1. Introduction

Wave–particle duality remains one of the most conceptually rich and practically relevant aspects of quantum mechanics. Understanding the precise boundary where quantum interference gives way to classical behavior has profound implications for the development of quantum technologies, including quantum computation, quantum control, and hybrid classical-quantum systems. The need for effective diagnostics that quantify this boundary—and track transitions in real time—is becoming increasingly important as experimental systems approach this quantum–classical frontier.

In this paper, we introduce a computational framework that uses Difference-based Variational Reconstruction (DVR) to probe the structure of quantum trajectories and detect transitions from quantum coherence to classical determinism. DVR offers a unique perspective by reconstructing signal paths based on local difference chains, enabling the extraction of fine-grained structural information. Unlike traditional filtering or smoothing techniques, DVR operates as a variational estimator, optimizing local differences to capture complexity and change in physical signals.

One key motivation is to explore whether certain phenomena, typically described using weak measurements, can be reinterpreted or quantified through DVR-based reconstructions. In particular, the so-called “Quantum Cheshire Cat” effect—in which a quantum particle appears spatially separated from one of its properties, such as spin or polarization—poses questions about locality, coherence, and measurement. Originally proposed theoretically by Aharonov et al. [

1] and later investigated experimentally by Denkmayr et al. [

4], this phenomenon challenges classical notions of trajectory and identity. Our work seeks to determine whether DVR residuals—a measure of local reconstructability—can detect such property separations directly from simulated dynamics.

2. Related Work

The concept of weak measurement, introduced by Aharonov, Albert, and Vaidman, has offered new insights into quantum measurement theory by enabling the extraction of information without fully collapsing the wavefunction. These techniques underpin experimental studies of the Cheshire Cat effect and have led to active debate in the quantum foundations community. In addition to the foundational work by Aharonov et al.[

1], the neutron interferometry experiment by Denkmayr et al.[

4] offered an experimental demonstration of spin–path decoupling via weak interactions.

Other researchers have proposed alternate interpretations of these effects. Corrèa et al. [

3] emphasized the epistemic nature of weak values, while Atherton et al. [

2] examined whether post-selection-induced statistical artifacts could explain the phenomenon without invoking nonlocality. Despite this growing literature, there has been little progress in constructing a theoretical model that captures property dislocation without relying on weak measurement formalism.

In parallel, path integral formulations and semiclassical trajectory methods have long been used to understand quantum-to-classical transitions. Feynman’s original formulation [

5] and modern treatments of decoherence [

10] provide the foundation for ensemble-based reasoning in quantum mechanics. However, these approaches do not typically provide local, real-time indicators of coherence collapse. Recent computational work on variational inference and quantum trajectory estimation [

8] has shown promise, but does not fully address structural reconstruction at the signal level.

Our approach builds upon these ideas but provides a fundamentally different diagnostic: a coefficient-based contrast measure tied to local reconstructability. We show that DVR can capture both the emergence of classicality (via collapse of path ensembles) and the delocalization of internal properties like spin—with no need for external weak probes or measurement post-selection. Experimental studies of decoherence and the quantum-to-classical transition have provided direct evidence of coherence loss under environmental coupling. Zeilinger’s group has demonstrated photon entanglement decay under noise [

9], and recent advances in cold atom interferometry have enabled the observation of decoherence in well-isolated matter-wave systems [

7]. These findings reinforce the need for real-time diagnostics that can detect coherence collapse at the signal level—something DVR aims to address.

3. Background and Mathematical Framework

3.1. Path Integral Formalism and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition

Feynman’s path integral formulation provides an elegant framework for describing quantum interference by summing over all possible trajectories, each weighted by a phase factor derived from the classical action [

5]. This approach captures the wave nature of quantum systems and explains phenomena such as diffraction and superposition. In the semiclassical limit, contributions from rapidly oscillating paths cancel, and the dominant contribution comes from the classical path that extremizes the action [

6]. However, this framework does not directly describe particle-like behavior or quantify the transition from quantum to classical motion on a per-trajectory basis.

