Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Newtonian mechanics as a linear coherence-drag regime in low-velocity, low-gradient systems;

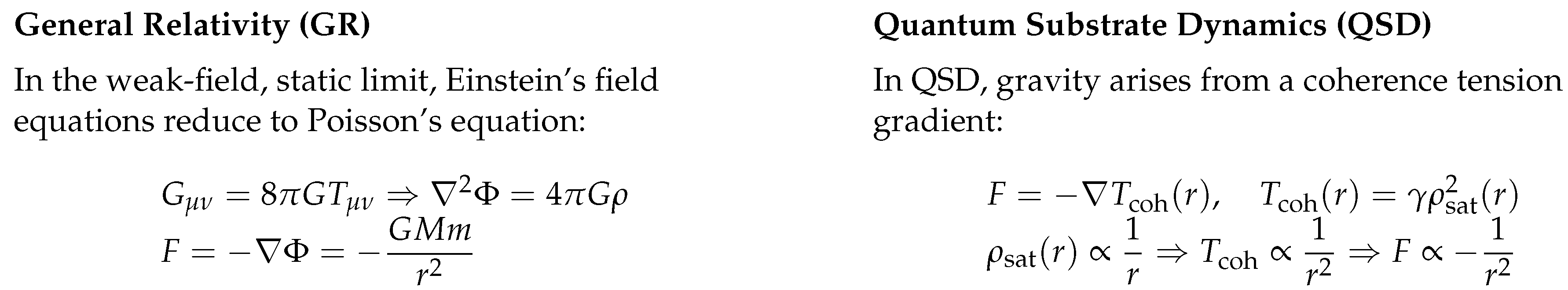

- General Relativity as the macroscopic expression of coherence tension gradients, matching geodesic motion and Einstein field equations;

- Quantum Field Theory as a high-coherence limit with quantized excitation modes corresponding to persistent substrate geometries.

2. Foundational Principles of Quantum Substrate Dynamics

-

Substrate Ontology PrincipleAt the foundation of all physical phenomena is a Lorentz-invariant quantum substrate—a continuous, conserved, coherence-bearing field. This substrate supports all matter, forces, radiation, and time as emergent behaviors of its internal structure. It is not composed of particles, nor embedded in spacetime—it is the source from which spacetime, mass, and energy arise. This is the sole ontological postulate of QSD; all subsequent physical behavior follows as emergent consequence.In this context, coherence refers to the degree of phase alignment and continuity within the substrate’s internal wave structure. High coherence allows stable, low-loss propagation of wave modes; disruptions or gradients in coherence give rise to forces, mass condensation, and radiation.The substrate is not generated from within itself, nor does QSD propose an origin mechanism. Its existence is posited as a foundational condition, parallel to how spacetime is treated in General Relativity or the quantum vacuum in QFT. Just as those frameworks do not explain why spacetime or field structure exists, QSD takes the substrate as the starting point for physical law.

-

Lorentz Invariance of the Substrate PrincipleThe substrate respects Lorentz symmetry. Uniform motion through it is undetectable; only acceleration, coherence disruption, or tension gradients reveal its presence. The observed speed of light c is not an intrinsic constant of spacetime, but emerges from local coherence properties of the substrate. While locally invariant and undetectable in uniform motion, its global value may shift subtly across regions of differing substrate tension—though this variation remains unmeasurable within any single local frame.

-

Conservation of Substrate PrincipleThe substrate is fundamentally conserved. It is neither created nor destroyed—only reconfigured through changes in coherence, phase, or tension. All energetic phenomena arise from the redistribution of the same continuous field.

-

Substrate Equilibrium PrincipleThe quantum substrate continuously reorients to restore local and global coherence equilibrium. It redistributes phase and internal tension to minimize distortion and maintain structural stability. This behavior governs all emergent physical dynamics.

- Coherence Lag Principle — A mass-phase structure undergoing acceleration must reconfigure the coherence flux across its boundary. When acceleration ceases, this flux does not instantaneously stabilize. A brief but physically real coherence lag phase follows, during which residual substrate reconfiguration continues. This lag resolves as the system transitions into flux equilibrium, manifesting as inertial settling or scalar relaxation phenomena. It accounts for experimentally observed nanosecond-scale delays in systems ranging from self-propelled particles[35] to heat flux fields[36], and provides a dynamic extension to the classical notion of motion transition.

-

Substrate Coherence PrincipleAll observable physical phenomena emerge from the coherence structure of the substrate. Coherence gradients, interference, saturation, and restoration drive the formation of mass, forces, time, and radiation.

-

Minimal Deformation PrincipleWhen deformation is required to support mass-phase condensation or wave energy localization, the substrate displaces over the smallest possible region. This minimizes energy cost, confines tension gradients, and leaves distant regions undisturbed unless coherence continuity demands otherwise.

-

Vacuum Equilibrium PrincipleWhat is conventionally called “vacuum” is, in QSD, the substrate in a locally balanced coherence state. This equilibrium condition supports quantum fluctuations and wave excitations without requiring spacetime curvature or matter. The vacuum is not empty—it is coherence-neutral. All field effects arise from deviations from this state.

-

Substrate Energy PrincipleAll energy in QSD arises from internal movements and reconfigurations of the conserved substrate. Energy is not a separate entity, but a manifestation of coherence displacement, tension propagation, or wavefront reorientation within the substrate field . Kinetic, potential, thermal, and radiant energy correspond to specific modes of structured substrate motion or deformation. Rather than existing independently, energy reflects the dynamic state of the substrate as it shifts, compresses, or restores coherence in response to internal or boundary conditions.

