1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a degenerative joint disease that affects domestic dog breeds. Its clinical signs include joint pain, swelling, stiffness, and reduced mobility. When articular cartilage is damaged or ages, it loses its ability to self-repair due to a lack of blood supply. Consequently, early treatment options primarily provide symptomatic relief rather than a cure [

1].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have garnered attention for their ability to self-renew and differentiate into specialized cell types, making them a promising avenue for cartilage repair and joint regeneration. Their multipotent nature allows them to potentially address the underlying tissue degeneration associated with KOA, offering hope for more effective, disease-modifying therapies [

2,

3].

MSCs are undifferentiated cells that can undergo multipotent differentiation and self-renewal. They reside in specific microenvironments and play a crucial role in maintaining tissue homeostasis and promoting healing. MSCs can be sourced from bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental pulp, umbilical cord, placenta, and amniotic fluid. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) have significant clinical applications. BMSCs are safe and capable of evading host immune rejection responses. However, they represent only a small fraction of the total mononuclear cells in bone marrow, and their numbers decline with age [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Moreover, as people age, the overall cellularity of bone marrow decreases—studies have shown a reduction of about 3% per decade. This gradual decline is partly due to the conversion of hematopoietic and stromal tissue into adipose tissue, which disrupts the microenvironment necessary for supporting mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). As a result, the already limited MSC pool becomes even smaller in older individuals, potentially diminishing the tissue’s capacity for repair and regeneration [

8,

9].

In this study, we hypothesize that cells isolated from the bone marrow of immature canines exhibit characteristics similar to those of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and represent a potential cellular source for treating articular cartilage injuries in canine knee joints. We intend to isolate these cells from the immature bone marrow of a canine and evaluate their biological properties using colony-forming unit (CFU) assays on plastic culture dishes, as well as by assessing cellular morphology, stability, proliferation capacity, surface marker expression, and their potential to differentiate into various cell types.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

In this study, the canine bone marrow donors were exclusively puppies under one month old. Biochemical assays and complete blood count (CBC) tests were conducted to verify the puppies’ health status. The Ethics Committee on Animal Experiments at Can Tho University approved the experimental protocol (CTU-AEC24014).

2.2. Methods for the Collection and Isolation of Cells from the Bone Marrow of the Immature Canine

The donor canine was anesthetized with Zoletil 50 at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg body weight, administered intramuscularly, followed by the collection of bone marrow fluid [

10]. The collected bone marrow fluid, which contained a 1X PBS solution, was filtered through a 100 µm cell strainer. The filtered cells were washed with 10 mL of 1X PBS solution and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, the cell pellet that accumulated at the bottom of the tube was collected. The cells were cultured in αMEM basal culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin) [

11]. The obtained cells were incubated under constant conditions at 37 °C with 5% CO

2.

2.3. Assessment of Colony-Forming Unit Capability of Cells Isolated from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

The obtained bone marrow cells were cultured in 6-well plates at a density of 1 million mononuclear cells (MNCs) per well. The cells were well suspended in basal medium and incubated under constant conditions at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After two weeks of culture, cell colonies were fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution and stained with Crystal Violet. The morphology of the cell colonies was observed and imaged.

2.4. Evaluation of the Morphology of Cells Collected from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

The morphology of cells obtained from immature canine bone marrow was observed under the magnification of an inverted microscope. Specifically, cell morphology was continuously documented from the first passage (P1) to the eighth passage (P8).

2.5. Evaluation of the Proliferation Capacity of Cells Obtained from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

The cell proliferation capacity was assessed through the doubling time assay. The obtained cells were transferred into 12-well plates and resuspended at a density of 5 × 10

4 cells per well. After the cells adhered and proliferated to cover approximately 70-80% of the dish surface, they were subcultured. Cells were collected after detachment using 1X trypsin. Cell numbers were confirmed using trypan blue staining and a hemocytometer. Proliferation continued similarly until P8 [

12].

