Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

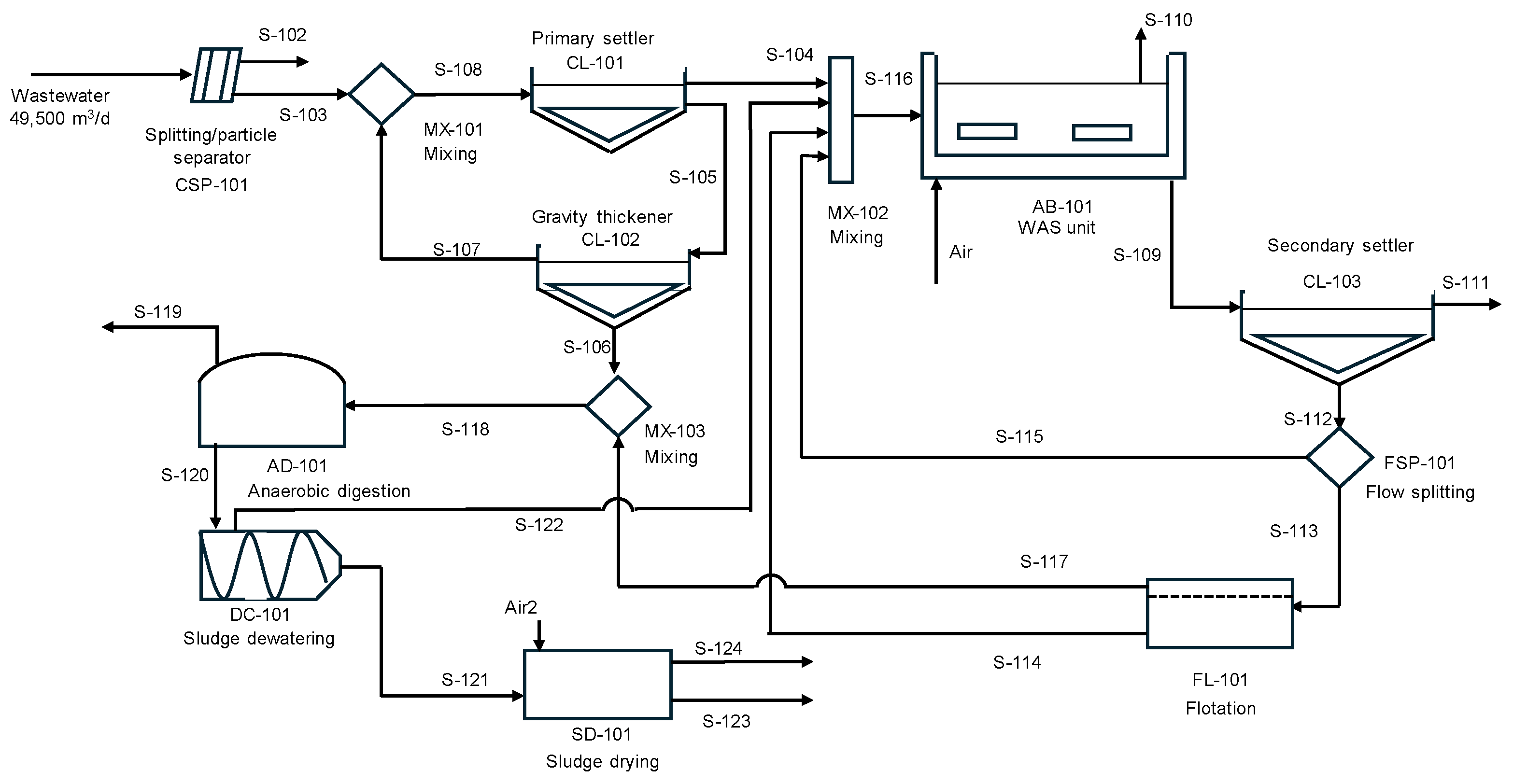

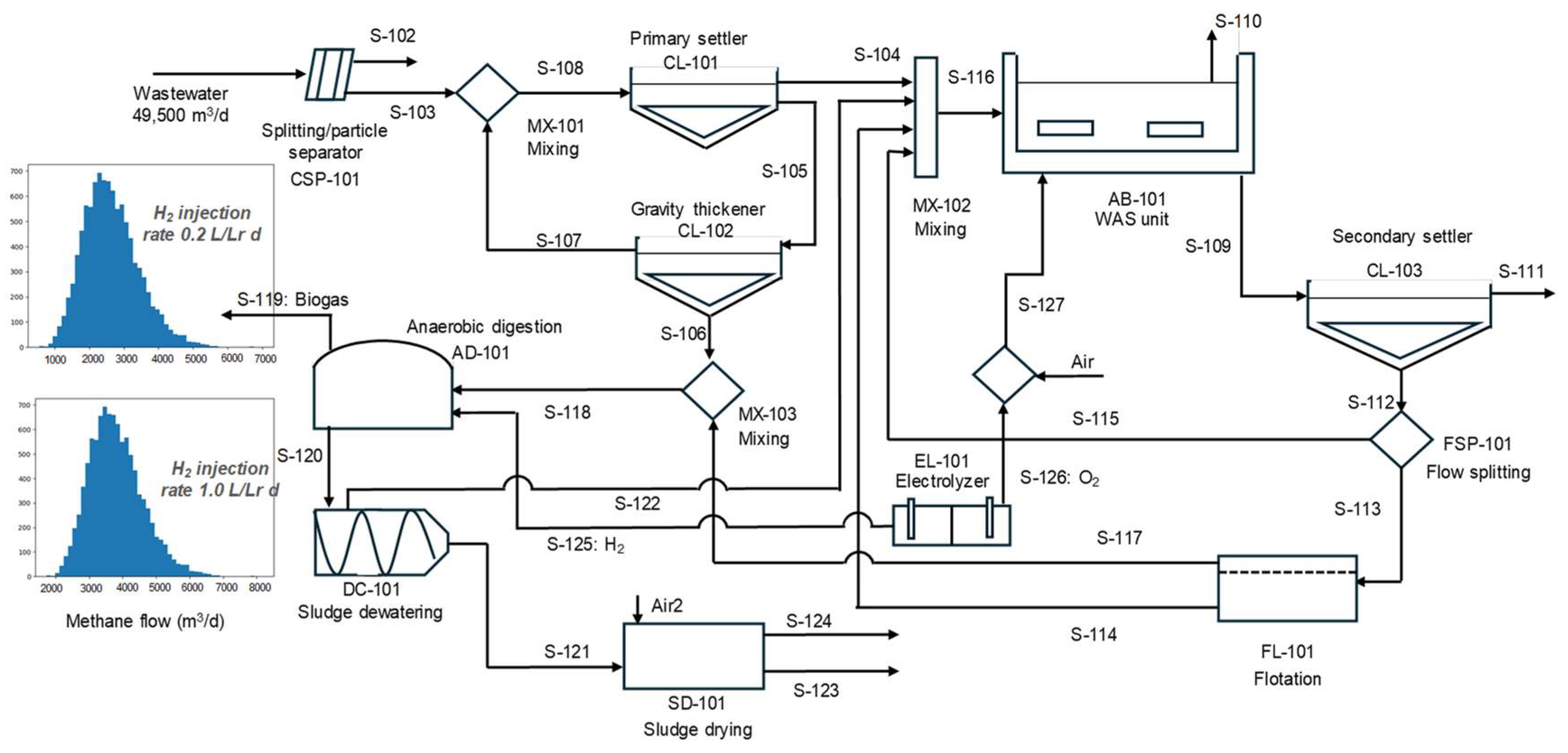

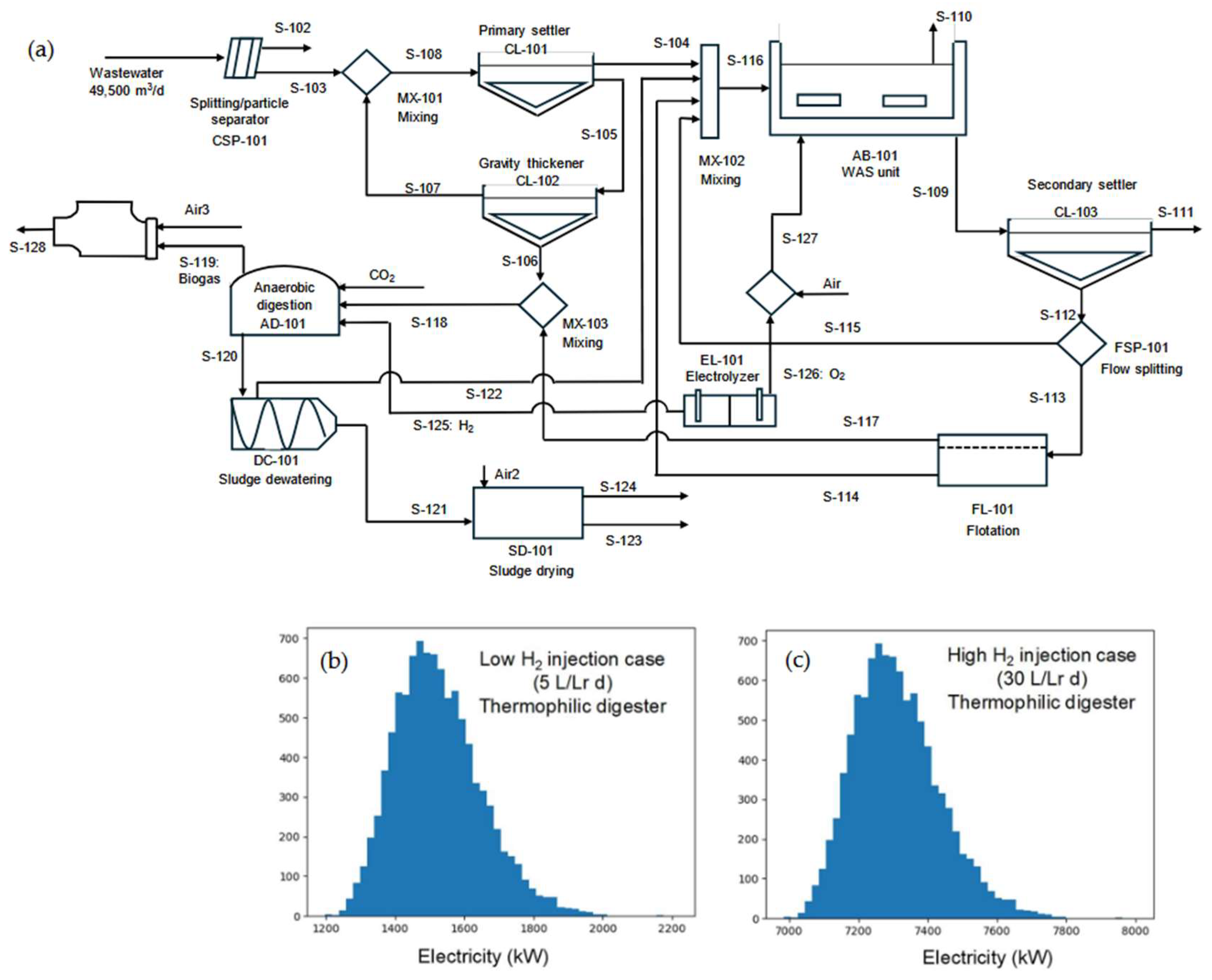

2. Materials and Methods

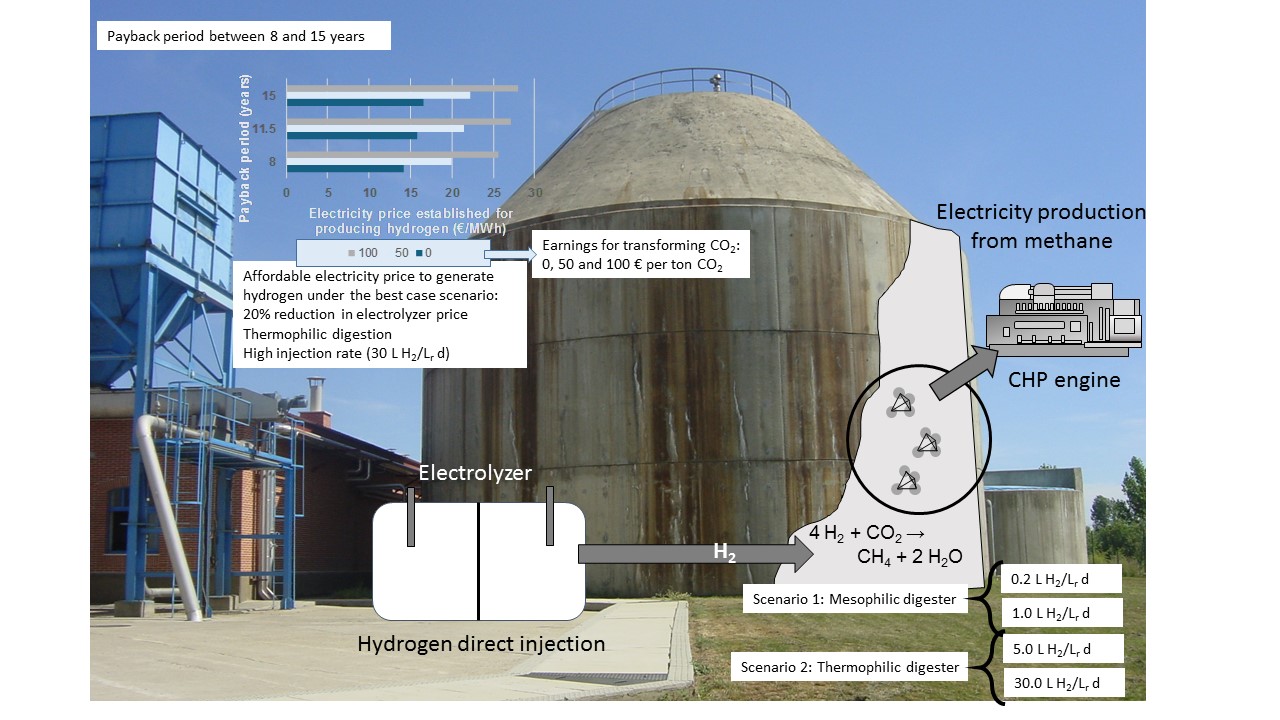

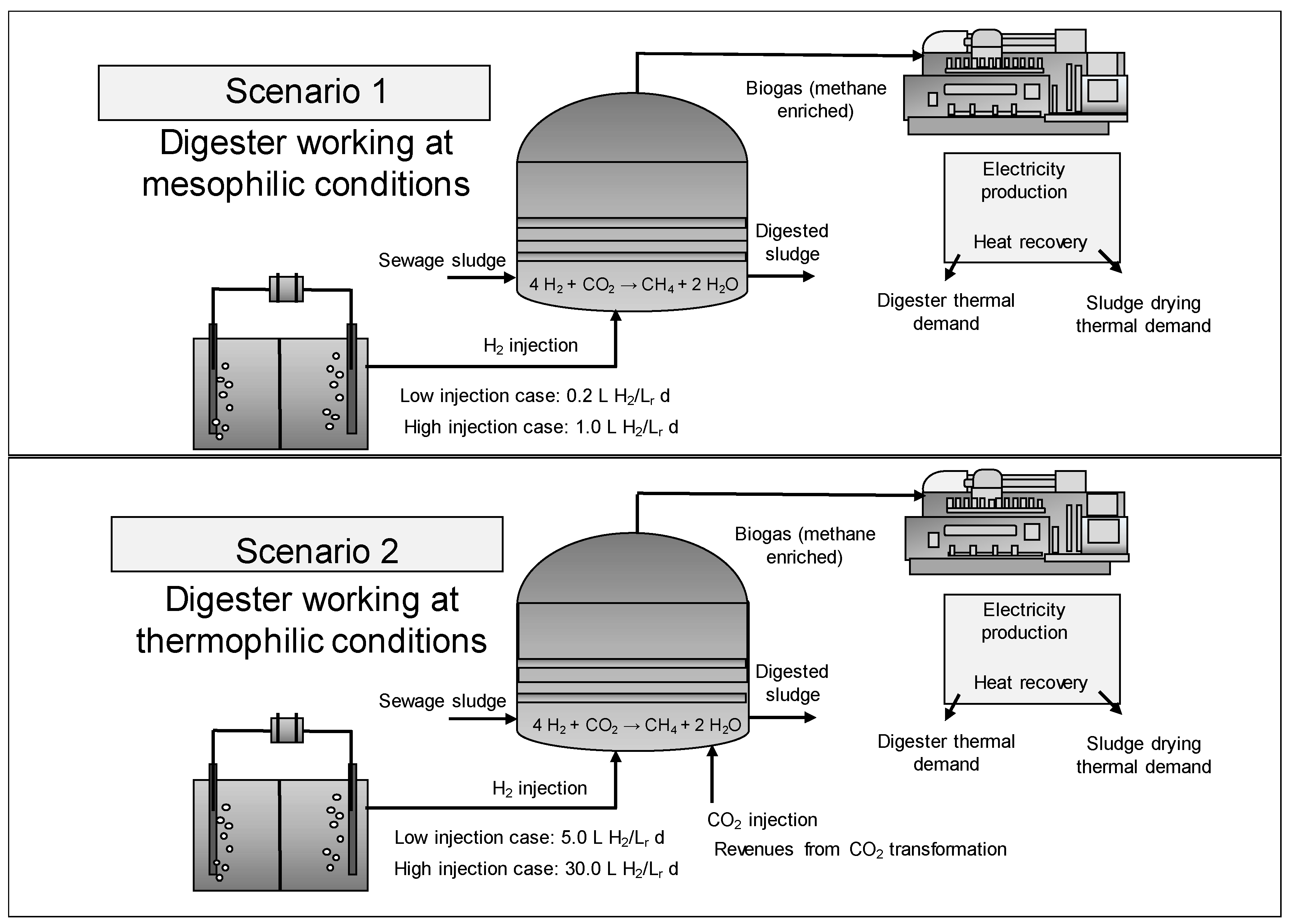