-

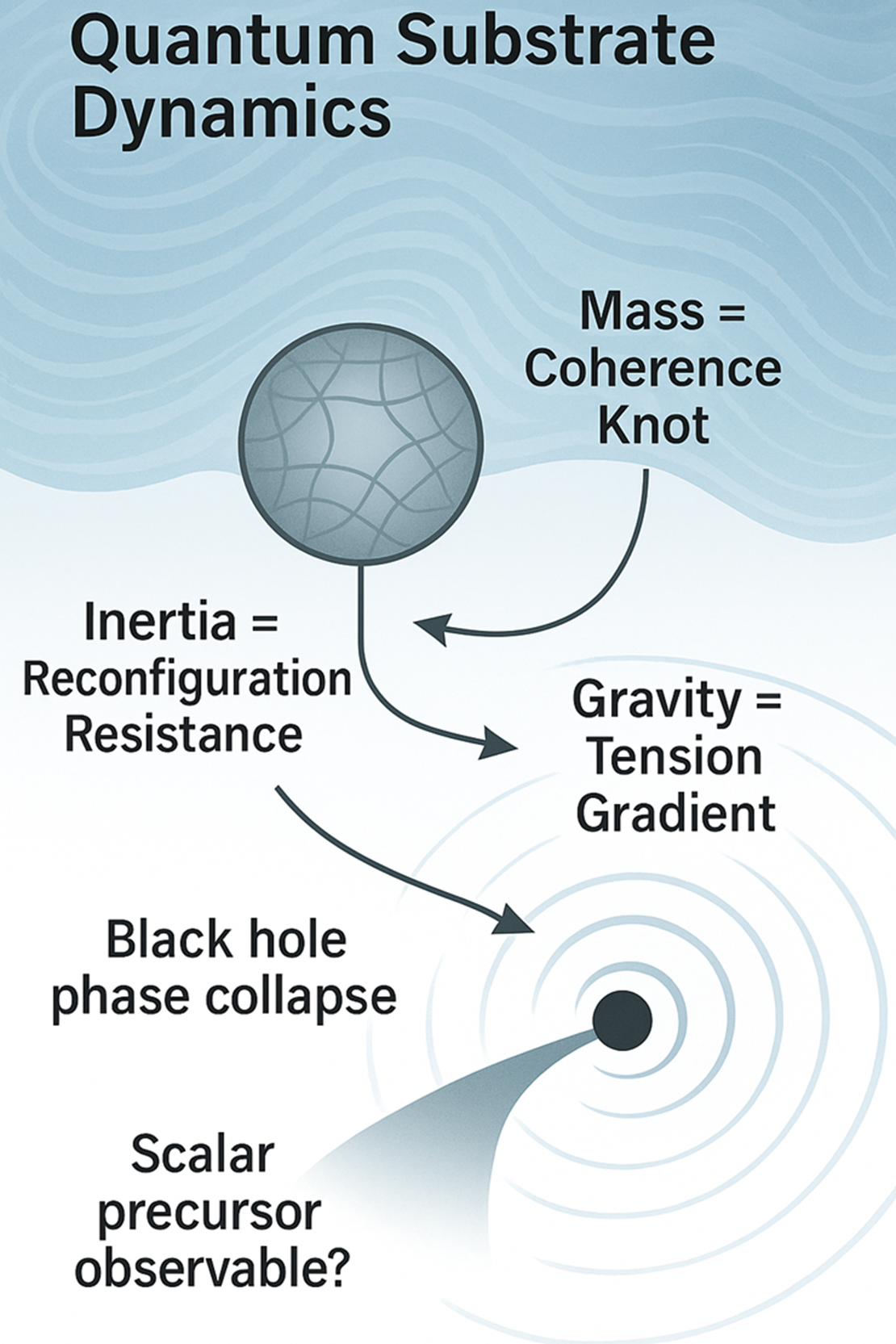

Mass as a Coherence Phase PrincipleMass is a localized, stable condensation of coherence—or a coherence knot—a phase state within the substrate where waveforms saturate and resist deformation. Mass is not substance, but structured tension.

-

Embeddedness PrincipleBecause mass-phase structures are localized coherence configurations within the quantum substrate, they are never isolated. Their existence and behavior are defined by continuous interaction with the surrounding field. All observable motion, inertia, and gravitational response emerge from this embedded condition. The substrate is not a passive background but an active coherence environment, shaping and responding to mass through flux continuity, tension gradients, and reconfiguration resistance. Embeddedness is a structural property of mass, not an external effect.

-

Inertia as Coherence Reconfiguration Resistance (”Inertial Drag”)Inertia is the energetic cost of reconfiguring the substrate boundary as a mass-phase object accelerates. This resistance is shaped by internal geometry, coherence gradients, and scalar interactions.

-

Emergent Quantization PrincipleQuantized mass states arise not from intrinsic discreteness, but from the stability conditions of substrate coherence. The quantum substrate supports a continuous spectrum of curvature configurations, but only certain geometries persist—those that resist reconfiguration. Observable particles correspond to these stable folds, while all other states dissipate as scalar or neutrino emissions or return to the wave phase undetected.

-

Equivalence Principle (Reframed)Gravitational and inertial mass are identical because they both reflect the same coherence-boundary structure. Their equivalence arises naturally from substrate drag and tension geometry.Flux Transition Threshold.As part of this rebalancing behavior, there exists a specific substrate flux value at which reconfiguration resistance vanishes. This threshold marks the transition from active acceleration to stable uniform motion, identifying the point where coherence flux across the mass-phase boundary equalizes. Rather than treating uniform motion as force-free, this defines it as a resolved substrate interaction state. The flux threshold depends on internal structure and coherence resistance, offering a measurable and falsifiable inflection point in the dynamics of motion.

-

Gravity as Tension Gradient Principle (Driven by Substrate Saturation)Gravity is a push force caused by coherence tension gradients. These gradients emerge when regions of high waveform complexity saturate the substrate, drawing in restorative pressure from the surrounding field. What appears as gravitational attraction is actually the substrate pushing inward toward regions of distortion. All forces in QSD arise from tension gradients and equilibrium restoration—not action at a distance.

-

Transverse Wave PrincipleElectromagnetic waves are transverse coherence modes of the quantum substrate. Their propagation speed c arises from the local coherence tension and transverse elasticity of the substrate, and reflects the maximum stable velocity for transverse wavefronts within a coherence-neutral domain.These waves are not fundamental entities, but structured oscillatory states of the substrate’s internal phase geometry. Observable constants such as vacuum permittivity and permeability correspond to local substrate response parameters in the transverse mode regime.While c appears universal, its value is set by substrate properties and may vary across large-scale coherence gradients—though such variation remains unmeasurable within any single inertial frame, preserving Lorentz invariance locally.In this framework, electromagnetic behavior emerges from the same substrate mechanics as scalar and gravitational phenomena. EM fields are coherence structures, not separable forces, and their wave behavior is a specific manifestation of substrate phase continuity under transverse excitation.The observed emission spectrum of transverse waves, such as blackbody radiation, reflects not only temperature but the substrate’s local mass-phase structure, which governs which coherence modes couple to EM radiation and which offload through scalar or non-radiative channels.

-

Scalar Wave PrincipleScalar waves are longitudinal coherence-pressure excitations in the substrate. They propagate independently of charge and can travel through dense or shielded environments. These waves are emitted during rapid substrate reconfiguration. They are variations of the substrate, not in it.

