1.0. Introduction

Recent results have highlighted how ongoing cosmological observations increasingly show that the standard cosmological model, ΛCDM, is missing some of the physics of the universe [

1,

2,

3]. Recent observations from the DESI Collaboration [

4], the JWST [

5], and others with increasingly precise measurements have shown predictions from ΛCDM to be slightly different than observation. This highlights the challenge of modifying or replacing ΛCDM – it must maintain the primary features of ΛCDM while simultaneously resulting in small changes in its predictions that eliminate the multiple discrepancies that have been observed. A model [

6] based on the concept of spacetime duality [

7], has shown promise in resolving the Hubble Tension, the

S8 tension, and predicts a time-dependent dark energy density that matches that of the DESI observations [

4]. It also resolves some basic physics concerns with the predictions of ΛCDM, predicting the total energy of the universe resolving back to its pre-Big Bang value rather than increasing without limit, and showing how one can have a cosmological horizon without having galaxies moving apart at superluminal velocities.

There is currently no widely accepted theory for the nature of dark matter and the theories being proposed are increasingly constrained by measurements [

8,

9,

10,

11] or invoke highly specialized conditions [

12]. The first 41 references of a recent paper [

13] summarize the shortcomings of the standard model in general and with respect to dark matter and cosmological anisotropies and asymmetries in particular.

We show how the concepts of spacetime duality and generalized time, along with a model of the Big Bang based on CPT symmetry and symmetry between time and space, result in a cosmological model that shows why there is more matter than antimatter in our universe, predicts most of the observed properties of dark matter, makes new predictions about dark matter, and explains some anisotropies in the universe that are otherwise puzzling.

Spacetime duality [

7] is the idea that the fabric of spacetime is a separate entity from the material world (normal matter and energy) and the coordinate system of the material world. The most common illustration of this is the example from general relativity where a rubber sheet represents spacetime and a heavy ball represents a material object. The mass of the ball distorts the rubber sheet, which in turn determines how the ball moves across the rubber sheet. Noted physicist John Wheeler summarized this as: “Matter tells spacetime how to curve, and curved spacetime tells matter how to move” [

14]. The material world is subject to quantum mechanics, whereas the fabric of spacetime is not. Spacetime duality was shown to explain compactification in string theory; provide a framework for coupling gravity with quantum field theory with a simple physical explanation for why gravity is weak relative to the other three forces; resolve the black hole information paradox; and avoid singularities in black holes [

7]. Application of the concept to the LCDM model resolves the Hubble tension and the

S8 tension, and predicts a time-varying dark energy density in accord with DESI measurements [

4].

Generalized time (g-time or

tG) [

15] is the concept that the flow of time is more complicated than normally assumed. In particular, time flows in one direction (the normal direction,

tN) for events described by classical (Newtonian) physics and an orthogonal direction (the QR direction,

tQR) for events described by quantum mechanics or relativity. That work showed the concept of generalized time provides an explanation for quantum entanglement that is causal without violating the speed of light, provides insight regarding collapse of the wave function in a quantum system, explains why time goes backwards for antiparticles in Feynman diagrams, provides a simple intuitive perspective to understand time dilation and length contraction in special relativity, provides physical insight for the use of “imaginary time” in a variety of fields, and explains cosmic inflation without superluminal expansion of the universe. Generalized time replaces the notion of time flowing in a particular direction with time as a geodesic, traveling a single path through a temporal space that is described by the physical nature of the interactions occurring within that time flow. For reasons of causality (see [

15]) and consistency with the 3 dimensions of space (see

Section 2), the directions time can flow are distinct directions rather than separate dimensions. Mathematically, the rate of flow of generalized time is constant. As a system transitions from being in a quantum/relativistic state to a classical state, the respective flow rates of time are given by:

Section 2 develops a model of the Big Bang based on g-time and spacetime duality. That model has a natural separation of matter and antimatter.

Section 3 reviews the historical work on the preponderance of matter in our universe and how the Big Bang model in

Section 2 is consistent with theoretical constraints and observation.

Section 4 shows how g-time provides a physical model for cosmic inflation, resolving current theoretical concerns about that model.

Section 5 investigates the implications of the g-time model of the Big Bang, and shows that the predictions from that model describe the major properties of dark matter.

Section 6 investigates the implications of that model for some otherwise puzzling anisotropies observed in galaxy rotation.

Section 7 summarizes the results and provides comments on the potential impacts of spacetime duality and generalized time to cosmological models.

2.0. A Generalized-Time Model of the Big Bang

There are currently no widely accepted theories that explain why there is more matter than antimatter, why cosmic inflation was so rapid shortly after the Big Bang, the nature of dark matter, or why there is about 5 times as much dark matter as observable matter. The assumptions of g-time and spacetime duality, along with application of some basic symmetries, lead to a simple physical model of the Big Bang and the early universe that explains all of these.

There are many features of the known universe that can be explained, at least qualitatively, by combining g-time with a simple model of the Big Bang as a fluctuation analogous to vacuum pair production. We make the standard assumption that antimatter obeys CPT symmetry, and make the additional assumptions that time has three dimensions in addition to the two directions of g-time (with our universe only having one of those three temporal dimensions) and that the fabric of spacetime has a higher dimensionality than typically assumed. These assumptions provide a model that is consistent with ΛCDM, and with greater explanatory power.

The creation of the universe via a quantum fluctuation, with subsequent Big Bang expansion per Guth’s inflationary universe, was first described by Tryon [

16], but with equal amounts of matter and antimatter. Later quantum fluctuation models did not require a Big Bang singularity or equal amounts of matter and antimatter [

17]. A key point here is that it is possible to create a universe with no preceding extent of space and/or time. With ST duality, it is interesting to note that the universe will revert to a state of no space or time as the scale factor of the universe goes to zero.

