1. Introduction

Innovative processing methods have provided new solutions to meet sustainability in material development for high-performance applications, like electrochemical processes for energy conversion and storage such as fuel cells and batteries. However, advancements in material research, aimed at innovative properties and tailored functionalities, have led to more complex processing methods with unintended environmental consequences. For instance, the conversion of raw materials for manufacturing energy conversion and storage devices like fuel cells, batteries and solar cells greatly contributes to energy cost and greenhouse gas emissions.[

1,

2] Likewise, production process of typical carbon nanomaterials requires harsh synthetic conditions and fossil fuel-based molecules as precursors which directly harm the environment.[

3] Exacerbating the problem, these materials possess properties that are detrimental to the environment and resistant to biodegradation, resulting in long-term ecological impact. Commercial membranes such as Nafion, employed in fuel cells, highlight this concern, as they are not only prohibitively expensive but also involve the utilization of harmful substances during production.[

4] Right now, the development of new membrane materials as replacement or substitute for the polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) will determine the successful commercialization of fuel cells and adoption by the industry.

The resurgence of the needs for alternative material to synthetic ones created more interests for many researchers in recent years to focus on the goal of achieving sustainable materials. Sustainability is now being considered as one of the primary criteria to ensure continued access to important materials for many applications in the coming years. The increasing emphasis on biodegradability, eco-friendliness, renewability, and other "green" material attributes is fueling a renaissance in the development and utilization of bio-based materials.[

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] Green materials which are often derived from plants meet the requirements for sustainability and renewability compared to conventional engineering materials which are non-renewable and finite resources.[

10] The trend right now is to re-purpose renewable starting materials from biomass such as agricultural and industrial wastes which could contribute to developing materials that benefit the environment.[

11,

12,

13] According to Worthington et al. [

14], starting materials derived from renewable biomass compared to synthetic materials will definitely provide a way to contribute to the sustainability outlook as well as the environmental benefit of using these feedstocks. Biomass as feedstocks have the advantages of being bountiful, renewable, environment-friendly and low cost.[

15] The application of nanotechnologies makes it even more possible right now for the conversion of agro-industrial by-products into novel and useful high-value adding products.[

16] Biomass is a primary source of cellulose which is the most abundant natural polymer.[

17] This type of material is considered as excellent starting material for synthesis of nano-structured material having broad diversity in macrostructures which could produce unique structures.[

18] The utilization of these materials will also provide new opportunities for a greener and a facile synthesis method of producing materials that could have vast applications.

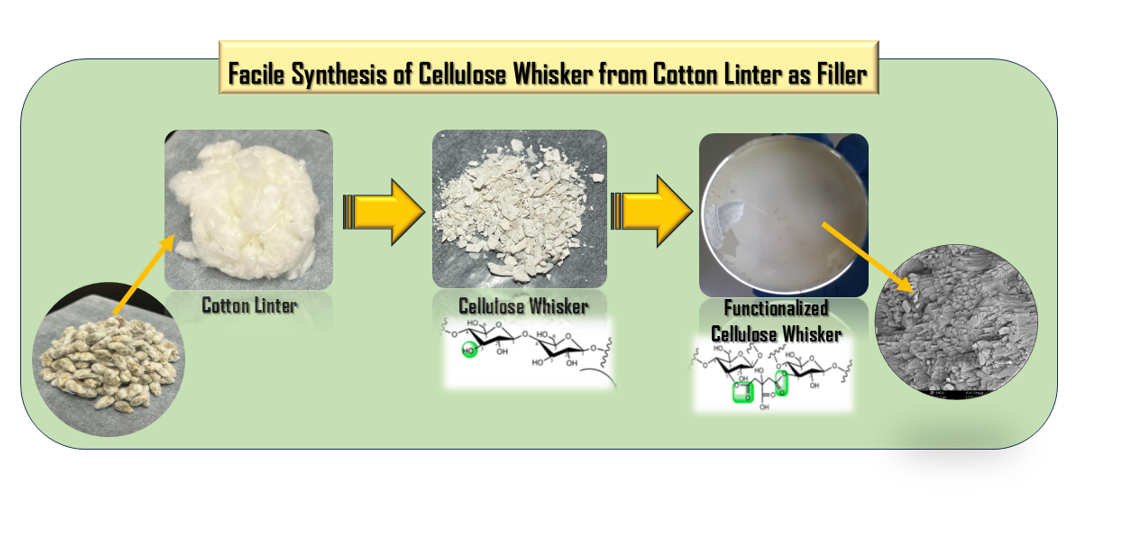

In this study, cotton wastes or most often referred to as cotton linters were utilized as starting materials for the facile synthesis of cellulose whisker or also called cellulose nanocrystals as filler material for the development of hybrid membrane. Cotton linters are the short fibers that remained unextracted in the cotton seed coat which are not used for textile processing.[

19] These short fibers, composed primarily of cellulose without lignin, simplify the modification process for conversion and functionalization to produce fillers. Most filler materials have limited functions capable of augmenting only the modulus, surface area, and surface chemical composition of polymers, without conferring enhancements to mechanical strength.[

20] But in this study, the cotton cellulose-derived cellulose whisker will be an active material that contributes to the incorporation of functional groups as proton transfer agent in the hybrid membrane for fuel cell application. A further advantage of using cotton linter as a starting material is its green nature which improves the sustainability aspect of the hybrid membrane. Furthermore, the facile synthesis method for cellulose whisker significantly minimizes the use of chemical reagents and waste generation, thereby conserving resources. Re-purposing the cotton wastes as raw materials is an important factor in the selection of a simpler processing method with the derived material in mind as the final output thereby, optimizing the processing conditions. On a broader scale, by utilizing sustainable material such as cotton linter in products and processes, it can significantly mitigate environmental impact by reducing the carbon footprint and energy consumption throughout the entire product lifecycle. [

21]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Cotton linters were provided by the Philippine Fiber Industry Development Authority (PhilFIDA) of the Department of Agriculture (DA) and Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST). Concentrated H2SO4 (RCI Labscan, AR 98%), sodium hydroxide (micropearls RCI Labscan, AR 99%) and citric acid (RCI Labscan, AR grade) were purchased from Belman Laboratories and Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (ACS grade, Echo, 99.9%), and Tetrahydrofuran (THF) (inhibitor free, high purity, Tedia, 99.8%) were purchased from Theo-pam Trading Corp., and were used as received.

2.2. Alkali Treatment

The alkali treatment method was based on the procedure from the previous report of Zheng et al., [

22] with minor adaptations. The desired amount of cotton wastes as feedstock were weighed based on the statistical design of experiment. Then, the NaOH aqueous solutions were prepared based on the concentrations in the experimental design. The cotton linters were added in the alkali solution using a solid to liquid ratio of 1:33 (cotton linter/NaOH solution) and heated at 60°C for 6 h under constant stirring at fixed speed of 200-300 rpm. Filter and then, wash the extracted cellulose repeatedly, with distilled water until the pH is near neutral. Dry the cellulose material in the drying oven at 60

oC until weight becomes constant to ensure that moisture content was removed.

2.3. Acid Hydrolysis

Acid hydrolysis using sulfuric acid is the simplest approach for a highly effective cellulose whisker (CW) preparation.[

16] The procedure for acid hydrolysis was described in the previous reports [

23,

24,

25] with modifications. The desired amount of dried cellulose was weighed. Then, the cellulose was added in H

2SO

4 solution using a solid to liquid ratio of 1:10 (cellulose/acid solution) at 45°C under constant stirring speed of 200 rpm for the desired reaction time (45 min and 60 min) and acid concentration (55 wt% and 60 wt%) based on the statistical experimental design. Filter the solid materials from the hydrolyzed colloidal suspension separating the spent acid portion. Wash the material with deionized (DI) water repeatedly, using refrigerated microcentrifuge (DLab, D1254R, China) at 10,000 rpm and temperature of 10

oC for 5 min until the pH is near neutral (constant between 5-6). Homogenize the neutralized colloidal suspension by using ultrasonic homogenizer (Stuart, SHM3, USA) at 10,000 rpm for 30 min. Dry the cellulose whiskers in the oven (Jeio Tech, ON-02G, Korea) at 60

oC for 6-8 h or until weight becomes constant to completely removed moisture. Store the samples in air tight container prior to further processing.

2.4. Functionalization

The desired amount of cellulose whiskers (CW) were weighed. DI water was added to the cellulose whisker at 5 wt% concentration and homogenize for 15 min at room temperature (RT) under constant stirring (450 rpm). The CW suspension was combined with citric acid solution (CA) (5 wt%) at CW to CA ratio of 50:50. Then, the CW/CA blended solution was homogenized using ultrasonic homogenizer (Stuart, SHM3, USA) at 5000 rpm for 5 min. The blended solution was placed in a petri dish for drying in the oven (Jeio Tech, ON-02G, Korea) at 35 oC until completely dry. Then additional thermal treatment for 10 min at 120 oC for curing and crosslinking of the cellulose whiskers. After curing, the CW was washed until no residuals of acid were detected when pH becomes constant (pH ≥ 5 ). The CW was dried in the oven at 35 oC until completely dried. The CW was stored for utilization in the hybrid membrane fabrication.

2.5. Characterization of Cellulose and Cellulose Whisker

The cellulose and cellulose whiskers (CW) produced were characterized for their structural compositions using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Shimadzu, IR Tracer-100, Kyoto, Japan) with Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory to confirm the functional groups present in the cellulose material as well as to correlate the peaks associated with amorphous and crystalline structures to the total crystallinity index (TCI) of the synthesized cellulose materials.

The crystallinity index (CrI) was further validated by performing X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis on the samples after converting the cotton cellulose into cellulose whiskers (CW). The diffractograms were recorded using diffractometer (Shimadzu, LabX XRD-6000, Kyoto, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation, a voltage of 40kV and a current of 30 mA. The scanning range was from 2Ɵ = 5ᵒ to 30ᵒ at a scanning speed of 1ᵒ per minute. In addition to these properties, the effects of process variables were analyzed for the recovery of cellulose and cellulose whisker in terms of % yield.

Electrochemical capacity indicators such as ion exchange capacity (IEC) by back-titration method and surface wettability were measured by the contact angle of the sessile drops of deionized water (volume 5μl) on the CW surface using a contact angle measurement device, Optical Tensiometer (Attension Theta Lite, AAU112015, Sweden) equipped with a camera (2068 FPS and performs precise analyses with 1280 x 1024 pixel resolution) and drop shape analysis using OneAttension software. Five measurements were done for each sample of the cellulose whiskers as indicators of its suitability as polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM). The morphology and microstructure of the cellulose whiskers and functionalized cellulose whiskers were analyzed using SEM (Thermo Scientific™, Phenom™ XL G2 Desktop, USA) to determine the geometric aspect ratio of the material using Image J software (version 7.0.0). The tensile strength test was performed using a UTM (Shimadzu, AGS-50NX, Japan) following the standard method D882-02. Four (4) sample replicates for each hybrid membrane were cut into dumbbell shape samples of uniform width, 10 mm, placed in the grips of the machine and tested at a strain rate of 5 mm/min.

2.6. Statistical Experimental Design and Analysis

Statistical experimental design was utilized throughout the study to assess the influence of process variables and their interactions on the observed responses. For the synthesis of cellulose from cotton wastes using alkali treatment, the experimental design used was “one-factor at a time” with concentration (wt %) of NaOH as the independent variable and resulting structural property and yield as response variables. The experimental design is summarized in

Table 1.

In the further synthesis of cellulose whisker via acid hydrolysis, the statistical design of experiment employed was 22 full factorials with acid concentration (wt %) and reaction time (min) as independent variables while crystallinity and structural composition as well as yield were the dependent variables. The statistical design of experiment is shown in

Table 2.

To handle potential sources of error, the experiments were implemented in two (2) independent replicates and in completely randomized block design. The experimental runs were conducted in accordance with the randomized sequence of treatments generated using Design Expert software (version 7.0.0) with blocking design.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Material Selection and Profiling of Biomass Wastes

Material selection and profiling of starting materials were carried out prior to synthesis to assess the suitability of the biomass waste and the potential for modification of processing methods to reduce the needed resources to reduce cost as well as improve material sustainability. The selection of material from commonly available biomass sources were conducted by testing the chemical compositions such as cellulose, lignin and moisture content. Among the samples of common biomass wastes tested, the cellulose content of the seed fibers particularly, cotton, have the highest cellulose content of around 95% - 98%. Moreover, cotton lint and linter both have no lignin content which made extraction and purification of cellulose as starting material way easier and simpler for cotton wastes without the need for delignification process. The different compositions of the biomass wastes are shown in

Table 3.

In addition, material profiling was conducted to understand the properties’ applicability for target application. The criteria used for the selection of the starting material were based on the potential conductive property, material sustainability, and as source of renewable polymer. Based on these criteria, the biomass-derived starting material more suitable for the facile synthesis of filler was the cellulose from cotton linter mainly, because of its composition and its inherent properties suitable for further processing and functionalization. More importantly, it is organic and low cost.