-

Gradient Frame Transition (GFT) PrincipleTransitions between large-scale substrate tension gradient domains produce observable dynamical effects. As mass-phase structures or wavefronts cross between macro-coherence fields, they may experience shifts in inertia, apparent gravitational response, or scalar drag. These transitions may also induce non-Doppler redshifts or blueshifts in propagating light due to phase discontinuities across coherence gradients.Coherence wavefronts—including light—must rephase across domain boundaries. This produces coherence shocks, which can yield measurable anomalies in spectral lines, pulse timing, or inertial balance. Such effects offer testable signals of underlying substrate structure and may explain observed gravitational or spectroscopic anomalies in astrophysical systems.

-

Time as Scalar Propagation Interva PrinciplelTime is not a fundamental background dimension, but a measure of phase displacement. It emerges from the interval between scalar wavefronts propagating through the substrate.

-

Coherence-Coupling Misinterpretation PrincipleWhile implicit in the preceding principles of time, coherence, and wave propagation, this principle is stated explicitly to address a subtle but critical interpretive point.Observed variations in clock rates and light speed under gravitational or inertial conditions reflect paired responses of the quantum substrate to local coherence tension—not deformations of a geometric manifold.In the QSD framework, both time dilation and the bending of light emerge from the same underlying substrate behavior: local modulation of scalar and transverse wave propagation due to coherence gradients. These are not independent changes in time and space, but co-manifestations of tension-induced phase response.

-

Required Recovery and Field Behavior PrincipleQuantum Substrate Dynamics reproduces the known laws of physics under appropriate limits. Newtonian mechanics arises from coherence drag in low-velocity regimes; General Relativity emerges from macroscopic tension gradients; and Quantum Field Theory describes wave-phase excitations in high-coherence, weakly nonlinear domains.In this view, fields traditionally treated as independent—electromagnetic, scalar, gravitational, fermionic—are interpreted as distinct coherence modes of a single, conserved substrate. Their consistent propagation and coupling behavior suggest a common physical origin. QSD does not contradict quantum field theory, but reframes it as an effective description of deeper substrate coherence dynamics. This requirement dictates all known physics must appear as a limiting case of substrate behavior under specific coherence conditions.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. The Substrate Ontology Principle

3.1.1. Mathematical Representation of Coherence.

3.1.2. Physical Consequences.

- Mass: arises as regions of saturated coherence—stable, phase-aligned condensates of the substrate.

- Inertia: results from the energetic cost of deforming or accelerating a coherence-boundary region.

- Forces: emerge as the substrate reorients to minimize internal coherence gradients.

- Time: is defined by the propagation of scalar wavefronts through , tied to substrate response time.

- Spacetime geometry: is a derived effect of substrate curvature and tension, not a primary manifold.

3.2. The Conservation of Substrate Principle

3.2.1. Mathematical Implication.

3.2.2. Physical Interpretation.

- Energy release: Events like particle annihilation or nuclear reactions are not destruction of substance, but reconfiguration of tightly bound substrate coherence into freely propagating wave modes.

- Mass formation: Mass condensation involves local increase in coherence density and tension, drawn from surrounding wave-phase substrate.

- Scalar waves: Emitted scalar waves are phase-pressure responses of the substrate—not external agents—ensuring no net gain or loss of field substance.

3.3. The Substrate Equilibrium Principle

3.3.1. Mathematical Characterization.

3.3.2. Physical Interpretation.

- In low-gradient regions, equilibrium leads to uniform wave-phase behavior and freely propagating excitations.

- Near mass-phase boundaries, tension gradients create restorative push-forces that resemble gravity and inertia.

- During high-gradient events (e.g., collapse, excitation, or decoherence), rapid reconfiguration releases energy in the form of scalar waves or other phase-stabilizing excitations. (For a detailed treatment of scalar emissions, coherence trench dynamics, and black hole merger frustration, see [29].)

Flux Transition Threshold.

3.4. The Minimal Deformation Principle

- is the local substrate tension coefficient,

- is the substrate stiffness (resistance to curvature),

- is a potential governing preferred coherence states (e.g., double-well or nonlinear saturation),

- is the spatial domain over which deformation occurs.

3.5. The Substrate Coherence Principle

3.5.1. Quantifying Coherence Effects.

- The coherence amplitude defines wave stability.

- The phase gradient contributes to local flow and tension.

- The coherence scalar:measures local phase alignment across a neighborhood V.

3.5.2. Emergent Phenomena from Coherence Dynamics.

- Mass formation: occurs when local coherence saturates, locking wave-phase into a stable lattice.

- Forces: arise from coherence gradients, which push or reorient the substrate toward equilibrium.

- Time: is defined by the scalar wave propagation interval through coherent substrate regions.

- Radiation: is the outward propagation of localized coherence disturbances (wavefronts) across the field.

3.5.3. Mathematical Formulation.

3.5.4. Physical Consequences.

- Mass localization: Stable mass-phase structures do not broadly deform the substrate; their influence is contained near their coherence boundary.

- Force locality: Gravitational and inertial forces arise only near mass-phase regions where tension gradients form. Distant substrate regions remain unaffected unless continuity requires participation.

- Scalar emission localization: Energy released during substrate reconfiguration is radiated as localized scalar waves, not distributed broadly, preserving local-global coherence balance.

3.6. The Vacuum Equilibrium Principle

3.6.1. Mathematical Characterization.

3.6.2. Physical Implications.

- Quantum fluctuations: arise as micro-perturbations of phase or amplitude within the vacuum’s coherence field, not as random field insertions but as structured, bounded deviations.

- Wave propagation: coherent wave modes—including electromagnetic, scalar, and neutrino-like excitations—propagate stably through this medium when coherence remains high.

- Field emergence: all observable fields (EM, gravitational, etc.) are expressions of local departures from vacuum coherence. No separate background geometry is required.

3.7. Substrate Energy Principle

Energy as Substrate Reconfiguration

- Kinetic energy corresponds to the continuous reorientation of the substrate’s coherence field around a moving mass-phase object. The faster the motion, the greater the rate of phase reconfiguration at the object’s boundary, increasing substrate tension and internal wavefront disruption.

- Potential energy represents stored coherence tension due to substrate gradients. In a gravitational field, for example, a mass-phase structure placed in a region of higher substrate tension gradient possesses increased potential energy because its stable configuration requires greater rebalancing effort from the surrounding field.

- Thermal energy arises from incoherent or semi-coherent oscillations within the substrate near a mass-phase structure. These small-scale fluctuations represent persistent, high-frequency reconfigurations that fail to achieve long-range phase alignment, yet contribute net tension and offload pressure.

