Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

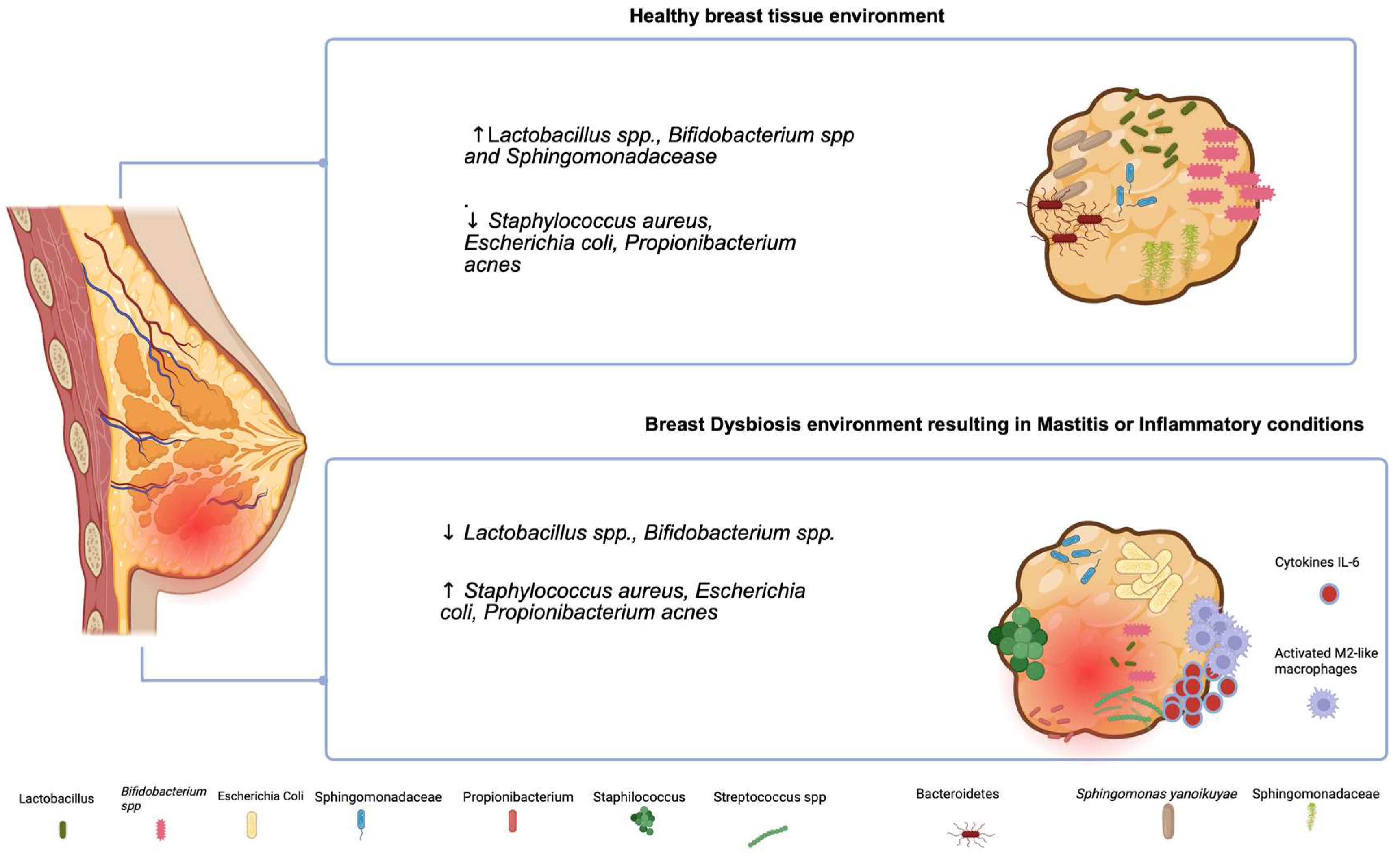

2. Microbiota in Breast Feeding in Healthy and Inflammatory Conditions

2. Molecular Alterations in Breast Cancer

3. The Microbiota in Breast Cancer

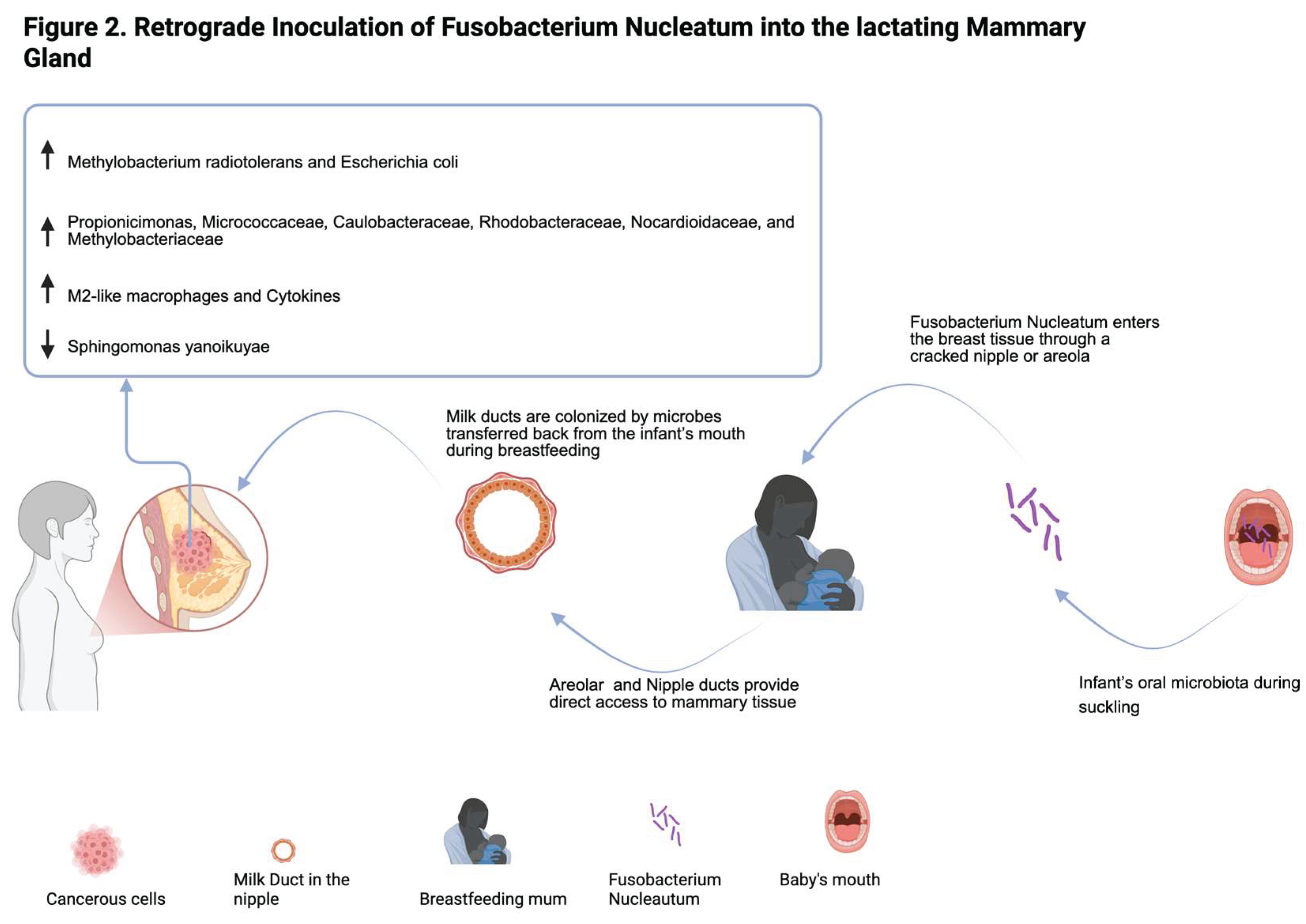

4. Fusobacterium Nucleatum and Its Onco-Immunomodulatory Role in Breast Cancer

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xuan, C., et al., Microbial dysbiosis is associated with human breast cancer. PLoS One, 2014. 9(1): p. e83744.

- Urbaniak, C., et al., Microbiota of human breast tissue. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014. 80(10): p. 3007-14. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, H., et al., Resident bacteria in breast cancer tissue: pathogenic agents or harmless commensals? Discov Med, 2018. 26(142): p. 93-102.

- Urbaniak, C., et al., The Microbiota of Breast Tissue and Its Association with Breast Cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2016. 82(16): p. 5039-48.

