Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

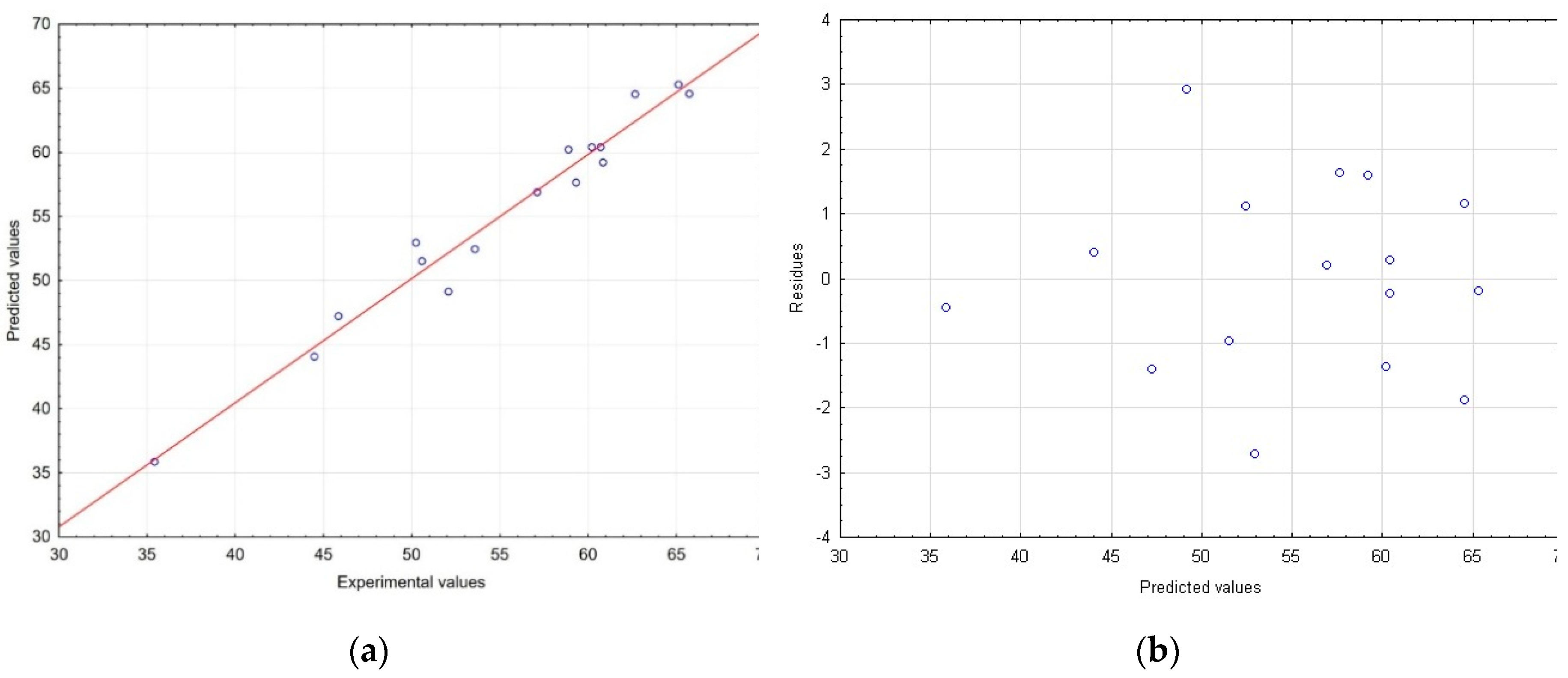

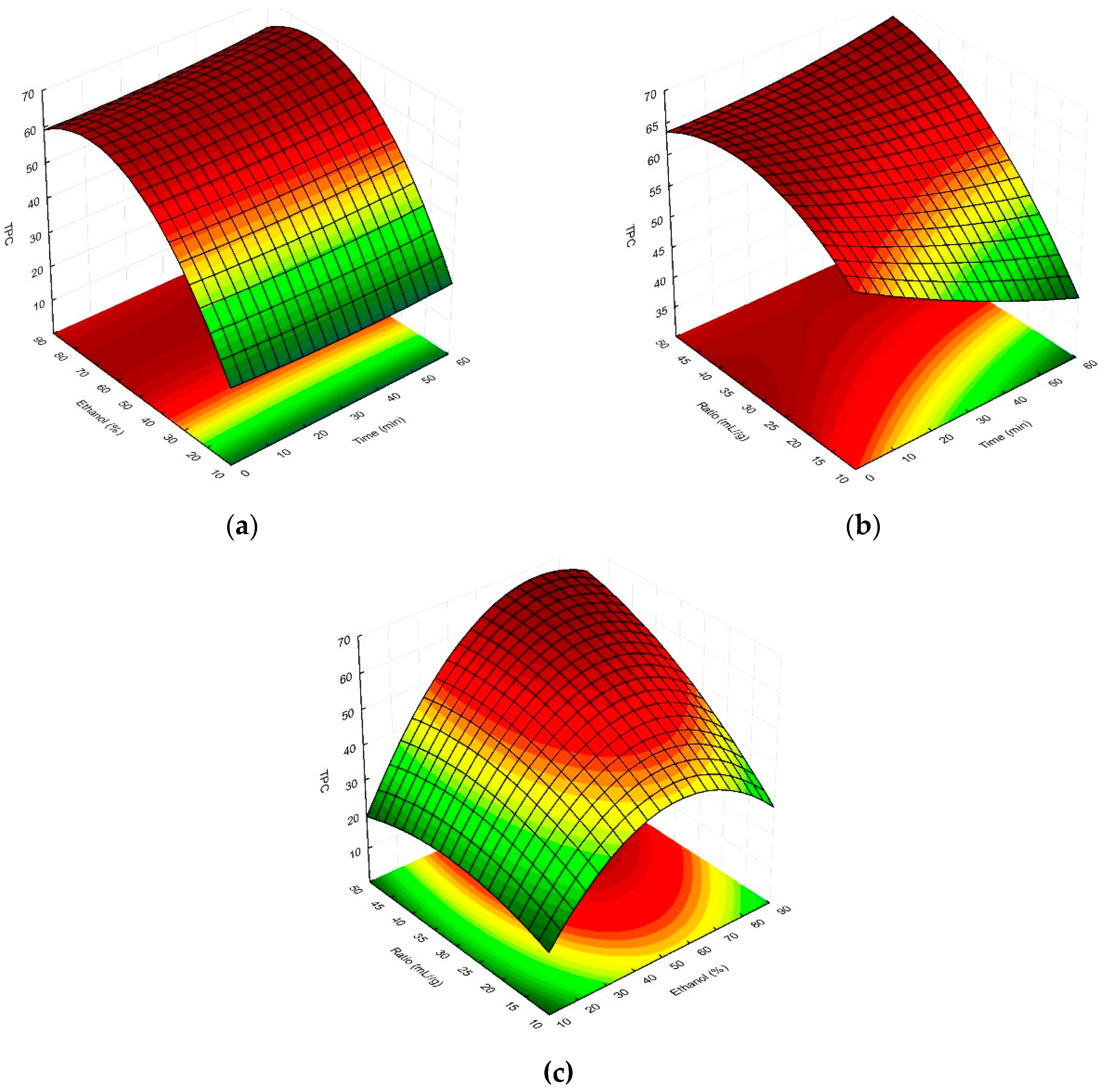

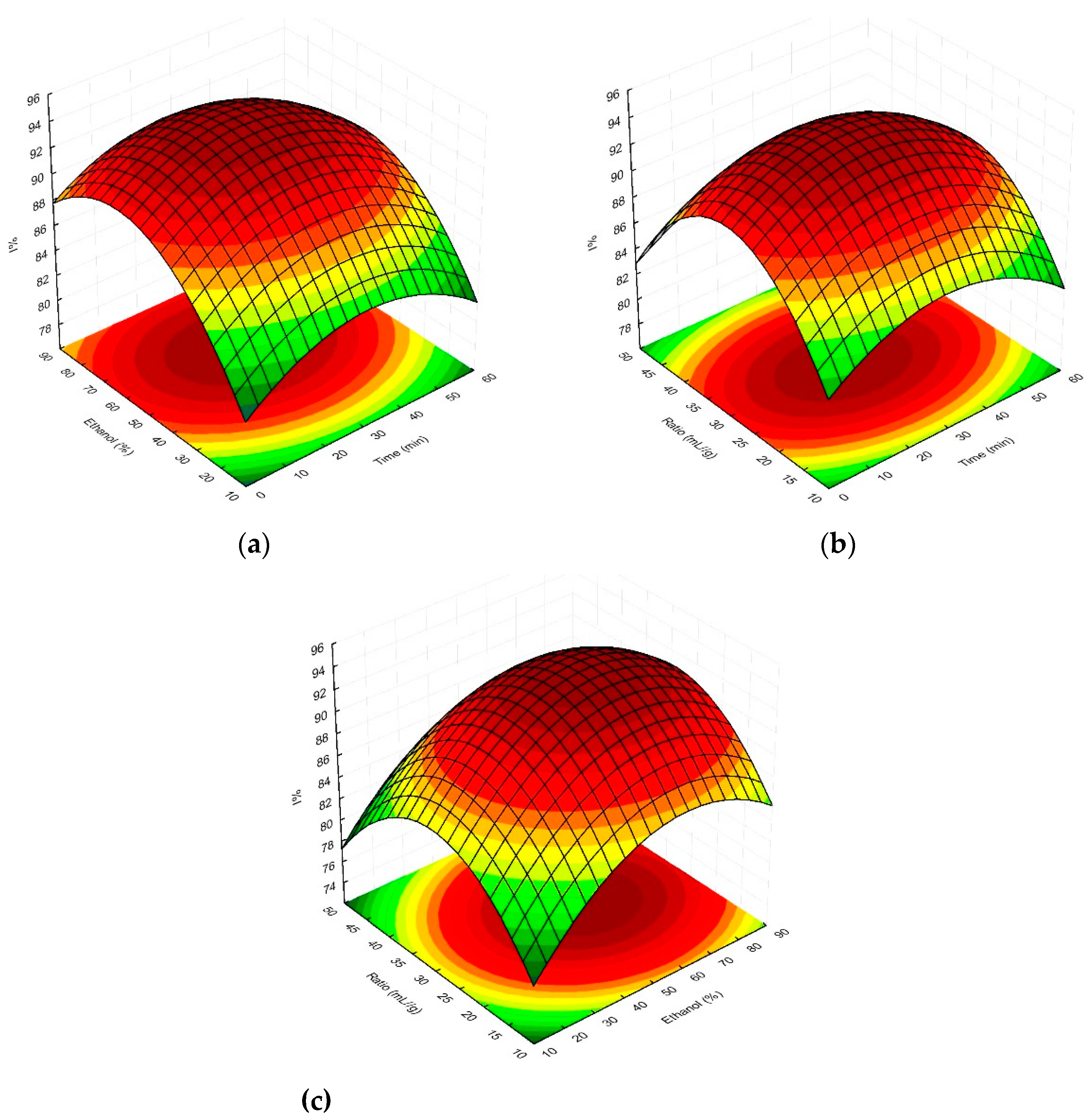

