2. Definition and Properties of “Aun” and “Aunnāda”

2.1. Aun and Aunnāda

In this paper, we define a fundamental entity in the universe called “aun.” An aun is a unit-like existence that spins (rotates on its own axis) and vibrates in a wave-like manner, yet possesses no physical volume, weight, or velocity—akin to a “ball” of pure structural dynamics.

Note: The terms “volume,” “weight,” and “velocity” used here are themselves complex concepts defined later, and are neither strictly present nor absent in an aun. Rather, the aun exists at a level more fundamental than such attributes.

aunnāda is a cluster of multiple aun that resonate together. Depending on the spin orientations and vibration patterns of the component aun, these resonant structures manifest as observable “matter particles” such as quarks, or as “forces” such as electromagnetism and the weak interaction.

2.2. Components of Aun

An aun, which perpetually spins and vibrates periodically, is composed of the following independent structural components:

- Spin rotation period (number of rotations per vibration cycle) (srp)

- Spin rotation direction (e.g., upward/downward)

- Vibration period

- Vibration deflection angle (vda)

Here are example configurations of aun:

| |

srp |

spin direction |

Vibration period |

vda |

| ex.1 |

1 |

upward |

7 |

0° |

| ex.2 |

1 |

downward |

7 |

17° |

| ex.3 |

1/2 |

upward |

2972 |

250° |

| ex.4 |

1 |

upward |

2972 |

17° |

| ex.5 |

1/2 |

downward |

194892987 |

10° |

The combinations of these components give aun a vast diversity of possible existence states. These serve as the foundation for forming the complex structures of aunnāda. The “existence state” of an aun refers to the pattern of its periods, spin directions, and vibrational biases. Though not directly observable, these form stable informational patterns that underlie the structure of the universe.

Furthermore, since aun exists outside of spacetime, its “vibration period” does not involve time. Only when aun forms an aunnāda does periodicity appear within the context of spacetime.

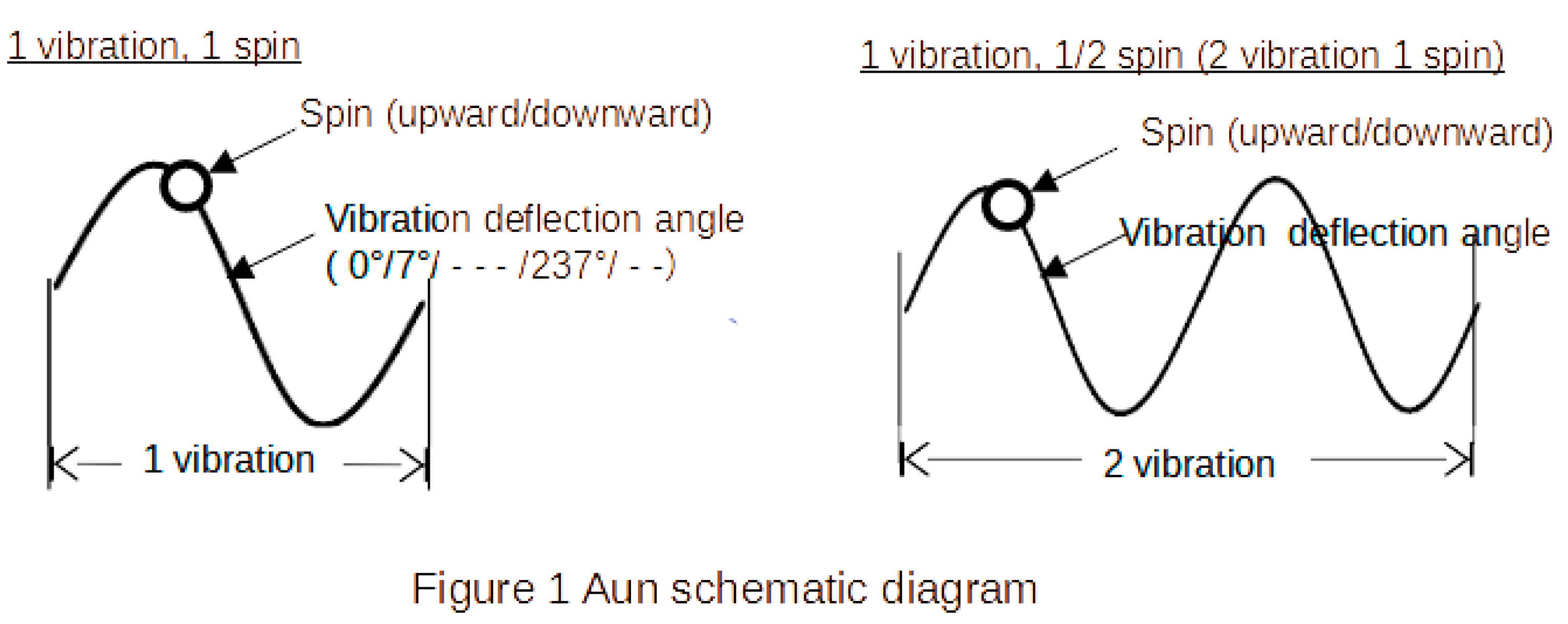

Figure 1.

Aun schematic diagram. Aun is spinning and vibrating. Some auns rotate one spin per vibration, others only half a spin per vibration.

Figure 1.

Aun schematic diagram. Aun is spinning and vibrating. Some auns rotate one spin per vibration, others only half a spin per vibration.

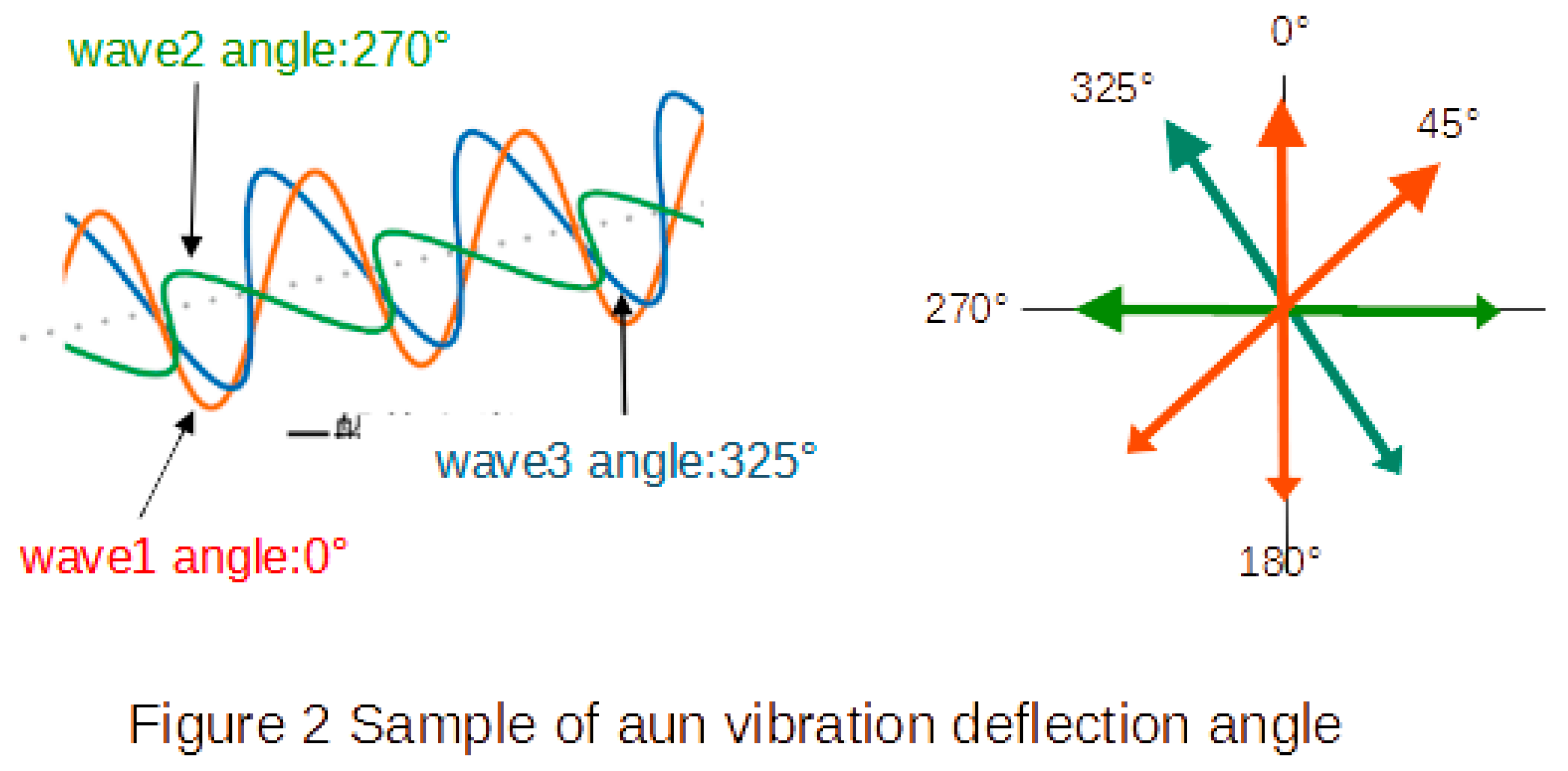

Figure 2.

Sample of aun vibration deflection angle. Aun vibrating surfaces come in many different forms.

Figure 2.

Sample of aun vibration deflection angle. Aun vibrating surfaces come in many different forms.

