1. Introduction

It is commonly assumed that nothing can move faster than the speed of light [

1]. However, the theory of relativity [

1] does not rule out faster-than light travel [

2,

3,

4]. Nonetheless, something that moves slower than light cannot be accelerated to faster than the speed of light and something that moves faster than the speed of light cannot be slowed to below the speed of light because the energy required is infinite as explained later. The speed of light is a barrier from both sides of the divide.

There is a discrepancy between the amount of observed matter in the universe and gravitational attraction on a large scale that is widely assumed to be caused by dark matter [

5,

6,

7,

8] and dark energy [

9] that does not interact via light or other electromagnetic radiation but only gravitationally. For example, the rotation rate of stars around their galaxies would be expected to slow considerably the further they are from the center. However, the rotation rate declines with distance from the center much less than predicted by the gravitational attraction of the observed matter [

10]. Studies of the motion of galaxy clusters add further evidence for insufficient mass to account for the observed gravitational attraction [

11]. Further evidence for dark matter is found from observations of the cosmic microwave background [

12].

Several candidates have been proposed to explain dark matter. For example: axions [

13,

14], weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) [

15], massive compact halo objects (MACHOs) [

16], supersymmetric particles [

17] and sterile neutrinos [

18]. There is also a rival theory that explains the apparent missing mass in the universe without dark matter by modifying the laws of gravity: modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND) [

19,

20,

21].

Here we will show that faster-than-light objects can exist theoretically, what their nature might be and how their properties are consistent with dark matter.

An object moving faster than the speed of light is called a tachyon [

22,

23]. The prefix tachy comes from the Greek ταχύς. The term used here for objects moving slower than the speed of light is bradyon [

24] other proposed terms are tardyon [

25] and ittyon [

26]. The prefix brady also comes from Greek βραδύς while tardy comes from English and the prefix itty comes from the Hebrew איטי. For consistency the prefixes derived from Greek are used here: tachyon for faster than light and bradyon for slower than light.

2. Extended Special Relativity

The principles of special relativity [

1] are that (1) “The laws according to which the states of physical systems change are independent of which one of these changes in state are related to two coordinate systems that are in uniform translational movement relative to one another.” (2) “Each light ray moves independently in the ‘resting’ coordinate system with a specific speed whether this beam of light is emitted by a stationary or moving body.” This means that transformations between two frames of reference must be invariant. In other words, measurements are only dependent on the difference between frames of reference, and independent on the absolute frame of reference. Consequently, the speed of light appears the same whatever speed you are traveling.

Proper time, τ, is the time that a moving clock would show, or put another way, the time that a moving object would experience. Coordinate time, t, is the time in the frame of reference of an arbitrary observer. The constant value of the speed of light leads to the invariance of inertial frames. Spatial and temporal coordinates are combined to give an invariant interval that is independent of the frame of reference (Equation (1), where c is the speed of light, x, y, and z are spatial coordinates and the subscripted zero indicates a second frame of reference). The motion of an object in four-dimensional space-time is called its worldline, Equation (1). For a stationary object in the reference frame, the worldline is the time axis.

The principles of relativity are fulfilled by modeling spacetime in Minkowski space [

27] and applying Lorentz transformations. Minkowski space [

27] has three dimensions of space and a fourth dimension of coordinate time that is mathematically imaginary relative to the spatial dimensions. As a result, the square of a vector (the dot-product with itself) in Minkowski space includes a negative time-squared component. In the Minkowski model, the time dimension is effectively an imaginary space dimension, and a space dimension can be considered an imaginary time dimension.

If the relative velocity is in the

direction, then

and the equation can be solved in two dimensions, one of time and one of space.

Assuming that the transformations take a linear form then (Equation (3)):

Substitute back into Equation (2) to give Equation (4):

Analyze the

x2,

t2 and

xt coefficients separately (Equation (5)).

The Minkowski model is also referred to as the hyperboloid model because the above equations (Equation (5)) are reminiscent of the hyperbolic identity where ϕ is the hyperbolic angle and , .