2.1. Multivariate response surface modelling of plant material extraction in relation to total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of magnolia extracts

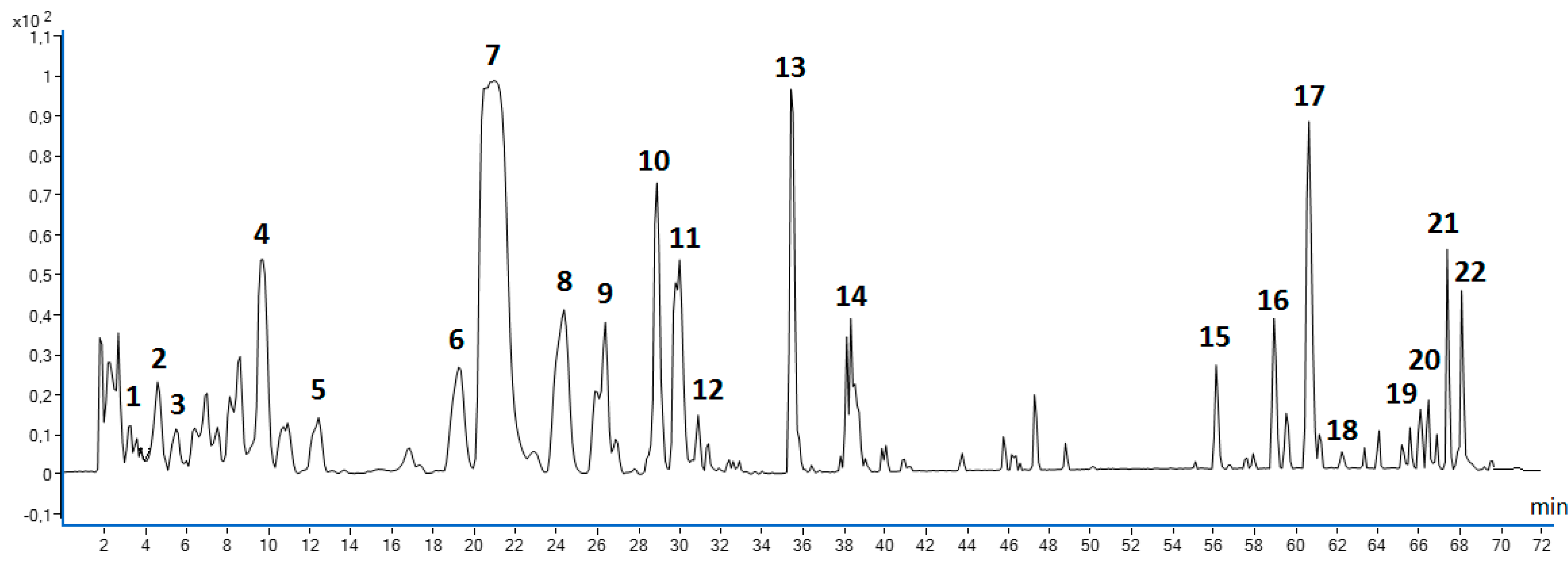

2.2. Phytochemical qualitative profiling of MSL flower bud components using coupled chromatographic, spectroscopic and tandem mass spectrometric techniques

