Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. (A)dS-Schwarzschild Black Holes Maximize Entropy

- 1.

- Bulk metric fixed:

- 2.

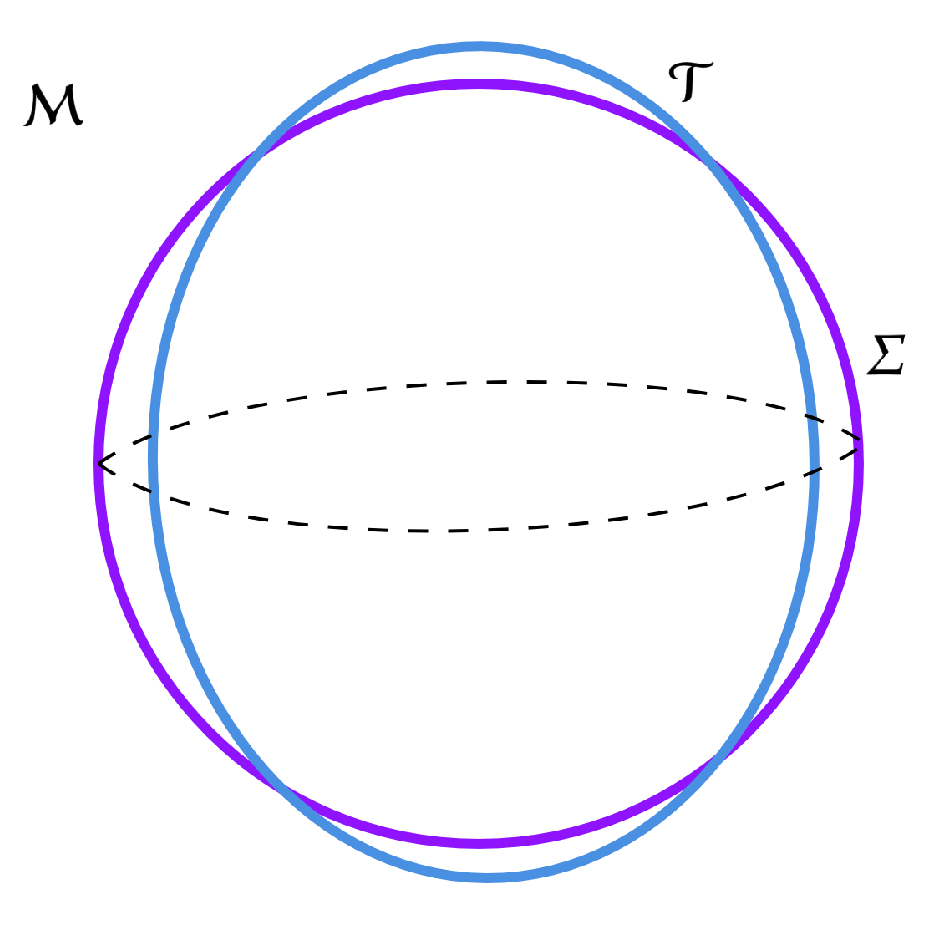

- Hypersurface varied: so that and hence

2.1. Sherif-Dunsby Rigidity and Maximal Entropy

- Identification of the conformal factor: One shows that the infinitesimal conformal factorcoincides with the sheet-expansion scalar in the split.

-

Gravitational focusing: Under the usual energy conditions (e.g. ) the Raychaudhuri-type equation for impliesHence, the conformal factor is strictly negative as we move along .

- Sherif–Dunsby rigidity: By Theorem VII.4 of Sherif and Dunsby [17] (see Appendix (A) for details of theorem and its role in our proof), any proper (non-constant), scalar-curvature-preserving conformal transformationon a compact 3-manifold (non-Einstein) forces to be isometric to the round (up to a constant scale).

Bolt-to-Horizon Identification.