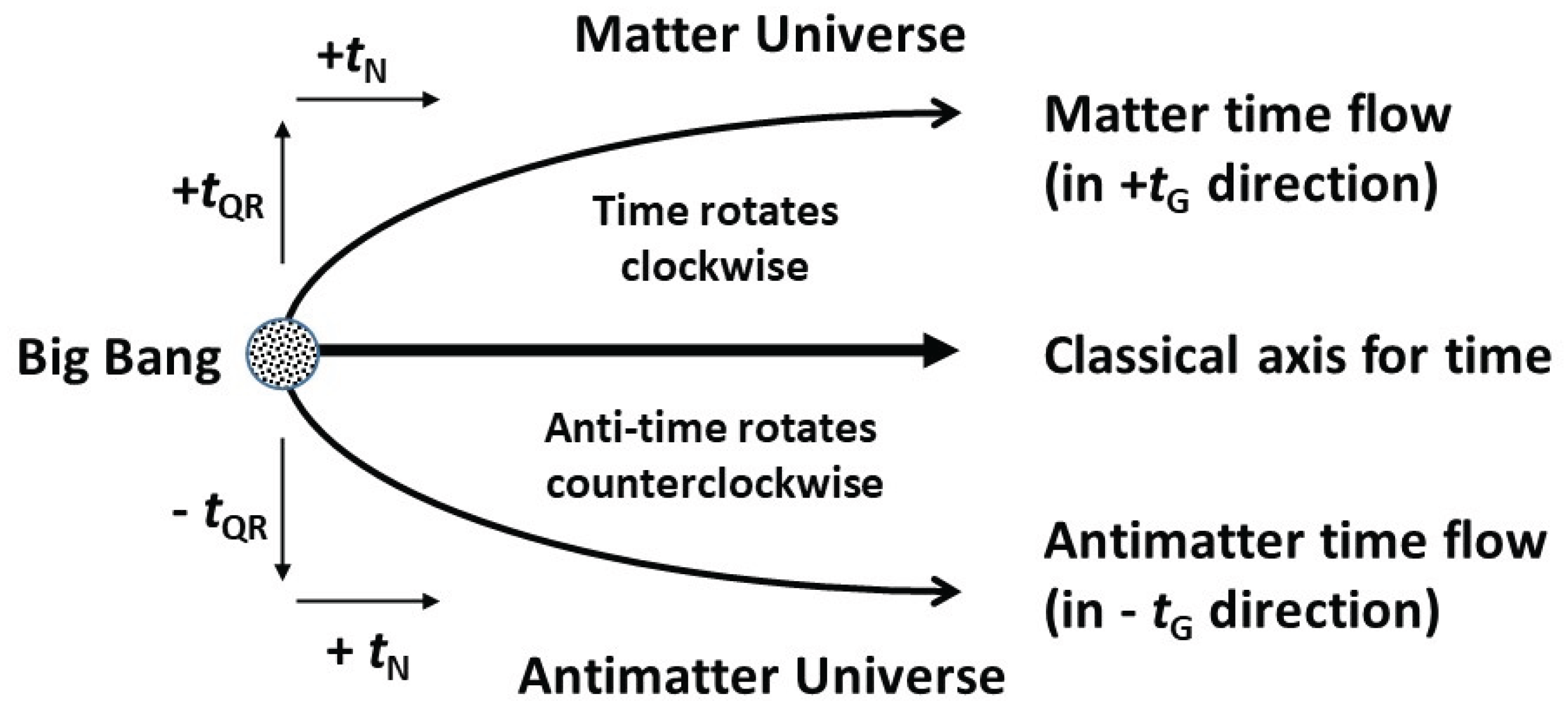

In the initial moments of the Big Bang, the standard model of particle physics has strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces being indistinguishable from each other, as were electrons, quarks, and neutrinos and their antimatter counterparts. The flow of time in this state did not necessarily correspond to either of the two directions of g-time. As the universe cools, those fundamental particles became distinguishable and matter and antimatter became distinguishable. The matter particles (quarks and electrons and their force carrying particles, photons and gluons) now have time flowing in the positive g-time direction, and the antimatter particles (antiquarks and positrons and their force carrying particles) have time flowing in the negative g-time direction, as shown in

Figure 1. With further cooling, the quarks combine to make protons (two up quarks and a down quark) and neutrons (two down quarks and an up quark). Eventually the universe cools enough that atomic hydrogen forms from protons and electrons (see

Section 4), and physical interactions describable by classical physics can occur, with time flowing in the normal direction. The same is true for antimatter – the antiquarks form antineutrons and antiprotons, and the antiprotons combine with positrons to form antihydrogen. This description neglects the other particles present, but is a good approximation as the other particles have much shorter lifetimes and will therefore have their abundances driven by the energetics of the longer-lived particles discussed here.

In the g-time model, time is always flowing forward, meaning in the positive

tG direction, for matter and by CPT invariance time is flowing in the negative

tG direction for antimatter. In the highly quantum and relativistic environment of the very early universe, time was initially flowing exclusively in the QR direction. As the universe cools, atomic hydrogen forms (and antihydrogen in the antimatter universe), quantum and relativistic interactions became less important, and time begins to flow in the real direction. Applying CPT invariance to the time flow of antimatter, the rotation from QR time,

tQR, to normal time,

tN, would have the opposite parity as that for matter.

Figure 1 illustrates this. Because time is flowing in opposite directions for matter and antimatter, there is a natural separation of the two into separate universes. In this model, those two universes are on different sides of the same fabric of spacetime. We also see from

Figure 1 that the rotation into normal time means that even though time is initially flowing in the negative QR direction for antimatter, it becomes synchronized with the flow of time in the positive direction in the matter universe. We thus have a very simple model that explains why there is almost no antimatter in our universe.

