Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

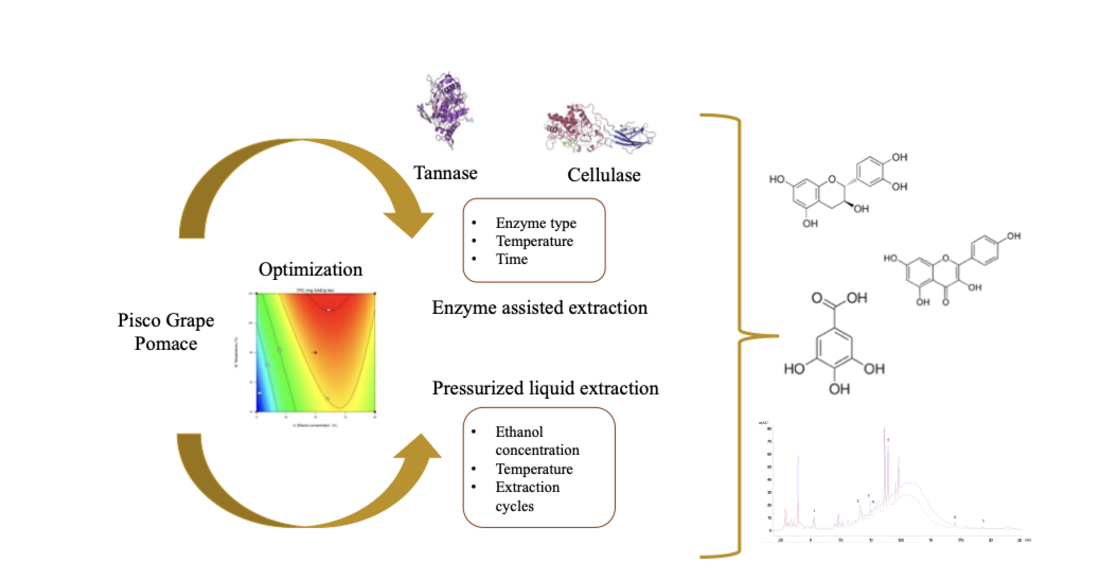

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Preparation of the Raw Material