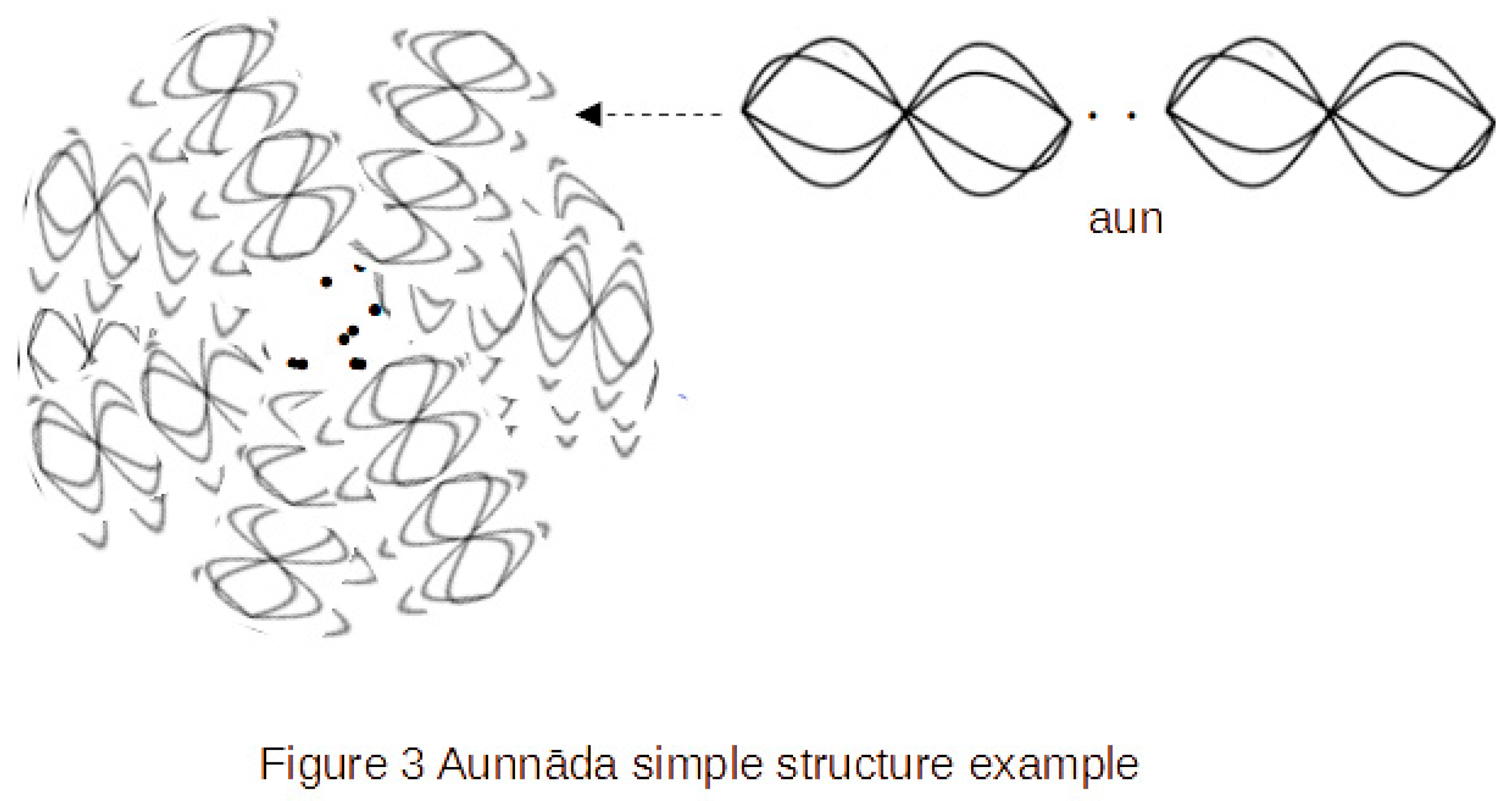

Figure 3.

Aunnāda simple structure example. Each unit has spin and prime-periodic vibration properties, which combine structurally to form a resonant field.

Figure 3.

Aunnāda simple structure example. Each unit has spin and prime-periodic vibration properties, which combine structurally to form a resonant field.

2.3. The Energy Function “AE”

Although aun has no physical volume or mass, it possesses a steady internal structure (spin, vibration, bias) that enables it to resonate with other aun. Through this resonance, it carries an energy that is best understood not as kinetic or potential energy, but as a kind of “phase energy of structural existence.”

The energy arising from the resonance between two aun is defined by the following function:

AE{ (Sdx, Spx, Vfx, Pdx) × (Sdy, Spy, Vfy, Pdy) }

Sdx, Sdy: Spin direction of aun x and y

Spx, Spy: Spin period of aun x and y

Vfx, Vfy: Vibration frequency of aun x and y

Pdx, Pdy: Wave bias (asymmetry) of aun x and y

In this way, the energy quantity AE, defined by the structural resonance of two aun, functions as the internal energy measure within an aunnāda.

2.4. Structure of Aunnāda

The total energy of an aunnāda is the summation of AE values resulting from the resonant existence of multiple aun. While the number of aun is not infinite, it is nearly so—referred to as ∞⁻ (quasi-infinite or limit-finite). The total energy is expressed as:

In the context of our present universe, this quasi-infinite summation can be decomposed into the following four components:

Note: Temporal and spatial terms are considered to be derivable from the four components above.

This energy is not simply kinetic or mass energy. Rather, it is interpreted as an accumulation of structural phase energy determined by the spin, vibration, and bias of each aun. This accumulation gives aunnāda its stable structure. Variations in this value correspond to how aunnāda behaves as a fundamental unit that transmits matter particles and forces.

2.5. Aun is Neither “Matter,” Nor “Wave,” Nor “Energy”

The entity known as aun does not fit into the conventional physical categories of “matter,” “wave,” or “energy.” It exists prior to such classifications—a more fundamental, abstract, and structural unit that forms the very precondition for the universe.

The energy “ae” associated with aun is also not to be understood as traditional mechanical or thermal energy, but as a “structural-phase value of existence.” In other words, aun is something “like energy,” but not energy as we conventionally understand it.

An aun never manifests in the phenomenal world on its own. Only when multiple aun resonate together to form an aunnāda does it become observable as a “matter particle” or “force.” Thus, all phenomena we observe in the real world are not direct manifestations of aun, but always appear as aunnāda—resonant clusters.

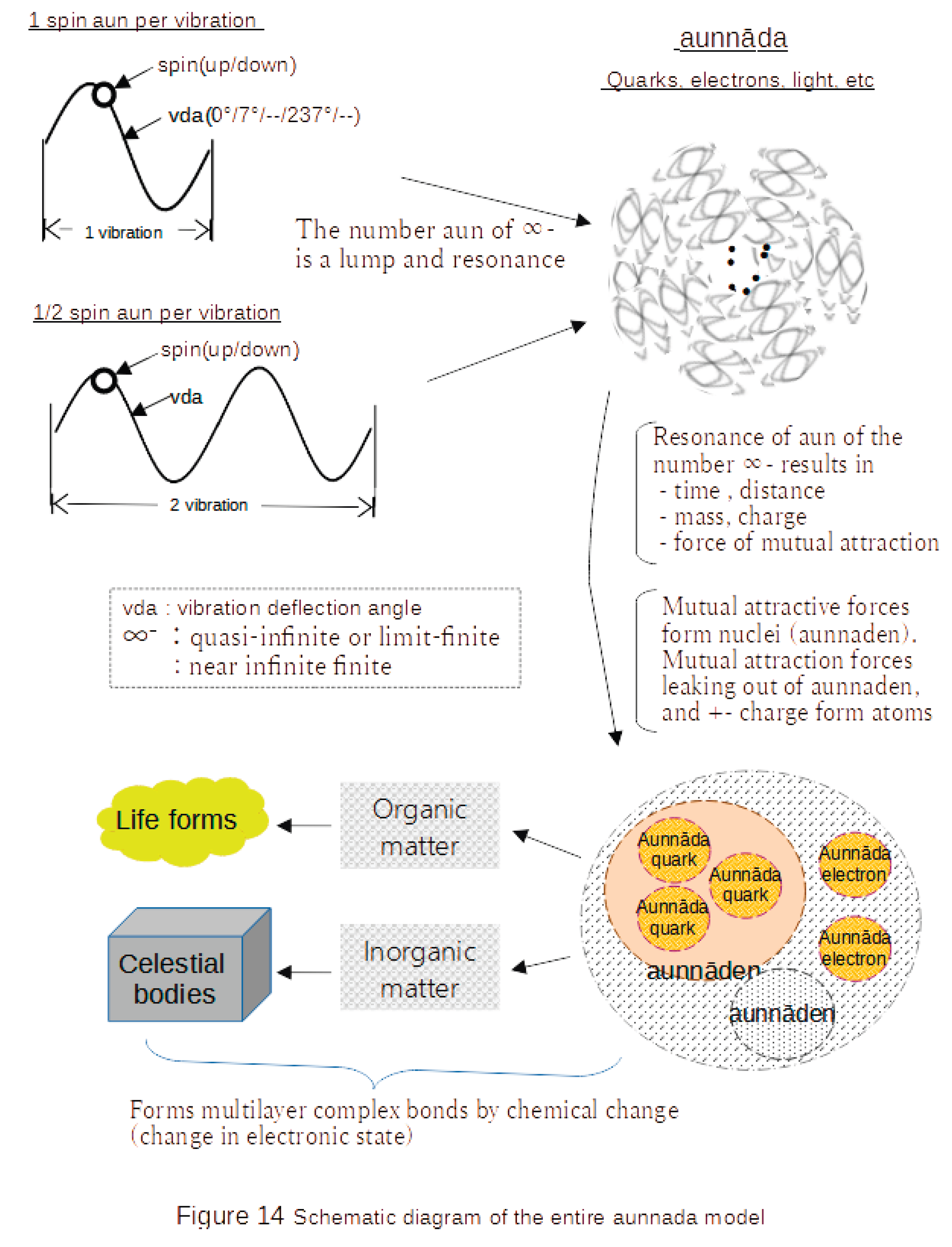

2.6. Formation of Complexity and Diversity

Aun, by itself, possesses an extremely simple structure and motion: spin and vibration. However, this simplicity is precisely what makes it fundamental. Through multilayered and hierarchical resonance among multiple aun, a structured entity known as aunnāda is formed. The resonance structure of aunnāda can then develop into quanta such as quarks and leptons, and further into hierarchical forms such as atoms and molecules.

Thus, from the combinations and expansive resonances of these simple building blocks called aun, the universe manifests astonishing complexity and diversity. This process continues to unfold even now, as the universe evolves, leading to the emergence of higher orders of structure, new modes of resonance, and increasing degrees of organization.

2.7. Relationship with Spacetime

The “aun” exists without any flow of time or spatial extension. It possesses neither “past” nor “future” and maintains only its structural states of spin and vibration.

