Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hawking´s Cosmology and Superposition State of Universe, MOND and TeVeS

2.1. Big Bang Theory

2.2. Hawking´s Cosmology and String theory

2.3. How a Superposition State Can Have Classical Effects

2.4. Introduction to MOND and TeVeS Theories

3. A Hypothesis on the Physical Existence and the Nature of Dark Matter

- Hawking’s cosmology is a logical combination of two well proven theories, quantum mechanics and Big Bang theory, and thus, it is a good description of the earliest stages of our universe.

- Our universe results from a Big Bang that was in a quantum superposition state at its start, that can be interpreted as 10500 alternative histories in an 11-dimensional space, using the Feynman interpretation of quantum mechanics and String-theory.

- The realization of our universe from the 10500 alternative histories cannot have occurred without a sentient observer.

- Our universe has been realized.

- At least one sentient observer exists, which can have come into being in the universe following the conclusion of Wheeler’s delayed choice experiments.

- Since it is not economical to consider 10500 a fine-tuned number, aimed at creating exactly one universe with sentient being, there still remains a superposition state of more than one alternative histories of the universe. This makes it a multiverse, each universe with sentient beings. This multiverse still exists by means of a state of superposition, which must not necessarily be disturbed by de-coherence, since nothing exists outside the multiverse.

- The other universes in superposition can follow a history comparable with ours that leads to sentient beings, but do not necessarily share all our spatial dimensions in the 11-dimensional space, but do have nearly exactly the same constants of nature. From the delayed choice experiment it follows they all have the same causal status.

- The gravity of these superposed 11-dimensional universes acts together just like the binding force in a deuteron and as a result the gravitational accelerations and potentials caused by baryonic matter in these universes should be added.

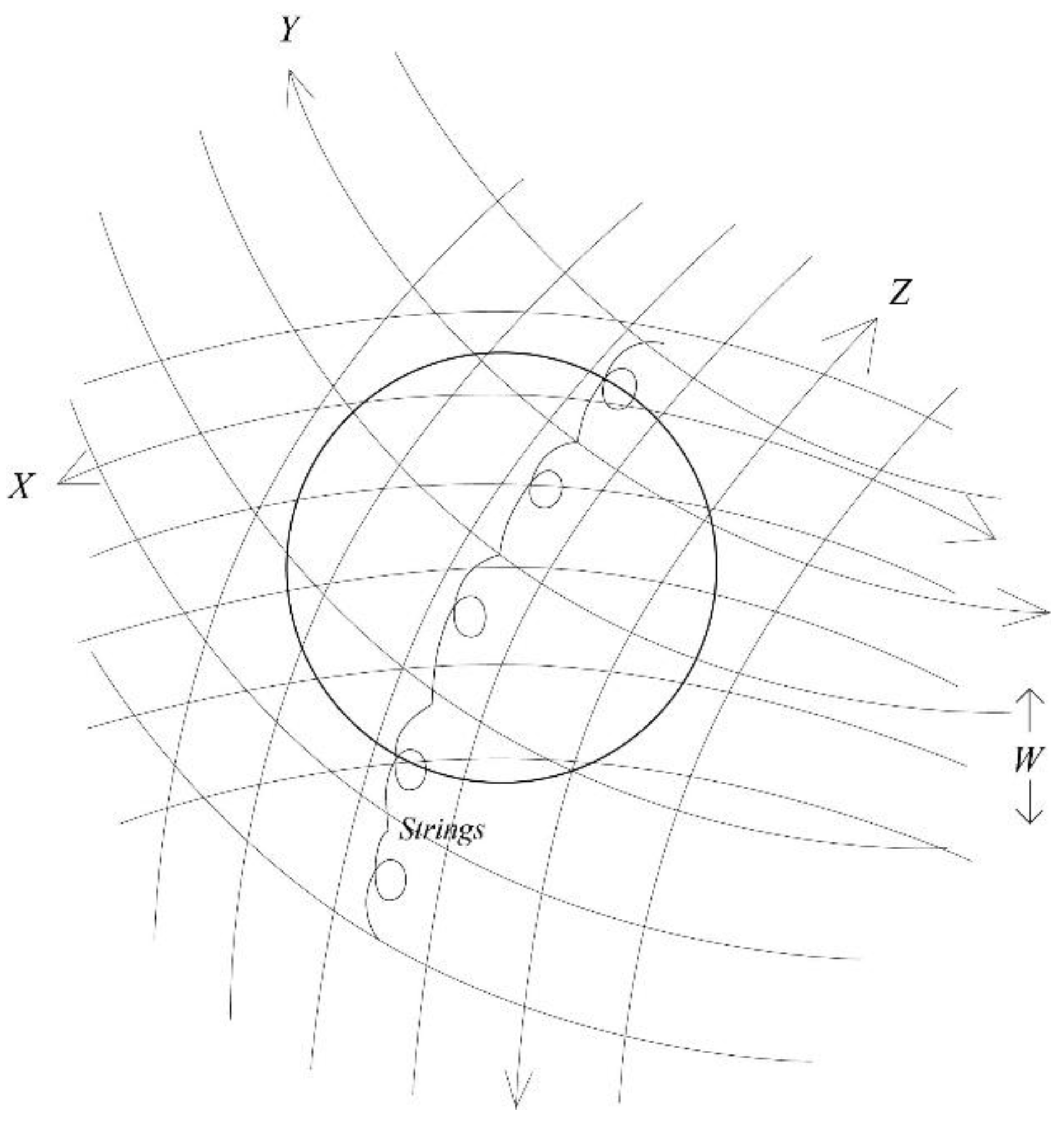

- Since there are more ways to yield partly overlapping universes in an 11-dimensional space than fully overlapping, the odds are that there exist multiple universes that share only one or two dimensions with our universe.

- Gravity acting in our universe resulting from the mass in another one, if it is tightly interwoven with our universe at the smallest scales, appears stretched as a wire-mass because the third dimension is compactified to a GUT-scale that, however, is much larger than the Planck-length. This leads to a linear decrease of the gravitational acceleration as a function of distance from such a stretched mass and hence to a logarithmic potential.

- The existence of multiple universes that share two dimensions with our universe in a state of superposition, forms a natural explanation of what dark matter is and together with the previous step to and explanation for the flat rotation curves at large distances from the centre of galaxies as well as the high velocity dispersions in galaxy clusters.