2.6. Identification of Cells Harvested from Immature Canine Bone Marrow

Identifying cells derived from immature canine bone marrow was accomplished using stem cell surface markers, including CD34-PE, CD45-PE, CD90-APC, and CD105-FITC. Surface marker expression was analyzed by flow cytometry with the BD FACSCanto® system (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.7. Evaluation of Differentiation Capacity of MSCs Harvested from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

Adipogenic differentiation: The cells were cultured in an adipogenic differentiation medium. They were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 10

4 cells/cm

2 using the adipogenic differentiation medium from the MesenCult™ Adipogenic Differentiation Kit (Gibco™, USA). Control wells were maintained in α-MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics. The medium was changed every three days. After two weeks of MSC differentiation into adipocytes, the cells were stained with Oil Red O to observe the presence of lipid droplets within the adipocytes. Oil Red O (ORO) staining is a commonly used experimental technique for detecting lipid content in cells or tissues [

13].

Osteogenic differentiation: The obtained cells were cultured in an osteogenic differentiation medium. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 10

3 cells/cm

2 using the StemPro

® Osteogenesis Differentiation Kit (Gibco™, USA). Control wells were maintained in α-MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics. The medium was changed every three days. Osteogenic differentiation was conducted for 21 days. By the end of the second week, Ca2+ began to accumulate during the osteogenic differentiation process. Alizarin Red is a commonly used dye for detecting cells containing calcium deposits in the osteogenic differentiation culture medium of MSCs [

14].

Chondrogenic differentiation: The obtained cells were cultured into 3D aggregates in a chondrogenic differentiation medium. Three hundred thousand cells were centrifuged in a 15 mL tube at 2500 rpm for 5 minutes to form cell aggregates, which were then cultured in a 5% CO

2 incubator at 37 °C. After 24 hours of culture, the induction medium for chondrogenic differentiation, MesenCult ACF Chondrogenic Differentiation Kit (Gibco, USA), was applied. The medium was changed every three days. After three weeks of differentiation, samples were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. The embedded samples were then sliced into four µm-thick sections and stained with Safranin O to observe the presence of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). This method detected cartilage particles, mucins, and mast cells. Cartilage and mucins were stained orange to red, while nuclei appeared black. The background was stained green to signify the color contrast [

15].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 10 (version 10.4.2; GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used to generate graphical representations and conduct statistical analyses. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to compare multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. For comparisons involving only two groups, unpaired t tests were utilized. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

2.1. Sample Collection

The immature canine selected to provide bone marrow tissue exhibited biochemical properties and CBC results, as shown in

Table 1. The results indicated that the AST level of the bone marrow donor puppy was 16.04 U/L, within the normal range of 8.9–48.5 U/L, indicating normal liver function and overall health. The ALT level was 16.05 U/L, within the normal range of 8.2–57.3 U/L, indicating that the liver was unaffected by hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver tumors, or liver toxicity. The urea level was 8.2 mmol/L, within the normal range of 3.1–9.2 mmol/L, indicating normal kidney function. Additionally, the physiological indices of the puppy were as follows: red blood cell count was 4.85 × 10

6 /mm

3 (the normal range is 4.95–7.87 × 10

6 /mm

3); white blood cell count was 17.0 × 10

6 /mm

3 (the normal range is 5.0–14.1 × 10

6 /mm

3); platelet count was 189 × 10

6 /mm

3 (the normal range is 121–621 × 10

3 /mm

3); hemoglobin content was 21 g/dL (the normal range is 11.9–18.9 g/dL). The blood physiology results showed minor differences between the immature canine and standard indices, possibly due to the age differences of the individual subjects being studied.

2.2. Methods for the Collection and Isolation of Cells from the Bone Marrow of the Immature Canine

After seven days of primary culture, cells obtained from the bone marrow fluid of the immature canine began to adhere to the surface of the culture dish (

Figure 1A,C). The cells exhibited a fibroblast-like morphology, characterized by a spindle shape with long, extended processes.

2.3. Assessment of Colony-Forming Unit Capability of Cells Isolated from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

The results showed that MSCs formed CFUs after two weeks of culture in an essential medium on tissue culture plates. MSCs from canine bone marrow can form cell clusters. The colony-forming ability, as measured by the CFU-f frequency, yielded (5 ± 1) clusters per million mononuclear cells obtained from the bone marrow of the immature canine (

Figure 2).