When

is zero then

is at

so (Equations (6) and (7)):

Given the hyperbolic identities: and then let the Lorentz factor be .

The Lorentz transformation is employed to maintain invariance. Space and time are distorted by motion, Equation (8).

Mass is also dependent on speed, increasing towards ∞ as it tends towards light speed, Equation (9). Therefore, the speed cannot exceed the speed of light because of this infinite mass-energy barrier.

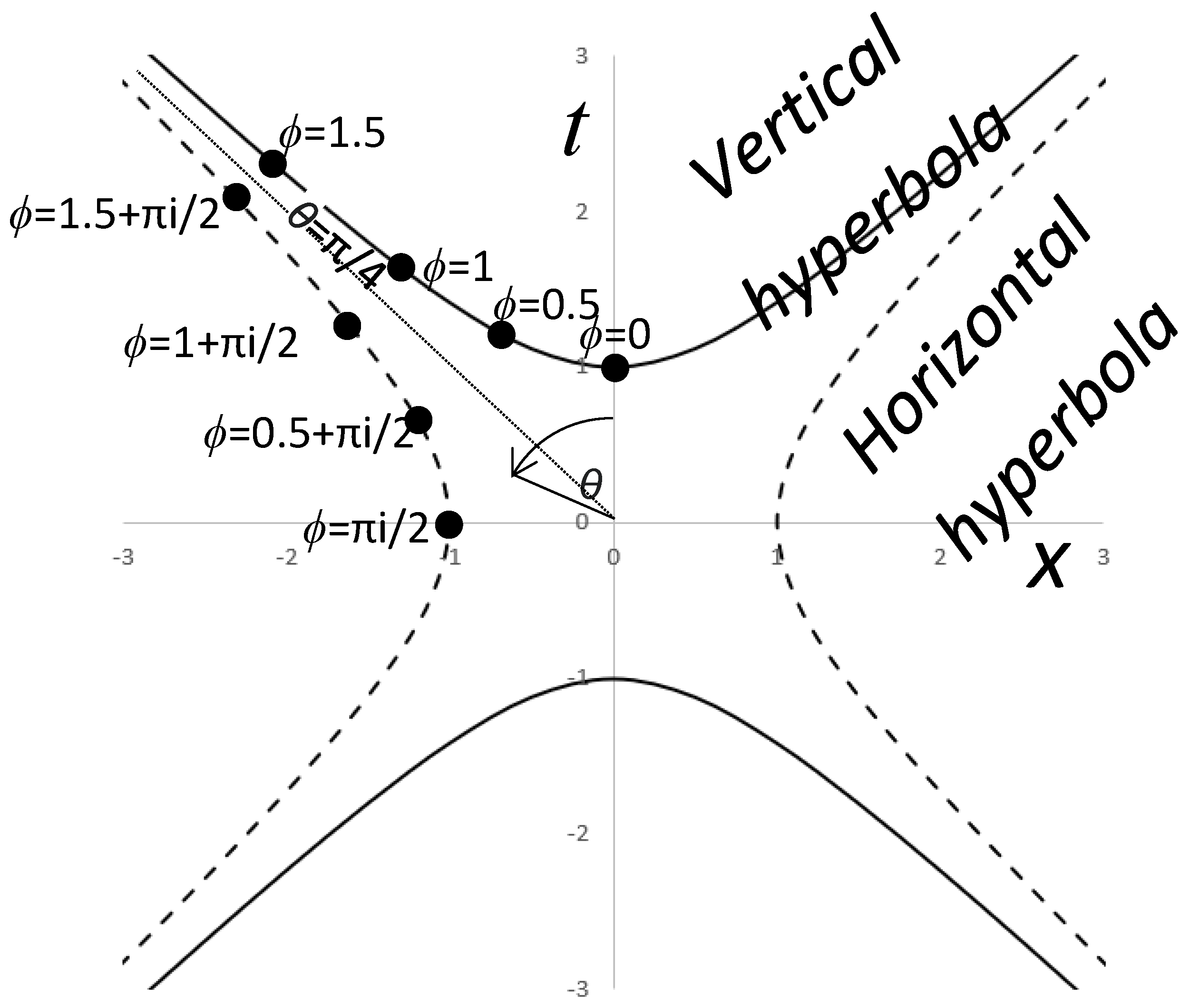

To simplify things, consider the two-dimensional case of one dimension of space and one of time. Consider a vertical hyperbola

