1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is indeed a prevalent condition globally. It is a degenerative joint disease that affects the cartilage in the knee, leading to pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility [

1]. Factors such as aging, obesity, joint injuries, and genetic predisposition can contribute to the development of knee osteoarthritis [

2]. Therefore, optimizing treatment methods for OA has become an essential and urgent demand in recent decades.

Indeed, numerous interventions have been researched and clinically applied to enhance function and restore activity at the injury site for patients with OA. These include non-pharmacological treatments (physical therapy regimens) [

3], pharmacological approaches (utilizing medications, cytokines, etc.) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], and surgical interventions (involving different surgical techniques) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The treatment methods for patients with OA are tailored based on the extent and severity of the injury. Autologous cell implantation (ACI) has emerged as a promising approach for treating OA. This method involves using the patient's cells to promote tissue regeneration and repair. The success of this method relies on several factors, with the most critical being the source of autologous cells and the use of periosteal patches to facilitate the formation of regenerative tissue with hyaline cartilage-like characteristics. The type and quality of cells used are crucial. Common sources include mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or peripheral blood. These cells have the potential to differentiate into cartilage cells and support tissue regeneration [

8,

11,

12]. These patches are used to create a supportive environment for the implanted cells. Periosteal patches contain progenitor cells and growth factors that facilitate the formation of regenerative tissue with hyaline cartilage-like characteristics. They provide a scaffold for cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, enhancing the overall effectiveness of the treatment. Indeed, research on improving periosteal patches or substituting them with bio-membranes is still in its early stages and remains limited. While periosteal patches have shown promise in enhancing tissue regeneration, ongoing efforts exist to develop and optimize bio-membranes as potential substitutes [

15].

Studies have explored using bio-membranes that replicate the structural and functional properties of periosteum, aiming to harness the body's natural healing processes [

16]. These bio-membranes are designed to provide a supportive environment for cell growth and tissue regeneration, similar to periosteal patches. However, more research is needed to understand their efficacy and long-term outcomes [

17] fully.

On the other hand, stem cells isolated from immature tissue (immature tissue-derived cells) are known as a safe cell source, similar to autologous cells in grafting. These cells exhibit superior proliferation and differentiation capabilities compared to adult stem cells. The function and characteristics of adult stem cells can be unstable due to their isolation from various donors; however, stem cells isolated from immature tissue can proliferate into large quantities of functionally and characteristically similar cells due to a single donor origin. Furthermore, stem cells derived from immature tissue exhibit embryonic-like functionality while maintaining a safety profile comparable to that of adult stem cells. [

18]. Owing to these attributes, stem cells from immature tissue demonstrate a high potential for application in cell therapy.

This study uses a novel cell source from one-day-old porcine cartilage to fabricate a bio-membrane to alter periosteal membranes in cell implantation techniques for treating knee joint injuries. The research involves isolating and characterizing cells from one-day-old porcine cartilage. These cells' proliferation and differentiation capacities and their ability to form bio-membranes are also assessed. The protein component of bio-membrane also was defined by proteomics. Cartilage repair ability is also confirmed using an in vitro transplantation model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Isolation of Stem Cells from Cartilage Tissue of One-Day-Old Porcine

Healthy one-day-old porcine with intact limbs were selected as subjects to provide cartilage tissue for this study. The knee joints of the porcine were obtained immediately after sterilization and surgery. The freshly collected cartilage tissue was washed thrice in 10 ml of 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (Gibco, USA). The cartilage tissue was then finely chopped into pieces smaller than 1 mm. A collagenase solution (0.1% collagenase, Worthington, USA) was added and placed in a cell culture incubator (conditions: 37℃, 5% CO2) for 16 hours to degrade the fibrous structures in the tissue and liberate single cells. After the 16-hour incubation, the digested tissue was centrifuged to collect the single cells accumulating at the tube bottom, which were then washed three times with 1X PBS solution. The isolated single cells were then resuspended in an essential culture medium, which included Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, USA).

Single cells derived from cartilage tissue were quantified and cultured in an essential culture medium in a cell culture incubator. Cell morphology was regularly monitored using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Japan), and the culture medium was changed at three-day intervals during cultivation.