Figure 1 is analogous to

Figure 2 in [

15] explaining why time goes backwards for antimatter in Feynman diagrams. That raises the question of why antimatter separates into its own universe in the Big Bang, but not during pair production. The answer is that the entirety of the Big Bang had time flowing in the QR direction since all interactions were quantum and relativistic, whereas pair production in our universe occurs as an event embedded in a classical system, where time primarily runs in the normal direction.

This explains why the flow of time has a definite direction. In quantum mechanics, there is no preferred direction to the flow of time. In pair production for particles with spin, one particle is spin up and one is spin down. Those spin properties are integral to the particle. Here, by analogy, when the matter and antimatter universes separate, there are equal and opposite flows of time for matter and antimatter. Those time flows are integral to the nature of those universes and cannot be reversed. The direction of the flow of time is an integral part of the quantum mechanical description of our universe. With the flow of time as a quantum variable, this explains why the magnitude of the flow of g-time is a vector of constant length as noted in

Section 1.

There are other models that invoke CPT invariance to posit an antimatter universe that exists

before the Big Bang (e.g., [

18,

19,

20]). From these other models, we see there are two possible meanings of “before.” The first describes events that happened for negative values of normal time, which actually starts at the Big Bang.

Figure 1 shows this is not physically possible in the model here. In some sense, time itself began at the Big Bang, which is widely but not universally assumed to be the case in cosmology. The second meaning of “before” is for events with a smaller value of real time, but still after the Big Bang. We see from

Figure 1 that this is true for both the matter and antimatter universes, however in the antimatter universe, one would say that the numerical value of time is less negative when measured in the flow of anti-time (which flows in the opposite direction of time for matter), but less positive when measured in real time.

Section 2.1 continues this discussion with a broader perspective on time flow before the Big Bang.

Considering

Figure 1, with the matter and antimatter universes synchronized in their time evolution once time has rotated to the normal direction, it is a small step to see that they can interact with each other gravitationally if they share the fabric of spacetime. That would be the case if the fluctuation that resulted in the Big Bang occurred in a realm that contains our universe, its antimatter partner, and the shared fabric of spacetime. (The realm in which the Big Bang occurred is analogous to the bulk in brane cosmology, being a higher dimensional realm in which our 3+1 universe is embedded.) By general relativity, matter in either universe would warp the shared fabric of spacetime, so the two universes could interact gravitationally through the fabric of spacetime, but would not be able to interact in any other way. This provides the starting point for a physical model for dark matter.

The assumption of the fabric of spacetime as a distinct entity has a deep basis in quantum mechanics [

7], and is implicit in the dark energy model for the expansion of the universe where the void of space between gravitationally bound galactic clusters is expanding, but the space within a galactic cluster is not. This is because Einstein’s cosmological constant (the Λ in ΛCDM) causes the space between gravitationally bound groupings to expand, but not the gravitationally bound grouping itself [

21,

22]. A companion paper on dark energy [

6] shows that this assumption leads to a model for dark energy that fits recent measurements [

4] from the Dark Energy Survey Instrument (DESI) better than the ΛCDM model. Here we assume that the Big Bang occurred either within the fabric of spacetime as something analogous to a quantum fluctuation, or that the fluctuation occurred within some other realm, generating the fabric of spacetime and our universe as existing on the “surface” of that fabric. The geometry of this fabric of spacetime is described by analogy in the next paragraph.

To complete the model, we make the assumption that time is symmetric with space and has three dimensions, each of which has generalized time. Matter and antimatter condensing out of the Big Bang results in the creation of six universes: 3 matter universes, one from each dimension of time, and 3 corresponding antimatter universes where time initially flows in the opposite direction to that of its partner matter universe. Eventually the flow of time for all six universes synchronizes in the positive normal direction. A two-dimensional analogy would be 4 people at the North Pole, initially walking away from the Pole in four orthogonal directions, but eventually all moving in the same direction when they reach the equator. These six universes would exist on the “surface” of the fabric of spacetime and be able to interact with each other gravitationally through the fabric of spacetime, just as described in general relativity. The five universes other than our own are referred to here as the “dark universes.” Note that three of them are made from antimatter and two from matter, so there is the possibility of two kinds of dark matter, with one kind more prevalent than the other. The observed properties of dark matter are sufficiently varied that it has been proposed that there may be more than one kind of dark matter [

23].

The possibility of time having three dimensions has been considered in prior work. Kletetschka summarizes that work and notes that those theories often had causality and stability challenges [

24]. While Kletetschka references Tegmark’s paper constraining time to only one dimension [

25], he does not address how to resolve the underlying causality concern. Kletetschka’s three time dimensions are:

t1 for quantum phenomena,

t2 for interactions including the quantum and classical phenomena, and

t3 for cosmological time scales. While there are differences in the details, those times approximately correspond to

tQR and

tN in g-time, and the contracting time scale of scale-invariant cosmological evolution described in Henderson [

6]. Kletetschka states that the formula for the dark energy dependence on scale factor

(

can be used as a test of whether his model of time having three dimensions is valid. That formula decreases with increasing scale factor

a, near

a=1, whereas the DESI Collaboration found a dark energy dependence

[

4], which increases with increasing

a near

a=1, indicating the formalism of Kletetschka does not match the observed universe. (The spacetime duality formalism here matches the DESI findings [

4].) We conclude that the distinction between dimensions and directions for time is critical in developing a physical model for the universe. Here time is a quantum variable in each of the three dimensions and flows as a geodesic in a temporal space having at least the

tQR and

tN directions, so it is not possible for there to be more than one path through time between two events and therefore no causality concerns.

Finally, we note one feature expected if the Big Bang was analogous to a quantum fluctuation resulting in pair production. (The Big Bang as a quantum fluctuation is not a novel idea. See [

16].) The Heisenberg uncertainty principle allows energy to appear as long as it does so for a sufficiently short period of time. In pair production from a quantum fluctuation, that energy goes into making a particle and its antiparticle, plus some energy which initially propels them away from each other. However, electrostatic attraction from the oppositely charged pair members pulls them back together, where they annihilate and restore the system to its initial energy state. (A companion paper on dark energy and the future of the universe [

6] addresses the question of how that energy resolves back to its initial state.) The line between the particles defines an axis for the system, which breaks the isotropy of what one might otherwise expect from a random fluctuation.

