1. Introduction

Our world is undergoing rapid environmental change, most prominently through anthropogenic climate change and its interconnected challenges, including biodiversity loss, extreme weather events, and growing ecological instability (e.g., [

1,

2]). In addition to their significant ecological and material consequences, these accelerating changes have profound social and psychological impacts. A growing body of research shows that climate change can negatively affect mental wellbeing by intensifying stress, anxiety, and feelings of loss and uncertainty [

3,

4]. Children, adolescents, and young adults appear to be particularly vulnerable, given that they are at formative stages of identity development and future planning while simultaneously facing an unprecedented sense of threat regarding their life course and prospects [

5,

6,

7]. Young adults (ages 16–35) are at a critical life stage in which habits, values, and coping strategies are formed, influencing long-term environmental engagement [

5]. Evidence suggests that environmental distress in these groups may manifest not only as heightened eco-anxiety but also as diminished wellbeing, hopelessness, and disengagement—while at the same time fostering new forms of activism and agency [

8].

Although an emerging body of research has examined climate-related emotions and environmental distress among young people internationally [

6,

7,

8], research on how these phenomena manifest in the Dutch context remains limited. The Netherlands constitutes a particularly relevant case, as this population is characterised by a distinctive social and environmental context: a high population density, increasing exposure to climate risks such as sea-level rise, and ongoing pressures from diffuse and cumulative stressors (e.g., pollution, biodiversity loss, urbanisation). These factors intersect with other influences on mental wellbeing [

9,

10]. At the time this research was conducted in 2023, the mental wellbeing of young people in the Netherlands was already under considerable strain, particularly as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic [

9]. However, the specific role of environmental distress and young people’s perspectives on climate change and environmental degradation in shaping their psychological wellbeing had received little attention. This underscored the need for focused research on this group and the importance of national-level studies to complement and contextualise international findings. Locally informed research can support the development of strategies that strengthen resilience and empower vulnerable groups such as Dutch young adults, as national and cultural contexts shape both experiences of distress and the resources available for coping.

The overarching aim of our research, of which the findings presented in this paper form a part, was to gain deeper insight into environmental distress, climate-related emotions, and related perceptions among young adults living in the Netherlands. To this end, we conducted a large nationally representative online survey in 2023 with 1,006 participants aged 16–35, stratified by gender, age, education level, and province [

11,

12] (under review). The survey comprised multiple components, predominantly fixed-response measures of environmental distress, climate emotions, trust, and coping strategies. In addition to examining levels of environmental distress and climate-related emotions, we explored participants’ perceived emotional needs in this context, as well as their views on individual responsibility and the barriers they encounter in pursuing a pro-environmental lifestyle. Two open-ended questions were included at the end of the survey to capture these emotional needs in the face of climate change and perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour—that is, the individual, social, or structural factors that may hinder young adults from adopting more sustainable lifestyles. These factors are explored in this study.

The results of these open-ended questions are interpreted in light of both the broader survey findings on climate-related emotions, presented here, and previously published results [

11,

12] (under review). To provide context, we first summarise the key findings of the already published survey components, conducted with the same nationally representative sample, followed by the rationale for focusing specifically on emotional needs and perceived barriers. We conclude by outlining the theoretical framework underpinning this study.

1.1. Context of the Online Survey: What We Already Know

The first part of the survey focused on environmental distress and solastalgia, examining how factors such as place attachment, sense of control, trust, and personality moderated the psychological stress response of the 1,006 Dutch young adults [

11]. Participants (16-35 years) most commonly reported stress in their natural environment related to noise (~22%), loss of natural areas (~20%), and heat (~18%), with the latter two perceived as most threatening. Approximately one fifth of 1,006 Dutch young adults indicated that environmental distress limited their enjoyment of life, while nearly a quarter expressed worries about the future. Feelings of powerlessness (~27%) and low trust in government were also reported. The findings revealed a significant portion of young adults experiencing environmental distress, while others appeared indifferent.

Our second study explored emotional responses to climate change, in particular climate change distress and denial [12 (under review)]. Using latent profile analysis, six distinct subgroups were identified among the same representative sample: burdened worriers, unburdened worriers, climate change deniers, sceptic worriers, ‘Not in My BackYard (NIMBY)’s, and conflicted sceptics. Distress and denial coexisted in complex patterns, with high-distress profiles associated with hope and proactive coping, and denial-heavy profiles linked to fatalism, lower institutional trust, and reduced engagement. Minimal differences were observed across gender, age, income, or living environment, and none by education. This study underscored the nuanced ways in which Dutch youth emotionally respond to climate change and highlights the need for interventions that consider these diverse profiles.

1.2. Emotional Needs Related to Climate Change

International research on how young people perceive their psychological and emotional needs in the face of environmental distress is growing in number, but several key themes have been identified in most studies. Many adolescents and young adults report a need for hope, empowerment, and constructive engagement to counter feelings of helplessness and climate anxiety [

7,

8]. These youth emphasize the importance of being heard and taken seriously by adults, policymakers, and institutions [

6], as well as opportunities to engage in collective and meaningful climate action that fosters agency and belonging [

13,

14]. Moreover, supportive social networks and open dialogue with peers, teachers, and parents are described as crucial for processing climate-related emotions [

15,

16]. These findings suggest that addressing environmental distress among youth requires more than individual coping strategies; it calls for relational, societal, and policy-level responses that acknowledge their concerns and enable constructive participation.