2.2. Evaluation of the Biological Characteristics of Cells Collected from One-Day-Old Porcine Cartilage Tissue

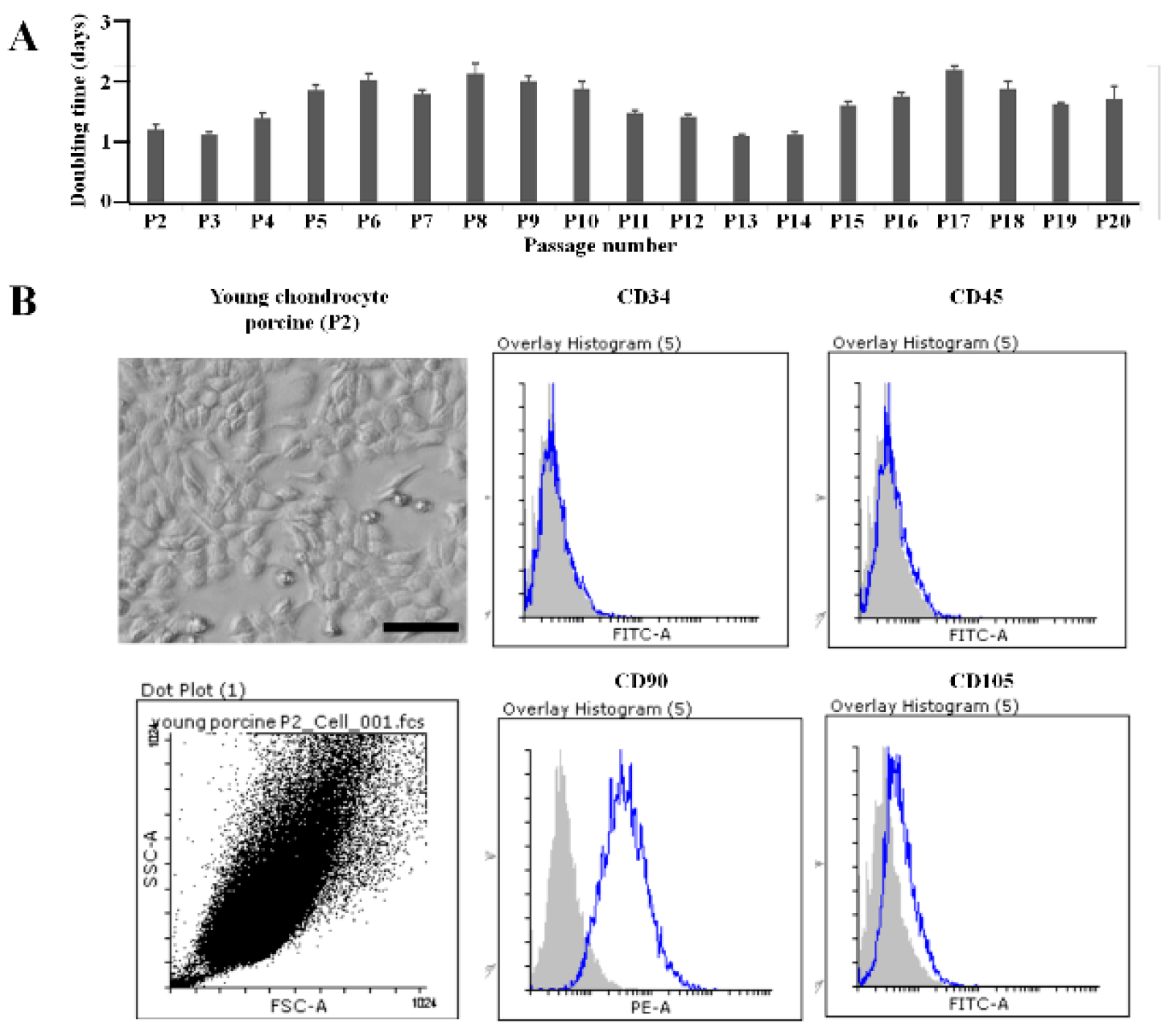

Using an inverted microscope, cells isolated from the one-day-old porcine cartilage tissue were observed for morphology across passages (up to passage 20). The proliferation rate of the cells was assessed based on their doubling time up to passage 20. Cell identification was performed by expressing cell surface markers evaluated by FACS, including CD34, CD45, CD90, and CD105 (Thermo Fisher, UK).

