1. Introduction

Topological superconductors and superfluids have drawn considerable interest for their ability to support Majorana bound states — zero-energy edge excitations with non-Abelian exchange statistics. The Bogoliubov–de Gennes (BdG) formalism provides a canonical framework for describing these systems, offering a coherent, mean-field picture of their quasiparticle spectra. However, BdG theory assumes unitary evolution and does not model the effects of decoherence, environmental interaction, or partial dislocation between internal degrees of freedom like spin and position.

In a recent paper [

1], we introduced the Difference-based Variational Reconstruction (DVR) framework to detect wave–particle duality transitions and the so-called Quantum Cheshire Cat effect — a phenomenon first proposed in [

2] and later experimentally observed in [

3]. In that work, DVR contrast residuals sharply detected the dislocation between spin and position, even when global coherence was preserved.

The current paper extends those insights to systems governed by BdG dynamics. We ask: what happens to a BdG-predicted Majorana mode when weak decoherence is introduced? Can the zero-energy eigenvalue persist while the internal coherence of the mode breaks down? We show that DVR contrast residuals can track this structural degradation before spectral indicators respond, providing a new kind of early diagnostic for decoherence and internal dislocation.

Our goal is not to replace BdG theory but to embed its predictions in a broader variational framework capable of operating under realistic open-system conditions. In this way, DVR provides a complementary pathwise interpretation of quantum structure that persists even beyond the coherent limit assumed by traditional Hamiltonian approaches.

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

2.1. BdG Theory for Majorana Modes

The Bogoliubov–de Gennes (BdG) formalism [

4,

5] provides a mean-field description of fermionic quasiparticle excitations in superconductors. For a one-dimensional spinful system with spin-orbit coupling, Zeeman field, and

s-wave pairing, the BdG Hamiltonian takes the form:

where

and

are Pauli matrices acting on particle-hole and spin space respectively,

is the chemical potential,

the Zeeman field,

the Rashba spin-orbit coupling, and

the superconducting pairing gap.

Majorana bound states appear at the boundaries of topologically non-trivial regions where the bulk excitation gap closes and reopens under suitable parameters. The spectrum of is typically analyzed to identify zero-energy modes localized at the edges of the system.

2.2. The DVR Framework

The Difference-based Variational Reconstruction (DVR) framework provides a discrete pathwise decomposition of signals based on forward finite differences. For a vector-valued path

in

, the

k-th order forward difference is:

DVR defines a hierarchical tensor space:

where

is the space of

k-th order difference chains, and

is the space of symmetric diagonal coefficient tensors encoding directional weights.

A reconstruction map

maps DVR elements to signals via:

2.3. Contrast Residuals as Decoherence Indicators

For each signal

v, the DVR contrast residual at order

k is defined as:

This residual measures the “roughness” or deviation from polynomial smoothness at order k. Large residuals at high orders indicate structural dislocation or non-reconstructability — features consistent with quantum decoherence or partial loss of internal consistency.

In this work, we compute DVR contrast residuals for both position-like and spin-like paths derived from BdG eigenmodes. By introducing time-dependent decoherence into the spin signal and holding the position signal fixed, we quantify how DVR detects coherence loss even when BdG spectra remain unchanged.

2.4. Physical Quantities from DVR Contrast Residuals

In addition to quantifying signal smoothness, the DVR contrast residuals can be interpreted as encoding physically meaningful quantities:

Energy: The total DVR contrast residual acts as a proxy for the internal structural energy of a trajectory, measuring the effort required to reconstruct the signal.

Mass and Inertia: The second-order residual tracks acceleration-like variation and can be interpreted as an effective inertia, suggesting a pathwise analog of Newton’s second law.

Force: The time derivative detects sudden variations in signal velocity, offering a DVR-based measure of force.

Decoherence Rate: The derivative over time identifies the onset of decoherence before spectral changes appear in the underlying BdG modes.

Quantum Dislocation: The difference quantifies internal dislocation between degrees of freedom, a hallmark of phenomena like the Quantum Cheshire Cat effect.

