Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Plant Materials and Extraction Method

2.3. HPLC-DAD and UPLC-ESI-TOF-MS Chromatographic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

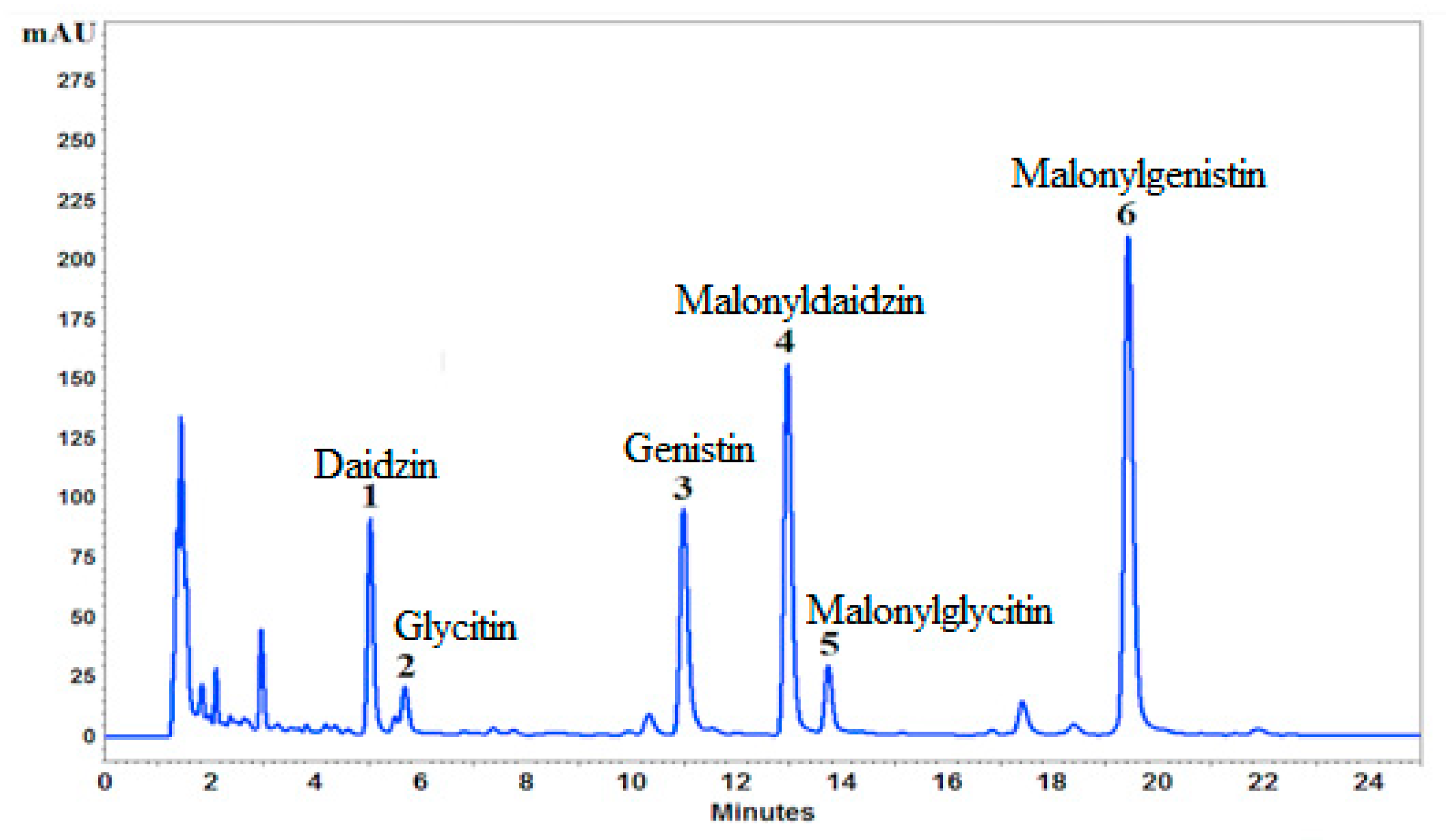