3.2. Effects of Alkali Treatment on Cellulose Recovery and Conversion

Alkali treatment as the pre-treatment method for cotton linter was able to produced cellulose material using NaOH as the alkali reagent. According to Teo and Wahab, [

16] NaOH solution is considered as all-time choice for alkali because it is cost-effective and the use of NaOH alkali reagent is considered as “greener” procedure as compared to more toxic and hazardous acid pre-treatment. It is also proven from reports that NaOH treatment method is the most effective technique in removing non-cellulosic polymers which is composed mainly of amorphous heteropolymers that are insoluble to water. [

26,

27] According to Klijun et al., [

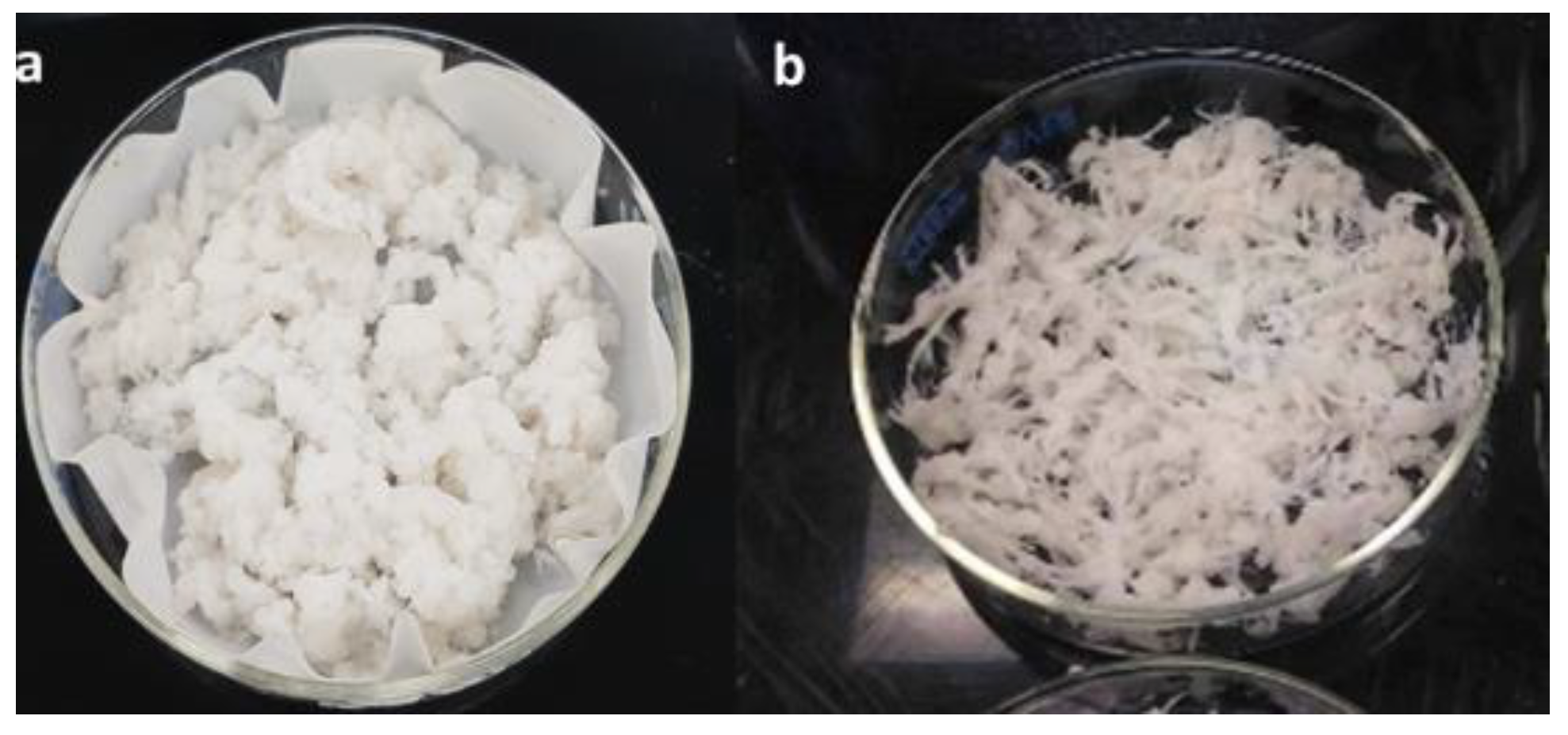

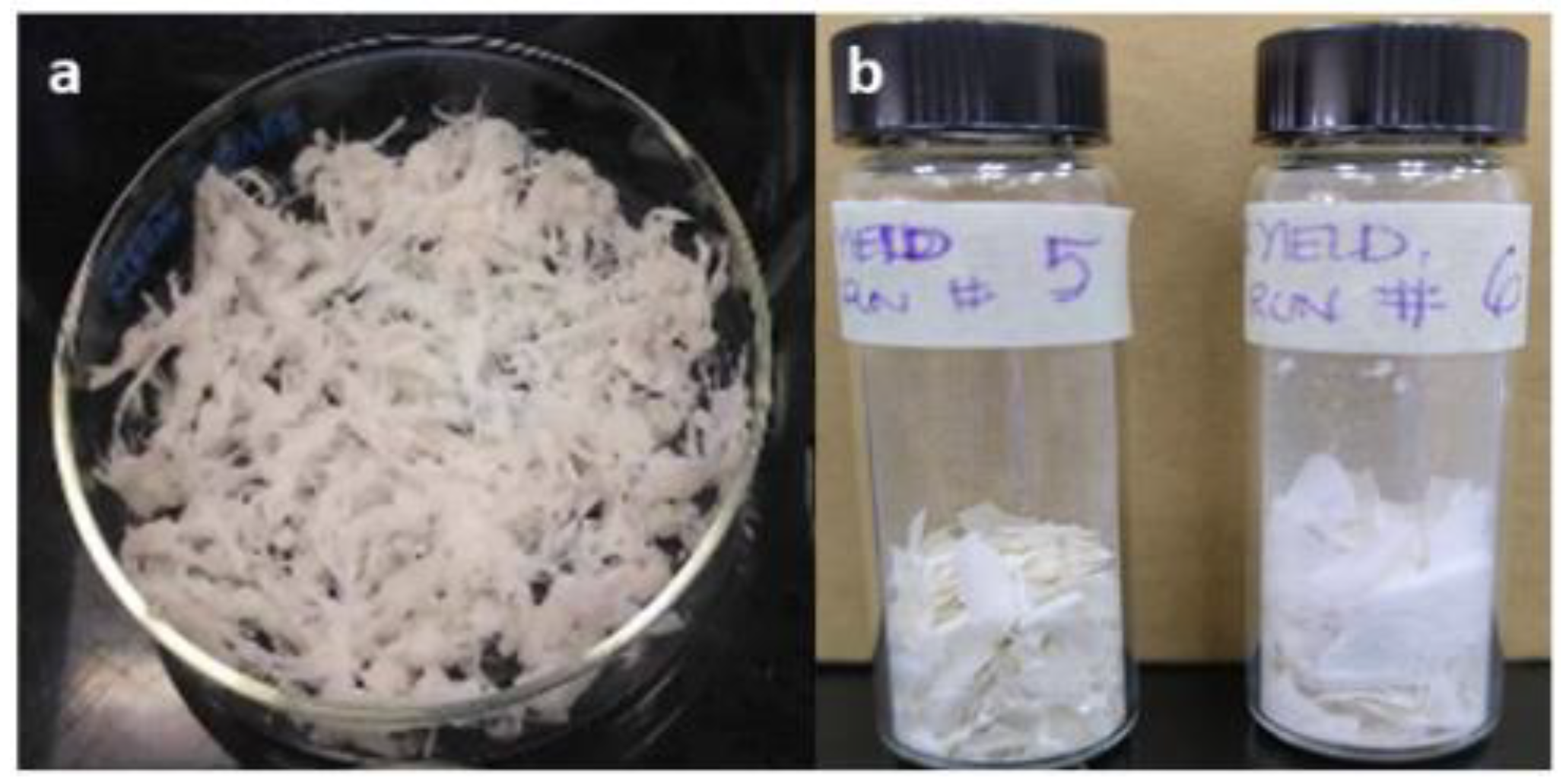

28] conducting alkali treatment at higher alkali concentration produced the desired cellulose II polymers from the breakdown of intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The important consideration in the synthesis of the cotton cellulose was the % yield obtained with varying concentration of NaOH (5 to 15 wt%). The cotton cellulose obtained from the alkali treatment is shown in

Figure 1.

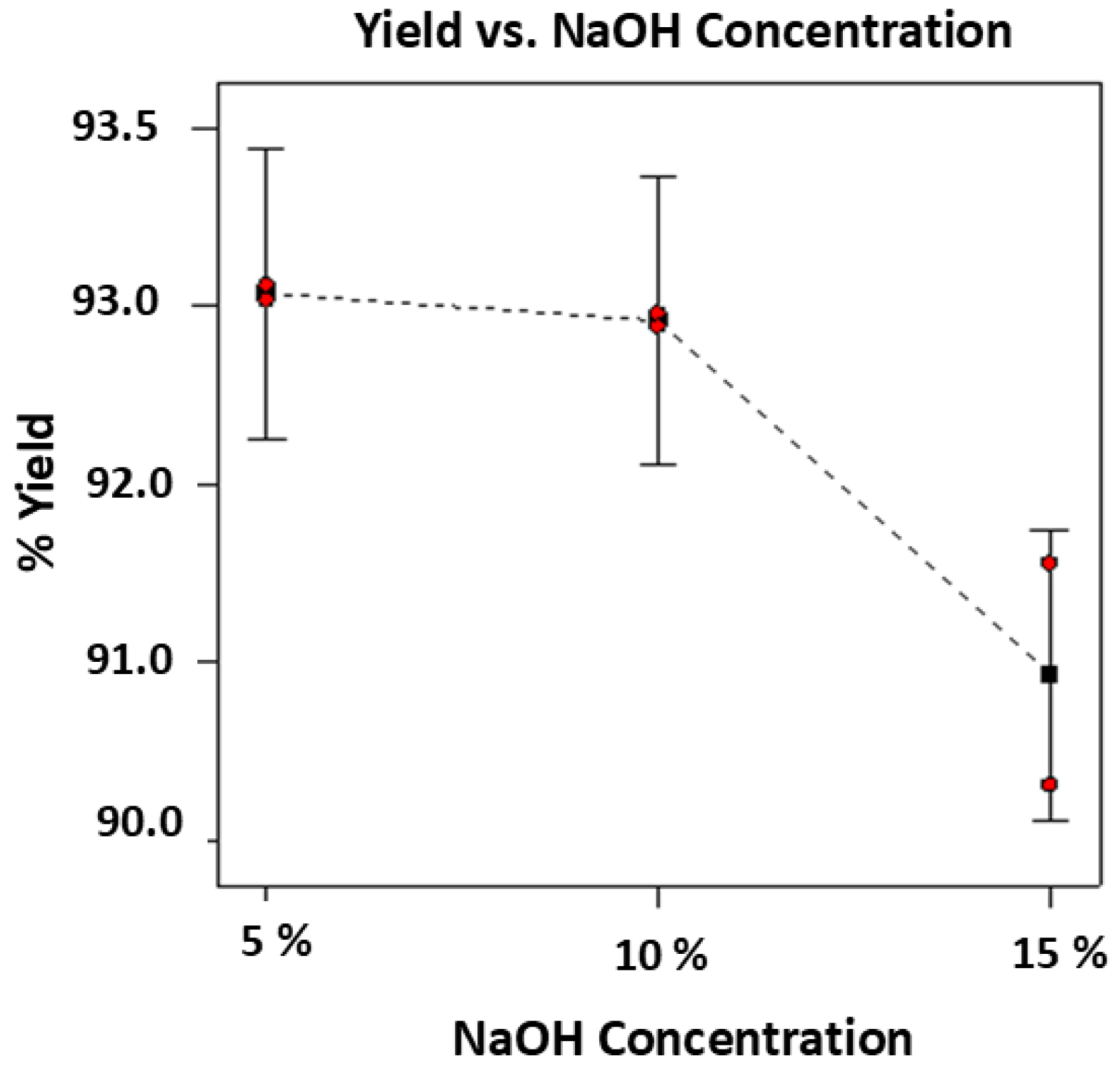

Based on the experimental runs, the higher concentration of NaOH at 15% showed an average yield of 90.97% which was lower compared to 5% and 10% with average yields of 92.74% and 92.61%, respectively. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

The statistical analysis of the significant effects of varying the NaOH concentration was carried out by one-way ANOVA (with replicates). Based on the analysis, there was a significant effect of the NaOH concentration on the % yield with F-value (10.95) greater than the F-critical (9.55) at p-value of 0.042 which is less than 0.05. The graphical analysis of the two variables as shown in

Figure 2, showed that at higher concentration of 15% NaOH, the average yield of 90.97% was the lowest yield. Thus, based on these results, the higher the concentration of NaOH, the more purified the cellulose materials extracted after alkali treatment which removed almost all unwanted components retaining only the more purified and the desired cellulose II polymers.