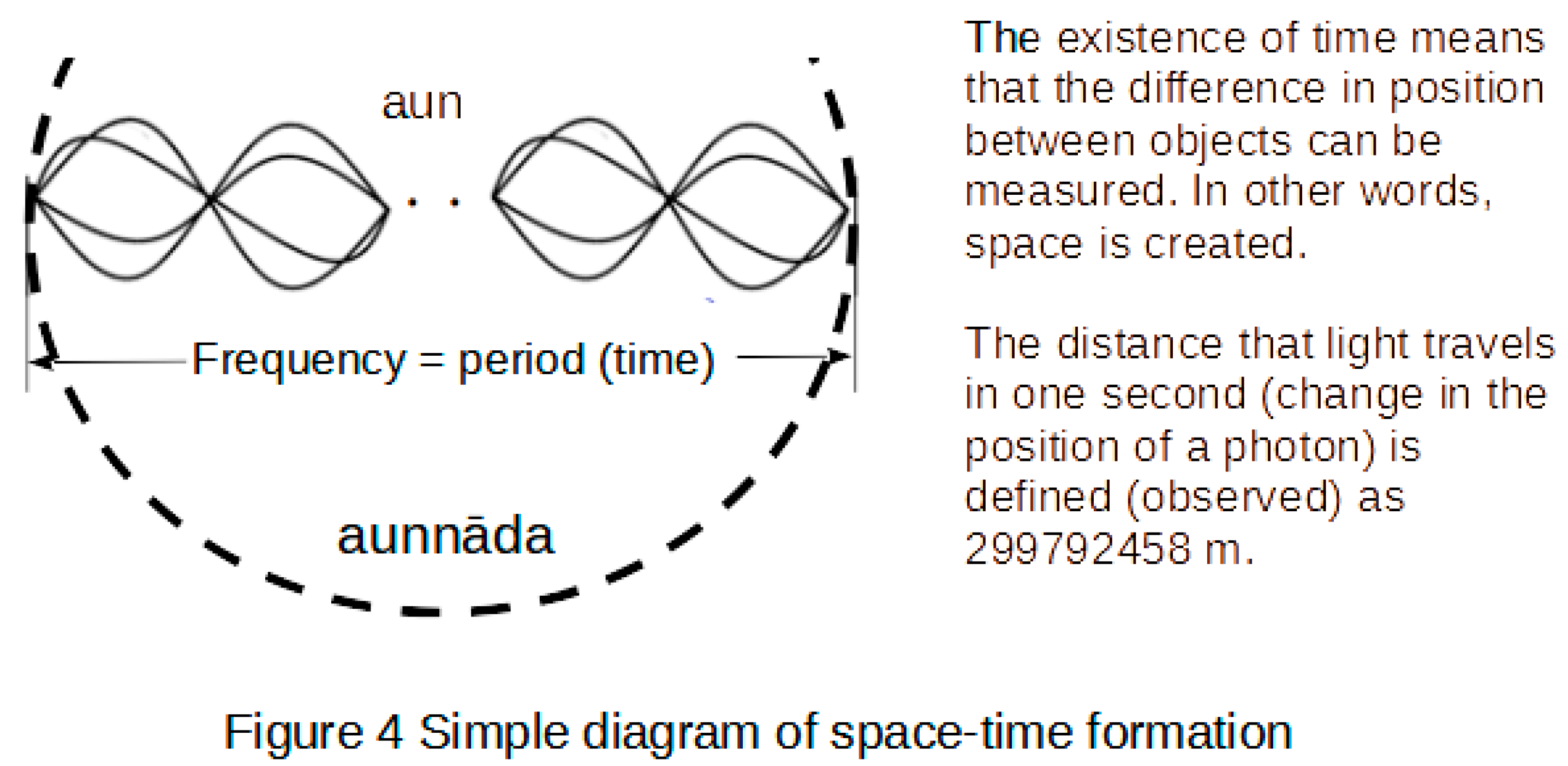

Time becomes perceivable as a “flow” only when auns structurally resonate within an “aunnāda,” allowing the counting of their vibrational cycles. In other words, the concept of “time” does not exist for an individual aun; it is defined within the structural motion of aunnāda.

The frequency of vibrations of the auns constituting an aunnāda determines the period (time) of the aunnāda. An increase in frequency leads to a longer period. Thus, an aunnāda formed with a very high vibration frequency results in a very long period.

The same applies to space. A single aun cannot define “distance” or “direction.” Only when multiple auns possess phase differences or a network of resonance do spatial concepts such as “position” and “interval” emerge.

From the above, it can be understood that auns are not entities within spacetime but rather foundational existences that precede and enable the very formation of spacetime.

Figure 4.

Simple diagram of space-time formation. The number of vibrations of aun within an aunnāda is the period (i.e., time), and the position difference between aunnāda is the distance.

Figure 4.

Simple diagram of space-time formation. The number of vibrations of aun within an aunnāda is the period (i.e., time), and the position difference between aunnāda is the distance.

2.8. The Prime Nature of Vibration Periods and Observability

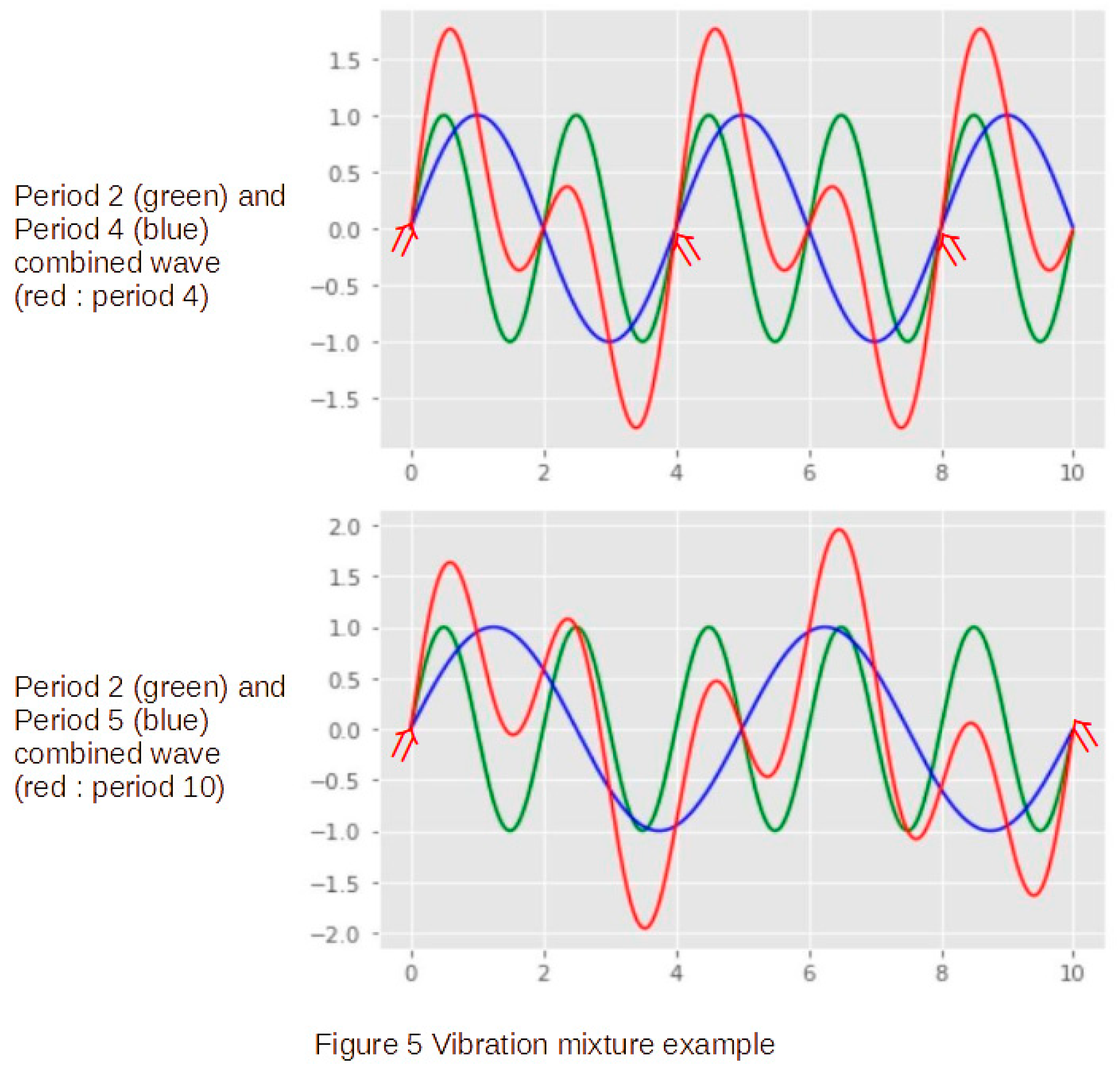

When a function with period 2 is combined with a function of period 4, the resulting function takes on a period equal to their least common multiple — that is, period 4. Similarly, combining a period-2 function with a period-5 function results in a period-10 function. In both cases, the original periodicities (2, 4, or 5) become indistinguishable in the resulting waveform. This implies that waves with non-prime periods are more susceptible to interference and mixing with others, causing their original information to become buried.

Likewise, when the vibration period of an aun is a non-prime number, it more readily overlaps with other auns in a periodic manner. Consequently, the resulting aunnāda — the resonant structure formed by these auns — tends to become blended, making it difficult to observe as a distinct and independent structure.

In contrast, an aun with a prime-numbered vibration period is far less likely to overlap periodically with others. Its resonance structure retains a greater degree of independence. Because of this, the vibrations of auns with prime periods are preserved as distinct “resonance nodes” within aunnāda. The larger the prime number, the less likely it is to interfere with other auns — the probability of interference theoretically approaches zero.

Thus, aunnāda formed from auns with prime-numbered vibration periods can maintain structural integrity without merging with other configurations, and can manifest as clearly observable “elementary particles” or “forces.” On the other hand, auns with non-prime periods — and the aunnāda structures they generate — may still “exist” within the universe, but are far more difficult (or even impossible) to observe as individual entities.

This mechanism provides a fundamental explanation as to why only certain particles and forces appear in our observable world. It suggests that the very nature of observability is deeply connected to the primality of the periodic vibrations of the underlying auns.

Figure 5.

Vibration mixture example. Aun vibrates like a wave, and the waves are mixtured with the least common multiple of the period.

Figure 5.

Vibration mixture example. Aun vibrates like a wave, and the waves are mixtured with the least common multiple of the period.

