1. Introduction

Medicinal crops are most often grown on small areas around the world and as such are classified as minor crops. The areas under cultivated medicinal, aromatic and spicy plants in Serbia vary from 2,000-3,000 ha per year (<0.15% arable lands), with 20-25 species being cultivated the most: chamomile, peppermint, fennel, lemon balm, ribwort plantain, thyme, marshmallow, parsley, marigold, dill, basil, oregano, etc. [

1]. Medicinal crop production has an important and beneficial role in the economic, social, cultural and ecological aspects of human communities in the worldwide. Those so-called minor crops in Serbia , which are typically cultivated on small farms averaging less than 0.3 ha per plot, can help smallholder farmers directly improve their livelihoods by generating income through trade and by contributing to health-related industries [

2,

3]. Also, the production of medicinal crops is a benefit for everyone, whether those herbs are used as food, in hygiene, personal care, in folk medicine, etc. [

4].

As with conventional field crops, various constraints pose serious problem for the cultivation of medicinal crops, among which weeds are particularly significant. According to the definition adopted by the European Weed Research Society "Weeds are any plant or vegetation, excluding fungi, that interferes with the objectives or requirements of people". Similarly, the Weed Science Society of America defines a weed as ”a plant growing where it is not desired”. Unlike plant pathogens and pests, weed species represent a permanent and major challenge in the cultivation of medicinal crops. It is generally estimated that weeds cause yield losses of about 10% in developed countries and up to 25% in less developed countries in conventional crop production [

5]. Further, Kashem et al. [

6] estimate that unmanaged weed growth during the early stages of crop establishment can reduce yields by 25% to 80%. Globally, it is estimated that approximately 1,800 weed species are responsible for a 31.5% decline in crop production, causing annual economic losses of about 32 billion USD [

7]. However, there are still limited studies on weed diversity and their harmfulness in medicinal crop production systems [8-10]. The abundance and composition of weed species in medicinal crops, in addition to the type of crop and cultivation practices, largely depend on the soil type and quality, as well as on climatic and meteorological conditions in a given season [11-13].

The harmfulness of weeds in different crops is reflected in their ability to successfully compete with cultivated plants for natural resources such as light, nutrients, water, and space. Weeds negatively impact both the quantity and quality of crop yield, increase crop production costs due to the necessity of weed control measures, and can serve as hosts to numerous plant pests and diseases [14, 15]. Globally, approximately 1,570 weed species have been identified [

16], with more recent estimates suggesting around 1,800 species [

7]. In Serbia, about 300 weed species have been confirmed in crop fields, while the total number of weed species, including those in non-crop areas, is estimated at around 1,000 species [

17]. However, there are still limited studies addressing weed diversity and their harmfulness specifically in medicinal plant production systems [9, 10]. Interestingly, weed-induced stress conditions may even enhance the synthesis of biologically active secondary metabolites in medicinal plants [

18]. In addition, some weed species such as

Adonis aestivalis,

Aristolochia clematitis,

Cirsium arvense,

Carduus spp.,

Conium maculatum,

Datura stramonium,

Lolium temulentum,

Solanum nigrum, can cause significant problems during mechanized harvesting, potentially contaminating the harvested agricultural or medicinal plants [19, 20].

The reasons for weed control in medicinal crops are numerous: increasing crop productivity, enhancing product quality, reducing production costs, limiting the spread of other pests, improving animal health, supporting human activities, reducing impacts on transportation, and minimizing health risks. However, the primary reason for weed management in medicinal crops remains the prevention of yield and quality losses. A fundamental prerequisite for timely and effective weed control in medicinal crops is precise knowledge of weed species composition and their abundance in the fields. Detailed information on weed density, frequency, and community structure is essential for predicting potential yield losses and for defining cost-effective weed management thresholds [

21].

Therefore, the aim of this research was to conduct a multi-year floristic survey across different seasons and years in order to provide reliable data on weed biodiversity and abundance, as a solid starting point for the development of an effective weed management strategy in medicinal crop plantations in Serbia. The data obtained can now be used to identify major weed problems that require targeted research or the implementation of improved weed management practices.

2. Materials and Methods

Study area. The analysis of weed flora diversity of selected medicinal crops, lemon balm (

Melissa officinalis L.), fennel (

Foeniculum vulgare Mill.), peppermint (

Mentha piperita L.), ribwort plantain (

Plantago lanceolata L.), and German chamomile (

Chamomilla recutita L.), was conducted between 2019 and 2024 on commercial farms of Institute for Medicinal Plant Research "Dr Josif Pančić" located in Pančevo, South Banat, Republic of Serbia, Southeast Europe (44°52’20.0"N, 20°42’04.7"E). The research was based on the agro-phytosociological method, according to Braun-Blanquet [

22].

Basic data on crop characteristics (i.e. life cycle, crop type, sowing time, seeding rate, and harvest period) are provided in

Table 1. In these fields, medicinal crops are traditionally grown in crop rotation with small grain cereals.

