1. Introduction

One of the main applications of quantum information theory is the development of quantum communication protocols [

1,

2]. In such protocols, two legitimate parties, commonly referred to as Alice and Bob, aim to share information securely. Meanwhile, an adversary, known as Eve, attempts to intercept the information without being detected. To establish communication, Alice and Bob agree on a set of quantum states, which are typically chosen to be nonorthogonal. A key property of nonorthogonal quantum states is that they cannot be perfectly distinguishability by any quantum measurement [

3,

4]. This inherent indistinguishability underlies the security of quantum communication protocols, such as the well-known BB84 scheme [

5]. In a typical communication protocol, Alice prepares and transmits classical information encoded in a set of nonorthogonal quantum states. At the distant end of the communication channel, Bob receives the quantum state and performs a measurement to extract the information sent by Alice. The specific quantum measurement employed by Bob is chosen to optimize a predefined figure of merit. For example, he may implement a measurement that minimizes the probability of error in identifying the transmitted states (ME) [

6,

7,

8] or one that allows the extraction of the accessible information (MI) [

9,

10,

11], which quantifies the maximal classical correlation that can be established between the legitimate parties. In general, these correspond to two distinct optimization problems [

12]. However, when the set consists of two pure nonorthogonal states prepared with arbitrary

a priori probabilities, it is known that ME and MI measurements coincide [

4,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The optimization problem consists of finding the optimal set of quantum measurement operators. For minimum error discrimination, the necessary and sufficient conditions that the optimal measurement operators must satisfy are well establish [

6,

7]. In contrast, for the accessible information only necessary condition are known [

6,

16,

17]. Analytical solutions for the ME strategy are available for specific classes of quantum states [

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, the MI optimization problem is significantly more challenging, and exact solutions are known only for a few cases [

22,

23,

24]. Nevertheless, there exists lower and upper bounds for the accessible information [

16,

25,

26], and several results have been reported regarding the number of measurement operators required to implement the MI strategy [

10,

11]. Minimum error discrimination plays a key role in various quantum information processing tasks, including quantum teleportation [

27,

28], entanglement swapping [

29,

30], quantum cryptography [

31] and dense coding [

32], among others. Furthermore, the ME of nonorthogonal states has been successfully demonstrated in several experimentally settings [

12,

33,

34,

35]. On the other hand, the accessible information strategy finds application in quantum cryptography [

16], and its experimental implementation has been reported in specific scenarios [

12].

In this work, we study the minimum error discrimination of a set of N pure, nonorthogonal equidistant quantum states, each prepared with equal a priori probability. We derive the optimum measurement operators and the corresponding success probability for ME, and we also propose an experimental scheme for its implementation. Moreover, we evaluate the quantum coherence, involved in applying the ME strategy to the equidistant states, which has the operational interpretation as a cryptographic randomness gain. We then determine the classical correlations shared between Alice and Bob when the ME strategy is employed. Finally, we study the relationship between classical correlations and quantum coherence within the ME protocol. Interestingly, our results reveal a fundamental trade-off: greater classical information sharing between Alice and Bob corresponds to reduced randomness generation, and vice versa.

This article is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we introduce and describe the set of

N pure, nonorthogonal equidistant quantum states. In

Section 3, we derive the optimal measurement operators and the corresponding success probability for the minimum error discrimination of these states, together with a proposal for their experimental implementation. In

Section 4, we focuses on the analysis of quantum coherence of the set of equidistant states. In

Section 5, We describe the initial and final global states of the composite system shared by Alice and Bob, resulting from the minimum error (ME) measurement performed by Bob. In

Section 6, we study the classical correlations shared between Alice and Bob when ME is implemented by Bob. Moreover, we examine the trade-off between Bob’s information gain and the quantum coherence consumed in the process. Finally, in

Section 7, we summarize our findings and present concluding remarks.

2. Equidistant States

Let us consider a set of N pure, nonorthogonal quantum states denoted by

with

satisfying the following property:

that is, the inner product between any two states in the set depends solely on a single complex number

S or equivalently, on two real parameters: its modulus

and its phase

. Due to this property, the set is referred to as equidistant [

36,

37,

38]. For such a set states, the modulus

is constrained to lie within the interval

, where

is a function of the phase

and the number

N of states in the set, given by

The explicit form of the set of

N pure, nonorthogonal equidistant states is given in [

37] as:

where

N is fixed, and all the real coefficients

in Equation (

3) depend only on the modulus

and the phase

of the inner product

S. These coefficients are given by

Given the symmetry of the equidistant states, as illustrated in Figure 2, we restrict the phase