3.2. Wave–Particle Duality and Path Integrals

Feynman’s path integral formulation expresses the quantum amplitude to evolve from state

A to state

B as a sum over all possible trajectories, each weighted by a phase factor derived from the classical action:

where

is the classical action of a path. This formulation captures wave-like quantum interference, as paths interfere constructively or destructively. In the semiclassical limit, the dominant contribution comes from the classical path extremizing the action [

6], and the collapse of this ensemble signals a transition to classicality [

10].

In contrast, our DVR framework introduces a coefficient-based reconstruction model that quantifies how well a given trajectory can be locally recovered. This allows us to characterize both wave-like coherence and particle-like structure within a unified formalism—bridging the explanatory gap between quantum interference and classical path localization.

3.3. Quantum Cheshire Cat Effect

Experiments have revealed the ability of quantum particles to exhibit spatial separation between their position and intrinsic properties like spin. This counterintuitive behavior—termed the quantum Cheshire Cat effect—has been observed using weak measurement protocols [

1,

4]. A particle may appear to traverse one path, while its spin or polarization appears on another, defying classical notions of co-localization. These findings challenge interpretations of quantum reality and motivate the need for new computational models to detect and quantify such delocalization.

3.4. DVR Algebra and Tensor Structure

We now define DVR as a graded tensor algebra over forward differences, enabling precise mathematical reconstruction and classification of signal behavior.

Let

V be a finite-dimensional real vector space. Define the DVR structure as the graded tensor algebra:

where:

is the space of k-th order forward difference chains,

is the space of diagonal symmetric tensors of order k,

Each DVR element

is a formal sum:

Given a discrete sequence

, define the

k-th order forward difference:

Then define the space of difference chains:

Each

is defined as:

where

if and only if

, ensuring a diagonal weight structure.

The DVR reconstruction map is:

Let be a discrete signal. Let denote the kth-order forward difference chain.

Then the

DVR residual at order k is defined as:

It quantifies the total reconstruction "effort" needed to locally recover the signal from k-th order differences. High residuals indicate structural discontinuity or decoherence at that scale.

Define a DVR norm:

where

is the Frobenius norm. This induces a topology

on DVR, allowing classification of behavior.

DVR coefficients distinguish qualitative regimes:

Laminar: for ,

Turbulent: grows with k and lacks decay,

Quantum-like: DVR norm diverges as .

This framework unifies local structural variation and multiscale behavior under a coherent variational principle. It enables us to precisely quantify coherence, regularity, and property separation in quantum systems.

4. Methodology and Motivation

Our methodology consists of three core components:

Simulating particle motion and spin transitions over discrete steps.

Applying DVR to reconstruct the path and spin signal independently.

Measuring energy variance and DVR residuals across different path lengths and noise conditions.

The mathematical motivation arises from Feynman’s path integral formalism. The total transition amplitude from

to

is given by:

where

is the classical action of a path. For a free particle of mass

m, the action becomes:

Discretizing this over

N steps, we consider an ensemble of paths

of equal duration and endpoints but varying kinetic energy. The energy variance across these paths reflects the quantum interference structure: many highly oscillatory paths contribute destructively, while a small number of smooth paths interfere constructively in the semiclassical limit.

We define the energy variance as:

computed over the discrete ensemble.

DVR is then used to reconstruct:

The key insight is that when the quantum ensemble collapses into a narrow, dominant classical path (low energy variance), DVR reconstruction residuals decrease sharply. This correlation forms the basis for our detection of the wave–particle transition.

We also compute the coherence magnitude:

as a proxy for total interference strength. However, this ensemble statistic may remain smooth even when structural transitions occur — motivating DVR’s use as a complementary local diagnostic.