The soil type was chernozem, containing 2.3% humus and 0.19% total nitrogen while the available phosphorus (P2O5) and potassium (K2O), extracted using ammonium lactate method, were 36 mg kg−1 and 362 mg kg−1, respectively. Fertilizer was applied three times per growing season, adapted to soil nutrient status. The first fertilization was carried out following the deep autumn plowing using a solid NPK mineral fertilizer (NPK 15–15–15) at rate 0.6 t ha−1. The subsequent two fertilizations were performed with calcium ammonium nitrate (KAN, 27% N) at rate of 0.2 t ha−1. The first KAN application was performed in early spring, after the development of two to four true leaves in all studied species. The timing of the second KAN application varied depending on the crop. In lemon balm and peppermint, the second application was carried out immediately after the first harvest to support regrowth and ensure sufficient nutrient availability for the subsequent growth cycle. In fennel and ribwort plantain, typically harvested once, the second application was made during peak vegetative growth, about 4–6 weeks after the initial fertilization and prior to flowering. In German chamomile, the second KAN application was timed at the beginning of the flowering stage to promote optimal flower development and essential oil yield.

Meteorological data, including average monthly temperatures and precipitation amounts for the period 2019–2024, were obtained from the local Meteorological Stations of the Republic of Serbia for the Pančevo locality (

Table 2). According to these data, weather conditions varied notably between seasons and years. Generally, July or August were the warmest months with average temperatures ranging from 23.7 to 26.9 °C, while January was typically the coldest month, with averages between 0.8 and 5.7 °C. Precipitation patterns showed no consistent seasonal regularity throughout the study period; however, the highest precipitation occurred in June 2020 (158.5 mm) or December 2021 (157.8 mm), depending on the year.

Survey of weed diversity and abundance. The qualitative and quantitative evaluation of weed flora was conducted over six years each spring, following crop emergence and prior to any weed management measures, on chamomile (18 plots), ribwort plantain (11), peppermint (10), fennel (10), and lemon balm (10). Each plot measured approximately 0.50 ha. Plant species abundance and coverage were assessed using the scale by Westhoff and van der Maarel [

23], while weed frequency was calculated following Braun-Blanquet [

22] principles, and expressed on a scale from I to V, where I indicates presence in 1–20% of plots, II in 21–40%, III in 41–60%, IV in 61–80%, and V in 81–100%. The vouchers of weed species were collected and are kept in the Laboratory of Botany and Laboratory of Weed Science at the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Belgrade. Species nomenclature was standardized according to Euro+Med PlantBase [

24].

Data analysis. Each plant species was classified by its life form according to Raunkiaer [

25] as annuals (therophytes, T), biennials (thero-hemicryptophytes, TH), and perennials, with the latter group including geophytes (G), hemicryptophytes (H), chamaephytes (Ch), and phanerophytes (P). Diagnostic species (Dg) for each group were identified using JUICE 7.1 software, with the phi coefficient as a measure of fidelity [26, 27]. Species with phi coefficient values greater than 0.15 were considered diagnostic. Species with a cover exceeding 25% and present in at least 50% of the total plots were considered dominant (Dm) in each group, while species occurring in at least 50% of the total plots were classified as constant (C).

To assess the influence of environmental factors on the weed species composition across different communities, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was applied using the JUICE 7.1 software, the R-project platform [

28], and the vegan package [

29]. Species cover was changed into percentages and transformed using the Hellinger transformation [

30]. For ecological gradient analysis, Ecological indicator values (EIVs) according to Pignatti [

31] were used. Mean unweighted EIVs for light, continentality, temperature, nutrients, moisture, and soil reaction were used in NMDS as passively projected explanatory variables.

3. Results

3.1. Weed flora

We confirmed presence of 109 distinct weed species across 59 plots of five different medicinal crops, including 75 annuals and 34 perennials. The weed flora comprised 93 broadleaved species, 10 grasses, and 1 parasitic species. These species belonged to 29 families and 88 genera. Among the families, Asteraceae had the highest number of weed species (26), followed by Poaceae (10), Brassicaceae (7), Fabaceae (7), Polygonaceae (6), Apiaceae (4), Caryophyllaceae (4), Chenopodiaceae (4), Lamiaceae (4), Scrophulariaceae (4), Solonaceae (3), Boraginaceae (3), Geraniaceae (3), Plantaginaceae (3), Malvaceae (3), Amaranthaceae (2), Convolvulacae (2), Ranunculaceae (2), Rosaceae (2), and ten families represented by a single species (

Table 3).

