1. Introduction: the Sun from an Ideal Disk to the First Telescopic Sights

The Sun appears as a bright disk, and its dazzling luminosity prevented, normally, observations of its surface. Since the antiquity, the Sun was worshipped as a god. The Egyptians (section 2.) represented it either as a disk or as a sphere, with some elements suggesting direct observations of the corona and prominences during total eclipses. In Christianity (section 3.) St. Francis of Assisi in 1225 created his Cantico di Frate Sole, where the Sun well represents God’s qualities. Galileo Galilei (section 4.) with his telescope first recognized in 1611 sunspots as belonging to a rotating photosphere, proving the spherical nature of the Sun. The solar symbol was frequently used in the Catholic Church (section 5.) appearing also in the coat of arms of the Jesuit pope Francis. The occasional observations of giant sunspots in the middle age (section 6.) with naked eye or through pinholes in a camera obscura could have risen the question on the solar rotation before the telescope? The answer is suggested by the evolution of the largest sunspots of the XXV solar cycle observed by nake eyes (section 7.) and with a camera obscura (section 8.) in order to better understand the quality of the pre-telescopic observations. With the pinhole-meridian line of St. Maria degli Angeli in Rome the sunspots are visible (section 9.), and the largest pinhole-meridian line, realized by Paolo Toscanelli in 1475 in the Dome of Florence, could have shown the largest sunspots, but the Sun was in the Spörer Minimum (1460-1550). The limb darkening (section 10.) is another clue for the solar sphericity, but the pinhole introduces itself a limb darkening of the image. The invention of the telescope occurred just after the first map of the Moon drawn with the unaided eye (section 11.) when the Sun restored its sunspots activity (section 12.).

2. The Representation of the Sun in Ancient Egypt

The Sun is there, it has been always there, and only in the last four centuries, the question about its physical nature become meaningful.

The solar mythology in Egypt is very complex, and its discussion would exceed largely the scope of this work. The representations of the solar disk or sphere are well known. In the

Figure 1 the Pharaoh Akhenaton is represented in Tell-el-Amarna, Egypt.

The right side is a scheme of the physical correspondences between the traditional representation in Egypt, of the Sun, and the phenomena visible during a total eclipse of the Sun. In

Figure 2 another three-dimensional example is from the Edfu temple.

The winged Sun include wings and one or two cobra (

uraeus): their position starting always from the solar limb, recall the prominences visible only during total eclipses. The wings fully stretched, the streamers, occurring during the minimum phases of the solar cycles (

Figure 3).

Despite of the faint luminosity of the solar corona, and especially this one during the deepest solar minimum (720 days of blank Sun) occurred in 2009 – 2010, the memory of this feature, along with the prominences can be unforgettable for an observer. The red prominences at the start of the totality and toward the end attracted my sight during the total solar eclipse of 1999 in Riedering, Bayern, Germany. Since then this was my lens through which I considered the Egyptian solar symbols.

3. The Sun of Christianity

Christ is called the “Sun rising from on hig” (Luke 1:68-79), and to see the great brightness of the Sun are needed eagle’s eyes. This legend and the text of Revelation (4:6-8) is at the basis of representing St. John the Evangelist with an eagle, because he was the author of the most theological gospel. His sight was able to penetrate the secrets of God, as the eagle can aim fixedly to the Sun. Examples of Christ-Sun are in

Figure 4.

St. Francis of Assisi in 1225 composed the Cantico di Frate Sole expressing in poetry the representative role of God played by the Sun.

Laudato Si’ mi Signore per frate Sole

Lo quale è iorno et allumini noi per lui

Et ellu è bellu et radiante cum grande splendore

Di te porta significatione (Blessed be, Oh Lord for brother Sun/ which is the day and You illuminate us by him / and it is nice and radiant with great splendor / of You it brings signification)

Among the Christian symbols the Sun was used to represent Charity (E.g. in St. Francis of Paula.

https://www.christianiconography.info/francisDiPaola.html ), Wisdom (E.g. in the tumb of the Pope Benedict XIV in St. Peter’s, a woman with a gilded Sun on the breast, St Peter's - Monument to Benedict XIV) and Jesus (

Figure 4). Representing God with the Sun is based on the Psalm 18, 6

“In Sole posuit tabernaculum Suum” (

In the Sun He posed his tent). The representations of the solar symbols are flat, both before and after the evidences of a spherical Sun, not only in painting and mosaics, but also in sculptures.

4. The Sun of Galileo and His Contemporaries: Planet or Star?

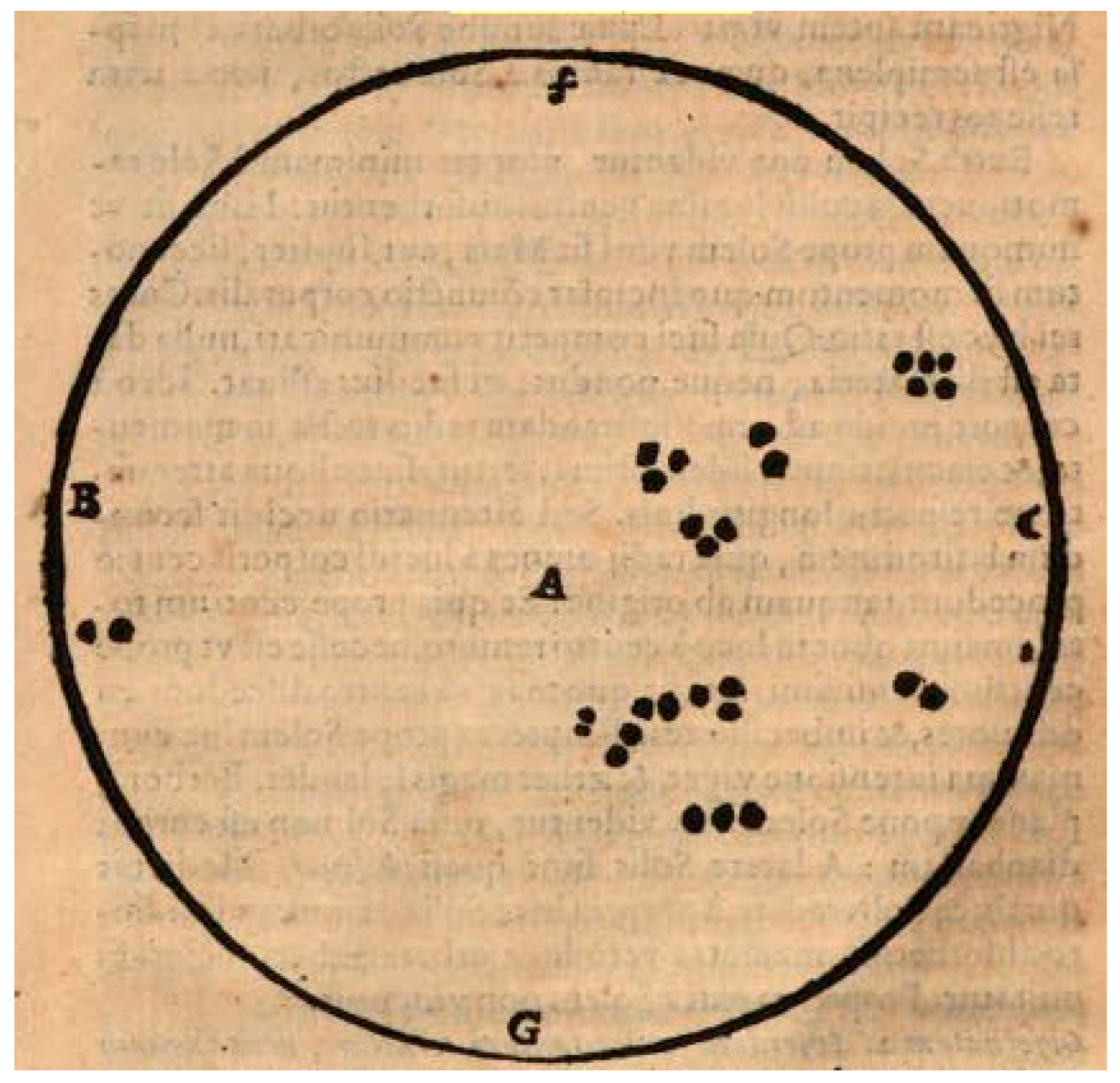

Galileo (1613) following the motion of the spots, interpreted them as located on the solar surface. Scheiner (1630) interpreted them as small clouds orbiting around the Sun and in the

Borbonia Sidera (Tarde, 1620), they were considered as

moving stars (Planet in Greek means “moving star”, that’s why the moving planets around the Sun were called “stars”. Also the Earth orbiting around the Sun become technically a star, and this was the debate of the times). Jean Tarde (1561-1636) was a French prelate, historian and astronomer (Jean Tarde – Wikipedia), who met personally Galileo in 1614.

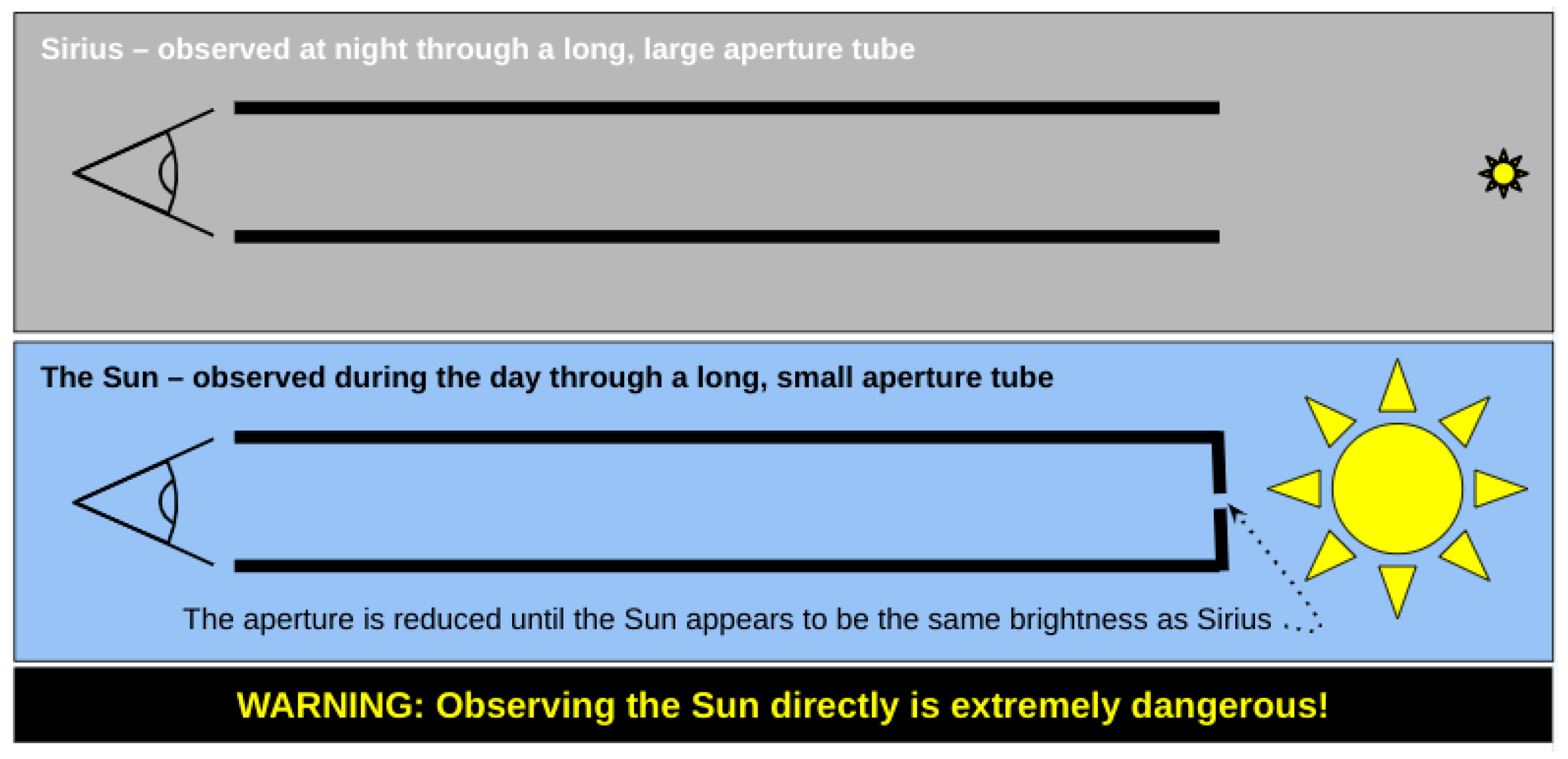

Giordano Bruno (Giordano Bruno - ORDINE DEI PREDICATORI) (1548-1600) considered the stars as very far suns (Bruno, 1584), but his speculation did not pose on specific measures. A similar idea, supported by computations and observations was the one of Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695): the Dutch scientist Christian Huygens made an image of the Sun through a pinhole in a darkened room. He varied the size of the pinhole until the image seemed equal in brightness to an image of Sirius, the brightest star. Since the pinhole admitted 1/27,000 of the light of the Sun, Huygens concluded that Sirius was 27,000 times farther away than the Sun (it is actually 543,900 times farther away and substantially more luminous than the Sun, see

Figure 6). (Chris Impey and P. Grey, E. Brogt, A. Baleisis on Teach Astronomy - Measuring Star Distances (consulted 12/5/2025))

From a physical point of view the Copernican hypothesis gave to the Sun (To a point very close to it). the central role of the Universe, but in the view of Bruno the Sun become a star in the modern sense. Galileo, instead, when not dealing with “fixae” or fixed (stars), was still considering the possibility of the motion of stars. In this respect, the Earth orbiting around the Sun was a (moving) star (Galileo, Saggiatore, 1624). The Greek word for moving star is “planétes”. The difference with the other stars was only kinematic, while for Bruno started to be a physical difference: the stars were far suns. The clear difference between this view and the modern one required near three centuries to mature. Still at the end of XIX century, Camille Flammarion considered the possibilities that the Sun would be inhabited (Astronomie Populaire, 1875) as all other planets.

