1. Introduction

The Clementine Gnomon is also known as the Meridian Line of St. Maria degli Angeli in Rome, and it was built between 1700 and 1702 under the direction of the astronomer Mons. Francesco Bianchini (1662-1729). The Gnomon was financed by the Cardinal Gian-Francesco Albani before becoming Pope on 23 November 1700, with the name of Clemens XI (1700-1721).

This instrument is a gigantic pinhole camera realized to obtain an unprecedented accuracy in the daily meridian positions of the Sun, in order to measure the length of the tropical year, and the secular variations of the obliquity of the ecliptic. The horizontal pinhole of 25 mm of diameter illuminates nowadays the meridian line.

Bianchini (1703) improved the instrumental performances of the Gnomon, with respect to the Heliometer of Bologna, allowing the observations of the brighter stars from the meridian line, in order to obtain the sidereal time through their meridian transits, and making a very stable pinhole for the centuries to come (Heilbron, 1999).

1.1. Historical Context: Churches as Observatories

The previous instruments dedicated to measure the Earth’s orbit and obliquity are in the Cathedral of Florence realized by Toscanelli in 1475

1 and in Bologna in the Basilica of St. Petronio. Egnazio Danti made a first version in 1577; Cassini re-traced completely it in 1655 and restaured it in 1695 (Cassini, 1695).

Bianchini studied in Bologna and in Padova. He become in contact with the most prominent scholars of his time (Heilbron, 2022). With the Clementine Gnomon, Bianchini realized the most advanced instrument of his times, to assess the bases of the Gregorian Reformation of the Calendar in 1582. Newton invited Bianchini to join the Royal Society of London as a foreign fellow. The Clementine Gnomon remained, after Bianchini, a reference instrument studied also by Celsius in 1734 and Boscovich in 1750 (Heilbron, 1999). With the meridian line created by De Cesaris in 1782 in the Duomo of Milan the accuracy of the meridian’s azimuth reached 6”, but the astrometric purposes were no more in the scopes of its construction (Ferrari da Passano, Monti and Mussio, 1977). The meridian in the Cathedral of Palermo created by Piazzi in 1803, was devoted to the local noon’s determination for the Angelus’ prayer, and for public timing, without any more astrometric scopes. The local noon gradually ceased to be relevant for public life, beyond religion, as the World time zones and their mean time become in official use after the conference of Washington of 1884. The function of civil time keeping of the Clementine Gnomon ceased in 1846, when the Collegio Romano Observatory took this service: a big ball left falling along a tube, on top of St. Ignatius’ Church, was the visual signal for shooting the cannon on Castel St. Angelo (Sigismondi, 2009 and 2021).

1.2. Secular Variations of the Solar Parameters in Maunder Minimum

Since the antiquity, the Sun was considered as a celestial spherical body of fixed radius and given orbital motion. The variation of the distance with the Earth would change its angular diameter, according to the form and the center of its orbit. Cassini realized the meridian line of Bologna to measure the solar angular diameter along the year and the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit. The present study and the one of Tovar, et al. (2021) aim to find secular variations in the intrinsic radius of the Sun.

The number of sunspots was the first solar parameter to be identified as variable in the time, since the first observations of Galileo (1613), and H. Schwabe (1836) found their 10-year regularity, after found as 11-year cycle. E. Maunder (1894, 1922) and his wife discovered in the archive data a long period almost without spots, that nowadays is called Maunder minimum. Finally other great solar minima (Usoskin, 2023) were discovered and J. Eddy proposed to dedicate these periods to Oort (period around 1040) and Spörer (in 15th century) (Whitehouse, 2007).

Carrasco and Vaquero (2016) studied the rotation’s changes of the Sun during Maunder minimum, from the correspondence of John Flamsteed. The aspect of the sunspots at the beginning of the minimum as observed by Hevelius was analyzed by Carrasco, Vaquero, Gallego, et al., (2019), the ratio umbra/penumbra during the Maunder minimum (Carrasco, Garcia-Romero, Vaquero, et al., 2018) and the observations with the naked eye in the same period (Carrasco, Gallego, Arlt, et al., 2020).

Several authors (e.g., Shapley (Ed.), 1963; CNES Toulouse, (1980); Penza, et al. (2022) studied the variations of the solar irradiance correlated with the little ice age, occurred in 17th and 18th centuries.

1.3. The Observations Made in Bologna at the Meridian Line of Cassini

Giandomenico Cassini (1625-1712) and his collaborators monitored since 1655 the solar diameter. Eustachio Manfredi (Manfredi, 1736) reported their and his observations. They encompass also the period of the solar Maunder minimum (1645-1715). Manfredi reduced all the data for the “penumbra” (the pinhole size), and refraction effects. Tovar et al. (2021) analyzed these data concluding that the data of 1655-1715 in the grand sunspots’ minimum, and the ones of 1716-1736 immediately after, are compatible with the same solar diameter, within 0.6”.

The present study at the Clementine Gnomon in Rome, aims to reproduce the conditions of the solar observations in 1700, in order to understand better the sources of errors and their consequences on the measured solar diameter and their statistics. We offer also to the public debate the very accurate measures of the solar diametermade by Bianchini around the winter solstices of 1701 and 1702 (Bianchini, 1702 and 1703), which are at the end of the Maunder minimum.

2. Structure and Focus of This Article

The historical introduction, is necessary to understand the pinhole astronomy (1.1) made with the meridian lines draft in the churches used as observatories in 17th and 18th centuries for measuring its position and its diameter. The studies on the variations of solar parameters (1.2) and the observations made at the Heliometer of Bologna (1.3) complete the context of the present work. Then (3.) we present the complete re-calibration of the Clementine Gnomon in Rome, used for the modern observations of the Sun (2018-2025) and of the stars (2025). The local seeing (4.1) affects the measures of the meridian lengths of the solar image. Geometrical and environmental factors (4.2) meteorology and reflecting conditions of the marbles near the meridian line are examined (4.3) to understand the observative uncertainties.

The measures of Bianchini in 1701-1702 winter’s solstices are presented in chapter (4.4). In chapter (5.) we introduce the problem of the secular variation of the solar diameter and its detectability. In chapter (6.) the clustered averages of the data of Bologna (1655-1736) are simulated after having duly discussed their sources of errors in longer (6.2) shorter (6.3) and veiled (6.4) images. The data of Rome (1701-1702) and the contemporary ones allow us to make realistic simulations (6.5.) with observational errorbars. The distribution of the differences between two clusters of data (Maunder minimum and after it) is simulated. In chapter (7.) we compare the measures made by Bianchini near the winter solstices of 1701 and 1702, where the relative errors on the meridian diameter are minimal, with the measures made by Sigismondi in 2018-2025. Finally we conclude that our data, which support our simulations, do not meaningfully constrain our current understanding of the Sun’s evolution.

3. The Observational Campaign IGEA-ZIA (2018-2025) at the Clementine Gnomon

C. Sigismondi started on 27 October 2018 an extensive astrometric observational campaign called IGEA, Informatized Geometric Ephemerides for Astrometry with ZIA Zenithal Imaging Analysis in order to obtain accurate local references along the meridian line (Sigismondi, 2022). The meridian measures of the solar diameter have been accompanied with meteorological data (pressure, temperature and humidity) and sky aspect (cloudy, with veils or clear) to understand their contributions to the observed diameter’s length. All the meridian transits have been recorded and they are available on youtube

2.

The daily meridian positions of the solar limbs on the brass line are compared with the ephemerides to disentangle systematics from seeing, meteo and personal equations.

With these premises the nutation and the obliquity variations are measurable all the days of the year (Sullivan, 2016), with a particularly high accuracy around the winter solstice, with a 1.77”/mm scaling at the meridian transit.

Several sunspots during the present XXV solar cycle were visible on the meridian marbles, especially in the winter’s season, when the solar image is as large as hundred times the effective pinhole’s size.

The present pinhole is a cylinder 6 mm thick and 25 mm wide, this reduces the effective pinhole to about 11 mm-meridian- x 23 mm–transverse- in winter time, moving its center up to 7 mm in the meridian direction, periodically, during the year.

Originally in 1702 the pinhole was an horizontal circle 20 mm wide, 1:1000 of its height (Catamo and Lucarini, 20122), realized by Giuseppe Campani (1635-1715), the best lens maker of his times, in a 2 mm-thick bronze plate (Schiavo, 1991).

The present pinhole configuration shows clearly the larger sunspots on the solar image, because the higher space resolution for such lensless telescope (Sigismondi, 2002) is reached. The solar limb darkening convoluted with the pinhole aperture (called penumbra, because from there a part of the sky around the Sun is visible through the pinhole) and the diffraction produces a red rim of the solar image, of 5 mm or 10” width at the winter solstice.

This study was extended to extra-meridian measures in 2024-2025 to verify the observing conditions with solar altitudes down to 20°, as in Bologna during winter solstice, and to strengthen the statistics of our measurements, with tens of measures in a single observing session, instead of the single meridian transit. Over one thousands of observations have been catalogued between meridian and extra-meridian data, along with meteorological data of pressure, temperature and humidity beyond the clouds/clearness of the sky.

4. Observations in Rome: Past and Present

The gigantic dimension of the Clementine Gnomon, up to 50 m of focal length, maximizes the signal (1100 mm at winter’s solstice) to noise (2 mm of image’s turbulent vibration) ratio for the solar image’s measurement.

