Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

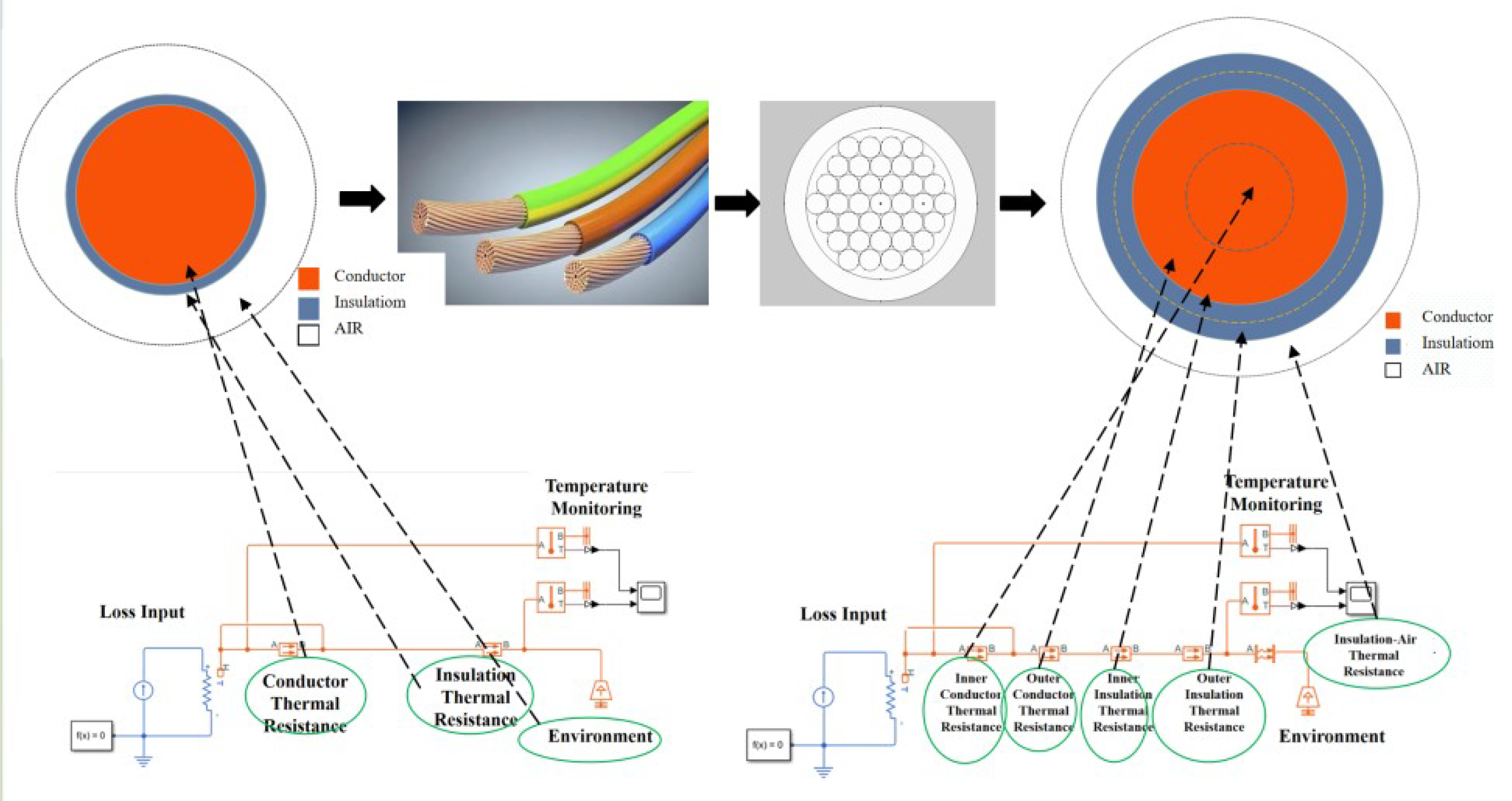

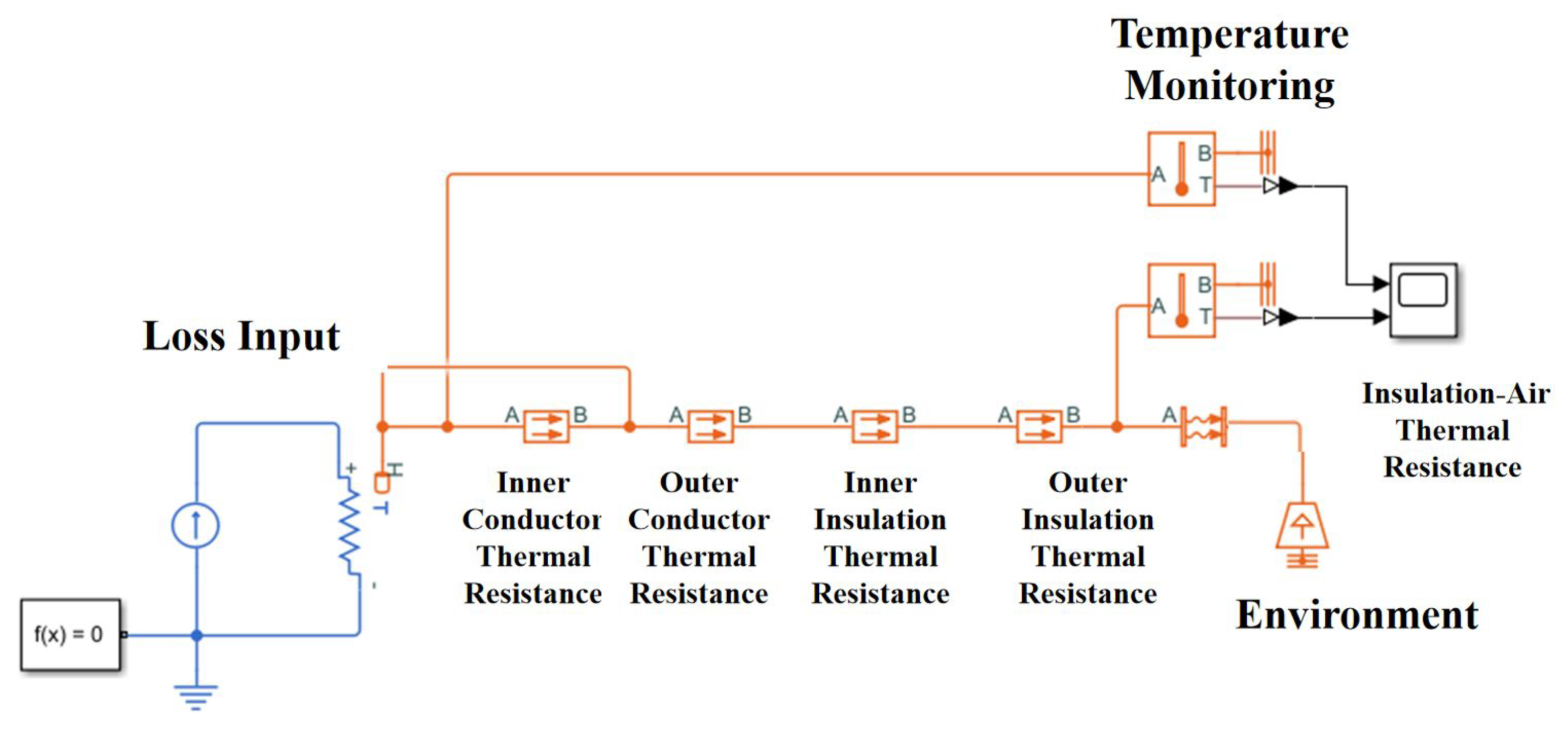

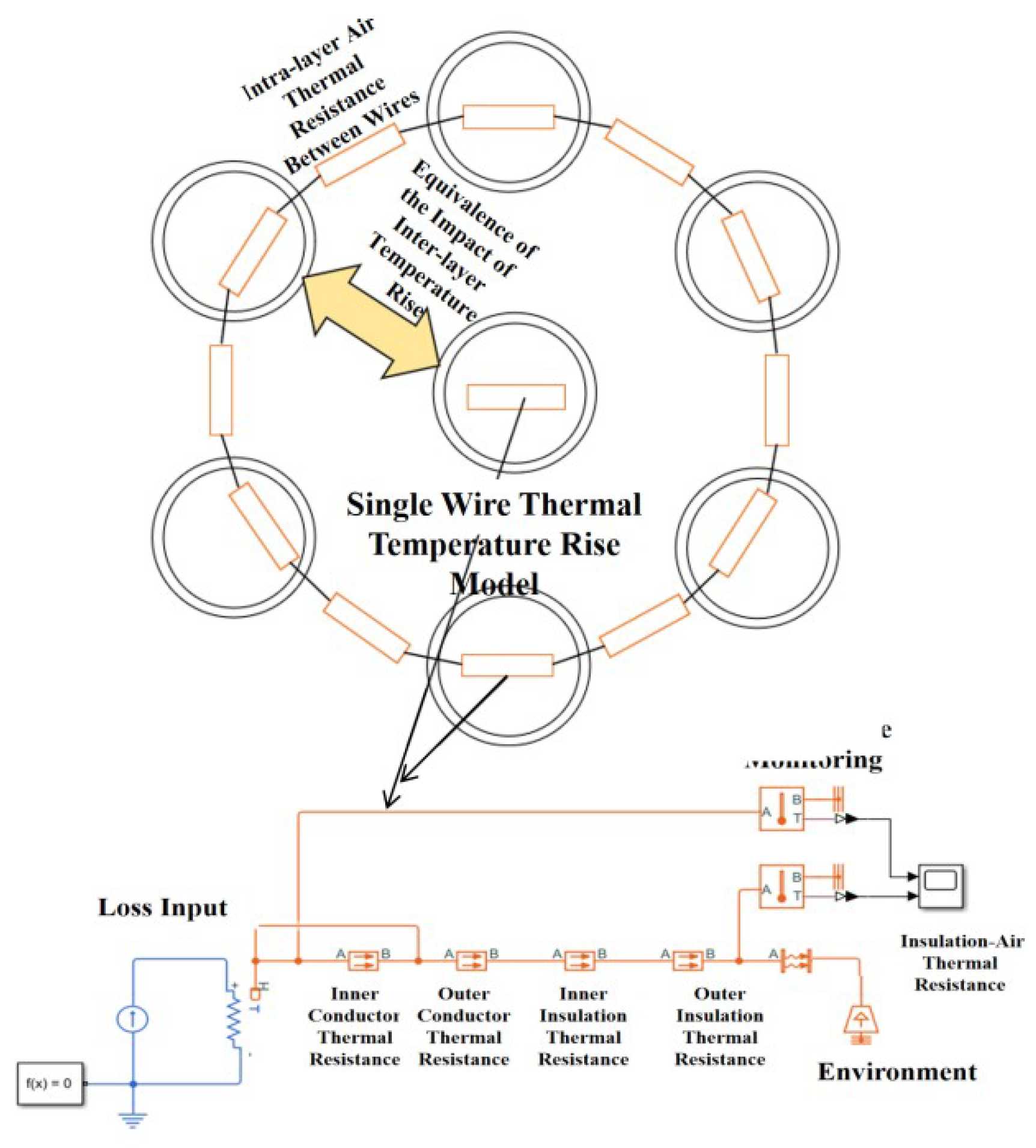

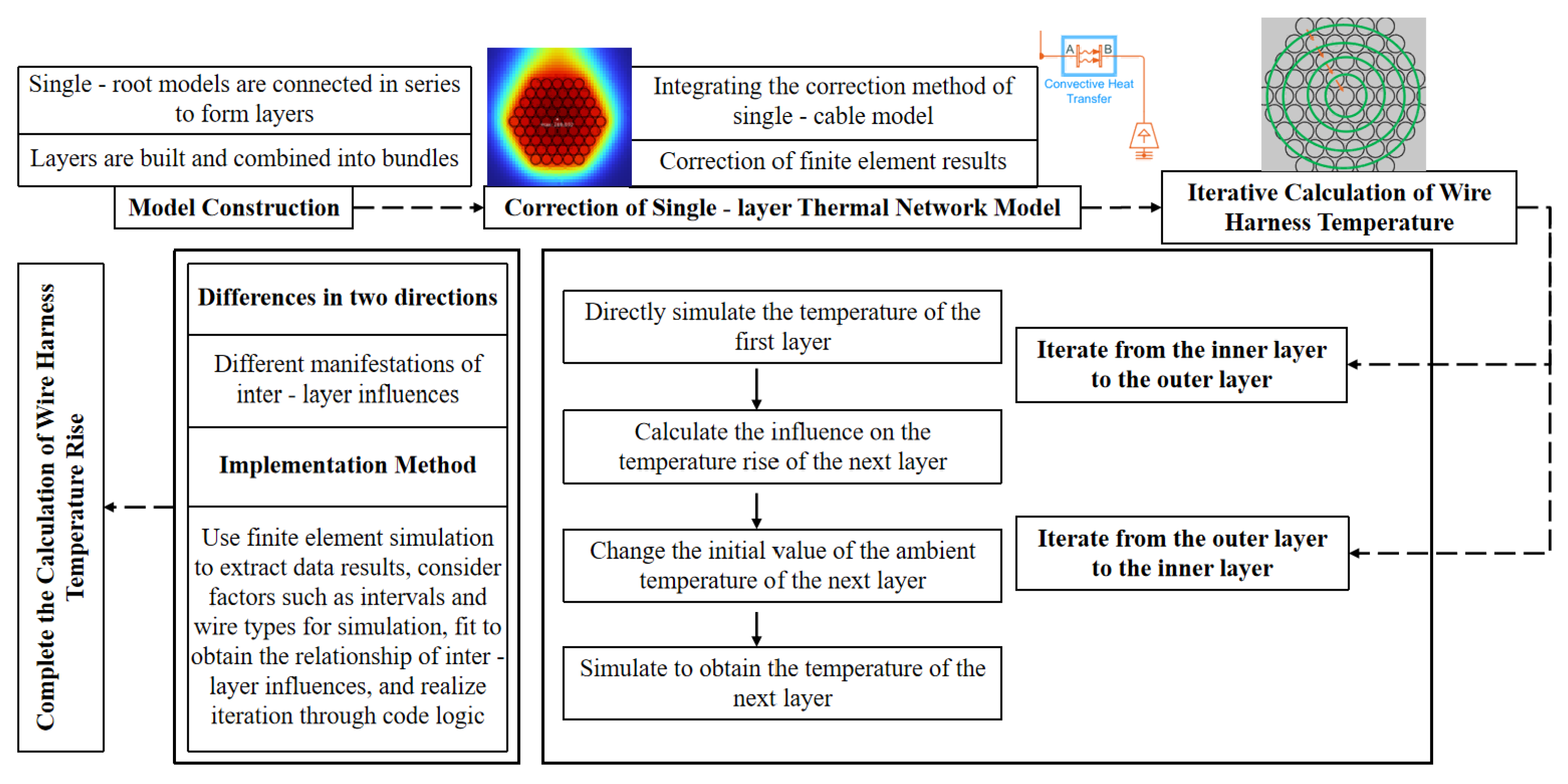

- Establishment of a high-precision thermal resistance hierarchical wire thermal network: The wire core conductor and insulation layer are divided into inner and outer layers. The model accuracy is corrected through the thermal resistance of the inner and outer layers. Meanwhile, a thermal resistance is added between the outer layer of the insulation and the external ambient air to simulate the heat dissipation loss due to changes in the material properties of the insulation and air, thereby correcting the model accuracy.