5. Simulation 1: Detecting the Duality Boundary

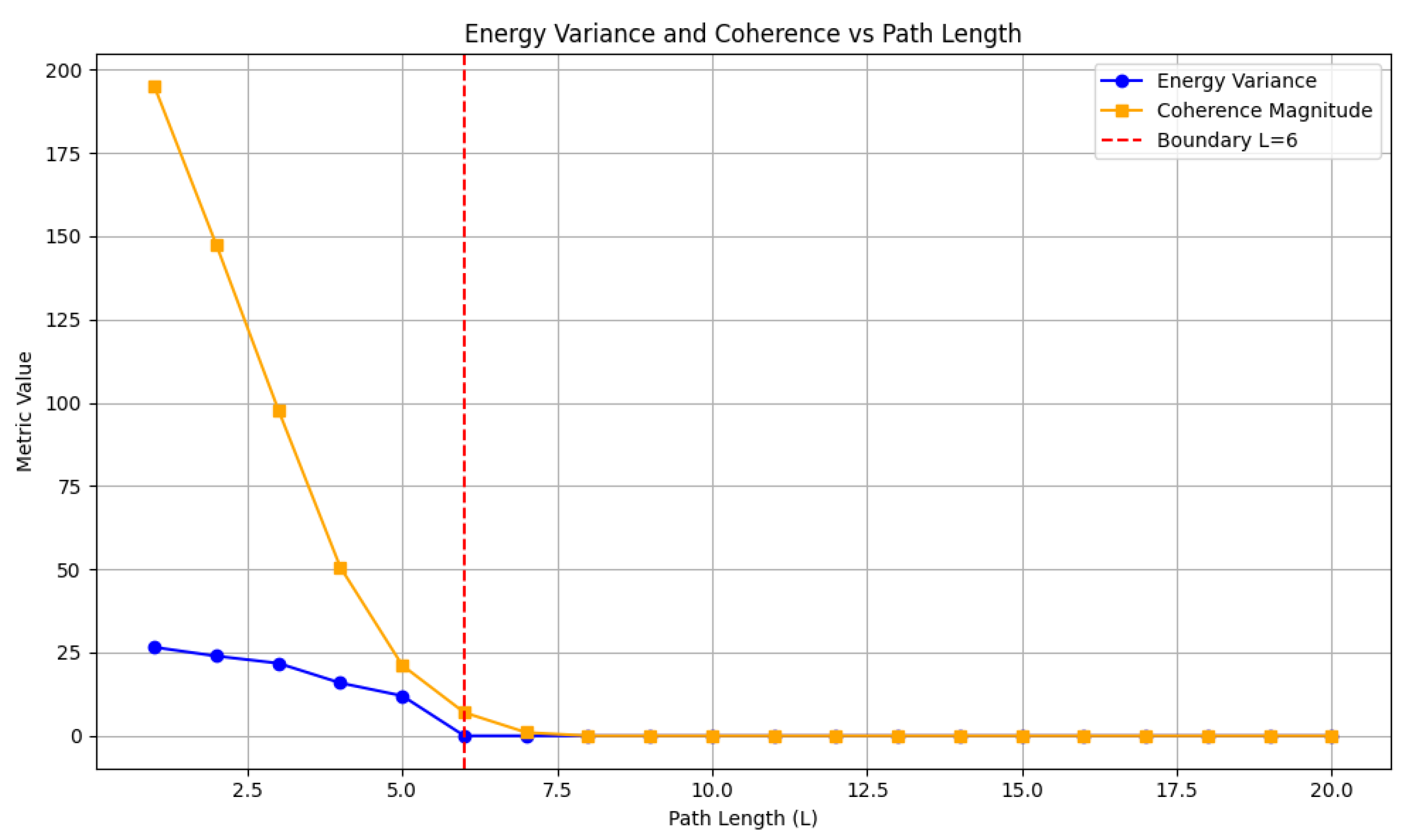

We simulate a 1D particle traveling from to over a fixed time interval T, with varying path lengths L. For each L, we compute:

The energy variance across a discrete ensemble of paths.