1.3. Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behaviour

Global awareness of environmental issues grew rapidly in the 20th century. A 2024 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) survey on climate action—conducted among over 73,000 people in 77 countries, representing 87% of the world’s population—revealed a strong global consensus: 80% of adults called for more decisive government action to address climate change [

17]. Globally, only a small share of adults (7%) believe that their country should not transition at all, while a large majority (79%) want wealthier nations to help poorer countries adapt [

17]. Public perceptions of environmental issues are also shifting in the Netherlands. Almost half (45%) of Dutch young adults (ages 18–24) viewed environmental pollution as a serious problem in 2019, although only 11% considered it a major issue [

18]. In recent years the Eurobarometer showed that 91% of 15–24-year-olds believe that tackling climate change can improve their health and well-being [

19]. Moreover, most young adults (60%) acknowledge the need for a more climate-conscious lifestyle [

20]. However, research highlights a significant gap between these pro-sustainability attitudes and actual behaviour [

21]—for example, more than 60% of 18–25-year-olds reported flying in the past year [

20], few follow a plant-based diet [

20], and many continue to purchase new clothing [

22].

Perspectives on individual responsibility for sustainability vary across regions [

21]. For example, a survey of 1,000 American adults showed half of them believed that businesses should promote sustainable practices, and only a third saw sustainability as a personal responsibility [

23]. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behaviours are also influenced by individual characteristics such as personality traits and perceptions, and cultural and regional contexts [

24,

25,

26]. Analysing data from the 2016/2017 European Social Survey, Martin et al. [

27] found that adolescents and young adults who felt personally responsible for addressing climate change reported greater happiness and life satisfaction. In contrast, frequent worry about climate change was associated with lower well-being ([

27], see also [12 (under review]).

Despite growing awareness, barriers to pro-environmental behaviour persist in everyday settings—at home, school, work, and in public spaces [

21]. These barriers span a range of factors, including informational gaps, psychological perceptions, social norms, and cultural influences [

28,

29]. In Europe, sustainable consumption behaviours are linked to higher levels of environmental knowledge and risk perception [

30]. Moreover, feeling empowered to act sustainably can help reduce environmental distress and foster collective engagement (e.g., [

7]). The United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP)

Global Survey on Sustainable Lifestyles highlights that young adults around the world aspire to contribute to sustainability but often look for clearer guidance on how to do so effectively [

31]. In general, youth are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviours when they observe others doing the same, demonstrating the influence of social proof [

32].

1.4. Theoretical Framework

While there is a growing body of research on the psychological impacts of climate change, most studies have focused either on the relationship between environmental distress and pro-environmental behaviour (e.g., [

33,

34]) or on the emotional experiences of young people in the face of climate change (e.g., [

35]). Other work has highlighted the ambivalent role of climate-related emotions, which may both motivate and hinder sustainable engagement [

36,

37]. However, few studies have simultaneously examined environmental distress, perceived barriers to sustainable behaviour, and the emotional needs that young people articulate in coping with environmental change. By combining these dimensions in a large, representative sample of Dutch young adults, the present study contributes novel insights into how cognitive, behavioural, and emotional factors intersect in shaping responses to climate change.

Most existing research on climate-related emotions and sustainable behaviour has relied on quantitative survey instruments with closed, theory-driven items, such as standardized scales for pro-environmental intentions or climate anxiety [

38,

39,

40]. While such approaches are valuable for identifying broad patterns, they constrain participants to predefined categories. The present study is distinctive in combining a large, representative sample with open-ended questions that invite young adults to articulate in their own words the barriers they face and the emotional needs they experience in relation to environmental change. This design makes it possible to capture unanticipated themes and nuances, thereby complementing the largely quantitative literature with richer insights into how environmental distress, behavioural obstacles, and psychological needs intersect in everyday life.

Although this study is exploratory in nature, our research questions are informed by existing theoretical frameworks. The question on perceived barriers to sustainable behaviour resonates with the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB; [

41]). TPB posits that behaviour is influenced by individuals’ attitudes toward the behaviour, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms. This framework provides insight into which personal and social factors facilitate or hinder sustainable actions [

41]. In our study, we particularly explore the construct of perceived behavioural control. The question on emotional needs in the face of climate change aligns with perspectives from environmental psychology, which emphasize the role of emotions, coping, and psychological resilience in relation to climate change (e.g., [

42,

43]). Rather than applying these frameworks in a formal, hypothesis-driven manner, we use them as guiding perspectives to situate our exploratory findings within broader theoretical debates.

1.5. Aim of This Research

The aim of present study is to explore the emotional and psychological needs related to environmental distress, and the perceived barriers to sustainable behaviour as freely reported by Dutch young adults (ages 16–35) in two open textboxes. By analysing these written data from a 2023 survey on environmental distress, solastalgia [

11], and climate change-related emotions [12 (under review)], we seek to explore (1) the emotional needs concerning climate change and (2) perceived barriers and sense of personal responsibility regarding sustainable behaviour among Dutch young adults. Understanding these needs and perceived barriers within the Dutch context is essential for developing effective, culturally appropriate interventions and policies that foster both sustainable behaviour and emotional resilience among young adults.