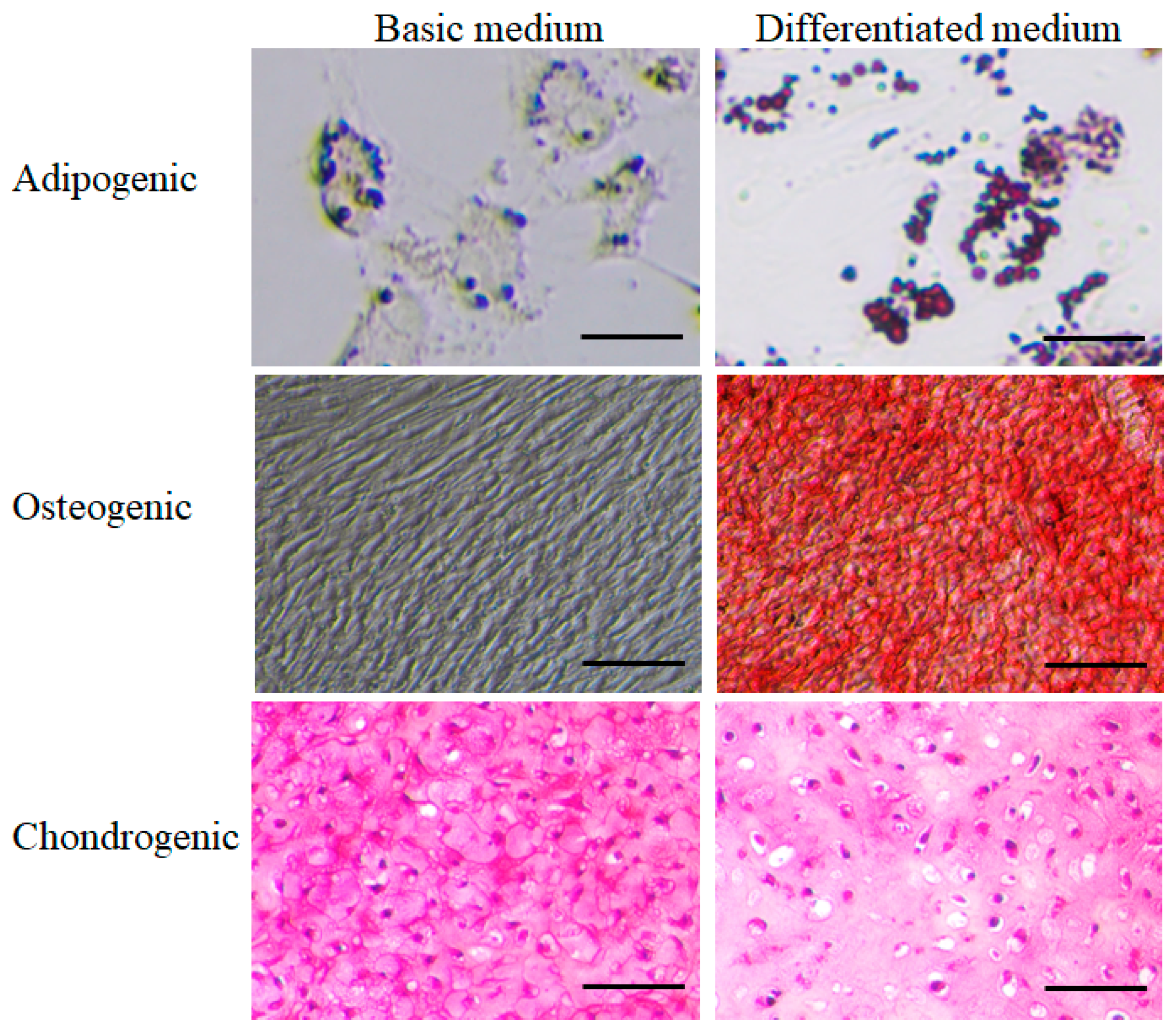

2.3. Evaluation of the Differentiation Potential of Stem Cells from One-Day-Old Porcine Cartilage Tissue

Cells at passage 2 (P2) were evaluated for their ability to differentiate into three basic cell lineages: adipogenesis, osteogenesis, and chondrogenesis. Cells were cultured in an adipogenic differentiation medium for adipocyte differentiation, and their adipogenic potential was assessed using Oil Red O staining. Cells were cultured in an osteogenic differentiation medium for osteocyte differentiation, and their osteogenic potential was evaluated using Alizarin Red staining. For chondrocyte differentiation, cells were cultured in 3D structural spheroids using a chondrogenic differentiation medium, and their chondrogenic potential was assessed using Safranin-O staining.

