Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Collection and Its Viability

2.2. Seed Surface Sterilization Method

2.3. Preliminary In Vitro Germination Experiments of T. hirsuta

2.4. Preliminary In Vitro Germination Experiments of T. tartonraira ssp. Tartonraira

2.5. Main Experiments on In Vitro Germination of Both Thymelaea Species

2.6. In Vitro Culture Conditions

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary In Vitro Germination Experiments

3.1.1. T. hirsuta

3.1.2. T. tartonraira ssp. tartonraira

3.2. Main In Vitro Germination Experiments

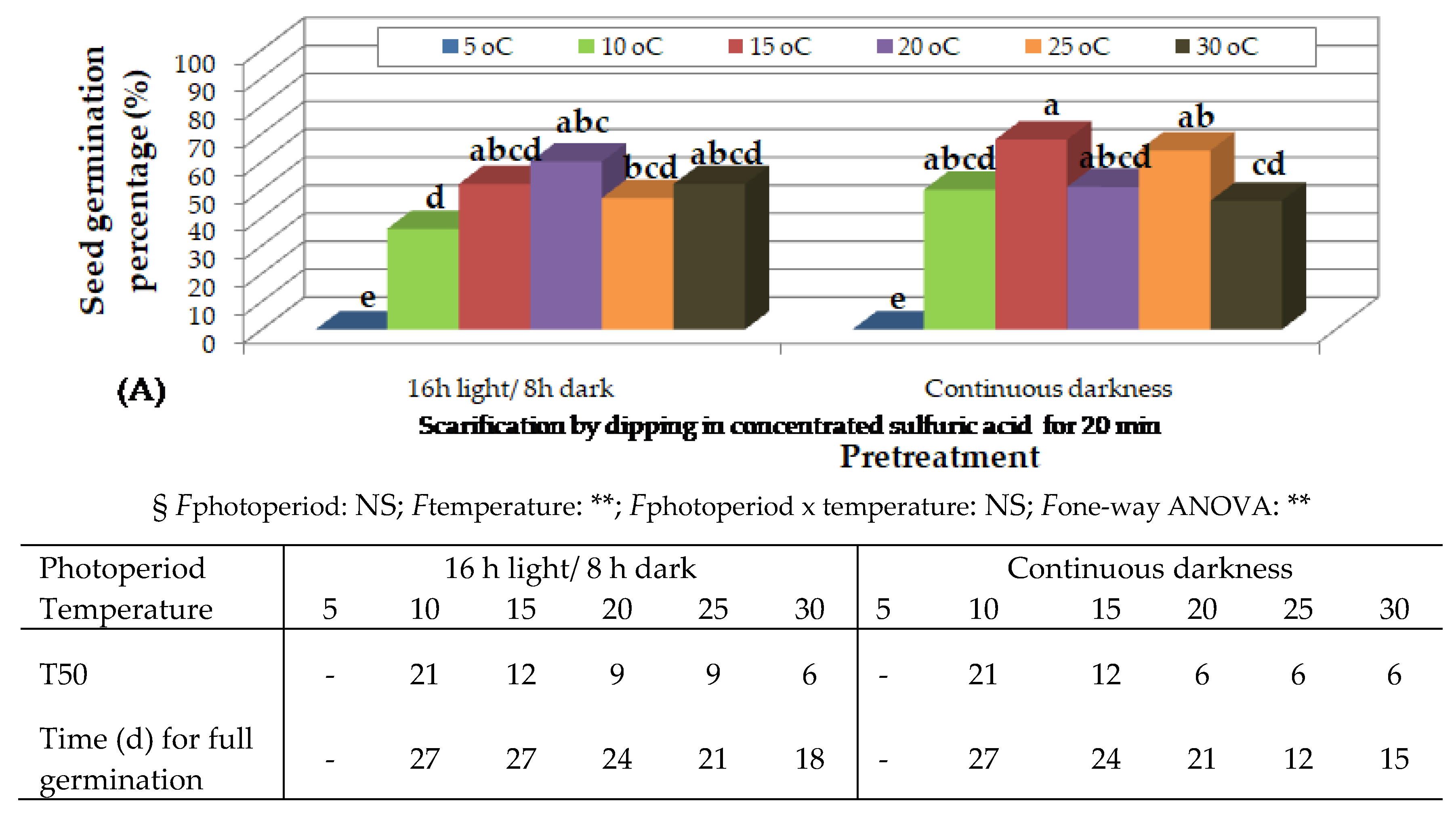

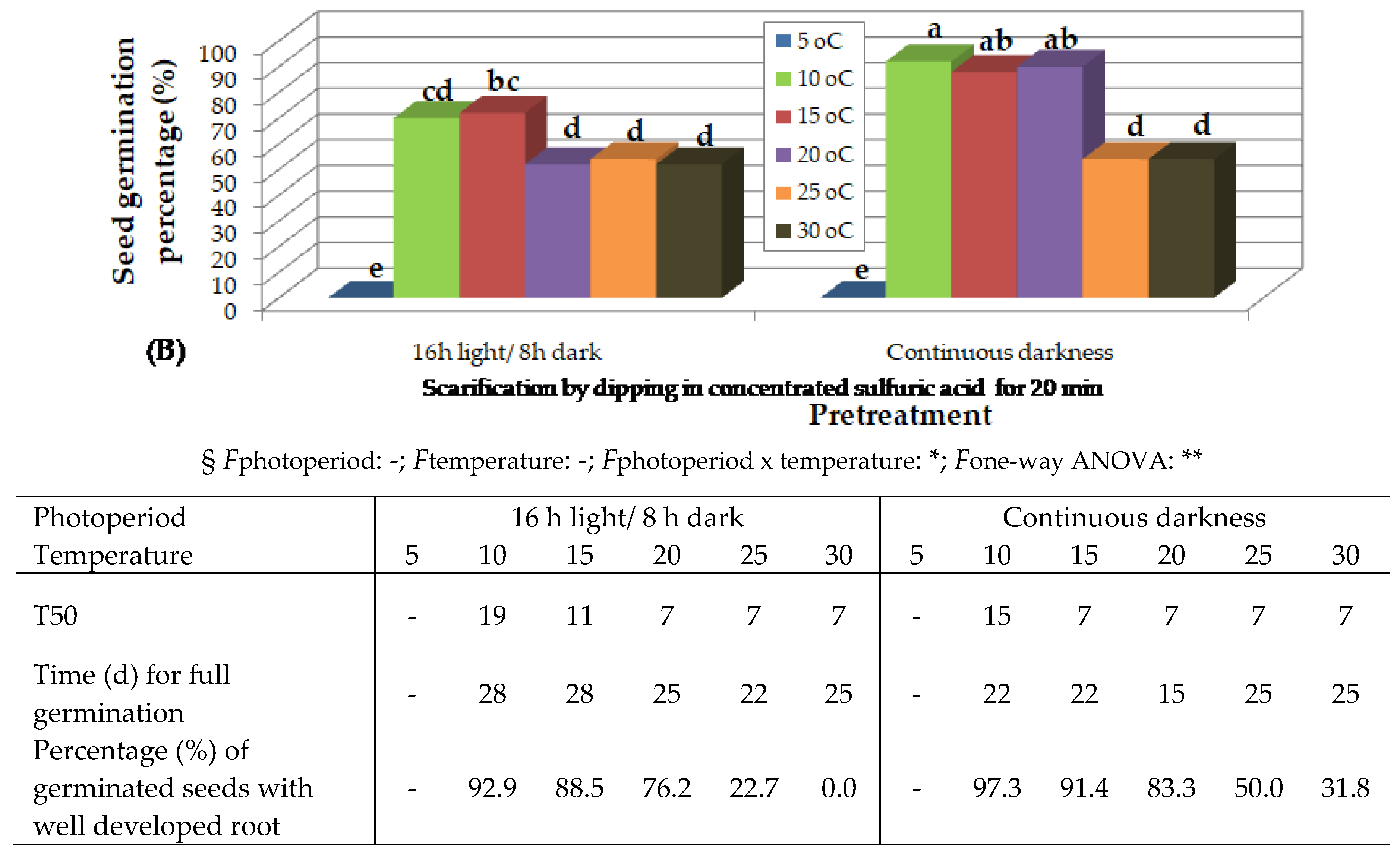

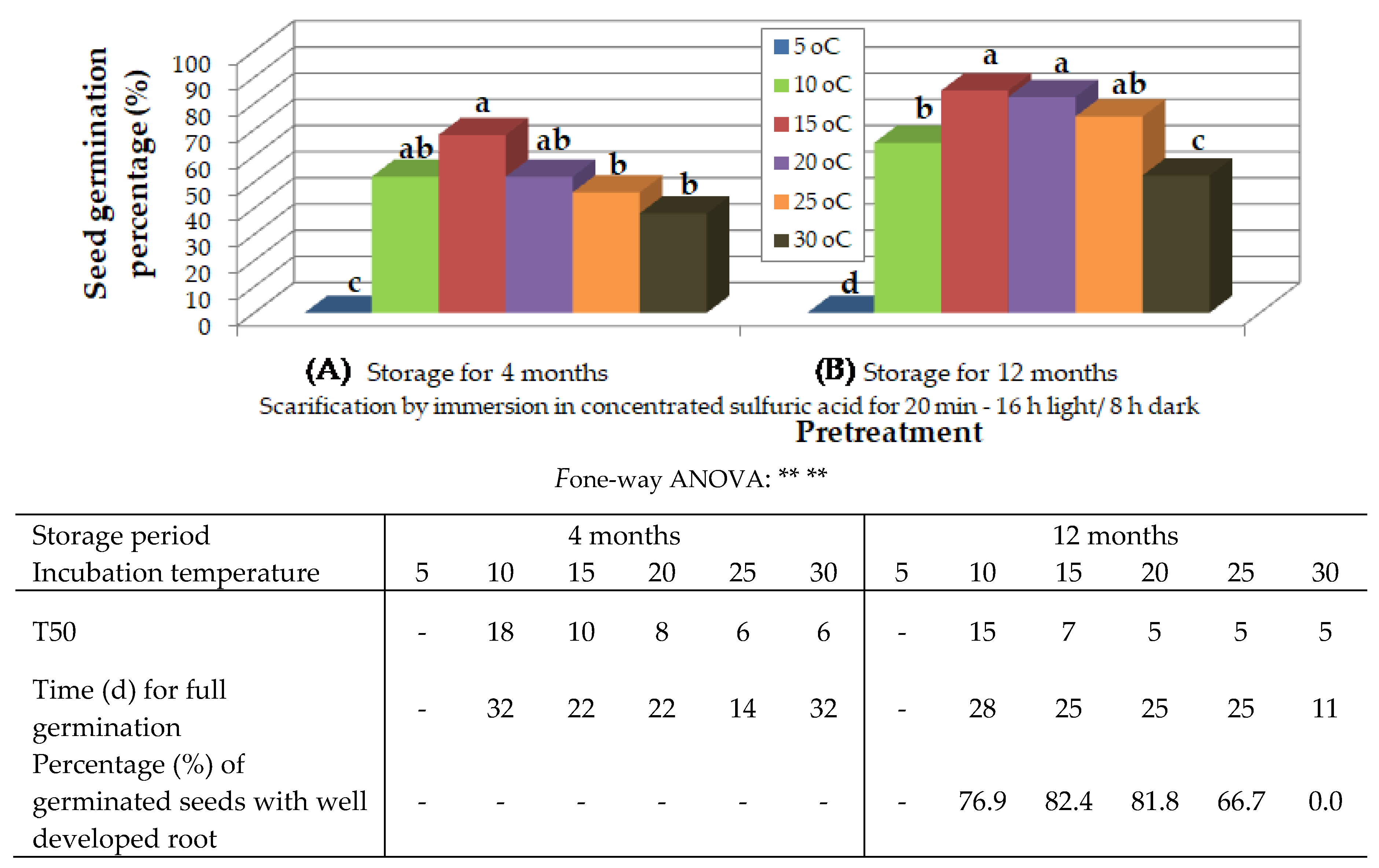

3.2.1. T. hirsuta

3.2.2. T. tartonraira ssp. tartonraira

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galicia-Herbada, D. Origin and diversification of Thymelaea (Thymelaeaceae): inferences from phylogenetic study based on ITS (rDNA) sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 2006, 257(3-4), 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmouzi, I.; Bouchmaa, N.; Kharbach, M.; Ezzat, S.M.; Merghany, R.M.; Berkiks, I.; El Jemli, M. Thymelaea genus: Ethnopharmacology, chemodiversity, and bioactivities. South African Journal of Botany 2021, 142, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjelal, A.; Henchiri, C.; Sari, M.; Sarri, D.; Hendel, N.; Benkhaled, A.; Ruberto, G. Herbalists and wild medicinal plants in M’Sila (North Algeria): An ethnopharmacology survey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148(2), 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papafotiou, M.; Martini, A.N.; Vlachou, G. In vitro propagation as a tool to enhance the use of native ornamentals in archaeological sites of Greece. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1155, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A.N.; Papafotiou, M. Effect of cytokinins on in vitro blastogenesis of Thymelaea tartonraira ssp. tartonraira (L.) All. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1242, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A.N.; Papafotiou, M. Investigation of micropropagation of the Mediterranean xerophyte Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. (Thymelaeaceae). Acta Hortic. 2020, 1298, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, D.-M.; Boscaiu, M.; Sestras, R.E.; Sestras, A.F.; Vicente, O. Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Invasive Potential of Ornamental Plants in the Mediterranean Area: Implications for Sustainable Landscaping. Agronomy 2025, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, A.; Taylor, W. Flowers of Greece and the Aegean; Publisher: Chatto and Windus: London, UK, 1977; pp. 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey, M.; Grey-Wilson, C. Mediterranean wild flowers; Publisher: Harper Collins Publishers: London, UK, 1993; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Cornara, L.; Borghesi, B.; Caporali, E.; Casazza, G.; Roccotiello, E.; Troiano, G.; Minuto, L. Floral features and reproductive ecology in Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. Plant Syst. Evol. 2005, 250, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommée, B.; Bompar, J.L.; Denelle, N. Sexual tetramorphism in Thymelaea hirsuta (Thymelaeaceae): evidence of the pathway from heterodichogamy to dioecy at the infraspecific level. American Journal of Botany 1990, 77(11), 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Maboud, M.M..; El-Zayat, M.A. Genetic and biochemical studies of Thymelaea hirsuta L. growing naturally at the North western coast of Egypt. Int. J. Plant & Soil Sci. 2020, 32, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyaoui, M.; Bouajila, J.; Cazaux, S.; Abderrabba, M. The impact of regional locality on chemical composition, anti-oxidant and biological activities of Thymelaea hirsuta L. extracts. Phytomedicine 2018, 41, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.M. Review article on chemical constituents and biological activity of Thymelaea hirsuta. Rec. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 3(2), 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Mekhfi, H.; Dassouli, A.; Serhrouchni, M.; Benjelloun, W. Phytotherapy of hypertension and diabetes in oriental Morocco. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997, 58(1), 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alafid, F.; Edrah, S.M.; Meelad, F.M.; Belhaj, S.; Altwair, K.; Maizah, N.R. Evaluation of phytochemical constituents and antibacterial activity of Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl, and that utilised as a conventional treatment of infertility and diabetic in Libya. World J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 8(11), 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, S.; Mekhfi, H.; Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Aziz, M.; Bnouham, M. Beneficial effect of Thymelaea hirsuta on pancreatic islet degeneration, renal fibrosis, and liver damages as demonstrated in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. The Scientific World Journal 2021, 2021(1), 6614903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, N. O.; Razafimandimby, B.; Auberon, F.; Azoulay, S.; Fernandez, X.; Berkani, A.; Bouchara, J.P.; Landreau, A. Antifungal and antiaging evaluation of aerial part extracts of Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) endl. Nat. Prod. Com. 2021, 16(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, M.; Matsuyama, K.; Miyamae, Y.; Shinmoto, H.; Kchouk, M.E.; Morio, T.; Shigemori, H.; Isoda, H. Antimelanogenesis effect of Tunisian herb Thymelaea hirsuta extract on B16 murine melanoma cells. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16(12), 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeridane, A.; Yousfi, M.; Nadjemi, B.; Boutassouna, D.; Stocker, P.; Vidal, N. Antioxidant activity of some Algerian medicinal plants extracts containing phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2005, 97(4), 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borris, R.P.; Blaskó, G.; Cordell, G.A. Ethnopharmacologic and phytochemical studies of the Thymelaeaceae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1988, 24(1), 41–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, E. Reconstructed materia medica of the Medieval and Ottoman al-Sham. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 80(2-3), 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigui, M.; Ben Hsouna, A.; Tounsi, S.; Jaoua, S. Chemical composition and evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Tunisian Thymelaea hirsuta with special reference to its mode of action. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 41, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamgui, H.; Jarboui, R.; Jeddou, K.B.; Torchi, A.; Siala, M.; Cherif, S.; Trigui, M. Polysaccharide from Thymelaea hirsuta L. leaves: Structural characterization, functional properties and antioxidant evaluation. Inter. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262(2), 129244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, N.M.; Alharby, H.F.; Alharbi, B.M.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Hashim, A.M. Thymelaea hirsuta and Echinops spinosus: Xerophytic plants with high potential for first- generation biodiesel production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahraoui, A.; El-Hilaly, J.; Israili, Z.H.; Lyoussi, B. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in the traditional treatment of hypertension and diabetes in south-eastern Morocco (Errachidia province). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110(1), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, S.; Koubaa, I.; Dhouib, I.; Khemakhem, B.; Marchand, P.; Allouche, N. New specific α-glucosidase inhibitor flavonoid from Thymelaea tartonraira leaves: structure elucidation, biological and molecular docking studies. Chem. Biodiv. 2023, 20(3), e202200944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Koubaa, I.; Cojean, S.; Picot, C.; Marchand, P.; Allouche, N. Phytochemical, antileishmanial, antifungal and cytotoxic profiles of Thymelaea tartonraira (L.) All. extracts. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 38(20), 3481–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaris, N.S.; Adamandiadou, S.; Siafaca, L.; Diamantopoulos, J. Nitrogen and phosphorous content in plant species of Mediterranean ecosystems in Greece. Vegetatio 1984, 55(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletiou-Christou, M.S.; Banilas, G.P.; Diamantoglou, S. (1998). Seasonal trends in energy conents and storage substances of the Mediterranean species Dittrichia viscosa and Thymelaea tartonraira. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1998, 39, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airò, M.; Fascella, G.; Zizzo, G.; Ruffoni, B. Preliminary studies on introduction and in vitro cultivation of Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. Italus Hortus 2004, 11(4), 144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Minuto, L.; Casazza, G.; Profumo, P. Population decrease of Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. in Liguria: conservation problems for the North Tyrrhenian sea. Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with All Aspects of Plant Biology 2004, 138(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafotiou, M.; Triandaphyllou, N.; Chronopoulos, J. Studies on propagation of species of the xerophytic vegetation of Greece with potential floricultural use. Acta Hortic. 2000, 541, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafotiou, M. In vitro propagation of temperate zone woody plants with potential ornamental use. Acta Hortic. 2010, 885, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaltout, K.H.; El-Shourbagy, M.N. Germination requirements and seedling growth of Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. Flora 1989, 183(5-6), 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijmoed, P. Collection, propagation and use of native plants. In Southern forest nursery association conference; Publisher: Southern Research Station: Asheville, USA, 