Submitted:

10 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Measurement of Leaf Temperature

2.3. Leaf Trait Measurements

2.4. Environmental Conditions Measurement

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

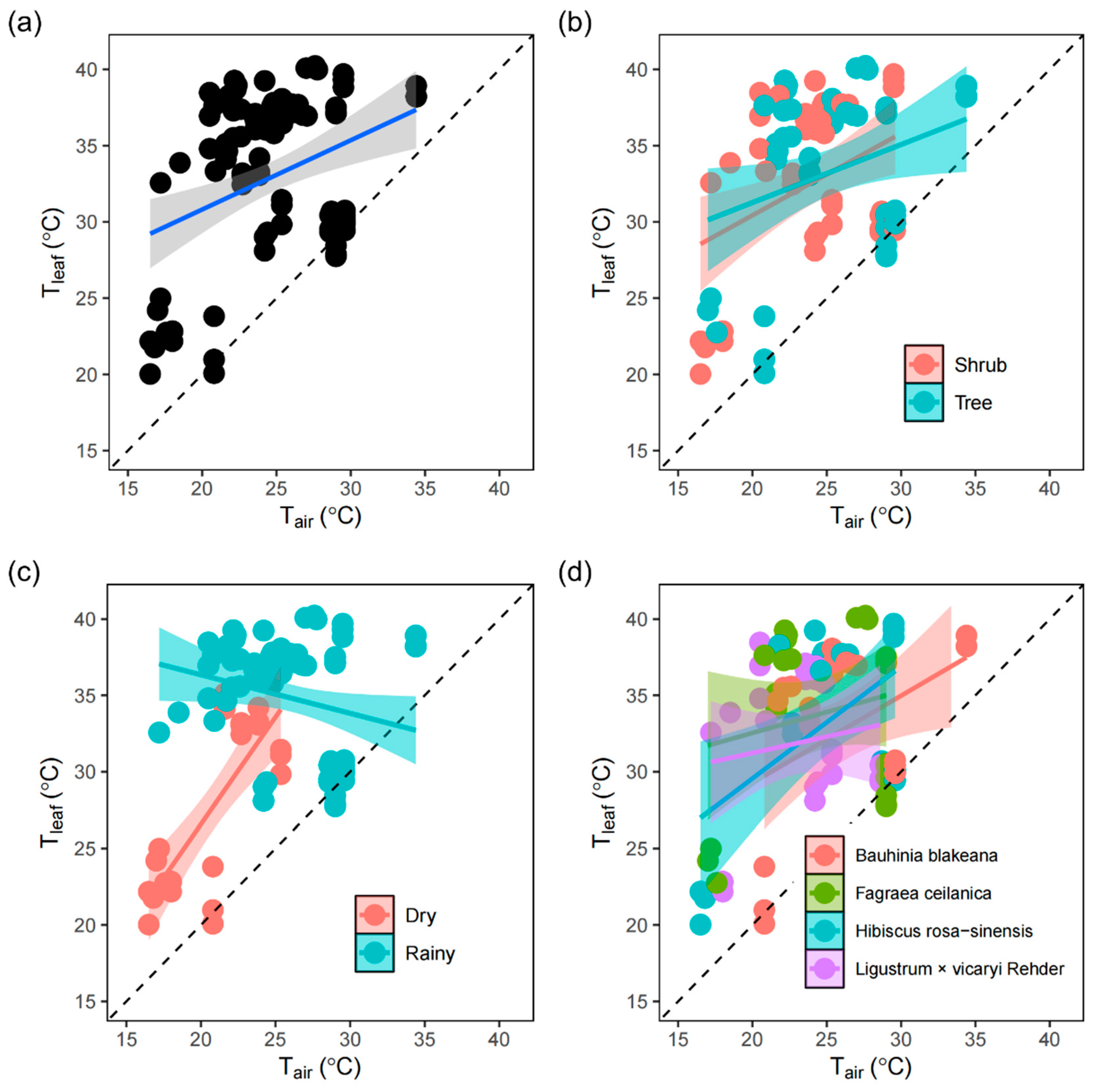

3.1. Leaf Temperature Across Different Groups

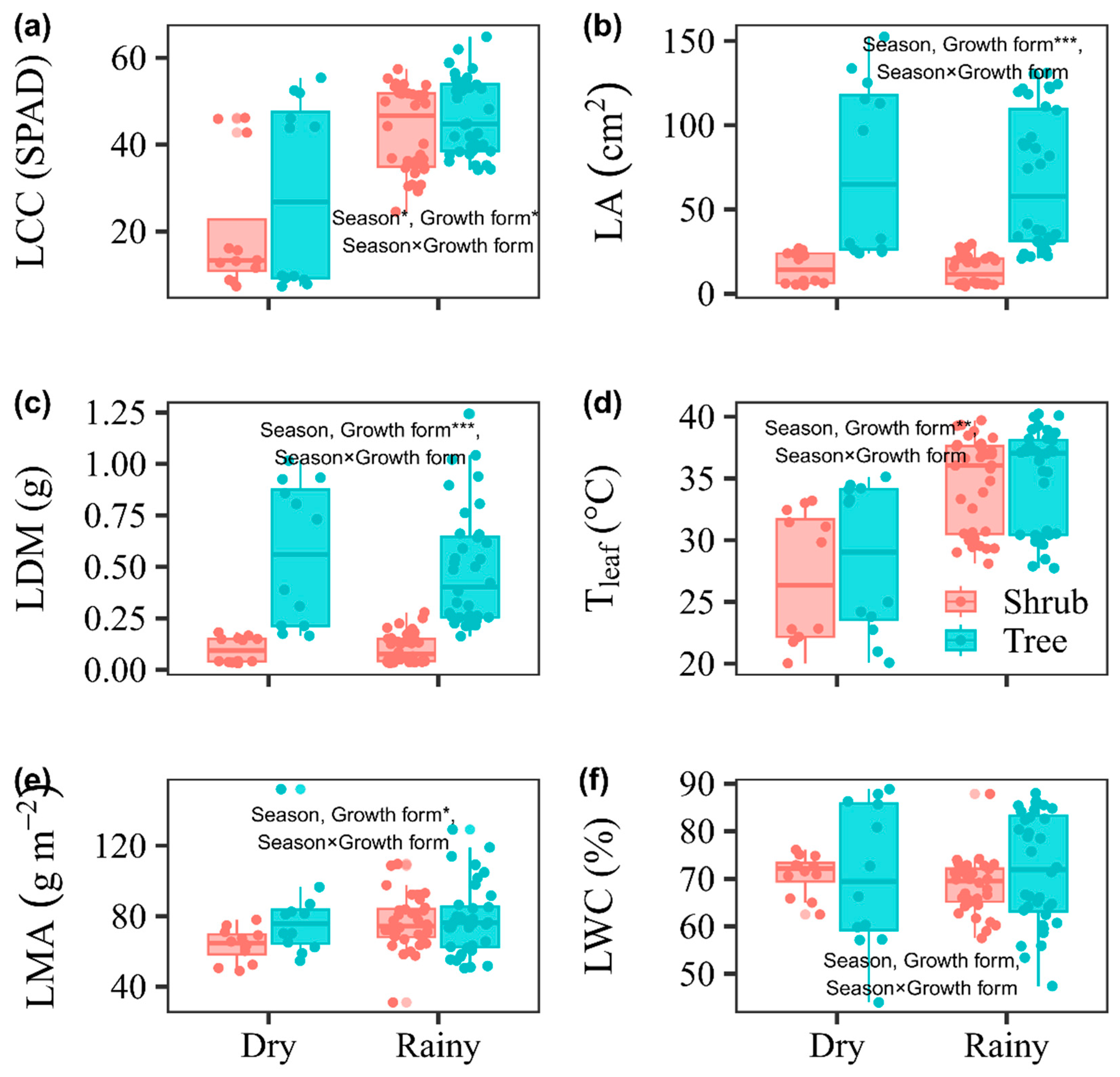

3.2. Leaf Traits According to Growth Type and Season