2.1.1. Phenolic acids

2.1.2. Phenylethanoids

2.1.3. Flavonoids

2.1.4. Lignans

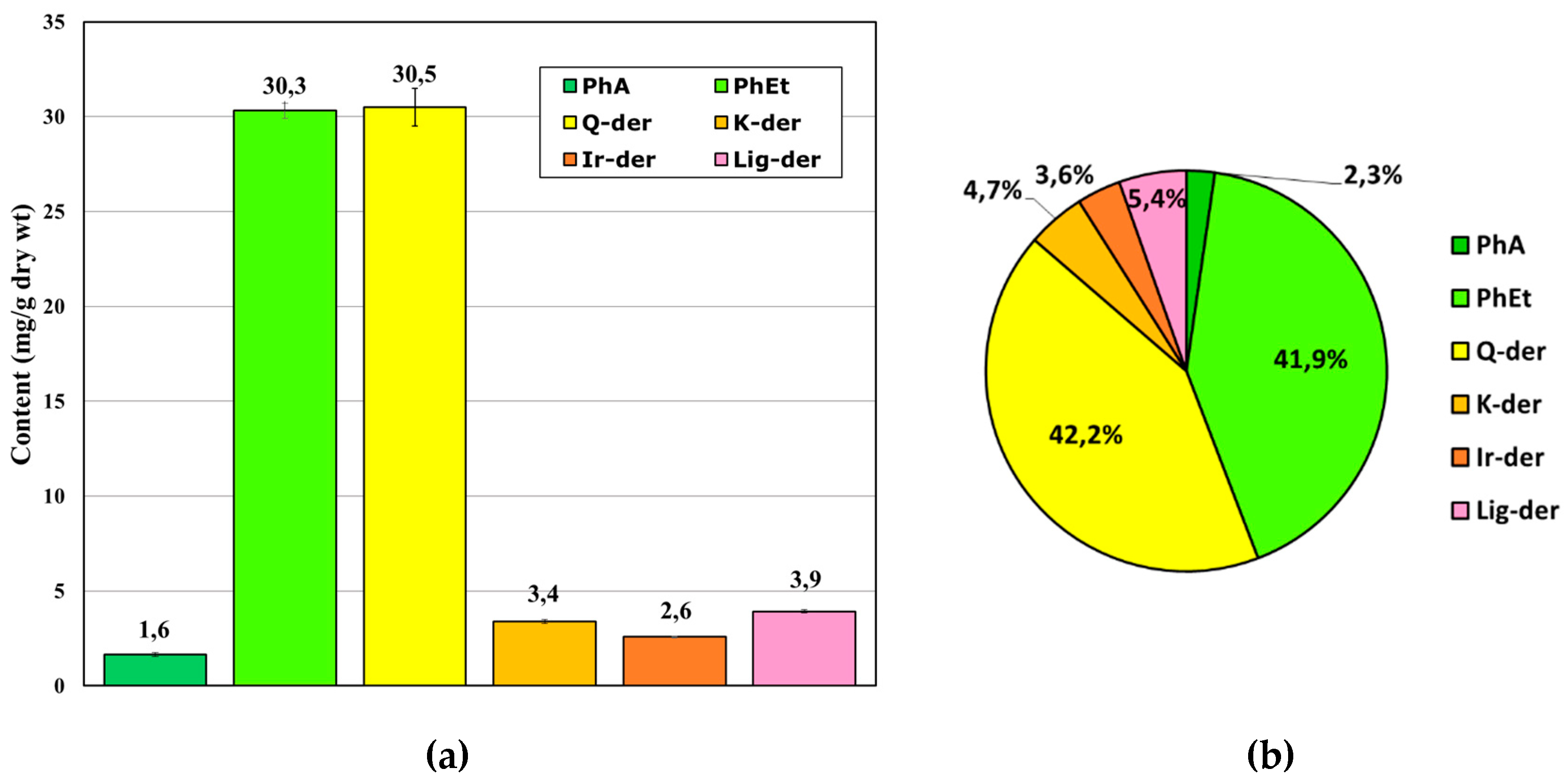

2.3. Phytochemical quantitative profiling of polyphenolic antioxidants in MSL extracts using RP-LC with a photo-diode array (PDA) detection

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant material and its pre-treatment

3.2. Solvents, reagents and certified reference substances

3.3. Central composite design and response surface methodology

| Coded variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Unit | -α | -1 | 0 | 1 | α |

| Time of extraction (X1) | min | 4.77 | 15 | 30 | 45 | 55.23 |

| Ethanol concentration (X2) | % | 16.36 | 30 | 50 | 70 | 83.64 |

| Solvent to plant material ratio (X3) | mL/g | 13.18 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 46.82 |

3.4. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and the preparation of extracts for antioxidant and phytochemical studies

