Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Limitations of Fear-Based Climate Communication

Acute vs Chronic Fear Responses

Cultural and Socio-Economic Variability in Fear-Processing

Trauma-Informed Critique of Fear-Based Campaigns

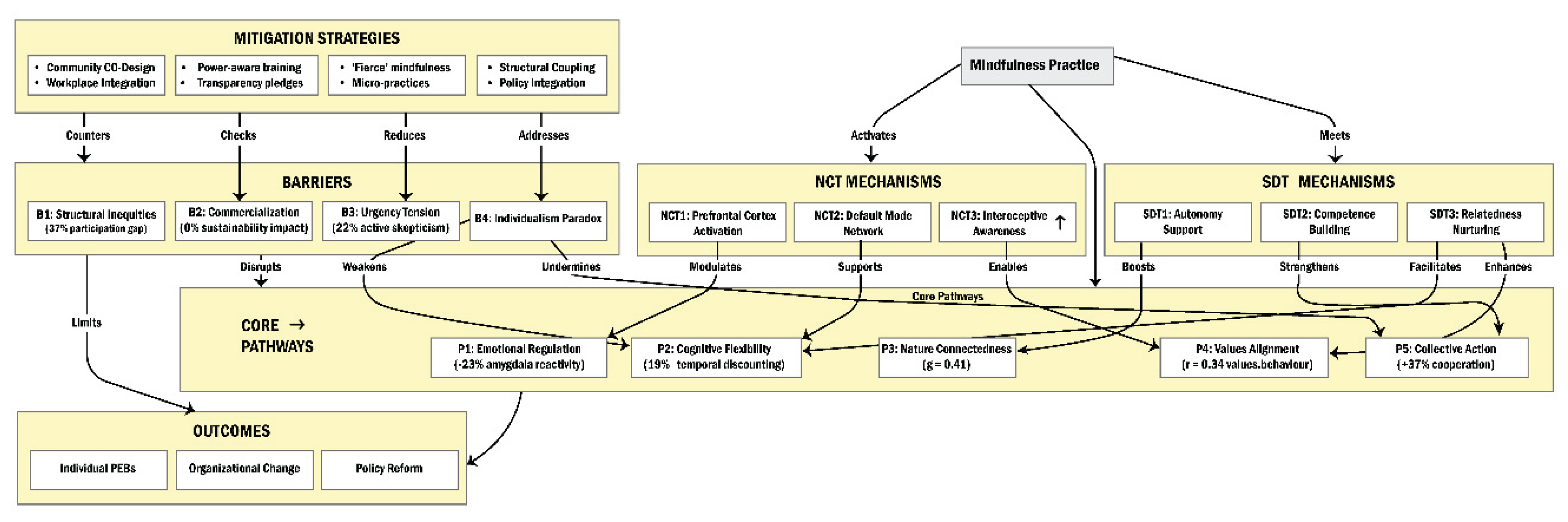

Mindfulness for Pro-Environmental Action: A Conceptual Framework

Neurocognitive (NCT) Mechanisms: Rewiring the Brain for Resilience

Enhanced Interoceptive Awareness: The Insular Cortex as a Hub

Increased Prefrontal Cortex Activation: Top-Down Regulation and Cognitive Control

Suppression of the Default Mode Network: Reducing Self-Referential Narrative

Integration and Neuroplastic Rewiring

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Social Diffusion Theory and Propagation of Mindfulness Practices

Pro-Environmental Behavior Pathways

Pathway 1: Emotional Regulation and Resilience

Pathway 2: Cognitive Flexibility and Ethical Decision-Making

- Reduced Temporal Discounting: Mindfulness practitioners exhibit significantly lower temporal discounting rates (β = -0.22, p < .05; Tang et al., 2017), meaning they place greater relative value on future rewards and consequences compared to immediate gratification. This shift is linked to increased activation in brain regions associated with future-oriented thinking (e.g., prefrontal cortex) and reduced activity in regions linked to impulsive reward processing (e.g., ventral striatum) during intertemporal choice tasks (Wittmann et al., 2016). This makes practitioners more likely to prioritize long-term environmental benefits over short-term conveniences or costs.