- Radiant energy (e.g., electromagnetic or scalar wave propagation) is the transport of phase disturbance through the substrate, either in transverse or longitudinal modes. These are coherence wavefronts detached from their source, preserving structured phase information across spacetime.

3.7.1. Substrate Dynamics and Energy Flow

Unified Interpretation

3.8. Mass as a Coherence Phase Principle

3.8.1. Phase Locking and Stability.

3.8.2. Energetic Implications.

3.8.3. Connection to Observables.

3.8.4. Physical Consequences.

- Mass persistence: The structured coherence of a mass-phase region resists deformation and disruption, giving rise to inertial effects and long-term stability. Acceleration requires work against this boundary coherence.

- Mass-energy equivalence: The stored tension within a coherence lattice can be released as wave-phase energy. The relation emerges as a reconfiguration identity: coherent energy transforms to traveling waves during annihilation or decay, not as annihilation of substance but as release of structure.

- Quantized states: Only certain lattice geometries remain stable under substrate tension—mass quantization arises from coherence persistence, not from intrinsic discreteness.

- Particle interpretation: What we call “particles” are coherence-phase solitons—localized, metastable, reconfigurable field structures shaped by substrate tension. Their properties emerge from geometry and coupling, not from substance.

3.8.5. Conceptual Summary

3.9. Embeddedness Principle

Implications

- Inertia arises not from intrinsic mass, but from resistance to altering substrate flux through the embedded structure.

- Gravity is a local flux asymmetry—not a geometric property—arising from mass-phase deformation of the surrounding field.

- Scalar wave emission, flux threshold stabilization, and coherence lag all require the object to be embedded and interacting with its local coherence gradient.

Contrast with Classical Mass

3.10. Inertia as Coherence Reconfiguration Resistance Principle (“Inertial Drag”)

3.10.1. Quantitative Framework.

3.10.2. Inertial Mass from Gradient Shell Reconfiguration.

3.10.3. Variational Formulation and Least Action.

3.10.4. Dimensional Analysis of Inertial Drag in the Substrate

3.10.5. Key Contributions to Inertial Resistance.

- Internal waveform geometry: Fine-grained or structured coherence topologies create more surface variation in the gradient zone, increasing reconfiguration energy.

- Coherence gradients: Steeper transitions between wave and mass phase (i.e., sharper phase boundaries) raise and , amplifying drag response.

- Scalar coupling: At high accelerations or under nonlinear excitation, coherence disruption may radiate scalar waves, producing dissipative back-reaction and measurable phase lag.

3.10.6. Implications and Predictions.

- Variable inertia: Objects with the same rest mass but different internal coherence geometries (e.g., solid vs. nanoporous structures) may exhibit differing inertial resistance.

- Nonlinear acceleration response: Inertial drag is expected to become nonlinear at high acceleration gradients, possibly showing threshold discontinuities or emission-induced phase shifts.

- Experimental testability: Structure-sensitive inertia predicted by QSD could be probed using torsion balances, drop-tower experiments, or space-based interferometry to detect coherence-dependent inertial deviations.

3.10.7. Conceptual Summary.

3.11. The Emergent Quantization Principle

- fail to maintain structural coherence,

- radiate excess tension through scalar or neutrino emission,

- or dissolve back into the wave-phase substrate.

3.12. Substrate Flux Equilibrium Principle

3.12.1. Flux-Balance Model.

3.12.2. Physical Implications.

- Acceleration without force: Acceleration is the substrate’s way of resolving flux imbalance—reconfiguring the position of the mass-phase to restore coherent flow.

- Frame-dependent motion: Uniform motion is only maintained in locally flat coherence conditions; gradients demand motion adjustments to preserve flux balance.

- Inertia-flux connection: Inertia becomes the substrate’s resistance to rapid flux change, modulated by coherence geometry and internal boundary complexity.

3.12.3. Observational and Conceptual Shifts.

- Reframes Newton’s Second Law: becomes a consequence of flux imbalance, not a primary law.

- Enables acceleration prediction: Direction and magnitude of acceleration can be derived from substrate coherence tension gradients.

- Clarifies interaction origin: Apparent forces are flow-maintaining corrections, not independent physical entities.

3.13. Coherence Lag Principle

Predictive Formulation.

- is the effective characteristic length across which the substrate must reconfigure,

- is the substrate’s scalar or coherence wave propagation speed,

- is a dimensionless coefficient that encodes the object’s internal coherence resistance (e.g., structural complexity, density, lattice configuration).

Empirical Anchors.

- In macroscopic systems, this coherence lag is exemplified by inertial delay in self-propelled particles, where velocity trails behind orientation during active motion [35].

- In field systems, finite response time in heat conduction under acceleration—contradicting the assumptions of instantaneous Fourier flux—is consistent with coherence flux relaxation [36].

3.14. Equivalence Principle (Reframed)

- Inertia: resistance to acceleration due to coherence-boundary reconfiguration,

- Gravity: substrate tension gradients that arise from coherence saturation.

3.14.1. Unified Drag and Tension Model.

3.14.2. Physical Implications.

- No postulate required: The equivalence principle is not an assumed symmetry, but a derived outcome of how the substrate resists and transmits coherence deformation.

- Predictive capacity: Variations in internal structure or coherence coupling may subtly affect both inertial and gravitational response, offering measurable deviations from strict equivalence under extreme conditions.

- Unified interpretation: Inertia and gravity become two expressions of the same substrate response mechanism—one local (drag), the other extended (tension).

3.15. Gravity as Tension Gradient Principle

3.15.1. Tension and Conservation.

3.15.2. Apparent Gravitational Phenomena.

- Push from flux conservation: In QSD, what appears as gravitational attraction is the result of coherence flux imbalance. As a mass-phase structure follows coherence toward a nearby tension minimum, the reaction to this flux imbalance imparts a push—driving the structure along the gradient. The force is local and directional, not remote.

- Apparent curvature: Trajectories of particles and wavefronts curve as they follow the gradient of least coherence distortion—mimicking general relativistic geodesics.

- Mass aggregation: Over time, this coherent flow reinforces mass concentrations, explaining gravitational stability and clustering without invoking attraction at a distance.

3.15.3. Subtle Variability of Gravitational Strength.

3.15.4. Experimental Alignment and Predictions.

- Reproduces all weak-field tests of General Relativity (precession, lensing, redshift) via coherence-tension gradients.

- Predicts scalar wave precursors and coherence collapse effects in high-density collapse events (e.g., black holes, neutron stars).