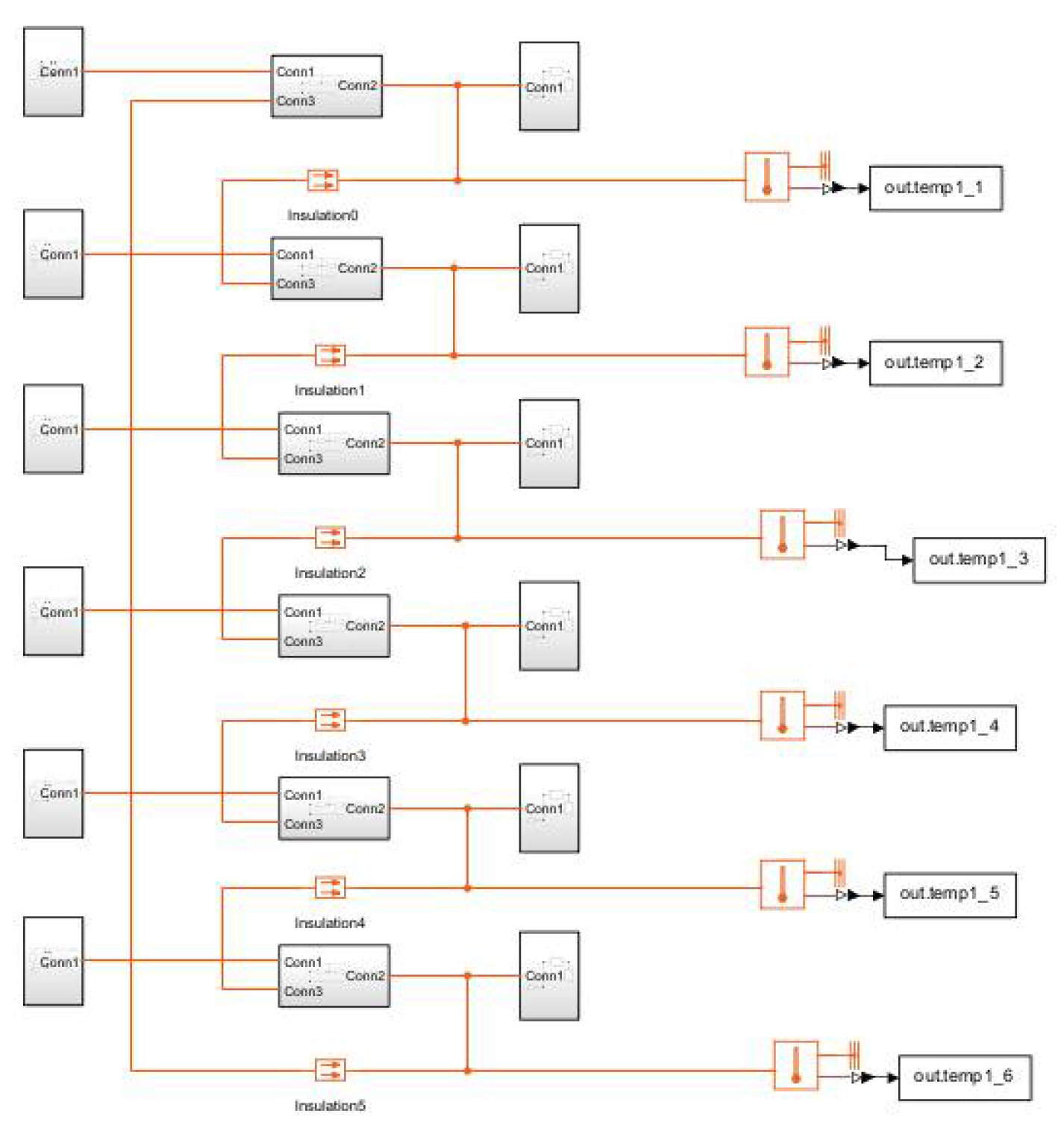

- Construction of a hierarchical harness thermal network model based on finite element model correction: Through the topology of the thermal resistance hierarchical wire thermal network, a structure of "series within layers and parallel between layers" is constructed. By conducting power-on simulations on the finite element single-layer model, the convective heat transfer coefficients of each layer’s thermal network model are corrected to complete the construction of the hierarchical harness thermal network model.