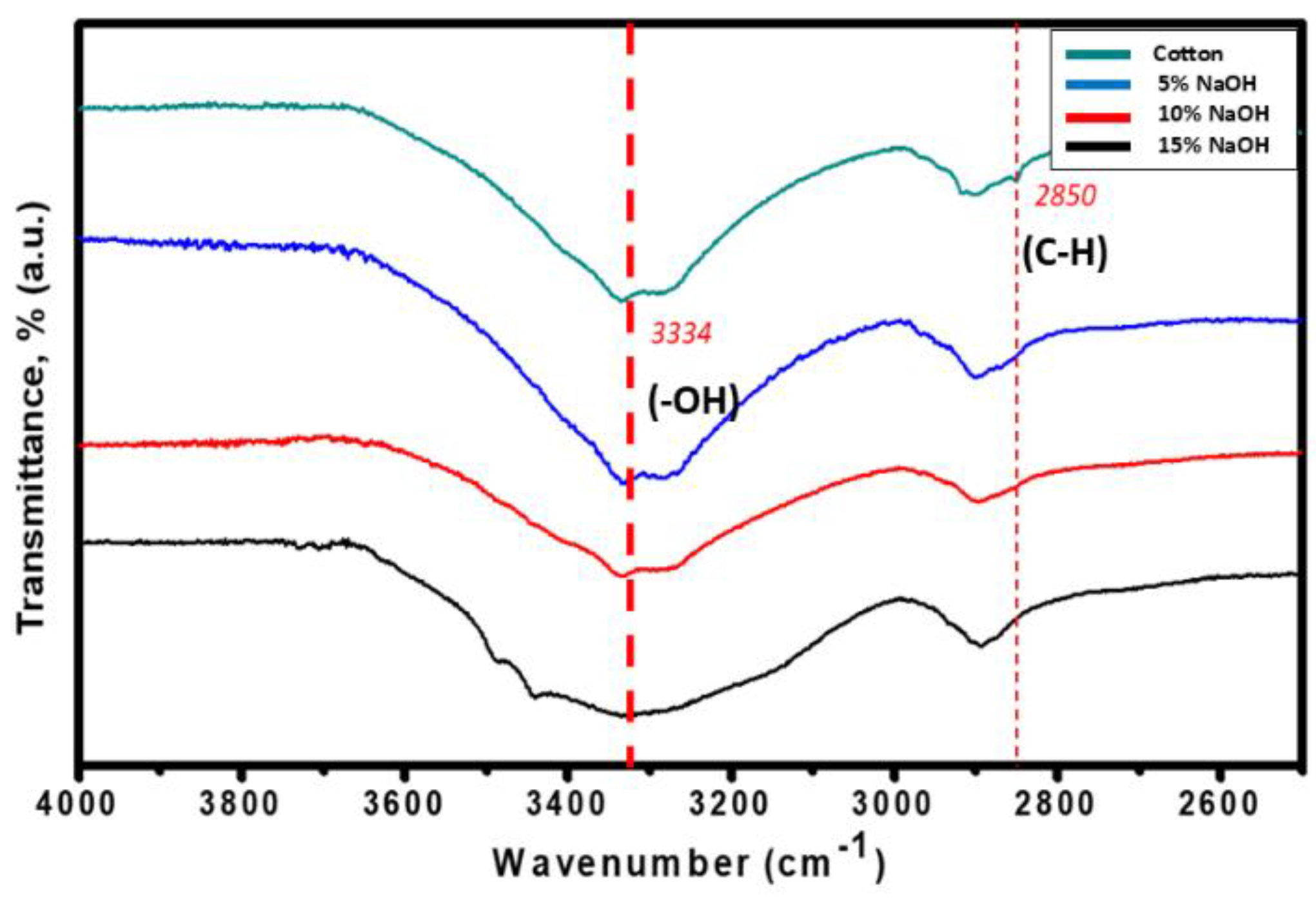

The structural composition of the cotton cellulose compared to the starting material was confirmed by the ATR-FTIR spectra. Based on

Figure 3, the presence of the broad band at 3200-3500 cm

-1 determined the O-H group of the cellulose. [

29] The broaden it gets the more visible the cellulose is. All spectra exhibited peaks at 2800-3000 cm

-1 which indicated the characteristic of C-H stretching vibration consisting of cellulose components. [

29] Thus, the occurrence in the reduction of intensity at 2850 cm

-1 showed that alkali treatment with 15% NaOH concentration was very effective in eliminating undesired impurities and unwanted non-cellulosic components.

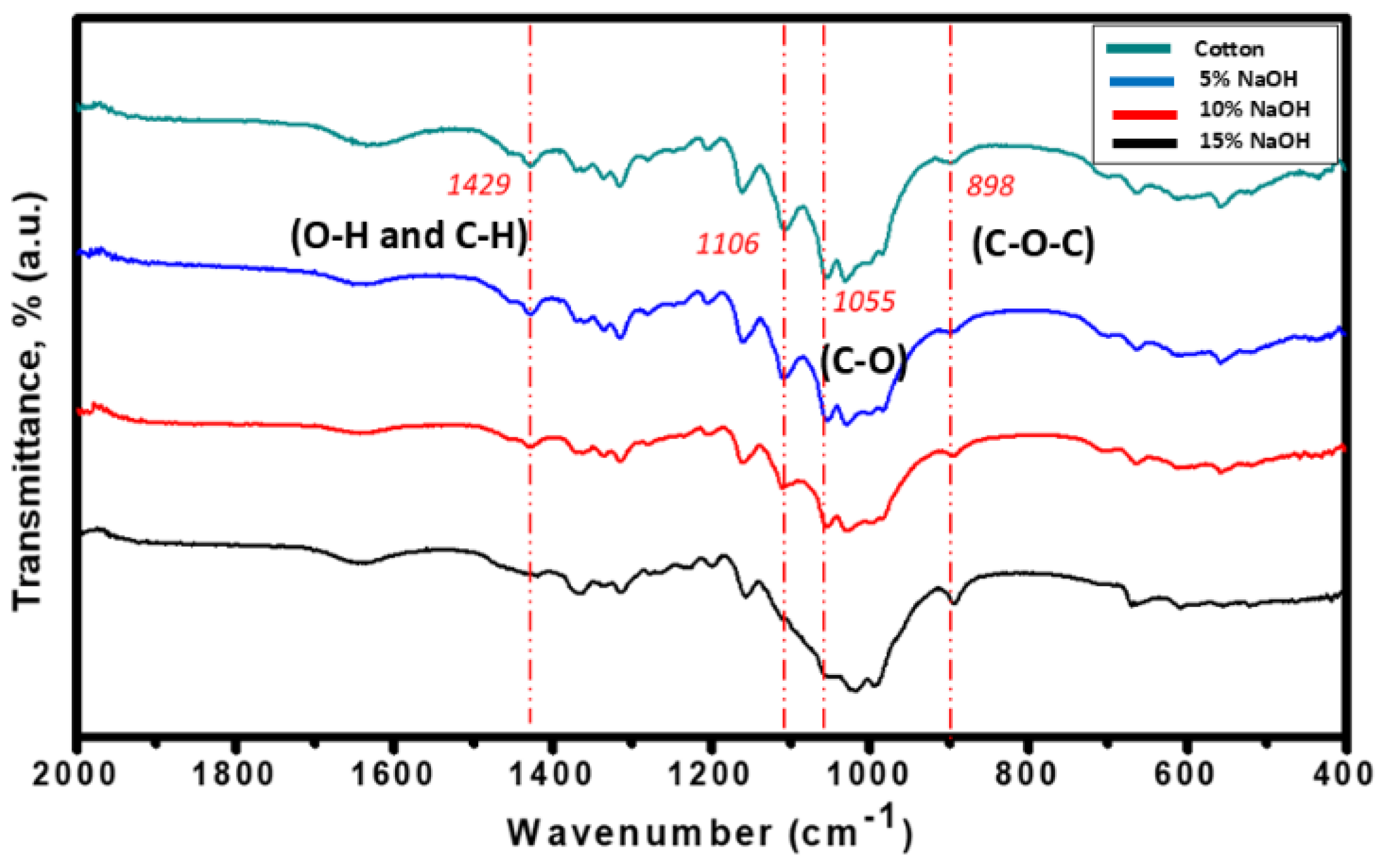

Further analysis of the IR spectra shown in

Figure 4, revealed the peak at 1429 cm

-1 related to stretching of the C-H group and the bending of the O-H or C-H group of the crystalline region. [

30,

31] The C-O stretching at 1050-1120 cm

-1 was a confirmation of the presence of hemicellulose. [

32] The presence of the band at 898 cm

-1 assigned to C–O–C stretching at β-(1-4)-glycosidic linkages are amorphous regions. [

30,

31] Based on these IR spectra analyses for the alkali-treated cellulose with 15% NaOH concentration, the lignin, hemicellulose and amorphous functional groups have all disappeared while the cellulose II polymers’ functional groups became more evident which achieved the desired composition of the material as purified cotton cellulose.

3.3. Effects of Acid Hydrolysis on Cellulose Whisker Conversion

The simplest approach for a highly effective cellulose whisker preparation from cellulose is carried out by acid hydrolysis via the mechanism of hydrolytic cleavage of glycosidic bonds of the disordered regions in the polymer. [

16] Important parameters that were optimized in acid hydrolysis of cellulose are type and concentration of acid, reaction time and temperature. Sulfuric acid hydrolysis is the most widely used method, offering the shortest reaction times. [

33] It yields nanocellulose with the highest crystallinity index and forms stable colloidal suspensions due to the esterification of hydroxyl groups by sulfate ions. [

33] Acid hydrolysis generally necessitates 60-65% sulfuric acid, temperatures between 40-50°C, and reaction times of 30-60 minutes, but the excessive degradation under these conditions leads to unacceptably low yields (less than 30 wt%). [

34] One of the possible solutions is to optimize the process conditions where the yield of cellulose whiskers could be significantly improved by decreasing the concentration of sulfuric acid and prolonging reaction time. [

35] Although temperature is another important factor, conventionally, dilute acid hydrolysis operates at low temperature (close to 40 °C). [

36] For the main reason that the effect of the combination of high temperatures and diluted acid solutions which can significantly increase corrosion rates, resulting in higher operational and maintenance expenses. [

37] This study opted to use process conditions with diluted H

2SO

4 concentration (55-60 wt%) and longer reaction time (45-60 min) but at lower temperature of 45

oC. The outputs of the experimental runs for the % yield are shown in

Table 5. The highest yield of 92% was recorded for the treatment combination of 55% acid concentration and 60 min reaction time while the lowest yield was reported for the combination of 60% acid concentration and 45 min reaction time. This validated the previous report that at lower concentration of acid (55%) and longer reaction time (60 min) were better in producing higher yield of cellulose whiskers. The cellulose whisker produced from cotton cellulose is shown in

Figure 5.

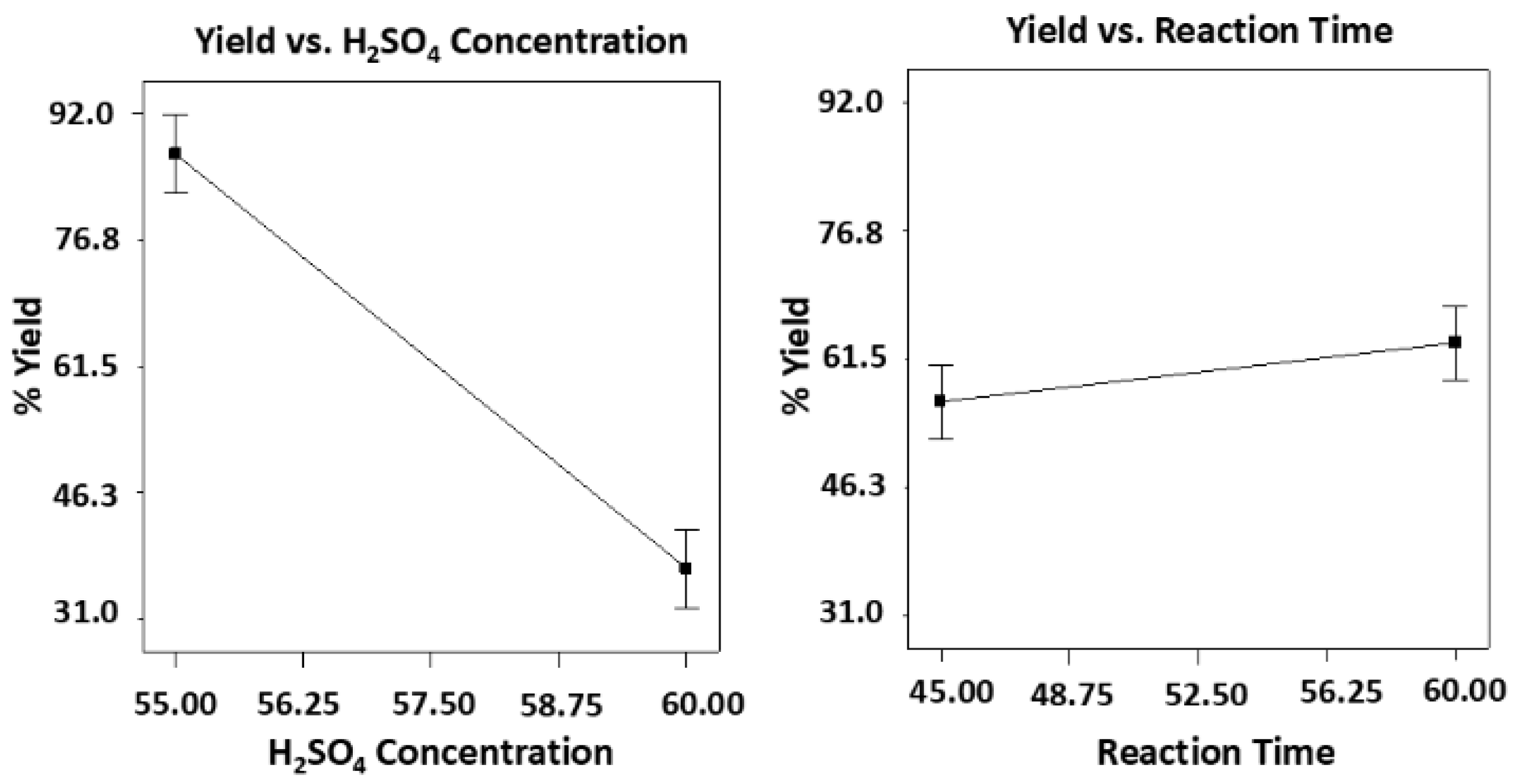

The significant effects of the individual factors such as acid concentration (55% and 60%) and reaction time (45 min and 60 min) on % yield was analyzed using two-way ANOVA (with replicates). Based on the results, acid concentration as an individual factor has a significant effect on yield (p-value < 0.0001) while the reaction time had no significant effect on yield (p-value = 0.095). For the interactions of both factors, there was no significant effect. Overall, the model for the correlation between the two factors and yield was significant with p-value of less than 0.0001.

