1. Introduction

The Chicxulub asteroid impact in Yucatán 66 million years ago released intense heat, vast quantities of dust, and climate-altering gases, initiating abrupt atmospheric changes. The collision into carbonate-rich terrain injected exceptionally high levels of CO2 and particulates into the atmosphere, making this impact more biologically important than other large impacts (Rampino, 2020). Simulations suggest a collapse of photosynthetic activity lasting nearly two years, followed by prolonged warming driven by carbon dioxide from vaporized rocks (Senel et al., 2023). These changes triggered a dramatic decline in water quality and chemistry in both marine and freshwater systems, severely affecting aquatic life. On land, dust, fires and altered soil chemistry caused widespread vegetation loss. This vegetation collapse undermined food webs, causing the extinction of many herbivores and predators, and the effects of this global event are evident in fossil records from as far as Patagonia and New Zealand (Carvalho et al. 2021). Despite its scale, the impact’s consequences for soil invertebrates, including Onychophora, remain largely unexplored.

However, this full-extinction interpretation, until recently widely accepted among researchers, has been challenged in later years, among others, because of the “Fern Spike” phenomenon. Recent evidence from Tanis, North Dakota, suggests that ferns began growing even during the deposition of the clay layer marking the K-Pg boundary—thought to have formed within minutes or hours of the Chicxulub impact—indicating a faster recovery of certain plant species than previously assumed (Berry, 2023).

Fossil data also indicate that arboreal mammals and marine substrate invertebrates were not so strongly affected by the asteroid’s impact (Hughes et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Tovar et al., 2022). Recent paleoclimatological evidence, including CO2 variations, also suggests that the asteroid’s effects may have been less severe than traditionally portrayed (Wang et al., 2024). Recovery rates varied geographically: regions closer to the impact suffered significant biodiversity loss, taking 1.6 to 10 million years to recover, but coastal areas recovered faster and more distant regions fared better, with Patagonia recovering in 4 million years and New Zealand experiencing only moderate changes (Carvalho et al., 2021).

Although Onychophora are ancient in origin and globally distributed, their fossil record is extremely sparse due to their soft-bodied nature, which limits preservation. Most fossil taxa that superficially resemble Onychophora and are commonly referred to as “lobopodians” cannot be reliably assigned to the phylum (Garwood et al. 2016) and are therefore excluded from the present study. As noted by Giribet et al. (2018) and others, no unequivocal onychophoran fossils from the Mesozoic or Cenozoic have been found in the Americas. This absence of direct fossil evidence —particularly across major extinction boundaries such as the K–Pg —needs alternative approaches to assess survival and biogeographic continuity. In this context, phylogeographic patterns and molecular data remain primary tools for reconstructing the evolutionary history of the group and its relationship with the asteroid impact extinctions.

This study investigates whether the Chicxulub impact caused the extinction of Onychophoran lineages in the regions associated with the Caribbean Sea, the area closest to the crater. We test this hypothesis by comparing the timing of diversification in extant taxa—based on published DNA phylogenies—with the timing of the impact. If the impact eliminated local populations, clades from the area would show the effects in their diversification trends. Instead, our results indicate continuity across the K–Pg boundary, suggesting that onychophorans survived the event and that their current distribution reflects long-term persistence rather than post-event recolonization.

2. Materials and Methods

Due to the extreme rarity of Onychophoran fossils—and full absence in extinction boundaries such as the K–Pg—this study relies on DNA phylogenies and biogeographic reconstructions using fossil evidence from other co-distributed taxa to infer habitat conditions and extinction risk. This approach currently represents a reasonable strategy for soft-bodied taxa lacking fossil records.

2.1. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

We conducted a comprehensive search of published phylogenies, biogeographic syntheses, and geological reports relevant to Onychophoran distribution and diversification in the Americas. Databases included Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, with key terms “Onychophora,” “phylogeny,” “K-Pg extinction,” and “Chicxulub.” Studies were selected if they: (1) presented DNA-based phylogenies with clear clade divergence estimates; (2) included Caribbean, Central American, or South American taxa; or (3) provided geological or ecological context relevant to Onychophoran habitats.

2.2. Phylogenetic and Biogeographic Framework

The phylogenetic topology was based on published molecular trees using mitochondrial and nuclear loci (e.g., COI, 18S, 28S), primarily following the chronogram proposed by Giribet et al. (2018), which was also cross-validated with trees presented by Baker et al. (2021) and Sato et al. (2024). Divergence times were interpreted according to the calibrations and molecular clock models used by Baker et al. (2021). The tree was manually simplified to facilitate comparison with geological reconstructions of the Caribbean region. No new molecular data were generated in this study.

2.3. Mapping and Impact Zone Inference

To reconstruct the paleogeography corresponding to the time of the asteroid impact (66 Ma), we used the open-source software GPlates (GPlates Consortium,

www.gplates.org), which allows for the visualization and reconstruction of past plate tectonic configurations. We employed datasets from the PALEOMAP Project (Scotese, 2021), specifically the rotation model PALEOMAP_PlateModel.rot and plate geometry file PALEOMAP_PlatePolygons.gpml, which are publicly available through the GPlates data portal (

https://www.gplates.org/data/). The reconstruction at 66 Ma was performed in GPlates and exported as ESRI shapefiles. These shapefiles were subsequently imported into R (R Core Team, 2024) using the package sf (Pebesma, 2018), which enabled spatial visualization and analysis. This process allowed us to overlay geographic features of interest, such as the Chicxulub crater location, and examine the distribution of emergent landmasses and potential impact-affected areas during the Cretaceous–Paleogene transition.

