1. Introduction

As sessile organism, plants develop corresponding survival strategies to maximize adaptation to the environment through continuous evolution (Boyko et al., 2023), and their trait variation plays an important role in species evolution and maintenance of biodiversity (Liu et al., 2024). However, since the industrial revolution, global climate change and human activities have strongly altered the environment and the increasing temperature and drought events has posed a serious threat to plant growth (Field et al., 2016; van Oldenborgh et al., 2021). Currently, plants have to migrate northward to find suitable habitat (Boisvert-Marsh and de Blois, 2021), but studies have shown that plants migrate northward at a slower rate than climate change due to the long budding mating period and landscape fragmentation (Ash et al., 2017; Alexander et al., 2018). Thus, studying the adaptation mechanism of plants to climate change in situ is of great significance for maintaining the structural and functional stability of forest ecosystems.

Plants adaptation is the result of plant-environment interactions, and it respond to environmental changes mainly through two mechanisms: genetic variation or phenotypic plasticity (Murren et al., 2015; Fox et al., 2019), whereas phenotypic plasticity has a faster response time in the face of variable or deleterious environmental conditions compared to genetic adaptation (Pigliucci et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2019), which can help plants to flexibly cope with a variety of environmental changes (Gratani, 2014). Phenotypic plasticity is prevalent in plants and is the basis for optimal adaptation in the face of fluctuating environmental conditions or exposure to transient deleterious conditions (Schlichting, 1986; Fritz et al., 2018). Plants can adjust their morphology, physiology, and reproduction to enhance adaptability through phenotypic plasticity in order to optimize their resource use strategies under various environmental conditions (Liu et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020). However, the plant is extremely sensitive to changes in the environment, and in order to maintain the high phenotypic plasticity to the environmental changes, plants need to put additional energy at the cost of growth and defensive function (Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important to understand the role of phenotypical plasticity in regulating plant response to environment.

Plant functional traits are specific manifestations of plant adaptation to external conditions and serve as a bridge between the environment, individual plants, and broader ecological processes and functions (van der Merwe et al., 2021), and their intraspecific spatial variability and phenotypic plasticity can help predict species distribution under global climate change (Ren et al., 2020). Variation in functional traits provides good adaptive strategies for plants to cope with environmental changes (Liu et al., 2020). Some of these functional traits reflect core aspects of plant ecological strategies and may therefore be relevant to plant phenotypic plasticity (Stotz et al., 2022). For example, the leaf, being a vital photosynthetic organ of plants, which is an important trait of plant’s ability to obtain crucial resources (Yang et al., 2023), and the variation of its morphological characteristics is key factors influencing plant morphology, structure and adaptation to the environment (Desmond et al., 2021; Rawat et al., 2021). Fruit traits are important reproductive traits in plants and also have a significant impact on plant population establishment and reproduction (Fricke et al., 2019). And seed size, among other things, determines the effectiveness of seed dispersal (Smith et al., 2022).

Cryptocaryeae taxa is an important branch of the Lauraceae, mainly concentrated in tropical and subtropical regions, including the Cryptocarya, Beilschmiedia, Endiandra, and so on, with more than 850 species in the world, which have important ecological and economic values (Song et al., 2020; Song et al., 2023). However, most of the current studies on Lauraceae focus on phylogeny, establishing phylogenetic trees by genomics methods (Song et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022; Cao et al., 2023; Song et al., 2023), and there are fewer studies have been conducted on the relationship between environmental adaptation and key traits in Lauraceae. In this study, we collected data on functional traits of leaves and fruits of Cryptocaryeae taxa (Lauraceae) species from around the world, and investigated and discussed the impact of ecological plasticity in regulating plant environmental adaptation strategies. We aim to: 1) analyze the trends in the distribution of leaf and fruit functional traits along latitude and longitude, and their correlation with environmental factors. 2) quantify the relative contribution of environmental factors to leaf and fruit size in Cryptocaryeae in the context of ecological plasticity. 3) compare and contrast the mechanisms of the independent or synergistic evolution of leaf and fruit functional traits in Cryptocaryeae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

We obtained location data from GBIF (

www.gbif.org) for the reported Cryptocaryeae taxa and extracted 17,117 data records using R scripts (Sun et al., 2020), including 369 unique species (

Figure 1a), and collected data on the functional traits of their leaves and fruits, some of which were obtained by our own experiments. Measurements include leaf length, leaf width, leaf area, fruit length, fruit width, fruit diameter and fruit area.

2.2. Climate Data

The Cryptocaryeae taxa plants was studied by using the environmental factors proposed by O’Donnell and Ignizio (O’Donnel and Ignizio, 2012). These environmental factors include 20 species, named Bio1: annual mean temperature; Bio 2: mean diurnal range; Bio3: isothermality; Bio4: temperature seasonality; Bio5: max temperature of warmest month; Bio6: min temperature of coldest month; Bio7: annual temperature range; Bio8: mean temperature of wettest quarter; Bio9: mean temperature of driest quarter; Bio10: mean temperature of warmest quarter; Bio11: mean temperature of coldest quarter; Bio12: annual precipitation; Bio13: precipitation of wettest month; Bio14: precipitation of driest month; Bio15: precipitation seasonality; Bio16: precipitation of wettest quarter; Bio17: precipitation of driest quarter; Bio18: precipitation of warmest quarter; Bio19: precipitation of coldest quarter; Bio20: digital elevation model (

Table 1).