3.5. Total phenolic content assay

3.6. Antioxidant (antiradical) activity assay

3.7. RP-LC/PDA qualitative and quantitative analysis

3.8. Qualitative profiling of MSL phenolics using RP-LC/PDA/ESI-QTOF/MS-MS method

3.9. Statistical modeling

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- WFO (2023): Magnolia L. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000022860 (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Zhang, B.; Yu, H.; Lu, W.; Yu, B.; Liu, L.; Jia, W.; Lin, Z.; Wang H.; Chen, S. Four new honokiol derivatives from the stem bark of Magnolia officinalis and their anticholinesterase activities. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 29, 195–198. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.L.; Huang, Q.; Han, G.Q. A neolignan and lignans from Magnolia biondii. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 287-288. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Haoa, H.; Wanga, G.; Tub, P.; Jiangb, Y.; Lianga, Y.; Daia, L.; Yanga, H.; Laia, L.; Zhenga, C.; Wanga, Q.; Cuia, N.; Liu Y. An approach to identifying sequential metabolites of a typical phenylethanoid glycoside, echinacoside, based on liquid chromatography–ion trap-time of flightmass spectrometry analysis. Talanta 2009, 80, 572–580. [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, G.; Ma, B.; Mo, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Nine phenylethanoid glycosides from Magnolia officinalis var. biloba fruits and their protective effects against free radical-induced oxidative damage. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45342. [CrossRef]

- Soccar, N.M.; Rabeh, M.A.; Ghazal, G.; Slem, A.M. Determination of flavonoids in stamen, gynoecium, and petals of Magnolia grandiflora L. and their associated antioxidant and hepatoprotection activities. Quím. Nova 2014, 37, 667-671. [CrossRef]

- Hyeon, H; Hyun, H.B.; Go, B; Kim, S.C.; Jung Y.H.; Ham, Y.M. Profiles of Essential Oils and Correlations with Phenolic Acids and Primary Metabolites in Flower Buds of Magnolia heptapeta and Magnolia denudata var. purpurascens. Molecules 2021, 27, 221. [CrossRef]

- Dikalov, S.; Losik, T.; Arbiser, J. L. Honokiol is a potent scavenger of superoxide and peroxyl radicals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 76, 589–596. [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, Y.; Nakade, K.; Minoshima, Y.; Yokoyama, R.; Zhai, H.; Mitsumoto, Y. Neurotrophic activity of honokiol on the cultures of fetal rat cortical neurons. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 1163-1166. [CrossRef]

- Hoi, C.P.; Ho, Y.P.; Baum, L.; Chow, A. H. Neuroprotective effect of honokiol and magnolol, compounds from Magnolia officinalis, on beta-amyloid-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1538–1542. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Y; Xue, H.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Fargesin as a potential β₁ adrenergic receptor antagonist protects the hearts against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats via attenuating oxidative stress and apoptosis. Fitoterapia 2015, 105,16-25. [CrossRef]

- Sheu, M. L.; Chiang, C. K.; Tsai, K. S.; Ho, F. M.; Weng, T. I.; Wu, H. Y.; Liu, S. H. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase-related oxidative stress-triggered signaling by honokiol suppresses high glucose-induced human endothelial cell apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 2043–2050. [CrossRef]

- Ham, J.R.; Yun, K.W.; Lee, M.K. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant in Vitro Activities of Magnoliae Flos Ethanol Extract. Prev. Nutr. Food. Sci. 2021, 31, 485-491. [CrossRef]

- Rasul, A; Yu, B; Khan, M; Zhang, K.; Iqbal, F; Ma, T.; Yang, H. Magnolol, a natural compound, induces apoptosis of SGC-7901 human gastric adenocarcinoma cells via the mitochondrial and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 40, 1153-1161. [CrossRef]

- Hahm, E.R.; Arlotti, J.A.; Marynowski, S.W.; Singh, S.V. Honokiol, a constituent of oriental medicinal herb Magnolia officinalis, inhibits growth of PC-3 xenografts in vivo in association with apoptosis induction. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1248−1257. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, K.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Q. Magnolin Inhibits Proliferation and Invasion of Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells by Targeting the ERK1/2 Signaling Pathway. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 421-427. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, B.; Cao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, X. Optimisation of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from wheat bran. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 804-810. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, S.; Liao, M. Optimization of ultrasonic extraction of phenolic compounds from Euryale ferox seed shells using response surface methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 837–843. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. K.; Abert-Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier; A.S.; Dangles, O.; Chemat, F. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols (flavanone glycosides) from orange (Citrus sinensis L.) peel. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 851–858. [CrossRef]

- Pingret, D.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Renard, C.M.; Chemat, F. Lab and pilot-scale ultrasound-assisted water extraction of polyphenols from apple pomace. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 73-81. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, G.; Yue, W.; Liang, Q.; Wu, Q. Optimisation of ultrasound assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from Sparganii rhizoma with response surface methodology. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013, 20, 846–854. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.C.; Bruns, R.E.; Ferreira, H.S.; Matos, G.D.; David, J.M.; Brandão, G.C.; da Silva, E.G.P.; Portugal, L.A.; dos Reis P. S.; Souza, A.S.; dos Santos, W.N.L. Box-Behnken design: an alternative for the optimization of analytical methods. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 597, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G; Zhang, M.; Sun, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, L.; Xue, Z.; He, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, B. Determination of Flavonoids in Magnolia officinalis Leaves Based on Response Surface Optimization of Infrared Assisted Extraction Followed by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). Anal. Lett. 2020, 53, 2145-2159. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, I.D.; Yang X.-M. Process optimization of intermediate-wave infrared drying: Screening by Plackett–Burman; comparison of Box-Behnken and central composite design and evaluation: A case study. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113287. [CrossRef]