The central brass meridian line is 30 mm wide. It is inserted in two white marble slabs (910 mm width in total) and in two external yellow marble strips of 224 mm each (see Figure 3). The whole design is symmetrical, to have the possibility to measure the meridian positions of the Sun ±7.5 minutes from the meridian transit.

Originally around the meridian line there was only “cotto” tiles, but in 1750 all the floor of the Basilica was renovated with marbles, and they are different from the yellow of Verona.

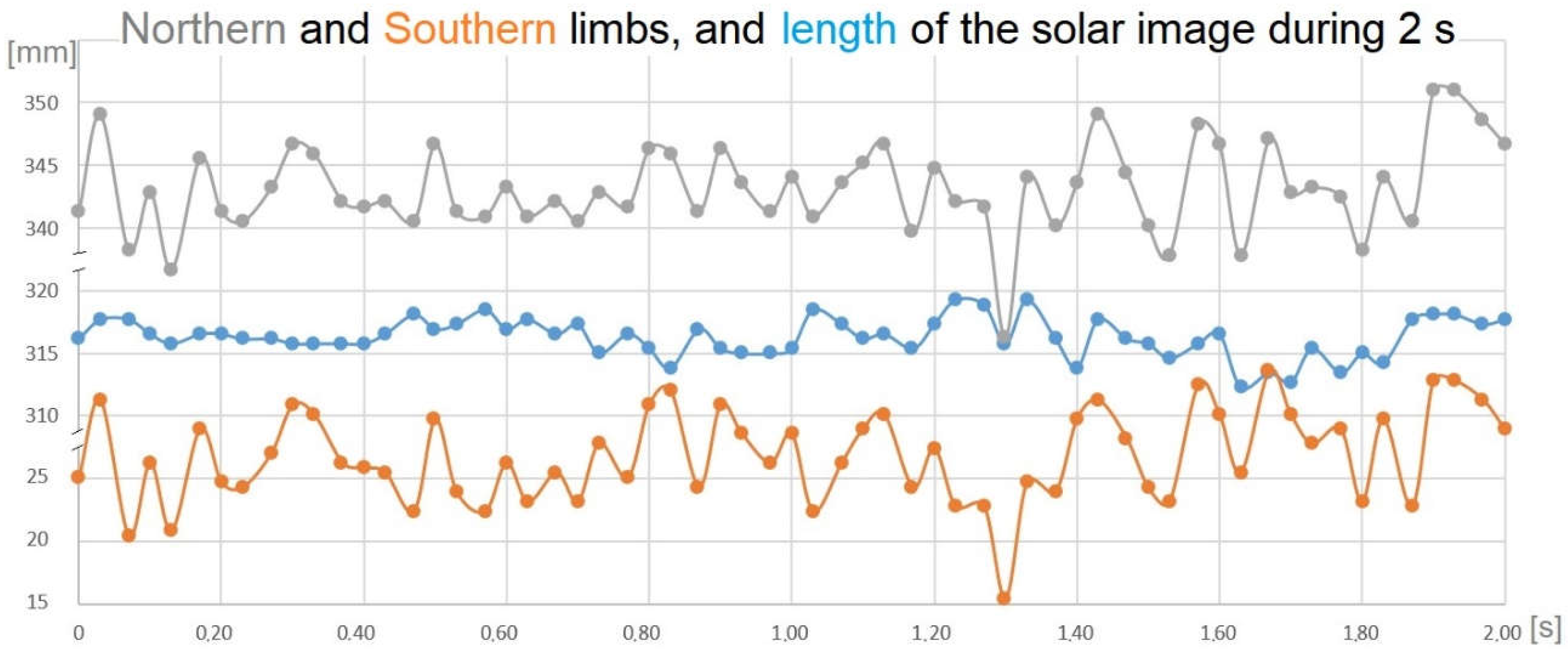

4.1. Turbulence at the Clementine Gnomon

The air turbulence, responsible of the seeing of the solar image in the Basilica of St. Maria degli Angeli, occurs mainly in the first meters just outside the pinhole, since the image rapidly shakes all at once, and this is to expect when hot bubbles move close to the pinhole, on the line of sight of the Sun

3.

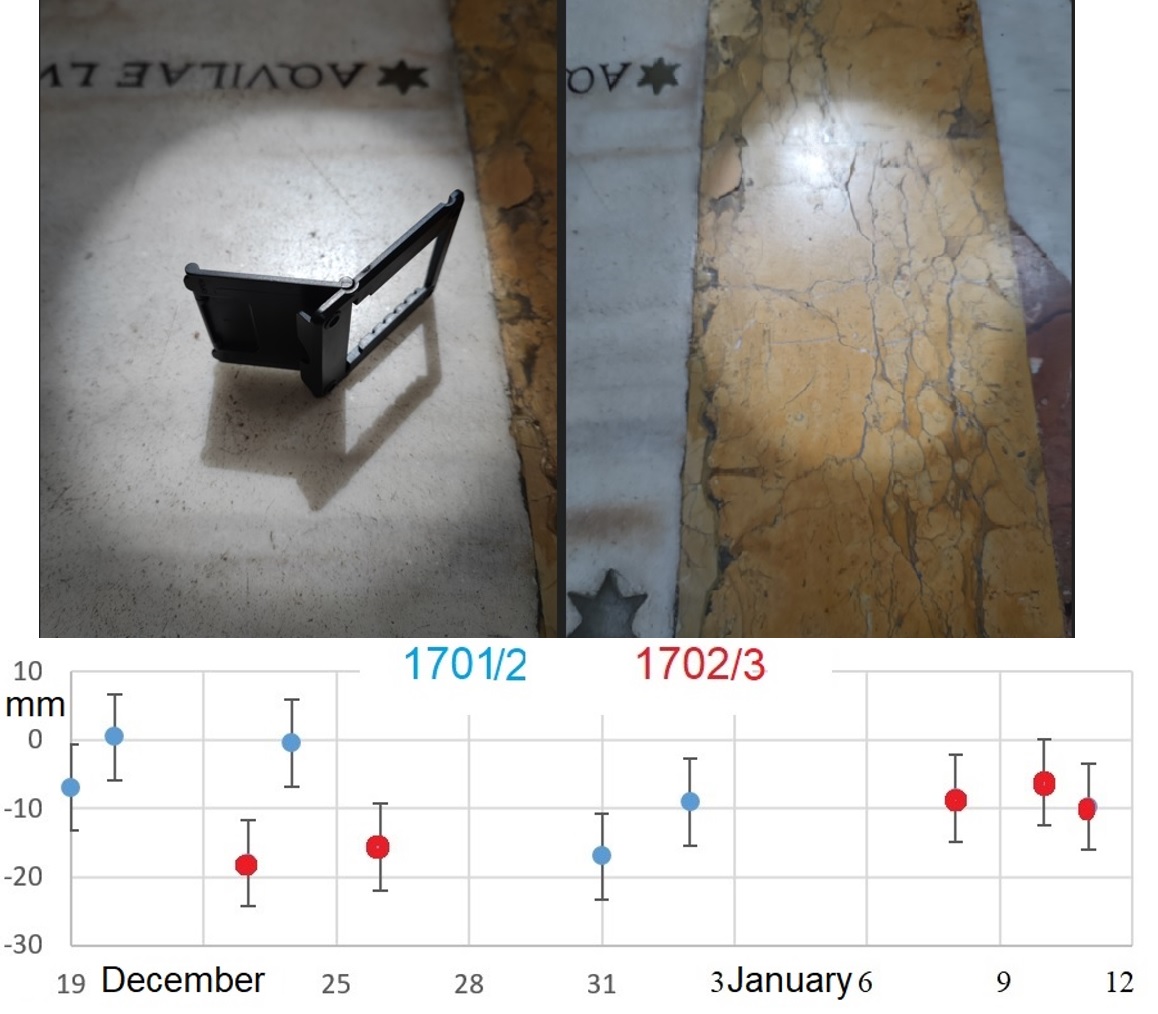

Figure 1.

Position of the Northern and Southern limbs in 61 consecutive frames separated by 1/30 s each, in a 2.00-seconds video on 29 March 2022 at 13:20:29-31. The length of the image has a spread ±1.5 mm (corresponding to a 9” seeing), much lower than the limbs spreading in phase of ±3.6 mm (22” of seeing). The average length of the image is 316.3 mm from one to another inflexion point, and it corresponds to 1922” of angular dimension (ephemerides). The positions are defined by the inflexion points of the light curves for each frame, along the meridian direction. The camera is a Samsung SM-J500FN in VGA 640x480 pixels in automatic mode.

Figure 1.

Position of the Northern and Southern limbs in 61 consecutive frames separated by 1/30 s each, in a 2.00-seconds video on 29 March 2022 at 13:20:29-31. The length of the image has a spread ±1.5 mm (corresponding to a 9” seeing), much lower than the limbs spreading in phase of ±3.6 mm (22” of seeing). The average length of the image is 316.3 mm from one to another inflexion point, and it corresponds to 1922” of angular dimension (ephemerides). The positions are defined by the inflexion points of the light curves for each frame, along the meridian direction. The camera is a Samsung SM-J500FN in VGA 640x480 pixels in automatic mode.