To further validate the results, graphical analysis revealed the extent of the effects of the two variables on the % yield as shown in

Figure 6. The increased in acid concentration from 55% to 60% showed a sharp decrease in yield from 77-92% to 31-43%. For the reaction time between 45 to 60 min, there was no significant change in yield from 30.5 to 39% at 60% acid concentration and from 82 to 88% at 55% acid concentration. Thus, acid concentration of 55% had the most effect on yield with reaction time either 45 min or 60 min.

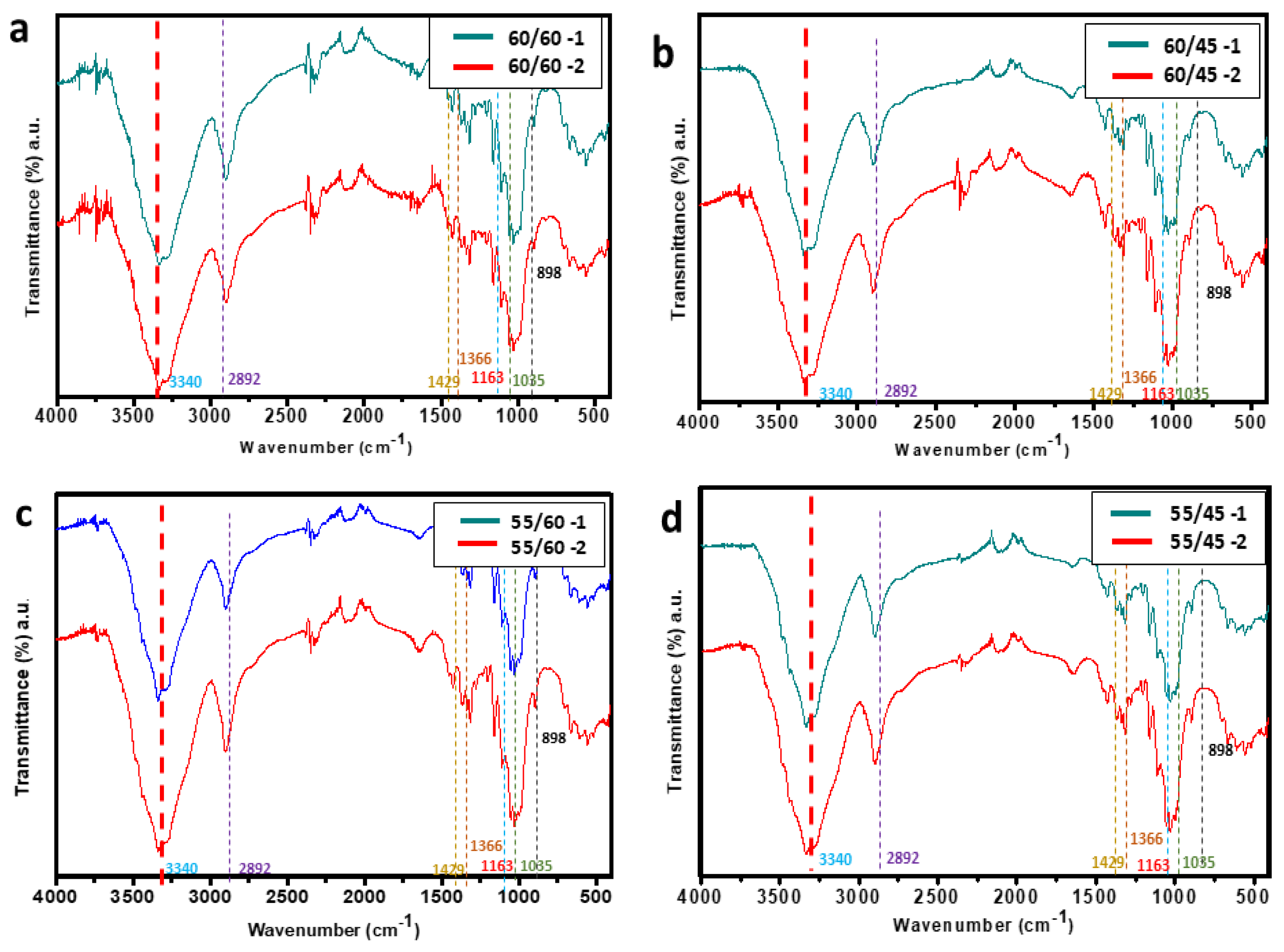

3.4. Effects of Acid Hydrolysis on Structural Composition of CW

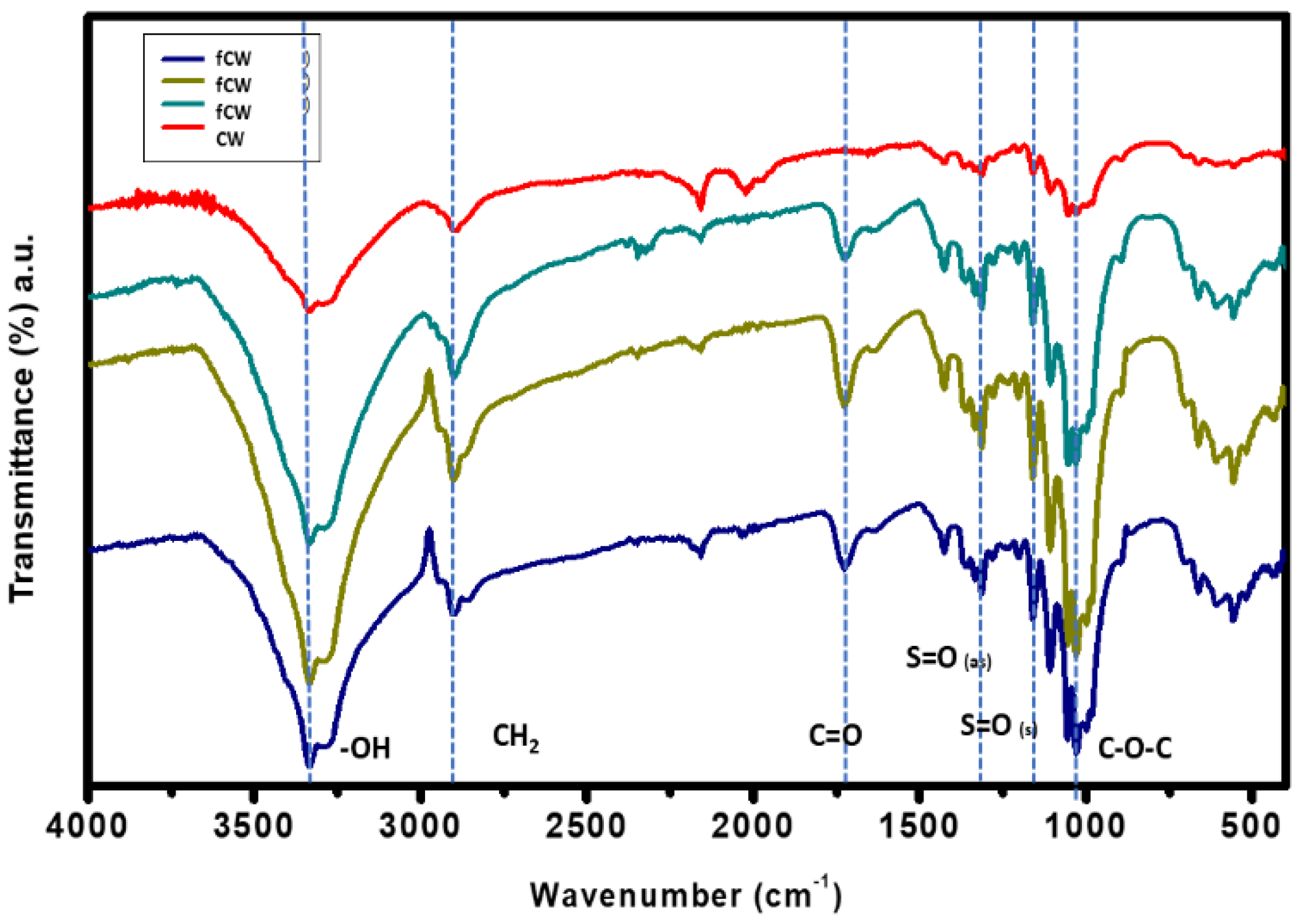

The structural composition of the cellulose whiskers synthesized by acid hydrolysis from cellulose was confirmed using ATR-FTIR. Based on the results shown in

Figure 7, the characteristic peaks at 1163 cm

-1 and 1035 cm

-1 were both present which were attributed to the SO

2 symmetric and asymmetric stretching which are both primary indicators of effective conversion of cellulose into CW. Hydrolysis of cellulose with sulfuric acid introduces anionic sulfate groups onto CWs, resulting in a stable, negatively charged aqueous suspension. [

38,

39] These sulfate groups endowed negative charge on the CWs creating an electrostatic repulsion that enhances their dispersion in water. [

33] These charges come from the reaction between sulfuric acid and surface hydroxyl groups of cellulose and induce repulsive forces between negatively charged CW leading to colloidal stability and dispersion in water. [

40] Other prominent peaks of CW at wavenumbers of 1429, 1366 and 898 cm

-1 were associated with C-H

2 rocking, C-O stretching and C-H bending, respectively. The peak associated with 2892 cm

-1 is a confirmation of the presence of cellulose II polymers from the glycosidic linkages.

Cellulose is the predominant structural polymer within plant cell walls, responsible for their exceptional strength and stiffness. [

41] This arises from the extensive network of hydrogen bonds, both intra- and intermolecularly, which enables the formation of crystalline structures characterized by parallel-aligned, elongated chains. [

41] In hybrid membrane the polymer-filler composite forms the two-phased material in which the polymer is amplified by the presence of the filler material which magnifies the polymer’s effectiveness in relation to mechanical strength and durability. [

42,

43] Total crystallinity index (TCI) of cellulose whisker was calculated using Segal’s method based on the peaks associated with the crystalline components of the cellulose whiskers obtained from the ATR-FTIR spectra. The evaluation involved applying baseline correction to normalize the absorbance spectra and then, determining the relevant peak heights (A) of the crystalline components at specific wavelengths to calculate the TCI. Based on the results of TCI estimation, the acid concentration of 55% to 60% and reaction time of 45 min to 60 min estimated the TCI ranged from 65.67% to 77.61%. The highest TCI of 77.61% was reported for the treatment combination of 60% acid concentration and 60 min reaction time while the lowest TCI of 65.67% was recorded for the treatment combination of 55% acid concentration and 45 min reaction time.

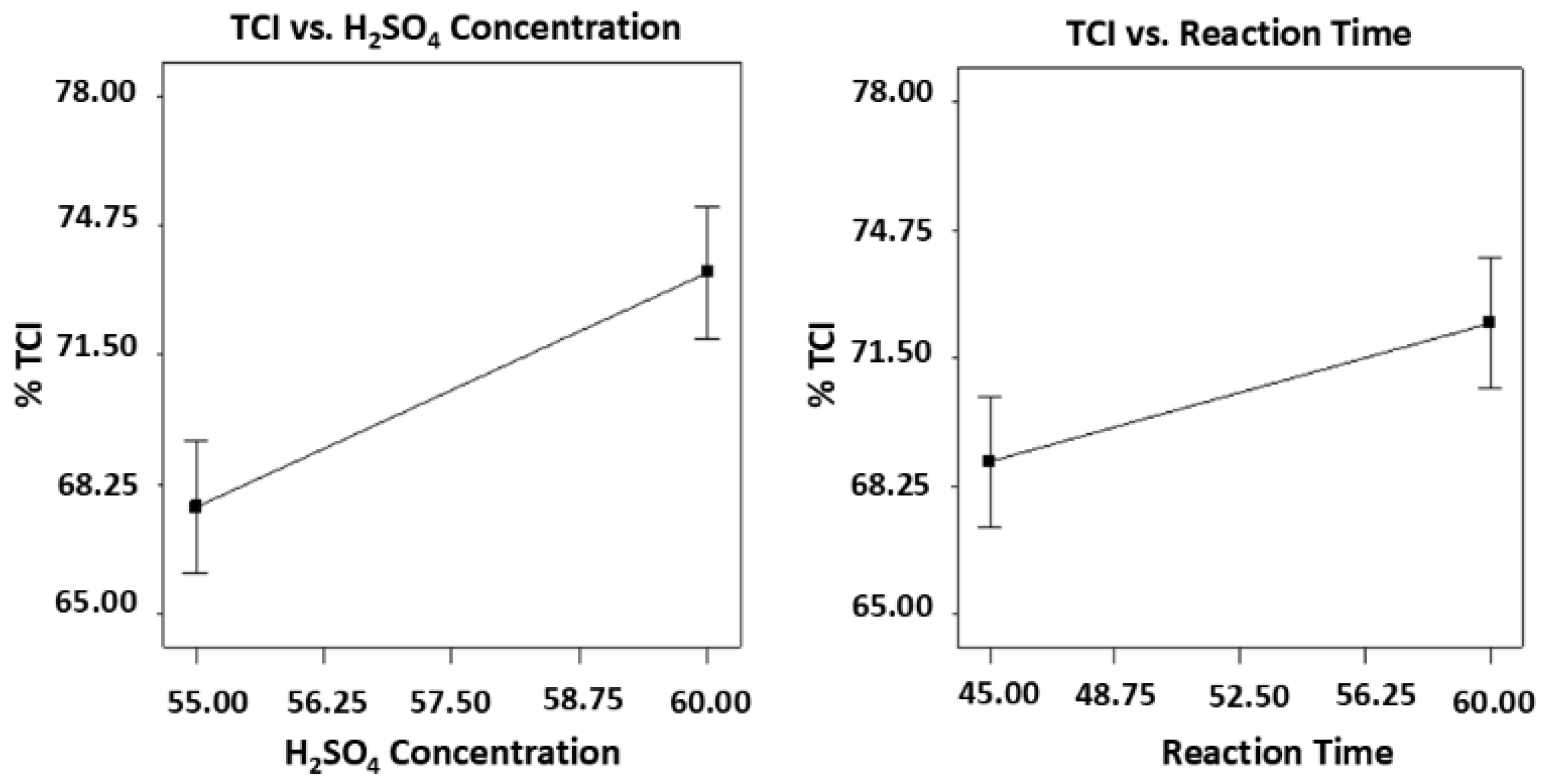

The results were further analyzed using two-way ANOVA (with replicates) revealing that both acid concentration (p-value = 0.0059) and reaction time (p-value = 0.0417) were significant factors that affects the TCI. Overall, the model for the correlation between the two factors and TCI was also significant with p-value of 0.0087.