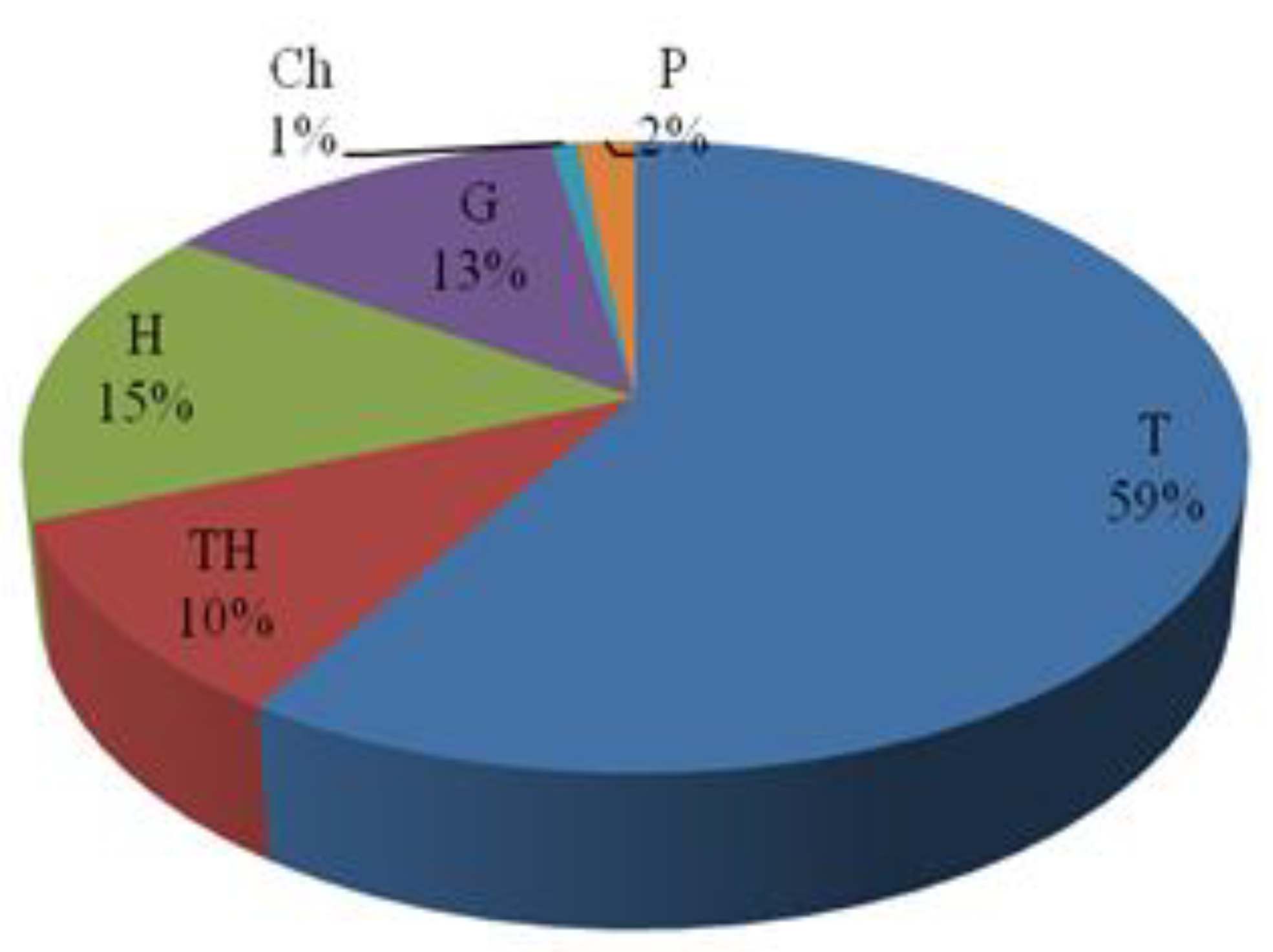

Biological spectrum of life forms in the weed communities of medicinal crops was dominated by therophytes (T=64), followed by thero-hemicryptophytes (TH=11), hemicryptophytes (H=17), geophytes (G=14), while chamaephytes (Ch) and phanerophytes (P) were represented by 1 and 2 species, respectively (

Figure 1).

All surveyed plots of medicinal crops contained perennial weed species, including Elymus repens, Artemisia vulgaris, Cirsium arvense, Convolvulus arvensis, Lepidium draba, Rumex crispus, Sonchus arvensis, Sorghum halepense, and Taraxacum officinale, among others. These perennials are particularly problematic due to their persistence and difficulty of control. Most of these species reproduce vegetatively through underground organs such as rhizomes, roots and root shoots, complicating soil cultivation practices.

In addition to perennials, a significant number of annual weeds were present with high abundance and frequency, including

Amaranthus retroflexus (abundance 2–7; frequency I–IV),

Chenopodium album (ab. 1–7; fr. II–IV),

Galium aparine (ab. 2–5; fr. II–IV),

Lactuca serriola (ab. 1–7; fr. II–IV),

Lamium amplexicaule (ab. 2–8; fr. III–IV),

L. purpureum (ab. 2–9; fr. III–IV),

Papaver rhoeas (ab. 1–9; fr. I–V),

Stellaria media (ab. 1–8; fr. III–V),

Veronica hederifolia (ab. 2–9; fr. III–V),

V. persica (ab. 2–9; fr. III–V), etc. (

Table 3).

In addition to typical weeds, volunteer medicinal crops frequently emerged as weeds within the plantation fields. For example,

Foeniculum vulgare was often found in ribwort plantain plots,

Cynara cardunculus appeared in fennel plots, and

Linum usitatissimum was commonly present in fennel, peppermint and ribwort plantain plots. Moreover, overall weed flora of medicinal crops showed a high abundance of alien invasive species, notably

Ambrosia artemisiifolia (ab. 1–9) and

Ailanthus altissima (ab. 2). The presence of weed species known for their high toxicity in vegetative and generative organs was also confirmed, including members of the Solanaceae (

Datura stramonim,

Solanum nigrum,

S. dulcamara) and Apiaceae family (

Bifora radians,

Conium maculatum) (

Table 3).

