Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Sustainable Consumption and Active Participation

1.2. General Willingness of Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Agency in Young Adults

1.3. Eco-Worry and Eco-Anxiety: Two Ways of Feeling Climate Change

1.4. Objectives and Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Control Variables

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.2.3. Mediating Variables

2.2.4. Outcomes Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

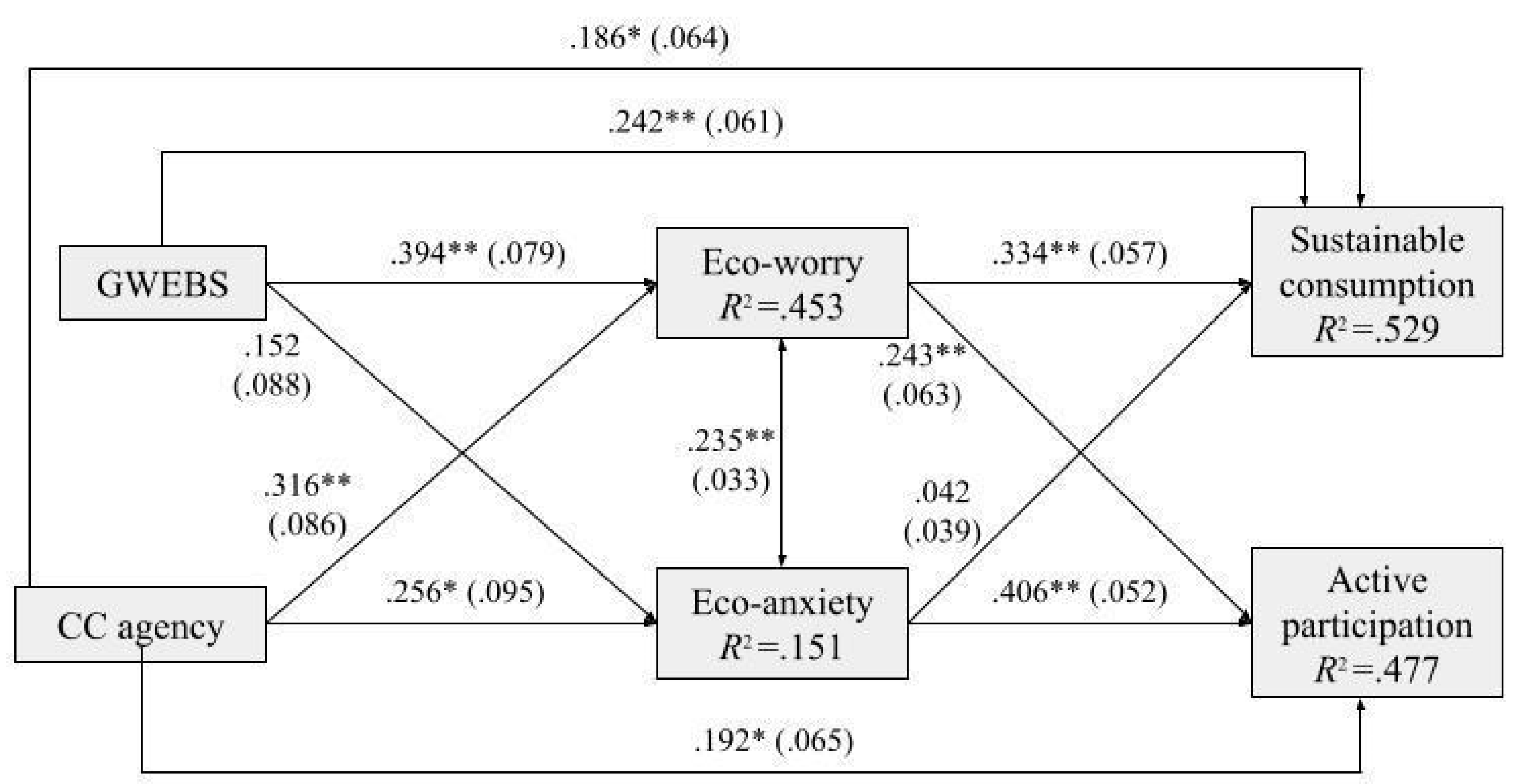

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Climate Change |

| PEB | Pro-Environmental Behavior |

| SC | Sustainable Consumption |

| AP | Active Participation |

| GWEBS | General Willingness of Environmental Behavior |

References

- United Nations (UN). WMO Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update (2024-2028); World Meteorological Organization, June 5, 2024. [Online] https://library.wmo.int/records/item/68910-wmo-global-annual-to-decadal-climate-update.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 77th World Health Assembly. Daily Update: May 31, 2024; WHO, 2024. [Online] https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA77/A77_ACONF7-sp.pdf.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6); IPCC, 2023. [Online] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf.

