Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

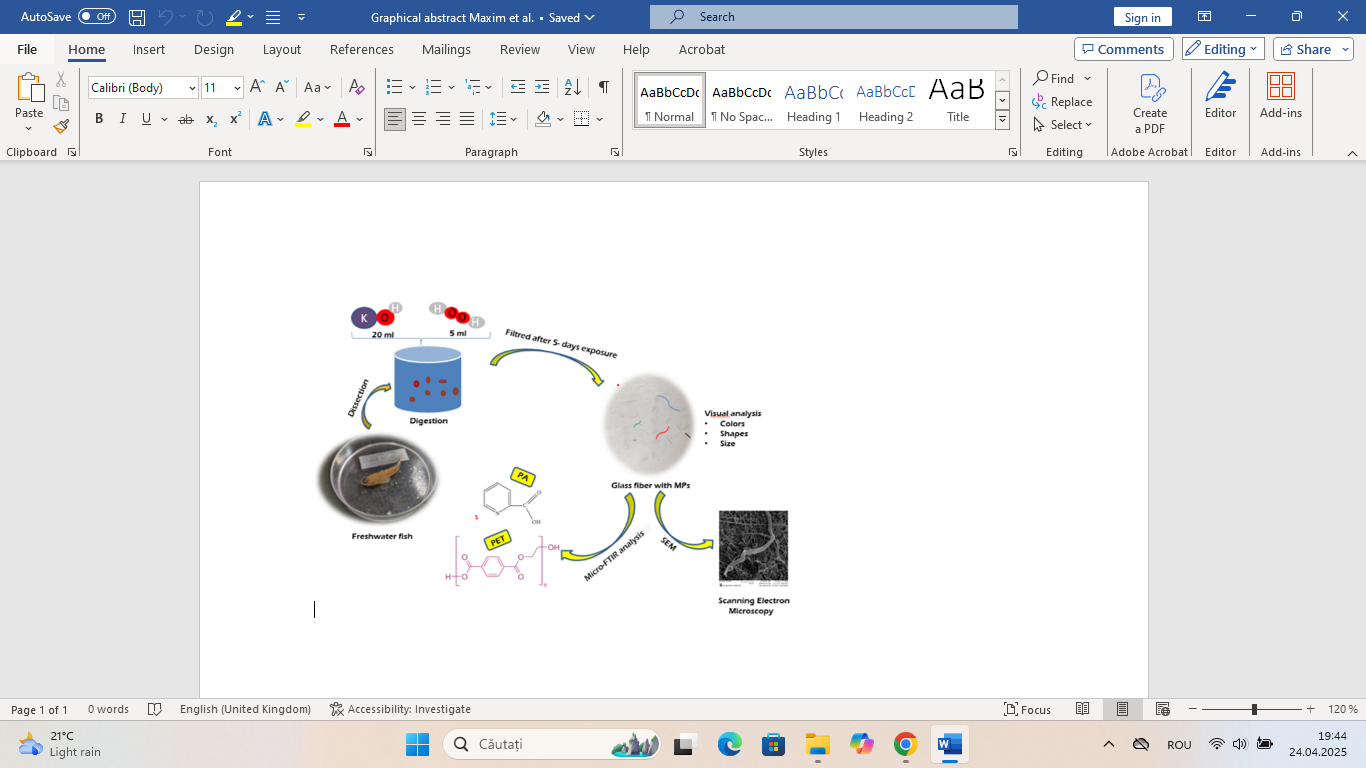

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field and Laboratory Methods