Figure 1 shows how the matter and antimatter created in the Big Bang naturally separate into separate universes without having to invoke any symmetry breaking. The nature of g-time and CPT invariance are sufficient to cause that separation.

The extension of that model of the Big Bang makes clear there are 5 dark universes, which will be shown in

Section 4 to have the same properties as dark matter, and the differing rotation directions for the flow of time in the matter and antimatter universes will be seen as a possible explanation for time-dependent rotational asymmetry in our universe in

Section 5.

2.1. Four Directions for Time Flow

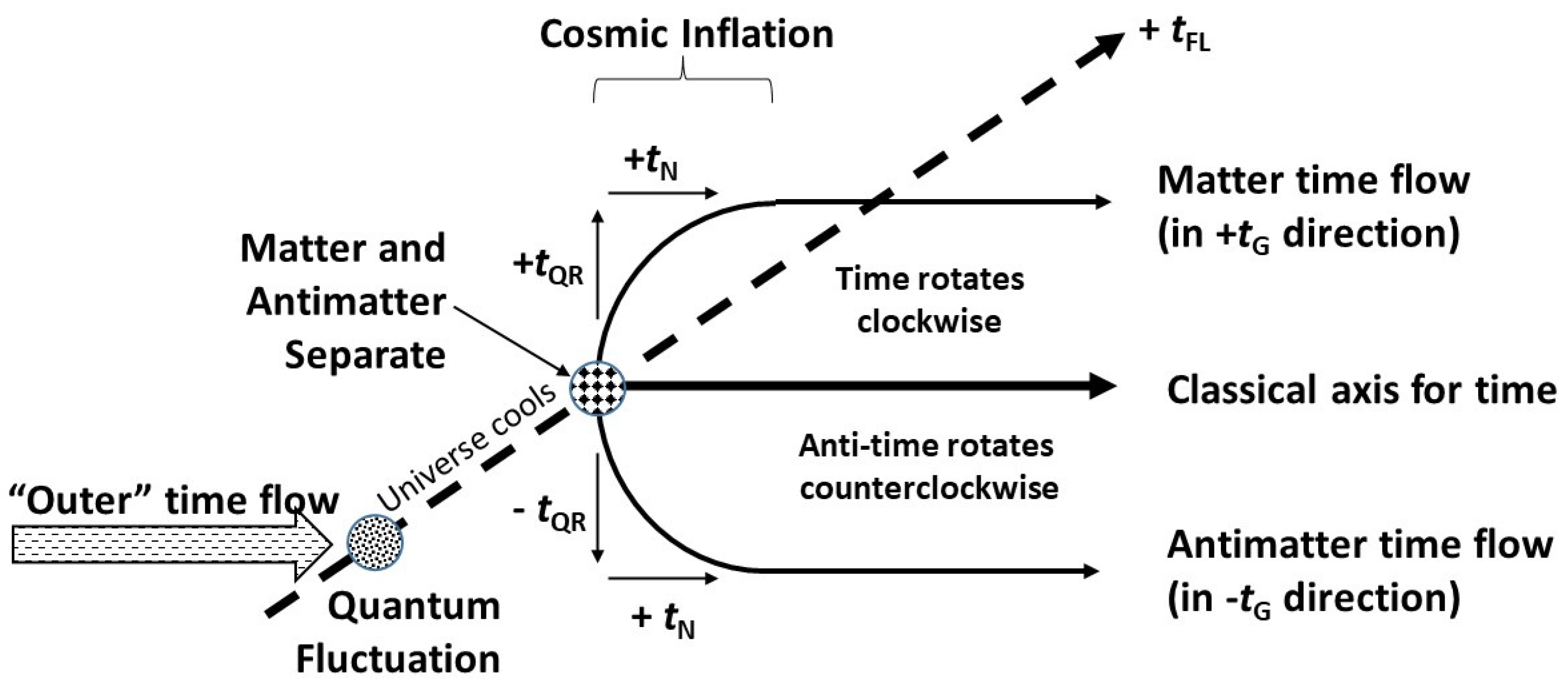

For completeness, we now address that this model actually involves four different time flows: the time flow in the realm in which the quantum fluctuation occurred, the initial time flow before matter and antimatter separated, and the normal and QR time flows that are the crux of the separation of matter and antimatter and other CP violations.

The theoretical basis for g-time is grounded in a paper by Page and Wootters [

26] where the flow of time arises as an internal variable to a larger quantum system, much as a spin-0 system can have spin up and spin down particles within it. Experiment has shown there is a time flow in a quantum system in addition to the classical/normal flow of time [

27,

28], validating the g-time model here. The Page and Wootters formalism allows for a separate time flow each time one considers a higher-level of quantum system, which we have used here to describer the time flow in the realm in which the quantum fluctuation occurred. In the derivation of g-time, we allowed for additional directions for the flow of time under other physical conditions [

15], which is used here to describe the time flow between the fluctuation which began our universe and the separation of matter and antimatter. The resulting time flows are then for the “outer” realm in which the fluctuation occurred,

tOUT, the time flow between the fluctuation and matter/antimatter separation,

tFL, the QR time flow,

tQR, and then the flow in normal/classical time as the universe further cools,

tN.

Figure 2 Shows this graphically. Mathematically, this would be written as the quaternion

Where

T represents the most generalized view of the flow of time and the

i,

j, and

k symbols make explicit that the four time flows are in orthogonal directions.