- Fernandez, L., et al., The human milk microbiota: origin and potential roles in health and disease. Pharmacol Res, 2013. 69(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., et al., Distinct microbial communities that differ by race, stage, or breast-tumor subtype in breast tissues of non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 11940.

- Yatsunenko, T., et al., Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature, 2012. 486(7402): p. 222-7. [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, A., et al., Human breast microbiome correlates with prognostic features and immunological signatures in breast cancer. Genome Med, 2021. 13(1): p. 60. [CrossRef]

- Hieken, T.J., et al., The Microbiome of Aseptically Collected Human Breast Tissue in Benign and Malignant Disease. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 30751.

- Fitzstevens, J.L., et al., Systematic Review of the Human Milk Microbiota. Nutr Clin Pract, 2017. 32(3): p. 354-364. [CrossRef]

- Pannaraj, P.S., et al., Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome. JAMA Pediatr, 2017. 171(7): p. 647-654. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gallego, C., et al., The human milk microbiome and factors influencing its composition and activity. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 2016. 21(6): p. 400-405. [CrossRef]

- Milani, C., et al., The First Microbial Colonizers of the Human Gut: Composition, Activities, and Health Implications of the Infant Gut Microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 2017. 81(4). [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.L., et al., Human milk metagenome: a functional capacity analysis. BMC Microbiol, 2013. 13: p. 116. [CrossRef]

- Makino, H., et al., Transmission of intestinal Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strains from mother to infant, determined by multilocus sequencing typing and amplified fragment length polymorphism. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2011. 77(19): p. 6788-93. [CrossRef]

- Boix-Amoros, A., M.C. Collado, and A. Mira, Relationship between Milk Microbiota, Bacterial Load, Macronutrients, and Human Cells during Lactation. Front Microbiol, 2016. 7: p. 492.

- Rodriguez, J.M., The origin of human milk bacteria: is there a bacterial entero-mammary pathway during late pregnancy and lactation? Adv Nutr, 2014. 5(6): p. 779-84. [CrossRef]

- Enaud, R., et al., The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2020. 10: p. 9. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, P., et al., Mother-to-Infant Microbial Transmission from Different Body Sites Shapes the Developing Infant Gut Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe, 2018. 24(1): p. 133-145 e5. [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.C., et al., The intestinal microbiome in early life: health and disease. Front Immunol, 2014. 5: p. 427. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rubio, R., et al., The human milk microbiome changes over lactation and is shaped by maternal weight and mode of delivery. Am J Clin Nutr, 2012. 96(3): p. 544-51. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H., et al., Molecular monitoring of the development of intestinal microbiota in Japanese infants. Benef Microbes, 2012. 3(2): p. 113-25. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H., et al., Distinct Patterns in Human Milk Microbiota and Fatty Acid Profiles Across Specific Geographic Locations. Front Microbiol, 2016. 7: p. 1619. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J., L. Fontana, and A. Gil, Human Milk Oligosaccharides and Immune System Development. Nutrients, 2018. 10(8). [CrossRef]

- Kirmiz, N., et al., Milk Glycans and Their Interaction with the Infant-Gut Microbiota. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol, 2018. 9: p. 429-450. [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.B., et al., Infant gut microbiota and food sensitization: associations in the first year of life. Clin Exp Allergy, 2015. 45(3): p. 632-43. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, E., et al., Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section. Curr Microbiol, 2005. 51(4): p. 270-4. [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C., et al., Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 23129. [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.C., et al., Gut microbiome in the first 1000 days and risk for childhood food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2024. 133(3): p. 252-261. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.D., et al., A comparative study of the gut microbiota in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases-does a common dysbiosis exist? Microbiome, 2018. 6(1): p. 221. [CrossRef]

- Moossavi, S., et al., Composition and Variation of the Human Milk Microbiota Are Influenced by Maternal and Early-Life Factors. Cell Host Microbe, 2019. 25(2): p. 324-335 e4. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.M., L. Fernandez, and V. Verhasselt, The Gut‒Breast Axis: Programming Health for Life. Nutrients, 2021. 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Sung, H., et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021. 71(3): p. 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Friebel, T.M., S.M. Domchek, and T.R. Rebbeck, Modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2014. 106(6): p. dju091. [CrossRef]

- Mavaddat, N., et al., Distribution of age at natural menopause, age at menarche, menstrual cycle length, height and BMI in BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers and non-carriers: results from EMBRACE. Breast Cancer Res, 2025. 27(1): p. 87. [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.M., et al., Germline TP53 mutation spectrum in Sudanese premenopausal breast cancer patients: correlations with reproductive factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2019. 175(2): p. 479-485. [CrossRef]

- Loibl, S., et al., Breast cancer. Lancet, 2021. 397(10286): p. 1750-1769.