2.4. Evaluation of the Bio-Membrane-Forming Capability of Stem Cells from One-Day-Old Porcine Cartilage Tissue

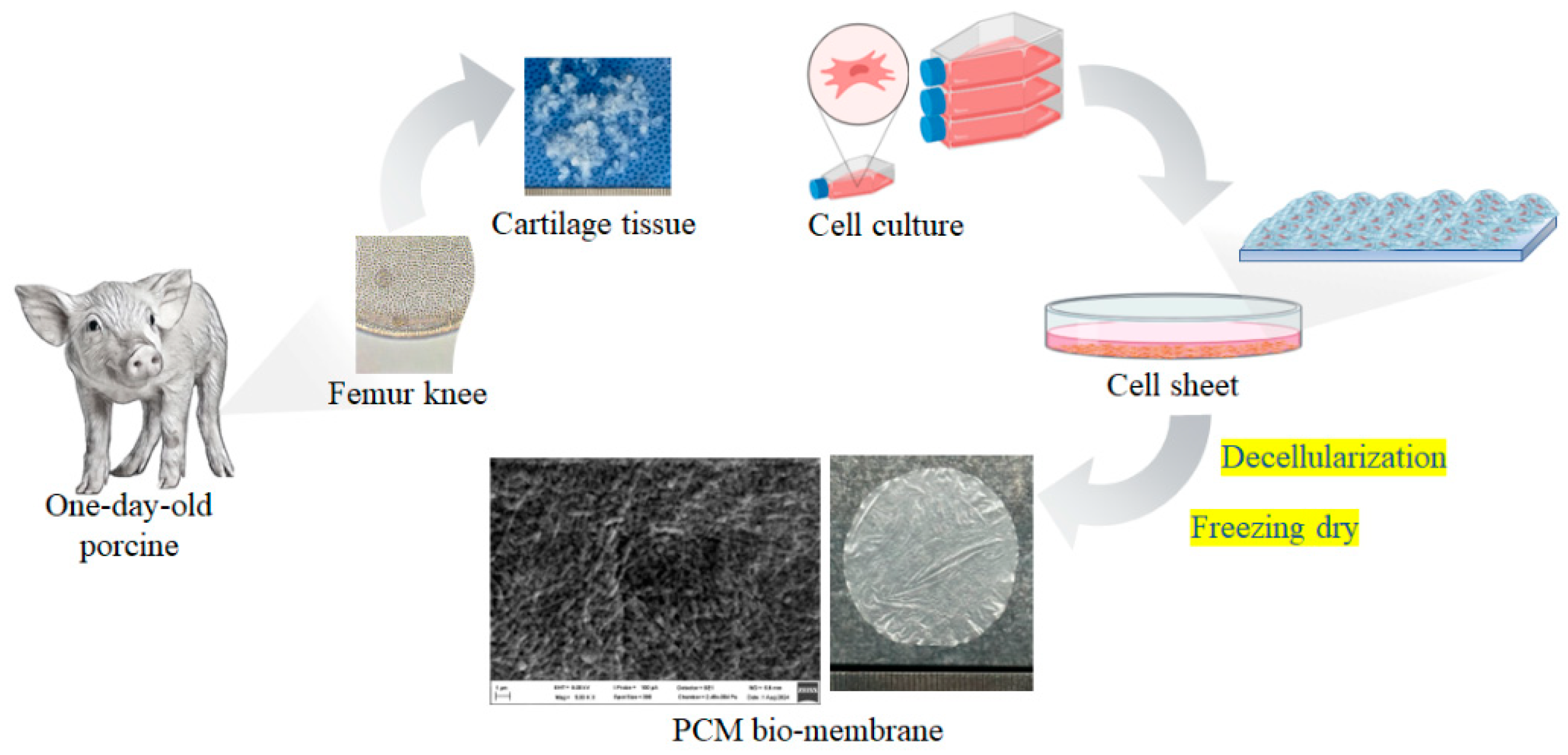

Cells at passage 2 (P2) were cultured in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 x 10^6 cells/cm². The membrane formation medium consisted of cell culture medium supplemented with insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS), 50 mg/ml ascorbate 2-phosphate, 100 nM dexamethasone, 40 mg/ml proline, and 1.25 mg/ml BSA (Sigma, USA). After two weeks of culture, the cell sheets were decellularized using a 1% SDS solution (Sigma, USA). Genetic material was eliminated using DNAse/RNAse enzymes. The cell sheets were freeze-dried at -80°C to create the PCM bio-membrane.

2.5. Proteomic Analysis in PCM Bio-Membrane

The bio-membrane was lysed, and a genetic database was obtained using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Subsequently, the database was analyzed using Gene Ontology enrichment analysis and visualization tool (GOrilla).