Based on the graphical statistics shown in

Figure 8, the results were validated where both acid concentration and reaction time have significant effects on TCI. Increasing both factors resulted to a significant increase in the % TCI of the cellulose whisker as indicated by steep trend line for both factors.

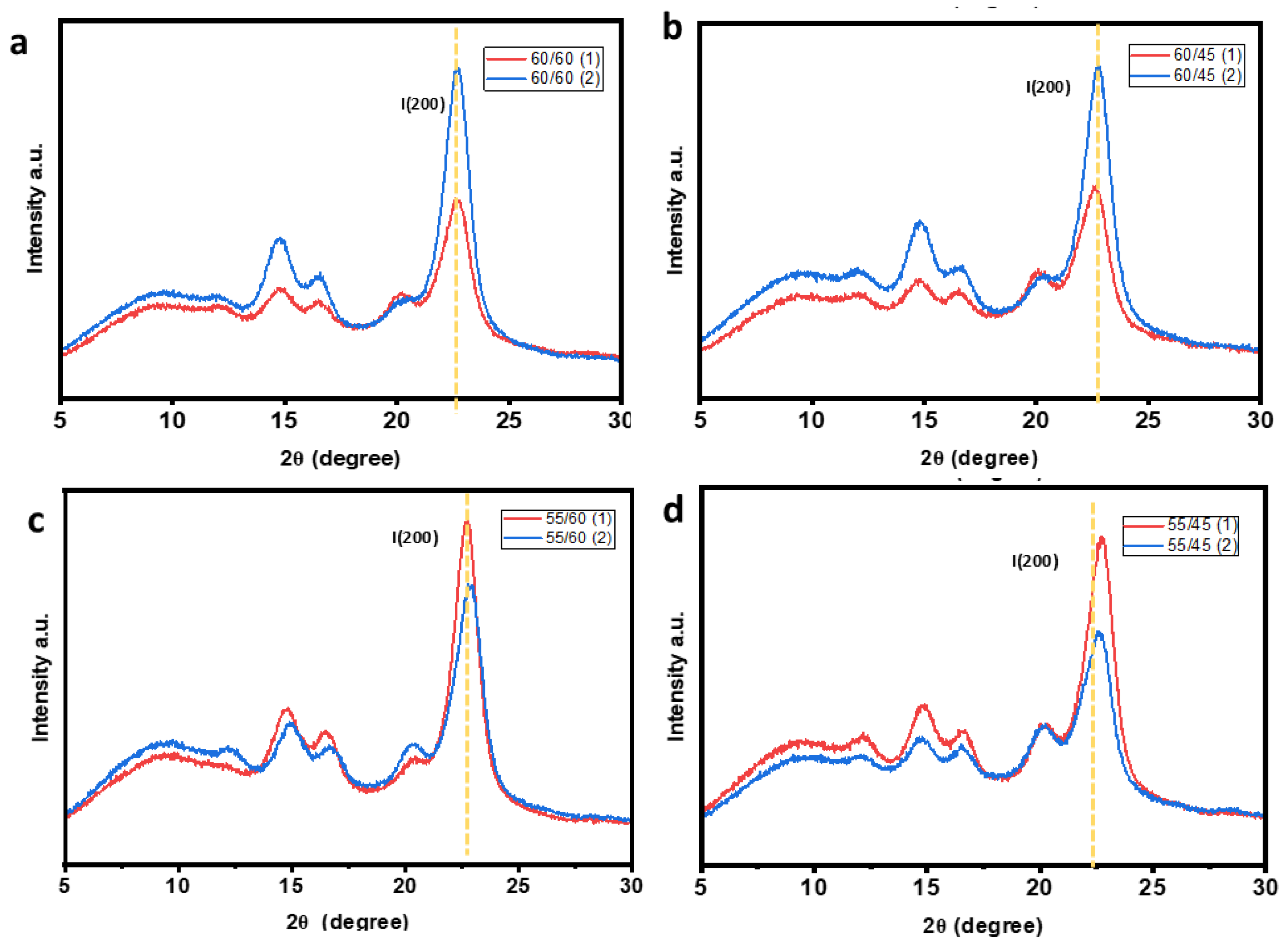

The crystallinity index (CrI) was also evaluated using XRD analysis to compare and confirm the crystallinity of the CW based on the ATR-FTIR results. The XRD diffractograms are shown in

Figure 9. Crystallinity index (CrI) was estimated based on the XRD diffractogram of the CWs which showed a sharp peak at 2ɵ between 22-23

o confirming the presence of the cellulose type II crystals in the CWs. The CrI was calculated based on the I

200 maximum intensity which represents the crystalline material, while I

am represents maximum intensity of the amorphous material.

Comparing the calculated values of TCI and CrI summarized in

Table 6, it showed that the two results have no significant differences with low deviations in the data range. Thus, the crystallinity index (CrI) obtained from the same samples using XRD (Segal’s method) were statistically the same with the TCI ranging from 69.5-72.4%. Thus, the CW synthesized via acid hydrolysis has considerably high crystallinity compared to previous study.[

22] This validated that cellulose whisker can have a perfect crystalline structure (about 65%–95% crystallinities) which is high strength, rigidity and higher modulus. [

39,

44,

45,

46]

3.5. Effects of Functionalization on Structure, Surface Wettability and Morphology of CW

The functionalization of the CW was initially confirmed by the modification of structural composition using ATR-FTIR as shown in

Figure 10. The functionalized CW exhibited a new peak at 1726 cm

-1 in the three trial runs which were assigned to the C=O carbonyl stretching vibration of formed ester groups and unreacted carboxylic groups. [

47] It was reported in previous studies that the carbonyl stretching was from the ester-linkages which indicates cross-linked CW. [

48,

49] With the modification in structure of the CW, the SO

2 symmetric and asymmetric stretching which are important functional groups for the functionalized CW as fillers were not compromised during the functionalization treatment. Other peaks associated with the structure of the CW such as C-O-H and C-O-C bonds as well as -OH stretching remained in the chemical structure of the CW.

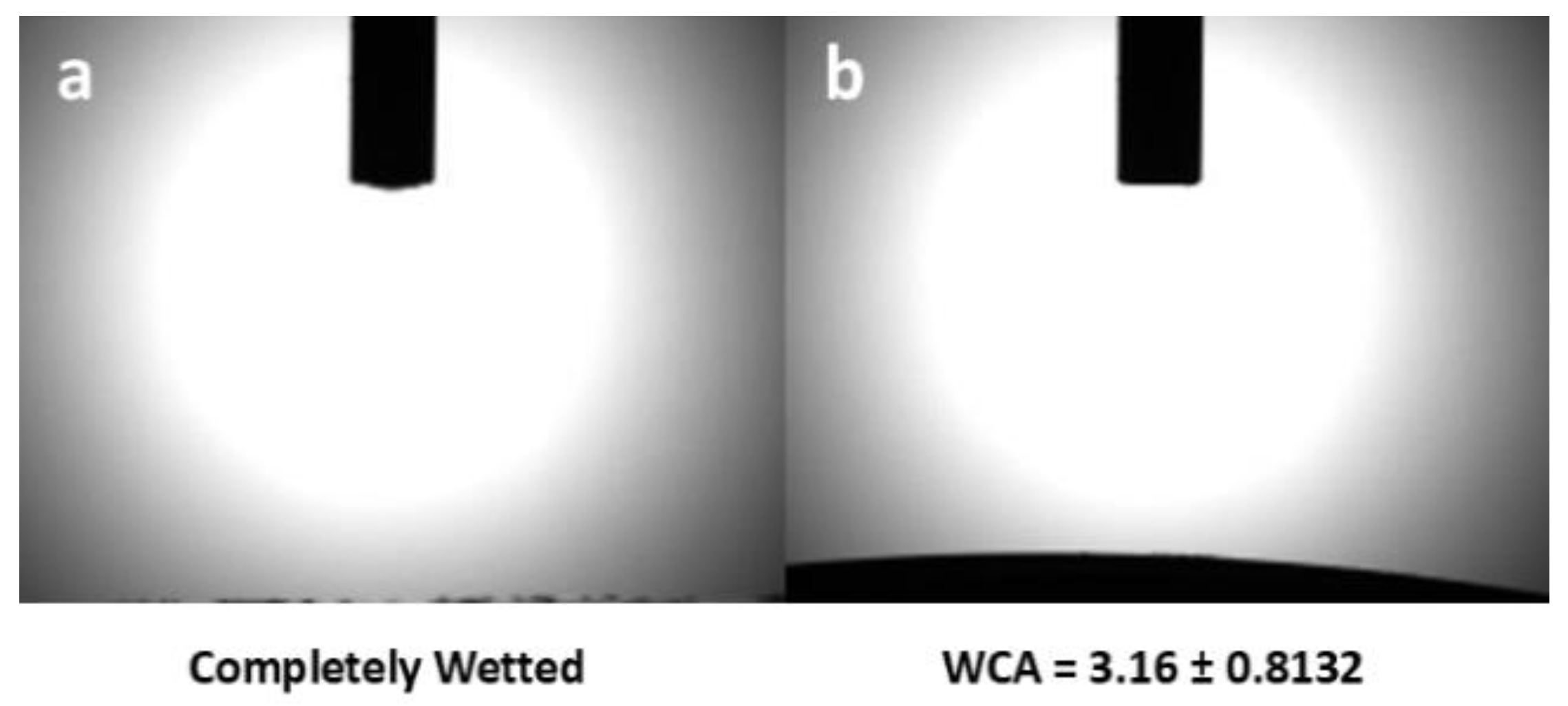

One important property of the CW suitable for PEM is its surface wettability. After functionalization, the surface chemistry of CW remained highly hydrophilic based on the water contact angle (WCA). As shown in

Figure 11, the resulting water contact angle showed completely wetted surface of CW and a water contact angle of 3.16

o after functionalization. These results means that CWs have highly hydrophilic surface which indicates good water transport property.

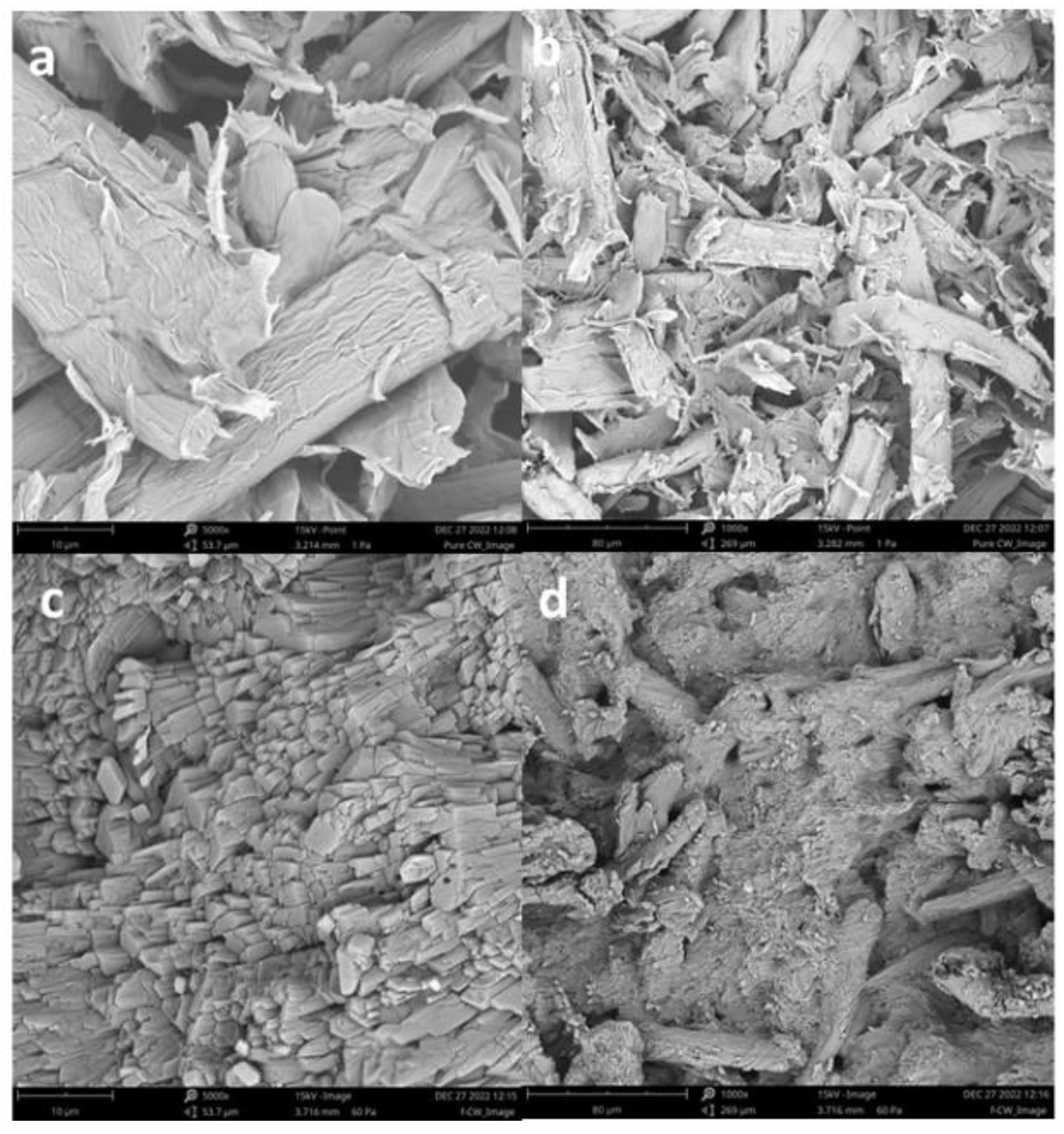

The microstructure and morphology of CW compared to functionalized CW are shown in the SEM images of