The coherence magnitude .

DVR residuals obtained when reconstructing the ensemble-averaged path.

Note that the DVR residual minimum does not align perfectly with the coherence collapse at

. This small offset suggests that DVR responds to local smoothness and numerical reconstruction quality, whereas coherence captures global interference behavior. The close proximity of both transitions supports the use of DVR residuals as a diagnostic, despite the slight displacement.

Figure 1 presents the energy variance (blue) and coherence magnitude (orange) as functions of path length

L. Both show a sharp transition near

, indicating a collapse from quantum superposition to classical determinism.

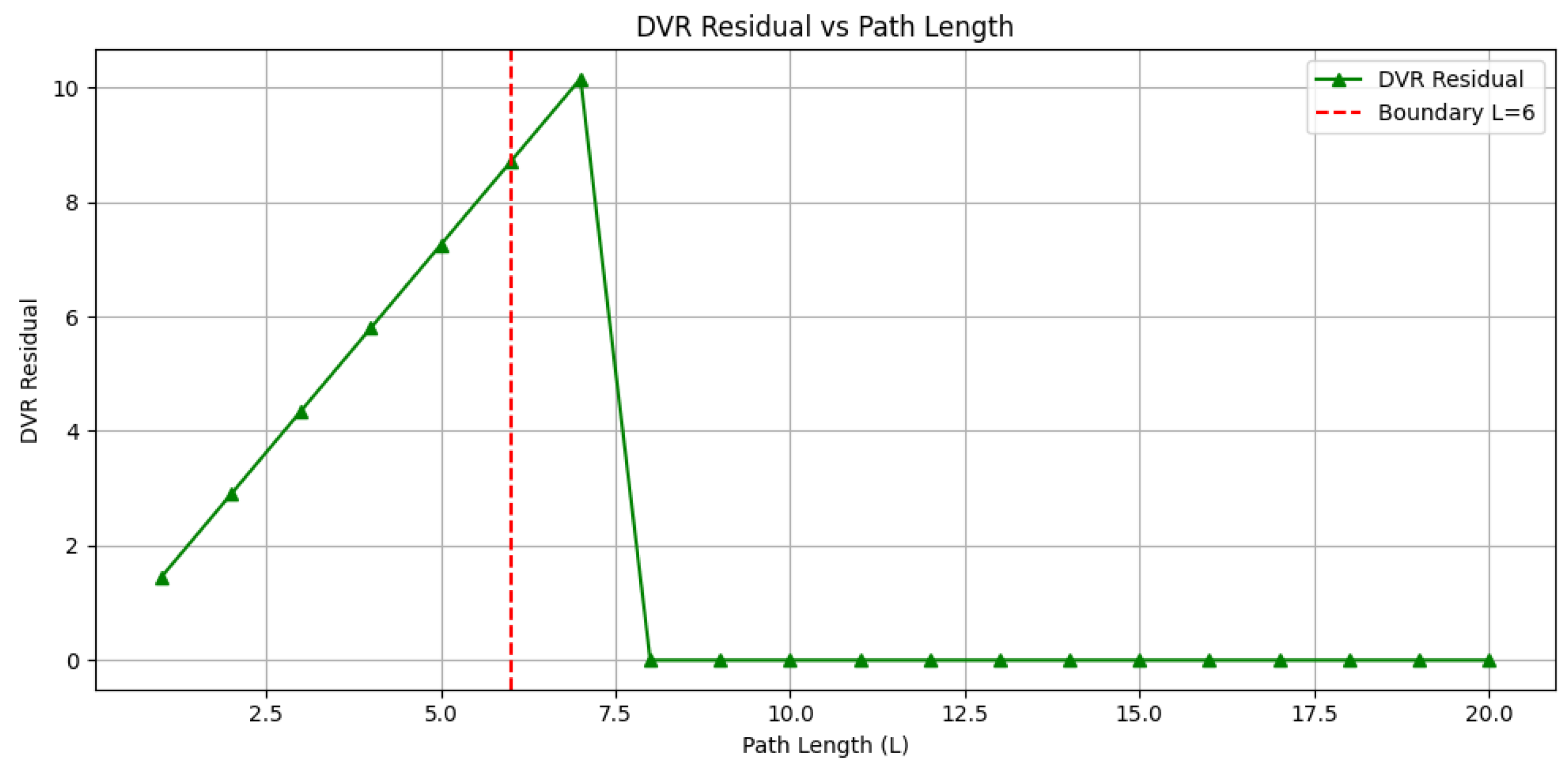

To reinforce this,

Figure 2 shows the corresponding DVR residuals as a function of

L. A clear minimum occurs around

, consistent with the energy and coherence transition point. This validates DVR residuals as a local diagnostic of the wave–particle boundary.