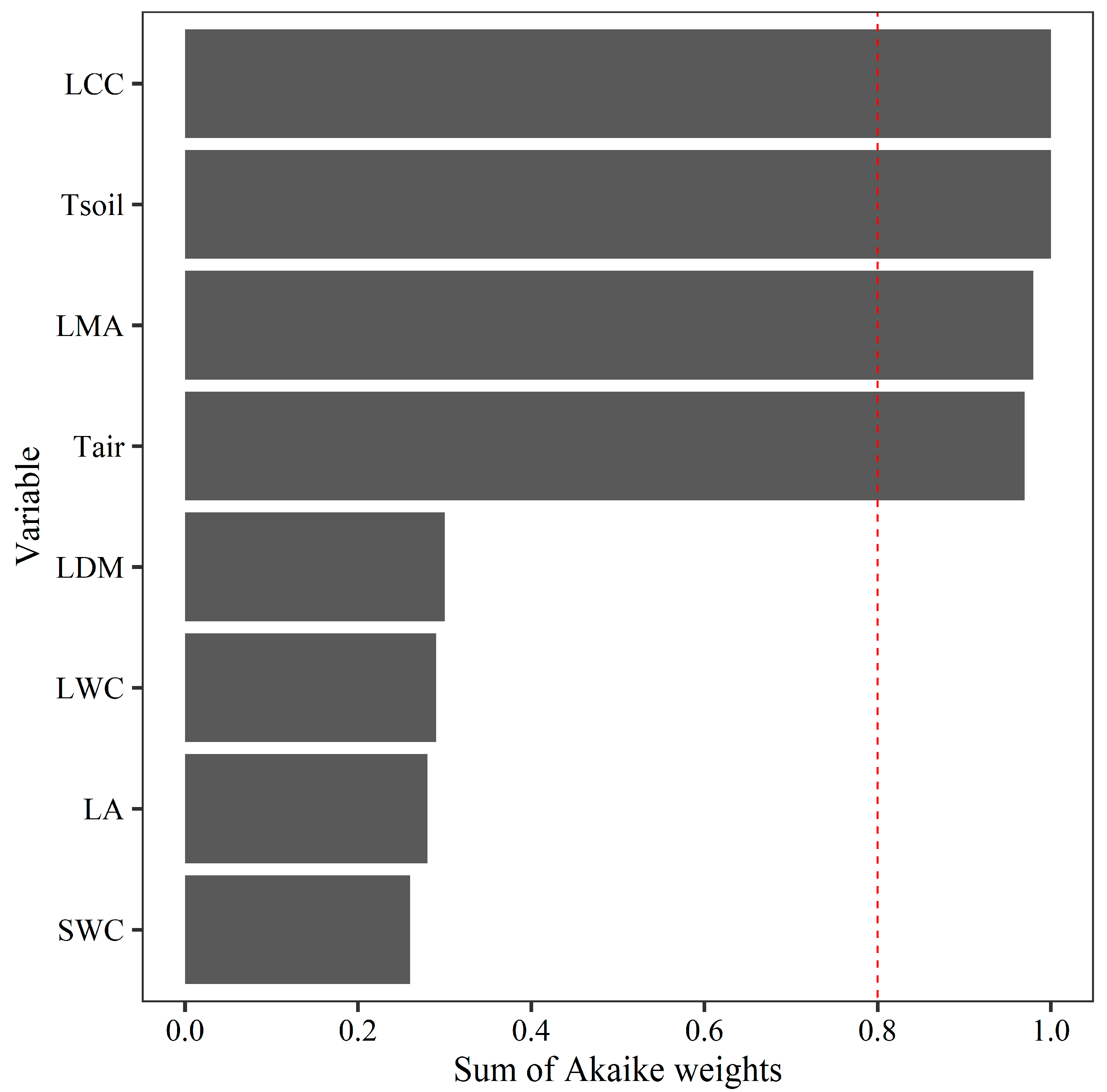

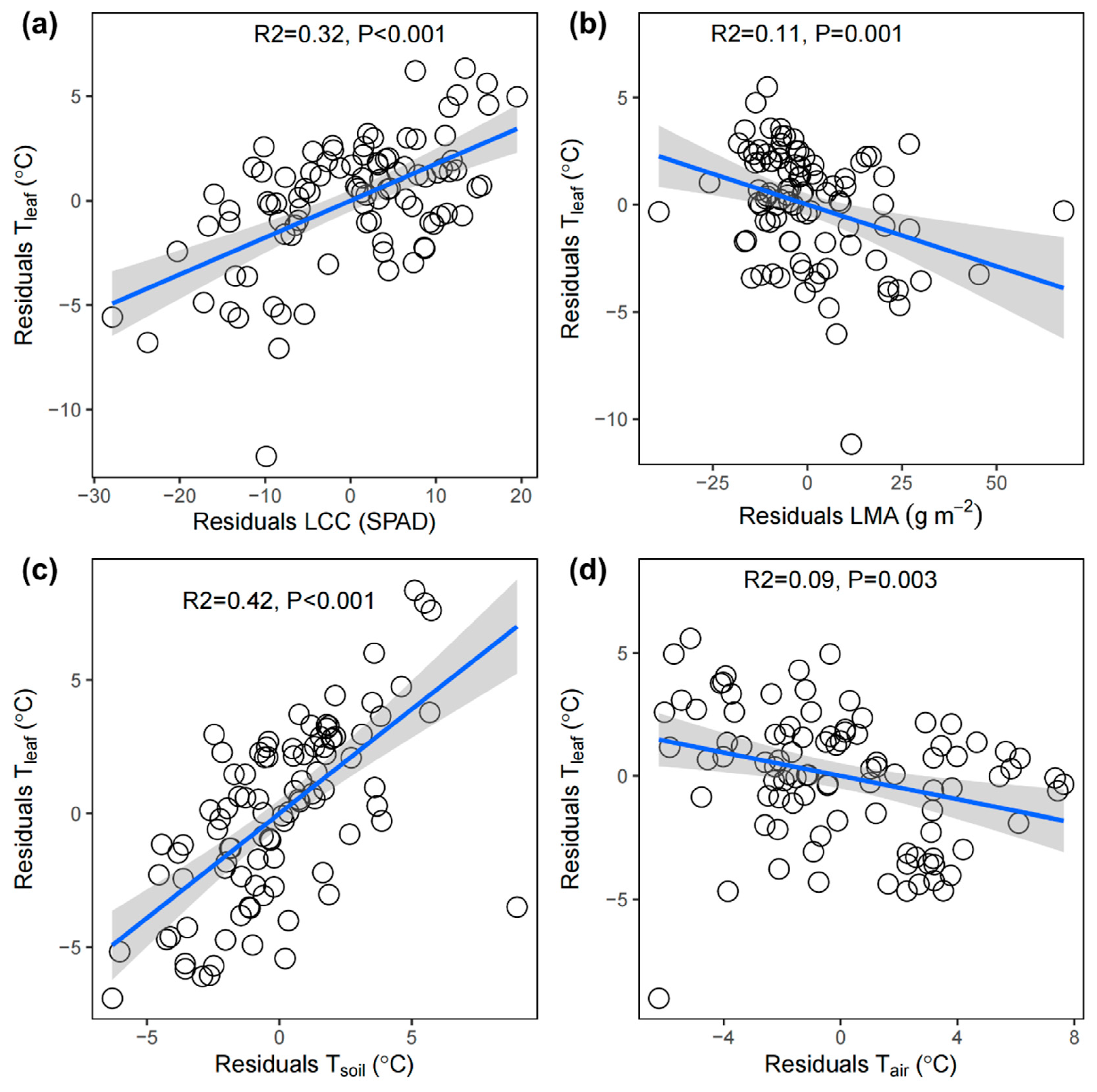

3.3. The Impact of Environmental Conditions and Leaf Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Thermal Regulation Capacity of Leaves