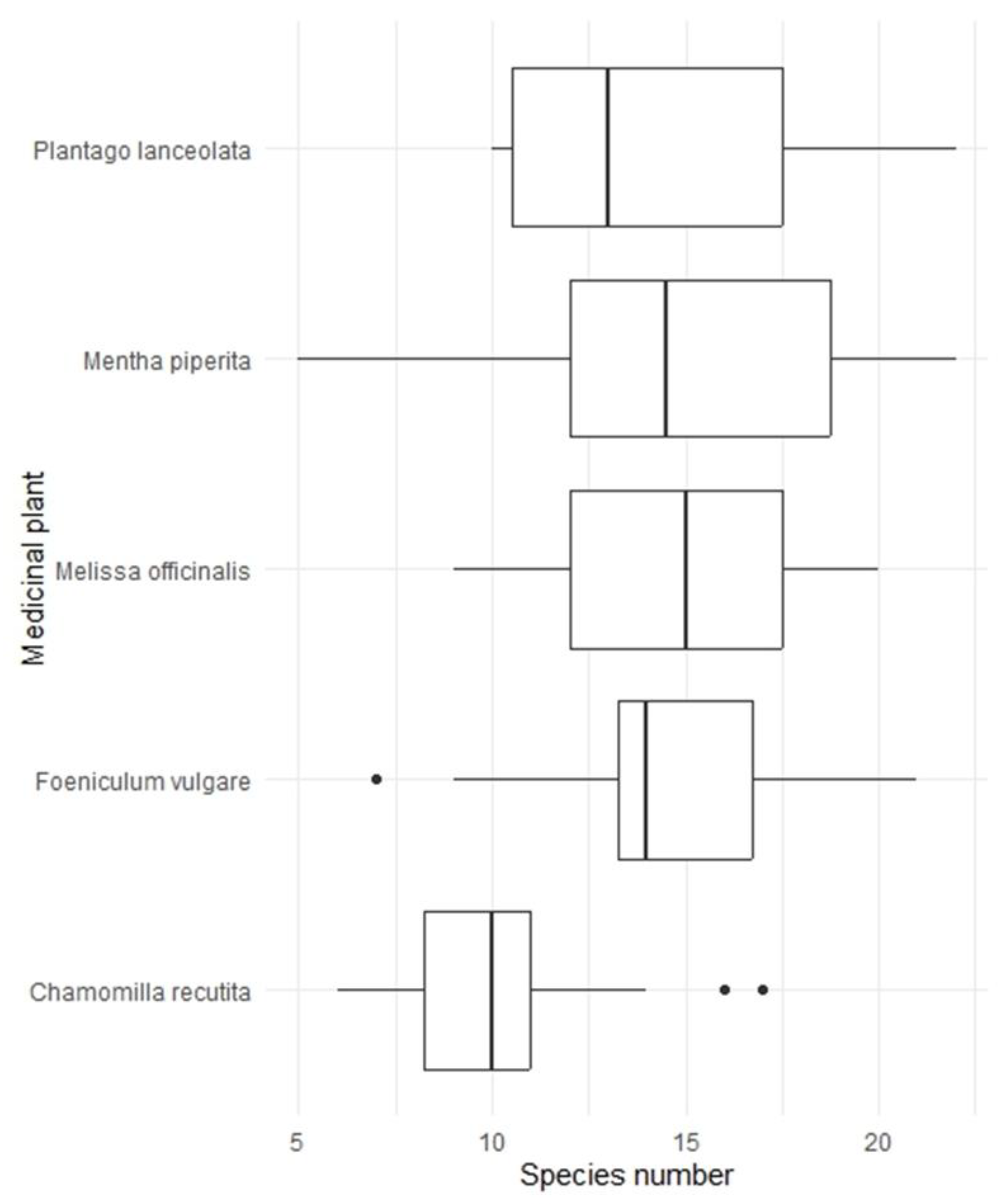

The total number of weed species recorded across studied medicinal crops was 109, while the mean number of weed species per specific medicinal crop ranged between 13 and 15, except in

Chamomilla recutita plots, where significantly fewer weed species were observed (

Figure 2).