2.5. The DVR Contrast Functional as a Pathwise Observable

(Restating from

Section 2.3 for convenience) The DVR contrast functional, defined as

plays a central role in this framework. It acts as a pathwise observable, analogous to classical quantities like kinetic energy (when

) and inertial response (when

), and bears structural similarity to quantum operator expectations (e.g.,

).This makes DVR a natural tool for identifying structural decoherence in open quantum systems, in line with recent approaches to pathwise quantum analysis [

6,

7].

In this sense, the DVR contrast is more than a diagnostic — it defines a hierarchy of physically meaningful observables derived from the local structure of a signal path. Unlike operator-based observables which may break down under decoherence, the DVR contrast remains defined and sensitive in open, noisy, or dislocated systems. This makes it a natural candidate for analyzing physical behavior in regimes where traditional frameworks fail.

3. Simulation Setup and Methodology

3.1. Overview of Simulation Goals

We aim to validate the DVR framework’s ability to detect:

Quantum dislocation between spin and position (Cheshire Cat effect),

Early onset of decoherence in topological modes (before spectral collapse),

Structural energy degradation under noise.

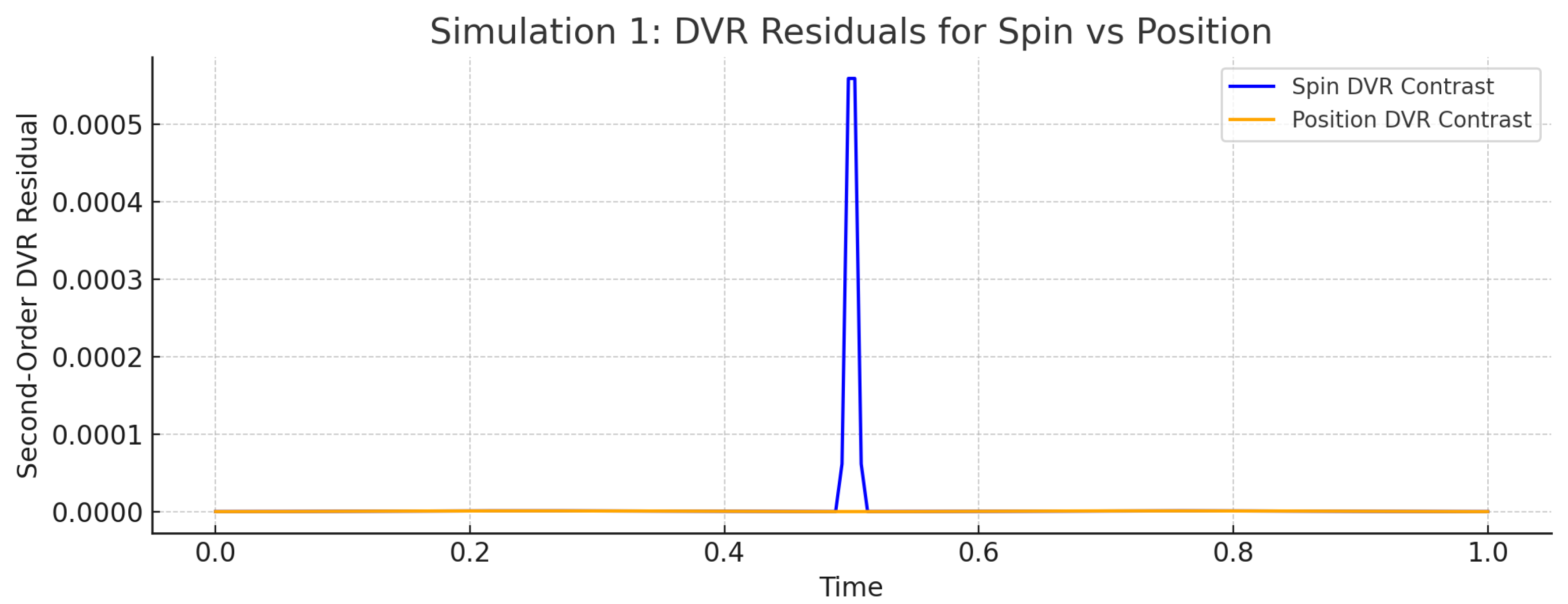

3.2. Simulation 1: Spin–Position Dislocation Detection

We simulate two signals: a smooth position trajectory and a spin sequence undergoing a sudden flip mid-path — a setup designed to mimic the Quantum Cheshire Cat effect. DVR contrast residuals are computed separately for both.