4.2. Effects of Growth Form and Seasonal Variation on Tleaf

4.3. Tleaf Regulated by LCC and LMA

4.4. Tsoil and Tair Mediated Tleaf

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Kitudom, N.; Fauset, S.; Slot, M.; Fan, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Lin, H. Leaf thermal regulation strategies of canopy species across four vegetation types along a temperature and precipitation gradient. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 343, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, B.; Michaletz, S.T. A model for leaf temperature decoupling from air temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 262, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, C.L.; Trugman, A.T.; Roberts, D.A.; Still, C.J.; Scott, R.L.; Caylor, K.K.; Stella, J.C.; Singer, M.B. Evapotranspiration regulates leaf temperature and respiration in dryland vegetation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 339, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthey, A.; Kahmen, A.; Limousin, J.M.; Vilagrosa, A.; Didion-Gency, M.; Mas, E.; Milano, A.; Tunas, A.; Grossiord, C. High heat tolerance, evaporative cooling, and stomatal decoupling regulate canopy temperature and their safety margins in three European oak species. Global Change Biol. 2024, 30, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Yamanaka, T. Application of a two-source model for partitioning evapotranspiration and assessing its controls in temperate grasslands in central Japan. ECOHYDROLOGY 2014, 7, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlein-Safdi, C.; Koohafkan, M.C.; Chung, M.; Rockwell, F.E.; Thompson, S.; Caylor, K.K. Dew deposition suppresses transpiration and carbon uptake in leaves. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 259, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletz, S.T.; Weiser, M.D.; McDowell, N.G.; Zhou, J.; Kaspari, M.; Helliker, B.R.; Enquist, B.J. The energetic and carbon economic origins of leaf thermoregulation. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusenge, M.E.; Madhavji, S.; Way, D.A. Contrasting acclimation responses to elevated CO2 and warming between an evergreen and a deciduous boreal conifer. Global Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3639–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, O.J.L.; Wittemann, M.; Dusenge, M.E.; Habimana, J.; Manishimwe, A.; Mujawamariya, M.; Ntirugulirwa, B.; Zibera, E.; Tarvainen, L.; Nsabimana, D. , et al. Canopy temperatures strongly overestimate leaf thermal safety margins of tropical trees. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 2115–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauset, S.; Freitas, H.C.; Galbraith, D.R.; Sullivan, M.J.P.; Aidar, M.P.M.; Joly, C.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Vieira, S.A.; Gloor, M.U. Differences in leaf thermoregulation and water-use strategies between three co-occurring Atlantic forest tree species. Plant, Cell & Environment 2018, 41, 1618–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletz, S.T.; Weiser, M.D.; Zhou, J.Z.; Kaspari, M.; Helliker, B.R.; Enquist, B.J. Plant Thermoregulation: Energetics, Trait-Environment Interactions, and Carbon Economics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, A.T.; Coombs, L.; Ahuanari, R.D.S.; Fortier, R.P.; Feeley, K.J. Leaf thermal safety margins decline at hotter temperatures in a natural warming 'experiment' in the Amazon. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Still, C.J.; Page, G.; Rastogi, B.; Griffith, D.M.; Aubrecht, D.M.; Kim, Y.; Burns, S.P.; Hanson, C.V.; Kwon, H.; Hawkins, L. , et al. No evidence of canopy-scale leaf thermoregulation to cool leaves below air temperature across a range of forest ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Still, C.J.; Lee, C.K.F.; Ryu, Y.; Blonder, B.; Wang, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Hughes, A.; Li, Y.; Yeung, H.C.H. , et al. Does plant ecosystem thermoregulation occur? An extratropical assessment at different spatial and temporal scales. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1004–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cervigón Morales, A.I.; Olano Mendoza, J.M.; Eugenio Gozalbo, M.; Camarero Martínez, J.J. Arboreal and prostrate conifers coexisting in Mediterranean high mountains differ in their climatic responses. DENDROCHRONOLOGIA 2012, 30, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, E.; Camarero, J.J.; Gazol, A.; Granda, E.; Shetti, R.; Wilmking, M.; Moiseev, P.; Pividori, M.; Carrer, M. Diverging shrub and tree growth from the Polar to the Mediterranean biomes across the European continent. Global Change Biol. 2017, 23, 3169–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazol, A.; Camarero, J.J. Mediterranean dwarf shrubs and coexisting trees present different radial-growth synchronies and responses to climate. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 1687–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cooper, D.J.; Li, Z.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Han, S.; Wang, X. Differences in tree and shrub growth responses to climate change in a boreal forest in China. DENDROCHRONOLOGIA 2020, 63, 125744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranawana, S.R.W.M.C.J.K.; Bramley, H.; Palta, J.A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Role of Transpiration in Regulating Leaf Temperature and its Application in Physiological Breeding. In Translating Physiological Tools to Augment Crop Breeding, Harohalli Masthigowda, M.; Gopalareddy, K.; Khobra, R.; Singh, G.; Pratap Singh, G., Eds. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp 91-119.