of the inner product

S to the interval

. Within this interval, the coefficients exhibit an ordering property, namely

and the phases

in Equation (

3) are defined as

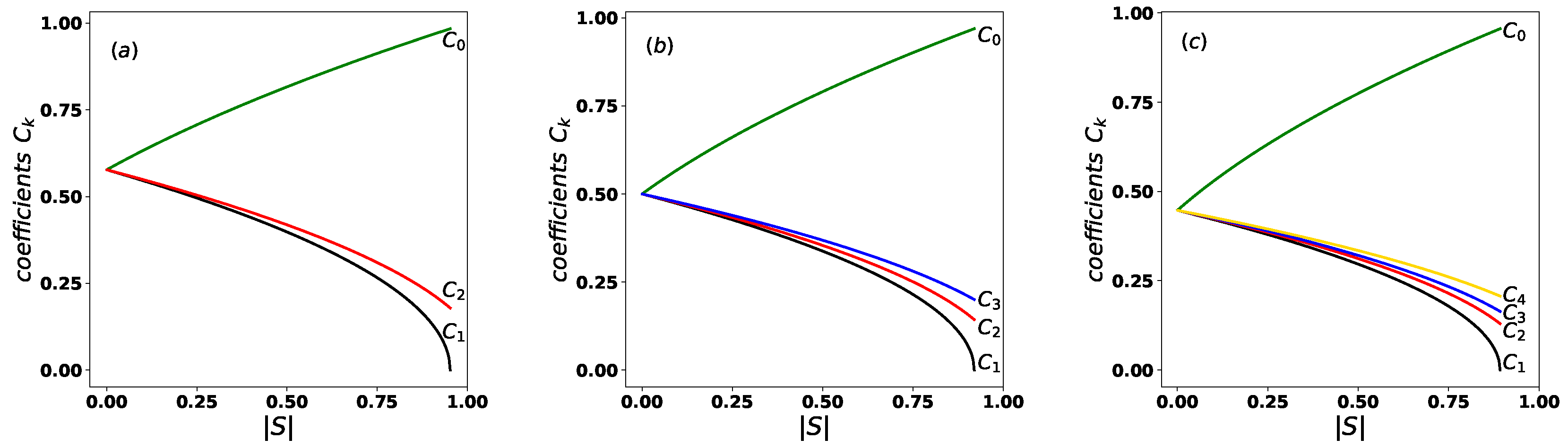

Figure 1 illustrates the ordering of the coefficients

, as defined in Equation (

5), as a function of

, for: (a)

, (b)

, and (c)

, with

. As shown in all cases, the maximum and minimum values of the coefficients correspond to

and

, respectively. Moreover, when the states are orthogonal,

, all coefficients become equal and take the value

, where

N is the number of states in the set.

Given the coefficients

defined in Equation (

4), the equidistant states in Equation (

3) are properly normalized, that is,

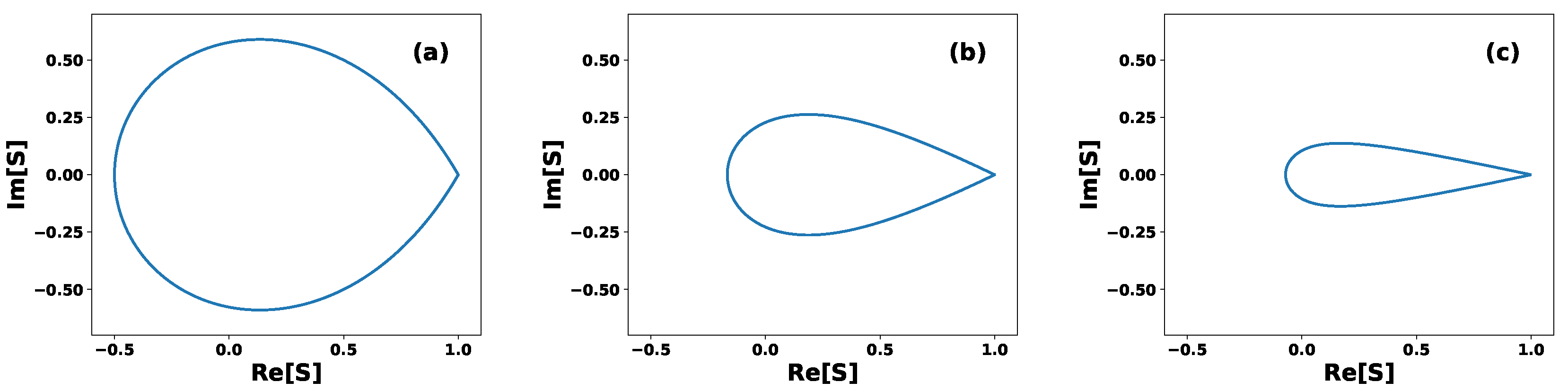

Figure 2 shows, in polar coordinates, the possible values of the inner product

S for sets of pure equidistant states, with: a) N=3, b) N=7 and c) N=15. For a given phase

, the modulus of the inner product

S is constrained to lie within the interval

. The blue line in

Figure 2 corresponds to the case

, for which the set of equidistant states becomes linearly dependent. For instance, when

, the condition

implies that all

N states are all identical to

. In this case, the states span a one-dimensional Hilbert space and are therefore linearly dependent. For any other value of

, the condition

defines a set of

N equidistant states that are linearly dependent and span an

dimensional Hilbert space. On the other hand, the set of pure equidistant states is linearly independent when the modulus of the inner product lies within the region bounded by the blue line, i.e., for

. In this case, the states span an

N-dimensional Hilbert space.

Figure 2 illustrate how the range of possible values for

decreases as the the number of states

N increase. This implies that, as

N increases, the phase

of the inner product becomes progressively less relevant, ultimately leaving only the case

in the limit of large

N.

Another important property of the set of equidistant states is that there exist a unitary transformation

U that generates the entire set from a single state, namely

where

with

defined in Equation (

6), and

is referred to as the fiducial state. Applying the unitary transformation

N times yields

Under the condition , the set of equidistant states is also symmetric. This occurs when or . In the following, we provide a more detailed description of these two particular sets of states.

For

, the inner product is a real and positive number, with

and

. In this case, the fiducial state takes the form

where the coefficients are given by

and

. The set of N equidistant states is linearly independent (dependent), and spans a N-dimensional( 1-dimensional) Hilbert space, if

, respectively.