2.6. Evaluation of the Cartilage Repair Capacity of PCM Bio-Membrane

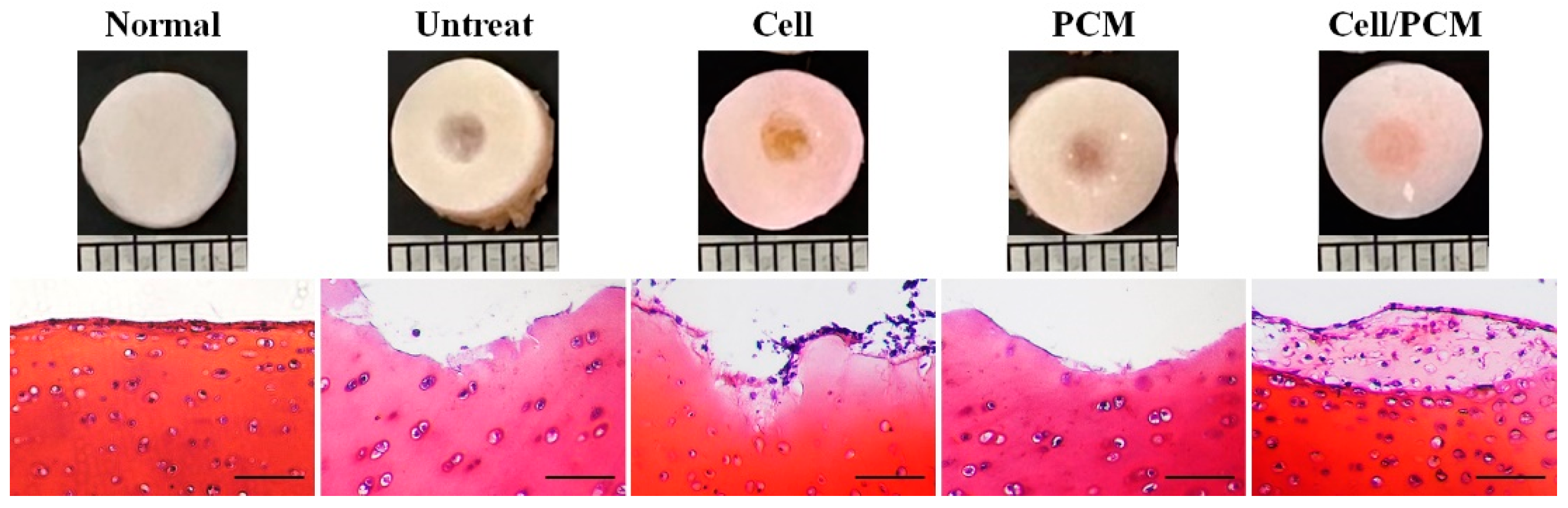

The cartilage repair capacity of the bio-membrane was confirmed using an in vitro transplantation model. A 3 mm cartilage defect was drilled in a market porcine cartilage block with a diameter of 6 mm. The experiment was designed in four groups: i) Untreated Group: Control group with no treatment; ii) Cells Treated Group: Chondrocytes were used to treat the cartilage defect; iii) PCM Treated Group: PCM bio-membrane was used to treat the cartilage defect; and iv) Cells/PCM Treated Group: Chondrocytes and PCM bio-membrane were used to treat the cartilage defect. The porcine cartilage blocks were cultured in a chondrogenic medium and placed in a cell culture incubator (conditions: 37℃, 5% CO2) for three weeks. The culture medium was changed at three-day intervals during cultivation. The cartilage repair will be assessed three weeks after transplantation using Safranin-O staining.

3. Results

3.1. Collection and Isolation of Stem Cells from Cartilage Tissue of One-Day-Old Porcine

Cartilage tissue was collected from the knee joints of one-day-old porcine, with a cartilage tissue mass of 0.90 ± 0.27 g. The number of isolated cells was 28 ± 8.51 million, the number of isolated cells per gram of cartilage tissue was 31.03 ± 4.39 million, and the number of cells obtained at P0 was 100 ± 30.41 million. The cell morphology after isolation was consistent across samples, as shown in

Supplementary Figure S1. The cells at P0 were collected and stored in liquid nitrogen.

3.2. Evaluation of the Biological Characteristics of Cells Collected from One-Day-Old Porcine Cartilage Tissue

The cells were thawed and monitored for morphology under a microscope until the 20th passage (P20) (Supplementary

Figure 1). The shape and size of the cells from stages P1 to P20 did not show significant changes. The cell proliferation rate, measured by the doubling time, ranged from 1 to 2 days and was observed from stage P1 to P20 (

Figure 1A). Therefore, the morphological characteristics and proliferation capacity of the cells from the cartilage tissue of one-day-old porcine remained stable throughout stages P1 to P20.

The cells were identified using flow cytometry, as shown in

Figure 1B. At passage 2 (P2), the cells expressed the following surface markers: CD34 (0.19 ± 0.18%); CD45 (0.28 ± 0.19%); CD90 (95.57 ± 0.48%); and CD105 (9.58 ± 1.48%).

3.3. Evaluation of the Differentiation Potential of Stem Cells from One-Day-Old Porcine Cartilage Tissue

Adipogenic differentiation: The ability to form adipocytes was observed using Oil Red O staining in a differentiation medium. Red-stained lipid droplets were observed after 14 days of culture in the differentiation medium, compared to the negative control (cells not differentiated into adipocytes in the basic culture medium) (

Figure 2).

Osteogenic differentiation: The ability to form osteocytes was observed using Alizarin Red staining in an osteogenic differentiation medium. The red staining of Alizarin Red confirmed differentiation into osteocytes observed after 21 days of culture in the differentiation medium, compared to the negative control (cells not differentiated into osteocytes in the basic culture medium) (

Figure 2).

Chondrogenic differentiation: Cells were successfully cultured into 3D aggregates in the basic culture medium and the chondrogenic differentiation medium. In both media, thin sections of the 3D tissue samples showed staining with Safranin-O. However, chondrocytes and lacunae (small cavities containing chondrocytes) were more abundantly formed in the chondrogenic differentiation medium. In contrast, lacunae were not formed in the basic culture medium (

Figure 2).

3.4. Evaluation of the Bio-Membrane-Forming Capability of Stem Cells from One-Day-Old Porcine Cartilage Tissue

Cell sheets were successfully formed by P2 cells at a density of 0.5 x 10^6 cells/cm² in the cell culture medium supplemented with insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS), 50 mg/ml ascorbate 2-phosphate, 100 nM dexamethasone, 40 mg/ml proline, and 1.25 mg/ml BSA. After two weeks of culture, the cell sheets were decellularized using a 1% SDS solution. The decellularization process effectively removed cellular components, as confirmed by the absence of cellular debris under microscopic examination. Genetic material was eliminated using DNAse/RNAse enzymes, ensuring the removal of residual DNA and RNA. The decellularized cell sheets were then freeze-dried at -80°C to create the PCM bio-membrane. The resulting bio-membrane exhibited a uniform structure and retained its mechanical integrity, making it suitable for further applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (

Figure 3).

