Submitted:

07 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

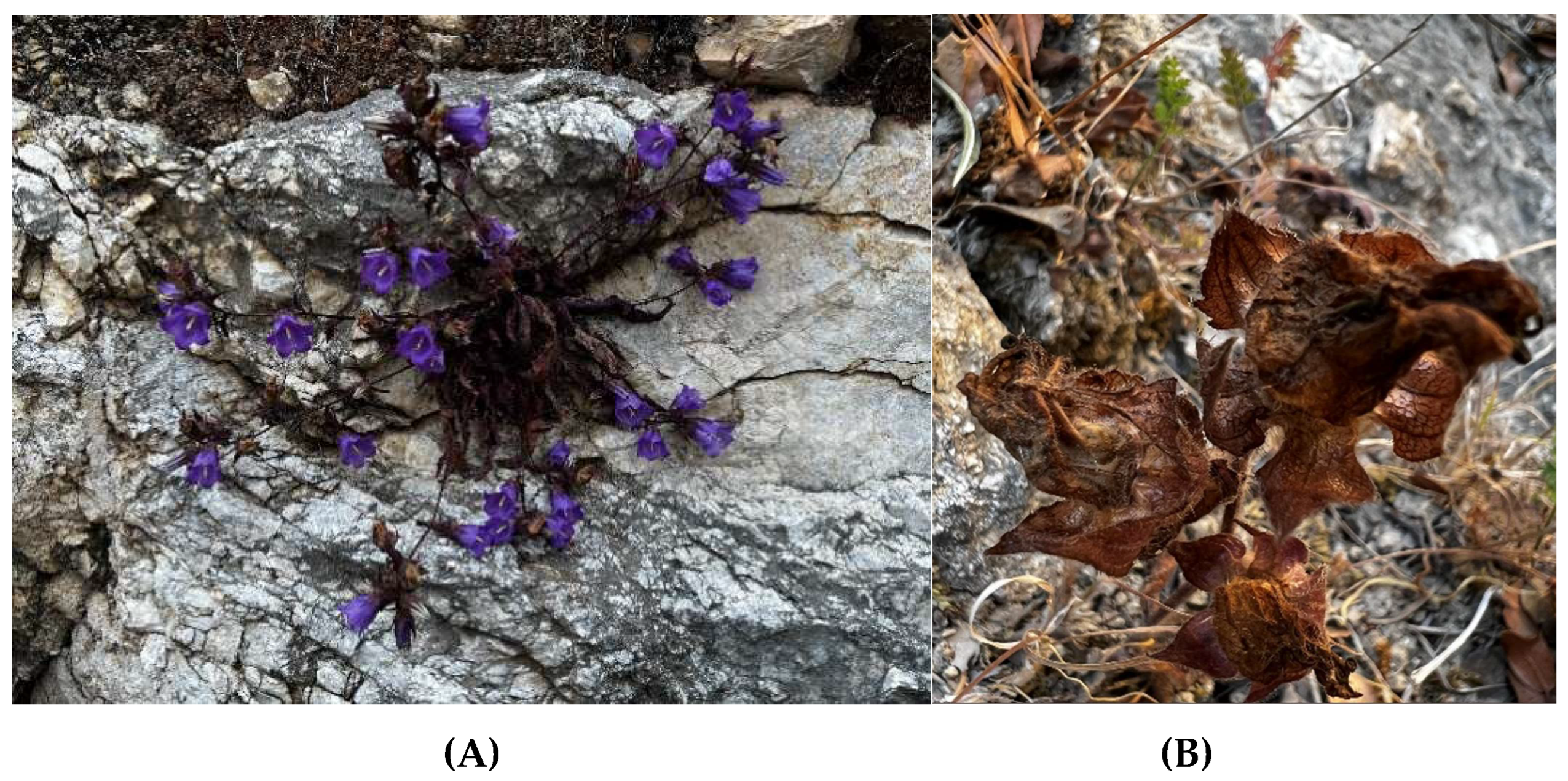

2.1. Plant Characteristics

2.2. GIS Ecological Profiling

2.3. Seed Collection and Storage

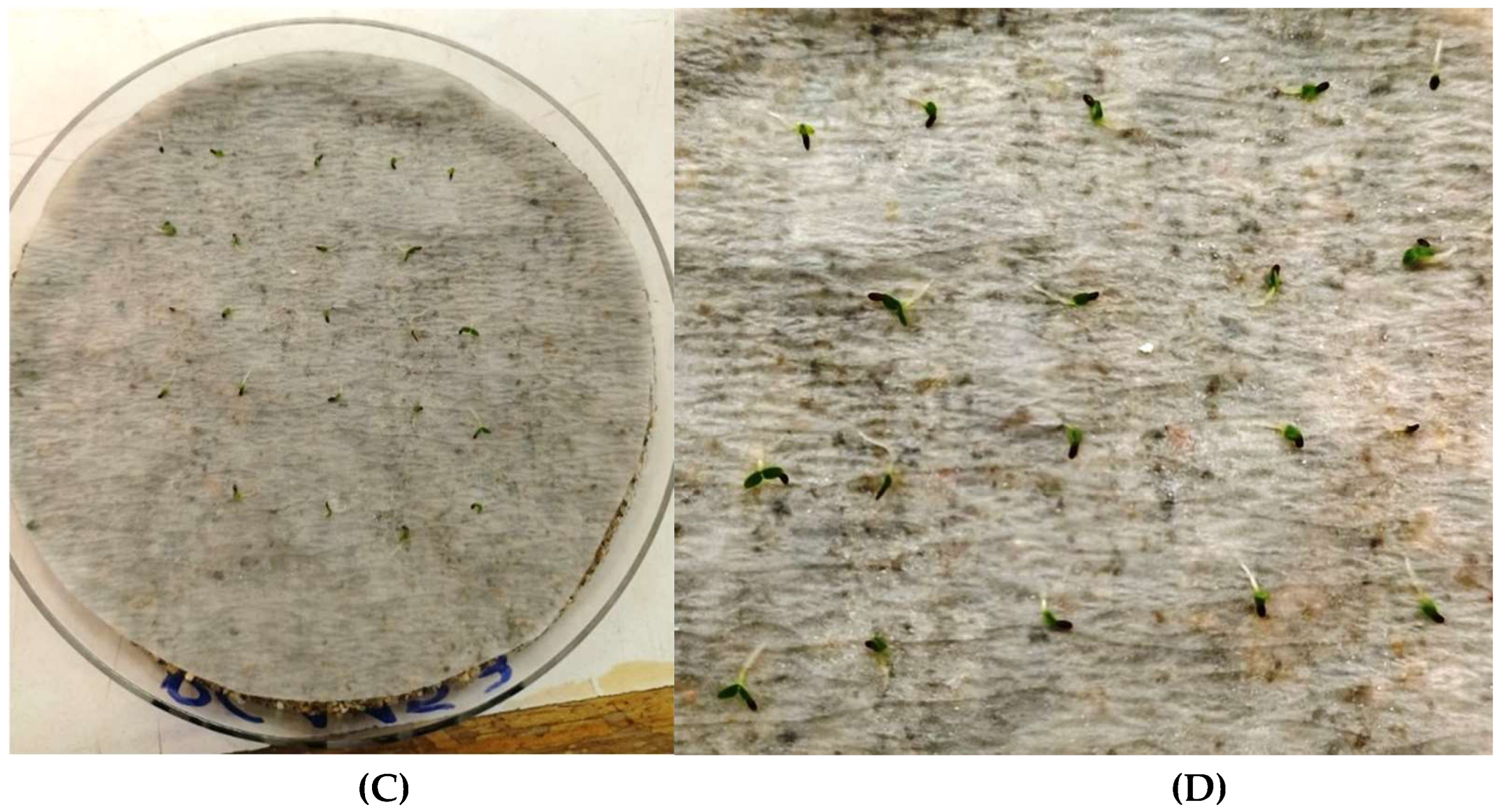

2.4. Germination Tests

2.5. Plant Production

2.6. Morphological and Physiological Measurements of Seedlings

2.7. Plant Tissue Analyses of Seedlings

2.8. Determination of Total Phenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

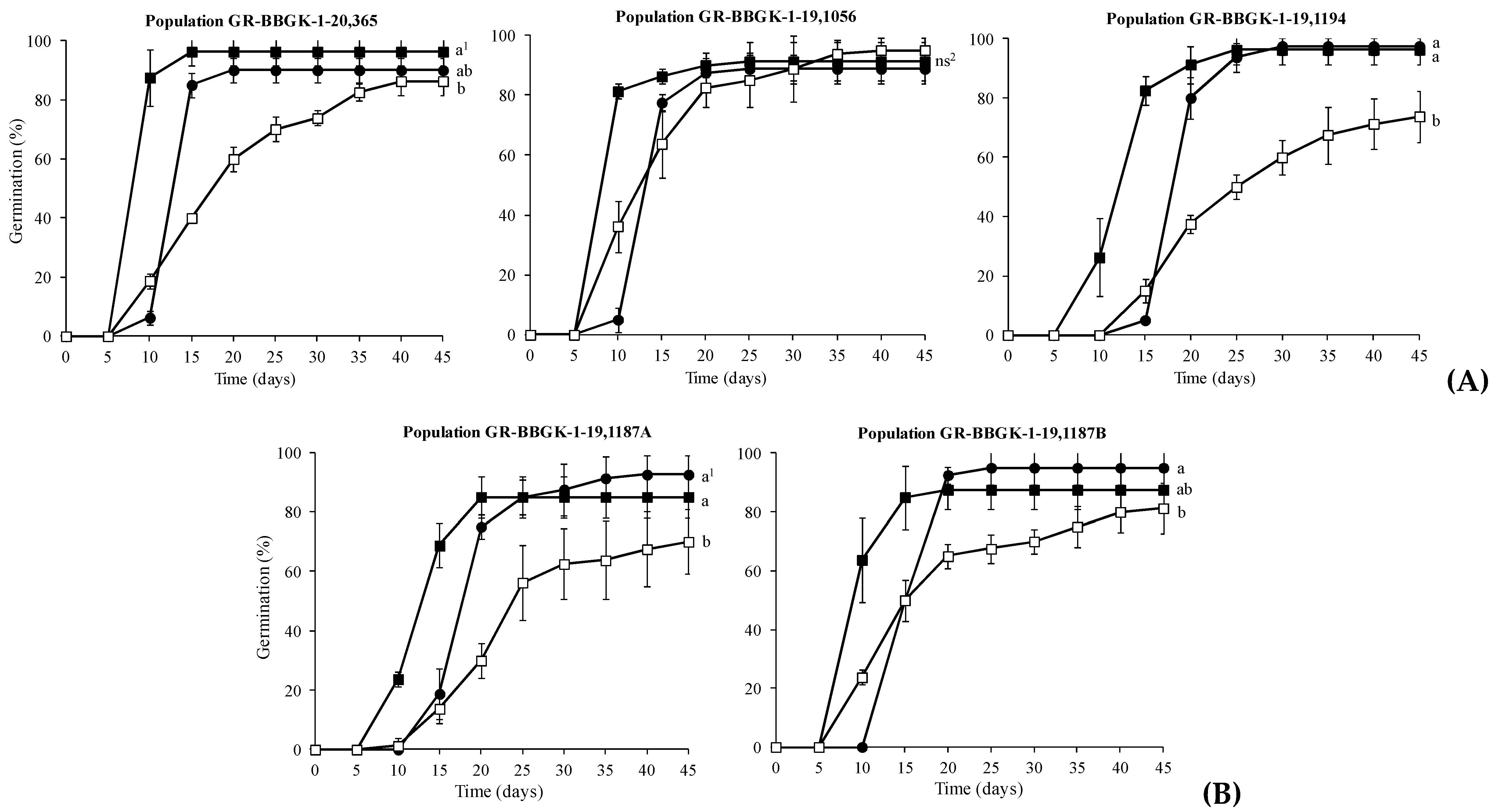

3.1. Seed Germination Success

3.1.1. Effects of temperature treatments

3.1.2. Effects of light treatments

3.1.3. Ecological profiling

3.2. Seedlings’ Growth

3.3. Leaf Nutrient Concentration

3.4. Total Phenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed Germination Protocols

4.2. Fertilization and morphological-physiological traits

4.3. Nutrient Content and Absorption

4.4. Total Phenol Content, Antioxidant Capacity and Fertilization Protocols

4.5. Re-Evaluation of Feasibility and Readiness Timescale for Sustainable Exploitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scariot, V.; Seglie, L.; Caser, M.; Devecchi, M. Evaluation of ethylene sensitivity and postharvest treatments to improve the vase life of four Campanula species. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 73, 4,166–170. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230691067_Evaluation_of_ethylene_sensitivity_and_postharvest_treatments_to_improve_the_vase_life_of_four_Campanula_species (accessed 3 July 2023).