2.1. CO2-Biomethanation

2.2. Hydrogen Production from Water Electrolyzers

3. Results and Discussion

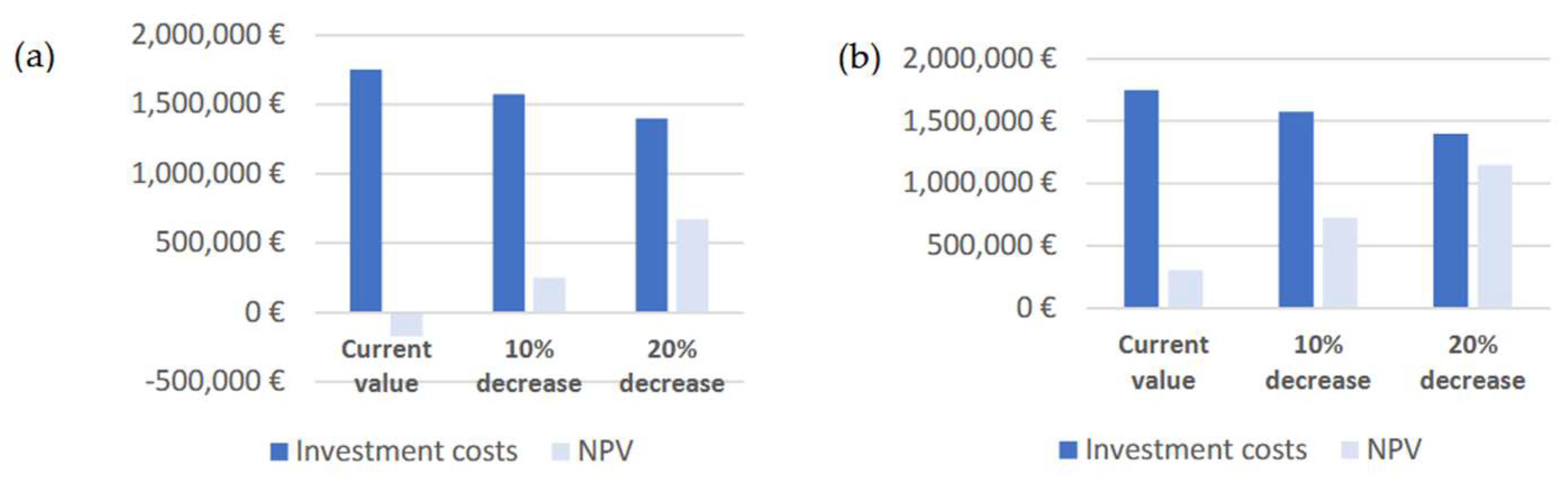

3.1. Addition of H2 Gas as a Co-Substrate in Anaerobic Digestion

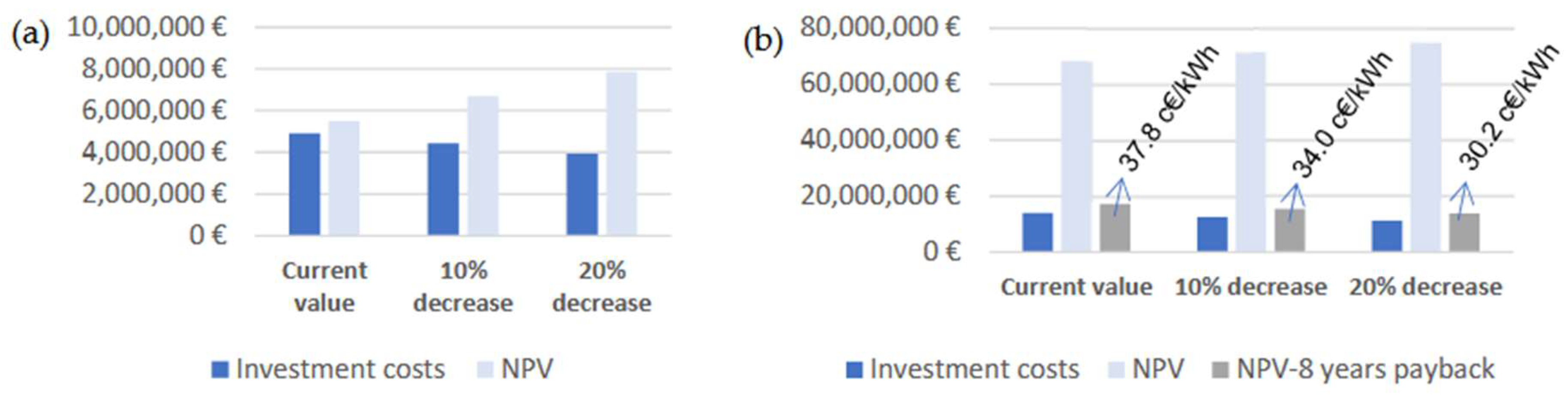

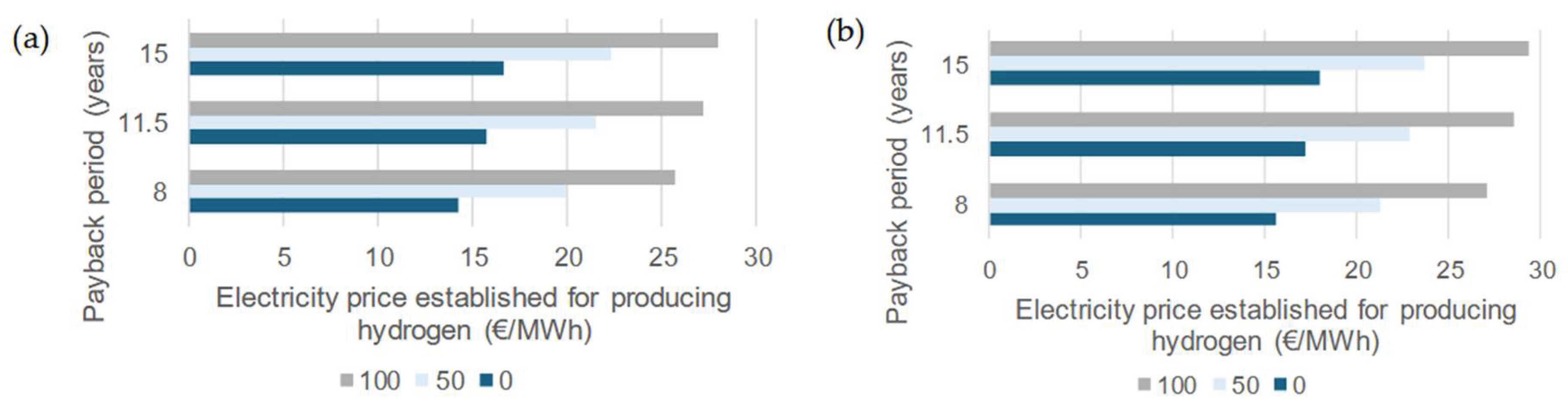

3.2. CO2-Biomethanation as a Technology for Transforming Captured CO2

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMP | Biochemical methane potential |

| BOD | Biological oxygen demand |

| CHP | Combined heat and power |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| HHV | Higher heating value |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| NPV | Net present value |

| SMP | Specific methane production |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| TS | Total solid |

| VS | Volatile solid |

| WAS | Waste activated sludge |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plant |