2.4. Evaluation of the Morphology of Cells Collected from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

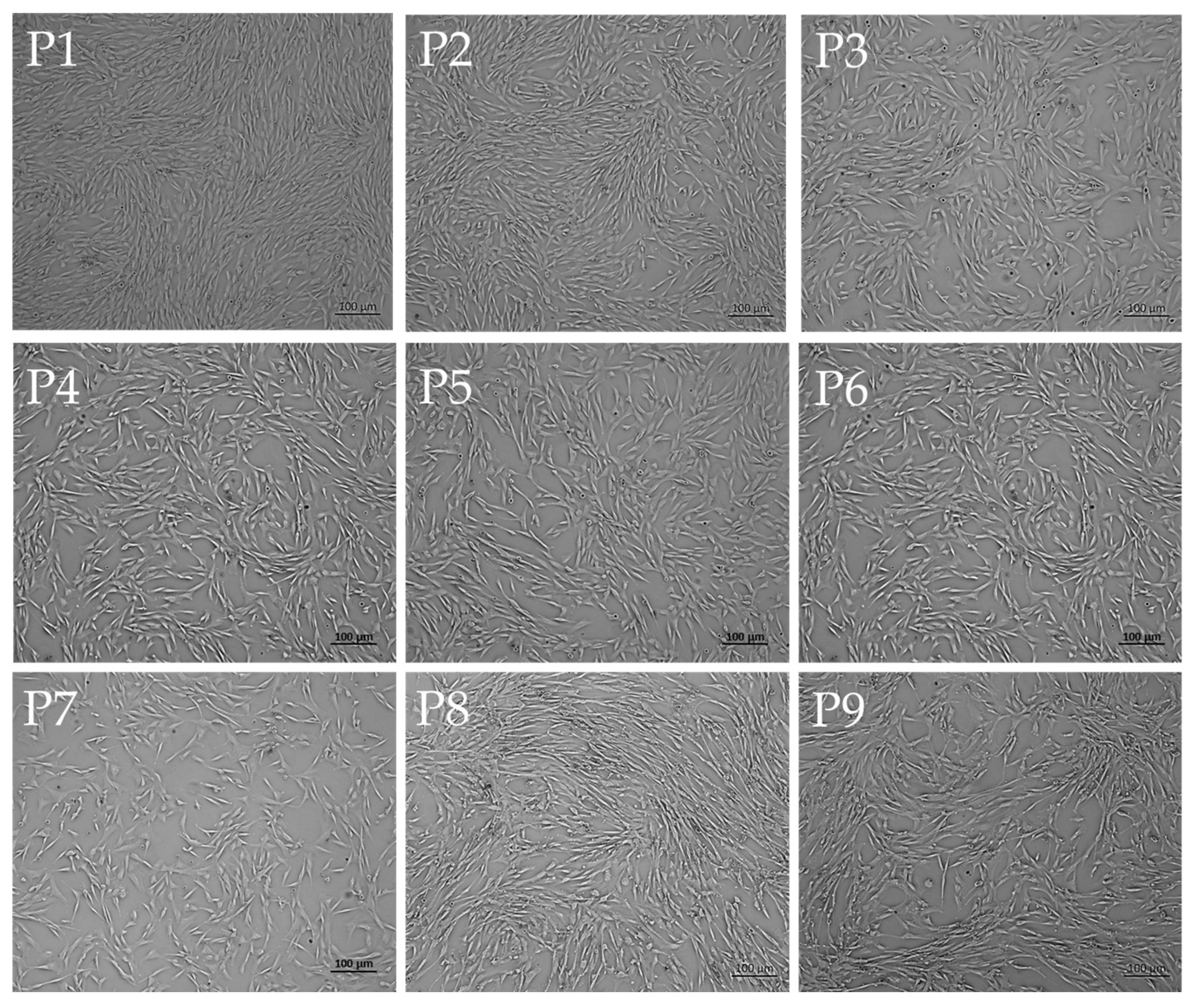

The obtained cell morphology was observed and documented under an inverted microscope using a 4X objective lens before each passage. Through these passages, the cells demonstrated stability in morphology, as shown in

Figure 3. These results demonstrate that MSCs harvested from an immature canine’s bone marrow can proliferate and maintain stability.