The spatial extent of the Chicxulub impact zone was obtained from geophysical studies, crater modeling, and ejecta distribution maps from the literature, as detailed in figure captions. Spatial congruence was assessed qualitatively, considering both modern elevation and paleo-environmental conditions, also detailed in figure captions. All the images presented here are from sources with CC BY licenses, or remade based on published maps, and used according to the norms of those licenses (each figure caption includes the pertinent information).

2.4. Limitations

No fossil data were available for the taxa and time period under consideration. However, phylogenetic continuity and biogeographic congruence provide indirect evidence of lineage survival. All analytical conclusions are drawn with this limitation in mind.).

3. Results

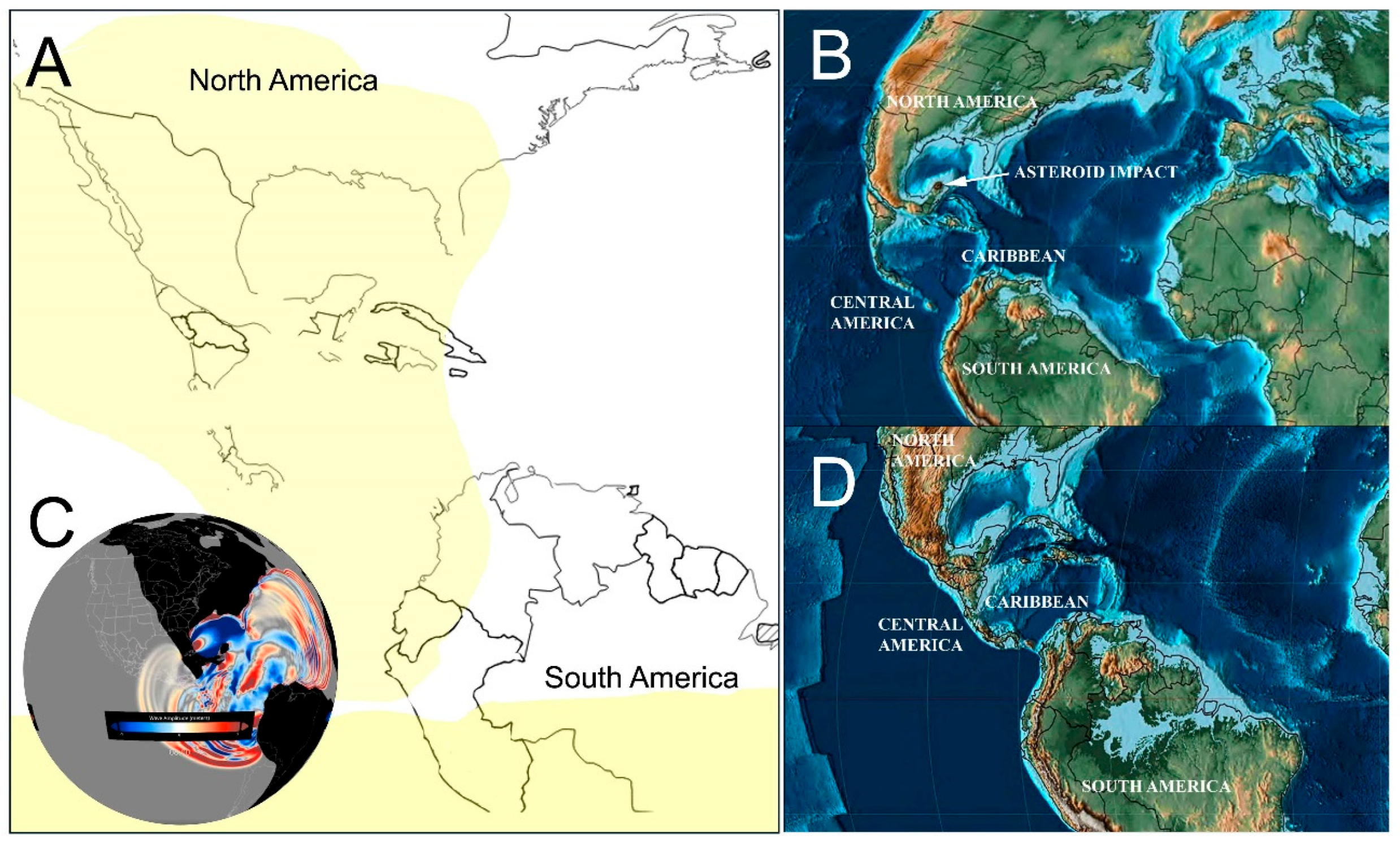

At the time of the impact, many lowland areas were underwater and there was no land connection between South and North America, conditions that were affected by asteroid impact and later geologic evolution (

Figure 1 A-D). There are no fossil onychophorans from this period and area, but they are thought to have occurred all the way from Brazil to Mexico, including whatever was emergent in the Caribbean and Central American region (Baker et al., 2021).