- Hierarchical thermal network iterative calculation method: Based on the hierarchical harness thermal network model, the interlayer influence is equivalently constructed through the finite element model results, and the rapid calculation of the hierarchical thermal network model is completed through the interlayer model iterative algorithm.

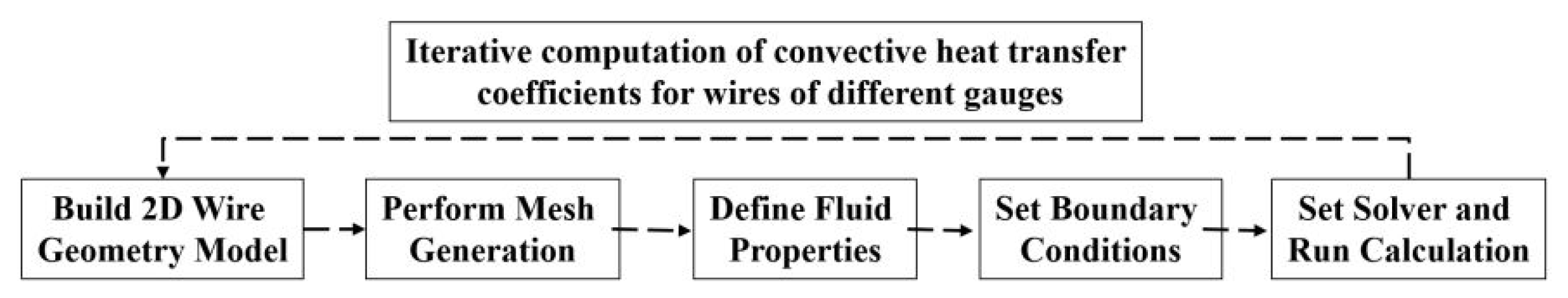

2. Construction of High-Fidelity Finite Element Model and Solution of Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient

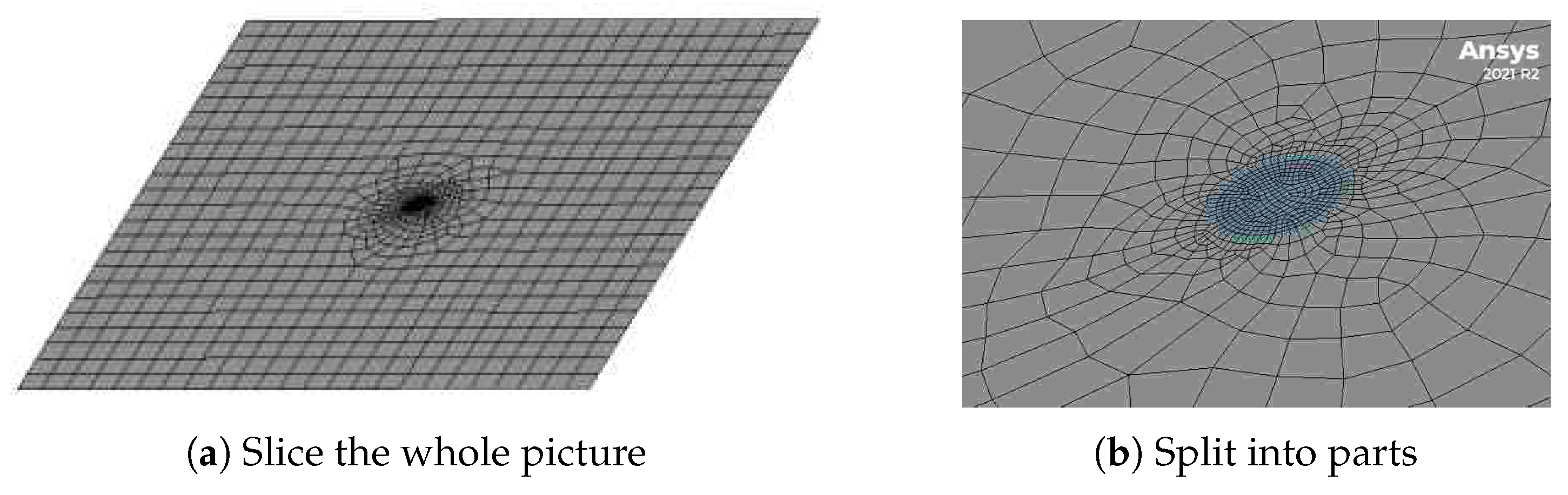

- Modeling and grid generation: Create the fluid domain and solid surface, and then use the meshing tool to discretize the geometric model to generate a computational grid suitable for calculating fluid flow and heat transfer. The meshing quality is crucial to the calculation results, directly affecting the calculation accuracy of wire temperature rise. Especially in the boundary layer area, sufficiently fine grids are required to capture the temperature gradient and velocity gradient of the fluid. The finite element grid is shown in Figure 2.

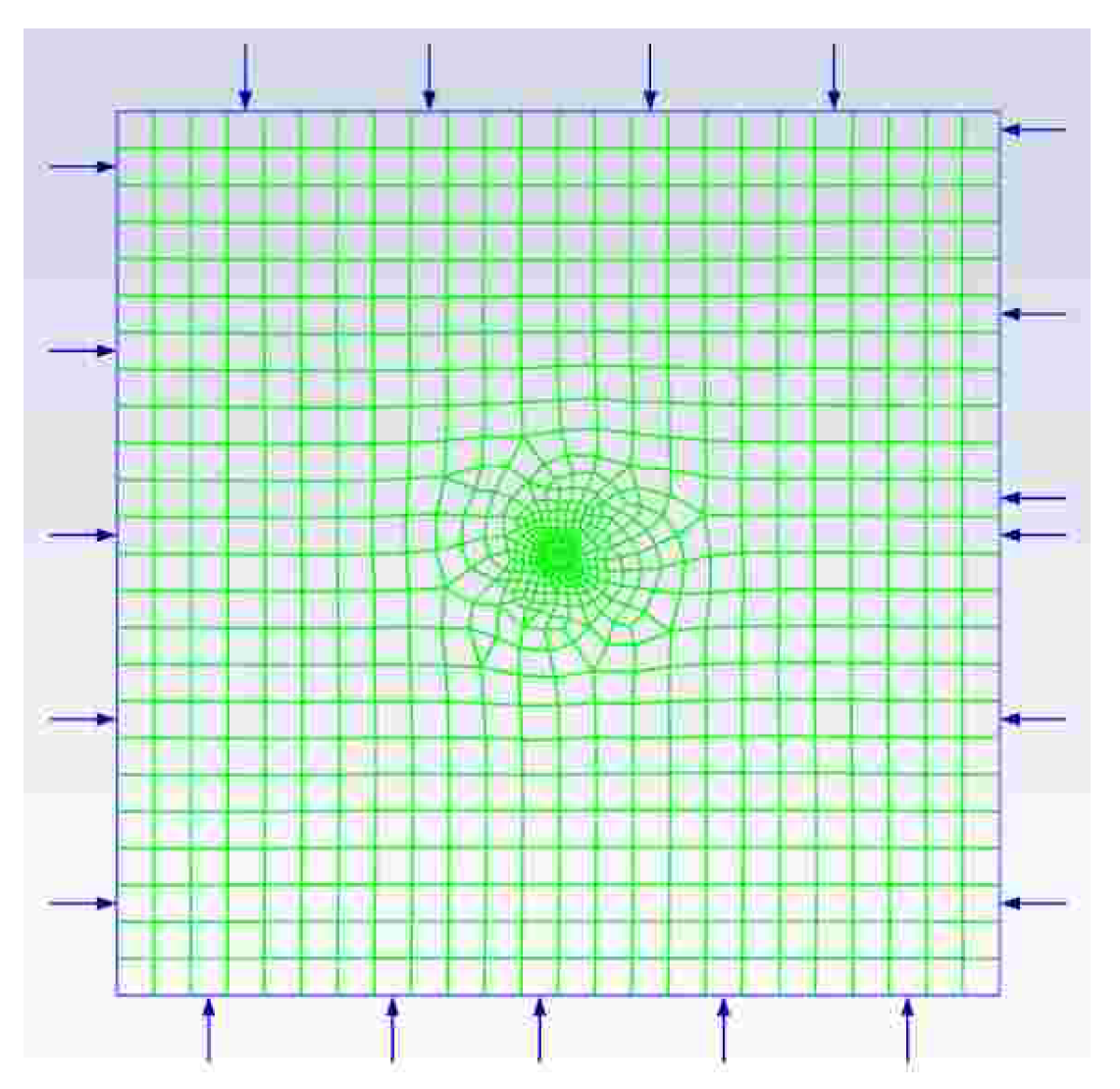

- Setting the boundary conditions of the model: Select a suitable laminar flow model or turbulent flow model according to the specific application scenario, and set the inlet boundary conditions and outlet boundary conditions, such as setting them as fixed pressure, flow rate, and ambient temperature. The grid diagram after setting the model boundary conditions is shown in Figure 3.