For

, the inner product is a real and negative, with

and

. The fiducial state in this case takes the form

with coefficients

and

. Here, the set of N equidistant states is linearly independent (dependent), and spans an N-dimensional (N-1 dimensional) Hilbert space, if

, respectively.

3. Minimum Error Discrimination

Having defined the set of

N pure nonorthogonal equidistant states

in [

36] and described it in detail in [

38], we now study its quantum state discrimination under the minimum error strategy. To this end, we assume that each state

is prepared with equal

a priori probability, i.e.,

for

.

In general, the necessary and sufficient conditions for optimum discrimination with minimum error among N density matrices

, each prepared with arbitrary

a priori probabilities

, were found by Holevo [

6] and Yuen [

7]. These conditions are given by

where

are the detection operators to be determined for the optimum discrimination of the state

. In the particular case of a set of

N pure nonorthogonal equidistant states prepared with equal

a priori probability, the above conditions are satisfied when the detection operators are given by

where the states

are defined as

and form an orthonormal basis generated by the discrete Fourier transform

F acting on the N-dimensional Hilbert space, i.e.,

, with

Thus, there is a one by one correspondence between each orthonormal states

and one state from the computational basis

. Moreover, the detection operators

, defined in Equation (

15), form a complete set in the N-dimensional Hilbert space,

In general, the success probability

for ME of

N quantum states

, each prepared with

a priori probability

, is given by [

3,

4]

For the case of

N pure nonorthogonal equidistant states,

, prepared with equal

a priori probabilities,

, the optimum success probability simplifies to

as a consequence of the symmetry of the state set and the structure of the detectors operators

, defined in Equation (

15). The corresponding minimum error probability is then

Therefore, the optimum success probability in ME of

N pure nonorthogonal equidistant states with equal

a priori probabilities, is given by

where the coefficients

correspond to those of the fiducial state

. The success probability given by Equation (

22) is similar to that obtained for ME of

N symmetric states prepare with equal

a priori probability [

17,

39,

40]. We notice here that using detectors operator different from

results in a higher probability of error. The worst case scenario occurs when the state is guessed randomly, which is equivalent to using the detectors operators of the form

, that is, performing a direct measurement of the equidistant states

in the computational basis

. In such case, the success probability is

, independently of the form of the states. A similar result is obtained even when using the optimum detector operators

, if the inner product between the states satisfies

. This corresponds to the situation in which all the states are identical, i.e.,

for

. Since the states are completely indistinguishable in this scenario, the optimal success probability again reduces to

.

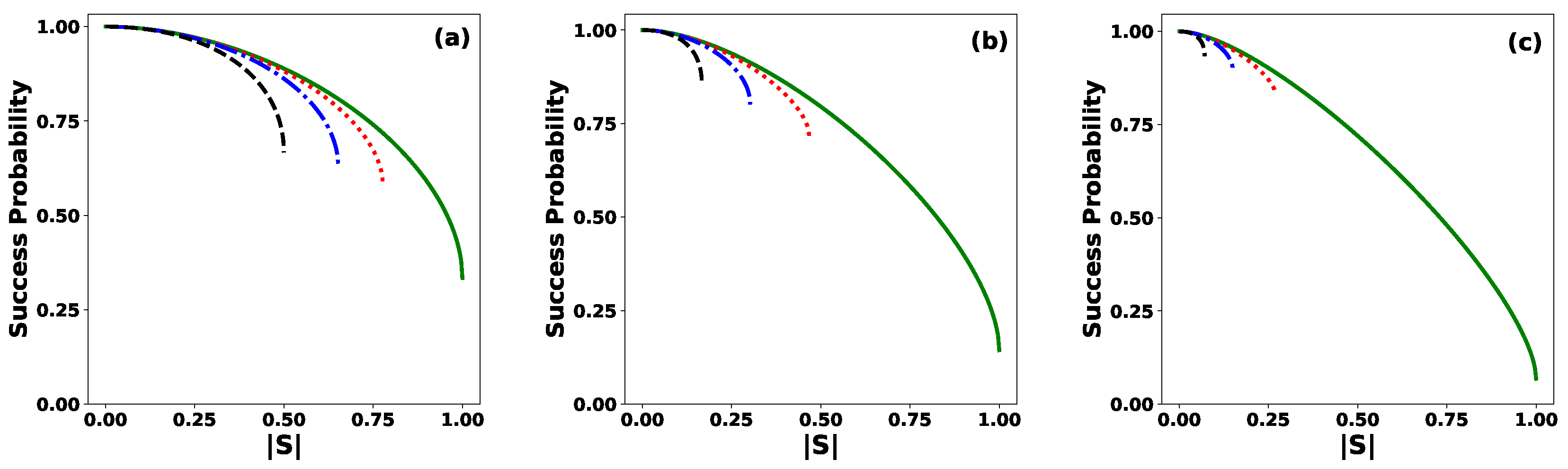

Figure 3 shows the optimal success probability

, given by Equation (

22), in the discrimination by ME of

N equidistant states as a function of

, for several values of

, and for: (a)

, (b)

and (c)

. When the states are orthogonal,

, the maximum success probability

is achieved. This shows the well-known result that orthogonal states can be perfectly discriminated deterministically and without error. In all other cases, the discrimination involves some error, but this strategy minimizes the error probability. For any fixed value of

N and

, the success probability

decreases as

increases, reaching its minimum value when the states become linearly dependent, that is, when

. On the other hand, if the number of states

N and the modulus

are fixed (within the allowed range), the success probability

decreases as the phase

increases. This implies that it is more likely to correctly discriminate a set of linearly independent states than a set of linearly dependent ones. Moreover, as the number of states

N increases, the only relevant case becomes

. This is because, for

, the allowed values of

become increasingly close to zero, implying that the success probability under the ME strategy tends to one.