We are now in a better position to answer the question of “what happened before the Big Bang?” From the larger perspective of the realm that hosted the quantum fluctuation that resulted in our universe, there was the initial flow of time there, then there was the flow of time until the forces separated, then there was the flow of time in the QR direction, and finally there was the flow of time in the normal direction. This provides a continuous perspective on the flow of time, with the caveat that each of those time flows is in a direction orthogonal to the others. The theoretical work of Page and Wootters and the experimental work of Ekaterina et al provide the basic concept for time being able to flow in multiple, orthogonal directions.

4.0. Cosmic Inflation

Inflation theory was developed to explain three observations about the cosmos: that spacetime is flat, the uniformity of the CMB, and the failure to detect magnetic monopoles [

37,

38]. Cosmic inflation achieves those and has been very successful in explaining the large-scale features of the universe. Current theoretical work is ongoing to address shortcomings of the theory. Five major concerns are: (1) there is no accepted mechanism for inflation itself (nor has the underlying inflaton been detected), (2) inflation involves expansion velocities many times the speed of light, (3) it is not clear why inflation would turn on when it did, (4) there is no accepted mechanism for why inflate on should turn off, much less turn off when it did, and (5) experiments have failed to detect the primordial gravity waves or polarized CMB predicted by inflation. Spacetime duality and generalized time provide a model of events immediately after the Big Bang that resolves the three problems inflation was developed to solve, and avoids those concerns.

Spacetime duality predicts that the lowest energy state for the fabric of spacetime is for spacetime to have a flat geometry [

7], resolving the first problem inflation solves. Interaction with the material world causes spacetime to warp, increasing its energy. The vast majority of space has negligible gravitational potential energy, due the low density of particles and the relative weakness of gravity. Warping the fabric of spacetime takes energy, and with essentially no energy available to warp it, the fabric of spacetime is flat.

The uniformity of the CMB is explained by realizing that the universe was in a quantum state prior to the events that allowed the photons of the CMB to escape. It is not until the universe had expanded and cooled sufficiently for atomic hydrogen to form that time could start to flow in the normal direction. Prior to that, interactions were relativistic and quantum, and time flowed in the QR direction. After that, time started to flow in the normal direction, the coherent quantum state collapsed, and the quantum fluctuations of that quantum state were “frozen in,” resulting in the small inhomogeneities seen in the CMB today.

With the universe having a size of about 1 m [

39] at the end of inflation and time flowing in the QR direction prior to that, the entire universe would have been described by a single quantum state. Superconducting wires have a quantum state many times this distance, and superfluids in the laboratory can have comparable scale size, validating this assumption. With time flowing in the QR direction, the universe had sufficient time to expand at sub-luminal velocities. From an initial size of 4x10

-29 to a final size of 0.9 m ~10

-35 s later [

39], inflation requires an average expansion velocity of ~10

35 m/s or ~3x10

26 c. Assuming an average relativistic expansion velocity of 0.1

c, expansion would have taken ~3x10

-8 s of time in the QR flow direction, finishing well before protons formed at ~10

-6 s in the normal time flow direction. When classical interactions start (e.g., interactions between atomic hydrogen), the flow of time begins in the normal direction. This means there is no longer a single quantum state for the universe, and that the superluminal expansion (as measured when only considering

tN) stops. This provides a simple mechanism for inflation, and a simple physical model for when inflation starts and stops.

The flow of time in the QR direction means that there are no magnetic monopoles for the same reason as why there is so little antimatter in our universe – the monopoles do not get entrained in the time flow of our universe. With the early universe is in a superconducting state (time flow in the QR direction), magnetic monopoles will not be able to transition to the normal flow of time as matter and antimatter separate, as this would take infinite energy. The magnetic field inside a superconductor is inherently zero. By symmetry, the high energy density conditions in the primordial soup of the universe generates both magnetic monopoles and antimonopoles. There are two possibilities for how one of each would interact. First is that they are pulled in the +

tQR and -

tQR time directions, respectively. There will be magnetic field lines between the monopole and the antimonopole. In a superconductor, the only way for the bulk magnetic field to be zero is for a flux tube to form between the monopole/antimonopole pair. As the two are pulled apart, the length of that flux tube increases, and the potential energy of the flux tube increases linearly with its length, as the amount of magnetic flux in the tube is constant at any cross section of the tube. For the pair to follow the +

tQR and –

tQR temporal directions respectively, they will end up on different sides of the fabric of spacetime; will only be able to interact gravitationally; and are therefore effectively infinitely distant from each other with regard to the flux tube since electromagnetic force does not cross the fabric of spacetime. This requires infinite energy, and so will not happen. The second possible explanation for the absence of monopoles is that the energy to create a magnetic monopole is above that for which the forces separate and matter and antimatter become distinguishable, so that by the time the universe has cooled sufficiently for matter and antimatter to become distinguishable, the energy available is too low to create magnetic monopoles. GUT models predict a monopole mass of around 10

16 GeV, in the same region where forces separate. Rajantie has recently reviewed theories of magnetic monopole formation [

40]. Experiments have not detected magnetic monopoles and have put a lower limit on their mass of ~4x10

3 GeV [

41].

Within the context of the current model of inflation, the flow of time in the QR direction explains why there are no magnetic monopoles. Alan Guth makes the argument [

38] that inflation provides a mechanism to delay the phase transition in which the universe has cooled sufficiently for magnetic monopoles to form. The flow of time in the QR direction does exactly that. Instead of the 10

-35 s of time in cosmic inflation, there is at least 10

-8 s of time flow in the QR direction, resulting in the phase transition being delayed by a factor of >10

27. Physically, the small size of the universe and the length of time in QR time flow mean there is sufficient time for magnetic monopoles of opposite polarity to attract each other and mutually annihilate before time begins to flow in the normal direction.