2.5. Evaluation of the Proliferation Capacity of Cells Obtained from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

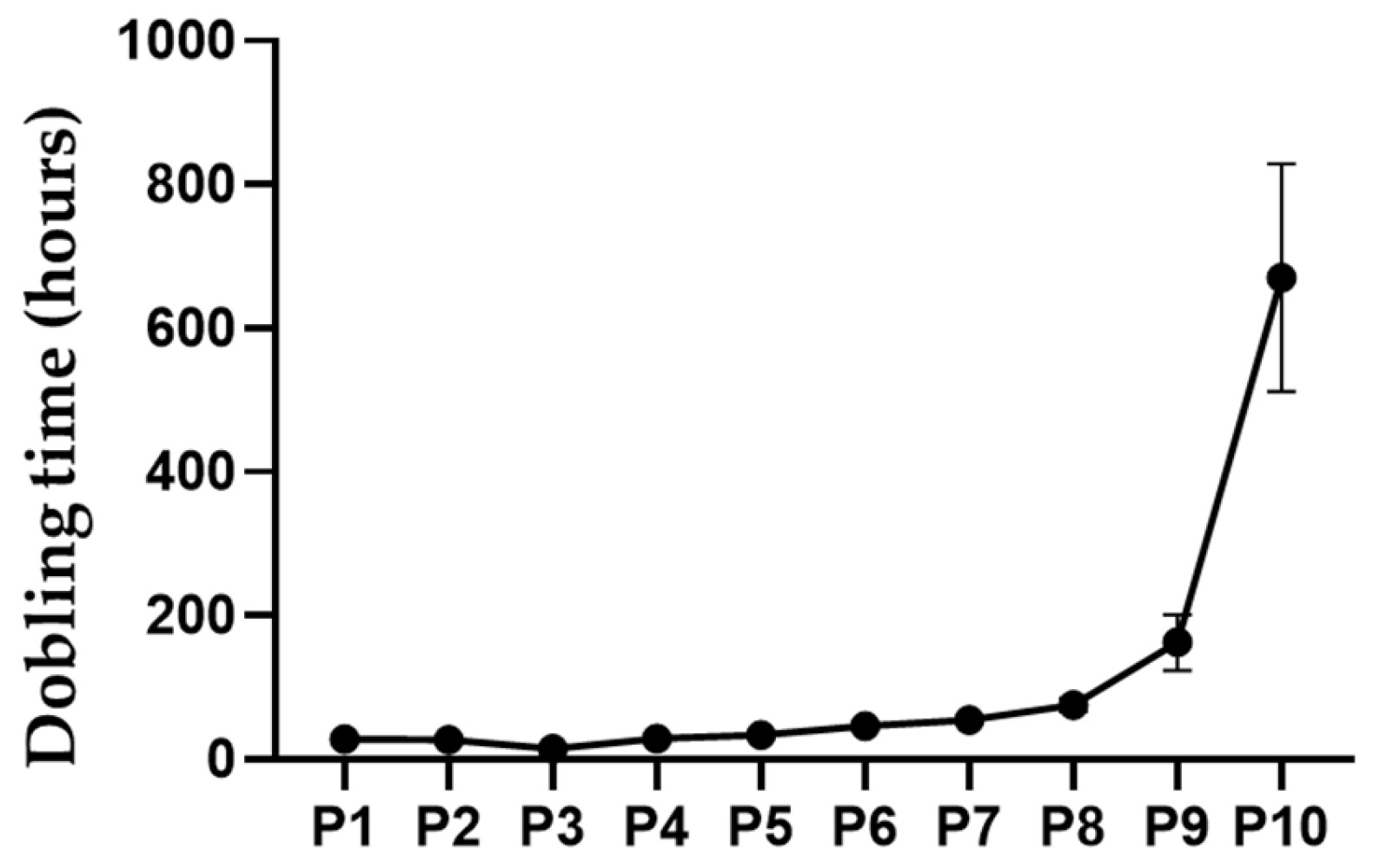

The doubling time of the mesenchymal cells originating from the immature canine bone marrow was as follows: P1 was 28.09 ± 1.20 hours, P2 was 27.13 ± 1.57 hours, P3 was 14.72 ± 0.61 hours, P4 was 28.93 ± 0.61 hours, P5 was 33.35 ± 1.77 hours, P6 was 46.67 ± 2.24 hours, P7 was 54.53 ± 0.74 hours, P8 was 75.36 ± 7.38 hours, P9 was 162.66 ± 31.68 hours, and P10 was 670.71 ± 129.29 hours (

Figure 4).