While there has been speculation about 1.5 km tall tsunamis, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration wave simulations indicate that some coastal and lowland ecosystems were affected by far smaller waves: 3 to 20 m waves in Mexico and Caribbean islands and even lower waves in Colombia (Ward 2012). Most of Mexico and South America, and high parts of Jamaica, Puerto Rico and Cuba were free of tsunami effects (

Figure 1C).

The first minutes after the impact may have also produced high temperatures that could ignite vegetation (Santa Catharina et al. 2022). Potentially affected were parts of the USA, all of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean; the Andean region and a wide belt along the tropical South America (

Figure 1A), but some authors state that there is no evidence of global fires in the fossil record of that period (Morgan et al. 2013, Carvalho et al., 2021).

Marine communities quickly recovered even at the very site of the impact: before the impact, the ocean floor was dominated by burrowing animals; immediately after the impact, the number and variety of their traces dropped for a short time; but, within a few years, the same species moved back in from less affected areas (Rodríguez-Tovar, et al. 2022).

In the first years after the fall of the asteroid, terrestrial ecosystems were marked by an abundance of fungi, which possibly were feeding on the abundant corpses left by the impact, and ferns also became abundant (their spores persist viable for years even if exposed to high temperatures, see Paul et al. 2014).

3.1. Onychophora Radiation Before the Asteroid Impact

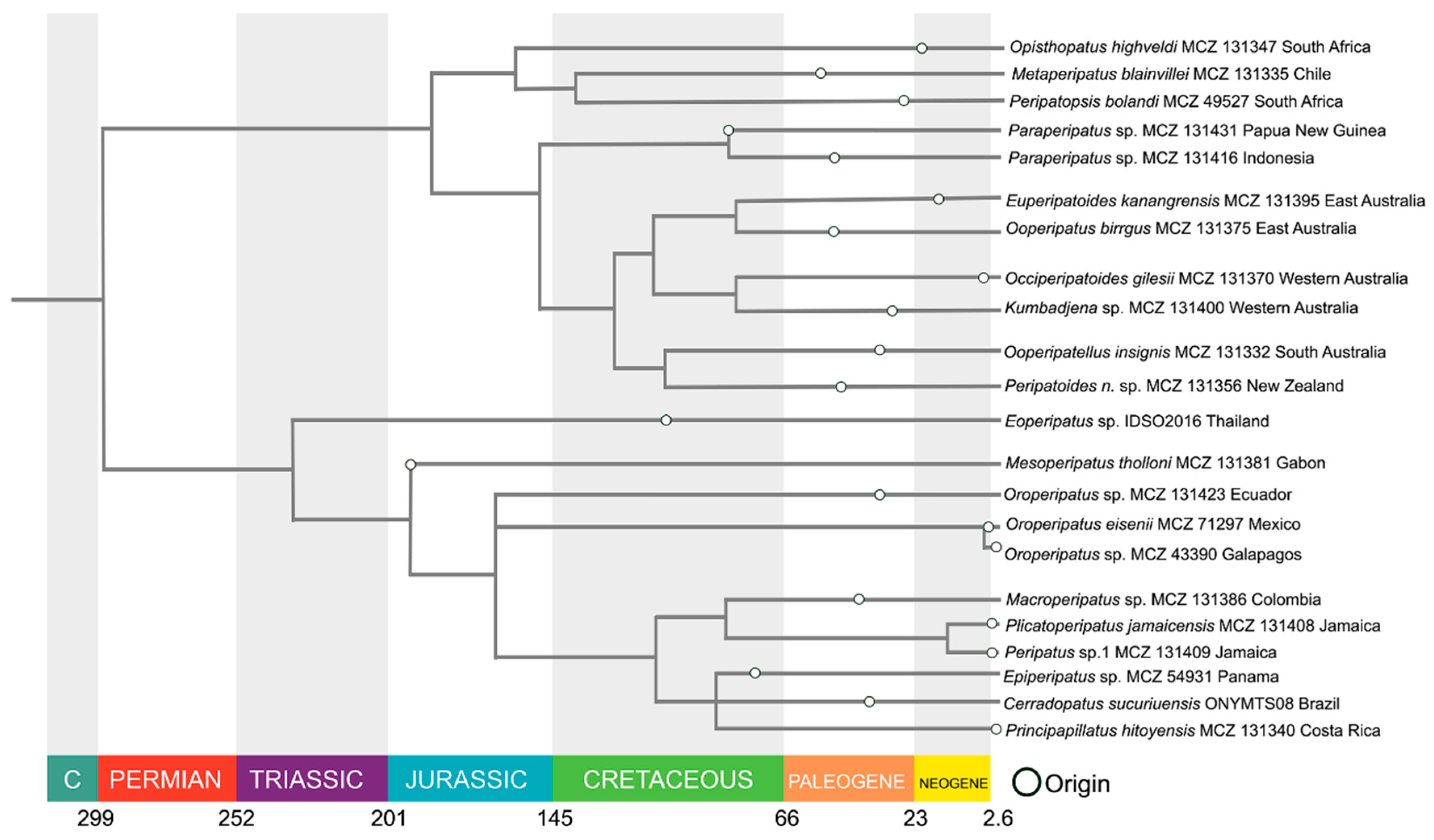

This section is based on the DNA phylogeographic tree (

Figure 3), Scotese (2014) maps and climatic and vegetation reconstructions by Carvalho et al. (2021) and Wang, et al. (2024). Paleobiogeographic reconstruction indicates that the last common ancestor of the extant Onychophoran fauna in the Americas likely lived during the late Jurassic. At that time, the supercontinent Gondwana was still largely intact, and the regions in question—South and Central America—were characterized by a variety of warm, humid climate sites and drier and cooler habitats in higher areas.