2. Materials and Methods

The questionnaire-based study was conducted between February 27 and March 9, 2023, and included demographic variables, personality traits (BFI-10; [

44]), self-perceived mental and physical health, environmental distress, climate change-related emotions (including the validated Climate Anxiety Scale; ([

38]; Dutch translation: [12 (under review)]), and trust [12 (under review)]. Detailed descriptions of the survey design, questionnaire development, and results are provided in Venhof et al. [

11] and Reitsema et al. [12 (under review)]. The full Dutch environmental distress questionnaire and its English translation are available online [

45].

The participating Dutch young adults were asked to indicate the intensity of 12 emotions related to climate change over the past four weeks using a 0–100 Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 0 = ‘no emotion’, 100 = ‘very strong emotion’). To compare climate-specific emotions with general emotional states, four emotions—loneliness, anxiety, depressed mood, and stress—were selected, as these were also assessed at the beginning of the questionnaire in a general context (see [

11]). Participants thus rated each of these four emotions twice: once for their general emotional state and once specifically in relation to climate change.

The survey also included

20 self-designed items by the first author, presented on a 5-point Likert scale. These items were based on, and adapted with permission from, a qualitative study on eco-emotions [

46] and adjusted to the Dutch context. Specifically, the items covered eco-anxiety (6 items), eco-guilt (8 items), and eco-coping including pro-environmental behaviour (6 items). Part of these data has been used in a latent profile analysis on climate change distress and denial [12 (under review)]. However, descriptive results were not presented in that paper; here, we include them to provide context for interpreting the findings of the current study, which focuses on two open-ended questions regarding perceived emotional needs related to climate change and perceived barriers to sustainable behaviour.

The

two open-ended questions (see

Table 1) were presented at the end of the survey and form the primary focus of this paper. These questions were developed by the authors. Participants were asked to provide a maximum of three written responses in a text box for each question; skipping was not allowed. For both questions, a fixed response option was available if the question was not relevant to the participant.

Participants were recruited through Flycatcher Internet Research, a panel certified for quality (ISO 20252) and environmental standards (ISO 14001). Eligibility criteria included being 16–35 years old, residing in the Netherlands, Dutch literacy, and providing informed consent. The final sample consisted of 1,006 Dutch young adults aged 16–35 (M = 25.9, [SD = 5.6]), of whom 51% identified as women. Stratified sampling was applied based on gender, age, education level, and province, and data collection followed the ‘Golden Standard’ calibration instrument [

47] to ensure national representativeness. Participants provided informed consent and completed digital questionnaires that included built-in measures to minimize missing or inconsistent data. Ethical approval was granted by Maastricht University (FHML-REC/2022/130), and participants received a small financial incentive. This study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Heymans Data Collection Fund, neither of which influenced the study design or outcomes.

2.1. Data Analysis

After the closure of the online survey, all responses from the 1,006 participants were transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28.0) by an independent researcher from Flycatcher Internet Research. This included the responses to the open-ended questions displayed in

Table 1.

For the four climate related emotions that were rated by sliding a VAS scale slider bar (0-100), descriptive statistics were calculated, with mean, SD, median and interquartile range (IQR). The median indicates the central tendency of the VAS scores, while the IQR reflects the spread of the middle 50% of responses, providing a robust measure of variability less affected by extreme values. Because VAS scores were not normally distributed, non-parametric analyses were conducted. Paired comparisons between general and climate-specific VAS scores for each emotion were performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (SPSS v30). Effect sizes were calculated using the formula r = Z / √N [

48]. To assess the degree of association between general and climate-specific emotions, Spearman’s rank-order correlations were computed for each emotion. Statistical significance was set at α = .05, with Bonferroni correction applied to account for multiple comparisons across the four emotions. Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 28.0.

The 20 self-designed items on climate-related emotions were analysed using descriptive statistics (frequencies of responses: ‘(totally) agree,’ ‘neutral,’ and ‘(totally) disagree’) in SPSS v30. These results provided contextual information for interpreting the findings from the two open-ended questions on participants’ perceived emotional needs and barriers to pro-environmental behaviour, allowing climate-related emotions to be considered relative to broader emotional tendencies in the same sample.

Responses to the open-ended questions were exported from SPSS v28 to Microsoft Excel (MS Excel Professional Plus, 2021) by the first author. Descriptive statistics (frequencies) were first calculated for the fixed ‘not applicable’ response options (B and C,

Table 1). Open-text responses (A,

Table 1), for which participants could provide up to three answers, were organized in a separate Excel file. The first author then conducted a thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke [

49], coding the data and categorizing responses into overarching themes. To enhance the robustness of the analysis, the thematic coding was performed twice at separate time points. Responses deemed irrelevant or off topic were documented and grouped into a separate ‘irrelevant’ category.

3. Results

The sociodemographic details of the sample of Dutch young adults are published in full detail in Venhof et al. [

11]. In short, 1261 respondents were included, of which 32 provided no informed consent or were not living in the Netherlands, another 159 did not complete the questionnaire for unknown reasons, and another 64 were removed by an independent researcher from Flycatcher. The final dataset comprised of a national representative sample (age; gender; education level; province of residence) of 1,006 respondents. The average age was 25.9 [SD = 5.6]) years, with 51% women. More details of the sample can be found in Venhof et al. [

11].

