Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

19 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

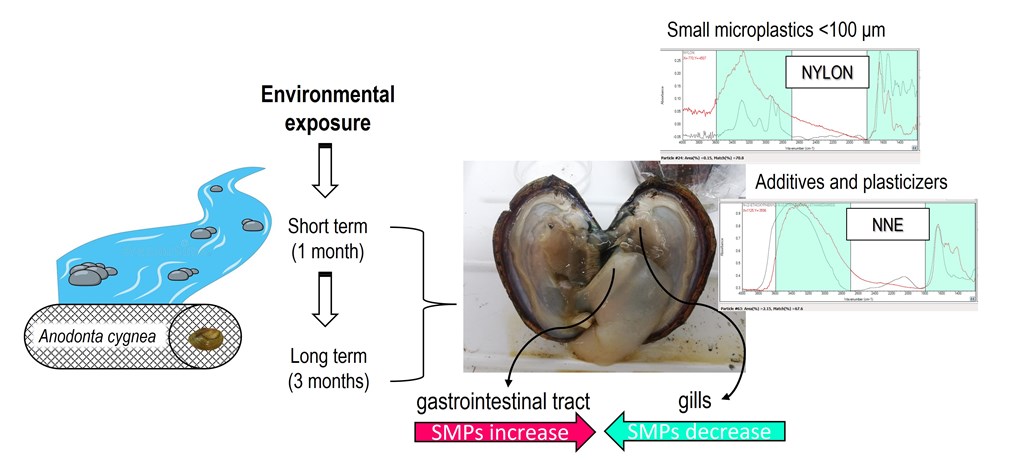

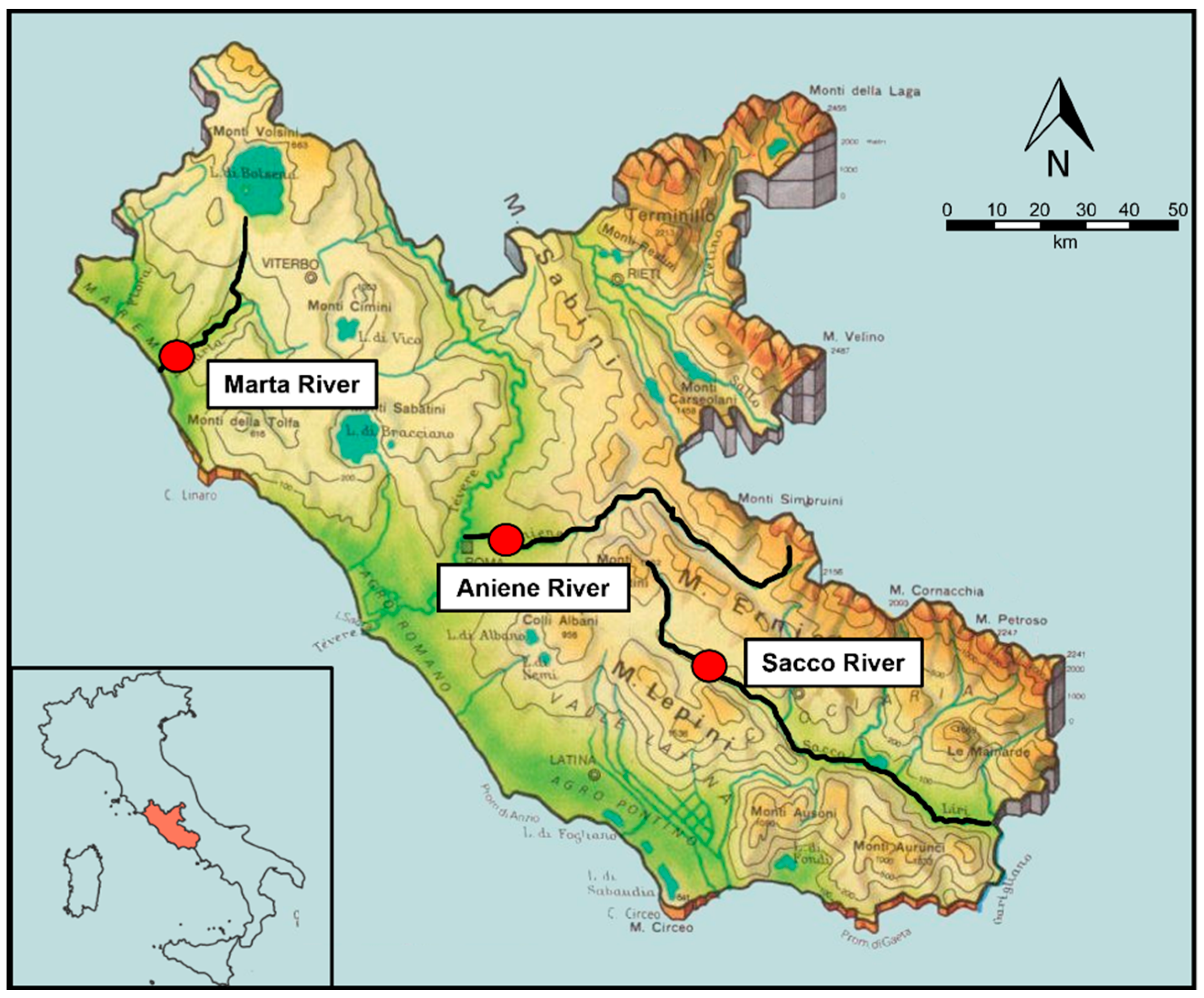

2.1. Experimental design and environmental exposure of bivalves

2.2. Quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC)

2.3. Dissection of gills and gastrointestinal tracts

2.4. SMPs and APFs extraction procedures and analysis via Micro-FTIR