Figure 12. A significant difference in terms of its structural appearance and morphology were observed. It showed that from randomly oriented rod-shaped cellulose whiskers in

Figure 12a-b, the structure became more aligned in stacks of bundled rods, compact and dense after functionalization as presented in

Figure 12c-d. These results confirmed the crosslinked structure of the CW which has beneficial effects on the mechanical properties of the CW. Further analyzing the SEM images using Image J software (version 7.0.0), the average fiber diameter of 6.16 um and length of 2977 um and the aspect ratio (L/D) were calculated as 483.27 which is higher than the usual range of 5-50 aspect ratio. The higher aspect ratio opens many possibilities for creating new materials and facilitating chemical processes, like for functionalization due to the surface energy and it also potentially lowers agglomeration level than unmodified cellulose whiskers.

3.6. Electrochemical Capacity of Cellulose Whisker

An important indicator of electrochemical capacity of a material is the ion exchange capacity (IEC) based on the number of ions present as active sites. In this case, the sulfonate groups present in the CWs have influence on the electrochemical reaction for proton transport in the PEM. The electrochemical capacity of CW was measured based on the ion exchange capacity (IEC) which was influenced by the water absorption capacity in terms of hydrophilicity. The functionalization showed little effect on surface chemistry in terms of water contact angle which resulted to a change in surface wettability from completely wetted surface to an angle of 3.16

o. The calculated IEC of the CW ranged from 1.51–1.77 meq/g showed that CW retained its -SO

2 functional groups as indicator of electrochemical capacity as shown in

Table 7. Thus, the functionalization of CW had no effect on the IEC after changes in microstructure and morphology due to surface modification.

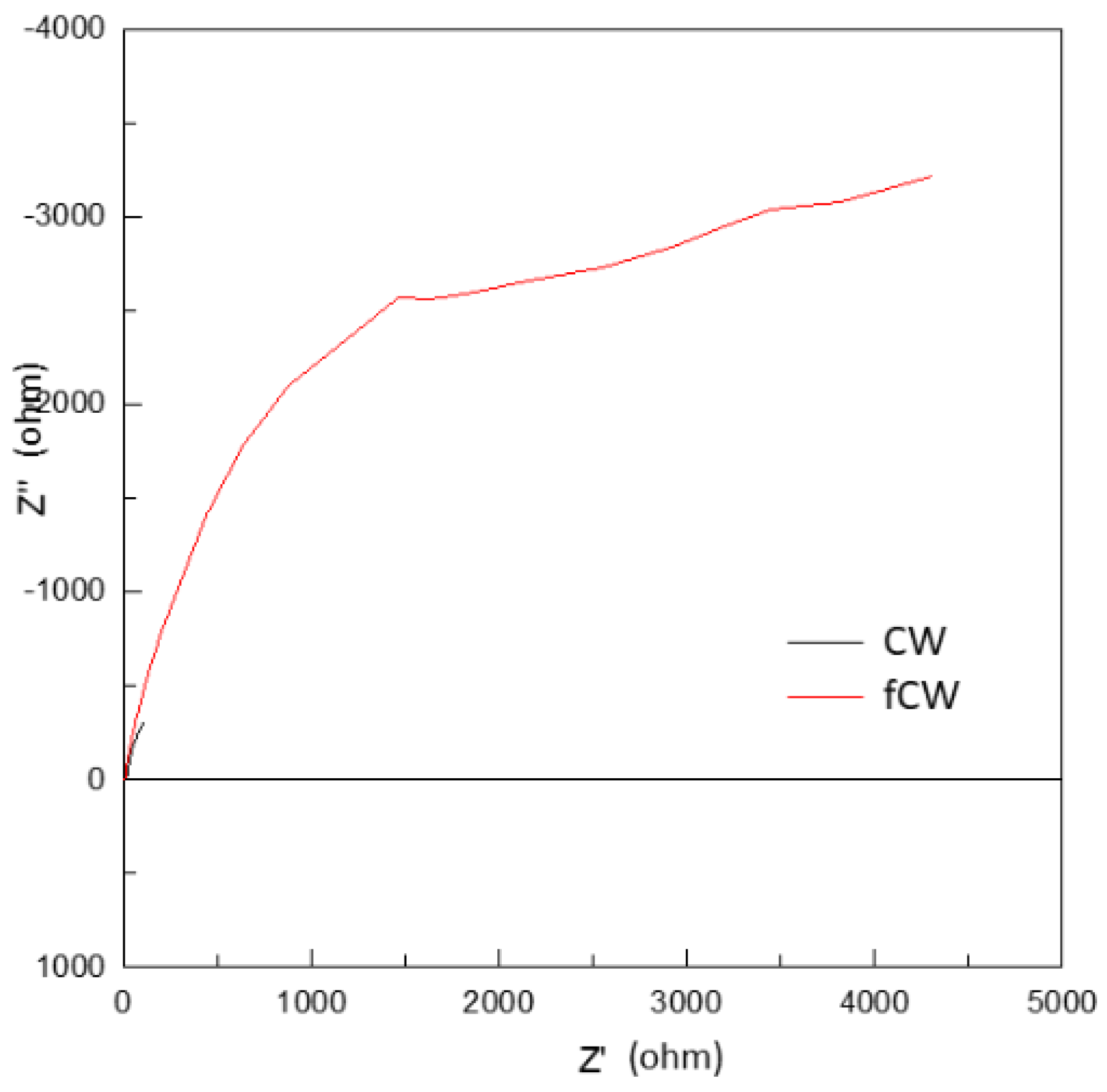

In relation to the electrochemical properties, the conductivity properties of the functionalized CW and unmodified CW were calculated based on the Nyquist plots in

Figure 13 showing the impedance graph that represents the correlated bulk resistance of the synthesized and functionalized CW based on the equivalent circuit model fitted to the plots. This was used for the calculation of the ionic or proton conductivity.

The value of proton conductivity was computed using the equation:

where σ is the value of proton conductivity, L is the distance between the reference-sensing electrodes, R is the tested resistance of CW, and A is the effective cross-sectional area, respectively. The calculated ionic conductivity for CW and functionalized CW were 0.0064 S/cm and 0.016 S/cm, receptively. The functionalization of CW resulted to higher ionic conductivity after changes in structural composition and morphology due to modification. These results proved that CW could provide added functionalities to the hybrid PEM.

3.7. Hybrid Membrane with Cellulose Whisker as Filler

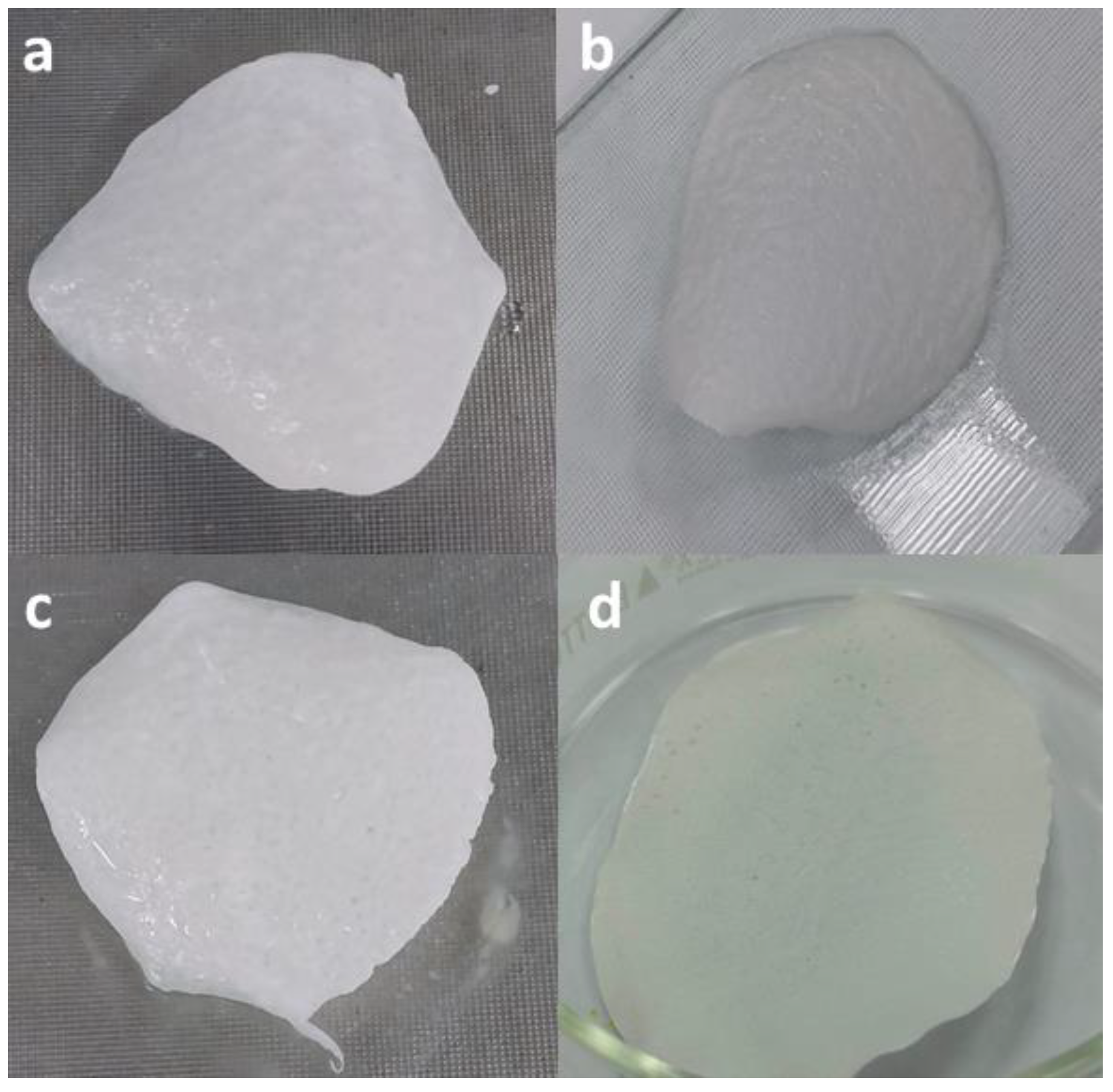

The fabrication of hybrid membrane with CW as filler utilized solution casting method which is the simplest approach for forming the membrane. In this study, the polymer dissolution process was screened by using different solvents or mixture of solvents. This is in consideration of using green solvents in order for the composite to be non-toxic, recyclable and eco-friendly. There were different solvents or mixture of solvents tested for their ability to fully dissolve the polymer. Polysulfone (PSU) was used as the polymer because it is considered as an emerging and a concrete alternative to Nafion ionomer for the development of proton exchange electrolytic membranes for being low cost, environmentally friendly and high-performance PEM. The polymer-filler blend was carried out with 20% polymer-filler concentration in DMSO/THF binary solvents. Initially, the membrane preparation was tested with different amount of filler loading as % of the total polymer (0%, 3%, 5% and 8%).

Ultrasonication of the CW in the binary solvent prior to blending with the PSU solution was effective in dispersing the material in the solvent and homogenizing the CW in the solution with polysulfone (PSU). The initial trials of membrane preparation with CW at different % loading showed no separation from the polymer phase in the fabricated hybrid membrane as shown in

Figure 14.

In order to test the structural stability of the hybrid membrane with the addition of filler, the tensile strength of the hybrid membrane was determined using UTM. The average thickness of the hybrid membrane with 0 to 8% filler loading ranged from 0.21- 0.22 mm. The results of the tests are summarized in

Table 8. It showed that there was slight improvement in the tensile strength of the hybrid membrane from 13.48 to 13.76 MPa for 0, 3 and 5% filler loading. The enhancement from the addition of filler was not yet significant considering that the filler loading was still low. However, in the 8% filler loading, the tensile strength decreased to 9.33 MPa which was low compared to the other membrane samples. This indicated that the results were not yet conclusive since the loading of filler is still at low level and further testing of samples were needed as part of the next phase of the study where filler loading will be increased up to 15%.