-

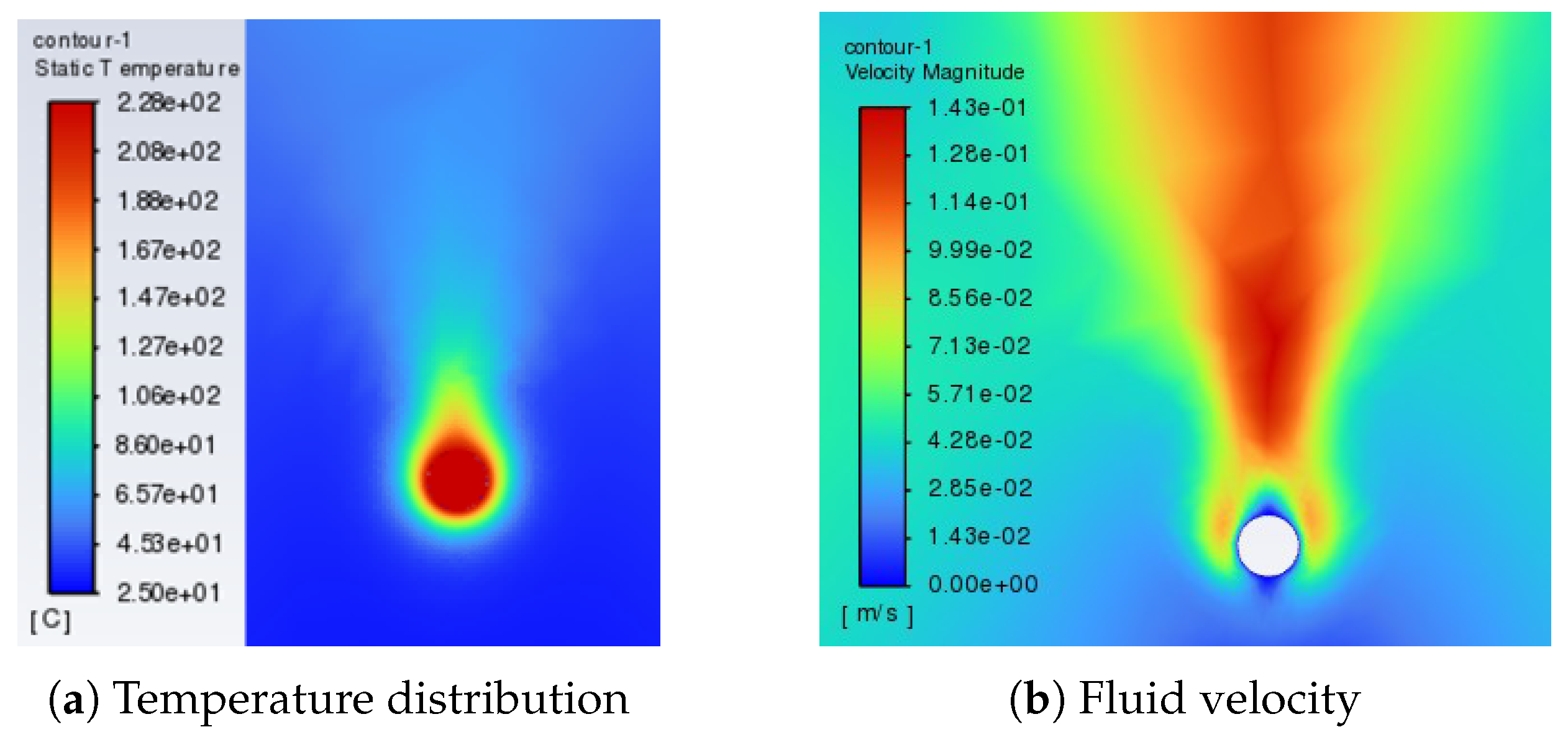

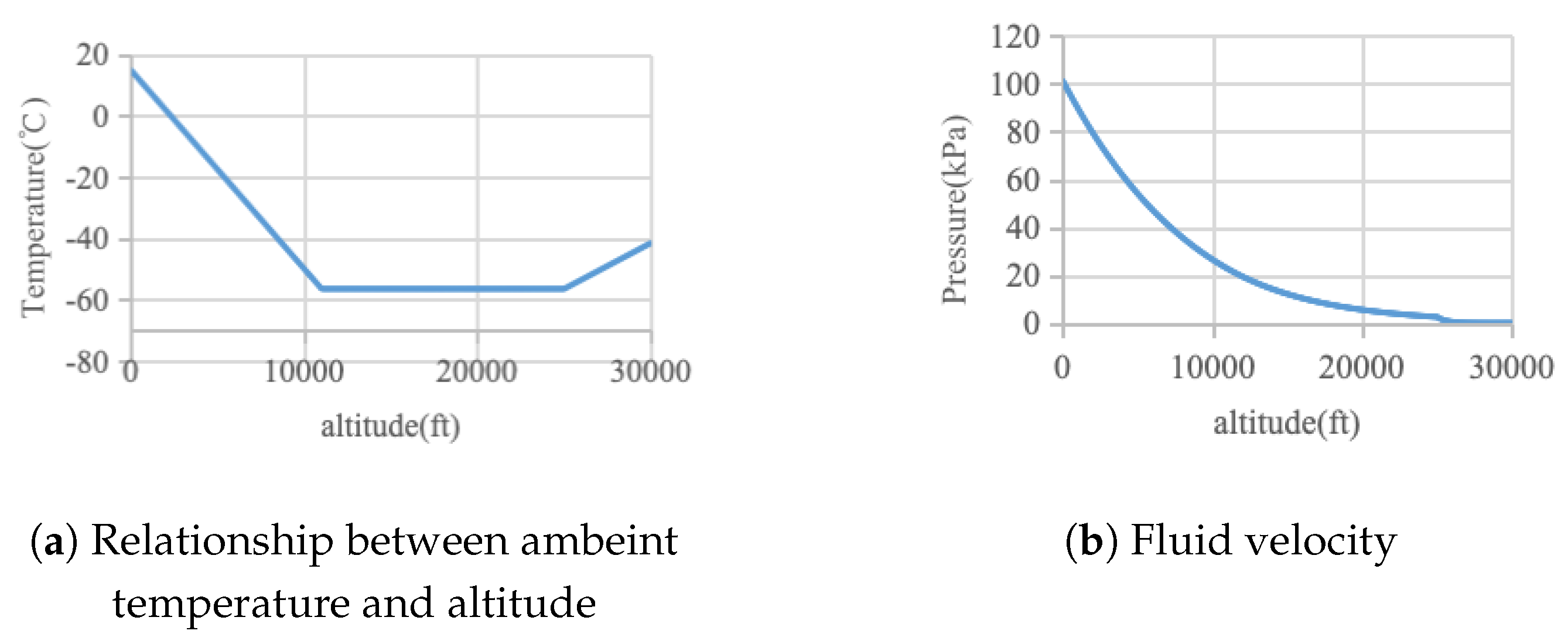

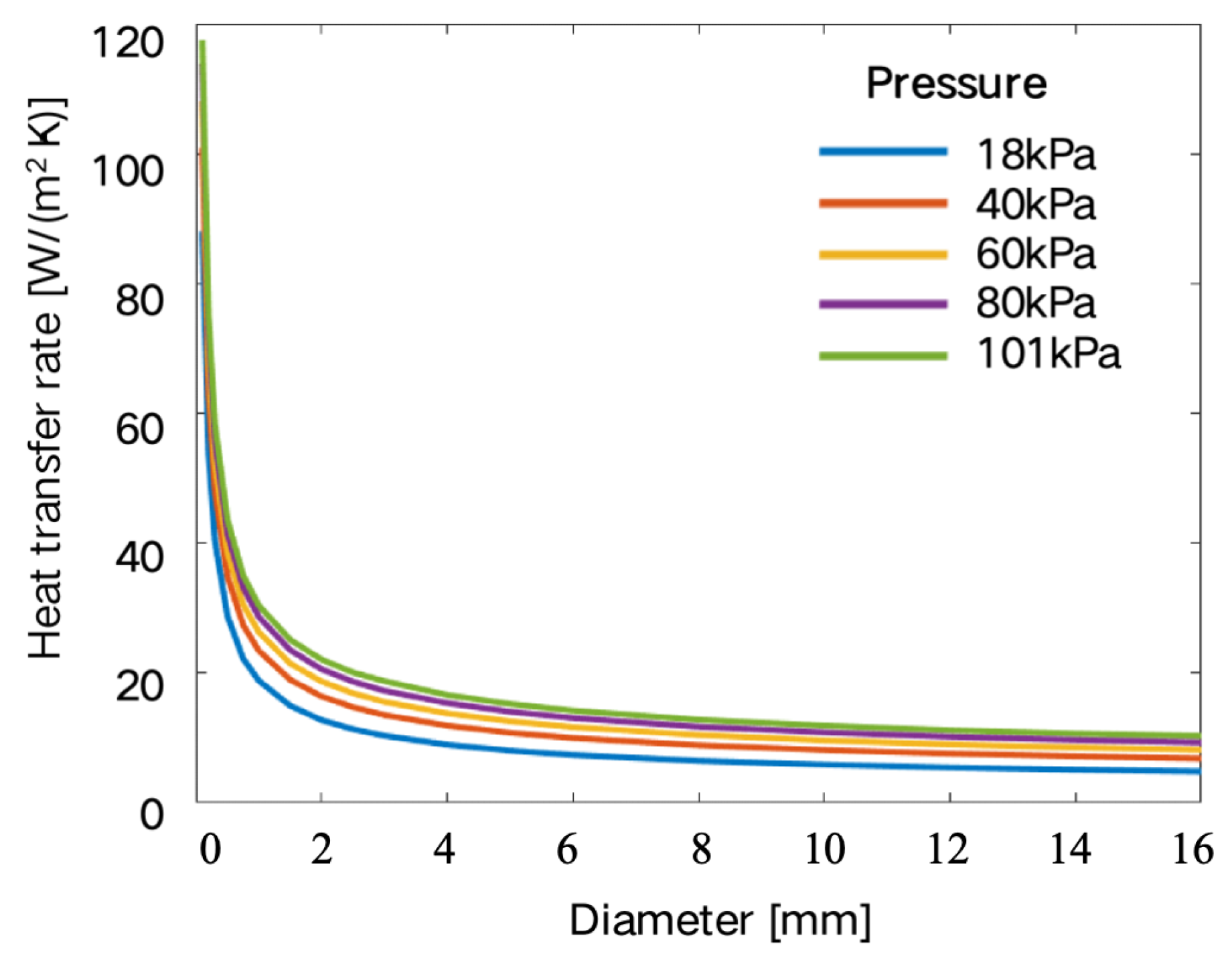

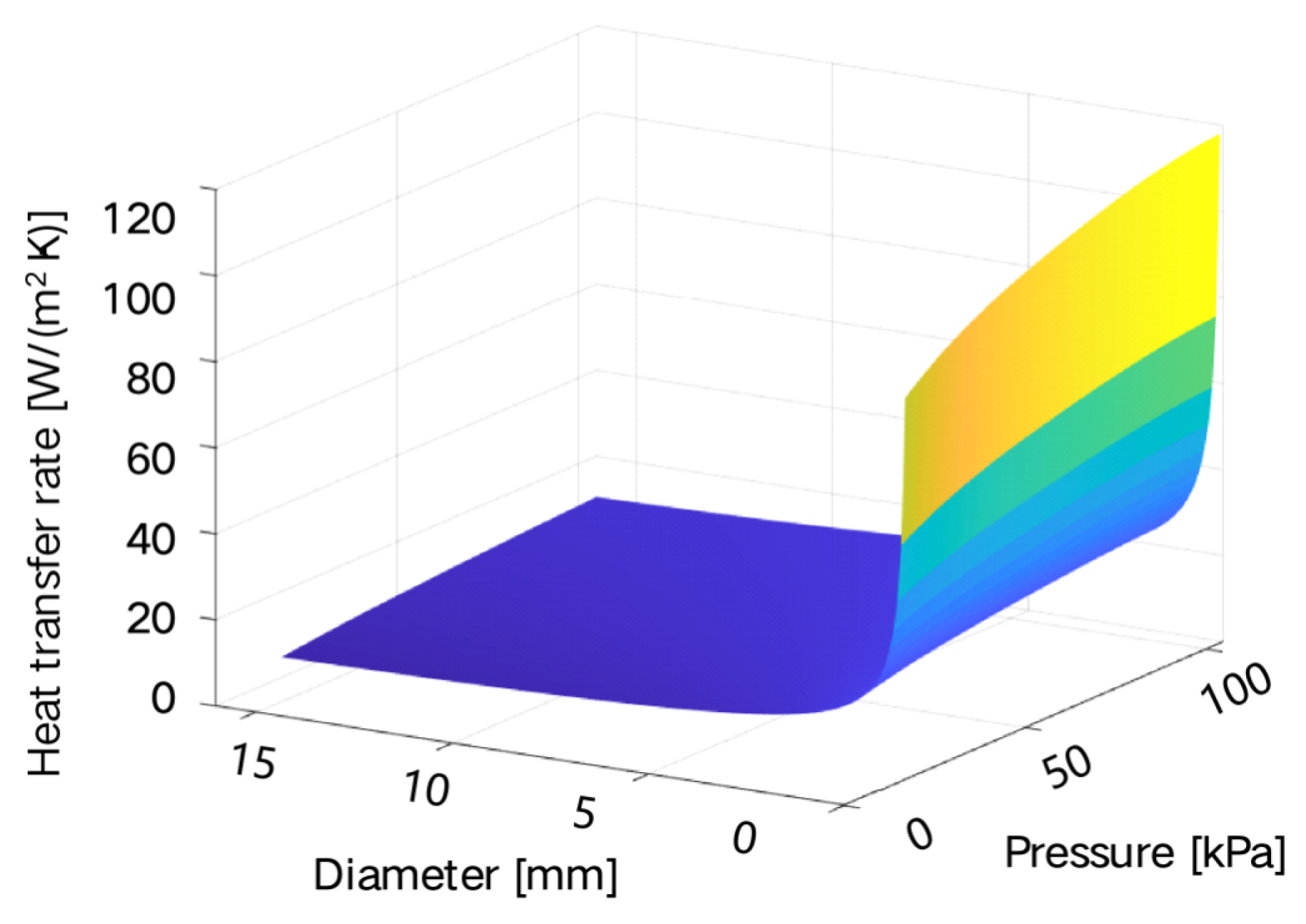

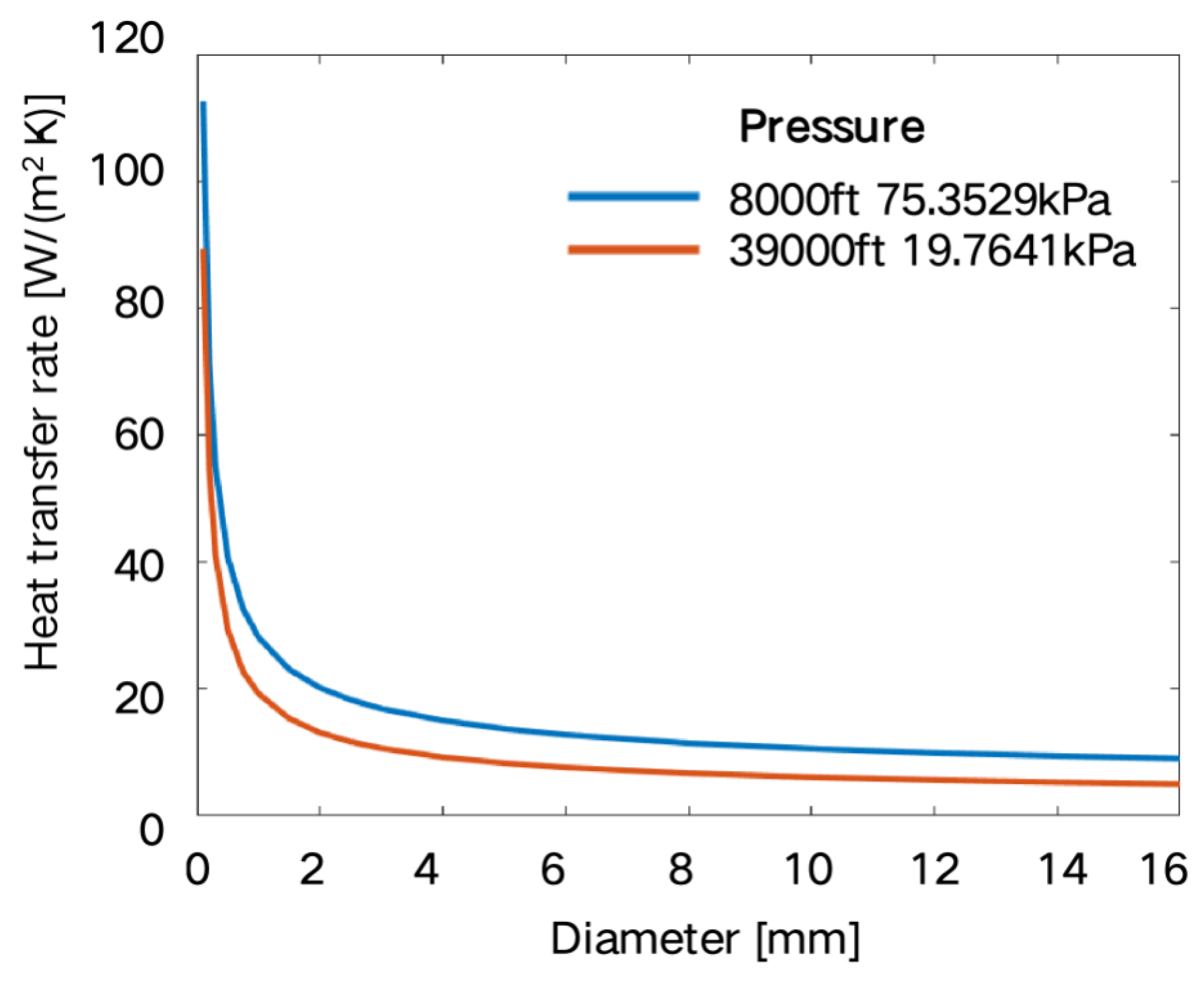

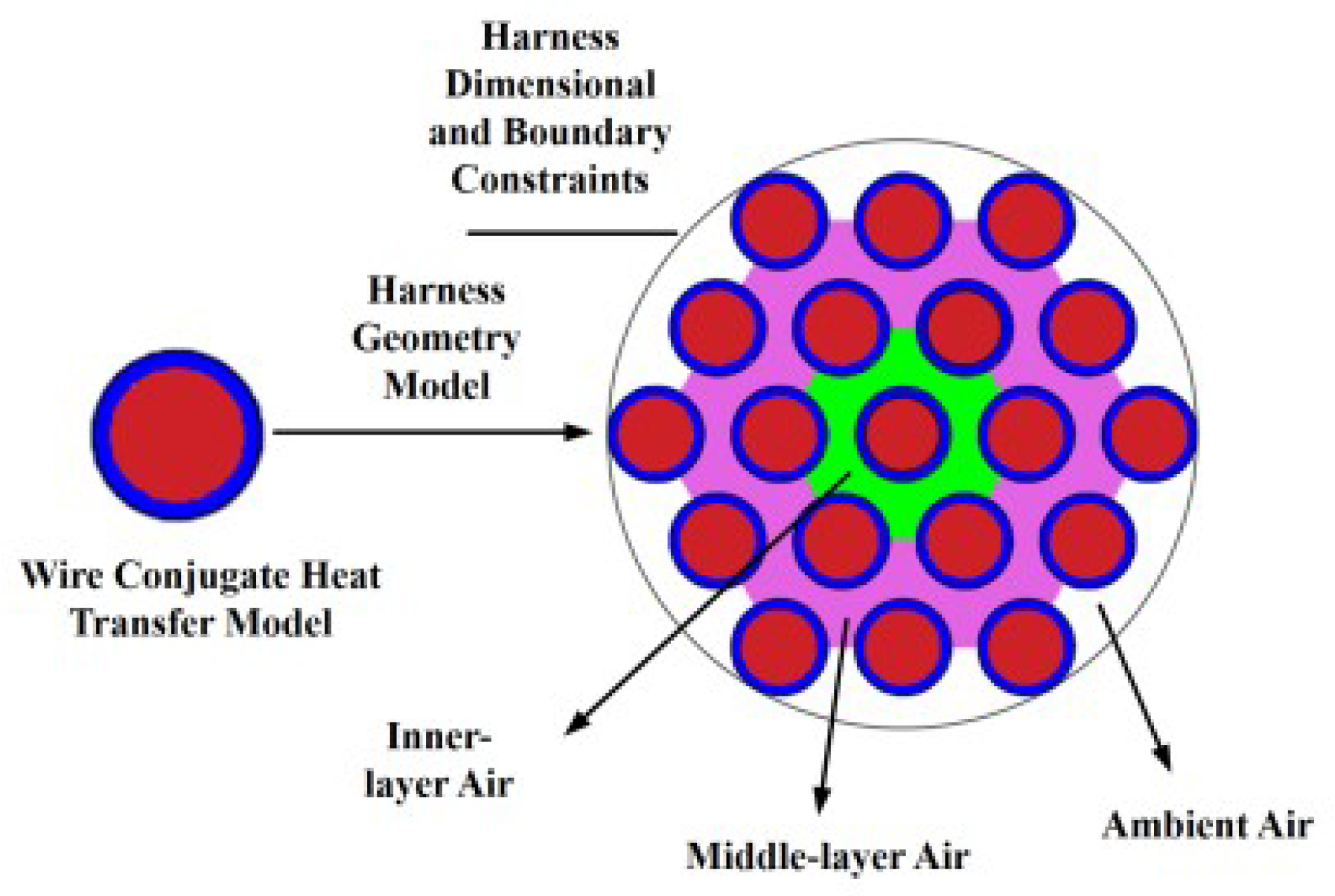

Setting the solver and calculating: Select an appropriate solver and numerical method, and set appropriate convergence criteria for iterative control. The convergence of the calculation process is judged by monitoring the changes in physical quantities (such as flow rate, temperature, residual, etc.). After the calculation is completed, check the temperature distribution, velocity field, and heat flux density of the flow field to ensure that the results meet the physical expectations.The air thermal conductivity under normal pressure is fixed, and the convective heat transfer coefficient should decrease with the increase of the wire diameter. The fluid model is used for simulation, then fitted, and then substituted into the wire thermal balance formula to reduce the calculation amount while ensuring the calculation accuracy. In the finite element model, only convective heat dissipation is set, and no radiation heat dissipation is set. The four surrounding boundaries are set as open boundaries, that is, allowing gas to flow in or out freely to simulate an infinite space. The simulation results of AWG10 wire under 101 A current at normal temperature and pressure are shown in Figure 4, where (a) is the temperature distribution and (b) is the flow velocity distribution.In order to obtain the convective heat transfer coefficients of different wires at different temperatures and altitudes, the relationship between temperature, pressure, and altitude is first established, as shown in Figure 5. To obtain the relationship between pressure and convective heat transfer coefficient, it is