2.2. Effective Functional and Its Variation

3. Conclusion and Discussion

- Charged and Rotating Solutions: Although we have shown that electric charge reduces the saddle action via the additional Maxwell term but keeps the entropy equal to the uncharged case, it also saturates RII. However, a full treatment of RII for charged (Reissner–Nordström) and rotating (Kerr–AdS) black holes—including off-shell stability analysis—would elucidate possible extensions or violations in these more general settings.

- Quantum Corrections: Incorporating higher-curvature corrections or quantum effects (e.g., via one-loop determinants or entanglement entropy corrections) may modify the geometric rigidity or the second variation functional, potentially leading to refined ‘‘quantum RII’’ bounds.

- Holographic Perspectives: Given the AdS/CFT correspondence, it would be interesting to interpret our RII proof in the dual field theory, perhaps relating maximal horizon entropy at fixed volume to extremal entanglement or energy constraints in the boundary CFT.

- Beyond Asymptotic (A)dS: Extending the analysis to asymptotically flat or more exotic asymptotics (e.g., Lifshitz, hyperscaling violation) might reveal whether the reverse isoperimetric phenomenon is unique to constant- backgrounds or has broader applicability.

- Violation in the case of superentropic black holes: It is known that superentropic black holes violate RII. As part of the proof we presented, this can be traced to their non-compact hypersurface while the proof requires a compact hypersurface. Nevertheless, a general proof explicitly for non-compact hypersurfaces is an interesting future work.

Appendix A. Conformal Rigidity and Sphericity of Compact Hypersurfaces

Appendix A.1. Statement of the Theorem

Appendix A.2. Role in the Reverse Isoperimetric Proof

- is compact,

- admits a nontrivial conformal deformation preserving scalar curvature. This is the Yamabe problem [23] and can always be ensured for a choice of conformal factor within a conformal class. Physically, this is a natural condition whenever we demand that the hypersurface be an extremum of some conformally sensitive functional (such as area at fixed volume) under all local Weyl rescalings,

- scalar curvature is positive. This is always the case for round . Therefore, any deformation of by a small conformal factor will preserve the positivity. This means that curvature scalar is also positive on . On the Lorentzian side, it a known result [24] that horizons are positive Yamabe type (admit positive scalar curvature),

Appendix B. Saddle Action in 1+1+2 Decomposition of Spacetime

Appendix B.1. Cancellation of the Bulk-Boundary Term via GHY Boundary Term

Appendix C. Spectrum of Metric Perturbations on the Round 3-Sphere

Appendix C.1. Transverse–Traceless Gauge and Lichnerowicz Operator

Appendix C.2. Tensor Harmonic Spectrum on S 3

Appendix C.3. Exclusion of ℓ=0,1 Modes

- (monopole): A constant rescalingchanges the volume rather than shape; in TT gauge forbids such a trace mode.

- (dipole): These correspond to infinitesimal diffeomorphisms (Killing vectors) on ,which can be entirely removed by a coordinate redefinition. In TT gauge one requires , and one finds no non-gauge TT tensors.

References

- Kastor, D.; Ray, S.; Traschen, J. Enthalpy and the Mechanics of AdS Black Holes. Class. Quant. Grav. 2009, 26, 195011, [arXiv:hep-th/0904.2765]. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, B.P. The cosmological constant and the black hole equation of state. Class. Quant. Grav. 2011, 28, 125020, [arXiv:gr-qc/1008.5023]. [CrossRef]

- Cvetic, M.; Gibbons, G.W.; Kubiznak, D.; Pope, C.N. Black Hole Enthalpy and an Entropy Inequality for the Thermodynamic Volume. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 024037, [arXiv:hep-th/1012.2888]. [CrossRef]

- Chamblin, A.; Emparan, R.; Johnson, C.V.; Myers, R.C. Charged AdS black holes and catastrophic holography. Phys. Rev. D 1999, 60, 064018, [hep-th/9902170]. [CrossRef]