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

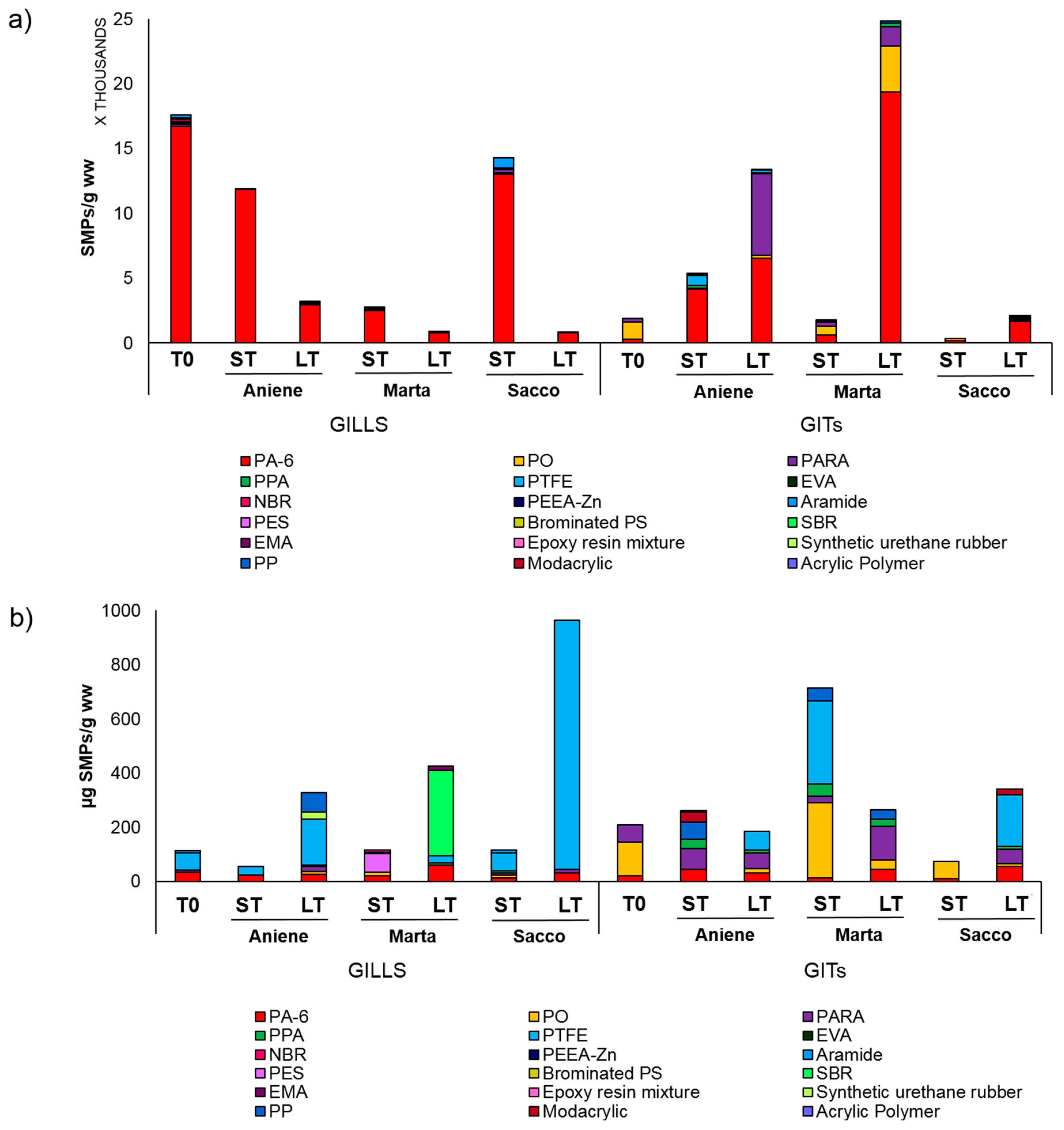

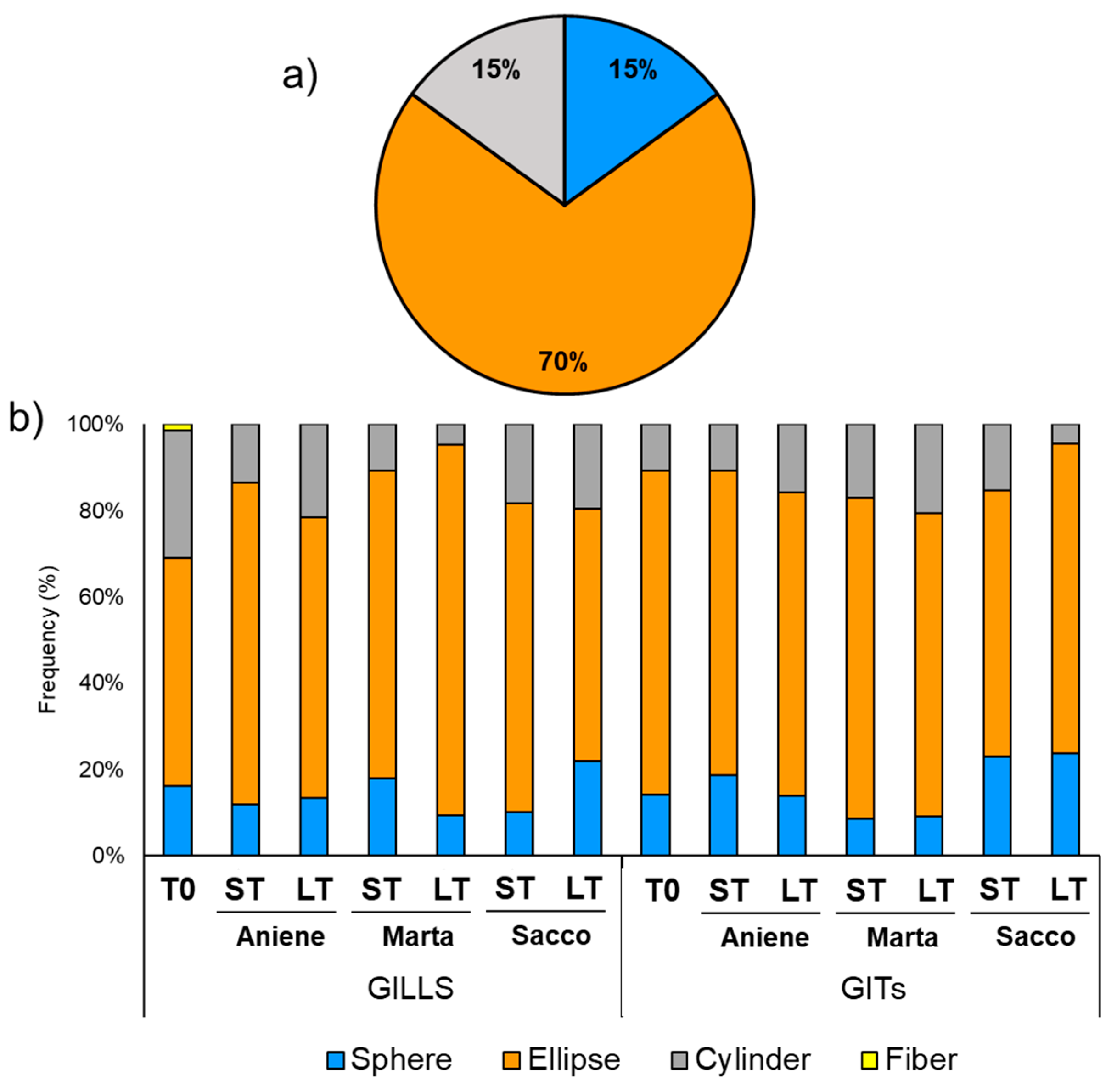

3.1. SMPs uptake and ingestion by Anodonta cygnea

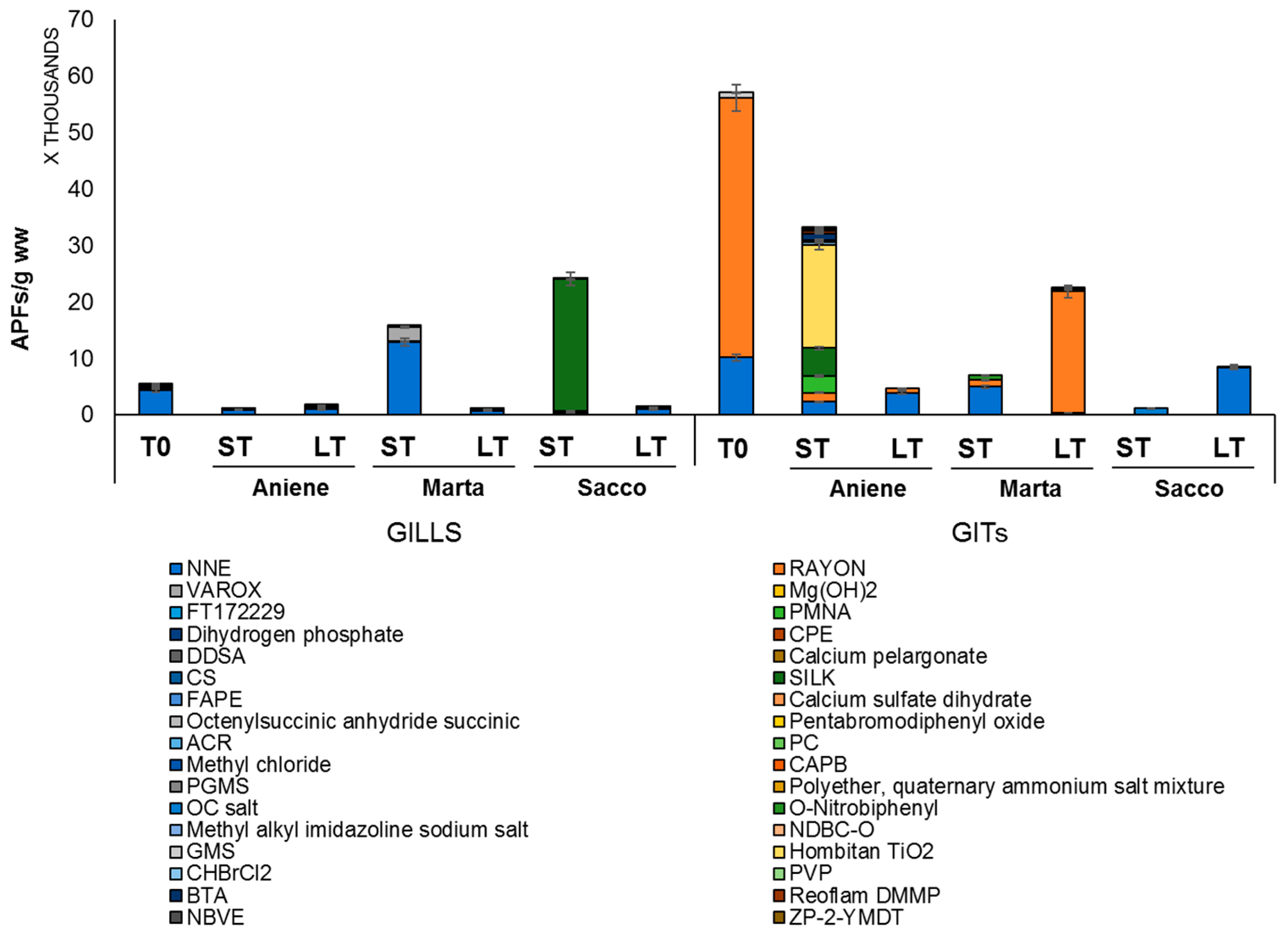

3.2. AFPs uptake and ingestion by Anodonta cygnea

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Information

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

Ethics Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

References

- Cera, A.; Cesarini, G.; Scalici, M. Microplastics in Freshwater: What Is the News from the World? Diversity 2020, 12, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Shang, L.; Zhong, R. Microplastic Pollution in Soils, Plants, and Animals: A Review of Distributions, Effects and Potential Mechanisms. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 850, 157857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Shen, M.; Tang, W. Wet Wipes and Disposable Surgical Masks Are Becoming New Sources of Fiber Microplastic Pollution during Global COVID-19. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cera, A., Gallitelli, L., Cesarini, G., Scalici, M., 2022. Occurrence of microplastics in freshwater. In Microplastic Pollution: Environmental Occurrence and Treatment Technologies; Hashmi, M.Z., Ed.; Emerging Contaminants and Associated Treatment Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022, pp. 201–226. [CrossRef]