2.6. Identification of Cells Harvested from Immature Canine Bone Marrow

Identifying cells originating from immature canine bone marrow was performed using stem cell surface markers, including CD34-PE, CD45-PE, CD90-APC, and CD105-FITC. Surface marker expression was analyzed by flow cytometry using the BD FACSCanto® system (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Figure 5.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Surface Marker Expression Representative histograms illustrating the expression profiles of CD34, CD45, CD90, and CD105 on a cell population. For CD90 and CD105, a gray histogram (typically representing the corresponding isotype control) is also shown. The data indicate that the cells exhibit minimal expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34 and CD45) while expressing mesenchymal markers (CD90 and CD105), consistent with the expected immunophenotype of mesenchymal stem cells.

Figure 5.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Surface Marker Expression Representative histograms illustrating the expression profiles of CD34, CD45, CD90, and CD105 on a cell population. For CD90 and CD105, a gray histogram (typically representing the corresponding isotype control) is also shown. The data indicate that the cells exhibit minimal expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34 and CD45) while expressing mesenchymal markers (CD90 and CD105), consistent with the expected immunophenotype of mesenchymal stem cells.

2.7. Evaluation of Differentiation Capacity of MSCs Harvested from the Immature Canine Bone Marrow

The obtained cells were cultured in an adipogenic induction medium for 21 days. Afterward, they were stained with Oil Red O. The differentiated adipocytes formed lipid droplets that stained red, as captured in

Figure 6.

After 21 days of culture in the osteogenic induction medium, the cells developed a bean-shaped morphology characteristic of osteocytes (

Figure 6). Following Alizarin Red staining, the matrix showed nodules that stained red-orange due to the dye binding to deposited calcium, indicating the successful mineralization of the extracellular matrix and confirming robust osteogenic differentiation.

Cells cultured in a chondrogenic induction differentiation medium for 21 days formed cartilage aggregates (

Figure 6). The cartilage matrix stained red-orange due to the binding of the dye molecules with GAGs present in the cartilage matrix. Additionally, the cell nuclei were observed to stain a deep blue-black.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of differentiation capacities of immature Canine bone marrow. This figure demonstrates the multipotent differentiation potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) isolated from an immature canine donor. In adipogenesis, cells induced in adipogenic medium, where the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets is visualized by Oil Red O staining. In osteogenesis, cells cultured in osteogenic induction medium for 21 days exhibit a characteristic bean-shaped morphology, and the extracellular matrix is mineralized as evidenced by red-orange nodules following Alizarin Red S staining, indicating calcium deposition. In chondrogenic differentiation, cells form pellet aggregates that stain positively with Saffranin-O, highlighting the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans. All images were captured using phase-contrast microscopy with a 100-µm scale bar.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of differentiation capacities of immature Canine bone marrow. This figure demonstrates the multipotent differentiation potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) isolated from an immature canine donor. In adipogenesis, cells induced in adipogenic medium, where the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets is visualized by Oil Red O staining. In osteogenesis, cells cultured in osteogenic induction medium for 21 days exhibit a characteristic bean-shaped morphology, and the extracellular matrix is mineralized as evidenced by red-orange nodules following Alizarin Red S staining, indicating calcium deposition. In chondrogenic differentiation, cells form pellet aggregates that stain positively with Saffranin-O, highlighting the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans. All images were captured using phase-contrast microscopy with a 100-µm scale bar.

4. Discussion

Knee osteoarthritis is a chronic, progressive, and degenerative disorder that affects domestic dogs, particularly large and predisposed breeds, causing significant morbidity. Due to its clinical burden, advanced regenerative therapies, such as intra-articular injections of MSCs, have gained attention for their potential to stimulate cartilage repair and influence the disease trajectory. This study investigated a novel MSC source derived from immature canine bone marrow. The inherent stem cell characteristics of these cells, along with their strong regenerative properties, make them promising candidates for treating KOA.

A comprehensive biochemical and hematological evaluation of the immature canine donor confirmed its overall health and suitability for bone marrow extraction. The donor’s liver enzyme markers, including AST (16.04 U/L) and ALT (16.05 U/L), were within normative ranges, effectively excluding hepatic dysfunction, while a urea level of 8.2 mmol/L corroborated proper renal function [

16,

17]. Although the hematological profile demonstrated a slightly lower red blood cell count (4.85 × 10

6/mm

3), a modestly elevated white blood cell count (17.0 × 10

6/mm

3), and an increased hemoglobin concentration (21 g/dL), these variations are interpreted as normal developmental physiology rather than pathological aberrations. The platelet count (189 × 10

6/mm

3) remained within the standard range, further validating the donor’s fitness for bone marrow procurement [

18].