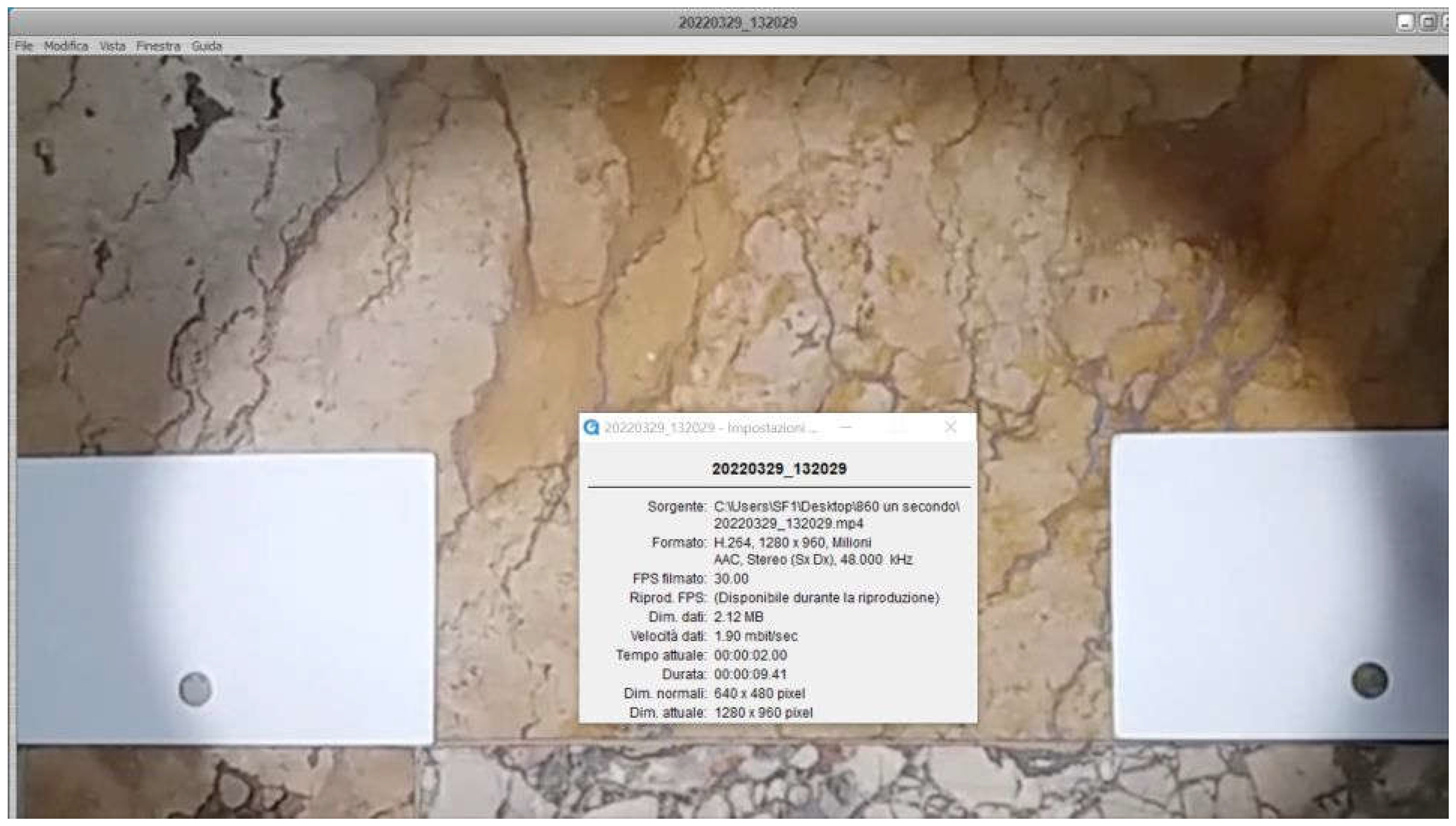

Figure 2.

The 2.00 s frame of the video analyzed in Figure 2. The image was on the yellow marble “Giallo di Verona” after the meridian line. The white cards are posed parallel to the meridian line: on them we found the inflexion points of the two meridian solar limbs.

Figure 2.

The 2.00 s frame of the video analyzed in Figure 2. The image was on the yellow marble “Giallo di Verona” after the meridian line. The white cards are posed parallel to the meridian line: on them we found the inflexion points of the two meridian solar limbs.

The observations in 17th-18th centuries were visual, and to understand the effect of the seeing we needed many extra-meridian measures. A single position has been marked with a pencil on the marble. Each observation mediates necessarily the perceived positions, but this is not simultaneous for both limbs, as in the video, then this may change the measured length of the image. We could evaluate in different seasons and with different weathers the dispersions of the main axis lengths of the images: they are similar to the one experienced by Bianchini in Rome and by Cassini and collaborators in Bologna.

4.2. Measuring the Solar Meridian Diameter in St. Maria Degli Angeli

The solar diameter is measured by measuring the length between the two meridian limbs North and South; the dimensions of the image are reduced with respect to the maximum theoretical light extension because of

1. Signal to noise ratio reduced by ambient light.

2. Solar limb darkening.

3. Cylinder effect, due to the pinhole vertical thickness.

4. The light reflected inside the marble tends to enlarge the image toward summer time.

The meridian diameter is then systematically 8 mm less than the ephemerides near the winter solstices (2018-2024) and it becomes 4 mm less at half-meridian line.

Once identified this systematic difference, a meteorological fluctuation of ±1.5 mm may appear as the meteo departs from STP (15°C, 1013 hPa): approximately 1 mm/10°C and 1 mm/10 hPa near the winter solstice, the effect is less evident at lower focal lengths (distance pinhole-image) i.e., toward summer time.

The motion of the image is perpendicular to the meridian line. This allows to detect very precisely the limbs, if a fit over five positions per limb (pencil’s signs) is done, and the center of the image can be located with a nominal precision better than 0.5 mm.

A routine written in Excel permit to compare the observed data with the predicted ones by the ephemerides. If the differences on the positions of the center exceed 2 mm there is a problem of “zero”, i.e., on the transport of the reference with respect we measure the positions.

The meridian line is an historical monument that has to be preserved, so we cannot leave permanent signs on it, or objects, then the references are made with respect some signs already present on the line, namely the junctions between consecutive brass sections, and the distances from them reach up to 7 m in some point of the meridian line.

Once the “zero” problems are solved and the center of the solar image is within 2 mm from the ephemerides, the same procedure is applied to the two limbs. The ideal situation is when the two limbs are symmetrically shifted from the ones predicted by the ephemerides: the image is not deformed by the light reflected into the marble (Figure 3 left).

Figure 3.

The Sun with veiled sky on 9 April 2025. The light passing below the dark obstacle (left) is reflected inside the white marble; the image on the yellow marble of Verona (right). The veiled sky showed a 22° halo around the Sun, that day.

Figure 3.

The Sun with veiled sky on 9 April 2025. The light passing below the dark obstacle (left) is reflected inside the white marble; the image on the yellow marble of Verona (right). The veiled sky showed a 22° halo around the Sun, that day.

When the asymmetry exceeds the 2 mm further checks are to be done, but in general the check on the center is enough. The reflection inside the marble is a non-symmetrical effect, because it is sensitive to the direction of the light, and on the Northern limb (up in two parts of Figure 3) the light spreads into the solar image, while in the Southern limb it spreads out, enlarging the measured diameter.

4.3. Images with Tiny Clouds and on Different Marbles

The measured length of the solar diameter along the meridian line have been found from 0 (thin clouds with halo) to 9 mm shorter than the ephemerides, in all the cases examined.

The study under different cloud coverages (Figure 4) and different floor reflections (Figures 3, 5 and 6) has been conducted in order to understand what could have been the source errors in 17th and 18th centuries observations made in Bologna and in Rome.

Bianchini did choose the white marble Imetto for the right and left spaces, both of width 455 mm around the meridian line. They have an optimal reflectance, superior to the rose marble in Bologna, much similar to some of the marbles found in the floor of the Basilica, realized for the Jubilee of 1750 by Luigi Vanvitelli upon the will of the pope Benedict XIV. The selection of the marble made by Bianchini was one of the significant improvements with respect to the Cassini meridian line of Bologna; the others were the observability of the stars through the meridian, contemporarily to the Sun, and the great stability of the pinhole, carved in the Diocletian’s walls, stabilized after 1400 years. Bianchini provided the meridian line of a hydraulic circuit to verify its horizontality along all 45 m of length. For each observation, he darkened the Basilica with tents applied to the windows from outside. This was not possible in St. Petronio Basilica in Bologna.

Bianchini then tried to observe with optimal signal-to-noise conditions, so he could observe both perpendicularly to the limbs (ZIA conditions) and along the inclined line of sight to get the maximum luminosity of the image (incidence angle = reflected angle of the rays) exploiting the reflection’s law. In both cases, the observations were prepared some hours before the meridian transit, a time necessary for the total obscuration of the Basilica.