2.4. Characterization of the Dried Pomace

2.5. Conventional Extraction by Agitation (EA)

2.6. Experimental Design of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE)

2.7. Enzyme Assisted Extraction (EAE)

2.8. Experimental Design of Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE)

2.9. Pressurized Liquid Extraction

2.10. Characterization of Optimal EAE and PLE Extracts

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Dried Pomace

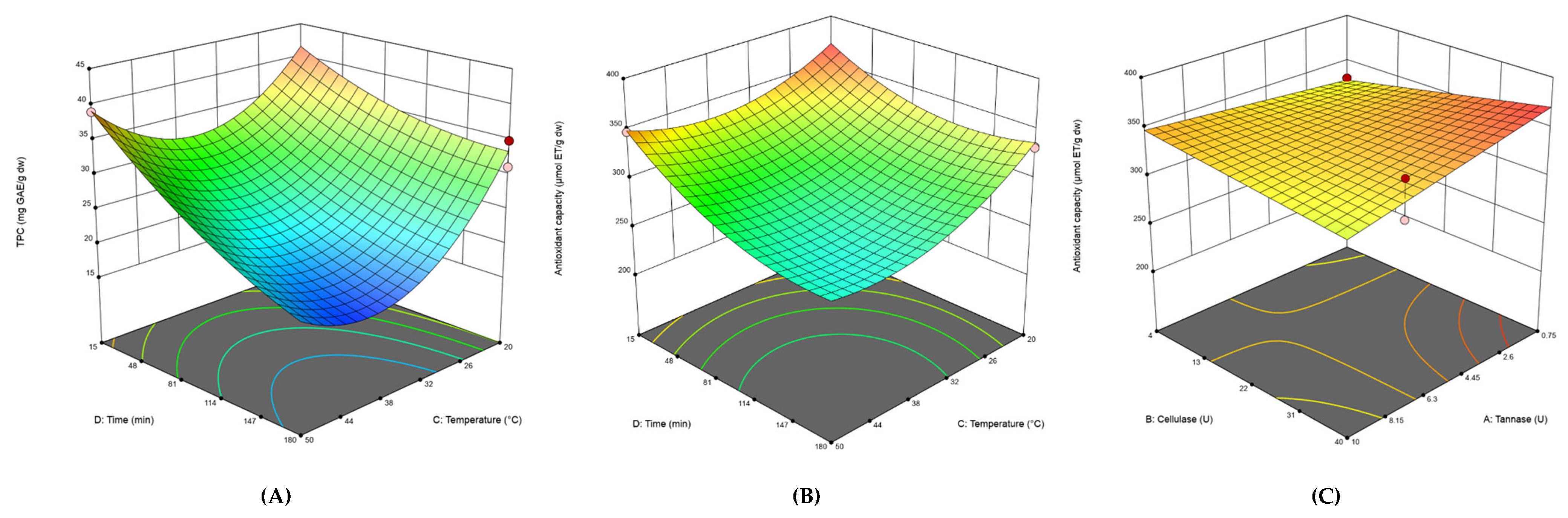