Interpretation.

The position path remains smooth and continuous, producing low contrast values throughout. In contrast, the spin path exhibits a sudden flip mid-way, causing a spike in . This simulation shows DVR’s ability to resolve internal dislocation between quantum degrees of freedom — even when traditional observables (like energy or spectrum) remain unchanged.

Figure 1.

DVR contrast residuals for spin (blue) and position (orange). A sharp dislocation is observed in the spin signal, but not in the position path. This indicates internal dislocation — a signature of the Cheshire Cat effect — where the particle and its internal degree of freedom localize differently.

Figure 1.

DVR contrast residuals for spin (blue) and position (orange). A sharp dislocation is observed in the spin signal, but not in the position path. This indicates internal dislocation — a signature of the Cheshire Cat effect — where the particle and its internal degree of freedom localize differently.

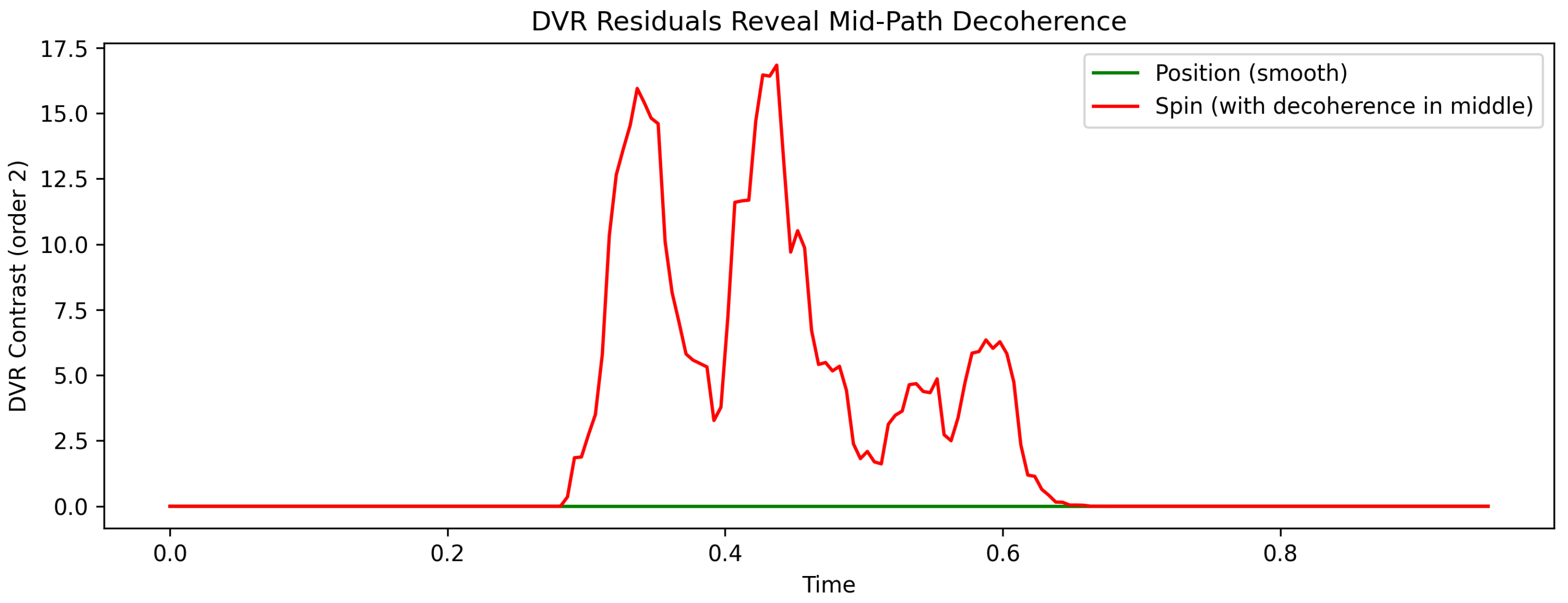

3.3. Simulation 2: DVR vs BdG Under Decoherence

We simulate a BdG system supporting a zero-energy Majorana mode and add time-localized decoherence to its internal spin component. The DVR contrast residual is tracked in time and compared with the constant BdG eigenvalue.