5. The Sun and the Jesuits

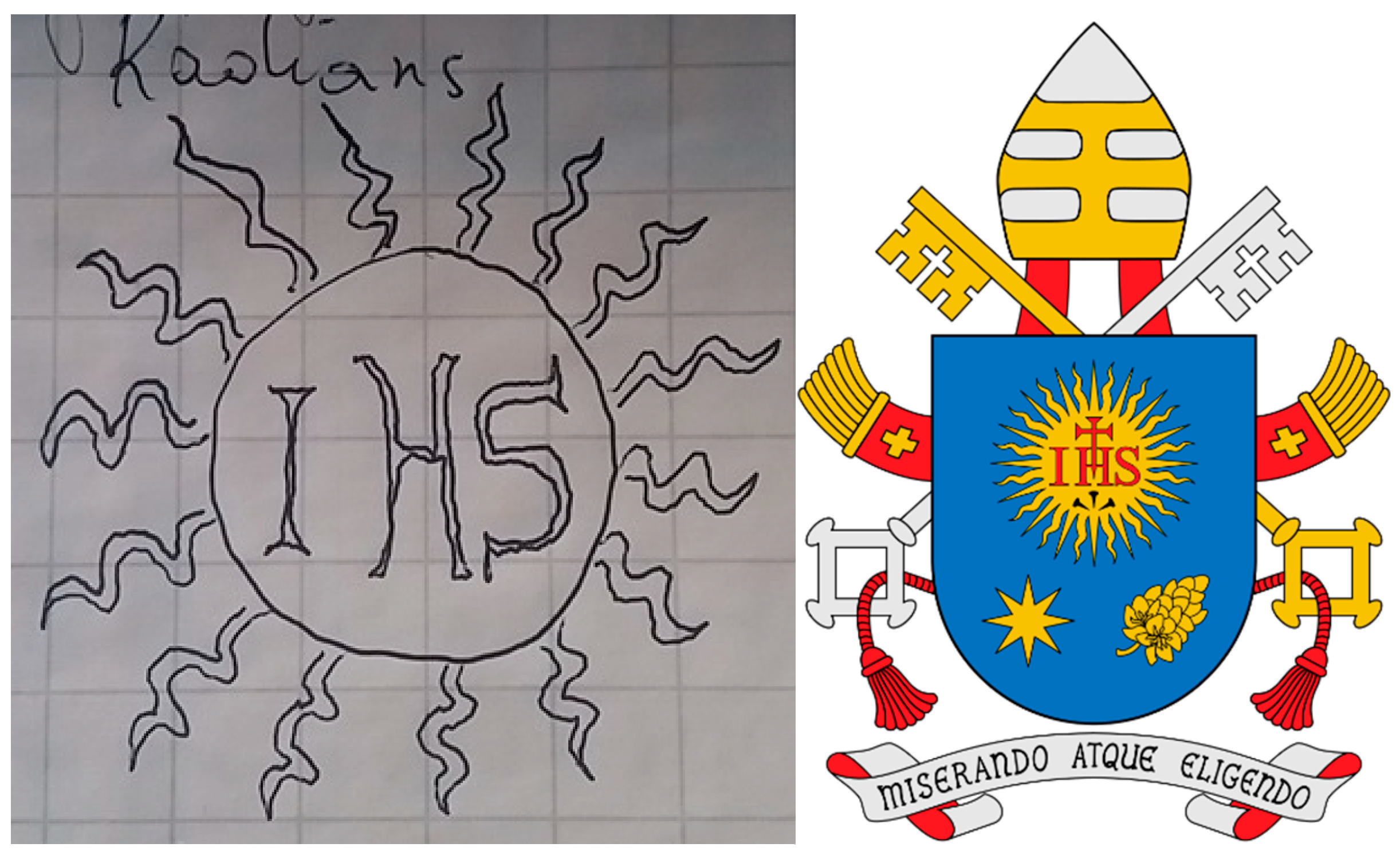

The radiant Sun (

Figure 7) is the symbol characterizing the Company of Jesus, founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1540. It has been also a main task of the scientific studies of the Company along the centuries.

The contemplation of the Nature is part of the spirituality of St. Ignatius (MG XV Rome 2018 HR 2 Angelo Secchi and Astrophysics), being the Nature created by the Word of God. A strong development of observational and theoretical studies occurred at the headquarter of Jesuits, the Collegio Romano. The astronomical tradition started with Christopher Clavius (1535-1612) continued spreading all over the World. Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), Giovanni Paolo Lembo (1570-1618), Orazio Grassi (1583-1654), Christoph Scheiner (1573-1650), Christoph Grienberger (1561-1636), Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598-1671), Francesco Maria Grimaldi (1618-1663), Rudjer J. Boscovich (1711-1787) Francesco De Vico (1805-1848), Angelo Secchi (1818-1878) are part of a largely incomplete list, even limited to solar astronomy.

The idea that the sunspots were bodies extraneous to the nature of the Sun was functional to preserve the perfection of the celestial body used to represent the perfection of God. The first Jesuits who observed the sunspots were also willing to find a coherence with this paradigm.

No spot could be imagined in a divine symbol, and this has been a major concern in the early debate between scientists and theologians. The Jesuits, before accepting the Copernican system adopted the Tychonic system to preserve the agreement between the Scriptures and the physics of the Cosmos (

Figure 8, the famous

Sol ne movearis (Sun, stand thou still) of Joshua 10, 12), through father Scheiner, were oriented toward a spotless Sun, with opaque bodies orbiting it.

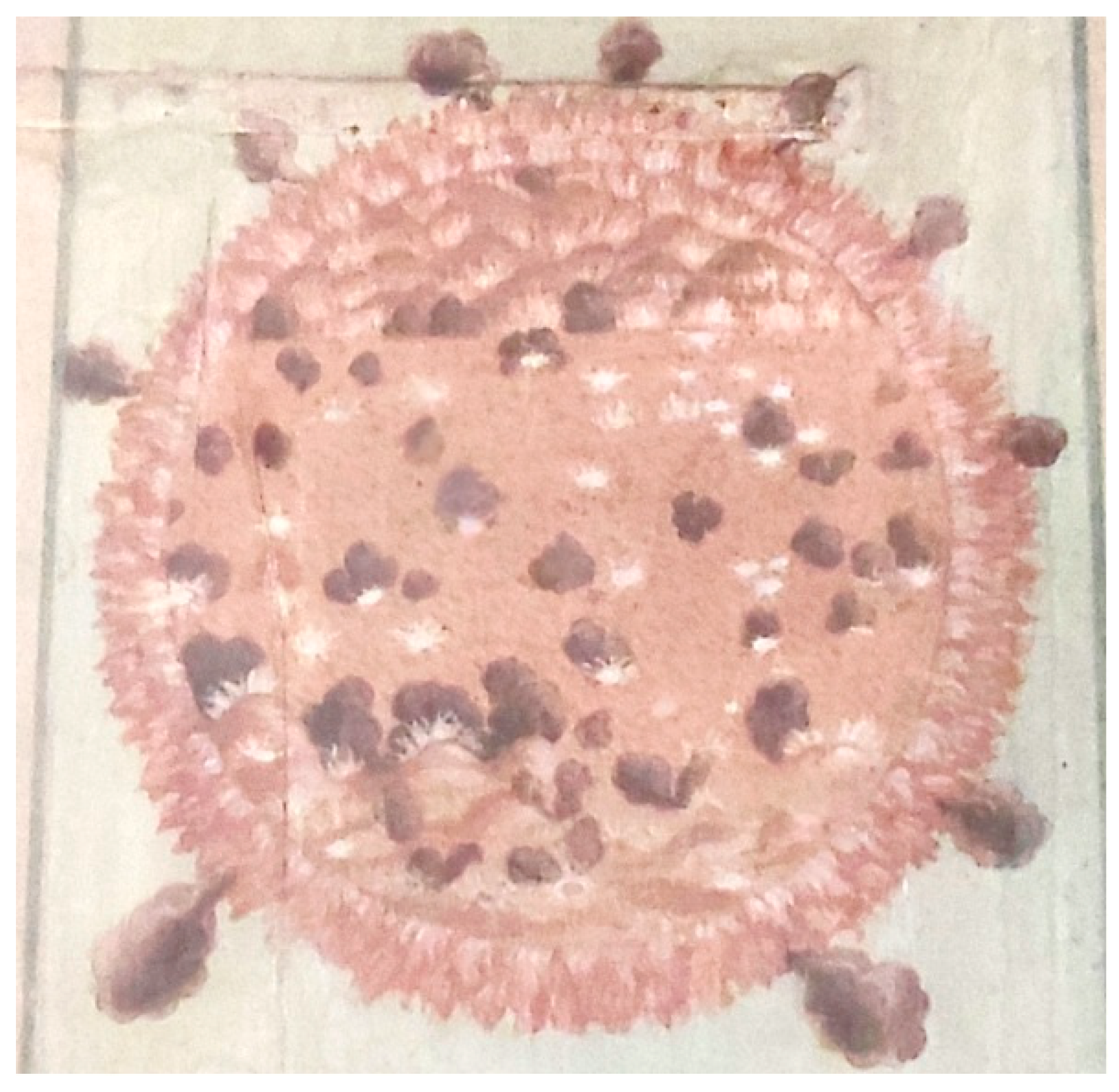

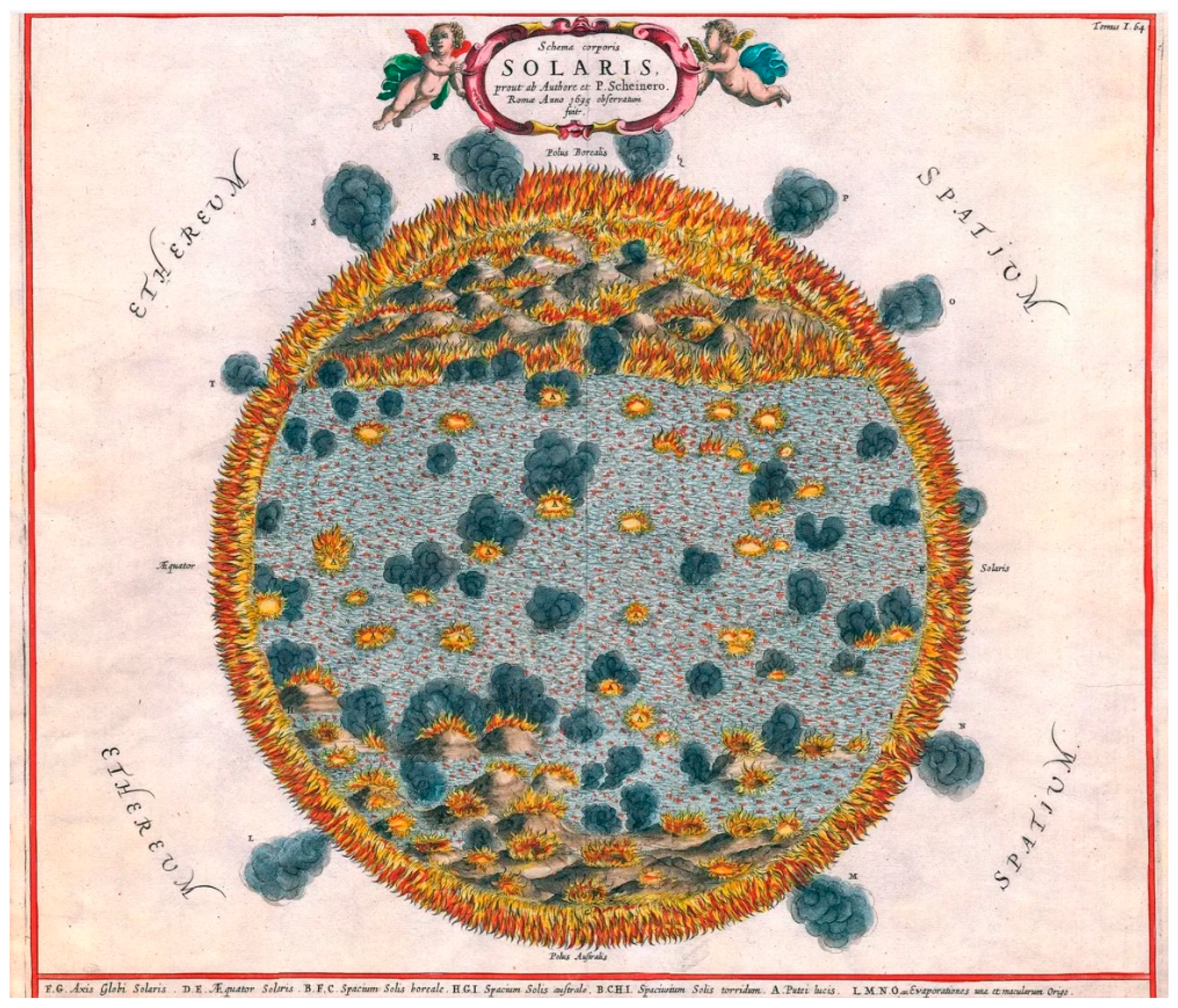

The representations of the Sun in

Figure 5 and in

Figure 9 (whose original is probably the image in

Figure 10, published by (Kircher 1665) are separated by 15 years at least: the solar activity appear very intense. Many spots in

Figure 5, and a volcanic activity with many clouds in

Figure 9. It is relevant that this image of the Sun, among the scholars, as the Cardinal De Zelada, remained iconic up to the end of 18th century, for at least 163 year, notwithstanding the improvement of the optics during that century.