3.2. Experimental Design of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction

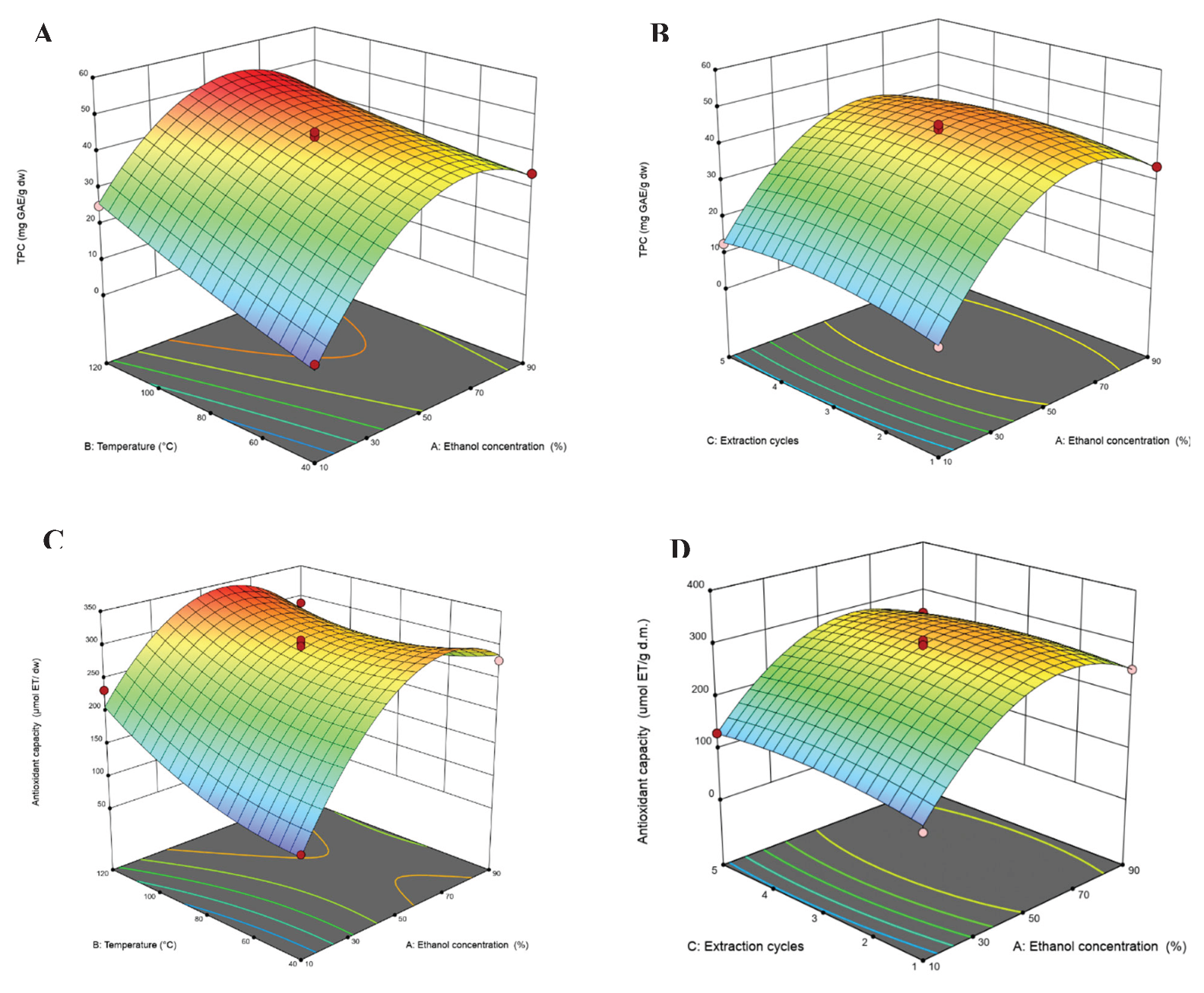

3.3. Experimental Design of Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE)

3.4. Validation of Enzymatic and Pressurized Liquid Extractions

3.5. Characterization of Optimal Extracts

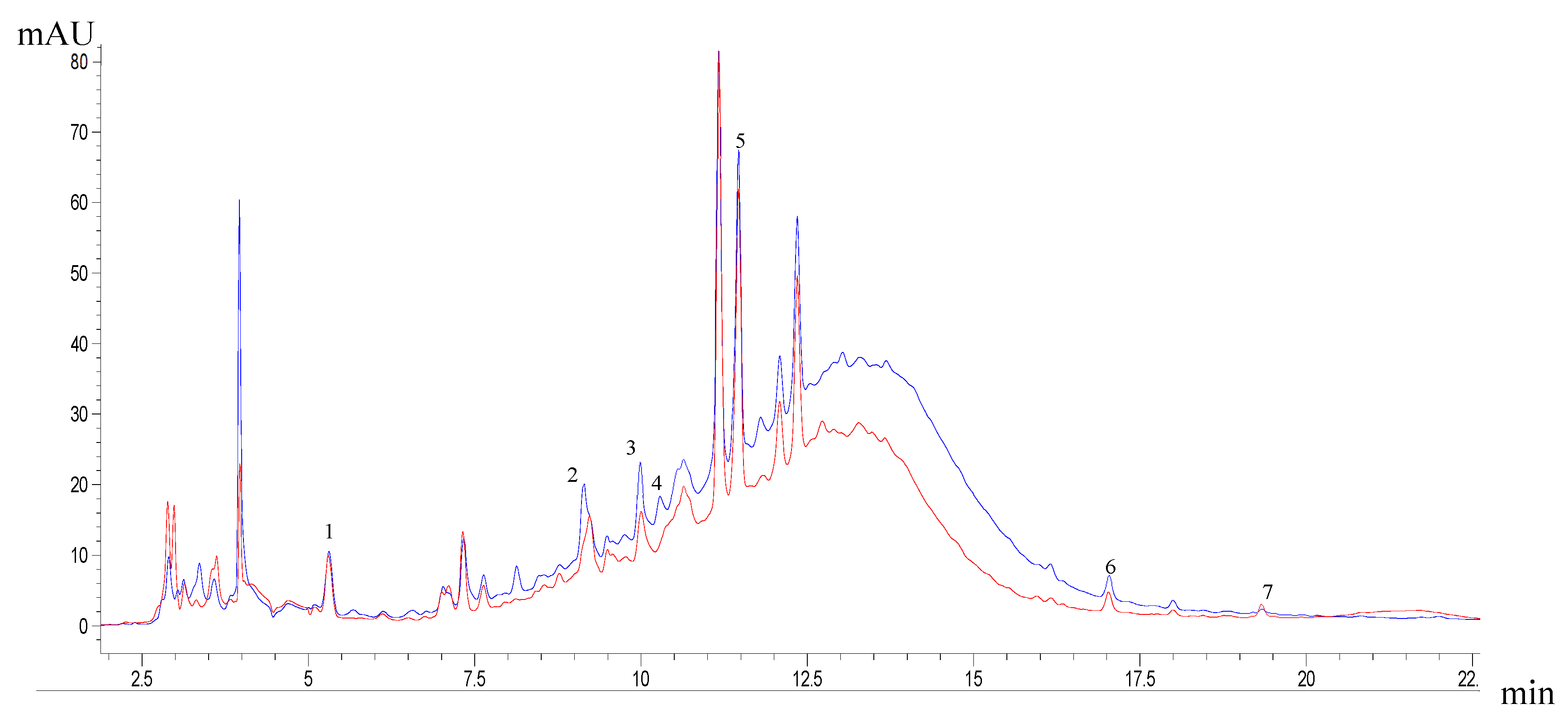

3.6. Phenol Profile of Optimum Extracts

| Parameters | VAC 60 °C | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1Moisture | 5.51 | ± | 0.26 |