3. Elementary Particles

3.1. Matter Particles and Light (Photons)

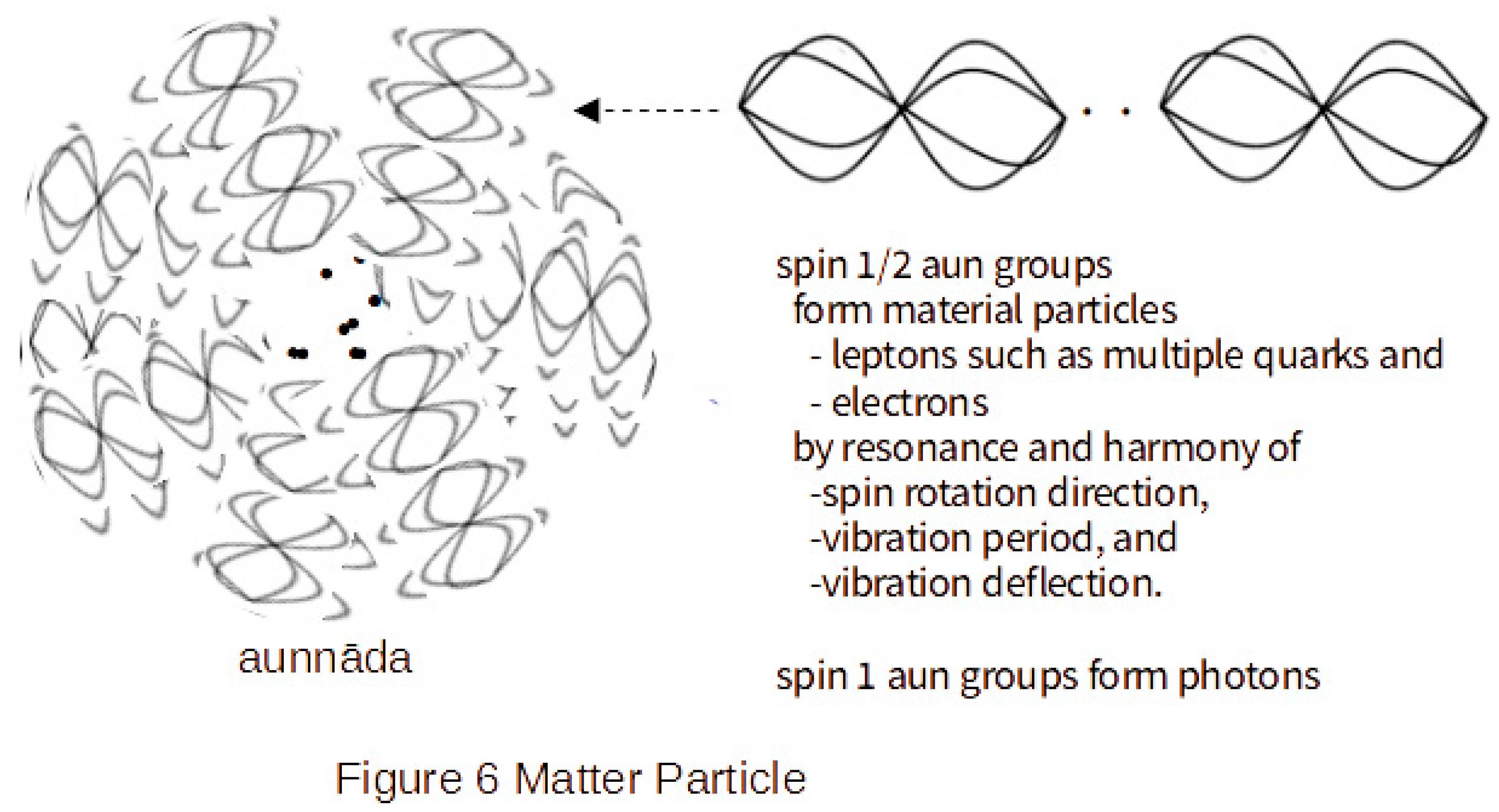

Quarks, electrons, and other entities we refer to as “matter particles,” as well as light (photons), are observed manifestations of “aunnāda” structures formed by “aun.” An aunnāda is a “cluster” composed of multiple auns resonating in specific spin and vibrational patterns. When observed externally, this cluster exhibits certain “asymmetries.” These asymmetries arise from the non-uniformities in the resonant structures within the aunnāda, such as the spin orientations, vibrational deflection, and rotational periods of the constituent auns.

Matter particles like quarks and leptons are observed as stable expressions of resonance asymmetries within groups of auns vibrating at a frequency of 1/2. For instance, the difference between down quarks and up quarks stems from variations in how their respective auns resonate—differences in vibrational periods, spin configurations, and vibrational deflection. Similarly, electrons and neutrinos are aunnāda with distinct resonance asymmetries, which manifest as measurable properties such as “mass” and “charge.”

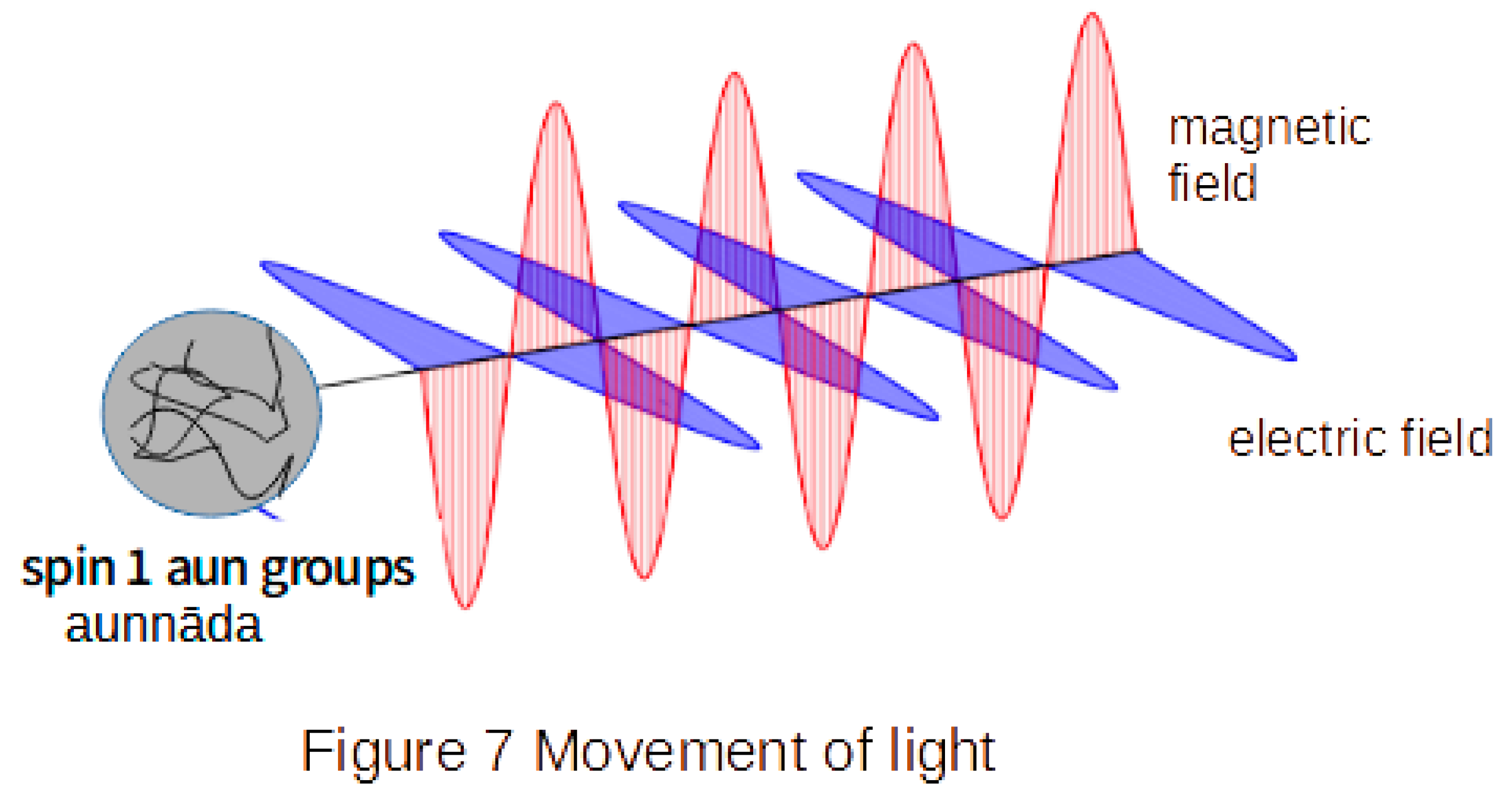

Light (photons) is an aunnāda formed from a group of auns resonating at a frequency of 1. The structure resulting from the resonance between the extension direction vector formed by deflection and the rotation direction vector formed by spin gives rise to orthogonal electric and magnetic fields. Thus, light is a manifestation of “deflection-spin resonance” propagating through space as orthogonal vector fields (E, B).

Note:

E: Electric field (unit: V/m)

B: Magnetic field (specifically magnetic flux density, unit: T)

“Matter particles” are not fundamental constituents of the universe but are transient stable forms of resonance structures—interpretations arising from our observations.

Figure 6.

Matter Particle. A huge number of auns resonate to form an aunnāda. Different forms of spin and vibration become matter particles such as quarks, electrons and photons.

Figure 6.

Matter Particle. A huge number of auns resonate to form an aunnāda. Different forms of spin and vibration become matter particles such as quarks, electrons and photons.

Figure 7.

Movement of light. Light (photons) is a figure of motion whose “polarization-spin resonance” is developed as an orthogonal vector field (E, B) in space.

Figure 7.

Movement of light. Light (photons) is a figure of motion whose “polarization-spin resonance” is developed as an orthogonal vector field (E, B) in space.