necessary to first use fluid finite element software to simulate the convective heat transfer coefficient under different pressures. The ambient pressures of 18 kPa, 40 kPa, 60 kPa, 80 kPa, and 101.4 kPa are selected to solve the convective heat transfer coefficients of single wires with different wire gauges, and the results are shown in Figure 6. At normal pressure of 101 kPa, the air convection heat dissipation effect is good, and the corresponding convective heat transfer coefficient is the largest. As the air pressure decreases, the convective heat transfer coefficient gradually decreases. The data are interpolated to obtain the variation relationship between the convective heat transfer coefficient and the wire diameter at any pressure, as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 6. According to Figure 7, the variation curves of the convective heat transfer coefficient with the wire diameter at the pressures of 75.35 kPa and 19.75 kPa are obtained, as shown in Figure 8.Under the premise that the arrangement of the harness is determined (the wire harnesses on the aircraft are basically arranged in a near-circular shape), a typical one is selected, and a finite element model is established to carry out the solution of the convective heat transfer system. Take a harness composed of 19 wires as an example, as shown in Figure 9.According to the constraints of the outer envelope size of the harness and the constraints of the wire model and quantity in the harness, the geometric model of the harness is established. When converting the geometric model to the finite element model, the wire conductor and insulation layer are solid heat transfer, which is easy to reach an equilibrium state, and their thermal power and heat transfer coefficient setting methods are the same as those of a single wire. For the air in the