4. Elaboration of the Hypothesis on the Physical Existence and the Nature of Dark Matter

4.1. Exploring the Logical Consequences of Hawkings’s Cosmology and String Theory

4.2. Geometrical Consequences Leading to a Logarithmic Potential

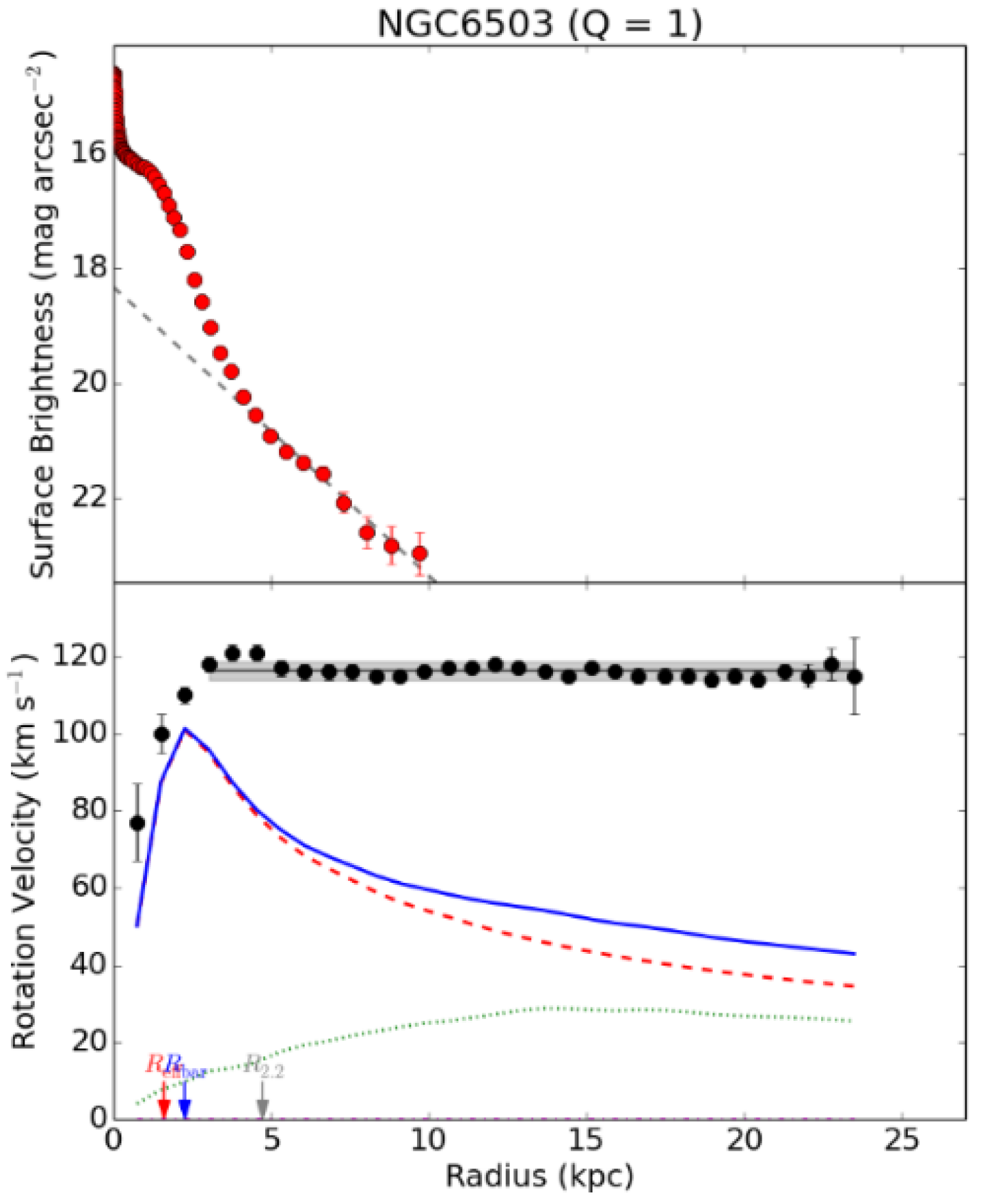

4.3. Interpreting Linear Behaviour of Gravity in Galaxies