3.5. Proteomic Analysis in PCM Bio-Membrane

According to the protein profile, the most recognized protein was associated with extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1). Additionally, several growth factors were identified, including transforming growth factor (TGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (

Table 1).

3.6. Evaluation of the Cartilage Repair Capacity of PCM Bio-Membrane

Cross-image and Safranin-O staining revealed the formation of new cartilage tissue in the defect area. No new tissue was observed in the defect area in the untreated group. In the cells-treated group, new tissue with a small number of cells was present in the defect area. No new tissue was observed in the defect area in the PCM-treated group. In the cells/PCM-treated group, new tissue formed in the defect area, with cells resembling chondrocytes and lacunae stained with Safranin-O (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated a novel approach using cells derived from one-day-old porcine cartilage to fabricate a bio-membrane for inducing cartilage repair in knee joints. The cells were successfully harvested from healthy one-day-old porcine and exhibited high proliferation, renewal, and multiple differentiation capabilities. These characteristics are akin to stem cells, essential for forming biomembranes. The protein profile analysis further revealed the presence of extracellular structure organization, extracellular matrix organization, collagen fibril organization, and supramolecular fiber organization. Additionally, the PCM bio-membrane showed promising results in inducing cartilage repair in joint damage, highlighting its potential as an effective treatment for knee joint injuries.

One-day-old porcine cartilage was utilized in this research due to its superior cell yield efficiency, proliferation capacity, and differentiation ability. The results demonstrated that collecting and isolating cells from the cartilage tissue of one-day-old porcine is highly stable, as evidenced by the high number of isolated cells per gram of cartilage tissue and the high yield of cells, which increased well until passage 20. These cells also exhibited stem cell marker expression and multipotent differentiation into chondrogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic lineages.

Relevant studies have shown that immature cartilage progenitor cells have been investigated as a potential cell source for regenerative medicine [

19,

20]. Cartilage cells are harvested from different developmental stages, with varying results regarding differentiation abilities [

21,

22]. Mijin Kim et al. demonstrated that the characteristics and abilities of immature cartilage cells depend highly on their developmental stages, which should be considered when developing fetal cell-based therapies. The expression of pluripotency genes (Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2) was observed in embryonic days (Day 14 in the rat model), while the expression of chondrogenic genes (Col2a1, Acan) gradually increased in cartilage cells up to epiphyseal cartilage formation (Day 20 in the rat model). This implies that cartilage cells from the epiphysis may be the best cell source for cartilage regeneration [

23]. Thus, one-day-old porcine cartilage provided a rich source of cells for research and product development in this study.

The successful formation of cell sheets by P2 cells at a density of 0.5 x 10^6 cells/cm² in the supplemented cell culture medium demonstrates the efficacy of the chosen culture conditions. The supplementation with ITS, ascorbate 2-phosphate, dexamethasone, proline, and BSA provided an optimal environment for cell growth and sheet formation. After two weeks of culture, the decellularization process using a 1% SDS solution effectively removed cellular components, as confirmed by the absence of cellular debris under microscopic examination. The subsequent elimination of genetic material using DNAse/RNAse enzymes ensured the removal of residual DNA and RNA, which is crucial for preventing immune reactions in potential clinical applications.

The freeze-drying process at -80°C successfully created the PCM bio-membrane, which exhibited a uniform structure and retained its mechanical integrity. These characteristics make the PCM bio-membrane suitable for further tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. The bio-membrane's uniform structure and mechanical integrity are essential for its potential use in cartilage repair and other regenerative therapies. The results indicate that the developed PCM bio-membrane holds promise for future clinical applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

The protein profile analysis revealed that the most recognized protein was associated with ECM1. This finding is significant as ECM1 plays a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity of tissues and facilitating cell signaling. Several growth factors were also identified, including TGF, FGF, IGF, and EGF. These growth factors are known to be involved in various cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and tissue repair. The presence of these proteins and growth factors in the bio-membrane suggests its potential efficacy in promoting cartilage repair and regeneration. The results indicate that the PCM bio-membrane is a promising candidate for tissue engineering applications, particularly in cartilage repair.

The results of this study demonstrated the effectiveness of different treatments in promoting cartilage repair in the defect area. Cross-image and Safranin-O staining revealed the formation of new cartilage tissue in the defect area. No new tissue was observed in the untreated group, indicating that the natural healing process was insufficient for cartilage repair. In the cells-treated group, new tissue with a small number of cells was present, suggesting that introducing chondrocytes alone had a limited effect on cartilage regeneration. No new tissue was observed in the PCM-treated group, indicating that the PCM bio-membrane alone was insufficient to induce cartilage repair. However, in the cells/PCM-treated group, new tissue formed in the defect area, with cells resembling chondrocytes and lacunae stained with Safranin-O. This finding suggests that combining chondrocytes and PCM bio-membrane provided a synergistic effect, enhancing cartilage repair and regeneration. Overall, these results highlight the potential of using a combination of chondrocytes and PCM bio-membrane for effective cartilage repair in joint damage.