The ME strategy can be interpreted as a quantum communication scenario. On one side, Alice prepares and sends a quantum state

, chosen from the set of equidistant states. On the other side, Bob located at a distant location, receives the state and applies quantum state discrimination to retrieve the classical information encoded in the state. To implement ME, Bob must first apply a unitary transformation to the received states that he received

. For the set of equidistant states considered here, the appropriate transformation is the discrete inverse Fourier transform

. This operation transforms the equidistant states according to:

where

and thus, the evolution of the equidistant states under the

transformation is given by

We assume that the subtraction

in Equations (

23) and (

24) is performed modulo N. After applying the discrete inverse Fourier transform

, Bob completes the ME by performing a projective measurement on the transformed states

in the computational basis

. For instance, if Alice prepares and sends the state

, Bob applies the transformation and obtains

. He then performs a projective measurement in the basis

, which yields one of

N possible outcomes. If the outcome is

, the state

has been correctly identified, and the discrimination is successful. The corresponding success probability is given by

. Conversely, if the outcome is

with

an error occurs in the discrimination of

. However, The ME strategy guarantees that this error occurs with the lowest possible probability among all quantum discrimination strategies.

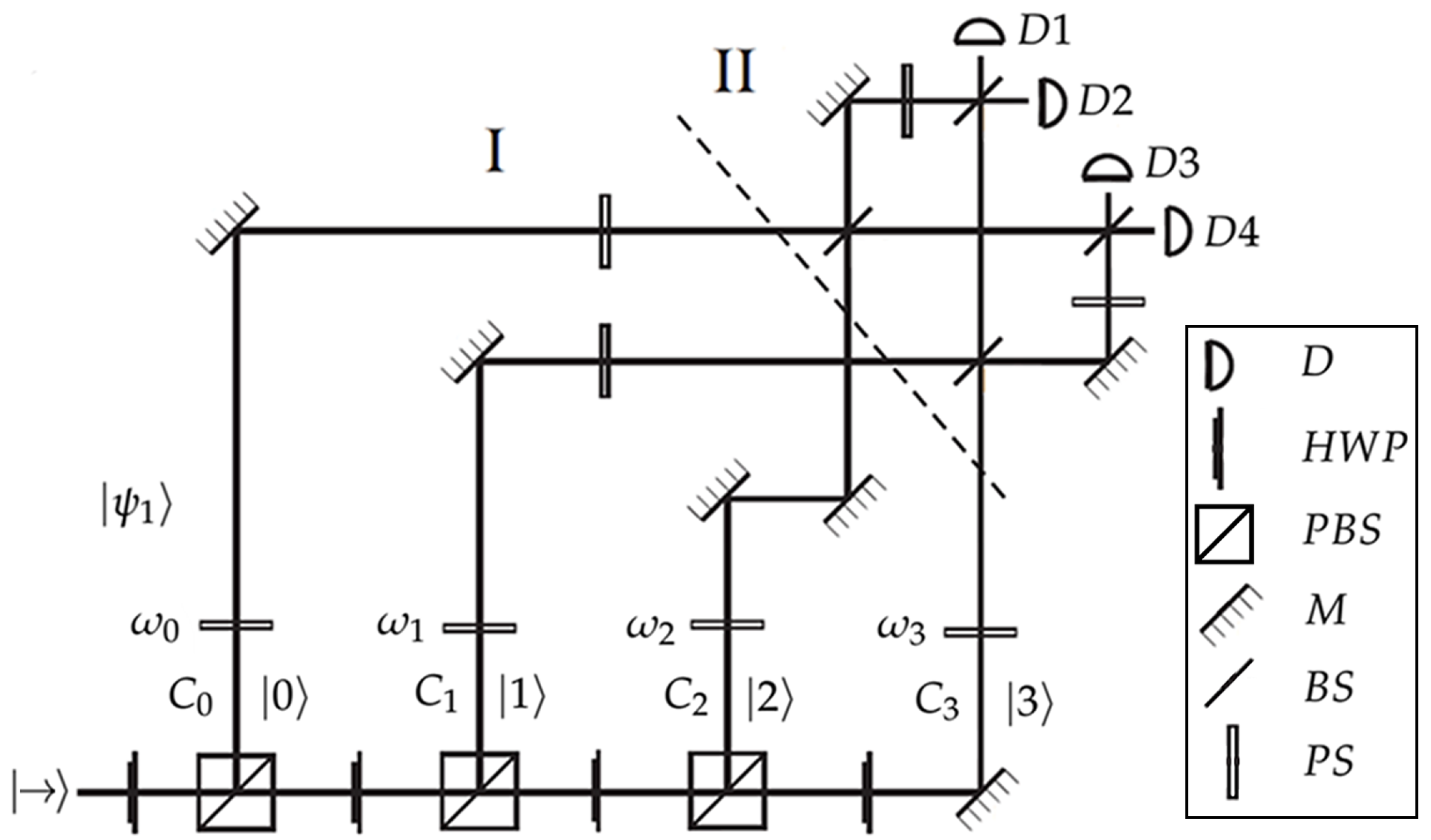

A proposal for the experimental implementation of ME of

pure equidistant states is shown in

Figure 4. This scheme is similar to previously reported setups for the discrimination of symmetric states [