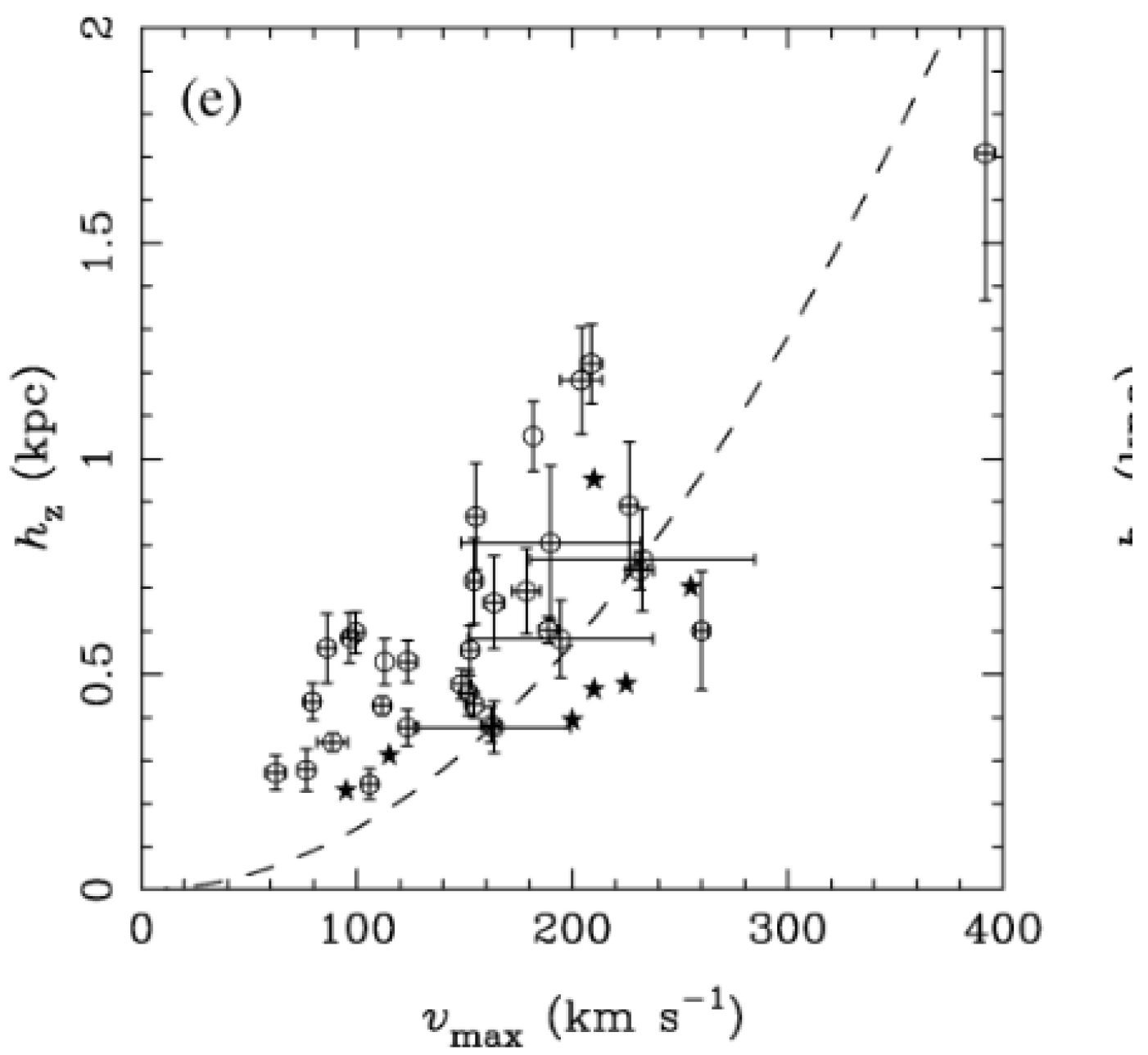

4.4. Linear Mass Density Describing Dark Matter

4.5. Further Considerations and Summary of Chapter 4

5. Testable Predictions

5.1. First Prediction

5.2. Second Prediction

5.3. Third Prediction

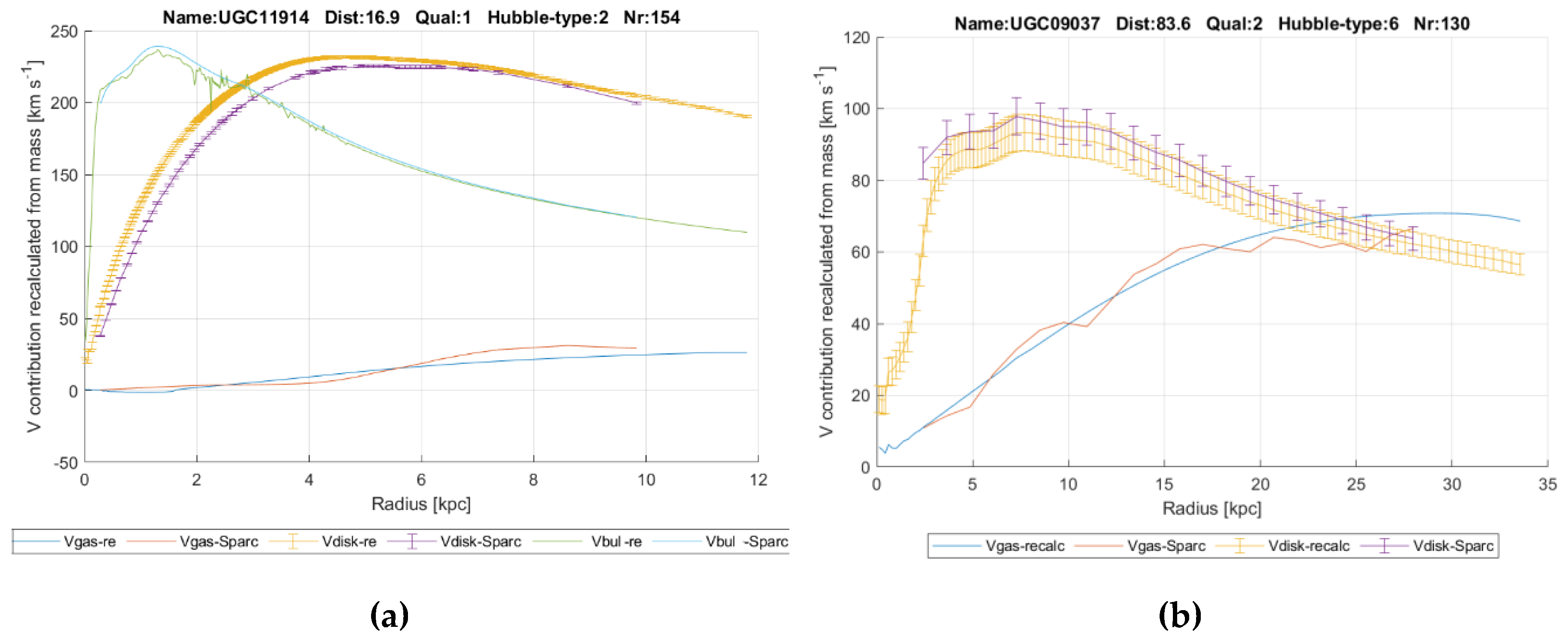

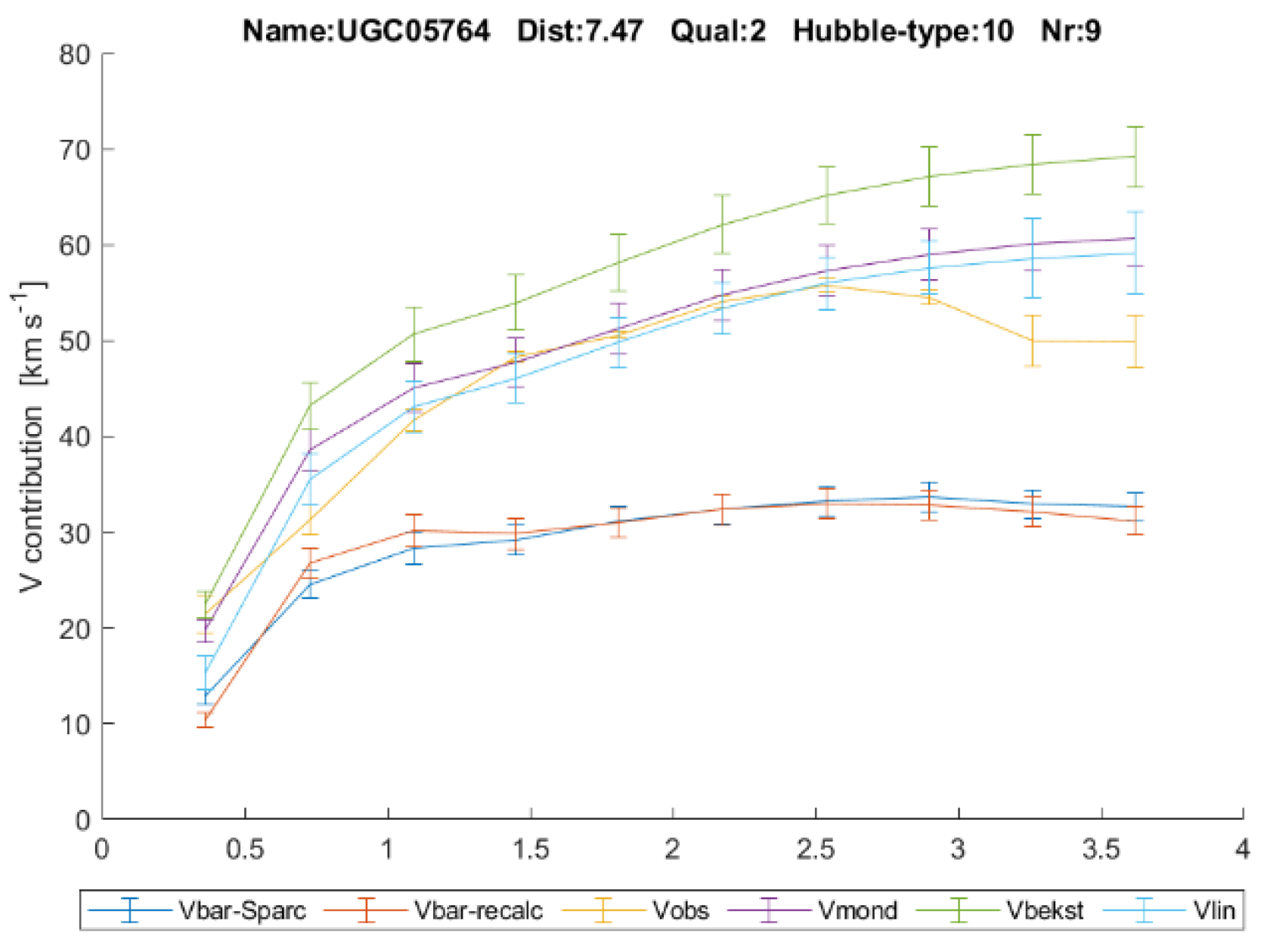