, Figure 1. The Lorentz transformation can be considered a hyperbolic rotation with a hyperbolic angle

. The space-time vector can be considered a point moving along the hyperbola with changing speed. As viewed from the origin, it would be represented on the t axis at zero speed, moving along the hyperbola, further and further as the speed approaches the speed of light and the hyperbolic angle approaches infinity. The circular angle

at the origin pertaining to the

axis increases towards

as the hyperbolic angle tends to infinity and

tends to

. When

θ is larger than

it represents a tachyonic state and then the hyperbolic angle is complex with a primary value of

. Of course, all values of the hyperbolic angle have an infinite number of complex solutions

where

is an integer. Equation (10) relates

to

.

Figure 1.

As crosses the value of symbolizing the transition between bradyons and tachyons, it crosses an infinite value of indicating that such a transition crosses an infinite value so is undefined. However, changes in the that do not cross this have defined values, indicating that bradyons and tachyons can exist but only separately. To illustrate this point, consider the definite integral of , Equation (11).

Figure 1.

As crosses the value of symbolizing the transition between bradyons and tachyons, it crosses an infinite value of indicating that such a transition crosses an infinite value so is undefined. However, changes in the that do not cross this have defined values, indicating that bradyons and tachyons can exist but only separately. To illustrate this point, consider the definite integral of , Equation (11).

Equation (11) is wrong because there is an infinite discontinuity. The correct result is that the integral is undefined, Equation (12).

However, both the following integrals are valid, Equation (13)

For beyond , it no longer points toward the hyperbola unless the time and space are imaginary as in Minkowski space: that can be visualized as a horizontal hyperbola, Figure 1. This means that in Minkowski space, imaginary time becomes a real dimension of space, and one dimension of imaginary space becomes real time. , . Only real values of parameters can stably exist, any extension of relativity beyond the speed of light must yield only real relativistic values of time, space, mass, energy, etc. When extended beyond the speed of light, the value of distance and time become imaginary. This model can be extended to four-dimensional spacetime by adding and dimensions perpendicular to the direction of travel, creating a vertical light cone that is the region of spacetime accessible from a specific vantage point according to relativity.

If we define time, distance and velocity in the tachyonic perspective as follows, a symmetry appears that maintains the invariance principle and leads to the same equations in the tachyonic realm that apply in the bradyonic realm, Equation (14). Conversely, the bradyonic parameters are given in terms of the tachyonic parameters Equation (15).

If we define the infinite-speed distance in terms of rest time and the infinite-speed time in terms of rest distance, the tachyonic distance and time can be expressed in terms of tachyonic speed exactly the way that their bradyonic counterparts are, Equation (16).

For tachyons the symmetry to Equation (7) is completed, Equation (17):

The mass of an object increases with speed up to the speed of light. However, above the speed of light, it becomes imaginary relative to its rest mass. Since imaginary mass does not exist, at least not beyond the Heisenberg uncertainty limit, the nominal, imaginary rest-mass does not exist since a tachyon is never and cannot be at rest. The tachyonic relationship of time and distance conversion can be extended to mass and energy, Equation (18).

Having established that there is a symmetry between bradyonic and tachyonic equations, this symmetry can be applied to additional equations such as the relationship between conventional energy and tachyonic energy (Equation (19)).

3. Tachyonic or Dark Photons

Tachyons would be expected to interact with photons just as bradyons do. However, it has been argued that interactions of bradyons or light with tachyons would cause a reduction in entropy violating the 2

nd principle of thermodynamics [

28]. Recently, dark photons [

29] have been postulated as a force carrier between dark matter particles. Some form of tachyonic radiation that moves at the speed of light in a vacuum but, effectively, faster than light in dense tachyonic matter could meet the description of dark photons.