- Enhanced Recognition of Ecological Interdependencies: Mindfulness cultivates a heightened awareness of interconnectedness, leading to significantly improved recognition of complex ecological relationships (η² = 0.11; Amel et al., 2017). This involves moving beyond simplistic, linear thinking to appreciate systemic feedback loops, unintended consequences, and the embeddedness of human actions within natural systems (Zylowska et al., 2008; Jacob et al., 2009). This systemic understanding fosters a stronger sense of responsibility towards the broader web of life.

- Decreased Vulnerability to Greenwashing: Practitioners demonstrate greater resistance to deceptive environmental marketing (d = 0.61; Lefebvre et al., 2020). Mindfulness enhances critical evaluation skills and reduces susceptibility to superficial cues (e.g., nature imagery, vague claims like "eco-friendly") by promoting present-moment attention to actual substance and reducing reliance on cognitive heuristics (Parguel et al., 2021). However, this effect is context-dependent, with weaker impacts observed specifically for environmental greenwashing claims compared to corporate social responsibility greenwashing, potentially due to the higher complexity and lower consumer familiarity with detailed environmental credentials (Parguel et al., 2021; Seele & Schultz, 2022).

Pathway 3: Connectedness to Nature

Pathway 4: Intrinsic Motivation and Values Alignment

Pathway 5: Self to Social Transformation: Collective Action

Barriers to Scaling and Mitigation Strategies

Structural Inequities

Co-Optation and Commercialization Risks

Urgency-Compatibility Tension

The Individualism Paradox

Discussion: Scaling and Systemic Integration of Mindfulness for Sustainability

Policy Integration: Mainstreaming Mindfulness in Governance

Organizational-Level or Workplace Systems: Structural Embedding

A Social Diffusion Framework for Scaling Mindfulness in Sustainability Policy and Organizations

Institutionalization Through Policy and Structural Change

Organizational Adoption Through Networked Leadership

Cultural Adaptation and Community-Based Diffusion

Economic and Technological Acceleration

Implementation Phasing and Networked Governance

Implications for Future Research

Mindfulness-Mechanisms-Pathways

- NCT: Greater prefrontal cortex activation during mindfulness practice will predict stronger emotional regulation effects (reduced amygdala reactivity). (A→NCT1→P1 link)

- SDT: Mindfulness interventions that enhance autonomy support (SDT1) will show greater values behavior alignment (P4) than those that don’t. (A→ SDT1→ P4 link)

Pathway – Outcomes

- 3.

- Individuals showing increased nature connectedness (P3) post-mindfulness engage in more individual PEBs (C1), especially in consumption behaviors (P3→ O1 link).

- 4.

- Groups with improved collective action (P5) from mindfulness will demonstrate more organizational sustainability initiatives (O2). (P5→ C2 link)

Barrier Interactions

- 5.

- Structural inequities (B1) will moderate P5→ C2 effects, with weaker outcomes in high inequity contexts (B1 disrupts P5→ C2).

- 6.

- The individualism paradox (B4) will negatively correlate with cognitive flexibility gains (P2) from mindfulness (B4 weakens P2).

Strategy Efficacy

- 7.

- “Fierce mindfulness” training (S3) will reduce urgency tension barriers (B3) more than standard mindfulness (S3 counters B3).

- 8.

- Policy-integrated mindfulness programs (S4) will mitigate individualism paradox effects (B4) on collective action (P5) (S4→ B4→ P5).

Cross-Mechanism Effects

- 9.

-

Participants with both high interoceptive awareness (NCT3) and autonomy support (SDT1) will show the strongest values alignment (P4). (NCT3+SDT1→ P4 interaction).

- 10.

- Default mode network suppression (NCT2) will mediate the relationship between mindfulness practice and reduced temporal discounting (P2). (A→ N2→ P2 mediation).

Real-World Impact

- 11.

- Organizations combining workplace integration (S1) and competence building (SDT2) will show greater sustainability policy adoption (O3). (S1+SDT2→ O3)

- 12.

- Community co-designed programs (S1) will yield stronger nature connectedness (P3) in low-income groups by reducing structural inequity barriers (B1). (S1 mitigates B1→P3).