- Munyaneza, J.; Jia, Q.; Qaraah, F.A.; Hossain, M.F.; Wu, C.; Zhen, H.; Xiu, G. A Review of Atmospheric Microplastics Pollution: In-Depth Sighting of Sources, Analytical Methods, Physiognomies, Transport and Risks. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 822, 153339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, Z.; Cesarini, G.; Orsini, M.; De Santis, S.; Scalici, M. Uptake of Microplastics in the Wedge Clam Donax Trunculus: First Evidence from the Mediterranean Sea. Water 2022, 14, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, F.M.; Durance, I.; Horton, A.A.; Thompson, R.C.; Tyler, C.R.; Ormerod, S.J. A Catchment-scale Perspective of Plastic Pollution. Glob Change Biol 2019, 25, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.M.; Windsor, F.M.; Santillo, D.; Ormerod, S.J. Food Web Transfer of Plastics to an Apex Riverine Predator. Glob Change Biol 2020, 26, 3846–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ma, J.; Ji, R.; Pan, K.; Miao, A.-J. Microplastics in Aquatic Environments: Occurrence, Accumulation, and Biological Effects. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 703, 134699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, F.; O’Brien, J.W.; Galloway, T.; Thomas, K.V. Accumulation and Fate of Nano- and Micro-Plastics and Associated Contaminants in Organisms. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 111, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jâms, I.B.; Windsor, F.M.; Poudevigne-Durance, T.; Ormerod, S.J.; Durance, I. Estimating the Size Distribution of Plastics Ingested by Animals. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corami, F.; Rosso, B.; Roman, M.; Picone, M.; Gambaro, A.; Barbante, C. Evidence of Small Microplastics (<100 Μm) Ingestion by Pacific Oysters (Crassostrea Gigas): A Novel Method of Extraction, Purification, and Analysis Using Micro-FTIR. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2020, 160, 111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corami, F.; Rosso, B.; Iannilli, V.; Ciadamidaro, S.; Bravo, B.; Barbante, C. Occurrence and Characterization of Small Microplastics (<100 Μm), Additives, and Plasticizers in Larvae of Simuliidae. Toxics 2022, 10, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.A.; Underwood, A.J.; Chapman, M.G.; Williams, R.; Thompson, R.C.; Van Franeker, J.A. Linking Effects of Anthropogenic Debris to Ecological Impacts. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2015, 282, 20142929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sá, L.C.; Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, F.; Rocha, T.L.; Futter, M.N. Studies of the Effects of Microplastics on Aquatic Organisms: What Do We Know and Where Should We Focus Our Efforts in the Future? Science of The Total Environment 2018, 645, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, G.; Purvaja, R.; Anandavelu, I.; Robin, R.S.; Ramesh, R. Accumulation and Ecotoxicological Risk of Weathered Polyethylene (WPE) Microplastics on Green Mussel (Perna Viridis). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 208, 111765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilhermino, L.; Vieira, L.R.; Ribeiro, D.; Tavares, A.S.; Cardoso, V.; Alves, A.; Almeida, J.M. Uptake and Effects of the Antimicrobial Florfenicol, Microplastics and Their Mixtures on Freshwater Exotic Invasive Bivalve Corbicula Fluminea. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 622–623, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.; Barboza, L.G.A.; Branco, V.; Figueiredo, N.; Carvalho, C.; Guilhermino, L. Effects of Microplastics and Mercury in the Freshwater Bivalve Corbicula Fluminea (Müller, 1774): Filtration Rate, Biochemical Biomarkers and Mercury Bioconcentration. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 164, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.F.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Boegehold, A.G.; Peraino, N.J.; Westrick, J.A.; Kashian, D.R. Microplastic Ingestion by Quagga Mussels, Dreissena Bugensis, and Its Effects on Physiological Processes. Environmental Pollution 2020, 260, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zettler, E.R.; Mincer, T.J.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. Life in the “Plastisphere”: Microbial Communities on Plastic Marine Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7137–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Xue, J. Biofilm-Developed Microplastics As Vectors of Pollutants in Aquatic Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, acs.est.1c04466. [CrossRef]