- Offers an explanation for apparent gravitational constant variability in complex multi-body systems.

3.16. Transverse Wave Principle

Waveform Structure and Propagation Speed

Relation to Classical Electromagnetism

Local Invariance and Gradient Effects

Interpretation and Implications

- EM fields are not separate ontological entities, but phase modes of the substrate.

- Light propagation reflects substrate coherence, not empty-space invariance.

- Scalar and EM waves differ only in excitation geometry—longitudinal vs. transverse.

- The apparent universality of c is a consequence of the uniform substrate properties in low-curvature domains.

3.17. Scalar Wave Principle

3.17.1. Mathematical Form.

- is the scalar wave propagation speed,

- is an effective potential (e.g., double-well or sine-Gordon form),

- is a coupling coefficient to local compression or tension.

3.18. Dimensional Estimate of Scalar Wave Emission

3.18.1. Emission Conditions.

- Rapid coherence collapse, such as near black hole boundaries or supernova shock fronts,

- High-gradient reconfiguration events, e.g., lattice destruction or inertial thresholds,

- Nonlinear transitions across mass-phase or coherence-boundary domains.

3.18.2. Nucleation and Phase Creation.

3.18.3. Physical Properties.

- Charge-independent: Scalar waves do not require coupling to electric charge or current—they propagate directly as fluidic coherence shifts.

- Penetrating: They can travel through dense or shielded regions that block electromagnetic or neutrino radiation.

- Superluminal appearance: Because scalar coherence changes precede wavefront recombination, they may appear to arrive before conventional signals—but without violating causality, as they carry no encoded information faster than c.

3.18.4. Observational Relevance.

- Supernova precursor neutrino–photon gaps,

- Gravitational anomalies in high-density collapse zones,

- Coherence-related energy emissions in unexplained burst events.

3.19. Gradient Frame Transition (GFT) Principle

3.19.1. Coherence Shock at Domain Boundaries.

3.19.2. Predicted GFT Effects.

- Inertial anomalies: Shifts in effective mass or resistance during planetary flybys or orbital regime transitions.

- Spectral rephasing: Non-Doppler redshift or blueshift of light crossing field boundaries (e.g., at galactic voids or halo edges).

- Scalar bursts: Coherence-front corrections may emit transient scalar pulses analogous to coherence relaxation fronts.

3.19.3. Wave Conservation Across Gradient Frames.

3.19.4. Conceptual Significance.

3.20. Time as Scalar Propagation Interval

3.20.1. Scalar Timing Definition.

- is the scalar wave propagation speed,

- is the coherence path length between scalar fronts,

- Local tension or coherence distortion modifies , thereby altering the experienced time interval.

3.20.2. Emergent Time Effects.

- Time dilation: In high-tension or coherence-saturated zones, scalar wavefront spacing stretches, producing slower local progression of time—analogous to gravitational time dilation.

- Relativity recovery: The invariance of scalar wavefront propagation across local Lorentz frames naturally reproduces time relativity effects without requiring a geometric time axis.

- Directional continuity: Because scalar wavefronts propagate forward, time inherits a consistent arrow—rooted in the relaxation of coherence tension gradients.

3.20.3. Conceptual Implications.

3.21. The Coherence-Coupling Misinterpretation Principle

Interpretive Note: General Relativity (GR) accurately predicts and describes the empirical relationships between motion, gravity, and measured time, but does so without reference to a physical substrate. As a result, it interprets tension-induced delays and deflections as geometric curvature. QSD retains full compatibility with GR’s observational predictions, but reframes the cause as a substrate-based modulation of phase propagation. The apparent curvature of spacetime is thus an interpretive mirage—a geometric mapping of substrate coherence behavior.

3.22. Required Recovery and Field Behavior Principle

3.22.1. Field Unification through Coherence Modes.

- Electromagnetic fields: Phase-coherent transverse waves with charge coupling,

- Gravitational phenomena: Large-scale coherence-tension gradients,

- Scalar waves: Longitudinal coherence-pressure disturbances,

- Fermionic modes: Localized coherence envelopes with rotational symmetry (spin).

3.22.2. Limiting Behavior and Compatibility.

- In the low-velocity, high-coherence limit, substrate drag behaves linearly, yielding Newtonian dynamics.

- In the macroscopic limit, coherence tension gradients mimic spacetime curvature as described in General Relativity.

- In the quantized, weakly nonlinear limit, the substrate supports discrete excitation spectra matching Quantum Field Theory.

Experimental and Theoretical Implications

- Measurable threshold transitions: Experiments can detect explicit critical thresholds for nonlinear coherence boundary effects, analogous to turbulence transitions in classical fluids or critical velocities in BEC systems.

- Tunable inertial effects: Manipulating coherence structure, internal geometry, or boundary conditions can alter effective Quantum Reynolds numbers, allowing experimental tuning or engineering of coherent inertial responses.

- Direct coherence-boundary observations: Measuring inertial resistance anomalies as functions of internal coherence structure, scalar-wave interactions, or coherence-boundary deformation rates validates QSD’s explicit coherence-based inertia predictions.

3.23. Superfluid Analogues and Zero-Resistance Phenomena

3.24. Recovery of Newtonian Mechanics at Low Velocities

4. Field Recovery and Compatibility

4.1. Newtonian Mechanics as Low-Gradient Substrate Drag

4.2. General Relativity from Coherence Tension Gradients

4.3. Quantum Field Theory as High-Coherence Wave Behavior

4.4. Substrate Mode Correspondence with Classical Fields

- Electromagnetic fields: Transverse coherence waves with vector phase polarization.

- Scalar fields: Longitudinal phase-pressure excitations (see Section 3.17).

- Gravitational fields: Macroscopic gradients in coherence tension.

- Fermionic fields: Coherence-knot excitations with internal spin phase geometry.

4.5. Requisite Field Compatibility

- Newtonian mechanics from linear drag behavior at low substrate gradients,

- General Relativity from macroscopic coherence tension gradients,

- Quantum Field Theory from stable excitation spectra in high-coherence, weakly nonlinear domains.

5. Key Predictions and Falsifiability

5.1. Scalar Wave Precursors in Collapse Events

5.2. Off-Spectrum Neutrinos as Coherence Reconfiguration Emissions

Characteristics and Experimental Implications

- Each neutrino flavor corresponds to a distinct curvature envelope, determined by the degree of incomplete folding.

- QSD allows for a spectrum of such modes—potentially far more than the three known neutrino types.

- Many of these off-spectrum modes would interact only gravitationally or via coherence tension, rendering them undetectable by conventional weak-interaction methods.