- Henry, C.; John, G.P.; Pan, R.; Bartlett, M.K.; Fletcher, L.R.; Scoffoni, C.; Sack, L. A stomatal safety-efficiency trade-off constrains responses to leaf dehydration. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Stocker, B.D.; Hofhansl, F.; Zhou, S.; Dieckmann, U.; Prentice, I.C. Towards a unified theory of plant photosynthesis and hydraulics. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Agrawal, D.; Jajoo, A. Photosynthesis: Response to high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2014, 137, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barral, A. Stomata feel the pressure. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 244–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Sack, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; He, N.; Yu, G. Relationships of stomatal morphology to the environment across plant communities. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, B.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, H.; Liu, C. Spatial variations in stomatal traits and their coordination with leaf traits in Quercus variabilis across Eastern Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bison, N.N.; Michaletz, S.T. Variation in leaf carbon economics, energy balance, and heat tolerance traits highlights differing timescales of adaptation and acclimation. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1919–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, K.; Königer, M. Dry matter production and photosynthetic capacity in Gossypium hirsutum L. under conditions of slightly suboptimum leaf temperatures and high levels of irradiance. Oecologia 1991, 87, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Ball, M.C.; Close, J.D.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Knight, C.A.; Nicotra, A.B.; Vogel, S. Do thick leaves avoid thermal damage in critically low wind speeds? New Phytol. 2012, 194, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Niu, D.; Liu, X. Effects of abiotic stress on chlorophyll metabolism. Plant Sci. 2024, 342, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserej, O.; Feeley, K.J. Variation in leaf temperatures of tropical and subtropical trees are related to leaf thermoregulatory traits and not geographic distributions. Biotropica 2021, 53, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, Y.; Taneda, H.; Noguchi, K.; Terashima, I. Optimum leaf size predicted by a novel leaf energy balance model incorporating dependencies of photosynthesis on light and temperature. Ecol. Res. 2012, 27, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Close, J.D.; Nicotra, A.B. The influence of leaf size and shape on leaf thermal dynamics: does theory hold up under natural conditions? Plant, Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, A.S.; Taylor, S.H.; Pasquet-Kok, J.; Vuong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Watcharamongkol, T.; Scoffoni, C.; Edwards, E.J.; Christin, P.-A.; Osborne, C.P. , et al. Developmental and biophysical determinants of grass leaf size worldwide. Nature 2021, 592, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; He, N.; Hou, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X. Factors Influencing Leaf Chlorophyll Content in Natural Forests at the Biome Scale. FRONT ECOL EVOL 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, Z.; Chen, X.; Cao, X.; Ai, X.; Jiang, B.; Xing, Y. The leaf-air temperature difference reflects the variation in water status and photosynthesis of sorghum under waterlogged conditions. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0219209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, D.; Hao, J.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Xu, W.; Yan, W.; Meng, X. , et al. The development of local ambient air quality standards: A case study of Hainan Province, China. EEH 2024, 3, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.D.; Rotenberg, E.; Tatarinov, F.; Vishnevetsky, I.; Dingjan, T.; Kribus, A.; Yakir, D. Dual reference method for high precision infrared measurement of leaf surface temperature under field conditions. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 2535–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Meng, P.; Tong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P. Temperature sensitivity of leaf flushing in 12 common woody species in eastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 861, 160337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, Y.; Chen, W. A simple method for estimation of leaf dry matter content in fresh leaves using leaf scattering albedo. Global Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina-Garcia, O.; Fernandez-Gamiz, U.; Zulueta, E.; Ugarte-Anero, A.; Portal-Porras, K. Indoor Air Quality Measurements in Enclosed Spaces Combining Activities with Different Intensity and Environmental Conditions. In Buildings, 2024; Vol. 14.