Participants reported lower climate-specific anxiety (Median = 11, IQR = 3-37) than general anxiety (Median = 25, IQR = 10–51;

Z = –11.34,

p < .001,

r = –.36, indicating a moderate effect size [

48]. Similar patterns were observed for depressed mood (Median difference = 11;

Z = –16.04,

p < .001,

r = –.51, indicating a large effect size [

48]), and stress (Median difference = 20;

Z = –18.63,

p < .001,

r = –.59, reflecting a large effect size [

48]), loneliness (Median difference = 5;

Z = –13.50,

p < .001,

r = –.43, indicating a medium-to-large effect size [

48]).

Spearman’s rank-order correlations (rₛ) revealed significant positive associations between general and climate-related emotions, with moderate effect sizes for anxiety (rₛ= .39,

p < .001), depression (rₛ = .31,

p < .001), stress (rₛ= .26,

p < .001), and loneliness (rₛ= .35,

p < .001). These findings indicate that while related, climate-specific emotions are only moderately correlated with general emotional states, suggesting that climate-related emotional experiences represent a distinct but connected emotional domain. Detailed results for the four climate related anxiety, depression, stress and loneliness are presented in

Table 2.

Additional items assessed emotional responses to climate change using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘completely agree’ to 5 = ‘completely disagree’). Over half of the respondents (57%) expressed worry about the future of coming generations, such as their children, and 55% reported feeling sadness for people and animals affected by climate change. Approximately one third (31% and 35% for items 6 and 12, respectively; see

Table 2) reported feelings of powerlessness. Regarding responsibility, around 61% believed that large companies should do more to address climate change. Only 18% agreed with the statement that there is no more hope or that it is too late, while almost half (49.2%) disagreed, indicating that many still see reasons for hope.

In terms of pro-environmental behaviour, nearly half of the participants (46%) stated that they were already making changes to their lifestyle, and 36% felt they were personally doing enough. A smaller group (26%) believed they were not doing enough to live more sustainably. Additionally, 42% focused primarily on actions within their personal sphere of influence, and 23% reported confronting others about sustainable living. Only one fifth (~20%) found support on climate-related topics from peers or organisations, while about 26% tended to avoid the topic altogether and focused mainly on activities they enjoyed.

All 1,006 Dutch young adults responded to the two open-ended questions exploring their emotional needs related to climate change and their perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour. For the question on emotional needs, about two-thirds of the participants (673/1006) selected one of the fixed response categories (B/C). One third (31%, 307/1006) indicated that ‘nothing could make them feel better about climate change,’ while a similar proportion (36%, 366/1006) reported having ‘no feelings about climate change.’