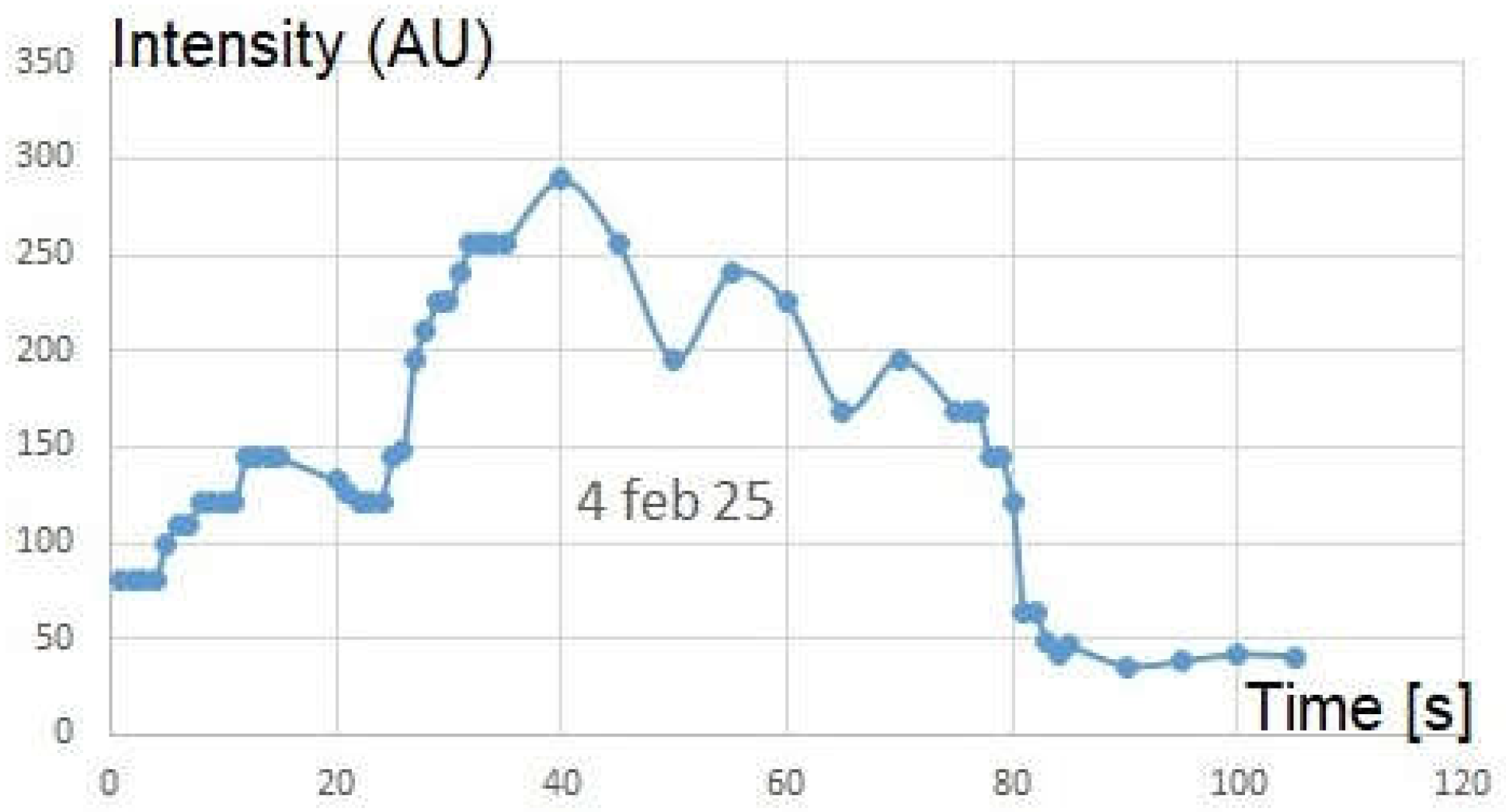

Figure 4.

Photometry during the solar transit of 4 February 2025

4. The contrast of the image changes slightly during the transit, determining uncertainties on limbs’ positions under tiny clouds (invisible to our eyes before/after the transit) or full sunlight.

Figure 4.

Photometry during the solar transit of 4 February 2025

4. The contrast of the image changes slightly during the transit, determining uncertainties on limbs’ positions under tiny clouds (invisible to our eyes before/after the transit) or full sunlight.

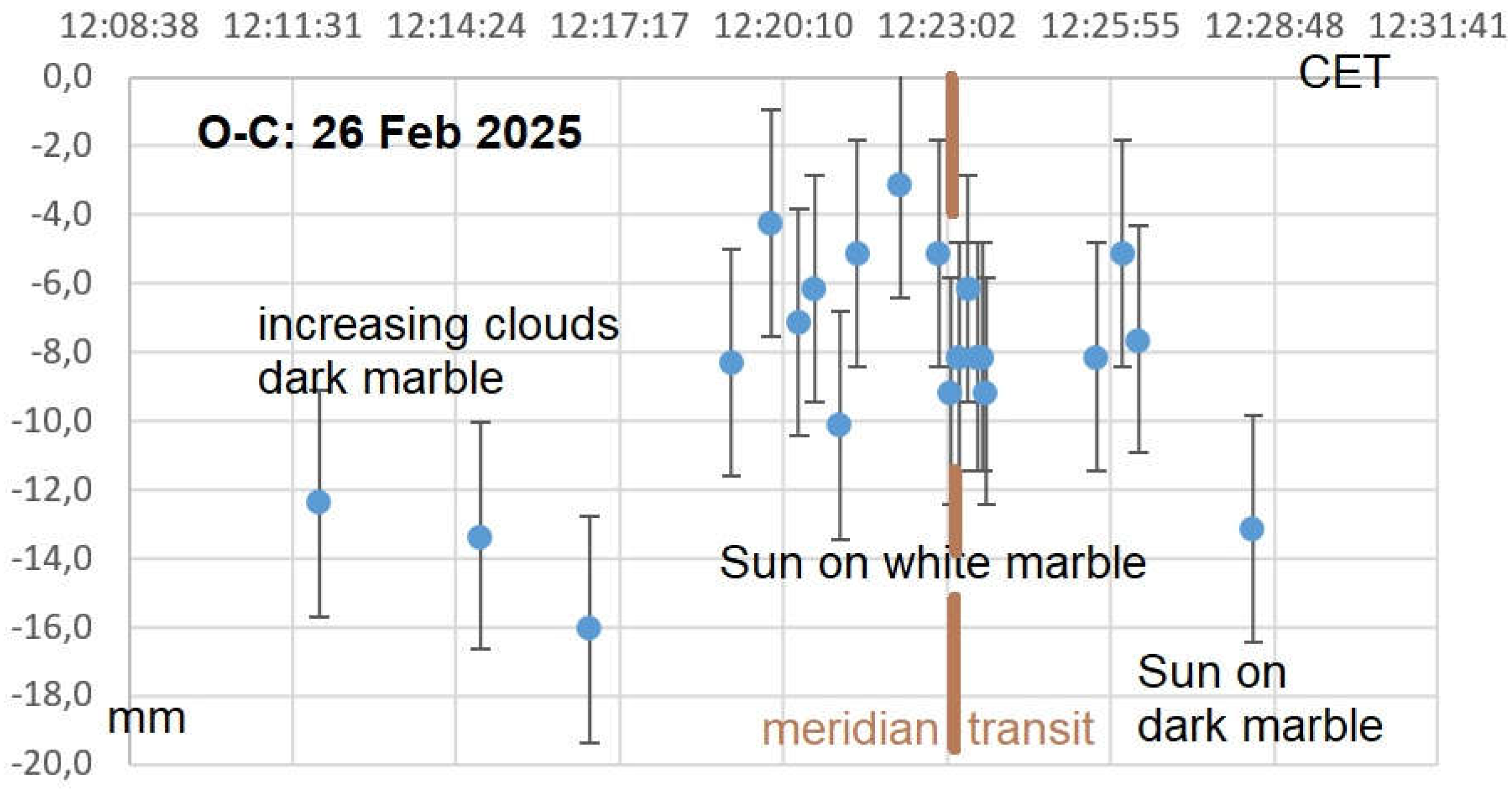

Figure 5.

Measured diameters (Observed-Calculated) in different meteorological conditions and on differently reflecting marbles in St. Maria degli Angeli (26 February 2025, video).

Figure 5.

Measured diameters (Observed-Calculated) in different meteorological conditions and on differently reflecting marbles in St. Maria degli Angeli (26 February 2025, video).