3.1. Isoflavones Content in Soybeans

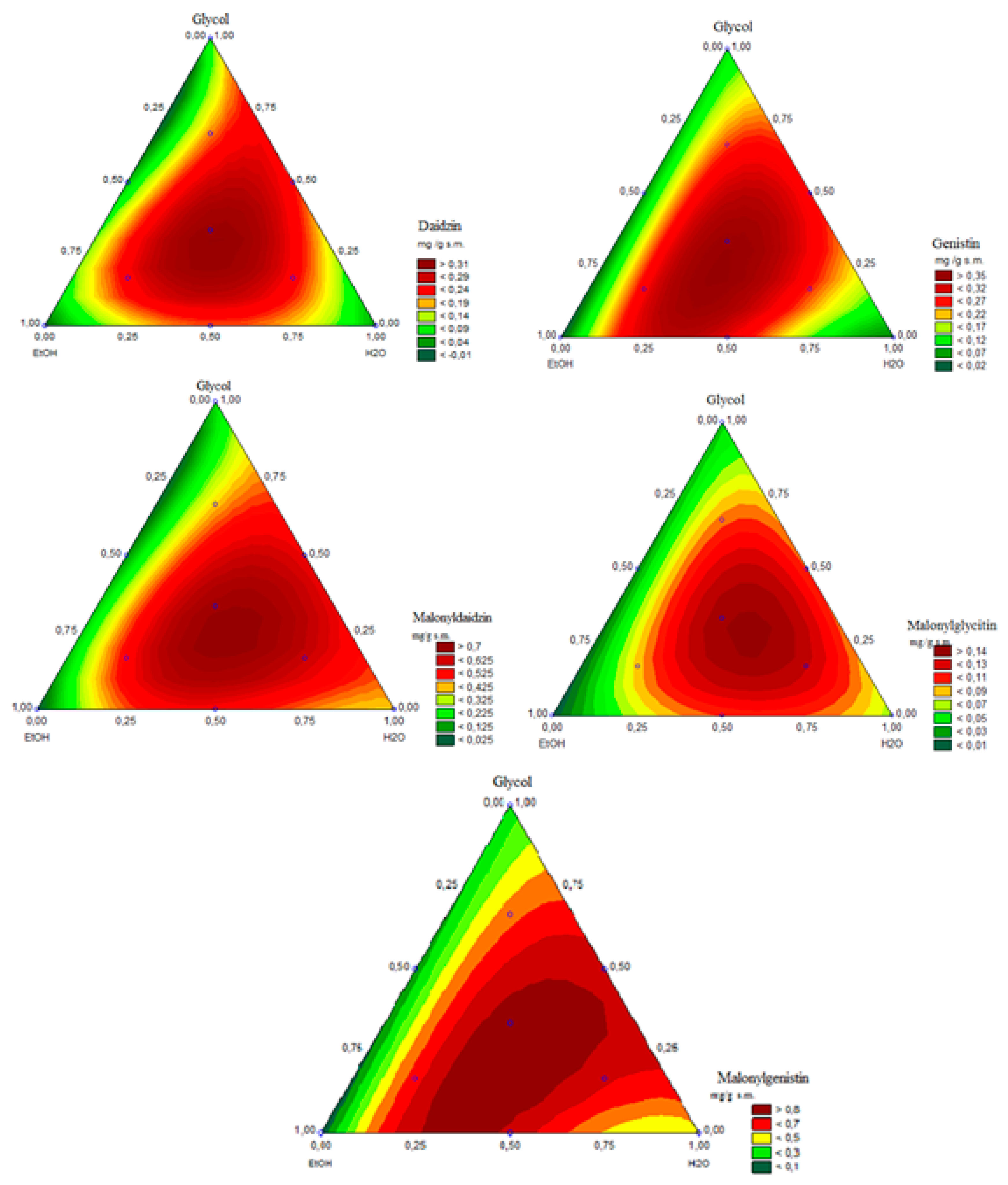

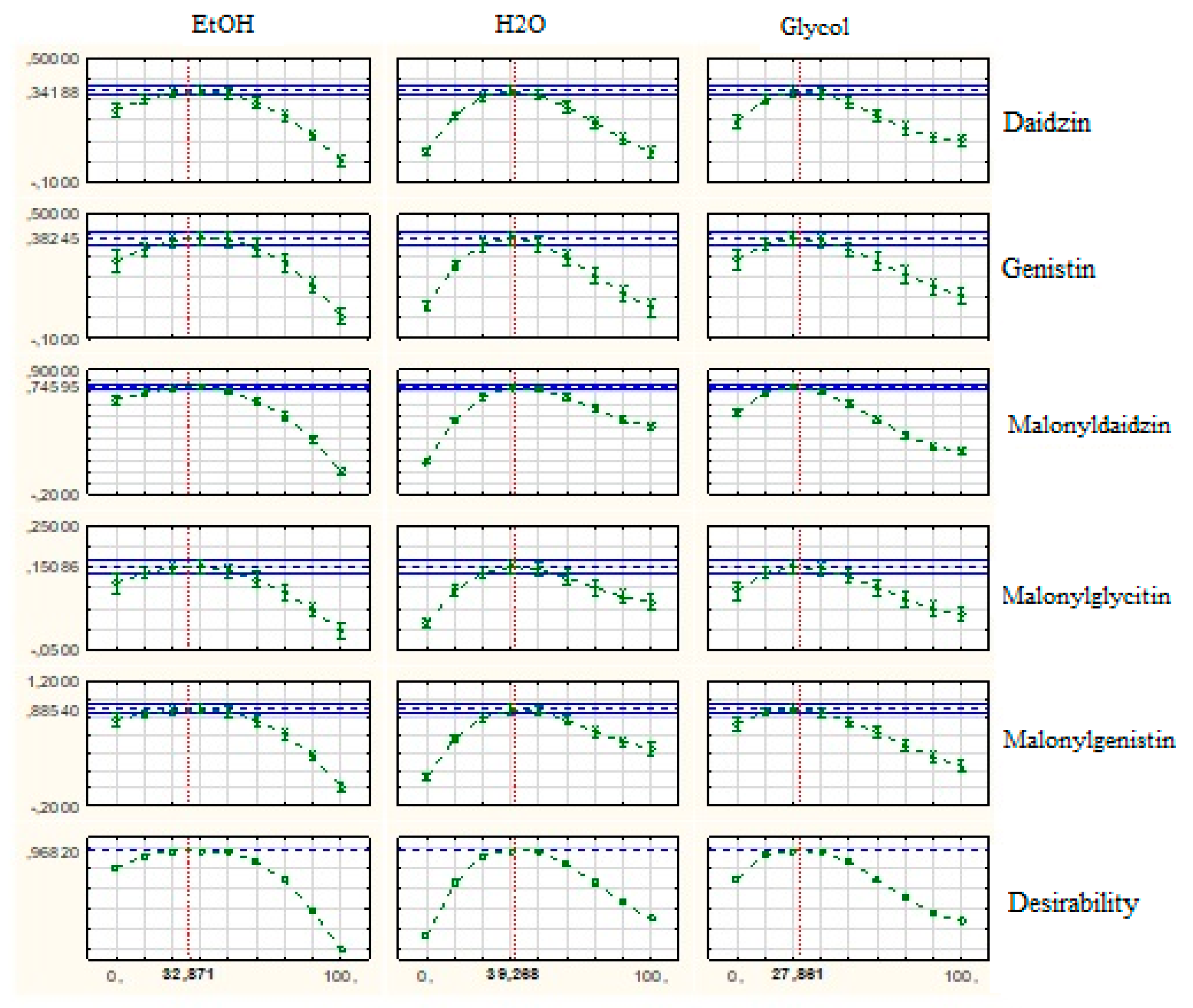

3.3. Regression Models and Response Surfaces

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Staniak, M., Stępień, A., Czopek, K. (2018), Response of common soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) to selected abiotic stresses. Studies and reports IUNG-PIB, 57(11): 63-74. [CrossRef]