3.2. Weed Vegetation Characteristics of Medicinal Crops

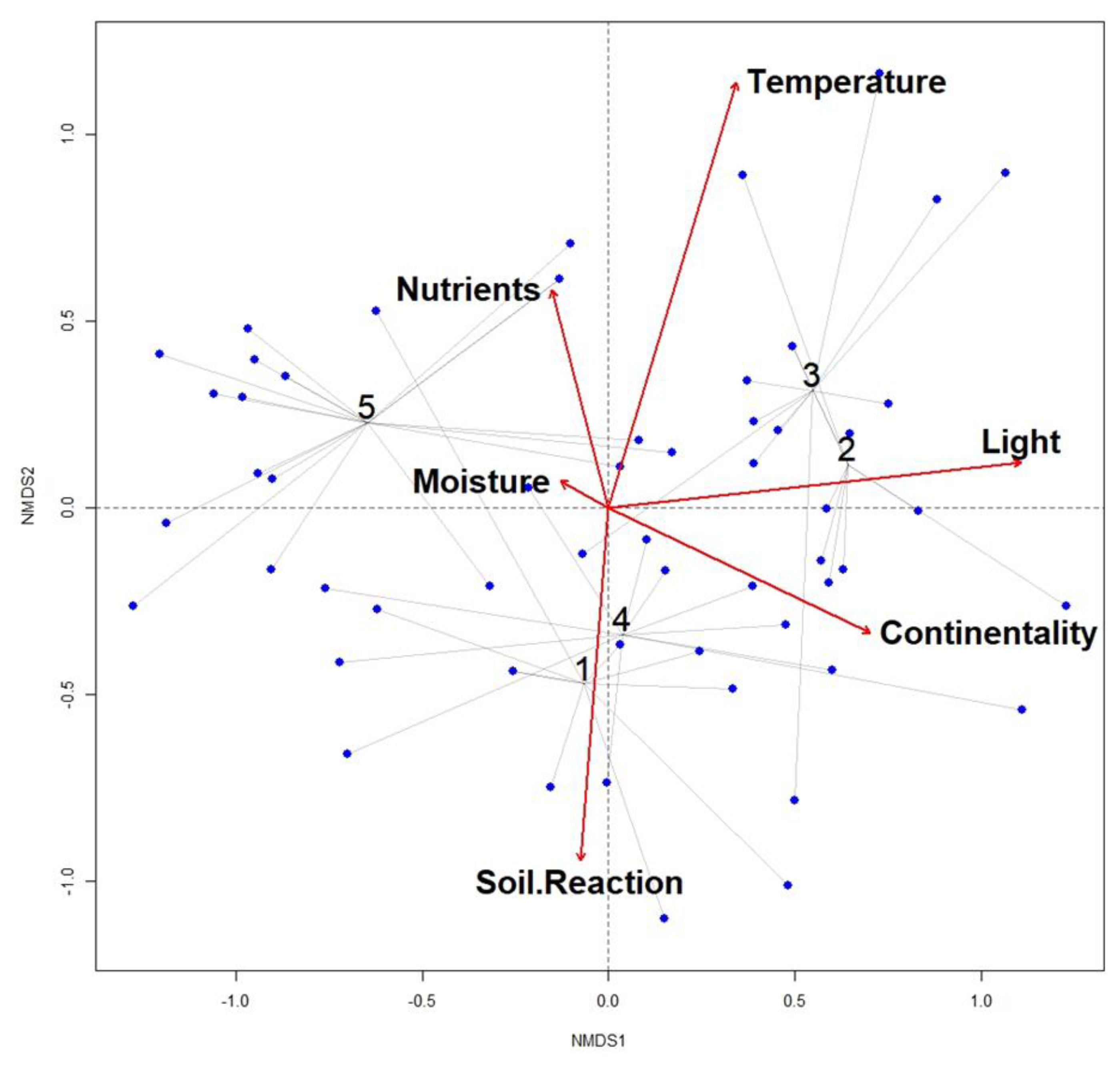

Cluster analysis of weed vegetation grouped plots into five groups and diagnostic, constant and dominant species with their fidelity values are showed (

Figure 3).

Group 1: Melissa officinalis (Lemon balm) plots

Number of plots: 10

Diagnostic species: Crepis biennis 18.5, Senecio vernalis 18.5, Trifolium repens 18.5

Constant species: Convolvulus arvensis 28, Lamium amplexicaule 21, Stellaria media 25

Group 2: Foeniculum vulgare (Fennel) plots

Number of plots: 10

Diagnostic species: Arctium lappa 16.2, Artemisia vulgaris 16.0, Conium maculatum 26.8, Cynara cardunculus 18.5

Constant species: Convolvulus arvensis 24

Group 3: Mentha piperita (Peppermint) plots

Number of plots: 10

Diagnostic species: Amaranthus blitoides 19.9, Amaranthus retroflexus (C, Dm) 35.2, Chenopodium polyspermum 18.5, Fumaria officinalis 18.7, Heliotropium europeum 21.4

Constant species: Amaranthus retroflexus (Dg, Dm) 24, Chenopodium album (Dm) 24, Lamium purpureum 25

Dominant species: Amaranthus retroflexus (Dg, C) 30, Chenopodium album (C) 30

Group 4: Plantago lanceolata (Ribwort plantain) plots

Number of plots: 11

Diagnostic species: Brassica nigra 17.1, Geranium molle 17.6, Medicago sativa 17.6

Constant species: Ambrosia artemisiifoila 24, Chamomilla recutita (Dm) 24, Cirsium arvense (Dm) 35, Lactuca serriola (Dm) 31, Lamium amplexicaule 21, Lamium purpureum 24, Lepidium draba (Dm) 22

Dominant species: Chamomilla recutita (C) 36, Cirsium arvense (C) 27, Lactuca serriola (C) 27, Lepidium draba (C) 27

Group 5: Chamomilla recutita (German Chamomile) plots

Number of plots: 18

Diagnostic species: Lithospermum arvense 20.6, Sinapis arvensis (C) 27.3

Constant species: Lamium amplexicaule 26, Lamium purpureum (Dm) 31, Sinapis arvensis (Dg) 21, Stellaria media (Dm) 53

Dominant species: Lamium purpureum (C) 33, Stellaria media (C) 67

3.3. Weed Vegetation-Environment Relationships

The Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination, based on species composition and ecological indicator values (

Figure 3), revealed that the most important ecological factors influencing the diversity and variability of weed vegetation in investigated medicinal crops were temperature and light in

Foeniculum vulgare and

Mentha piperita plots, soil reaction in

Melissa officinalis and

Plantago lanceolata plots, and nutrient content in

Chamomilla recutita plots. The first ordination axis was positively correlated with light (r=0.99392; P=0.001) and negatively with moisture (r=-0.87779; P=ns). The second NMDS axis was positively correlated with temperature (r=0.95785; P=0.001) and nutrients (r=0.96740; P=ns), and negatively with soil reaction (r=-0.99685; P=0.002).

4. Discussion

The diversity, abundance, and frequency of weed flora in the surveyed medicinal crops (lemon balm, fennel, peppermint, ribwort plantain, German chamomile) are influenced by agro-ecological conditions, crop species, and cultivation practices. These findings are consistent with previous studies [4, 9, 12, 13, 32, 33, 34]. The high weed diversity recorded (109 weed species across 29 families and 87 genera) in a relatively small area, such as the Pančevo farm, suggests that the environmental conditions are favorable for weed flora development. However, this also indicates challenges in weed management practices [10, 34].