- Aleboyeh, A.; Daneshvar, N.; Kasiri, M.B. Optimization of CI Acid Red 14 azo dye removal by electrocoagulation batch process with response surface methodology. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2008, 47, 827–832. [CrossRef]

- Tabaraki, R.; Nateghi, A. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of natural antioxidants from rice bran using response surface methodology. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 1279–1286. [CrossRef]

- Živković, J.; Šavikin, K.; Janković, T.; Ćujić, N.; Menković, N. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenolic compounds from pomegranate peel using response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 194, 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Wijngaard, H.H.; Brunton, N. The optimisation of solid–liquid extraction of antioxidants from apple pomace by response surface methodology. J. Food Eng. 2010, 96, 134–140. [CrossRef]

- Elansary, H.O.; Szopa, A.; Kubica, P.; Al-Mana, F.A.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Ali Zin El-Abedin, T.K.; Mattar, M.A.; Ekiert, H. Phenolic Compounds of Catalpa speciosa, Taxus cuspidata and Magnolia acuminata have Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 412. [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Park, S.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Kim, K-N.; Cho, S-H.; Mariadoss, A.V.A., Wang M.-H. Metabolite Profiling of Methanolic Extract of Gardenia jaminoides by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS and Its Anti-Diabetic, and Anti-Oxidant Activities. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 102. [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Park, S.U. Analysis of Metabolites in White Flowers of Magnolia denudata Desr. and Violet Flowers of Magnolia liliflora Desr. Molecules 2018, 23, 1558. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.O.; Curto, A.F.; Guido, L.F. Determination of Phenolic Content in Different Barley Varieties and Corresponding Malts by Liquid Chromatography-diode Array Detection-Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 563-576. [CrossRef]

- Porter, E.A.; Kite, G.C.; Veitch, N.C.; Geoghegan, I.A.; Larsson, S.; Simmonds, M.S. Phenylethanoid glycosides in tepals of Magnolia salicifolia and their occurrence in flowers of Magnoliaceae. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 185-193. [CrossRef]

- Kite, G.C. Characterization of phenylethanoid glycosides by multiple-stage mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2020, 34, Suppl 4:e8563. [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.H.; Nam, M.H.; Chung, N.; Lee, Y.K. UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS screening and identification of bioactive compounds in fresh; aged; and browned Magnolia denudata flower extracts. Food Research International 2022, 133, 109192. [CrossRef]

- Sokkar, N.M.; Rabeh, M.A.; Ghazal, G.; Slem, A.M. Determination of flavonoids in stamen; gynoecium and petals of Magnolia grandiflora L. and their associated antioxidant and hepatoprotection activities. Quim. Nova 2014, 37, 667-671. [CrossRef]

- Srinroch, C.; Sahakitpichan, P.; Chimnoi, N.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kanchanapoom, T. Neolignan and monoterpene glycosides from Magnolia henryi. Phytocem. Lett. 2019, 29, 94-97. [CrossRef]

- Abad-García, B.; Berruetay, L.A.; Garmón-Lobato, S.; Gallo, B.; Vicente, F. A general analytical strategy for the characterization of phenolic compounds in fruit juices by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection coupled to electrospray ionization and triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2009, 1216, 5398-415. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fu, X.; Li, X.; Tang, D. Effect of Flavonoid Dynamic Changes on Flower Coloration of Tulipa gesneiana 'Queen of Night' during Flower Development. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 510. [CrossRef]

- Hawas, U.W.; Abou El-Kassem, L.T.; Shaher, F.; Al-Farawati, R. In vitro inhibition of Hepatitis C virus protease and anti-oxidant by flavonoid glycosides from the Saudi costal plant Sarcocornia fruticosa. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 3364-3371. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, Z.; Duan, W.; Fang, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, X. Isolation and purification of seven lignans from Magnolia sprengeri by high-speed counter-current chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2011, 879, 3775-3779. [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.S., Lee, J.I., Kim J.A., Seo Y. In vitro evaluation on the antiobesity effect of lignans from the flower buds of Magnolia denudata. J Agric Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5665-5670. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.L.; Huang, Q.; Han, G.Q. A neolignan and lignans from Magnolia biondii. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 287-288. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.B.; Liu, T.T.; Zhang, Z.X.; Wang, W.S.; Zhu, W.W.; Li, L.F.; Li, Y.R.; Chen, X. Leaves of Magnolia liliflora Desr. as a high-potential by-product: Lignans composition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-phytopathogenic fungal and phytotoxic activities, Industr. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 416-424. [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; A Phytochemical Study of Members of the Genus Magnolia (Magnoliaceae) and Biosynthetic Studies of Secondary Metabolites in Asteraceae Hairy Root Cultures, LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses 1995, 5930, 5-10. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5930.