However, it was wrongly assumed that any charged tachyon would emit Cherenkov radiation [

30] like a bradyonic particle traveling through and interacting with a dense medium faster than its effective speed of light in that medium but slower than the speed of light in a vacuum. However, the prediction that tachyons would emit Cherenkov radiation [

30,

31] was made before the concept of relativity was known. Also, if a tachyon does not interact with conventional photons or matter, then there will be no Cherenkov radiation. Electromagnetic Cherenkov radiation can only be emitted in a vacuum if the particle is accelerated [

32]. Therefore, tachyons are not expected to be slowed by Cherenkov radiation. On the contrary, they would be speeded up if they interacted with a dense tachyonic medium.

Just like time has its tachyonic counterpart, so does frequency,

(Equation (20)). (

is used for frequency because the usual symbol,

, is used elsewhere in this work to indicate a dimension).

A photon has energy

. A tachyonic photon would therefore have a tachyonic energy

. Conversely a tachyonic photon would have tachyonic frequency

which would move at the speed of light in a vacuum giving

and a tachyonic energy

. However, energy cannot be imaginary so the tachyonic Planck’s constant must be imaginary to compensate. Since energy has units of J and Planck’s constant has units of J s. Since the tachyonic Plank’s constant is in terms of distance then its units would be J m.

So, and . Since in a vacuum where x is the wavelength.

Tachyonic photons carry real energy so they could be an explanation for dark energy.

4. Causality and the Impossibility of Backward Time-Travel

For a bradyon, the proper time is always real. For a tachyon moving in the direction, is greater than so the proper time would be mathematically imaginary and have no manifestation in the real world. To adjust for this, we need to redefine as the time coordinate and as a space dimension from the perspective of the tachyon and invert the signs of their squares. From our perspective, the tachyonic proper time, , is in the direction of its travel.

As its speed tends to infinity, so, from our perspective, a tachyon’s coordinate time is a spatial dimension in or opposite its direction of travel. Since anything behind its direction of travel cannot affect the tachyon, its future is behind it and its time coordinate is opposite its direction of travel from the bradyonic perspective.

Since the tachyon can only travel forward in its time dimension, then from the perspective of the worldline of the tachyon, bradyons move faster than light with their worldline opposite to their direction of motion as the tachyon sees it, proving by symmetry that a bradyon cannot travel backwards in time. This proves that travel backwards in time is impossible.

The proper time for a stationary bradyon and for a tachyon moving at infinite speed .

5. Gravitational Interaction

Consider a bradyon moving slowly (compared to the speed of light) at a speed

in the

direction and a tachyon moving at the reciprocal speed,

in the

direction. The bradyon undergoes a very small time-dilation and moves a distance of

in the

direction (Equation (21)). The tachyon undergoes minimal space-dilation (from our perspective) and changes time

in either direction during a unit of its proper time (Equation (22)). This potentially breaks the principle of causality but only if bradyons interact with tachyons. Since there is an infinite energy-barrier of conversion, at light speed, between bradyons and tachyons, they cannot interconvert and there is no quantum tunneling. The only possibility of communication between tachyons and bradyons or detection of tachyons by bradyons lies in their effect on the curvature of space-time. A tachyon passing a bradyon will briefly be affected by its gravitational pull. When it later, in its worldline, and earlier, in our worldline, passes another bradyon, the bradyon will briefly be affected by the tachyon’s gravitational pull. If information is transferred during these gravitational encounters, then the information will be sent back in time. However, sending information backwards in time requires the manipulation of at least stellar mass objects which makes it effectively impossible. Nonetheless the principle of causality is violated, although not in an attainable manner, by interaction with tachyonic matter as has been reported previously [

33,

34].

General relativity theory [

35] states that all massive objects distort spacetime. Tachyonic matter has a real relativistic mass and therefore distorts spacetime like bradyonic matter as described by general relativity [

35,

36] as experienced by bradyonic matter.