2.3. Micro-and Mesoplastics Isolation, Identification, and Characterization

2.4. Quality Control and Quality Assurance Measures

2.5. Quantification of MPs from Different Matrices

3. Results

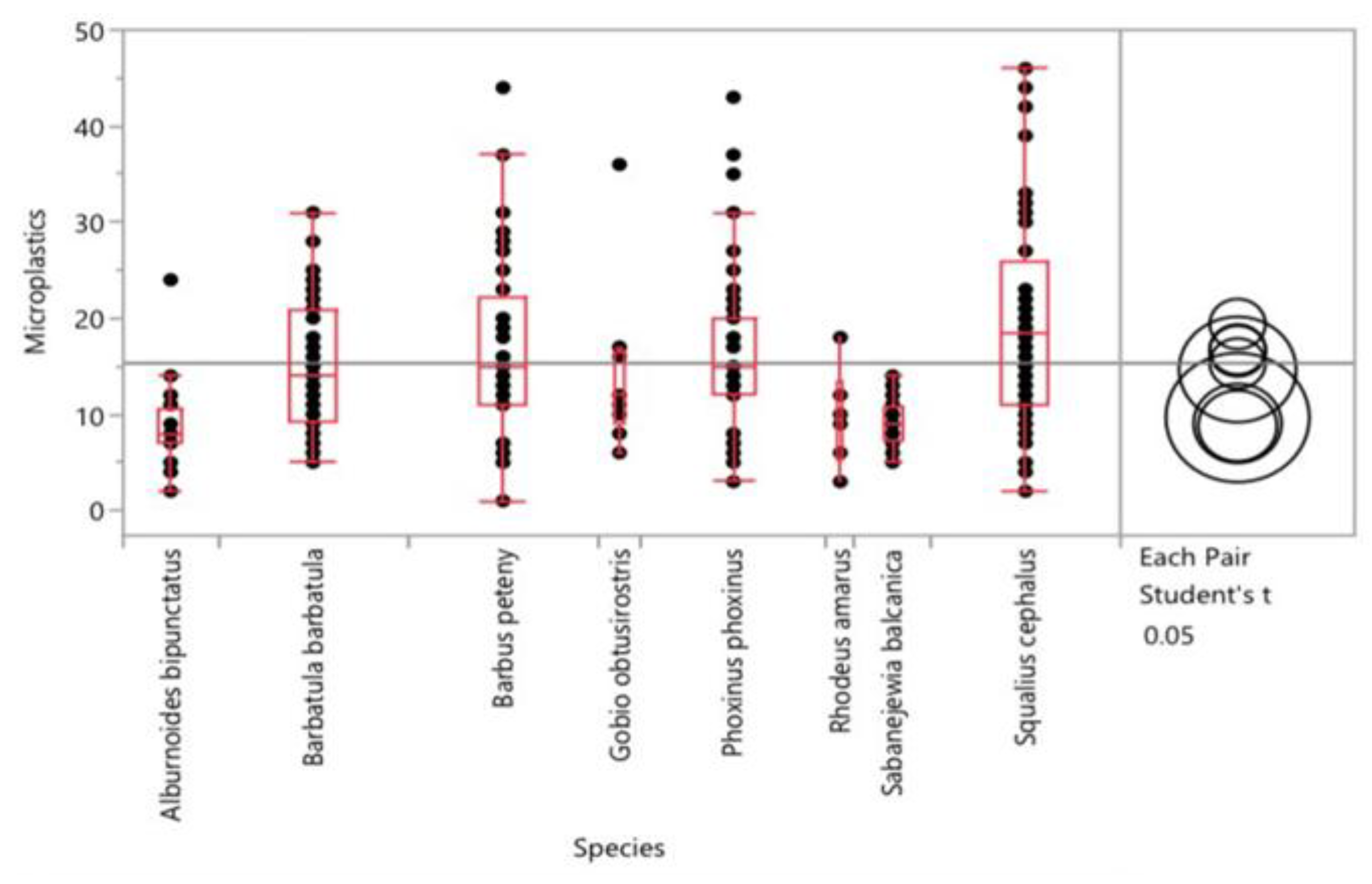

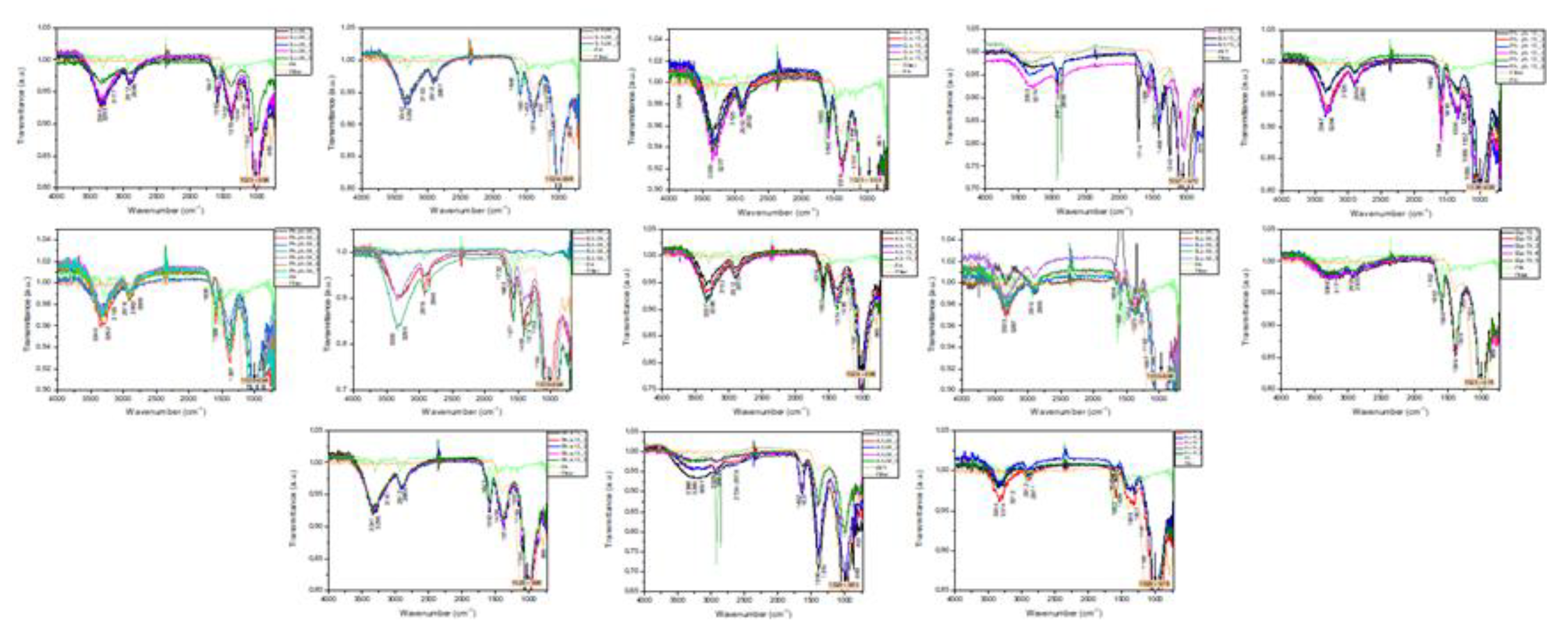

| Species | Squalius cephalus (2004) | Squalius cephalus (2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic characteristics | No. of items | No. of items | |

