Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

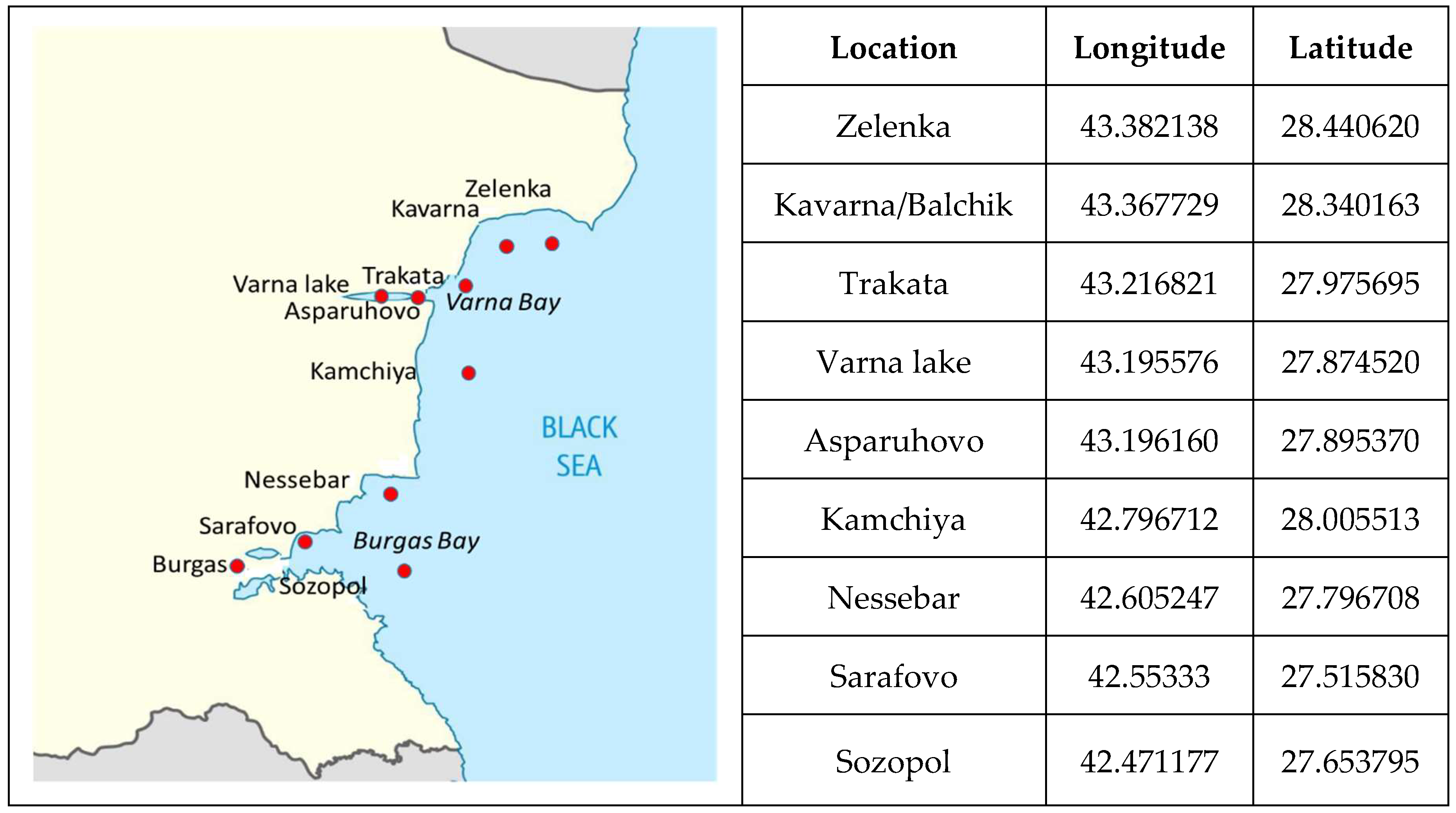

2.1. Species and Sampling Areas

2.2. Morphometry

2.3. Determination of Microplastics in Species Samples

2.4. Tissue Preparation for Biochemical Analyses

2.5. Biochemical Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characteristics of the Studied Species and Accumulated Microplastic Particles in Them