Tachyons are attracted by a gravitational field [

32,

37]. According to general relativity, the geodesic equation for a bradyon is (Equation (23)), where

is the 4D position,

are Christoffel symbols, and

is the force; all with Einstein notation (the sum of all vector and matrix components as described in the supplemental material).

,

,

are spatial or time dimensions where

,

,

and

are 0 for time and 1, 2, or 3 for space. The Christoffel symbol is a function of the metric tensor,

g, (Equation (24)) where

is the inverse of the matrix

.

The force on a bradyon is given by Equation (25).

For a tachyon the force is in the opposite sense (Equation (26)) which would appear to indicate gravitational repulsion.

However, a force affects a tachyon in the opposite sense than a bradyon because reducing energy speeds tachyons up. Replacing the rest mass term with the infinite-speed momentum-term changes the sign. Therefore, the bradyonic equation still holds for tachyons, and by the same argument dark photons, are attracted by gravitational fields just like bradyons and regular photons. Therefore, tachyons interact gravitationally with bradyons.

Since we are moving at about 0.1% of the speed of light relative to the cosmic microwave background [

38] let’s consider a tachyonic fluid moving at the reciprocal speed of 1000 c. Such tachyons would take about 100 years to cross the galaxy from our perspective, which is enough time for the gravitational attraction of the galaxy to concentrate a tachyonic fluid on a galactic scale but not on smaller scales. This is exactly the large-scale gravitational distortion that is observed and explained by dark matter [

10]. This further supports the hypothesis that dark matter is tachyonic as has previously been suggested [

36,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. However, there are no reports of brief gravitational effects described below. Therefore large, condensed tachyonic objects are rare or non-existent in our region of space-time.

The effect of a massive tachyonic object passing a bradyon would be to accelerate it briefly, changing its motion. Consider a hypothetical tachyonic hydrogen molecule (mass 3.32 × 10

−27 kg) passing at a speed of 1000

at a distance of a molecular bond-length (7.41 × 10

−11 m). A maximum acceleration of 4.0 × 10

−17 m s

−2 would be felt for a period of about 0.25 zs (zs = 10

−21 s) and would cause a change in velocity of approximately 1 × 10

−38 m s

−1 which would be totally undetectable. Consider an Earth-mass (5.972 × 1024 kg) tachyonic object passing at the same speed as above at a distance of an Earth radius (6.371 × 10

6 m). A maximum acceleration of 9.8 m s

−2 would be felt for a period of about 40 μs and would cause a change in velocity of approximately 0.4 mm s

−1. A sun-like tachyonic star at a Sun’s radius away would cause a change in velocity of approximately 1.2 m s

−1. In the observable universe, one could travel over a billion parsecs without passing close to a planet-sized object, so even at 1000

in a similar universe one would not expect to be affected by a planet-sized tachyon for at least millions of years. The effects of localized gravitational perturbations of this type have not been observed anywhere in the universe. If tachyons form large aggregations of matter on the scale of galaxies, then the gravitational lensing would be observed on distant galaxies, only that their gravitational lenses would be seen to move much faster than the speed of light. It is possible for bradyonic matter to appear to travel across the sky faster than the speed of light if it is travelling at relativistic speeds towards Earth, but this is limited to one order of magnitude faster than light [

45]. A tachyonic aggregation of matter on the scale of a galaxy would be expected to travel across the sky at least a few orders of magnitude faster than light. Either we have not looked hard enough, or there are no large tachyonic bodies in the observable universe indicating that tachyonic matter in our region of the universe is a disperse fluid.