The interpretation given to the sunspots is of clouds of smoke ejected by volcanoes on the solar surface. On the solar limb there are flames that recall the spicules, described by father Angelo Secchi (1818-1878) only two centuries after Scheiner and Kircher, using a very good refractor of Merz, fully exploiting the achromatic doublet, patented in 1758 by John Dollond (John Dollond – Wikipedia). About the plumes of smoke out of the limb, they might include the memory of some observations of prominences made during total eclipses or some exceptional observation at sunset/sunrise. Secchi (1884) (A. Secchi (manuscript dated 1870) Il Sole, Firenze (posthume edition 1884) reproduced in Gerbertus20.pdf p. 127-128.) reported such an observation of Pietro Tacchini at sunset on the 8 August 1865 in the Mediterranean sea onboard a steam ship. The white spots are the faculae, that the artist reported all over the Sun, but in reality are visible only at the royal zones of the limb (±50° from the solar equator).

The original figure, copied on the wooden window, is the following.

6. Naked Eye Sunspots in the Middle Age

The solar activity and the solar rotation have been observed occasionally and reported in the medieval chronicles, but they have not been recognized as sunspots on a rotating photosphere. It is noteworthy that Einhard, in the Vita Karoli Magni ((Einhard 817)

https://thelatinlibrary.com/ein.html#32 Chapter 32

et in sole macula quaedam atri coloris septem dierum spatio visa (transl.

And in the sun, a certain spot of black color was seen over the course of seven days.) written circa 817-836 AD.) mentioned a sunspot appeared for seven days in 813 AD (This episode was already quoted by Galileo (1613) in his first work dedicated to the sunspots). Another mention is in the Annales Regni Francorum (Royal Frankish Annals) (

Nam et stella Mercurii XVI. Kal. Aprilis visa est in sole quasi parva macula, nigra tamen [“tamen” missing in MSS group E], paululum superius medio [D3, E: media] centro eiusdem sideris [B5, C3, E3, E6, E7: syderis], quae a nobis octo dies conspicitur. Sed quando primum intravit vel exivit, nubibus impedientibus [B1, B4, C1, D3: imped.] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00218286241238731#fn5 translation:

For on the 16th day before the Kalends of April, the star Mercury was seen in the sun as a small spot, black however, slightly above the middle of the center of that same star, which is visible to us for eight days. But when it first entered or exited, it was obscured by clouds.) for 17 march 807 AD, lasted eight days and interpreted as the planet Mercury passing in front of the Sun (Neuhäuser et al., 2024).

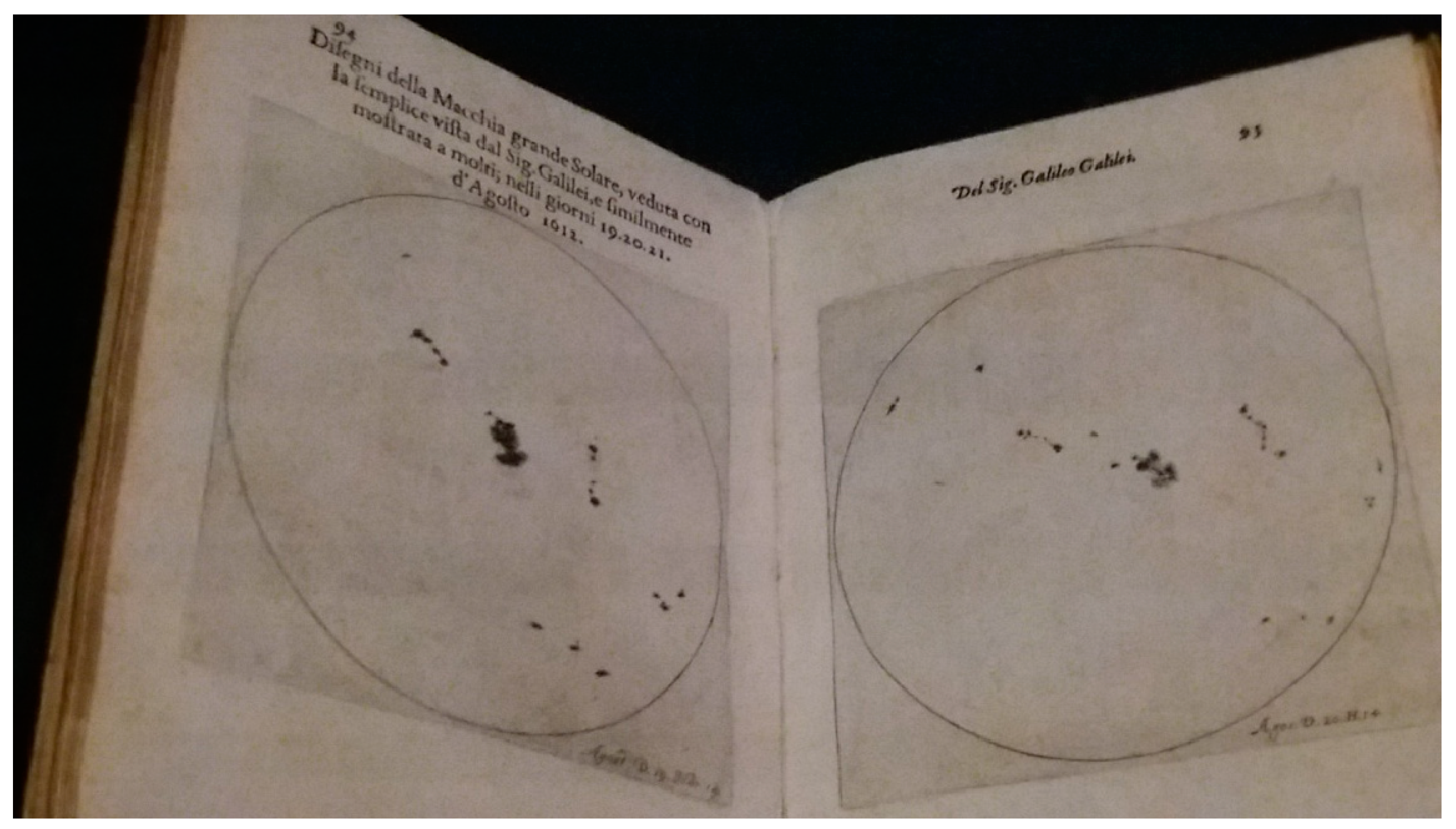

Galileo himself was able to see a naked-eye sunspot in 1612. He added a postscript on the “Disegni della macchia grande solare, veduta con la semplice vista dal Sig. Galilei, e similmente mostrata a molti, nelli giorni 19, 20, 21 d’Agosto 1612” to say that while he was undertaking his observations, a sunspot appeared which was so large it could be seen with the naked eye between 19 and 21 August 1612; and this was shown to many people. This is included in his series of illustrations (

Figure 11).

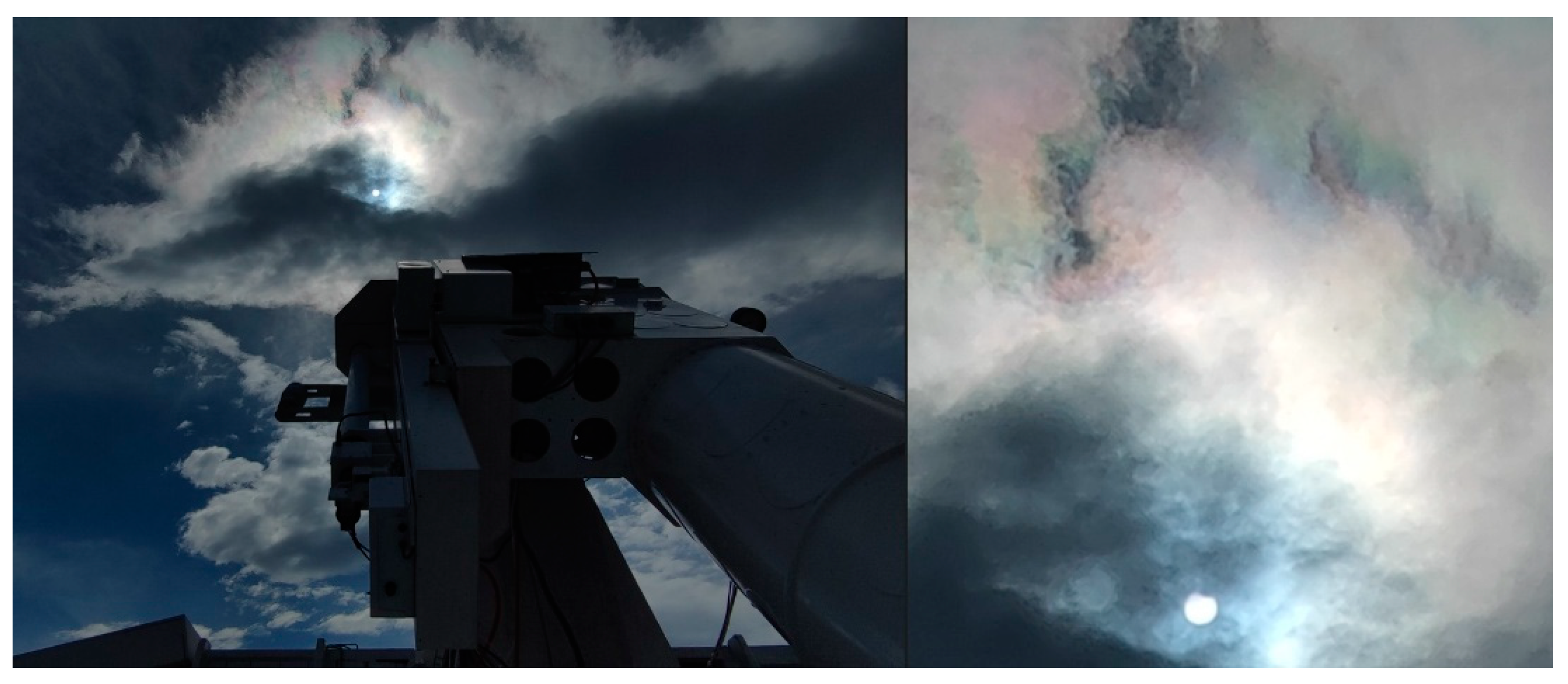

The observations with naked eyes of sunspots can be done only through a filter which is natural, as the fog (Schaefer 1993) (Vaquero 2007) (Vaquero 2007b), or through artificial filters as a smoked glass or a modern mylar filter. The visibility of the naked-eye spots can occur at sunset or sunrise from the sea, whit particular humidity conditions. There is no way to observe a sunspot on the Sun directly; only for a solar eclipse a very short glimpse (less than 0.1 s) may allow to see in the transient image left on the retina the lunar profile “biting” the Sun. In rare cases, as in

Figure 12, the clouds allowed for some instants to see the eclipse directly but their disomogeneity would not permit to observe the sunspots.

The eclipse of

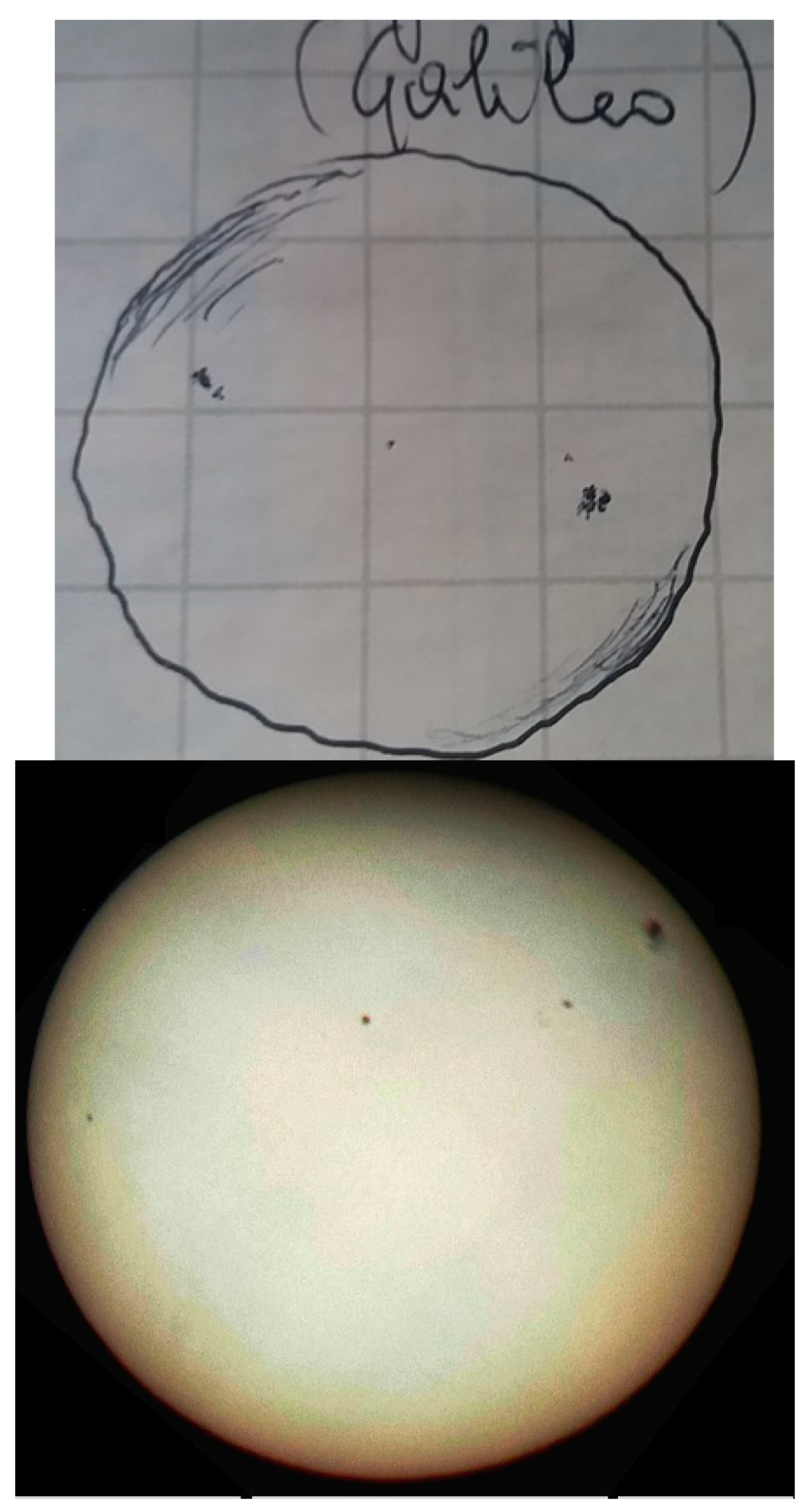

Figure 12 was visible to the naked eye at 15.2% of eclipse through that cloud. The Moon profile was 294” inside the solar disk. A large sunspot has a lower contrast than the Moon’s profile on the Sun; the dimension of AR 4079 at its maximum reached about 150”x50” included the penumbra (as in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