While inflation results in a flat universe, the physics of the universe remaining flat are less clear. The universe appears to have had a flat geometry as early as we can measure. This requires an exquisite time-varying balance between the energy densities of radiation, matter, dark matter, and dark energy. The current density of the universe needs to be within one part in 10

15 of the critical value for the universe to maintain its flat geometry [

38]. While not impossible that the universe is currently that way, it is a surprising requirement and not a stable situation for even very small deviations from that balance. Recent measurements that showing the dark energy density decreasing over time [

4] call into question a mechanism for this. Space is inherently flat under spacetime duality, regardless of the energy densities of radiation, matter, dark matter, and dark energy.

The standard theory of cosmic inflation predicts that the associated extreme mass motions should generate detectable gravity waves [

42]. Searches for those gravity waves have not found them and have served to further constrain specific models for the amplitude of those gravity waves [

43]. The ~10

25 times slower expansion of the early universe in the g-time model would not generate detectable gravity waves.

The standard inflation model predicts a polarized CMB background. Measurements in 2014 claim to have found this [

44], but subsequent more detailed analysis and additional measurements [

45,

46] showed by 2018 that the earlier results were in error, and that the measured parameter (the tensor-to-scalar power ratio) was not consistent with the main inflation model, although other inflation models (typically with more tunable parameters than the main model with only two) were not ruled out [

44].

This model of the Big Bang based on spacetime duality and g-time explains the flatness and homogeneity of the CMB, as well as the failure to detect monopoles. It also has the advantage of explaining why and when inflation turned on (the flow of time in the QR direction began when matter and antimatter separated), why inflation turned off (time flow transitioned to the normal direction), it has no superluminal velocities (superluminal expansion is an artifact of measuring expansion while ignoring time flow in the QR direction), and the mechanism for inflation is simple to understand and consistent with the failure to detect inflatons or inflation-induced gravity waves. Different theories of inflation have different shapes for the inflaton potential, but in general that shape can be regarded as fine-tuning of the model to achieve consistency with the observed universe. No fine-tuning is required in this model.

5.0. Dark Matter: Origin, Observations, and Predictions

The existence of dark matter is inferred from the amount of mass necessary to keep stars gravitationally bound to their galaxy, and galaxies bound to their galactic cluster. Their rotational velocities are greater than the escape velocity inferred from the amount of observable matter, called baryonic matter in cosmology. Additional evidence for dark matter is the flat geometry of observable space, and the structure of the universe [

47,

48,

49]. The known properties of dark matter are that it only appears to interact gravitationally with normal (baryonic) matter, that the amount of dark matter in the universe is about five times that of normal matter but the ratio varies tremendously by location, and that dark matter is often found in a “halo” around galactic centers, as inferred from the rotational velocity of the stars in those galaxies. There are a variety of theories and postulated particles to account for the observed properties of dark matter, but none have found experimental validation in laboratory measurements (e.g. [

50]) or astronomical observations. Work on weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) [

51,

52], axions [

53,

54,

55], sterile neutrinos [

56,

57,

58], primordial black holes [

59], “fifth force” particles [

60], dark photons [

61] and other potential models for dark matter have consistently failed experimental validation, and the experimental results have primarily served to reduce the solution phase space of the models under test (e.g. [

62]). The properties of dark matter assumed in the ΛCDM model are those empirically determined to best fit observational and theoretical data [

63].

The properties of the dark universes described in

Section 2 match those of dark matter. The five “dark universes” resulting from the three dimensions of g-time and matter/antimatter separation would result in 5 times as much dark matter as baryonic matter, and would only be able to interact with our universe through the shared fabric of spacetime. The matter in the dark universes would have its own distribution across the shared fabric of spacetime and so would be unevenly distributed.

No revisions of the standard model of particle physics are required for the g-time/dark-universe model of dark matter. In contrast, theories of dark matter involving a new particle require a significant revision of the standard model of particle physics, which is problematic since that model has been tremendously successful in its predictions of new particles and quantitative results. With no new particle for dark matter postulated here, the existing body of work in particle physics and the underlying quantum field theory would not need revision.

5.1. 5:1 Ratio of Dark Matter to Matter

Measurements of dark matter are ongoing, and there are difficulties in estimating the amount of normal matter. The next section notes how highly variable the amount of dark matter is, relative to normal matter. Current research focuses on finding dark matter particles and modeling the structure of dark matter in dark matter halos and subhalos, using parameters from the standard model, e.g., [

64]. Estimates of dark matter properties from galaxy rotation curves are typically uncertain to 10% or more, e.g., [

65]. The Hyper Suprime-Cam Subaru Strategic Program (HSC-SSP) spent 6 years to survey 3% of the sky for weak lensing events that allow mapping of dark matter, with only 40% of that data analyzed as of 2023 [

66]. The Dark Energy Survey also detects weak lensing events, and had surveyed about 4% of the sky in its 2022 Data Release 1 [

67].

Difficulties in estimating the amount of normal matter include knowing how much interstellar hydrogen and dust there is and how much mass exists in small black holes. About 50% of normal matter is in the intergalactic medium, and is “notoriously difficult to measure” [

68]. Consequently, those amounts are input parameters to the ΛCDM model and are tuned to best fit other observed data. The current modeled values for the amount of dark matter and normal matter are 0.2589 ± 0.0057 and 0.0486 ± 0.0010 [

63] as the respective fractions of the total mass in the universe. This gives a ratio of 5.33 ± 0.16. There are no widely accepted theories for why there should be five times as much dark matter as normal matter and most theories of dark matter do not address that question, e.g., [

12].

The five dark universes from the g-time model of the Big Bang are expected to have substantially the same amount of material in them, and thus would predict a 5:1 ratio of dark matter to matter. Primordial black holes might result in additional dark matter, increasing the ratio above 5:1. Current measurements constrain the amount of primordial black holes to be less than 10% of the amount of observable matter [

69], resulting in an expected ratio between 5.0:1 and 5.5:1, consistent with the modeled value of 5.33 ± 0.16.