2.3. Data Analysis

By establishing a general linear model, to analyze the variation trend of leaf and fruit functional traits of Cryptocaryeae taxa along the latitude and longitude and relationships with differentiation rates. The variance expansion factor analysis was performed by the “vif” function in the R software car package to determine the collinearity between the environmental factor variables, and the “dredge” function in the MuMIn package was used to select the multiple linear regression model with the smallest AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) to analyze the influence of environmental factors on the leaf and fruit size of Cryptocaryeae. And The variance decomposition model was further established by using the hierarchical segmentation method to quantify the relative contribution rate of different environmental factors to the functional traits of leaves and fruits. At the same time, the correlation between leaf and fruit size of Cryptocaryeae and environmental factors was analyzed to study the mechanism of ecological adaptability. The significance level of all statistical tests was set to 95% confidence interval. All analytical methods and analytical models were completed using R 4.3.3 software (Team R).

3. Results

3.1. Relationships Between Leaf and Fruit Size of Cryptocaryeae Trees

We logarithmically processed the data of leaf and fruit related functional traits. In simple linear regression analysis, we found that fruit diameter was positively correlated with leaf width (

Figure 2a, p < 0.001, adjusted R

2 = 0.07) and fruit length (

Figure 2b, p < 0.001, adjusted R

2 = 0.56). Significant positive correlations were also found between Leaf length and leaf width (

Figure 2c, p < 0.001, adjusted R

2 = 0.61) and fruit length (

Figure 2d, p < 0.001, adjusted R

2 = 0.02). The fruit diameter was more affected by the fruit length (

Figure 2b, R = 0.75), and the leaf length was more affected by the leaf width (

Figure 2c, R = 0.78). Therefore, here the fruit diameter and leaf length were selected to represent the size of fruit and leaf, respectively.

3.2. Longitudinal and Latitudinal Gradients of Leaf and Fruit Size of Cryptocaryeae Trees

Through logarithmicizing the size of leaves and fruits, to analyze the relationship between them and the latitude and longitude by established a simple linear model. We further observed that both fruit and leaf size of Cryptocaryeae species species were affected by spatial variation in latitude and longitude, but the degree of response differed between the two (

Figure 3). Leaf size tends to be smaller at higher latitudes compared to the tropics, as evidenced by a significant negative correlation (

Figure 3a, p < 0.001, adjusted R

2 = 0.32, R = -0.56). Additionally, leaf size decreases along the longitude gradient (

Figure 3b, R = -0.27), indicating considerable spatial variability. In contrast, the fruit size of the Cryptocaryeae species changed less in the latitude and longitude gradient (

Figure 3c, R = -0.047;

Figure 3d, R = -0.038).

3.3. Global Patterns of Leaf and Fruit and Size Species Distribution of Cryptocaryeae Trees

Beside the latitudinal gradients of leaf size, we find that Ecuador, Malesia, upper Myanmar, Victoria state of southeastern Australia, and west and central Africa harbor the Cryptocaryeae species with largest leaves (

Figure 4a), while Espírito Santo state of Southeast Brazil, Southeast Asia, and west and central Africa have the Cryptocaryeae species with largest fruits (

Figure 4b). In contrast, Argentina, New Zealand, South Africa, and south China harbor the Cryptocaryeae species with smallest leaves (

Figure 4a), while East African Plateau, eastern Australia, and southeast China have the Cryptocaryeae species with smallest fruits (

Figure 4b).

Whittaker’s biomes analysis suggested that the distribution of Cryptocaryeae populations is concentrated in tropical and temperate rainforests and seasonal forests that are relatively warm and humid, with temperatures and precipitation ranging from approximately 15-28 °C and 100-220 cm. In addition, temperate tropical seasonal forest/savanna biomes have a relatively high species richness in the Whittaker biome-wide grid cells (

Figure 1b).