- Toss, A. and M. Cristofanilli, Molecular characterization and targeted therapeutic approaches in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res, 2015. 17(1): p. 60. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X., et al., Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2025. 10(1): p. 49.

- Rebbeck, T.R., et al., Mutational spectrum in a worldwide study of 29,700 families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Hum Mutat, 2018. 39(5): p. 593-620. [CrossRef]

- Veschi, S., et al., High prevalence of BRCA1 deletions in BRCAPRO-positive patients with high carrier probability. Ann Oncol, 2007. 18 Suppl 6: p. vi86-92. [CrossRef]

- Newman, L., US Preventive Services Task Force Breast Cancer Recommendation Statement on Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer. JAMA Surg, 2019. 154(10): p. 895-896. [CrossRef]

- Anaclerio, F., et al., Clinical usefulness of NGS multi-gene panel testing in hereditary cancer analysis. Front Genet, 2023. 14: p. 1060504. [CrossRef]

- Rizzolo, P., et al., Contribution of MUTYH Variants to Male Breast Cancer Risk: Results From a Multicenter Study in Italy. Front Oncol, 2018. 8: p. 583. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Association Between Polymorphisms in DNA Damage Repair Pathway Genes and Female Breast Cancer Risk. DNA Cell Biol, 2024. 43(5): p. 219-231. [CrossRef]

- Bouras, E., et al., Circulating inflammatory cytokines and risk of five cancers: a Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Med, 2022. 20(1): p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Moscatello, C., et al., Relationship between MUTYH, OGG1 and BRCA1 mutations and mRNA expression in breast and ovarian cancer predisposition. Mol Clin Oncol, 2021. 14(1): p. 15.

- Donovan, M.G., et al., Dietary fat and obesity as modulators of breast cancer risk: Focus on DNA methylation. Br J Pharmacol, 2020. 177(6): p. 1331-1350. [CrossRef]

- Ming, R., et al., Causal effects and metabolites mediators between immune cell and risk of breast cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Genet, 2024. 15: p. 1380249. [CrossRef]

- Davies, H., et al., HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat Med, 2017. 23(4): p. 517-525. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, N., et al., Homologous recombination DNA repair deficiency and PARP inhibition activity in primary triple negative breast cancer. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 2662. [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B., et al., Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA, 2017. 317(23): p. 2402-2416.

- Kim, J. and P.N. Munster, Estrogens and breast cancer. Ann Oncol, 2025. 36(2): p. 134-148.

- Sorlie, T., et al., Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2001. 98(19): p. 10869-74. [CrossRef]

- Goldhirsch, A., et al., Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol, 2013. 24(9): p. 2206-23. [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.H., et al., The 2019 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology, 2020. 77(2): p. 181-185. [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, M., et al., Results of a worldwide survey on the currently used histopathological diagnostic criteria for invasive lobular breast cancer. Mod Pathol, 2022. 35(12): p. 1812-1820.

- Risom, T., et al., Transition to invasive breast cancer is associated with progressive changes in the structure and composition of tumor stroma. Cell, 2022. 185(2): p. 299-310 e18.

- Yersal, O. and S. Barutca, Biological subtypes of breast cancer: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. World J Clin Oncol, 2014. 5(3): p. 412-24. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.K., et al., Impact of Molecular Subtype Conversion of Breast Cancers after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy on Clinical Outcome. Cancer Res Treat, 2016. 48(1): p. 133-41. [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M., et al., Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 2000. 406(6797): p. 747-52. [CrossRef]

- Fico, F. and A. Santamaria-Martinez, The Tumor Microenvironment as a Driving Force of Breast Cancer Stem Cell Plasticity. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T., S. Vinayak, and M. Telli, Emerging strategies: PARP inhibitors in combination with immune checkpoint blockade in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation-associated and triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2023. 197(1): p. 51-56. [CrossRef]

- Bottosso, M., et al., Moving toward precision medicine to predict drug sensitivity in patients with metastatic breast cancer. ESMO Open, 2024. 9(3): p. 102247. [CrossRef]

- Lukasiewicz, S., et al., Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated Review. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(17).