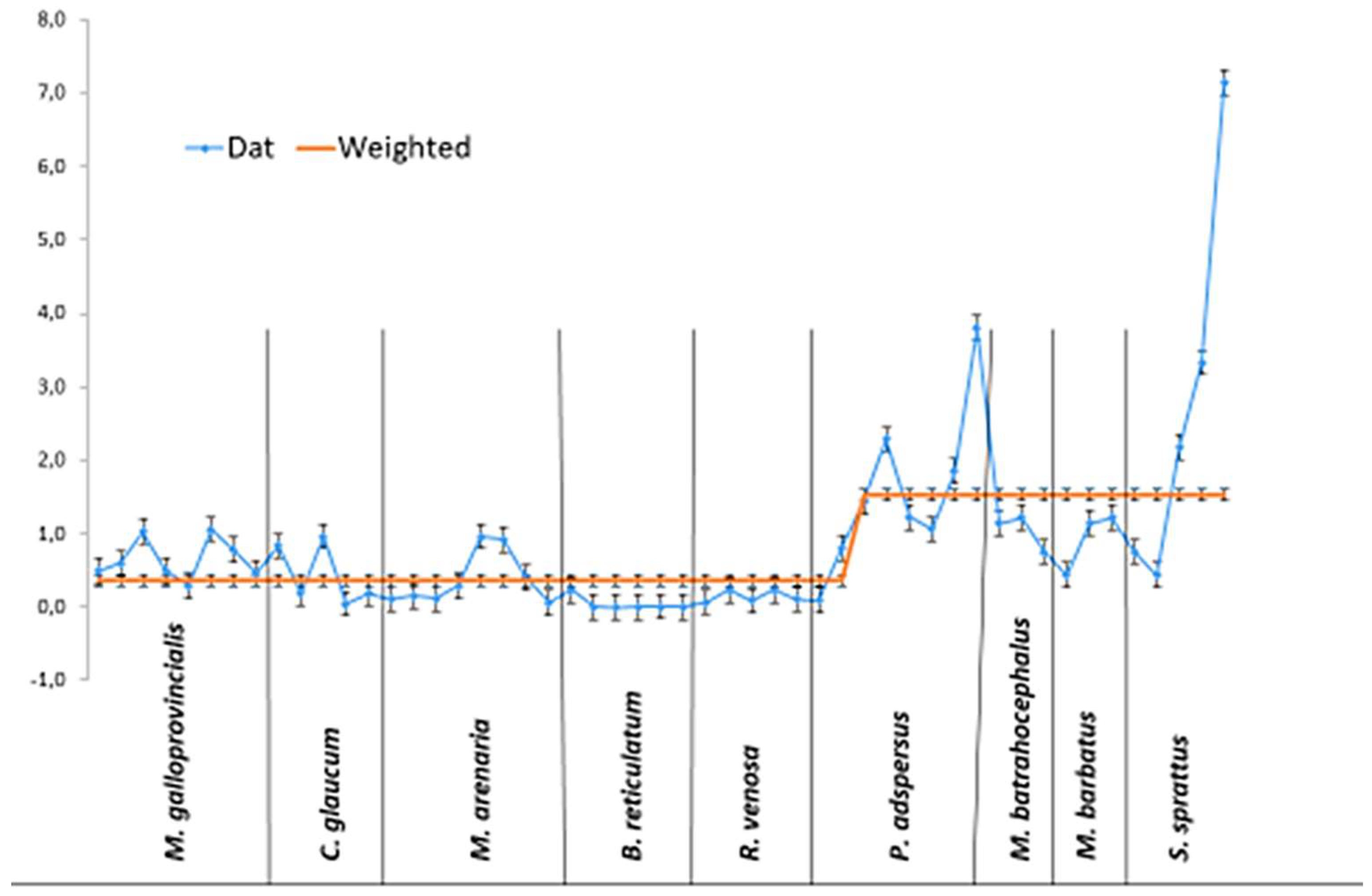

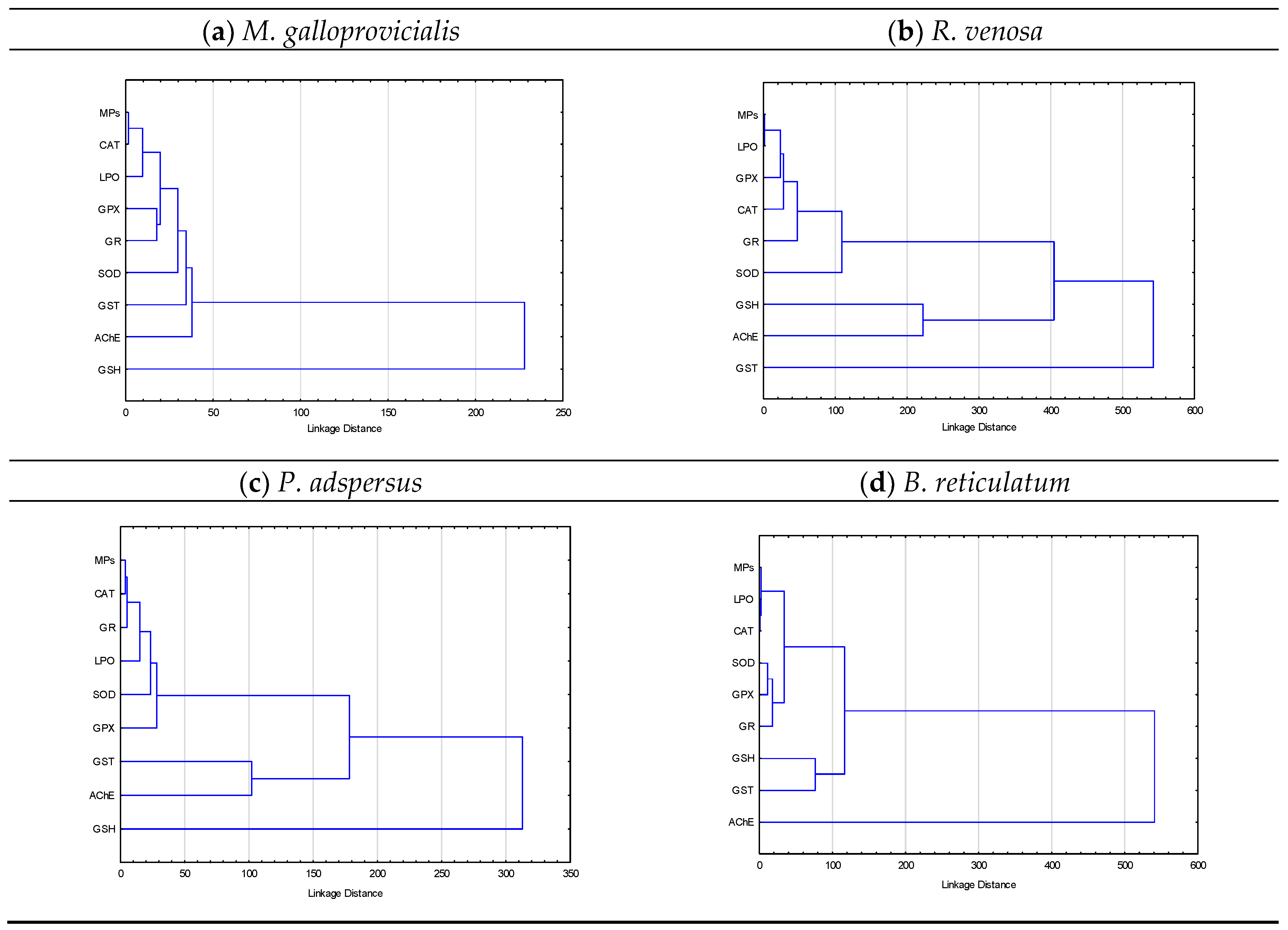

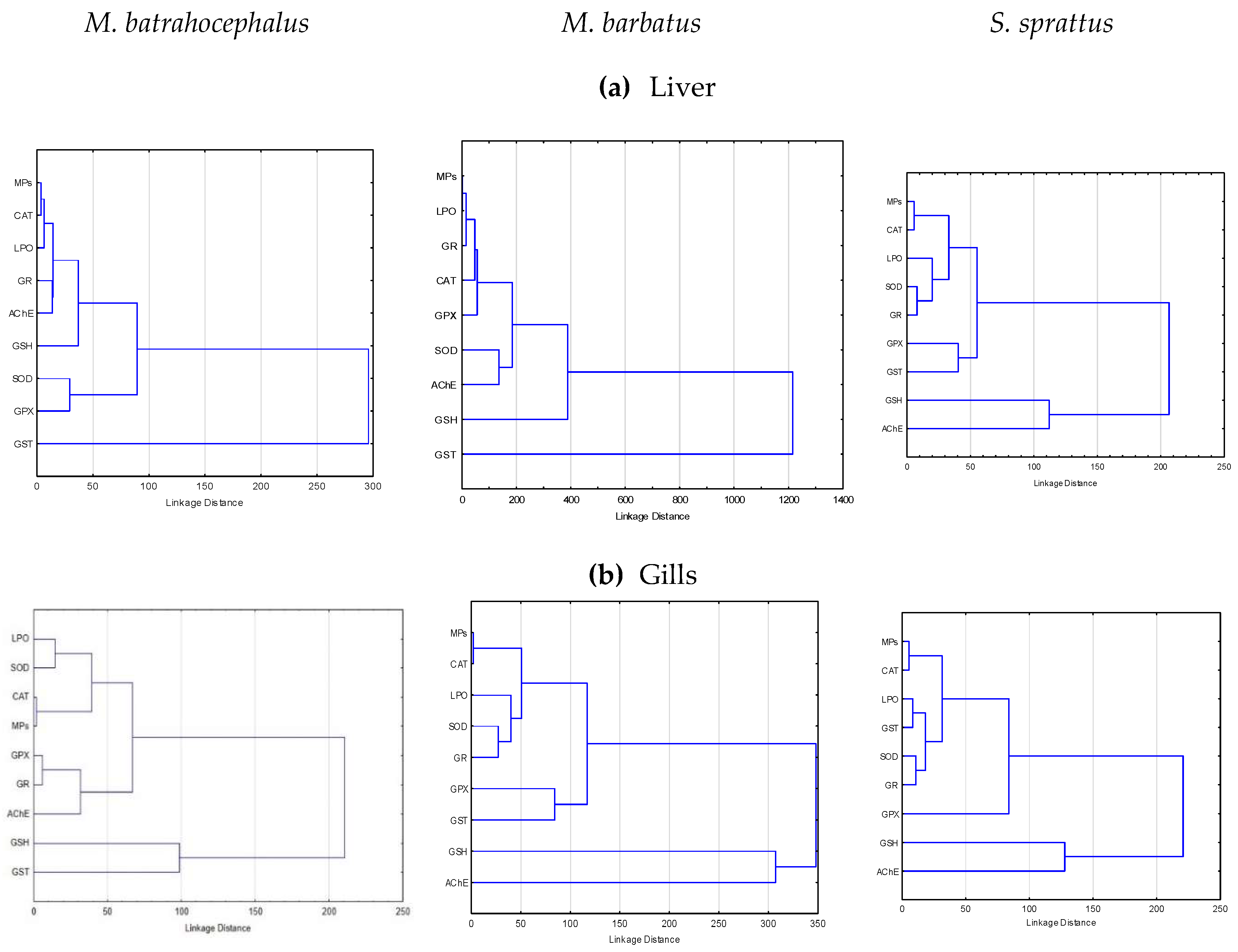

3.2. Oxidative Stress Levels in the Studied Species

| biometrics | K | oxidative stress biomarkers | |||||||||

| W | L | LPO | GSH | SOD | CAT | GPx | GR | GST | AChE | ||

| Species | g | cm | nM/mg protein | ng/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | |

| M. batrachocephalus | 73.0 | 19.5 | 0.98 | 7.45b | 32.9b,c | 80.5b,c | 2.02b | 74.6b,c | - | 225.9b,c | 17.8b,c |

| ±3.62 | ±0.35 | ±0.02 | ±0.83 | ±4.30 | ±1.94 | ±0.16 | ±6.25 | - | ±11.78 | ±0.52 | |

| M. barbatus | 9.60 | 9.44 | 1.04 | 0.93a,c | 135.1a | 86.1c | 8.00a,c | 27.5a | 17.42 | 476.8a,c | 50.1a,c |

| ±4.17 | ±1.40 | ±0.05 | ±0.19 | ±67.45 | ±14.89 | ±4.00 | ±9.15 | ±1.25 | ±16.65 | ±13.02 | |

| S. sprattus | 2.94 | 7.70 | 0.61 | 10.3a | 130.9a | 19.97a,b | 1.87b | 32.2a | 17.10 | 850.4a,b | 32.9a,b |

| ±1.12 | ±0.87 | ±0.04 | ±3.84 | ±13.95 | ±2.64 | ±0.27 | ±10.78 | ±2.62 | ±10.05 | ±8.12 | |

| biometrics | K | oxidative stress biomarkers | |||||||||

| W | L | LPO | GSH | SOD | CAT | GPx | GR | GST | AChE | ||

| Species | g | cm | nM/mg protein | ng/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | |

| M. batrachocephalus | 73.0 | 19.5 | 0.98 | 19.2 | 320.1b,c | 19.3c | 3.68b.c | 24.8b,c | - | 121.8b,c | 187.2b,c |

| ±3.62 | ±0.35 | ±0.02 | ±1.29 | ±33.50 | ±2.03 | ±0.58 | ±3.11 | - | ±3.16 | ±18.95 | |