Upon primary culture, cells isolated from immature canine bone marrow demonstrated significant adherence to the culture substrate within seven days, as shown in

Figure 1A,C. The cells exhibited a spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like morphology with elongated cytoplasmic processes—a hallmark phenotype of MSCs that conforms to established criteria [

19,

20]. The strong adhesion observed is likely due to integrin-mediated focal adhesions, which support cell survival, proliferation, and the maintenance of the undifferentiated state. These morphological characteristics highlight the effectiveness of the optimized isolation and culture protocols in enriching a progenitor cell population while reducing cytotoxic stress.

The clonogenic potential of the isolated MSCs was further evidenced by their ability to form colony-forming units (CFUs) after two weeks of culture. The formation of distinct cell clusters, with a CFU-f frequency of (5 ± 1) clusters per one million mononuclear cells, quantitatively reflects their inherent proliferative and self-renewal capabilities. This robust clonogenicity not only validates the successful isolation and in vitro maintenance of a functionally competent MSC population but also indicates that these cells inherently possess the multipotent differentiation capacity required for practical regenerative medicine applications.

Morphological stability during in vitro expansion was closely monitored through serial imaging at 4× magnification. As documented in

Figure 3, MSCs maintained a consistent spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like appearance throughout successive passages. This phenotypic uniformity signifies the preservation of cytoskeletal integrity. It confirms that the culture conditions—encompassing optimized medium composition, substrate properties, and controlled incubation parameters—effectively uphold the undifferentiated state of the cells. Importantly, such morphological constancy is closely linked with the preservation of multipotency, while also diminishing the tendency for replicative senescence or spontaneous lineage commitment [

21].

A detailed evaluation of proliferation kinetics through serial passaging revealed a distinct biphasic profile. Early passages demonstrated rapid cell doubling times (28.09 ± 1.20 hours at P1, 27.13 ± 1.57 hours at P2, and a notably accelerated 14.72 ± 0.61 hours at P3), likely reflecting the selective expansion of a primitive, highly proliferative MSC subpopulation endowed with peak metabolic vigor. However, from passages P4 through P7, a progressive increase in doubling times (ranging from 28.93 ± 0.61 to 54.53 ± 0.74 hours) was noted, suggesting the onset of replicative stress or shifts in population dynamics. This trend became even more pronounced at later passages, with doubling times dramatically extending to 75.36 ± 7.38 hours (P8), 162.66 ± 31.68 hours (P9), and culminating at 670.71 ± 129.29 hours (P10). Such a significant elongation in doubling time indicates replicative senescence, likely mediated by telomere attrition, cumulative oxidative stress, and genomic instability, thereby underscoring the critical need to optimize culture duration to preserve the therapeutic potency of MSCs [

22].

Rigorous immunophenotypic characterization was performed using flow cytometry with a panel of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (CD34-PE, CD45-PE, CD90-APC, and CD105-FITC) on the BD FACSCanto

® system. The resulting data confirmed the MSC identity through robust expression of CD90 and CD105, which are markers emblematic of multipotency and regenerative potential, alongside minimal or absent expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34 and CD45). This precise immunophenotypic profiling verifies the purity of the isolated MSC population and ensures the functional integrity and reproducibility of the cell product for downstream regenerative applications [

23,

24].

The multipotent differentiation potential of these MSCs was conclusively demonstrated through directed lineage induction. Under adipogenic conditions for 21 days, the cells accumulated prominent intracellular lipid droplets, which were intensely stained red with Oil Red O, thus evidencing the activation of adipogenic transcriptional programs and successful commitment to the adipocyte lineage [

25]. Similarly, osteogenic induction for 21 days prompted a marked morphological transition to a bean-shaped phenotype characteristic of osteoblastic differentiation, with subsequent Alizarin Red staining revealing red–orange calcium-rich extracellular matrix nodules—a definitive marker of mineralization and osteogenic maturation, as evidenced by upregulation of osteo-specific markers such as Runx2 and osteocalcin [

26]. Furthermore, exposure to chondrogenic induction medium for 21 days led to the formation of well-defined cartilage aggregates; the extracellular matrix within these aggregates stained red–orange due to the deposition of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), while the concomitant deep blue–black nuclear staining affirmed the synthesis and spatial organization of a cartilage-specific matrix, essential for functional cartilage tissue [

27].

