Hair, Joseph, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 139–51.

- (Hayes 2022) Hayes, Andrew F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- (Hu and Bentler 1999) Hu, Li-Tzé, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55.

- (Ioannidou and Konstantikaki 2008) Ioannidou, F., and Vaia Konstantikaki. 2008. Empathy and emotional intelligence: What is it really about?. International Journal of caring sciences, 1(3), 118-123. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47374425.

- (Jordan et al. 2002) Jordan, Peter J., Neal M. Ashkanasy, Charmine Härtel, and Gregory S. Hooper. (2002). Workgroup emotional intelligence: Scale development and relationship to team process effectiveness and goal focus. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 195-214. [CrossRef]

- (Jöreskog & Sörbom 1993) Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 1993. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chica-go, IL: Scientific Software International.

- (Khan et al. 2017) Khan, Nadia Zubair Ahmed, Asma Imran, and Aizza Anwar. 2017. Under the shadow of destructive leadership: Causal effect of job stress on turnover intention of employees in call centers. International Journal of Management Research and Emerging Sciences, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- (Krasikova et al. 2013) Krasikova, Dina V., Stephen G. Green, and James M. LeBreton. 2013. Destructive leadership: A theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. Journal of management, 39(5), 1308-1338. [CrossRef]

- (Khosravi et al. 2020) Khosravi, Pouria, Azadeh Rezvani, and Neal M. Ashkanasy. 2020. Emotional intelligence: A preventive strategy to manage destructive influence of conflict in large scale projects. International Journal of Project Management, 38(1), 36-46. [CrossRef]

- (Kong 2011) Kong, Yingchiong D. 2011. Emotional Intelligence: An Approach for Coping with Toxic Co-workers. In National Conference on Entrepreneurship and Innovation (pp. 154-163).

- (Kong 2011) Kong, Yingchiong D. 2011. Emotional Intelligence: An Approach for Coping with Toxic Co-workers. In National Conference on Entrepreneurship and Innovation (pp. 154-163).

- (Law et al. 2004) Law, Kenneth S., Chi-Sum Wong, and Lynda J. Song. 2004. The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 483–496. [CrossRef]

- (Lee et al. 2012) Lee, Chun-Chang, Sheng-Hsiung Huang, and Chen-Yi Zhao. 2012. A study on factors affecting turnover intention of hotel empolyees. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 2(7), 866-875.

- (Liu, and Onwuegbuzie 2012) Liu, Shujie, and Anthony Onwuegbuzie. 2012. Chinese teachers’ work stress and their turnover intention. International journal of educational research, 53, 160-170.

- (Lubit 2004) Lubit, Roy. 2004. The tyranny of toxic managers: Applying emotional intelligence to deal with difficult personalities. Ivey Business Journal, 68(4), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- (Marôco 2021) Marôco, João. 2021. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics. 8ª ed. ReportNumber: Pêro Pinheiro.

- (Mayer et al. 1997) Mayer, John D., David Caruso, and Peter Salovey. 1997. Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Emotional Intelligence: Theory, Findings, and Implications. [CrossRef]

- (Mayer et al. 2004) Mayer, John D., Peter Salovey, and David R. Caruso. 2004. Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 60, 197-215. [CrossRef]

- (McCallum et al. 1996) McCallum, Robert, Michael Browne, and Hazuki Sugawara. 1996. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structural modelling. Psychol. Methods, 1, 130–149.

- (Mendes 2014) Mendes, Ana Margarida Vieira. 2014. Identificação organizacional, satisfação organizacional e intenção de turnover: estudo com uma amostra do setor das telecomunicações (Master dissertation) Lisbon University. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/18253.