From this ancestral late Jurassic lineage, two principal clades appear to have diverged, one on the Pacific side and other in what today is the Atlantic side of the continent. The first lineage gave rise to the velvet worm species currently inhabiting the Pacific regions of Colombia and Ecuador. Within this group, a notable subclade includes several Oroperipatus species, which are hypothesized to have dispersed by sea to the Galápagos Islands and the Pacific coast of Mexico. From the Mexican Pacific, the lineage appears to have expanded eastward, though the precise dispersal routes remain speculative. These regions would have featured high humidity and dense vegetation, favoring onychophoran survival.

The second Jurassic lineage, distant from the coast, is inferred to be the ancestor of all extant Peripatidae distributed around the Caribbean Basin and the Atlantic coast of South America. This group underwent further diversification during the early Cretaceous and still inhabits the Atlantic coast of Brazil and Caribbean coast of Central America and Mexico. The lineage underwent a further radiation during the Cretaceous. This era saw high sea levels, continued tropical conditions, and floristically rich lowland forests.

Its radiation resulted in three geographic subgroups:

A group comprising species from Trinidad, Tobago, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Belize. Colonization events in Caribbean islands likely occurred via overwater dispersal. Notably, the origin of the Belize population may have been the Caribbean islands rather than mainland Central America. These islands at the time were emergent volcanic arcs or proto-islands covered in humid forest and perhaps periodically connected via lowered sea levels (

Figure 1D).

A second subgroup includes species from Brazil and the Guianas. From this region, colonization possibly extended to Panama and Hispaniola, though these connections remain uncertain and require further phylogeographic verification. The Amazonian region during this period was an expansive lowland tropical forest, crisscrossed by large river systems and subject to wet equatorial climates (

Figure 1D).

The third subgroup consists of species from Panama, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean coast of Mexico. These taxa show phylogenetic affinities to species in Venezuela, Brazil, and the Guianas, although the precise directions and timings of these colonization events are still unresolved. Central America during the late Cretaceous was characterized by narrow land bridges and scattered volcanic islands with warm, moist conditions suitable for Onychophoran dispersal and persistence (

Figure 1B) and later the land connections would increase (

Figure 1D) until the land connection became complete as known in the present.

These patterns underscore a complex history of both vicariance and overwater dispersal shaping the distribution of American velvet worms. Climatic and vegetational continuity across these regions likely played a key role in facilitating the persistence and radiation of Onychophoran lineages. If the asteroid impact had caused the extinction of even some of these populations, the current populations would be the result of recolonization from surviving populations and these new populations would have several genetic markers that will be analyzed in the discussion section of this paper.