40,

41]. The first stage corresponds to the state preparation. Alice prepares and sends one of the equidistant states, say

. For this purpose, a single photon with horizontal polarization

enters the experimental setup. Alice can prepare any of the equidistant states by adjusting the phases

in each paths of propagation of the photon

, and by setting the appropriate rotation angles in the polarizing beam splitters to generate the desired amplitudes

for each path. The prepared state then propagates through the channel. Upon receiving the state

, Bob implements the inverse of the discrete Fourier transform

in a four-dimensional Hilbert space. Finally, he performs a projective measurement in the computational basis

. The initial single photon, after propagating through the discrimination setup, will be detected by one of the four detectors shown in

Figure 4.

4. Quantum Coherence

As previously mentioned, in a quantum communication scenario, Alice prepares and sends to Bob one of the equidistant states

, each with equal

a priori probability

. Bob aims to extract the encoded information by performing a quantum measurement on the received state. Therefore, the ensemble of possible states received by Bob is described by the density matrix

, which is given by

Due to the symmetry of the equidistant states, this density matrix takes the simplified diagonal form

which is a diagonal state in the computational basis

. Quantum coherence is associated with the ability of a quantum system to exhibit interference effects [

42]. Such interference arises when the system’s density matrix possesses non zero off-diagonal elements in a given basis. Accordingly, the state

, in Equation (

27), exhibits no quantum coherence with respect to the basis

, as it is diagonal in that basis. A canonical example of a maximally coherent state in a

d-dimensional Hilbert space is given by [

43,

44]

which contains

bits of coherence, also referred to as cobit [

43], relative to the computational basis

. Quantum coherence has been formally established as a fundamental resource for the implementation of quantum protocols, and it is consumed during the execution of such protocols [

43,

45,

46]. Several measures have been proposed to quantify quantum coherence, including the coherence cost, the relative entropy of coherence, and the

norm of coherence, among others [

43]. To quantify the quantum coherence of the state

with respect to a given projective measurement

, we employ the relative entropy of coherence [

43,

44], defined as

where,

is the Shannon entropy associated with the measurement outcome probabilities

, given by

and where

with

being the projective measurement performed by Bob, and

is the von Neumann entropy, which is

where,

are the eingenvalues of the density matrix

. For the set of equidistant states, the von Neumann entropy of

is given by

which depends solely on the coefficients

and is independent of the quantum measurement

applied by Bob. As shown in Equation (

29), the quantum coherence depends both on the state

and on the quantum measurement

, which, in this case, corresponds to ME. Then, the probability distribution

is given by

Therefore, the relative entropy of coherence when Bob implements ME is given by

which corresponds to the maximum coherence attainable from any projective measurement

on the state

. This result holds because the Shannon entropy

reaches its maximum value,

, when the measurement is performed using the projectors

defined in Equation (

15). Thus, among all possible projective measurement, the ME strategy maximizes the quantum coherence of

.

Quantum coherence plays a fundamental operational role in the context of cryptographic randomness gain [

47,

48]. In particular, when an eavesdropper (Eve) is present in the communication channel, higher values of quantum coherence make it more difficult for her to extract information. For instance, if the set of quantum states is orthogonal,

, the quantum coherence vanishes, and Eve can obtain complete information by performing a projective measurement without disturbing Bob’s state

. At the opposite extreme, when all the states are identical, i.e.,

, for all

j, the state is pure,

, and the quantum coherence reaches its maximum value of

, where

N the number of states in the ensamble. In this scenario, Eve cannot distinguish between the states and is left with no better strategy than randomly guessing the state sent by Alice.