- Volkova, E., & Smolyaninova, N. (2024). Analysis of world trends in soybean production. In BIO Web of Conferences (Vol. 141, p. 01026). EDP Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Ademiluyi, A.O., Oboh, G., Boligon, A.A, Athayde, M.L., (2014), Effect of fermented soybean condiment supplemented diet on α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Funct. Foods, 9, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.R., Pereira, M.J., Azevedo, J., Gonçalves, R.F., Valentão, P., Guedes de Pinho, P., Andrade, P.B., (2013), Glycine max (L.) Merr., Vigna radiata L. and Medicago sativa L. sprouts: a natural source of bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 50, 167–175. [CrossRef]

- Alu’datt, M.H., Rababah, T., Ereifej, K., Alli, I., (2013), Distribution, antioxidant, and characterization of phenolic compounds in soybeans, flaxseed and olives. Food Chem., 139 pp. 93-99. [CrossRef]

- Vogiatzoglou A., Mulligan A. A., Lentjes M. A. H., Luben R. N., Spencer J. P. E., Schroeter H., Khaw K., Kuhnle G. G. C., (2015), Flavonoid Intake in European Adults (18 to 64 Years), PLOS ONE, (10): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H., Hwang, S.R., Lee, Y.H., Kim, K., Cho, K.M., Lee, Y.B., (2015), Changes occurring in compositions and antioxidant properties of healthy soybean seeds [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] and soybean seeds diseased by Phomopsis longicolla and Cercospora kikuchii fungal pathogens. Food Chem., 185 pp. 205-211. [CrossRef]

- Prasain, JK., Carlson, SH., Wyss, JM., (2010) Flavonoids and Age-Related Disease: Risk, benefits and critical windows ISSN: 0378-5122, Vol: 66, Issue: 2, Page: 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Garrett R. D., Rueda X., Lambin E. F. (2014), Globalization’s unexpected impact on soybean production in South America: linkages between preferences for non-genetically modified crops, eco-certifications, and land use. Environ. Res. Lett. 8: 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Ge, Y., Han, F., Li, B., Yan, S., Sun, J., Wang, L., (2014), Isoflavone content of soybean cultivars from maturity group 0 to VI grown in Northern and Southern China. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 91 pp. 1019-1028. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S., Pandey A. K., (2013), Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, Sci. World J. Volume 2013. [CrossRef]

- Busch Ch., Burkard M., Leischner Ch., Lauer U. M., Frank J. Venturelli S., (2015), Epigenetic activities of flavonoids in the prevention and treatment of cancer, BioMed Central. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, A., Yamazaki, Y., Yamashita, K., Takahashi, S., Nakayama, T., Yazaki, K., (2016), Developmental and nutritional regulation of isoflavone secretion from soybean Roots. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 80 pp. 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Hai Liu R., (2013), Dietary Bioactive Compounds and Their Health Implications. J. Food Sci., Vol. (78, S1): A18-A23. [CrossRef]

- Batra P., Sharma A. K., (2013), Anti-cancer potential of flavonoids: recent trends and future Perspectives. Biotech, (3): 439-446. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J., Chung, M.J., Kim, H., Jung, M.Y., (2015), High resolution LC-ESI-TOF-mass spectrometry method for fast separation, identification, and quantification of 12 isoflavones in soybeans and soybean products. Food Chem., 176, pp. 254-262. [CrossRef]

- Alam M. A., Subhan N., Rahman M. M., Uddin S. J., Reza H. M., Sarker S. D., (2014), Effect of Citrus Flavonoids, Naringin and Naringenin, on Metabolic Syndrome and Their Mechanisms of Action, American Society for Nutrition, Adv. Nutr. (5):404,413. [CrossRef]

- Britz, S.J., Schomburg, C.J., Kenworthy, W.J., (2011), Isoflavones in seeds of field-grown soybean: variation among genetic lines and environmental effects, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 88 pp. 827-832. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z., Si, X., Zhang, Z., Li, G., Cai, Z., (2012), Compositional study of different soybean (Glycine max L.) varieties by 1H NMR spectroscopy, chromatographic and spectrometric techniques. Food Chem. 135, 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Lee W.C., Yusof S., Hamid N.S.A., Baharin B.S. (2006), Optimizing conditions for hot water extraction of banana juice using response surface methodology (RSM). J. Food Eng.,75 (4), 473-479. [CrossRef]