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2025; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2025. [Online] https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_Press_Release_2025_ESP.pdf.

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N. M. P.; Hultink, E. J. The Circular Economy – A New Sustainability Paradigm? J Clean Prod 2017, 143, 757–768. [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Stockholm+50: A Healthy Planet for the Prosperity of All—Our Responsibility, Our Opportunity. Official Report, A/CONF.238/9; UN, August 1, 2022.

- Coppola, I. Eco-Anxiety in “the Climate Generation”: Is Action an Antidote?; Environmental Studies Electronic Thesis Collection, 2021; No. 71. [Online] https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/envstheses/71.

- Bradley, G. L.; Deshpande, S.; Paas, K. H. W. The Personal and the Social: Twin Contributors to Climate Action. J Environ Psychol 2024, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate Anxiety: Psychological Responses to Climate Change. J Anxiety Disord 2020, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R. The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. American Psychologist 2011, 66(4), 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12(19). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Relate to Climate Change? Implications for Developmental Psychology. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 2023, 20(6), 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Evans, G. W.; Moon, M. J.; Kaiser, F. G. The Development of Children’s Environmental Attitude and Behavior. Global Environmental Change 2019, 58, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Amérigo, M.; García, J. A. Evaluación de Una Intervención Proambiental En Escolares de Educación Primaria (10-13 Años) de Castilla-La Mancha (España). Revista Electrónica Educare 2021, 25(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Goyal, P. The Evolution of Pro-environmental Behavior Research in Three Decades Using Bibliometric Analysis. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 2024, 31(5), 4133–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oinonen, I.; Paloniemi, R. Understanding and Measuring Young People’s Sustainability Actions. J Environ Psychol 2023, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. Journal of Social Issues 2000, 56(3), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C. A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K. L.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S. D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J. A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Lu, S.; Jiang, F.; Maran, D. A.; Yadav, R.; Ardi, R.; Chegeni, R.; Ghanbarian, E.; Zand, S.; Najafi, R.; Park, J.; Tsubakita, T.; Tan, C. S.; Chukwuorji, J. B. C.; Ojewumi, K. A.; Tahir, H.; Albzour, M.; Reyes, M. E. S.; Lins, S.; Enea, V.; Volkodav, T.; Sollar, T.; Navarro-Carrillo, G.; Torres-Marín, J.; Mbungu, W.; Ayanian, A. H.; Ghorayeb, J.; Onyutha, C.; Lomas, M. J.; Helmy, M.; Martínez-Buelvas, L.; Bayad, A.; Karasu, M. Climate Anxiety, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Action: Correlates of Negative Emotional Responses to Climate Change in 32 Countries. J Environ Psychol 2022, 84. [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V. H. M.; Siegrist, M. Addressing Climate Change: Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Act and to Support Policy Measures. J Environ Psychol 2012, 32(3), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Martín, J. A. Análisis Del Perfil Proambiental de La Población Castellanomanchega; Ediciones parlamentarias [i.e. Cortes de Castilla-La Mancha], 2022.