| 2Fat | 7.35 | ± | 0.24 |

| 2Ash | 5.83 | ± | 0.09 |

| 2Crude protein | 12.74 | ± | 0.54 |

| 2Insoluble dietary fiber, IDF | 38.08 | ± | 4.04 |

| 2Soluble dietary fiber, SDF | 2.86 | ± | 0.18 |

| 2Total dietary fiber, TDF | 40.94 | ± | 3.86 |

| 3Total Carbohydrates | 74.07 | ± | 0.48 |

| 4Reducing sugar content | 33.65 | ± | 1.09 |

| 5Water activity, aw | 0.3069 | ± | 0.0066 |

| Variables | Response | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Y1 | Y2 | |

| Run |

Tannase (U) |

Cellulase (U) |

Temperature (°C) |

Time (min) |

TPC (mg GAE g-1 dw) |

Antioxidant capacity (μmol TE g-1 dw) |

| 1 | 3.99 | 4 | 50 | 15 | 35.61 | 327.04 |

| 2 | 0.75 | 40 | 20 | 180 | 31.17 | 332.94 |

| 3 | 0.75 | 4 | 20 | 15 | 38.96 | 300.68 |

| 4 | 10 | 4 | 20 | 88.43 | 33.8 | 329.88 |

| 5 | 10 | 4 | 50 | 180 | 19.47 | 260.06 |

| 6 | 5.38 | 22 | 35 | 97.5 | 20.28 | 253.04 |

| 7 | 3.99 | 4 | 20 | 180 | 31.68 | 320.17 |

| 8 | 10 | 40 | 33.05 | 180 | 23.23 | 252.69 |

| 9 | 10 | 40 | 50 | 88.43 | 30.21 | 258.26 |

| 10 | 10 | 24.16 | 20 | 180 | 30.11 | 289.96 |

| 11 | 7.60 | 40 | 20 | 15 | 40.09 | 320.78 |

| 12 | 0.75 | 40 | 20 | 180 | 34.92 | 331.81 |

| 13 | 0.75 | 4 | 20 | 15 | 39.79 | 331.40 |

| 14 | 1.49 | 40 | 28.64 | 15 | 44.78 | 369.49 |

| 15 | 10 | 24.52 | 50 | 15 | 38.15 | 299.94 |

| 16 | 3.96 | 40 | 50 | 180 | 16.19 | 238.86 |

| 17 | 10 | 4 | 32.75 | 15 | 31.15 | 304.45 |

| 18 | 10 | 4 | 50 | 180 | 19.98 | 239.59 |

| 19 | 0.75 | 4 | 33.5 | 105.75 | 19.57 | 247.00 |

| 20 | 0.75 | 4 | 50 | 180 | 18.17 | 243.97 |

| 21 | 0.75 | 23.98 | 36.65 | 180 | 30.07 | 259.49 |

| 22 | 7.60 | 40 | 20 | 15 | 42.42 | 359.75 |

| 23 | 5.38 | 22 | 35 | 97.5 | 19.18 | 226.34 |

| 24 | 0.75 | 40 | 50 | 15 | 38.97 | 347.46 |

| 25 | 3.99 | 4 | 20 | 180 | 31.53 | 295.15 |

| 26 | 0.75 | 23.44 | 20 | 90.9 | 35.50 | 318.41 |

| 27 | 0.75 | 20.15 | 49.50 | 88.94 | 30.21 | 268.40 |

| Response | Y1:TPC | Y2: Antioxidant capacity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | ||

| Model | 1537.99 | 8 | 192.25 | 53.48 | < 0.0001 | 38917.57 | 8 | 4864.7 | 15 | < 0.0001 | ||

| X1-Tannase | 2.49 | 1 | 2.49 | 0.6939 | 0.4171 | 786.84 | 1 | 786.84 | 2.43 | 0.1367 | ||