Research Design Framework

Method

Sampling Plan

Experimental Conditions

Measures and Type of Data

Data Analysis

Controls & Validity

Ethical Considerations

Conclusion

References

- Amel, E., Manning, C, Scott, B, & Koger, S. (2017). Beyond the roots of human inaction: Fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science, 356(6335), 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankrah, D., Bristow, J., Hires, D., & Henriksson, J.A. (2023). “Inner Development Goals: from inner growth to outer change”. Field Actions Science Reports, 25 2. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/7326.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1997). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reis, (77/78), 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moheseni-Cheraghlou, A., & Evans, H. (2024). Climate change prioritization in low-income and developing countries. Atlantic Council. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/climate-change-prioritization-in-low-income-and-developing-countries/.

- Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. (2022). The social psychology of work engagement: state of the field. Career Development International, 27(1), 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory, (Vol. 1, pp. 141-154). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Barbaro, N., & Pickett, S. M. (2016). Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: Implications for pro-environmental behavior. Personality and Individual Differences 93, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B., Wicks, J. C., Scharmer, O., & Pavlovich, K. (2015). Exploring transcendental leadership: a conversation. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 12(4), 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Jason, G., de Mazancourt, C., Parmesan, C., Singer, M. C., & Loreau, M. (2022). Human-nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: A global meta-analysis. Conservation letters, 15(1), e12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G., Coutifaris, C.G.V., & Pillemer, J. (2018). Emotional contagion in organizational life. Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D. E., & Pelletier, L. G. (2019). Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 60(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y. Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(50), 20254–20259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, R. D. (2000). Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi, C. A., Passmore, H-A., Nisbet, E.K, Zelenski, J.M., & Dopko, R.L. (2015). Flourishing in nature: A review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its applications as a positive psychology intervention. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5(4), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederström, C., & Spicer, A. (2015). The wellness syndrome. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. C., Lin, B. B., & Feng, X. (2024). A lower connection to nature is related to lower mental health benefits from nature contact. Sci Rep, 14, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, JH., Huang, CL., & Lin, YC. (2015). Mindfulness, Basic Psychological Needs Fulfillment, and Well-Being. J Happiness Stud, 16, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and emotion, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England journal of medicine, 357(4), 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. Volume, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. (2018). Mental health risk and resilience among climate scientists. Nature Clim Change, 8, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clear, J. (2018).Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Avery .

- Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W. B., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, *10*(1), 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribb, M., Mika, J. P., & Leberman, S. (2022). Te Pā Auroa nā Te Awa Tupua: the new (but old) consciousness needed to implement Indigenous frameworks in non-Indigenous organisations. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, (Original work published 2022). 18(4), 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippen, Matthew. (2021). Africapitalism, Ubuntu, and Sustainability. Environmental Ethics, 43(3), 235–259. Available online: https://philarchive.org/rec/CRIAUA. [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A., Harper, S.L., Minor, K., Hayes, K., Williams, K.G., & Howard, C. (2020). Ecological grief and anxiety: the start of a healthy response to climate change? The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(7), E261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.W., Harper, S.L., & Ford, J.D. (2013). Climate change and mental health: an exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Climatic Change, 121, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A, & Neville, R.E. (2018). "Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. "Nature Climate Change, 8, no. 4 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, J., Lavanga, M., & Spekkink, W. (2024). Exploring the clothing overconsumption of young adults: An experimental study with communication interventions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what "and "why "of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.N., Bradshaw, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Basarkod, G., Ciarorochi, J., Duineveld, J.J., Guo, J., & Sahdra, B.K. (2019). Mindfulness and its association with varied types of motivation: A systematic review and meta-analysis using Self-Determination Theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1–18. Available online: https://josephciarrochi.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/donald-et-al-ciarrochi-mindfulness-and-motivation.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management science, 60(11), 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, T., Kjønstad, B. G., & Barstad, A. (2014). Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecological Economics 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farb, N. A., Segal, Z. V., Mayberg, H., Bean, J., McKeon, D., Fatima, Z., & Anderson, A. K. (2007). Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, *2*(4), 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farb, N. A., Anderson, A. K., & Segal, Z. V. (2012). The mindful brain and emotion regulation in mood disorders. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 57(2), 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farb, N., Daubenmier, J., Price, C. J., Gard, T., Kerr, C., Dunn, B. D., Klein, A. C., Paulus, M. P., & Mehling, W. E. (2015). Interoception, contemplative practice, and health. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C. R. (Ed.). (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, C. (2019). A river is born: New Zealand confers legal personhood on the Whanganui River to protect it and its native people. In Sustainability and the Rights of Nature in Practice (pp. 259–278). CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fioramonti, L., Coscieme, L., Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Trebeck, K., Wallis, S., & De Vogli, R. (2022). Wellbeing economy: an effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecological Economics, 192, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D., Stanszus, L., Geiger, S., Grossman, P., & Schrader., U. (2017). Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T., Poppelaars, M., & Thabrew, H. (2023). The role of gamification in digital mental health. World Psychiatry, 22(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K. C., Dixon, M. L., Nijeboer, S., Girn, M., Floman, J. L., Lifshitz, M., Ellamil, M., Sedlmeier, P., & Christoff, K. (2016). Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 65, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K. C., Nijeboer, S., Dixon, M. L., Floman, J. L., Ellamil, M., Rumak, S. P., Sedlmeier, P., & Christoff, K. (2014). Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 43, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, H.E., Alabanese, A., Sun, S., Saadeh, F., Johnson, B.T., Elwy, A.R., & Loucks, E.B. (2024). Mindfulness-Based stress reduction health insurance coverage: If, how, and when? An integrated knowledge translation (iKT) Delphi key informant analysis. Mindfulness, 15, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, J., Friedrich, C., Dawson, A. F., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Gebbing, P., Delgado-Suárez, I., Gupta, R., Dean, L., Dalgleish, T., White, I. R., & Jones, P. B. (2021). Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS medicine, 18(1), e1003481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Campayo, J., Demarzo, M., Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2017). How Do Cultural Factors Influence Teaching and Practice of Mindfulness and Compassion in Latin Countries? Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, SM, Otto. (2018). Mindfully Green and Healthy: An Indirect Path from Mindfulness to Ecological Behavior. Front Psychol. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, N., Gaspar, Swim, Fraser, & J., *!!! REPLACE !!!*. (2019). Untangling the components of hope: Increasing pathways (not agency) explains the success of an intervention that increases educators’ climate change discussions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C. K., Siegel, R. D., & Fulton, P. R. (Eds.). (2005). Mindfulness and psychotherapy. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. (2011). The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, A., & Gross, J. J. (2020). Digital emotion contagion. Trends in cognitive sciences, 24(4), 316–328. Available online: https://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/abstract/S1364-6613(20)30027-9. [CrossRef]

- Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion, *10*(1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. (2013). Focus: The hidden driver of excellence. HarperCollins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. American journal of sociology, 83(6), 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J., Reiner, K., & Meiran, N. (2012). "Mind the trap": Mindfulness practice reduces cognitive rigidity. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e36206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children's self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F., & Liu, J. (2022). Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Employee Workplace Green Behavior: Moderated Mediation Model of Green Role Modeling and Employees’ Perceived CSR. Sustainability, 14(19), 11965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, L., Thom, N. J., Shukla, A., Davenport, P. W., Simmons, A. N., Stanley, E. A., & Johnson, D. C. (2016). Mindfulness-based training attenuates insula response to an aversive interoceptive challenge. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, *11*(1), 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J. P., Furman, D. J., Chang, C., Thomason, M. E., Dennis, E., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biological Psychiatry, *70*(4), 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrando, C., & Constantinides, E. (2021). Emotional contagion: A brief overview and future directions. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 712606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, H. E. (2011). Future self-continuity: how conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1235, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C. (2020). We need to (find a way to) talk about Eco-anxiety. Journal of Social Work Practice, 34(4), 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet. Planetary health, 5(12), e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival (2nd Edition). McGraw-Hill, London. [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action from a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspectives on psychological science: a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Roses, J. (2023). Barcelona’s Superblocks as Spaces for Research and Experimentation. The Journal of Public Space, 8(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J. E. M., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. B. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytman, L., Amestoy, M.E., & Ueberholz, R.Y. (2025). Cultural Adaptations of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Psychosocial Well-Being in Ethno-Racial Minority Populations: A Systematic Narrative Review. Mindfulness, 16, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J., Jovic, E., & Brinkerhoff, M.B. (2009). Personal and Planetary Well-being: Mindfulness Meditation, Pro-environmental Behavior and Personal Quality of Life in a Survey from the Social Justice and Ecological Sustainability Movement. Soc Indic Res, 93, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josipovic, Z. (2014). Neural correlates of nondual awareness in meditation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, *1307*(1), 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A Decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated Evidence of Conscious and Unconscious Bolstering of the Status Quo. Political Psychology, 25(6), 881–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karremans, J. C., Schellekens, M. P., & Kappen, G. (2017). Bridging the Sciences of Mindfulness and Romantic Relationships. Personality and social psychology review: an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 21(1), 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Ricard, M., & Singer, T. (2014). Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 9(6), 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, B. E., Coffey, K. A., Cohn, M. A., Catalino, L. I., Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Algoe, S. B., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological science, 24(7), 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T. R. A., Schuyler, B. S., Mumford, J. A., Rosenkranz, M. A., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Impact of short-and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage, 181, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, D, Hamblin, MR, & Lakshmanan, S. (2015). Meditation and Yoga can Modulate Brain Mechanisms that affect Behavior and Anxiety-A Modern Scientific Perspective. Anc Sci, 2(1), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., Evans, A., Radford, S., Teasdale, J. D., & Dalgleish, T. (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour research and therapy, 48(11), 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A. J., Malaktaris, A. L., Casmar, P., Baca, S. A., Golshan, S., Harrison, T., & Negi, L. (2019). Compassion meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: A randomized proof of concept study. Journal of traumatic stress, 32(2), 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. neuroreport, 16(17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeDoux, JE. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci, 23, 155–84. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10845062/. [CrossRef]