| M. barbatus | 9.60 | 9.44 | 1.04 | 11.3 | 160.5a | 20.2c | 0.50a | 51.7a | 23.7 | 51.8a,c | 57.3a,c |

| ±4.17 | ±1.40 | ±0.05 | ±6.62 | ±62.66 | ±3.90 | ±0.20 | ±23.4 | ±5.2 | ±5.54 | ±16.2 | |

| S. sprattus | 2.94 | 7.70 | 0.61 | 20.5 | 141.7a | 8.49a,b | 0.55a | 47.6a | 13.7 | 86.2a,b | 17.3a,b |

| ±1.12 | ±0.87 | ±0.04 | ±0.47 | ±11.59 | ±1.25 | ±0.12 | ±6.81 | ±1.81 | ±6.08 | ±1.92 | |

| M. batrachocephalus | M. barbatus | S. sprattus | M. galloprovincialis | R. venosa | B. reticulatum | P. adspersus | M. gigas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrO | 0.109 | -1.872 | 1.410 | -0.132 | -1.118 | -0.736 | 0.149 | 0.561 |

| AO | 0.804 | 0.863 | -1.335 | -0.891 | -0.681 | 0.357 | -0.457 | 0.627 |

| SOS | -0.694 | -2.736 | 2.745 | 0.758 | -0.437 | -1.093 | 0.606 | -0.066 |

| Very low stress (<-2) |

Low stress (-1 to -2) |

Stress actively compensated (-1 to +1) |

Moderate stress (+1 to +2) |

High stress (+2<) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. reticulatum |

R. venosa M. galloprovincialis M. gigas P. adspersus |

- | ||

| M. barbatus | M. batrachocephalus | - | S. sprattus |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AO | Antioxidant score |

| CAT | Catalase |

| FO | Frequency of occurrence |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal tract |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione Reductase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GST | Glutathione-S-Transferase |

| L | Total length |

| LPO | Lipid Peroxidation |

| MPs | Microplastics |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| PrO | Pro-oxidative score |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| SOS | Specific Oxidative Stress Index |

| ST | Soft tissues |

| W | Total weight |

References

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com.

- Plastic Pollution Coalition. Available online: https://plastic-pollution.org/.

- González-Fernández, D.; Pogojeva, M.; Hanke, G.; Machitadze, N.; Kotelnikova, Y.; Tretiak, I.; Savenko, O.; Gelashvili, N.; Bilashvili, K.; Kulagin, D.; et al. Anthropogenic Litter Input through Rivers in the Black Sea. In Marine Litter in the Black Sea; Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A., Eds.; Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV): Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; Publication No: 56. [Google Scholar]

- Moncheva, S.; Stefanova, K.; Krastev, A.; Apostolov, A.; Bat, L.; Sezgin, M.; Sahin, F.; Timofte, F. Marine Litter Quantification in the Black Sea: A Pilot Assessment. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 16, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzer, U.; Yildiz, T.; Karakulak, F.S. Distribution and Composition of Marine Litter on Seafloor in the Western Black Sea, Turkey. In Marine Litter in the Black Sea; Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A., Eds.; Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV): Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; Publication No: 56. [Google Scholar]

- Kasapoğlu, N.; Dağtekin, M.; İlhan, S.; Erik, G.; Özsandikçi, U.; Büyükdeveci, F. Distribution and Composition of Seafloor Marine Litter in the Southeastern Black Sea. In Marine Litter in the Black Sea; Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A., Eds.; Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV): Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; Publication No: 56. [Google Scholar]

- GESAMP. Guidelines for the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter in the Ocean; GESAMP Reports Stud. 2019, 99; GESAMP: London, UK, 2019; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Lusher, A. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Distribution, Interactions and Effects. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 245–307. [Google Scholar]

- Savuca, A.; Nicoara, M.N.; Faggio, C. Comprehensive Review Regarding the Profile of the Microplastic Pollution in the Coastal Area of the Black Sea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonova, A.; Chuturkova, R. Marine Litter Accumulation Along the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast: Categories and Predominance. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeonova, A.; Chuturkova, R.; Toneva, D.; Tsvetkov, M. Plastic pollution along the Bulgarian Black Sea coast: Current status and trends. In Marine Litter in the Black Sea; Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A., Eds.; Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV): Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; Publication No: 56. [Google Scholar]