| X2-Cellulase | 16.05 | 1 | 16.05 | 4.46 | 0.0507 | 479.19 | 1 | 479.19 | 1.48 | 0.2398 | ||

| X3-Temperature | 283.34 | 1 | 283.34 | 78.81 | < 0.0001 | 9094.98 | 1 | 9094.98 | 28.05 | < 0.0001 | ||

| X4-Time | 785.68 | 1 | 785.68 | 218.54 | < 0.0001 | 14415.47 | 1 | 14415.47 | 44.46 | < 0.0001 | ||

| X1X2 | - | - | - | - | - | 3326.98 | 1 | 3326.98 | 10.26 | 0.0049 | ||

| X3X4 | 107.12 | 1 | 107.12 | 29.8 | < 0.0001 | 1760.49 | 1 | 1760.49 | 5.43 | 0.0316 | ||

| X1² | 17.05 | 1 | 17.05 | 4.74 | 0.0447 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| X3² | 228.65 | 1 | 228.65 | 63.6 | < 0.0001 | 2981.37 | 1 | 2981.37 | 9.19 | 0.0072 | ||

| X4² | 18.19 | 1 | 18.19 | 5.06 | 0.0389 | 2259.98 | 1 | 2259.98 | 6.97 | 0.0166 | ||

| Residual | 57.52 | 16 | 3.6 | 5836.62 | 18 | 324.26 | ||||||

| Lack of Fit | 46.68 | 10 | 4.67 | 2.58 | 0.1287 | 3725.84 | 12 | 310.49 | 0.8826 | 0.5997 | ||

| Pure Error | 10.84 | 6 | 1.81 | 2110.78 | 6 | 351.8 | ||||||

| Cor Total | 1595.51 | 24 | 44754.19 | 26 | ||||||||

| Fit Statistics | ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.9639 | 0.8698 | ||||||||||

| R2 Adjusted | 0.9456 | 0.8116 | ||||||||||

| R2 Predicted | 0.9085 | 0.7067 | ||||||||||

| CV (%) | 6.32 | 6.13 | ||||||||||

| Variables | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | Y1 | Y2 | |

| Run |

Ethanol concentration (%) | Temperature (°C) | Extraction cycles | TPC (mg GAE g-1 dw) |

Antioxidant capacity (μmol TE g-1 dw) |

| 1 | 90 | 120 | 3 | 40.05 | 289.10 |

| 2 | 90 | 80 | 1 | 34.07 | 253.40 |

| 3 | 50 | 80 | 3 | 41.85 | 304.27 |

| 4 | 50 | 40 | 1 | 31.53 | 277.81 |

| 5 | 50 | 80 | 3 | 44.18 | 301.35 |

| 6 | 50 | 80 | 3 | 39.90 | 308.08 |

| 7 | 90 | 40 | 3 | 34.19 | 277.74 |

| 8 | 90 | 80 | 5 | 33.54 | 253.94 |

| 9 | 10 | 80 | 5 | 12.70 | 130.90 |

| 10 | 50 | 40 | 5 | 33.38 | 310.86 |

| 11 | 10 | 40 | 3 | 5.84 | 102.22 |

| 12 | 10 | 80 | 1 | 8.72 | 98.33 |

| 13 | 50 | 120 | 5 | 50.21 | 295.86 |

| 14 | 50 | 80 | 3 | 45.49 | 298.83 |

| 15 | 50 | 120 | 1 | 48.64 | 347.14 |

| 16 | 50 | 80 | 3 | 44.94 | 281.54 |

| 17 | 10 | 120 | 3 | 25.25 | 233.23 |

| Response | Y1:TPC | Y2: Antioxidant capacity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | ||

| Model | 2901.32 | 9 | 322.37 | 69.5 | < 0.0001 | 87221.11 | 9 | 9691.23 | 34.06 | < 0.0001 | ||

| X1-Ethanol concentration | 997.7 | 1 | 997.7 | 215.09 | < 0.0001 | 32448.78 | 1 | 32448.78 | 114.05 | < 0.0001 | ||

| X2-Temperature | 438.23 | 1 | 438.23 | 94.47 | < 0.0001 | 4836.36 | 1 | 4836.36 | 17 | 0.0044 | ||