7. Naked Eye Sunspots in 2025: Experiencing the Eye Resolution

A dark spot is 104 times as intense as the atmospheric halo of the Sun, when the Sun is high over the horizon and the sky is clear (This has been verified observing the Sun with the spot AR4079 with a pinhole + filter (10-4 transmittance) with the right eye and the sky backround aournd the Sun without filters with the left eye: the darkened part of the filtered Sun was as luminous as the sky background).

The luminosity of the photosphere can be reduced to 10-4 through a Density 4 mylar filter or, much better, through projection (section 5).

The angular dimension of the sunspot has to be around 0.5’, the angular resolution of the eye in daylight, even if the eye is not in direct sunlight. The diameter of the pupil in such conditions is 3 mm, and the Rayleigh criterion gives about 33” of resolution, but a sunspot has to be bigger than that to emerge from the still bright photosphere. Moreover, to be distinguished, the sunspot has also to be distant from the limb, which is darker than the central part of the Sun. This explains why a big and steady sunspot on the Earthside photosphere for 14 days, is actually visible to the naked eye only for 8 days, as at the time of Charlemagne (AR 4079

https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/en/solar-activity/region/14079.html was seen with naked eye until 9 may 2025, and the days of visibility are 9 over 15, from 28 April to 12 May.[1] The same active region, after a whole solar rotation, at the beginning of June 2025 catalogued as AR4100, was less compact, with a smaller umbra, and it was no more visible to the naked eye. The same active region come again visible as AR 4100 on May 25 at the limb, and on May 27 it was already visible to a small pinhole camera (knowing that it was there) but never to the naked eye.

https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/en/solar-activity/region/14100.html had its largest area of 440 MH with umbral dimension < 1’. Another relevant sunspot is the bigger one of AR 4087, 270 MH on May 16. The diameter of the umbra was 13”, while the penumbra get 36”. It is just below the limit of visibility with naked eye.

https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/en/solar-activity/region/14087.html The distance from the limb on 16 May 2025 would have been enough to be visible to the naked eye, if larger. If the spot would have to be discovered, it should have been more evident. The umbra AR 4079 was 75” nearly 6 times larger than AR 4087, that permitted its observation with naked eye, in limiting conditions).

We can say –experimentally with AR 4079 in May 2025- that the longitude of a great sunspot with respect to the central solar meridian has to be comprised within 60°E and 60°W to be enough separated from the darker limb. To get visible to the (alerted) naked eye the dimension of the umbra has to be larger than 1’ at the center of the disk. Its visibility, if the spot is stable, can last for 8 days. The sunspot at Charlemagne epoch had to be at least 3’ wide to be evident under the fog, homogenous thin clouds or at sunrise or sunset, when the Sun appears dimmer. The present observations were made knowing that there was a big sunspot, while a true discovery has not to be alerted.

For these observation I used: mylar filter D4, grey filter 13%, a pinhole of 1.75 mm to compensate the eye defects and another orange filer, because the Sun was at 1.5 airmasses, and it was too bright to permit to see the sunspots on it without reducing the whole luminosty.

Consequently, the conditions of visibility of a sunspot to normal eyes without refractive defects are:

1. Dimension of the umbra larger than one arcminute;

2. Distance from the limb at least 3 arcminutes.

8. The Camera Obscura for Pinholes and Telescopes

These iconographic and historical premises describe the long period before the telescope’s invention, when the observations of sunspots were casual and not understood.

The architects in Florence obtained representations in perspective using a

Camera Obscura (King, 2009) illuminated by a pinhole. The largest pinhole-meridian line to study the obliquity of the ecliptic and shift of the Julian calendar around the summer solstice was realized by Paolo Toscanelli in 1475 in the Dome of Florence (Archivio dell’Opera del Duomo di Firenze. Quaderno Cassa, serie VIII-I-61, anno 1475, carta 2v MCCCCLXXV Spese d’Opera:

E adì detto [16 agosto, n.d.a.] lire cinque soldi quindici dati a Bartolomeo di Fruosino orafo, sono per il primo modello di bronzo di libbre 23 once 4, fatto per Lui a istanza di maestro Paolo Medicho per mettere in sulla lanterna, per mettere da lato di drento di chiesa per vedere il sole a certi dì dell’anno. Lire 5 soldi 15. Source: Lo Gnomone del Duomo di Firenze | Renzo Baldini (Baldini 2005)). Ulugh Begh in Samarcand did realize a great gnomon with solar projection in 1435, along with a stellar catalogue. Giacomo Della Porta (1590) described the principles of the

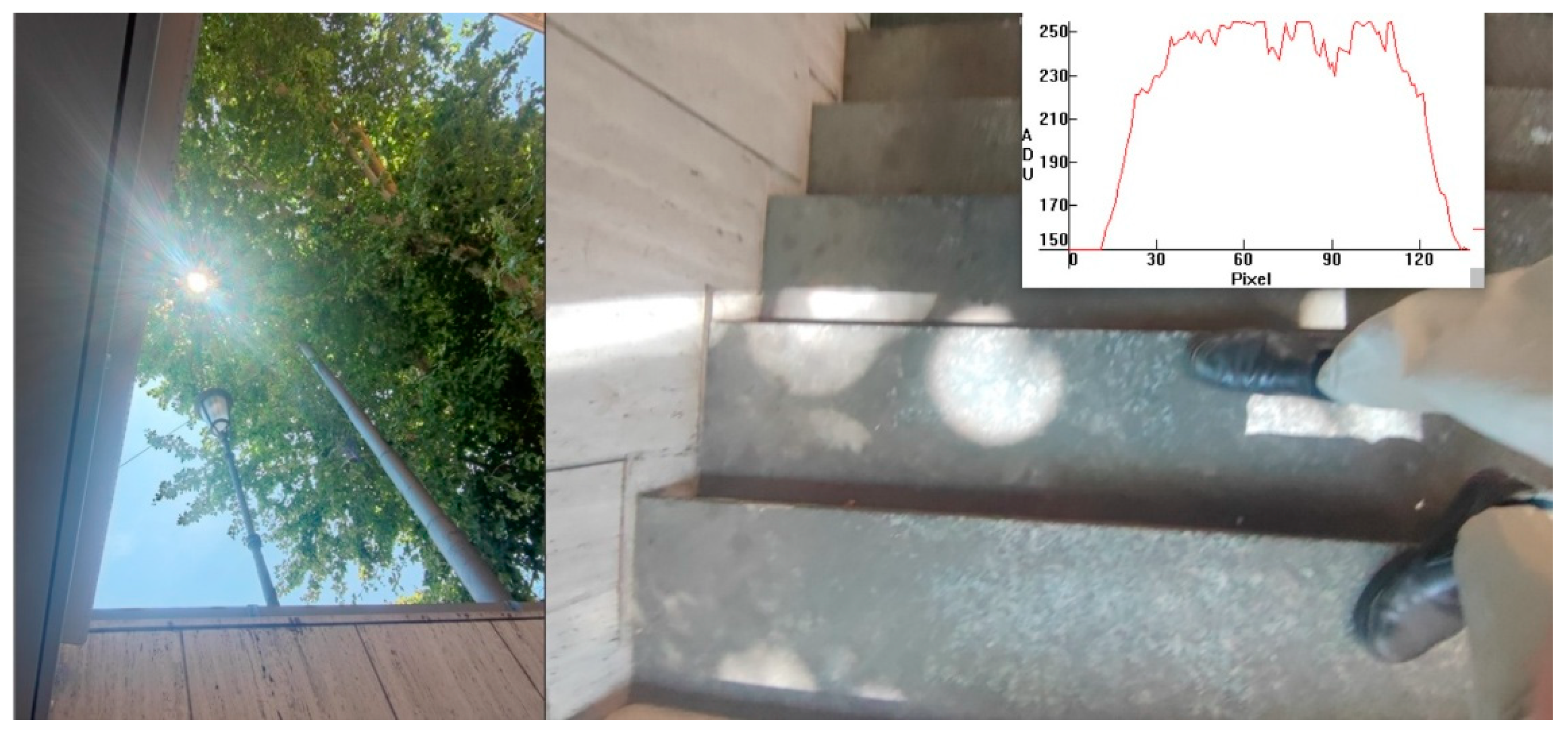

Camera Obscura and Kepler 1571-1630 used in astronomy (Kepler, 1604; Sigismondi and Fraschetti, 2001). The visibility of sunspots with a pinhole, at 2 meters of distance is possible for sunspots as small as 13” and 3’ from the limb. The pinhole can be 2 mm wide (Another confirmation comes from the sunspots on 30 May 2025, AR 4100 and AR 4099, both with umbrae of 20” and visible at 2.5 m of distance through the shades producing accidental pinholes. The best pinhole produces the fainter circular image. The accidental pinholes created by the leaves of a plane tree (Platanus Occidentalis) did not work for seeing the spots (

Figure 15). The experience leading to the 2002 article on American Journal of Physics

(77) were made with different pinholes and with plane mirrors, without glass coating, to send the solar image at distances up to 20 m, with the vision of the sunspots. The experiences with pinholes presented here are intentionally less elaborated, to simulate the conditions for the discovery of sunspots by chance), and the camera does not require a perfect darkening.

Christoph Scheiner (1570-1654) used a parallactic machine to follow the projected solar image in the Camera Obscura (Scheiner, 1630) and to make the best drawings of his time (Secchi, 1884).

Here we use the Camera Obscura to assess the details observable and the physical phenomena that can be followed in the days after, in order to understand how that technique has contributed to increase the knowledge of the Sun.