- Sterile or anomalous neutrino detections in astrophysical timing or oscillation studies could be signatures of these failed-fold coherence emissions.

- Their energy spectrum may encode the gap between elemental nucleation thresholds, particularly during supernova shell formation.

5.3. Geometry-Dependent Inertial Anomalies

5.4. Gravitational Anomalies from Gradient Frame Transitions

- Apparent changes in inertial or gravitational coupling,

- Non-Doppler redshifts or blueshifts,

- Scalar emission signatures at coherence boundaries.

5.5. Substrate-Origin Redshift Variations

5.6. Energy Extraction During Coherence Collapse

- Scalar wave bursts or compression rings near collapse fronts,

- Anomalous neutrino emission profiles with flavor-state transitions tied to matter layering,

- Elemental shell stratification in supernova remnants, matching coherence phase boundaries.

Falsifiability Criteria

- Failure to observe scalar wave precursors in rapid collapse events, where coherence reconfiguration and pre-photonic energy release should dominate.

- Absence of inertial deviations in highly structured versus homogeneous materials, where internal coherence geometry is predicted to modulate boundary drag.

- Strict adherence to classical Doppler or relativistic redshift behavior across suspected Gradient Frame Transition (GFT) boundaries, with no coherence-related rephasing shifts.

- No evidence of coherence-origin energy release during high-tension transitions, such as quantized nucleation cascades or neutrino-envelope offloading in supernovae or analogous collapse systems.

6. Experimental and Observational Opportunities

6.1. Geometry-Dependent Inertia Tests

- Precision torsion pendulum or interferometric drop tests comparing structured vs. unstructured masses.

- Oscillating platforms measuring phase lag or energy dissipation in response to driven acceleration.

- Space-based microgravity environments for isolating coherence-bound inertial drag effects.

6.2. Scalar Wave Detection and Collapse Precursors

- Time-resolved neutrino–photon–scalar arrival sequences in supernovae, focusing on early-stage bursts.

- Laboratory coherence-breakdown experiments using high-tension lattice collapse (e.g., shocked crystal targets or piezoelectric deformation).

- Analysis of transient scalar-correlated signals near black hole boundaries or neutron star crust failures.

6.3. Gradient Frame Transition (GFT) Signature Surveys

- Analysis of gravitational flyby anomalies using spacecraft telemetry in regions near planetary coherence boundaries.

- High-resolution redshift surveys across galactic voids and cluster peripheries to detect coherence rephasing effects.

- Gravitational lensing comparisons between scalar-transparent and EM-transparent structures.

6.4. Neutrino Envelope Transitions in Nucleation Cascades

- Long-baseline neutrino timing analyses correlated with elemental layering in supernova remnants.

- Lab-scale nucleation energy tests in dense matter under rapid compression or phase shift.

6.5. Optical Phase Shift Experiments in Structured Media

- Fabry–Pérot or Mach–Zehnder interferometry in materials under coherence gradient stress.

- Reflection or transmission anomalies near predicted scalar resonance thresholds.

Integration with Existing Instruments

- Neutrino observatories (IceCube, Super-Kamiokande) for flavor-phase signatures.

- Gravitational wave detectors (LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA) for pre-event scalar coupling or anomalous burst correlations.

- Deep-space probes and inertial guidance data from past flybys.

- Synchrotron beamlines or ultrafast optical setups for lattice collapse or structured mass oscillation.

7. Discussion

7.1. Relation to General Relativity and Quantum Field Theory

7.2. Comparison with Emergent and Analog Gravity Models

7.3. Emergent Gravity Models: Comparative Analysis

7.4. Conceptual Clarifications: Mass, Inertia, and Time

- Mass is not intrinsic substance, but a stable phase-condensed lattice within the substrate.

- Inertia arises from the energetic cost of reconfiguring the mass-phase boundary under acceleration.

- Time is not a geometric dimension but a phase interval between scalar wavefronts propagating through the substrate.

8. Future Scope and Limitations

9. Future Theoretical and Experimental Directions

- Formal derivations of gauge symmetry from substrate phase structure,

- Nonlinear simulations of coherence collapse and scalar wave coupling,

- Integration with condensed matter experiments and scalar analog models,

- Cosmological modeling of coherence tension gradients and early-universe nucleation sequences.

Materials and Methods

- Clarifying technical phrasing and improving narrative clarity,

- Verifying internal consistency of definitions, terminology, and mathematical structure,

- Suggesting appropriate LaTeX formatting and document structuring,

- Cross-referencing related scientific concepts to aid contextualization,

- Summarizing and formatting external source material already selected by the author.

Conclusion

Statements and Declarations

Funding:

Competing Interests:

Author Contributions:

Data Availability:

Ethical Approval:

Conflicts of Interest:

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Lagrangian Density of the Substrate Field

- Preserve global coherence conservation (Principle III),

- Minimize spatial deformation and curvature under coherence stress (Principle VI),

- Support nonlinear condensation and stable mass-phase locking (Principle VIII),

- Reproduce scalar wave propagation and inertial resistance (Principles IX, XIV),

- Admit known field theories as limiting cases.

- The amplitude term governs scalar wave propagation,

- The phase term models inertial drag and momentum flow,

- The curvature penalty enforces local coherence economy,

- The nonlinear potential enables mass condensation and phase stability.

Limiting Case Reductions of the QSD Lagrangian

| Limiting Case | Simplifying Assumptions | Resulting Lagrangian or Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Gross–Pitaevskii Equation (BECs) | Non-relativistic approximation, negligible curvature term , slow amplitude variation | Phase-dominant kinetic term drives dynamics. Matches the GPE used in condensate evolution. |

| Ginzburg–Landau Equation (Superconductivity) | Static (time-independent) fields, real , curvature resistance ignored | Reduces to: , the canonical Ginzburg–Landau free energy density. |

| Nonlinear Klein–Gordon / Higgs Field | Real scalar field , relativistic treatment, curvature term dropped | Matches: , the standard symmetry-breaking scalar field Lagrangian. |

| Phase Field Models (Materials Science) | Replace (dissipative dynamics), real field , retain curvature penalty | Becomes the phase-field energy functional: , used for boundary motion, domain wall formation, and pattern evolution. |

Appendix A.1.1 Global Action and Field Evolution of the Substrate

- Integrate the local Lagrangian density across all space and time to capture substrate evolution,

- Preserve Lorentz invariance in the full action functional,

- Generate the governing field equation via the principle of least action,

- Embed the substrate principles of coherence conservation and deformation economy.