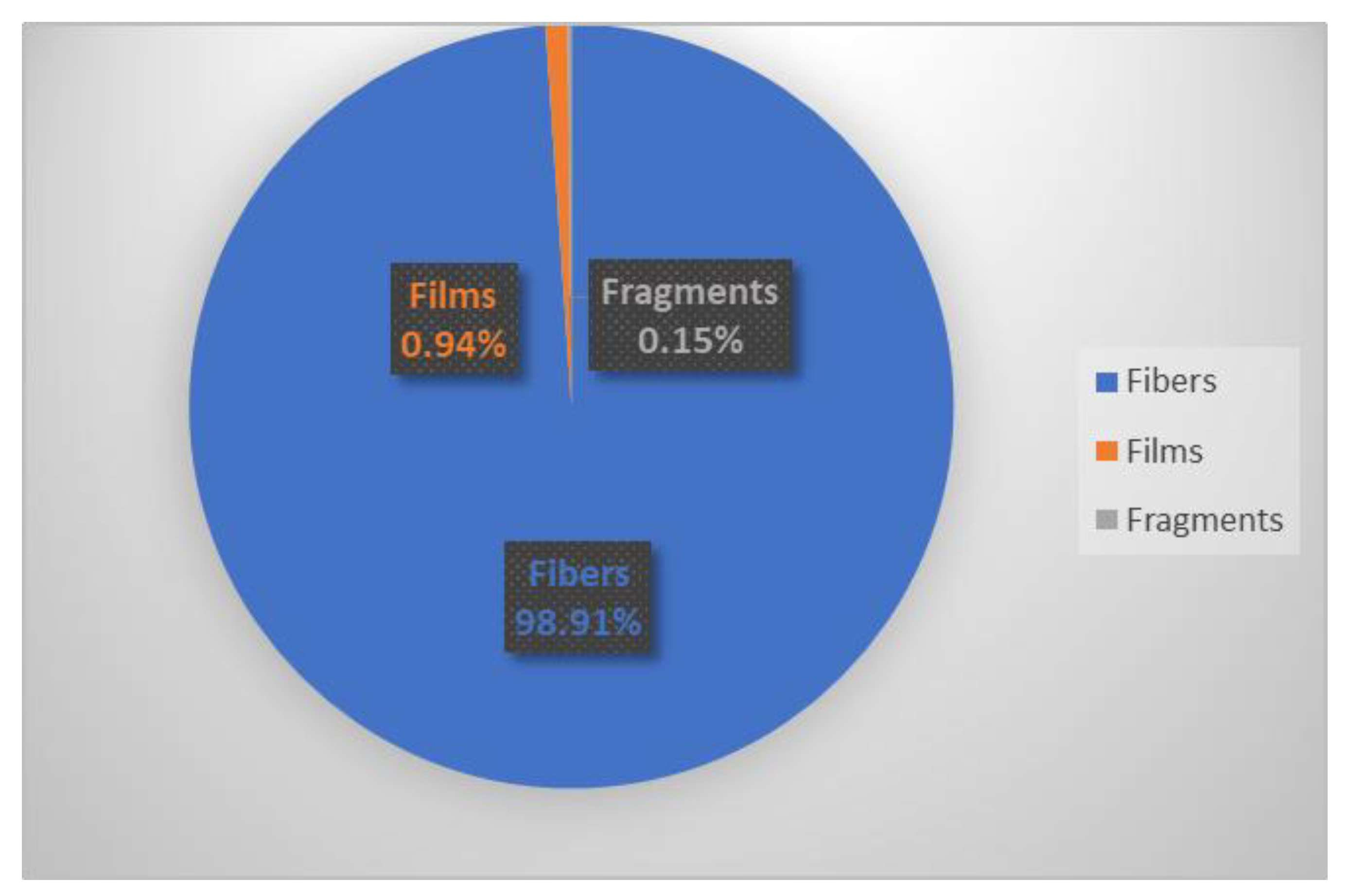

| Shape | Fibers | 478 | 295 |

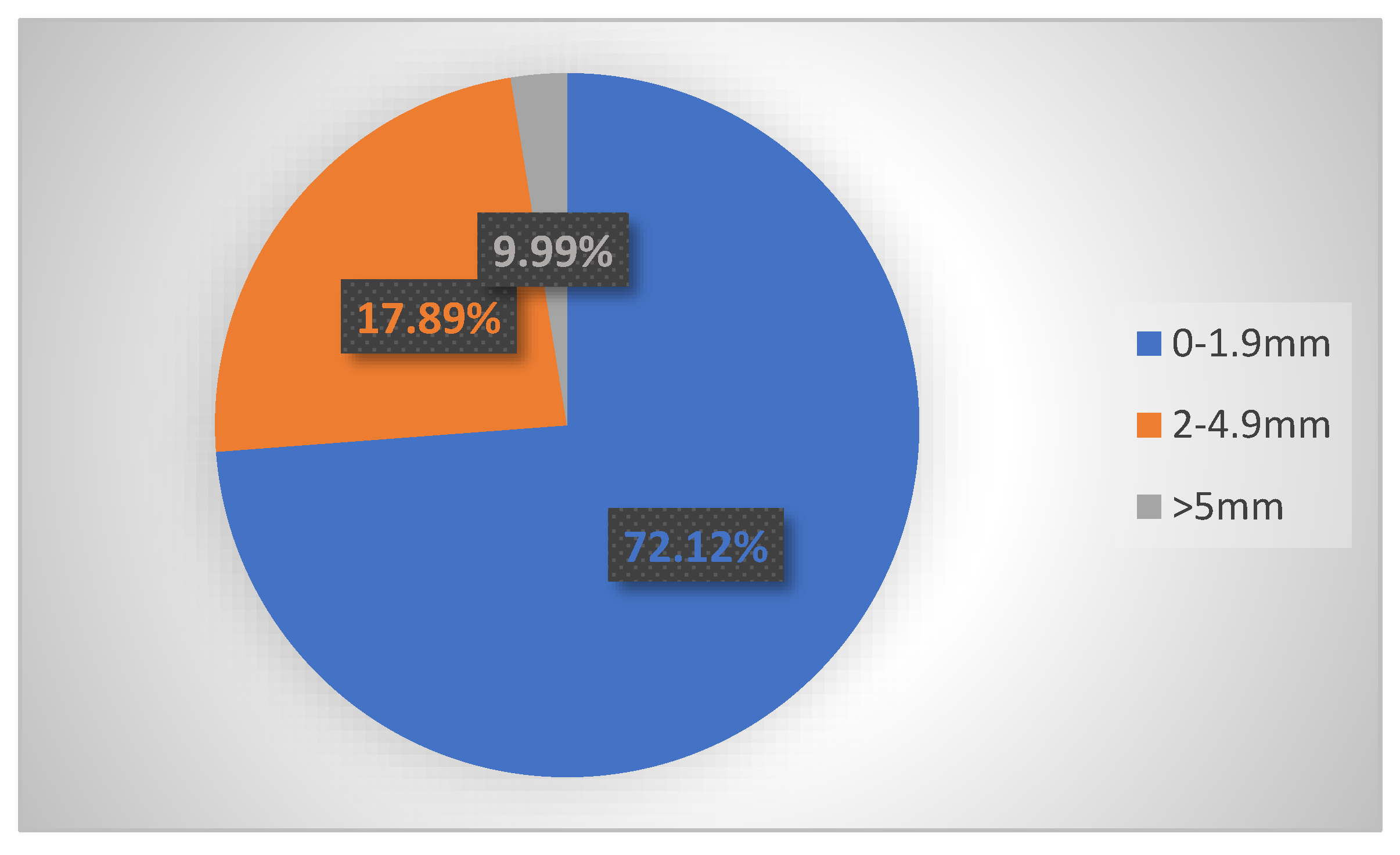

| Size | 0-0.9 mm | 318 | 132 |

| 1-1.9 mm | 95 | 107 | |

| 2-2.9 mm | 36 | 32 | |

| 3-4.9 mm | 19 | 15 | |

| 5-10 mm | 10 | 8 | |

| >10 mm | 0 | 1 | |

| Average size | 1.01 mm | 1.47 mm | |

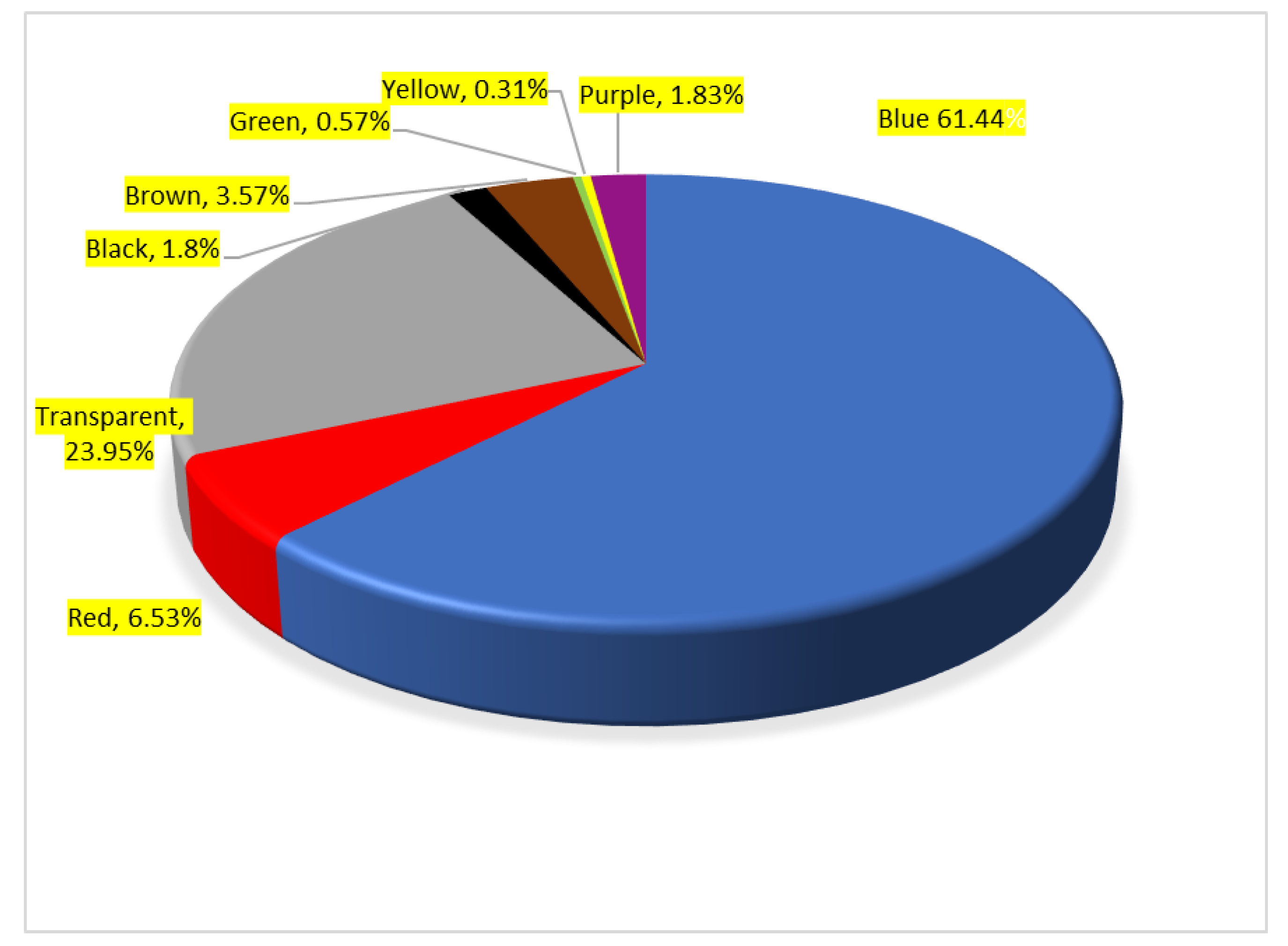

| Color | Blue | 344 | 202 |