- Krettenauer, T.; Lefebvre, J. P.; Goddeeris, H. Pro-Environmental Behaviour, Connectedness with Nature, and the Endorsement of pro-Environmental Norms in Youth: Longitudinal Relations. J Environ Psychol 2024, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F.; Liu, Y. Pro-Environmental Behavior in an Aging World: Evidence from 31 Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(4), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Kleinhückelkotten, S. Good Intents, but Low Impacts: Diverging Importance of Motivational and Socioeconomic Determinants Explaining Pro-Environmental Behavior, Energy Use, and Carbon Footprint. Environ Behav 2018, 50(6), 626–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Balázs, B.; Mónus, F.; Varga, A. Age Differences and Profiles in Pro-Environmental Behavior and Eco-Emotions. Int J Behav Dev 2024, 48(2), 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeirytė, A.; Krikštolaitis, R.; Liobikienė, G. The Differences of Climate Change Perception, Responsibility and Climate-Friendly Behavior among Generations and the Main Determinants of Youth’s Climate-Friendly Actions in the EU. J Environ Manage 2022, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F.; Sánchez, M. Key Factors to Explain Recycling, Car Use and Environmentally Responsible Purchase Behaviors: A Comparative Perspective. Resour Conserv Recycl 2015, 99, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Wiernik, B.; S. Ones, D.; Dilchert, S. Age and Environmental Sustainability: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2013, 28(7/8), 826–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, L.; Poggio, L. Biased Perception of the Environmental Impact of Everyday Behaviors. J Soc Psychol 2023, 163(4), 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). Study No. 3391. Spanish General Social Survey 2023 (ESGE) / Environment (III); CIS, 2023a. [Online] https://www.cis.es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&idEstudio=14714.

- Kukkonen, N.; Lange, F.; Van den Bossche, C.; Krebs, R. Pro-Environmental Decisions Are Hampered by Their Opportunity Costs – Evidence from Effort-Based Decision-Making. December 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Adult Education and Training Participation Statistics - Updated Data for 2023; Eurostat, European Commission, 2024. [Online] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240930-2.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). Study No. 3423. October 2023 Barometer; CIS, 2023b. [Online] https://www.cis.es/documents/d/cis/es3423mar-pdf.

- Yang, R. Education And Environment-Friendly Behavior: The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, 35, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics (INE). CNED-2014. Education and Training Statistics. Eurostat. 3.9.2 Educational Level of the Adult Population by Age Groups. CNED-2014. Series 2014-2023; INE, 2023. [Online] https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=12726.

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Youth Travelers and Waste Reduction Behaviors While Traveling to Tourist Destinations. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 2018, 35(9), 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Slade, E. L.; Dwivedi, Y. K. Examining Antecedents of Consumers’ pro-Environmental Behaviours: TPB Extended with Materialism and Innovativeness. J Bus Res 2021, 122, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecina, M. L.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; López-García, L.; Díaz-Silveira, C. Eco-Anxiety and Trust in Science in Spain: Two Paths to Connect Climate Change Perceptions and General Willingness for Environmental Behavior. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, E. L.; Jennings, N.; Kioupi, V.; Thompson, R.; Diffey, J.; Vercammen, A. Psychological Responses, Mental Health, and Sense of Agency for the Dual Challenges of Climate Change and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Young People in the UK: An Online Survey Study. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6(9), e726–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action control: From cognition to behavior; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zulkepeli, L.; Fauzi, M. A.; Mohd Suki, N.; Ahmad, M. H.; Wider, W.; Rahamaddulla, S. R. Pro-Environmental Behavior and the Theory of Planned Behavior: A State of the Art Science Mapping. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. E-Waste Recycling Behaviour: An Integration of Recycling Habits into the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J Clean Prod 2021, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J. G.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, M.; Alzate M Sabucedo, M. J. La Influencia de La Norma Personal y La Teoría de La Conducta Planificada En La Separación de Residuos. Medio Ambient. Comport. Hum 2009, 10(1y2), 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, PA: Addison Wesley 1975.

- OCU (Organización de Consumidores y Usuarios). Informe de Consumo Sostenible; OCU: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Online] https://www.ocu.org/organizacion/prensa/notas-de-prensa/2019/informeconsumosostenible070219.

- Triodos Bank. Implicación Activa de la Población Española Contra la Crisis Climática; Triodos Bank: Spain, 2024. [Online] https://www.triodos.es/es/notas-de-prensa/2024/implicacion-activa-poblacion-espanola-contra-crisis-climatica (accessed March 9, 2025).

- Vecina, M. L.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; Díaz-Silveira, C. Eco-Anxiety or Simply Eco-Worry? Incremental Validity Study in a Representative Spanish Sample. Front. Psychol. 2025, 17, accepted, in press.

- Hanss, D.; Doran, R.; Renkel, J. Evidence for Motivated Control? Climate Change Related Distress Is Positively Associated with Domain-Specific Self-Efficacy and Climate Action. https://credit.niso.org/.