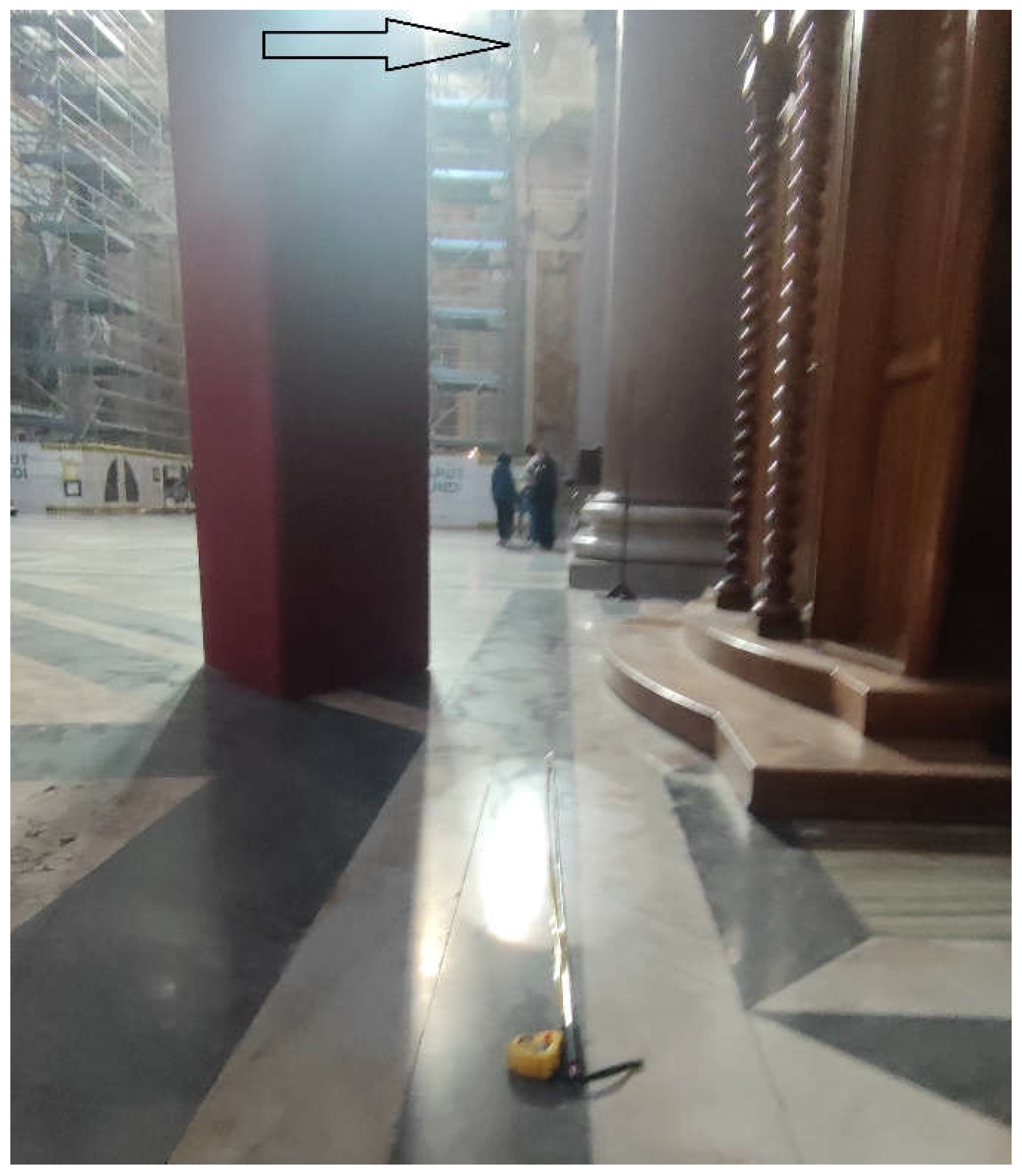

Figure 6.

The red-ringed image of the Sun at 9:43:56 of 11 February 2025. Its length is 1248 mm. We measured solar images with the Sun as low as 20° as in Bologna’s winter solstices, and up to 1.6 m long. The black arrow shows the pinhole. A movable screen was necessary to see the image on the floor with that ambient light and such low contrast.

Figure 6.

The red-ringed image of the Sun at 9:43:56 of 11 February 2025. Its length is 1248 mm. We measured solar images with the Sun as low as 20° as in Bologna’s winter solstices, and up to 1.6 m long. The black arrow shows the pinhole. A movable screen was necessary to see the image on the floor with that ambient light and such low contrast.

4.4. Solar Diameters in 1701 and 1702

Francesco Bianchini around 1701-1702 winter solstices made 11 measures at the Clementine Gnomon under good weather’s conditions. Ten of them are represented in

Figure 5, one was rejected

5. The mean value of the difference between Observed and Calculated diameter (ephemerides with 1920” solar angular diameter at 1AU) is O-C=-9 mm.

The winter solstice’s data taken near the maximum of the XXV solar cycle (2023-2024) are compared with ten winter solstice’s data of Francesco Bianchini (1701-1702) represented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Ten observations of the solar diameter measured by Bianchini near the winter solstices of 1701 and 1702. The solar diameters are -9±6 mm smaller than the ones calculated with the ephemerides (Espenak, 2025). The standard deviation σ≈6 mm has been assumed as the accuracy of a single measurement and the average m=-9 mm is the systematic difference with respect to the ephemerides for 1701/2. Both the average -9 mm and the standard deviation 6 mm are similar to the measures made in 2018-2025.

Figure 7.

Ten observations of the solar diameter measured by Bianchini near the winter solstices of 1701 and 1702. The solar diameters are -9±6 mm smaller than the ones calculated with the ephemerides (Espenak, 2025). The standard deviation σ≈6 mm has been assumed as the accuracy of a single measurement and the average m=-9 mm is the systematic difference with respect to the ephemerides for 1701/2. Both the average -9 mm and the standard deviation 6 mm are similar to the measures made in 2018-2025.

5. Studying Solar Diameter Variations During the Maunder Minimum

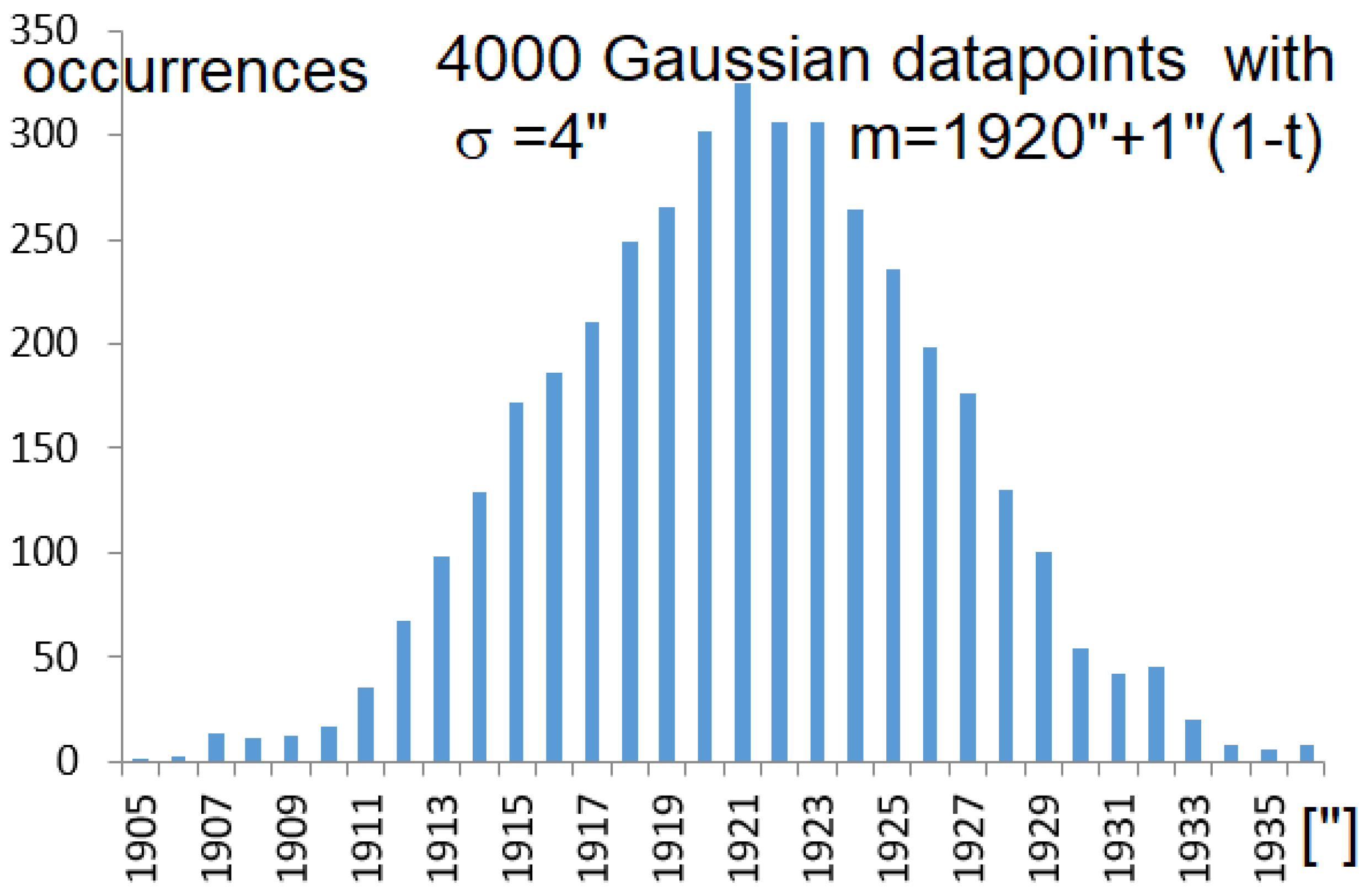

We realized simulations with a gradual change of 1” in solar diameter along the years (1655-1736) when the Maunder minimum occurred. We added a realistic Gaussian noise to each data of average 0” and ±4” of standard deviation (±2 mm at the ground at winter solstice). The same timespan is covered by the 4000 observations made in Bologna and considered in Tovar et al. (2021).

The changes in the solar angular diameter, if they occur, are expected to be of the order of ≤ 1”/century. All instrumental e.g., temperature variating the focal length (SDS experiment, Egidi et al. 2006) and experimental effects e.g., refraction (Corbard et al. 2019) or black drop effect in planetary transits (Pasachoff, 2002) have to be excluded.

The most recent experimental data on the solar angular radius have been obtained with ground-based and satellite experiments, as the Picard satellite with its twin telescope at ground (θr

☉=959.78”±0.19” Meftah et al., 2014). Recent Baily’s beads analyses in solar eclipses yielded values of the solar radius (θr

☉=959.99”±0.06” Lamy et al. 2015, θr

☉=959.95”±0.05” Quaglia et al. 2021). These values of θr

☉ are up to 0.4” larger

6 than the standard value of the solar radius at 1AU: θr

☉=959.63”±0.02” (Auwers, 1891).