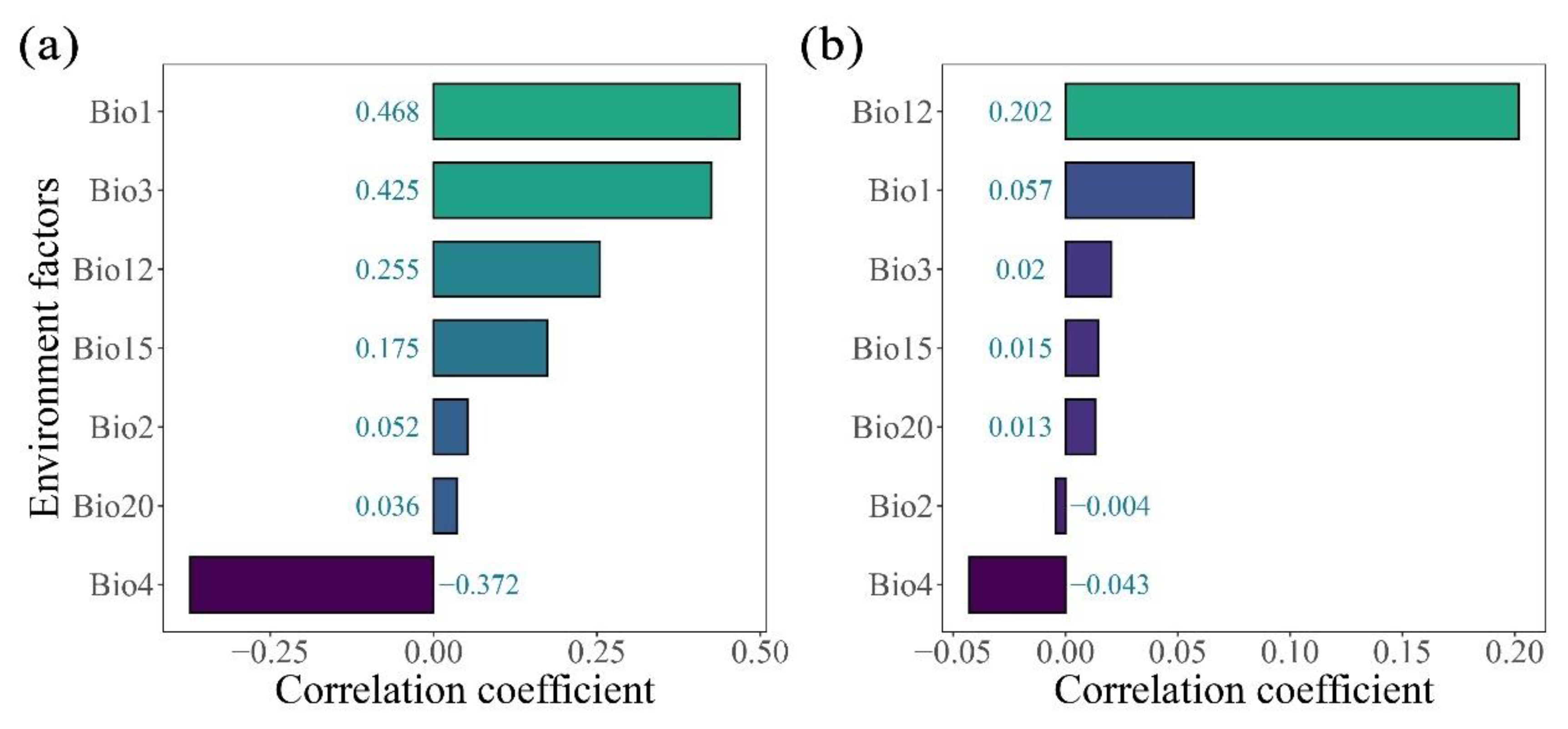

3.4. Climatic Influences on Leaf and Fruit Size of Cryptocaryeae Trees

The relationships between seven environmental factors (Bio1, Bio2, Bio3, Bo4, Bio12, Bio15, Bio20) and leaf and fruit size were analyzed by multiple linear model and correlation analysis. The results showed that leaf size was significantly affected by temperature environmental factors such as Bio1 (R = 0.468, p < 0.001), Bio3 (R = 0.425, p < 0.001), Bio4 (R = -0.373, p < 0.001) (

Figure 5a;

Figure 6b), while fruit size showed a strong correlation with Bio12 (R = 0.202, p < 0.001) (

Figure 5b;

Figure 7b).

