Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

05 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

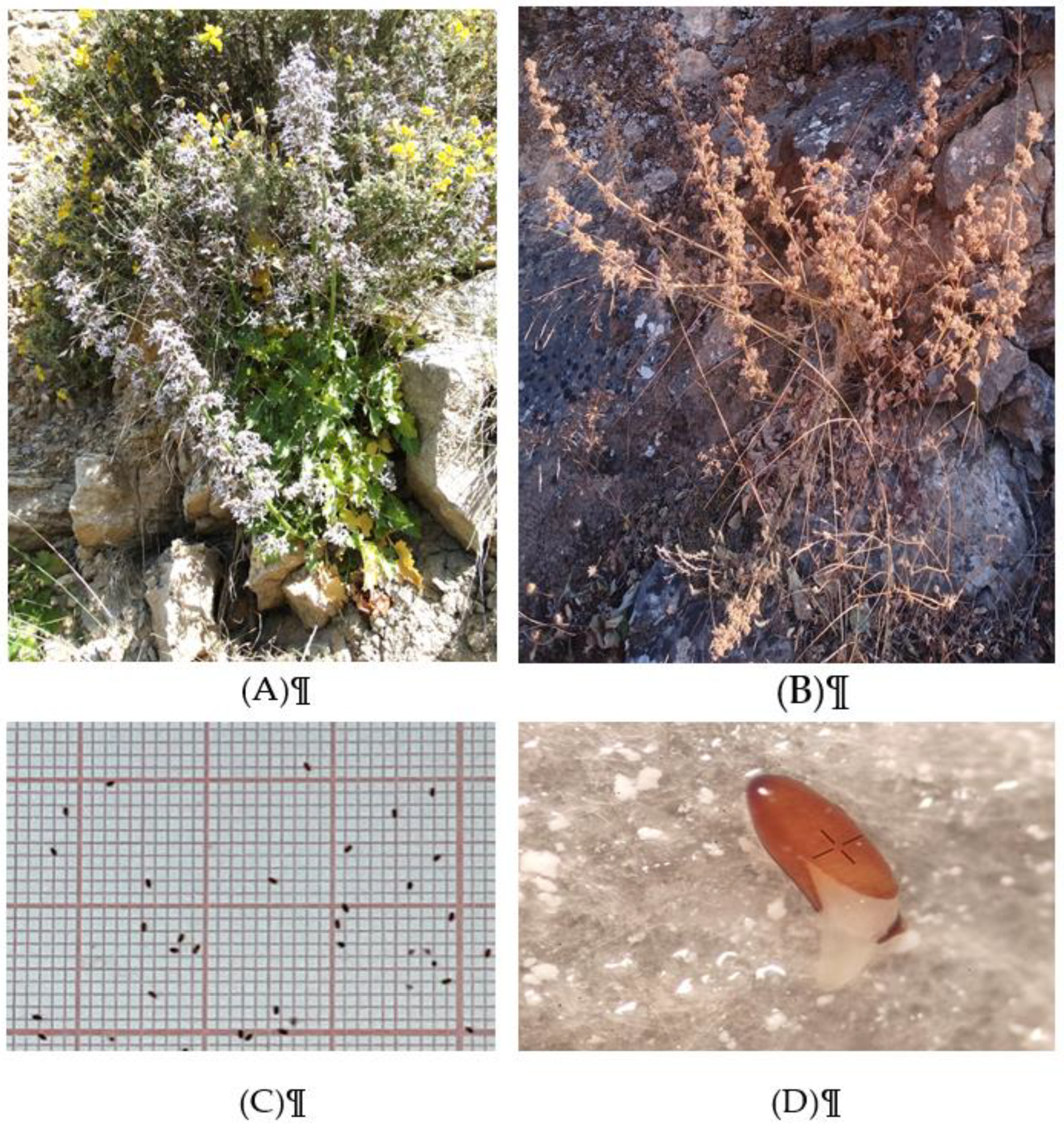

2.1. Characteristics of the focal plant species

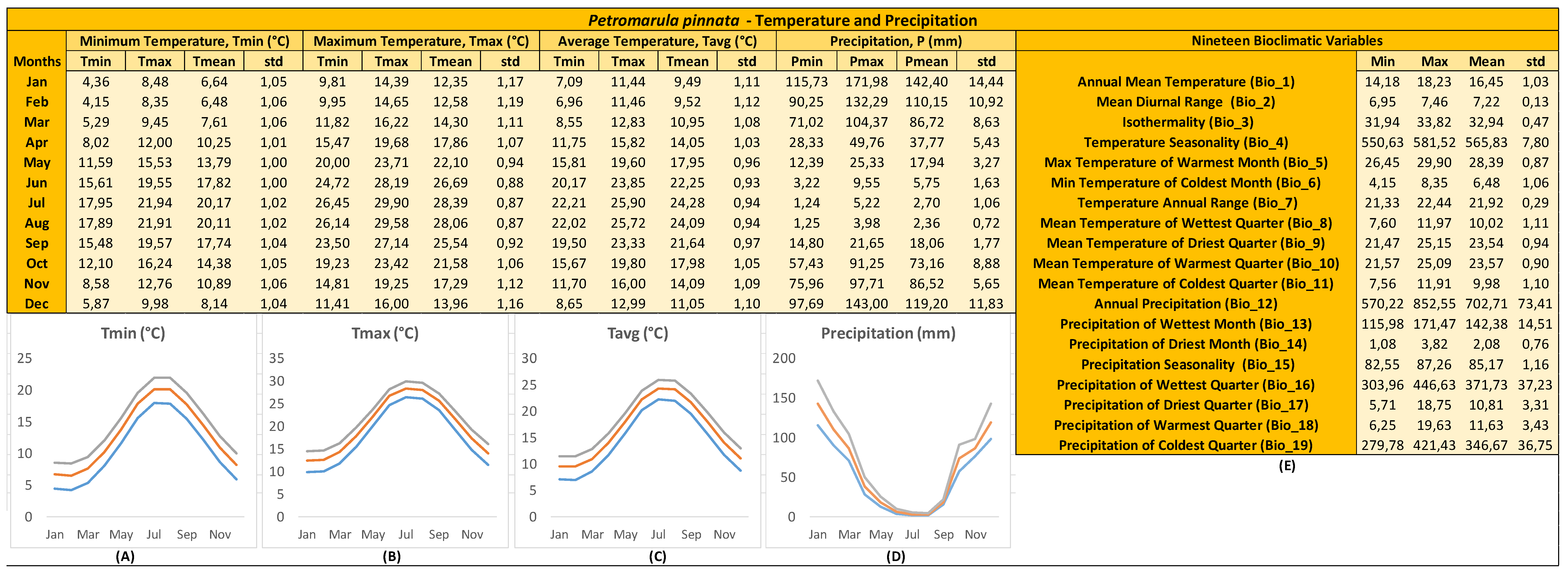

2.2. GIS Ecological Profiling

2.3. Seed Collection and Storage

2.4. Germination Tests

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ecological profiling

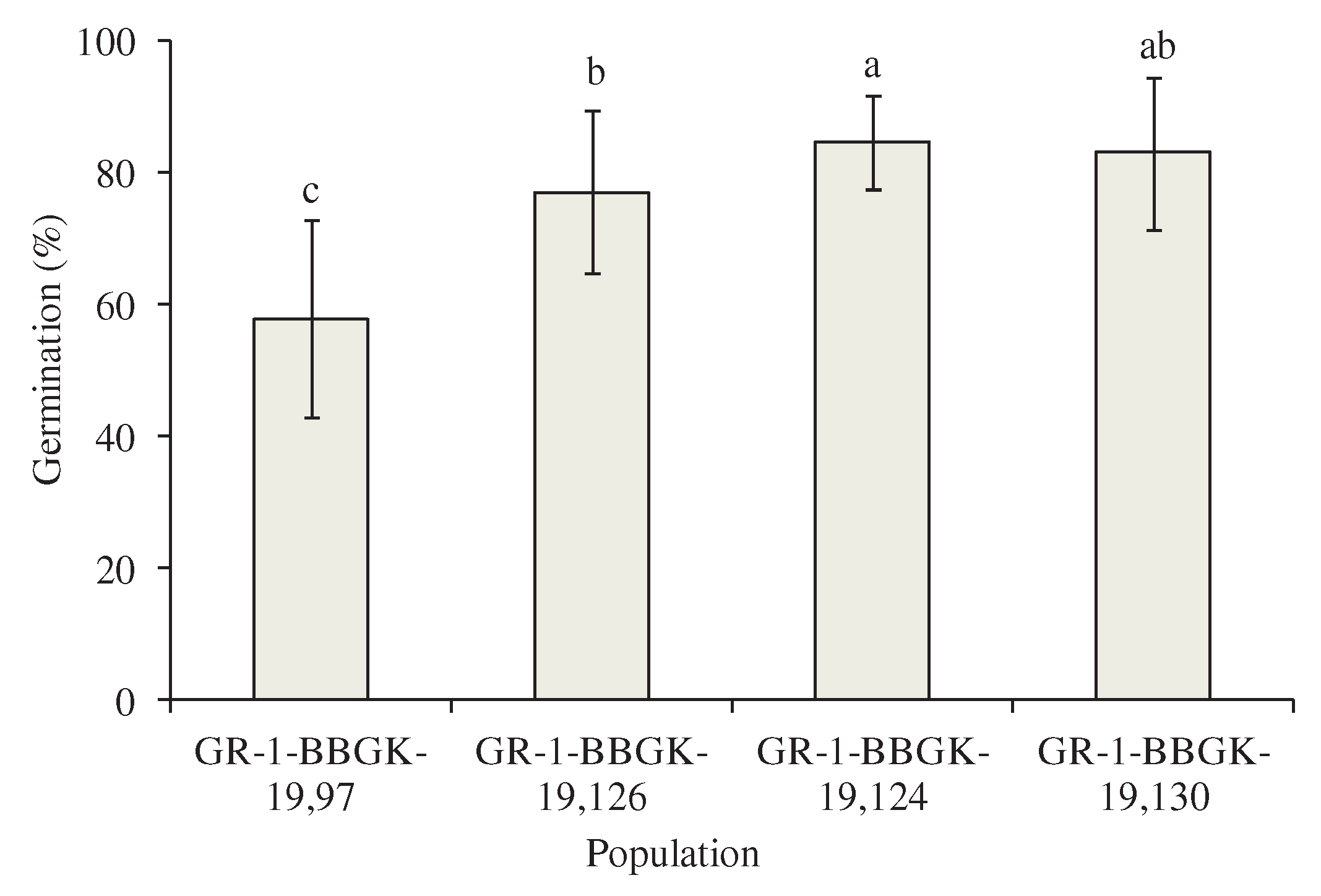

3.2. Seed Germination Success

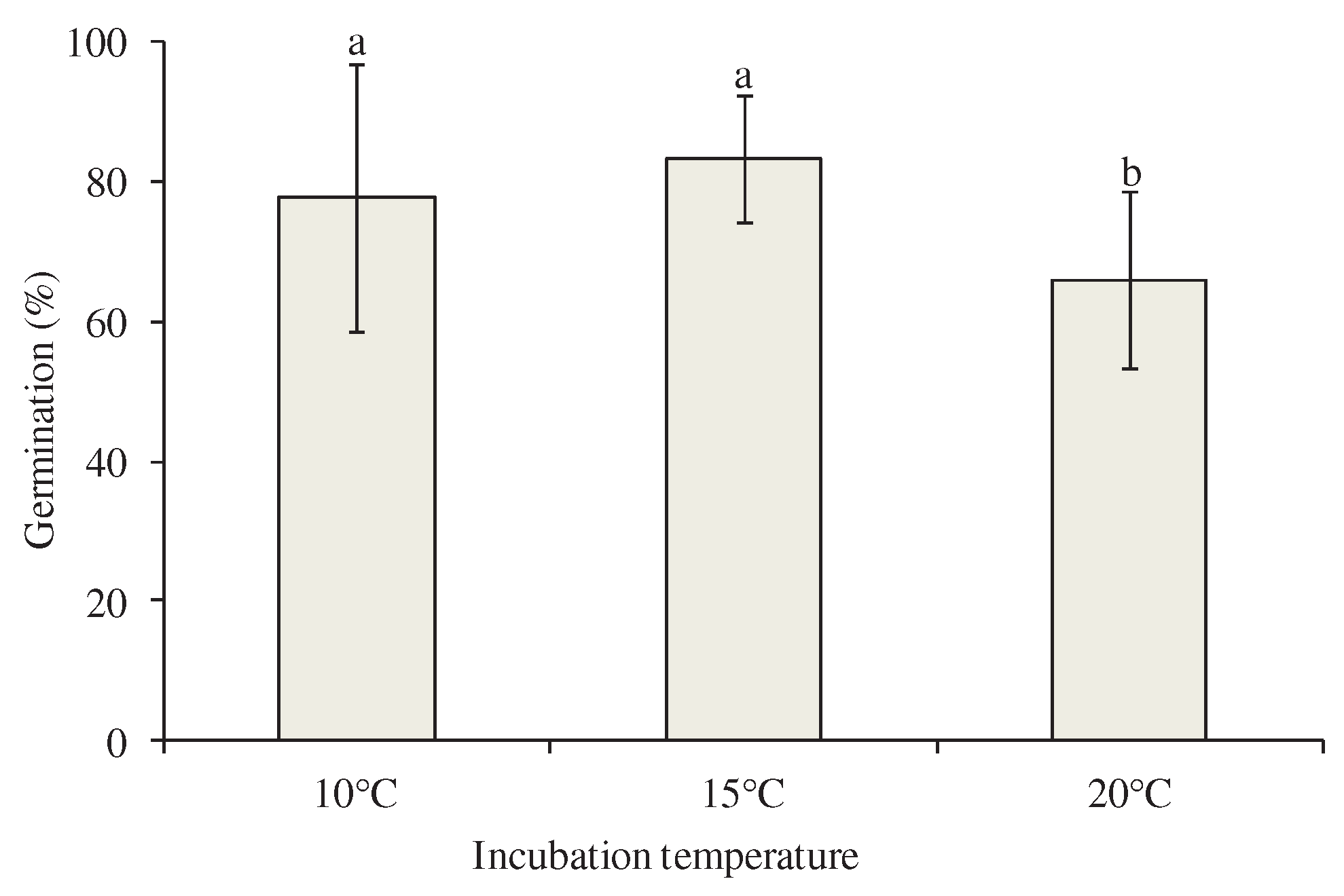

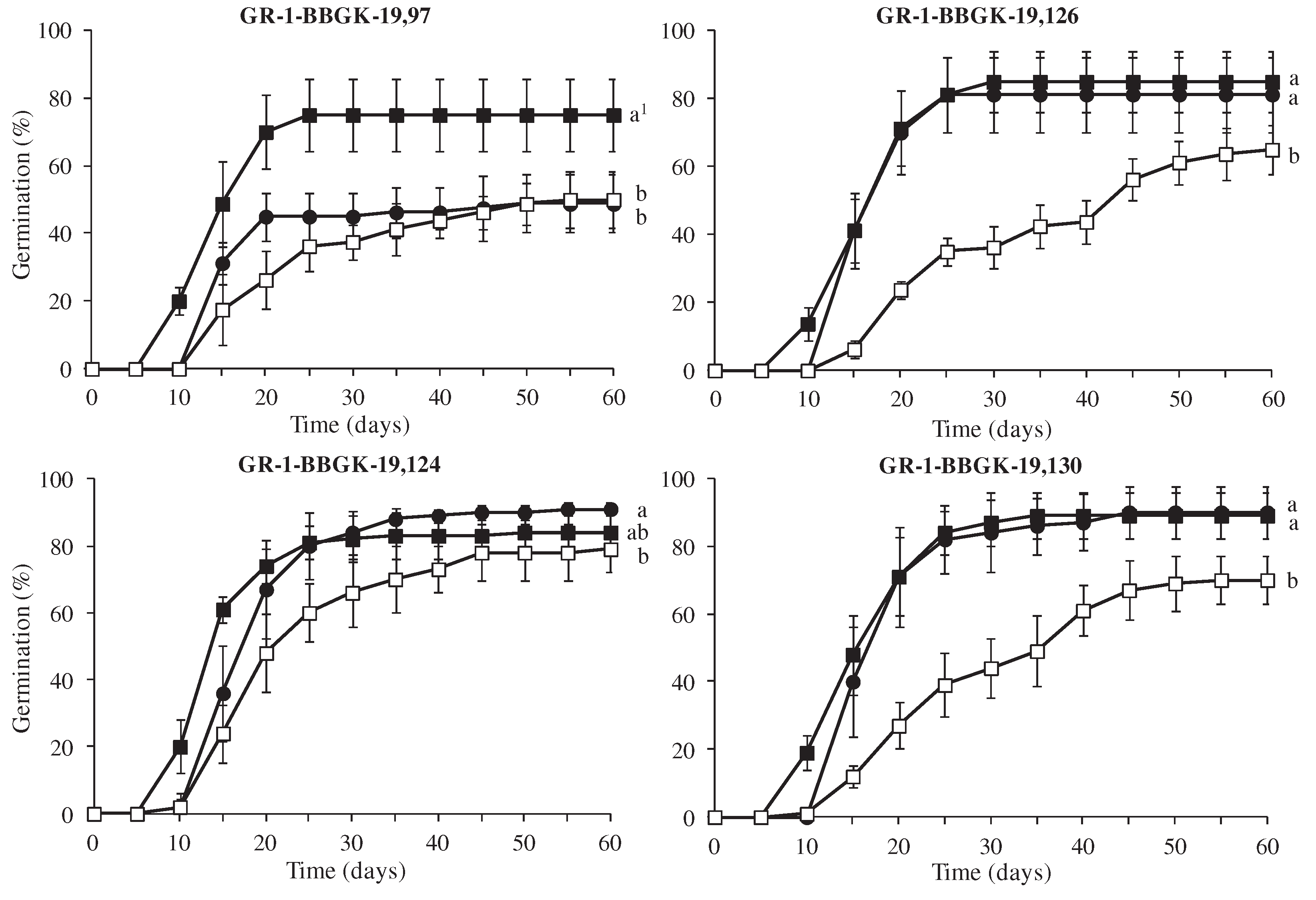

3.2.1. Effect of incubation temperature