1999; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, K.P. The challenge: High quality seed of native plants to ensure successful establishment. Seed Technology 2002, 24(1), 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, K.; Liu, X.D.; Xie, Q.; He, Z.H. Two faces of one seed: hormonal regulation of dormancy and germination. Mol. Plant 2016, 9(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Castaño, G.; Calleja-Cabrera, J.; Pernas, M.; Gómez, L.; Oñate-Sánchez, L. An Updated Overview on the Regulation of Seed Germination. Plants 2020, 9, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Chen, Z. The control of seed dormancy and germination by temperature, light and nitrate. Bot. Rev. 2020, 86(1), 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koornneef, M.; Bentsink, L.; Hilhorst, H. Seed dormancy and germination. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2002, 5(1), 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Meng, Y.J.; Shuai, H.W.; Liu, W.G.; Du, J.B.; Liu, J.; Yang, W.Y. Dormancy and germination: How does the crop seed decide? Plant biology 2015, 17(6), 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, S; Lin, R. The role of light in regulating seed dormancy and germination. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2020, 62(9), 1310–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.A.; Ma, W.; Shen, S.; Gu, A. Underlying Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms for Seed Germination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, P. (2023). Review on dormancy, causes, uses, and measures of overcoming it. Science 2023, 7(2), 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.R.; Hanson, J.; Mariam, Y. Effect of sulfuric acid pretreatment on breaking hard seed dormancy in diverse accessions of five wild Vigna species. Seed Sci. Technol. 2007, 35, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.D.; Black, M. Seeds-physiology of development and germination, 2nd ed.; Publisher: Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 445. [Google Scholar]