3.2. Onychophorans on Islands

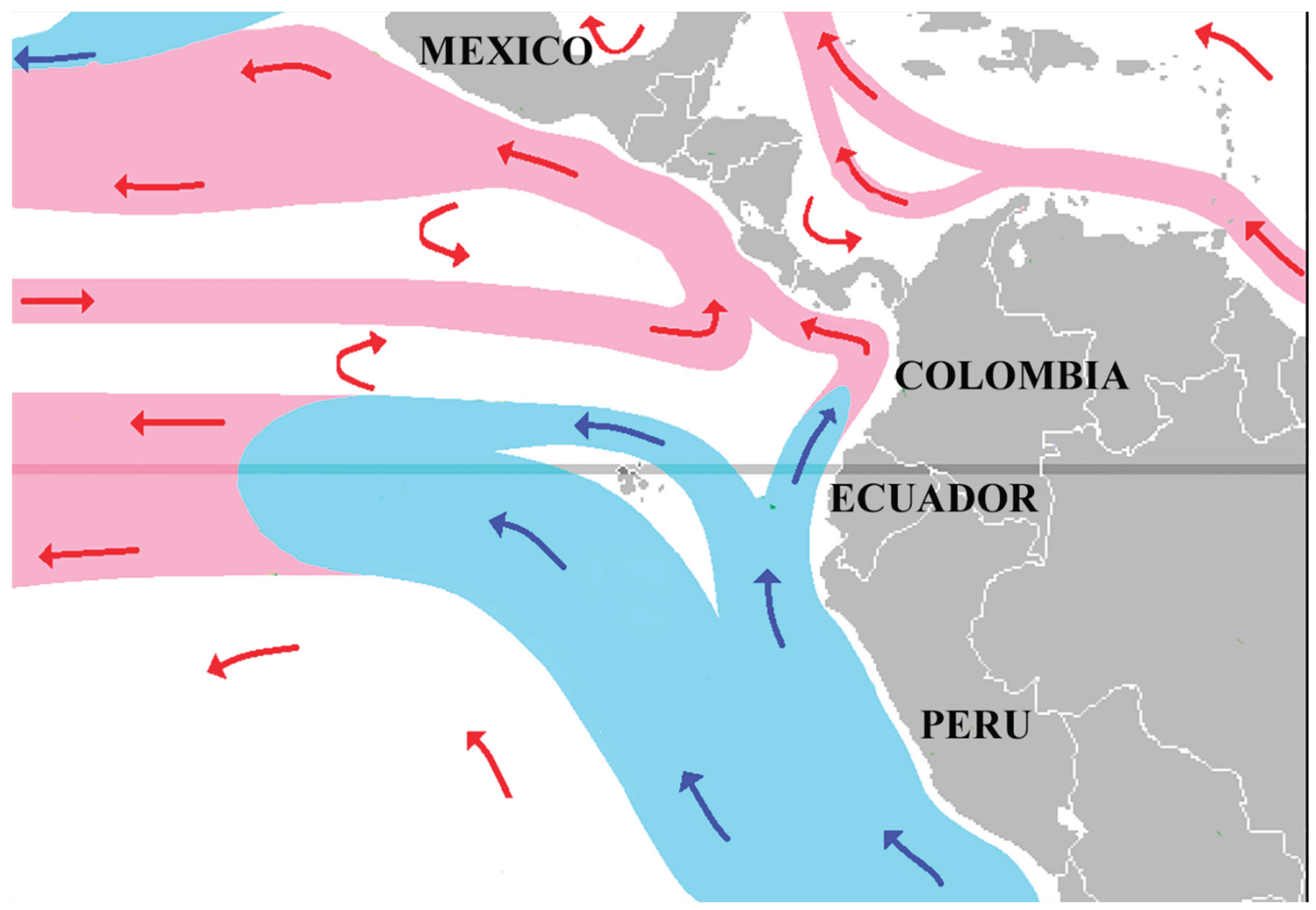

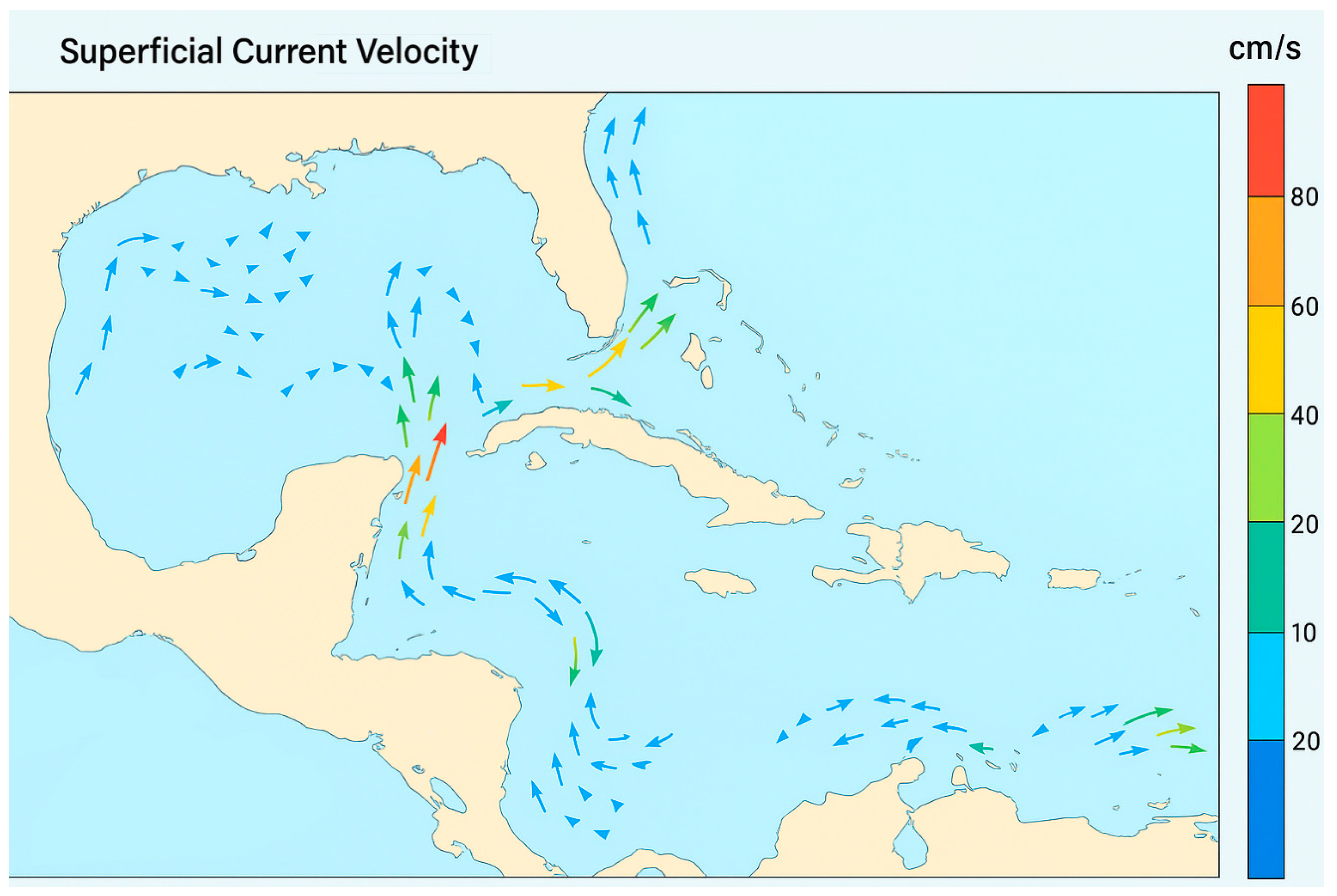

Additionally to slow overland dispersal, there are fast dispersal possibilities by natural rafts moving along rivers and the ocean: while onychophorans are physiologically vulnerable to saltwater immersion, experimental and observational data confirm their buoyancy in freshwater and their presence on natural rafts (Monge-Nájera 1995; Marshall & Martin 2020). In this case, overwater dispersal remains the most parsimonious explanation for several Caribbean colonization events, especially in the absence of historical land bridges or anthropogenic transport, and given the congruence with prevailing marine currents (Carracedo-Hidalgo et al. 2019). Currently, onychophorans are primarily found throughout the Lesser Antilles, extending to Puerto Rico and Jamaica, but are absent from Cuba. The direction of marine currents (

Figure 2) suggests that species from the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico could have arrived from Brazil and Jamaican onychophorans from Venezuela. The species from Hispaniola could have arrived from Venezuela or Brazil because currents from both places reach Hispaniola. Currents would also explain any species from Costa Rica and Panama found to be closely related to species in the Magdalena River basin, Colombia (Monge-Nájera 2019), and this seems compatible with the phylogeny presented in

Figure 3.

The ancestors of species from southern Mexico probably reached Mexico from Central America by land, but natural rafts along marine currents could theoretically have taken species from Ecuador to the Pacific coast of Mexico, matching the local current directions (

Figure 4). This would require the velvet worms to survive on the raft for at least two weeks: although it may seem improbable for these animals to survive oceanic rafting, there is evidence that they can from Galápagos onychophorans (Espinaza et al. 2015) and they are known to recover after two weeks without food (Read and Hughes, 1987).

Overall, the affinities of all species, as summarized here from several studies (Giribet et al. 2018, Baker et al. 2021 and Sato et al. 2024) fit the model presented here and a pattern of phylogenetic divergence that closely parallels geographic separation (Monge-Nájera 1995). Furthermore, even though they were far from the impact site, species in Africa, Asia and Oceania do not lose branches or show any novel trend at the time of the impact (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of the neotropical onychophorans (based on Giribet et al.2018).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of the neotropical onychophorans (based on Giribet et al.2018).