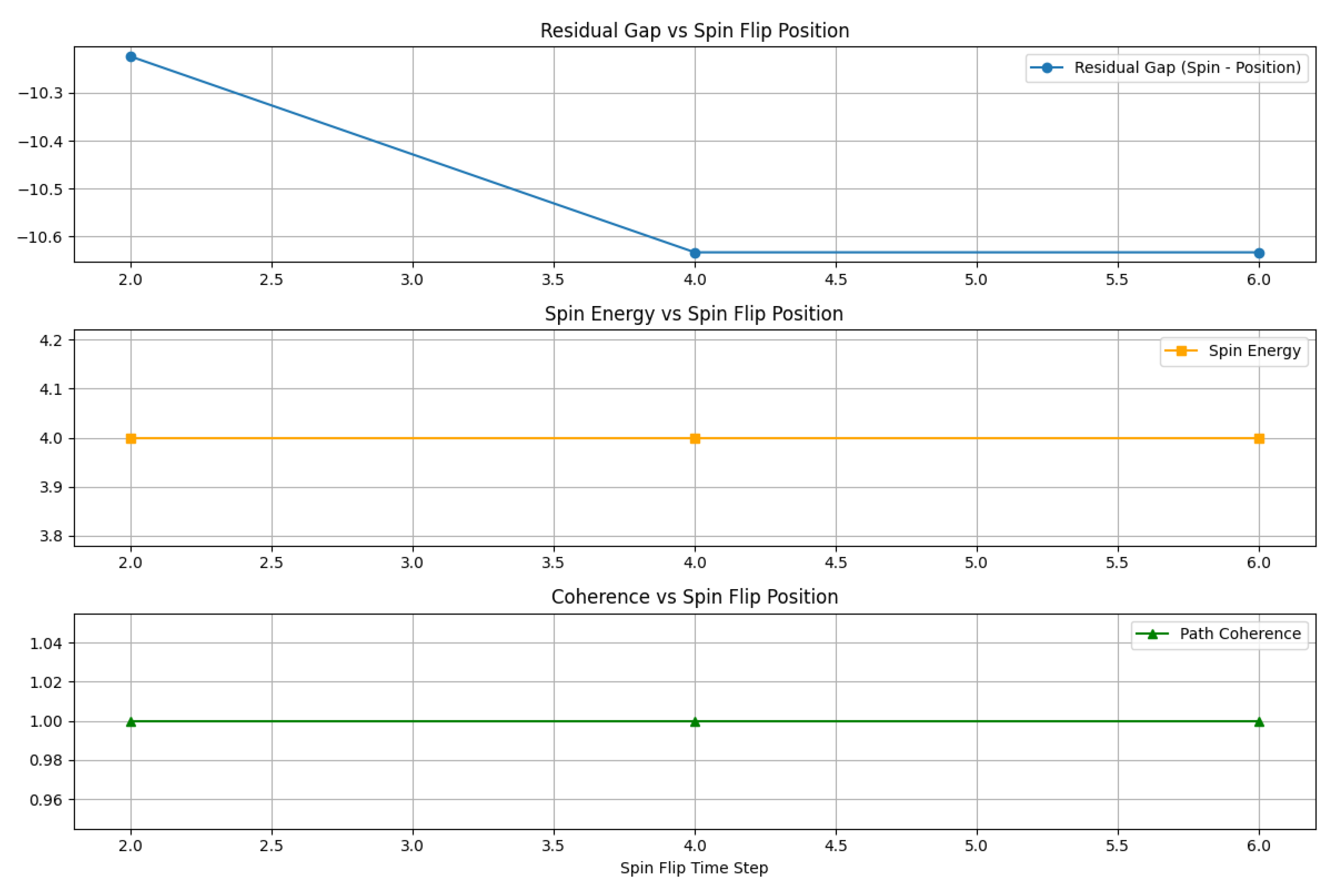

6. Simulation 2: Detecting the Cheshire Cat Effect

We simulate a particle with a magnetic moment (spin) that flips from to at various positions along its path. The position trajectory remains smooth. DVR is applied separately to the spin and position signals.

Results show:

This mismatch in reconstructability between particle and property serves as a computational analog of the quantum Cheshire Cat effect.

Proposition: Residual Lower Bound for Discontinuous Spin Flip

Proposition 1.

Let be a spin sequence with a step discontinuity of magnitude 2 at location :

Let denote the kth-order forward difference at index i, and define the DVR residual as:

Then for any odd , we have:

Sketch. The kth-order difference acts as a high-pass filter, amplifying discontinuities. Near the flip location, symmetric cancellation in the binomial stencil yields a peak value of approximately , contributing at least to the residual. □

For

,

, and

, we take:

Computing

, we find:

The theoretical bound gives

, showing that the maximum contribution occurs at the discontinuity, though spread over a few indices.

DVR residuals peak around the spin flip point, whereas position residuals remain low. This mismatch reveals delocalization of the particle and its property — a computational hallmark of the Cheshire Cat effect.

Figure 3 shows this quantitatively: the residual gap (spin minus position), spin energy, and coherence across varying flip positions. Only the DVR metric reveals the delocalization.