| X3-Extraction cycles | 5.9 | 1 | 5.9 | 1.27 | 0.2966 | 27.68 | 1 | 27.68 | 0.0973 | 0.7642 | ||

| X1X2 | 45.9 | 1 | 45.9 | 9.9 | 0.0162 | 3579.03 | 1 | 3579.03 | 12.58 | 0.0094 | ||

| X1X3 | 5.09 | 1 | 5.09 | 1.1 | 0.3299 | 256.48 | 1 | 256.48 | 0.9014 | 0.374 | ||

| X2X3 | 0.0196 | 1 | 0.0196 | 0.0042 | 0.95 | 1777.89 | 1 | 1777.89 | 6.25 | 0.041 | ||

| X1² | 1335.71 | 1 | 1335.71 | 287.96 | < 0.0001 | 40858.42 | 1 | 40858.42 | 143.6 | < 0.0001 | ||

| X2² | 3.2 | 1 | 3.2 | 0.6894 | 0.4338 | 2688.04 | 1 | 2688.04 | 9.45 | 0.018 | ||

| X3² | 43.21 | 1 | 43.21 | 9.32 | 0.0185 | 1100 | 1 | 1100 | 3.87 | 0.09 | ||

| Residual | 32.47 | 7 | 4.64 | 1991.65 | 7 | 284.52 | ||||||

| Lack of Fit | 10.55 | 3 | 3.52 | 0.6419 | 0.6272 | 1571.2 | 3 | 523.73 | 4.98 | 0.0774 | ||

| Pure Error | 21.92 | 4 | 5.48 | 420.45 | 4 | 105.11 | ||||||

| Cor Total | 2933.79 | 16 | 89212.76 | 16 | ||||||||

| Fit Statistics | ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.9889 | 0.9777 | ||||||||||

| R2 Adjusted | 0.9747 | 0.9490 | ||||||||||

| R2 Predicted | 0.9308 | 0.7180 | ||||||||||

| CV (%) | 6.37 | 8.82 | ||||||||||

| TPC (mg GAE g-1 dw) |

Antioxidant capacity (μmol ET g-1 dw) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction | Optimal conditions | Value Predicted | Value Experimental | Error percentage (%) * | Value Predicted | Value Experimental | Error percentage (%) * |

|

| EAE | Tannase (U) | 0.75 | 41.51 | 38.49 | 7.34 | 370.52 | 342.47 | 7.57 |

| cellulase (U) | 40 | |||||||

| Time (min) | 15 | |||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 20 | |||||||

| PLE | Ethanol concentration (%) | 54 | ||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 113 | 50.66 | 50.03 | 1.24 | 331.84 | 371.00 | 11.80 | |

| Extraction cycles | 3 | |||||||

| Extraction methods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | EAE | PLE | |||||

| TPC (mg GAE g-1 dw)* | 38.49 | ± | 0.99b | 50.03 | ± | 0.58ª | |

| TFC (mg QE g-1 dw) | 51.78 | ± | 1.62b | 75.48 | ± | 2.12ª | |

| DPPH (μmol TE g-1 dw)* | 342..47 | ± | 1.29b | 371.00 | ± | 8.89ª | |

| ORAC (μmol TE g-1 dw) | 1687.47 | ± | 4.66b | 1931.39 | ± | 90.26ª | |

| Sugars (mg Glucose g-1 dw) | 262.58 | ± | 1.83b | 266.79 | ± | 0.02a | |

| Phenolic compounds (mg g-1 dw) | |||||||

| Gallic acid | 0.14 | ± | 0.01b | 0.23 | ± | 0.01ª | |

| Catechin | 0.37 | ± | 0.02b | 0.69 | ± | 0.00a | |

| Epicatechin | 0.40 | ± | 0.01b | 0.61 | ± | 0.02ª | |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic | NQ | 0.19 | ± | 0.00a | |||