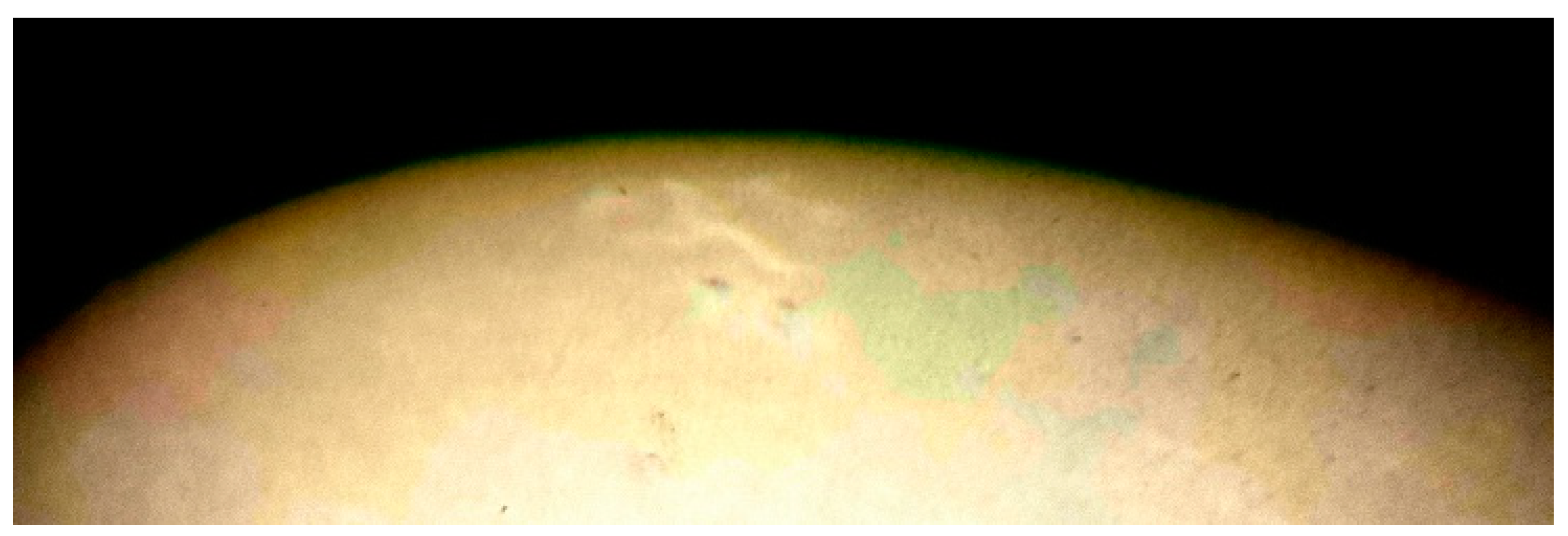

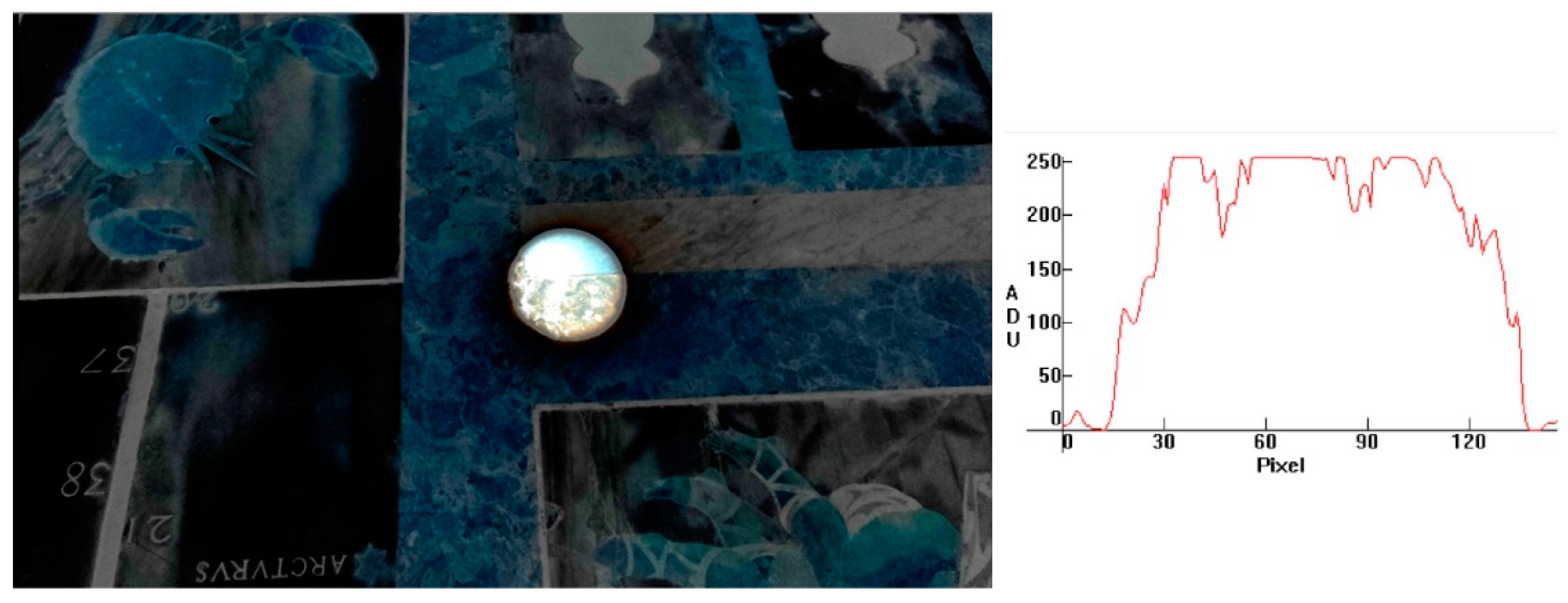

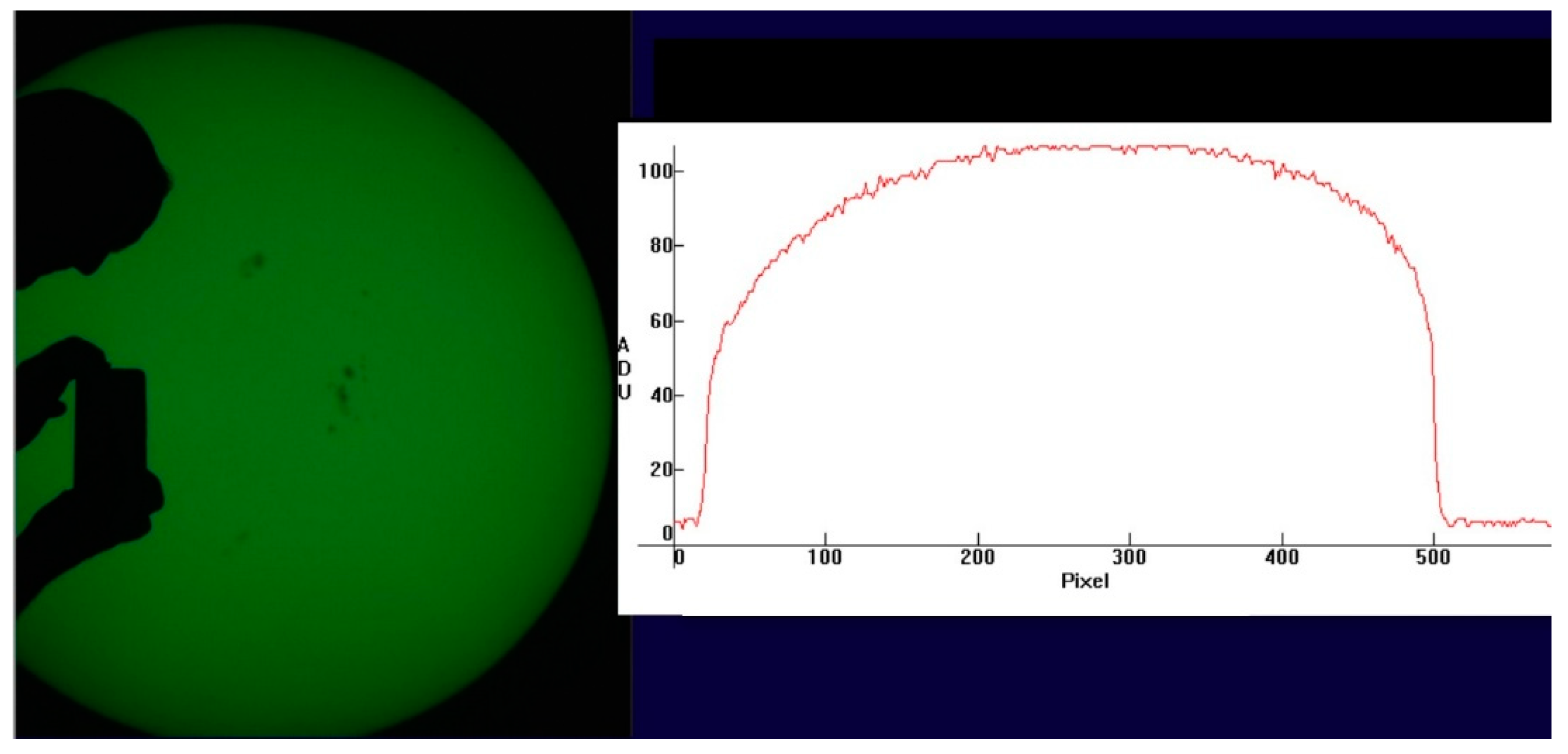

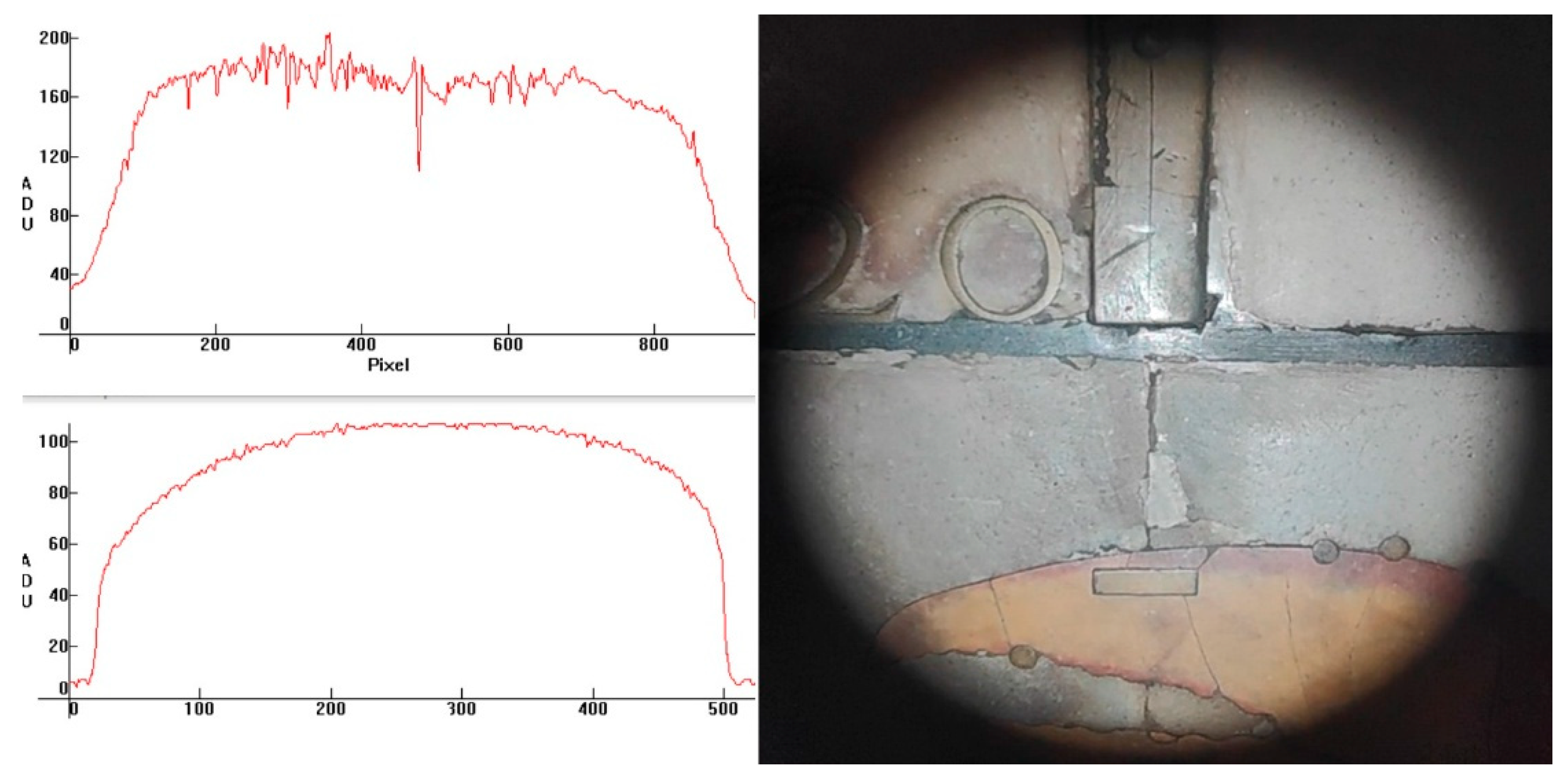

The sunpots and the limb darkening are clearly visible in whole image of the Sun in figure 15 (The limb darkening function ranges from 30 ADU (limb) to 190 ADU (inner part) and it is photographed from 1 m of distance). The further details of umbra and penumbra and the faculae are well visible. The images here presented are obtained in a camera obscura, with the telescope introducing the light, to reproduce the observations described by Christoph Scheiner (1573-1650) in the Rosa Ursina (Scheiner, 1630).

The projecting telescope, used in these experiments, has a 60 mm-doublet (The optical quality of the telescope is superior with respect to 1630, so we can indee see better the details than in 1630. The doublet was not yet invented (by J. Dollond in 1758). To futher enhance the view I added a green photographic filter (wide band) before the objective lens), and a prismatic mirror before the eyepiece, to deviate the light so that the Sun is projected on the wall, and not on the floor as Scheiner (1630) did. The observation on the wall, at 540 cm of distance, is very comfortable: there is enough time to detect the faculae and the tiniest sunspots. The estimate of the daily sunspot number R (R is from Rudolph Wolf and it is R=10G+N, with G the number of sunspots’ groups and N the number of sunspots), is always with a 10% close to the official averages (This is an average over several observers, certified at SILSO,

https://www.sidc.be/SILSO/datafiles). The intensity of the image, is about 3/1000 of the direct sunlight (The estimated value is given by squaring the ration of the objective and of the image’s diameters (6/105)

2=3.3·10

-3), and it is enough bright to show also the sky background within 1° the field of view of the telescope (I have seen clearly a bird fliyng on the line of sight, across the Sun, until it was a solar radius outside the photosphere, even if the solar limb appeared sharp. There is a reamining luminosity of the background below 29 ADU (there is a non linear correspondance with real intensity)).

The faculae are visible in white light only near the limbs, to about 1/10 of the solar diameter, even if Scheiner and Kircher represented them even at the center (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Once the rotation of the Sun was established, the presence of the faculae at the center could have been imagined, while the explanation of their invisibility at the solar center requires the knowledge of modern atomic physics (It is due to the absorption of photons by hydrogen atoms partially ionized in the solar atmosphere, Donald H. Menzel, Our Sun (Harvard, 1949), chapter 7, p. 205 in the Italian Edition Il Nostro Sole (Faenza, 1981)).