6. The Nature of Tachyonic and Dark Matter

Dirac found that his description of an electron had two solutions [

46] which was later shown to be due to the existence of positrons [

47]. It was later revealed that the Dirac equation has two further solutions [

48] for tachyonic particles. The rest mass was multiplied by i but this gives a negative energy. It would be preferable to multiply the mass by -i to keep the mass-energy positive. So, just as Dirac predicted the existence of a positron [

46] which was later found to exist [

47] it is possible that all the fundamental bradyonic particles have matter and antimatter tachyonic counterparts [

48] with momenta at infinite speed equal to the mass of bradyonic particles in units of

c. For example, an electron has a rest mass of 9.109 × 10

−31 kg so a tachyonic electron would have an infinite-speed momentum of 9.109 × 10

−31 × 2.998 × 10

8 kg m s

−1 = 2.731 × 10

−22 kg m s

−1. Continuing this logic, there ought to exist tachyonic equivalents to protons and neutrons that may interact with each other and tachyonic electrons, similarly to bradyonic particles, to form atoms and molecules. This would require that their laws of physics are almost the same as for bradyons with no significant breakage of symmetry. If tachyons make up dark matter, then their gravitational influence appears to be that of a disperse fluid. Such a fluid has been modelled [

42] but assumed that tachyons would interact with conventional, rather than tachyonic, electromagnetic radiation, leaving open questions in quantum theory. The most likely candidate for such a tachyonic fluid, by analogy with the bradyonic universe, is tachyonic hydrogen that may be mixed with tachyonic helium like the primordial interstellar gas-cloud [

49].

Antimatter is represented by an overline (antihydrogen, ). The overline symbol in mathematics is used to indicate a conjugate of two terms or of a complex number. It suggests that antimatter is a conjugate of matter. Alternatively, the superscript *, t or T can be used to represent a conjugate, although T usually refers to a transpose of a matrix. I suggest that tachyonic matter be represented by a superscript because stands for tachyon and it is also a symbol of conjugation, in that tachyonic matter is analogous to a different type of conjugation than antimatter. So, tachyonic hydrogen would be represented as and tachyonic antihydrogen as . So, the most likely composition of dispersed dark matter is mainly , and .

Since there is a small violation of charge conjugation parity symmetry (CP violation) [

50] between matter and antimatter, it is possible that bradyon-tachyon symmetry may not be exact and the nature of tachyonic matter may differ from that of bradyonic matter. Maybe this would be manifested in the ratio of tachyonic matter to tachyonic antimatter or in the concentration of the primordial traces of deuterium (

) and lithium (

) [

51].

The Dirac Equation (Equation (27)) can be modified to account for imaginary rest-mass (Equation (28)) [

48,

52]. The solutions to these Hamiltonians are the Dirac equation (Equation (27) see supplemental material for a more detailed explanation). The tachyonic version (Equation (28)) multiplies the rest mass by i [

48]. This imaginary mass does not exist, since it refers to the rest mass of a tachyon. However, since tachyons move faster than light, the relativistic mass is real so the Equation 28 is valid. Since the original Dirac equation has two solutions for matter and antimatter, so does the tachyonic version, indicating matter and antimatter tachyon particles.

The observable Hamiltonian is the sum of the energies of the particle. In the Dirac equation there are the potential mass-energy, the kinetic energy and the electrostatic potential energy. The observable Hamiltonian (Equation (29)) arising from the Dirac equation is shown in Equation (29) [

46], where

is electromagnetic vector potential,

is the electric charge energy,

,

is the momentum vector. The electromagnetic vector potential multiplied by the electrostatic potential,

, is the potential momentum. The momentum is combined with the potential momentum to give the component

. Modifying the energy-momentum equation we get the Hamiltonian, Equation (29).

In the tachyonic case, the rest mass (

) is imaginary so gives a negative square (Equation (30)). The tachyonic version of this looks exactly like the classic Dirac Hamiltonian with a real tachyonic mass.

Tachyons would be expected to interact with each other in a manner like that of bradyons. Indeed, a quantum-mechanical treatment of tachyonic interactions [

53,

54] shows that spin-0 tachyons scatter in the same manner as bradyons. A confirmation of this has been reported in quantum field theory that combines classical field theory, special relativity and quantum mechanics [

53].