- da Silva Duarte, V.; Treu, L.; Campanaro, S.; Fioravante Guerra, A.; Giacomini, A.; Mas, A.; Corich, V.; Lemos Junior, W.J.F. Investigating biological mechanisms of colour changes in sustainable food systems: The role of Starmerella bacillaris in white wine colouration using a combination of genomic and biostatistics strategies. Food Res. Int. 2024, 193, 114862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Sánchez, A.C.; Slot, M.; Posada, J.M.; Kitajima, K. Spatial and seasonal variation in leaf temperature within the canopy of a tropical forest. Clim. Res. 2016, 71, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, K.Y.; Cheesman, A.W.; Middleby, K.; Rogers, E.I.E.; Wujeska-Klause, A.; Bouet, A.Y.M.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Liddell, M.J.; Cernusak, L.A.; Barton, C.V.M. Similar patterns of leaf temperatures and thermal acclimation to warming in temperate and tropical tree canopies. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughty, C.E.; Goulden, M.L. Seasonal patterns of tropical forest leaf area index and CO2 exchange. J GEOPHYS RES-BIOGEO 2008, 113, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Sánchez, A.C.; Slot, M.; Posada, J.M.; Kitajima, K. Spatial and seasonal variation in leaf temperature within the canopy of a tropical forest. Clim. Res. 2017, 71, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S. Leaves in the lowest and highest winds: temperature, force and shape. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, S. Living in a physical world V. Maintaining temperature. J. Biosci. (Bangalore) 2005, 30, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, M.A. Cold-blooded forests in a warming world. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1455–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.M.; Berry, N.; Milner, K.V.; Leigh, A. Water availability influences thermal safety margins for leaves. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 2179–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.E.; Harwood, R.; Vårhammar, A.; Barbour, M.M.; Reich, P.B.; Barton, C.V.M.; Tjoelker, M.G. No evidence of homeostatic regulation of leaf temperature in Eucalyptus parramattensis trees: integration of CO2 flux and oxygen isotope methodologies. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, S.; Detto, M.; Kim, Y.; Still, C.J. Tropical forest temperature thresholds for gross primary productivity. Ecosphere 2018, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opio, A.; Jones, M.B.; Kansiime, F.; Otiti, T. Influence of climate variables on Cyperus papyrus stomatal conductance in Lubigi wetland, Kampala, Uganda. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2015, 40, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, S.; Ewert, F.; Eyshi Rezaei, E.; Kage, H.; Graß, R. Impact of heat stress on crop yield—on the importance of considering canopy temperature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 044012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Sperry, J.S.; McDowell, N.G. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merilo, E.; Yarmolinsky, D.; Jalakas, P.; Parik, H.; Tulva, I.; Rasulov, B.; Kilk, K.; Kollist, H. Stomatal VPD Response: There Is More to the Story Than ABA. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankasem, N.; Hsu, P.-K.; Lopez, B.N.K.; Franks, P.J.; Schroeder, J.I. Warming triggers stomatal opening by enhancement of photosynthesis and ensuing guard cell CO2 sensing, whereas higher temperatures induce a photosynthesis-uncoupled response. New Phytol. 2024, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Qian, H. Drivers of the differentiation between broad-leaved trees and shrubs in the shift from evergreen to deciduous leaf habit in forests of eastern Asian subtropics. Plant Divers. 2023, 45, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasini, D.E.; Koepke, D.F.; Bush, S.E.; Allan, G.J.; Gehring, C.A.; Whitham, T.G.; Day, T.A.; Hultine, K.R. Tradeoffs between leaf cooling and hydraulic safety in a dominant arid land riparian tree species. Plant, Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 1664–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z.; He, N. Variation in leaf morphological, stomatal, and anatomical traits and their relationships in temperate and subtropical forests. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; Zeng, J.X.; Chen, K.H.; Ding, Q.H.; Shen, Q.R.; Wang, M.; Guo, S.W. Nitrogen improves plant cooling capacity under increased environmental temperature. Plant Soil 2022, 472, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treml, V.; Hejda, T.; Kašpar, J. Differences in growth between shrubs and trees: How does the stature of woody plants influence their ability to thrive in cold regions? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 271, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frenne, P.; Zellweger, F.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.; Scheffers, B.R.; Hylander, K.; Luoto, M.; Vellend, M.; Verheyen, K.; Lenoir, J. Global buffering of temperatures under forest canopies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Ballasus, H.; Engelmann, R.A.; Zielhofer, C.; Sanaei, A.; Wirth, C. Tree species matter for forest microclimate regulation during the drought year 2018: disentangling environmental drivers and biotic drivers. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, H.; Myneni, R.B.; Zhang, Y.; Peñuelas, J.; Piao, S. Seasonal peak photosynthesis is hindered by late canopy development in northern ecosystems. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Niu, C.; Liu, X.; Hu, T.