In summary, the thorough characterization of MSCs derived from immature canine bone marrow—illustrated through biochemical and hematological validation, rigorous morphological and proliferation assessments, precise immunophenotypic profiling, and clear demonstration of trilineage differentiation—attests to their significant translational potential. These findings not only highlight the inherent multipotency of these cells but also position them as a strong and promising therapeutic tool for advanced tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications in the treatment of KOA.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the present study provides compelling evidence that immature canine bone marrow is a promising and effective source of MSCs for regenerative applications in treating KOA. The donor’s robust biochemical and hematological profile confirmed its systemic health and validated the suitability of the extracted bone marrow. Subsequent isolation procedures yielded cells that displayed the hallmark spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like morphology and strong substrate adherence typical of MSCs, thereby affirming the efficacy of the optimized culture protocols. Quantitative analyses further substantiated the intrinsic regenerative capabilities of these MSCs, with the colony-forming unit assay revealing a reproducible clonogenic potential indicative of inherent self-renewal and proliferative capacity. A detailed evaluation of proliferation kinetics exhibited a biphasic profile whereby early passages demonstrated rapid doubling times—suggestive of a primitive, highly proliferative subpopulation—followed by a pronounced increase in doubling times in later passages, indicative of replicative senescence likely driven by telomere attrition and oxidative stress; this underscores the critical importance of utilizing early-passage MSCs to ensure maximal regenerative efficiency. Rigorous immunophenotypic characterization via flow cytometry confirmed MSC identity through high expression of CD90 and CD105 coupled with negligible reactivity for hematopoietic markers CD34 and CD45, while directed differentiation assays further demonstrated robust multipotency, evidenced by pronounced adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineage commitment as confirmed by lineage-specific histochemical staining and characteristic morphological changes. Collectively, these data validate that MSCs derived from immature canine bone marrow possess the critical attributes required for advanced regenerative therapies, positioning them as a promising candidate for future clinical applications in KOA treatment and warranting continued investigations to optimize in vitro expansion strategies and further evaluate their in vivo efficacy in cartilage regeneration and joint repair.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Minh-Dung Truong and Ngoc Bich Tran; methodology, Minh-Dung Truong and Le Thi Bich Thuy; investigation, Minh-Dung Truong; data curation, Thanh-Tan Nguyen-Ngoc, Vy-An Pham-Nguyen, Thi Dieu Hien Ngo, Xuan-Khai Phan, Ngoc Nam Phuong Le; writing—Le Thi Bich Thuy, Phuong Le Thi; writing—review and editing, Minh-Dung Truong, Ngoc Bich Tran; project administration, Minh-Dung Truong. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Can Tho University (CTU-AEC24014, 2024-05-17).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

A Data Availability Statement is available.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable support and contributions of their colleagues and technical staff throughout this study. We also appreciate the insightful comments and constructive feedback received from our peers and anonymous reviewers, which have greatly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KOA |

Knee osteoarthritis |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal stem cells |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