- Miladinova, S.; Macias, D.; Stips, A.; Garcia-Gorriz, E. Identifying Distribution and Accumulation Patterns of Floating Marine Debris in the Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 153, 110964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strokal, M.; Vriend, P.; Bak, M.P.; et al. River Export of Macro- and Microplastics to Seas by Sources Worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săvucă, A.; Nicoara, M.N.; Faggio, C. Comprehensive review regarding the profile of the microplastic pollution in the coastal area of the Black Sea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, Ü.; Şentürk, Y.; Esensoy, F. B.; Öztekin, A.; Ağırbaş, E.; Valente, A. Microplastic pollution along the southeastern Black Sea. In book: Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A. (Eds.) 2020, Marine Litter in the Black Sea. Publisher: Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV) Publication No: 56, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Cincinelli, A.; Scopetani, C.; Chelazzi, D.; Martellini, T.; Pogojeva, M.; Slobodnik, J. Microplastics in the Black Sea Sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojar, I.; Stănică, A.; Stock, F.; Kochleus, C.; Schultz, M.; Bradley, C. Sedimentary microplastic concentrations from the Romanian Danube River to the Black Sea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, Y.; Gedik, K.; Eryaşar, A.R.; Öztürk, R.Ç.; Şahin, A.; Yılmaz, F. Microplastic contamination and characteristics spatially vary in the southern Black Sea beach sediment and sea surface water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, T.; Minaz, M.; Baytaşoğlu, H.; Gedik, K. Microplastic pollution in stream sediments discharging from Türkiye’s eastern Black Sea basin. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobchev, N.; Berov, D.; Klayn, S.; Karamfilov, V. High microplastic pollution in marine sediments associated with urbanised areas along the SW Bulgarian Black Sea coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berov, D.; Klayn, St. Microplastics and floating litter pollution in Bulgarian Black Sea coastal waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojar, I.; Kochleus, C.; Dierkes, G.; Ehlers, S.M.; Reifferscheid, G.; Stock, F. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of plastic particles in surface waters of the Western Black Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bat, L.; Öztekin, A. Microplastic Pollution in the Black Sea: An Overview of the Current Situation. In Microplastic Pollution. Emerging Contaminants and Associated Treatment Technologies; Hashmi, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, S.K.; Peteva, Z.V.; Stancheva, M.D. Evaluation of abundance of microplastics in the Bulgarian coastal waters. In Actual Problems of Ecology; Chankova, S., Danova, K., Beltcheva, M., Radeva, G., Petrova, V., Vassilev, K., Eds.; BioRisk 2023, 20, 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Öztekin, A.; Bat, L. Microlitter Pollution in Sea Water: A Preliminary Study from Sinop Sarikum Coast of the Southern Black Sea. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Marine Sciences; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Öztekin, A.; Üstün, F.; Bat, L.; Tabak, A. Microplastic Contamination of the Seawater in the Hamsilos Bay of the Southern Black Sea. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Valente, A.; Senturk, Y.; Usta, R.; Esensoy Sahin, F.B.; Mazlum, R.E.; Agırbas, E. First evaluation of neustonic microplastics in Black Sea waters. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 119, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Esensoy, F.B.; Senturk, Y.; Arifoğlu, E.; Karaoğlu, K.; Ceylan, Y.; Valente, A. Plastic Occurrence in Commercial Fish Species of the Black Sea. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 22, TRJFAS20504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Esensoy, F.B.; Senturk, Y. Microplastic ingestion and egestion by copepods in the Black Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Esensoy, F.B.; Senturk, Y.; Güven, O.; Karaoğlu, K.; Erbay, M. Plastic occurrence in fish caught in the highly industrialized Gulf of İzmit (Eastern Sea of Marmara, Türkiye). Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, K.; Eryaşar, A.R. Microplastic pollution profile of Mediterranean mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) collected along the Turkish coasts. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, Y.; Esensoy, F.B.; Öztekin, A.; Aytan, Ü. Microplastics in bivalves in the southern Black Sea. In Marine Litter in the Black Sea; Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A., Eds.; Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV), Publication No. 56: Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Şentürk, Y.; Emanet, M.; Ceylan, Y.; Aytan, U. The First Evidence of Microplastics Occurrence in Greater Pipefish (Syngnathus acus Linnaeus, 1758) in the Black Sea. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 23, TRJFAS23764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, K.; Gozler, A.M. Hallmarking microplastics of sediments and Chamelea gallina inhabiting Southwestern Black Sea: A hypothetical look at consumption risks. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimon, A.; Ciucă, A.-M.; Harcotă, G.-E.; Stoica, E. Preliminary Study on Microplastic Contamination in Black Sea Cetaceans: Gastrointestinal Analysis of Phocoena phocoena relicta and Tursiops truncatus ponticus. Animals 2024, 14, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrova, A.; Ignatova-Ivanova, T.V.; Bachvarova, D.G.; Toschkova, S.G.; Doichinov, A.H.; Ibryamova, S.F.; Chipev, N.H. Pilot Screening and Assessment of Microplastic Bioaccumulation in Wedge Clams Donax trunculus Linnaeus, 1758 (Bivalvia) from the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2022, 74, 569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Ibryamova, S.; Toschkova, S.; Bachvarova, D.; Lyatif, A.; Stanachkova, E.; Ivanov, R.; Natchev, N.; Ignatova-Ivanova, T. Assessment of the bioaccumulation of microplastics in the Black Sea mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis L., 1819. J. IMAB 2022, 28, 4676–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihova, M.; Toschkova, S.; Bachvarova, D.; Ibryamova, S.; Ignatova-Ivanova, T.; Natchev, N. Microplastic Uptake by Mya arenaria Linnaeus, 1758, Mytilus galloprovincialis Lamarck, 1819 and Cerastoderma glaucum (Bruguière, 1789) (Bivalvia) from Varna Lake, Bulgaria. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2024, 76, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschkova, S.; Ibryamova, S.; Bachvarova, D.Ch.; Koynova, T.; Stanachkova, E.; Ivanov, R.; Natchev, N.; Ignatova-Ivanova, T. The assessment of the bioaccumulation of microplastics in key fish species from the Bulgarian aquatory of the Black Sea. BioRisk 2024, 22, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramatarov, G.I.; Tsvetanova, E.R.; Ilinkin, V.M.; Andreeva, M.N.; Alexandrova, A.V.; Chipev, N.H. Effects of Microplastics and Metal Pollution on Bivalves from the Bulgarian Black Sea Sublittoral, with Comments on their Adaptive Capacity. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2025, 77, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Lee, W.T.; Chan, A.K.Y.; Lo, H.S.; Shin, P.K.S.; Cheung, S.G. Microplastic ingestion reduces energy intake in the clam Atactodea striata. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Vieira, L.R.; Branco, V.; Carvalho, C.; Guilhermino, L. Microplastics increase mercury bioconcentration in gills and bioaccumulation in the liver, and cause oxidative stress and damage in Dicentrarchus labrax juveniles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardon, T.; Reisser, C.; Soyez, C.; Quillien, V.; Le Moullac, G. Microplastics affect energy balance and gametogenesis in the pearl oyster Pinctada margaritifera. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5277–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Moos, N.; Burkhardt-Holm, P.; Köhler, A. Uptake and effects of microplastics on cells and tissue of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis L. after an experimental exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11327–11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avio, C.G.; Gorbi, S.; Milan, M.; Benedetti, M.; Fattorini, D.; d’Errico, G.; Pauletto, M.; Bargelloni, L.; Regoli, F. Pollutants bioavailability and toxicological risk from microplastics to marine mussels. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 198, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avio, C.G.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F. Plastics and microplastics in the oceans: From emerging pollutants to emerged threat. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 128, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Soltani, N.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Turner, A.; Hassanaghaei, M. Microplastics in different tissues of fish and prawn from the Musa Estuary, Persian Gulf. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadac-Czapska, K.; Ośko, J.; Knez, E.; Grembecka, M. Microplastics and Oxidative Stress—Current Problems and Prospects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Geng, J.; et al. Uptake and accumulation of polystyrene microplastics in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and toxic effects in liver. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4054–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Romano, N.; Galloway, T.; Hamzah, H. Virgin microplastics cause toxicity and modulate the impacts of phenanthrene on biomarker responses in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.K.A.; Chan, K.Y.K. Negative effects of microplastic exposure on growth and development of Crepidula onyx. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, L.; Peru, E.; Engler, A.; Ghiglione, J.F.; Meistertzheim, A.L.; Pruski, A.M.; et al. Macro- and microplastics affect cold-water corals growth, feeding and behaviour. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. The impact of polystyrene microplastics on feeding, function and fecundity in the marine copepod Calanus helgolandicus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besseling, E.; Wegner, A.; Foekema, E.M.; van den Heuvel-Greve, M.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Effects of microplastic on fitness and PCB bioaccumulation by the lugworm Arenicola marina (L.). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Besseling, E.; Foekema, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.; Ossendorp, B.C.; et al. Risks of plastic debris: Unravelling fact, opinion, perception, and belief. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 11513–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.E.; Hamann, M.; Kroon, F.J. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of microplastics in marine organisms: A review and meta-analysis of current data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USEPA. Microplastics Expert Workshop Report; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-03/documents/microplastics_expert_workshop_report_final_12-4-17.pdf(accessed on [Insert Date]).