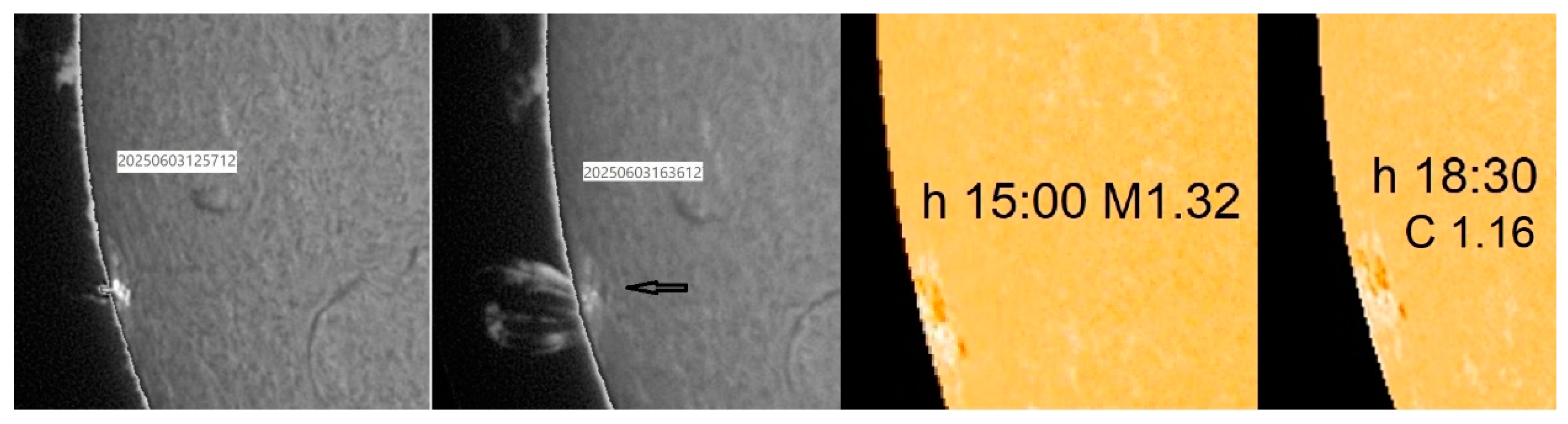

Variations in the luminosity of the faculae, with occasional white light flare, or with flares at the limb, are possible (This study has been conducted on C-class and M-class flares, in particular M3 on 26 May and M9 on 25 May 2025 erupted from AR 4098 and M1.4 on 26 May from AR 4100, the same spot as AR4079 after half a solar rotation in the solar far side. In the aforementioned flares of May there not was an optical counterpart visible in the camera obscura projection. The visible counterpart was seen with the M1.44 flare of 3 June 2025 13:03Z, observed clearly at M1 phase in Camera Obscura. The transient remained visibile for 10 minutes, among the two spots of AR 4105, then fading to the normal facular level; the bright facula is visible also in the satellite SDO images of 13:00Z (M1.32), and faded at 16:30Z (C1.16)), even if their occurrences are documented only after the Carrington event in 1859 (Carrington 1859) occurred on a great sunspot, where the contrast is much larger (In

Figure 14 the sunspot’s umbra is 10 ADU over 200 ADU of the solar photosphere around it). Scheiner and Kircher, to account the aspect of

Figure 9, especially for the “light wells” may have occasionally observed a flare in white light near the limb.

9. The Sunspots in the Churches

V. S. vedendo in chiesa da qualche vetro rotto e lontano cader il lume del Sole nel pavimento, vi accorra con un foglio bianco e disteso, che vi scorgerà sopra le macchie. [Galileo, Istoria e Dimostrazioni sopra le macchie solari, Lettera 2] If your Excellency see the light of the Sun falling on the floor of a church, through some broken glass, go there with a white and plain paper, and you will see the spots.

Already thousands years ago the Nature gave the possibility to see the spots, even not sharply defined as through a telescope. Galileo in the same Letter mentioned above expressed this thesis. An accidental pinhole can be found in windows or through the leaves of a tree, as already described by Aristotle (Problems, book 3). The solar eclipses were seen in this way during the partial phases since the antiquity.

Nevertheless accidental pinholes through the leaves of the trees, or through the glasses of a church’s window, did not permit to anticipate the discovery of sunpots.

In 1475 Paolo Toscanelli realized a pinhole in the dome of St. Maria del Fiore, at 90 meters of height, to study the position of the giant solar image (1 meter) formed on the Northern nave of that Cathedral, that when it was built (inauguration 1436) it was the largest church in the World. The idea of Toscanelli anticipated, with a stable instrument, the consideration of Galileo of more than a century, but the sunspots were not observed (The possibility to see the sunspots with a lensless pinhole, sent me to the meridian line of St. Maria degli Angeli in September 1999. The sunspot AR 8692 [

https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/it/attivita-solare/regione/8692.html ] was there and it was possible to detect it as an enhancement of penumbra in the image projected on a white paper. At that time the pinhole was of irregular shape, about 4 cm x 2 cm. The image of the Sun was 30 cm x 20 cm, so the pinhole dimension was about 3’ wide, while the sunspot was only 25” wide at its maximum. To have a clear visibility of the sunspot its angular width should be comparable with the angular width of the pinhole at the position of the image).

Another city which could have been hosted the discovery of the sunspots is Bologna. There Egnazio Danti (1536-1586) realized a great pinhole-meridian line in the Basilica of St. Petronio in 1577. Cassini reshaping in 1655 the same instrument and creating his Heliometer, fixed the pinhole width as 1/1000 of its height (Heilbron, 2001). Probably the same proportion was made by Danti, but he did not have time to use the instrument, because he was called in Rome for the Reformation of the Calendar (Gregorius XIII 1582) and for the decoration of the Gallery of the Maps, now part of the Vatican Museums by the Pope Gregorius XIII. The Pope created him bishop of Alatri. The last historical instrument that could have anticipated the discovery of the sunspots is the pinhole camera of the Torre dei Venti in Vatican made by Danti in 1580 (Sigismondi, 2014). The ratio pinhole-height for the meridian of the Tower of Winds is 14:5180 or 1/370.

The lack of observations of the sunspots in the end of 15th and during the 16th century is an observational proof of the duration of the minimum of Spörer, with the Sun without big sunspots. The observations with such instrument may have not been systematic, but there were at least three instruments in Italy where the sunpots could have been seen, before the discovery with the telescope. The definition of the sunspots with the pinholes is very smooth, but it is enough for following them for some days, during the solar rotation.

Finally it is noteworthy that Kepler observed two big sunpots in 1607 (Kepler 1609) with a pinhole camera, normally used to measure the magnitudes of solar eclipses: he drawn sunspots on May 18/28 and made verifications with naked eye (Hayakawa et al., 2024). He believed firstly to have seen Mercury on the Sun, but the conditions of visibility di not last enough to anticipate the discovery of sunspots, even of only a few years before Galileo.

The case of Kepler, a very keen observer, not because his sight, but for his capability to “intus-legere” or reading inside the things, that even observing spots did not recognize them beyond accidents, is also significant. Even if the spots were there, the low resolution of the instrument and their rapid variability did not help to recognize them.

10. Limb Darkening and rotation: the Proofs of the Spherical Sun

The Sun by analogy with the Moon (section 11.) was considered a sphere, but the observing proof could come either from the rotation of the sunspots, either from the limb darkening. There exists an instrumental limb darkening of the image, due to the geometrical optics of rays from a disk uniformly luminous through the pinhole-objective.

The solar disk presents a limb darkening, evident in the first regions near the limb, but this effect appear entangled with the instrumental limb darkening produced by a pinhole. Moreover when the pinhole is small the effects of geometrical optics are entangled with wave optics due to the diffraction occurring in a narrow opening.

Is it possible to distinguish the solar limb darkening from the pinhole limb darkening? The latter is dependent on the pinhole dimension, and it enlarges the geometrical image D¤=f·tan(θ¤) of the Sun by the width d of the pinhole itself.

Therefore the observed image is D==f·tan(θ

¤)+d where f is the focal length of the pinhole (distance pinhole-image) d is the diameter of the pinhole, and θ

¤ is the angular diameter of the Sun. The pinhole d<<D allows better measurements, below d/D<30 (In the case represented in figure 18 all parameters are known, and D

¤=198.7 mm, d=25 mm, and the measured image is 225.6 mm wide. The difference between D and D

¤ is 26.9 mm, just 1.9 mm more than the pinhole dimension. The solar effect is unnoticeable at this level of accuracy).

The Limb Darkening of the Sun has to be observed with a telescope able to show the required detail to disentangle it from the pinhole’s shadowing of geometrical optics, or from the diffraction spread of the solar limb through the tiny pinhole. The main characteristics of the solar Limb Darkening is its steeper rise to the inflection point with respect to the pinhole’s limb darkening which is shallower in dependence of the pinhole’s diameter.

The limb darkening without focusing optics could not help to perceive the spherical nature of the Sun.

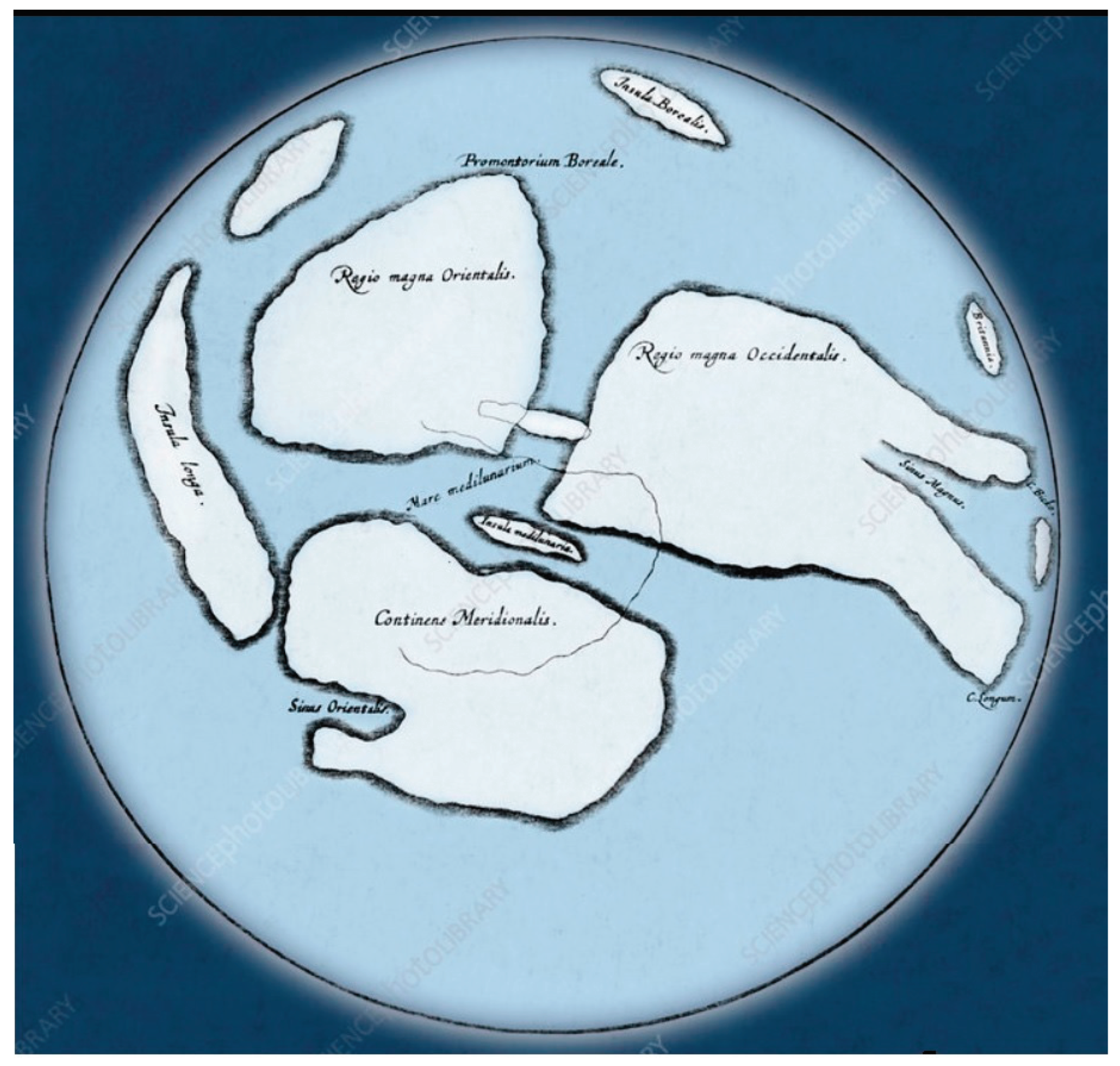

11. The Moon Was Already Spherical and with Spots

Once considered the solar nature of the stars, or the stellar nature of the Sun, we remain with the point of its sphericity. The three dimensional representations in Egypt (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) show already a sphere, but the definitive proof arrived in 1610 with the telescope. The analogy with the Moon, also regarding its spots, could have contributed to the idea of a spherical Sun with spots, which is not evident by itself.

Antares 20x600 telescope, Xiao-Mi11 smartphone.

The motion of the terminator and its shape contributes to evidence the spherical nature of the Moon. The contrast of the moonspots is rather shallow, and their distance from the brighter limb introduces a problem of visibility (E. g.: Mare Crysium, visible in

Figure 20 at mid left, near the Western lunar limb, has a relative intensity (ADU) of 130/180 with respect to the lunar Terrae, brighter, around it. The limb is generally brighter than all Terrae. The distance between the Mare Crysium to limb is around 2’. The Moon and the Sun have approximately the same angular diameter, and the longitude of the center of Mare Crysium is 59° W. This feature is the smaller visible with the naked eye, using the pinhole and the grey Moon filter at 13% of transmission, to avoid to be bleached by the luminosity of the Moon, better to do in twilight with the sky still blue: it is at the limit of the resolving power of the eye, as the greatest sunspots that should be within ±60° of longitude from the central meridian (section 7.). Mare Crysium was reported also in the map of William Gilbert (1601), and named

Britannia (

Figure 21)).

