Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

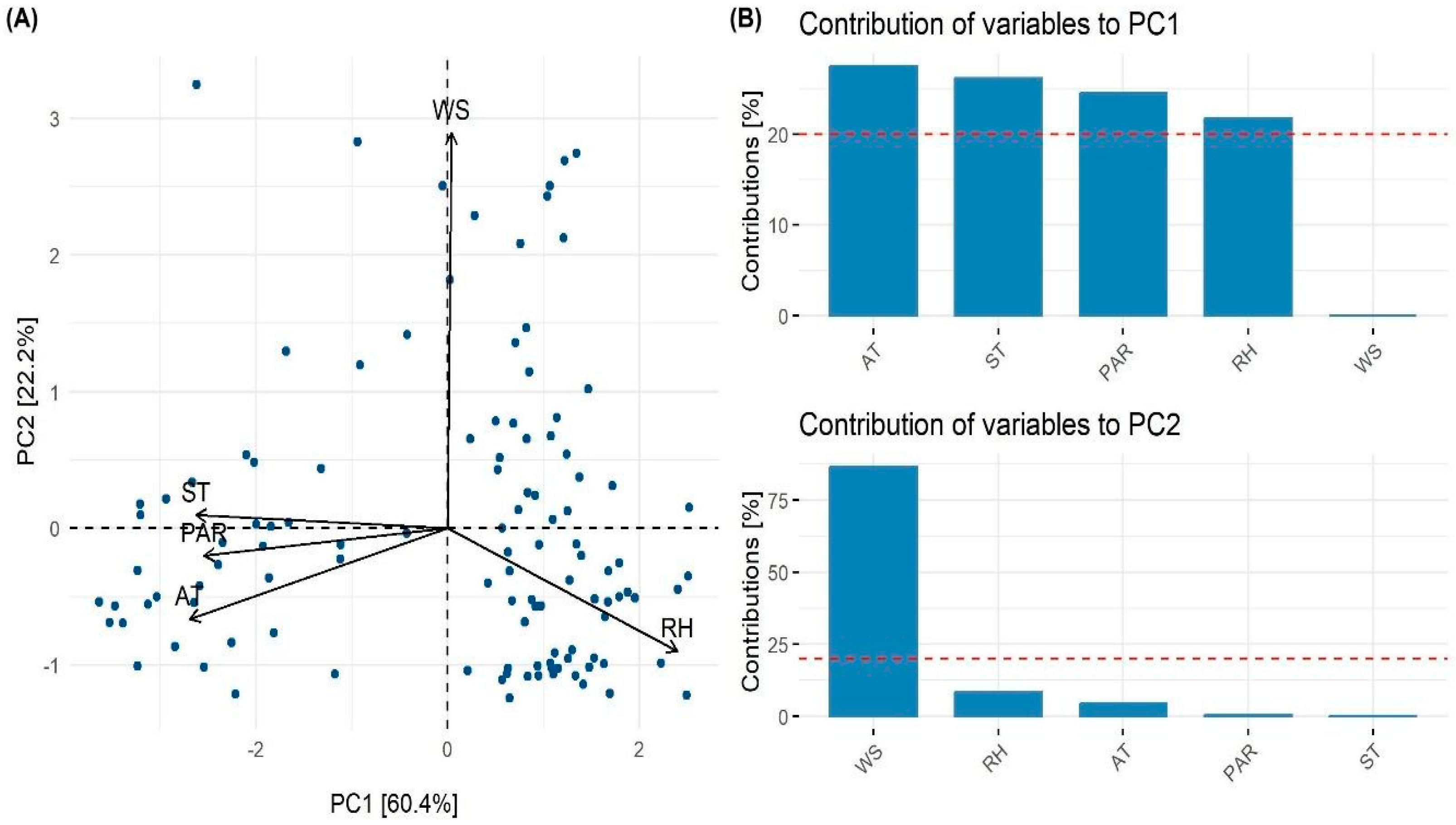

2.1. Environmental Variables Affecting Plant Temperature

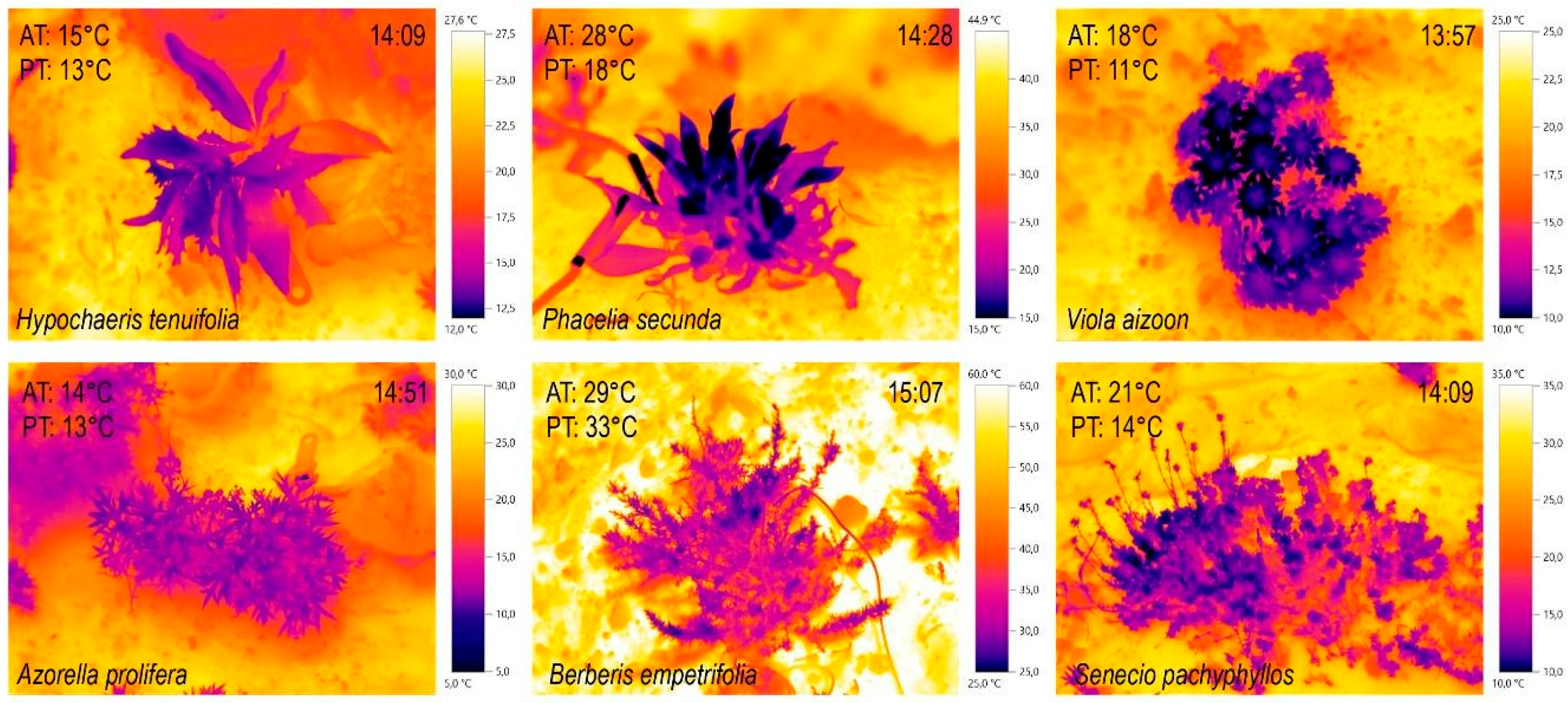

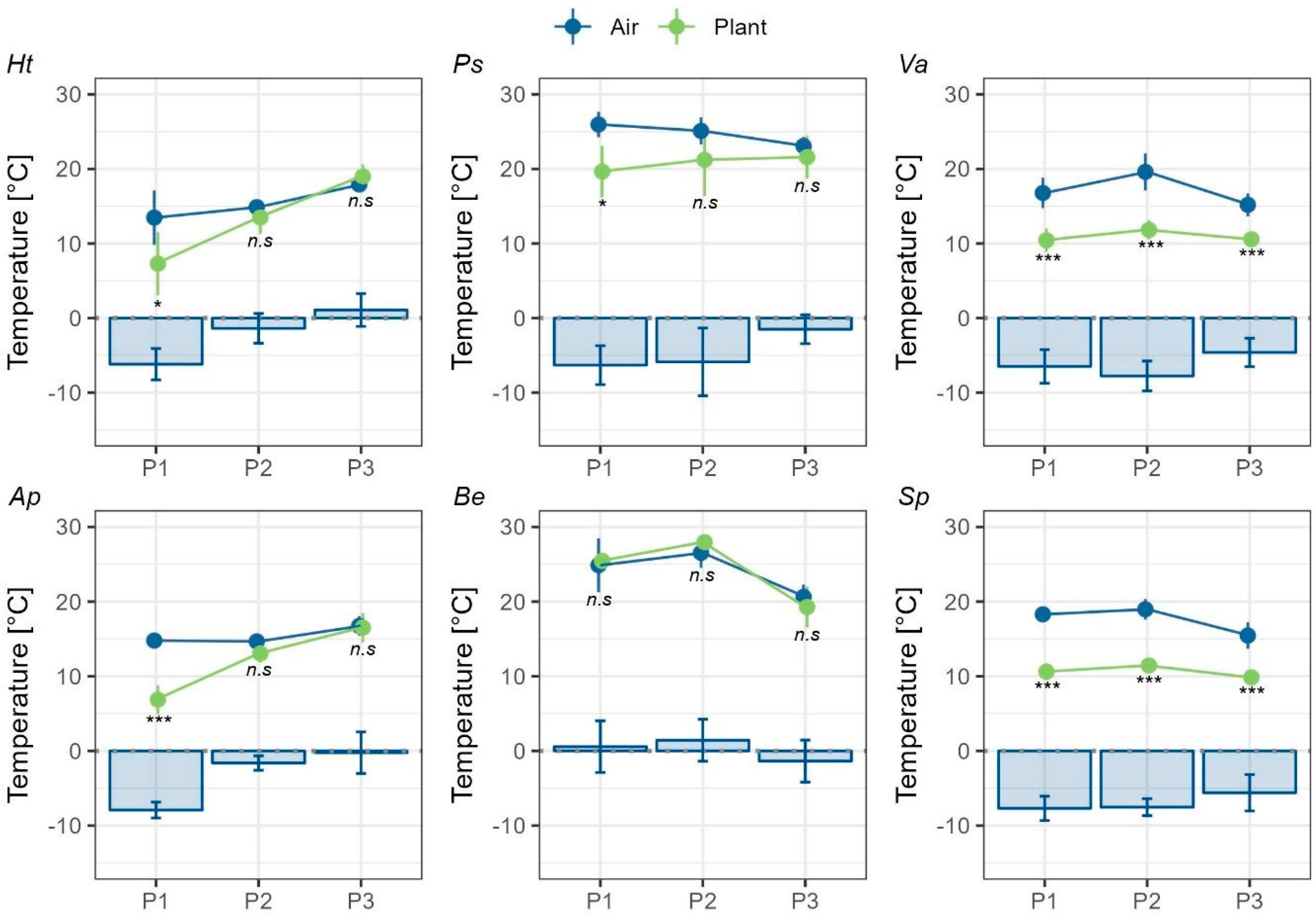

2.2. Plant Thermal Decoupling

2.3. Thermal Decoupling (TD) and Architecture Plant Traits

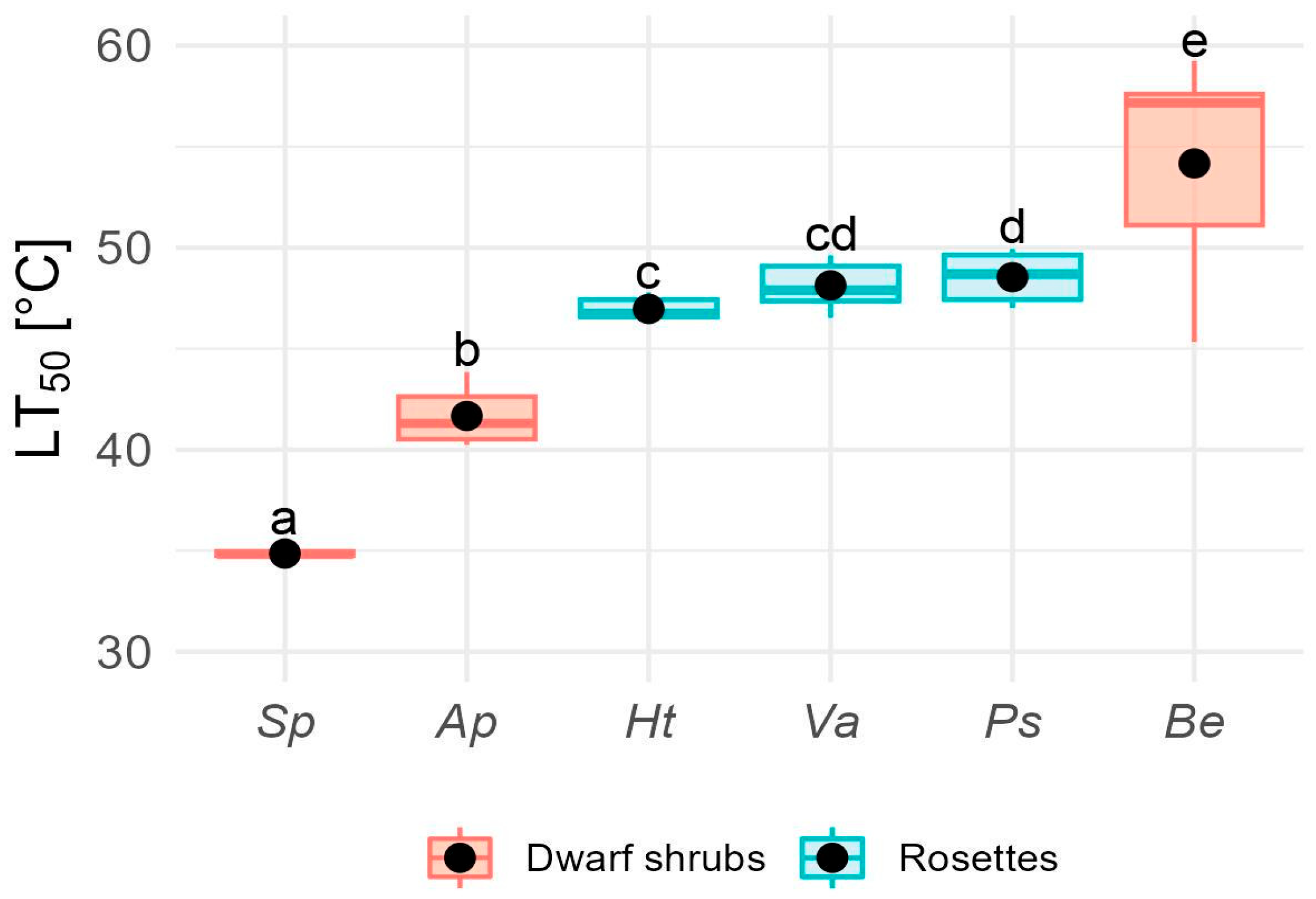

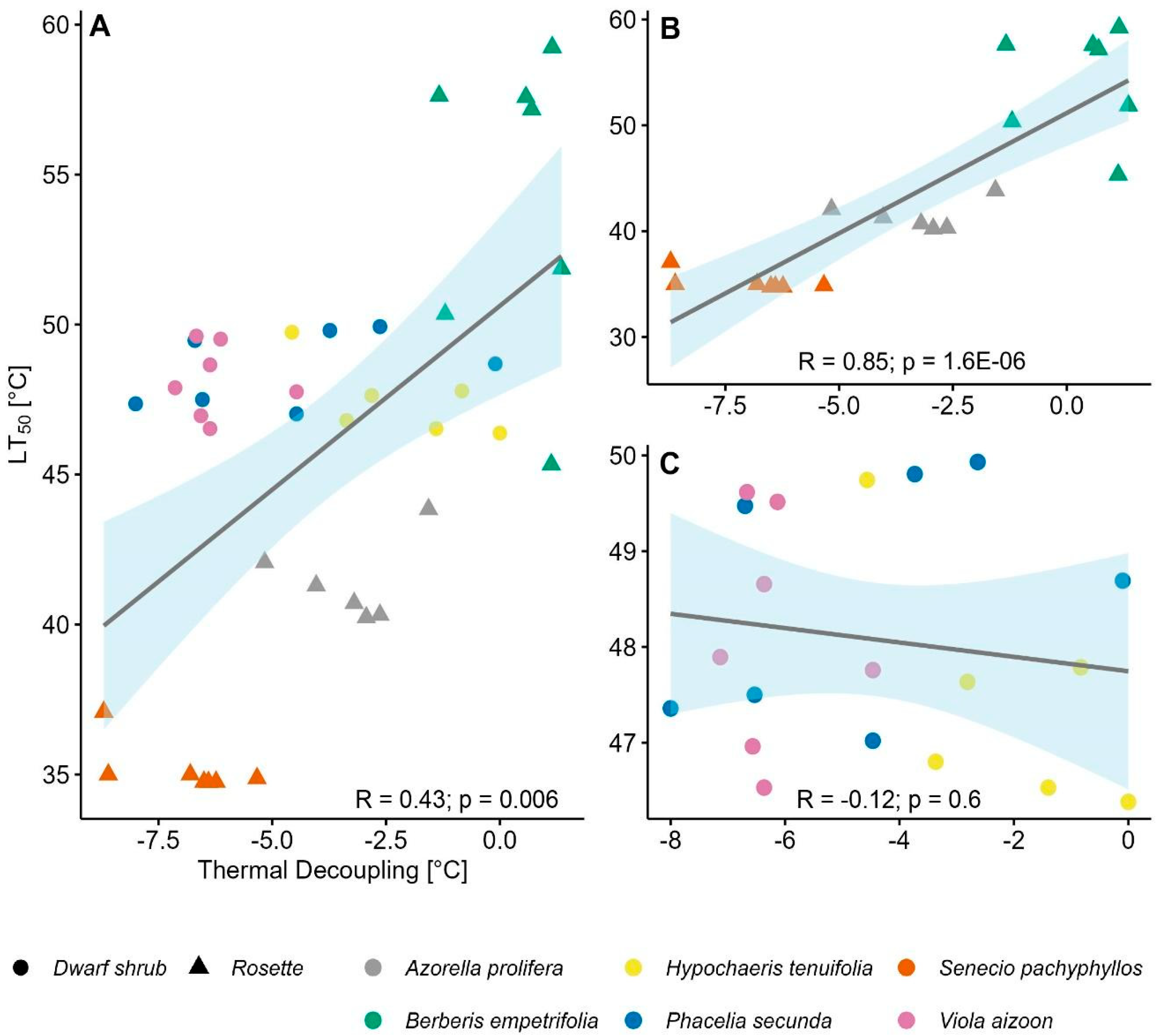

2.4. Relationship Between Thermal Decoupling (TD) and Heat Resistance (LT50)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site and Plant Species

4.2. Environmental Variables, Plant Temperature, and Thermal Decoupling

4.3. Plant Architecture Traits

4.4. Heat Resistance Assessment

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LT50 | Lethal temperature that produces 50% tissue damage (ºC) |

| TD | Thermal Decoupling (ºC) |

| WS | Wind Speed (km h-1) |

| ST | Soil Temperature (ºC) |

| PAR | Photosynthetic Active Radiation (µmol m-2 s-1) |

| AT | Air Temperature (ºC) |

| RH | Relative Humidity (%) |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| GAM | Generalized Additive Model |

| PT | Plant Temperature (ºC) |

| LM | Linear Model |

| PH | Plant Height (cm) |

| CI | Circularity Index |

| PI | Porosity Index |

| PGF | Plant Growth Form |

| IR | Infrared image |