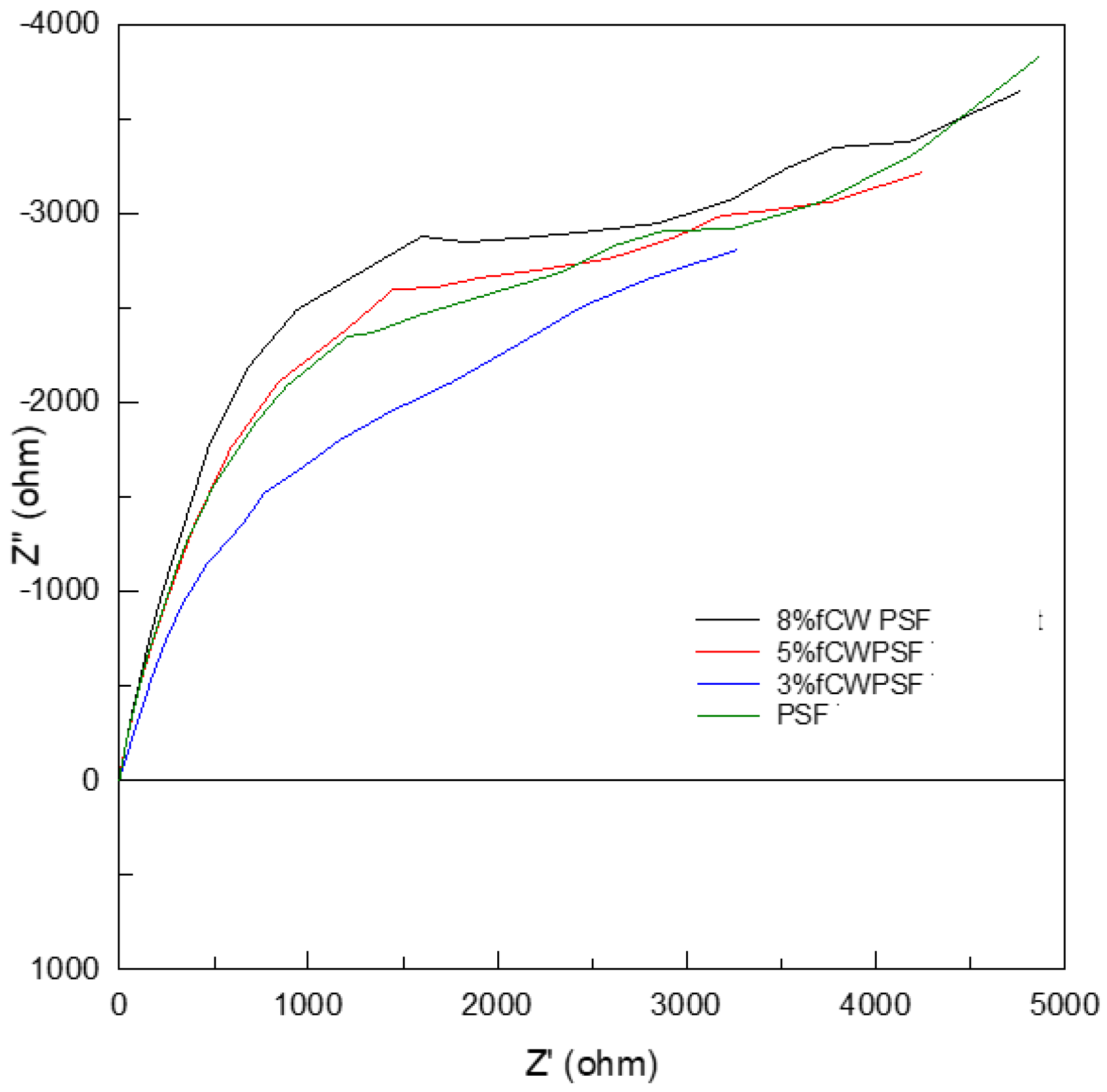

The more important aspect of CW loading in the polymer membrane was the enhanced functionalities. The proton conductivity of the pristine PSU and membrane with different % CW were measured using Electrochemical Impedance Spectrometer (EIS) by using Nyquist plots to obtain the impedance graph for the estimation of bulk resistance as shown in

Figure 15. The proton conductivity values of the four samples are summarized in

Table 9. The highest proton conductivity was recorded at 0.0192 S/cm for membrane with 5% CW which also had the highest incremental change of 10.9% compared to the pristine PSU membrane. The membranes with 3% and 8% CW have proton conductivities of 0.0182 and 0.0189 S/cm, respectively. Although the results showed an increase in proton conductivity by adding the CW into the PSU, the proton conductivities of the three membranes are statistically the same. This means that the addition of 3-8% of CW contributed to the enhancement of the proton conductivity but they were statistically the same values. With these results, although further optimization is needed it has proven that CW could be synthesized and utilized as filler for membrane. The next iteration of the study is to further increase the filler loading up to 15-20%, if there will still be significant enhancement in the properties including the investigation of the agglomeration and dispersion of CW in the morphology of hybrid membrane with higher loading. Based on previous report, each cellulose unit possesses three hydroxyl groups, and CWs exhibit a high surface area, resulting in a high density of surface hydroxyls.[

50,

51] This leads to CW agglomeration, poor compatibility, and weak interfacial interactions with nonpolar matrices, [

44,

52] particularly at loadings exceeding 3 wt.%. [

53]

4. Conclusions

This study was able to utilize cotton linters in the conversion of more useful advanced materials with value adding properties in fabrication of a polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) of fuel cells. The physical composition of the starting material as cellulose with high crystallinity due to high cellulose II content is considered as natural polymer with microstructures that are suitable for tailoring diverse functionalities. Through the application of facile alkali treatment followed by acid hydrolysis, the cotton cellulosic materials were synthesized into cellulose whiskers with functional groups present that were chemically reactive for functionalization. The chemical purification of cotton cellulose was achieved by higher alkali concentration removing unwanted non-cellulose contents while acid hydrolysis was employed at optimal treatment conditions of 60% acid concentration and 60 min of reaction time to produced higher crystalline material. The functionalization of CW led to effective modification of the surface properties and provide the desired electrochemical capacity to convert it into an active filler material. Cellulose whisker as filler has several advantages over other types of filler mainly, because of its organic origin and relatively low cost. In the fabrication of the hybrid membrane with cellulose whisker as filler, the hybrid membrane showed enhancement in the desired key property, proton conductivity, with the addition of small amount of filler material (3 to 5%) into the polymer matrix. This demonstrated the enhanced performance of the polymer composite with a considerable amount of CW added. Initially, the small amount was used to investigate the compatibility of the fillers with the polymer matrix to form a homogenized polymer-filler blend solution. These results need further optimization of the amount of CW which could possibly give the optimal properties but further investigations of the dispersion and the occurrence of agglomeration in the polymer matrix is also needed. Thus, the fabrication of hybrid polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) with the addition of cellulose-based filler provided the needed incremental improvement for polymer membrane that could possibly serves as electrolyte in electrochemical reactions of the membrane electrode of fuel cells. The results of this study served as preliminary research bases for more advanced study on cellulose whiskers as a more sustainable filler option for membrane that could be further improved by using other membrane fabrication methods.

5. Patents

This study has produced two (2) patents: Green-Modified Crosslinked Filler from Cellulose Whisker of Cotton Linter as Energy Material and Highly Crystalline Cellulose Whisker from Cotton Linter as Green Nanofiller of Hybrid Composite Membrane both filed at the Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines (IPOPhil) in 2024.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.P.J.; Methodology, R.P.P.J.; Formal analysis, R.P.P.J.; Investigation, R.P.P.J., and R.A.B.J; Data curation and analysis, R.P.P.J., R.A.B.J. and J.L.R. Resources, R.P.P.J. and AVOB; Writing – original draft preparation, R.P.P.J.; Writing – review and editing, R.P.P.J.; Funding acquisition, R.P.P.J. and A.V.O.B.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Energy (DOE) through a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with the Department of Science and Technology – Industrial Technology Development Institute (DOST-ITDI).

Data Availability Statement

Data for this article, including raw or processed data and metadata files, such as spectra, images, figures, graphs are available at Open Science Framework at

https://osf.io/hjp46/.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported through a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the Industrial Technology Development Institute (ITDI) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) and Energy Utilization Management Bureau (EUMB) of the Department of Energy (DOE) through the project titled, “Establishment of Fuel Cell R&D and Testing Facility”. The authors thank Dr. Annabelle V. Briones, Director of ITDI and Mr. Patrick T. Aquino, Director of EUMB for their full support to the project. Also, the Material Science Division (MSD) of ITDI for the conduct of additional tests on the samples and the Alternative Fuels and Energy Technology Division (AFETD) of DOE for their full cooperation and assistance to the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. Philippot, G. Alvarez, E. Ayerbe, J. Van Mierlo, M. Messagie, Eco-Efficiency of a Lithium-Ion Battery for Electric Vehicles: Influence of Manufacturing Country and Commodity Prices on GHG Emissions and Costs, Batteries, 2019, 5, 23. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Allwood, J. M. Cullen, Sustainable Materials: With Both Eyes Open, 2012, UIT Cambridge Ltd, Cambridge, England.

- Deng J, Li M, Wang Y. Biomass-derived carbon: synthesis and applications in energy storage and conversion, Green Chem, 2016, 18, 4824–54. [CrossRef]

- K.D. Kreuer, On the development of proton conducting polymer membranes for hydrogen and methanol fuel cells, J Membr Sci., 2001, 185(1), 29-39. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Correa, J.M. Montalvo-Navarrete, M.A. Hidalgo-Salazar, Carbon footprint considerations for biocomposite materials for sustainable products: A review, J Clean Prod, 2019, 208,785–94. [CrossRef]

- O. Adekomaya, T. Jamiru, R. Sadiku, Z. Huan, A review on the sustainability of natural fiber in matrix reinforcement – A practical perspective, J Reinf Plast Compos, 2015, 35, 3–7. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Milner, A.C. Woodard, Sustainability of engineered wood products, Sustainability of Construction Materials, Woodhead Publishing, 2016, 159–80.

- D. D’Amato, M. Gaio, E. Semenzin, A review of LCA assessments of forest-based bioeconomy products and processes under an ecosystem services perspective, Sci Total Environ, 2020, 706, 135859. [CrossRef]

- R. Bergman, M. Puettmann, A. Taylor, K.E. Skog, The Carbon Impacts of Wood Products, Forest Prod J, 2014, 64, 220–31. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Shaharuzaman, S.M. Sapuan, M. R. Mansor, Sustainable materials selection: Principles and applications, Design for Sustainability: Green Materials and Processes, 2021, 57-84.

- R. A. Sheldon, Green chemistry, catalysis and valorization of waste biomass, J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem., 2016, 422, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Clark and A. S. Matharu, in Issues in Environmental Science and Technology: Waste as a Resource, ed. R. E. Hester and R. M. Harrison, Royal Society, 2013, 37, pp. 66-82.

- T. Mekonnen, P. Mussone, D. Bressler, Valorization of rendering industry wastes and co-products for industrial chemicals, materials and energy: review, Crit. Rev. Biotechnol, 2016, 36, 120–131.

- M. J.H. Worthington, R.L. Kucera, J.M. Chalker, Green chemistry and polymers made from sulfur, Green Chem., 2017, 19(12), 3358-3393. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, G. He, S. Wang, S. Yu, F. Pan, H. Wu, Z. Jiang, Recent advances in the fabrication of advanced composite membranes, Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2013, 1(35), 10058–10077. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Teo, R.A. Wahab, Towards an eco-friendly deconstruction of agro-industrial biomass and preparation of renewable cellulose nanomaterials: A review, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 161, 1414–1430. [CrossRef]

- D. Klemm, B. Heublein, H-P, Fink, A. Bohn, Cellulose: Fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2005, 44(22).

- X. Tang, D. Liu, Y.J. Wang, L. Cui, A. Ignaszak, Y. Yu, J. Zhang, Research advances in biomass-derived nanostructured carbons and their composite materials for electrochemical energy technologies, In Progress in Materials Science, 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- J. P. S. Morais, M. F. Rosa, M.M.S. Filho, L. D. Nascimento, D. M. Nascimento, A. R. Cassales, Extraction and characterization of nanocellulose structures from raw cotton linter, Carbohydrate Polymers, 2013, 91(1), 229-235. [CrossRef]

- G.X. Gu, M. Takaffoli, A.J. Hsieh, M.J. Buehler, Biomimetic additive manufactured polymer composites for improved impact resistance, Extreme Mech Lett, 2016, 9, 317-323. [CrossRef]

- G. Clark, J. Kosoris, L. N. Hong, M. Crul, Design for Sustainability: Current Trends in Sustainable Product Design and Development, Sustainability, 2009, 1, 409-424. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zheng, T. Zhou, Y. Wang, et al., Pretreatment of wheat straw leads to structural changes and improved enzymatic hydrolysis, Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 1321. [CrossRef]

- S. M.L. Rosa, N. Rehman, M.I. G. Miranda, S. M.B. Nachtigall, C. I.D. Bica, Chlorine-free extraction of cellulose from rice husk and whisker isolation, Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012, 87(2), 1131-1138. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Karaaslan, M.A. Tshabalala, D.J. Yelle, G. Buschle-Diller, Nanoreinforced biocompatible hydrogels from wood hemicelluloses and cellulose whiskers, Carbohydr. Polym., 2011, 86, 192–201. [CrossRef]

- A. Bendahou1, Y. Habibi, H. Kaddami, A. Dufresne, Physico-chemical characterization of palm from phoenix dactylifera–L, preparation of cellulose whiskers and natural rubber–based nanocomposites, J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy, 2009, 3, 81–90.