| Transparent | 45 | 56 | |

| Red | 34 | 17 | |

| Black | 10 | 4 | |

| Brown | 24 | 9 | |

| Green | 1 | 2 | |

| Yellow | 0 | 1 | |

| Purple | 20 | 4 | |

| Plastics’ totals | 478 | 295 | |

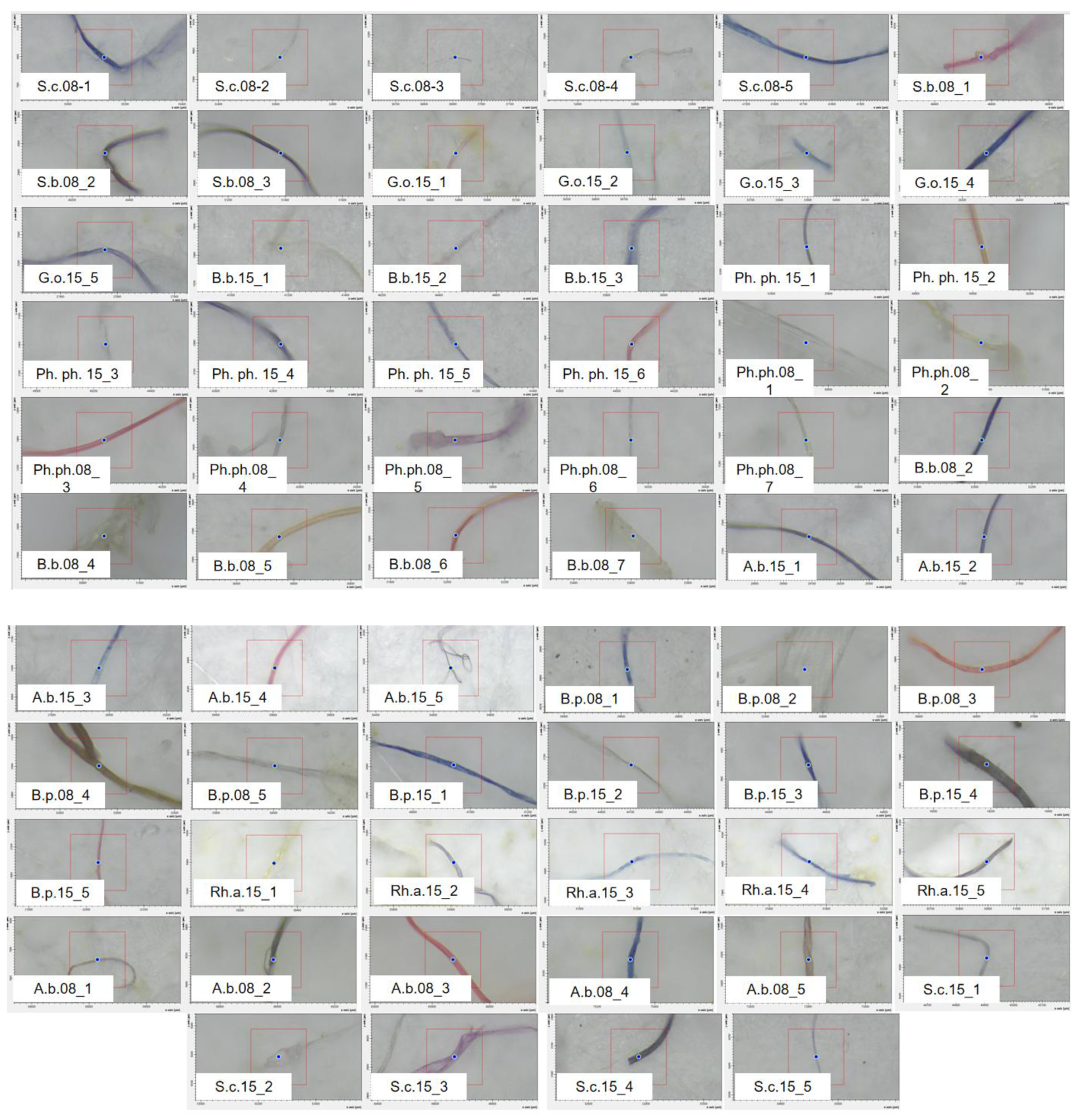

| Species | Barbus petenyi (2008) | Barbus petenyi (2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic characteristics | No. of items | No. of items | |