Figure 4.

Marine currents connecting Ecuador with the Pacific coast of Mexico in July of each year (modified from Maulucione, Wikimedia Foundation, CC BY License).

Figure 4.

Marine currents connecting Ecuador with the Pacific coast of Mexico in July of each year (modified from Maulucione, Wikimedia Foundation, CC BY License).

4. Discussion

By integrating data on paleogeography, tsunami dynamics, wildfire potential, and marine currents with phylogenetic analyses, this study tests the hypotheses that the Chicxulub asteroid impact caused the extinction of onychophorans in the regions surrounding the impact.

However, the current phylogenetic structure and geographic distribution of American Onychophorans strongly suggest that all the extant lineages existed before the impact and that they persisted through the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K-Pg), surviving the global extinction event triggered by the Chicxulub asteroid impact. If the Chicxulub impact had resulted in the complete extinction of Onychophoran populations across most of the continent —with survival limited to the Andean region, where climatic buffering and geographic isolation softened the ecological consequences of the asteroid (Domic and Capriles, 2021; Jablonski and Eddie, 2025)— the modern tree would likely exhibit:

A deep crown node representing a single surviving Andean lineage, followed by a relatively recent and shallow radiation into other regions during the Paleogene and Neogene, a general expectation for bottleneck and re-radiation. There would be low genetic divergence among extant species outside the Andes, indicating a post-extinction dispersal and recolonization (Löytynoja et al., 2023).

Loss of deep branching Caribbean and Central American lineages, and an absence of distinct clades in areas closest to the impact site, such as the Caribbean islands and Mesoamerica (not the case: Baker et al., 2021).

Instead, the phylogeny reveals multiple deeply divergent clades across a broad geographic range—including Central America, the Caribbean, northern South America, and Brazil—that trace their origins to the late Jurassic and Cretaceous, well before the K-Pg boundary. This is implied by our phylogeographic analysis and matches previous works on the phylogeny of the group (Oliveira et al., 2012; Giribet et al., 2018; Baker et al., 2021). Extant onychophoran clades do not cluster in a way that would suggest recent common ancestry from a single population (this is also supported by the strong tree produced by Baker et al. 2021). Rather, their divergence patterns correspond closely to the geological and biogeographic history of their respective regions, implying in situ survival across a mosaic of habitats.