- Lengieza, M. L., Swim, J. K., & Hunt, C. A. (2019). Effects of post-trip eudaimonic reflections on affect, self-transcendence and philanthropy. The Service Industries Journal, 41(3–4), 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2014). Mindfulness Meditation Reduces Implicit Age and Race Bias: The Role of Reduced Automaticity of Responding. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 284–291, (Original work published 2015). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, *12*(4), 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Cultural variation in the self-concept. In The self: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 18–48). Springer New York; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: Plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Global Environmental Politics, 1(3), 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual review of psychology, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: a measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Environ. Psychol., 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Stress, 3(1), 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A., & Malinowski, P. (2009). Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and cognition, 18(1), 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Grandpierre, Z. (2019). Mindfulness in nature enhances connectedness and mood. Ecopsychology, 11(2), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. The MIT Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhfvf.

- Norton, T. A., Parker, S. L., Zacher, H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2015). Employee Green Behavior: A Theoretical Framework, Multilevel Review, and Future Research Agenda. Organization & Environment, 28(1), 103–125. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26164724.

- Nummenmaa, L., Hirvonen, J., Parkkola, R., & Hietanen, J. K. (2008). Is emotional contagion special? An fMRI study on neural systems for affective and cognitive empathy. NeuroImage, 43(3), 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S., & Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). “Fear Won’t Do It”: Promoting Positive Engagement With Climate Change Through Visual and Iconic Representations. Science Communication, 30(3), 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyler, D. L., Price-Blackshear, M. A., Pratscher, S. D., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2021). Mindfulness and intergroup bias: A systematic review. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(4), 1107–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, A., Giacomantonio, M., Carrus, G., Maricchiolo, F., Pirchio, S., & Mannetti, L. (2017). Mindfulness, Pro-environmental Behavior, and Belief in Climate Change: The Mediating Role of Social Dominance. Environment and Behavior, 50(8), 864–888, (Original work published 2018). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B., & Johnson, G. (2021). Beyond greenwashing: Addressing ‘the great illusion’of green advertising. Responsible Organization Review, 16(2), 59–66. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/journal-responsible-organization-review-2021-2-page-59?lang=en. [CrossRef]

- Patel, T., & Holm, M. (2017). Practicing mindfulness as a means for enhancing workplace pro-environmental behaviors among managers. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(13), 2231–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S., Sassenrath, C., & Schindler, S. (2016). Feelings for the Suffering of Others and the Environment: Compassion Fosters Proenvironmental Tendencies. Environment and Behavior, 48(7), 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D. N. (2018). What is critical environmental justice? Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.J, Ruiter, R.A., & Kok, G. (2013). Threatening communication: a critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychology Review, 7:sup1, S8–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poonamallee, L. (2021, ). Social Mindfulness Adoption and Functional Use in a Classroom Context: A Qualitative Exploration. Academy of Management Proceedings. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L. (2020). Expansive Leadership: Cultivating Mindfulness to Lead Self and Others in a Changing World– A 28-Day Program (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L. (2010). Advaita (Non-dualism) as Metatheory: A Constellation of Ontology, Epistemology, and Praxis. INTEGRAL REVIEW, 6(3). Available online: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1391&context=business-fp.