- Jeszka-Skowron M., Flaczyk E., Kobus-Cisowska J., Kośmider A., Górecka D. (2014) Optimizing process of extracting phenolic compounds having antiradical activity from white mulberry leaves by means of response surface methodology (RSM). Food Science Technology Quality. [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y.S., Yoon, W.J., Hwang, J.B., Park, H.J., Seo, H.J., Ha, J., (2015), Rapid method for the determination of 14 isoflavones in food using UHPLC coupled to photo diode array detection, Food Chem., 187 pp. 391-397. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y.H., Kim B., Hwang S.R., Kim K., Lee J.H., (2018), Rapid characterization of metabolites in soybean using ultra high performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-Q-TOFMS/MS) and screening for α-glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant properties through different solvent systems. J Food Drug Anal. ;26(1):277-291. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H., Cho, K.M., (2012), Changes occurring in compositional components of black soybeans maintained at room temperature for different storage periods. Food Chem., 131, pp. 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Szymczak G., Wójciak-Kosior M., Sowa I., Zapała K., Strzemski M., Kocjan R., (2017), Evaluation of isoflavone content and antioxidant activity of selected soy taxa. J. Food Compos. Anal. 57, 40–4. [CrossRef]

- Mai, X., Liu, Y., Tang, X., Wang, L., Lin, Y., Zeng, H., Luo, L., Fan, H., & Li, P. (2020), Sequential extraction and enrichment of flavonoids from Euonymus alatus by ultrasonicassisted polyethylene glycol-based extraction coupled to temperature-induced cloud point extraction. Ultrasonics sonochemistry 66, 105073. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Zhao, D., He, J., Ma, K., Zhu, J., Liu, J.,... & Li, T. (2025), Protective fractionation of highly uncondensed lignin with high purity and high yield: new insights into propanediol-blocked lignin condensation. Green Chemistry. [CrossRef]