- Probert, R.J. The role of temperature in the regulation of seed dormancy and germination. In Seeds. The ecology of regeneration in plant communities, 2nd ed.; Fenner, M., Ed.; Publisher: CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 261–292. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Breaking seed dormancy during dry storage: A useful tool or major problem for successful restoration via direct seeding? Plants 2020, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R. J.; Masilamani, P.; Suthakar, B.; Rajkumar, P.; Sivakumar, S.D.; Manonmani, V. Seed dormancy and after-ripening mechanisms in seed germination: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2024, 36(10), 68–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.P.E. Handbook on Tetrazolium Testing, 1st ed.; Publisher: The International Seed Testing Association (ISTA): Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 1985; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Papafotiou, M.; Martini, A.N. In vitro seed and clonal propagation of the Mediterranean aromatic and medicinal plant Teucrium capitatum. HortScience 2016, 51(4), 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A.N.; Papafotiou, M. In vitro seed and clonal propagation of the Mediterranean bee friendly plant Anthyllis hermanniae L. Sustainability 2023, 15(5), 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjafi, F.; Bannayan, M.; Tabrizi, L.; Rastgoo, M. Seed germination and dormancy breaking techniques for Ferula gummosa and Teucrium polium. J. Arid Environ. 2006, 64, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, A.; Passera, C. Factors affecting the germination of albaida (Anthyllis cytisoides L.), a forage legume of the Mediterranean coast. J. Arid. Environ. 1997, 35, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsouklis, K.; Vlachou, G.; Trigka, M.; Papafotiou, M. In vitro studies on seed germination of the Mediterranean species Anthyllis barbajovis to facilitate its introduction into the floriculture industry. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, G.; Martini, A.Ν.; Dariotis, E.; Papafotiou, Μ. Comparative evaluation of seed germination of five Mediterranean sage species (Salvia sp.) native to Greece. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1298, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, E.; Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C.; Benakashani, F. A meta-analysis of the effects of treatments used to break dormancy in seeds of the megagenus Astragalus (Fabaceae). Seed Sci. Res. 2020, 30, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.M.; Van Staden, J.; Bell, W.E. Seed coat structure and dormancy. Plant Growth Regul 1992, 11, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, M.C.d.l.; Traveset, A. Reproductive ecology of Thymelaea velutina (Thymelaeaceae)-Factors contributing to the maintenance of heterocarpy. Plant Syst. Evol. 2005, 256, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sacco, A.; Gajdošová, Z.; Slovák, M; Turisová, I.; Turis, P.; Jaromír Kučera, J.; Müller, J.V. Daphne arbuscula (Thymelaeaceae) compared to the more widespread Daphne cneorum. Folia Geobot 2021, 656, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.A.C.; Rapson, G.L.; Robertson, A.W.; Fordham, R.A. Limitations on recruitment of the rare sand daphne Pimelea arenaria (Thymelaeaceae), lower North Island, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Bot. 2005, 43(3), 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolston, M.P. Water impermeable seed dormancy. Bot. Rev. 1978, 44, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silcock Richard, G.; Mann Michael, B. (2014) Germinating the seeds of three species of Pimelea sect. Epallage (Thymelaeaceae). Austr. J. Bot. 2014, 62, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabin, T.; Shrivastava, K. (2014). Factors affecting seed germination and establishment of critically endangered Aquilaria malaccensis (Thymelaeaceae). Asian J. Plant Sci. Res. 2014, 4(6), 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- De Alwis, H.N.; Subasinghe, S.M.C.U.P.; Hettiarachchi, D. S. Effect of storage time and temperature on Gyrinops walla Gaertn. seed germination. J. Envir. Prof. Sri Lanka 2016, 5(2), 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Galmés, J.; Medrano, H.; Flexas, J. Germination capacity and temperature dependence in Mediterranean species of the Balearic Islands. Forest Systems 2006, 15(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanos, C.A.; Kadis, C.C.; Skarou, F. Ecophysiology of germination in the aromatic plants thyme, savory and oregano (Labiatae). Seed Sci. Res. 1995, 5, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanos, C.A.; Doussi, M.A. Ecophysiology of seed germination in endemic Labiates of Crete. Israel J. Plant Sci. 1995, 43, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellou, E.; Vlachou, G.; Martini, A.N.; Bertsouklis, K.; Papafotiou, M. Seed germination of five sage species (Salvia sp.) of populations native to Greece. Acta Hortic. 2022, 1345, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sarification | Light conditions | Incubation temperature (oC) | Seed germination percentage (%) | Germination (%) with well developed seedling | T50 |