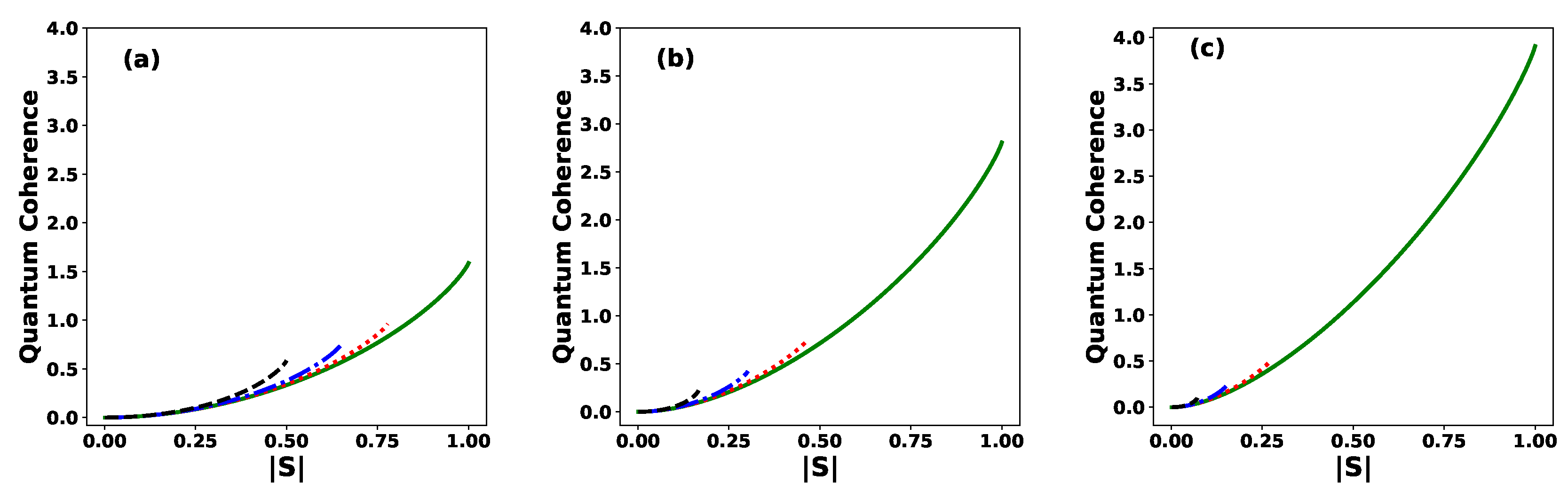

Figure 5 shows quantum coherence of

when is implemented ME of

N pure equidistant states, as a function of

for various values of the phase

for: (a)

, (b)

, (c)

. The behavior of quantum coherence

differs notably from that of the success probability

. For any given values of

and

N, coherence reaches its minimum (zero) when the states are orthogonal

, and its maximum (

) when the states are linearly dependent with

. For a fixed number of states

N, within the allowed range of

, increasing the value of the phase

from

to

results in an increase in quantum coherence. This indicates that, for a given

N, a more linearly dependent set of states exhibit greater coherence than a linearly independent one. Furthermore, for any fixed

, increasing the number of states

N leads to a rapid decrease in coherence, which tends to zero as

N becomes sufficiently large.

5. Channel Without Entanglement

In the ME scheme, Alice prepares a single copy of a quantum system in the state

and sends it to Bob with an

a priori probability

. We assume that, initially, Alice and Bob, share a separable quantum state

of the form

where

forms an orthonormal base for Alice’s N-dimensional quantum system, and

are the pure equidistant states that Bob receives. Thereby, Alice and Bob share quantum and classical correlations encoded in the joint state

defined in Equation (

36). The initial state

of Alice’s quantum system, that is, prior to the application of any transformation or measurement, is obtained by

, where

In a similar form, the initial state of Bob’s quantum system can be obtained by tracing out Alice’s subsystem from the global state, i.e.,

, where

Once Bob receives a single copy of the quantum system prepared in one of the equidistant state

, he implements the ME strategy. For that purpose, Bob first applies the unitary transformation

to his quantum system, thereby transforming the global state

into a new state

, given by

where

. The unitary operation

, defined in Equation (

17) and applied by Bob, is a reversible process [

49]. Therefore, it does not change the quantum correlations between Alice and Bob initially encoded in the global state

. After this transformation, Bob performs a measurement on his subsystem, which yields

N possible outcomes and, correspondingly,

N conditional post-measurement states

for Alice’s subsystem. Since Bob’s measurement projects the state

onto one the orthonormal basis states

, the resulting conditional state for Alice is given by

where

with

is the success probability in ME for each

. The final average joint state between Alice and Bob, denoted by

, after Bob performs his measurement in the basis

, takes the following form:

Then, the final reduced states for Alice’s and Bob’s quantum subsystems are given by

Thereby, the final reduced state for Alice’s subsystem remains unchanged, i.e.,

. It is convenient, using Equation (

42) as follows:

From Equation (

45), we can notice that, if Bob successfully discriminates the state

, which is one of the states sent by Alice, the final shared state between Alice and Bob is

, and this occurs with probability

. Otherwise, if the discrimination attempt fails, the resulting state is

with

, indicating an error in identifying the state

. Such an error occurs with the minimum error probability, given by

.

6. Classical Correlations and Quantum Discord

In a bipartite quantum state

, the total amount of correlation, in the many copy scenario [

50], is quantified by the quantum mutual information. This is defined as [

50,

51]

where

denotes the von Neumann entropy of the state

. In our ME scheme, we assume that Alice emits many independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) copies of the bipartite state, i.e.,

for large

n[

52]. The entropy of the initial joint state

, given by Equation (

36), can be written as

since each

is a pure state and therefore has zero entropy. Thus, the total correlation between Alice and Bob in the bipartite state

, as defined in Equation (

39), is given by the mutual information

. Moreover, the quantum mutual information,

, can be written as [

51,

53]

where,

denotes the classical correlations and

the quantum discord. Both quantities depend on the measurement implemented by Bob, represented by the set of projectors

. However, their sum, the total mutual information, is independent of the choice of measurement [

54], i.e., they are complementary to each other [

14]. The classical correlations

between Alice and Bob are defined as [

53,

55]

which can be interpreted as the information about Alice’s system that Bob gains through the measurement

. In this work, we focus on quantifying the classical correlations between Alice and Bob,

, when Bob implements the ME on the set of pure equidistant states. On the other hand, the problem of maximizing the classical correlation

over all possible measurements performed by Bob is a challenging task and is not addressed here. The maximal classical correlation

is known as the accessible information [

9,

10]. It corresponds to the classical mutual information maximized over all possible measurement strategies [

12]. This optimization is generally difficult to perform and lies beyond the cope of the present work. Nevertheless, it is known that for

, the quantum measurement that achieves the accessible information coincide with the one that minimizes the error probability in state discrimination [