This distributed survival implies that Onychophoran species survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event throughout their entire range, from Mexico to Brazil and across the Caribbean and coincides. Several factors may have contributed to their persistence, including their soil-dwelling habits, low metabolic requirements, and ecological specialization in microhabitats buffered from broader climatic and ecological disturbances thanks to their underground location (Monge-Nájera, 1995). In forested regions, subterranean and moist leaf-litter microenvironments may have offered sufficient food and refuge to protect populations from the worst post-impact effects, such as atmospheric dust and loss of photosynthesis-driven food chains (Monge-Nájera et al., 1996). Recent evidence suggests that volcanic activity may have caused repeated, short-term global cooling events before the asteroid impact (Callegaro et al. 2023); if this is correct, neotropical organisms, from fungi and plants to onychophorans and vertebrates, could have developed adaptations that would later help them survive the effects of the asteroid, for example dormancy, diapause, hibernation, antifreeze molecules, insulation and burrowing.

While the most parsimonious interpretation of the current phylogeny is broad geographic survival, alternative explanations must also be considered. One possibility is multiple independent recolonizations of now-distinct regions from unknown areas. However, this would require post-extinction dispersal patterns and timing that are inconsistent with both the depth of divergence observed and the biogeographic barriers that would have constrained long-distance movement (e.g., ocean gaps, mountain ranges) (Baker et al., 2021). Another less likely interpretation is cryptic extinction and replacement, where early lineages were replaced by newer arrivals with similar genetic signatures—yet such a pattern would likely produce phylogenetic anomalies or convergence artifacts, which are not observed in current molecular data (Baker et al., 2021). The phylogeographic structure of American Onychophorans—particularly the presence of deep lineages across multiple regions affected by the Chicxulub impact—is consistent with models of complex biogeographic history involving both vicariance and dispersal, as known in other organisms from the same regions (Villalobos, 2022), perhaps associated with cycles of range expansion and contraction that can explain the current complexity of their genetic constitution (Halas, Zamparo, & Brooks, 2005).

5. Conclusions

Until onychophoran fossils are found in the Caribbean region, the reasons for their loss or preservation in the K-Pg mass extinction must be assessed only on the basis of their own DNA and fossil evidence from other taxa that allows the reconstruction of their paleobiogeography, which can be assessed with sufficient rigor to justify the effort.

Contrary to our hypotheses about their extinction and later repopulation of the regions most affected by the asteroid impact, the current geographic and phylogenetic structure of neotropical Onychophorans supports the interpretation that multiple lineages survived the K-Pg mass extinction in situ, preserving a rich and regionally structured evolutionary legacy that predates the asteroid impact. This underscores the importance of local habitat stability in the long-term survival of ancient terrestrial invertebrate lineages.

We hope this article will inspire new analyses of fossil records to clarify the extent of wildfire effects and ecosystem recovery timelines in Mesoamerica and the Caribbean; exploration of genetic sequences in understudied places like Brazil, Venezuela, Central America and Mexico; and novel work on the survival mechanisms of onychophorans, particularly their ability to persist on natural rafts and withstand prolonged periods in post-impact conditions.

Author Contributions

Both authors participated equally in all stages of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank Bernal Morera-Brenes, Federico Villalobos and Roberto Cordero (UNA, Heredia, Costa Rica) for useful comments on this subject, and Gonzalo Giribet (Harvard, Massachusetts) for providing us the phylogenetic tree that was the basis for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, C.M.; Buckman-Young, R.S.; Costa, C.S.; Giribet, G. Phylogenomic analysis of velvet worms (Onychophora) uncovers an evolutionary radiation in the Neotropics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 5391–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, K. Can the initial phase of the K/Pg boundary fern spike be reconciled with contemporary models of the Chicxulub impact? New insights from the birthplace of the fern spike concept. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 2023, 309, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, S.; Baker, D.R.; Renne, P.R.; Melluso, L.; Geraki, K.; Whitehouse, M.J.; De Min, A.; Marzoli, A. Recurring volcanic winters during the latest Cretaceous: Sulfur and fluorine budgets of Deccan Traps lavas. Science Advances 2023, 9, eadg8284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo-Hidalgo, D.; Reyes-Perdomo, D.; Calzada-Estrada, A.; Chang-Domínguez, D.; Rodríguez-Pupo, A. Caracterización de las corrientes marinas en mares adyacentes a Cuba. Principales tendencias en los últimos años. Revista Cubana de Meteorología 2019, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.R.; Jaramillo, C.; de la Parra, F.; Caballero-Rodríguez, D.; Herrera, F.; Wing, S.; Turner, B.L.; D’Apolito, C.; Romero-Báez, M.; Narváez, P.; et al. Extinction at the end-Cretaceous and the origin of modern Neotropical rainforests. Science 2021, 372, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domic, A.I.; Capriles, J.M. Distribution shifts in habitat suitability and hotspot refugia of Andean tree species from the last glacial maximum to the Anthropocene. Neotropical Biodiversity 2021, 7, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinasa, L.; Garvey, R.; Espinasa, J.; Fratto, C.A.; Taylor, S.; Toulkeridis, T.; Addison, A. Cave dwelling Onychophora from a lava tube in the Galapagos. Subterranean Biology 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giribet, G.; Buckman-Young, R.S.; Costa, C.S.; Baker, C.M.; Benavides, L.R.; Branstetter, M.G.; Daniels, S.R.; Pinto-da-Rocha, R. The ‘Peripatos’ in Eurogondwana?–Lack of evidence that south-east Asian onychophorans walked through Europe. Invertebrate Systematics 2018, 32, 842–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackathorn, E. Tsunami: Asteroid Impact - 66 Million Years Ago. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Maryland; CC BY license. 2023. Available online: https://sos.noaa.gov/catalog/datasets/tsunami-asteroid-impact-66-million-years-ago/.