5.2. Uneven Distribution of Dark Matter in the Universe

This model predicts that one would see a 5:1 ratio of dark matter to matter on average across our universe, with localized variations. Some galaxies have over 100 times as much dark matter as visible matter [

70]. In contrast, Galaxy NGC 1277 is at most 5% dark matter [

71], representing the other extreme. The high variability in the ratio is also what you would qualitatively expect from this model, and rules out explanations where dark matter is a property of space itself.

In this model, each of the dark universes has its own distribution across the shared fabric of spacetime, and interacts gravitationally with our universe through that shared fabric of spacetime, but is not able to interact via photon exchange or any other non-gravitational interaction.

5.3. Dark Matter Halos

Dark matter is observed to form halos around the center of many galaxies [

72], bulging outward from the plane of the galaxy, contrary to the naïve expectation that it should behave similar to visible matter in our universe. There is a nuance to explaining dark matter halos, which may account for the dearth of conventional explanations. One must be able to explain how dark matter can form dark matter halos, which have a dark matter distribution largely out of the plane of the visible galaxy, as well as structures such as the Bullet Cluster [

73], where the dark matter is compact and notably offset from the visible matter. The LCDM model does not model the “clumpiness” of dark matter very well. 2023 Measurements showed a significant discrepancy between measurements of the clumpiness of dark matter versus that predicted by ΛCDM using Planck data [

66]. The possibility there may be more than one type of dark matter has been proposed for observational [

23] and theoretical [

74] reasons.

This model explains dark matter halos are due to three of the five dark universes being made of antimatter, with potentially different properties than a matter universe. The physical properties of antimatter on a macroscopic scale have just barely been probed [

75]. Farnes has a model for dark matter based on the assumption that dark matter is antimatter with negative gravitational and inertial mass [

76], which is consistent with the measured properties [

75] and the weak equivalence principle. Calculation and simulation in that model show that that dark matter repels itself gravitationally, hence the bulge of the halo outside the plane of the visible galaxy, and that the antimatter naturally forms halos around matter. In Farnes’ model, the matter and antimatter are in the same universe. Here, they are on different sides of the fabric of spacetime, removing any concern about the two annihilating each other. We then have the simple model that the two regular matter dark universes are responsible for compact dark matter, such as in the center of a galaxy or in the Bullet Cluster, and that the three dark matter antimatter universes provide the dark matter in dark matter halos around visible galaxies. This leads to the testable prediction that the ratio of dark matter in a halo versus total dark matter will vary between galaxies, with the amount in the halo on average about 60% of the total dark matter.

5.4. Dark Matter Can Dissipate Energy from Our Universe

The ability of dark matter to dissipate energy is critical for the current cosmological models to explain the observed maturity of the cosmos. Were dark energy not able to dissipate energy, it would have taken much longer for gravitational coalescence, since the energy of gravitational collapse would otherwise go into heating gas and dust, which would then have a higher pressure to resist gravitational collapse. A specific example of this is black hole mergers. In the “final parsec” problem two rotating black holes will have exhausted the ability of local matter to dissipate rotational energy, resulting in a very slow merger that takes longer than the current age of the universe. Since those mergers are observed to have already occurred, dark matter must be able to interact with itself to dissipate energy, and must be in galactic halos [

77].

A related problem is that conventional theories of dark matter assume the dark matter is in our universe and only interacts energetically via gravity, since that is the only means by which dark matter has been observed. In our universe, during gravitational collapse, gravitational energy can be dissipated as electromagnetic radiation.

The model here implies that dark matter has all the same properties as regular matter, and would be able to dissipate this rotational energy through the same mechanisms regular matter does, just in a separate universe. The ability of the three antimatter dark universes to dissipate energy is an open question, but since the force carrying particles for antimatter (photons) were swept along with the antimatter in the negative g-time direction, there would be electromagnetic interactions in those universes and some ability to dissipate gravitational energy. The two dark universes of matter would have the same properties as matter in our universe and be able to dissipate gravitational energy since heating there would not impact gravitational collapse here.

This model is testable. One can model whether gravitational interaction alone with (nominally) five times as much dark matter as visible matter resolves the energy dissipation problem. A more detailed modeling of this would include specific examples with the actual dark matter density and distribution. Also, one can search for regions of our universe that are anomalously hot, with that heating being due to our universe dissipating energy from gravitational collapse in a dark matter universe. Those regions would be most likely where there is a high density of dark matter and enough material in our universe to dissipate energy, but not so much that it will be undergoing its own gravitational collapse. Similarly, this model predicts that regions of our universe with less dark matter will be hotter and less likely to have undergone gravitational collapse.

5.5. Dark Matter Halo Interactions

In section 5.4 we showed that the gravitational interaction between our universe and a dark universe could dissipate energy and facilitate gravitational collapse in our universe. A related question is how two dark matter universes would interact with each other. A measurement to see if two clouds of dark matter interact with each other electromagnetically provides a partial answer. In our universe, much of the material in a galactic cluster is ionized, so when two galaxies collide the electromagnetic interaction between the charged particles which results in slowing of the ionized material beyond what is expected gravitationally. Looking at the motion of the associated dark matter for each cluster would show whether the dark matter halos had any interactions beyond gravity.

The model here predicts that two interacting clouds of dark matter will only have a gravitational interaction if there are from different dark universes, but they would show slowing due to electromagnetic interaction if they were from the same dark universe. With five dark universes, there is a one-in-five chance to see an electromagnetic interaction when the two dark halos of galactic clusters collide.

That measurement has been done [

78]. The Bullet Cluster is moving away from another galactic cluster after the two collided. The ionized portion of each cluster has slowed down due to electromagnetic interactions. The dark matter halos of each cluster appear to have passed cleanly through each other, with no apparent electromagnetic interaction. This is consistent with the two dark matter halos being from different dark universes.