| Fv/Fm | the ratio of variable to maximum fluorescence in dark-adapted leaves |

| PhI | Photoinactivation (%) |

| VPD | Vapor Pressure Deficit (kPa) |

References

- Körner, C. Alpine Plant Life: Functional Plant Ecology of High Mountain Ecosystems; 3rd ed.; Springer: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, D. Y.; Kaplan, F.; Lee, K. J.; Guy, C. L. Acquired Tolerance to Temperature Extremes. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleier, C.; Rundel, P. W. Energy Balance and Temperature Relations of Azorella compacta, a High-Elevation Cushion Plant of the Central Andes. Plant Biol. 2009, 11, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptist, F.; Aranjuelo, I. Interaction of Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolisms in Alpine Plants. In Plants. In Plants in Alpine Regions: Cell Physiology of Adaptation and Survival Strategies; Lütz, C., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, B.; Michaletz, S. T. A Model for Leaf Temperature Decoupling from Air Temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 262, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, J. J. Phenological Physiology: Seasonal Patterns of Plant Stress Tolerance in a Changing Climate. New Phytol. 2022, 237, 1508–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M. T. K.; Dudley, L. S.; Jespersen, G.; Pacheco, D. A.; Cavieres, L. A. Temperature-Driven Flower Longevity in a High-Alpine Species of Oxalis Influences Reproductive Assurance. New Phytol. 2013, 200, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenář, P.; Kučerová, A.; Macková, J.; Romoleroux, K. Temperature Microclimates of Plants in a Tropical Alpine Environment: How Much Does Growth Form Matter? Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2016, 48, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavieres, L. A.; Sierra-Almeida, A. Assessing the Importance of Cold-Stratification for Seed Germination in Alpine Plant Species of the High-Andes of Central Chile. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2018, 30, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, L. S.; Arroyo, M. T.; Fernández-Murillo, M. P. Physiological and Fitness Response of Flowers to Temperature and Water Augmentation in a High Andean Geophyte. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 150, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, J.; Kurnotova, M.; Stastna, P.; Klimesova, J. Alpine Plant Growth and Reproduction Dynamics in a Warmer World. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, D. M. Biophysical Ecology; Springer Advanced Texts in Life Sciences: New York, NY, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J. Climatic Tolerance and the Distribution of Plants. New Phytol. 1987, 106, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, D.; Körner, C. Topographically controlled thermal-habitat differentiation buffers alpine plant diversity against climate warming. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E. A.; Rundel, P. W.; Kaiser, W.; Lam, Y.; Stealey, M.; Yuen, E. M. Fine-Scale Patterns of Soil and Plant Surface Temperatures in an Alpine Fellfield Habitat, White Mountains, California. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2012, 44, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germino, M. J. Plants in Alpine Environments. In Monson, R. K. (Ed.), Ecology and the Environment, The Plant Sciences; Springer: 2014; Vol. 8, pp 327–362. [CrossRef]

- Sklenář, P.; Hedberg, I.; Cleef, A. M. Island Biogeography of Tropical Alpine Floras. J. Biogeogr. 2014, 41, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D. E.; Lubetkin, K. C.; Carrell, A. A.; Jabis, M. D.; Yangk, Y.; Kueppers, L. M. Responses of Alpine Plant Communities to Climate Warming. In Ecosystem Consequences of Soil Warming. Microbes, Vegetation, Fauna and Soil Biochemistry; Mohan, J. E., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; pp 298–346.