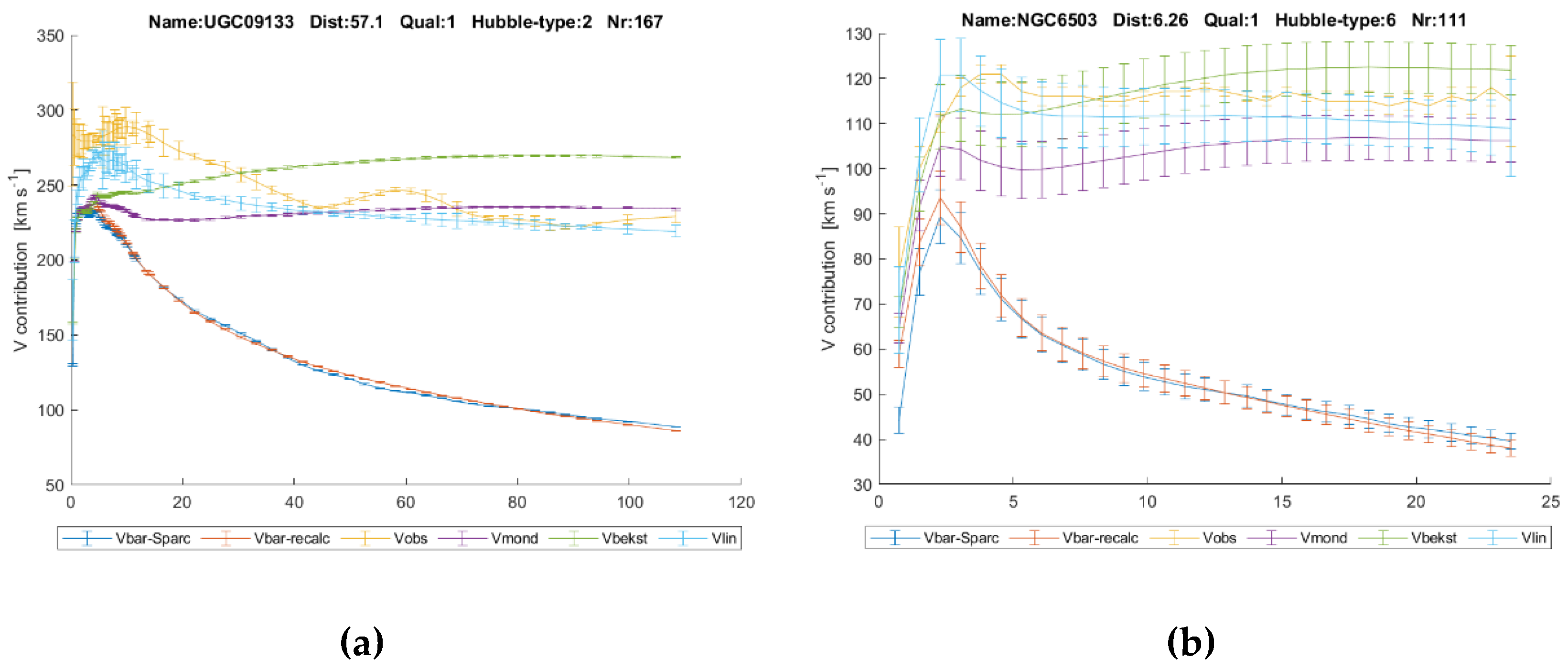

- Calculate the Newtonian gravitational acceleration at R, from the baryonic mass distribution with formulas (17) and (18).

- From the same baryonic mass distribution, already available from step 1), calculate the sum of mass/distance at R, only taking the mass density in the rotation plane into account.