4,

11]. Furthermore, for any

N, the accessible information for a set of

N pure, nonorthogonal equidistant states must be at least as large as the classical information obtained through the ME measurement. The classical correlations

in ME, given the symmetry, can be expressed as

where

, and the entropy of the conditional state

is given by

with,

defined in Equation (

41). On the other hand, quantum discord

, which quantifies the quantum correlations consumed or lost during the measurement process, is given by

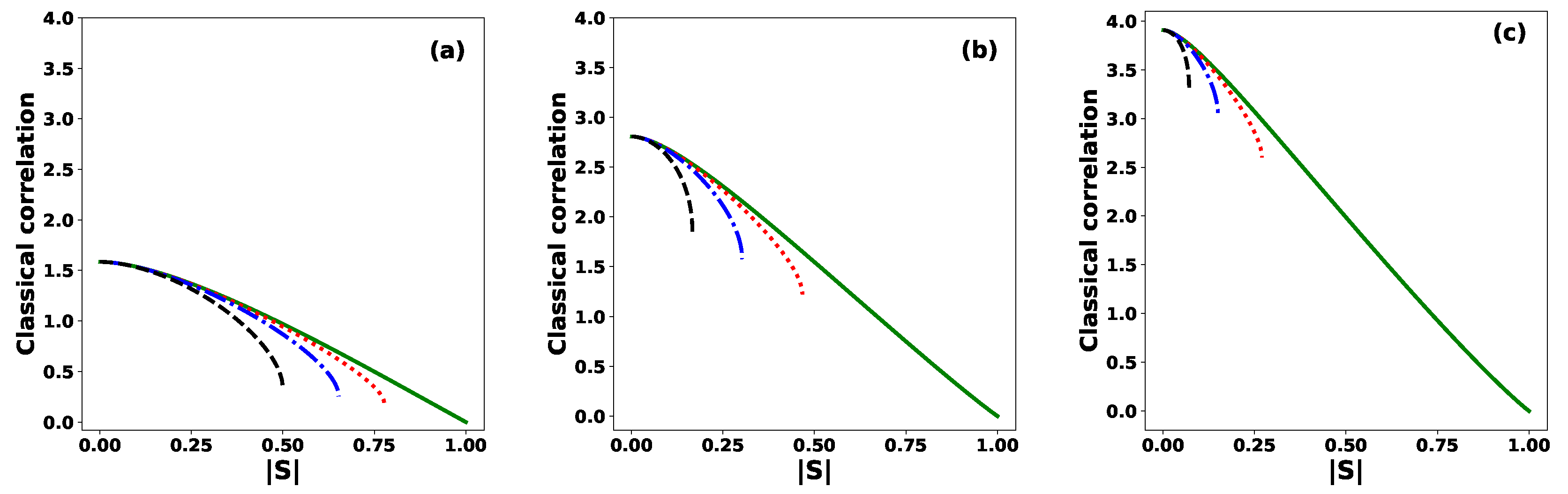

Figure 6 shows the classical correlation between Alice and Bob as a function of the modulus

for: (a)

, (b)

and (c)

, and several values of the phase

. The classical correlation reaches its maximum value when the equidistant states are orthogonal, i.e.,

. In this case, the maximum value is

, indicating that Alice and Bob share total classical correlation. The corresponding final joint state is

As

increases, the classical correlation

decreases, reaching its minimum value of zero when

and

. This behavior arises because the initial joint state between Alice and Bob becomes a product state with no correlation, given by

For a fixed value of N and an allow value of , increasing the phase from 0 to leads to a decrease in the classical correlation. Moreover, we observe that larger values of N result in higher classical correlation between Alice and Bob. This highlights the importance of using a greater number of states in order to enhance the classical correlation, which is a desirable feature for the performance of the protocol.