- Krigas, N.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Anestis, I.; Khabbach, A.; Libiad, M.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Lamchouri, F.; Tsiripidis, I.; Tsiafouli, M.A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Bourgou, S. Exploring the potential of neglected local endemic plants of three Mediterranean regions in the ornamental sector: Value chain feasibility and readiness timescale for their sustainable exploitation. Sustainability 2021a, 13, 2539. [CrossRef]

- González-Tejero, M.R.; Casares-Porcel, M.; Sánchez-Rojas, C.P.; Ramiro-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Molero-Mesa, J.; Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E.; Censorii, E.; de Pasquale, C.; Della, A.; Paraskeva-Hadijchambi, D. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: Synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 341–357. [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Della, A.; Elena Giusti, M.; De Pasquale, C.; Lenzarini, C.; Censorii, E.; Reyes Gonzales-Tejero, M.; Patricia Sanchez-Rojas, C.; Ramiro-Gutierrez, J.M.; Skoula, M. Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int. J. Food Sci. 2008, 59, 5, 383-414. [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Müller; W.E.; Galli, C. Local Mediterranean food plants and nutraceuticals, Vol. 59.; Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2006. ISSN 1660–0347.

- Tsiftsoglou, O.S.; Lagogiannis, G.; Psaroudaki, A.; Vantsioti, A.; Mitić, M.N.; Mrmošanin, J.M.; Lazari, D. Phytochemical analysis of the aerial parts of Campanula pelviformis Lam. (Campanulaceae): Documenting the dietary value of a local endemic plant of Crete (Greece) traditionally used as wild edible green. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9, 7404. [CrossRef]

- Cellinese, N.; Smith, S.A.; Edwards, E.J.; Kim, S.T.; Haberle, R.C.; Avramakis, M.; Donoghue, M.J. Historical biogeography of the endemic Campanulaceae of Crete. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 7, 1253-1269. [CrossRef]

- Strid, A. Atlas of the Aegean Flora Part 1 (Text & Plates) & Part 2 (Maps), 1st ed.; Englera 33 (1 & 2); Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum: Berlin, Germany; Freie Universität: Berlin, Germany, 2016. ISSN 0170-4818.

- Menteli, V.; Krigas, N.; Avramakis, M.; Turland, N.; Vokou, D. Endemic plants of Crete in electronic trade and wildlife tourism: Current patterns and implications for conservation. J. Biol. Res. Thessalon. 2019, 26, 10. [CrossRef]

- Padulosi, S.; Thompson, J.; Rudebjer, P. Fighting Poverty, Hunger and Malnutrition with Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS): Needs, Challenges and the Way Forward; Biodiversity International: Rome, Italy, 2013. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10 568/68927 (accessed 3 July 2023).

- Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Anestis, I.; Lamchouri, F.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Greveniotis, V.; Tsiripidis, I.; Dariotis, E.; Tsiafouli, M.A.; Krigas, N. Agro-alimentary potential of the neglected and underutilized local endemic plants of Crete (Greece), Rif-Mediterranean coast of Morocco and Tunisia: Perspectives and challenges. Plants 2021, 10, 1770. [CrossRef]

- Bourgou, S.; Ben Haj Jilani, I.; Karous, O.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Greveniotis, V.; Avramakis, M.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. Medicinal-cosmetic potential of the local endemic plants of Crete (Greece), Northern Morocco and Tunisia: Priorities for conservation and sustainable exploitation of neglected and underutilized phytogenetic resources. Biology 2021, 10, 1344. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Heinrich, M.; Inocencio, C.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J. Gathered Mediterranean food plants—Ethnobotanical investigations and historical development. In Local Mediterranean Food Plants and Nutraceuticals; Heinrich, M., Müller, W.E., Galli, C., Eds.; Karger Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 59, pp. 18–74. [CrossRef]

- Scariot, V.; Seglie, L.; Gaino, W.; Devecchi, M. Evaluation of European native bluebells for sustainable floriculture. Acta Hortic. 2012, 937, 273–280. [CrossRef]