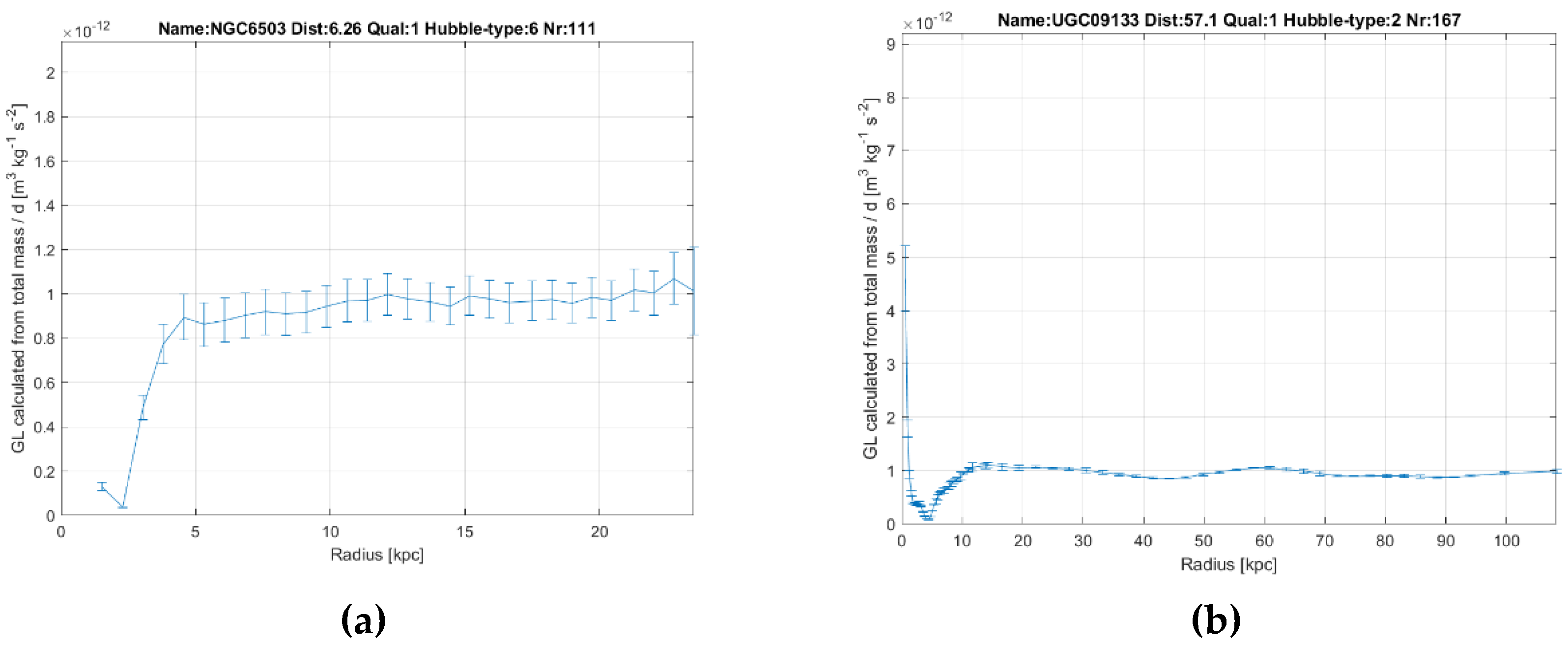

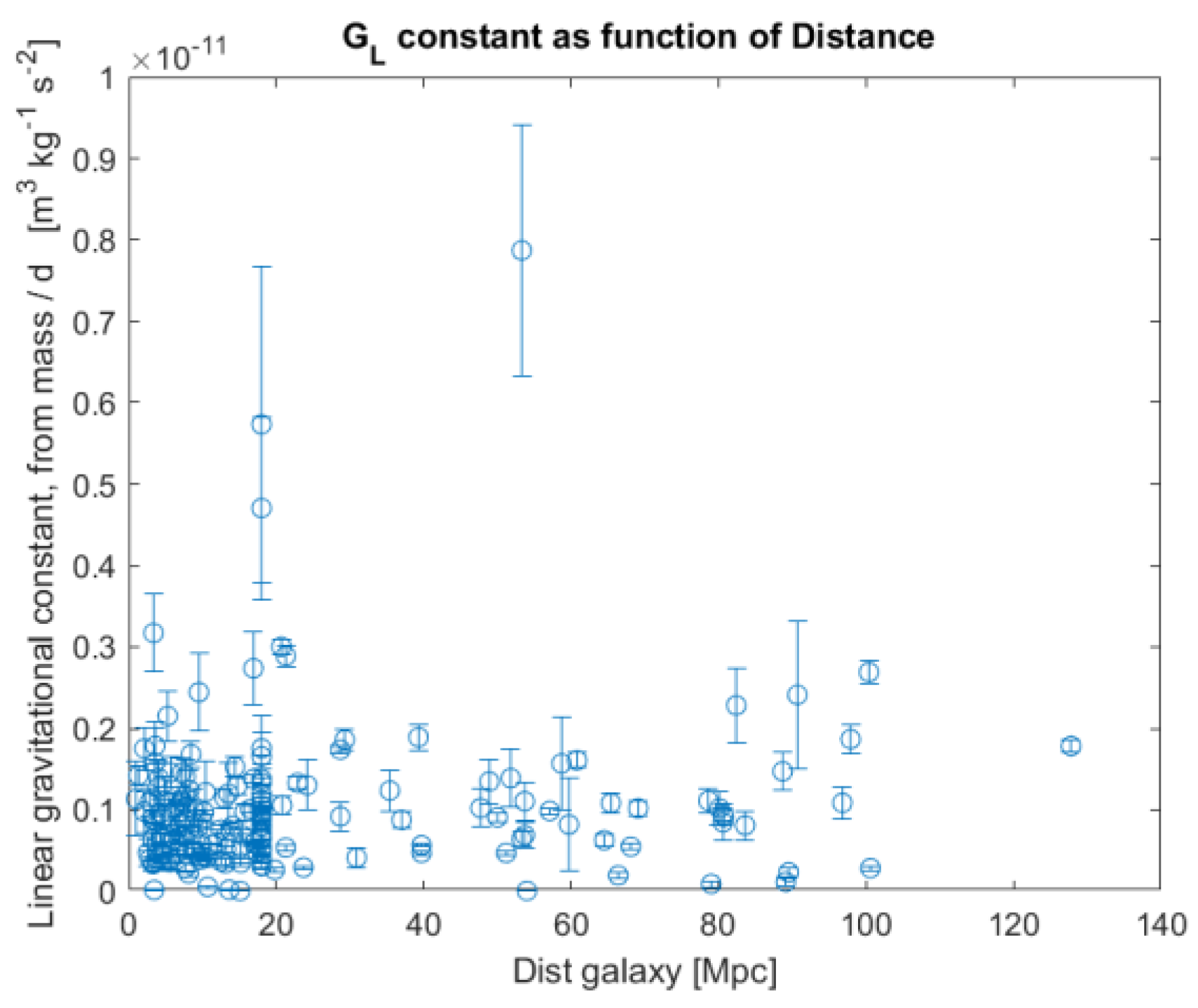

- Assuming a value GL ≈ 1.1 x 10-12 [m3 kg-1 s-2], calculate the additional linear gravitational acceleration with formulas (8) and (19).

- Add the Newtonian gravitational acceleration to the linear gravitational acceleration and compute the rotation velocity.

5.4. Fourth Prediction

5.4.1. Clusters

5.4.2. Effect on Galaxy Formation

5.5. Fifth Prediction

5.6. Sixth Prediction

5.7. Seventh Prediction

6. Conclusions and Suggestions for Further Work

Data Availability

Annexes (in a Separate Document)

References

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophys. J. 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, I.; Zhao, H. From Galactic Bars to the Hubble Tension: Weighing Up the Astrophysical Evidence for Milgromian Gravity. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Relativistic gravitation theory for the modified Newtonian dynamics paradigm. Physical Review D 2004, 70, 083509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E.P. Emergent Gravity and the Dark Universe. SciPost Phys. 2017, 2, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Civita, T. 1915 Rend. Acad. Lincei 28 101.