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Ball, M. C.; Close, J. D.; Ellsworth, D. S.; Knight, C. A.; Nicotra, A. B.; Vogel, S. Do Thick Leaves Avoid Thermal Damage in Critically Low Wind Speeds? New Phytol. 2012, 194, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcante, S.; Erschbamer, B.; Buchner, O.; Neuner, G. Heat Tolerance of Early Developmental Stages of Glacier Foreland Species in the Growth Chamber and in the Field. Plant Ecol. 2014, 215, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, F.B.; Spomer, G.G. Leaf temperatures of alpine plants in the field. Planta 1964, 60, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Close, J. D.; Nicotra, A. B. The Influence of Leaf Size and Shape on Leaf Thermal Dynamics: Does Theory Hold Up under Natural Conditions? Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaletz, S. T.; Weiser, D.; Zhou, J.; Kaspari, M.; Helliker, B. R.; Enquist, B. J. Plant Thermoregulation: Energetics, Trait–Environment Interactions, and Carbon Economics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletz, S. T.; Weiser, M. D.; McDowell, N. G.; Zhou, J.; Kaspari, M.; Helliker, B. R.; Enquist, B. J. The Energetic and Carbon Economic Origins of Leaf Thermoregulation. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Prentice, I. C.; Harrison, S. P.; Song, Q. H.; Zhang, Y. P.; Collatz, G. J. Biophysical Homoeostasis of Leaf Temperature: A Neglected Process for Vegetation and Land-Surface Modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liancourt, P.; Song, X.; Macek, M.; Santrucek, J.; Dolezal, J. Plant’s-Eye View of Temperature Governs Elevational Distributions. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4094–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bison, N. N.; Michaletz, S. T. Variation in Leaf Carbon Economics, Energy Balance, and Heat Tolerance Traits Highlights Differing Timescales of Adaptation and Acclimation. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1919–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, C.; Paulsen, J. A Climate-Based Model to Predict Potential Treeline Position around the Globe. Alp. Bot. 2014, 124, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzer, F. C.; Goldstein, G.; Rada, F. Páramo Microclimate and Leaf Thermal Balance of Andean Giant Rosette Plants. In Rundel, P. W.; Smith, A. P., Meinzer, F. C., Eds.; Tropical Alpine Environments: Plant Form and Function; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Monasterio, M.; Sarmiento, L. Adaptive Radiation of Espeletia in the Cold Andean Tropics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1991, 6, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, E. Cold Tolerance in Tropical Alpine Plants. In Tropical Alpine Environments: Plant Form and Function; Rundel, P. W., Smith, A. P., Meinzer, F. C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, P.M. Diurnal temperature variation in the major growth forms of an Ecuadorian páramo plant community. In The Ecology of Volcán Chiles: High-Altitude Ecosystems on the Ecuador-Colombia Border; Ramsay, P.M., Ed.; 2001; pp. 101–112.

- Larcher, W. Bioclimatic Temperatures in the High Alps. In Lütz, C., Ed.; Plants in Alpine Regions; Springer: Vienna, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, B.; Escobar, S.; Kapás, R. E.; Michaletz, S. T. Low Predictability of Energy Balance Traits and Leaf Temperature Metrics in Desert, Montane and Alpine Plant Communities. Funct. Ecol. 2020, 34, 1882–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, O. L. Untersuchungen über Wärmehaushalt und Hitzeresistenz Mauretanischer Wüsten- und Savannenpflanzen. Flora 1959, 147, 595–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W. K. Temperatures of Desert Plants—Another Perspective on Adaptability of Leaf Size. Science 1978, 201, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, P.; Fan, Z. Stronger Cooling Effects of Transpiration and Leaf Physical Traits of Plants from a Hot Dry Habitat than from a Hot Wet Habitat. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 2202–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, W.; Wagner, J. Temperatures in the Life Zones of the Tyrolean Alps. Sitzungsber. Abt. I 2010, 213, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorský, M.; Doležal, J.; de Bello, F.; Klimešová, J.; Klimeš, L. Vegetation Types of East Ladakh: Species and Growth Form Composition along Main Environmental Gradients. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2011, 14, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Dong, X.; Yu, T.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, W.; Widmer, A.; Karrenberg, S. A Single Nucleotide Deletion in Gibberellin20-oxidase1 Causes Alpine Dwarfism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, R.E.; van Zuijlen, K.; Birkemoe, T.; Klanderud, K.; Lang, S.I.; Bokhorst, S.; Wardle, D.A.; Asplund, J. Contrasting drivers of community-level trait variation for vascular plants, lichens and bryophytes across an elevational gradient. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 2430–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F. Light Heterogeneity and Plants: From Ecophysiology to Species Coexistence and Biodiversity. In Prog. Bot.; Esser, K., Lüttge, U., Beyschlag, W., Hellwig, F., Eds.; Springer, 2003; Vol. 64, pp 1–17.