3.2. Aunnāden

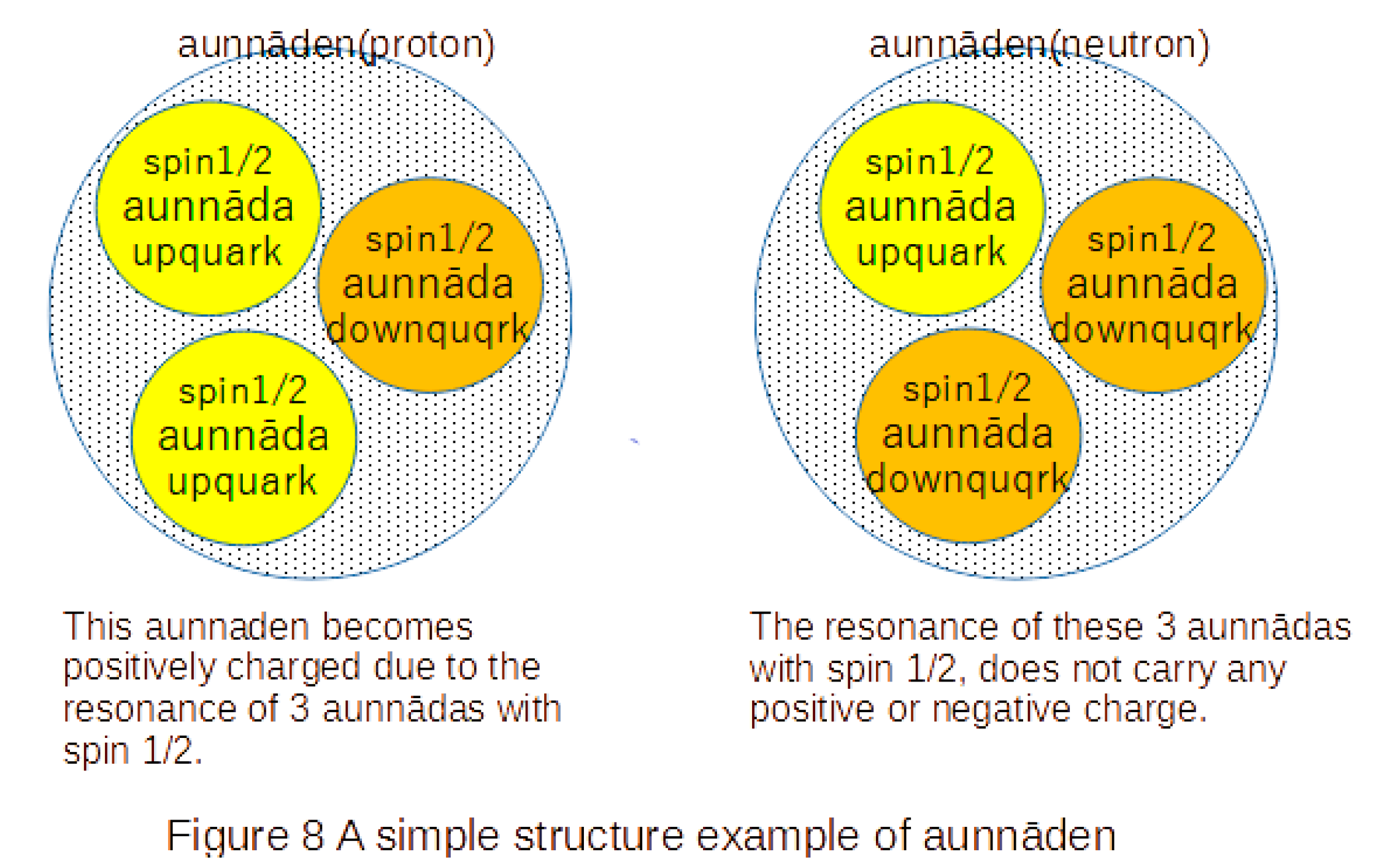

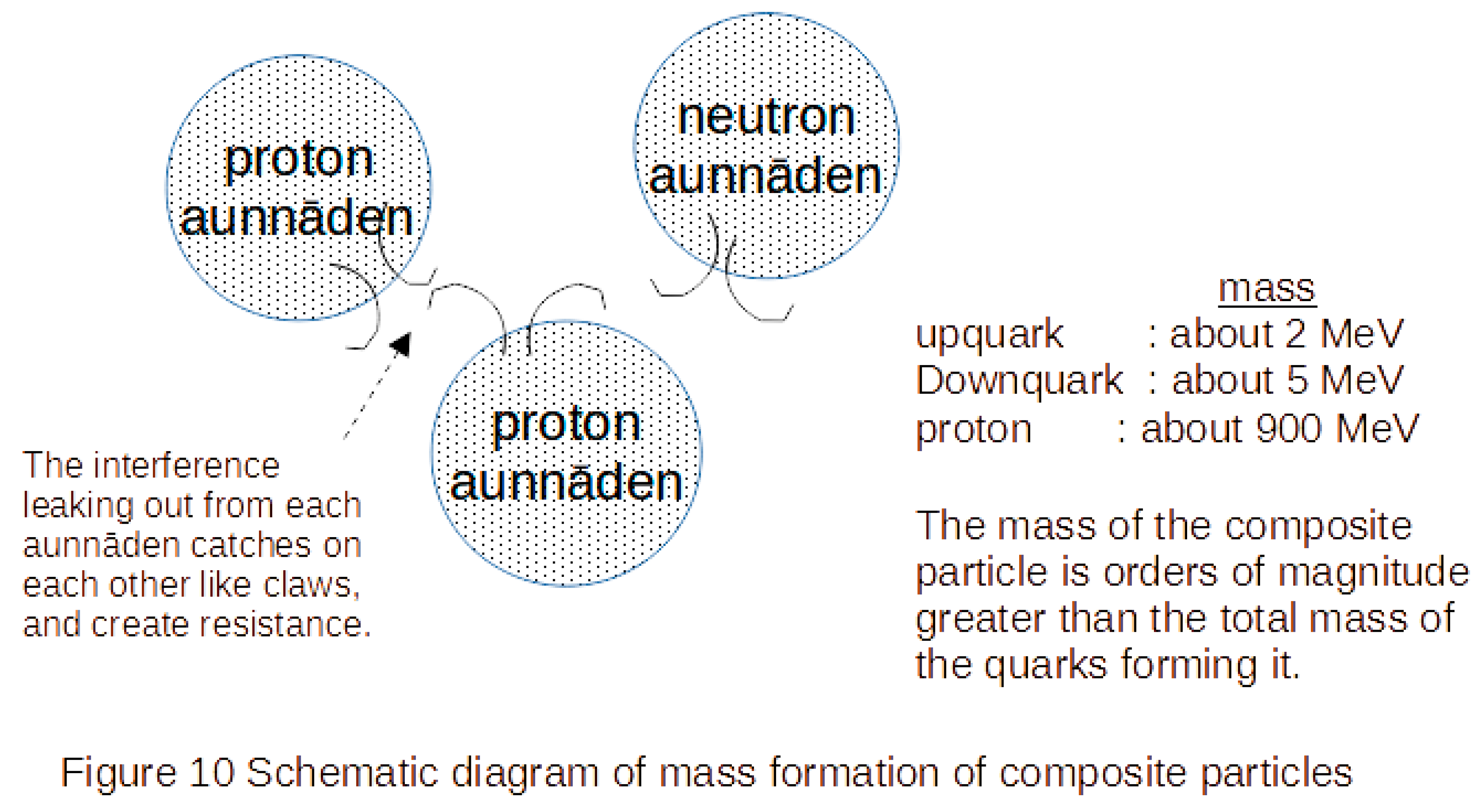

A higher-order resonance can occur not only among individual auns forming aunnāda, but also among multiple aunnāda themselves, giving rise to larger clusters we call aunnāden. These are not mere aggregates of aunnāda, but dynamic, structured fields shaped by the resonant coupling among those aunnāda.

An aunnāden is not a completely closed system; rather, it exists with “cavities” or “hollows”—open regions where resonance and interference with the external environment or with other aunnāden can take place. This openness in structure enables the transmission of information and forces, as well as the ability to bind with other aunnāden.

Composite particles such as protons and neutrons are prime examples of aunnāden. For instance, a proton is formed when the aunnāda clusters corresponding to two up quarks and one down quark resonate together into a single aunnāden. Within this aunnāden, the balance of forces generated by the mutual interference of spin orientations and vibrational deflection produces a stable, positively charged configuration—what we observe as a proton.

Similarly, a neutron arises when the aunnāda clusters corresponding to one up quark and two down quarks form a different specific resonance structure into aunnāden. Because its spin and vibration configuration differs, it carries no net charge and is a less stable aunnāden—reflected in the short free-neutron lifetime.

Thus, composite particles (aunnāden) are not simply combinations of multiple quarks (aunnāda), but entirely new structures emerging from the resonant interplay of those quark-like aunnāda. The stability, mass, and interaction behaviors of an aunnāden are determined by the network of spin, vibrational period, and vibration deflection angle among its constituent aunnāda.

Figure 8.

A simple structure example of aunnāden. Composite particles such as protons and neutrons are formed by multiple aunnāda resonances.

Figure 8.

A simple structure example of aunnāden. Composite particles such as protons and neutrons are formed by multiple aunnāda resonances.

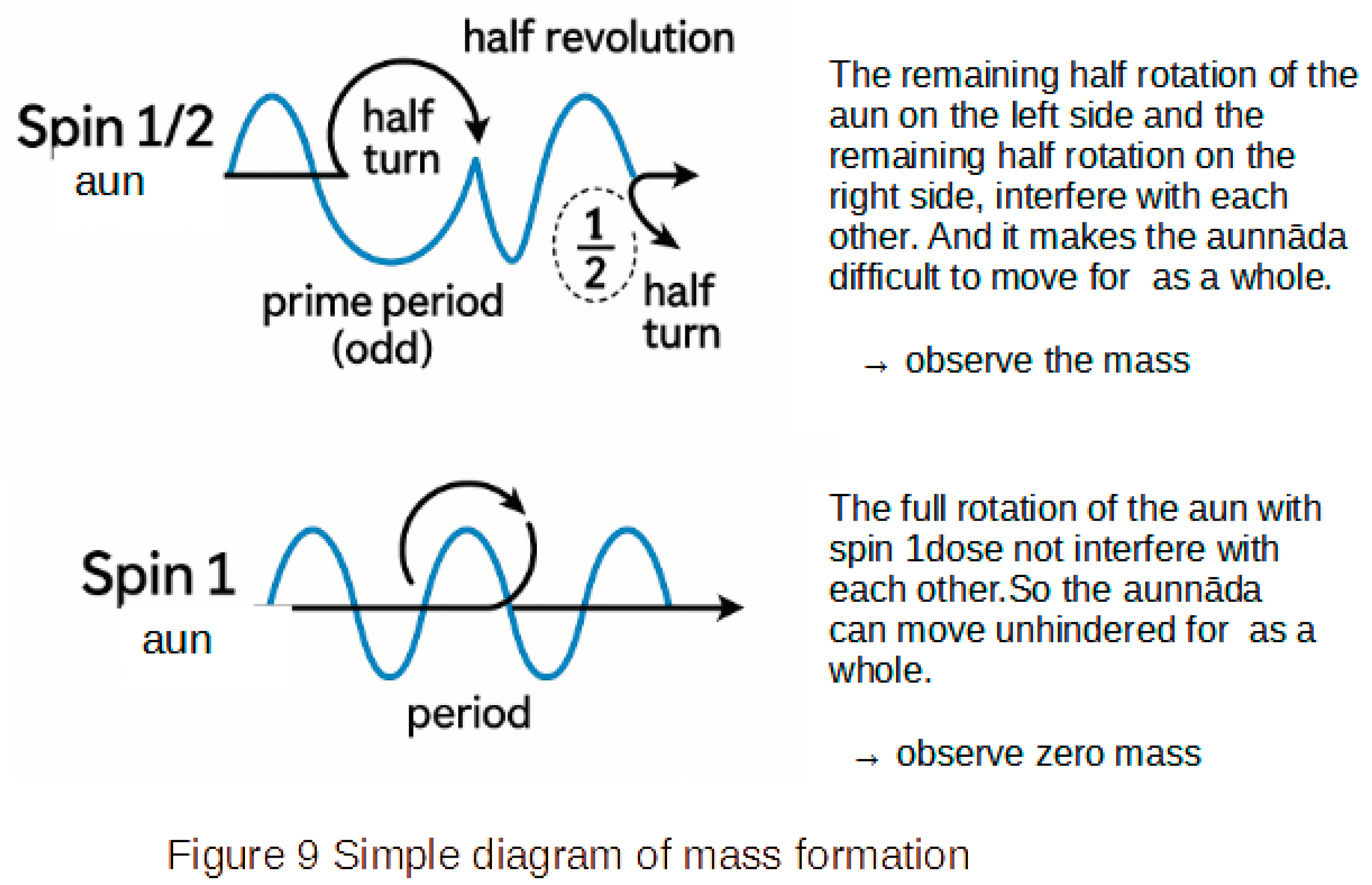

3.3. Mass

Mass is defined as resistance to motion. The mass of a material particle originates from the resonant networks formed among multiple aunnāda within a single aunnāden, and from the phase constraints that operate within these networks. Concretely, the strength of resonance and the structural coupling between aunnāda determine the degree of resistance to externally imposed changes in motion—this resistance is what we observe as mass.