- Santos, N.O. , Wang A., Cylindrically Symmetric Fields in General Relativity. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.07353v1. [Google Scholar]

- Hartle, J.B.; Hawking, S.W. Wave function of the Universe. Phys. Rev. D 1983, 28, 2960–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking S.W, Mlodinow L. 2010, The Grand Design (Bantam Press and Transworld Publishers, London, United Kingdom).

- Mistele, T.; McGaugh, S.; Lelli, F.; Schombert, J.; Li, P. Indefinitely Flat Circular Velocities and the Baryonic Tully–Fisher Relation from Weak Lensing. Astrophys. J. 2024, 969, L3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. (German translation) Das Hässliche Universum, Warum unsere Suche nach Schönheit die Physik in die Sackgasse führt (4th edition; S. FISCHER Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) (original title: Lost in Math, How Beauty leads Physics astray, Basic Books, New York, USA). L: FISCHER Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) (original title, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lelli, F.; McGaugh, S.S.; Schombert, J.M. SPARC: MASS MODELS FOR 175 DISK GALAXIES WITH SPITZER PHOTOMETRY AND ACCURATE ROTATION CURVES. Astron. J. 2016, 152, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PHOTOMETRY AND ACCURATE ROTATION CURVES, AJ, 152:157 (14pp), http://astroweb.cwru.edu/SPARC.

- Starkman, N.; Lelli, F.; McGaugh, S.; Schombert, J. A new algorithm to quantify maximum discs in galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2018, 480, 2292–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuvel E. P., J. Van den 2012, Oerknal, Oorsprong van de eenheid van het heelal (Big Bang, Origin of the unity of the universe)(Veen Magazines B.V, Diemen, The Netherlands).

- Everett, H. "Relative State" Formulation of Quantum Mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1957, 29, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B.S. Quantum Theory of Gravity. I. The Canonical Theory. Phys. Rev. B 1967, 160, 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J. , Schroeter D.F. 2018, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

- Ma, X.-S.; Kofler, J.; Zeilinger, A. Delayed-choice gedanken experiments and their realizations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strominger, A.; Vafa, C. Microscopic origin of the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy. Phys. Lett. B 1996, 379, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J. The large $N$ limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1999, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S. The fuzzball proposal for black holes: an elementary review. Fortschritte der Phys. 2005, 53, 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H.A. The Meson Theory of Nuclear Forces. Part II. Theory of the Deuteron. Phys. Rev. B 1940, 57, 390–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, V.L.; Landau, L.D. On the theory of superconductivity. ZhETF 1950, 20, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, A.H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Phys. Rev. D 1981, 23, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Kamenetskii, M.D.; Prakash, S. DNA theoretical modeling. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupa, P.; et al. Asymmetrical tidal tails of open star clusters: stars crossing their cluster's path challenge Newtonian gravitation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2022, 517, 3613–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, G. (Dutch translation) De Olifant in het Universum, Donkere materie, mysterieuze deeltjes en de samenstelling van ons heelal (Fontaine Uitgevers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) (original title: The Elephant in the Universe, Harvard University Press, 2021). 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Platschorre, A.D. On Covariant Emergent Gravity, bachelor thesis, Delft University, The Netherlands, 2019.

- Modesto, L.; Zhou, T.; Li, Q. Geometric Origin of the Galaxies’ Dark Side. Universe 2023, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.; Kolb, E.W. Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces that Shape the Universe. Phys. Today 2000, 53, 67–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldazabal, G.; Franco, S.; E Ibáñez, L.; Rabadán, R.; Uranga, A.M. Intersecting brane worlds. J. High Energy Phys. 2000, 2001, 047–047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüst, D. Intersecting brane worlds—a path to the standard model? Class. Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, S1399–S1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, A.G. Contributions to a British Association Discussion on the Evolution of the Universe. Nature 1931, 128, 704–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. THE MINIMAL LENGTH AND LARGE EXTRA DIMENSIONS. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2004, 19, 2727–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spallucci, E. Fontanini, M. (2005). Zero-point length, extra-dimensions and string T -duality, arXiv:gr-qc/0508076v2.

- Liu, H. (2004), Compactified Newtonian Potential and a Possible Explanation for Dark Matter, https://arxiv.org/abs/hep-ph/0312200.

- Randall, L.; Sundrum, R. Large Mass Hierarchy from a Small Extra Dimension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 3370–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergshoeff, E.A.; Riccioni, F. Wrapping rules (in) string theory. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maartens, R. Brane-World Gravity. Living Rev. Relativ. 2004, 7, 1–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croon, D.; Gonzalo, T.E.; Graf, L.; Košnik, N.; White, G. GUT Physics in the Era of the LHC. Front. Phys. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.J.; Mao, S.; White, S.D.M. The formation of galactic discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 295, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.D.; Tresaco, E.; Riaguas, A. Orbital analysis in the gravitational potential of elongated asteroids. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2024, 369, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begelman, M. , Rees, M. 2021, Gravity’s Fatal Attraction, Black Holes in the Universe (3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

- Darling, D. (Dutch translation) Zwaartekracht, van Aristoteles tot Einstein en verder (Uitgeverij Veen Magazines, Diemen, The Netherlands), (original title: Gravity’s Arc, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, USA, 2006). e, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.J.; Conroy, C.; Hernquist, L. A tilted dark halo origin of the Galactic disk warp and flare. Nat. Astron. 2023, 7, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