- Niinemets, Ü.; Valladares, F. Photosynthetic acclimation to simultaneous and interacting environmental stresses along natural light gradients: Optimality and constraints. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldocchi, D. D.; Keeney, R.; Rey-Sánchez, A. C.; Fisher, J. B. Atmospheric Humidity Deficits Tell Us How Soil Moisture Deficits Down-Regulate Ecosystem Evaporation. Adv. Water Resour. 2022, 159, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H. G.; Rotenberg, E. Energy, Radiation and Temperature Regulation in Plants. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences 2001, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J. L.; Unsworth, M. H. Principles of Environmental Physics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M. Physical Concepts. In Food Process Engineering Principles and Data; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, M. J.; Verboom, G. A.; Rebelo, A. G.; Cramer, M. D. Ecophysiological Significance of Leaf Size Variation in Proteaceae from the Cape Floristic Region. Funct. Ecol. 2010, 24, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauslaa, Y. Heat Resistance and Energy Budget in Different Scandinavian Plants. Ecography 1984, 7, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, G.; Braun, V.; Buchner, O.; Taschler, D. Leaf Rosette Closure in the Alpine Rock Species Saxifraga paniculata Mill.: Significance for Survival of Drought and Heat under High Irradiation. Plant Cell Environ. 1999, 22, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, O.; Neuner, G. Variability of Heat Tolerance in Alpine Plant Species Measured at Different Altitudes. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2003, 35, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, W.; Kainmüller, C.; Wagner, J. Survival Types of High Mountain Plants under Extreme Temperatures. Flora 2010, 205, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, G.; Buchner, O. Dynamics of Tissue Heat Tolerance and Thermotolerance of PS II in Alpine Plants. In Lütz, C., Ed.; Plants. In Lütz, C., Ed.; Plants in Alpine Regions; Springer-Verlag: Vienna, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, O.; Stoll, M.; Karadar, M.; Kranner, I.; Neuner, G. Application of Heat Stress In Situ Demonstrates a Protective Role of Irradiation on Photosynthetic Performance in Alpine Plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, R.F.; Nicotra, A.B.; Kruuk, L.E.B.; Arnold, P.A. Tolerance of warmer temperatures does not confer resilience to heatwaves in an alpine herb. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 615119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehn, E. M.; Rudmann-Maurer, K.; Körner, C.; Maselli, D. Climate Change and Its Link to Diversity. In Mountain Biodiversity and Global Change; Rudmann-Maurer, K., Körner, C., Maselli, D., Eds.; GMBA-DIVERSITAS, 2010; pp 33–41.

- Inouye, D. W. Effects of Climate Change on Alpine Plants and Their Pollinators. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1469, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R. Cambio Climático: Bases Físicas e Impactos en Chile. Rev. Tierra Adentro-INIA 2011, 93, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- González-Reyes, Á.; Jacques-Coper, M.; Bravo, C.; Rojas, M.; Garreaud, R. Evolution of Heatwaves in Chile since 1980. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2023, 41, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M. T.; Till-Bottraud, I.; Torres, C.; Henríquez, C. A.; Martínez, J. Display Size Preferences and Foraging Habits of High Andean Butterflies Pollinating Chaetanthera lycopodioides (Asteraceae) in the Subnival of the Central Chilean Andes. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2007, 39, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Almeida, A.; Cavieres, L.A.; Bravo, L.A. Freezing resistance of high-elevation plant species is not related to their height or growth-form in the Central Chilean Andes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 69, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Grace, J.; Allen, S.; Slack, F. Temperature and Stature: A Study of Temperatures in Montane Vegetation. Funct. Ecol. 1987, 1, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Rain and Snow at High Elevation. In Lütz, C., Ed.; Plants in Alpine Regions; Springer: 2012; pp 103–113. [CrossRef]

- León-García, I. V.; Lasso, E. High Heat Tolerance in Plants from the Andean Highlands: Implications for Paramos in a Warmer World. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, E. E.; Venn, S. E. Thermal Tolerance and Growth Responses to In Situ Soil Water Reductions among Alpine Plants. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2022, 15, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, O.S.; Heskel, M.A.; Reich, P.B.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Weerasinghe, L.K.; Penillard, A.; Zhu, L.; Egerton, J.J.G.; Bloomfield, K.J.; Creek, D.; Bahar, N.H.A.; Griffin, K.L.; Hurry, V.; Meir, P.; Turnbull, M.H.; Atkin, O.K. Thermal limits of leaf metabolism across biomes. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, C.; Hiltbrunner, E. The 90 Ways to Describe Plant Temperature. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2018, 30, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, T.; Feeley, K. Photosynthetic heat tolerances and extreme leaf temperatures. Funct. Ecol. 2020, 34, 2236–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Urzúa, C. (Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile). Personal Communication, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Torres, C.; Riveros, G.; Morales, L. V.; Sierra-Almeida, A.; Schoebitz, M.; Hasbún, R. Relieving Your Stress: PGPB Associated with Andean Xerophytic Plants Are Most Abundant and Active on the Most Extreme Slopes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1062414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica-Téllez, A.; Garreaud, R.; Meza, F.; Bustos, S.; Falvey, M.; Ibarra, M.; Duarte, K.; Ormazábal, R.; Dittborn, R.; Silva, I. Informe Proyecto ARClim: Atlas de Riesgos Climáticos para Chile; Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia, Centro de Cambio Global UC y Meteodata: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H. G.; Vaughan, R. A. Remote Sensing of Vegetation: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, G. S.; Norman, J. M. An Introduction to Environmental Biophysics, 2nd ed.; Springer+Business Media: New York, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J. L.; Unsworth, M. H. Principles of Environmental Physics, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H. G. Plants and Microclimate: A Quantitative Approach to Environmental Plant Physiology; 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McIlveen, R. Fundamentals of Weather and Climate; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, P. A.; White, M. J.; Cook, A. M.; Leigh, A.; Briceño, V. F.; Nicotra, A. B. Plants Originating from More Extreme Biomes Have Improved Leaf Thermoregulation. Ann. Bot. 2025, mcaf080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, J.A. Transpiration: how many functions? New Phytol. 2008, 180, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholová, J.; Nepolean, T.; Hash, C. T.; Supriya, A.; Rajaram, V.; Senthilvel, S.; Kakkera, A.; Yadav, R. S.; Vadez, V. Water Saving Traits Co-Map with a Major Terminal Drought Tolerance Quantitative Trait Locus in Pearl Millet [Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.]. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 1337–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belko, N.; Zaman-Allah, M.; Diop, N. N.; Cisse, N.; Zombre, G.; Ehlers, J. D.; Vadez, V. Restriction of Transpiration Rate under High Vapour Pressure Deficit and Non-Limiting Water Conditions Is Important for Terminal Drought Tolerance in Cowpea. Plant Biol. 2013, 15, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, T. J.; McAdam, S. A. Passive Origins of Stomatal Control in Vascular Plants. Science 2011, 331, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.W. Environmental control of leaf water conductance in conifers. Can. J. For. Res. 1976, 6, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G. Feedforward Responses of Stomata to Humidity. Funct. Plant Biol. 1978, 5, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P. J.; Cowan, I. R.; Farquhar, G. D. The Apparent Feedforward Response of Stomata to Air Vapour Pressure Deficit: Information Revealed by Different Experimental Procedures with Two Rainforest Trees. Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T. N.; Cernusak, L. A.; Novick, K. A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R. T. W.; Sperry, J. S.; McDowell, N. G. Plant Responses to Rising Vapor Pressure Deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, P. L.; Froend, R. H.; Franks, P. J. Smaller, Faster Stomata: Scaling of Stomatal Size, Rate of Response, and Stomatal Conductance. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, J.A. Speedy small stomata? J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAusland, L.; Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Davey, P.; Baker, N. R.; Brendel, O.; Lawson, T. Effects of Kinetics of Light-Induced Stomatal Responses on Photosynthesis and Water-Use Efficiency. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Oliveira, R.S. Plant Physiological Ecology, 3rd ed.Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, M. Microclimatic Convergence of High-Elevation Tropical Páramo and Temperate-Zone Alpine Environments. J. Veg. Sci. 1996, 7, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetene, M.; Gashaw, M.; Nauke, P.; Beck, E. Microclimate and Ecophysiological Significance of the Tree-like Life-form of Lobelia rhynchopetalum in a Tropical Alpine Environment. Oecologia 1998, 113, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germino, M. J.; Smith, W. K. Relative Importance of Microhabitat, Plant Form and Photosynthetic Physiology to Carbon Gain in Two Alpine Herbs. Funct. Ecol. 2001, 15, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernusca, A. Standörtliche Variabilität in Mikroklima und Energiehaushalt Alpiner Zwergstrauchbestände. Verh. Ges. Ökologie Wien 1976, 9–21, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, W.; Brzoska, W.; Zachhuber, K.; Larcher, W. Ergebnisse des IBP-Projekts “Hoher Nebelkogel 3184 m”. Sitzungsber. Oesterr. Akad. Wiss. (Wien) Math. Naturwiss. Kl. Abt. I 1977, 186, 387–419. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, C.; De Moraes, J. A. P. V. Water Potential and Diffusion Resistance in Alpine Cushion Plants on Clear Summer Days. Oecol. Plant. 1979, 14, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, C.; Allison, A.; Hilscher, H. Altitudinal Variation of Leaf Diffusive Conductance and Leaf Anatomy in Heliophytes of Montane New Guinea and Their Interrelation with Microclimate. Flora 1983, 174, 91–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, W. (2003). Physiological Plant Ecology: Ecophysiology and stress physiology of functional group. Verlag, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