The presence of permanent spots is a characteristic of our natural satellite, they are known since the most antique ages but strangely the Moonspots did not have names until a few years before the invention of the telescope, when William Gilbert (1544-1603) physician to Queen Elizabeth I and the discoverer of terrestrial magnetism drafted one.

The resolution at naked eye allowed understanding the permanent nature of the moonspots, while only the changing terminator showed the spherical nature of the Moon. The geocentric orbit, producing the lunar phases, compensates the absence of visible rotation: the lunar rotation is synchronized with the orbit 1:1. But the solar rotation was discovered by Galileo after the observation of the sunspots. The solar limb darkening helped to perceive the three-dimensionality of the Sun.

The telescope of Galileo gave immediately the boost to understand the nature of the Moon, thanks to the amount of details visible. The uncertainty of the ancient theories on the lunar spots (e.g. Dante in Divine Comedy, Paradise 2 (Dante’s Paradiso – Canto 2 - Dante's Divine Comedy) or Gilbert with continents floating on a vaste ocean), do vanish at the first sight with the telescope, and the modern planetography as well as celestial mechanics started in a modern way.

12. Conclusions: The Right Instrument at the Right Moment

The Sun had always spots during the human history, but the possibility to see them did not coincide with the actual discovery, even if great pinhole’s meridian lines were operating since 1475 in Florence, 1577 in Bologna and 1580 in the Vatican. It is reliable that the Spörer minimum of the solar activity (1460-1550) contributed with a long lasting “blank Sun” completely spotless or with small spots, without the largest groups that become achievable to the unaided and unbleached eye, as it occurred in AD 807 and 813 when occasional great spots were observed up to 8 consecutive days.The solar activity over millennia has been reconstructed (Usoskin, 2023) through some proxies, because the observation of great sunspots is too scattered before the invention of the telescope. This paper may suggest an indirect proof that the recovery of the sunspots’ solar cycle after the Spörer minimum was rather smooth and, if not completely spotless, without very great sunspots, that would have been noticed through many pinhole-instruments.The improvements of the technique in building pinhole cameras for observing the Sun did permit Kepler to observe the sunpots in 1607, but he did not recognized their solar nature because he did not continue these observations or because the spots rapidly evolved loosing umbra and gaining penumbra, that is not visible through a pinhole (The sunspot AR 4100, already mentioned in the previous notes, at the third rotation has lost the large umbra, which is visible to the naked eye or through a pinhole, and splitted into a complex region with prevalence of penumbra, which is much less visible without a telescope). After the invention of the telescope and the discovery of the sunpots, Kepler observed them through pinholes cameras (Sigismondi and Fraschetti, 2001), before having the possibility to use the telescope of Galileo.The discovery of the sunspots occurred both with the telescope and after the end of the Spörer minimum. The theory of the instruments as trigger ((Galison 1997), quoted in (Dyson 2012)) of a scientific revolution is confirmed in this work, but also the Nature’s conspiracy of a long-term solar activity minimum phase contributed to set the date to 1610 and not a century before. The cultural environment was not ready to accept a Sun with spots. The Dominican Tommaso Caccini in 1614 with the homily on “Viri Galilaei” accused Galileo (CACCINI, Tommaso in "Dizionario Biografico" e (Ricci-Riccardi 1902)) to move the Earth around a spotted Sun. Caccini’s disposition was based on a symbolic idea of the Sun as representative of God (Sections 1. and 2.), and it would not change quickly in any case. The same disposition one century before would not have prevented the discovery of the sunspots. It was the lack of sunspots since 1460 for the Spörer minimum, and the lower resolution of a giant pinhole camera, with respect to a telescope, that prevented the discovery of the sunspots, not a fixed paradigm of thinking.

References

- (Aristotele 2002) Aristotele, Problemi, a cura di M.F. Ferrini, Aristotele Problemi Introduzione, traduzione, note e apparati, Milano: Bompiani Collana Testi a fronte, n. 62. 2002.

- (Baldini 2005) Baldini, Renzo Lo Gnomone del Duomo di Firenze | Renzo Baldini (2005) (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Bruno 1584) Bruno, Giordano, De L’Universo et infiniti mondi, Venezia 1584 available online DIALOGO TERZO - De l'Infinito, Universo e Mondi di: Giordano Bruno (accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Carrington 1859) Carrington, Richard, C., Description of a Singular Appearance seen in the Sun on September 1, 1859, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 20, p.13-15 (1859) Available online 1859MNRAS..20...13C (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Dante 1321) Dante, Divina Commedia, Paradiso canto 2 (1321). English version Dante’s Paradiso – Canto 2 - Dante's Divine Comedy (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Danti 1576) Danti, Egnatio, Usus et Tractatio Gnomoni Magni, Bononiae, (1576).

- (Einhard 817) Eihnard, Vita Caroli Magni, 32 (c. 817-836) Available online https://thelatinlibrary.com/ein.html (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Dyson 2012) Dyson, Freeman J., Is Science Mostly Driven by Ideas or by Tools?, Science 388 1426 (2012) Available online dyson-science-ideas-or-tools.pdf (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Flammarion 1880) Flammarion, Camille, Astronomie Populaire, Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion Editeurs (1880).

- (Galilei 1613) Galilei, Galileo, Delle macchie solari / Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari, Roma: presso Giacomo Mascardi (1613) Available online: Delle macchie solari/Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari - Wikisource . (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- (Galilei 1623) Galilei, Galileo, Il Saggiatore, Roma: presso Giacomo Mascardi (1623) Available online: Il Saggiatore - Wikisource. (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- (Galison 1997) Galison, Peter L., Image and Logic, A Material Culture of Microphysics, University of Chicago Press (1997).

- (Gilbert 1605) Gilbert, William, De mundo nostro sublunari, British Library Royal Ms. 12 F. XI.

- (Gionti 2018) Gionti, Gabriele, The Scientific Legacy of Fr. Christopher Clavius, S.J. up to Fr. Angelo Secchi, S.J., XV Marcel Grossmann Meeting, Roma: Sapienza University 1-7 July 2018 (2018) Abstract available online MG15-HR2-Gionti (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Gregorius XIII 1582) Gregorius Papa XIII, Inter Gravissimas, Bulla Pontificalis, Tuscolo, Villa Mondragone (1582) Inter Gravissimas (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Hayakawa 2024) Hayakawa, Hisashi,Koji Murata,E. Thomas H. Teague, Sabrina Bechet,and Mitsuru Sôma, Analyses of Johannes Kepler’s Sunspot Drawings in 1607: A Revised Scenario for the Solar Cycles in the Early 17th Century, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 970:L31 (2024) https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ad57c9. [CrossRef]

- (Heilbron 2001) Heilbron, John L., The Sun in the Church, Cathedrals as Solar Observatories, Boston: Harvard University Press. 2001.

- (Hoskin 1977) Hoskin, Michael, The English Background to the Cosmology of Wright and Herschel. In: Yourgrau, W., Breck, A.D. (eds) Cosmology, History, and Theology. Springer: Boston, MA (1977).

- (Impey 2023) Impey, Chris, and P. Grey, E. Brogt, A. Baleisis, From the Earth to the stars in 1668 AD on Teach Astronomy - Measuring Star Distances (consulted 12/5/2025) From the Earth to the stars in 1668 AD – e=mc2andallthat (consulted 5 June 2025).

- (Kepler 1604) Kepler, Johannes, Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena, Frankfurt: apud C. Marnum et H. J. Aubri (1604).

- (Kepler 1609) Kepler, Johannes, Phaenomenon singulare seu Mercurius in Sole Lipisiae: Thomae Schureri (1609).

- (King 2009) King, Ross, La Cupola di Brunelleschi, Rizzoli: Milano (2009).

- (Kircher 1665) Kircher, Athanasius, Mundus Subterraneus, Amsterdam: Joannem Janssonium et Elizeum Weyerstratem (1665).

- (Menzel 1949) Menzel, Donald H., Our Sun (Harvard, 1949), chapter 7, p. 205 in the Italian Edition Il Nostro Sole, Faenza: Faenza editrice (1981).

- (Neuhäuser 2024) Neuhäuser, Ralf and Dagmar L. Neuhäuser, Occultation records in the Royal Frankish Annals for A.D. 807: Knowledge transfer from Arabia to Frankia?, Journal for the History of Astronomy vol. 55 issue 3 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1177/00218286241238731.

- (Ricci-Riccardi 1902) Ricci-Riccardi, Antonio, Galileo Galilei e Fra Tommaso Caccini, il processo di Galileo nel 1616 e l'abiura segreta rivelata dalle carte Caccini, Firenze: Successori Le Monnier (1902).

- (Pumfrey 2011) Pumfrey, Stephen, The Selenographia of William Gilbert: His Pre-Telescopic Map of the Moon and His Discovery of Lunar Libration, Journal of History of Astronomy 42 (2011). [CrossRef]

- (Schaefer 1993) Schaefer, Bradely E., Visibility of Sunspots, The Astrophysical Journal 411, 909 (1993) Available online 1993ApJ...411..909S (Accessed 5 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- (Scheiner 1630) Scheiner, Christopher, Rosa Ursina, sive Sol ex admirando facularum et macularum suarum, Bracciano: Adrea Pheo (1630).

- (Secchi 1884) Secchi, Angelo, Il Sole, Firenze: Tipografia della Pia Casa di Patronato (1884) Available online https://www.icra.it/gerbertus/2023/Gerbertus20.pdf Accessed 5 June 2025.

- (Secchi 1870) Secchi, Angelo, Su di un antico disegno del sole dato dal P. Kircher, Pontificia Università Gregoriana 1870 (pdf online).

- pag. 1 and pag. 2 (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Sigismondi and Fraschetti 2001) Sigismondi, Costantino and Federico Fraschetti, Measuring the Solar diameter at Kepler’s time, The Observatory 121, 380 (2001) Available online 2001Obs...121..380S (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Sigismondi 2002) Sigismondi, Costantino, Measuring the angular solar diameter using two pinholes, American Journal of Physics 70 1157. 2002. [CrossRef]

- (Sigismondi 2014) Sigismondi, Costantino, La meridiana di Egnazio Danti nella Torre dei Venti in Vaticano: un'icona della riforma Gregoriana del calendario, Gerbertus 7, 81 (2014) available online La meridiana di Egnazio Danti nella Torre dei Venti in Vaticano (Accessed 5 June 2025). u.

- (Tarde 1620), Tarde, Jean, Borbonia sidera id est Planetae qui solis limina circumuolitant motu proprio ac regulari, falso hactenus ab helioscopis maculae Solis nuncupati, Paris: Joannem Gesselim (1620) Available online: Borbonia Sidera (pdf, google books).

- (Toscanelli 1475) Toscanelli, Paolo, Il passaggio del Sole dal più grande gnomone del mondo ; Astronomia in Cattedrale - Transito di Venere, 8 Giugno 2004 (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Usoskin 2023) Usoskin, Ilia. G., Living Review on Solar Physiscs 20, 2 (2023) Available online A history of solar activity over millennia | Living Reviews in Solar Physics (Accessed 5 June 2025).

- (Vaquero 2007) Vaquero, Josè Manuel, Historical sunspots observations: a review. Advances in Space Research 2007, 40, 929–941. [CrossRef]

- (Vaquero 2007b) Vaquero, Josè Manuel, Sunspots Observations by Theophrastus revisited. Journal of British Astronomical Association 2007, 117, 346.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author and not of MDPI and/or the editor. MDPI and/or the editor disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Figure 1.

Akhenaton and the Sun with its rays. Scheme of the solar disk’s attributes.

Figure 1.

Akhenaton and the Sun with its rays. Scheme of the solar disk’s attributes.

Figure 2.

The winged solar disk at the entrance of the temple of Edfu in Egypt (Credit: dreamstime.com #176071875).

Figure 2.

The winged solar disk at the entrance of the temple of Edfu in Egypt (Credit: dreamstime.com #176071875).

Figure 3.

The total eclipse of 22 July 2009 at Enewetak Atoll, Marshall Islands (Total Solar Eclipse 2009 image, Enewetak, Wide angle image of solar corona Authors: M. Durkmüller and P. Aniol).

Figure 3.

The total eclipse of 22 July 2009 at Enewetak Atoll, Marshall Islands (Total Solar Eclipse 2009 image, Enewetak, Wide angle image of solar corona Authors: M. Durkmüller and P. Aniol).

Figure 4.

Christus Helios in the Mausoleo dei Giuli, Vatican necropolis (III century) on the left. The image of Christ in the triumphal arch in the Basilica of St. Paul outside the walls, Rome (IV century- remade in XIX century) on the right side.

Figure 4.

Christus Helios in the Mausoleo dei Giuli, Vatican necropolis (III century) on the left. The image of Christ in the triumphal arch in the Basilica of St. Paul outside the walls, Rome (IV century- remade in XIX century) on the right side.

Figure 5.

Diagram of sunspots from Borbonia Sidera (Jean Tarde, 1620) (Diagram of Sunspots from Borbonia Sidera - Jean Tarde – Wikipedia).

Figure 5.

Diagram of sunspots from Borbonia Sidera (Jean Tarde, 1620) (Diagram of Sunspots from Borbonia Sidera - Jean Tarde – Wikipedia).

Figure 7.

The Sun with the acronym IHS, Iesus Hominum Salvator, created by St. Bernardin of Siena (St. Bernardine of Siena - Saints & Angels - Catholic Online). This symbol was adopted by St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, with the addition of the cross and the nails; it is in the coat of arms of Pope Francis (Coat of arms of Franciscus - Francisco (papa) - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre).

Figure 7.