- Gkika, P.I.; Krigas, N.; Menexes, G.; Eleftherohorinos, I.G.; Maloupa, E. Conservation of the rare Erysimum naxense Snogerup and the threatened Erysimum krendlii Polatschek: Effect of temperature and light on seed germination. Open Life Sci. 2013, 8, 1194–1203. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadou, K.; Krigas, N.; Maloupa, E. GIS-facilitated in vitro propagation and ex situ conservation of Achillea occulta. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2011, 107, 531–540. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadou, K.; Krigas, N.; Sarropoulou, V.; Papanastasi, K.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Maloupa, E. In vitro propagation of medicinal and aromatic plants: The case of selected Greek species with conservation priority. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2019, 55, 635–646. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadou, K.; Sarropoulou, V.; Krigas, N.; Maloupa, E.; Tsoktouridis, G. GIS-facilitated effective propagation protocols of the Endangered local endemic of Crete Carlina diae (Rech. f.) Meusel and A. Kástner (Asteraceae): Serving ex-situ conservation needs and its future sustainable exploitation as an ornamental. Plants 2020, 9, 1465. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadou, K.; Krigas, N.; Sarropoulou, V.; Maloupa, E.; Tsoktouridis, G. Propagation and ex-situ conservation of Lomelosia minoana subsp. minoana and Scutellaria hirta-two ornamental and medicinal Cretan endemics (Greece). Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 12168. [CrossRef]

- Hatzilazarou, S.; El Haissoufi, M.; Pipinis, E.; Kostas, S.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; Lamchouri, F.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Aslanidou, V.; Greveniotis, V.; Sakellariou, M.A.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. GIS-Facilitated seed germination and multifaceted evaluation of the Endangered Abies marocana Trab. (Pinaceae) enabling conservation and sustainable exploitation. Plants 2021, 10, 2606. [CrossRef]

- Fanourakis, D.; Paschalidis, K.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Bilias, F.; Samara, E.; Liapaki, E.; Jouini, M.; Ipsilantis, I.; Maloupa, E.; Tsoktouridis, G; Matsi, T.; Krigas, N. Pilot cultivation of the local endemic Cretan marjoram Origanum microphyllum (Benth.) Vogel (Lamiaceae): Effect of fertilizers on growth and herbal quality features. Agronomy 2021, 12, 94. [CrossRef]

- Kostas, S.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Pipinis, E.; Bourgou, S.; Ben Haj Jilani, I.; Ben Othman, W.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Koundourakis, E.; Greveniotis, V.; Papaioannou, E.; Sakellariou, M.A.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. DNA Barcoding, GIS-Facilitated seed germination and pilot cultivation of Teucrium luteum subsp. gabesianum (Lamiaceae), a Tunisian local endemic with potential medicinal and ornamental value. Biology 2022, 11, 462. [CrossRef]

- Khabbach, A.; Libiad, M.; El Haissoufi, M.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Lamchouri, F.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Menteli, V.; Vokou, D.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. Electronic commerce of the endemic plants of Northern Morocco (Mediterranean Coast-Rif) and Tunisia over the Internet. Bot. Sci. 2021, 100, 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Krigas, N.; Mouflis, G.; Grigoriadou, K. Conservation of important plants from the Ionian Islands at the Balkan Botanic Garden of Kroussia, N Greece: Using GIS to link the in situ collection data with plant propagation and ex situ cultivation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 3583–3603. [CrossRef]

- Krigas, N.; Lykas, C.; Ipsilantis, I.; Matsi, T.; Weststrand, S.; Havström, M.; Tsoktouridis, G. Greek tulips: Worldwide electronic trade over the internet, global ex situ conservation and current sustainable exploitation challenges. Plants 2021b, 10, 580. [CrossRef]

- Krigas, N.; Karapatzak, E.; Panagiotidou, M.; Sarropoulou, V.; Samartza, I.; Karydas, A.; Damianidis, C.K.; Najdovski, B.; Teofilovski, A.; Mandzukovski, D.; Stipanović, V.D.; Papanastasi, K.; Kapagianni, P.D.; Fotakis, D.; Grigoriadou, K.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Andonovski, V.; Maloupa, E. Prioritizing plants around the cross-border area of Greece and the Republic of North Macedonia: Integrated conservation actions and sustainable exploitation potential. Diversity 2022, 14, 570. [CrossRef]

- Paschalidis, K.; Fanourakis, D.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Bilias, F.; Samara, E.; Kalogiannakis, K.; Debouba, F.J.; Ipsilantis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Matsi, T.; Krigas, N. Pilot cultivation of the Vulnerable Cretan endemic Verbascum arcturus L. (Scrophulariaceae): Effect of fertilization on growth and quality features. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14030. [CrossRef]