A spin-1/2 aun does not complete a full rotation unless its vibration frequency is even. However, the aun that make up material particles vibrate at prime-numbered (i.e., odd) frequencies, which results in a residual half-spin at the aunnāda level. This residual half-spin causes aunnāda structures to interlock like hooks, interfering with one another and creating resistance.

Similarly, composite particles such as protons and neutrons (i.e., composite aunnāden) exhibit mass due to the interfering components that extend from individual aunnāden. These components interlock with other structures, generating resistance. Thus, the mass of protons and neutrons is determined by the resonance relationships between the constituent aunnāden and the coupling energies of their phase structures.In contrast, photons (light) are composed of spin-1 aun, which do not generate such resistance. As a result, they exhibit no “resistance to motion” and are observed to have zero mass.

This resonant and coupling mechanism may be interpreted as the foundational basis of phenomena described in the Standard Model as interactions with the Higgs field [

1,

4,

5] and the Higgs boson.

Figure 9.

Simple diagram of mass formation. The resistance of the aunnādas to hook each other due to the rest of the half rotation of the spin 1/2, creates a difficulty moving (mass) .

Figure 9.

Simple diagram of mass formation. The resistance of the aunnādas to hook each other due to the rest of the half rotation of the spin 1/2, creates a difficulty moving (mass) .

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of mass formation of composite particles. Composite particles such as protons and neutrons have difficulty moving (mass) due to interference that leaks out from the aunnāden.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of mass formation of composite particles. Composite particles such as protons and neutrons have difficulty moving (mass) due to interference that leaks out from the aunnāden.

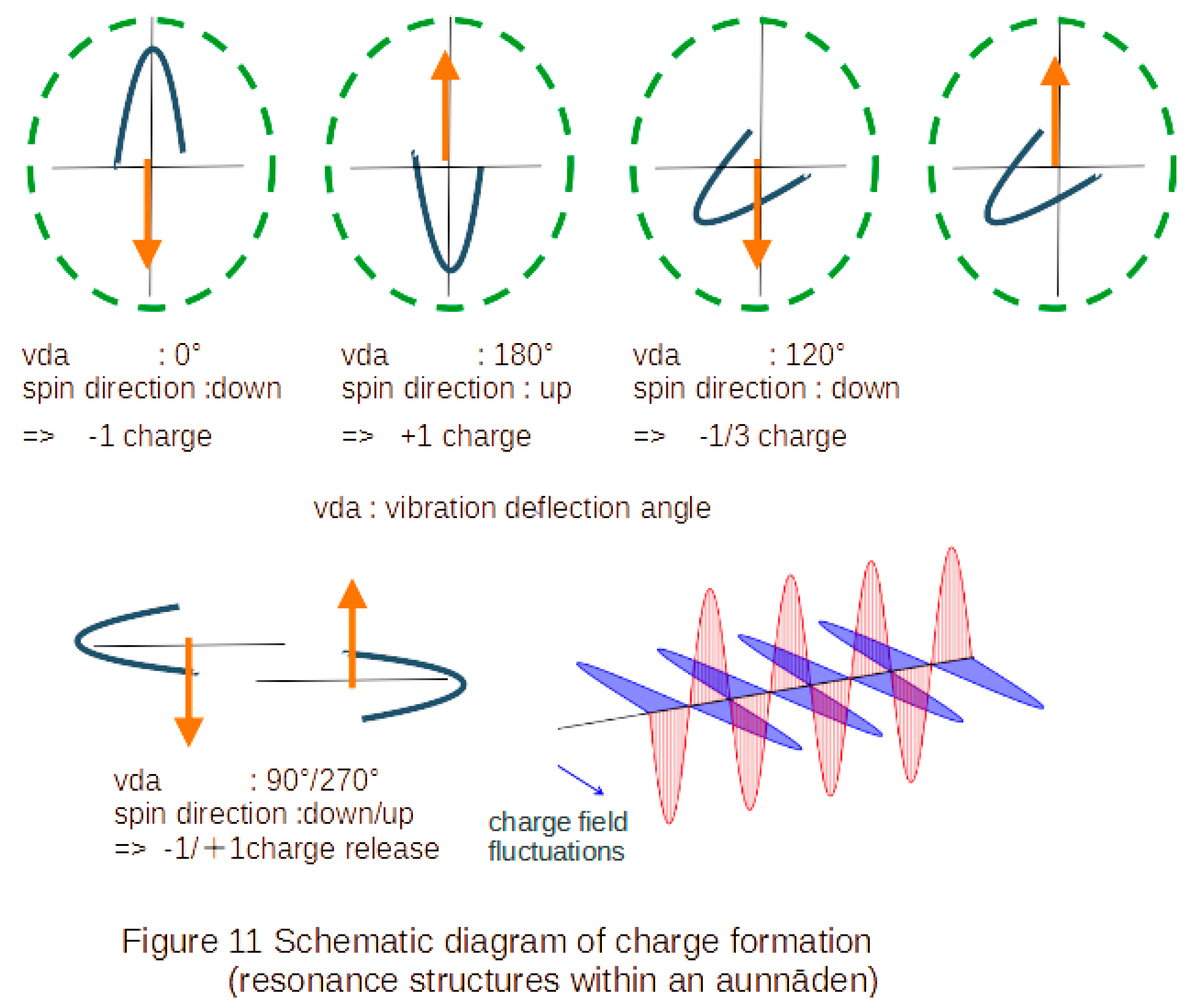

3.4. Electric Charge

When the aunnāda corresponding to an electron or quark is formed, a characteristic bias emerges within its resonant structure. This bias creates a directional difference—an asymmetry—in how that aunnāda resonates and interferes with surrounding aunnāda. We observe this asymmetry as electric charge.

- An electron’s aunnāda exhibits a “negative bias” in its resonance, causing it to interactwith its environment with negative deflection and be observed with a charge of –1.

- An up quark shows a similar bias directionally, but more weakly, leading to anobserved charge of +2/3.

- A down quark, due to a different structural configuration, exhibits the opposite biasand is observed with a charge of –1/3.

Thus, charge can be understood as the directional strength of resonance bias within an aunnāden formed by a cluster of aunnāda, manifesting in the way that cluster interferes with others.

In matter particles, this generated charge remains bound within the aunnāda (i.e., the particle carries that charge). In contrast, a photon does not confine its generated bias but releases it, giving rise to the electromagnetic fields (E and B) that propagate through space.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of charge formation. The charge is a manifestation of the bias of the aunnāden structure that the aunnāda group forms by resonance. .

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of charge formation. The charge is a manifestation of the bias of the aunnāden structure that the aunnāda group forms by resonance. .

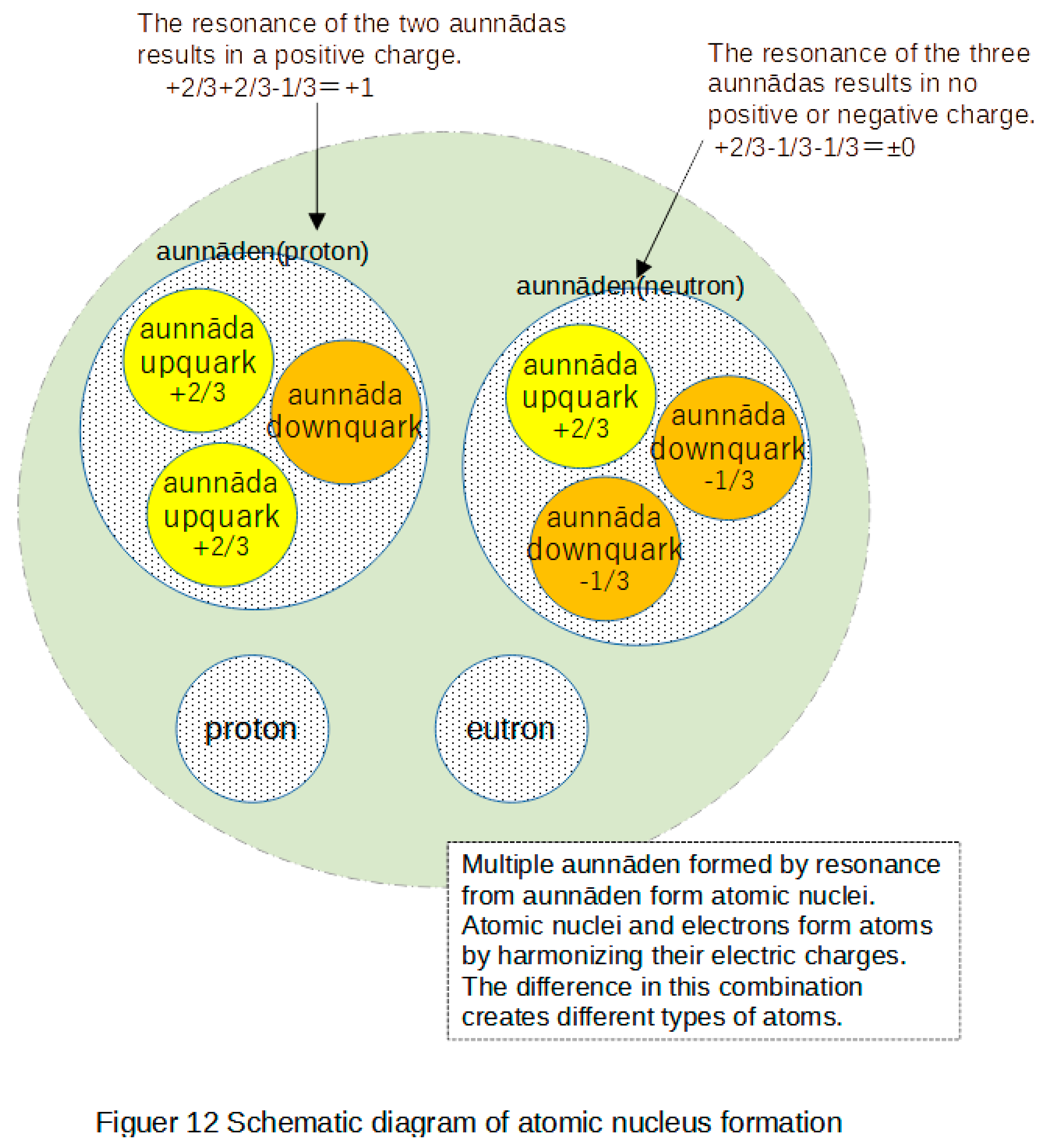

3.5. Atoms

An atom is a structure in which several aunnāden form a stable resonant network. Protons, neutrons, and electrons are each composed of specific aunnāden, which are themselves formed from particular configurations of aunnāda. When these aunnāden resonate with each other in a spatially and phase-wise ordered manner, they manifest as a cohesive entity—a structure we observe as an atom.