- Kubiznak, D.; Mann, R.B. P-V criticality of charged AdS black holes. JHEP 2012, 07, 033, [arXiv:hep-th/1205.0559]. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.V. Holographic Heat Engines. Class. Quant. Grav. 2014, 31, 205002, [arXiv:hep-th/1404.5982]. [CrossRef]

- Frassino, A.M.; Pedraza, J.F.; Svesko, A.; Visser, M.R. Higher-Dimensional Origin of Extended Black Hole Thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 161501, [arXiv:hep-th/2212.14055]. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.X. Extended Black Hole Thermodynamics from Extended Iyer-Wald Formalism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 021401, [arXiv:gr-qc/2308.12630]. [CrossRef]

- Osserman, R. Isoperimetric and related inequalities. In Proceedings of the Proc. Symp. Pure Math, 1975, Vol. 27, pp. 207–215.

- Osserman, R. The isoperimetric inequality. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 1978, 84, 1182–1238.

- Martinez, C.; Teitelboim, C.; Zanelli, J. Charged rotating black hole in three space-time dimensions. Phys. Rev. D 2000, 61, 104013, [hep-th/9912259]. [CrossRef]

- Hennigar, R.A.; Mann, R.B.; Tjoa, E. Super-Entropic Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 031101, [arXiv:hep-th/1411.4309]. [CrossRef]

- Hennigar, R.A.; Kubizňák, D.; Mann, R.B.; Musoke, N. Ultraspinning limits and super-entropic black holes. JHEP 2015, 06, 096, [arXiv:hep-th/1504.07529]. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.V. Instability of super-entropic black holes in extended thermodynamics. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 35, 2050098, [arXiv:hep-th/1906.00993]. [CrossRef]

- Frassino, A.M.; Hennigar, R.A.; Pedraza, J.F.; Svesko, A. Quantum Inequalities for Quantum Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 181501, [arXiv:hep-th/2406.17860]. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, C. A Covariant approach for perturbations of rotationally symmetric spacetimes. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 104034, [arXiv:gr-qc/0708.1398]. [CrossRef]

- Sherif, A.M.; Dunsby, P.K.S. Conformal geometry on a class of embedded hypersurfaces in spacetimes. Class. Quant. Grav. 2022, 39, 045004, [arXiv:math.DG/2112.08753]. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T.; Visser, M.R. Partition Function for a Volume of Space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 221501, [arXiv:hep-th/2212.10607]. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.L. A relation between volume, mean curvature and diameter. In Euclidean Quantum Gravity; World Scientific, 1964; pp. 161–161.

- O’neill, B. Semi-Riemannian geometry with applications to relativity; Vol. 103, Academic press, 1983.

- Dolan, B.P.; Kastor, D.; Kubiznak, D.; Mann, R.B.; Traschen, J. Thermodynamic Volumes and Isoperimetric Inequalities for de Sitter Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 104017, [arXiv:hep-th/1301.5926]. [CrossRef]

- Obata, M. Certain conditions for a Riemannian manifold to be isometric with a sphere. Journal of the Mathematical Society of Japan 1962, 14, 333–340. [CrossRef]

- Yamabe, H. On a deformation of Riemannian structures on compact manifolds. Osaka Math. J. 1960, 12, 21–37.

- Galloway, G.J.; Schoen, R. A generalization of Hawking’s black hole topology theorem to higher dimensions. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2006, 266, 571–576, [arXiv:gr-qc/gr-qc/0509107v2]. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The definition of thermodynamic volume requires a cosmological constant or a gauge coupling. (A)dS black holes are naturally equipped with this. |

| 2 | Since we now study the natural state of deformed 3-sphere under gravity. |

| 3 | This is because gravity drives a deformed 3-sphere back to round 3-sphere establishing it as a stable state. Since stability in the context of thermodynamics is tied with maximal entropy, the conclusion naturally follows. |

| 4 | The explicit equations for area and volume variations can be found in [20]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).