harness, due to the influence of the stacking and gaps of the harness, the flow velocity varies at different positions, so that the heat transfer coefficient also changes with the position. In order to simplify the model while ensuring the calculation accuracy, in the finite element model, the air is modeled in layers. According to the number of wire layers in the harness, the air is divided into the same number of layers from the center of the harness outer envelope to the outside, and an equivalent heat dissipation coefficient is set for each layer of air according to the calculation results of the fluid field.Then, the equivalent density and convective heat transfer coefficient of each layer of air in the harness are obtained through fluid field finite element simulation, and each wire is assigned values. After assigning the thermal power and convective heat transfer coefficient to each harness, the temperature matrix of the harness is analytically calculated by a numerical iteration method until each element value in the temperature matrix reaches the convergence condition.

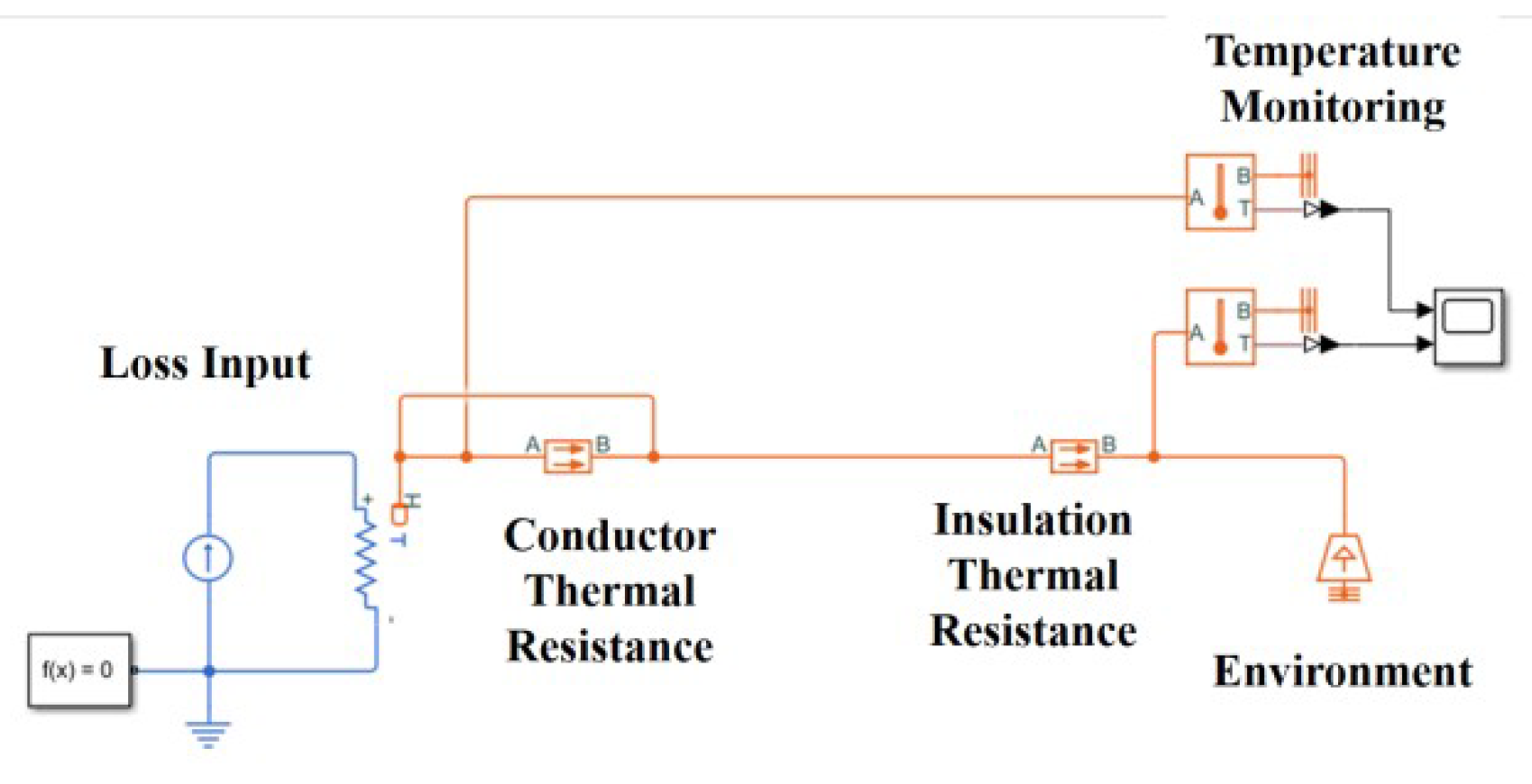

3. Construction of Thermal Resistance Hierarchical Aircraft Wire Thermal Network Mode

- The distribution of the wire core and insulation layer is uneven. The material properties in the finite element will automatically change with temperature, but the thermal network model cannot consider this change, so the relative error is high. Considering that the wire loss is generated in a three-dimensional body, and the heat dissipation ultimately depends on the outer surface of the insulation layer, the larger the diameter, the worse the heat dissipation conditions of the wire, and the more uniform the temperature distribution in the wire. Therefore, the larger the diameter, the smaller the error in the thermal network.