- Beiras, R.; Verdejo, E.; Campoy-López, P.; Vidal-Liñán, L. Aquatic Toxicity of Chemically Defined Microplastics Can Be Explained by Functional Additives. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 406, 124338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lusher, A.L.; Rotchell, J.M.; Deudero, S.; Turra, A.; Bråte, I.L.N.; Sun, C.; Shahadat Hossain, M.; Li, Q.; Kolandhasamy, P.; et al. Using Mussel as a Global Bioindicator of Coastal Microplastic Pollution. Environmental Pollution 2019, 244, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.; Orlando-Bonaca, M. Perspectives on Using Marine Species as Bioindicators of Plastic Pollution. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 137, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Vlachogianni, T.; Galgani, F.; Innocenti, F.D.; Zampetti, G.; Leone, G. Assessing and Mitigating the Harmful Effects of Plastic Pollution: The Collective Multi-Stakeholder Driven Euro-Mediterranean Response. Ocean & Coastal Management 2020, 184, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoca, M.S.; Kühn, S.; Sun, C.; Avery-Gomm, S.; Choy, C.A.; Dudas, S.; Hong, S.H.; Hyrenbach, K.D.; Li, T.-H.; Ng, C.K.; et al. Towards a North Pacific Ocean Long-Term Monitoring Program for Plastic Pollution: A Review and Recommendations for Plastic Ingestion Bioindicators. Environmental Pollution 2022, 310, 119861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Cai, H.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Wu, C.; Rochman, C.M.; Shi, H. Using the Asian Clam as an Indicator of Microplastic Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems. Environmental Pollution 2018, 234, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strehse, J.S.; Maser, E. Marine Bivalves as Bioindicators for Environmental Pollutants with Focus on Dumped Munitions in the Sea: A Review. Marine Environmental Research 2020, 158, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beone, G.M.; Ravera, O. Vantaggi e limiti del monitoraggio ambientale mediante l’analisi chimica dei Lamelli- branchi. 2003.

- Lopes-Lima, M. Anodonta cygnea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T156066A21400900, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Killeen, I., Aldridge, D., Oliver, G. Freshwater bivalves of Britain and Ireland. National Museum of Wales Occasional Publication 2004, 82, 1 – 114.

- Zając, K. Habitat preferences of swan mussel Anodonta cygnea (Linnaeus 1758) (Bivalvia, Unionidae) in relation to structure and successional stage of floodplain waterbodies. Ekologia (Bratislava) 2002, 21, 345 – 355.

- Rosińska et al. 2008.

- Kryger, J.; Riisgard, H.U. Filtration Rate Capacities in 6 Species of European Freshwater Bivalves. Oecologia 1988, 77, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, R.; Shariati, F.P.; Tavakoli, O.; Ehteshami, F. Fabrication of a New Reactor Design to Apply Freshwater Mussel Anodonta Cygnea for Biological Removal of Water Pollution. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkola, A.; Krause, S.; Lynch, I.; Sambrook Smith, G.H.; Nel, H. Nano and Microplastic Interactions with Freshwater Biota – Current Knowledge, Challenges and Future Solutions. Environment International 2021, 152, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceschin, S.; Zuccarello, V.; Caneva, G. Role of Macrophyte Communities as Bioindicators of Water Quality: Application on the Tiber River Basin (Italy). Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology 2010, 144, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini et al., 2012.