| (9M/23M) | (9M/23M) | (9M/23M) | |||

| Without scarification | 16 h light/ 8 h dark | 10 | 0.0 e§/ 0.0 f | 0.0 g/ 0.0 d | -/ - |

| 15 | 0.0 e/ 0.0 f | 0.0 g/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| 20 | 0.0 e/ 0.0 f | 0.0 g/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| 25 | 0.0 e/ 0.0 f | 0.0 g/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| Continuous darkness | 10 | 2.0 e/ 0.0 f | 2.0 fg/ 0.0 d | 19/ - | |

| 15 | 2.0 e/ 0.0 f | 2.0 fg/ 0.0 d | 18/ - | ||

| 20 | 0.0 e/ 0.0 f | 0.0 g/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| 25 | 0.0 e/ 0.0 f | 0.0 g/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| Scarification by immersing in concentrated sulfuric acid for 20 min | 16 h light/ 8 h dark | 10 | 55.3 c/ 76.0 c | 52.8 c/ 76.0 b | 22/ 20 |

| 15 | 33.8 d/ 22.0 e | 33.8 d/ 22.0 c | 17/ 18 | ||

| 20 | 32.8 d/ 16.0 ef | 19.4 ef/ 12.0 cd | 12/ 11 | ||

| 25 | 31.1 d/ 50.0 d | 11.1 fg/ 20.0 cd | 13/ 13 | ||

| Continuous darkness | 10 | 93.1 a/ 96.4 a | 88.1 a/94.0 a | 18/ 17 | |

| 15 | 91.3 a/ 100.0 a | 88.8 a/ 96.0 a | 11/ 10 | ||

| 20 | 78.6 b/ 100.0 a | 70.6 b/ 96.0 a | 7/ 8 | ||

| 25 | 50.0 c/ 84.0 b | 31.1 d/ 64.0 b | 8/ 7 | ||

| Fscarification | -/ - | -/ - | |||

| Fphotoperiod | -/ - | -/ - | |||

| Ftemperature | -/ - | -/ - | |||

| Fscarification x photoperiod | **/ ** | **/ ** | |||

| Fscarification x temperature | **/ ** | **/ ** | |||

| Fphotoperiod x temperature | */ ** | */ ** | |||

| Fscarification x photoperiod x temperature | **/ ** | **/ ** | |||

| Fone-way ANOVA | **/ ** | **/ ** | |||

| Mean values (n= 5 repetitions of 20 seeds) in each column followed by the same lower-case letter do not differ significantly at p ≤ 0.05 by Student’s t test. § * or **, significant at p ≤ 0.05 or p ≤ 0.01, respectively. | |||||

| Sarification | Light conditions | Incubation temperature (oC) | Seed germination percentage (%) | Germination (%) with well developed seedling | T50 |

| (9M/23M) | (9M/23M) | (9M/23M) | |||

| Without scarification | 16 h light/ 8 h dark | 10 | 0.0 d§/ 0.0 e | 0.0 d/ 0.0 d | -/ - |

| 15 | 0.0 d/ 0.0 e | 0.0 d/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| 20 | 2.0 d/ 0.0 e | 0.0 d/ 0.0 d | 23/ - | ||

| 25 | 0.0 d/ 0.0 e | 0.0 d/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| Continuous darkness | 10 | 0.0 d/ 0.0 e | 2.0 d/ 0.0 d | -/ - | |

| 15 | 2.0 d/ 2.0 e | 2.0 d/ 2.0 d | 25/ 12 | ||

| 20 | 0.0 d/ 0.0 e | 0.0 d/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| 25 | 0.0 d/ 0.0 e | 0.0 d/ 0.0 d | -/ - | ||

| Scarification by immersing in concentrated sulfuric acid for 20 min | 16 h light/ 8 h dark | 10 | 60.0 c/ 44.0 d | 51.9 b/ 34.0 bc | 23/ 18 |

| 15 | 90.0 a/ 54.0 abcd | 77.5 a/ 28.0 c | 13/ 12 | ||

| 20 | 72.5 abc/ 46.4 cd | 52.5 b/ 28.2 c | 9/ 7 | ||

| 25 | 67.5 bc/ 58.0 abc | 25.0 c/ 24.0 c | 6/ 6 | ||

| Continuous darkness | 10 | 75.0 ab/ 52.0 bcd | 72.5 a/38.0 bc | 18/ 15 | |

| 15 | 70.0 bc/ 68.0 a | 52.5 b/ 56.0 a | 12/ 10 | ||

| 20 | 80.0 ab/ 62.0 ab | 57.5 b/ 50.0 ab | 8/ 9 | ||

| 25 | 70.0 bc/ 60.0 abc | 40.4 bc/ 38.0 bc | 7/ 7 | ||

| Fscarification | **/ - | **/ - | |||

| Flight conditions | NS/ - | NS/ - | |||

| Ftemperature | NS/ - | NS/ NS | |||

| Fscarification x photoperiod | NS/ ** | NS/ * | |||

| Fscarification x temperature | NS/ ** | NS/ NS | |||

| Fphotoperiod x temperature | NS/ ** | NS/ NS | |||

| Fscarification x photoperiod x temperature | NS/ ** | NS/ NS | |||

| Fone-way ANOVA | **/ ** | **/ ** | |||

| Mean values (n= 5 repetitions of 20 seeds) in each column followed by the same lower-case letter do not differ significantly at p ≤ 0.05 by Student’s t test. § NS or * or **, non-significant at p ≤ 0.05 or significant at p ≤ 0.05 or p ≤ 0.01, respectively. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).