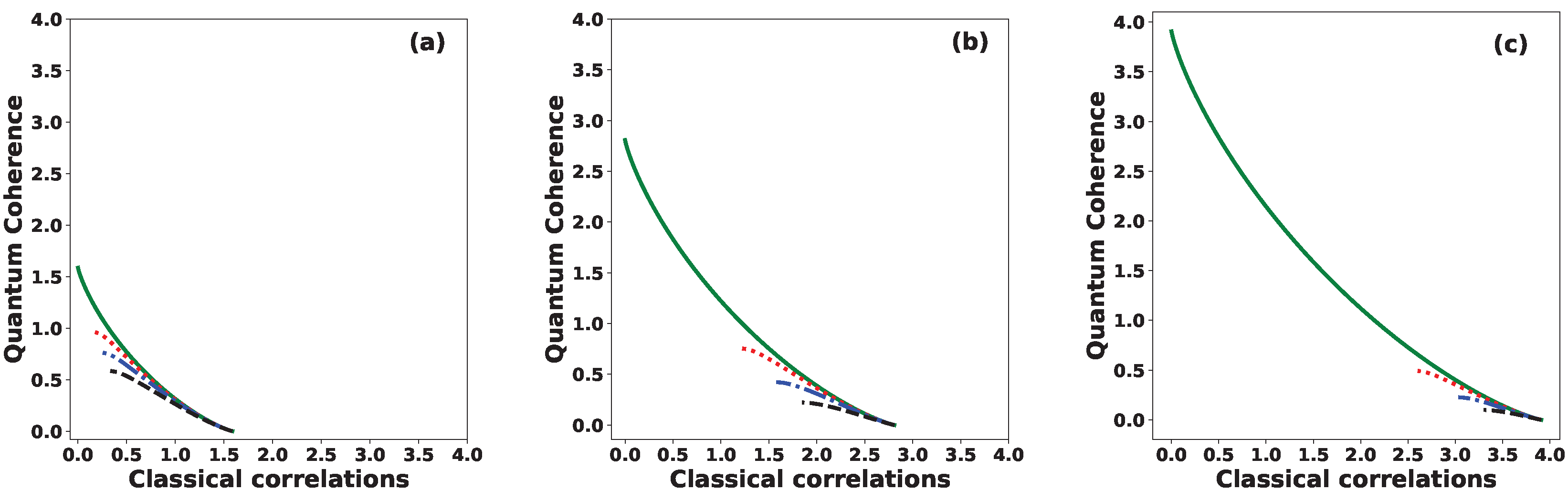

Figure 7 shows quantum coherence versus classical correlation between Alice and Bob for various values of the phase:

(solid green line),

(dotted red line),

(dashed-dotted blue line), and

(dashed black line), for: (a)

, (b)

and (c)

. We observe that both quantities, quantum coherence and classical correlations, lie within the same range, namely

. It is important to highlight here the operational interpretation of the quantum coherence as a quantifier of cryptographic randomness gain [

47,

48]. Therefore, for a secure and efficient protocol, we expect that Alice and Bob share a significant amount of classical correlation while maintaining sufficiently high quantum coherence. For example, when the set of states is orthogonal

the initial joint state takes the form

, which exhibits maximal classical correlation of

bit but zero quantum coherence. In contrast, when the set of states is identical

, the initial joint state becomes

, a product state with no classical correlation but exhibiting maximal quantum coherence, equivalent to

bits of randomness. Hence, Alice and Bob should choose an initial joint state

that simultaneously exhibits high classical correlation and high quantum coherence. This trade-off can be optimally achieved when the phase of the inner product is

and the number of states

N is large.

Figure 1.

Ordering property of the coefficients

from Equation (

5) as a function of

, shown for: (a)

, (b)

, and (c)

, with

.

Figure 1.

Ordering property of the coefficients

from Equation (

5) as a function of

, shown for: (a)

, (b)

, and (c)

, with

.

Figure 2.

Polar graph of the inner product S. The blue line indicates the boundary , where the set of equidistant states becomes linearly dependent. Each point inside the bounded region corresponds to a specific value of S and represents a set of N linearly independent equidistant states: (a) N=3, (b) N=7 and (c) N=15.

Figure 2.

Polar graph of the inner product S. The blue line indicates the boundary , where the set of equidistant states becomes linearly dependent. Each point inside the bounded region corresponds to a specific value of S and represents a set of N linearly independent equidistant states: (a) N=3, (b) N=7 and (c) N=15.

Figure 3.

Success probability for ME of equidistant states as a function of the modulus of the inner product, for the values: (solid green line), (dotted red line), (dashed-dotted blue line), and (dashed black line), for: (a) , (b) , and (c) .

Figure 3.

Success probability for ME of equidistant states as a function of the modulus of the inner product, for the values: (solid green line), (dotted red line), (dashed-dotted blue line), and (dashed black line), for: (a) , (b) , and (c) .

Figure 4.

Experimental proposal for ME of four equidistant states: (I) State preparation: Alice send one of the equidistant states, e.g., , (II) Detection stage: Bob applies the inverse discrete Fourier transform in a four-dimensional Hilbert space and performs a projective measurement in the computational basis . HWP, half-wave plate; PBS, polarizing beam splitter; PS, phase shifter; BS, beam splitter; M, mirror; D, detector.

Figure 4.

Experimental proposal for ME of four equidistant states: (I) State preparation: Alice send one of the equidistant states, e.g., , (II) Detection stage: Bob applies the inverse discrete Fourier transform in a four-dimensional Hilbert space and performs a projective measurement in the computational basis . HWP, half-wave plate; PBS, polarizing beam splitter; PS, phase shifter; BS, beam splitter; M, mirror; D, detector.

Figure 5.

Quantum coherence of the initial state

, given in Equation (

27), as a function of the modulus

of the inner product, for different values of the phase:

(solid green line),

(dotted red line),

(dashed-dotted blue line), and

(dashed black line) for: (a)

, (b)

and (c)

.

Figure 5.

Quantum coherence of the initial state

, given in Equation (

27), as a function of the modulus

of the inner product, for different values of the phase:

(solid green line),

(dotted red line),

(dashed-dotted blue line), and

(dashed black line) for: (a)

, (b)

and (c)

.

Figure 6.

Classical correlation between Alice and Bob as a function of the modulus of the inner product, for different values of the phase: (solid green line), (dotted red line), (dashed-dotted blue line), and (dashed black line), for: (a) , (b) and (c) .

Figure 6.

Classical correlation between Alice and Bob as a function of the modulus of the inner product, for different values of the phase: (solid green line), (dotted red line), (dashed-dotted blue line), and (dashed black line), for: (a) , (b) and (c) .

Figure 7.

Quantum coherence versus classical correlation between Alice and Bob for different values of the phase: (solid green line), (dotted red line), (dashed-dotted blue line), and (dashed black line), for: (a) , (b) and (c) .

Figure 7.

Quantum coherence versus classical correlation between Alice and Bob for different values of the phase: (solid green line), (dotted red line), (dashed-dotted blue line), and (dashed black line), for: (a) , (b) and (c) .