References

- O’Connor, G.A.; Elliott, H.A.; Basta, N.T.; Bastian, R.K.; Pierzynski, G.M.; Sims, R.C.; Smith, J.E. Sustainable Land Application. J Environ Qual 2005, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramashivam, D.; Dickinson, N.M.; Clough, T.J.; Horswell, J.; Robinson, B.H. Potential Environmental Benefits from Blending Biosolids with Other Organic Amendments before Application to Land. J Environ Qual 2017, 46, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoui, O.; Baroudi, M.; Drissi, S.; Abouabdillah, A.; Abd-Elkader, O.H.; Plavan, G.; Bourioug, M. Utilization of Digestate as an Organic Manure in Corn Silage Culture: An In-Depth Investigation of Its Profound Influence on Soil’s Physicochemical Properties, Crop Growth Parameters, and Agronomic Performance. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Eloffy, M.G.; Priya, A.K.; Yogeshwaran, V.; Yang, Z.; Elwakeel, K.Z.; Lopez-Maldonado, E.A. Biosolids Management and Utilizations: A Review. J Clean Prod 2024, 451, 141974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreeyessus, G.; Jenicek, P. Thermophilic versus Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge: A Comparative Review. Bioengineering 2016, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavala, H.N.; Yenal, U.; Skiadas, I. V.; Westermann, P.; Ahring, B.K. Mesophilic and Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Primary and Secondary Sludge. Effect of Pre-Treatment at Elevated Temperature. Water Res 2003, 37, 4561–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, X.; Blanco, D.; Lobato, A.; Calleja, A.; Martínez-Núñez, F.; Martin-Villacorta, J. Digestion of Cattle Manure under Mesophilic and Thermophilic Conditions: Characterization of Organic Matter Applying Thermal Analysis and 1H NMR. Biodegradation 2011, 22, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, E.; Zheng, Y.; Ran, X.; Ren, Z.; Guo, J.; Dong, R. Synergistic Effect of Hydrothermal Sludge and Food Waste in the Anaerobic Co-Digestion Process: Microbial Shift and Dewaterability. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2024, 31, 18723–18736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovidou, E.; Ohandja, D.-G.; Voulvoulis, N. Food Waste Co-Digestion with Sewage Sludge – Realising Its Potential in the UK. J Environ Manage 2012, 112, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando-Foncillas, C.; Estevez, M.M.; Uellendahl, H.; Varrone, C. Co-Management of Sewage Sludge and Other Organic Wastes: A Scandinavian Case Study. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.; Chong, S.; Lim, J.; Chan, Y.; Chong, M.; Tiong, T.; Chin, J.; Pan, G.-T. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Wastewater Sludge: A Review of Potential Co-Substrates and Operating Factors for Improved Methane Yield. Processes 2020, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cascallana, J.; Carrillo-Peña, D.; Morán, A.; Smith, R.; Gómez, X. Energy Balance of Turbocharged Engines Operating in a WWTP with Thermal Hydrolysis. Co-Digestion Provides the Full Plant Energy Demand. Appl Sciences 2021, 11, 11103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembera, C.; Macintosh, C.; Astals, S.; Koch, K. Benefits and Drawbacks of Food and Dairy Waste Co-Digestion at a High Organic Loading Rate: A Moosburg WWTP Case Study. Waste Manage 2019, 95, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.B.; Kofoed, M.V.W.; Fischer, K.; Voigt, N.V.; Agneessens, L.M.; Batstone, D.J.; Ottosen, L.D.M. Venturi-type injection system as a potential H2 mass transfer technology for full-scale in situ biomethanation. Appl Energy 2018, 222, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro-Shekwaga, C.K.; Ross, A.; Camargo-Valero, M.A. Enhancing bioenergy production from food waste by in situ biomethanation: Effect of the hydrogen injection point. Food Energy Secur 2021, 10(3), e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffstadt, K.; Nikolausz, M.; Krafft, S.; Bonatelli, M.L.; Kumar, V.; Harms, H.; Kuperjans, I.B. Dioxide in a Novel Meandering Plug Flow Reactor: Start-Up Phase and Flexible Operation. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggio, D.; Sastraatmaja, A.; Walker, M.; Michailos, S.; Nimmo, W.; Pourkashanian, M. Experimental Evaluation of Continuous In-Situ Biomethanation of CO2 in Anaerobic Digesters Fed on Sewage Sludge and Food Waste and the Influence of Hydrogen Gas–Liquid Mass Transfer. Processes 2023, 11, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhang, Y. In Situ Biogas Upgrading by CO2-to-CH4 Bioconversion. Trends Biotechnol 2021, 39, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.J.; Sotres, A.; Arenas, C.B.; Blanco, D.; Martínez, O.; Gómez, X. Improving Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge by Hydrogen Addition: Analysis of Microbial Populations and Process Performance. Energies (Basel) 2019, 12, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.Y.; Morgado Ferreira, A.L.; Santiago, P.-R.; Van Der Zee, F.; Lacroix, S.; Tian, J.-H.; Lens, P.N.L. Biogas Upgrading by In-Situ Biomethanation in High-Rate Anaerobic Bioreactor Treating Biofuel Condensate Wastewater. Renew Energ 2025, 248, 123113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Cabeza, I.O.; Casallas-Ojeda, M.; Gómez, X. Biological Hydrogen Methanation with Carbon Dioxide Utilization: Methanation Acting as Mediator in the Hydrogen Economy. Environments 2023, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorov, O.; Dreisbach, D. The Impact of Renewables on the Incidents of Negative Prices in the Energy Spot Markets. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, J.G. The Case of Renewable Methane by and with Green Hydrogen as the Storage and Transport Medium for Intermittent Wind and Solar PV Energy. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martínez, A.; Durán, P.; Mercader, V.D.; Francés, E.; Peña, J.Á.; Herguido, J. Biogas Upgrading by CO2 Methanation with Ni-, Ni–Fe-, and Ru-Based Catalysts. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinet-Chinaglia, C.; Shafiq, S.; Serp, P. Low Temperature Sabatier CO2 Methanation. ChemCatChem 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.C.; Centeno, M.A.; Laguna, O.H.; Odriozola, J.A. Policies and Motivations for the CO2 Valorization through the Sabatier Reaction Using Structured Catalysts. A Review of the Most Recent Advances. Catalysts 2018, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredwell, M.D.; Srivastava, P.; Worden, R.M. Reactor Design Issues for Synthesis-Gas Fermentations. Biotechnol Prog 1999, 15, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, D.E.; Klasson, K.T.; Clausen, E.C.; Gaddy, J.L. Performance of Trickle-Bed Bioreactors for Converting Synthesis Gas to Methane. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 1991, 28–29, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasson, K.T.; Elmore, B.B.; Vega, J.L.; Ackerson, M.D.; Clausen, E.C.; Gaddy, J.L. Biological Production of Liquid and Gaseous Fuels from Synthesis Gas. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 1990, 24–25, 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission 2050 Long-Term Strategy: Striving to Become the World’s First Climate-Neutral Continent by 2050. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2050-long-term-strategy_en (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Gavala, H.N.; Grimalt-Alemany, A.; Asimakopoulos, K.; Skiadas, I. V. Gas Biological Conversions: The Potential of Syngas and Carbon Dioxide as Production Platforms. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 5303–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauber, J.; Möstl, D.; Vierheilig, J.; Saracevic, E.; Svardal, K.; Krampe, J. Biological Methanation in an Anaerobic Biofilm Reactor—Trace Element and Mineral Requirements for Stable Operation. Processes 2023, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, C.M.; Pavlostathis, S.G. Zero-Valent Iron Enhances Biocathodic Carbon Dioxide Reduction to Methane. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 12956–12964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diender, M.; Uhl, P.S.; Bitter, J.H.; Stams, A.J.M.; Sousa, D.Z. High Rate Biomethanation of Carbon Monoxide-Rich Gases via a Thermophilic Synthetic Coculture. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2018, 6, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilake, B.S.