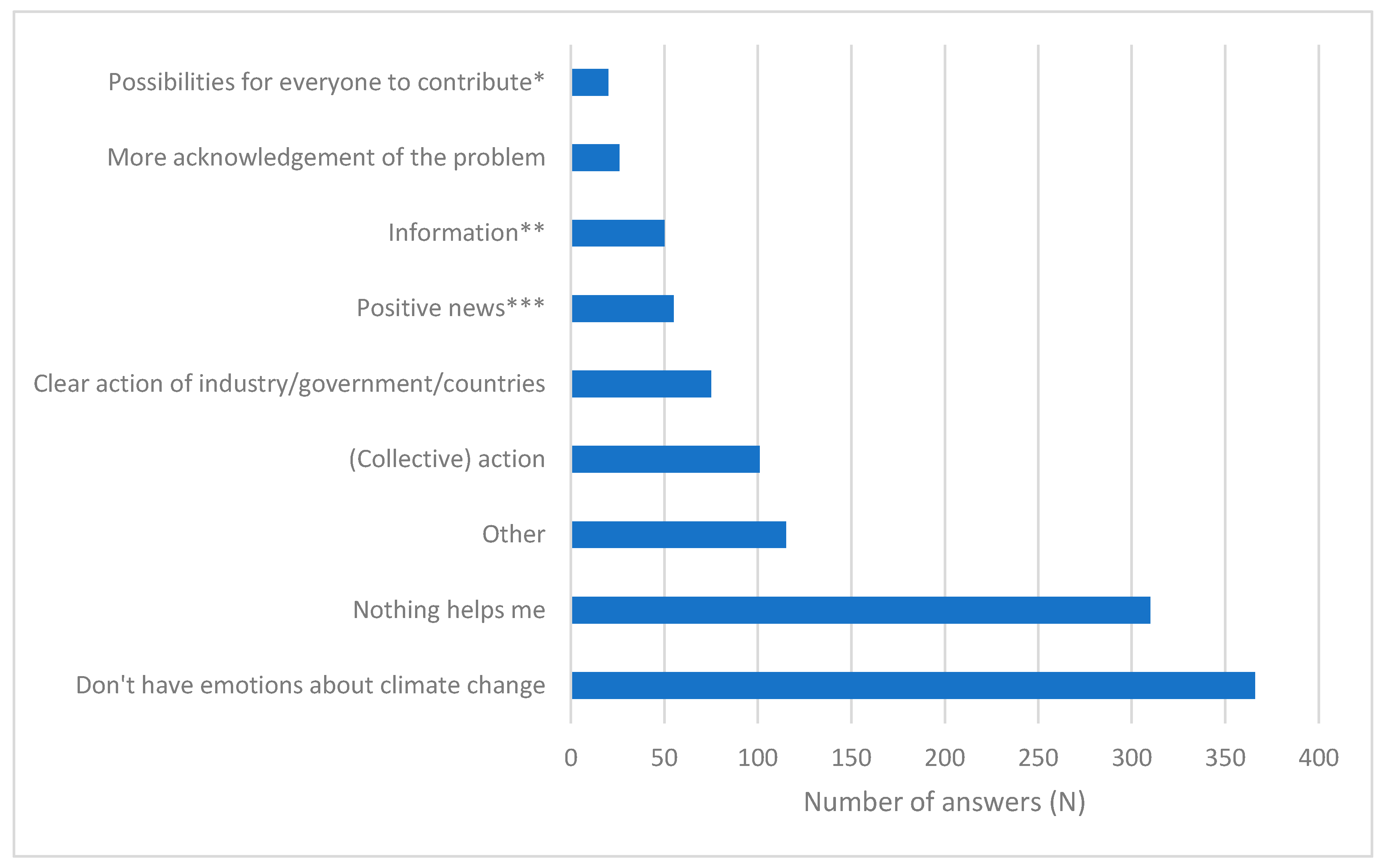

One third of respondents (33%, 333/1006) provided at least one open-ended response; 9% (88/1006) gave two answers, and 4% (38/1006) provided the maximum of three. Of the total 459 open responses, 13 were deemed irrelevant as they did not pertain to the question. Although the answers were highly diverse, several clear themes emerged (see

Figure 1).

A subset of young adults expressed a desire for more action at the personal and community level (10%, 101/1006), for example: ‘we have to start acting now, starting yesterday.’ Others emphasised the need for stronger action by industry, government, and/or other countries (8%, 75/1006), such as ‘I need action from the government, instead of words,’ ‘I need better decisions from the government, they make a mess of it,’ and ‘the big countries in the world need to act.’

Another group highlighted the need for accessible information, including reliable news and practical guidance (5%, 50/1006): ‘I need honest information” and ‘I need clear information on what I can do.’ A smaller group stressed the importance of broader societal acknowledgement of the problem (3%, 26/1006), with statements such as ‘our society should take the problem more seriously’ and ‘more people should become aware of it.’

Several participants expressed a wish for more positive news, focusing on improvements and progress (6%, 55/1006): ‘show us what works, positive stories,’ ‘more positive stories in the news, not only the negative,’ and ‘I need perspectives for the future.’ Finally, a small group (2%, 20/1006) indicated they needed ‘possibilities for everyone to contribute,’ for example through ‘a national plan in which civilians can also participate’ or ‘provide possibilities for individuals to do something.’

Not all answers could be categorised within these themes. A total of 115 responses were grouped into the category ‘other’ (see

Figure 1). Within this group, twelve participants mentioned the need for more insight into the impact of their own actions, and five indicated a desire for more conversations about the topic. Many responses concerned practical needs, such as

‘more electrical cars,’ ‘solar panels,’ ‘living more sustainably,’ financial support and subsidies (N = 22), or general

‘support’ (N = 6). A small number (N = 8) denied climate change altogether, stating it was

‘all exaggerated,’ ‘negativity,’ ‘just a natural phenomenon,’ or that we

‘should not make such a big problem of it.’ Another three participants responded that we should

‘just accept it.’