- Halas, D.; Zamparo, D.; Brooks, D.R. A historical biogeographical protocol for studying biotic diversification by taxon pulses. Journal of Biogeography 2005, 32, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.J.; Berv, J.S.; Chester, S.G.; Sargis, E.J.; Field, D.J. Ecological selectivity and the evolution of mammalian substrate preference across the K–Pg boundary. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 14540–14554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, D.; Edie, S.M. Mass extinctions and their rebounds: A macroevolutionary framework. Paleobiology 2025, 51, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kring, D.A.; Durda, D.D. Trajectories and distribution of material ejected from the Chicxulub impact crater: Implications for postimpact wildfires. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2002, 107, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löytynoja, A.; Rastas, P.; Valtonen, M.; Kammonen, J.; Holm, L.; Olsen, M.T.; Paulin, L.; Jernvall, J.; Auvinen, P. Fragmented habitat compensates for the adverse effects of genetic bottleneck. Current Biology 2023, 33, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.C.; Martin, H. Velvet worm (Phylum Onychophora) on a sand island, in a wetland: Flushed from a Pleistocene refuge by recent rainfall? Austral Ecology 2020, 45, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge- Nájera, J. Phylogeny, biogeography and reproductive trends in the Onychophora. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1995, 114, 21–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Nájera, J. Why are there no onychophorans in Cuba? Revista de Biología Tropical, Darwin In Memoriam Column. 2019. Available online: https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rbt/article/download/36418/37079/119228&ved=2ahUKEwiDqorj1NyJAxVoSjABHVNGN2wQFnoECBUQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3WpX5diAHlEuIi_bi7mhME.

- Monge-Nájera, J.; Barrientos, Z.; Aguilar, F. Experimental behaviour of a tropical invertebrate: Epiperipatus biolleyi (Onychophora: Peripatidae). In Acta Myriapodologica; Geoffroy, J.-J., Mauriès, J.-P., Duy-Jacquemin, M.N., Eds.; Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle; 1996; Volume 169, pp. 493–494. ISBN 2-85653-502-X. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J.; Artemieva, N.; Goldin, T. Revisiting wildfires at the K-Pg boundary. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2013, 118, 1508–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Dixon, K.W.; Miller, B.P. The persistence and germination of fern spores in fire-prone, semi-arid environments. Australian journal of botany 2014, 62, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R Journal 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rampino, M.R. Relationship between impact-crater size and severity of related extinction episodes. Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 201, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, V.S.J.; Hughes, R.N. Feeding behaviour and prey choice in Macroperipatus torquatus (Onychophora). Proceedings of the Royal society of London. Series B. Biological sciences 1987, 230, 483–506. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J.; Kaskes, P.; Ormö, J.; Gulick, S.P.; Whalen, M.T.; Jones, H.L.; Lowery, C.M.; Bralower, T.J.; Smit, J.; King, D.T., Jr.; et al. Life before impact in the Chicxulub area: Unique marine ichnological signatures preserved in crater suevite. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 11376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Catharina, A.; Kneller, B.C.; Marques, J.C.; Mcarthur, A.D.; Cevallos-Ferriz, S.R.S.; Theurer, T.; Kane, I.A.; Muirhead, D. Timing and causes of forest fire at the K–Pg boundary. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 13006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Derkarabetian, S.; Lord, A.; Giribet, G. An ultraconserved element probe set for velvet worms (Onychophora). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2024, 197, 108115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotese, C.R. The PALEOMAP Project PaleoAtlas for ArcGIS, version 2, Volume 2, Cretaceous Plate Tectonic, Paleogeographic, and Paleoclimatic Reconstructions, Maps 16-32. ResearchGate 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotese, C.R. PALEOMAP PaleoAtlas for GPlates. 2021. Available online: https://www.gplates.org/data/.

- Senel, C.B.; Kaskes, P.; Temel, O.; Vellekoop, J.; Goderis, S.; DePalma, R.; Prins, M.A.; Claeys, P.; Karatekin, Ö. Chicxulub impact winter sustained by fine silicate dust. Nature Geoscience 2023, 16, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lande, V.M. Native and introduced Onychophora in Singapore. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1991, 102, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, F. Tree squirrels: A key to understand the historic biogeography of Mesoamerica? Mammalian Biology 2013, 78, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, C. Long-term variations in terrestrial carbon cycles and atmospheric CO2 levels: Exploring impacts on global ecosystem and climate in the aftermath of end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2024, 643, 112177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).