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Deutzmann, J.S.; Kracke, F.; Cornell, C.; Worthington, M.A.; Freyman, M.C.; Jue, M.L.; Spormann, A.M.; Pang, S.H.; et al. Additively Manufactured High Surface Area 3D Cathodes for Efficient and Productive Electro-Bio-Methanation. ACS Electrochemistry 2025, 1, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellacuriaga, M.; González, R.; Gómez, X. Feasibility of Coupling Hydrogen and Methane Production in WWTP: Simulation of Sludge and Food Wastes Co-Digestion. Energy Nexus 2024, 14, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; González-Rojo, S.; Gómez, X. Integrating Gasification into Conventional Wastewater Treatment Plants: Plant Performance Simulation. Eng 2025, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, S.; Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Soares, A.; Campo, P.; Fatone, F.; Eusebi, A.L.; Akkersdijk, E.; Stefani, L.; Hospido, A. ENERWATER – A Standard Method for Assessing and Improving the Energy Efficiency of Wastewater Treatment Plants. Appl Energy 2019, 242, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, M.N.; Spanjers, H.; Baetens, D.; Nowak, O.; Gillot, S.; Nouwen, J.; Schuttinga, N.; Wastewater Characteristics in Europe-A Survey. European Water Management Online 2004, 4. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Henri_Spanjers/publication/237790819_Wastewater_Characteristics_in_Europe_-_A_Survey/links/54aaa4460cf2bce6aa1d5229.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Oliveira, S.C.; Von Sperling, M. Reliability Analysis of Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res 2008, 42, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.J.; Fierro, J.; Sánchez, M.E.; Gómez, X. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of FOG and Sewage Sludge: Study of the Process by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2012, 75, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorin, E.; Olsson, J.; Schwede, S.; Nehrenheim, E. Co-Digestion of Sewage Sludge and Microalgae – Biogas Production Investigations. Appl Energy 2018, 227, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-J.; Oh, K.-S.; Lee, B.; Pak, D.-W.; Cha, J.-H.; Park, J.-G. Characteristics of Biogas Production from Organic Wastes Mixed at Optimal Ratios in an Anaerobic Co-Digestion Reactor. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Blanco, D.; Cascallana, J.G.; Carrillo-Peña, D.; Gómez, X. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sheep Manure and Waste from a Potato Processing Factory: Techno-Economic Analysis. Fermentation 2021, 7, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; García-Cascallana, J.; Gómez, X. Energetic Valorization of Biogas. A Comparison between Centralized and Decentralized Approach. Renew Energy 2023, 215, 119013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, E.; Canakci, M. Determination of the Density and the Viscosities of Biodiesel–Diesel Fuel Blends. Renew Energy 2008, 33, 2623–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, N. Comparative Analysis of Biodiesel–Ethanol–Diesel and Biodiesel–Methanol–Diesel Blends in a Diesel Engine. Energy 2012, 40, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenbacher Jenbacher de Tipo 2: J208 Available online:. Available online: https://www.jenbacher.com/es/motores-de-gas/tipo-2 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Simons, G.; Barsun, S. Chapter 23: Combined Heat and Power Evaluation Protocol, The Uniform Methods Project: Methods for Determining Energy-Efficiency Savings for Specific Measures.; National Renewable Energy Laboratory., 2017. Available online: http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/68579.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Trading Economics. EU Natural gas TTF. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/eu-natural-gas (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Schwede, S.; Bruchmann, F.; Thorin, E.; Gerber, M. Biological Syngas Methanation via Immobilized Methanogenic Archaea on Biochar. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafrafi, Y.; Laguillaumie, L.; Dumas, C. Biological Methanation of H2 and CO2 with Mixed Cultures: Current Advances, Hurdles and Challenges. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 5259–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillet, F.; Crestey, E.; Gaval, G.; Haddad, M.; Lebars, F.; Nicolitch, O.; Camacho, P. Utilization of Dissolved CO2 to Control Methane and Acetate Production in Methanation Reactor. Bioresour Technol 2025, 416, 131722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thema, M.; Weidlich, T.; Hörl, M.; Bellack, A.; Mörs, F.; Hackl, F.; Kohlmayer, M.; Gleich, J.; Stabenau, C.; Trabold, T.; et al. Biological CO2-Methanation: An Approach to Standardization. Energies 2019, 12, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, P.C.; Khanal, S.K. Syngas Fermentation to Biofuel: Evaluation of Carbon Monoxide Mass Transfer Coefficient (KLa) in Different Reactor Configurations. Biotechnol Prog 2010, 26, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hao, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H. Biological Methanation of H2 and CO2 in a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor. J Clean Prod 2022, 370, 133518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Dong, R.; Xiong, W.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. Integration of In-Situ and Ex-Situ Power-to-Gas (PtG) Strategy for Simultaneous Bio-Natural Gas Production and CO2 Emission Reduction. Chemosphere 2023, 344, 140370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguillaumie, L.; Rafrafi, Y.; Moya-Leclair, E.; Delagnes, D.; Dubos, S.; Spérandio, M.; Paul, E.; Dumas, C. Stability of Ex Situ Biological Methanation of H2/CO2 with a Mixed Microbial Culture in a Pilot Scale Bubble Column Reactor. Bioresour Technol 2022, 354, 127180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illi, L.; Lecker, B.; Lemmer, A.; Müller, J.; Oechsner, H. Biological Methanation of Injected Hydrogen in a Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion Process. Bioresour Technol 2021, 333, 125126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strübing, D.; Moeller, A.B.; Mößnang, B.; Lebuhn, M.; Drewes, J.E.; Koch, K. Anaerobic Thermophilic Trickle Bed Reactor as a Promising Technology for Flexible and Demand-Oriented H2/CO2 Biomethanation. Appl Energy 2018, 232, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haitz, F.; Jochum, O.; Lasota, A.; Friedrich, A.; Bieri, M.; Stalder, M.; Schaub, M.; Hochberg, U.; Zell, C. Continuous Biological Ex Situ Methanation of CO2 and H2 in a Novel Inverse Membrane Reactor (IMR). Processes 2024, 12, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensmann, A.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R.; Heyer, R.; Kohrs, F.; Benndorf, D.; Reichl, U.; Sundmacher, K. Biological Methanation of Hydrogen within Biogas Plants: A Model-Based Feasibility Study. Appl Energy 2014, 134, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambou, F.; Guilbert, D.; Zasadzinski, M.; Rafaralahy, H. A Comprehensive Survey of Alkaline Electrolyzer Modeling: Electrical Domain and Specific Electrolyte Conductivity. Energies 2022, 15, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.; Cebola, M.-J.; Santos, D.M.F. Towards the Hydrogen Economy—A Review of the Parameters That Influence the Efficiency of Alkaline Water Electrolyzers. Energies 2021, 14, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantenbein, A.; Kroecher, O.; Biollaz, S.M.; Schildhauer, T.J. Techno-economic evaluation of biological and fluidised-bed based methanation process chains for grid-ready biomethane production. Front Energy Res 2022, 9, 775259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Koning, V.; Theodorus de Groot, M.; De Groot, A.; Mendoza, P.G.; Junginger, M.; Kramer, G.J. Present and future cost of alkaline and PEM electrolyser stacks. Int J Hydrogen Energ 2023, 48(83), 32313–32330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen EnergyTM, Hy. GEN-E®: Electrolysis Available online:. Available online: https://www.hygreenenergy.com/electrolyzers/pem-electrolyzers/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- van der Roest, E.; Bol, R.; Fens, T.; van Wijk, A. Utilisation of Waste Heat from PEM Electrolysers – Unlocking Local Optimisation. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27872–27891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgett, A.; Brauch, J.; Thatte, A.; Rubin, R.; Skangos, C.; Wang, X.; Ahluwalia, R.; Pivovar, B.; Ruth, M. 2024. Updated manufactured cost analysis for proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers (No. NREL/TP-6A20-87625). National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Golden, CO (United States). [CrossRef]