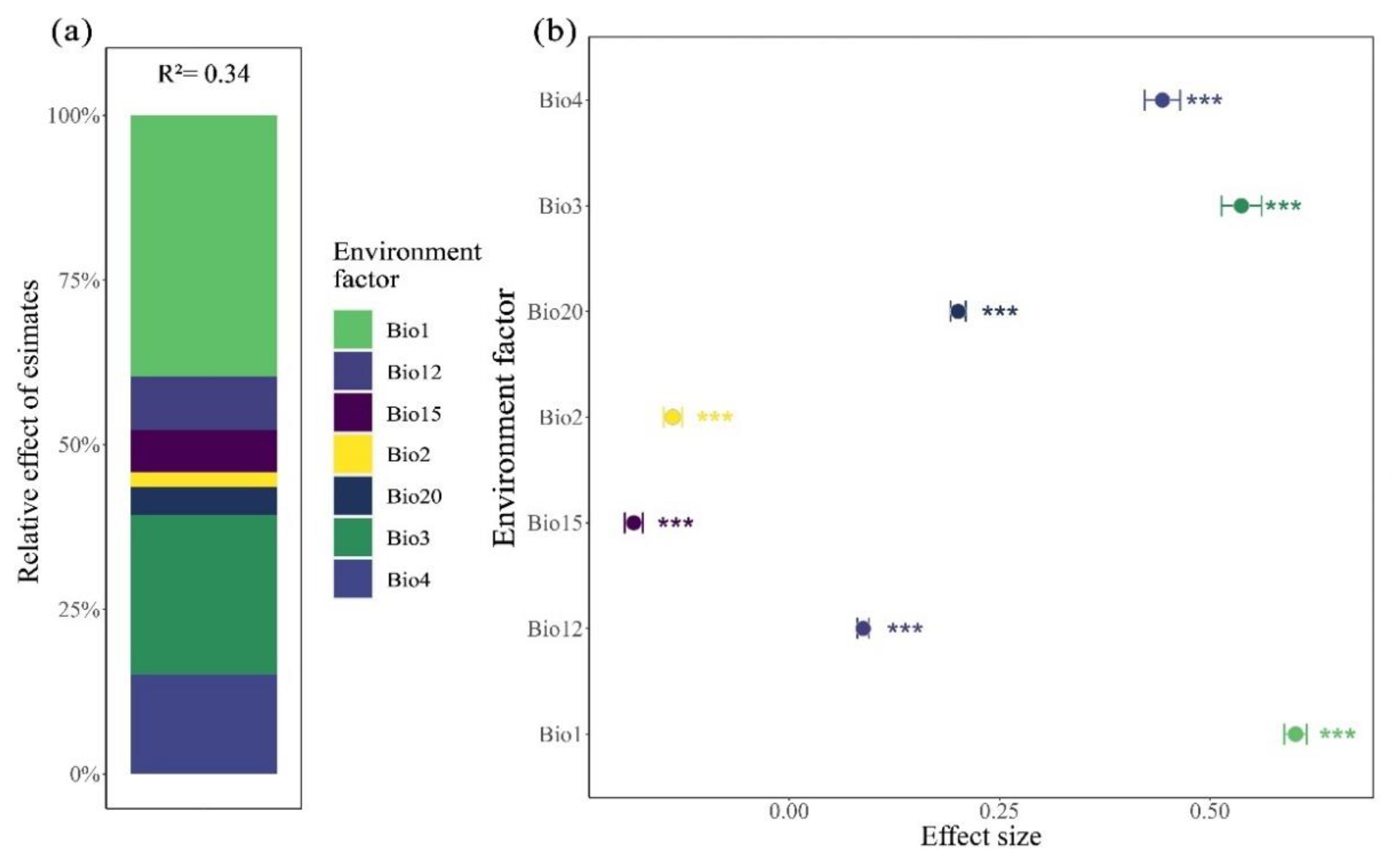

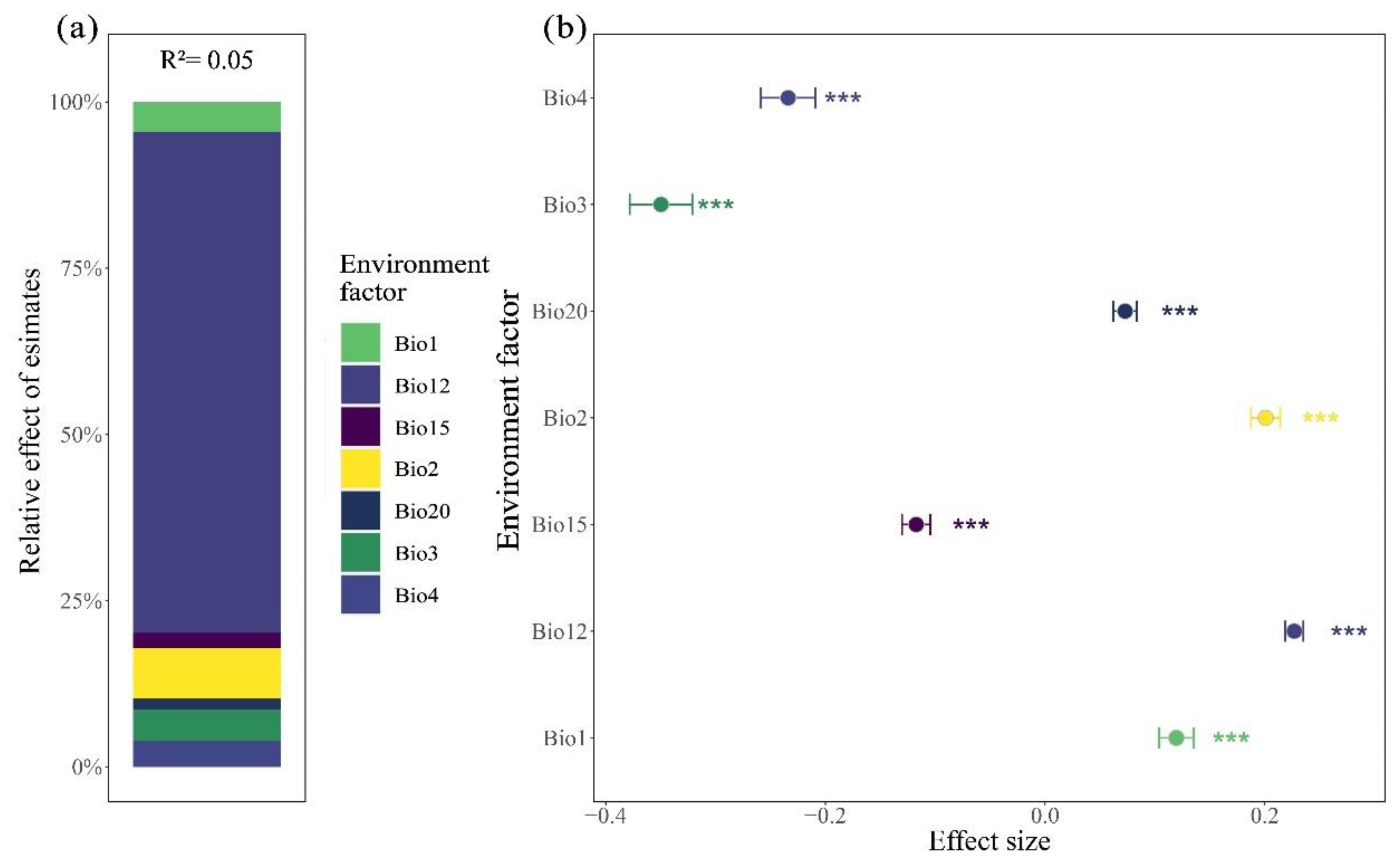

Through the hierarchical segmentation method to further determine the relative importance of each variable of environmental factors to the variation of leaf size and fruit size of Cryptocaryeae. The results showed that the relative importance of each variable to the variation of leaf size of Cryptocaryeae species was Bio1, Bio3, Bio4, Bio12, Bio15, Bio20 and Bio2, respectively. The relative contribution rates of Bio1, Bio3 and Bio4 were 39.73%, 24.24% and 15.16%, respectively (