| Shape | Fibers | 373 | 297 |

| Fragments | 1 | 0 | |

| Size | 0-0.9 mm | 142 | 69 |

| 1-1.9 mm | 113 | 115 | |

| 2-2.9 mm | 64 | 71 | |

| 3-4.9 mm | 38 | 32 | |

| 5-10 mm | 15 | 10 | |

| >10 mm | 2 | 0 | |

| Average size | 1.84 mm | 1.87 mm | |

| Color | Blue | 181 | 172 |

| Transparent | 113 | 93 | |

| Red | 28 | 18 | |

| Black | 3 | 10 | |

| Brown | 39 | 1 | |

| Green | 1 | 0 | |

| Yellow | 1 | 0 | |

| Purple | 7 | 3 | |

| Plastics’ totals | 374 | 297 | |

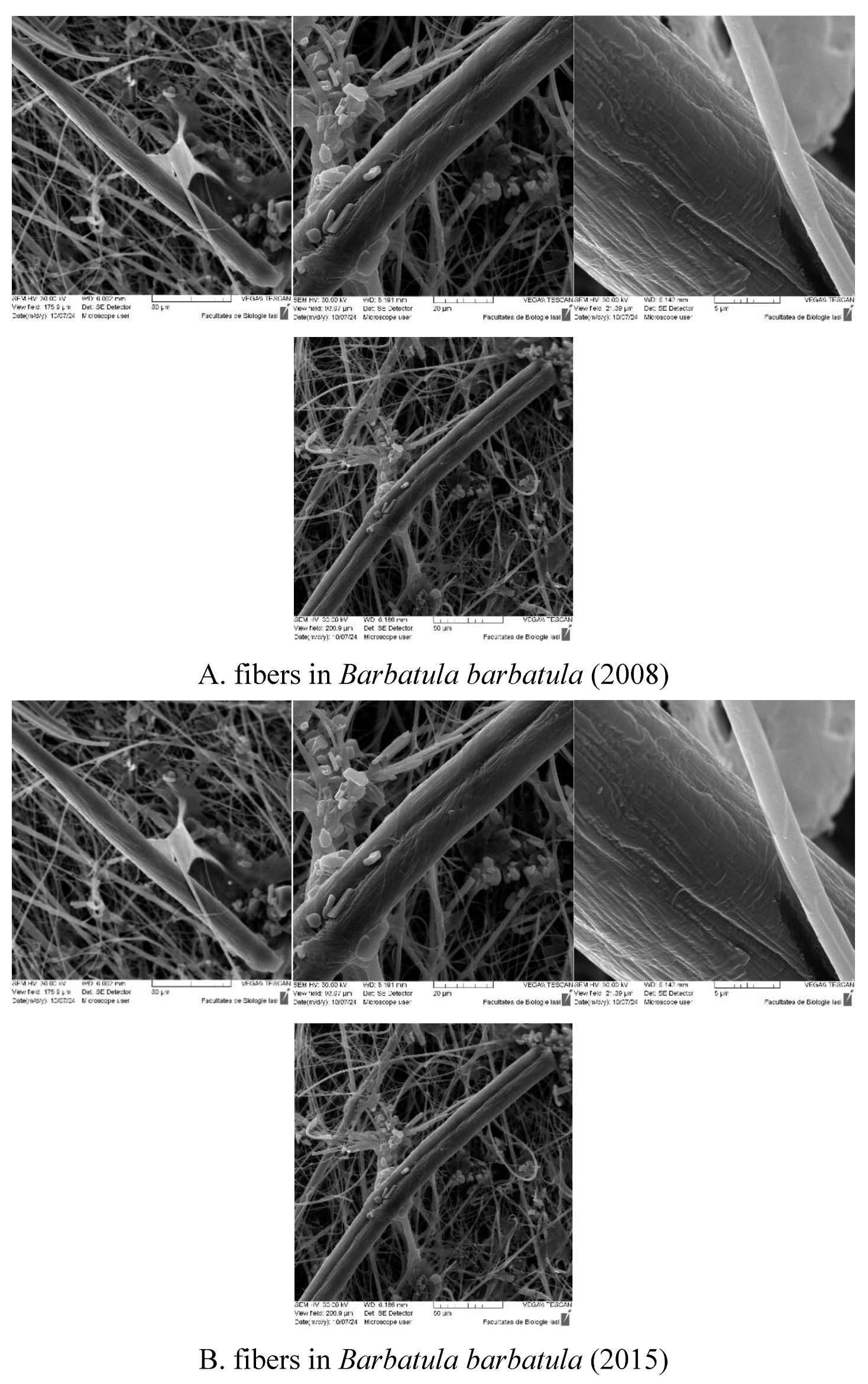

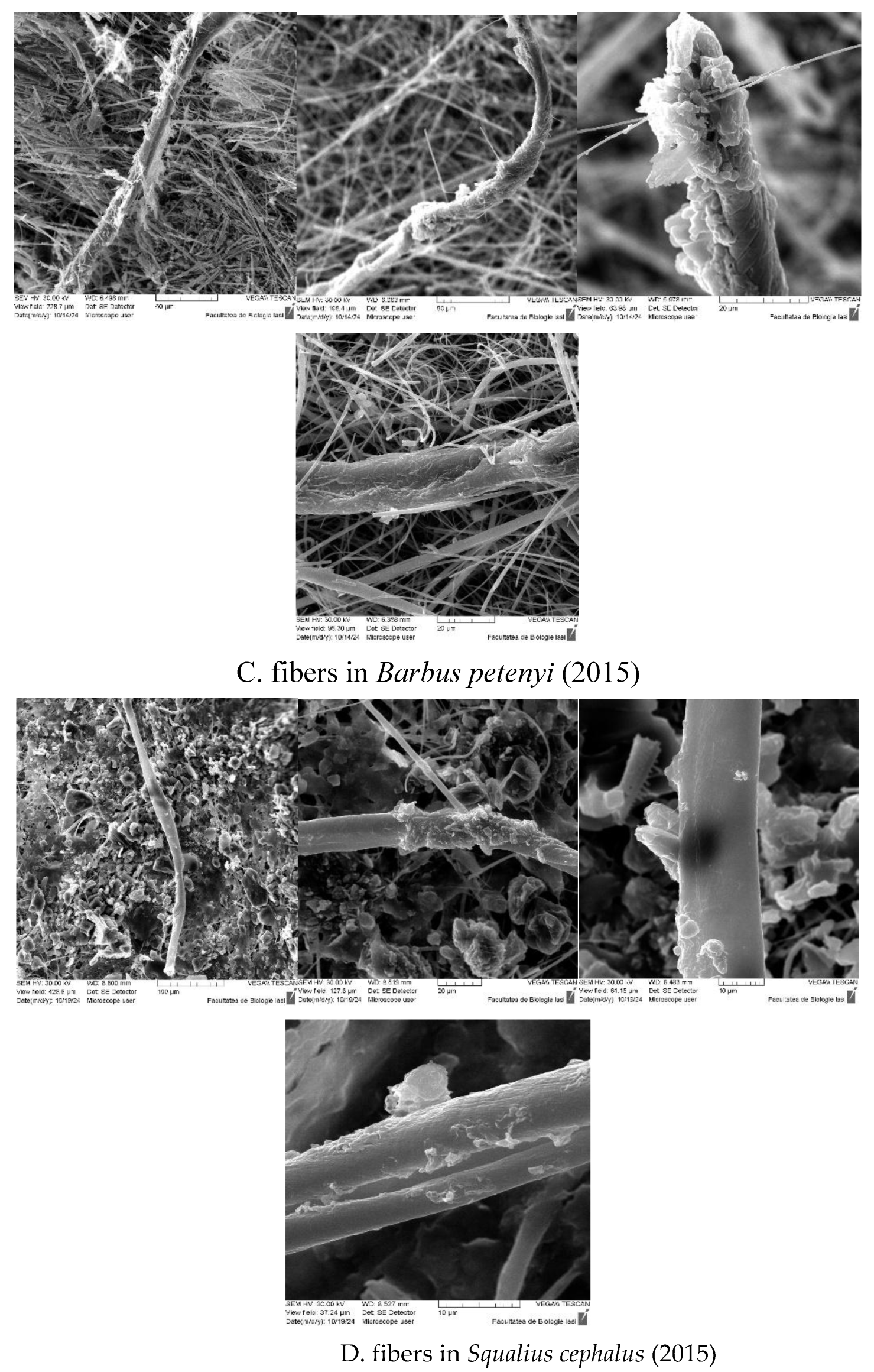

| Species | Barbatula barbatula (2008) |

Barbatula barbatula (2015) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic characteristics | No. of items | No. of items | |

| Shape | Fibers | 392 | 220 |

| Size | 0-0.9 mm | 158 | 64 |

| 1-1.9 mm | 149 | 91 | |

| 2-2.9 mm | 46 | 36 | |

| 3-4.9 | 32 | 24 | |

| 5-10 mm | 7 | 5 | |

| Average size | 1.46 mm | 1.69 mm | |

| Color | Blue | 243 | 152 |

| Transparent | 118 | 31 | |

| Red | 13 | 13 | |

| Black | 3 | 8 | |

| Brown | 3 | 2 | |

| Green | 2 | 1 | |

| Yellow | 2 | 5 | |

| Purple | 8 | 8 | |

| Plastics’ totals | 392 | 220 | |

| Species | Phoxinus phoxinus (2008) | Phoxinus phoxinus (2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic characteristics | No. of items | No. of items | |

| Shape | Fibers | 407 | 238 |

| Fragments | 2 | 0 | |

| Size | 0-0.9 mm | 109 | 78 |

| 1-1.9 mm | 153 | 102 | |

| 2-2.9 mm | 89 | 33 | |

| 3-4.9 | 45 | 18 | |

| 5-10 mm | 11 | 7 | |

| >10 mm | 2 | 0 | |

| Average size | 1.94 mm | 1.67 mm | |

| Color | Blue | 213 | 179 |

| Transparent | 144 | 35 | |

| Red | 24 | 19 | |

| Black | 2 | 2 | |

| Brown | 15 | 2 | |

| Green | 2 | 0 | |

| Yellow | 1 | 0 | |

| Purple | 8 | 1 | |

| Plastics’ totals | 409 | 238 | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPs | microplastics |