- The thermal resistance change at the interface between the core and the insulation layer, and between the insulation layer and the air layer, as well as the change of materials, cause a certain loss of the wire’s heat dissipation effect. The wire is actually composed of individual cores, not a solid. There are also air gaps between the cores. The traditional thermal network model simplifies the wire conductor into a solid conductor. If each wire core is to be modeled, the thermal network model becomes very complex. Therefore, a new model simplification method needs to be created to ensure the accuracy of the calculation results and achieve model simplicity as much as possible. For this reason, this paper creates a thermal resistance hierarchical simplified thermal network method for the establishment and calculation of thermal network models.

- In order to consider the temperature difference at different positions of the wire, the thermal resistance of the core and insulation layer is layered. The middle value of the corresponding diameter is used as the boundary, and the conductor and insulation layer are each divided into two layers. The inner layer temperature is relatively high, and the thermal resistance is specifically increased.

- A thermal resistance is added between the outer layer of the insulation and the external ambient air to simulate the heat dissipation loss due to changes in the material properties of the insulation and air. At the same time, to simulate the heat dissipation loss due to changes in the material properties of the conductor and insulation layer, the thermal resistance of the outer conductor and inner insulation layer is correspondingly increased.

- In order to ensure the uniformity of thermal resistance parameter verification and enable the same verification method to verify different types of wires, the parameters of the inner conductor, outer conductor, inner insulation, and outer insulation are analyzed. The thermal resistance of the inner conductor is increased by about 6.5 8.5% compared with the theoretical calculation value, and the thermal resistance of the outer conductor and inner insulation is increased by 3.5% 4.5% compared with the theoretical calculation.

4. Research on Aircraft Harness Thermal Network Model

4.1. Construction of Hierarchical Harness Thermal Network Model

4.2. Interlayer Iterative Fast Calculation Method

- Iterative calculation from outside to inside. Current is applied from outside to inside, and the temperature of the outermost layer is first simulated. The outside-to-inside iteration is reflected by overwriting the initial values of the ambient temperature parameters of the inner layer. Since the steady-state temperature is calculated, the temperature influence from the outer layer to the inner layer can be calculated by the average value of the temperatures of two to three adjacent wires. Then, for the next outer layer, the average temperature of the outer layer wires is set as its ambient temperature, and the corresponding current is applied for calculation to obtain the temperature value of the next outer layer in the first iteration from outside to inside. By analogy, until the central wire of the harness is reached, the temperature of the central wire of the harness can be obtained.

- Iterative calculation from inside to outside. From outside to inside is the average value, while the temperature influence of the central wire on the outer layer wires is the temperature rise transfer from a few wires to many wires, and the temperature drop is more obvious. By intercepting the results of multiple groups of finite element simulations, the influence coefficients are fitted into a function of the wire specification, interval distance, and convective heat dissipation coefficient as the correction coefficient for the temperature influence of each layer from inside to outside. Then, the iterative process from inside to outside is carried out. The influence is still reflected in the ambient temperature in the model on the thermal network, so as to realize the temperature simulation of the outer layer wires.