Figure 6a). The relative importance of fruit size variation was Bio12, Bio2, Bio3, Bio1, Bio4, Bio15, Bio20, and the largest relative contribution rate of Bio12 was 74.63% (Figure 8a)

4. Discussions

In this study, we found that the leaf size of Cryptocaryeae decreased with increasing latitude, and large leaves were mainly distributed in areas with lower latitudes and were significantly affected by environmental factors such as annual mean temperature (Bio1), isotherm (Bio3), and seasonal temperature (Bio3). In agreement with the previous studies (Wright et al., 2017; Fritz et al., 2018; Henn et al., 2018), our results suggest a direct plastic response of leaf size to temperature and latitudinal gradients. As the main organ for photosynthesis and gas exchange in plants, changes in leaf morphology are not only a survival strategy for plants to adapt to changes in the environment (Vendramini et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2020), but also a manifestation of effective reflection of changes in the habitat (McDonald et al., 2003; Peppe et al., 2011), and its variation is frequently related to the plant’s response to environmental factors such as light, water, temperature, etc. (Chitwood and Sinha, 2016). Studies have demonstrated that leaves of plants expand as temperatures increase, while leaf expansion is restricted at low temperatures (Hudson et al., 2011; Bjorkman et al., 2015). In addition, leaves are the most numerous plant organ and are closely related to plant biomass and the resources they require for survival (Zirbel et al., 2017), and leaf traits are considered to be a major determinant of trade-off strategies between tree growth and survival. In low-latitude forest environments, species richness is higher and different plants compete more for resources, so the larger the specific leaf area (SLA), the stronger the plant’s acquisition strategy is likely to be (Meira-Neto et al., 2019), and an increased exposed area of leaves is associated with more light, favoring the plant’s ability to survive in a light-competitive environment (Chapin et al., 1987; Wang et al., 2021). In contrast, large leaves have a significant disadvantage in low-temperature environments at high latitudes, where they are more susceptible to frost damage (Wright et al., 2017). Therefore, the leaf may be more focused on improving photosynthetic efficiency and resource acquisition to adapt to environmental changes (Niinemets, 2020).

In contrast, there was no clear spatial pattern of fruit traits at latitude, while fruit functional traits were significantly influenced mainly by annual precipitation. As important organs for plant reproduction and seed dispersal, the functional traits of fruits, such as fruit size, color, and taste, are more affected by factors such as the selection of dispersers (e.g., animals), etc. (Corlett, 2021), which usually contribute to seed conservation and dispersal (Gonçalves, 2021), and their size and effectiveness of dispersal directly affect the reproduction of populations. For instance, the fleshy fruits of plants are a major food source for many animals (Quintero et al., 2020; González-Varo et al., 2022). In exchange, animals contribute to the reproduction of plant populations by dispersing seeds from the fruit (Rehling et al., 2021). Therefore, the trait of fruit size undergoes little variability in space and this is closely related to the plant’s survival strategy. Adequate precipitation usually favors plant growth and metabolism, and can provide enough water for fruit development so that fruit cells can absorb enough water to expand, thus promoting fruit enlargement. In contrast, in arid regions, plant fruit traits and propagation strategies may also be affected by the degree of aridity (de Oliveira et al., 2020), where insufficient water may lead to smaller fruits, and plant propagation strategies may be more focused on quantity (Pueyo et al., 2008). So precipitation has a greater effect on fruit traits.

In the present study, the different responses of leaf and fruit traits spatially and to environmental factors suggest that while different plant organs may interact with each other during environmental adaptation, they may also exhibit different adaptation pathways and mechanisms. Previous studies have pointed out that changes in plant functional traits in response to the environment are influenced by both genetic evolution and environmental changes (Reich et al., 2003). Genetics and environment have a great effect on plant phenotypes (Nicotra et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2020). Changes in the functional characteristics of plants should enhance their ability to adapt to changes in the local environment (Hofhansl et al., 2021). The response to environmental conditions within a same species is both trait-specific and resource-specific, and varies based on genotype (Ren et al., 2020). The leaf plasticity is co-regulated by both environment and genetics (Maugarny-Calès and Laufs, 2018). However, Studies have shown that the leaf size was not conservative and unstable in evolution (Li et al., 2020), and its variation was more affected by continuous environmental selection rather than phylogenetic development (Reich et al., 2003; Schellenberger Costa et al., 2018). For example, The effect of canopy position on leaf size variation during plant growth is also much higher than genotype (Eisenring et al., 2021). Therefore, the leaf, as the nutrient organ of the plant body, is the key to plant growth and plant survival (Meira-Neto et al., 2019), and its trait variation can indirectly promote plant growth through the promotion of photosynthesis (Chitwood and Sinha, 2016), which affects the development and biomass of the plant (Meira-Neto et al., 2019); while the nutrient organ is not heritable, so the functional trait of leaf size is more affected by the environment, and it is the embodiment of the plasticity that responds to the environmental changes, and the effect of the genetic regulation is smaller. However, fruits are reproductive organs, it was found that plant genome size has a higher effect on fruit seed size than any other phenotypic trait (except lifestyles), suggesting that fruit traits may also be primarily regulated by genetic factors, with environmental and other biotic factors playing a secondary role (Moles et al., 2005; Beaulieu et al., 2007). Additionally, fruit size, as a reproductive trait, has low phenotypic plasticity (Sukhorukov et al., 2023), and climatic factors explain much less of the variation in seed size, with more significant phylogenetic effects on seed size (Zheng et al., 2017).