Moreover, the positive charge carried by the aunnāden of the atomic nucleus and the negative charge of the electron’s aunnāden attract each other, further stabilizing the resonant network and establishing the atomic structure. This balance of positive and negative charge can also be understood as a resonance balance among aunnāden.

Protons and neutrons are aunnāden bound together by strong resonant coupling within the atomic nucleus. The periodicity and resonant skew of their constituent aunnāda are intricately interwoven.Electrons, though spatially distant from the nucleus, maintain their orbital positions through periodic resonance with the nucleus. This is not interpreted in terms of conventional “position and motion,” but rather as a balance of phase-shifted vibrations between aunnāda structures. The atom is a state in which such aunnāden sustain a resonant network that can be observed—and it is this stability that forms the core of a material’s “existence.”

Thus, the atom is no longer merely a collection of aunnāda or aunnāden, but the manifestation of these components resonating in a specific, ordered way to create an observable structure with distinct properties. In other words, the atom represents a culmination of the hierarchical expression of resonance, ultimately originating from the fundamental entity: the aun.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of atomic nucleus formation, An atom is a stable state in which resonance networks are maintained between the aunnāden.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of atomic nucleus formation, An atom is a stable state in which resonance networks are maintained between the aunnāden.

3.6. Quantum Superposition

When we observe a quantum system, what actually happens is that we register the state of one particular aun within the aunnāda being measured. In that moment, the entire aunnāda appears as if it were in that single state, corresponding to the familiar notion of “collapse” of the superposition upon measurement.

In reality, an aunnāda is a cluster of many auns resonating in complex patterns, each with its own spin, vibrational period, and deflection angle. An observation merely selects one of those aun’s resonant states. The instant one aun’s state is picked out, the resonance network of the other auns is drawn into alignment with that chosen state, making the whole cluster appear to have been in that state all along.

As is well known from interference experiments, when no measurement is made, the aunnāda exists as a superposition of multiple resonant states—these different states coexist within the resonance network. However, upon measurement, that network converges into a single direction, and the resonances corresponding to the other states are temporarily lost. As a result, the interference pattern disappears, and one sees “only one outcome.”

Once the observation is ended, the aunnāda regains its full spectrum of resonant states. The various auns, each with its own phase, spin, and period, re-establish their network of interference, and the superposition—and the possibility of observing interference fringes—returns.

In the aunnāda model, quantum superposition is thus understood as the simultaneous presence of multiple resonant structures (multiple auns) within an aunnāda, and a measurement is simply the temporary act of selecting one of those structures.

3.7. Quantum Entanglement

When an aunnāda is formed, it is always accompanied by the simultaneous generation of another aunnāda that is structurally symmetric to it in terms of spin and vibrational deflection angle. These two aunnāda are structurally linked, forming a pair with resonant symmetry.

A simplified example of such paired aunnāda can be expressed as follows:

aunnāda “AN1” aunnāda “AN2”

aun11 (spin ↑, vda +φ₁) aun21 (spin ↓, vda −φ₁)

aun12 (spin ↑, vda +φ₂) aun22 (spin ↓, vda −φ₂)

aun13 (spin ↓, vda +φ₃) aun23 (spin ↑, vda −φ₃)

aun14 (spin ↑, vda +φ₄) aun24 (spin ↓, vda −φ₄)

aun15 (spin ↓, vda +φ₅) aun25 (spin ↑, vda −φ₅)

aun16 (spin ↑, vda +φ₃) aun26 (spin ↓, vda −φ₃)

⋮ ⋮

vda : vibration deflection angle

As shown here, each aun in the pair exhibits perfect mirror symmetry with its counterpart in both spin orientation and vibrational deflection angle. When either of these two aunnāda undergoes “observation” or interacts with another structure—causing its structure to collapse (i.e., a definitive state is determined)—the resonant network forces the counterpart to simultaneously collapse in a structurally correlated manner.This phenomenon corresponds to what is observed as quantum entanglement [

6]. In the aunnāda model, entanglement is not an inexplicable nonlocality, but rather a structurally induced resonance-linked symmetry effect.Thus, even when spatially separated, the originally co-generated pair of aunnāda retains a resonant connection that draws their state determinations into mutual correspondence. What appears in quantum theory as “nonlocal influence” can be interpreted as a natural consequence of their entangled resonant structure.

3.8. Mechanism of Force Generation: Resonant Structural Binding

In the aunnāda model, “forces” are not understood as arising from the exchange of mediating particles within a field, but rather as structural phenomena emerging from the resonant synchronization and subsequent branching or interference among aunnāda.

Specifically, when the spin periods and vibrational vda between multiple aunnāda become resonantly matched, they form a synchronized field—a resonant field—which serves as the basis for the “binding” between quantum particles.This web of resonant synchronization gives rise to coupling, and the resulting “shapes” or patterns of such connections appear to observers as illusory field quanta—such as gluons or photons.

These “illusory quanta” (phantom quanta) are not physical particles in the conventional sense, but rather the completed patterns of synchronization and interference left behind by the oscillatory structures of aunnāda across space. They are manifestations of structural transitions and branching points, temporarily formed during structural propagation.

From this perspective, we can reinterpret fundamental forces as follows:

- Strong Force: Coupling through high-density local resonance among aunnāda

-Electromagnetic Force: Long-range interference patterns formed by synchronization of deflection angle and spin direction

-Weak Force: Branching structures arising from divergence or near-collapse of synchronization

Thus, the diverse natures of the fundamental forces, traditionally treated separately, can be unified within the aunnāda model as various expressions of resonant synchronization and its structural breakdown.

In this view, “force” is not mediated by substantial particles, but rather exists as a network of synchronized structural motion among aunnāda. The universe is not filled with “force fields,” but with resonant fields—an intricate mesh of structural harmonics.

3.9. Photon Excitation

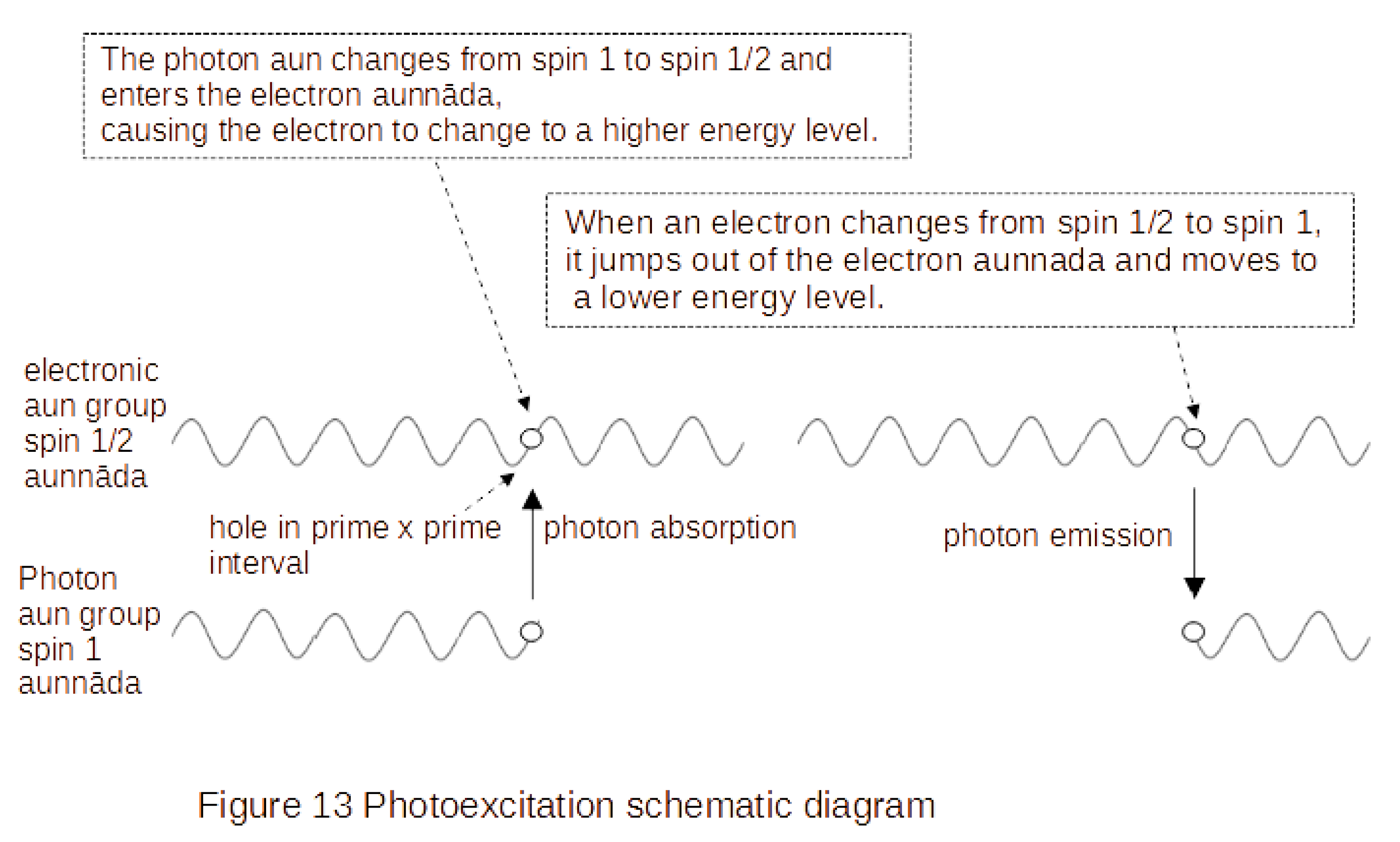

Photons (spin-1) and material particles (spin-1/2) are composed of aun, but they do not align with each other in terms of periodicity or phase. However, when the overall wave pattern (i.e., energy quantum) formed by a group of photon-aun matches, in phase, with a specific substructure within an electron-aunnāda, an interaction arises not in the form of “interference” but as excitation. This interaction does not result in mass acquisition through resonance, but rather in discrete energy transfer.

Because spin-1 aun generally do not integrate into typical aunnāda structures, they propagate linearly unless a specific “hole” (a phase-aligned window based on prime-periodic structure) exists within the electron-aunnāda. In such rare cases, the photon may momentarily “reside” in that space, allowing energy exchange to occur.

From the viewpoint of aun-based structure, the integer spin rotation of light aligns only momentarily with the half-integer phase displacement of electron aunnāda. This fleeting alignment is what leads to excitation—i.e., the phenomenon where an electron absorbs a photon and transitions to a higher energy state. In other words, spin-1 aun (photons) and spin-1/2 aun (matter particles) do not exhibit continuous resonance, but they do have discrete points of phase alignment. These are the origins of discrete excitation phenomena.