- Rossing, M., et al., Clinical implications of intrinsic molecular subtypes of breast cancer for sentinel node status. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 2259. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., et al., The prognostic role of lymph node ratio in breast cancer patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A dose-response meta-analysis. Front Surg, 2022. 9: p. 971030. [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.J., et al., Cancer cell plasticity and MHC-II-mediated immune tolerance promote breast cancer metastasis to lymph nodes. J Exp Med, 2023. 220(9). [CrossRef]

- Reticker-Flynn, N.E., et al., Lymph node colonization induces tumor-immune tolerance to promote distant metastasis. Cell, 2022. 185(11): p. 1924-1942 e23. [CrossRef]

- Si, H., et al., The covert symphony: cellular and molecular accomplices in breast cancer metastasis. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2023. 11: p. 1221784. [CrossRef]

- Terry, M.B., et al., Environmental exposures during windows of susceptibility for breast cancer: a framework for prevention research. Breast Cancer Res, 2019. 21(1): p. 96. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, A.A., et al., Diet Modulates the Gut Microbiome, Metabolism, and Mammary Gland Inflammation to Influence Breast Cancer Risk. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 2024. 17(9): p. 415-428. [CrossRef]

- Alpuim Costa, D., et al., Human Microbiota and Breast Cancer-Is There Any Relevant Link?-A Literature Review and New Horizons Toward Personalised Medicine. Front Microbiol, 2021. 12: p. 584332. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., et al., Gut microbial beta-glucuronidase: a vital regulator in female estrogen metabolism. Gut Microbes, 2023. 15(1): p. 2236749. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, A.A. and K.L. Cook, Gut and Breast Microbiota as Endocrine Regulators of Hormone Receptor-positive Breast Cancer Risk and Therapy Response. Endocrinology, 2022. 164(1). [CrossRef]

- Menon, G., F.M. Alkabban, and T. Ferguson, Breast Cancer, in StatPearls. 2025: Treasure Island (FL).

- Dethlefsen, L., M. McFall-Ngai, and D.A. Relman, An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature, 2007. 449(7164): p. 811-8. [CrossRef]

- Willing, B.P., S.L. Russell, and B.B. Finlay, Shifting the balance: antibiotic effects on host-microbiota mutualism. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2011. 9(4): p. 233-43.

- Arendt, L.M., et al., Obesity promotes breast cancer by CCL2-mediated macrophage recruitment and angiogenesis. Cancer Res, 2013. 73(19): p. 6080-93.

- Buchta Rosean, C., et al., Preexisting Commensal Dysbiosis Is a Host-Intrinsic Regulator of Tissue Inflammation and Tumor Cell Dissemination in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res, 2019. 79(14): p. 3662-3675. [CrossRef]

- Nejman, D., et al., The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science, 2020. 368(6494): p. 973-980. [CrossRef]

- Human Microbiome Project, C., Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature, 2012. 486(7402): p. 207-14.

- Costello, E.K., et al., Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science, 2009. 326(5960): p. 1694-7. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z., et al., New Developments and Opportunities of Microbiota in Treating Breast Cancers. Front Microbiol, 2022. 13: p. 818793.

- Davis, C.P., et al., Urothelial hyperplasia and neoplasia. III. Detection of nitrosamine production with different bacterial genera in chronic urinary tract infections of rats. J Urol, 1991. 145(4): p. 875-80. [CrossRef]

- Costantini, L., et al., Characterization of human breast tissue microbiota from core needle biopsies through the analysis of multi hypervariable 16S-rRNA gene regions. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 16893. [CrossRef]

- Thu, M.S., et al., Human gut, breast, and oral microbiome in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol, 2023. 13: p. 1144021.

- Wang, H., et al., The microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide promotes antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Metab, 2022. 34(4): p. 581-594 e8. [CrossRef]

- Hix, L.M., et al., CD1d-expressing breast cancer cells modulate NKT cell-mediated antitumor immunity in a murine model of breast cancer metastasis. PLoS One, 2011. 6(6): p. e20702.