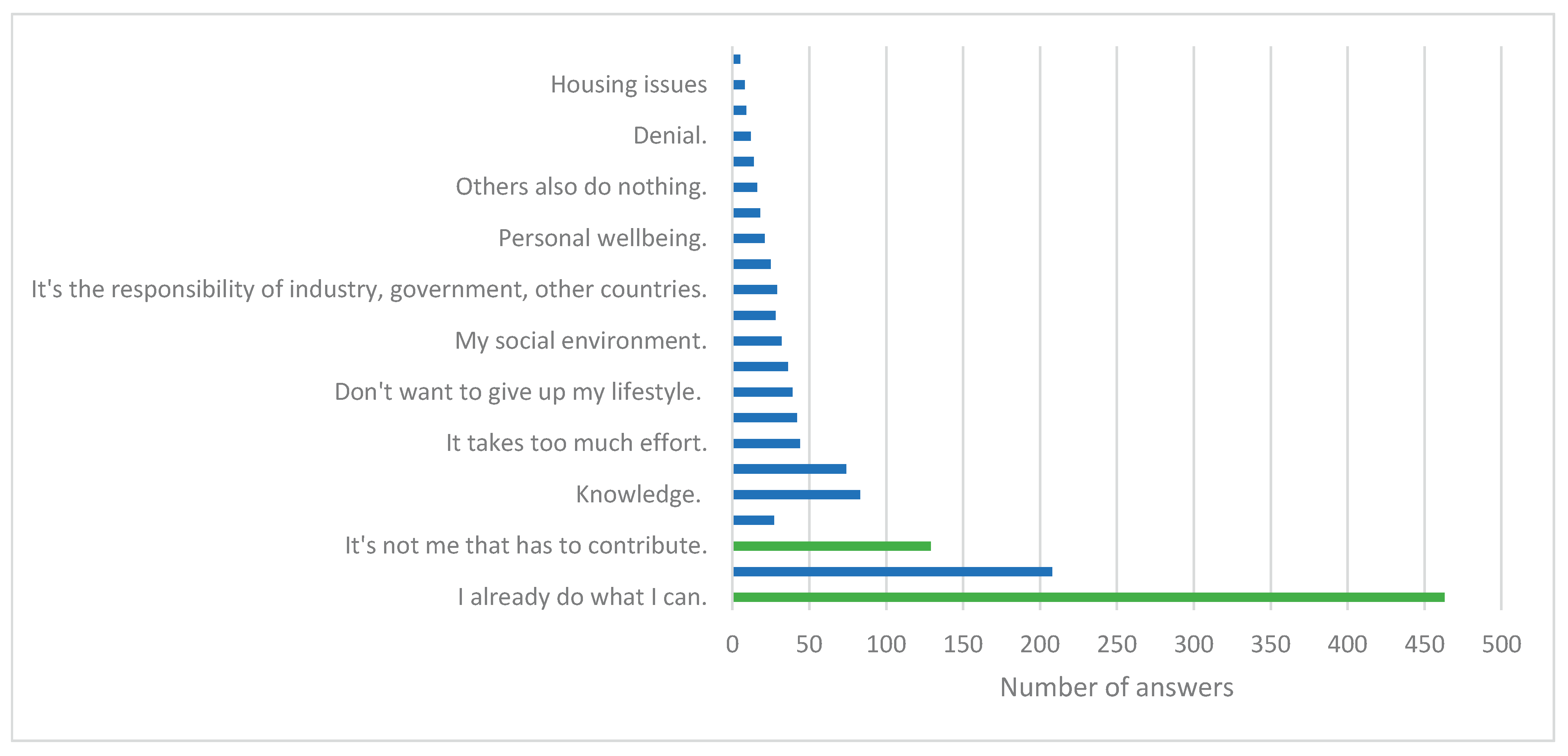

In response to the question on perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour, 42% of participants (426/1006) provided input in the open-text fields, while the majority (58%, 580/1006) selected from the fixed response categories (‘B’/‘C’). Among those who used the open-text option, many gave multiple responses: 26% of the total sample (257/1006) provided two answers, and 12% (125/1006) provided three answers. In total, 807 open responses were collected, of which approximately 7% (60/1006) were judged irrelevant. Most of these irrelevant responses were still related to pro-environmental behaviour, such as ‘flying less’ and ‘using less water’, but did not address the specific question of ‘what holds you back to live more sustainably’.

Nearly half of the participants stated that they

‘were already doing what they could’ (46%, 463/1006). One in eight (13%, 129/1006) indicated that they were not personally or individually responsible for acting more pro-environmentally. An additional 3% (29/1006) gave similar responses in the open-text fields, identifying others—such as industry, government, or other countries—as primarily responsible for sustainable action:

‘big companies need to act first’ and

‘the government needs to act’. In line with this, 4% (36/1006) argued that individual impact is very limited, for example:

‘one person has no influence’ and

‘I cannot change it as one individual’, with related themes including

‘I have no power/young people are not listened to’ (N = 14/1006) and

‘my age/I’m too young’ (N = 5/1006). All perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour are summarized in

Figure 2.

The most frequently mentioned barriers in the open-text fields concerned financial constraints (21%, 208/1006), with examples such as ‘alternatives such as the train are expensive’, ‘other choices cost a lot of money’, and ‘I have limited financial means’. Knowledge-related barriers were mentioned by 8% (83/1006), for example: ‘current information is contradictory’, ‘inconsistent’, or ‘I lack clear and consistent information on what I can do’. A lack of time was also frequently cited (7%, 74/1006), as in ‘I’m too busy with other things’ or ‘I’m too busy with my job’. Many respondents reported that suitable alternatives were lacking, of lower quality, or ‘less fun’ (~4%, N = 42/1006), or that pro-environmental behaviour required ‘too much effort’ (~4%, N = 44/1006).

Another important theme concerned behavioural change, reflected in statements such as ‘I don’t want to give up my (comfortable) lifestyle’ (N = 39), ‘taking the first step is difficult’ (N = 9), and ‘I have no motivation’ (N = 28). Other perceived barriers placed responsibility outside the individual, such as ‘others also do nothing’ (N = 16) and ‘my social environment’ (N = 32): ‘people in my social environment will see me in a negative way’, or ‘I live together with not like-minded people’.

Smaller themes related to personal wellbeing included answers such as ‘my physical wellbeing’, ‘my health’, ‘worries’, ‘stress’, ‘shame’, and ‘energy levels’ (N = 21); governmental decisions and ‘unclear’ regulations or politics (N = 18); denial (N = 12), such as ‘climate change is a lie’, ‘is it really as bad as they say’, and ‘it is a natural phenomenon’; and housing issues (N = 8), such as ‘I live too remote’ and ‘I live in an old property’. Additionally, some young adults (3%) stated that sustainable behaviour was ‘pointless’, indicating that ‘it has no use’ and ‘it is already too late’. Some answers could not be categorised within the above themes. The category ‘other’ (3%, 27/1006) included a variety of miscellaneous responses on perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour, such as ‘I’m not afraid', and ‘climate activists’.