| PA PP PS |

polyamide polypropylene polyethylene polystyrene |

| PET | polyethylene terephthalate |

| PES PVC PE PMMA |

polystyrene polyvinyl chloride polyethylene polymethyl methacrylate |

References

- Burlacu, L.; Deak, G.; Boboc, M.; Raischi, M.; Holban, E.; Sadîca, I.; Jawdhari, A. Understanding the Ecosystem Carrying Capacity for Romanichthys valsanicola, a Critically Endangered Freshwater Fish Endemic to Romania, with Considerations upon Trophic Offer and Behavioral Density. Diversity 2023, 15, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăduţu, A.-M. The Impact of The Anthropic Factors on Disrupting and Destabilizing the Ecological Balance of The Vâlsan River. Current Trends in Natural Sciences 2013, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ge, J.; Yu, X. Bioavailability and toxicity of microplastics to fish species: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 189, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strungaru, S.A.; Jijie, R.; Nicoara, M.; Plavan, G.; Faggio, C. Micro- (nano) plastics in freshwater ecosystems: Abundance, toxicological impact and quantification methodology. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 110, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, F.; Gasperi, J.; Gabrielsen, G.W.; Tassin, B. Plastic Particle Ingestion by Wild Freshwater Fish: A Critical Review. Environmental Science and Technology 2019, 53, 12974–12988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wu, T.; Wang, X.; Song, Z.; Zong, C.; Wei, N.; Li, D. Consistent Transport of Terrestrial Microplastics to the Ocean through Atmosphere. Environmental Science and Technology 2019, 53, 10612–10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, D.; Sobral, P.; Ferreira, J.L.; Pereira, T. Ingestion of microplastics by commercial fish off the Portuguese coast. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 101, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimba, C.G.; Faggio, C. Microplastics in the marine environment: Current trends in environmental pollution and mechanisms of toxicological profile. In Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2019, 68, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahul Hamid, F.; Bhatti, M.S.; Anuar, N.; Anuar, N.; Mohan, P.; Periathamby, A. Worldwide distribution and abundance of microplastic: How dire is the situation? Waste Management and Research 2018, 36, 873–897, SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, E.; Sureda, A.; Tejada, S.; Faggio, C. Microplastic in marine organism: Environmental and toxicological effects. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2018, 64, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutrition 2018, 21, 5–17, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO calls for more research into microplastics and a crackdown on plastic pollution. WHO Newsroom, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- GESAMP. Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment: a global assessment. (Kershaw, P.J., ed.). (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection). Rep. Stud. GESAMP No. 90, 2015.

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, J.; Gao, J. Efficient removal of polyamide particles from wastewater by electrocoagulation. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 51, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, C.A.; Robison, B.H.; Gagne, T.O.; Erwin, B.; Firl, E.; Halden, R.U.; Hamilton, J.A.; Katija, K.; Lisin, S.E.; Rolsky, C.; Van Houtan, K.S. The vertical distribution and biological transport of marine microplastics across the epipelagic and mesopelagic water column. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler-Kozma, D.N.; Kruckenfellner, L.; Heitkamp, A.; Ebke, K.P.; Gabel, F. Uptake and Transfer of Polyamide Microplastics in a Freshwater Mesocosm Study. Water 2022, 14, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijagic, A.; Kotlyar, O.; Larsson, M.; Salihovic, S.; Hedbrant, A.; Eriksson, U.; Karlsson, P.; Persson, A.; Scherbak, N.; Farnlund, K.; Engwall, M.; Sarndahl, E. Immunotoxic, genotoxic, and endocrine disrupting impacts of polyamide microplastic particles and chemicals. Environment International 2024, 183, 108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Lawton, L.A.; Petrie, B. Polyamide microplastics in wastewater as vectors of cationic pharmaceutical drugs. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, C. Recycling and Degradation of Polyamides. Molecules 2024, 29, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iușan, C.; Câmpan, K.T. Guide to fish (ichthyofauna) in the Rodna Mountains National Park, Exclus Publishing, Bucuresti, Romania, 2013, 150 p. (in Romanian).

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Research 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, R.R.; Bornatowski, H.; Vitule, J.R.S. Feeding ecology of fishes: An overview of worldwide publications. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 2012, 22, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Hoh, E.; Hentschel, B.T.; Kaye, S. Long-term field measurement of sorption of organic contaminants to five types of plastic pellets: Implications for plastic marine debris. Environmental Science and Technology 2013, 47, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koongolla, J.B.; Lin, L.; Pan, Y.F.; Yang, C.P.; Sun, D.R.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.R.; Maharana, D.; Huang, J.S.; Li, H.X. Occurrence of microplastics in gastrointestinal tracts and gills of fish from Beibu Gulf, South China Sea. Environmental Pollution 2020, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, S.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Gao, P. Microplastics in freshwater and wild fishes from Lijiang River in Guangxi, Southwest China. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 755, 142428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlas of the Romanian Water Cadastre, Ed. Ministerul Mediului, Aquaproiect S.A., Bucuresti, Romania, 1992, 694 p. (in Romanian).

- Nicoara, M.; Ureche, D.; Plavan, G.; Erhan, M. Comparative analyses of the food spectra of the fish populations living in the rivers Oituz and Casin. Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii „AL. I. CUZA” Iaşi 2006, Tom LII (Biologie animală), 87–93.

- Rău, M.A.; Plavan, G.; Strungaru, Ș.A.; Nicoara, M.; Moglan, I.; Ureche, D. Feeding Ecology of Two Sympatric Fish Species in a River Ecosystem. Analele Științifice ale Universității „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iași 2015, Tom LXI, 11–18.

- Ureche, D.; Nicoara, M.; Ureche, C. A comparative analysis of food components in fish populations from the Buzau River basin (Romania). Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies 2008, XXXVII(I), 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ureche, D.; Ureche, C.; Nicoara, M.; Plavan, G. The role of macroinvertebrates in diets of fish in River Dambovita, Romania. SIL Proceedings 2010, 30, 30–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureche, D.; Ureche, C. Study of Fish Communities in the Siret River, and Some Tributaries (Bacau – Racaciuni Section, 2012-2016). International symposium ”Functional ecology of animals” 2021, 479-481. [CrossRef]

- Saad, D.; Chauke, P.; Cukrowska, E.; Richards, H.; Nikiema, J.; Chimuka, L.; Tutu, H. First biomonitoring of microplastic pollution in the Vaal river using Carp fish (Cyprinus carpio) “as a bio-indicator”. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Pan, Z.; Sun, D.; Zhou, A.; Xie, S.; Wang, J.; Zou, J. Microplastics in wild freshwater fish of different feeding habits from Beijiang and Pearl River Delta regions, south China. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galafassi, S.; Sighicelli, M.; Pusceddu, A.; Bettinetti, R.; Cau, A.; Temperini, M.E.; Gillibert, R.; Ortolani, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Zaupa, S.; Volta, P. Microplastic pollution in perch (Perca fluviatilis, Linnaeus 1758) from Italian south-alpine lakes. Environmental Pollution 2021, 288, 117782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.M.; Uddin, A.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Rahman, M.; Islam, M.S.; Kibria, G. Microplastics in an anadromous national fish, Hilsa shad Tenualosa ilisha from the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 174, 113236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkan, T.; Gedik, K.; Mutlu, T. Protracted dynamicity of microplastics in the coastal sediment of the Southeast Black Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 188, 114722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretsch, E.; Buhlmann, P.; Badertscher, M. Structure Determination of Organic Compounds. Tables of Spectral Data, 4th ed.; Revised and Enlarged Edition, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009.

- Elhady, S.; Bassyouni, M.; Mansour, R.A.; Elzahar, M.H.; Abdel-Hamid, S.; Elhenawy, Y.; Saleh, M.Y. Oily Wastewater Treatment Using Polyamide Thin Film Composite Membrane Technology. Membranes 2020, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshoulles, Q.; Le Gall, M.; Dreanno, C.; Arhant, M.; Priour, D.; Le Gac, P.-Y. Modelling pure polyamide 6 hydrolysis: Influence of water content in the amorphous phase. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2021, 183, 109435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; McMahan, C.D.; McNeish, R.E.; Munno, K.; Rochman, C.M.; Hoellein, T.J. A fish tale: a century of museum specimens reveal increasing microplastic concentrations in freshwater fish. Ecological Applications 2021, 31, e2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeish, R.E.; Kim, L.H.; Barrett, H.A.; Mason, S.A.; Kelly, J.J.; Hoellein, T.J. Microplastic in riverine fish is connected to species traits. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouin, T. Toward an Improved Understanding of the Ingestion and Trophic Transfer of Microplastic Particles: Critical Review and Implications for Future Research. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2020, 39, 1119–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoara, M.; Ureche, D.; Ureche, C.; Nicoara, A. Macroinvertebrate presence in food of fish population from River Buzau (Romania). Internationale Vereinigung Für Theoretische Und Angewandte Limnologie: Verhandlungen 2006, 29, 22256–22258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoară, M.; Erhan, M.; Plavan, G.; Cojocaru, I.; Davideanu, A.; Nicoară, A. The Ecological Complex Role of the Macroinvertebrate Fauna From the River Ciric, Analele Științifice ale Universității „Al. I. Cuzaˮ Iași, s. Biologie Animală 2009, Tom LV, 125–132.