The Sun with the acronym IHS, Iesus Hominum Salvator, created by St. Bernardin of Siena (St. Bernardine of Siena - Saints & Angels - Catholic Online). This symbol was adopted by St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, with the addition of the cross and the nails; it is in the coat of arms of Pope Francis (Coat of arms of Franciscus - Francisco (papa) - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre).

Figure 8.

“Move not, O Sun” Mosaic V century AD, St. Maria Maggiore, Rome.

Figure 8.

“Move not, O Sun” Mosaic V century AD, St. Maria Maggiore, Rome.

Figure 9.

The solar surface observed in Rome in 1635 by Christoph Scheiner and Athanasius Kircher, in the Hall of Meridian, Vatican Museums, Vatican. This is depicted on a wooden door created for the Cardinal Francesco Saverio De Zelada in 1798 (Musei Vaticani Catalogo Online : Inventario : Sportello di finestra proveniente dall'appartamento del card. Zelad... [MV.44213.0.0]).

Figure 9.

The solar surface observed in Rome in 1635 by Christoph Scheiner and Athanasius Kircher, in the Hall of Meridian, Vatican Museums, Vatican. This is depicted on a wooden door created for the Cardinal Francesco Saverio De Zelada in 1798 (Musei Vaticani Catalogo Online : Inventario : Sportello di finestra proveniente dall'appartamento del card. Zelad... [MV.44213.0.0]).

Figure 12.

The partial solar eclipse of 29 March 2025 at IRSOL, Locarno Switzerland. The eclipse reached 21% of magnitude 23 minutes before this photo.

Figure 12.

The partial solar eclipse of 29 March 2025 at IRSOL, Locarno Switzerland. The eclipse reached 21% of magnitude 23 minutes before this photo.

Figure 13.

Scheme of the telescopic Sun with sunspots and limb darkening, and the projection of the Sun on 9 May 2025 h 14:04 UT. The 105 cm wide image is projected in camera obscura by a telescope Antares 20x600 at 5.4 m.

Figure 13.

Scheme of the telescopic Sun with sunspots and limb darkening, and the projection of the Sun on 9 May 2025 h 14:04 UT. The 105 cm wide image is projected in camera obscura by a telescope Antares 20x600 at 5.4 m.

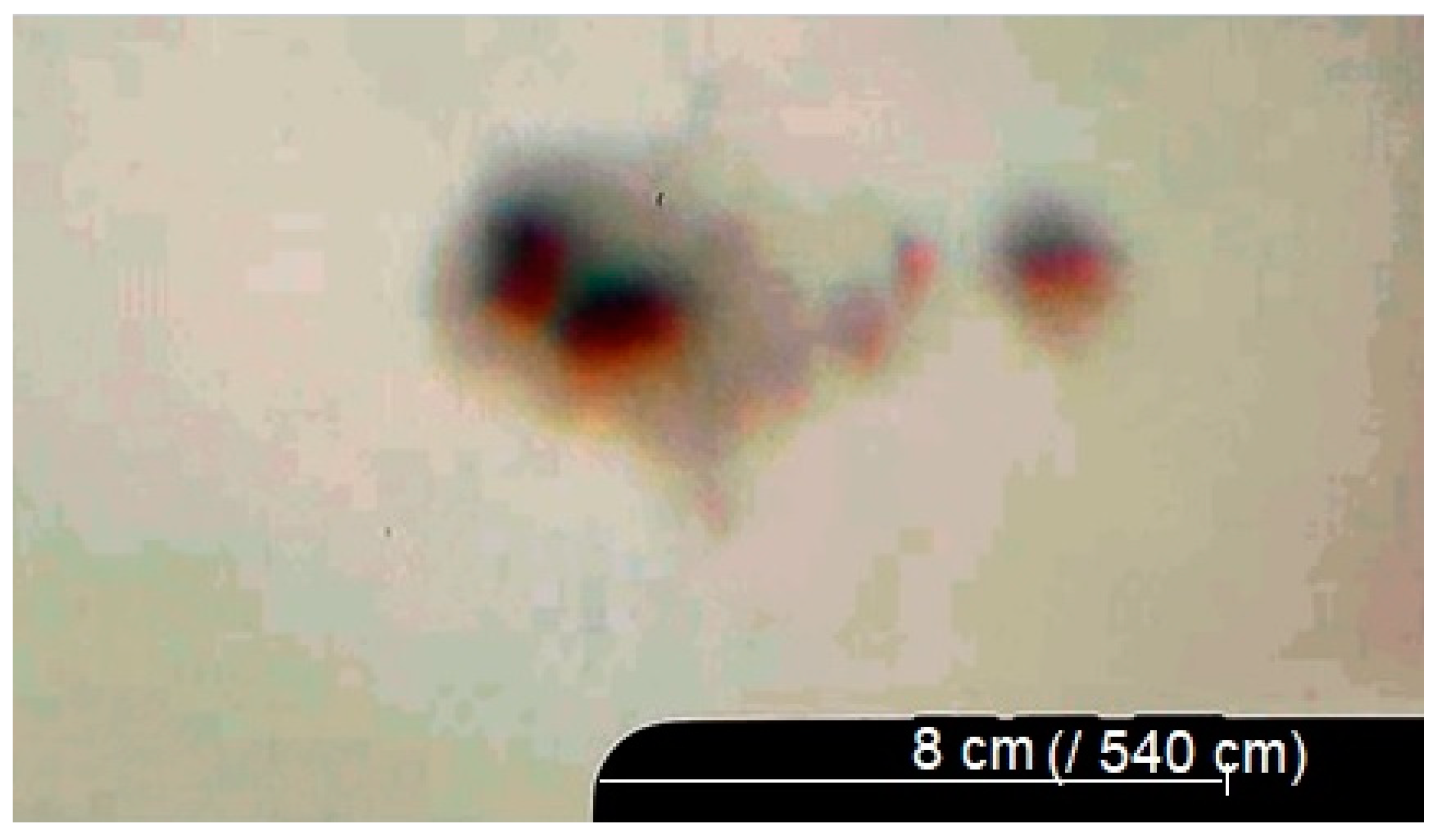

Figure 14.

The sunspot AR 4079 projected at 540 cm on 6 May 2025 while its area was 1250 millionth of solar hemisphere (The intensity of the umbra of AR4079 (6 May) is 10/200, the penumbra is 120/200; 200 is the intensity of the photosphere around the spot in ADU, Analogue-Digital Units. The photographic camera used here is the XiaoMi-11, it is not astronomical, while it reproduces well the eye sight (logarithmic response in intensity)).

Figure 14.

The sunspot AR 4079 projected at 540 cm on 6 May 2025 while its area was 1250 millionth of solar hemisphere (The intensity of the umbra of AR4079 (6 May) is 10/200, the penumbra is 120/200; 200 is the intensity of the photosphere around the spot in ADU, Analogue-Digital Units. The photographic camera used here is the XiaoMi-11, it is not astronomical, while it reproduces well the eye sight (logarithmic response in intensity)).

Figure 15.

Camera obscura projections: the brightest Facuale (AR4081 and AR 4086 on 12 May 2025) have a shallower contrast (The luminosity of the faculae versus the unperturbed surrounding photosphere is 185/155 in ADU. This is a good indication of the contrast observable with the naked eye in the camera obscura.) than Umbrae and Penumbrae.

Figure 15.

Camera obscura projections: the brightest Facuale (AR4081 and AR 4086 on 12 May 2025) have a shallower contrast (The luminosity of the faculae versus the unperturbed surrounding photosphere is 185/155 in ADU. This is a good indication of the contrast observable with the naked eye in the camera obscura.) than Umbrae and Penumbrae.

Figure 16.

The M1.44 flare on 3 June 2025 at 13Z on AR 4105 in H-alpha (grey-left Teide Observatory) and white light (orange-right SDO Satellite). The flare faded expanding out of the solar limb. The flare intensity in X-ray class is indicated (This flare was visible in Camera Obscura as the brightest facula over one month of observations (May 2025) and its fading was also visible.

https://youtube.com/shorts/zE76313vktU (Hα, 2 minutes after the X-ray peak) and

https://youtu.be/yji21KUFwi8 (green filter wide band 23 minutes after the X-rays peak)).

Figure 16.

The M1.44 flare on 3 June 2025 at 13Z on AR 4105 in H-alpha (grey-left Teide Observatory) and white light (orange-right SDO Satellite). The flare faded expanding out of the solar limb. The flare intensity in X-ray class is indicated (This flare was visible in Camera Obscura as the brightest facula over one month of observations (May 2025) and its fading was also visible.

https://youtube.com/shorts/zE76313vktU (Hα, 2 minutes after the X-ray peak) and

https://youtu.be/yji21KUFwi8 (green filter wide band 23 minutes after the X-rays peak)).

Figure 17.

Pinhole image through a plane tree (Platanus Occidentalis). The limb darkening is mainly due to the opening of the accidental pinhole’s aperture, evaluated to about 58 mm, convoluted with the solar limb darkening. From the limb to the maximum luminosity there are 24 pixels (370”), over a diameter of 123 pixels (300 mm, projected from about 30 m).

Figure 17.

Pinhole image through a plane tree (Platanus Occidentalis). The limb darkening is mainly due to the opening of the accidental pinhole’s aperture, evaluated to about 58 mm, convoluted with the solar limb darkening. From the limb to the maximum luminosity there are 24 pixels (370”), over a diameter of 123 pixels (300 mm, projected from about 30 m).

Figure 18.

The Sun at the Clementine Gnomon in St. Maria degli Angeli on 30 May 2025. The Limb Darkening is sharper than

Figure 15, because the pinhole is 25 mm wide. 22 pixel (333”) from limb to saturation over a diameter of 125 pixel (220 mm).

Figure 18.

The Sun at the Clementine Gnomon in St. Maria degli Angeli on 30 May 2025. The Limb Darkening is sharper than

Figure 15, because the pinhole is 25 mm wide. 22 pixel (333”) from limb to saturation over a diameter of 125 pixel (220 mm).

Figure 19.

the Limb Darkening Function (E-W) of the Sun on 31 May 2025 in Camera Obscura, through a 60 mm refracting telescope. The image has 104 cm of diameter and it is projected at 540 cm of distance from the telescope. AR 4099 and 4100 are well visible. West is 45° to the right.

Figure 19.

the Limb Darkening Function (E-W) of the Sun on 31 May 2025 in Camera Obscura, through a 60 mm refracting telescope. The image has 104 cm of diameter and it is projected at 540 cm of distance from the telescope. AR 4099 and 4100 are well visible. West is 45° to the right.

Figure 20.

The pinhole limb darkening at the Clementine Gnomon (31 May 2025 13:07:55 UT). The curve below in comparison is the solar limb darkening at the 60 mm refracting telescope (

Figure 19). The nearly linear rise of the upper curve is visible as a dimmer ring around the solar image.

Figure 20.

The pinhole limb darkening at the Clementine Gnomon (31 May 2025 13:07:55 UT). The curve below in comparison is the solar limb darkening at the 60 mm refracting telescope (

Figure 19). The nearly linear rise of the upper curve is visible as a dimmer ring around the solar image.

Figure 21.

The Moon on 5 and 8 May 2025 h 22 UTC. Photo by the author.

Figure 21.

The Moon on 5 and 8 May 2025 h 22 UTC. Photo by the author.

Figure 22.

The Moon of William Gilbert (1605): (Moon map by William Gilbert, 1603 - Stock Image - C052/7224 - Science Photo Library. The redrawn map is in Whitaker Ewen, Mapping and naming the Moon: A history of lunar cartography and nomenclature (Cambridge, 1999) and the research article is of (Pumfrey 2011), The Selenographia of William Gilbert: His Pre-Telescopic Map of the Moon and His Discovery of Lunar Libration, Journal of History of Astronomy

42 (2011)

https://doi.org/10.1177/002182861104200205 ) the Galilean

Maria are

Continents.

Figure 22.

The Moon of William Gilbert (1605): (Moon map by William Gilbert, 1603 - Stock Image - C052/7224 - Science Photo Library. The redrawn map is in Whitaker Ewen, Mapping and naming the Moon: A history of lunar cartography and nomenclature (Cambridge, 1999) and the research article is of (Pumfrey 2011), The Selenographia of William Gilbert: His Pre-Telescopic Map of the Moon and His Discovery of Lunar Libration, Journal of History of Astronomy

42 (2011)

https://doi.org/10.1177/002182861104200205 ) the Galilean

Maria are

Continents.

Table 1.

The pinholes meridian lines operating in the churches before the invention of the telescope were in Florence, Bologna (no more existant) and in Vatican. Their parameters are compared with the ones of St. Maria degli Angeli in 1999 and since 2018, after the restauration of the pinhole. In all cases the sunspots could have been visible.

Table 1.

The pinholes meridian lines operating in the churches before the invention of the telescope were in Florence, Bologna (no more existant) and in Vatican. Their parameters are compared with the ones of St. Maria degli Angeli in 1999 and since 2018, after the restauration of the pinhole. In all cases the sunspots could have been visible.

| Meridian line / date |

Pinhole diameter/height |

Visibility of the sunspots |

| S. Maria del Fiore (1475) |

50/90000 = 1/1800 |

Yes, only in June-July |

| St. Petronio (Danti, 1577) |

Not known |

Reliably Yes |

| Torre dei Venti (1580) |

14/5180 = 1/370 |

Yes (>30” or 400 MH) |

| St. Petronio (Cassini, 1655) |

27/27000 = 1/1000 |

Yes |

| St. Maria degli Angeli (1999) |

40/20353 = 1/500 |

Yes (>25” or 300 MH) |

| St. Maria degli Angeli (2018) |

10-23/20353 = 1-2.3/2000 |

Yes |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).