- Poonamallee, L., & Joy, S. (2021). Rousing Collective Compassion at Societal Level: Lessons from Newspaper Reports on Asian Tsunami in India. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 11(1), 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L., & Joy, S. (2018). Connecting the Micro to the Macro: An exploration of Micro-behaviors of individuals who drive CSR initiatives at the Macro-Level. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L. C., Goltz, S. M. (2014). "Beyond Social Exchange Theory: An Integrative Look at Transcendent Mental Models for Engagement", Integral Theory (Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 63-90). https://integral-review.org/beyond-social-exchange-theory-an-integrative-look-at-transcendent-mental-models-for-engagement/ .

- Proulx, J., & Bergen-Cico, D. (2022). Exploring the adaptation of mindfulness interventions to address stress and health in Native American communities. In C. M. Fleming, V. Y. Womack, & J. Proulx (Eds.), Beyond White mindfulness: Critical perspectives on racism, well-being and liberation (pp. 110–124). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, J., Croff, R., & Oken, B. (2018). Considerations for Research and Development of Culturally Relevant Mindfulness Interventions in American Minority Communities. Mindfulness, 9, 361–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purser, R. E. (2019). McMindfulness: How mindfulness became the new capitalist spirituality. Repeater Books. [Google Scholar]

- Raichle, M. E., MacLeod, A. M., Snyder, A. Z., Powers, W. J., Gusnard, D. A., & Shulman, G. L. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, *98*(2), 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstetter, L., Rupprecht, S., Mundaca, L., Osika, W., Stenfors, C. U. D., Klackl, J., & Wamsler, C. (2023). Fostering collective climate action and leadership: Insights from a pilot experiment involving mindfulness and compassion. iScience, 26(3), 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J., Narayanan, J., & Ho, Z. W. (2015). Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness, 6(1), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M., Passmore, H. A., Lumber, R., Thomas, R., & Hunt, A. (2021). Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship. International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(1). Available online: https://www.internationaljournalofwellbeing.org/index.php/ijow/article/view/1267. [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A., Browning, M. H. E. M., Lee, K., & Shin, S. (2018). Access to Urban Green Space in Cities of the Global South: A Systematic Literature Review. Urban Science, 2(3), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2013). Greening organizations through leaders' influence on employees' pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, & Everett. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5823-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz, M. A., Davidson, R. J., Maccoon, D. G., Sheridan, J. F., Kalin, N. H., & Lutz, A. (2013). A comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and an active control in modulation of neurogenic inflammation. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 27(1), 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, C. C., & Fehr, E. (2014). The neurobiology of rewards and values in social decision making. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 15(8), 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R., Huta, V., & Deci, E.L. (2008). Living well: a self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J Happiness Stud, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N., & Wölfl, V. (2025). Impact of Constructive Narratives About Climate Change on Learned Helplessness and Motivation to Engage in Climate Action. Environment and Behavior, 57(1-2), 75–117, (Original work published 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, O. S. (2024). Ubuntu and the Problem of Belonging. Ethics, Policy and Environment, 27(3), 350–370. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21550085.2023.2179818. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.P., Ryan, R.M., Niemiec, C.P., & et al. Mindfulness, Work Climate, and Psychological Need Satisfaction in Employee Well-being, (2015). Mindfulness, 6, 971–985. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P. W., Shriver, C., Tabanico, J. J., & Khazian, A. M. (2004). Implicit connections with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2018). Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: A meta-analytic investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P., & Schultz, M.D. (2022). From Greenwashing to Machinewashing: A Model and Future Directions Derived from Reasoning by Analogy. J Bus Ethics, 178, 1063–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Selye, H. (1976). Stress in Health and Disease. Butterworths; Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Sherell, J., & Simmer-Brown. (2017). Spiritual bypassing in the contemporary mindfulness movement. ICEA Journal, 1(1), 75–93. Available online: http://www.contemplativemind.org/files/ICEA_vol1_2017.pdf.