6. Detecting Solar Diameter Changes form Averages of Clusters of Data?

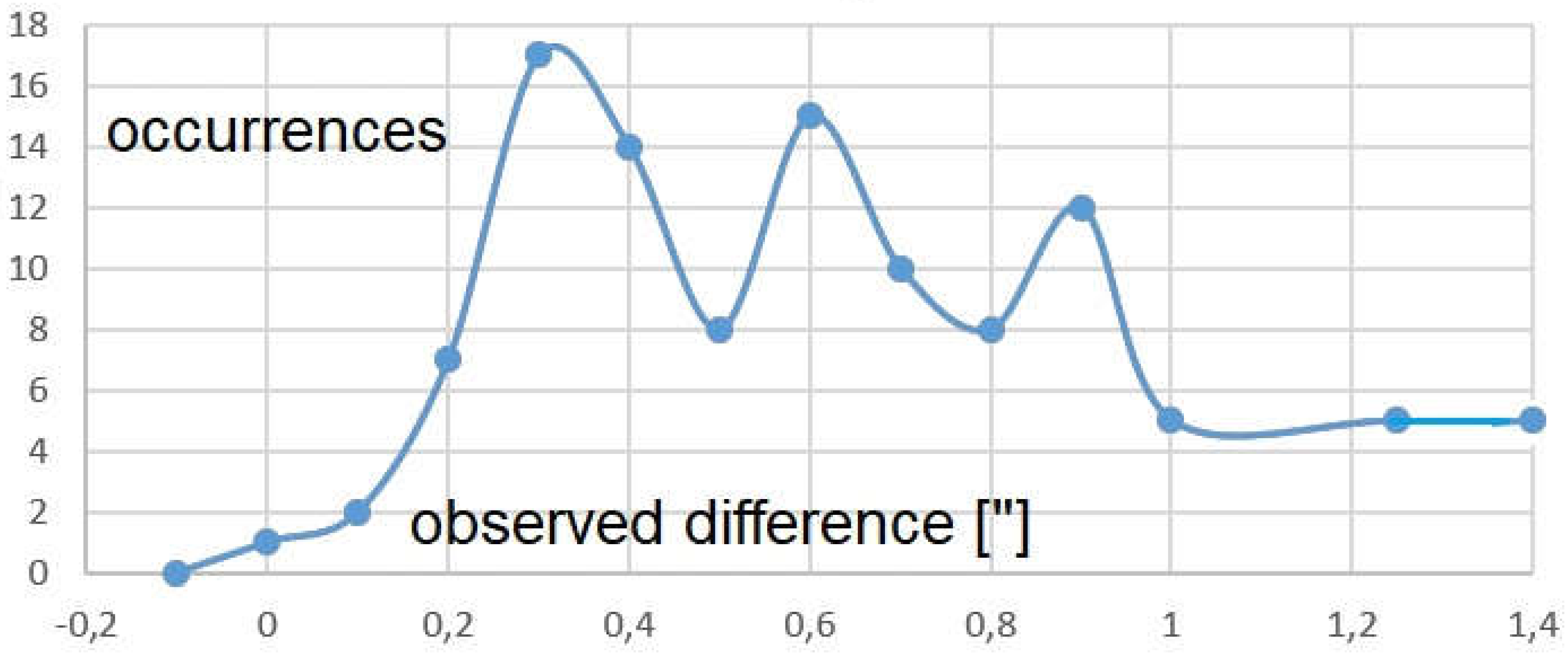

The simulations of the observations are made with a realistic and very optimistic errorbars of ±2 mm (±4”) at the winter solstice. We realized 4000 data, clustering ¾ of them as the period (1655-1715) to calculate the first average, and the remaining ¼ representing the period (1716-1736) and to calculate the second average. These average –without errorbars- are different by Δ=0.55”. Adding errorbars of ±4 mm (±8”) for each data, this difference becomes more noisy, Δ=0.5”±0.3” (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The solar diameter changing from 1920” to 1921” from t=[0,1], observed with a 4” random Gaussian uncertainty. The two clusters are 1-3000 and 3001-4000 and represent the years 1655-1715 and 1715-1736. They have different averages, separated by about Δ≈0.5”±0.3” while the simulated one is Δ=0.55”, and similar standard deviation σ=4”.

Figure 8.

The solar diameter changing from 1920” to 1921” from t=[0,1], observed with a 4” random Gaussian uncertainty. The two clusters are 1-3000 and 3001-4000 and represent the years 1655-1715 and 1715-1736. They have different averages, separated by about Δ≈0.5”±0.3” while the simulated one is Δ=0.55”, and similar standard deviation σ=4”.

The simulation to be realistic, and to cover all the year, should include also the errorbars for spring, fall and summer, and the cases of thin clouds, which enlarge the perceived diameter.

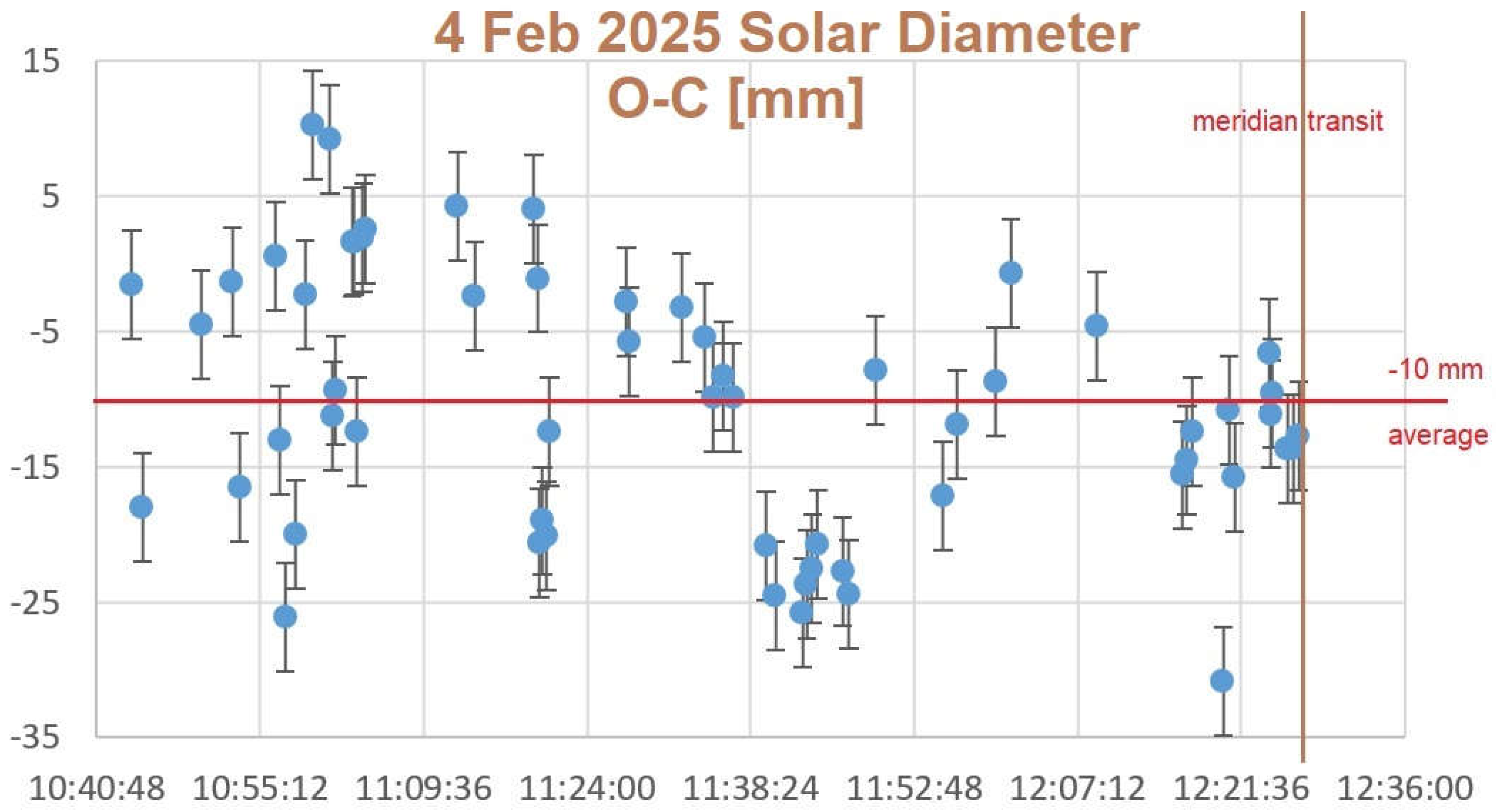

Figure 9.

The measures (extra- and on-meridian line) of 4 February 2025 compared to their ephemerides: there is a systematic difference with the solar diameter underestimated by -10 mm (personal/environmental equation). It corresponds to 20”. Bianchini (Figure 7) underestimated of -9 mm in 1701-1703, or 18”.

Figure 9.

The measures (extra- and on-meridian line) of 4 February 2025 compared to their ephemerides: there is a systematic difference with the solar diameter underestimated by -10 mm (personal/environmental equation). It corresponds to 20”. Bianchini (Figure 7) underestimated of -9 mm in 1701-1703, or 18”.