- GESAMP. Proceedings of the GESAMP International Workshop on Assessing the Risks Associated with Plastics and Microplastics in the Marine Environment; Kershaw, P.J., Carney Almroth, B., Villarrubia-Gómez, P., Koelmans, A.A., Gouin, T., Eds.; IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP/ISA Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection: London, UK, 2020; GESAMP Reports and Studies No. 103, 68 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Dehaut, A.; Paul-Pont, I.; Lacroix, C.; Jezequel, R.; Soudant, P.; Duflos, G. Occurrence and Effects of Plastic Additives on Marine Environments and Organisms: A Review. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Guidelines for Exposure Assessment; Risk Assessment Forum, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; EPA/600/Z-92/001. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, P.; Nelson, K. Trophic Level Transfer of Microplastic: Mytilus edulis (L.) to Carcinus maenas (L.). Environ. Pollut. 2013, 177, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.E.; Galloway, T.S.; Godley, B.J.; Jarvis, D.S.; Lindeque, P.K. Investigating Microplastic Trophic Transfer in Marine Top Predators. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ward, J.E.; Danley, M.; Mincer, T.J. Field-Based Evidence for Microplastic in Marine Aggregates and Mussels: Implications for Trophic Transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11038–11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Straalen, N.M. Ecotoxicology Becomes Stress Ecology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 324A–330A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, C.E.W. Stress Ecology: Environmental Stress as Ecological Driving Force and Key Player in Evolution; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Palić, D. Micro- and Nano-Plastics Activation of Oxidative and Inflammatory Adverse Outcome Pathways. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, A.H. Microplastics in Decapod Crustaceans: Accumulation, Toxicity and Impacts, a Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 832, 154963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovzhenko, N.V.; Slobodskova, V.V.; Mazur, A.A.; Kukla, S.P.; Istomina, A.A.; Chelomin, V.P.; Beskhmelnov, D.D. Oxidative Stress in Mussel Mytilus trossulus Induced by Different-Sized Plastics. J. Xenobiotics 2024, 14, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomar, C.; Sureda, A.; Capó, X.; Guijarro, B.; Tejada, S.; Deudero, S. Microplastic Ingestion by Mullus surmuletus and Its Potential for Causing Oxidative Stress. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, C.; Esteban, M.Á.; Cuesta, A. Dietary Administration of PVC and PE Microplastics Produces Histological Damage, Oxidative Stress and Immunoregulation in European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 95, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomando, A.; Capó, X.; Alomar, C.; Álvarez, E.; Compa, M.; Valencia, J.M.; Pinya, S.; Deudero, S.; Sureda, A. Long-Term Exposure to Microplastics Induces Oxidative Stress and a Pro-Inflammatory Response in the Gut of Sparus aurata. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yu, Y.B.; Choi, J.H. Toxic Effects on Bioaccumulation, Hematological Parameters, Oxidative Stress, Immune Responses and Neurotoxicity in Fish Exposed to Microplastics: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowmer, T.; Kershaw, P. Proceedings of the GESAMP International Workshop on Micro-Plastic Particles as a Vector in Transporting Persistent, Bio-Accumulating and Toxic Substances in the Oceans; GESAMP Reports & Studies; UNESCO-IOC: Paris, France, 2010; 68 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowley, J.; Baker-Austin, C.; Porter, A.; Hartnell, R.; Lewis, C. Oceanic Hitchhikers—Assessing Pathogen Risks from Marine Microplastic. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.J.; Feiner, Z.S.; Malinich, T.D.; Höök, T.O. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Exposure to Microplastics on Fish and Aquatic Invertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, E.; Sureda, A.; Tejada, S.; Faggio, C. Microplastic in Marine Organism: Environmental and Toxicological Effects. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 64, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secci, G.; Parisi, G. From Farm to Fork: Lipid Oxidation in Fish Products. A Review. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 15, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.D.; Valencia, A.; Geffen, A.J. The Origin of Fulton’s Condition Factor: Setting the Record Straight. Fisheries 2006, 31, 236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, O.; Rosebrough, N.; Farr, A.; Randall, R. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V., Jr.; Featherstone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlateva, I.; Raykov, V.; Alexandrova, A.; Ivanova, P.; Chipev, N.; Stefanova, K.; Dzhembekova, N.; Doncheva, V.; Slabakova, V.; Stefanova, E.; et al. Effects of anthropogenic and environmental stressors on the current status of red mullet (Mullus barbatus L., 1758) populations inhabiting the Bulgarian Black Sea waters. Nature Conserv. 2023, 54, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaheb, I.; Hiroaki, T.; Ruby, R.M.; Teeluck, S.; Kawasaki, H.; Chineah, V. Basic Biostatistics for Marine Biologists; Coastal Fisheries Resources & Environment Conservation Project: 2001. ISBN 99903-22-12-0.