- Pipinis, E.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Kostas, S.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Koundourakis, E.; Greveniotis, V.; Papaioannou, E.; Sakellariou , M.A.; Anestis, I.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. Facilitating conservation and bridging gaps for the sustainable exploitation of the Tunisian local endemic plant Marrubium aschersonii (Lamiaceae). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1637. [CrossRef]

- Sefi, O.; Bourgou, S.; Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Libiad, M.; Khabbach, A.; El Haissoufi, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Krigas, N.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z. Bioactivities and phenolic composition of Limonium boitardii Maire and L. cercinense Brullo & Erben (Plumbaginaceae): Two Tunisian strict endemic plants. Inter. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 2496–2511. [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. ISBN: 978-0-12-416677-6.

- Macdonald, B. Practical Woody Plant Propagation for Nursery Growers; Timber Press Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 2006; p. 669. ISBN: 9780881920628.

- Koutsovoulou, K.; Daws, M.I.; Thanos, C.A. Campanulaceae: A family with small seeds that require light for germination. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 1, 135–143. [CrossRef]

- O’Reill, C.; Arnott, J.T.; Owens, J.N. Effects of photoperiod and moisture availability on shoot growth, seedling morphology, and cuticle and epicuticular wax features of container-grown western hemlock seedlings. Can. J. Forest Res. 1989, 19, 122–131. [CrossRef]

- Buendia-Velazquez, M.V.; Lopez-Lopez, M.A.; Cetina-Alcala, V.M.; Diakite, L. Substrates and nutrient addition rates affect morphology and physiology of Pinus leiophylla seedlings in the nursery stage. iForest 2016, 10, 115–120. [CrossRef]

- Kougioumoutzis, K.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Panitsa, M.; Strid, A.; Dimopoulos, P. Extinction risk assessment of the Greek endemic flora. Biology 2021, 10, 195. [CrossRef]

- Lazarina, M.; Kallimanis, A.S.; Dimopoulos, P.; Psaralexi, M.; Michailidou, D.E.; Sgardelis, S.P. Patterns and drivers of species richness and turnover of neo-endemic and palaeo-endemic vascular plants in a Mediterranean hotspot: the case of Crete, Greece. J. Biol. Res.-Thessaloniki 2019, 26, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.H. and Roberts, E.H. The quantification of ageing and survival in orthodox seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 1981, 9, 373-409.

- Richardson, A.D.; Duigan, S.P.; Berlyn, G.P. An evaluation of noninvasive methods to estimate foliar chlorophyll content. New Phytol. 2002, 153, 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Cessna, S.; Demmig-Adams, B.; Adams, W.W., III. Exploring photosynthesis and plant stress using inexpensive chlorophyll fluorometers. J. Nat. Resourc. Life Sci. Educ. 2010, 39, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.E.; Grimshaw, H.M.; Rowland, A.P. Chemical analysis. In Methods in Plant Ecology; Moore, P.D., Chapman, S.B., Eds.; Blackwell Scientific Publication: Oxford, UK, 1986; pp. 285–344. ISBN: 9780632003211.

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Total phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 2: Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 403–430. Available online: https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2134/agronmonogr9.2.2ed. frontmatter (accessed 3 July 2023).

- Bremmer, J.M.; Mulvaney, C.S. Nitrogen - Total, In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 2: Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 595–624. Available online: https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2134/agronmonogr9.2.2ed. frontmatter (accessed 3 July 2023).

- Hatzilazarou, S.; Pipinis, E.; Kostas, S.; Stagiopoulou, R.; Gitsa, K.; Dariotis, E.; Avramakis, M.; Samartza, I.; Plastiras, I.; Kriemadi, E.; Bareka, P.; Lykas, C.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Krigas, N. Influence of temperature on seed germination of five wild-growing Tulipa species of Greece associated with their ecological profiles: Implications for conservation and cultivation. Plants 2023, 12, 1574. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical procedures in agricultural research, 2nd ed. Wiley: New York, USA, 1984. ISBN 0-471-87092-7.

- Klockars, A.; Sax, G. Multiple Comparisons; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1986; p. 87. ISBN 0-8039-2051-2.