- Al-Azzawi, M.S.M.; Kefer, S.; Weißer, J.; Reichel, J.; Schwaller, C.; Glas, K.; Knoop, O.; Drewes, J.E. Validation of Sample Preparation Methods for Microplastic Analysis in Wastewater Matrices—Reproducibility and Standardization. Water 2020, 12, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corami, F.; Rosso, B.; Bravo, B.; Gambaro, A.; Barbante, C. A Novel Method for Purification, Quantitative Analysis and Characterization of Microplastic Fibers Using Micro-FTIR. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathalon, A.; Hill, P. Microplastic Fibers in the Intertidal Ecosystem Surrounding Halifax Harbor, Nova Scotia. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2014, 81, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Occurrence and Ecological Impact of Microplastics in Aquaculture Ecosystems. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ndungu, A.W.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Microplastics Pollution in Inland Freshwaters of China: A Case Study in Urban Surface Waters of Wuhan, China. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 575, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battulga, B.; Kawahigashi, M.; Oyuntsetseg, B. Distribution and Composition of Plastic Debris along the River Shore in the Selenga River Basin in Mongolia. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 26, 14059–14072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Du, C.; Jiang, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Hu, S.; Feng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Comparison of the Abundance of Microplastics between Rural and Urban Areas: A Case Study from East Dongting Lake. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crew, A.; Gregory-Eaves, I.; Ricciardi, A. Distribution, Abundance, and Diversity of Microplastics in the Upper St. Lawrence River. Environmental Pollution 2020, 260, 113994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tian, M.; Jin, F.; Chen, M.; Liu, Z.; He, S.; Li, F.; Yang, L.; Fang, C.; Mu, J. Coupled Effects of Urbanization Level and Dam on Microplastics in Surface Waters in a Coastal Watershed of Southeast China. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2020, 154, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarini, G.; Scalici, M. Riparian Vegetation as a Trap for Plastic Litter. Environmental Pollution 2022, 292, 118410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domogalla-Urbansky, J.; Anger, P.M.; Ferling, H.; Rager, F.; Wiesheu, A.C.; Niessner, R.; Ivleva, N.P.; Schwaiger, J. Raman Microspectroscopic Identification of Microplastic Particles in Freshwater Bivalves (Unio Pictorum) Exposed to Sewage Treatment Plant Effluents under Different Exposure Scenarios. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 26, 2007–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudrimont, M.; Arini, A.; Guégan, C.; Venel, Z.; Gigault, J.; Pedrono, B.; Prunier, J.; Maurice, L.; Ter Halle, A.; Feurtet-Mazel, A. Ecotoxicity of Polyethylene Nanoplastics from the North Atlantic Oceanic Gyre on Freshwater and Marine Organisms (Microalgae and Filter-Feeding Bivalves). Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 3746–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C.C.; Hakenkamp, C.C. The Functional Role of Burrowing Bivalves in Freshwater Ecosystems: Functional Role of Bivalves. Freshwater Biology 2001, 46, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreschi, A.C.; Callil, C.T.; Christo, S.W.; Ferreira Junior, A.L.; Nardes, C.; De Faria, É.; Girard, P. Filtration, Assimilation and Elimination of Microplastics by Freshwater Bivalves. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2020, 2, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, S.; Gagné, F.; André, C.; Della Torre, C.; Auclair, J.; Hanana, H.; Parenti, C.C.; Bonasoro, F.; Binelli, A. Evaluation of Uptake and Chronic Toxicity of Virgin Polystyrene Microbeads in Freshwater Zebra Mussel Dreissena Polymorpha (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Science of The Total Environment 2018, 631–632, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Feng, C.; Pang, W.; Tian, C.; Zhao, Y. Nanoplastic-Induced Genotoxicity and Intestinal Damage in Freshwater Benthic Clams ( Corbicula Fluminea ): Comparison with Microplastics. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9469–9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Xi, M.; Nicholaus, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Kong, F.; Yu, Z. Behaviors and Biochemical Responses of Macroinvertebrate Corbicula Fluminea to Polystyrene Microplastics. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 813, 152617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, K.S.; Graf, D.L. Mollusca Bivalvia. Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates.