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Dai, G.; Zhang, Y. , et al. Canopy structure regulates autumn phenology by mediating the microclimate in temperate forests. Nat. Clim. Change 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Middel, A.; Liu, H.; Zheng, X.; Wen, Z.; Wang, D. Transpirational cooling and physiological responses of trees to heat. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 320, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Schurgers, G.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Brandt, M.; Yang, H.; Huang, K.; Shen, Q. , et al. Global increase in the optimal temperature for the productivity of terrestrial ecosystems. COMMUN EARTH ENVIRON 2024, 5, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Yan, L.; Mahadi Hasan, M.; Wang, W.; Xu, K.; Zou, G.; Liu, X.-D.; Fang, X.-W. Leaf traits and leaf nitrogen shift photosynthesis adaptive strategies among functional groups and diverse biomes. Ecol. Indicators 2022, 141, 109098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, N.; Wei, T.; Liu, B.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D. Adaptation strategies of leaf traits and leaf economic spectrum of two urban garden plants in China. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.D.; Carter, K.R.; Reed, S.C.; Wood, T.E.; Cavaleri, M.A. Only sun-lit leaves of the uppermost canopy exceed both air temperature and photosynthetic thermal optima in a wet tropical forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 301-302, 108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Wu, H.; Wei, X.; Jiang, M. Contrasting temperature and light sensitivities of spring leaf phenology between understory shrubs and canopy trees: Implications for phenological escape. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 355, 110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Gu, C.; Mumtaz, F.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q. Regional Analysis of Dominant Factors Influencing Leaf Chlorophyll Content in Complex Terrain Regions Using a Geographic Statistical Model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, J.M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Shang, R.; Leng, J.; Shu, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. Comparative assessment of leaf photosynthetic capacity datasets for estimating terrestrial gross primary productivity. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, H.A.; Nakamura, Y.; Furbank, R.T.; Evans, J.R. Effect of leaf temperature on the estimation of photosynthetic and other traits of wheat leaves from hyperspectral reflectance. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratani, L.; Varone, L. Adaptive photosynthetic strategies of the Mediterranean maquis species according to their origin. Photosynthetica 2004, 42, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barai, K.; Calderwood, L.; Wallhead, M.; Vanhanen, H.; Hall, B.; Drummond, F.; Zhang, Y.J. High Variation in Yield among Wild Blueberry Genotypes: Can Yield Be Predicted by Leaf and Stem Functional Traits? AGRONOMY-BASEL 2022, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.A.; Ackerly, D.D. Evolution and plasticity of photosynthetic thermal tolerance, specific leaf area and leaf size: congeneric species from desert and coastal environments. New Phytol. 2003, 160, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóia, R.D.; do Amaral, G.C.; Pezzopane, J.E.M.; Toledo, J.V.; Xavier, T.M.T. Ecophysiology of C3 and C4 plants in terms of responses to extreme soil temperatures. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2018, 30, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.N.; Li, J.H.; Shi, X.J.; Shi, F.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J.; Hao, X.Z.; Luo, H.H.; Wang, Z.B. Increasing cotton lint yield and water use efficiency for subsurface drip irrigation without mulching. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, S.Y.; Hardie, W.J.; Smith, J.P. Stomatal density of grapevine leaves (Vitis vinifera L.) responds to soil temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2011, 17, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen, J.; Domisch, T.; Lehto, T.; Piirainen, S.; Silvennoinen, R.; Repo, T. Separating the effects of air and soil temperature on silver birch. Part I. Does soil temperature or resource competition determine the timing of root growth? Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 2480–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerring Jensen, N.; Vrobel, O.; Akula Nageshbabu, N.; De Diego, N.; Tarkowski, P.; Ottosen, C.-O.; Zhou, R. Stomatal effects and ABA metabolism mediate differential regulation of leaf and flower cooling in tomato cultivars exposed to heat and drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2156–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, L.A.; Dar, Z.A.; Lone, A.A.; Bhat, M.Y.; Ahamad, N. High temperature triggered plant responses from whole plant to cellular level. Plant Physiol Rep. 2020, 25, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, W.; Lopez, J.R.; Smith, K.P. Transpiration increases under high temperature stress: potential mechanisms, trade-offs and prospects for crop resilience in a warming world. Plant, Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 2102–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Ramirez, D.L.; Carmona-Salazar, L.; Morales-Cedillo, F.; Ramírez-Salcedo, J.; Cahoon, E.B.; Gavilanes-Ruíz, M. Plasma Membrane Fluidity: An Environment Thermal Detector in Plants. In Cells, 2021; Vol. 10.