The quantized nature of energy levels and the “quantum jump” of electrons are fundamentally explained by the rare coincidences between prime-numbered periodicities of aun and the twisted structure of spin-1/2 states. This framework provides a foundational explanation for the discrete stationary solutions in the Schrödinger [

1] equation.

Figure 13.

Photoexcitation schematic diagram. Spin 1 aun enters the matching window of a specific phase inside the electron aunnāda and an energy exchange occurs.

Figure 13.

Photoexcitation schematic diagram. Spin 1 aun enters the matching window of a specific phase inside the electron aunnāda and an energy exchange occurs.

3.10. Vacuum

In conventional physics, “vacuum” has been defined as a region of space devoid of particles or matter. In quantum theory, however, it is not merely an empty space, but a state in which various phenomena such as quantum fluctuations and virtual particle–antiparticle pair creation occur.

In the aunnāda model, vacuum is defined as a state in which auns exist but do not form any resonant structures (aunnāda). In other words, vacuum is a “field of unresonated auns,” where auns are present but not organized into any structure.

These auns, although possessing attributes such as spin, vibration period, and vibration deflection angle, lack periodic coherence, phase alignment, and directional correspondence with other auns. Consequently, they do not belong to any aunnāda and do not manifest as observable particles or forces. Thus, they appear as “emptiness” from an observational standpoint.

In this sense, vacuum is not “nothing,” but rather “a state in which no structure is formed.” It is always filled with the potential for resonance, and when the conditions for forming aunnāda structures are satisfied, they can emerge as observable matter, energy, or fields.

3.11. Heat

Heat, in the aunnāda model, is an observable result of interference between structures at or above the level of aunnāden. It arises from the resonant effects that leak from the internal structures of aunnāda and aunnāden. Therefore, without such higher-order structures, heat does not occur or propagate, which is why heat transmission does not take place in a vacuum.

A question arises: why is there no defined upper limit to temperature, but there exists a universally defined lower limit—absolute zero?

Absolute zero, in this model, is understood as the state in which there is no interference arising from the resonant effects of aunnāda and aunnāden. It corresponds to a condition in which no unresonated auns exist, and all auns have reached complete structural resonance.

Accordingly, absolute zero does not signify the complete disappearance of energy, but rather the disappearance of non-resonance—that is, the attainment of full resonance. It represents a structural extreme in which no diffusive disorder remains.

4. Conclusion

The source is not complex—it is simple. Complexity at the origin would increase the likelihood of disruptions in the multi-layered and diverse unfolding of existence.

The spin and vibration of the “aun” connect and synchronize to form the “aunnāda” The unique pattern of this spin and vibration gives birth to the “aunnāden”, distance, time, and space, which in turn form the universe.

This aunnāden also has an aspect as a “resonant structure field” that can integrate multiple forces (electromagnetic force, strong force, and weak force), which opens the way to an interpretation of a hierarchical structure that goes beyond the quark model.

In this vision, the universe is not composed of “hidden rhythms of being,” but rather resembles a continuous, resonant music—an ever-unfolding orchestration of vibrational patterns and sustained connectivity.

Equations such as the Schrödinger [

1] and Maxwell [

2] equations are macro-scale projections of resonance between deflection angle and spin within the aunnāda framework.A photon is no longer just a particle, but an image of two orthogonal structures propagating through space in synchronized motion.

At the foundation, the aun spins, vibrates with prime-number periods, and resonates in exacting order. There is no true randomness—only perfect harmony and mathematical structure.

Traditionally, physics posits that mass exists first, giving rise to gravity (attraction). However, in this model, aunnāden form resonant structures that create spatially cohesive configurations, resulting in “resistance to movement” (inertia). This resistance is observed as “mass.” Thus, it is not that “mass causes attraction,” but rather that “attraction leads to resistance to movement (observed as mass).”

At the time of the Big Bang, innumerable aun—each with differing spin, vibrational period, and vibration deflection angle —were dispersed from a compressed state. Through resonance, various aunnāda were formed.Further resonances between these aunnāda led to the emergence of spacetime, particles, forces, and subsequently atoms, molecules, amino acids, proteins, and life forms.

One day, this resonance will collapse, re-condensing into a mass of aun, which may again explode through a new Big Bang, scattering aun to form yet new aunnāda, giving rise to a different universe.

Some human beings recognize that “only humans have minds and think, only humans...” and boast that we have “surpassed the realm of God by unraveling the depths of the universe, and by unraveling life through DNA.” The human life form is also a temporary form of the diversity of the space-time universe that originates from aun and aunnāda.

In response to the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics, Einstein stated that “God does not play dice.” and believed that the universe is governed by strict laws, not by chance. From the perspective of this model, it can be considered that humans, as observers, perceive the universe, which is based on fundamental harmony and order, as a probabilistic phenomenon.

Einstein is right: “It is the observer, humans, who play the dice.”

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of the entire aunnāda model. From the source aun, aunnāda such as quarks and electrons were formed, and then atoms, organic and inorganic matter, life forms and celestial bodies were formed.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of the entire aunnāda model. From the source aun, aunnāda such as quarks and electrons were formed, and then atoms, organic and inorganic matter, life forms and celestial bodies were formed.

Appendix 1: The Meaning Behind the Term “Aun”

The name “aun” carries with it the following intentions:

- Primordiality- A resonance of softness and tension in its phonetic sound- A sense of completeness as a word

Although an alternative spelling such as “aunn” (doubling the ‘n’) is possible in romanized form, this paper adopts the three-letter form “aun”, as it embodies the minimalism and elegance of origin more purely.

Appendix 2: On “Nāda”

The word “nāda” comes from Sanskrit, where it means “sound,” “resonance,” or “vibration.” In many Eastern philosophical and spiritual traditions, nāda is not merely a physical sound, but a symbol of the primordial vibration or energy of the universe.

It represents a fundamental concept that transcends the audible, carrying profound meaning in both physical and philosophical or spiritual dimensions.

It refers to the cosmic resonance from which all forms and energies arise—a concept deeply aligned with the aunnāda model’s view of vibrational origins.

Appendix 3: The Imaginary Unit i, Napier’s Constant e, π, and ∞

We are often taught these concepts in a simplified manner as follows:

i: An imaginary number, introduced to solve the equation x^2 + 1 = 0, and considered to be non-existent in the real world.

e: The base of the natural logarithm y=log(x)y = \log(x)y=log(x), appearing universally in phenomena such as differentiation, exponentiation, growth, and decay — a mathematical constant.

π: The ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter — another fundamental mathematical constant.

∞ (infinity): A concept indicating an unbounded or limitless state, playing an essential role in areas such as infinite series, infinitesimals, and infinite sets.

However, these numbers and concepts are essentially formed from the resonance structures of aun and aunnāda.

When two constituent auns resonate, they can generate both positive and negative charges. This gives rise to multiplicative results such as 1×1=1 and 1×1=−1, indicating the essential nature of the imaginary unit i.

The propagation of vibrations and resonances of auns — which are “infinite” in number — through interactions with others to form aunnāda represents a self-expanding structure: “one generates one, which in turn generates the next resonance...”This expansion manifests exponentially, and the natural growth form stabilizes into the form (expanding radix)^x. The radix of this expansion naturally arises from the structural dynamics of aunnāda itself and represents the foundational law of the universe’s self-developing nature.We refer to this base as e, or Napier’s constant.

The “shape” of both aunnāda and aunnāden is circular or spherical. When we define the ratio within these circular forms as π, the curvature and periodicity of spatial structures develop in accordance with π. In our mathematical descriptions, we use π as a constant in formulas such as trigonometric functions (sin, cos).

Infinity, as in the case of Taylor expansions for trigonometric and exponential functions, indicates how individual random motions or forms converge into essential and simple functions through infinite summation. It symbolizes the simplification and unification of seemingly complex dynamics.

But why is it that phenomena such as “doubling” appear to follow integer sequences like 1, 2, 4, 8, etc., while e is a transcendental number?Why are basic shapes like triangles and rectangles describable by algebraic numbers, yet π is transcendental?This is because e and π arise from foundational ratios and constants generated by the resonance of auns across “infinity”. They are not finite or reducible entities, but expressions of fundamental, boundless processes — hence their transcendence.

Nevertheless, although the number of auns approaches infinity, it is not truly infinite. This implies that the spacetime of our universe is not something that expands eternally or endlessly — a key insight into its true nature.

Appendix 4: Physics and Mathematics

The equations we use — the constants such as π, e, i, and ∞ — as well as the formal systems of calculus and geometric space, all reflect the intrinsic order and harmony that emerge from the resonance structures of spinning auns vibrating with prime-numbered periods, i.e., from aunnāda.

These are not abstract tools that humans created afterward to describe the structure of aunnāda. Rather, physics and mathematics are manifestations of the structural development of aunnāda itself. The forms and constants of mathematics are expressions that arise naturally from the unfolding of aunnāda. Human language and logic have only followed and recognized them retrospectively.

Appendix 5: Intelligence and the Formation of Neural Networks

The formation and function of neural networks in our brains are based on the resonance structures of aun and aunnāda. The connections between neurons, the propagation of signals, and synchronized firing patterns are constructed upon resonance relationships formed by the prime-period vibrations of a vast — nearly infinite — number of auns.

Based on this self-expanding, proliferating, and evolving resonance structure of aunnāda, neurons form complex, multilayered, and multiscale networks. This leads to the amplification of information, the integration of memory, and the emergence of thought — phenomena that we refer to collectively as “intelligence.”

In other words, intelligence is the field of resonance that becomes possible when aunnāda-like structures develop within the brain. Our thinking and logic, and even intuition and creativity, can be understood as self-resonating and self-expanding phenomena of aunnāda that structurally mirror the architecture of the universe.

Human intelligence is thus a resonance — a reflection — of the universe’s source structure. This is why human beings can recognize and unravel the nature of the universe.

Appendix 6: Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is the process in which the aunnāda of light — solar photons — is resonantly absorbed by the highly complex aunnāden structures within plant chlorophyll and other pigment-protein molecules. These molecules, through their electronic bonding configurations (i.e., chemical aunnāda), resonate with the aunnāda of light.

What occurs here is not merely energy absorption. Rather, it is the integration of the photonic aunnāda into the internal aunnāda structure of matter, initiating a restructuring of electronic bonds — a chemical reaction.

The light does not disappear. Instead, its aun-based composition is incorporated into a new aunnāda structure, leading to the formation of molecules and energy carriers (such as ATP). This is, in essence, a reconfiguration of the fundamental aun vibration within a complex resonance field of aunnāda.

Thus, photosynthesis is a re-resonance process of aunnāda, representing one form of the universe’s resonant evolution.