- A.T.W.M. Hendriks, G. Zeeman, Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass, Bioresource Technology, 2009, 100, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, J. Wang, Y.Z. Yang, G.H. Xie, Alkali-based pretreatments distinctively extract lignin and pectin for enhancing biomass saccharification by altering cellulose features in sugar-rich Jerusalem artichoke stem, Bioresource Technology, 2016, 208, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- A. Kljun, T. A.S. Benians, F. Goubet, F. Meulewaeter, J.P. Knox, and R. S. Balckburn, Comparative analysis of crystallinity changes in cellulose I polymers using ATR-FTIR, X-ray diffraction, and carbohydrate-binding module probes, BioMacromolecules, 2011, 12, 4121-4126. [CrossRef]

- S. M.L. Rosa, N. Rehman, M.I. G. Miranda, S. M.B. Nachtigall, C. I.D. Bica, Chlorine-free extraction of cellulose from rice husk and whisker isolation, Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012, 87, 2, 1131-1138. [CrossRef]

- R. Vârban, I. Crișan, D. Vârban, A. Ona, L. Olar, A. Stoie, R. Stefan, Comparative FTIR Prospecting for Cellulose in Stems of Some Fiber Plants: Flax, Velvet Leaf, Hemp and Jute, Applied Sciences, 2021, 11(18), 8570.

- D. Ciolacu, F. Ciolacu, V.I. Popa, Amorphous cellulose - Structure and characterization, Cellulose Chemistry and Technology, 2011, 45(1), 13-21.

- T. Theivasanthi, F.L. Anne Christma, Adeleke Joshua Toyin, Subash C.B. Gopinath, Ramanibai Ravichandran, Synthesis and characterization of cotton fiber-based nanocellulose, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 109, 832-836. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Mohomane, S. V. Motloung, L. F. Koao, T. E. Motaung, Effects of Acid Hydrolysis on the Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC): A Review, Cellulose Chem. Technol., 2022, 56 (7-8), 691-703. [CrossRef]

- A. Krishna Shailaja, B. Pranaya Ragini, Nanocellulose: Preparation, Characterization and Applications, J. Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology Research, 2022, 5(1).

- Q. Cheng, S. Wang, T. G. Rials, Poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose fibrils isolated by high intensity ultrasonication, Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 2009, 40, 2, 218-224. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Taherzadeh, K. Karimi, Enzyme-based hydrolysis processes for ethanol from lignocellulosic materials: a review, BioResources, 2007, 2(3), 707–38. [CrossRef]

- D. Kumar, B. Singh, J. Korstad, Utilization of lignocellulosic biomass by oleaginous yeast and bacteria for production of biodiesel and renewable diesel, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017, 73, 654-671. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhong, R. Dhandapani, D. Liang, J. Wang, M. P. Wolcott et al., Nanocellulose from recycled indigo-dyed denim fabric and its application in composite films, Carbohyd. Polym., 2020, 240, 1116283. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Silvério. W. P. F. Neto, N. O. Dantas and D. Pasquini, Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from corncob for application as reinforcing agent in nanocomposites, Ind. Crop. Prod., 2013, 44, 427. [CrossRef]

- Y. Habibi, L.A. Lucia, O.J. Rojas, Cellulose nanocrystals: Chemistry, self assembly, and applications, Chemical Reviews, 2010, 110(6), 3479-3500.

- M. Jakob, A. R. Mahendran, W. Gindl-Altmutter, P. Bliem, J. Konnerth, U. Müller, S. Veigel, The strength and stiffness of oriented wood and cellulose-fibre materials: A review, Progress in Materials Science, 2022, 125, 100916. [CrossRef]

- M. Sumita, K. Sakata, S. Asai, K. Miyasaka, H. Nakagawa, Dispersion of fillers and the electrical conductivity of polymer blends filled with carbon black, Polymer Bull, 1991, 25(2), 265-271. [CrossRef]

- N. Shaari, S. K. Kamarudin, Recent advances in additive-enhanced polymer electrolyte membrane properties in fuel cell applications: An overview, Int J Energy Res., 2019, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- P. Lu, Y.L. Hsieh, Preparation and properties of cellulose nanocrystals: rods, spheres, and network, Carbohyd Polym, 2010, 82, 329-336. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, S.Q. Shi, H.M. Barnes, J.C.U. Pittman, A chemical process for preparing cellulosic fibers hierarchically from kenaf bast fibers, BioResources, 2011, 6, 879-890. [CrossRef]

- A.N. Nakagaito, A. Fujimura, T. Sakai, Y. Hama, H. Yano, Production of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC)-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) nanocomposites from sheets obtained by a papermaking-like process, Compos Sci Technol, 2009, 69, 1293-1297. [CrossRef]

- R. Bergman, M. Puettmann, A. Taylor, K.E. Skog, The Carbon Impacts of Wood Products, Forest Prod J, 2014, 64, 220–31. [CrossRef]

- O. Selyanchyn, T. Bayer, D. Klotz, R. Selyanchyn, K. Sasaki, S. M. Lyth, Cellulose Nanocrystals Crosslinked with Sulfosuccinic Acid as Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes for Electrochemical Energy Applications, Membranes, 2022, 12, 658. [CrossRef]

- L. Goetz, A. Mathew, K. Oksman, P. Gatenholm, A.J. Ragauskas, A novel nanocomposite film prepared from crosslinked cellulosic whiskers, Carbohydr. Polym., 2009, 75, 85–89. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Lee, Y. Teramoto, T. Endo, Cellulose nanofiber-reinforced polycaprolactone/polypropylene hybrid nanocomposite, Compos Part A, 2011, 42, 151-156. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, X.L. Yang, C.Y. Li, M. Liang, C.H. Lua, Y.L. Deng, Mechanochemical activation of cellulose and its thermoplastic polyvinyl alcohol ecocomposites with enhanced physicochemical properties, Carbohyd Polym, 2011, 83, 257-263. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Kabir, M.M. Huque, M.R. Islam, A.K. Bledzki, Mechanical properties of jute fiber reinforced polypropylene composite: effect of chemical treatment by benzenediazonium salt in alkaline medium, BioResources, 2009, 5(3), 1618-1625. [CrossRef]

- S. Nandi, P. Guha, A Review on Preparation and Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystal-Incorporated Natural Biopolymer, Journal of Packaging Technology and Research, 2018, 2, 149–166. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

a) Cotton cellulose after alkali treatment and b) cotton cellulose after drying.

Figure 1.

a) Cotton cellulose after alkali treatment and b) cotton cellulose after drying.

Figure 2.

Interaction plots showing the effect of one independent variable (NaOH concentration) changes the level of the dependent variable (Yield).

Figure 2.

Interaction plots showing the effect of one independent variable (NaOH concentration) changes the level of the dependent variable (Yield).

Figure 3.

ATR-FTIR spectra with the presence of O-H groups and C-H stretching vibration of cellulose.

Figure 3.

ATR-FTIR spectra with the presence of O-H groups and C-H stretching vibration of cellulose.

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of more crystalline material of Cotton Cellulose.

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of more crystalline material of Cotton Cellulose.

Figure 5.

Cotton linters converted from a) cellulose to b) cellulose whiskers.

Figure 5.

Cotton linters converted from a) cellulose to b) cellulose whiskers.

Figure 6.

Interaction plots showing the effects of independent variables (H2SO4 concentration and Reaction Time) on the changes of level of the dependent variable (Yield).

Figure 6.

Interaction plots showing the effects of independent variables (H2SO4 concentration and Reaction Time) on the changes of level of the dependent variable (Yield).

Figure 7.

ATR-FTIR spectra of the cellulose whiskers at different treatment combinations, a) 60/60, b) 60/45, c) 55/60 and d) 55/45.

Figure 7.

ATR-FTIR spectra of the cellulose whiskers at different treatment combinations, a) 60/60, b) 60/45, c) 55/60 and d) 55/45.

Figure 8.

Interaction plots showing the effects of independent variables (H2SO4 concentration and Reaction Time) on the changes of the level of dependent variable (% TCI).

Figure 8.

Interaction plots showing the effects of independent variables (H2SO4 concentration and Reaction Time) on the changes of the level of dependent variable (% TCI).

Figure 9.

XRD Diffractograms of cellulose whiskers at different treatment combinations, a) 60/60, b) 60/45, c) 55/60 and d) 55/45.

Figure 9.

XRD Diffractograms of cellulose whiskers at different treatment combinations, a) 60/60, b) 60/45, c) 55/60 and d) 55/45.

Figure 10.

ATR-FTIR spectra of the functionalized cellulose whiskers.

Figure 10.

ATR-FTIR spectra of the functionalized cellulose whiskers.

Figure 11.

Water contact angle of a) CW and b) functionalized CW.

Figure 11.

Water contact angle of a) CW and b) functionalized CW.

Figure 12.

SEM micrographs of (a-b) CW and (c-d) functionalized CW: (magnification: 5000x and 10000x; scale bar: 8-10 um).

Figure 12.

SEM micrographs of (a-b) CW and (c-d) functionalized CW: (magnification: 5000x and 10000x; scale bar: 8-10 um).

Figure 13.

Nyquist Plots of CW and functionalized CW.

Figure 13.

Nyquist Plots of CW and functionalized CW.

Figure 14.

Hybrid composite with CW at a) 0%, b) 3%, c) 5% and d) 8% loading.

Figure 14.

Hybrid composite with CW at a) 0%, b) 3%, c) 5% and d) 8% loading.

Figure 15.

Nyquist Plots of hybrid membrane with CW loading of 0, 3,5 and 8%.

Figure 15.

Nyquist Plots of hybrid membrane with CW loading of 0, 3,5 and 8%.

Table 1.

Experimental Design for Alkali Treatment.

Table 1.

Experimental Design for Alkali Treatment.

| Independent Variable/Factor |

Levels |

Dependent Variables/ Responses |

| Low |

Mid |

High |

| NaOH Concentration, wt % |

5 |

10 |

15 |

Yield and Structural Composition (FTIR) |

Table 2.

Experimental Design for Acid Hydrolysis.

Table 2.

Experimental Design for Acid Hydrolysis.

| Independent Variables/Factors |

Levels |

Dependent Variables/ Responses |

| Low |

High |

| H2SO4 Concentration, wt % |

55 |

60 |

Yield, %

Total Crystallinity Index, %

Structural Composition and Evolution |

| Reaction Time, min |

45 |

60 |

Table 3.

Composition of Common Biomass Wastes.

Table 4.

Yield at Different Concentration of NaOH.

Table 4.

Yield at Different Concentration of NaOH.

| Std |

Run |

Block |

A: NaOH |

Response |

| Conc, % |

Yield, % |

| 1 |

1 |

Block 1 |

5% |

92.77 |

| 3 |

2 |

Block 1 |

10% |

92.64 |

| 5 |

3 |

Block 1 |

15% |

90.45 |

| 6 |

4 |

Block 2 |

15% |

91.48 |

| 4 |

5 |

Block 2 |

10% |

92.58 |

| 2 |

6 |

Block 2 |

5% |

92.70 |

Table 5.

Yield at Different Concentration of Treatment Combinations of Acid Hydrolysis.

Table 5.

Yield at Different Concentration of Treatment Combinations of Acid Hydrolysis.

Run |

Block |

Factor 1

A: Concentration, % |

Factor 2

B: Reaction Time, min |

Yield % |

| 1 |

Block 1 |

55 |

60 |

92 |

| 2 |

Block 2 |

60 |

60 |

35 |

| 3 |

Block 1 |

60 |

45 |

30 |

| 4 |

Block 2 |

60 |

60 |

43 |

| 5 |

Block 1 |

55 |

45 |

77 |

| 6 |

Block 2 |

55 |

45 |

87 |

| 7 |

Block 1 |

60 |

45 |

31 |

| 8 |

Block 2 |

55 |

60 |

84 |

Table 6.

Comparison of CrI and TCI for CW samples.

Table 6.

Comparison of CrI and TCI for CW samples.

| Sample |

CrI, % |

TCI, % |

Std Dev |

| 60/60 |

72.4 |

75.6 |

2.2 |

| 55/60 |

69.5 |

69.1 |

0.2 |

| 60/45 |

70.9 |

71.5 |

0.4 |

| 55/45 |

70.0 |

65.9 |

2.9 |

Table 7.

Ion Exchange Capacity (IEC) of CW samples.

Table 7.

Ion Exchange Capacity (IEC) of CW samples.

CW Sample

|

IEC, meq/g |

| Replicate 1 |

Replicate 2 |

Average |

| CW 1 |

1.82 |

1.72 |

1.77 |

| CW 2 |

1.74 |

1.61 |

1.68 |

| CW 3 |

1.60 |

1.42 |

1.51 |

Table 8.

Tensile strength of hybrid membrane at different % CW loading.

Table 8.

Tensile strength of hybrid membrane at different % CW loading.

| |

Tensile Strenght, MPa |

| Filler loading, % |

0 |

3 |

5 |

8 |

| Replicate 1 |

13.36 |

14.32 |

14.37 |

10.60 |

| Replicate 2 |

13.61 |

13.13 |

13.15 |

8.05 |

| Average |

13.48 |

13.72 |

13.76 |

9.33 |

Table 9.

Proton conductivity of hybrid membrane at different % CW loading.

Table 9.

Proton conductivity of hybrid membrane at different % CW loading.

| Membrane |

Conductivity (S/cm) |

% Change |

| Pure PSU |

0.0173 |

- |

| 3% fCW/PSU |

0.0182 |

5.2 |

| 5% fCW/PSU |

0.0192 |

10.9 |

| 8% fCW/PSU |

0.0189 |

9.3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).