- Rea, D., et al., Microbiota effects on cancer: from risks to therapies. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(25): p. 17915-17927. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Breast tissue, oral and urinary microbiomes in breast cancer. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(50): p. 88122-88138. [CrossRef]

- Kwa, M., et al., The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2016. 108(8).

- Adlercreutz, H. and F. Martin, Biliary excretion and intestinal metabolism of progesterone and estrogens in man. J Steroid Biochem, 1980. 13(2): p. 231-44. [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, B.J., et al., Associations of the fecal microbiome with urinary estrogens and estrogen metabolites in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014. 99(12): p. 4632-40. [CrossRef]

- Plottel, C.S. and M.J. Blaser, Microbiome and malignancy. Cell Host Microbe, 2011. 10(4): p. 324-35. [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, D.L., et al., The Oncobiome in Gastroenteric and Genitourinary Cancers. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(17). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., et al., Gastrointestinal microbiome and breast cancer: correlations, mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Breast Cancer, 2017. 24(2): p. 220-228. [CrossRef]

- Dabek, M., et al., Distribution of beta-glucosidase and beta-glucuronidase activity and of beta-glucuronidase gene gus in human colonic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 2008. 66(3): p. 487-95.

- Goedert, J.J., et al., Postmenopausal breast cancer and oestrogen associations with the IgA-coated and IgA-noncoated faecal microbiota. Br J Cancer, 2018. 118(4): p. 471-479. [CrossRef]

- Goedert, J.J., et al., Investigation of the association between the fecal microbiota and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: a population-based case-control pilot study. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2015. 107(8). [CrossRef]

- Backhed, F., et al., The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(44): p. 15718-23. [CrossRef]

- Koller, V.J., et al., Impact of lactic acid bacteria on oxidative DNA damage in human derived colon cells. Food Chem Toxicol, 2008. 46(4): p. 1221-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Y. Xia, and J. Sun, Breast and gut microbiome in health and cancer. Genes Dis, 2021. 8(5): p. 581-589. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.J., et al., A comprehensive analysis of breast cancer microbiota and host gene expression. PLoS One, 2017. 12(11): p. e0188873.

- Wolfe, A.J., et al., Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol, 2012. 50(4): p. 1376-83. [CrossRef]

- Hummelen, R., et al., Deep sequencing of the vaginal microbiota of women with HIV. PLoS One, 2010. 5(8): p. e12078. [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A., et al., Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science, 2009. 324(5931): p. 1190-2. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., et al., Distinct Microbial Signatures Associated With Different Breast Cancer Types. Front Microbiol, 2018. 9: p. 951.

- Banerjee, S., et al., Distinct microbiological signatures associated with triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 15162.

- Gaba, F.I., R.C. Gonzalez, and R.G. Martinez, The Role of Oral Fusobacterium nucleatum in Female Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Dent, 2022. 2022: p. 1876275. [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.Q., et al., Facultative or obligate anaerobic bacteria have the potential for multimodality therapy of solid tumours. Eur J Cancer, 2007. 43(3): p. 490-6. [CrossRef]

- Saygun, I., et al., Salivary infectious agents and periodontal disease status. J Periodontal Res, 2011. 46(2): p. 235-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., et al., Detection of fusobacterium nucleatum and fadA adhesin gene in patients with orthodontic gingivitis and non-orthodontic periodontal inflammation. PLoS One, 2014. 9(1): p. e85280. [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.Y., et al., Progression of periodontal inflammation in adolescents is associated with increased number of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythensis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Int J Paediatr Dent, 2014. 24(3): p. 226-33.

- Han, Y.W., et al., Term stillbirth caused by oral Fusobacterium nucleatum. Obstet Gynecol, 2010. 115(2 Pt 2): p. 442-445. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S., et al., The origin of Fusobacterium nucleatum involved in intra-amniotic infection and preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2011. 24(11): p. 1329-32.

- Barak, S., et al., Evidence of periopathogenic microorganisms in placentas of women with preeclampsia. J Periodontol, 2007. 78(4): p. 670-6. [CrossRef]

- Temoin, S., et al., Identification of oral bacterial DNA in synovial fluid of patients with arthritis with native and failed prosthetic joints. J Clin Rheumatol, 2012. 18(3): p. 117-21. [CrossRef]

- Tahara, T., et al., Fusobacterium detected in colonic biopsy and clinicopathological features of ulcerative colitis in Japan. Dig Dis Sci, 2015. 60(1): p. 205-10. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J., et al., Invasive potential of gut mucosa-derived Fusobacterium nucleatum positively correlates with IBD status of the host. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2011. 17(9): p. 1971-8. [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/beta-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe, 2013. 14(2): p. 195-206. [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer by inducing Wnt/beta-catenin modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Rep, 2019. 20(4).