Global Lagrangian and Action Functional

- Scalar wave propagation in low-tension domains,

- Inertial response and phase drag via the term,

- Localized coherence stabilization through the nonlinear potential,

- Structural resistance via higher-order stiffness (),

- Full Lorentz invariance and substrate conservation through Lagrangian derivation.

Limiting Case Reductions of the QSD Substrate Equation

| Limiting Case | Assumptions Applied | Resulting Model |

|---|---|---|

| Gross–Pitaevskii Equation (BECs) | Non-relativistic limit (), slow amplitude variation, drop curvature () | |

| Ginzburg–Landau Equation | Time-independence, real scalar field (), curvature resistance ignored | |

| Nonlinear Klein–Gordon / Higgs Field | Real scalar field, relativistic treatment, drop curvature term | |

| Phase Field Models | Replace , retain , real scalar field | |

| Dispersive Wave Equations | Drop nonlinear potential (), real scalar field, retain and terms |

Interpretation and Role in QSD

Appendix A.2. Governing Substrate Field Equation

- Conserve the total substrate coherence amplitude (Principle III),

- Minimize spatial deformation and curvature under coherence stress (Principle VI),

- Support nonlinear self-locking and phase-bound stability (Principle VIII),

- Enable scalar wave propagation and coherence collapse (Principles IX, XIV),

- Remain Lorentz-invariant and recover known physics in appropriate limits (Principle XVII).

- : Substrate tension coefficient (resistance to gradient stress),

- : Substrate stiffness (resistance to curvature),

- : Nonlinear potential representing mass-phase saturation.

Limiting Case Reductions of the QSD Field Equation

| Limiting Case | Simplifying Assumptions | Resulting Equation or Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Gross–Pitaevskii Equation (BEC) | Non-relativistic limit , small amplitude variation , drop curvature term () | |

| Ginzburg–Landau Equation | Time-independence, real field , no curvature resistance | |

| Nonlinear Klein–Gordon / Higgs Field | Real scalar field, relativistic dynamics, drop | |

| Phase Field Evolution (Materials Science) | Replace , real scalar field, retain curvature penalty | |

| Dispersive Fluid Waves | Drop nonlinear potential (), real scalar field, retain and terms |

Interpretation and Role in QSD

- Scalar and neutrino emissions arise from rapid local reconfiguration,

- Mass-phase knots emerge as stable minima of the substrate potential,

- Inertia arises from the cost of reconfiguring ,

- Field theories like GL, GPE, KG, and phase models are special cases of substrate dynamics.

Appendix A.2.1 Unified Substrate Dynamics Equation

- is the quantum pressure,

- captures gradient tension from substrate deformation,

- represents feedback from scalar compression fields,

- and describe boundary and internal lattice dynamics.

Appendix A.3. Transverse Phase Wave Equation in QSD

Euler–Lagrange Derivation

Physical Interpretation in QSD

- Transverse waves are not fundamental fields but coherence structures,

- The propagation speed c arises from local substrate tension and phase elasticity,

- The wavefront travels orthogonal to , with speed determined by , where is the transverse coherence tension.

Role in QSD Framework

- Scalar wave equation: describes longitudinal compressional dynamics tied to coherence-pressure release, such as neutrino emissions and supernova precursors.

- Transverse wave equation: governs phase-shear propagation, corresponding to electromagnetic radiation and transverse coherence modes.

Appendix A.4. Scalar Wave Equation Derivation

Appendix A.5. Quantitative Substrate Dynamics in SN 1987A-like Events

Appendix A.5.1. Motivation and Scope

Appendix A.5.2. Scalar–Neutrino Delay Framework

Appendix A.5.3. Core Slip as Substrate Yielding

Exhaustion and Substrate Re-seeding

Appendix A.5.4. Action Principle and Stability Transition

Appendix A.5.5. Observational Signature Predictions

Appendix A.5.6. Summary

Appendix A.6. Superfluid Analogues, Zero-Resistance, and Mathematical Framework

Appendix A.6.1. Conceptual Basis of Universal Coherence and Inertial Decoupling

Appendix A.6.2. Madelung Representation and Zero-Resistance Conditions

- Irrotational Flow: Coherence-based velocity fields are irrotational (), reducing internal shear and vortex-induced drag, crucial for inertial decoupling.

- Boundary Coherence Matching: When an object’s velocity matches the substrate’s coherence velocity exactly, coherence-boundary friction vanishes:

- Quantum Pressure and Stability: Quantum pressure, emerging from coherence density gradients, prevents coherence collapse and maintains structural stability, allowing sustained zero-resistance conditions.

Appendix A.6.3. Broader Implications and Relevance

- Cosmic-Scale Coherence: Extending zero-resistance phenomena observed in condensed matter systems to astrophysical and cosmological scales offers a coherent explanation for inertia and gravitational coupling.

- Technological Potential: Realizing inertial decoupling through engineered coherence states could inspire novel propulsion methods and inertial manipulation technologies, such as coherent boundary "shock bubbles" or vortex-mediated systems.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Collaboration with quantum hydrodynamics specialists could significantly advance theoretical rigor, mathematical consistency, and empirical testing of QSD’s coherence-based hypotheses.

Appendix A.7. Newtonian Recovery and Quantum Pressure

Appendix A.7.1. Derivation of Newtonian Limit from QSD

Appendix A.8. Binary Orbit QSD/GR Comparison

Appendix A.9. Coherence Wave Modes

| Feature | Transverse Waves (EM) | Scalar Waves (Longitudinal) |

|---|---|---|

| Propagation Direction | Orthogonal to oscillation plane | Aligned with oscillation direction |

| Wave Type | Transverse coherence oscillation | Longitudinal compression/rarefaction |

| Physical Origin | Oscillatory tension in transverse coherence geometry | Pressure pulse in coherence density (phase pressure) |

| Emergent Speed | , may differ from c | |

| Charge Coupling | Strongly coupled to electric charge | Independent of charge; neutral mass-phase coupling |

| Propagation Medium | Requires coherent transverse tension | Supported in any compressible coherent substrate |

| Shielding Behavior | Blocked or absorbed by conductive materials | Can pass through dense or shielded environments |

| Analogous System | Electromagnetic waves in vacuum | Sound or pressure waves in fluids |

| Emission Source | Oscillatory boundary current or phase-excitation | Substrate reconfiguration or coherence collapse |

| Observational Role | Light, radio, gamma radiation | Neutrinos, scalar precursors, coherence shocks |

| Substrate Signature | Lateral phase tension modulation | Compression front with scalar pressure spike |