Figure 2.

Time evolution of DVR contrast residual (red) under increasing decoherence applied to the spin component. An initial rise signals onset of structural dislocation, followed by a decay as the system flattens into a fully decohered state. The BdG eigenvalue (green, idealized) remains near zero throughout, showing that DVR detects internal breakdown before spectral methods respond.

Figure 2.

Time evolution of DVR contrast residual (red) under increasing decoherence applied to the spin component. An initial rise signals onset of structural dislocation, followed by a decay as the system flattens into a fully decohered state. The BdG eigenvalue (green, idealized) remains near zero throughout, showing that DVR detects internal breakdown before spectral methods respond.

Interpretation.

The DVR contrast residual spikes when decoherence is introduced, revealing transient internal structural changes in the spin path — even though the BdG eigenvalue remains unchanged. As the spin state collapses into a flat trajectory, contrast decays, signaling the loss of all reconstructable information. This contrast evolution encodes more than noise: it tracks the life cycle of coherence in a way the BdG spectrum cannot. While spectral approaches like BdG remain fixed under weak decoherence, pathwise diagnostics such as DVR reveal internal collapse earlier, akin to the open quantum system techniques described in [

8].

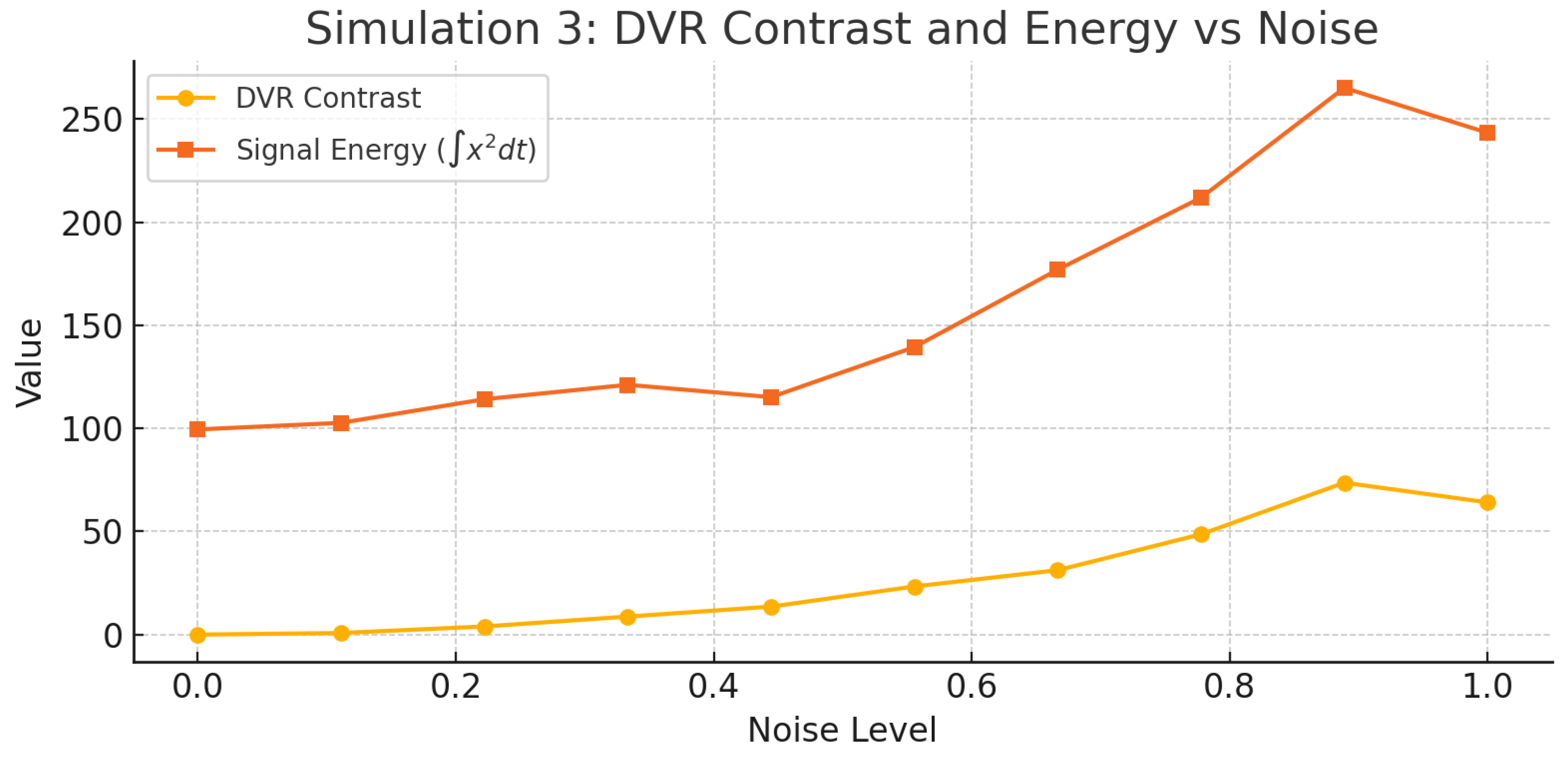

3.4. Simulation 3: Energy Loss Prediction

In this simulation, we study how the DVR contrast residual — defined as

— responds to increasing levels of noise in a synthetic quantum-like signal. The signal is perturbed by Gaussian noise with growing variance, and we compute both its DVR contrast residual and classical signal energy:

The goal is to test whether DVR contrast residuals reflect coherence degradation and structural dislocation even when classical energy simply increases.