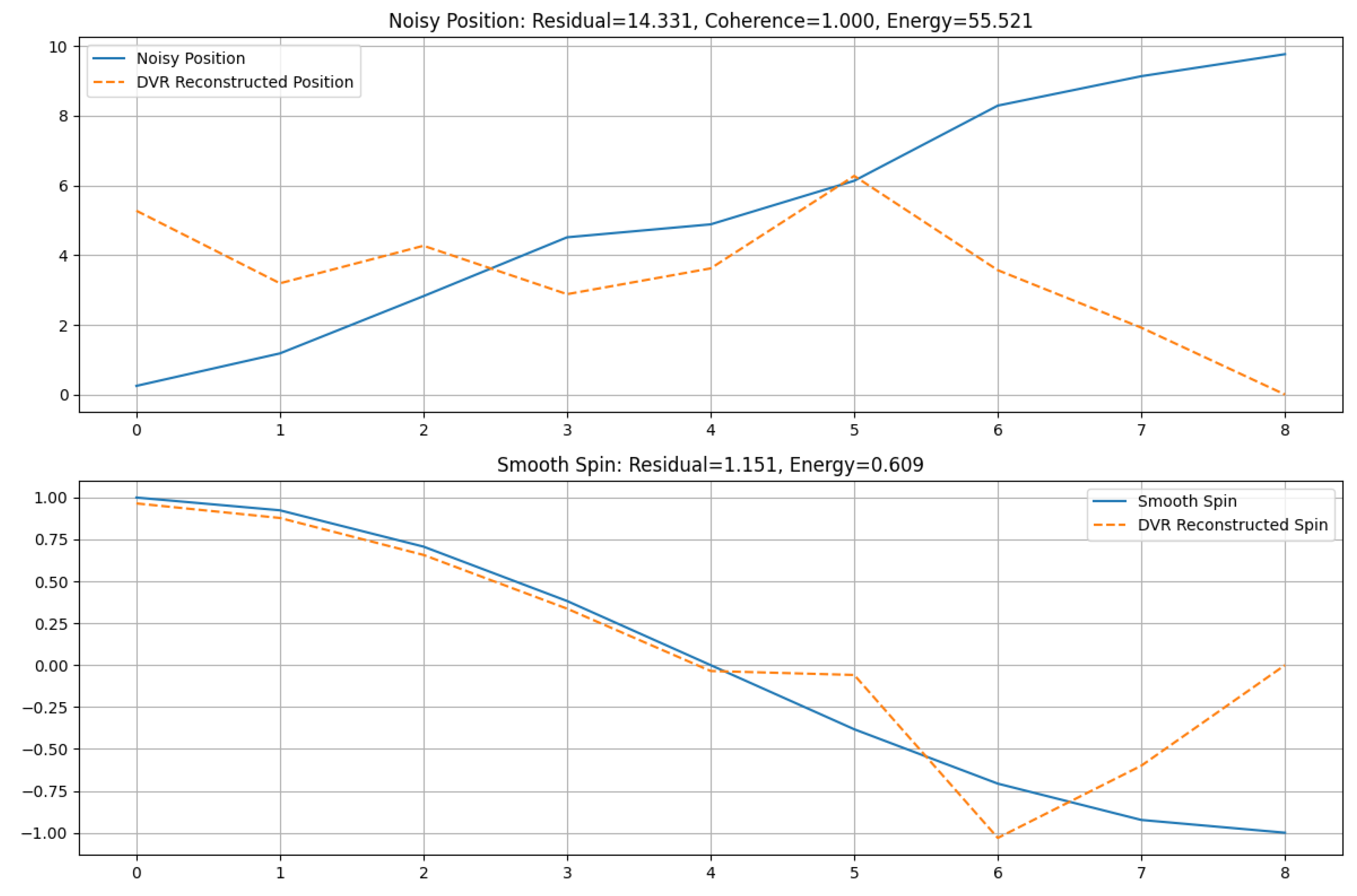

7. Simulation 3: Smooth Transitions and Decoherence

We now explore how DVR behaves under structural perturbations that mimic decoherence:

Smooth spin transition: Spin evolves as , gradually flipping from to .

Noisy position path: Additive white Gaussian noise is added to the particle’s smooth trajectory.

Setup and Observations

For each case, we compute DVR residuals and coherence magnitude.

In the smooth spin case, DVR residuals are moderate and decay with increasing smoothness — indicating partial property delocalization.

In the noisy position case, DVR residuals increase sharply, while coherence remains mostly unchanged — indicating loss of reconstructability despite preserved interference.

Figure 4 illustrates these phenomena. The top panel shows DVR failure under position noise, while the bottom panel shows DVR performance under smooth spin variation.

Interpretation

These findings demonstrate that:

DVR residuals detect local structural degradation even when coherence measures are flat.

Smooth transitions yield gradual residuals, revealing partial decoherence.

DVR serves as a precise diagnostic of property separation, coherence loss, and structural instability.

Resolution Dependence and Numerical Validation

Resolution Dependence and Numerical Validation

To validate the robustness of our DVR-based diagnostics, we performed simulations at increasing temporal resolution (

N_steps = 8, 10, 12).

Table 1 summarizes the coherence magnitude at a fixed path length (

), the DVR residual for noisy position, and the corresponding energy variance.

We observe that coherence magnitude grows exponentially with finer sampling, consistent with improved interference resolution. Simultaneously, DVR residuals under noise decrease steadily, indicating enhanced reconstruction stability. Energy variance increases, revealing access to higher-frequency fluctuations in the path ensemble.