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B. Investigating Microplastics Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification in Seafood from the Persian Gulf: A Threat to Human Health? Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 2019, 36, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; Da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental Exposure to Microplastics: An Overview on Possible Human Health Effects. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchetti, S.V.; La Spina, R.; Fumagalli, F.; Riccardi, N.; Gilliland, D.; Ponti, J. Detection of Metal-Doped Fluorescent PVC Microplastics in Freshwater Mussels. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolandhasamy, P.; Su, L.; Li, J.; Qu, X.; Jabeen, K.; Shi, H. Adherence of Microplastics to Soft Tissue of Mussels: A Novel Way to Uptake Microplastics beyond Ingestion. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 610–611, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Jeckel, N.; Weil, C.; Umbach, S.; Brennholt, N.; Reifferscheid, G.; Wagner, M. Ingestion and Toxicity of Polystyrene Microplastics in Freshwater Bivalves. Environ Toxicol Chem 2021, 40, 2247–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.K.; Spanjer, A.R.; Rosen, M.R.; Thom, T. Microplastics in Lake Mead National Recreation Area, USA: Occurrence and Biological Uptake. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, T.; Goordiyal, K.; Glassom, D. Are Nitric Acid (HNO3) Digestions Efficient in Isolating Microplastics from Juvenile Fish? Water Air Soil Pollut 2017, 228, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munno, K.; Helm, P.A.; Jackson, D.A.; Rochman, C.; Sims, A. Impacts of Temperature and Selected Chemical Digestion Methods on Microplastic Particles. Environ Toxicol Chem 2018, 37, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, A.F.; Basque, K.; Maltby, E.A.; Hodgson, M.; Nicholson, A.; Wilson, E.; Stuart, R.; Smith-Palmer, T.; Wyeth, R.C. Effectiveness of Several Commercial Non-Toxic Antifouling Technologies for Aquaculture Netting at Reducing Mussel Biofouling. Aquaculture 2021, 543, 736968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. Release of Synthetic Microplastic Plastic Fibres from Domestic Washing Machines: Effects of Fabric Type and Washing Conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2016, 112, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigalke, M.; Fieber, M.; Foetisch, A.; Reynes, J.; Tollan, P. Microplastics in Agricultural Drainage Water: A Link between Terrestrial and Aquatic Microplastic Pollution. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, Md.M.; Nupur, F.Y.; Parvin, F.; Tareq, S.M. Occurrence and Characteristics of Microplastic in Different Types of Industrial Wastewater and Sludge: A Potential Threat of Emerging Pollutants to the Freshwater of Bangladesh. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2022, 8, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Abbasi, S.; Pourmahmood, H.; Oleszczuk, P.; Ritsema, C.; Turner, A. Microplastics in Agricultural Soils from a Semi-Arid Region and Their Transport by Wind Erosion. Environmental Research 2022, 212, 113213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, V.; Corami, F.; Grasso, P.; Lecce, F.; Buttinelli, M.; Setini, A. Plastic Abundance and Seasonal Variation on the Shorelines of Three Volcanic Lakes in Central Italy: Can Amphipods Help Detect Contamination? Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 14711–14722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfriso, A.A.; Tomio, Y.; Rosso, B.; Gambaro, A.; Sfriso, A.; Corami, F.; Rastelli, E.; Corinaldesi, C.; Mistri, M.; Munari, C. Microplastic Accumulation in Benthic Invertebrates in Terra Nova Bay (Ross Sea, Antarctica). Environment International 2020, 137, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Pérez, C.; Amezcua, F.; Rosales-Valencia, A.; Green, L.; Pollorena-Melendrez, J.E.; Sarmiento-Martínez, M.A.; Tomita Ramírez, I.; Gil-Manrique, B.D.; Hernandez-Lozano, M.Y.; Muro-Torres, V.M.; et al. First Insight into Plastics Ingestion by Fish in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 171, 112705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Xue, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Li, D.; Shi, H. Microplastics in Taihu Lake, China. Environmental Pollution 2016, 216, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, K.A.; Hodgson, D.J.; Clark, P.F.; Morritt, D. The Effects of Wet Wipe Pollution on the Asian Clam, Corbicula Fluminea (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in the River Thames, London. Environmental Pollution 2020, 264, 114577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, E.; Fogelberg, V.; Nilsson, P.A.; Hollander, J. Microplastics in a Freshwater Mussel (Anodonta anatina) in Northern Europe. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 697, 134192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastorino, P.; Prearo, M.; Anselmi, S.; Menconi, V.; Bertoli, M.; Dondo, A.; Pizzul, E.; Renzi, M. Use of the Zebra Mussel Dreissena polymorpha (Mollusca, Bivalvia) as a Bioindicator of Microplastics Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems: A Case Study from Lake Iseo (North Italy). Water 2021, 13, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, R.S.; Spaccesi, F.; Gómez, N. First Record of Microplastics in the Mussel Limnoperna Fortunei. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2020, 38, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsching, K.J.; Duan, P.; Alberts, E.M.; Tibabuzo Perdomo, A.M.; Kenny, P.; Wilker, J.J.; Schmidt-Rohr, K. Silk-Like Protein with Persistent Radicals Identified in Oyster Adhesive by Solid-State NMR. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 2840–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An Overview of Chemical Additives Present in Plastics: Migration, Release, Fate and Environmental Impact during Their Use, Disposal and Recycling. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Xu, P.; Zhu, B.; Bai, M.; Li, D. Microplastics in Freshwater River Sediments in Shanghai, China: A Case Study of Risk Assessment in Mega-Cities. Environmental Pollution 2018, 234, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzeh, M.; Sunahara, G.I. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity Studies of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Nanoparticles in Chinese Hamster Lung Fibroblast Cells. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Lao, Y.; Lv, X.; Tao, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Cai, Z. TiO2 Nanoparticles in the Marine Environment: Physical Effects Responsible for the Toxicity on Algae Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 565, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.; Forleo, A.; Ferramosca, A.; Notari, T.; Pappalardo, S.; Siciliano, P.; Capone, S.; Montano, L. Blood, Urine and Semen Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Pattern Analysis for Assessing Health Environmental Impact in Highly Polluted Areas in Italy. Environmental Pollution 2021, 286, 117410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiras, R.; Bellas, J.; Cachot, J.; Cormier, B.; Cousin, X.; Engwall, M.; Gambardella, C.; Garaventa, F.; Keiter, S.; Le Bihanic, F.; et al. Ingestion and Contact with Polyethylene Microplastics Does Not Cause Acute Toxicity on Marine Zooplankton. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2018, 360, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Besseling, E.; Foekema, E.M. Leaching of Plastic Additives to Marine Organisms. Environmental Pollution 2014, 187, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale; Massarelli; Savino; Locaputo; Uricchio A Detailed Review Study on Potential Effects of Microplastics and Additives of Concern on Human Health. IJERPH 2020, 17, 1212. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).