- Zgórka, G. Ultrasound-assisted solid-phase extraction coupled with photodiode-array and fluorescence detection for chemotaxonomy of isoflavone phytoestrogens in Trifolium L. (Clover) species. J. Sep. Sci. 2009, 32, 965-972. [CrossRef]

- Zgórka, G.; Maciejewska-Turska, M.; Makuch-Kocka, A.; Plech, T. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity and Chemopreventive Potential in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines of the Standardized Extract Obtained from the Aerial Parts of Zigzag Clover (Trifolium medium L.). Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 699. [CrossRef]

- Benabdallah, A.; Rahmoune, C.; Boumendjel, M.; Aissi, O.; Messaoud, C. Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of six wild Mentha species (Lamiaceae) from northeast of Algeria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 6, 760–766. [CrossRef]

| Run | Coded levels | TPC (mg GAE/g dry wt) |

%I |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | Exp.* | Predict. | Exp.* | Predict. | |

| Factorial points | |||||||

| 1 | -1(15) | -1(30) | -1(20) | 50.58 | 51.55 | 88.25 | 88.01 |

| 2 | -1(15) | -1(30) | 1(40) | 52.08 | 49.17 | 88.63 | 87.99 |

| 3 | -1(15) | 1(70) | -1(20) | 60.84 | 59.24 | 91.47 | 91.15 |

| 4 | -1(15) | 1(70) | 1(40) | 65.10 | 65.31 | 91.25 | 90.90 |

| 5 | 1(45) | -1(30) | -1(20) | 44.48 | 44.09 | 88.38 | 88.12 |

| 6 | 1(45) | -1(30) | 1(40) | 45.84 | 47.25 | 88.06 | 87.77 |

| 7 | 1(45) | 1(70) | -1(20) | 50.24 | 52.97 | 90.64 | 90.67 |

| 8 | 1(45) | 1(70) | 1(40) | 65.73 | 64.58 | 90.47 | 90.10 |

| Axial points | |||||||

| 9 | - α (4.77) | 0(50) | 0(30) | 62.66 | 64.55 | 90.64 | 91.27 |

| 10 | α (55.23) | 0(50) | 0(30) | 59.30 | 57.67 | 90.46 | 90.69 |

| 11 | 0(30) | - α (16.36) | 0(30) | 35.42 | 35.88 | 86.76 | 87.31 |

| 12 | 0(30) | α (83.64) | 0(30) | 57.11 | 56.91 | 91.59 | 91.90 |

| 13 | 0(30) | 0(50) | - α (13.18) | 53.58 | 52.48 | 88.26 | 88.43 |

| 14 | 0(30) | 0(50) | α (46.82) | 58.87 | 60.24 | 87.24 | 87.93 |

| Central points | |||||||

| 15 (C) | 0(30) | 0(50) | 0(30) | 60.70 | 60.43 | 93.27 | 93.71 |

| 16 (C) | 0(30) | 0(50) | 0(30) | 60.20 | 60.43 | 94.29 | 93.71 |

| Coefficient | TPC model | %I model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | S.E. | R2 | S.E. | |

|

Intercept β0 |

24.60 | 2.10 | 58.95a | 4.29 |

|

Linear β1 |

-0.53 |

0.05 |

0.29 |

0.09 |

| β2 | 1.21 a | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.08 |

| β3 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 1.19 | 0.17 |

|

Quadratic β11 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

| β22 | -0.01 a | 0.00 | -0.00 | 0.00 |

| β33 | -0.01 | 0.00 | -0.02 | 0.00 |

|

Interaction β12 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

| β13 | 0.01 | 0.00 | -0.00 | 0.00 |

| β23 | 0.01 a | 0.00 | -0.00 | 0.00 |

| Independent variables | SS | df | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | ||||