- Rodionov, S. A brief overview of the regime shift detection methods. In Large-Scale Disturbances (Regime Shifts) and Recovery in Aquatic Ecosystems: Challenges for Management Toward Sustainability; Velikova, V., Chipev, N., Eds.; UNESCO-ROSTE/BAS Workshop on Regime Shifts: Varna, Bulgaria, 2005; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov, S. A Sequential Method of Detecting Abrupt Changes in the Correlation Coefficient and Its Application to Bering Sea Climate. Climate 2015, 3, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regime Shift Test Website. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/regime-shift-test (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Holthuis, L.B. FAO Species Catalogue: Shrimps and Prawns of the World. An Annotated Catalogue of Species of Interest to Fisheries; FAO Fisheries Synopsis, 1980; Volume 1, p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, A. Different reproductive success at low salinity determines the estuarine distribution of two Palaemon prawn species. Ecol. Ser. 1985, 8, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ortegon, E.; Sargent, P.; Pohle, G.; Martinez-Lage, A. The Baltic prawn Palaemon adspersus Rathke, 1837 (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae): First record, possible establishment, and illustrated key of the subfamily Palaemoninae in northwest Atlantic waters. Aquat. Invasions 2015, 10, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Niu, S.; Wu, J. The role of algae in regulating the fate of microplastics: A review for processes, mechanisms, and influencing factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Jiang, R.; Craig, N.J.; Deng, H.; He, W.; Li, J.Y.; Su, L. Accumulation and re-distribution of microplastics via aquatic plants and macroalgae—A review of field studies. Mar. Environ. Res. 2023, 187, 105951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SeaLifeBase: Bittium reticulatum. Available online: https://www.sealifebase.se/summary/Bittium-reticulatum.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- FishBase: Sprattus sprattus. Available online: https://www.fishbase.se/summary/sprattus-sprattus.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Filgueiras, A.V.; Preciado, I.; Cartón, A.; Gago, J. Microplastic ingestion by pelagic and benthic fish and diet composition: A case study in the NW Iberian shelf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.B.; Pingki, F.H.; Azad, M.A.S.; Nur, A.-A.U.; Banik, P.; Paray, B.A.; Arai, T.; Yu, J. Microplastics in different tissues of a commonly consumed fish, Scomberomorus guttatus, from a large subtropical estuary: Accumulation, characterization, and contamination assessment. Biology 2023, 12, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keerthika, K.; Padmavathy, P.; Rani, V.; Jeyashakila, R.; Aanand, S.; Kutty, R.; Tamilselvan, R.; Subash, P. Microplastics accumulation in pelagic and benthic species along the Thoothukudi coast, South Tamil Nadu, India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 189, 114735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, P.J. Gobiidae. In Fishes of the Northeastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, Volume 3; Whitehead, P.J.P., Bauchot, M.-L., Hureau, J.-C., Nielsen, J., Tortonese, E., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 1019–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Hureau, J.-C. Mullidae. In Fishes of the Northeastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, Volume 2; Whitehead, P.J.P., Bauchot, M.-L., Hureau, J.-C., Nielsen, J., Tortonese, E., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 877–882. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, G.; Phukan, B.; Talukdar, A.; Ahmed, I.; Chutia, S.J.; Gogoi, R.; Sarma, J.; Ali, A.; Gowala, T.; Xavier, K.A.M. Assessment and quantification of microplastic contamination in fishes with different food habits from Beel wetlands. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasta, M.; Sattari, M.; Taleshi, M.S.; Namin, J.I. Microplastics in Different Tissues of Some Commercially Important Fish Species from Anzali Wetland in the Southwest Caspian Sea, Northern Iran. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xie, C.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, Z. Accumulation of Microplastics in Fish Guts and Gills from a Large Natural Lake: Selective or Non-Selective? Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremia, E.; Muscari Tomajoli, M.T.; Murano, C.; Petito, A.; Fasciolo, G. The Impact of Micro- and Nanoplastics on Aquatic Organisms: Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress and Implications for Human Health—A Review. Environments 2023, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subaramaniyam, U.; Allimuthu, R.S.; Vappu, S.; Ramalingam, D.; Balan, R.; Paital, B.; Panda, N.; Rath, P.K.; Ramalingam, N.; Sahoo, D.K. Effects of Microplastics, Pesticides and Nano-Materials on Fish Health, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense Mechanism. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1217666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urli, S.; Corte Pause, F.; Crociati, M.; Baufeld, A.; Monaci, M.; Stradaioli, G. Impact of Microplastics and Nanoplastics on Livestock Health: An Emerging Risk for Reproductive Efficiency. Animals 2023, 13, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Trojan Horse in the Intestine: A Review on the Biotoxicity of Microplastics Combined Environmental Contaminants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, G.; Fasciolo, G.; Venditti, P. The Ambiguous Aspects of Oxygen. Oxygen 2022, 2, 382–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Sonne, C.; Brown, R.J.C.; Younis, S.A.; Kim, K.H. Adsorption of Environmental Contaminants on Micro- and Nano-Scale Plastic Polymers and the Influence of Weathering Processes on Their Adsorptive Attributes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Cao, R.; Shang, E.; Zhang, W. ROS-Mediated Photoaging Pathways of Nano- and Micro-Plastic Particles under UV Irradiation. Water Res. 2022, 216, 118320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, D.; Meade, G.; Foley, V.M.; Dowd, C.A. Structure, Function and Evolution of Glutathione Transferases: Implications for Classification of Non-Mammalian Members of an Ancient Enzyme Superfamily. Biochem. J. 2001, 360, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samal, R.R.; Navani, H.S.; Saha, S.; Kisan, B.; Subudhi, U. Evidence of Microplastics Release from Polythene and Paper Cups Exposed to Hot and Cold: A Case Study on the Compromised Kinetics of Catalase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanacho, S.C.; Odo, G.E. Dietary Exposure to Polyvinyl Chloride Microparticles Induced Oxidative Stress and Hepatic Damage in Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21159–21173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Oxidative Stress in Liver Pathophysiology and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, M.J.; Gao, B. Hepatocytes: A Key Cell Type for Innate Immunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweidan, A.H.; El-Bendary, N.; Hegazy, O.M.; Hassanien, A.E.; Snasel, V. Water Pollution Detection System Based on Fish Gills as a Biomarker. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 65, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Lopes, C.; Oliveira, P.; Bessa, F.; Otero, V.; Henriques, B.; Raimundo, J.; Caetano, M.; Vale, C.; Guilhermino, L. Microplastics in Wild Fish from North East Atlantic Ocean and Its Potential for Causing Neurotoxic Effects, Lipid Oxidative Damage, and Human Health Risks Associated with Ingestion Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 134625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAMP. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Global Assessment; Kershaw, P.J., Ed.; Rep. Stud. GESAMP No. 90, 96 pp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Syberg, K.; Khan, F.R.; Selck, H.; Palmqvist, A.; Banta, G.T.; Daley, J.; Sano, L.; Duhaime, M.B. Microplastics: Addressing Ecological Risk through Lessons Learned. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson-Wright, W.M.; Wells, P.G.; Duce, R.A.; Gilardi, K.V.; Girvan, A.S.T.; Huber, M.E.; Kershaw, P.J.; Linders, J.B.H.J.; Luit, R.J.; Vivian, C.M.G.; Vousden, D.H. The UN Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP)—An Ocean Science-Policy Interface Standing the Test of Time. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 199, 115917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | W | L | ST weight | MPs | ||