This model predicts that for a suite of additional measurements of this type, 80% of those measurements will show only the expected gravitational interaction, and 20% will show slowing consistent with electromagnetic interaction. If the percentages are different than predicted here, or there appears to be two different amounts of slowing, that would be evidence for two types of dark matter, nominally due to the three antimatter dark universes and the two matter dark universes. This is a testable prediction using the same techniques as were applied to the Bullet Cluster.

5.6. Dark Matter Binary Star

Given that the dark universes, or at least the two matter ones, will also form stars, it is possible that a binary can form between a star in our universe and a star in a dark universe. This is most likely in a region where there is a high density of stars. This may have been observed.

The pulsar PSR J0514-4002E has a companion with a mass of 2.09 to 2.71 solar masses at the 95% confidence level [

79]. A variety of optical, ultraviolet, and radio measurements failed to detect any visible or radio emissions from the companion. The two options for a compact stellar object which might have no visible or radio emissions are a neutron star or a black hole. The companion’s mass is too large for a neutron star and too small for a black hole, leaving no conventional explanation for the companion.

Further measurements of PSR J0514-4002E would be valuable to rule out a conventional companion with higher confidence. Additional pulsar measurements targeting other dense regions would provide information on how common these objects are, which could be used to test quantitative predictions from this model.

7.0. Summary and Comments

We have shown that a model of the Big Bang and the early universe based on generalized time and spacetime duality explains the observed preponderance of matter over antimatter in our universe; replaces cosmic inflation with a model that explains the same three features of the universe, but without the shortcomings of cosmic inflation; explains the major properties of dark matter and makes testable predictions about additional properties of dark matter; and explains the asymmetry and time dependence of galaxy rotation and makes testable predictions what should be found in more detailed galaxy rotation measurements as a function of redshift. While the results here are largely qualitative, so are the variety of phenomena that can be explained by this model, many of which even lack an accepted qualitative explanation. The predictions from this model are more quantitative, suggesting further development of the model and testing via analysis of existing data and new observations.

G-time and spacetime duality are used with CPT invariance and symmetry between time and space to predict that our universe is one of 6 universes resulting from the Big Bang, with three matter universes having time flowing in the positive direction of g-time along three time axes, and three antimatter universes having time flowing in the negative direction of g-time along the three time axes. CPT invariance causes the flow of time to rotate from the QR direction to the normal direction, at which time all six universes are synchronized in time and can interact gravitationally through a single shared fabric of spacetime.

The matter portions (quarks and electrons along with their gluons and photons) of the hot plasma of the early universe have a time flow in the positive QR direction and the antimatter portions have a time flow in the opposite direction, providing a natural separation of matter and antimatter without violating CPT invariance or other deep physical laws or symmetries.

The ability of time to flow in the QR direction resolves the problematic issue of superluminal expansion inherent in the cosmic inflation model of the early universe. Spacetime duality naturally results in a flat geometry of the universe as the lowest energy state. Time flow in the QR direction means the universe at that time was described by a single quantum state, with homogeneous properties analogous to a superfluid, explaining the homogeneity of the CMB. While magnetic monopoles were present right after the Big Bang, their energy of creation is above that where the three forces become distinguishable, and matter and antimatter can be distinguished as separate things. Only at that lower energy did time begin to flow in the +QR and –QR directions. The magnetic monopoles were too energetic to be swept up in the flow of time for our universe.

The five dark universes have properties that match that of dark matter: about five times as much dark matter as normal matter, dark matter having a highly variable distribution throughout the universe, two types of dark matter corresponding to compact configurations of dark matter and dark matter halos, and the ability to facilitate gravitational collapse in our universe by absorbing energy transferred gravitationally and dissipating it in that dark universe through conventional photon emission. The g-time model predicts 60% of dark matter will exist in dark matter halos, and that dark matter will have rotational properties corresponding to the 5 dark universes. The model for dark matter here does not require any revision of the standard model of particle physics, which would not be the case if one of the dark matter particle searches were successful.

Time dependent measurements of the rotation of galaxies have shown that the asymmetry in galaxy rotation was greater in the early universe, corresponding to a time when interactions with the dark universes had been minimal and the early rotation bias of our universe was more preserved than it is today. The model predicts that measurements of the rotational bias in dark matter will be the opposite of that observed for matter and reduced in amplitude due to opposite bias in two pairs of dark universes, as well as decreasing with time. Similarly, measurements of the early-universe CMB do not show the multipole moments that late universe measurements show, which is the result expected as the rotational properties of the dark universes manifest themselves in our universe as time proceeds. The g-time model predicts that higher redshift measurements of galaxy rotation will further confirm these results.

Observations of increasing accuracy show the need for modifications to the LCDM model. The explanatory power of the model here for a variety of types of cosmological observation, and over the time frame of the early universe to the late universe are support for the underlying ideas of spacetime duality and g-time. There is no other simple model that has the explanatory power shown here, and there are no tunable parameters. A companion paper [

6] outlined how to modify LCDM to include a more accurate model for the expansion of the universe. Gravitational lensing surveys show the same need for the dark matter portion of LCDM [

66]. The results here describe the properties of dark matter in sufficient detail that the dark matter portion of LCDM can also be modified to be more specific and less heuristic than the current implementation.

Efstathiou [

3] concludes his review of the LCDM model by noting that the statistically significant discrepancies between observation and the LCDM model point to the need to consider new physics, particularly for describing and understanding inflation, dark matter, and dark energy. This paper has shown how the concepts of spacetime duality and generalized time potentially provide that new physics to describe inflation and dark matter. A companion paper [

6] used spacetime duality to develop a model of the dynamics of the universe that explains dark energy, matches the observed decrease in the dark energy density with time, and simultaneously resolves the Hubble and

S8 tensions. The success of these two concepts in explaining such a wide variety of cosmological phenomena, as well as other topics in quantum mechanics, string theory, relativity, and gravity, point to the value in testing the predictions here and in the companion papers.

“Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.” ― Richard P. Feynman [

93]