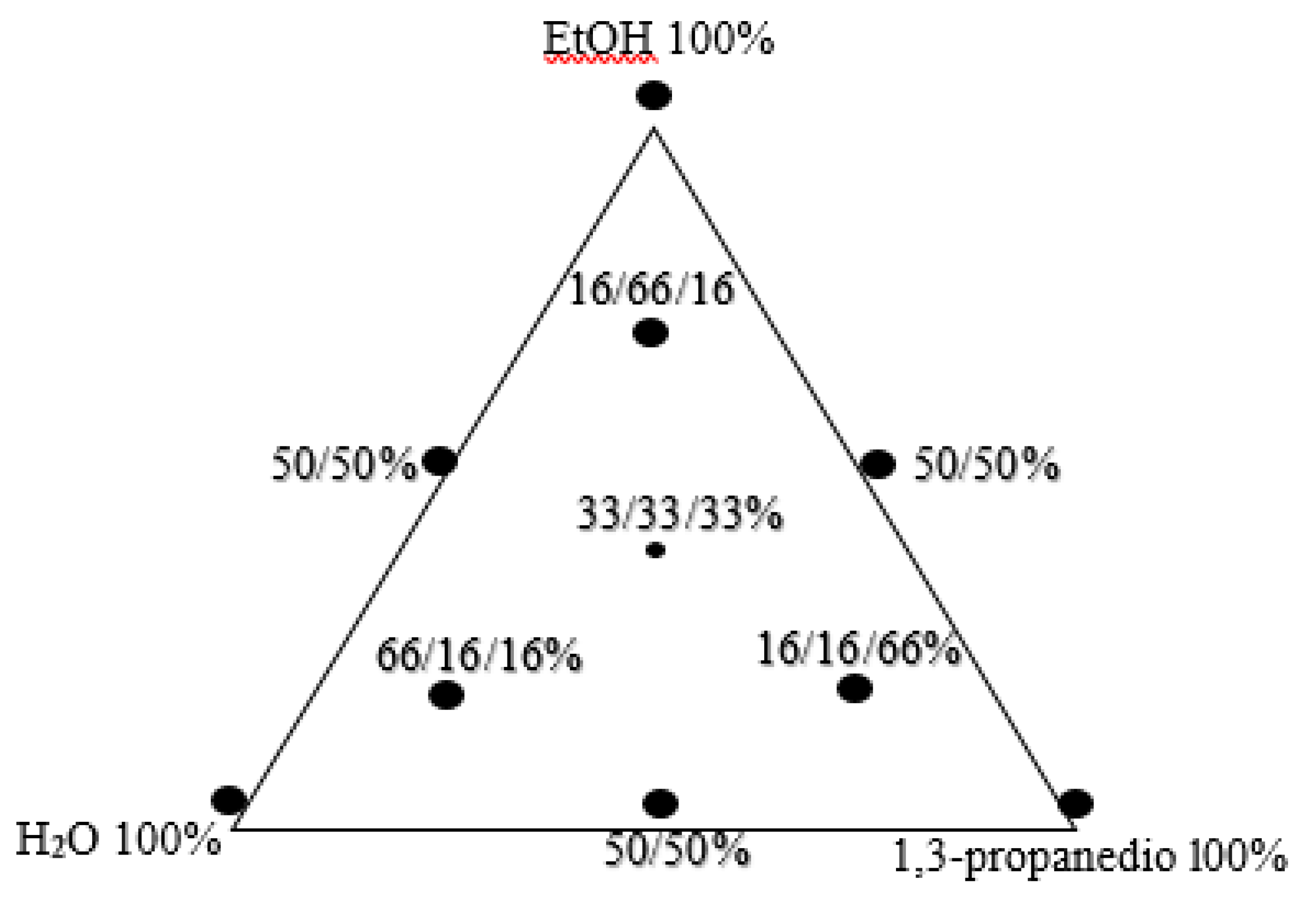

| No. | EtOH % |

Glycol % |

H2O % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 3. | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 4. | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| 5. | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| 6. | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| 7. | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 |

| 8. | 66.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 |

| 9. | 16.7 | 16.7 | 66.7 |

| 10. | 16.7 | 66.7 | 16.7 |

| Type of solvent | Isoflavone content | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EtOH % |

Glycol % |

H2O % |

Daidzin mg/g |

Genistin mg/g |

Malonyldaidzin mg/g |

Malonylglycitin mg/g |

Malonylgenistin mg/g |

| 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.44 ± 0.00 |

| 0 | 100 | 0 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.23 ± 0.00 |

| 50 | 0 | 50 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.76 ± 0.01 |

| 50 | 50 | 0 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| 0 | 50 | 50 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 1.14 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.74 ± 0.04 |

| 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 0.32 ± 0.00 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.04 |

| 66.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.00 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.70 ± 0.04 |

| 16.7 | 16.7 | 66.7 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.00 |

| 16.7 | 66.7 | 16.7 | 0.21 ± 0.00 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

| nd- not detected | |||||||

| solvents - linear factors |

coefficient | standard error | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daidzin | |||