Appendix A.10. Empirical Anomalies Addressed by QSD

| Anomaly | Conventional View | QSD Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Flyby anomaly | Unexplained energy shifts in spacecraft during planetary flybys; not predicted by GR or Newtonian mechanics. | Arises from geometry-sensitive inertial drag due to coherence gradients in Earth’s substrate field. Inertial mass varies with coherence structure. |

| Off-pattern shell nucleation | Supernova remnants show element shells inconsistent with fusion energy deposition or standard hydrodynamics. | Mass-phase nucleation thresholds depend on scalar tension fronts, not just thermal expansion—yielding quantized element layers at coherence transition zones. |

| Scalar precursors | Some astrophysical events show signals preceding light or neutrinos; lacks explanation in GR or QFT. | QSD predicts scalar (longitudinal) coherence waves that propagate ahead of light as substrate compression fronts. |

| LIGO ringdown echoes | Residual oscillations after black hole mergers poorly matched by GR models; debated as noise. | Predicted as vibrational rebound or trench-mode relaxation of metastable dual-core coherence geometries following merger frustration. |

Appendix A.11. Falsification Scenarios and Test Designs

| Prediction | Test Method | Competing Models | Distinguishing Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scalar–neutrino delay (2–3 s) | Supernova timing with neutrino observatories [31,32,33] | GR/QFT | Early photomultiplier signal or scalar pulse preceding neutrinos |

| Variable inertia by geometry | Drop towers, torsion pendulums, microgravity platforms | None | Mass-equivalent samples with differing coherence topology exhibit inertial variation |

| Coherence trench burst behavior | Gravitational wave tail analysis via LISA [34] | GR | Scalar-mode ringdown echoes post-merger beyond tensor-only predictions |

| Substrate shear profile deviations | Flyby anomaly tracking, precision orbital dynamics | GR | Non-Keplerian deviations matching predicted substrate gradients |

References

- Einstein, A. On the electrodynamics of moving bodies. Annalen der Physik 1905, 322, 891–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1915). The field equations of gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Minkowski, H. Raum und Zeit. Physikalische Zeitschrift 1908, 10, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- van derWaals, J.D. (1873). Over de Continuiteit van den Gas- en Vloeistoftoestand. Leiden University.

- Kapitza, P. Viscosity of Liquid Helium II. Nature 1938, 141, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.F.; Misener, A.D. Flow of Liquid Helium II. Nature 1938, 141, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D. The theory of superfluidity of helium II. Journal of Physics USSR 1941, 5, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. Soviet Physics Doklady 1967, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Volovik, G.E. (2003). The Universe in a Helium Droplet. Oxford University Press.

- Visser, M. Acoustic black holes: Horizons, ergospheres, and Hawking radiation. Classical and Quantum Gravity 1998, 15, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A suggested interpretation of quantum theory in terms of “hidden” variables. Physical Review 1952, 85, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G. Experimental black-hole evaporation? Physical Review Letters 1981, 46, 1351–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesla, N. (1900). The Problem of Increasing Human Energy. The Century Magazine, June issue. [Cited for historical inspiration only.].

- Madelung, E. Quantum theory in hydrodynamic form. Zeitschrift fur Physik 1927, 40, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.H.; Ensher, J.R.; Matthews, M.R.; Wieman, C.E.; Cornell, E.A. Observation of Bose-Einstein Condensation in a Dilute Atomic Vapor. Science 1995, 269, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pethick, C.J.; Smith, H. (2002). Bose–Einstein Condensation in Dilute Gases. Cambridge University Press.

- Wen, X.-G. (2004). Quantum Field Theory of Many-Body Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Reynolds, O. An experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 1883, 174, 935–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenghi, C.F.; Skrbek, L.; Sreenivasan, K.R. Introduction to quantum turbulence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111 (Suppl. 1), 4647–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinen, W.F. Mutual friction in a heat current in liquid helium II. I. Experiments on steady heat currents. Proceedings of the Royal Society A 1957, 240, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Application of quantum mechanics to liquid helium. Progress in Low Temperature Physics 1955, 1, 17–53. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, R.J. (1991). Quantized Vortices in Helium II. Cambridge University Press.

- Whitby, M.; Quirke, N. Enhanced fluid flow through nanoscale carbon pipes. Nature Nanotechnology 2007, 2, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruus, H. (2008). Theoretical microfluidics. Oxford University Press.

- Bocquet, L.; Charlaix, E. Nanofluidics, from bulk to interfaces. Chemical Society Reviews 2010, 39, 1073–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, C.; Kohl, M.; Onofrio, R.; Durfee, D.S.; Kuklewicz, C.E.; Hadzibabic, Z.; Ketterle, W. Evidence for a Critical Velocity in a Bose–Einstein Condensed Gas. Physical Review Letters 1999, 83, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrio, R.; Raman, C.; Vogels, J.M.; Abo-Shaeer, J.R.; Chikkatur, A.P.; Ketterle, W. Observation of Superfluid Flow in a Bose–Einstein Condensed Gas. Physical Review Letters 2000, 85, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M. (2025). Black Hole Merger Frustration in QSD: A Physically-Constrained Model for Jet Genesis, Scalar Emission, and Residual Dynamics. Research Square, preprint. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Equipartition of energy in the horizon degrees of freedom and the emergence of gravity. Modern Physics Letters A 2010, 25, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, K.; et al. Observation of a Neutrino Burst from the Supernova SN1987A. Physical Review Letters 1987, 58, 1490–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aartsen, M.G.; et al. Evidence for High-Energy Extraterrestrial Neutrinos at the IceCube Detector. Science 2013, 342, 1242856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; et al. Hyper-Kamiokande Design Report. Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics 2023, 2023, 043F01. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro-Seoane, P.; et al. (2017). Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. arXiv:1702.00786 [astro-ph.IM].

- Scholz, C.; Kruger, S.J.; Stark, H. Inertial delay of self-propelled particles. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.R. Heat Conduction with AccelerationWaves. C 2016, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D.; Hiley, B.J. (1993). The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory. Routledge, London.

- Dvali, G.; Gomez, C. Black Hole’s Quantum N-Portrait. Fortschritte der Physik 2013, 61, 742–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.M. (2016). Why Is There Something, Rather Than Nothing? In K. Chamcham, J. Silk, J.D. Barrow, S. Saunders (Eds.), The Philosophy of Cosmology (pp. 265–286). Cambridge University Press. https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.00850.

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Physical Review Letters 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.; Zeh, H.D. Arrow of time in a recollapsing quantum universe. Physical Review D 2007, 76, 064003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).