Grouping of the surveyed plots by crop species revealed that specific diagnostic weed species developed in lemon balm and ribwort plantain plots. Annual weeds such as

Crepis biennis,

Senecio vernalis, and

Brassica nigra were predominant in lemon balm plots, while Geranium molle was characteristic of ribwort plantain plots. Weed vegetation in lemon balm and ribwort plantain was primarily influenced by soil reaction, whereas the weed composition in German chamomile plots was more strongly affected by nutrient availability. The relatively small overall influence of soil properties on weed composition may be due to the artificial adaptation of soil conditions through fertilization, mechanical weed control, and herbicide use [

35].

The absolute dominance of annual weed species (68.8% therophytes and 10% hemitherophytes) in studied medicinal crops, which are part of arable lands, further confirms that these areas are under continuous agricultural pressure [

15]. If these annual weed species, particularly those with high abundance, are not controlled promptly and effectively, they can severely reduce both the yield and quality of medicinal crops [9, 36]. Some annuals develop large canopies, such as:

Abutilon theophrasti,

Amaranthus retroflexus,

Ambrosia artemisiifolia,

Brassica nigra,

Chenopodium spp.,

Datura stramonium, and

Xanthium strumarium, making them strong competitors for aboveground resources. Additionally, many weeds germinate and establish earlier (winter and early spring species) such as

Avena fatua,

Bifora radians,

Brassica nigra,

Consolida spp.,

Capsella bursa-pastoris,

Galium aparine,

Lamium spp.,

Papaver rhoeas,

Stellaria media,

Veronica spp., and

Viola arvensis, giving them a competitive advantage for vital resources such as water, nutrients, and light.

Medicinal crops such as lemon balm, fennel, peppermint, ribwort plantain, and German chamomile, generally exhibit lower competitiveness against weeds, especially during their early growth stages, which contributes to high levels of weed infestation [

9]. This competition can prolong flowering and fruiting phases and significantly decrease final yields [

37]. Some weeds, like

Stellaria media (observed in medicinal crops with an abundance of 1–8 and a frequency of III–V), are particularly problematic due to their ephemeral life cycle and ability to produce multiple generations per year [

38]. Although classified as an annual,

S. media can also propagate vegetatively in the short term. It germinates throughout the year under favorable conditions and effectively competes with neighboring plants [

39].

Perennial weed species also pose substantial management challenges. Perennials such as Artemisia vulgaris, Rumex crispus, Taraxacum officinale, Elymus repens, Cirsium arvense, Convolvulus arvensis, Lepidium draba, Sonchus arvensis, and Sorghum halepense, were found with high frequency in the surveyed medicinal crops at Pančevo farm. The situation is more complex when their abundance is also significant, as seen with Elymus repens (abundance= 2–7), Cirsium arvense (ab.= 1–8), Rumex crispus (ab.= 2–8), Sorghum halepense (ab.= 1–8), Taraxacum officinale (ab.= 2–3), all of which were present in every surveyed field with medicinal crops. According to Miller [

40], the combined application of multiple weed control strategies is typically more effective for managing perennial weeds.

Since medicinal crops generally allow only limited herbicide use [36, 41], repeated mechanical or other non-chemical measures are essential to deplete perennial weed populations [

8] and reduce both the seed bank and vegetative reproductive structures in the soil. Rhizomatous grasses, particularly

Elymus repens and

Sorghum halepense, present persistent control challenges [

42]. Furthermore, species like

Cirsium arvense (which forms clean oases) and

Convolvulus arvensis and

Calystegia sepium (which twine around crop plants), with their substantial aboveground biomass, are aggressive competitors and can significantly reduce yields if not controlled in a timely manner [43, 44].

For sustainable and effective management of perennial weeds in medicinal crops, an integrated weed management approach is recommended, combining cultural and chemical methods with a focus on prevention and early intervention. Agronomic practices such as tillage, mowing, and grazing can help suppress rhizome spread and seed production. When herbicides are used, targeting weeds at their early, most susceptible stages are crucial for effective control.

To further mitigate weed issues, it is important to ensure that the plots are thoroughly cleaned after harvest, removing any residual crop plants such as in our cases, Foeniculum vulgare, Cynara cardunculus, and Linum usitatissimum, as these can emerge as volunteer crops in subsequent seasons and are often difficult to control chemically. Special attention should also be given to toxic weed species, such as Bifora radians, Conium maculatum, Datura stramonium, and Solanum spp., which contain various harmful alkaloids (atropine, coniine, conhydrine, gamma-coniceine, hyoscine, hyoscyamine, N-methylconiine, pseudotropine, pseudoconhydrine, scopolamine, solasonine, solamargine, etc.). These compounds can significantly compromise the quality and safety of medicinal crops [45-47].

Ultimately, knowledge of weed diversity, abundance, and frequency in medicinal crops provides a reliable framework for accurately assessing weed infestation and serves as a foundation for strategic weed management planning. Weed control measures should be tailored to the most frequent, abundant, and dominant species specific to each cropland or locality. So far, no comprehensive documentation exists regarding the relative importance and quantitative weed infestation levels in medicinal crop fields in Serbia. This study represents a valuable starting point for developing targeted weed management strategies for medicinal crop plantations in the region.