References

- Brondeel, C.; Pauwelyn, G.; de Bakker, E.; et al. Review: Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Canine Osteoarthritis Research: “Experientia Docet”. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerts, C.; Broeckx, S.Y.; Depuydt, E.; et al. Low-dose xenogeneic mesenchymal stem cells target canine osteoarthritis through systemic immunomodulation and homing. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2023, 25, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaniša, M.; Trbolová, A.; Hluchý, M.; Cížková, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Treatment of Osteoarthritis in Dogs—A Review. Herald Open Access 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelatto, C.K.; Aguiar, A.M.; Moretão, M.P.; Senegaglia, A.C.; Hansen, P.; Barchiki, F.; Oliveira, J.; Martins, J.; Kuligovski, C.; Mansur, F.; Christofis, A.; Amaral, V.F.; Brofman, P.S.; Goldenberg, S.; Nakao, L.S.; Correa, A. Dissimilar Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Bone Marrow, Umbilical Cord Blood, and Adipose Tissue. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontikoglou, C.; Deschaseaux, F.; Sensebé, L.; Papadaki, H.A. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Biological Properties and Their Role in Hematopoiesis and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2011, 7, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Guan, J.; Zhang, C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Mechanisms and Role in Bone Regeneration. Postgrad. Med. J. 2014, 90, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, Y.; Okawara, C.; Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Akazawa, C. Cellular Heterogeneity of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in the Bone Marrow. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 689366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, D.L. Bone Marrow in Aging: Changes? Yes; Clinical Malfunction? Not So Clear. Blood 2008, 112, sci-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Jackson, R.; Chen, L.; Song, J.; Pillai, R.; Afkhami, M.; Danilova, O.; Aoun, P.; Gaal, K.K.; Kim, Y. Determination of Age-Dependent Bone Marrow Normocellularity. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 161, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prządka, P.; Buczak, K.; Frejlich, E.; Gąsior, L.; Suliga, K.; Kiełbowicz, Z. The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in Veterinary Medicine and Their Use in Musculoskeletal Disorders. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.D.; Choi, B.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, M.S.; Min, B.H. Granulocyte-Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) Significantly Enhances Articular Cartilage Repair Potential by Microfracture. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017, 25, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Verma, M.; Singh, A. Animal Tissue Culture Principles and Applications. In Animal Biotechnology; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhao, L.; Kang, Q.; He, Y.; Bi, Y. An Optimized Method for Oil Red O Staining with the Salicylic Acid Ethanol Solution. Adipocyte 2023, 12, 2179334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, H.; Mir, L.M.; Andre, F.M. In Vitro Osteoblastic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Generates Cell Layers with Distinct Properties. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solchaga, L.A.; Penick, K.J.; Welter, J.F. Chondrogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: tips and tricks. In Mesenchymal Stem Cell Assays and Applications; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Johnson, B. Analysis of Canine Biochemical Parameters in Veterinary Practice. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2019, 25, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Doe, J.; Richards, L. Hematologic Profiles in Immature Canines: Implications for Regenerative Medicine. Vet. Res. Commun. 2021, 15, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; et al. Developmental Variations in Canine Blood Parameters. J. Clin. Vet. Sci. 2020, 18, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage Potential of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E. Minimal Criteria for Defining Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yue, A.; Ruan, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, R.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, L. Monitoring the Biology Stability of Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells during Long-Term Culture in Serum-Free Medium. Cell Tissue Bank 2014, 15, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonab, M.M.; Alimoghaddam, K.; Talebian, F.; Ghavamzadeh, A.; Ghaedi, K.; Mohyeddin Bonab, M.; Nadali, S. Replicative Senescence in Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Phenomenon Associated with Altered Cell Proliferation and Functionality. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, E.T.; Gustafson, M.P.; Dudakovic, A.; Riester, S.M.; Garces, C.G.; Paradise, C.R.; Takai, H.; Karperien, M.; Cool, S.; Sampen, A.N.; Larson, A.B.; Qu, W.; Smith, J.; Dietz, A.B.; van Wijnen, A.J. Identification and Validation of Multiple Cell Surface Markers of Clinical-Grade Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as Novel Release Criteria for Good Manufacturing Practice-Compliant Production. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, T.L.; Sánchez-Abarca, L.I.; Muntiñ, S.; Preciado, S.; Puig, N.; López-Ruano, G.; Hernández-Hernández, Á.; Redondo, A.; Ortega, R.; Sánchez-Guijo, F.; del Caño, C. MSC Surface Markers (CD44, CD73, and CD90) Can Identify Human MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles by Conventional Flow Cytometry. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunachalam, K.; Sreeja, P.S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Differentiation Protocols. In Advanced Cell and Molecular Techniques; Springer Protocols Handbooks; 2025; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Serrano, C.; Rémy, M.; Leste-Lasserre, T.; Laroche, G.; Durrieu, M.-C. Unravelling the Synergies: Effects of Hydrogel Mechanics and Biofunctionalization on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Osteogenic Differentiation. Materials Adv. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Dong, H.; Fang, X.; Zhang, W.; Duan, H. Frontier Progress and Translational Challenges of Pluripotent Differentiation of Stem Cells. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1583391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).