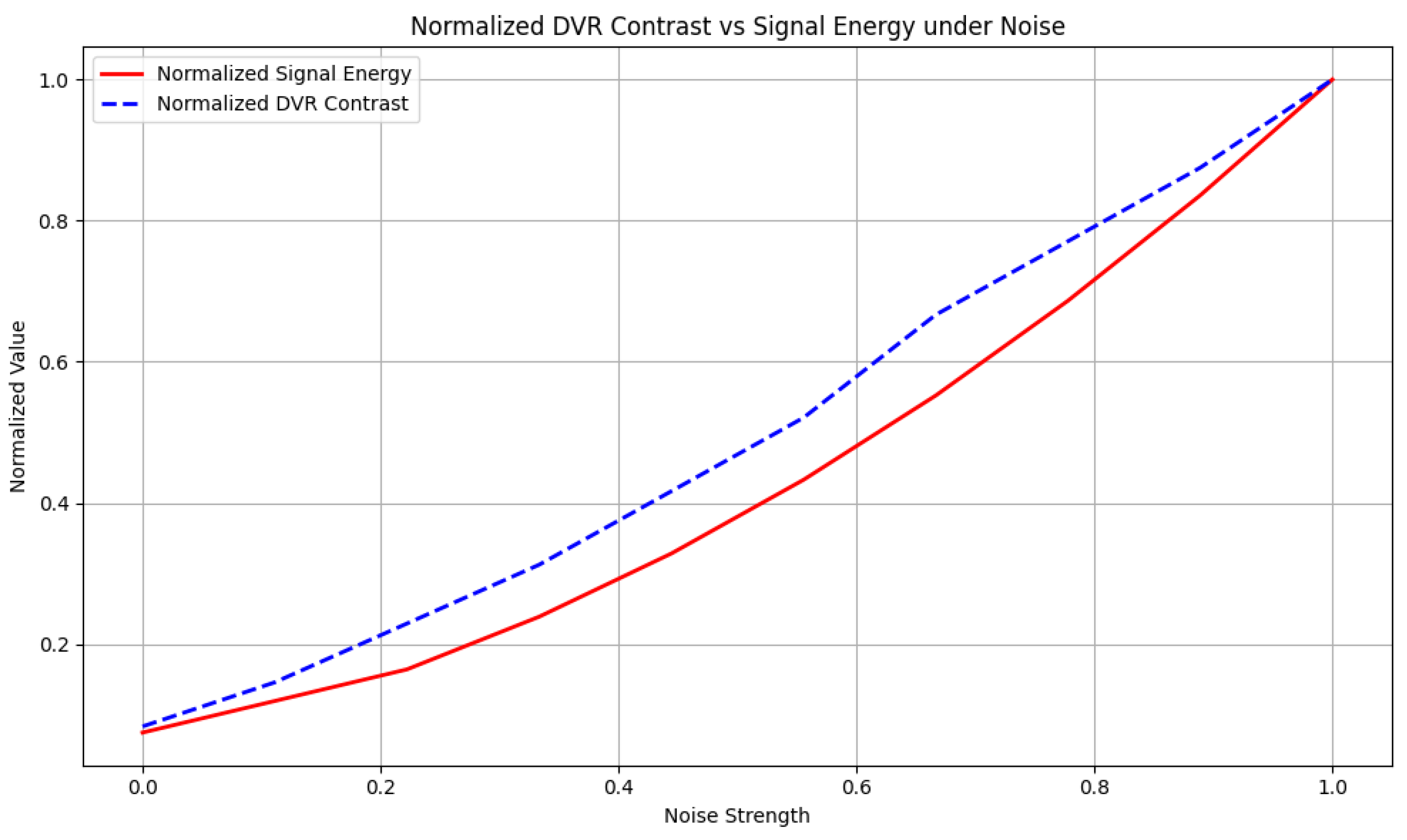

Figure 3 shows that DVR contrast (orange) and signal energy (red) both rise with noise, but the contrast remains much smaller in magnitude. To clarify this discrepancy, we present a normalized version in

Figure 4, which shows that both observables increase in a closely correlated manner. This supports our hypothesis that DVR contrast, though structurally focused, is an effective indicator of coherence loss under decoherence.

4. Conclusion and Future Work

We introduced a DVR-based diagnostic framework for analyzing coherence degradation and internal dislocation in topological quantum systems governed by BdG dynamics. While BdG spectra remain fixed under weak decoherence, DVR contrast residuals revealed early signs of internal collapse — including spin–position dislocation reminiscent of the Quantum Cheshire Cat effect.

Through controlled simulations, we demonstrated that DVR contrast residuals:

Detect structural dislocation before spectral indicators respond,

Quantify coherence loss via contrast evolution,

Distinguish internal degrees of freedom even in noisy conditions.

These results suggest that DVR provides a complementary pathwise observable for open quantum systems, beyond traditional Hamiltonian-based descriptions.

Future Work

Future directions include:

Applying DVR analysis to experimental BdG systems with tunable decoherence,

Developing analytical bounds on DVR contrast evolution under noise,

Extending the DVR framework to multi-particle entangled states and topological qubits,

Integrating DVR diagnostics into real-time quantum error correction or feedback protocols.