5. Conclusions

The diversity, abundance and frequency of weed species in medicinal crops are influenced by multiple factors, including crop type and genotype, agro-ecological conditions, and applied weed management strategies. This study confirmed the presence of 109 weed species across five different medicinal crops, comprising 75 annuals and 34 perennials, with a predominance of broadleaved weeds. The recorded weed flora spanned 29 families and 88 genera. The most frequent and abundant species included annual weeds such as Amaranthus retroflexus, Chenopodium album, Galium aparine, Lactuca serriola, Lamium amplexicaule, Lamium purpureum, Papaver rhoeas, Stellaria media, Veronica hederifolia, Veronica persica, as well as perennial weeds like Elymus repens, Artemisia vulgaris, Cirsium arvense, Convolvulus arvensis, Lepidium draba, Rumex crispus, Sonchus arvensis, Sorghum halepense, and Taraxacum officinale.

These findings provide a solid foundation for accurately assessing weed infestation levels in medicinal crop fields and highlight the need for species-specific and locally adapted weed management strategies. Considering the limited herbicide options available in medicinal crop production, integrating cultural, mechanical, and targeted chemical control measures is essential for sustainable weed management. The results of this study contribute to filling the existing knowledge gap regarding weed flora in medicinal crop plantations in Serbia and can serve as a valuable reference for the development of effective weed control programs tailored to this specific cropping system.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.V., D.B. and A.D.; methodology, S.V. and D.B.; software, S.A. and U.Š.; validation, S.V., D.B. and T.M.; formal analysis, S.V. and T.T.; investigation, D.B. and A.D.; resources, T.M., A.D. and M.R.; data curation, S.A. U.Š. and S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B. and S.V..; writing—review and editing, T.M. and S.V.; visualization, A.D., M.R. and T.T.; supervision, S.V.; project administration, A.D. and T.M.; funding acquisition, S.V., D.B., T.M. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, grant numbers 451-03-136/2025-03/200003 and 451-03-137/2025-03/200116 and the APC was funded by Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, grant number 451-03-137/2025-03/200116.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KAN |

calcium ammonium nitrate |

| T |

therophytes |

| TH |

thero-hemicryptophytes |

| G |

geophytes |

| H |

hemicryptophytes |

| Ch |

chamaephytes |

| P |

phanerophytes |

| Dg |

diagnostic species |

| Dm |

dominant species |

| C |

constant species |

| NMDS |

non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| EIVs |

ecological indicator values |

References

- www.stat.gov. (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- World Bank. Exploring the Potential of Agriculture in the Western Balkans, Washington, DC, 2018.

- FAO. Small Family Farms Country Factsheet: Serbia. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb3863en/cb3863en.pdf.

- Bayisa, N.G.; Hundesa, N. Assessment and identification of weed flora associated to medicinal and aromatic plants at Wondo Genet District, Ethiopia. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2017, 6(3), 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomado, T.; Milberg, P. Weed flora in arable fields of eastern Ethiopia with emphasis on the occurrence of Parthennium hysterophorus L. Weed Res. Weed Res. 2000, 40, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashem, M.A.; Faroque, M.A.; Bilkis, S.E. Weed management in Bangladesh: Policy issues to better way out. J. Sci. Found. 2009, 7, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak, A.; Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Niewiadomska, A.; Pilarska, A.A. The Problem of Weed Infestation of Agricultural Plantations vs. the Assumptions of the European Biodiversity Strategy. the Assumptions of the European Biodiversity Strategy. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matković, A.; Božić, D.; Filipović, V.; Radanović, D.; Vrbničanin, S.; Marković, T. Mulching as a physical weed control method applicable in medicinal plants cultivations. Lekovite sirovine 2015, XXXV (35), 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendawy, S.F.; Abouziena, H.F.; Abd El-Razik, T.M.; Amer, H.M.; Hussein, M.S. Winter weeds and its control in the medicinal plants in Egypt: a survey study. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2019, 18(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, F.; Mennan, H. Weed problem in medicinal plants. In New development on medicinal and aromatic plants. In New development on medicinal and aromatic plants, Özyazici G., Ed.; Iksad Publishing hous: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; Chapter 3; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pinke, G.; Blazsek, K.; Magyar, L.; Nagy, K.; Karácsony, P.; Czúcz, B.; Botta-Dukát, Z. Weed species composition of conventional soybean crops in Hungary is determined by environmental, cultural, weed management and site variables. Weed Res. 2016, 56(6), 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.S. Weed Floral Diversity of Medicinal Value in Terraces of Horticulture Crop Fields in Bharsar, Uttarakhand, India. IJPGR 2017, 30(2), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljevnaić-Mašić, B.; Brdar-Jokanović, M.; Džigurski, D.; Nikolić, Lj.; Meseldžija, M. Weed Composition in conventionally and organically grown medical and aromatic plants. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2022, 21, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C. A study on crop weed competition in field crops. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2018, 7(4), 3235–3240. [Google Scholar]

- Vrbničanin, S.; Božić, D. Korovi. [Weeds]. Univerzitet u Beogradu, Poljoprivrdni fakultet: Beograd; Serbia, 2021; pp. 1-432. [in Serbian].

- Wiersema, J.H.; León, B. World Economic Plants: A Standard Reference. CRC Press: New York, USA, 1999, pp. 792. [CrossRef]

- Vrbničanin, S.; Kojić, M. Biološka i ekološka proučavanja korova na području Srbije: razvoj, sadašnje stanje i perspektive. [Biological and ecological research of weeds in Serbia: development, current status, perspectives]. Acta herbologica 2000, 9 (1), 41-59. [in Serbian].