- Sierra-Almeida, A. (Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile). Personal Communication, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Falster, D. S.; Westoby, M. Plant Height and Evolutionary Games. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. A review of light interception in plant stands from leaf to canopy in different plant functional types and in species with varying shade tolerance. Ecol. Res. 2010, 25, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenář, P.; Jaramillo, R.; Sivila Wojtasiak, S.; Meneses, R. I.; Muriel, P.; Klimeš, A. Thermal Tolerance of Tropical and Temperate Alpine Plants Suggests That ‘Mountain Passes Are Not Higher in the Tropics’. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2023, 32, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbritter, A. H.; De Boeck, H. J.; Eycott, A. E.; Reinsch, S.; Robinson, D. A.; Vicca, S.; Berauer, B.; et al. The Handbook for Standardized Field and Laboratory Measurements in Terrestrial Climate Change Experiments and Observational Studies (ClimEx). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletz, S. T.; Blonder, B. Leaf Thermal Traits. In The Handbook for Standardised Field and Laboratory Measurements in Terrestrial Climate-Change Experiments and Observational Studies (ClimEx); Halbritter, A. H.; De Boeck, H.; Eycott, A.; Reinsch, S.; Robinson, D. A.; Vicca, S.; Berauer, B.; Christiansen, C. T.; Estiarte, M.; Grunzweig, J. M., Eds.; 2020; pp 450–457.