- Jiang, Q.; Jia, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Xiong, D.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Yao, X.; Chen, T. , et al. Soil warming alters fine root lifespan, phenology, and architecture in a Cunninghamia lanceolata plantation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 327, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Slope (95% CI) | R2 | P | Tleaf (°C) | Tair (°C) |

| All | 0.45 (0.21, 0.70) | 0.13 | <0.001 | 33.01±0.55 | 24.83±0.43 |

| Growth type | |||||

| Shrub | 0.54 (0.18. 0.90)a | 0.16 | 0.004 | 32.62±5.31 | 24.09±3.98 |

| Tree | 0.38 (0.03, 0.73)a | 0.09 | 0.035 | 33.39±5.40 | 25.57±4.32 |

| Season | |||||

| Dry | 1.40 (0.88, 1.92)a | 0.59 | <0.001 | 27.66±5.60 | 20.77±3.07 |

| Rainy | −0.25 (−0.50, −0.004)b | 0.06 | 0.047 | 34.79±3.89 | 26.18±3.63 |

| Species | |||||

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis | 0.73 (0.22, 1.25)a | 0.28 | 0.008 | 33.39±5.82 | 25.22±4.21 |

| Bauhinia blakeana | 0.57 (0.07, 1.07)a | 0.21 | 0.026 | 32.96±5.33 | 26.46±4.23 |

| Ligustrum × vicaryi Rehder | 0.21 (−0.39, 0.81)a | 0.02 | >0.05 | 31.86±4.74 | 22.95±3.46 |

| Fagraea ceilanica | 0.27 (−0.28, 0.83)a | 0.05 | >0.05 | 33.82±5.55 | 24.68±4.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).