- Castellarin, M., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res, 2012. 22(2): p. 299-306. [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D., et al., Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res, 2012. 22(2): p. 292-8. [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P., et al., The Potential of Colonic Tumor Tissue Fusobacterium nucleatum to Predict Staging and Its Interplay with Oral Abundance in Colon Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P., et al., The Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Oral and Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms, 2023. 11(9). [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, D.L., et al., Intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum in Pancreatic Cancer: Current and Future Perspectives. Pathogens, 2024. 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M., et al., Intratumor Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes the progression of pancreatic cancer via the CXCL1-CXCR2 axis. Cancer Sci, 2023. 114(9): p. 3666-3678. [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, K., et al., Human Microbiome Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Esophageal Cancer Tissue Is Associated with Prognosis. Clin Cancer Res, 2016. 22(22): p. 5574-5581. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.D., et al., Salivary Fusobacterium nucleatum serves as a potential diagnostic biomarker for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol, 2022. 28(30): p. 4120-4132. [CrossRef]

- Audirac-Chalifour, A., et al., Cervical Microbiome and Cytokine Profile at Various Stages of Cervical Cancer: A Pilot Study. PLoS One, 2016. 11(4): p. e0153274. [CrossRef]

- Parhi, L., et al., Breast cancer colonization by Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates tumor growth and metastatic progression. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 3259.

- Abed, J., et al., Fap2 Mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Enrichment by Binding to Tumor-Expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe, 2016. 20(2): p. 215-25. [CrossRef]

- Fardini, Y., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum adhesin FadA binds vascular endothelial cadherin and alters endothelial integrity. Mol Microbiol, 2011. 82(6): p. 1468-80. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum and its associated systemic diseases: epidemiologic studies and possible mechanisms. J Oral Microbiol, 2023. 15(1): p. 2145729. [CrossRef]

- Kolbl, A.C., et al., The role of TF- and Tn-antigens in breast cancer metastasis. Histol Histopathol, 2016. 31(6): p. 613-21.

- Abed, J., et al., Tumor Targeting by Fusobacterium nucleatum: A Pilot Study and Future Perspectives. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2017. 7: p. 295. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., K. Yu, and R. Huang, The ways Fusobacterium nucleatum translocate to breast tissue and contribute to breast cancer development. Mol Oral Microbiol, 2024. 39(1): p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mehner, C., et al., Tumor cell-produced matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) drives malignant progression and metastasis of basal-like triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget, 2014. 5(9): p. 2736-49. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes PD-L1 expression in cancer cells to evade CD8(+) T cell killing in breast cancer. Hum Immunol, 2024. 85(6): p. 111168. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., et al., Intratumoral microbiome: implications for immune modulation and innovative therapeutic strategies in cancer. J Biomed Sci, 2025. 32(1): p. 23. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., Invasive Fusobacterium nucleatum activates beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer via a TLR4/P-PAK1 cascade. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(19): p. 31802-31814. [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, M., et al., The onco-immunological implications of Fusobacterium nucleatum in breast cancer. Immunol Lett, 2021. 232: p. 60-66.

- Gur, C., et al., Fusobacterium nucleatum supresses anti-tumor immunity by activating CEACAM1. Oncoimmunology, 2019. 8(6): p. e1581531. [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.C., et al., MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science, 2016. 352(6282): p. 227-31. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J., et al., Prognostic value of immune checkpoint molecules in breast cancer. Biosci Rep, 2020. 40(7). [CrossRef]

- Mollavelioglu, B., et al., High co-expression of immune checkpoint receptors PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in early-stage breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol, 2022. 20(1): p. 349. [CrossRef]

- Matlung, H.L., et al., The CD47-SIRPalpha signaling axis as an innate immune checkpoint in cancer. Immunol Rev, 2017. 276(1): p. 145-164.

- Han, Y., D. Liu, and L. Li, PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: current researches in cancer. Am J Cancer Res, 2020. 10(3): p. 727-742.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).