- Blionis, G.; Vokou, D. Reproductive attributes of Campanula populations from Mt Olympos, Greece. Plant Ecol. 2005, 178, 77–88. [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sulaiman, N.; Sõukand, R. Chorta (wild greens) in Central Crete: The bio-cultural heritage of a hidden and resilient ingredient of the Mediterranean Diet. Biology 2022, 11, 673. [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.X.; Dai, T.B.; Jiang, D. Effects of nitrogen and potassium application levels on flag leaf photosynthetic characteristics after anthesis in winter wheat. Acta Agron. Sin. 2007, 33, 1667–1673.

- Yruela, I. Transition metals in plant photosynthesis. Metallomics 2013, 5, 9, 1090-109. [CrossRef]

- Dalcorso, G.; Manara, A.; Piasentin, S.; Furini, A. Nutrient metal elements in plants. Metallomics 2014, 10, 1770-1788. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. 8 - Functions of Mineral Nutrients: Macronutrients. In Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995; pp. 229-312.

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Q. Copper-based foliar fertilizer and controlled release urea improved soil chemical properties, plant growth and yield of tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 143, 109-114. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, F.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, T. Determination and analysis of leaf P and K concentrations of several plant species in Jinan city. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 53, 03055. [CrossRef]

- Burns, I.G. Influence of plant nutrient concentration on growth rate: Use of a nutrient interruption technique to determine critical concentrations of N, P and K in young plants. Plant Soil 1992, 142, 221–233. [CrossRef]

- See, C.R.; Yanai, R.D.; Fisk, M.C.; Vadeboncoeur, M.A.; Quintero, B.A.; Fahey, T.J. Soil nitrogen affects phosphorus recycling: Foliar resorption and plant-soil feedbacks in a northern hardwood forest. Ecology 2015, 96, 2488–2498. [CrossRef]

- Siedliska, A.; Baranowski, P.; Pastuszka-Wozniak, J.; Zubik, M.; Krzyszczak, J. Identification of plant leaf phosphorus content at different growth stages based on hyperspectral reflectance. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 28. [CrossRef]

- Dumlu, M.U.; Gurkan, E.; Tuzlaci, E. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Campanula alliariifolia, Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 22, 6, 477-482. [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, N.A.; Abualhasan, M. Comparison in vitro of Antioxidant Activity between Fifteen Campanula Species (Bellflower) from Palestinian Flora. Pharmacogn. J. 2015, 7, 5, 276-279. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.R.; Ardekani, M.R.S.; Vazirian, M.; Lamardi, S.N.S. Campanula latifola, giant bellflower: Ethno-botany, phytochemical and antioxidant evaluation. Tradit. Integr. Med. 2018, 3, 113-119. Available online: https://jtim.tums.ac.ir/index.php/jtim/article/view/168 (accessed 3 July 2023).

| IPEN Accession number | Collection date | Collection site in Lasithi, Eastern Crete | Latidude (North) | Longitude (East) | Altitude (m) |

| GR-BBGK-1-20,365 | 26 July 2020 | After Kalo Chorio | 35.1242 | 25.7490 | 45 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1056 | 6 August 2019 | Istron | 35.1248 | 25.7444 | 25 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1194 | 29 July 2019 | Mochlos area |

35.1725 | 25.9051 | 105 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1187A | 14 June 2019 | Thrypti northern outskirts |

35.0931 | 25.8639 | 835 |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1187B | 14 June 2019 | Central Thrypti | 35.0903 | 25.8658 | 870 |

| Chemical analysis | Mechanical analysis | ||||||

| pH | Organic matter (%) | Soluble salts (mS/cm) | CaCO3 (%) |

Sand (%) |

Silt (%) |

Clay (%) |

|

| 8.12 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 5.50 | 56.00 | 28.00 | 16.00 | |

| Macronutrient concentrations (ppm) | |||||||

| N-NO3 | P | K | Mg | Ca | |||

| 8.00 | 8.00 | 104.00 | 842.00 | >2000 | |||

| Micronutrient concentrations (ppm) | |||||||

| Fe | Zn | Mn | Cu | ||||

| 4.7 | 2.00 | 7.06 | 0.77 | ||||

|

Area |

Population | Incubation Temperatures | ||

| 10°C | 15°C | 20°C | ||

|

Lowland |

GR-BBGK-1-20,365 | 90.00 ± 4.08 ab1 | 96.25 ± 4.79 a | 86.25 ± 4.79 b |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1056 | 88.75 ± 4.79 b | 91.25 ± 2.50 ab | 95.00 ± 4.08 a | |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1194 | 97.50 ± 2.89 a | 96.25 ± 4.79 a | 73.75 ± 8.54 cd | |