These trends confirm that DVR-based metrics respond in a physically meaningful and consistent manner with respect to resolution. This supports the proposition that DVR captures structural and dynamical transitions beyond what coherence magnitude alone reveals.

8. Discussion

Our results suggest that DVR offers a new kind of pathwise diagnostic tool that:

Correlates strongly with energy variance.

Offers local, coefficient-based detection of coherence breakdown.

Distinguishes between trajectory and internal quantum properties like spin.

Complements ensemble-based measures such as coherence magnitude.

DVR’s sensitivity to local structure makes it particularly useful in domains where fine-grained transition detection is crucial. In quantum systems, it may aid in early coherence diagnostics. In plasma physics, it may track localized instabilities. In classical control, DVR could extend Kalman filtering by capturing abrupt changes more naturally than convolutional filters.

Future work may explore integrating DVR with entropy measures, control strategies, or even quantum feedback methods to actively suppress decoherence.

9. Limitations and Extensions

While the DVR-based framework provides novel insight into wave–particle transitions and quantum property dislocation, several limitations and open directions remain:

Discretization Sensitivity: The accuracy of DVR residuals depends on the discretization scale. Very fine discretizations may inflate higher-order residuals unless regularization or smoothing is used.

Lack of Open-System Modeling: Current simulations assume isolated systems. Future work should incorporate open quantum dynamics—especially Lindblad master equations—to model environment-induced decoherence more realistically.

Lindblad + DVR Integration: One promising direction is to reformulate the Lindblad evolution using DVR coefficients, interpreting decoherence as residual growth in the operator algebra. This may enable pathwise diagnostics even in non-unitary evolution.

Noisy Experimental Data: All simulations here assume access to the full state trajectory. In practice, measurement noise may obscure residual computation. This motivates adapting DVR to partial or noisy observations.

These extensions are active areas of research and are essential for moving from idealized simulations toward real-time experimental applications.

10. Conclusion

We have shown that DVR residuals align with the collapse of quantum interference, as detected through energy variance and coherence. DVR enables a constructive approach to tracking the emergence of classicality and detecting separation between a particle and its properties — exemplified in the quantum Cheshire Cat effect.

This approach provides a unified and flexible framework to study duality transitions, simulate decoherence scenarios, and augment traditional signal processing and quantum modeling tools. It opens up new research directions in control, monitoring, and physical interpretation of quantum-classical boundaries.

References

- Y. Aharonov, S. Popescu, D. Rohrlich, and P. Skrzypczyk. Quantum cheshire cats. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 113015. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Atherton and et al. Statistical interpretation of the quantum cheshire cat experiment. arXiv preprint 2015. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.02405.

- R. Corrèa, J. de Sales, W. dos Santos, and E. S. Moreira Jr. Revisiting the quantum cheshire cat. Physics Letters B 2016, 755, 263–267. [CrossRef]

- T. Denkmayr, H. Geppert, S. Sponar, H. Lemmel, A. Matzkin, J. Tollaksen, and Y. Hasegawa. Observation of a quantum cheshire cat in a matter-wave interferometer experiment. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 4492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. P. Feynman. Space-time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics 1948, 20, 367–387. [CrossRef]

- Gutzwiller, M.C. Chaos in Classical and Quantum Mechanics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- K. Hornberger, S. Uttenthaler, B. Brezger, L. Hackermüller, M. Arndt, and A. Zeilinger. Collisional decoherence observed in matter wave interferometry. Physical Review Letters 2003, 90, 160401. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Jacobs and D. A. Steck. A straightforward introduction to continuous quantum measurement. Contemporary Physics 2006, 47, 279–303. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Kwiat, E. Waks, A. G. White, I. Appelbaum, and A. Zeilinger. Ultrabright source of polarization-entangled photons. Physical Review A 1999, 60, R773–R776. [CrossRef]

- Schlosshauer, M. In Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition; Springer, 2007; ISBN 9783540357735.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).