Biomembranes used in cartilage tissue regeneration for treating Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) are crucial in supporting healing and regeneration. They provide a scaffold for chondrocytes (cartilage cells) to adhere to, proliferate, and differentiate, essential for effective cartilage repair. Biomembranes offer a supportive environment for chondrocytes, helping them adhere and grow while protecting them from mechanical and chemical impacts from the surrounding environment. These biomembranes are made from biocompatible materials such as collagen, chitosan, or other biological polymers, which do not cause immune reactions and are biodegradable.

Using biomembranes enhances the effectiveness of the ACI method by improving chondrocyte adhesion and growth, minimizing the risk of infection and post-surgical complications. Biomembranes have been successfully used in many studies and clinical applications to treat joint cartilage injuries, particularly in the knee. However, there are several limitations associated with the use of biomembranes in cartilage tissue regeneration for ACI: 1) Integration Issues: Biomembranes may not integrate well with the surrounding tissue, leading to poor adhesion and potential failure of the implant [

24]; 2) Immune Response: Although biomembranes are designed to be biocompatible, there is still a risk of immune response or rejection by the body [

25]; 3) Mechanical Properties: The mechanical strength of biomembranes may not match that of natural cartilage, which can lead to issues with durability and functionality [

26]; 4) Cost and Complexity: The production and application of biomembranes can be costly and complex, making them less accessible for widespread clinical use [

24]; 5) Limited Long-term Data: There is limited long-term data on the effectiveness and safety of biomembranes in ACI, which makes it difficult to assess their potential benefits and risks fully [

25].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated a novel approach using cells derived from one-day-old porcine cartilage to fabricate a bio-membrane for inducing cartilage repair in knee joints. The cells exhibited high proliferation, renewal, and multiple differentiation capabilities, akin to stem cells, which are essential for forming biomembranes. The protein profile analysis revealed the presence of extracellular structure organization, extracellular matrix organization, collagen fibril organization, and supramolecular fiber organization. Additionally, the PCM bio-membrane showed promising results in inducing cartilage repair in joint damage, highlighting its potential as an effective treatment for knee joint injuries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Minh-Dung Truong; methodology, Phuong-Vy Bui, Vang Pham Thi; data curation, Trung-Nhan Vo, Viet-Trinh Nguyen, Thai-Duong Tran, Vu-Khanh Vo; writing—original draft preparation, Minh-Dung Truong, Phuong-Vy Bui; writing—review and editing, Minh-Dung Truong, Phuong-Vy Bui; project administration, Minh-Dung Truong; funding acquisition, Minh-Dung Truong, Phuong Le Thi, Dieu Linh Tran. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ho Chi Minh City Science and Technology Development Fund, grant number 03/2023/HĐ-QKHCN. The APC was funded by the Ho Chi Minh City Science and Technology Development Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to isolated cells and tissues, which were ethically reviewed by the Animal Ethics Advisory Committee at the Biotechnology Centre of Ho Chi Minh City (IRB No. 01-2023-ĐĐĐV).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone who contributed to this study. Special thanks to the research team for their dedication and hard work. We also extend our appreciation to the institutions and organizations that provided support and resources. Lastly, we are grateful to the reviewers for their valuable feedback and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACI |

Autologous chondrocyte implantation |

| OA |

Osteoarthritis |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| GAG |

Glycoaminoglycan |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| P/S |

Penicillin-Streptomycin |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| ITS |

Insulin-transferrin-selenium |

References

- Mautner K, Gottschalk M, Boden SD, Akard A, Bae WC, Black L, et al. Cell-based versus corticosteroid injections for knee pain in osteoarthritis: a randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med 2023;29(12):3120-26. [CrossRef]

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019;393(10182):1745-59. [CrossRef]

- Mithoefer K, Hambly K, Logerstedt D, Ricci M, Silvers H, Della Villa S. Current concepts for rehabilitation and return to sport after knee articular cartilage repair in the athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012;42(3):254-73. [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos V, Mouzopoulos G, Floros T, Tzurbakis M. Steroid-induced femoral head osteonecrosis in immune thrombocytopenia treatment with osteochondral autograft transplantation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23(9):2605-10. [CrossRef]

- Goggs R, Vaughan-Thomas A, Clegg PD, Carter SD, Innes JF, Mobasheri A, et al. Nutraceutical therapies for degenerative joint diseases: a critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2005;45(3):145-64. [CrossRef]

- Kang SW, Bada LP, Kang CS, Lee JS, Kim CH, Park JH, et al. Articular cartilage regeneration with microfracture and hyaluronic acid. Biotechnol Lett 2008;30(3):435-9. [CrossRef]

- Legovic D, Zorihic S, Gulan G, Tudor A, Prpic T, Santic V, et al. Microfracture technique in combination with intraarticular hyaluronic acid injection in articular cartilage defect regeneration in rabbit model. Coll Antropol 2009;33(2):619-23.