- Dumitrașcu, O.C.; Mitrea, I. Data upon the ichthyofauna of three reservoirs from the Jiu River, Romania. South Western Journal of Horticulture, Biology and Environment 2012, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Truță, A.-M.; Dumitru, R. Research on Argeș river fish fauna in Budeasa-Golești area. Current Trends in Natural Sciences 2015, 4, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bănăduc, D. Fish associations ‒ habitats quality relation in the Târnave rivers ecological assessment. Transylvanian Review of Systematical and Ecological Research 2005, 2, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bănăduc, D. Species and subspecies of the genus Gobio (Gobioninae, Cyprinidae, Pisces) in Romania - Analysis of the state of knowledge. Brukenthal Acta Musei 2006, I(3), 125–144. (in Romanian). [Google Scholar]

- Bănăduc, D.; Oprean, L.; Bogdan, A.; Curtean-Bănăduc, A. The analyse of the trophic resources utilisation by the congeneric species Barbus barbus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Barbus meridionalis Risso, 1827 in Tarnava River basin. Transylvanian Review of Systematical and Ecological Research 2011, 12, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Curtean-Bănăduc, A.; Bănăduc, D. Cibin River fish communities structural and functional aspects. Studii Şi Cercetări Ştiinţifice-Seria Biologie 2004, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, G.O.; Dudu, A.; Bănăduc, D.; Curtean-Bănăduc, A.; Burcea, A.; Ureche, D.; Nechifor, R.; Georgescu, S.E.; Costache, M. Genetic analysis of populations of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) from the Romanian Carpathians, Aquatic Living Resources 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rau, M.A.; Plavan, G.; Strungaru, S.A.; Nicoara, M.; Rodriguez-Lozano, P.; Mihu-Pintilie, A.; Ureche, D.; Klimaszyk, P. The impact of amur sleeper (Perccottus glenii Dybowsky, 1877) on the riverine ecosystem: Food selectivity of amur sleeper in a recently colonized river. Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies 2017, 46, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyeste, K.; Dobrocsi, P.; Czeglédi, I.; Czédli, H.; Harangi, S.; Baranyai, E.; Simon, E.; Nagy, S.A.; Antal, L. Age and diet-specific trace element accumulation patterns in different tissues of chub (Squalius cephalus): Juveniles are useful bioindicators of recent pollution. Ecological Indicators 2019, 101, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulat, D. Ichthyofauna of the Republic of Moldova: threats, trends, and rehabilitation recommendations. Acad. de Științe a Moldovei, Inst. de Zoologie al Acad. de Științe a Moldovei, Chișinău, Republica Moldova, 2017, 344 p. (in Romanian).

- Sasi, H.; Ozay, G.G. Age, Growth, Length-Weight Relationship and Reproduction of Chub, Squalius cephalus (L., 1758) in Upper Akcay River, Turkey. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, F.; Gasperi, J.; Gilbert, B.; Eppe, G.; Azimi, S.; Rocher, V.; Tassin, B. Anthropogenic particles in the stomach contents and liver of the freshwater fish Squalius cephalus. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 643, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, B.; Erk’akan, F. Diet composition of chub, Squalius cephalus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae), in Lake Tödürge, Sivas, Turkey. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2011, 27, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, R.; Rusu, A.; Plavan, G.-I.; Ureche, D.; Cojocaru, I.; Nicoara, M. Feeding ecology of Squalius cephalus population from river Oituz, Scientific Study & Research. Biology 2024, 33, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Maxim, R.; Ureche, D.; Plavan, G.-I.; Cojocaru, I.; Nicoară, M. The trophic spectra of Squalius cephalus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Rhodeus amarus (Bloch, 1782) fish species from Dâmbovnic River (Neajlov/Danube Basin). Transylvanian Review of Systematical and Ecological Research 27.1 The Wetlands Diversity 2025, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Piria, M.; Treer, T.; Aničić, I.; Safner, R.; Odak, T. The natural diet of five cyprinid fish species. Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus 2005, 70, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Huusko, A.; Sutela, T. Minnow predation on vendace larvae: intersection of alternative prey phenologies and size-based vulnerability. Journal of Fish Biology 1997, 50, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscoz, J.; Leunda, P.M.; Miranda, R.; Escala, M.C. Summer feeding relationships of the co-occurring Phoxinus phoxinus and Gobio lozanoi (Cyprinidae) in an Iberian river. Folia Zoologica, 2006, 55, 418–432. [Google Scholar]

- Scharnweber, K. Morphological and trophic divergence of lake and stream minnows (Phoxinus phoxinus). Ecology and Evolution 2020, 10, 8358–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treer, T.; Piria, M.; Aničić, I.; Safner, R.; Tomljanović, T. Diet and growth of spirlin, Alburnoides bipunctatus in the barbel zone of the Sava River. Folia Zoologica 2006, 55, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bănărescu, P.M.; Bănăduc, D. Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) Fish species (Osteichthyes) on the Romanian territory. Acta Ichtiologica Romanica 2007, II, 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vornicu, B.; Ion, I. Nutrition of Some Species of Fish in the Middle Basin of Moldova River. Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii „Al.I.Cuza” Iaşi, s. Biologie animală 2004, Tom L, 223-227.