- Isah, T. Stress and defense responses in plant secondary metabolites production. Biol. Res. 2019, 52(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puschner, B.; Peters, A.; Woods, L. Toxic weeds and their impact on animals. In Proceedings of the 36th Western Alfalfa & Forage Symposium, Reno, USA, 11-13 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carrubba, A. Weed and weeding effects on medicinal herbs. In Medicinal Plants and Environmental Challenges; Ghorbanpour, M., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 295–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropff, M.J.; Spitters, C.J.T. A simple model of crop loss by weed competition from early observations on relative leaf area of the weeds. Weed Res. 1991, 31(2), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet,J. Pfanzensoziologie. Grundzuger der Vegetationskunde, 3 Aufl; Springer: Wien, Austria, 1964; [in German]. [Google Scholar]

- Westhoff, V.; van der Maarel, E. The Braun-Blanquet Approach. In Ordination and classification of communities, Whittaker, R.H., Ed.; Dr. W. Junk: The Hague, Netherland, 1973; pp. 616–726. [Google Scholar]

- Euro+Med PlantBase, Euro+Med PlantBase – the information resource for Euro-Mediterranean plant diversity, 2025. Available online: https://www.europlusmed.org (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Raunkier, C. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography; Calderon Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Tichý, L. JUICE, software for vegetation classification. J. Veg. Sci. 2002, 13, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytrý, M.; Tichý, L.; Holt, J.; Botta-Dukat, Z. Determination of diagnostic species with statistical fidelity measures. J Veg Sci. 2002, 13, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Guillaume, B.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Henry, M.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; Wagner, H.; Barbour, M.; Bedward, M.; Bolker, B.; Borcard, D.; Carvalho, G.; Chirico, M.; De Caceres, M.; Durand, S.; Evangelista, H.; FitzJohn, R.; Friendly, M.; Furneaux, B.; Hannigan, G. O.; Hill, M.; Lahti, L.; McGlinn, D.; Ouellette, M.-H.; Cunha, E.; Smith, T.; Stier, A.; Ter Braak, C.; Weedon, J. Cran.rproject. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.htm.

- Hellinger, E. Neue Begründung der Theorie quadratischer Formen von unendlichvielen Veränderlichen. J. fur Reine Angew. Math., 1909, 136, 210–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, S. Valori di bioindicazione delle piante vascolari della flora d`Italia. Br.-Bl. 2005, 39, 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Travlos, I.S.; Cheimona, N.; Roussis, I.; Bilalis, D.J. Weed-species abundance and diversity indices in relation to tillage systems and fertilization. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, D.; Paul, P.; Mondal, S.; Pal, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Chowdhury, M. Survey and documentation of the Weed Flora in NBU Garden of Medicinal Plants. NBU J. Plant Sci. 2020, 12, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobir, M.S.; Paul, S.; Hajong, P.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Rahman, M.H. Taxonomic diversity of weed flora in pulse crops growing field at south-western part of Bangladesh. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2021, 6(4), 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimalová, Š.; Lososová, Z. Arable weed vegetation of the northeastern part of the Czech Republic: effects of environmental factors on species composition. Plant Ecol. 2009, 203, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Baksh, H.; Patra, D.D.; Tewari, S.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Katiyar, R.S. Integrated weed management of medicinal plants in India. International Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 2011, 1(2), 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Carrubba, A.; Militello, M. Nonchemical weeding of medicinal and aromatic plants. ASD 2013, 33, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.A.; Feast, P.M. Seasonal distribution of emergence in some annual weeds. Exp. Hortic. 1970, 21, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pacanoski, Z. Stellaria media (L.) Vill. (common chickweed) – a strong or weak competitor in the autumn and early-spring sown crops? Acta herbologica 2024, 33(2), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.W. Integrated Strategies for Management of Perennial Weeds. Invas. Plant Sci. and Mana. 2017, 9(2), 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darre, A.; Novo, R.; Zumelzu, G.; Bracamonte, R. Chemical control of annual weeds in Mentha piperita. Agriscientia 2004, 21, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Squires, C.C.; Walsh, M.J. Sorghum halepense. In Biology and Management of Problematic Crop Weed Species, Chauhan, B.S., Ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2021; pp. 391–405, Chapter 18. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.; Mangold, J.; Menalled, F.; Orloff, N.; Miller, Z.; Lehnhoff, E. A Meta-Analysis of Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense) Management. Weed Sci. 2018, 66(4), 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abbasi, S.H.A.; Mustafa, H.A.; Al-Naqib, A.T.H.; Adnan, A.; Al-Majmaei, M.; Hameed, A.M.; Alazzawi, H.A.H.; Muhammed aldouri, G.A.; Awad, A.A.; Majeed, Q.A.; Dyaa yasin, A. Weed of Convolvulus arvensis damage and control methods. Chemical and Environmental Science Archives 2021, 1(1), 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Berkov, S.; Zayed, R.; Doncheva, T. Alkaloid patterns in some varieties of Datura stramonium. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, H.; Rychlik, M.; Thiermann, H.; Schmidt, C. Simultaneous quantification of atropine and scopolamine in infusions of herbal tea and Solanaceae plant material by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight (Tandem) Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2018, 32, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nijs, M.; Crews, C.; Dorgelo, F.; MacDonald, S.; Mulder, P.P.J. Emerging Issues on Tropane Alkaloid Contamination of Food in Europe. Toxins 2023, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).