- (Mohammad et al. 2014) Mohammad, Falahat Nejadmahani, Lau Teck Chai, Law Kian Aun, and Melissa W. Migin. 2014. Emotional intelligence and turnover intention. International Journal of Academic Research, 6(4). [CrossRef]

- (Mónico et al. 2019) Mónico, Lisete, Ana Salvador, Nuno Rebelo dos Santos, Leonor Pais, and Carla Semedo. 2019. Lideranças Tóxica e Empoderadora: Estudo de Validação de Medidas em Amostra Portuguesa. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 53, 4, 129-140.

- (Neubauer and Freudenthaler 2005) Neubauer, Aljoscha C., and Heribert H. Freudenthaler. (2005). Models of Emotional Intelligence. In R. Schulze & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), Emotional intelligence: An international handbook (pp. 31–50). Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

- (Peltier 2011) Peltier, Bruce. (2011). Emotional intelligence. The Psychology of Executive Coaching.(pp, 245-274) 2nd Edition.

- (Peng et al. 2019) Peng, Wenya, Dongping Li, Danli Li, Jichao Jia, Yanhui Wang, and Wenqiang Sun. 2019. School disconnectedness and Adolescent Internet Addiction: Mediation by self-esteem and moderation by emotional intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 111-121. [CrossRef]

- (Podsakoff et al. 2003) Podsakoff, Phillip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong Y. Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [CrossRef]

- (Rahman and Nas 2013) Rahman, Wali, and Zekeriya Nas. (2013). Employee development and turnover intention: theory validation. European Journal of Training and Development, 37(6), 564-579.

- Reto, Luís Antero, and Francisco Guilherme Nunes. 1999. Métodos como estratégia de pesquisa: problemas tipo numa investigação. Revista Portuguesa de Gestão, 21-31.

- (Riaz et al. 2018) Riaz, Fahid, Shahzad Naeem, Benish Khanzada, and Kamran Butt. 2018. Impact of emotional intelligence on turnover intention, job performance and organizational citizenship behavior with mediating role of political skill. J. Health Educ. Res. Dev, 6, 250. [CrossRef]

- (Rodrigues et al. 2011) Rodrigues, Nuno, Teresa Rebelo, and João Vasco Coelho. 2011. Adaptação da Escala de Inteligência Emocional de Wong e Law (WLEIS) e análise da sua estrutura factorial e fiabilidade numa amostra portuguesa. Psychologica, 55, 189-207.

- (Salvador 2018) Salvador, Ana Raquel Barreiros. (2018). Liderança tóxica e liderança de empoderamento: relações com a motivação para o trabalho (Master's thesis, Universidade de Évora). http://hdl.handle.net/10174/23427.

- (Schmidt 2008) Schmidt, Andrew A. 2008. Development and validation of the Toxic Leadership Scale University of Maryland, Faculty of the Graduate School, College Park, Geórgia, Estados Unidos da América. Disponível em https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277186751_Development_and_Validation_of_th e_Toxic_Leadership_Scale.

- (Schyns and Schilling 2013) Schyns, Brigite, & Schilling, Jan. 2013. How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 141-144. [CrossRef]

- (Siddiqui and Hassan 2013) Siddiqui, Razi Sultan, and Atif Hassan. 2013. Relationship between emotional intelligence and employees turnover rate in FMCG organizations. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS), 7(1), 198-208. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/188085.

- (Tepper 2000) Tepper, Bennett J. 2000. Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178-180. [CrossRef]

- (Trochim 2000) Trochim, William 2000. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Atomic Dog Publishing.

- (Weberg and Fuller 2019) Weberg, Dan R., and Ryan Fuller. 2019. Toxic leadership: three lessons from complexity science to identify and stop toxic teams. Nurse Leader, 17(1), 22-26. [CrossRef]

- (Wilson-Starks 2003) Wilson-Starks, Karen Y. 2003. Toxic leadership. Retrieved from www.transleadership.com.

- (Wong and Law 2002) Wong, Chi-Sum, and Kenneth Law. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243–274.

- (Zhang 2016) Zhang, Yanjuan. 2016. A review of employee turnover influence factor and countermeasure. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 4(2), 85-91. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).