- Jones, R. N. Incorporating Agency into Climate Change Risk Assessments. 2004.

- Toivonen, H. Themes of Climate Change Agency: A Qualitative Study on How People Construct Agency in Relation to Climate Change. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2022, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Yang, J. Z. Risk or Efficacy? How Psychological Distance Influences Climate Change Engagement. Risk Analysis 2020, 40(4), 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, G. Attitudes to Climate Change in Some English Local Authorities: Varying Sense of Agency in Denial and Hope; 2019; pp 195–215. [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A. M.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. From Believing in Climate Change to Adapting to Climate Change: The Role of Risk Perception and Efficacy Beliefs. Risk Analysis 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. S.; Feldman, L. The Influence of Climate Change Efficacy Messages and Efficacy Beliefs on Intended Political Participation. PLoS One 2016, 11(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen Hidalgo, M.; Pisano, G. Predictores de La Percepción de Riesgo y Del Comportamiento Ante El Cambio Climático. Un Estudio Piloto. Psyecology 2010, 1(1), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrasin, O.; von Roten, F. C.; Butera, F. Who’s to Act? Perceptions of Intergenerational Obligation and Pro-Environmental Behaviours among Youth. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14 (3). [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A.; Maleksaeidi, H. Pro-Environmental Behavior of University Students: Application of Protection Motivation Theory. Glob Ecol Conserv 2020, 22, e00908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukes, S.; Fox, R.; Hills, D.; White, P. J.; Ferguson, J. P.; Kamath, A.; Logan, M.; Riley, K.; Rousell, D.; Wooltorton, S.; Whitehouse, H. Eco-Anxiety and a Desire for Hope: A Composite Article on the Impacts of Climate Change in Environmental Education. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 2024, 40(5), 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Kossowski, B.; Marchewka, A.; Morote, R.; Klöckner, C. A. Emotional Responses to Climate Change in Norway and Ireland: A Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE) in Two European Countries and an Inspection of Its Nomological Span. Front Psychol 2024, 15, 1211272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C. A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu Rev Environ Resour 2021, 46(Volume 46, 2021), 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, M. L.; Weiss, K.; Aroua, A.; Betry, C.; Rivière, M.; Navarro, O. The Influence of Environmental Crisis Perception and Trait Anxiety on the Level of Eco-Worry and Climate Anxiety. J Anxiety Disord 2024, 101, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; Szczypiński, J.; Kossowski, B.; Budziszewska, M.; Michałowski, J. M.; Klöckner, C. A.; Marchewka, A. Beyond Climate Anxiety: Development and Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE): A Measure of Multiple Emotions Experienced in Relation to Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 2023, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C. J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When Worry about Climate Change Leads to Climate Action: How Values, Worry and Personal Responsibility Relate to Various Climate Actions. Global Environmental Change 2020, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T. L.; Stanley, S. K.; O’Brien, L. V.; Watsford, C. R.; Walker, I. Clarifying the Nature of the Association between Eco-Anxiety, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviour. J Environ Psychol 2024, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P. K.; Passmore, H.-A.; Howell, A. J.; Zelenski, J. M.; Yang, Y.; Richardson, M. The Continuum of Eco-Anxiety Responses: A Preliminary Investigation of Its Nomological Network. Collabra Psychol 2023, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A. I. On the Nature of Eco-Anxiety: How Constructive or Unconstructive Is Habitual Worry about Global Warming? J Environ Psychol 2020, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R. E.; Mayall, E. E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5(12), e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playground & Osoigo Next. The Future is Climate. Results Report; 2022. [Online] https://elfuturoesahora.org/survey-results.html.