- Kasamesiri, P.; Thaimuangpho, W. Microplastics ingestion by freshwater fish in the Chi River, Thailand. International Journal of GEOMATE 2020, 18, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, R.S.; Maiztegui, T.; Colautti, D.C.; Paracampo, A.H.; Gómez, N. Microplastics in gut contents of coastal freshwater fish from Río de la Plata estuary. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2017, 122, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, N.; Reis-Santos, P.; Gillanders, B.M. Microplastic in fish – A global synthesis. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 2021, 31, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munno, K.; Helm, P.A.; Rochman, C.; George, T.; Jackson, D.A. Microplastic contamination in Great Lakes fish. Conservation Biology 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, K.; Su, L.; Li, J.; Yang, D.; Tong, C.; Mu, J.; Shi, H. Microplastics and mesoplastics in fish from coastal and fresh waters of China. Environmental Pollution 2017, 221, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Xue, Y.; Yu Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Peng, M.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q. Microplastic pollution characteristic in surface water and freshwater fish of Gehu Lake, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 67203–67213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, J.; Carretero, O.; Filgueiras, A.V.; Viñas, L. Synthetic microfibers in the marine environment: A review on their occurrence in seawater and sediments. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 127, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: a review. Environmental Pollution 2013, 178, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, A.A.; Jürgens, M.D.; Lahive, E.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Vijver, M.G. The influence of exposure and physiology on microplastic ingestion by the freshwater fish Rutilus rutilus (roach) in the River Thames, UK. Environmental Pollution 2018, 236, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuśmierek, N.; Popiołek, M. Microplastics in freshwater fish from Central European lowland river (Widawa R., SW Poland). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 11438–11442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.D.; Murphy, S.; Lally, H.T.; O’Connor, I.; Nash, R.; O’Sullivan, J.; Bruen, M.; Heerey, L.; Koelmans, A.A.; Cullagh, A.; Cullagh, D.; Mahon, A.M. Microplastics in brown trout (Salmo trutta Linnaeus, 1758) from an Irish riverine system. Environmental Pollution 2020, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.R.; Shashoua, Y.; Crawford, A.; Drury, A.; Sheppard, K.; Stewart, K.; Sculthorp, T. ‘The Plastic Nile’: First Evidence of Microplastic Contamination in Fish from the Nile River (Cairo, Egypt). Toxics 2020, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chao, M.; He, X.; Lan, X.; Tian, C.; Feng, C.; Shen, Z. Microplastic bioaccumulation in estuary-caught fishery resource. Environmental Pollution 2022, 306, 119392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Mandal, A.; Rajaram, R.; Darbha, G.K. Ecological risk assessment and ingestion of microplastics in edible finfish and shellfish species collected from tropical mangrove forest, Southeastern India. Chemosphere 2025, 377, 144308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoran, A.R.; Clark, P.F.; Morritt, D. Presence of microplastic in the digestive tracts of European flounder, Platichthys flesus, and European smelt, Osmerus eperlanus, from the River Thames. Environmental Pollution 2017, 220, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uurasjärvi, E.; Sainio, E.; Setälä, O.; Lehtiniemi, M.; Koistinen, A. Validation of an imaging FTIR spectroscopic method for analyzing microplastics ingestion by Finnish lake fish (Perca fluviatilis and Coregonus albula). Environmental Pollution 2021, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, S.; Walter, T.; Ittner, L.D.; Friedrich, C.; Brinker, A. A systematic study of the microplastic burden in freshwater fishes of south-western Germany - Are we searching at the right scale? Science of The Total Environment 2019, 689, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonte, E.; Ferreira, P.; Guilhermino, L. Temperature rise and microplastics interact with the toxicity of the antibiotic cefalexin to juveniles of the common goby (Pomatoschistus microps): Post-exposure predatory behaviour, acetylcholinesterase activity and lipid peroxidation. Aquatic Toxicology 2016, 180, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nel, H.A.; Froneman, P.W. A quantitative analysis of microplastic pollution along the south-eastern coastline of South Africa. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 101, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa Araújo, A.P.; Malafaia, G. Microplastic ingestion induces behavioral disorders in mice: A preliminary study on the trophic transfer effects via tadpoles and fish. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasamesiri, P.; Meksumpun, C.; Meksumpun, S.; Ruengsorn, C. Assessment on Microplastics Contamination in Freshwater Fish: A Case Study of the Ubolratana Reservoir, Thailand. International Journal of GEOMATE 2021, 20, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Cavalcanti, J.S.; Silva, J.D.B.; de França, E.J.; de Araújo, M.C.B.; Gusmão, F. Microplastics ingestion by a common tropical freshwater fishing resource. Environmental Pollution 2017, 221, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, F.; Jannat, S.; Tareq, S.M. Abundance, characteristics and variation of microplastics in different freshwater fish species from Bangladesh. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.H.; Williamson, P.R.; Hall, B.D. Microplastics in the gastrointestinal tracts of fish and the water from an urban prairie creek. Facets 2017, 2, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.A.; Bratton, S.P. Urbanization is a major influence on microplastic ingestion by sunfish in the Brazos River Basin, Central Texas, USA. Environmental Pollution 2016, 210, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, A.O.; Ibor, O.R.; Khan, E.A.; Chukwuka, A.V.; Omogbemi, E.D.; Arukwe, A. Detection and occurrence of microplastics in the stomach of commercial fish species from a municipal water supply lake in southwestern Nigeria. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 31035–31045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarijan, S.; Azman, S.; Said, M.I.M.; Lee, M.H. Ingestion of microplastics by commercial fish in Skudai River, Malaysia. EnvironmentAsia 2019, 12, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xiong, X.; Hu, H.; Wu, C.; Bi, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Lam, P.K.S.; Liu, J. Occurrence and Characteristics of Microplastic Pollution in Xiangxi Bay of Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 51, 3794–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, N.; Khoshnamvand, N.; Nasseri, S. The quantity and quality assessment of microplastics in the freshwater fishes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2021, 47, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, S.; Brinker, A. Rapid and Efficient Method for the Detection of Microplastic in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Fishes. Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 51, 4522–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, J.; Xie, S.; Tang, H.; Zhang, C.; Xu, G.; Zou, J.; Zhou, A. Characterization and spatial distribution of microplastics in two wild captured economic freshwater fish from north and west rivers of Guangdong province. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 207, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Mena, G.; Sánchez-Guerrero-Hernández, M.J.; Yeste, M.P.; Ramos, F.; González-Ortegón, E. Microplastics in the stomach content of the commercial fish species Scomber colias in the Gulf of Cadiz, SW Europe. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2024, 200, 0–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.M.; Vethaak, A.D.; Almroth, B.C.; Ariese, F.; van Velzen, M.; Hassellöv, M.; Leslie, H.A. Screening for microplastics in sediment, water, marine invertebrates and fish: Method development and microplastic accumulation. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2017, 122, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.G.; Suárez, D.C.; Li, J.; Rotchell, J.M. A comparison of microplastic contamination in freshwater fish from natural and farmed sources. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 14488–14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, F.; Gilbert, B.; Eppe, G.; Parmentier, E.; Das, K. Detection of Anthropogenic Particles in Fish Stomachs: An Isolation Method Adapted to Identification by Raman Spectroscopy. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2015, 69, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradit, S.; Noppradit, P.; Goh, B.P.; Sornplang, K.; Ong, M.C.; Towatana, P. Occurrence of microplastics and trace metals in fish and shrimp from Songkhla lake, Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2021, 19, 1085–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, T.; Janardhanam, M.; Sivakumar, P.; Sivakumar, R.; Rajamanickam, K.; Raman, T.; Thangavelu, M.; Muthusamy, G.; Singaram, G. Microplastic contamination in commercial fish species in southern coastal region of India. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galafassi, S.; Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F.; Volta, P. Do freshwater fish eat microplastics? A review with a focus on effects on fish health and predictive traits of mps ingestion. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Busquets, R.; Campos, L.C. Assessment of microplastics in freshwater systems: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 707, 135578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torné, M.; Abad, E.; Almeida, D.; Llorca, M.; Farré, M. Assessment of Micro- and Nanoplastic Composition (Polymers and Additives) in the Gastrointestinal Tracts of Ebro River Fishes. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Pu, S.; Liu, S.; Bai, Y.; Mandal, S.; Xing, B. Microplastics in aquatic environments: Toxicity to trigger ecological consequences. Environmental Pollution 2020, 261, 114089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species |

Alburnoides bipunctatus (2008) |

Alburnoides bipunctatus (2015) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic characteristics | No. of items | No. of items | |

| Shape | Fibers | 68 | 91 |

| Films | 0 | 17 | |

| Size | 0-0.9 mm | 13 | 27 |

| 1-1.9 mm | 26 | 33 | |

| 2-2.9 mm | 15 | 27 | |

| 3-4.9 | 14 | 18 | |

| 5-10 mm | 0 | 3 | |

| Average size | 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm | |

| Color | Blue | 39 | 52 |

| Transparent | 7 | 40 | |

| Red | 6 | 14 | |

| Black | 8 | 0 | |

| Brown | 5 | 2 | |

| Green | 3 | 0 | |

| Plastics’ totals | 68 | 108 | |

| Species |

Sabanejewia balcanica (2008) |

Rhodeus amarus (2015) |

Gobio obtusirostris (2015) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic characteristics | No. of items | No. of items | No. of items | |

| Shape | Fibers | 143 | 53 | 124 |

| Films | 0 | 5 | 8 | |

| Fragments | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Size | 0-0.9 mm | 50 | 19 | 34 |

| 1-1.9 mm | 55 | 19 | 47 | |

| 2-2.9 mm | 22 | 7 | 26 | |

| 3-4.9 | 17 | 12 | 17 | |

| 5-10 mm | 1 | 0 | 8 | |

| >10 mm | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Average size | 1.5 mm | 1.9 mm | 2.0 mm | |

| Color | Blue | 85 | 32 | 81 |

| Transparent | 34 | 19 | 35 | |

| Red | 11 | 4 | 9 | |

| Black | 7 | 0 | 1 | |

| Brown | 7 | 2 | 4 | |

| Green | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Plastics’ totals | 145 | 58 | 132 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).