|

Semi-mountainous |

GR-BBGK-1-19,1187A | 92.50 ± 2.89 ab | 85.00 ± 4.08 b | 70.00 ± 10.80 d |

| GR-BBGK-1-19,1187B | 95.00 ± 4.08 ab | 87.50 ± 5.00 b | 81.25 ± 8.54 bc | |

| Germination percentage (%) | Mean germination time (days) | |

| Light/dark | 98.75 ± 2.50 a1 | 10.95 ± 0.14 a |

| Dark | 95.00 ± 4.08 a | 11.32 ± 0.53 a |

| Attribute (Unit) | Control | INM | ChF |

| Shoot height (cm) | 18.58 ± 2.23 a* | 17.75 ± 2.30 a | 19.92 ± 2.43 a |

| Root collar diameter (mm) | 8.94 ± 1.27 a | 9.27 ± 1.51 a | 9.28 ± 1.80 a |

| Number of shoots | 11.58 ± 1.73 a | 11.08 ± 2.74 a | 13.25 ± 3.49 a |

| Root dry biomass (g) | 1.00 ± 0.12 b | 1.72 ± 0.41 a | 1.39 ± 0.42 ab |

| Above ground dry biomass (g) | 1.89 ± 0.29 a | 1.85 ± 0.30 a | 2.32 ± 0.26 a |

| Chlorophyll content index (CCI) | 17.72 ± 2.96 c | 50.59 ± 7.66 a | 29.94 ± 7.44 b |

| Chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) | 0.748 ± 0.006 b | 0.763 ± 0.022 a | 0.768 ± 0.009 a |

| Treatment | Nitrogen (N) (%) | Phosphorus (P) (mg/g) | Potassium (K) (mg/g) | Calcium (Ca) (mg/g) | Magnesium (Mg) (mg/g) | Sodium (Na) (mg/g) |

| Above-ground part (leaves, stems) | ||||||

| Control | 1.25 c* | 3.20 a | 26.39 b | 15.18 c | 4.88 b | 8.35 c |

| INM | 2.12 a | 2.99 b | 30.17 a | 18.85 a | 5.52 a | 14.63 a |

| ChF | 1.65 b | 3.01 b | 25.45 c | 16.19 b | 4.79 b | 11.06 b |

| Below-ground part (roots) | ||||||

| Control | 1.11 c | 1.23 a | 5.27 a | 2.48 b | 1.93 c | 3.04 a |

| INM | 2.06 a | 0.87 b | 4.41 b | 3.43 a | 2.37 a | 3.28 a |

| ChF | 1.34 b | 1.24 a | 5.27 a | 2.30 b | 2.17 b | 2.98 a |

| Treatment | Iron (Fe) (ppm) | Manganese (Mn) (ppm) | Zinc (Zn) (ppm) | Copper (Cu) (ppm) |

| Above-ground part (leaves, stems) | ||||

| Control | 633.08 c* | 52.71 b | 12.22 c | 15.65 b |

| INM | 721.71 b | 64.84 a | 19.80 a | 152.79 a |

| ChF | 797.25 a | 66.94 a | 15.43 b | 2.96 c |

| Below-ground part (root) | ||||

| Control | 553.60 a | 27.05 a | 17.00 a | 13.77 b |

| INM | 452.77 a | 20.52 b | 17.14 a | 22.68 a |

| ChF | 527.01 a | 26.47 a | 15.06 a | 14.30 b |

| Treatment | Total Phenols (mg GAE/g FW) |

Antioxidant Capacity (mg AAE/g FW) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.993 ± 0.037 b* | 0.094 ± 0.0004 c |

| INM | 1.022 ± 0.009 b | 0.102 ± 0.0008 b |

| ChF | 1.195 ± 0.021 a | 0.106 ± 0.0006 a |

| General Ornamental Interest [2] |

* Special Ornamental Interest [2] |

Agro- Alimentary Interest [11] |

Medicinal Interest [12] |

Feasibility and Readiness Timescale for Sustainable Exploitation (Level II and III Assessments**) |

| Below average | Average | Below average | Low → Above average to high | 43.06% → 66.67% |

| 41.67% | 53.13% / 8.05% / 52.15% / 59.29% | 42.86% | 38.89% → 68.52% | Achievable in long-term → in medium-term |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).