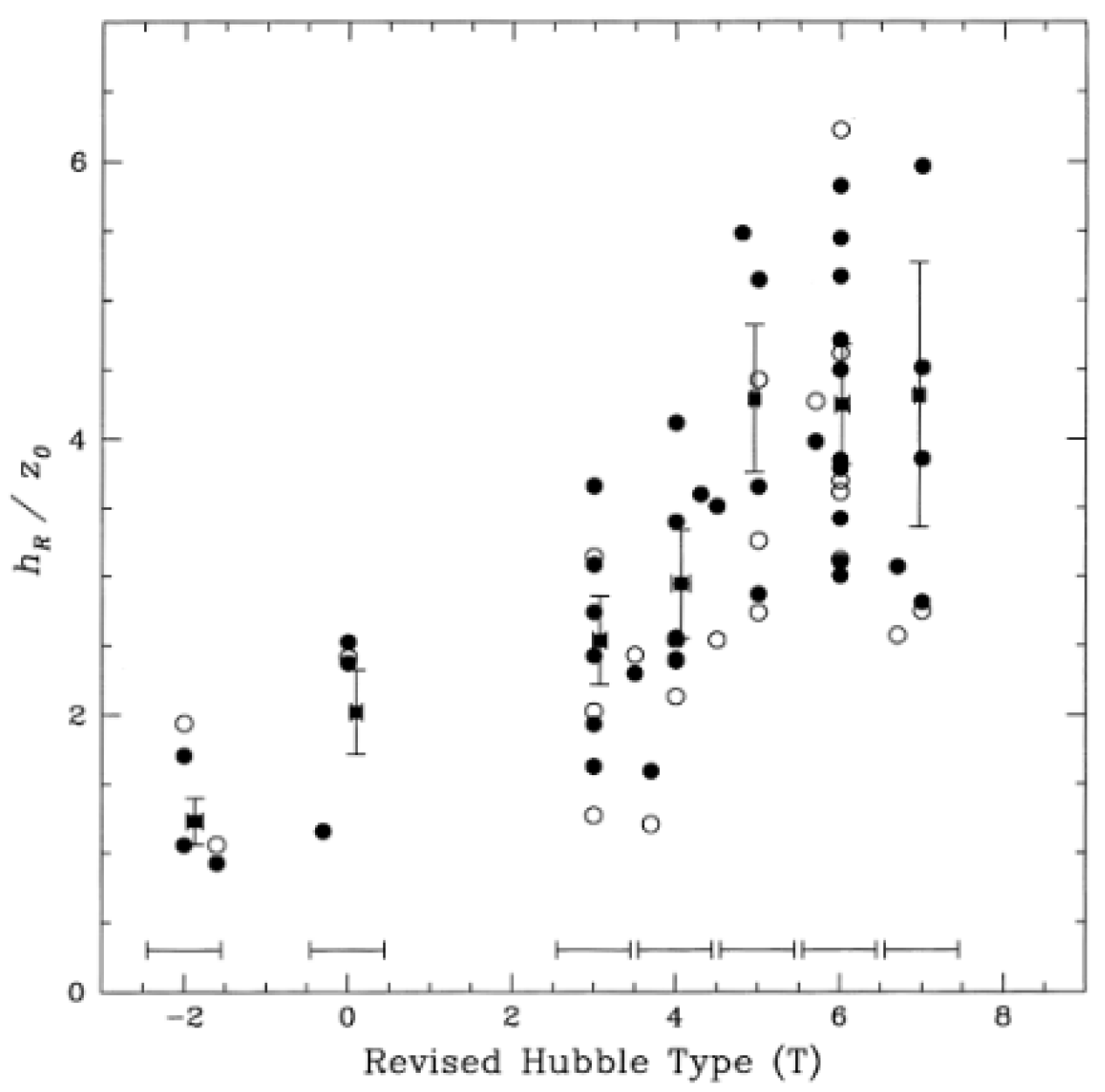

- Kregel, M. , Kruit P. C., De Grijs R. Flattening and truncation of stellar discs in edge-on spiral galaxies Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2002, 334, 646–668. [Google Scholar]

- Martinsson, T P.K.; et al. The DiskMass Survey. X. Radio synthesis imaging of spiral galaxies. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 585.

- Ku, H.H. Notes on the use of propagation of error formulas, Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards 70C (4). 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Kruit, P.C. van der, Freeman K.C. Galaxy disks, Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sparke, L.S. , Gallagher S. 2007, Galaxies in the Universe, An introduction (2nd ed; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom). 2007. [Google Scholar]

- de Grijs, R. The global structure of galactic discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 299, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Casertano, S.; Jones, D.O.; Murakami, Y.; Anand, G.S.; Breuval, L.; et al. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s−1 Mpc−1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. Astrophys. J. 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. MOND in galaxy groups. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian,Y et al, 2021, MASS-VELOCITY DISPERSION RELATION IN HIFLUGCS GALAXY CLUSTERS https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.00992.

- Heisler, J., Tremaine, S., & Bahcall, J. N. 1985, ApJ, 298, 8.

- Saff, E.B. & Totik V. (2024), Logarithmic Potentials with External Fields, Springer Nature Verlag, Switzerland.

- Labbé, I.; van Dokkum, P.; Nelson, E.; Bezanson, R.; Suess, K.A.; Leja, J.; Brammer, G.; Whitaker, K.; Mathews, E.; Stefanon, M.; et al. A population of red candidate massive galaxies ~600 Myr after the Big Bang. Nature 2023, 616, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, R.H. Forming galaxies with MOND. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 386, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, S.S.; Schombert, J.M.; Lelli, F.; Franck, J. Accelerated Structure Formation: The Early Emergence of Massive Galaxies and Clusters of Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2024, 976, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupa, P. (2016) The observed spatial distribution of matter on scales ranging from 100kpc to 1Gpc is inconsistent with the standard dark-matter-based cosmological models. https:// https://arxiv.org/abs/1610.03854.

- Zeilinger, A. Experiment and the foundations of quantum physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, S288–S297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlab 2021, MATLAB® is a registered trademark and MATLAB Grader is a trademark of The MathWorks, Inc, Natick, USA.