4. Discussion

Across all four emotions (anxiety, depressed mood, stress, and loneliness), climate-related VAS scores were significantly lower than general emotional scores. Correlations between general and climate-specific emotions were significant but moderate (rₛ = .258–.389, all p < .001), indicating that while individuals with higher general emotional distress also tend to report stronger climate-related emotions, these emotions are not fully overlapping. This suggests that climate-related emotions represent a specific emotional domain within a broader emotional landscape, rather than merely reflecting general distress.

When asked more specifically about their emotional responses to climate change, 57% of the young adults expressed worry about the future of coming generations, such as their children, and 55% reported sadness for people and animals suffering because of climate change. Only 18% agreed with the statement that there is no more hope or that it is too late, whereas almost half (49.2%) disagreed, indirectly suggesting that they still hold hope for the future. Approximately one third of participants reported feelings of powerlessness. Regarding responsibility, around 61% believed that large companies should play a more active role in addressing climate change.

In terms of coping and behavioural responses, nearly half of the respondents (46%) reported already taking steps toward more sustainable lifestyles, with 42% focusing primarily on actions within their personal sphere of influence. A smaller group (26%) felt they were not doing enough to live more sustainably, whereas around 36% believed they were already doing enough. Notably, about one quarter (26%) reported avoiding the topic altogether, choosing instead to focus on activities they enjoyed.

These findings indicate a mix of emotional engagement, hope, perceived external responsibility, and varying degrees of personal action. To gain a deeper understanding of how young adults experience and navigate these emotions and behaviours in their daily lives, we analysed responses to two open-ended questions addressing (1) emotional needs in the context of climate change and (2) perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour. The open-ended questions were answered surprisingly well. The substantial number and diversity of responses demonstrate the participants’ strong engagement with the topics. Only a small proportion of answers was deemed irrelevant, suggesting that many participants had carefully reflected on the questions and provided thoughtful input.

One third of young adults (31%, 307/1006) indicated that nothing could make them feel better about climate change and related issues. Although further research is needed, this response pattern may reflect a form of despair, or emotional distancing as a defensive coping strategy to avoid overwhelming emotions [

50,

51,

52]. Another third (36%) reported having no particular feelings about these problems. Rather than simple indifference, this may also reflect emotional numbing or avoidance—a way to protect oneself from the distress associated with climate change [

7,

51]. About 10% expressed a need for more action at the personal and community levels, and 8% called for greater efforts from industry, government, or other countries.

When exploring the perceived barriers to engaging in more pro-environmental behaviour among Dutch young adults, several broader themes emerged (see

Figure 2). First, a large proportion of respondents indicated

structural and systemic barriers. Financial constraints were most frequently mentioned, with 21% (208/1006) reporting lack of money as a key obstacle. Other structural factors included lack of appealing or accessible alternatives (4%), housing issues (1%), and governmental decisions and politics (2%). Additionally, 13% (129/1006) felt that addressing climate change was ‘not their responsibility,’ while 3% (29/1006) explicitly identified industry, government, or other countries as primarily responsible. These responses suggest that many young adults perceive meaningful climate action as dependent on systemic changes rather than individual effort, consistent with research on structural responsibility and perceived behavioural efficacy (e.g., [

51,

52]).

Second,

psychological and motivational barriers formed a substantial cluster. These included a sense of having already done enough (46%, 463/1006), low motivation or interest (3%), feelings of hopelessness (‘it’s too late’, 3%), denial (1%), perceived limited impact of individual actions (4%), and reluctance to give up one’s lifestyle (4%). A smaller number referred to social comparison and perceived inaction by others (2%), or a lack of power and voice (1%). These barriers reflect emotional distancing, defensive coping, and perceived inefficacy, which have been described in the literature as common responses to climate anxiety and perceived threat (e.g., [

42,

53]).

A third group of barriers related to practical and knowledge-based obstacles, including lack of knowledge (8%), time constraints (7%), and perceptions that pro-environmental behaviour requires too much effort (4%) or that taking the first step is difficult (1%). These are more logistical in nature and may be more amenable to targeted interventions such as clear information, education, and practical support. Finally, social and personal factors also played a role. Barriers related to the social environment were mentioned by 3% of respondents, while 2% referred to personal wellbeing factors such as health, stress, or low energy levels. These findings underscore the importance of considering both social norms and individual capacities in climate engagement.

Taken together, the findings show that young adults face a complex mix of structural, psychological, practical, social, and personal barriers. Interventions to promote sustainable behaviour will likely need to address both systemic conditions and individual agency and consider emotional as well as practical dimensions of behavioural change.

It is widely acknowledged that empowering youth to reduce energy use requires a combination of education, incentives (financial and structural support), and enabling infrastructure [

50,

54,

55]. Our findings align with previous research demonstrating that financial costs remain a key barrier to sustainable consumption among motivated young adults [

56]. This suggests opportunities to encourage reduced consumption of items like clothing and air travel, and to promote experiences instead—thereby helping youth save money and improve well-being and security [

57,

58]. However, adolescence and early adulthood are life stages characterized by pro-consumption behaviours tied to identity formation through belongings, fashion, and gadgets [

59]. Hence, investments in information and education remain crucial—such as clear communication about recycling rules, awareness of greenwashing in clothing, and guidance on sustainable diet choices (e.g., reducing meat and dairy consumption), which are among the most impactful behaviours. Infrastructure improvements—from recycling bins to accessible public transport and safe cycling networks—are equally important, as are policies that make sustainable choices the convenient ones [

60].