- The University of Manchester Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index. Available online: https://www.training.itservices.manchester.ac.uk/public/gced/CEPCI.html?reactors/CEPCI/index.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Vineyard, D.; Karthikeyan, K.G.; Barak, P. BioWin Modeling of CalPrex Phosphorus Re-covery from Wastewater Predicts Substantial Nuisance Struvite Reduction. Environments 2024, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garske, B.; Ekardt, F. Economic Policy Instruments for Sustainable Phosphorus Management: Taking into Account Climate and Biodiversity Targets. Environ Sci Eur 2021, 33, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Schenk, G.; Schmidt, S. Realising the Circular Phosphorus Economy Delivers for Sustainable Development Goals. npj Sustain Agric 2023, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, T.P.; Sárossy, Z.; Gøbel, B.; Stoholm, P.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Frandsen, F.J.; Henriksen, U.B. Low Temperature Circulating Fluidized Bed Gasification and Co-Gasification of Municipal Sewage Sludge. Part 1: Process Performance and Gas Product Characterization. Waste Manage 2017, 66, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, J.L.F.; da Silva, J.C.G.; Languer, M.P.; Batistella, L.; Di Domenico, M.; da Silva Filho, V.F.; Moreira, R. de F.P.M.; José, H.J. Assessing the Bioenergy Potential of High-Ash Anaerobic Sewage Sludge Using Pyrolysis Kinetics and Thermodynamics to Design a Sustainable Integrated Biorefinery. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2022, 12, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januševičius, T.; Mažeikienė, A.; Danila, V.; Paliulis, D. The Characteristics of Sewage Sludge Pellet Biochar Prepared Using Two Different Pyrolysis Methods. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 14, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediboyina, M.K.; Murphy, F. Environmental Assessment of a Waste-to-Energy Cascading System Integrating Forestry Residue Pyrolysis and Poultry Litter Anaerobic Digestion. Energies 2024, 17, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Electricity Price Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Electricity_price_statistics (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Bellini, R.; Bassani, I.; Vizzarro, A.; Azim, A.; Vasile, N.; Pirri, C.; Verga, F.; Menin, B. Biological Aspects, Advancements and Techno-Economical Evaluation of Biological Methanation for the Recycling and Valorization of CO2. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khesali Aghtaei, H.; Püttker, S.; Maus, I.; Heyer, R.; Huang, L.; Sczyrba, A.; Reichl, U.; Benndorf, D. Adaptation of a Microbial Community to Demand-Oriented Biological Methanation. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 2022, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, M.; Colantoni, S.; Cruz Viggi, C.; Aulenta, F. Improving the Kinetics of H2-Fueled Biological Methanation with Quinone-Based Redox Mediators. Catalysts 2023, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, S.; Tsubota, J.; Angelidaki, I.; Hidaka, T.; Fujiwara, T. Pilot-Scale in-Situ Biomethanation of Sewage Sludge: Effects of Gas Recirculation Method. Bioresour Technol 2024, 413, 131524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Hui, Y.; Hu, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Feng, X.; Guo, K. A Novel Electrolytic Gas Lift Reactor for Efficient Microbial Electrosynthesis of Acetate from Carbon Dioxide. Bioresour Technol 2024, 393, 130124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.B.; Ottosen, L.D.M.; Kofoed, M.V.W. H2 Gas-Liquid Mass Transfer: A Key Element in Biological Power-to-Gas Methanation. Renew Sust Energ 2021, 147, 111209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorna, D.; Varga, Z.; Andreides, D.; Zabranska, J. Adaptation of Anaerobic Culture to Bioconversion of Carbon Dioxide with Hydrogen to Biomethane. Renew Energy 2019, 142, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanapan, C.; Sinchai, L.; Tachapattaworakul Suksaroj, T.; Kantachote, D.; Ounsaneha, W. Biogas Production by Co-Digestion of Canteen Food Waste and Domestic Wastewater under Organic Loading Rate and Temperature Optimization. Environments 2019, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beswick, R.R.; Oliveira, A.M.; Yan, Y. Does the green hydrogen economy have a water problem? ACS Energy Letters 2021, 6(9), 3167–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, M.P.; Longo, S.; Cellura, M.; Miccichè, G.; Ferraro, M. Critical Review of Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen Produc-tion Pathways. Environments 2024, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