| gr | Cm | gr | %FO in ST | particles/ST | particles/g ST | |

| M. galloprovincialis | 13.62b,c,d,e ±3.30 |

6.04c ±0.42 |

4.04b,c,d,e ±0.95 |

63.33 | 1.13e ±1.11 |

0.320 ±0.31 |

| R. venosa | 37.87a,c,d,e ±6.31 |

5.78c ±0.35 |

11.87a,c,e ±2.33 |

46.67 | 0.60e ±0.83 |

0.050 ±0.07 |

| B. reticulatum | 0.051a,b,d,e ±0.010 |

1.09a,b,d ±0.098 |

0.01a,b,e ±0.03 |

83.33 | 0.30e ±0.19 |

0.0033 ±0.0025 |

| P. adspersus | 1.54a,b,c,e ±0.66 |

5.86c ±1.02 |

- | 70.00 | 1.37e ±1.27 |

0.990 ±1.09 |

| M. gigas | 136.21a,b,c,,d ±19.72 |

11.8 ±0.76 |

22.2 a,b,c,d ±4.54 |

66.67 | 100.5 ±87.36 |

4.530 ±11.08 |

| W | L | GIT weight | MPs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | gr | cm | gr | %FO in GIT |

%FO in muscle | particles/ GIT |

particles/g muscle |

| M. batrachocephalus | 90.5b,c ±24.37 |

21.32b,c ±1.83 |

7.57b,c ±4.18 |

53.3c | 26.7c | 0.80 ±1.08 |

0.24c ±0.44 |

| M. barbatus | 21.64a,c ±6.68 |

12.55a ±1.11 |

1.21a,c ±0.34 |

46.7 | 33.4 | 0.93 ±1.16 |

0.27c ±0.48 |

| S. sprattus | 4.19a,b ±0.80 |

9.12a ±0.47 |

0.17a,b ±0.07 |

33.4a | 46.5a | 0.40 ±0.63 |

2.01a,b ±2.56 |

| LPO | GSH | SOD | CAT | GPX | GR | GST | AChE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | nM/mg protein | ng/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein | U/mg protein |

| M. galloprovincialis | 3.69b,c,d | 93.39c | 21.72b,d | 0.63a,b,c,d | 8.92c | 12.78b,d,e | 13.86a,b,c,d | 33.72b,c,d |

| ±0.33 | ±9.75 | ±1.05 | ±0.07 | ±0.43 | ±1.23 | ±2.00 | ±1.60 | |

| R. venosa | 0.37a,c,d | 118.5 | 32.81a,c,d | 1.30a,b,d | 8.48c | 20.40a,b,d | 323.62a,b,c,d,e | 181.56a,d,e |

| ±0.04 | ±69.60 | ±2.86 | ±0.23 | ±1.57 | ±5.17 | ±10.72 | ±22.67 | |

| B. reticulatum | 1.51a,b,d | 130.9a,d | 23.56b,d | 1.01a,c,d | 17.92ab,d | 12.12d,e | 86.70a,b,c,e | 293.52a,d,e |

| ±0.03 | ±2.74 | ±0.48 | ±0.12 | ±1.20 | ±1.27 | ±1.73 | ±16.31 | |

| P. adspersus | 6.32a,b,c | 84.24c | 5.31a,b,c | 0.12a,b,c,e | 8.03c | 1.48a,b,c,d,e | 34.65a,b,c | 47.51a,b,c |

| ±1.13 | ±4.69 | ±0.55 | ±0.01 | ±0.99 | ±0.15 | ±4.00 | ±5.70 | |

| M. gigas |

5.38b,c ±1.22 |

266.55a,b,c,d ±62.79 |

74.60a,b,c,d ±7.82 |

0.72d ±0.09 |

14.90a,b,d ±1.56 |

23.81a,c,d ±1.61 |

33.10a,b,c, ±3.44 |

40.00b,c ±6.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).