- Soutar, C, & Wand, APF. 2022. Understanding the Spectrum of Anxiety Responses to Climate Change: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(2), 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanszus, L. S., Frank, P., & Geiger, S. M. (2019). Healthy eating and sustainable nutrition through mindfulness? Mixed method results of a controlled intervention study. Appetite, 141, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg L., Vlek C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K. M., Vogus, T. J., & Dane, E. (2016). Mindfulness in organizations: A cross-level review. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior, 3(1), 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P., & Milfont, T. L. (2020). Towards cross-cultural environmental psychology: A state-of-the-art review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 71, Article 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, *16*(4), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y, Geng, L, Schultz, PW, Zhou, K, & Xiang, P. (2017). The effects of mindful learning on pro-environmental behavior: A self-expansion perspective. Conscious Cogn, 51, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasino, B., Fregona, S., Skrap, M., & Fabbro, F. (2013). Meditation-related activations are modulated by the practices needed to obtain it and by the expertise: an ALE meta-analysis study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, *6*, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trammel, R. C. (2017). Tracing the roots of mindfulness: Transcendence in Buddhism and Christianity. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 36(3), 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vago, DR, & Silbersweig, DA. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front Hum Neurosci, 6, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, T.W. (2012). Network Interventions. Science, 337, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N. J., Van Lange, D. A. W., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2013). Social mindfulness: Skill and will to navigate the social world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. (2020), "Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability", International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 112-130 . [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. (2018). Mind the gap: The role of mindfulness in adapting to increasing risk and climate change. Sustain Sci, 13, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C., & Brink, E. (2018). Mindsets for sustainability: Exploring the link between mindfulness and sustainable climate adaptation. Ecological Economics 153, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C., & Bristow, J. (2022). At the intersection of mind and climate change: integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice. Climatic Change, 173, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C., Schäpke, N., Fraude, C., Stasiak, D., Bruhn, T., Lawrence, M., & Mundaca, L. (2020). Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environmental science & policy, 112, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C., Brossmann, J., Hendersson, H., Kristjansdottir, R., McDonald, C., & Scarampi, P. (2018). Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustainability science, 13(1), 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Wenxu Mao Lu, Z. Sun, Chongyu, Hu, Y. (2025). Mindfulness empowers employees' green performance: The relationship and cross-level mechanisms between green mindfulness leadership and employees’ green behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume, 103, 102585. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494425000684. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Wallace, J., Land, C., & Patey, J. (2023). Re-organising wellbeing: Contexts, critiques and contestations of dominant wellbeing narratives. Organization, 30(3), 441–452, (Original work published 2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., Przybylski, A. K., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Personality & social psychology bulletin, 35(10), 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of personality and social psychology, 98(2), 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L., & O'Neill, S. (2010). Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.H., German, D., & Ricker, A. (2013). Feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a culturally informed intervention to decrease stress and promote well-being in reservation-based Native American Head Start teachers. BMC Public Health, 23, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59(4), 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M., Otten, S., Schötz, E., Sarikaya, A., Lehnen, H., Jo, H.-G., Kohls, N., Schmidt, S., & Meissner, K. (2015). Subjective expansion of extended time-spans in experienced meditators. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombé, C. L., & Gaylord, S. A. (2014). The cultural relevance of mindfulness meditation as a health intervention for African Americans: Implications for reducing stress-related health disparities. Journal of Holistic Nursing 32, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. (2021). Mindfulness and moral outrage: Friends or foes? Philosophy East and West, 71(3), 825–841. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L., & Zellmer-Bruhn, M. (2018). Introducing Team Mindfulness and Considering its Safeguard Role Against Conflict Transformation and Social Undermining. AMJ, 61, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusainy, C., & Lawrence, C. (2015). Brief mindfulness induction could reduce aggression after depletion. Consciousness and cognition, 33, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuroff, D. C., Koestner, R., Moskowitz, D. S., McBride, C., & Bagby, R. M. (2012). Therapist’s autonomy support and patient’s self-criticism predict motivation during brief treatments for depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31(9), 903–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylowska, L., Ackerman, D. L., Yang, M. H., Futrell, J. L., Horton, N. L., Hale, T. S., Pataki, C., & Smalley, S. L. (2008). Mindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD: a feasibility study. Journal of attention disorders, 11(6), 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).