| Linear | ||||

| X1 | 57.25 | 1 | 457.97 | 0.0297a |

| X2 | 534.13 | 1 | 4273.04 | 0.0097b |

| X3 | 72.69 | 1 | 581.49 | 0.0264a |

| Quadratic | ||||

| X12 | 0.54 | 1 | 4.33 | 0.2853 |

| X22 | 228.00 | 1 | 1823.98 | 0.0149a |

| X32 | 19.20 | 1 | 153.58 | 0.0513 |

| Interaction | ||||

| X1X2 | 0.70 | 1 | 5.62 | 0.2542 |

| X1X3 | 15.37 | 1 | 122.99 | 0.0573 |

| X2X3 | 35.66 | 1 | 285.27 | 0.0376a |

| Lack of fit | 32.52 | 5 | 52.03 | 0.1048 |

| Pure error | 0.13 | 1 | ||

| Total SS | 1037.60 | 15 | ||

| R2 | 0.9685 | |||

| R2adj. | 0.9213 | |||

| %I | ||||

| X1 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.5396 |

| X2 | 25.42 | 1 | 48.87 | 0.0905 |

| X3 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.59 | 0.5833 |

| X12 | 8.60 | 1 | 16.54 | 0.1535 |

| X22 | 19.47 | 1 | 37.43 | 0.1031 |

| X32 | 35.36 | 1 | 67.96 | 0.0768 |

| X1X2 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.6685 |

| X1X3 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.8036 |

| X2X3 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.8618 |

| Lack of fit | 2.35 | 5 | 0.90 | 0.6592 |

| Pure error | 0.52 | 1 | ||

| Total SS | 69.06 | 15 | ||

| R2 | 0.9585 | |||

| R2adj. | 0.8961 | |||

| No. | Compound |

Rt (min) |

λmax (nm) |

Formula | Precursor ion (m/z) |

Product ions (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protocatechuic acid R | 3.67 | 206, 260, 294 | C₇H₆O₄ | 153.0193 | 110.0331, 109.0297, 108.0219 |

| 2 | Chlorogenic acid | 4.58 | 218, 326 | C16H18O9 | 353.0855 R | 191.0543, 173.0437 |

| 3 | Echinacoside R | 5.08 | 198, 330 | C35H46O20 | 785.2466 | 623,2127, 477.1619, 315,0898, 179,0338, 161.0233 |

| 4 | 2’- Rhamno- echinacoside |

9.91 | 198, 330 | C16H16O8 | 931.3058 | 769.2726, 751.2572, 179.0499, 161.0238 |

| 5 | Vanillic acid R | 12.41 | 218, 260, 292 | C8H8O4 | 167.0351 | 135.0116, 109.0250, 108.0210 |

| 6 | Quercetin 3-O-neohesperidoside | 19.34 | 204, 266, 350 | C27H30O16 | 609,1303 | 300.0277, 271.0268, 151.0039 |

| 7 | Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (Rutoside) R | 20.95 | 204, 256, 355 | C27H30O16 | 609.1443 | 301.0405, 300.0334, 271.0253, 257.0411, 229.0108 |

| 8 | Quercetin 3-O-glucoside (Isoquercitrin) R |

24.37 | 204, 256, 355 | C21H20O12 | 463.0889 | 301.0347, 271.0229, 178.9999 |

| 9 | Acteoside (Verbascoside)R |

26.48 | 198, 330 | C29H36O15 | 623.1985 | 461.1665, 179.0342, 161.0246 |

| 10 | Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside (Nicotiflorin)R | 28.89 | 196, 266, 346 | C27H30O15 | 593.1571 | 345.0664, 285.0444 |

| 11 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (Narcissin) | 29.69 | 204, 254, 354 | C28H32O16 | 623.1584 | 315.0516, 314.0441, 300.0296, 271.0252, 255.0216, 161.0243 |

| 12 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside R | 30.80 | 204, 254, 354 | C22H22O12 | 477.1042 | 315.0486, 314.0429, 271.0256 |

| 13 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside isomer |

35.52 | 205, 255, 354 | C28H32O16 | 623.1611 | 315.0505, 314.0437 |

| 14 | Rhamnazin 3-O-rutinoside (Ombuoside) |

38.44 | 206, 256, 356 | C29H34O16 | 637.1728 | 330.0684, 329.0653, 315.0509, 288.0168, 161.0239 |

| 15 | Magnolin R | 56.22 | 204, 230, 278 | C23H28O7 | 415.4612 | 236.1059, 222.1580, 221.1545, 220.1469 |

| 16 | Lignan (fargesin type) | 58.93 | 202, 236, 260 | n.d. | 595.2865 | 279.2333, 174.9563, 112.9860 |

| 17 | Lignan (fargesin type) | 60.54 | 202, 234, 286 | n.d. | 571.2938 | 309.2091, 174.9570, 112.9856 |

| 18 | Fargesin R | 62.25 | 202, 234, 284 | C21H22O6 | 369.1328 | 357.1360, 242.9433, 174.9563, 112.9856 |

| 19 | Lignan (fargesin type) | 66.47 | 204, 234, 280 | n.d. | 293.2140 | 223.1358,195.1402, 174.9570, 112.9856 |

| 20 | Lignan (fargesin type) | 66.87 | 204, 236, 286 | n.d. | 625.3393 | 341.1096, 255.2333, 174.9561, 112.9856 |

| 21 | Lignan (fargesin type) | 67.37 | 202, 234, 286 | n.d. | 317.1745 | 274.1890, 174.9560, 112.9856 |

| 22 | Lignan (fargesin type) | 68.08 | 202, 234, 284 | n.d. | 295.2280 | 277.2182, 174.9564, 112.9856 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).