3.2.2. Effects of light treatments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seglie, L.; Scariot, V.; Larcher, F.; Devecchi, M.; Chiavazza, P.M. In vitro seed germination and seedling propagation in Campanula spp. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 146, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scariot, V.; Seglie, L.; Caser, M.; Devecchi, M. Evaluation of ethylene sensitivity and postharvest treatments to improve the vase life of four Campanula species. Eur. J. Horticult. Sci. 2008, 73, 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Krigas, N.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Anestis, I.; Khabbach, A.; Libiad, M.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Lamchouri, F.; Tsiripidis, I.; Tsiafouli, M.A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Bourgou, S. Exploring the potential of neglected local endemic plants of three Mediterranean regions in the ornamental sector: Value chain feasibility and readiness timescale for their sustainable exploitation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellinese, N.; Smith, S.A.; Edwards, E.J.; Kim, S.T.; Haberle, R.C.; Avramakis, M.; Donoghue, M.J. Historical biogeography of the endemic Campanulaceae of Crete. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strid, A. Atlas of the Aegean Flora Part 1 (Text & Plates) & Part 2 (Maps), 1st ed.; Englera 33 (1 & 2); Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum: Berlin, Germany; Freie Universität: Berlin, Germany, 2016; ISSN 0170-4818. [Google Scholar]

- González-Tejero, M.R.; Casares-Porcel, M.; Sánchez-Rojas, C.P.; Ramiro-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Molero-Mesa, J.; Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E.; Censorii, E.; de Pasquale, C.; Della, A.; et al. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: Synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.K. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants; Springer International Publishing: Gewerbestr, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9789401772761. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.; Müller, W.E.; Galli, C. Local Mediterranean Food Plants and Nutraceuticals; Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 59, ISSN 1660-0347. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjichambis, A.CH.; Hadjichambi, D.P.; Della, A.; Giusti, M. E.; De Pasquale, C.; Lenzarini, Censorii, E.; Reyes Gonzales Tejero, M.; Sanchez-Rojas, C.P.; Ramiro Gutierrez, J.M; Skoula, M.; Johnson, Sarpaki, A.; Hmamouchi, M.; Jorhi, S.; El-Demerdash, M.; El-Zayat, M.; Pieroni, A. Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 59, 383–414. [CrossRef]