| Rutin | 2.31 | ± | 0.06b | 2.88 | ± | 0.03ª | |

| Quercetin | 0.09 | ± | 0.00b | 0.12 | ± | 0.02ª | |

| Kaempferol | 0.05 | ± | 0.00b | 0.04 | ± | 0.00a | |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coelho, M.C.; Pereira, R.N.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M.E. The Use of Emergent Technologies to Extract Added Value Compounds from Grape By-Products. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020, 106, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, Z.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; González-de-Peredo, A. V.; Palma, M.; de Andrés, M.T. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Non-Coloured Phenolic Compounds from Grape Cultivars. European Food Research and Technology 2022, 248, 1883–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Vergara, M.; Alvarez-Marin, A.; Carvajal-Cortes, S.; Salinas-Flores, S. Implementation of a Cleaner Production Agreement and Impact Analysis in the Grape Brandy (Pisco) Industry in Chile. J Clean Prod 2015, 96, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, A.; Scioli, G.; Valle, A. Della; Cichelli, A.; Novellino, E.; Bauer, M.; Kamysz, W.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Córdova, M.L.F. De; Castillo-López, R.; et al. Phenolic Analysis and in Vitro Biological Activity of Red Wine, Pomace and Grape Seeds Oil Derived from Vitis Vinifera l. Cv. Montepulciano d’abruzzo. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Solari-Godiño, A.; Lindo-Rojas, I.; Pandia-Estrada, S. Determination of Phenolic Compounds and Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity of Two Grapes Residues (Vitis Vinifera) of Varieties Dried: Quebranta (Red) and Torontel (White). Cogent Food Agric 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcca-Alca, E.E.; León-Calvo, N.C.; Luque-Vilca, O.M.; Martínez-Cifuentes, M.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S.; Huamán-Castilla, N.L. Hot Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Polyphenols from the Skin and Seeds of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Negra Criolla Pomace a Peruvian Native Pisco Industry Waste. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, S.; Viveros, A.; Alvarez, I.; Vega, E.; Brenes, A. Changes in Polyphenol and Polysaccharide Content of Grape Seed Extract and Grape Pomace after Enzymatic Treatment. Food Chem 2012, 133, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, K.; Vega, M.; Aspé, E. An Enzymatic Extraction of Proanthocyanidins from País Grape Seeds and Skins. Food Chem 2015, 168, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gligor, O.; Mocan, A.; Moldovan, C.; Locatelli, M.; Crișan, G.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Enzyme-Assisted Extractions of Polyphenols – A Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2019, 88, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.C.; Viganó, J.; Sanches, V.L.; De Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Pizani, R.; Rostagno, M.A. Simultaneous Extraction and Analysis of Apple Pomace by Gradient Pressurized Liquid Extraction Coupled In-Line with Solid-Phase Extraction and on-Line with HPLC. Food Chem 2023, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, B.; Betiku, E. Process Optimization of Solvent Extraction of Seed Oil from Moringa Oleifera: An Appraisal of Quantitative and Qualitative Process Variables on Oil Quality Using D-Optimal Design. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Campos-Requena, V.H. Antioxidant Compound Extraction from Maqui (Aristotelia Chilensis [Mol] Stuntz) Berries: Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. Antioxidants 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete, J.; Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Aranda, M.; Vega-Gálvez, A. Application of Vacuum and Convective Drying Processes for the Valorization of Pisco Grape Pomace to Enhance the Retention of Its Bioactive Compounds. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists AOAC: Official Methods of Analysis; 1990.

- Bailey, M.J.; Biely, P.; Poutanen, K. Interlaboratory Testing of Methods for Assay of Xylanase Activity; 1992; Vol. 23.

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Sun, B. Novel Approach for Extraction of Grape Skin Antioxidants by Accelerated Solvent Extraction: Box–Behnken Design Optimization. J Food Sci Technol 2019, 56, 4879–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents; 1965.

- Grajeda-Iglesias, C.; Salas, E.; Barouh, N.; Baréa, B.; Panya, A.; Figueroa-Espinoza, M.C. Antioxidant Activity of Protocatechuates Evaluated by DPPH, ORAC, and CAT Methods. Food Chem 2016, 194, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Gálvez, A.; Poblete, J.; Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Uribe, E.; Bilbao-Sainz, C.; Pastén, A. Chemical and Bioactive Characterization of Papaya (Vasconcellea Pubescens) under Different Drying Technologies: Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Potential. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2019, 0, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaia, C.M.; Costa, M.M.; Lopes, P.A.; Pestana, J.M.; Prates, J.A.M. Use of Grape By-Products to Enhance Meat Quality and Nutritional Value in Monogastrics. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, P.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Bernal, C. Production of Antioxidant Pectin Fractions, Drying Pretreatment Methods and Physicochemical Properties: Towards Pisco Grape Pomace Revalue. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2022. [CrossRef]