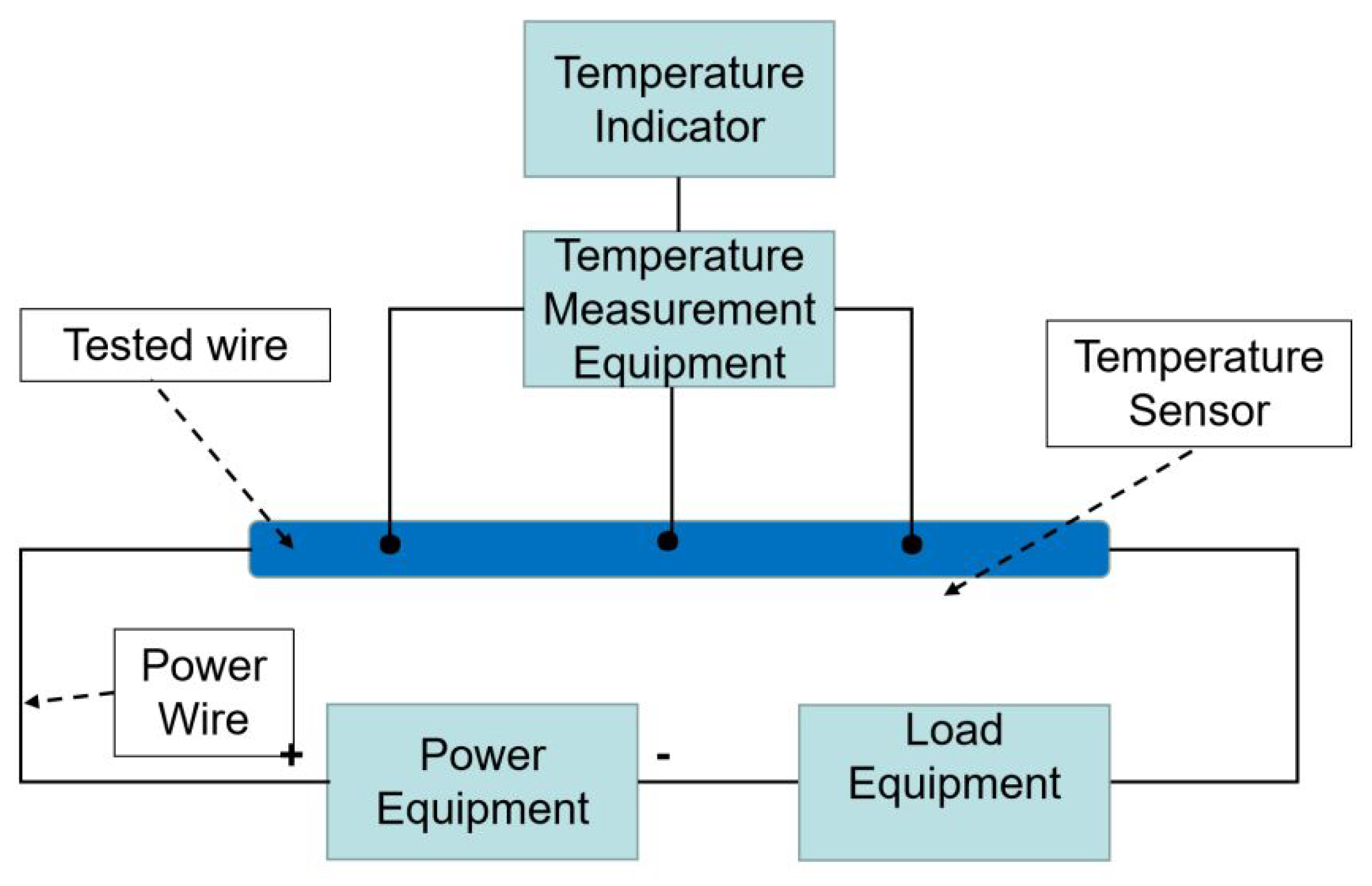

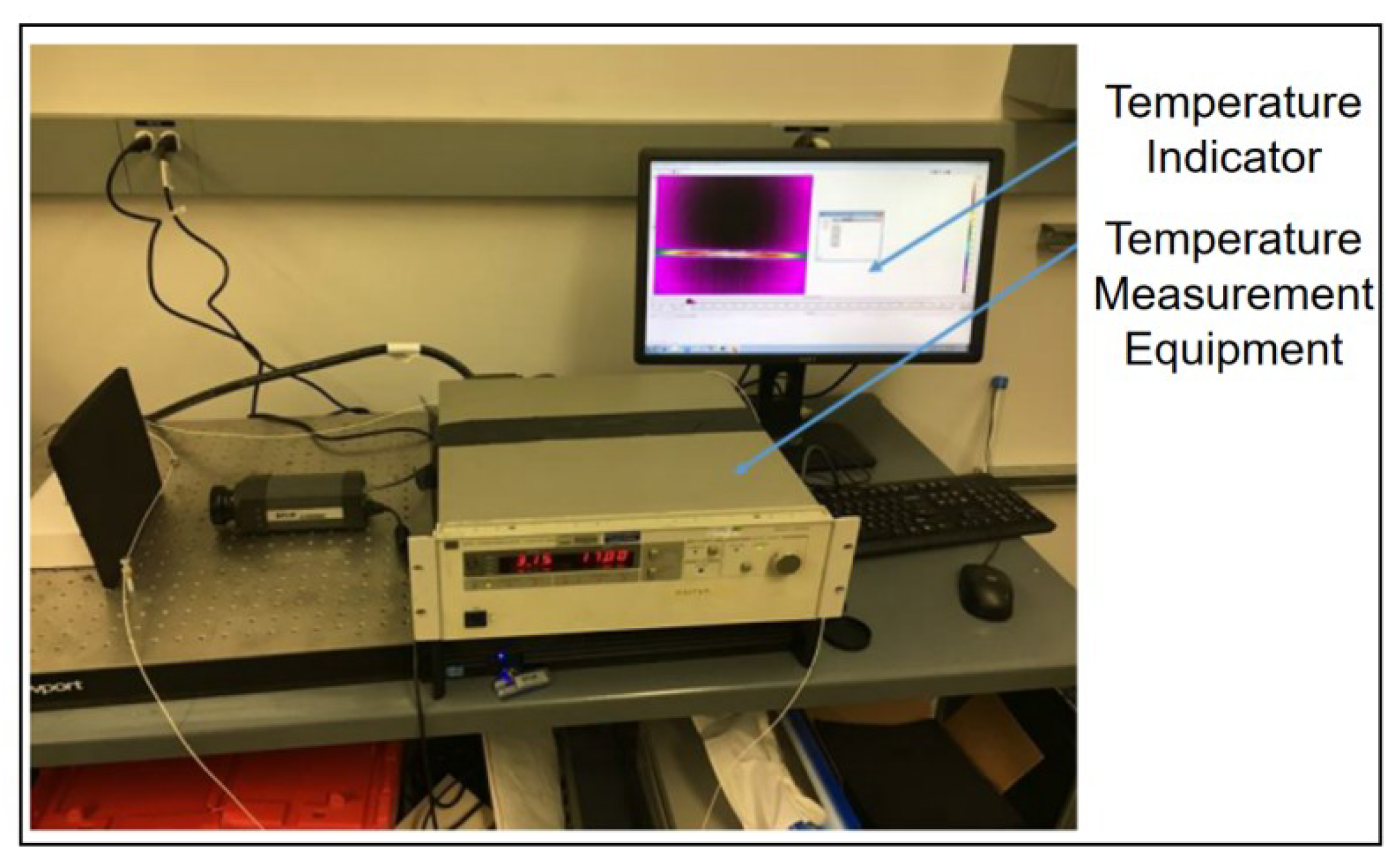

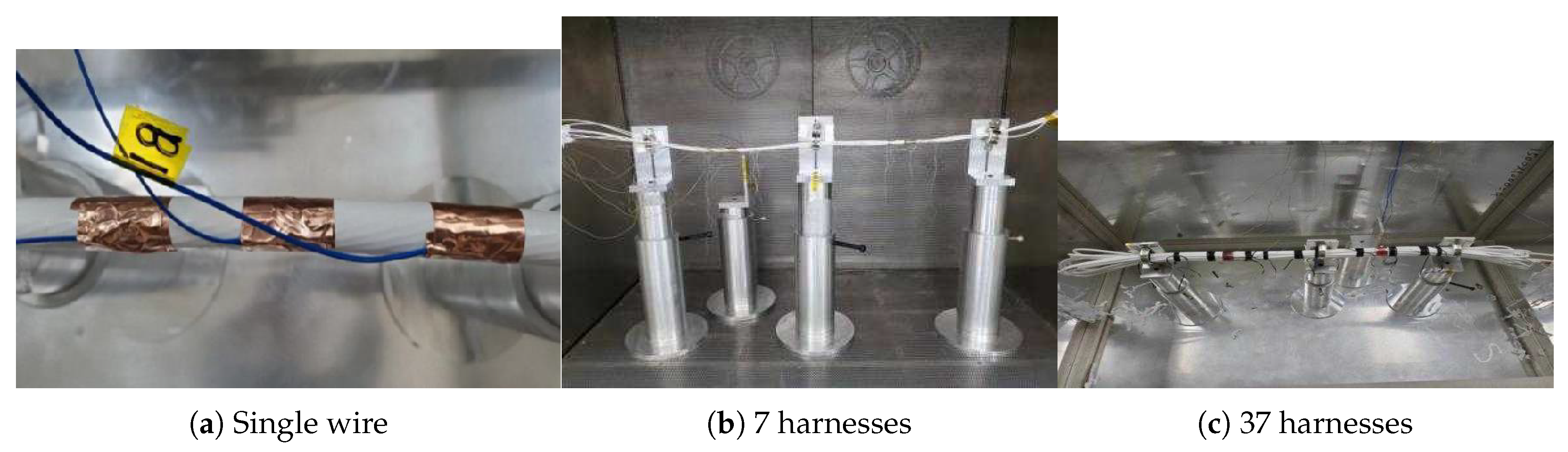

4.3. Comparison of Experimental Tests and Simulation Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EWIS | Electrical Wiring Interconnection System |

References

- Hu, X. Research on Electrical Wiring Design and Verification of Civil Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Science (IC2ECS); IEEE, 2022; pp. 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, V.; Miu, K.; Leger, A. S.; et al. Study of the impacts of ambient temperature variations along a transmission line using temperature-dependent line models. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting; IEEE, 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, V.; Leger, A. S.; Miu, K.; et al. Incorporating temperature variations into transmission-line models. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2011, 26, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigol, O.; Barrett, J. S. Characteristics of ACSR conductors at high temperatures and stresses. IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems 1981, (2), 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wen, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, T. Simulation Analysis of Bundle Conductors Thermal Field in High Voltage Overhead Transmission Lines. Electrotechnics Electric 2017, (03), 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Yao, L.; Zhao, S.; Yu, S.; He, A. Infrared On-line Diagnosis Method for Recessive Defect of Aviation Wire Insulation Layer. Ship Electronic Engineering 2019, 39, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dulaimi, A. A.; Guneser, M. T.; Hameed, A. A.; et al. Adaptive FEM-BPNN model for predicting underground cable temperature considering varied soil composition. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2024, 51, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, S. M.; Black, W. Z. Refinements to the Neher-McGrath model for calculating the ampacity of underground cables. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 1996, 11, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, G. J.; Coates, M. Mohamed ampacity calculations for cables in shallow troughs. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2010, 25, 2064–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60287-1-1:1994 Calculation of the current rating of electric cables, part1: current rating equations (100% load factor) and calculation of losses, section 1: general; International Electrotechnical Commission: 1994.

- IEC 60287-2-1 AMD 1-2006 Electric cables-calculation of the current rating-part 2-1: thermal resistance; calculation of thermal resistance; amendment 2; International Electrotechnical Commission: 2006.

- Henke, A.; Frei, S. Transient temperature calculation in a single cable using an analytic approach. Journal of Fluid Flow, Heat and Mass Transfer (JFFHMT) 2020, 7, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, A.; Frei, S. Analytical Approaches for Fast Computing of the Thermal Load of Vehicle Cables of Arbitrary Length for the Application in Intelligent Fuses. In Proceedings of the VEHITS; 2021; pp. 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Benthem, R.; Grave, W.; Doctor, F.; et al. Thermal analysis of wiring bundles for weight reduction and improved safety. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2011; p. 5111. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, L.; Gang, L.; Yu-ting, L.; et al. Study on thermal model of dynamic temperature calculation of single-core cable based on Laplace calculation method. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Electrical Insulation; IEEE, 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chenzhao, F.; Wenrong, S.; Lingyu, Z.; et al. Research on the fast calculation model for transient temperature rise of direct buried cable groups. In Proceedings of the 2018 12th International Conference on the Properties and Applications of Dielectric Materials (ICPADM); IEEE, 2018; pp. 646–652. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, R.; Liang, Y.; Fu, C.; et al. Rapid calculation model for transient temperature rise of complex direct buried cable cores. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, Y. Research on the rapid calculation method of temperature rise of cable core of duct cable under emergency load. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wire Gauge | 260℃ Experimental Test Current (A) | FEM Simulation Current (A) | Thermal Network Model Simulation Current (A) | FEM Model Error (%) | Thermal Network Model Error(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWG4 | 284.2 | 288.4 | 269.7 | 1.478 | 5.10 |

| AWG12 | 78.9 | 80.9 | 74.5 | 2.535 | 5.58 |

| AWG12 | 30.0 | 31.8 | 28.3 | 6.000 | 5.67 |

| Power-on Condition | Tested(℃) | FEM(℃) | Thermal Network Model Simulation Current (A) | FEM Model Error (%) | Thermal Network Model Error(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central 43.66A | |||||

| Peripheral 0A | 171.01 | 178.6 | 180.4 | 4.4 | 5.5 |

| Central 43.66A | |||||

| Peripheral 9.1A | 260.89 | 268.7 | 271.6 | 3.0 | 4.1 |

| All 10.5A | 152.86 | 158.5 | 159.4 | 3.7 | 4.2 |

| All 12.3A | 200.2 | 208.2 | 210.6 | 4.0 | 5.1 |

| All 14.1A | 257.26 | 268.1 | 269.0 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| Power-on Condition | Tested(℃) | FEM(℃) | Thermal Network Model Simulation Current (A) | FEM Model Error (%) | Thermal Network Model Error(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central 38.93A | |||||

| Peripheral 0A | 173.82 | 180.5 | 185.2 | 3.843 | 6.56 |

| Central 38.93A | |||||

| Peripheral 6.2A | 263.08 | 271.6 | 284.7 | 3.239 | 8.21 |

| All 7.4A | 150.5 | 155.1 | 161.5 | 3.056 | 7.31 |

| All 8.7A | 200.7 | 207.9 | 213.5 | 3.587 | 6.38 |

| All 10.05A | 261.72 | 269.4 | 281.3 | 2.934 | 7.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).