- Tsiftsoglou, O.S.; Lagogiannis, G.; Psaroudaki, A.; Vantsioti, A.; Mitić, M.N.; Mrmošanin, J.M.; Lazari, D. Phytochemical analysis of the aerial parts of Campanula pelviformis Lam. (Campanulaceae): Documenting the dietary value of a local endemic plant of Crete (Greece) traditionally used as wild edible green. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulou, E.; Trichopoulou, A. Green pies: The flavonoid rich Greek snack. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, K.M.; Karavergou, S.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Krigas, N.; Lazari, D. Phytochemical and antioxidant evaluation of the ex-situ cultivated species Petromarula pinnata (L.) A. DC. and Campanula cretica (A.DC.) Dietr. (Campanulaceae) from Crete (Greece). Planta Medica 2022, 88, 1523. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpoutzakis, E.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Mitakou, S.; Aligiannis, N.; Bozinou, E.; Gortzi, O.; Skaltsounis, L.A.; Lalas, S.I. Determination of the total phenolics content and antioxidant activity of extracts from parts of plants from the Greek Island of Crete. Plants 2023, 12, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulosi, S.; Thompson, J.; Rudebjer, P. Fighting Poverty, Hunger and Malnutrition with Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS): Needs, Challenges and the Way Forward; Biodiversity International: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgou, S.; Ben Haj Jilani, I.; Karous, O.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Greveniotis, V.; Avramakis, M.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. Medicinal-cosmetic potential of the local endemic plants of Crete (Greece), Northern Morocco and Tunisia: Priorities for conservation and sustainable exploitation of neglected and underutilized phytogenetic resources. Biology 2021, 10, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Anestis, I.; Lamchouri, F.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Greveniotis, V.; Tsiripidis, I.; Dariotis, E; Tsiafouli, M.A.; Krigas, N. Agro-alimentary potential of the neglected and underutilized local endemic plants of Crete (Greece), Rif-Mediterranean coast of Morocco and Tunisia: Perspectives and challenges. Plants 2021, 10, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, B. Practical Woody Plant Propagation for Nursery Growers; Timber Press Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 2006; p. 669. ISBN 9780881920628. [Google Scholar]

- Krigas, N.; Mouflis, G.; Grigoriadou, K. Conservation of important plants from the Ionian Islands at the Balkan Botanic Garden of Kroussia, N Greece: Using GIS to link the in situ collection data with plant propagation and ex situ cultivation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 3583–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigas, N.; Lykas, C.; Ipsilantis, I.; Matsi, T.; Weststrand, S.; Havström, M.; Tsoktouridis, G. Greek tulips: Worldwide electronic trade over the internet, global ex situ conservation and current sustainable exploitation challenges. Plants 2021, 10, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzilazarou, S.; El Haissoufi, M.; Pipinis, E.; Kostas, S.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; Lamchouri, F.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Aslanidou, V.; Greveniotis, V.; Sakelariou, M.A.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. GIS-Facilitated seed germination and multifaceted evaluation of the Endangered Abies marocana Trab. (Pinaceae) enabling conservation and sustainable exploitation. Plants 2021, 10, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostas, S.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Pipinis, E.; Bourgou, S.; Ben Haj Jilani, I.; Ben Othman, W.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Koundourakis, E.; Greveniotis, V.; Papaioannou, E.; Sakellariou, M.A.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. DNA Barcoding, GIS-Facilitated seed germination and pilot cultivation of Teucrium luteum subsp. gabesianum (Lamiaceae), a Tunisian local endemic with potential medicinal and ornamental value. Biology 2022, 11, 462. [Google Scholar]