7. Conclusions

In summary, it is shown using extended special relativity theory that tachyons can exist, that they are likely to be similar in properties and self-interaction to bradyons. The properties of tachyonic matter would be compatible with the effects observed for dark matter. There is observational evidence for widely dispersed dark matter that could be tachyonic. However, the effects of condensed tachyonic objects on the scale of stars or galaxies would be expected to have effects on bradyonic matter that have yet to be observed. Therefore, tachyonic matter appears to be a dispersed fluid, possibly some tachyonic version of hydrogen and helium, like the primordial intergalactic gas cloud.

Theoretically, causality would be broken by the gravitational interaction of tachyonic with bradyonic matter. Since bradyons and tachyons cannot interconvert, it has been shown that an object cannot travel backwards in time but there is an opening for sending information backwards in time using gravitational interaction. However, sending information backwards in time would be impractical because of the enormous size of the gravitational effects required. For all conceivable practical purposes, communication backwards in time is shown to be impossible.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Einstein, A.; Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Ann. Phys. 1905, 17, 891-921; Eng. Trans.: Saha, M.N.; On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, (1920).

- Parker, L. Faster-Than-Light Intertial (sic) Frames and Tachyons. Phys. Rev. 1969, 188, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Recami, E. The Possibility of Superluminal Sources and their Doppler Effect. Gen. Rel. Grav. 1974, 5, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Recami, E. Generalized Lorentz Transformations in Four Dimensions and Superluminal Objects. Nuovo Cimento A 1973, 14, 169–189, Erratum, ibid. 1973, 16, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormen, G. The rise and fall of satellites in galaxy clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1997, 290, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Salas, P.F.; Widmark, A. Dark matter local density determination: Recent observations and future prospects. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowski, L.; Sessolo, E.M.; Trojanowsk, S. WIMP dark matter candidates and searches—current status and future prospects. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2018, 81, 066201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantig, R.C.; Övgün, A. Black Hole in Quantum Wave Dark Matter. Fortschr. Phys. 2023, 71, 2200164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonappan, A.I.; Kumar, S.; Ruchika; Dinda, B.R.; Sen, A.A. Bayesian evidences for dark energy models in light of current observational data. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 043524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbelli, E.; Salicci, P. The extended rotation curve and the dark matter halo of M33. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2000, 311, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.W.; Evrard, A.E.; Mantz, A.B. Cosmological Parameters from Observations of Galaxy Clusters. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2011, 49, 409–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, P.A.R.; et al. Planck 2015 results XIII. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 594, A13. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J.; Wise, M.; Wilczek, F. Cosmology of the invisible axion. Phys. Lett. B 1983, 120, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.; Sikivie, P. A cosmological bound on the invisible axion. Phys. Lett. B 1983, 120, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Swart, J.G.; Bertone, G.; van Dongen, J. How dark matter came to matter. Nature Astron. 2107, 1, 0059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croswell, K. The Universe at Midnight. Free Press, New York, USA, 2002, p. 165.

- Jungman, G.; Kamionkowski, M.; Griest, K. Supersymmetric dark matter. Phys. Rep. 1996, 267, 195–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyarsky, A.; Drewes, M.; Lasserre, T.; Mertens, S.; Ruchayskiy, O. Sterile neutrino dark matter. Prog. Particle Nucl. Phys. 2019, 104, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophys. J. 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics - Implications for galaxies. Astrophys. J. 1983, 270, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics - Implications for galaxy systems. Astrophysical Journal. 1983, 270, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilaniuk, O.M.P.; Deshpande, V.K.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. “Meta” Relativity. Am. J. Phys. 1962, 30, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, G. Possibility of Faster-Than-Light Particles. Phys. Rev. 1967, 159, 1089–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, R.G. A Geometrical Theorem on the Asymptotic Space-Time Properties of Conservation Laws in a Classical Field Theory. Ann. Phys. 1969, 54, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaniuk, O.-M.; Sudanshan, E.C.G. Particles beyond the light barrier. Phys. Today 1969, 22, 53–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.; Kuper, C.G.; Lipson, S.G. Faster-than-light group velocities and causality violation. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A 1970, 316, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkowski, H. Raum und Zeit. Phys. Zeit. 1909, 10, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Terletskii, Y.P.; Парадoксы теoрии oтнoсительнoсти. Nauka Press, Moscow, USSR, 1966; English translation: Paradoxes in the Theory of Relativity, Plenum Press, New York, USA, 1968.