- Barriga-Sánchez, M.; Campos Martinez, M.; Cáceres Yparraguirre, H.; Rosales-Hartshorn, M. Characterization of Black Borgoña (Vitis Labrusca) and Quebranta (Vitis Vinifera) Grapes Pomace, Seeds and Oil Extract. Food Science and Technology (Brazil) 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ramos, F.; Cañas-Sarazúa, R.; Briones-Labarca, V. Pisco Grape Pomace: Iron/Copper Speciation and Antioxidant Properties, towards Their Comprehensive Utilization. Food Biosci 2022, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.N.S.; Tonon, R. V.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Galdeano, M.C.; Iacomini, M.; Santiago, M.C.P.A.; Almeida, E.L.; Freitas, S.P. Grape Seed Pomace as a Valuable Source of Antioxidant Fibers. J Sci Food Agric 2019, 99, 4593–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, C.; Costa, G.N.S.; Cabezudo, I.; da Silva-James, N.K.; Teles, A.S.C.; Cruz, A.P.G.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Tonon, R. V.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.P. Towards Integral Utilization of Grape Pomace from Winemaking Process: A Review. Waste Management 2017, 68, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefied, F.; B Ahmed, Z.; Yousfi, M. Optimization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities From Pistacia Atlantica Desf. Galls Using Response Surface Methodology. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozan, B.; Altinay, R.C. Accelerated Solvent Extraction of Flavan-3-OL Derivatives from Grape Seeds. Food Sci Technol Res 2014, 20, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.A.; Santoyo, S.; Prodanov, M.; Reglero, G.; Jaime, L. Valorisation of Grape Stems as a Source of Phenolic Antioxidants by Using a Sustainable Extraction Methodology. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huamán-Castilla, N.L.; Campos, D.; García-Ríos, D.; Parada, J.; Martínez-Cifuentes, M.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S.; Pérez-Correa, J.R. Chemical Properties of Vitis Vinifera Carménère Pomace Extracts Obtained by Hot Pressurized Liquid Extraction, and Their Inhibitory Effect on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Related Enzymes. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, A.; Borrull, F.; Pocurull, E.; Marcé, R.M. Pressurized Liquid Extraction: A Useful Technique to Extract Pharmaceuticals and Personal-Care Products from Sewage Sludge. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2010, 29, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajha, H.N.; Ziegler, W.; Louka, N.; Hobaika, Z.; Vorobiev, E.; Boechzelt, H.G.; Maroun, R.G. Effect of the Drying Process on the Intensification of Phenolic Compounds Recovery from Grape Pomace Using Accelerated Solvent Extraction. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 15, 18640–18658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Bin, S.; Vallini, V.; Fava, F.; Michelini, E.; Roda, A.; Minnucci, G.; Bucchi, G.; Tassoni, A. Recovery of Polyphenols from Red Grape Pomace and Assessment of Their Antioxidant and Anti-Cholesterol Activities. N Biotechnol 2016, 33, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D.; Claus, A.; Andreas Schieber, R.C. A Novel Process for the Recovery of Polyphenols from Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Pomace. 2005, 70.

- Marianne, L.C.; Lucía, A.G.; de Jesús, M.S.M.; Eric Leonardo, H.M.; Mendoza-Sánchez, M. Optimization of the Green Extraction Process of Antioxidants Derived from Grape Pomace. Sustain Chem Pharm 2024, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiapelo, L.; Blasi, F.; Ianni, F.; Suvieri, C.; Sardella, R.; Volpi, C.; Cossignani, L. Optimization of a Simple Analytical Workflow to Characterize the Phenolic Fraction from Grape Pomace. Food Bioproc Tech 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, N.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, C. Skin Cell Wall Ripeness Alters Wine Tannin Profiles via Modulating Interaction with Seed Tannin during Alcoholic Fermentation. Food Research International 2022, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabra, A.; Netticadan, T.; Wijekoon, C. Grape Bioactive Molecules, and the Potential Health Benefits in Reducing the Risk of Heart Diseases. Food Chem X 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).