6.1. Real Data and Simulations with Realistic Errorbars

Presently (2025) the solar diameter corresponds also to the maximum of activity of the cycle XXV. Francesco Bianchini measured the Sun at the end of the Maunder Minimum in 1701-1702, near the two winter solstices. He underestimated the diameter of 9±6 mm. The standard deviation of ±6 mm is equivalent to ±12” in winter solstice.

C. Sigismondi measured the major axis of the solar image, which is the meridian diameter on the Clementine line during the IGEA-ZIA campaign (2018-2024). With the extra-meridian extension of the campaign in 2025 he measured the major axis of many images produced by the pinhole out of the meridian line.

6.2. Measures at the Winter Solstice (Longer Images)

Several diameters measured on the meridian line and off-meridian, accompanied by meteorological data, show an average underestimate of 12±8 mm (Figure 11), similar to the one of Bianchini’s data.

These modern observations have permitted to evaluate realistically the errorbars of Bianchini (±6 mm or ±12”), and the ones of Cassini and Manfredi as ranging around ±16” (±8 mm) for the winter’s solstice data.

Moreover the systematicity of the underestimation of the diameter has been found similar for Bianchini (-9 mm) and for Sigismondi (-12 mm) at the same instrument in the same period of the year, which is always the winter solstice.

6.3. Measures with Shorter Images

The value of the errorbar in arcseconds increases when we deal with spring and summer data: the errorbar increases to ±18” at 1/3 of the length of the meridian line

7, to reach the maximum value at the summer solstice. The measures made far from the winter solstice are affected by definitely larger errorbars, as big as five times for the summer solstice. Then an optimistic and average errorbar for the whole year is to be considered as ±15”, and this applies only for perfect ideal measurements.

The underestimation of the diameter diminishes in length, toward the summer solstice, but the scale arcsec/mm increases inversely to the focal length (distance pinhole-image) and in dependence on the inclination of the solar rays, attaining 5 times the winter’s values. Moreover, there is the effect of image’s spread inside the translucent marble (Figure 3 left part) which determines an increase of the diameter, which is seasonal: in summer, the image is more luminous.

6.4. Measures with Thin Clouds’ Veils

If we consider that thin clouds may enlarge the perceived diameter of about 20”, and that cloudy measure, not excluded as “outlier”, affects the final average up to 20”/N.

Not all the “halo cases” (sole languido) may have been in the 400 outliers mentioned in Tovar et al. (2021).

Figure 10.

The Sun on 9 (left) and 11 (right) April 2025, with diameters respectively -0.1±2.5 mm (-0.7”±17”) and -2.1±2.1 mm (-15”±15”), with a scale 7”/mm. The photo have been taken outside of St. Maria degli Angeli, few minutes before the meridian transit.

Figure 10.

The Sun on 9 (left) and 11 (right) April 2025, with diameters respectively -0.1±2.5 mm (-0.7”±17”) and -2.1±2.1 mm (-15”±15”), with a scale 7”/mm. The photo have been taken outside of St. Maria degli Angeli, few minutes before the meridian transit.

6.5. Simulations

As a consequence of these experiments, we can attribute realistic errorbars to the 17th-18th century measures of the solar diameter made with pinhole-meridian lines. Thus we simulated a set of 4000 data of solar diameters, divided into two clusters corresponding to the years 1655-1715 and 1715-1736, with a slow secular variation (≤ 1”/cy) of the solar diameter. The slow positive variation from the Maunder minimum to its end and 20 year beyond (+1”) is chosen according to the Secchi-Rosa law (Secchi and Rosa, 1874) which anticorrelated the maximum of the solar activity cycle with the minimum diameter measured. The verification of this law continued to inspire the experiments on the solar diameter variations realized in the last years as SDS, Egidi et al. (2006) and Picard (Corbard, et al. (2014).

The averages of the two clusters are statistically different notwithstanding the errorbars of ±4”: their difference is comparable with the standard deviation of the measures.

The simulations of Gaussian errorbars applied to slowly variating solar diameters during the 81 years encompassing the Maunder miminum and the two decades after, show the possibility to compare the averaged solar diameter of the two clusters within a statistical uncertainty of ±0.3”. Depending on the particular dataset, once assumed uniform datapoints along the years, only on 53% of the cases a difference of 0.55” can be detected by analyzing the clusters’ averages. If the solar diameter would have changed for a smaller amount (0.2”) over such long period, the statistical uncertainty is too large to assess that the diameter is not changed during the total period (Figure 13).

Figure 11.

The simulated differences (100 times) between the 3000 averaged solar diameters in the Maunder minimum and 1000 after. The expected value of the difference in the simulations is 0.55”, and it has repeated 100 times with a -very low- Gaussian noise of 8” applied to the single measures. The standard deviation of the averaged differences is 0.3”. In 26% of the cases the difference is ≤0.3”, giving a 100% of uncertainty. In 53% of the cases the difference corresponds to the theoretical one 0.5”±0.3” within the statistical errorbar, and for the last 21% the difference is >0.8”.

Figure 11.

The simulated differences (100 times) between the 3000 averaged solar diameters in the Maunder minimum and 1000 after. The expected value of the difference in the simulations is 0.55”, and it has repeated 100 times with a -very low- Gaussian noise of 8” applied to the single measures. The standard deviation of the averaged differences is 0.3”. In 26% of the cases the difference is ≤0.3”, giving a 100% of uncertainty. In 53% of the cases the difference corresponds to the theoretical one 0.5”±0.3” within the statistical errorbar, and for the last 21% the difference is >0.8”.

7. Comparison Between Bianchini (1702) and Present Data (2018-2025)

The measured solar meridian diameters of Bianchini near the end of the solar Maunder minimum (winters 1701-1702) are -9±6 mm shorter than the ephemerides, calculated with the solar standard diameter of 1919.63”, here assumed as 1920” (Lamy et al. 2015).

The corresponding dates around the winter’s solstices from 2018 to 2024 (Figure 12) yielded a meridian solar diameter -12±8 mm, measured by C. Sigismondi during the IGEA-ZIA campaign. The slightly larger statistical uncertainty is due to having included days with some clouds or veils, while Bianchini observed only with very good conditions.

Figure 12.

Seven solstices, 61 data in total. Blue: 2018-2021, Red: 2022-2024. Only the difference with respect to the ephemerides Observed-Calculated “O-C” is represented in mm.

Figure 12.

Seven solstices, 61 data in total. Blue: 2018-2021, Red: 2022-2024. Only the difference with respect to the ephemerides Observed-Calculated “O-C” is represented in mm.

Assuming a similar personal equation, between Bianchini and Sigismondi, the meridian images have different diameters by 3 mm, since Bianchini underestimated the solar diameter by 9 mm, Sigismondi by 12 mm (

Figure 12). This means having the same systematic error or personal equation in the same geometrical conditions

8. The Sun shrunk by 3 mm or 6”since then, within errorbars of ± 20”.

Normalizing to the standard angular solar diameter and adjusting for the systematic errors the averaged winter solstice data of Bianchini are 1926”±12” while the modern ones are 1920”±16”. A solar diameter’s variation Δθ☉= -6” ± 20” is evidently compatible with zero, but also with the tiny variations claimed with the historical total eclipses. The eclipses of Clavius (occurred in Rome in 1567) or Halley (occurred in England in 1715) analyzed by Eddy and Boornazian (1980) or the one over Manhattan (New York) and Providence occurred in 1925 and analyzed by Dunham et al. (1980) along with the eclipse of 1979.

A single –and very good- measure can be as precise as ±1 mm, or ±2”, if the meteorological conditions are ideal, but in general the statistical fluctuations due to the seeing and to variations of the contrast enlarge the uncertainties (e.g.

, see

Figures 10 and 12): this has been the focus of this study. With these considerations the variation of the solar diameter during 3 ¼ centuries, since the end of the Maunder minimum, cannot be verified better than 10” of accuracy. The data here in comparison are 10 from Bianchini (2 winter solstices) and 61 from Sigismondi (7 winter solstices). We chose the data near the winter solstice for their larger relative and absolute accuracy, given the dimensions of the solar images

9.

8. Conclusions and Perspective

With average errorbars of ±15” along the year to the simulated data reproducing the ones of Manfredi (1736) we compared the first ¾ of the simulated 4000 data and the last ¼ of a slightly variating solar diameter of 1” over the whole period. The differences in their averages are very variable (Figure 11), even without including “halo measures” or “Sole languido”(Figure 10) according to Manfredi, measures with enlarged diameter.

The implicit operation to identify the average with the solar diameter itself, and the variance of the average as the uncertainty on the solar diameter leads to an absurd. Ten thousands of ±20” good observations would produce a ±0.02” knowledge on the solar diameter without need of satellite or telescopes or total eclipse observations. This absurd conclusion would be even stronger if we consider that the typical errorbars of single measures are ranging from ±4” near winter solstices to ±20” in summers. Moreover, the isolated cases of 22° halo around the Sun would increase the final averaged diameters of +20”/N. Repeated simulations with such errorbars show that even clustering the data, their averages does not reflect the slowly variating solar diameter adopted in the simulations, of 1” along the whole time extension of the data.

We conclude that no issues on the solar diameter’s variations between the Maunder minimum and the 20 years immediately following can be found at 0.6” of accuracy even working with cluster averages. For the data analyzed by us, Bianchini 1701-1702 and Sigismondi 2018-2024, all near the winter solstices where the uncertainty is lower, we can give a variation of the solar diameter from θ☉=1926”±12” to θ☉=1920”±18”, which is Δθ☉=-6”±20”, without any possibility to meaningfully constrain our current understanding on the Sun’s evolution.