- Ohashi H, Nishida K, Yoshida A, Nasu Y, Nakahara R, Matsumoto Y, et al. Adipose-Derived Extract Suppresses IL-1beta-Induced Inflammatory Signaling Pathways in Human Chondrocytes and Ameliorates the Cartilage Destruction of Experimental Osteoarthritis in Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22(18). [CrossRef]

- Thosani R, Pawar V, Giridhar R, Yadav MR. Improved percutaneous delivery of some NSAIDs for the treatment of arthritis. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2012;4(Suppl 1):S12-3. [CrossRef]

- Betzler BK, Bin Muhammad Ridzwan Chew AH, Bin Abd Razak HR. Intra-articular injection of orthobiologics in patients undergoing high tibial osteotomy for knee osteoarthritis is safe and effective - a systematic review. J Exp Orthop 2021;8(1):83. [CrossRef]

- LaPrade RF, Ly TV, Wentorf FA, Engebretsen L. The posterolateral attachments of the knee: a qualitative and quantitative morphologic analysis of the fibular collateral ligament, popliteus tendon, popliteofibular ligament, and lateral gastrocnemius tendon. Am J Sports Med 2003;31(6):854-60. [CrossRef]

- Stotter C, Nehrer S, Klestil T, Reuter P. [Autologous chondrocyte transplantation with bone augmentation for the treatment of osteochodral defects of the knee : Treatment of osteochondral defects of the femoral condyles using autologous cancellous bone from the iliac crest combined with matrix-guided autologous chondrocyte transplantation]. Oper Orthop Traumatol 2022;34(3):239-52. [CrossRef]

- Truong MD, Choi BH, Kim YJ, Kim MS, Min BH. Granulocyte macrophage - colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) significantly enhances articular cartilage repair potential by microfracture. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017;25(8):1345-52. [CrossRef]

- Truong MD, Chung JY, Kim YJ, Jin LH, Kim BJ, Choi BH, et al. Histomorphochemical comparison of microfracture as a first-line and a salvage procedure: is microfracture still a viable option for knee cartilage repair in a salvage situation? J Orthop Res 2014;32(6):802-10. [CrossRef]

- Gong M, Chi C, Ye J, Liao M, Xie W, Wu C, et al. Icariin-loaded electrospun PCL/gelatin nanofiber membrane as potential artificial periosteum. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018;170:201-09. [CrossRef]

- Moore SR, Heu C, Yu NY, Whan RM, Knothe UR, Milz S, et al. Translating Periosteum's Regenerative Power: Insights From Quantitative Analysis of Tissue Genesis With a Periosteum Substitute Implant. Stem Cells Transl Med 2016;5(12):1739-49. [CrossRef]

- Gomoll AH, Probst C, Farr J, Cole BJ, Minas T. Use of a type I/III bilayer collagen membrane decreases reoperation rates for symptomatic hypertrophy after autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Sports Med 2009;37 Suppl 1:20S-23S. [CrossRef]

- Park DY, Min BH, Park SR, Oh HJ, Truong MD, Kim M, et al. Engineered cartilage utilizing fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells for cartilage repair. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):5722. [CrossRef]

- Cui Y, Wang H, Yu M, Xu T, Li X, Li L. Differentiation plasticity of human fetal articular chondrocytes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;135(1):61-7. [CrossRef]

- Choi WH, Kim HR, Lee SJ, Jeong N, Park SR, Choi BH, et al. Fetal Cartilage-Derived Cells Have Stem Cell Properties and Are a Highly Potent Cell Source for Cartilage Regeneration. Cell Transplant 2016;25(3):449-61. [CrossRef]

- Mirmalek-Sani SH, Tare RS, Morgan SM, Roach HI, Wilson DI, Hanley NA, et al. Characterization and multipotentiality of human fetal femur-derived cells: implications for skeletal tissue regeneration. Stem Cells 2006;24(4):1042-53. [CrossRef]

- Quintin A, Schizas C, Scaletta C, Jaccoud S, Applegate LA, Pioletti DP. Plasticity of fetal cartilaginous cells. Cell Transplant 2010;19(10):1349-57. [CrossRef]

- Kim M, Kim J, Park SR, Park DY, Kim YJ, Choi BH, et al. Comparison of fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells isolated at different developmental stages in a rat model. Dev Growth Differ 2016;58(2):167-79. [CrossRef]

- Samsudin EZ, Kamarul T. The comparison between the different generations of autologous chondrocyte implantation with other treatment modalities: a systematic review of clinical trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016;24(12):3912-26. [CrossRef]

- Zellner J, Krutsch W, Pfeifer C, Koch M, Nerlich M, Angele P. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for cartilage repair: current perspectives. Orthopedic Research and Reviews 2015. [CrossRef]

- Leja L, Minas T. Periosteum-covered ACI (ACI-P) versus collagen membrane ACI (ACI-C): A single-surgeon, large cohort analysis of clinical outcomes and graft survivorship. Journal of Cartilage & Joint Preservation 2021;1(2). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).