| (A) EtOH | 0.005976 | 0.012274 | 0.635129 |

| (B) H₂O | 0.046436 | 0.013484 | 0.004860 |

| (C) Glycol | 0.104128 | 0.012274 | 0.000002 |

| AB | 0.743744 | 0.065217 | 0.000000 |

| BC | 0.626670 | 0.065217 | 0.000001 |

| ABC | 3.578962 | 0.396505 | 0.000001 |

| AC(A-C) | 1.013699 | 0.219349 | 0.000589 |

| BC(B-C) | -0.390842 | 0.218512 | 0.098924 |

| Genistin | |||

| (A)EtOH | 0.010618 | 0.017566 | 0.555965 |

| (B)H₂O | 0.048974 | 0.019273 | 0.024604 |

| (C)Glycol | 0.105408 | 0.016896 | 0.000030 |

| AB | 1.095919 | 0.093359 | 0.000000 |

| BC | 0.782245 | 0.093849 | 0.000001 |

| ABC | 3.070757 | 0.570956 | 0.000126 |

| AB(A-B) | 1.015913 | 0.272909 | 0.002558 |

| Malonyldaidzin | |||

| (A)EtOH | 0.005035 | 0.013116 | 0.707798 |

| (B)H₂O | 0.395916 | 0.014408 | 0.000000 |

| (C)Glycol | 0.182057 | 0.013116 | 0.000000 |

| AB | 1.411829 | 0.069688 | 0.000000 |

| BC | 1.133447 | 0.069688 | 0.000000 |

| ABC | 6.566528 | 0.423685 | 0.000000 |

| AB(A-B) | 1.159180 | 0.233490 | 0.000328 |

| AC(A-C) | 1.252320 | 0.234385 | 0.000176 |

| Malonylglycitin | |||

| (A)EtOH | 0.002846 | 0.009474 | 0.768255 |

| (B)H₂O | 0.063592 | 0.010561 | 0.000031 |

| (C)Glycol | 0.036284 | 0.009474 | 0.001839 |

| AB | 0.272083 | 0.052391 | 0.000136 |

| BC | 0.196498 | 0.052391 | 0.002151 |

| ABC | 1.662748 | 0.320204 | 0.000136 |

| Malonylgenistin | |||

| (A)EtOH | 0.017682 | 0.027268 | 0.527991 |

| (B)H₂O | 0.447711 | 0.029917 | 0,000000 |

| (C)Glycol | 0.238918 | 0.026227 | 0.000001 |

| AB | 2.183971 | 0.144919 | 0.000000 |

| BC | 1.629657 | 0.145679 | 0.000000 |

| ABC | 5.432483 | 0.886282 | 0.000036 |

| AB(A-B) | 2.537765 | 0.423631 | 0.000045 |

| Source | SS | MS | F value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daidzin | ||||

| Model | 0.21320 | 0.03045 | 83.34809 | 0.00000 |

| Total error | 0.00438 | 0.00036 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.00180 | 0.00090 | 3.50217 | 0.07034 |

| Pure Error | 0.00257 | 0.00025 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.21758 | 0.01145 | ||

| Model fit R2= 0.9681 Accuracy: Adj. R2=0.9798 | ||||

| Genistin | ||||

| Model | 0.30003 | 0.15088 | 361.6285 | 0.00000 |

| Total error | 0.00985 | 0.00041 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.00780 | 0.00024 | 0.52370 | 0.60276 |

| Pure Error | 0.00205 | 0.00045 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.30988 | 0.05585 | ||

| Model fit; R2=0.9535 Accuracy: Adj. R2=0.9682 | ||||

| Malonyldaidzin | ||||

| Model | 0.05620 | 0.15088 | 361.6285 | 0.00000 |

| Total error | 0.00500 | 0.00041 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.00048 | 0.00024 | 0.52370 | 0.60276 |

| Pure Error | 0.00452 | 0.00045 | ||

| Cor Total | 1.06120 | 0.05585 | ||

| Model fit R2=0.9925 Accuracy:Adj. R2=0.9953 | ||||

| Malonylglycitin | ||||

| Model | 0.040246 | 0.008049 | 33.70776 | 0.000000 |

| Total error | 0.003343 | 0.000239 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.001927 | 0.000482 | 3.40081 | 0.052986 |

| Pure Error | 0.001416 | 0.000142 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.043589 | 0.002294 | ||

| Model fit R2=0.8959 Accuracy:Adj. R2=0.9233 | ||||

| Malonylgenistin | ||||

| Model | 1.57859 | 0.26309 | 144.0319 | 0.00000 |

| Total error | 0.02374 | 0.00182 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.01812 | 0.00604 | 10.7555 | 0.00179 |

| Pure error | 0.00561 | 0.00056 | ||

| Cor Total | 1.60232 | 0.08433 | ||

| Model fit R2=0.9783 Accuracy: Adj. R2= 0.9852 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).