Author Contributions

C. S. conceived the structure of the paper and wrote it, A. B. contributed to the statistical analysis, G. A. B. to the study of the meridian diameter of the solar image at 30 Hz.

Acknowledgments

Costantino Sigismondi wants to remember gratefully Mons. Giuseppe Blanda (1937-2022), who supported his observations publishing his reports in the official website of the Basilic, and Prof. John L. Heilbron (1934-2023) who inspired the study of the Clementine Gnomon with his masterpiece “The Sun in the Church” (1999). Thanks also to Don Renzo Giuliano, Don Franco Cutrone and Don Pietro Guerini: the rectors of the Basilica of S. Maria degli Angeli since 1999, when these astronomical observations started.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- F. Bianchini, De Nummo et Gnomone Clementino, Romae (1703). https://archive.org/details/dekalendarioetcy00bian/.

- F. Bianchini, Correspondance, 1702 (Biblioteca Vallicelliana, Roma, Fondo Bianchini).

- J. L. Heilbron, The Sun in the Church, Harvard Universtiy Press (1999).

- J. L. Heilbron, The Incomparable Monsignor: Francesco Bianchini’s world of science, history, and court intrigue, Oxford University Press (2022).

- E. Danti, Usus et Tractatio Gnomoni Magni, Bononiae, 1576.

- G. D. Cassini, La meridiana del tempio di S. Petronio: tirata, e preparata per le osseruazioni astronomiche l’anno 1655: riuista, e restaurata l’anno 1695, in Bologna: Per l’erede di Vittorio Benacci (1695). https://archive.org/details/lameridianadelte00cass.

- Carlo Ferrari da Passano, Carlo Monti, Luigi Mussio, La Meridiana Solare del Duomo di Milano, Verifica e Ripristino nell’anno 1976, Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano (1977).

- C. Sigismondi, Lo Gnomone Clementino, Roma (2009), reprinted in Gerbertus 7, 3-80 (2014). Gerbertus7d.

- E. Manfredi, Opera Omnia, 3: De Gnomone Meridiano Bononiensi (Bologna: Lelio dalla Volpe) (1736).

- I. Tovar, A. J. P. Aparicio, V. M. S. Carrasco, et al., Astrophysical J. 912, 122 (2021). Analysis of Solar Diameter Measurements Made at the Basilica of San Petronio during and after the Maunder Minimum - IOPscience. [CrossRef]

- H. Schwabe, Astron. Nach. 44, 21 (1844). 1844AN.....21..233S.

- E. W. Maunder, A prolonged sunspot minimum, Knowledge: An Illustrated Magazine of Science, 17, 173-176 (1894). #247 - Knowledge; a monthly record of science v.17 1894. - Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library.

- E. W. Maunder, The prolonged sunspot minimum, (1645-1715), Journal of the British Astronomical Association, Vol. 32, pp. 140-145 (1922).

- D. Whitehouse, Il Sole Una biografia, Mondadori, Milano (2007).

- V.M.S. Carrasco, M.C. Gallego, R. Arlt and J. M. Vaquero, Astrophys. J. 904, 60 (2020). [CrossRef]

- V.M.S. Carrasco, J. M. Vaquero, M.C. Gallego, et al., Astrophys. J. 886, 18 (2019). [CrossRef]

- V.M.S. Carrasco, J. M. Garcia-Romero, J. M. Vaquero, et al., Astrophys. J. 865, 88 (2018). [CrossRef]

- V.M.S. Carrasco and J. M. Vaquero, Solar Physics 291, 2493 (2016). [CrossRef]

- V. Penza, F. Berrilli, L. Bertello, et al., Astrophys. J. 987, 84 (2022). Total Solar Irradiance during the Last Five Centuries. [CrossRef]

- I.G. Usoskin, A history of solar activity over millennia. Living Rev Sol Phys 20, 2 (2023). [CrossRef]

- H. Shapley (Ed.), Climatic Change. Evidence, Causes, and Effects, Harvard University Press, (1953).

- CNES Toulouse, Sun and Climate (1980). https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb34658419f.

- F. Espenak https://astropixels.com/ephemeris/perap/perap1701.html (visit 13/2/25).

- A. Schiavo, La meridiana di S. Maria degli Angeli, Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato, Roma (1993).

- M. Catamo and Cesare Lucarini, Il Cielo in Basilica, Arpa-Agami, Roma (20122).

- IAU Inter-Division A-G Working Group on Nominal Units for Stellar & Planetary Astronomy, (2015) 1510.07674.

- J. P. Rozelot, A.C. Kosovichev and A. Kilcik, Sun and Geosphere, 13, 63-68 (2018). http://newserver.stil.bas.bg/SUNGEO/00SGArhiv/SG_v13_No1_2018-pp-63-68.pdf.

- P. Lamy, J. Y. Prado, O. Floyd, et al., A Novel Technique for Measuring the Solar Radius from Eclipse Light Curves – Results for 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015. Solar Physics, 290, 2617–2648 (2015). [CrossRef]

- L. Quaglia, J. Irwin, K. Emmanouilidis, and A. Pessi, Astrophys. J. S 256, 36 (2021). (link).

- M. Meftah, T. Corbard, A. Irbah, et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics, 569, A60 (2014). (link).

- A. Auwers, A., “Der Sonnendurchmesser und der Venusdurchmesser nach den Beobachtungen an den Heliometern.

- der deutschen Venus-Expeditionen”, Astronomische Nachrichten, 128, 361 (1891).

- C. Sigismondi, Gerbertus 16, 29 (2022). Gerb-16-2022-Sigismondi-IGEA-ZIA-29-38.pdf.

- A. Egidi, B. Caccin, S. Sofia, et al., High-Precision Measurements of the Solar Diameter and Oblateness by the Solar Disk Sextant (SDS) Experiment. [CrossRef]

- T. Corbard, R. Ikhlef, F. Morand, et al., On the importance of astronomical refraction for modern solar astrometric measurements, Mon. Not. R. Astronon. Soc. (2019). https://watermark.silverchair.com/sty3391.pdf. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Pasachoff, The black drop effect, Sky and Telescope, Vol. 123, No. 5, p.8 (2012). [CrossRef]

- C. Sigismondi, Am. J. of Physics, 70, 1157 (2002).

- C. Sigismondi, Phys. Sci. Forum 2021, 2(1), 49 (2021). [CrossRef]

- W. Sullivan et al., Bulletin-29iii-Sullivan.pdf (2016).

- A. Secchi, and P. Rosa, Observations des diamètres solaires, Comptes Rendus Acad.Sc.Vol. LXXIII and LXXIV,(1874).

- A. Clavius, Commentarius in Sphaeram, Ex officina Dominici Basae Romae (15813).

- E. Halley, Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), Volume 29, pp. 245-262.

- J. Eddy, A. A. Boornazian and C. Clavius, Space and Telescope, 60, 10 (1980).

- D. W. Dunham, S. Sofia and A. Fiala, Science, 210, 1234 (1980).

| 1 |

The gnomon of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

Images recorded from the vertical on 29 March 2022: https://youtu.be/cSTsJVOTy1g. Moreover it is possible to see the superposition of various images in the preceding and procedings limbs, e.g. https://youtu.be/HgCgjM_6uwQ (11 April 2025) especially looking at the projection on paper. |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

One of the observations near the solstices, on 29 December 1701, resulted an outlier, with the measured image 42 mm shorter than the ephemerides, while all other measures are in very good agreement with them, with a systematic reduction of 9 mm. Nevertheless the clear sky conditions of Rome are generally better than “Sole languido” or “Sole languidissimo” (-/+ clouds’ veil) mentioned in the Manfredi’s report (1736). |

| 6 |

The solar radius found in the recent aforementioned experiments are even 0.8” larger than the nominal value obtained by the IAU General Assembly 2015 resolution B3 (IAU, 2015) of R☉=695.66 Mm, based on the Rosseland radius at optical depth τ=2/3 (Rozelot, Kosovichev, Kilcick, 2018). This nominal radius, yields an angular solar radius θr☉=959.17 at 1AU.

It is to note that this nominal value aims to find an agreement between the helioseismological radius and the photometric radii, based on the definition of the solar limb with the inflexion point of the radial photometric profiles. R☉=695.66 Mm is a nominal value to be used, with a fair precision, in the stellar studies, based on nominal solar parameters. But the final scope of this study and the ones about the solar diameter variations, is to better comprehend the physics of the Sun, which may be more complex than expected, being the only one star that we can observe with the greatest resolution, so we have to refer only to the photospheric solar radius and to its variations.

|

| 7 |

On 11 April 2025 the Sun passed at 66 centesimal parts (cp) of the height of the pinhole-20.35 m, at 1/3 of the length of the meridian line, which is 220 cp≈45 m long. |

| 8 |

With the Sun brighter and smaller the difference between observations and ephemerides reduces gradually and around half of the meridian line it is around -3.5 mm (the case of 26 February 2025 with the image 482 mm wide, and the ephemerides predicting 485.5 mm). |

| 9 |

The “inaugural” meridian diameter of 6 October 1702 (Bianchini, 1703) was 415.6 mm long, with the Southern limb coincident with the ephemerides, while the Northern one is -10 mm, so that the diameter resulted -10.6 mm with respect to the ephemerides. Rescaling to the winter solstice this would be -28.6 mm. The choice of the winter’s solstices data is for better relative errors and largest ratio image to penumbra (pinhole size). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).