More research is needed on so-called ‘bottleneck’ behaviours, where young people experience cognitive dissonance by recognizing the negative impact of flying or eating meat but feeling unable or unwilling to change these habits [12 (under review), 20,22]. Dutch studies indicate that social strategies like vegan tasting sessions, peer cooking demonstrations, and linking diet to personal health and fitness may help facilitate dietary shifts among youth [

61]. Similarly, social media influencers and trends can motivate sustainable behaviour, from diet to energy-saving and alternative travel options, potentially helping youth reduce costs (compared to fast-fashion promotion on social media). The fact that half of our participants already feel they do what they can raises concerns about “tokenism”—the phenomenon where people perform a few obvious actions (like turning off taps or lights) and then consider their responsibility fulfilled [

28]. This mindset can hinder further actions such as unplugging idle electronics, air-drying clothes, or buying sustainable clothing. The perception that ‘my effort is too small to matter’ may discourage further action, suggesting that society should foster sustainable community norms, personal incentives (e.g., cost savings), and ease of use through technologies like smart thermostats, motion-sensor lighting, solar panels, and accessible second-hand clothing exchange.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Although this study was exploratory and on the qualitative side limited by only including two open-ended questions, a key strength lies in the fact that all 1006 participants from a representative sample responded. Most engaged thoughtfully and seriously, with many (33%) providing at least one open-ended response. This level of engagement enriches the findings and provides valuable insights into young adults’ perspectives.

A limitation of this study is the use of a sliding visual analogue scale (0–100) to assess emotional responses. Prior research indicates that VAS scores tend to produce lower means and greater variability compared to Likert scales, potentially affecting the comparability and interpretation of absolute emotional intensity scores. At the same time, the use of a continuous VAS allowed for more fine-grained measurement of emotional intensity, which may capture subtle variations that ordinal Likert scales could miss.

A notable limitation is the inclusion of two fixed-answer options alongside the open-ended questions. Positioned at the end of a longer questionnaire, respondents may have chosen these fixed options for convenience rather than investing time in open-ended answers, potentially leading to rushed or less thoughtful responses. Additionally, the second question was negatively framed, assuming respondents experienced environmental distress and negative emotions, which may have biased answers. These factors highlight potential data biases and underscore the need for further research using more balanced question formats and response options.

Although the open-ended questions were not the main focus of our study, placing these responses in the context of the findings from the fixed-response questions can provide valuable inspiration for future qualitative research on perceived barriers and needs in environmental care among young adults. The willingness of many participants to respond despite survey length suggests that environmental change is an important issue to them. Overall, the results show that while many Dutch young adults recognize the importance of sustainable behaviour, significant barriers such as financial constraints, limited knowledge, and time impede their actions.

4.2. Practical Implications

This study offers exploratory insights into the emotional landscape surrounding climate change and the perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour among young adults. While the sample was representative and response rates were good, the study design does not allow for causal interpretations or broad generalisations. Future research could build on these findings by using longitudinal and experimental designs to examine how emotional needs and perceived barriers interact over time and influence behavioural intentions and actions. Moreover, qualitative studies could provide a deeper understanding of the lived emotional experiences and contextual factors that underlie these patterns. More research is also needed to explore more deeply how and in which strength environmental change contributes to the general wellbeing of youth and young adults. Young people are facing a complex mixture of worries and anxieties, also in the Dutch context, on housing problems, social difficulties, and financial constraints (e.g., [

10]). Expanding research to larger and more diverse populations, including international samples or more diverse in education and resources, would also strengthen the evidence base and support the development of targeted interventions.

4.3. Conclusion

This exploratory study examined emotional responses to climate change and perceived barriers to pro-environmental behaviour among a representative sample of 1,006 Dutch young adults (aged 16–35). Although the study was small and explorative in nature, its strength lies in the size and representativeness of the sample, as well as in the thoughtful and extensive responses provided by participants. This indicates both engagement and, for many, a willingness to contribute. The findings reveal a complex emotional landscape in which feelings of worry, frustration, and powerlessness coexist with hope and a generally constructive outlook. Only a small proportion expressed fatalistic views, while for some the issue appeared emotionally distant or was downplayed. Emotional needs were highly diverse and often practical in nature, relating to financial constraints, lack of time, knowledge gaps, or insufficient alternatives. Many participants also located responsibility outside the individual, placing it with governments, large companies, and other countries. Many young adults appeared to be searching for ways to balance environmental action with everyday life and are looking for feasible pathways to contribute.

These findings suggest that efforts to promote pro-environmental behaviour should involve young people more actively, highlight positive and hopeful narratives, and combine emotional engagement with the removal of structural and perceived barriers. Interventions should go beyond information provision or financial incentives and address emotional dimensions and perceived agency. Communication strategies and policies that validate emotional experiences while simultaneously lowering practical and psychological barriers may be more effective in fostering sustained behavioural change. However, given the exploratory nature of this study, these implications should be interpreted with caution and further examined in larger and more robust research.