- Sierra-Almeida, A.; Cavieres, L. A. Summer Freezing Resistance of High-Elevation Plant Species Changes with Ontogeny. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 80, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya-Osses, D.; Casanueva, A.; Román-Figueroa, C.; Uribe, J. M.; Paneque, M. Climate Change Projections of Temperature and Precipitation in Chile Based on Statistical Downscaling. Clim. Dyn. 2020, 54, 4309–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A. M.; Berry, N.; Milner, K. V.; Leigh, A. Water Availability Influences Thermal Safety Margins for Leaves. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 2179–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, K. V.; French, K.; Krix, D. W.; Valenzuela, S. M.; Leigh, A. The Effects of Spring versus Summer Heat Events on Two Arid Zone Plant Species under Field Conditions. Funct. Plant Biol. 2023, 50, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfuentes, C.; Sierra-Almeida, A.; Cavieres, L.A. Effect of the increase in temperature in the photosynthesis of a high-Andean species at two elevations. Gayana Bot. 2012, 69, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N. G.; Sevanto, S. The Mechanisms of Carbon Starvation: How, When, or Does It Even Occur at All? New Phytol. 2010, 186, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S. D.; Ewers, F. W.; Sperry, J. S.; Portwood, K. A.; Crocker, M. C.; Adams, G. C. Shoot Dieback during Prolonged Drought in Ceanothus (Rhamnaceae) Chaparral of California: A Possible Case of Hydraulic Failure. Am. J. Bot. 2002, 89, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyree, M. T.; Vargas, G.; Engelbrecht, B. M.; Kursar, T. A. Drought until Death Do Us Part: A Case Study of the Desiccation-Tolerance of a Tropical Moist Forest Seedling-Tree, Licania platypus (Hemsl.) Fritsch. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M. T. K.; Squeo, F.; Cavieres, L. A.; Marticorena, C. Chilenische Anden. In Gebirge der Erde. Landschaft, Klima, Pflanzenwelt; Burga, C. A., Klötzli, F., Grabherr, G., Eds.; Ulmer GmbH & Co.: Stuttgart, 2004; pp. 210–219. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ferrán, O. Volcanes de Chile; Instituto Geográfico Militar: Santiago, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, H. J.; Murphy, M. D.; Sparks, R. J.; Chávez, R.; Naranjo, J. A.; Dunkley, P. N.; Young, S. R.; Gilbert, J. S.; Pringle, M. R. The Geology of Nevados de Chillán Volcano, Chile. Rev. Geol. Chile 1999, 26, 227–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.; Grau, J.; Baeza, C.; Davies, A. Lista comentada de las plantas vasculares de los Nevados de Chillán, Chile. Gayana Bot. 2008, 65, 153–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfanzelt, S.; Grau, J.; Rodríguez, R. Vegetation mapping of the Nevados de Chillán volcanic complex, Biobío Region, Chile. Gayana Bot. 2008, 65, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Almeida, A.; Aguilera-Torres, C.; Sandoval-Urzúa, C.; Morales, L. V.; González-Concha, D.; Urrutia-Lozano, E.; Marticorena, A.; Teillier, S.; Baeza, C.; Finot, V. Guía de Campo: Plantas de Alta Montaña en el Corredor Biológico Nevados de Chillán-Laguna del Laja; Ediciones Corporación Chilena de la Madera: Concepción, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- González-Concha, D. Diversidad Florística y Funcional en Nevados de Chillán: Importancia del Microclima en Explicar Contrastes entre Laderas; Undergraduate Thesis, Universidad de Concepción: Concepción, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Urtubey, E.; Baeza, C. M.; López-Sepúlveda, P.; König, C.; Samuel, R.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H.; Stuessy, T. F.; Ortiz, M. A.; Talavera, M.; Talavera, S.; Terrab, A.; Ruas, C. F.; Muellner-Riehl, A. N.; Guo, Y. P. Systematics of Hypochaeris Section Phanoderis (Asteraceae, Cichorieae); Syst. Bot. Monogr. 2019, 106, 1–204. [Google Scholar]

- Deginani, N. B. Revisión de las Especies Argentinas del Género Phacelia (Hydrophyllaceae). Darwiniana 1982, 24, 405–496. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. M.; Flores, A. R.; Nicola, M. V.; Marcussen, T. Viola Subgenus Andinium, Preliminary Monograph; Scottish Rock Garden Club with International Rock Gardener: Glasgow, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M.; Calviño, C. I. Nueva Clasificación Infragenérica de Azorella (Apiaceae, Azorelloideae) y Sinopsis del Subgénero Andinae. Darwiniana 2019, 7, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra, M.; Ezcurra, C.; Marticorena, C.; Morrone, J. J.; Roig-Juñent, S.; Roig, F. A.; Aizen, M. A.; Ezcurra, I. Flores de Alta Montaña de los Andes Patagónicos: Guía para el Reconocimiento de las Principales Especies de Plantas Vasculares Altoandinas, 1st ed.; L.O.L.A: Buenos Aires, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A. L. El Género Senecio en Chile. Lilloa 1949, 15, 27–501. [Google Scholar]

- López, A.; Molina-Aiz, F. D.; Valera, D. L.; Peña, A. Determining the Emissivity of the Leaves of Nine Horticultural Crops by Means of Infrared Thermography. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 137, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Determining the Leaf Emissivity of Three Crops by Infrared Thermometry. Sensors (Basel) 2015, 15, 11387–11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrap, M. J. M.; Hempel de Ibarra, N.; Whitney, H. M.; Rands, S. A. Reporting of Thermography Parameters in Biology: A Systematic Review of Thermal Imaging Literature. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 181281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Harguindeguy, N.; Díaz, S.; Garnier, E.; Lavorel, S.; Poorter, H.; Jaureguiberry, P.; Bret-Harte, M.S.; Cornwell, W.K.; Craine, J.M.

- Cook, A. M.; Rezende, E. L.; Petrou, K.; Leigh, A. Beyond a Single Temperature Threshold: Applying a Cumulative Thermal Stress Framework to Plant Heat Tolerance. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, O.; Karadar, M.; Bauer, I.; Neuner, G. A Novel System for In Situ Determination of Heat Tolerance of Plants: First Results on Alpine Dwarf Shrubs. Plant Methods 2013, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G. N. Chlorophyll Fluorescence—A Practical Guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannister, P.; Colhoun, C. M.; Jameson, P. E. The Winter Hardening and Foliar Frost Resistance of Some New Zealand Species of Pittosporum. N. Z. J. Bot. 1995, 33, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, P.; Maegli, T.; Dickinson, K.; Halloy, S.; Knight, A.; Lord, J. Will Loss of Snow Cover during Climatic Warming Expose New Zealand Alpine Plants to Increased Frost Damage? Oecologia 2005, 144, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T.; Zeileis, A.; Farebrother, R. W.; Cummins, C.; Millo, G.; Mitchell, D. lmtest: Testing Linear Regression Models (Version 0.9-34) [R package]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=lmtest.

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Effect | Edf | Red.df | F value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 6.89 | 7.96 | 57.32 | < 2.2e-16 |

| PC2 | 1 | 1 | 2.54 | 0.114 |

| Effect | numDF | denDF | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F value | p-value | Explained variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 1 | 21 | 45.02 | 45.02 | 18.8 | 0.0003 | 23.88% |

| Circularity index | 1 | 21 | 36.21 | 36.21 | 15.12 | 0.0008 | 19.21% |

| Porosity index | 1 | 21 | 2.57 | 2.57 | 1.07 | 0.3123 | 1.36% |

| Height and Circularity index interaction | 1 | 21 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 2.93 | 0.1020 | 3.71% |

| Sampling date | 1 | 21 | 47.44 | 47.44 | 19.82 | 0.0002 | 25.17% |

| Residuals | 21 | - | 50.28 | 2.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).