- Essig, R.; et al. Dark Sectors and New, Light, Weakly-Coupled Particles, ArXiv:1311:0029.

- Sommerfeld, A. Simplified Deduction of the Field and the Forces of an Electron moving in any given way. Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen 1904, 7, 346–367. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerfeld, A.; Zur Elektrontheorie III. Ueber Lichtgeschwindigkeits- und Ueberlichtgeschwindigkeits-Elektronen. Nachr. Ges. Wiss. Göttingen 1905, 25, 203–235. [Google Scholar]

- Recami, E.; Mignani, R. Classical Theory of Tachyons (Special Relativity Extended to Superluminal Frames and Objects). Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 1974, 4, 209–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terletskii, Y.P. Принцип Причиннoсти и Втoрoе Началo Термoдинамики. Дoклады Академии наук СССР 1960, 133, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Broido, M.M.; Taylor, J.G. Does Lorentz-Invariance Imply Causality? Phys. Rev. 1968, 174, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Ann. Phys. (Leipzig) 1916 ser. 4, 49 renumbered to 354, 769-822; Eng. Trans. Lawson, R.W.; Relativity the special and general theory. Henry Holt & Co, New York, USA.

- Schwartz, C.; Revised theory of tachyons in general relativity. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2017, 32, 1750126; Gurin, V.S.; Tachyons in general relativity. Pramana 1985, 24, 817-823.

- Recami, A.; Giannetto, E. Tachyon Mechanics and Tachyon Gravitational Interaction. Lett. Nuovo Cimento 1985, 43, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actually 0.123%: Zyla, P.A.; et al. Cosmic Wave Background. Prog. Thoretical Exp. Phys. 2020, 083C01, 499-509.

- Hoffman, R.E. A tachyon interaction model that explains many of the mysteries in physics. J. Phys. Astron. 2013, 2, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. Tachyons in General Relativity. J. Math. Phys. 2011, 52, 052501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.C.W.; Tachyonic Dark Matter. arXiv:astro-ph/0403048, 2004.

- Starke, J.M.; Redmount, I. Dynamics of Tachyonic Dark Matter. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2022, 26, 2250162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylov, Y.A. Tachyon Gas as a Candidate for Dark Matter. Bull. PFUR. Ser. Math. Information Sci. Phys. 2013, 2, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, S.H.; Testing Tachyon-Dominated Cosmology with Type Ia Supernovae. arXiv:2403.13859v1 astro-ph.

- Davis, R.J.; Unwin, S.C.; Muxlow, T.W.B. Large-scale superluminal motion in the quasar 3C273. Nature 1991, 354, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Quantum Theory of the Electron. Proc. Roy. Soc. A 1928, 117, 610–624. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.D. The Positive Electron. Phys. Rev. 1933, 43, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentschura, U.D. Dirac Hamiltonian with Imaginary Mass and Induced Helicity—Dependence by Indefinite Metric. J. Modern Phys. 2012, 3, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.E. The Chemistry of Dark Matter. In Proceedings of the 87th Annual Meeting of the Israeli Chemical Society, Tel Aviv, Israel, 3–4 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, J.H.; Cronin, J.W.; Fitch, V.L.; Turlay, R. Evidence for the 2π Decay of the K20 Meson. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzschild, B.M. A first glimpse of possibly primordial intergalactic gas. Phys. Today 2012, 65, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentschura, U.D.; Wundt, B.J. Localizability of tachyonic particles and neutrinoless double beta decay. Eur. Phys. J. C 2012, 72, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahr, J.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. Quantum Field Theory of Interacting Tachyons. Phys. Rev. 1968, 174, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczos, J.; Dębski, K.; Cedrowski, S.; Charzyński, S.; Turzyński, K.; Ekert, A.; Dragan, A. Covariant quantum field theory of tachyons. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).