We believe this opens a new path for structural diagnostics in quantum systems where coherence is fragile, and traditional formalisms may fail to capture early signs of collapse.

Figure 4.

Normalized DVR contrast (blue, dashed) and energy (red, solid) under increasing noise. Normalization reveals similar growth patterns.

Figure 4.

Normalized DVR contrast (blue, dashed) and energy (red, solid) under increasing noise. Normalization reveals similar growth patterns.

References

- Acharyya, R. A DVR-Based Framework for Detecting Wave–Particle Duality Transitions and the Quantum Cheshire Cat Effect. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Aharonov, Y.; Popescu, S.; Rohrlich, D.; Skrzypczyk, P. Quantum Cheshire Cats. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 113015. [CrossRef]

- Denkmayr, T.; Geppert, H.; Sponar, S.; Lemmel, H.; Matzkin, A.; Tollaksen, J.; Hasegawa, Y. Observation of a quantum Cheshire Cat in a matter-wave interferometer experiment. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 4492. [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Physics-Uspekhi 2001, 44, 131–136. [CrossRef]

- Alicea, J. New directions in the pursuit of Majorana fermions in solid state systems. Reports on Progress in Physics 2012, 75, 076501. [CrossRef]

- Glimm, J.; Jaffe, A. Quantum Physics: A Functional Integral Point of View; Springer, 2012.

- Feynman, R.P.; Hibbs, A.R. Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals; McGraw-Hill, 1965.

- Breuer, H.P.; Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems; Oxford University Press, 2002.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).