| Number of equivalent inhabitants | 150,000 | [19] |

| Specific wastewater production (L/inhab. d) | 330 | [38] |

| Percentage of water removed with particle separation unit at WWTP inlet | 2% | [36] |

| Biomass yield (WAS1 process) | 0.6 | [36] |

| Volumetric air supplied to WAS (m3 air/m3reactor min) | 0.025 | Based on SuperPro Designer model assumption |

| Power WAS process (kW/m3reactor) | 0.3 | Based on SuperPro Designer model assumption |

| WAS stream recirculation | 35% | [36] |

| Primary sludge total solid (TS) content (g/L) | 60 ± 12 | |

| Percentage of volatile solids (%VS) primary sludge | 75 ± 15 | |

| Secondary sludge TS content (g/L) | 45 ± 9 | |

| (%VS) secondary sludge | 65 ± 13 | |

| Organic matter (COD mg/L)2 | 760 ± 152 | [39] |

| Organic matter (BOD mg/L) (50% of COD value) | 380 ± 77 | [40] |

| Biochemical methane potential (BMP) (Average value from references) | 300 ± 73 | [41,42,43] |

| Digester Maximum volume (m3) | 4000 | [36] |

| Digester diameter:height ratio | 1:2 | |

| Digester free head space (%) | 25 | |

| Biogas methane content (%) | 60 | |

| Methane LHV (MJ/m3) | 35.8 |

| Parameter | Value |

| Inlet wastewater flow (m3/d) | 49,500 |

| Primary sludge flow (m3/d) | 104.5 ± 33.0 |

| Secondary sludge flow (m3/d) | 120.2 ± 23.4 |

| Methane production (m3/d) | 2354 ± 798 |

| Energy in biogas (MJ/d) | 84,268 ± 28,590 |

| Electricity production (kW) | 370.6 ± 125.7 |

| Heat production(kW) | 507.2 ± 172.1 |

| Digester thermal demand (kW) under summer conditions | 263 ± 49 |

| Digester thermal demand (kW) under winter conditions | 402 ± 75 |

| Dewatered digestate flow (m3/d) | 33.1 ± 9.7 |

| Energy needs for dewatered digestate transport (MJ/year) | 333,246 ± 101,290 |

| Transport costs dewatered sludge (€/year) | 45,795 ± 13,919 |

| Thermal demand sludge drying (kW) | 925 ± 320 |

| Specific sludge drying demand (GJ/t water evaporated) | 3.1 ± 1.5 |

| Auxiliary fuel required during winter conditions (kW) | 1118 ± 348 |

| Annual auxiliary fuel demand without considering sludge drying (GJ) | 2437 ± 1537 |

| Annual costs auxiliary fuel demand without considering sludge drying (€) | 30,472 ± 19,213 |

| Annual auxiliary fuel demand with sludge drying (GJ) | 32,823 ± 10,910 |

| Annual cost auxiliary fuel demand with sludge drying (€) | 410,296 ± 136,377 |

| Parameter | Low H2 injection case | High H2 injection case |

| Specific H2 injection rate (L H2/Lr d) | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Hydrogen flow (m3 STP1/d) | 1176 | 5880 |

| Electrolyzer size (kW) | 225 | 1100 |

| Electrolyzer Price (€) | 357,000 | 1,748,000 |

| Oxygen produced from water electrolysis (m3/h) | 24.5 | 112.5 |

| Methane production from CO2-biomethanation (m3/h) | 12.3 | 61.3 |

| Electrolyzer heat recovery (kW) | 33.7 | 168.6 |

| CHP heat recovery (high temperature gases) (kW) | 1170 | 5585 |

| Digester thermal demand, winter period (kW) | 401 ± 72 | |

| Auxiliary fuel required to cover digester thermal demand under winter conditions (kW) | 150 ± 90 | |

| Parameter | Low H2 injection case | High H2 injection case |

| Specific H2 injection rate (L H2/Lr d) | 5 | 30 |

| Hydrogen flow (m3 STP1/d) | 29,400 | 176,400 |

| Electrolyzer size (MW) | 5.3 | 31.6 |

| Electrolyzer Price (Millions €) | 5 | 13.9 |

| Oxygen produced from water electrolysis (m3/h) | 612 | 3675 |

| Methane production from CO2-biomethanation (m3/h) | 306 | 1840 |

| Electrolyzer heat recovery (kW) | 840 | 5056 |

| Digester thermal demand, summer period (kW) | 475 ± 88 | |

| Digester thermal demand, winter period (kW) | 622 ± 115 | |

| Auxiliary fuel required during winter period to cover digester thermal demand (kW) | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).