- Pipinis, E.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Kostas, S.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; et al. Facilitating conservation and bridging gaps for the sustainable exploitation of the Tunisian local endemic plant Marrubium aschersonii (Lamiaceae). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzilazarou, S.; Kostas, S.; Pipinis, E.; Anestis, I.; Papaioannou, E.; Aslanidou, V.; Tsoulpha, P.; Avramakis, M.; Krigas, N.; Tsoktouridis, G. GIS-Facilitated seed germination, fertilization effects on growth, nutrient and phenol contents and antioxidant potential in three local endemic plants of Crete (Greece) with economic interest: Implications for conservation and sustainable exploitation. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-416677-6. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis, I.; Pipinis, E.; Kostas, S.; Papaioannou, E.; Karapatzak, E.; Dariotis, E.; Tsoulpha, P.; Koundourakis, E.; Chatzileontari, E.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Krigas, N. GIS-facilitated germination of stored seeds from five wild-growing populations of Campanula pelviformis Lam. and fertilization effects on growth, nutrients, phenol content and antioxidant potential. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reill, C.; Arnott, J.T.; Owens, J.N. Effects of photoperiod and moisture availability on shoot growth, seedling morphology, and cuticle and epicuticular wax features of container-grown western hemlock seedlings. Can. J. Forest Res. 1989, 19, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarropoulou, V.; Krigas, N.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Maloupa, E.; Grigoriadou, K. Seed Germination Trials and Ex Situ Conservation of Local Prioritized Endemic Plants of Crete (Greece) with Commercial Interest. Seeds 2022, 1, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsovoulou, K.; Daws, M.I.; Thanos, C.A. Campanulaceae: A family with small seeds that require light for germination. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanourakis, D.; Paschalidis, K.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Bilias, F.; Samara, E.; Liapaki, E.; Jouini, M.; Ipsilantis, I.; Maloupa, E.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Matsi, T.; Krigas, N. Pilot cultivation of the local endemic Cretan marjoram Origanum microphyllum (Benth.) Vogel (Lamiaceae): Effect of fertilizers on growth and herbal quality features. Agronomy 2021, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidis, K.; Fanourakis, D.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Bilias, F.; Samara, E.; Kalogiannakis, K.; Debouba, F.J.; Ipsilantis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; et al. Pilot cultivation of the Vulnerable Cretan endemic Verbascum arcturus L. (Scrophulariaceae): Effect of fertilization on growth and quality features. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougioumoutzis, K.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Panitsa, M.; Strid, A.; Dimopoulos, P. Extinction risk assessment of the Greek endemic flora. Biology 2021, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarina, M.; Kallimanis, A.S.; Dimopoulos, P.; Psaralexi, M.; Michailidou, D.E.; Sgardelis, S.P. Patterns and drivers of species richness and turnover of neo-endemic and palaeo-endemic vascular plants in a Mediterranean hotspot: The case of Crete, Greece. J. Biol. Res.-Thessaloniki 2019, 26, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical Procedures in Agricultural Research, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 0-471-87092-7. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor, G.W.; Cochran, W.C. Statistical Methods., 7th ed.; The Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Klockars, A.; Sax, G. Multiple Comparisons; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1986; p. 87. ISBN 0-8039-2051-2. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, M.; Higgens, S.; Culham, A. The effectiveness of botanic garden collections in supporting plant conservation: A European case study. Biodivers. Conserv. 2001, 10, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, E.; Turner, S.R.; Dixon, K.W. Biotechnology for saving rare and threatened flora in a biodiversity hotspot. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant 2011, 47, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blionis, G.; Vokou, D. Reproductive attributes of Campanula populations from Mt Olympos, Greece. Plant Ecol. 2005, 178, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C. C.; Baskin, J. M.; Yoshinaga, A.; Wolkis, D. Seed dormancy in Campanulaceae: Morphological and morphophysiological dormancy in six species of Hawaiian lobelioids. Botany 2020, 98(6), 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IPEN Accession number | Collection Site | Latitude (North) | Longitude (East) | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR-BBGK-1-19,97 | Viannos, Heraklion | 35.0471 | 25.4174 | 632 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,126 | Agios Georgios Selinaris, Lasithi | 35.2753 | 25.5549 | 225 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,124 | Agia Eirini gorge, Heraklion | 35.2844 | 25.1653 | 140 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,130 | Tylissos gorge, Heraklion | 35.2874 | 24.9716 | 395 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 2314.13 | 3 | 771.38 | 20.36 | 0.000 |

| Temperature | 1240.85 | 2 | 620.43 | 16.38 | 0.000 |

| `Population × Temperature | 701.35 | 6 | 116.89 | 3.09 | 0.015 |

| Area | Population | Incubation temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10°C | 15°C | 20°C | ||

| Semi-mountainous | GR-1-BBGK-19,97 | 48.75 b 1 ± 8.54 | 75.00 b ± 10.80 | 50.00 c ± 8.16 |

| GR-1-BBGK-19,130 | 90.00 a ± 7.66 | 89.00 a ± 6.83 | 70.00 ab ± 6.93 | |

| Lowland | GR-1-BBGK-19,126 | 81.25 a ± 11.09 | 85.00 ab ± 9.13 | 65.00 b ± 7.07 |

| GR-1-BBGK-19,124 | 91.00 a ± 2.00 | 84.00 ab ± 5.66 | 79.00 a ± 6.83 | |

| Germination percentage (%) | Mean Germination Time (Days) | |

|---|---|---|

| Light/dark | 86.00 ± 6.93 a 1 | 18.59 a ± 1.02 a |

| Dark | 80.00 ± 8.64 a | 20.06 a ± 1.72 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).