In addition, leaves and fruits, as important components of plants, differ somewhat in their functions and ecological niches in the plant (Henn et al., 2018), and this difference may lead them to exhibit relatively independent environmental adaptations when subjected to different selective factors. For example, leaves are the most numerous plant organ and are closely related to plant biomass and the resources they require for survival (Zirbel et al., 2017), and leaf traits are considered to be a major determinant of the trade-off strategy between tree growth and survival, as the larger the specific leaf area (SLA), the stronger the plant’s acquisition strategy (Meira-Neto et al., 2019). Therefore, the leaf may be more focused on improving photosynthetic efficiency and resource acquisition to adapt to environmental changes (Niinemets, 2020). While fruits may be more focused on attracting dispersers and protecting seeds, and as the habits of disseminators (fruit-eating animals) change, they tend to evolve larger and more colorful fruits (Encinas-Viso et al., 2014). The uniqueness exhibited by leaf and fruit size in adapting to the environment is the result of a number of different environmental factors driving the process. Thus, further exploration of the relationships between leaf and fruit functional traits under different plant species and ecological conditions could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the complexity of plant evolution and ecological adaptation.

5. Conclusions

The leaf and fruit represent the nutritional and reproductive traits of Cryptocaryeae taxa (Lauraceae), respectively. We did not find common spatial variation between the leaf and fruit size, suggesting that they may be adapted to the environment in divergent mechanism. As a tropical and subtropical plant, leaf size was negatively correlated with latitude gradient and showed positive sensitivity to temperature, indicating that nutritional functional traits may adapt to environmental changes mainly through phenotypic plasticity. In contrast, reproductive traits such as fruit size showed relatively conservative variation along the latitude gradient, which may be mainly affected by survival strategies and genetic control to adapt to the environment. The present study suggests that both ecological and genetic evolutionary factors are need to be considered, as well as the combination of different functional traits, to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the adaptation process of Cryptocaryeae to the environment.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32201543), Natural Science Foundation of GuangXi Province (AD22035177).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alexander, J.M.; Chalmandrier, L.; Lenoir, J.; Burgess, T.I.; Essl, F.; Haider, S.; Kueffer, C.; McDougall, K.; Milbau, A.; Nuñez, M.A.; Pauchard, A.; Rabitsch, W.; Rew, L.J.; Sanders, N.J.; Pellissier, L. Lags in the response of mountain plant communities to climate change. Global Change Biology 2018, 24, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ash, J.D.; Givnish, T.J.; Waller, D.M. Tracking lags in historical plant species’ shifts in relation to regional climate change. Global Change Biology 2017, 23, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Moles, A.T.; Leitch, I.J.; Bennett, M.D.; Dickie, J.B.; Knight, C.A. Correlated evolution of genome size and seed mass. New Phytologist 2007, 173, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkman, A.D.; Elmendorf, S.C.; Beamish, A.L.; Vellend, M.; Henry, G.H.R. Contrasting effects of warming and increased snowfall on Arctic tundra plant phenology over the past two decades. Global Change Biology 2015, 21, 4651–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert-Marsh, L.; de Blois, S. Unravelling potential northward migration pathways for tree species under climate change. Journal of Biogeography 2021, 48, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, J.D.; Hagen, E.R.; Beaulieu, J.M.; Vasconcelos, T. The evolutionary responses of life-history strategies to climatic variability in flowering plants. New Phytologist 2023, 240, 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Yang, L.; Xin, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Tu, Y.; Song, Y.; Xin, P. Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of complete chloroplast genomes from seven Neocinnamomum taxa (Lauraceae). Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Bloom, A.J.; Field, C.B.; Waring, R.H. Plant Responses to Multiple Environmental Factors: Physiological ecology provides tools for studying how interacting environmental resources control plant growth. BioScience 1987, 37, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitwood; Daniel, H.; Sinha, Neelima, R. Evolutionary and Environmental Forces Sculpting Leaf Development. Current Biology 2016, 26, R297–R306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, R.T. Frugivory and Seed Dispersal. In Plant-Animal Interactions: Source of Biodiversity; Del-Claro, K., Torezan-Silingardi, H.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.C.P.; Nunes, A.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Branquinho, C. The response of plant functional traits to aridity in a tropical dry forest. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 747, 141177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, S.C.; Garner, M.; Flannery, S.; Whittemore, A.T.; Hipp, A.L. Leaf shape and size variation in bur oaks: an empirical study and simulation of sampling strategies. American Journal of Botany 2021, 108, 1540–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenring, M.; Unsicker, S.B.; Lindroth, R.L. Spatial, genetic and biotic factors shape within-crown leaf trait variation and herbivore performance in a foundation tree species. Functional Ecology 2021, 35, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas-Viso, F.; Revilla, T.A.; van Velzen, E.; Etienne, R.S. Frugivores and cheap fruits make fruiting fruitful. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2014, 27, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, R.D.; van der Werf, G.R.; Fanin, T.; Fetzer, E.J.; Fuller, R.; Jethva, H.; Levy, R.; Livesey, N.J.; Luo, M.; Torres, O.; Worden, H.M. Indonesian fire activity and smoke pollution in 2015 show persistent nonlinear sensitivity to El Niño-induced drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 9204–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.J.; Donelson, J.M.; Schunter, C.; Ravasi, T.; Gaitán-Espitia, J.D. Beyond buying time: the role of plasticity in phenotypic adaptation to rapid environmental change. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2019, 374, 20180174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, E.C.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Rogers, H.S. Linking intra-specific trait variation and plant function: seed size mediates performance tradeoffs within species. Oikos 2019, 128, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.A.; Rosa, S.; Sicard, A. Mechanisms Underlying the Environmentally Induced Plasticity of Leaf Morphology. Frontiers in Genetics 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B. Case not closed: the mystery of the origin of the carpel. Evodevo 2021, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Varo, J.P.; Onrubia, A.; Pérez-Méndez, N.; Tarifa, R.; Illera, J.C. Fruit abundance and trait matching determine diet type and body condition across frugivorous bird populations. Oikos 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratani, L. Plant Phenotypic Plasticity in Response to Environmental Factors. Advances in Botany 2014, 2014, 208747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, J.J.; Buzzard, V.; Enquist, B.J.; Halbritter, A.H.; Klanderud, K.; Maitner, B.S.; Michaletz, S.T.; Pötsch, C.; Seltzer, L.; Telford, R.J.; et al. Intraspecific Trait Variation and Phenotypic Plasticity Mediate Alpine Plant Species Response to Climate Change. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofhansl, F.; Chacón-Madrigal, E.; Brännström, Å.; Dieckmann, U.; Franklin, O. Mechanisms driving plant functional trait variation in a tropical forest. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 3856–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.M.G.; Henry, G.H.R.; Cornwell, W.K. Taller and larger: shifts in Arctic tundra leaf traits after 16 years of experimental warming. Global Change Biology 2011, 17, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Reich, P.B.; Schmid, B.; Shrestha, N.; Feng, X.; Lyu, T.; Maitner, B.S.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Zou, D.; Tan, Z.-H.; Su, X.; Tang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Feng, X.; Enquist, B.J.; Wang, Z. Leaf size of woody dicots predicts ecosystem primary productivity. Ecology Letters 2020, 23, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yin, D.; He, P.; Cadotte, M.W.; Ye, Q. Linking plant functional traits to biodiversity under environmental change. Biological Diversity 2024, 1, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, L.; Qi, D. Variation in leaf traits at different altitudes reflects the adaptive strategy of plants to environmental changes. Ecology and Evolution 2020, 10, 8166–8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugarny-Calès, A.; Laufs, P. Getting leaves into shape: a molecular, cellular, environmental and evolutionary view. Development 2018, 145, dev161646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P.G.; Fonseca, C.R.; Overton, J.M.; Westoby, M. Leaf-size divergence along rainfall and soil-nutrient gradients: is the method of size reduction common among clades? Functional Ecology 2003, 17, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira-Neto, J.A.A.; Nunes Cândido, H.M.; Miazaki, Â.; Pontara, V.; Bueno, M.L.; Solar, R.; Gastauer, M. Drivers of the growth–survival trade-off in a tropical forest. Journal of Vegetation Science 2019, 30, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, A.T.; Ackerly, D.D.; Webb, C.O.; Tweddle, J.C.; Dickie, J.B.; Pitman, A.J.; Westoby, M. Factors that shape seed mass evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 10540–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murren, C.J.; Auld, J.R.; Callahan, H.; Ghalambor, C.K.; Handelsman, C.A.; Heskel, M.A.; Kingsolver, J.G.; Maclean, H.J.; Masel, J.; Maughan, H.; Pfennig, D.W.; Relyea, R.A.; Seiter, S.; Snell-Rood, E.; Steiner, U.K.; Schlichting, C.D. Constraints on the evolution of phenotypic plasticity: limits and costs of phenotype and plasticity. Heredity 2015, 115, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicotra, A.B.; Atkin, O.K.; Bonser, S.P.; Davidson, A.M.; Finnegan, E.J.; Mathesius, U.; Poot, P.; Purugganan, M.D.; Richards, C.L.; Valladares, F.; van Kleunen, M. Plant phenotypic plasticity in a changing climate. Trends in Plant Science 2010, 15, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niinemets, Ü. Leaf Trait Plasticity and Evolution in Different Plant Functional Types. Annual Plant Reviews online 2020, 473–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnel, M.S.; Ignizio, D.A. Bioclimatic predictors for supporting ecological applications in the conterminous United States; 691; Reston, VA, 2012; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Peppe, D.J.; Royer, D.L.; Cariglino, B.; Oliver, S.Y.; Newman, S.; Leight, E.; Enikolopov, G.; Fernandez-Burgos, M.; Herrera, F.; Adams, J.M.; et al. Sensitivity of leaf size and shape to climate: global patterns and paleoclimatic applications. New Phytologist 2011, 190, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigliucci, M.; Murren, C.J.; Schlichting, C.D. Phenotypic plasticity and evolution by genetic assimilation. Journal of Experimental Biology 2006, 209, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pueyo, Y.; Kefi, S.; Alados, C.L.; Rietkerk, M. Dispersal strategies and spatial organization of vegetation in arid ecosystems. Oikos 2008, 117, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, E.; Pizo, M.A.; Jordano, P. Fruit resource provisioning for avian frugivores: The overlooked side of effectiveness in seed dispersal mutualisms. Journal of Ecology 2020, 108, 1358–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.; Arunachalam, K.; Arunachalam, A.; Alatalo, J.M.; Pandey, R. Assessment of leaf morphological, physiological, chemical and stoichiometry functional traits for understanding the functioning of Himalayan temperate forest ecosystem. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 23807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehling, F.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Braasch, L.V.; Albrecht, J.; Jordano, P.; Schlautmann, J.; Farwig, N.; Schabo, D.G. Within-Species Trait Variation Can Lead to Size Limitations in Seed Dispersal of Small-Fruited Plants. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Wright, I.J.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Craine, J.M.; Oleksyn, J.; Westoby, M.; Walters, M.B. . The Evolution of Plant Functional Variation: Traits, Spectra, and Strategies. International Journal of Plant Sciences 2003, 164, S143–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, T.; Guo, W.; Wang, R.; Ye, S.; Lambertini, C.; Brix, H.; Eller, F. Intraspecific variation in Phragmites australis: Clinal adaption of functional traits and phenotypic plasticity vary with latitude of origin. Journal of Ecology 2020, 108, 2531–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberger Costa, D.; Zotz, G.; Hemp, A.; Kleyer, M. Trait patterns of epiphytes compared to other plant life-forms along a tropical elevation gradient. Functional Ecology 2018, 32, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, C.D. The Evolution of Phenotypic Plasticity in Plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1986, 17, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Sherman, C.D.H.; Cumming, E.E.; York, P.H.; Jarvis, J.C. Size matters: variations in seagrass seed size at local scales affects seed performance. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 2335–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xia, S.-W.; Tan, Y.-H.; Yu, W.-B.; Yao, X.; Xing, Y.-W.; Corlett, R.T. Phylogeny and biogeography of the Cryptocaryeae (Lauraceae). TAXON 2023, 72, 1244–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yu, W.-B.; Tan, Y.-H.; Jin, J.-J.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.-B.; Liu, B.; Corlett, R.T. Plastid phylogenomics improve phylogenetic resolution in the Lauraceae. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 2020, 58, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, G.C.; Salgado-Luarte, C.; Escobedo, V.M.; Valladares, F.; Gianoli, E. Phenotypic plasticity and the leaf economics spectrum: plasticity is positively associated with specific leaf area. Oikos 2022, 2022, e09342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Sousa-Baena, M.S.; Romanov, M.S.; Wang, X. Editorial: Fruit and seed evolution in angiosperms. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Folk, R.A.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Soltis, P.S.; Chen, Z.; Soltis, D.E.; Guralnick, R.P. Recent accelerated diversification in rosids occurred outside the tropics. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, S.; Greve, M.; Olivier, B.; le Roux, P.C. Testing the role of functional trait expression in plant–plant facilitation. Functional Ecology 2021, 35, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oldenborgh, G.J.; Krikken, F.; Lewis, S.; Leach, N.J.; Lehner, F.; Saunders, K.R.; van Weele, M.; Haustein, K.; Li, S.; Wallom, D.; Sparrow, S.; Arrighi, J.; Singh, R.K.; van Aalst, M.K.; Philip, S.Y.; Vautard, R.; Otto, F.E.L. Attribution of the Australian bushfire risk to anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendramini, F.; Díaz, S.; Gurvich, D.E.; Wilson, P.J.; Thompson, K.; Hodgson, J.G. Leaf traits as indicators of resource-use strategy in floras with succulent species. New Phytologist 2002, 154, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, B.; Shi, F.; Zhou, H.; Bisht, N.; Wu, N. Effects of Heterogeneous Environment After Deforestation on Plant Phenotypic Plasticity of Three Shrubs Based on Leaf Traits and Biomass Allocation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.J.; Dong, N.; Maire, V.; Prentice, I.C.; Westoby, M.; Díaz, S.; Gallagher, R.V.; Jacobs, B.F.; Kooyman, R.; Law, E.A.; Leishman, M.R.; Niinemets, Ü.; Reich, P.B.; Sack, L.; Villar, R.; Wang, H.; Wilf, P. Global climatic drivers of leaf size. Science 2017, 357, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Chong, P.; Chen, G.; Xian, J.; Liu, Y.; Yue, Y. Shifting plant leaf anatomical strategic spectra of 286 plants in the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Changing gears along 1050–3070 m. Ecological Indicators 2023, 146, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Ferguson, D.K. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Cinnamomum (Lauraceae). Ecology and Evolution 2022, 12, e9378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Thriving under Stress: How Plants Balance Growth and the Stress Response. Developmental Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X. Seed mass of angiosperm woody plants better explained by life history traits than climate across China. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirbel, C.R.; Bassett, T.; Grman, E.; Brudvig, L.A. Plant functional traits and environmental conditions shape community assembly and ecosystem functioning during restoration. Journal of Applied Ecology 2017, 54, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).