| MOND vs. glinear+gbar | TeVeS vs. glinear+gbar | |

|---|---|---|

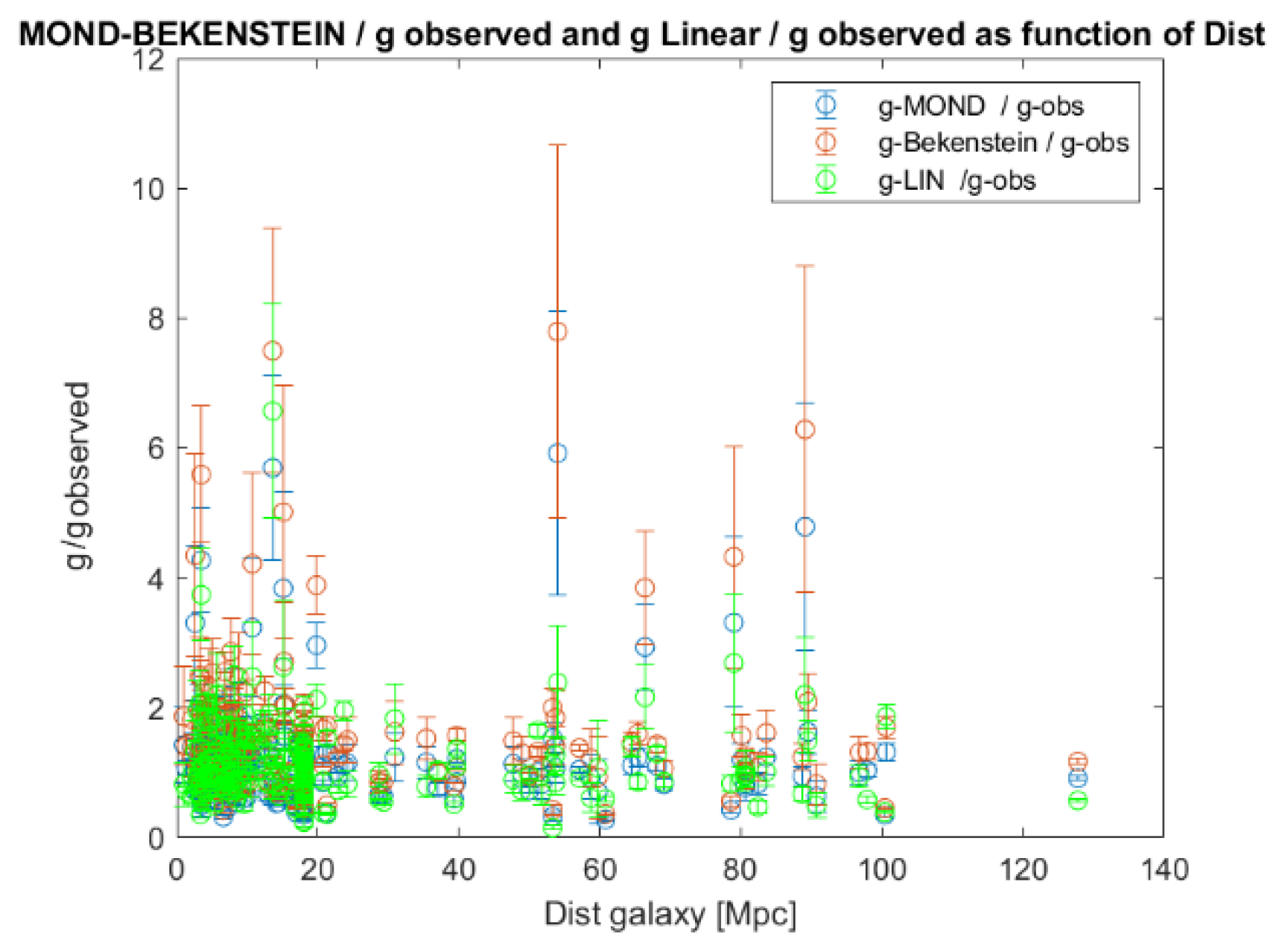

| Prediction one GL | 10 % | 17 % |

| Prediction 175 values for GL | 15 % | 22 % |

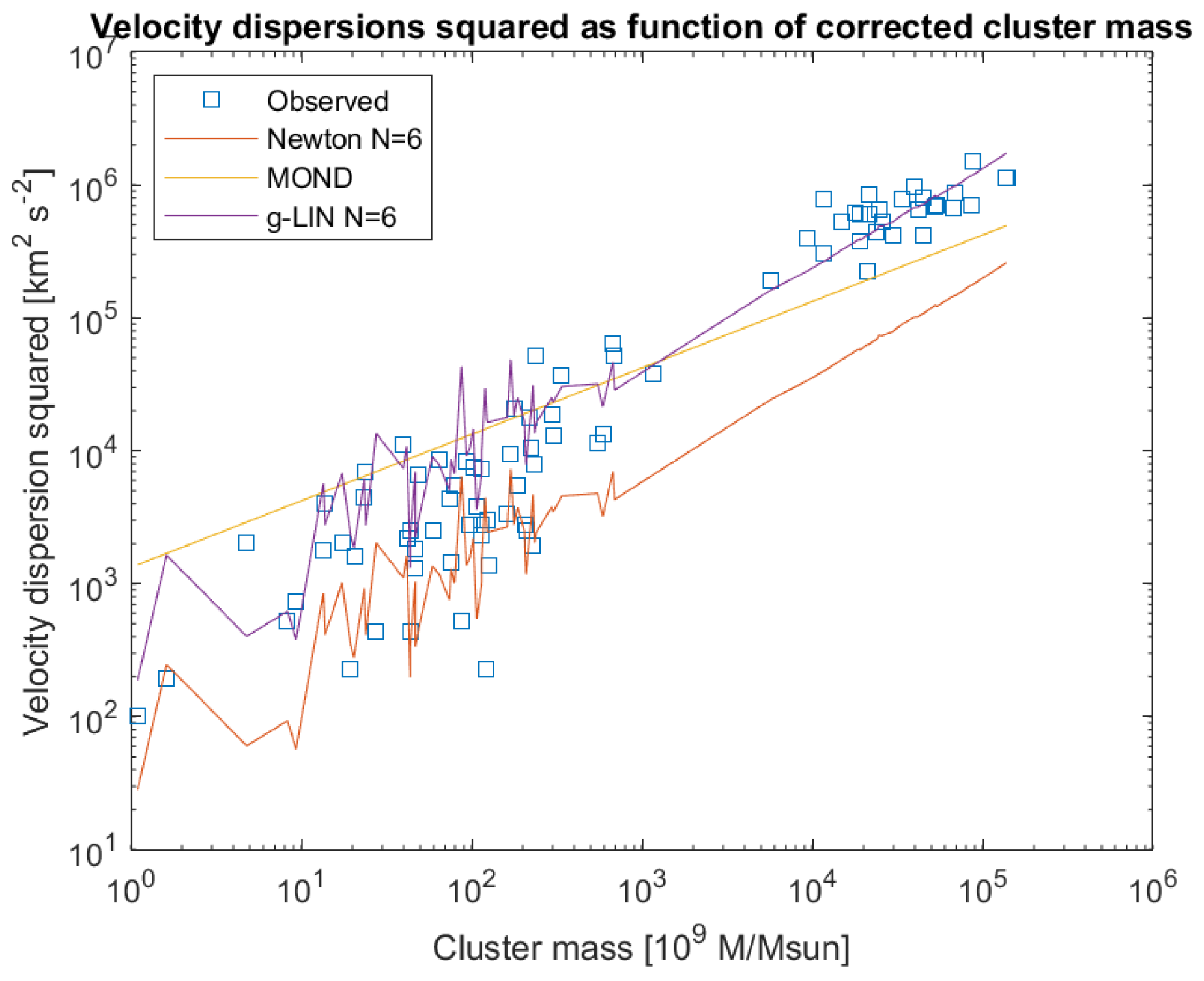

| Comparison | Newton | MOND |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction logarithmic potential with N = 6 | 57 % | 44 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).