- Noth, F.; Tonzer, L. Understanding Climate Activism: Who Participates in Climate Marches Such as “Fridays for Future” and What Can We Learn from It? Energy Res Soc Sci 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change. Zygon 2018, 53(2), 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H. A.; Lutz, P. K.; Howell, A. J. Eco-Anxiety: A Cascade of Fundamental Existential Anxieties. J. Constructivist Psychol. 2023, 36(2), 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, H.; Olson, J.; Paul, P. Eco-anxiety in Youth: An Integrative Literature Review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2023, 32(3), 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.; Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; Contreras, A. On Climate Anxiety and the Threat It May Pose to Daily Life Functioning and Adaptation: A Study among European and African French-Speaking Participants. Clim Change 2022, 173 (1–2). [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Lombardi, G. S.; Ciabini, L.; Zjalic, D.; Di Russo, M.; Cadeddu, C. How Can Climate Change Anxiety Induce Both Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Eco-Paralysis? The Mediating Role of General Self-Efficacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S. K.; Hogg, T. L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From Anger to Action: Differential Impacts of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Depression, and Eco-Anger on Climate Action and Wellbeing. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M. C.; Tröger, J.; Hamann, K. R. S.; Loy, L. S.; Reese, G. Anxiety and Climate Change: A Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale in a German-Speaking Quota Sample and an Investigation of Psychological Correlates. Clim Change 2021, 168(3-4), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, C.; Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety: What It Is and Why It Matters. Frontiers in Psychology. Frontiers Media S.A. September 23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Leite, Â.; Lopes, D.; Pereira, L. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation. 2023. [CrossRef]

- AERA; APA; NCME. The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, 2014.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, 1988.

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J. S. Multifaceted Conceptions of Fit in Structural Equation Models. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K. A., Long, J. S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, 1993; pp 10–39.

- Wheaton, B.; Muthén, B.; Alwin, D. F.; Summers, G. F. Assessing Reliability and Stability in Panel Models. In Sociological Methodology 1977; Heise, D. R., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, 1977; pp 84–136.

- Browne, M. W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K. A., Long, J. S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, 1993; pp 136–162.

- Marsh, H. W.; Hau, K. T.; Grayson, D. Goodness of Fit in Structural Equation Models. In Contemporary Psychometrics: A Festschrift for Roderick P. McDonald; Maydeu-Olivares, A., McArdle, J. J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, 2005; pp 225–340dels.

- Cheung, G. W.; Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K.; Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8.1 ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, 2017.

- Preacher, K. J.; Rucker, D. D.; Hayes, A. F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42(1), 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n | (%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 160 | (51.9) | |

| Male | 148 | (48.1) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Undergraduates students | 146 | (47.4) | |

| Bachelor's degree or university degree | 98 | (31.8) | |

| Master's or Ph. | 64 | (2.8) | |

| Socioeconomic level | |||

| I have no income | 89 | (28.9) | |

| €1,000 or less | 55 | (17.9) | |

| €1,001 - €2,000 | 113 | (36.7) | |

| €2,001 - €3,000 | 34 | (11) | |

| €3,001 - €4,000 | 11 | (3.6) | |

| More than €4,001 | 6 | (1.9) | |

| Media (SD) | Sk | K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| 1. Edu. level | 3.59 | (.972) | -.075 | -.891 | |||||||

| 2. Econom. level | 2.49 | (1.259) | .709 | .930 | .223** | ||||||

| 3. Eco-worry | 3.585 | (.852) | -.685 | .564 | .107 | .114* | |||||

| 4. Eco-anxiety | 2.574 | (.928) | -.076 | -.833 | .030 | .127* | .420** | ||||

| 5. GWEBS | 3.587 | (.879) | -.702 | .657 | .120* | .074 | .646** | .356** | |||

| 6. CC agency | 3.623 | (.835) | -.694 | .573 | .129* | .065 | .629** | .377** | .795** | ||

| 7. SC | 3.536 | (.787) | -.62 | .715 | .233** | .082 | .637** | .339** | .638** | .622** | |

| 8. AP | 2.349 | (.974) | .43 | -.606 | .114* | .167** | .544** | .588** | .470** | .505** | .556** |

| Estimate | 95% CI | |||

| GWEBS → Eco-worry → SC | .118 | [.062, | .200] | |

| GWEBS → Eco-worry → AP | .106 | [.052, | .184] | |

| CC agency → Eco-worry → SC | .099 | [.044, | .177] | |

| CC agency → Eco-worry → AP | .089 | [.040, | .164] | |

| GWEBS → Eco-anxiety → SC | .006 | [-.004, | .028] | |

| GWEBS → Eco-anxiety → AP | .068 | [-.002, | .154] | |

| CC agency → Eco-anxiety → SC | .010 | [-.008, | .042] | |

| CC agency → Eco-anxiety → AP | .121 | [.045, | .207] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).